Oxford University Press's Blog, page 950

April 29, 2013

Sovereign debt after March 2013

It is perhaps natural human tendency to think that the big events that occur during our lifetimes — particularly if they involve us personally — are both unique and will change the course of history. Reality though is that most of us aren’t particularly good at predicting what future historians will consider important. Worse, we tend to dramatically exaggerate the importance of events that we have watched occur. Rogoff and Reinhart’s bestselling treatment of the history of sovereign debt has the ironic title This Time is Different precisely because of how often we are wrong in thinking that “this time is different.” Having provided these cautions, I am going to fall into the precise trap I warned against and assert that the period between March 2012 and March 2013 will go down in history as one of the most eventful ever in the history of sovereign debt. This time is different. Why?

There are a number of candidates in terms of potentially game changing events that occurred in the sovereign markets over these past twelve months. As a backdrop to these events, we are in the midst of what is likely one of the most biggest sovereign debt crises in history: the crisis of the euro area. That crisis, which began with European politicians swearing up and down in 2010 and 2011 that no Eurozone country would ever default, saw Greece, in March 2012 impose one of the biggest and most severe haircuts on private sector creditors in history. Euro area politicians who (like me) seem to have little concern for how historians might subject their statements to ridicule in hindsight are now announcing loudly that the Greek restructuring was “unique and exceptional”.

So much happened within the Greek restructuring that was new, and even when not new, certainly eventful. Foremost, there were the legislatively mandated Collective Action Clauses that were imposed on local law governed debt instruments. Then was the drama over whether the Greek restructuring was voluntary or not and whether the CDS contracts would be triggered (hard to imagine how anyone could think that a creditor taking a 70% haircut was doing so voluntarily; but that argument was made at various points). And if that was not enough, at the nth hour in the Greek restructuring, the European Central Bank demanded for itself, as a legal right, super priority over all other creditors — essentially the right to be exempt from the restructuring. As a matter of optimal rules for the system, there is probably an argument for Official Sector lending by institutions like the ECB and the IMF to be given super priority. But the ECB’s priority claim, unlike IMF claims in the past, was with respect to bonds that it had purchased on the market just as if it were an ordinary investor. There was a risk, therefore, that investors who had entered the Greek exchange would bring a legal claim against the ECB for having received an illegal priority. As of this writing it is not clear whether any of the claims that have been threatened will bear fruition, but the can of worms regarding the precise contours of Official Sector priority has been opened.

There was more that didn’t make the daily headlines, but will probably make the history books. There was the explicit inclusion of some of Greece’s sovereign guarantees in the restructuring (no one quite understands why some guarantees got ensnared and others escaped completely, but that is a matter for a different day). And then there were was the treatment of the foreign-law bonds in the Greek deal. There was some attempt to extract a haircut from them; but the attempt was half-hearted at best — much more could have been done to turn the screws. Which, in turn, raises the puzzle of why the holders of those foreign-law bonds (many of whom likely go under the moniker “hedge fund”) were treated with such solicitude Literally, the holders of some of these foreign-law bonds were just asked politely whether they would like to restructure and when they said no (some did say yes), they were paid in full and on time. By contrast, the holders of the local-law bonds got taken to the woodshed.

The events in Greece itself would have entitled the past twelve months to go down as one of the most eventful in periods in sovereign debt history. But so much more happened as well. In Ireland, to restructure the debts of one of the banking institutions at the center of that nation’s crisis, the authorities invoked a technique called the Exit Exchange. This technique, through the 1990s, had been used to successfully engineer multiple sovereign debt restructurings (among them, Ecuador, Uruguay and the Dominican Republic). The technique is one that is aimed at, to put it politely, incentivizing holdout creditors to accept a restructuring offer that a majority of other creditors like, but that the holdouts would rather not take. As a legal matter, utilizing the technique has always been a tricky matter, since there is a fine line between deterring holdout creditors from blocking a deal that is in the collective interest of the creditor group and coercing the whole group. In the transactions, the Irish authorities decided to go on an all out attack in terms of the “offer you don’t want to refuse” that they presented creditors with. The debt in question though was governed by English law and an English judge in Assénagon Asset Management v. IBRC decided that the aforementioned line had not only been crossed, but abused and trampled. So much so that he wrote an opinion that called into question the validity of all future uses of the technique. Whether the opinion is followed by other courts is yet to be seen. But I suspect that regardless of how much commentators complain about the Assénagon case, the Exit Exchange technique will never be the same.

In the meantime, while announcing that the Greek restructuring was “unique and exceptional”, the euro area authorities mandated, starting January 1, 2013, what is easily the biggest change in contract language in sovereign debt contracts ever. All Eurozone sovereign debt contracts, regardless of governing law or other provisions, will henceforth (with minor allowances for a transition period) will contain Collective Action Clauses or CACs. These E-CACs in question are the technical devices that Greece imposed on its bonds legislatively so as to be able to engineer its March 2012 restructuring. The Eurozone has put into effect in all bonds for all of its members, much the same mechanism that Greece utilized. There are at least two things about this Euro CAC initiative that are historically significant. First, the reform attempts to change the standard template for not just foreign-law governed bonds (the focus of prior contract reform attempts), but also local-law bonds. Second, the contract terms here are being mandated. Prior to this, sovereigns had always chosen the contract terms that they thought best suited their individual interests. No longer; at least not in the euro area. The policy decision was made that one size should fit all. It might be a bit puzzling to some of us as to why, given the supposedly “unique and exceptional” character of the Greek restructuring these E-CACs are needed, but only time will tell.

To repeat myself, the foregoing should have been enough to conclude that the past twelve months were the most significant twelve month period in the history of the sovereign debt markets. But we have not gotten to the biggest event of them all — the holdout litigation against Argentina in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York.

The defining feature of sovereign debt, for time immemorial, has been that such debt is near impossible to enforce. Sovereigns, pretty much, have always been able to thumb their nose at creditors whenever they wanted. They pay because they want to, not because they have to. On rare occasions, there have been creditors who were important or big enough that they could get their nation’s gunboats to act as enforcers, but these events have been few and far between. And, in any event, using gunboats to enforce debt isn’t really allowed these days. Indeed, in the academic literature, there is a cottage industry of articles asking the question of why, absent enforcement, anyone in the modern era lends to a sovereign. Well, all of that may have changed. The seeds of this change were laid in an obscure case in Brussels from a decade ago. The case provided a radical interpretation of a standard provision in sovereign debt contracts that everyone used (the pari passu clause), but almost no one understood. For about a decade or so, the implications of that case were largely dismissed by the pooh bahs of the sovereign market. No one else would follow this outrageous Belgian decision, they said. That is, until October 26, 2012, when the theory from that Brussels litigation found favor with a three-judge panel of the Second Circuit in New York — arguably the most sophisticated court on business matters anywhere. That case, that has been occupying the pages of the financial papers for some time now, and is the centerpiece of the most recent issue of the Capital Markets Law Journal, is NML Capital v. Republic of Argentina.

To reiterate, the basic enforcement problem with sovereigns is that sovereigns themselves are hard to sue and harder still to enforce against (most of their assets tend to be on their home soil). Enterprising creditors though, figured out that while they might not be able to get at the sovereigns themselves, they could perhaps get at others who the sovereigns cared about, who were less able to protect themselves (any fan of movies about the mafia and its enforcement techniques will immediately grasp the basic idea). Ordinarily, we suspect that a court would not have gone down the path of enabling creditor action of this type. But the defendant in this case is special — it is the Republic of Argentina, that (some might say) has been doing its best to aggravate and annoy the federal courts in New York for over a decade where unpaid creditors have been litigation ever since Argentina’s mammoth default a decade ago. NML Capital v. Republic of Argentina allows the creditors to get at the third parties; in particular, financial intermediaries, but maybe also other creditors who the Republic is choosing to pay while stiffing the holdouts. If NML v. Argentina holds up on appeal — and, as of this writing, it has held up well — this will mark the most fundamental change in sovereign debt in multiple centuries. These debts will now be enforceable. It still won’t be easy to enforce, but it won’t be impossible.

To show how this case has already had an impact on the direction of future events, on 4 March 2013, just a few weeks ago, the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada was on the receiving end of a request that third parties be enjoined, just as they were in NML. And this injunction was not sought by some hedge fund in Greenwich, Conecticut. It was requested by the Taiwanese Ex Im Bank. It may not be that long before we see suits against other nations who have long unpaid debts. Rumors of the potential impact of the NML decision seem to have even trickled down to the market for antique bonds. The owner of my favorite antique bond shop tells me that defaulted Chinese and Russian bonds from the early part of the twentieth century have increased in price in recent months; and particularly the ones with pari passu clauses (yes, she said “pari passu”). Somebody out there thinks that the probability of recovery on these bonds has just increased. I do wonder whether their excitement will wane somewhat when they tackle the statute of limitations issue.

And then there is Cyprus. On Friday, 15 March 2013, European leaders trespassed on consecrated ground. They insisted that Cyprus impose losses — euphemistically dubbed a “solidarity levy” — on insured depositors with Cypriot banks as a condition to receiving EU/IMF bailout assistance. Cyprus was in deep crisis thanks to its oversized banking sector. Contrary to anything anyone expected (other than perhaps the nincompoops in the room that Friday night), Cyprus decided not only to go after bank deposits, but also insured deposits. And at the same time, it also decided that it would pay its bonds — a sizeable portion of which were rumored to be held by foreign hedge funds — on time and in full. Faced with almost universal shock and criticism for its first decision, Cyprus quickly backed off its first plan (its legislature did not even give the plan a single vote), and has now put in place an alternate plan that primarily pursue uninsured depositors in some of its weakest banks (for some bizarre reason, the bondholders still get paid in full). It is not clear that the current plan will suffice, given the damage that the announcement of the first plan and the general move toward chasing deposits for debt relief has done to the Cypriot banking sector (the key industry for that small economy). In other words, Cyprus will probably need more debt relief than it had first calculated and the bondholders may yet get whacked. But, for purposes of this note, I’ll say just this: Wow.

This is an updated and expanded version of the Editor’s Note in the current issue of Capital Markets Law Journal.

Mitu Gulati is the North America Regional Editor (March 2013) for Capital Markets Law Journal. He is a Professor at Duke University. His research interests are currently in the evolution of contract language, the history of international financial law and the measurement of judicial behavior.

Capital Markets Law Journal is essential for all serious capital markets practitioners and for academics with an interest in this growing field around the World. It is the first periodical to focus entirely on aspects related to capital markets for lawyers and covers all of the fields within this practice area: Debt; Derivatives; Equity; High Yield Products; Securitisation; and Repackaging. With an international perspective, each issue covers articles and news relevant to the financial centres in the US, Europe and Asia.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Sovereign debt after March 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembering Jack the Ripper

By John Randolph Fuller

From April 1888 to February 1891, history’s most infamous cold case emerged when a series of 11 murders ripped through London’s working-class Whitechapel district. All of the murdered were women, and most were prostitutes. Whitechapel was one of the poorest areas in London and by the 1880s some of England’s grimiest industries, such as tanneries and breweries, had become established there. Poor Londoners, rural English folk, and immigrants crowded in looking for work, but the district’s poverty was so overwhelming, many of the women who found themselves there became prostitutes, living and dying in squalid anonymity.

These conditions made Whitechapel the perfect hunting ground for killers. Of the 11 murders committed, five murders of prostitutes were attributed to a person called Jack the Ripper. The Ripper probably killed more than five women, but only these could be directly connected to him. The crimes were shocking and fascinating: the shock brought attention to the plight of Whitechapel’s poor which led to some transitory social reforms, but the fascination brought attention to the crimes of Jack the Ripper into the 21st century.

Jack the Ripper’s murders have been the subject of a slew of fiction and non-fiction books, films, short stories, graphic novels, and web pages. The murder even got his own “ology,” with people studying the murders calling themselves “Ripperologists.” Every few years, it seems, someone arrives with a new theory about the Ripper’s identity or some “startling new” evidence. In 2002, crime novelist Patricia Cornwell published a controversial book offering up artist Walter Sickert as Jack the Ripper. In 2012, author John Morris insisted Jack was a woman. Another researcher insists the Ripper was an American murderer named H.H. Holmes. The suspect list doesn’t end there. Lewis Carroll is on it, along with the Duke of Clarence, Sir John Williams, and on and on.

Why do we still care? Serial killers and murderers are at work somewhere in the world every day. For example, since 1993, hundreds of women in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico have been routinely killed, with some being dumped into mass graves. The explanations are prosaic: jealousy, drugs, domestic violence, gang wars, robbery, rape. Some may be the product of a serial killer, but so many women have been murdered, it’s hard to tell. The police make arrests, but the murders continue. This story and others like it have been repeated for a couple of decades, but those murders don’t seem to have the appeal of Jack the Ripper. Why?

Is it the lack of a catchy moniker for the killers? “Jack the Ripper” does have a ring to it. Is it the gruesomeness of the murders? The Ripper not only killed his victims, he eviscerated them with surgical precision. Whoever the Ripper was, he knew his way around a human corpse. Is it the era? Victorian London was certainly an evocative place, and Victorian Whitechapel is stuck with all the sooty baggage the term “Dickensian” couldn’t carry. Whitechapel was much as one Ripper suspect was described: “of shabby genteel.”

The scores of years that separate us from the Whitechapel murders might make the whole business seem gloomily romantic to us, but it was terrifying to those who lived through it. Although serial murder had doubtless been committed prior to 19th-century England, the Ripper murders were systematic and one of the first times the public could really get its hands on all the juicy details. News about the murders were not just passed by word of mouth, they were printed in newspapers along with photographs of the victims. Both the murderer and the victims became individuals in the minds of the public. It was just the killer that they couldn’t put a face on.

It can be argued that the traditional systems of English—and by extension, American—justice has something to do with the Ripper’s popularity. These systems evolved to focus on the individual offender and his or her rights: the police are under pressure to arrest the person who is actually responsible, not just anyone. (The police in London arrested several people for the murders, but had to let them go.) The courts are under pressure to convict the correct suspect. Everyone looks foolish when suspects are in jail, and the slaughter continues. These factors, combined with a freewheeling media that publicizes any new information it can get, tend to individualize the offender.

Recall that 11 women were murdered between 1888 and 1891, but only five were attributed to Jack the Ripper. Who killed the other six women? Many Ripperologists say those, too, were the work of Jack, but others disagree. Two or more killers might have been at work separately, or “Jack the Ripper,” might have been several people working together. But the public likes to imagine the killer as a single person, an individual. It is much easier to put a face on, and a personality into, one person rather than many. It is thrilling to imagine one person bursting with that much evil.

We will never fully understand the Ripper’s methods or motive, or why the murders stopped, although most criminologists would say that serial killers only stop when they can no longer kill. They are either dead or incarcerated. It is unlikely that Jack the Ripper chose to stop killing. Something stopped him, but nothing will stop us from wondering who he was.

John Randolph Fuller is Professor of Criminology at the University of West Georgia and author of Juvenile Delinquency: Mainstream and Crosscurrents, Second Edition.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Jack the Ripper’s “Dear Boss” letter (part 1) postmarked 25 September 1888. (National Archives MEPO 3/142). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Remembering Jack the Ripper appeared first on OUPblog.

Is stock market trading good for society?

Short-term stock traders — such as hedge funds — have come under fire for pursuing their own profits rather than the long-run health of companies they invest in. The recent financial crisis added fuel to flames, but they had started burning several decades earlier. In the 1980s, many commentators argued that Japan’s economic success resulted from shareholders taking long-term stakes and thus having incentives to improve their firms’ long-run health. They thus pushed the government to take actions to reduce the stock market’s “liquidity” — the ease with which investors can trade their shares. These calls have resurfaced in the recent crisis, through calls for transactions taxes and short-sales restrictions to dissuade “excessive” trading.

The Costs of Liquidity — The Traditional View

The traditional view is that liquidity undermines a firm’s corporate governance. Under this view, blockholders (large shareholders) can improve governance through engaging in direct intervention, otherwise known as “voice” — for example, removing an underperforming manager or blocking a misguided acquisition. But intervention is costly. Thus, blockholders may choose to simply sell their shares and walk away from a troubled firm. Liquidity makes selling easier, and thus discourages blockholders from sticking around and improving the firm’s long-run health.

The Benefits of Liquidity — The Modern View

But it is far from clear that liquidity is detrimental to governance — and thus to society. Indeed, Japan’s “lost decade” of the 1990s raised doubts about the low-liquidity model. The theoretical literature has identified two major benefits of liquidity. First, liquidity makes it easier for shareholders to acquire a block to begin with (Kyle and Vila (1991), Kahn and Winton (1998), Maug (1998)). By encouraging large shareholders to form, it facilitates voice. Second, Admati and Pfleiderer (2009), Edmans (2009), and Edmans and Manso (2011) show that the act of selling one’s shares (engaging in “exit”), far from being the antithesis of governance, can be a governance mechanism in itself. Such sales drive down the stock price, which hurts the manager because his pay depends on the stock price. The threat of exit induces him to maximize value in the first place.

What Does The Data Say?

With theoretical arguments for the desirability of liquidity being on both sides, it is ultimately an empirical question. Thus, it is to the data to which we turn. We analyze how liquidity affects both the decision to acquire a block and the choice of governance mechanism (exit or voice) once the block has been acquired. We study a particular type of blockholder — activist hedge funds — because they are unconstrained by legal restrictions and thus have both voice and exit at their disposal. Overall, we uncover a positive effect of liquidity on governance.

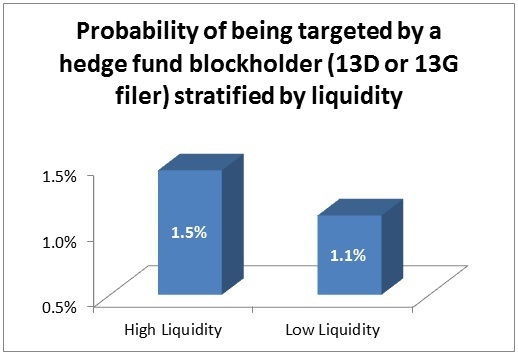

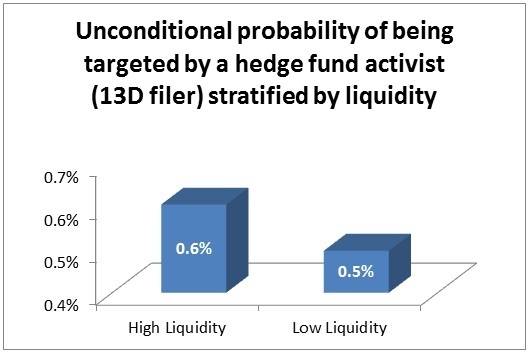

First, liquidity increases the likelihood that an activist hedge fund acquires a block (a stake of at least 5%) in a firm. To address concerns that there could be reverse causality (governance causes liquidity, rather than liquidity causing governance), or omitted variables driving both governance and liquidity, we use the decimalization of the US stock exchanges in 2001 as a natural experiment. This event led to a sudden increase in liquidity that was not caused by changes in governance.

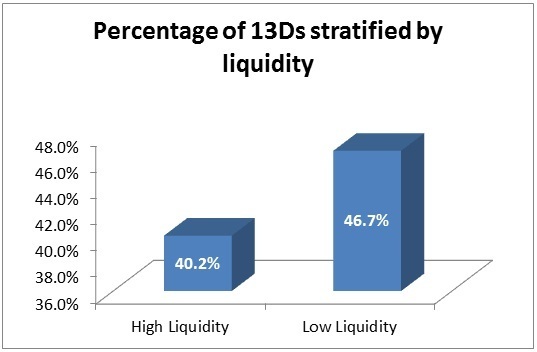

Second, liquidity reduces the likelihood that the hedge fund files a Schedule 13D (which conveys an activist intent) upon block acquisition, and correspondingly increases the likelihood that it files a Schedule 13G (which conveys a passive intent). This finding is consistent with the traditional view that liquidity weakens governance as it discourages voice. However, it is also consistent with the “exit” view that liquidity merely causes a blockholder to adopt a different form of governance — exit rather than voice.

Third, we find that a 13G finding indeed represents a governance mechanism. It leads to increases in both stock price and operating performance, particularly in liquid firms. These results support the “exit” view that the 13G filings, that are encouraged by liquidity, represent governance through exit rather than the abandonment of governance altogether (as argued by the traditional view).

Our final finding concerns voice. Our first result, stated earlier, was that liquidity increases the likelihood of block acquisition, but our second result was that it decreases the likelihood of a 13D, conditional upon block acquisition. We find that the first effect outweighs the second. Thus, liquidity increases the unconditional incidence of voice. Coupled with its positive effect on exit, liquidity has an overall beneficial effect on governance.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that policymakers should not rush into regulations that inhibit trading. It is through trading that investors can acquire a large stake to begin with, and also punish an underperforming firm by selling their stake.

More broadly, our recent paper contributes to a recent literature on the real effects of financial markets. The traditional view (e.g. Morck, Shleifer, and Vishny (1990)) is that financial markets are simply a side-show, that passively reflect a firm’s fundamentals — for example, a fall in the stock price reflects a deterioration in firm performance. This newer literature, surveyed by Bond, Edmans, and Goldstein (2012), shows that stock prices actively affect a firm’s fundamentals — a fall in the stock price exerts governance on the manager by worsening his compensation and reputation; the threat of such a fall induces the manager to exert effort. Thus, policymakers should take into account the effects of financial markets on real economic activity when designing regulations.

Alex Edmans is an assistant professor of finance at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, a Faculty Research Fellow of the National Bureau of Economic Research, and a Research Associate of the European Corporate Governance Institute. Vivian W. Fang is an assistant professor of accounting at the Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota. Emanuel Zur is an assistant professor of accounting at the Zicklin School of Business, Baruch College. They are the authors of the paper “The Effect of Liquidity on Governance” in the new issue of The Review of Financial Studies, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

The Review of Financial Studies is a major forum for the promotion and wide dissemination of significant new research in financial economics. As reflected by its broadly based editorial board, the Review balances theoretical and empirical contributions. The Review is sponsored by The Society for Financial Studies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Is stock market trading good for society? appeared first on OUPblog.

Unearthing Viking jewellery

There’s a lot we still don’t know about the Vikings who raided and then settled in England. The main documentary source for the period, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, simply tells us that Viking armies raided Britain’s coastline from the late eighth century. Raiding was followed by settlement, and by the 870s, the Vikings had established a territory in the north and east of the country which later became known as the ‘Danelaw’. Here, the Chronicle famously records, Scandinavian armies ‘shared out the land… and proceeded to plough and to support themselves’.

Despite over 50 years of research, many fundamental questions about the Scandinavian settlements remain unanswered: which areas of England saw the greatest settlement? How many settlers were there? Did they get on with the locals? Were they all men? Until recently, there was little in the physical record to provide answers. Archaeological traces of Scandinavian settlement were notably few: just a handful of Scandinavian-style burials and rural settlements have been found in England, for instance, while the Scandinavian contribution to urban development and certain strands of material culture, such as stone sculpture, remains elusive.

Within the last 20-25 years, this picture has changed dramatically. Thanks largely to metal-detecting, there has been an explosion of new finds of Viking-Age metalwork recovered from areas of known Scandinavian settlement. Surprisingly prominent within the new finds is female jewellery in Scandinavian styles: brooches and pendants worn by women in everyday dress. To date, over 500 such items have been found, scattered across large swathes of rural England.

The date of the jewellery chimes exactly with written accounts of the settlement (c. 870-950). Its careful study reveals that while some items were made locally after a Scandinavian fashion, others are likely to have been imported from the Scandinavian homelands, probably on the clothing of female settlers. Although Anglo-Saxon women also wore brooches, they were of a very different style to those favoured by Scandinavian women, so it’s clear that the new jewellery finds represent a distinctly ‘foreign’ dress element. The jewellery being unearthed in England is strikingly similar to that found in Scandinavia, particularly its southern regions: there are disc, trefoil, lozenge, oval, and bird shaped brooches decorated with animals and plants from the Scandinavian art styles of Borre, Jellinge, Mammen and Urnes. Encountering women on a walk around tenth-century Norfolk, you could be forgiven for thinking that you were in Denmark.

Viking-Age Scandinavian-style brooches from England

The discovery of such artefacts is unexpected, not only because such jewellery was unknown in England a generation ago, but also because it helps to elucidate a population group with has, until now, been largely invisible. Faced with a dearth of both archaeological and written evidence for Scandinavian women in England, historians have tended to assume that settlement was carried out entirely by men, who took wives among the local population. The jewellery offers the first tangible archaeological evidence for a significant female Scandinavian population in Viking-Age England, potentially numbering in the thousands. In this way, it is revealing the presence of women we never expected to see.

Women were not merely participants in the settlement process; they were active agents in negotiating relationships with the existing, Anglo-Saxon population. Their jewellery became a platform for the expression of cultural values, usually in a way that maintained Scandinavian traditions. One observable trend is that female dress in the Danelaw preserved Scandinavian preferences for particular brooches long after they had fallen out of fashion in the homelands. This deliberately archaising suggests that articulating historical ties via jewellery was important in a new settlement context, when cultural memories were likely to be challenged. The fact that it was done through women’s dress highlights a role for women as bearers of cultural tradition in Danelaw society.

The jewellery also provides a fresh perspective on one of the most elusive of topics regarding the Viking settlements, namely, their location. We tend to think of Yorkshire and the north-east Midlands as Viking hotspots, due in part to the areas’ Scandinavian-style place-names and stone-sculpture (as well as the success of the Jorvik Viking centre). Yet female jewellery here is rare, being concentrated instead in rural Norfolk and Lincolnshire. These areas are not commonly associated with Viking activity, but it is clear that they were exposed to strong Scandinavian cultural influence, at least in terms of female dress. Of course, the distribution pattern has to be interpreted with care: jewellery is eminently portable, and levels of metal-detecting can vary from county to county. Nonetheless, it does seem that East Anglia and Lincolnshire were vibrant centres of Scandinavian culture in ninth- and tenth-century England, to an extent not previously recognised. Once again, the jewellery shines new light on this historically dark period of British history, revealing the presence of peoples in areas we never knew were there.

Jane Kershaw is a British Academy Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at University College London. Jane Kershaw is the author of Viking Identities: Scandinavian Jewellery in England (OUP, 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Both images © Norfolk County Council; do not reproduce without permission.

The post Unearthing Viking jewellery appeared first on OUPblog.

April 28, 2013

The latest developments in cardiology

What is the relationship between atherosclerosis and acute myocardial infarction? How do aldosterone blockers reduce mortality? What steps are doctors taking toward personalized cardiac medicine? What are the new drugs and devices to treat hypertension? What is salt’s role in the human diet? The international cardiology community examined these questions and more at the Cardiology Update 2013 in Davos, Switzerland earlier this year.

A two-member video team from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) was also there to conduct interviews with the thought leaders in the field as part of the MyCardio interview series. The ESC and European Heart Journal are now present at all the major cardiology congresses worldwide to record these MyCardio interviews and almost 200 interviews available on the European Heart Journal website, covering a wide spectrum of topics in cardiology.

A selection of the interviews for Cardiology 2013 is presented below.

Salim Yusuf on salt’s implications for cardiovascular health

Click here to view the embedded video.

Franz Messerli on hypertension

Click here to view the embedded video.

Joseph Loscalzo on personalized cardiovascular medicine

Click here to view the embedded video.

Peter Libby on atherosclerosis, inflammation, and acute myocardial infarction

Click here to view the embedded video.

Bertram Pitt on the history of Cardiology Update in Davos

Click here to view the embedded video.

The European Heart Journal is an international, English language, peer-reviewed journal dealing with Cardiovascular Medicine. It is an official Journal of the European Society of Cardiology and is published weekly. The journal aims to publish the highest quality material, both clinical and scientific, on all aspects of Cardiovascular Medicine. It includes articles related to research findings, technical evaluations, and reviews. In addition it provides a forum for the exchange of information on all aspects of Cardiovascular Medicine, including education issues.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The latest developments in cardiology appeared first on OUPblog.

‘No choice for you’ according to the ACMG

The American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) has recently published recommendations for reporting incidental findings (IFs) in clinical exome and genome sequencing. These recommendations advocate actively searching for a set of specific IFs unrelated to the condition under study. For example, a two-year-old child may have his (and his parents’) exome sequenced to explore a diagnosis for intellectual disability and at the same time will be tested for a series of cancer and cardiac genetic variants. The ACMG feel it is unethical not to look for a series of incidental conditions while the genome is being interrogated, conditions that the patient or their family may be able to take steps to prevent. This flies in the face of multiple international guidelines that advise against testing children for adult onset conditions. The ACMG justify this as “a fiduciary duty to prevent harm by warning patients and their families.” They conclude that “this principle supersedes concerns about autonomy,” i.e. the duty of the clinician to perform opportunistic screening outweighs the patients right not to know about other genetic conditions and their right to be able to make autonomous decisions about testing.

Family have exome sequencing to determine son’s diagnosis

There is strength in the above argument if opportunistic genetic screening did indeed reveal an established predisposition to a treatable and preventable condition where steps could be taken to protect the individual or their family. But this isn’t the case with some of the conditions the ACMG insist on testing for. There are many apparently ‘disease causing’ variants that appear in healthy people with no evidence of disease, and in the absence of a strong family history it will be difficult to interpret some results. It is not too far fetched to imagine that, in the hands of a health professional who doesn’t understand the limitations of the testing, that a supposed BRCA1 gene fault will be identified in a women who is then advised to have preventative surgery to remove her ovaries and breasts. And yet in the absence of a family history, it is impossible to tell whether the BRCA1 gene fault is fully penetrant and whether there are any modifying genes at play.

The ACMG acknowledge “there are insufficient data on clinical utility to fully support these recommendations… and… insufficient evidence about benefits, risks and costs of disclosing incidental findings to make evidence-based recommendations”. Yet, they clearly felt the need to draw a line in the sand and create a starting point. This is a bold and fearless move. The result is that a set of conditions, genes and variants are listed, many of which will reveal uncertain pathogenicity in the absence of a family history. Moreover, in many cases, there is no screening program available (what should be offered to a child with a P53 mutation? There is no universal agreement on whether screening for rhabdomyosarcoma is appropriate). The intent was to identify “disorders where preventative measures and/or treatments were available” but the reality falls short somewhat.

Finally, the ACMG “Working Group encourages prospective research on incidental or secondary findings and the development of a voluntary national patient registry to longitudinally follow individuals and their families who receive incidental or secondary findings as part of clinical sequencing and document the benefits, harms and costs that may result.” In effect, what they are saying is that we don’t really know what the impact of this technology will be, and only time will tell whether our risk predictions are correct. Given such uncertainty and also the fact that many of the families and individuals who will be accessing this technology are incredibly vulnerable (by virtue of their desperate need for a diagnosis for example, for a developmental disorder), it strikes us that this all should actually be part of a research project and not offered as a clinical service. Under the guise of ‘research’ this makes much more sense. What do you think? If you want to contribute to other discussions about ethics and genomics, see our survey.

Consider the ACMG guidelines with the following fictitious case study in mind….

Case study

Bobby is a severely disabled six-year-old. He has a learning disability and hyperactivity, and is incontinent. Numerous paediatricians have seen the family over many years, but existing tests haven’t led to a diagnosis. Bobby’s parents are anxious to have a name for his condition. Without an actual diagnosis it is more challenging to access the educational and respite care he needs.

At their latest paediatric review, Bobby’s parents are given the first glimmers of hope: there is a new test, an exome sequence, that will explore the subtle changes in Bobby’s genes to (hopefully) reveal previously undetected genetic causes for his condition. However, there is a catch — the testing comes in a package where other conditions are also explored at the same time. The parents aren’t interested in anything else and they are confused when the paediatrician tells them Bobby will be tested for a whole set of adult-onset cancers as well as cardiac conditions. The paediatrician explains that these latter conditions are likely to be totally unrelated (‘incidental’) to Bobby’s condition, may not be relevant until Bobby grows up and also it may not be possible to tell with any certainty what the actual risks are of developing them. The parents are surprised — isn’t this a paediatric clinic? Why is a paediatrician talking to them about adult conditions completely outside her area of expertise?

The paediatrician explains that this is just the same as having a full blood count done or an X-ray; there is always the chance of picking up something unexpected. But, the lab will be specifically searching for a set of additional conditions, there doesn’t seem to be much that is ‘incidental’ about this. ‘Call it opportunistic screening’ says the paediatrician’; however, what shocks Bobby’s parents is the fact there is no choice. In order to access the exome sequencing technology they have to receive information on a set list of conditions, there is no opt-out only an opt-in. So, they have to proceed.

Some months later they receive a telephone call from their paediatrician, the exome did not reveal an obvious genetic diagnosis for Bobby’s disabilities however, after several weeks of additional exploratory work by the laboratory staff, they reported a change in a gene called ‘P53’ that is ‘likely’ to given him an increased risk of cancer. The lab had spent a long time looking through the medical literature. Although the gene change looked as if it should be significant in that cancer was possible, the fact that no-one in the family had already had cancer (and the family was large with many people living well into old age), it was difficult to know what this actually meant for Bobby and his parents, and whether cancer screening would be necessary or not. Bobby’s parents are stunned, they proceeded with testing that they had no choice about and now have to deal with uncertain results together with an uncertain plan of action. Should they be worrying about this result or not? Does it have implications for other members of the family? The paediatrician isn’t sure.

A version of this article originally appeared on the Genomethics blog.

Anna Middleton is the author of Getting the Message Across: Communication with Diverse Populations in Clinical Genetics. She has had two parallel careers, the first as a registered genetic counselor working in various regional clinical genetics services in the UK and the second as a social scientist exploring the ethical implications of genetic and genomic technologies. She has a PhD in Genetics and Psychology and is currently working as an Ethics Researcher at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, UK. She has been the Vice-Chair of the Genetic Counselor Registration Board and on the editorial board for the Journal of Genetic Counseling (US).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Genomethics blog.

The post ‘No choice for you’ according to the ACMG appeared first on OUPblog.

The physiological, psychological, and biological reasons for crying

Are humans the only species to cry for emotional reasons? How are tears linked to human evolution and the development of language, self-consciousness, and religion? Which parts of the brain light up when we cry? How is crying related to empathy and tragedy? Why can some music bring people to tears?

Below, you can listen to Michael Trimble talk about the topics raised in his book Why Humans Like to Cry: Tragedy, Evolution, and the Brain. This podcast is recorded by the Oxfordshire Branch of the British Science Association who produce regular Oxford SciBar podcasts.

Listen to podcast:

[See post to listen to audio]

Or you can download it directly from Oxford SciBar podcasts.

Michael Trimble is Emeritus Professor of Behavioral Neurology at the Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London. He is the author of Why Humans Like to Cry: Tragedy, Evolution, and the Brain and The Soul in the Brain: The Cerebral Basis of Language, Art, and Belief. He received a lifetime achievement award from the International Neuropsychiatry Association.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology and neuroscience articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The physiological, psychological, and biological reasons for crying appeared first on OUPblog.

April 27, 2013

Mary Wollstonecraft: The first modern woman?

By Gary Kelly

A recent book on the essayist William Hazlitt calls him the ‘first modern man’. If he was, perhaps Mary Wollstonecraft was the first modern woman. By ‘modern’ I mean someone with ideas on how to cope with what sociologist Anthony Giddens calls ‘the consequences of modernity’. These include frighteningly accelerated, seemingly uncontrollable change; heightened risk of all kinds, from food supply through epidemics to weapons of mass destruction and ecological catastrophe; increased dependence on ‘abstract systems’ of unknowable complexity, from banking to government, medical science to the economy; greater migration, voluntary and involuntary, across countries and continents, classes and cultures; and, in meeting these challenges, increased dependence on ‘pure’, supposedly unselfish relationships in private and social life and on a flexible yet stable, self-reflexive and adaptable personal identity.

Wollstonecraft lived through the onset of modernity as Giddens defines it. She observed personally, analyzed incisively, and looked beyond one of modernity’s major initial crises, what many then saw as the greatest social and political cataclysm in history. She saw the blood of the guillotine on the Paris pavements and protested, at her peril. More, she understood this cataclysm from the situation of her sex, what she called ‘the wrongs of woman’, and protested, despite the peril.

Wollstonecraft certainly opposed unmodernity — the ‘Old Order’, the ancien régime — and promoted modernisation, but like her daughter Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein, she understood its costs, especially to the marginalized and powerless. Among other things, Frankenstein gave powerful mythic form to a vision of modernity as human catastrophe. Wollstonecraft tried to envisage a modernity that would benefit all, from which women and other marginalized groups would not be excluded and by which they would not be victimized.

Wollstonecraft certainly opposed unmodernity — the ‘Old Order’, the ancien régime — and promoted modernisation, but like her daughter Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein, she understood its costs, especially to the marginalized and powerless. Among other things, Frankenstein gave powerful mythic form to a vision of modernity as human catastrophe. Wollstonecraft tried to envisage a modernity that would benefit all, from which women and other marginalized groups would not be excluded and by which they would not be victimized.

To this end, as a self-educated, militantly independent young woman, she set out to become what she called the ‘first of a new genus’, a ‘female philosopher’. Many at the time would have derided this phrase as an oxymoron, but by it she meant a comprehensive social, cultural, and political critic, what we now call a public intellectual, representing women in particular and thereby all of the exploited and oppressed.

As a ‘female philosopher’ Wollstonecraft communicated her vision of modernity, responding to the prolonged crisis of her time, in a wide range of writing including education manuals, novels, criticism and essays, political and social polemic, historiography of the present, and political travelogue. Part of this political and cultural work required both modernizing these forms, reinventing them better to serve her vision of modernity, and inventing a new form of discourse, that of the ‘female philosopher’ rather than of the intellectual woman as some kind of ‘honorary man’. So radical was her invention, so modern, that still today many find it confused and confusing rather than ahead of its time, and perhaps ahead of ours.

Hazlitt knew Wollstonecraft’s circle of radical reformers, intellectuals, artists, writers, and publishers and what they tried to achieve. He circulated among such a circle of his own, one that included Byron, Keats, Leigh Hunt, and Percy and Mary Shelley, as well as artists and intellectuals, modernizers of all kinds, in contending interests. Hazlitt’s liberal views, increasingly celebrated in recent years, owed much to those of Wollstonecraft’s circle, with their zeal for social justice, modernization of institutions, political reform, democratic access to the arts, and concern for human value in all aspects of life, of all forms of life.

Notoriously, however, Hazlitt did not attend to Wollstonecraft’s feminism; in fact, many today see him as a misogynist. Yet I think Hazlitt’s distinctive, celebrated, and modern-seeming style, with its sharp declarations, vivid illustrations, sudden turns, personal tone and reference, lyrical passages, sarcasm and satire, owed much to Wollstonecraft’s. At the least, it was a later correlative to hers.

Wollstonecraft, much more than Hazlitt, was relegated after her death to the margins of literature and public discourse, perhaps for similar reasons; perhaps the first modern woman and man were too ‘strong’ for what became an influential Victorian and early twentieth-century consensus. Wollstonecraft was rediscovered by successive feminist movements, most recently in the 1970s; Hazlitt has received renewed attention in the past decade as a public intellectual for what Giddens calls ‘late’ modernity, and others ‘post-modernity’, our age of crisis, of ‘recession’, and ‘austerity’, and worse. In this we need all the help we can get. We could do worse than renew a conversation with the first modern woman.

Gary Kelly is Distinguished University Professor in the Department of English and Film Studies at the University of Alberta, Canada. He has edited Mary Wollstonecraft’s Mary and The Wrongs of Woman for Oxford World’s Classics, and published a book on her radically innovative style of thinking and writing, Revolutionary Feminism. He is General Editor of the ongoing multi-volume Oxford History of Popular Print Culture.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Mary Wollstonecraft: The first modern woman? appeared first on OUPblog.

Mediation and alternative dispute resolution

Why compromise? Increasingly in civil litigation there are no winners — not even the lawyers, following the review and implementation of Sir Rupert Jackson’s report into costs. The question is rapidly being re-phrased as “Why litigate?”

Prior to 1 April, lawyers were able to work on a “no win, no fee” basis and recover a percentage uplift and after the event (ATE) insurance premium on top of their fees if the claim was successful. Now not only have the playing field and goal posts changed, but the game itself has, following the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO). Now the resources available for justice are limited, and the needs of the litigant have to be balanced against the resources available. This is recognised in the new overriding objective of the Civil Procedure Rules.

To start with, the funding options for claimants have changed. Now, lawyers cannot recover their success fee or ATE insurance premium from the defendant, but must instead look at other funding options, such as Damages Based Agreements (payment from damages) or Conditional Fee Agreements (where the success fee is taken out of damages, up to a limit). This results in claimant lawyers taking more risk. On the other hand, the changes also affect defendants, such as the 10% increase in general damages, the changes to CPR Part 36 regarding offers to settle, and Qualified One Way Costs Shifting in certain cases (whereby claimants can bring claims without the risk of having to pay the defendants’ costs if they lose). Parties in multi-track cases have to prepare a budget for the Court, estimating what the costs are likely to be in a particular case and the Court then approves a limit. Legal aid is being cut back as well, particularly in family cases, and the Ministry of Justice is under to pressure to cut its budget and to make Court users pay for the Court service. There is a sense in which mediation is being made to fill the void. There is no longer any unfettered right to litigate and mediation is seen as a way of reducing the cases that come before the Court. The former Justice Minister, Jonathan Djanogly was quoted as saying, in the context of family law:

“There’s been a 20% uptake in mediation and we know that of those who go through publicly funded mediation, 70% will have a successful outcome….It’s a cheaper process — one that takes a fifth of the time of going to court and it’s much less contentious…. 90% of people sort out their own problems, but 10% of people go to court. We think less of them should be going to court and more of them taking their own lives into their own hands, and mediation is a way of facilitating that.”

Eighth of Henry Holiday’s original illustrations to “The Hunting of the Snark” by Lewis Carroll. This illustration covers Fit the Sixth: The Barrister’s Dream. The Snark is in the foreground, in barrister’s robe and wig, and is acting to defend his client.

The Civil Procedure Rules have also changed, introducing a new test on proportionality of costs and tougher case management powers and low recoverable fixed costs in personal injury claims which are administered through the “portal.” Faced with these changes, is it any wonder that there is a renewed interest in finding alternative ways to resolve disputes? This is where mediation and other forms of alternative dispute resolution come in. Sir Rupert Jackson is a fan of mediation, judging by his report and recent judgments, so it appears to be coming of age. The Courts are increasingly willing to impose sanctions on those who unreasonably refuse to mediate, or negotiate and the Courts have their own mediation schemes in place, such as the Court of Appeal compulsory referral to mediation scheme. The successful small claims mediation pilot, applying to all non-personal injury small claims in the County Court, is being extended for a further 6 months to September 2013 and now takes in cases issued through the County Court Bulk Centre in Northampton and Money Claims Online. Cases issued with a value of under £5,000 are referred automatically to a Court Service mediator, who will try to save the parties’ and the Court’s time by seeing whether the case can settle. It has been successful so far, reducing the claims that go forward to a small claims hearing by a significant amount, freeing up valuable time to deal with other cases. These mediations take place by telephone and it is likely that online mediation will become increasing common as well.

Many claims could be resolved more quickly and easily through Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) and mediation. In order to succeed, however, parties must be open to compromise and willing to give up their day in Court. Those that choose the alternative path often find it to be more fulfilling and less frustrating than litigation. Looking forward with a crystal ball, it is easy to see why mediation is likely to increase in future. The European Commission is favourable towards ADR, having approved the text of a directive concerning ADR and Online Dispute Resolution between consumers and traders. This follows on from the Mediation Directive, which in cross-border cases, seeks to encourage the uptake of mediation, by both protecting mediators from having to give evidence and ensuring that settlement agreements are enforceable.

The Civil Mediation Council is tentatively looking at whether there is any appetite to widen its scope, to accredit individual mediators, and to possibly set up a Mediation Standards Board, having issued a consultation document seeking views on the future direction. It seems inevitable that with the increased use of mediation, the general public will want to see mediators abiding by a code of professional conduct, like other professionals, and to have a route to complain about a mediator. There are also moves afoot to introduce a business ADR commitment, much like the Dispute Resolution Commitment (DRC), which already requires government departments and agencies to be proactive in the management of disputes, and to use effective, proportionate and appropriate forms of dispute resolution to avoid expensive legal costs or court actions. This includes adopting appropriate dispute resolution clauses in all relevant government contracts.

In order for alternative forms of dispute resolution to take hold, we need a change of culture, so that instead of issuing proceedings, parties consider instructing a mediator to resolve their dispute at the outset. There are a jigsaw of initiatives being introduced to encourage a change of culture and to increase the take up of alternative forms of dispute resolution.

Peter Causton is a solicitor at Berrymans Lace Mawer and commercial mediator. He is a contributor to The Jackson ADR Handbook and a member of the Law Society Civil Justice Committee.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: By Henry Holiday (1839-1927) after Lewis Carroll [Real name: Charles Lutwidge Dodgson] (1832-1896). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Mediation and alternative dispute resolution appeared first on OUPblog.

Freedom Day and democratic transition

Despite the recognized virtues of democratic rule, both for protection of personal rights and liberties and for economic progress, the current list of world governments still classifies 46 of all countries, or 25%, as dictatorships. Rulers in these existing dictatorial regimes resist the transition to democracy, often at a high cost each year in lives and resources. One would hope that the potentially sizeable benefits of democracy could be shared to the mutual advantage of the once ruling elite and the poor majority. The gains are there, why can’t they do a deal? The answer turns on the inability of a new democracy’s poor majority to credibly promise the elite that they will not be exploited once democracy becomes the new order.

Yet, in one of the most important political events of the 20th century, South Africa solved this problem. In April 1994, Nelson Mandela was elected President of the new Republic of South Africa, and on 11 October 1996, a democratic constitution was approved unanimously by the National Parliament with the full support of the once autocratic National Party. In President Mandela’s words the new constitution offered the citizens of South Africa “a democratic government… that (has) an inbuilt mechanism which makes it impossible for one group to suppress the other” (speech by President Mandela, Stellenbosch University, May 1991). That built-in mechanism was federal governance, of a particular kind.

How can federal governance using both democratically-elected national and state or provincial governments provide the essential protections for the elite needed for a peaceful transition from autocracy to democracy? Three elements are necessary. First, having given up political and military control, the old ruling elite will need to find its future influence in another way — through the economy, perhaps. Since land and machines can always be expropriated, it will have to come from the labor skills of the elite that the majority will need but cannot import or master quickly on their own. In South Africa these elite skills were found in the provision of public services, and in particular, in health care, education, and efficient public administration.

Second, the elite must be able to withhold these needed skills if the majority threatens to expropriate elite-owned land, nationalize elite-owned firms, or to set tax rates on income at excessive rates. It is often thought that the elite’s ability to migrate would be a sufficient deterrent to expropriation or excessive taxation. In South Africa, migration from the country has been modest. You cannot take land and machines with you when you leave, and for all but the most talented, comparable jobs in a new homeland may not be readily available.

What then is an alternative way to withhold needed talents? Perhaps a “strike” or a “work slowdown” organized through elite control over the provision of essential government services? But since the elite is now a political minority, it cannot be a country-wide slowdown. However, it can be a slowdown in one important part of the country where middle and upper income households might constitute a political majority. Local political control could be assured by a constitution that creates provincial governments and draws the provincial borders so that first, there are enough new (lower income) majority residents in the province so that the majority-run national government cares what happens to these constituents, but second, not so many that the middle and upper income households lose political control over the province. We call this requirement the Border Constraint and it must hold so that the elite controls at least one or two important provinces in the new democracy. In South Africa, that important province has become the Western Cape, home of Capetown and South Africa’s wine country. Further, so that this local control can be used as a credible deterrent to excessive national taxation, the provinces must be assigned responsibility for providing important public services. We call this requirement the Assignment Constraint. In South Africa, these constitutionally assigned services are primary health care, K-12 education, and the administration of social security payments.

President Bill Clinton with Nelson Mandela, 4 July 1993.

Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Third and finally, the elite-run provinces cannot become economic islands unto themselves, as indeed the National Party had originally proposed during constitutional negotiations. President Mandela and the ANC rejected this approach to federalism by insisting that all important taxing powers remain in the hands of the national government. But without significant taxing powers, how can provincial governments provide important public services? The answer is the last element in the design of the federal constitution: a clearly specified formula for sharing national tax revenues with the provincial governments. In South Africa’s constitution, this formula is called the “Equitable Share” and is recommended each year by a constitutionally protected commission called the Financial and Fiscal Commission composed of representatives from each of the nine provinces.

The elite’s expertise in the provision of important public services, empowered through an appropriately designed federal constitution, gave Nelson Mandela the “inbuilt mechanism” he needed to assure F.W. de Klerk and the National Party that their economic interests could be protected in the new democracy. Having fashioned a federal constitution for South Africa’s democratic transition, and it is holding so far, who has benefitted?

Crime and unemployment remain serious problems, but crime rates are no higher than those in many of the largest US cities and there is a thriving black market for those who are formally unemployed. Taxes on middle and upper income households have increased to finance expanded public services to lower income households, and there remains an important significant inequity in the distribution of education, health care, and infrastructures. All said, while pressures on education and other public services have continued to grow, tax rates are still below our estimates of maximal taxation and there have been no exploitive land transfers or wholesale nationalization of private capital. Adult disability and child mortality rates continue to fall, new lower income housing is being built, school enrollment is up, class sizes are shrinking, and literacy has increased. When we compare what lifetime earnings would have been for the majority of South Africans had apartheid continued (with negative growth!) to earnings today and into the foreseeable future, the typical poor majority resident has become 160,000 Rand ($20,000) richer and the typical elite resident about 350,000 Rand ($45,000) richer over their lifetimes.

To be sure, South Africa continues to face important challenges to its economic and political futures, but there is little doubt that by almost any measure of personal welfare, the average elite and majority resident are better off today than they might have been under the continuation of apartheid. Our argument here is that federal governance, appropriately constructed, made this possible. Perhaps South Africa’s experience holds lessons for others seeking a peaceful transition to a stable democracy.

Robert P. Inman and Daniel L. Rubinfeld are the authors of “Understanding the Democratic Transition in South Africa” in the American Law and Economics Review, which is available to read for free for a limited time. Robert Inman is the Richard K. Mellon Professor of Finance, Economics, and Public Policy at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. Daniel Rubinfeld is the Robert Bridges Professor of Law and Professor of Economics, Emeritus, University of California, Berkeley and Professor of Law, New York University School of Law. Professors Inman and Rubinfeld served as economic advisors to the Financial and Fiscal Commission and to the national government’s Departments of Finance, of Education, and of Welfare on matters of fiscal policy for the period 1994-2000.

The American Law and Economics Review is a refereed journal which maintains the highest scholarly standards and that is accessible to the full range of membership of the American Law and Economics Association, which includes practising lawyers, consultants, and academic lawyers and economists.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only politics and law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Freedom Day and democratic transition appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers