Oxford University Press's Blog, page 951

April 26, 2013

Closeted/Out in the quadrangles

“That was my radio show!” narrator David Goldman exclaimed, looking at copies of classified ads placed in the University of Chicago’s student newspaper during the late 1960s and early 1970s, when he was an undergraduate student. Goldman, a retired math teacher and one of the founders of the gay liberation movement at the University of Chicago, recently contributed his story to the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality (CSGS) research project Closeted/Out in the Quadrangles: A History of LGBTQ Life at the University of Chicago. During his interview, Goldman spoke at length about coming out in the late 1960s and gay student organizing at the University in the early 1970s. His interview is just the first of many we at CSGS hope to collect from LGBT alumni, faculty, and staff over the next two years.

Chicago Maroon newspaper (ca. 1970), University of Chicago Library.

Building on the success of a previous oral history and exhibition project documenting the experiences of women at the University of Chicago, Closeted/Out in the Quadrangles speaks to a vibrant and growing partnership between the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality and the University Archives at Special Collections Research Center, one aimed at building archival collections in gender and sexuality studies. With support from CSGS’s undergraduate oral history internship program and archives-based undergraduate seminars (created specifically for the Closeted/Out project), we expect to deposit more than one hundred oral histories to the University Archives by 2015.

While scholars have documented the University of Chicago’s rich and numerous contributions to the academic study of homosexuality, we actually know very little about the experiences of LGBTQ individuals and communities who have passed through the campus gates. Filling that knowledge gap is our team of undergraduate student interns, who bring an important dose of energy, enthusiasm, and insider knowledge about campus life to the Closeted/Out interviews. Molly Liu, a fourth-year Biology major who first trained in oral history methods for an African history course, notes:

The loose, undirected format of oral history means that I get to hear people’s stories without needing to dig for any particular piece of information, and in doing so I’ve felt like I’ve understood these people in some way. Their words about gay identity, the University, and Chicago in particular have given me a lot think about. Plus, it’s very fulfilling on a personal level to talk to LGBTQ alumni who are happy and successful.

Kelsey Ganser, a fourth-year History major who is completing an internship with the project while working on her senior thesis in Russian history, reflected on both the academic and personal value of her work:

Working [on the project] has given me the skills to conduct oral history interviews, which are frequently overlooked in my history courses. As a young queer person, through the project I have been able to connect to my history in a way that was never available to me before. The pleasant and easygoing interviews help me feel how strong and welcoming the gay community is, and the difficult ones help me appreciate how far we have come. I had never met an adult gay person until I came to college, so discovering our history through the life stories of other LGBTQ people has been hugely important for the development of my identity. In this regard, I don’t think I can overstate how much this project has influenced my personal understanding of queer identity and history.

Molly, Kelsey, and our other student interns have also found themselves working on the front lines of gathering new archival donations for Special Collections Research Center. As Cal State scholar David A. Reichard has discussed in the Oral History Review article “Animating Ephemera through Oral History: Interpreting Visual Traces of California Gay College Student Organizing from the 1970s,” oral histories not only help us interpret student ephemera, they also help us collect it. Our interns have returned from their interviews with photos, event flyers, stickers, zines, and promises of future loans and donations to the Closeted/Out project. Their friends and classmates have offered to save materials documenting current feminist and queer organizing on campus. And the courses we offer in conjunction with the Closeted/Out project have also brought new undergraduate users to Special Collections Research Center, where they find archivists and librarians eager to help them explore an activist and social history of LGBT life.

University of Chicago students marching at Chicago Pride (1991), Chicago Maroon collection, University of Chicago Photographic Archive, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

As our students continue to interview, we also begin work on plans for a campus exhibition showcasing our findings, scheduled for the Spring of 2015. Shortly thereafter, the LGBTQ oral history collection will be available to researchers at Special Collections Research Center.

Monica L. Mercado is a Ph.D. Candidate in U.S. History at the University of Chicago and a dissertation fellow at the University’s Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality, where she is a coordinator of the Center’s public history initiatives. Before coming to Chicago, Monica worked in exhibitions and programs at the Museum of the City of New York. You can find her musings on women’s and LGBT history, teaching, and Chicago’s unpredictable weather at @monicalmercado.

The Oral History Review, published by the Oral History Association, is the U.S. journal of record for the theory and practice of oral history. Its primary mission is to explore the nature and significance of oral history and advance understanding of the field among scholars, educators, practitioners, and the general public. Follow them on Twitter at @oralhistreview, like them on Facebook, or follow the latest OUPblog posts to preview, learn, connect, discover, and study oral history.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Closeted/Out in the quadrangles appeared first on OUPblog.

Looking at trees in a new way

If I have learned anything as a lifelong student of the world’s multitude of religious traditions, it is that reality for humans is malleable and quite varied — nothing is essential in human experience. Almost everything gets filtered through and shaped by a particular cultural lens. Something as simple as a tree is not so simple after all. From a biological perspective trees have much in common worldwide, but from a cultural perspective there exists an immense difference between them. Human perception and understanding of any aspect of the world seems to be determined largely by the particular interpretive lens through which it is viewed. Importantly, different cultural perspectives result in different experiences and behavior. What is a tree when seen from another cultural viewpoint? What range of interactive experiences is possible with it?

Historically tree worship has been a vital feature of much religious activity worldwide, and trees are still commonly found at the center of religious shrines in India. In this context they are typically regarded as powerful sentient divine beings with whom humans can have mutually beneficial relationships.

A religious shrine in India.

The personhood of trees is taken seriously as people interact with them in a variety of ways. The pipal or bodhi tree is often considered to be the most sacred tree in India. Buddha is said to have achieved enlightenment under this tree and many Hindus consider it to be an embodied form of the mighty god Vishnu.

The bodhi tree

Because of its highly beneficial medicinal qualities, the neem tree is frequently called the village pharmacy. It is commonly regarded as the body of the goddess Shitala. In some parts of India this tree is dressed with colorful cloth and a metal facemask is attached to the trunk of the tree as a way of honoring it and facilitating a more intimate connection with it.

The neem tree with a metal facemask attached

Banyan trees are often identified with the god Shiva and are associated with longevity and immortality, since they have the ability to live indefinitely. They send down aerial roots, which over the course of time become massive trunks that in turn send out aerial roots of their own, creating an ever-expanding and self-perpetuating forest. They too are the recipients of a wide range of religious offerings and worship.

A banyan tree

Trees are clearly amazing forms of life that have captured the human imagination in a number of ways. A question we might ask on this Arbor Day is: what possibilities would be available to us in our relationships with trees if we were to expand our understanding of them, inspired by the perceptions of our own ancestors or those of people living in different cultures today, such as the many tree worshipers of India?

David Haberman is Professor of Religious Studies at Indiana University-Bloomington. He is the author of People Trees: Worship of Trees in Northern India.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

All photos courtesy of the author.

The post Looking at trees in a new way appeared first on OUPblog.

Daniel Defoe, Londoner

By David Roberts

It’s one of the great misunderstandings in English fiction:

It happen’d one Day about Noon going towards my Boat, I was exceedingly surpriz’d with the Print of a Man’s naked Foot on the Shore, which was very plain to be seen in the Sand: I stood like one Thunder-struck, or as if I had seen an Apparition; I listen’d, I look’d round me, I could hear nothing, nor see any Thing.

A swift retreat to the ‘castle’ follows. With sleep come the nightmares: fantasies of pursuit by ‘savages,’ dreams of the devil himself setting foot out there on the sand. The Bible provides some comfort: Wait on the Lord, and be of cheer, he reads. Then, days later, the truth dawns. It was his own footprint.

This celebrated moment in the life of the runaway, castaway sailor of York called Robinson Crusoe is the more surprising and powerful because it was written by a man who spent most of his life in — and in one way or another writing about — a sprawling metropolis. What more paradoxical subject for the lifelong Londoner, Daniel Defoe, than the horror of thinking that the island you’d thought deserted might harbour another life, or the satisfaction of knowing that it didn’t?

Defoe is often described as a realist. Ian Watt’s seminal book, The Rise of the Novel, went so far as make his ‘realism’ a pre-condition for the development of the novel. But when it came to cities, and to London in particular, Defoe was often drawn to ghosts and shadows: to dreams of emptiness as much as crowds and the great business of daily life. As Edward Hopper found the essence of New York in stray people hunched over night-time drinks amid darkened streets, so the London of Defoe’s writing often turns out to be an inversion of the place his readers knew, perhaps because he knew it better than anyone else.

Defoe is often described as a realist. Ian Watt’s seminal book, The Rise of the Novel, went so far as make his ‘realism’ a pre-condition for the development of the novel. But when it came to cities, and to London in particular, Defoe was often drawn to ghosts and shadows: to dreams of emptiness as much as crowds and the great business of daily life. As Edward Hopper found the essence of New York in stray people hunched over night-time drinks amid darkened streets, so the London of Defoe’s writing often turns out to be an inversion of the place his readers knew, perhaps because he knew it better than anyone else.

Daniel Defoe was born in the parish of St Giles, Cripplegate, the son of a butcher, and grew up listening to the preachings of Samuel Annesley, a non-conformist pastor in Bishopsgate. Schooled at Newington Green by another non-conformist, Charles Morton, he went into business in 1685, dealing in hosiery. By 1688 he was a proud liveryman of the City of London. Future ventures would take him to France and Spain, to Hertfordshire and Essex, but he always returned to London and died there in 1731.

More than any other writer, his knowledge came from the bottom up. His taste for political diatribe landed him in Newgate prison; for his defence of religious dissenters he stood in the pillory during three July days in 1703 (people stood around with flowers, forming a guard of honour). Businessman, low-church militant, and journalist, his nose for the instincts and interest of ordinary people was a shock to writers who thought literature should imitate the noble forms of classical Greece and Rome. To read his prose is to experience not the choreography of a turn round St James’s Park, but the tumbling bustle of a walk through Cheapside.

Yet his greatest tribute to his home city is not the magnificent chapter on London in A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain, published in 1726, which celebrates the capital’s resources of money, trade, history and people. It is the book he had brought out four years earlier, in which he imagined what had happened when the city had been brought to the edge of oblivion during the Great Plague of 1665. A Journal of the Plague Year builds on a fascination with disaster that had gripped Defoe at least since 1708, when he published The Storm. Using old maps, mortality bills, government edicts, oral history and a host of other documents he pieced together a narrative that recreated the past in order to send out a dire warning about the future: if Londoners did not heed the threat of plague from Southern Europe, it could face extinction.

The result is an extraordinary hybrid of historical fiction and dystopian dreaming, the work of a man who could stand in the middle of a busy street and imagine himself, like Robinson Crusoe, perfectly alone.

Professor David Roberts teaches English Literature at Birmingham City University. He has taught at the universities of Bristol, Oxford, Kyoto, Osaka, and Worcester, and in 2008/09 he was the inaugural holder of the John Henry Newman Chair at Newman University College, Birmingham. He has published extensively in the fields of seventeenth and eighteenth century drama and literature, and is the editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year. He has previously written about disaster writing for OUPblog.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Daniel Defoe. By Michael Van der Gucht (Flemish, 1660-1725) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Daniel Defoe, Londoner appeared first on OUPblog.

Global warfare redivivus

By Charles Townshend

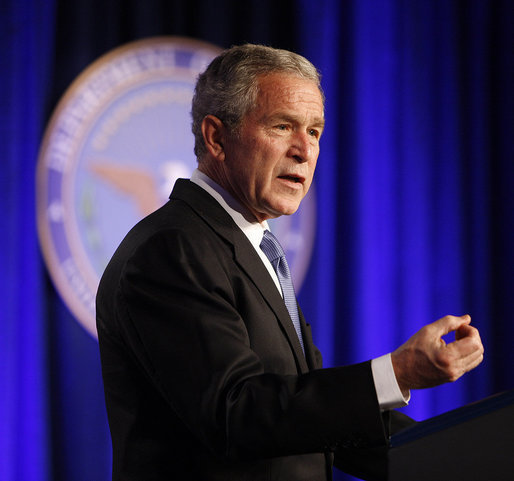

When the ‘global war on terror’ was launched by George W. Bush – closely followed by Tony Blair – after the 9/11 attacks, many people no doubt felt reassured by these leaders’ confidence that they knew the best way to retaliate. Some, though, found the global war concept alarming for several reasons. The notion of a ‘war’ seemed to indicate a wrong-headed belief that overt military action, rather than secret intelligence methods, was an effective response. More seriously, perhaps, this seemed to be a ‘war’ which couldn’t be won. Since it is all but inconceivable that terrorism per se can ever be eliminated by any method, the Bush-Blair crusade looked dangerously like a declaration of permanent war of an Orwellian kind.

President George W. Bush delivers remarks on the Global War on Terror during a visit Wednesday, 19 March 2008, to the Pentagon.

If by chance Bush and Blair had misread the threat posed by terrorism, they might be using a sledgehammer to crack a nut which would be not just financially wasteful but politically damaging if (as was inevitable) force was sometimes used against the wrong targets. The collateral damage of the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq showed such apprehensions to be well founded. Incredibly — from the Bush-Blair standpoint — some security experts would come to the conclusion ten years on that the military interventions had increased rather than diminished the threat of terrorism.So how was that threat read? In almost apocalyptic terms, the terrorists were said to be driven by mortal hatred of the West and to represent a deadly threat to ‘our way of life’. The first assertion was true as far as it went, the second a patent exaggeration but one which went largely unchallenged and unexamined. British journalists showed remarkably little inclination to press ministers to explain its logic. (As, for instance, when the Chancellor of the Exchequer allocated £3 billion in the 2003 budget to cover the cost of Britain’s part in the invasion of Iraq — a figure that even then was clearly a wildly optimistic estimate.) It took the passage of nearly a decade, including two fearsomely expensive, destructive, and ineffective ‘real wars’, to undermine it. And it was not a politician but a judge who first pointed out the absurdity of trying to set the threat posed to ‘our way of life’ by terrorist groups on the same level as that posed by the Wehrmacht in 1940.

At last, four years ago, the Foreign Secretary David Miliband broke ranks and accepted that the concept of the war on terror was ‘misleading and mistaken’. Worryingly late in the day, perhaps, but better late than never. The spectre of an unending war seemed to be laid to rest. Miliband specifically criticised the notion of a ‘unified transnational enemy’ that had been evoked in the global war on terror. He had grasped that al-Qaida had not lived up to its billing.

So it came as something of a surprise when David Cameron, who had seemed unconcerned to take up this element of the Blair legacy, reacted to the January attack on the Amenas gas plant in southern Algeria by pronouncing it part of a ‘global threat’. This grim event in the deepest Sahara desert was the work of an extremist Islamist terrorist group linked, like those in Pakistan and Afghanistan, to al-Qaida, whose aim, the prime minister held, was ‘to destroy our way of life’.

If his intention was to counter the risk that the public might dismiss the attack as too distant to be worth serious consideration, fair enough. But the terms he used surely went beyond what was needed for that. He went as far as to label the threat represented by the terrorists ‘existential’. This striking echo of 2001 did not go entirely unchallenged, as it had done a decade previously. This time, journalists with real experience like Jason Burke are around to point out that al-Qaida, reeling from ‘blow after blow’ over the last five years, is only a shadow of the organisation that once did perhaps represent a threat on a global scale. And that, however deadly the Amenas attack, ‘a gas refinery in southern Algeria is not the Pentagon’.

But clearly such perspectives (shared, as Burke pointed out, by the PM’s security experts) do not meet the rhetorical needs of the moment. David Miliband’s key argument was that the more we lump terrorist groups together and draw the battle lines as a simple binary struggle between moderates and extremists, ‘the more we play into the hands of those seeking to unify groups with little in common.’ What seemed by 2009 to have become no more than common sense has now been peremptorily abandoned again.

Jason Burke, maybe too charitably, described Cameron’s rhetoric as ‘dated’. That would in itself not be reassuring, but there seems to be something more going on. Though he specifically rejected the idea of a purely military solution, the prime minister’s emphasis on the ‘ungoverned spaces’ in which terrorists thrive opens up an agenda at least as indefinite as the original war on terror. His undertaking to ‘close down’ such spaces, and acceptance that this would take decades, has revived the spectre of a protracted conflict without proposing any plausible method of ending it. The function of these ‘ungoverned spaces’ is in fact highly doubtful. If such spaces exist — and the concept is highly dispuatble — they may well be useful to terrorist groups, but to suggest that they are crucial is seriously misleading. The fact that the deadliest Islamist attack in Britain was carried out by people from Leeds, Huddersfield, and Aylesbury might of course indicate that Yorkshire and Buckinghamshire are also ‘ungoverned spaces’, but the implications of that would be alarming indeed.

Charles Townshend is Professor of International History at Keele University. He has held fellowships at the National Humanities Center in North Carolina and the Woodrow Wilson International Center in Washington, DC. Amongst his previous publications are Political Violence in Ireland (1983), Making the Peace: public order and public security in modern Britain (1993), and Ireland: the twentieth century (1999). His most recent books are Easter 1916: the Irish rebellion (2005) and When God Made Hell: the British Invasion of Mesopotamia and the Creation of Iraq, 1914-1921 (2010). The second edition of Terrorism: A Very Short Introduction published in 2011.

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only VSI articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only current affairs articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: White House photo by Eric Draper [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The post Global warfare redivivus appeared first on OUPblog.

April 25, 2013

The life of a nation is told by the lives of its people…

America has a rich and diverse history which shows itself in its music, politics, film, and culture. The power of biography helps to illuminate larger questions of war, peace, and justice and in exploring the lives of the figures that helped shape America’s history we can discover more about our past.

The American National Biography Online (ANB Online) allows you to discover the lives of over 18,700 men and women who have helped to shape American history. This April, 41 new lives have been added to the resource including radical feminist Andrea Dworkin, chess genius Bobby Fischer, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and singer and actress Peggy Lee. We are also delighted to announce a new partnership between the ANB Online and the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution to allow National Portrait Gallery images to be used alongside ANB Online biographies.

Browse through the portraits and discover the famous and, not so famous, lives of some of the key figures who have been added this April.

James A. VAN ALLEN

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

James A. Van Allen, (7 Sept. 1914-9 Aug. 2006), astrophysicist. Courtesy of NASA

Robert MCNAMARA

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Robert S. McNamara, (9 June 1916-6 July 2009), business executive, president of Ford Motor Company, U.S. secretary of defense, and president of the World Bank. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of the artist.

Peggy LEE

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Peggy Lee, (26 May 1920-21 Jan. 2002), jazz and pop singer, songwriter, and actress. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Creative Commons License.

Martha GRIFFITHS

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Martha Griffiths, (29 Jan. 1912-22 Apr. 2003), U.S. congresswoman, lawyer, and women's rights advocate. Courtesy of Library of Congress (LC-U9-23069-20)

Paulette GODDARD

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Paulette Goddard, (3 June 1910-23 Apr. 1990), actress. Courtesy of Library of Congress (LC-USE6-D-001602)

John Kenneth GALBRAITH

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

John Kenneth Galbraith, (15 Oct. 1908-29 Apr. 2006), economist and author. Courtesy of the Library of Congress (LC-USE6-D-000368)

Orville FREEMAN

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Orville Freeman, (9 May 1918-20 Feb. 2003), governor and secretary of agriculture. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Mrs. Boris Chaliapin

Florence FOSTER JENKINS

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Florence Foster Jenkins, (19 May 1868-26 Nov. 1944), singer. Courtesy of Library of Congress (LC-DIG-ggbain-33928).

Lucy BURNS

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Lucy Burns, (28 July 1879-22 Dec. 1966), suffragist and vice chairman of the Congressional Union. Courtesy of the Library of Congress (LC-DIG-hec-03870)

');

');tid('spinner').style.visibility = 'visible';

var sgpro_slideshow = new TINY.sgpro_slideshow("sgpro_slideshow");

jQuery(document).ready(function($) {

// set a timeout before launching the sgpro_slideshow

window.setTimeout(function() {

sgpro_slideshow.slidearray = jsSlideshow;

sgpro_slideshow.auto = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.nolink = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.nolinkpage = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.pagelink="self";

sgpro_slideshow.speed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.imgSpeed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.navOpacity = 25;

sgpro_slideshow.navHover = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.letterbox = "#000000";

sgpro_slideshow.info = "information";

sgpro_slideshow.infoShow = "S";

sgpro_slideshow.infoSpeed = 10;

// sgpro_slideshow.transition = F;

sgpro_slideshow.left = "slideleft";

sgpro_slideshow.wrap = "slideshow-wrapper";

sgpro_slideshow.widecenter = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.right = "slideright";

sgpro_slideshow.link = "linkhover";

sgpro_slideshow.gallery = "post-40246";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbs = "";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbOpacity = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.thumbHeight = 75;

// sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.spacing = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.active = "#FFFFFF";

sgpro_slideshow.imagesbox = "thickbox";

jQuery("#spinner").remove();

sgpro_slideshow.init("sgpro_slideshow","sgpro_image","imgprev","imgnext","imglink");

}, 1000);

tid('slideshow-wrapper').style.visibility = 'visible';

});

Gemma Barratt is an Associate Marketing Manager for Oxford University Press.

The landmark American National Biography (ANB Online) offers portraits of more than 18,700 men & women — from all eras and walks of life — whose lives have shaped the nation. The wealth of biographies are supplemented with over 900 articles from The Oxford Companion to United States History and over 2,500 illustrations and photographs providing depth and context to the portraits. It is updated twice a year with new biographies, illustrations, and articles. Find out more about the latest update by visiting the Highlights page. American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) sponsors the American National Biography (ANB Online), which is published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The life of a nation is told by the lives of its people… appeared first on OUPblog.

11 facts about penguins

Happy World Penguin Day! And what better way to celebrate than by looking at photos of penguins waddling, swimming, diving, and generally looking adorable. Penguin facts are lifted from the Oxford Index’s overview page entry on penguins (on the seabird, not the 1950s R&B group).

Adelie penguins moulting. First Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911-1914. From the collections of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

There are seventeen species of this flightless seabird.

African Penguin at Artis Zoo, Amsterdam, Netherlands. Photo by Arjan Haverkamp. Creative Commons License. via Wikimedia Commons.

They belong to the family Spheniscidae, which are almost exclusive to the southern hemisphere.

Danco Island, Antarctic Peninsular. Photo by USEPA Environmental-Protection-Agency. Public domain.

Penguin wings are developed into powerful flippers for swimming.

King Penguin photographed in Asahiyama Zoo. Photo by saname777. Creative Commons License. via Wikimedia Commons.

The legs are far back in the body so on land they walk upright.

Penguin. Public domain via Pixabay.

Since they no longer fly, there are no restrictions on their weight, so their bodies are invested with blubber.

King Penguin at Edinburgh Zoo, Scotland. Photo by Dave Morris, 2005. Creative Commons License. via Wikimedia Commons.

This insulates them in the water, but means they tend to overheat on land, so the warm tropics are a barrier to their spread into the northern hemisphere.

The largest, the emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri), stands over a metre high and weighs more than 40 kilograms (98 lb).

Emperor Penguin, Atka Bay, Weddell Sea, Antarctica. Photo by Hannes Grobe/AWI, 2004. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0. via Wikimedia Commons.

Emperors have a unique life history. They breed in rookeries of up to 50,000 pairs on the Antarctic ice shelf.

A Chinstrap penguin rookery. CIA World Factbook. Public domain.

The young are left in large crèches to overwinter hundreds of kilometres from the ice edge.

Adelie penguins. Photo by Chadica (cyfer13), 2005. Creative Commons License. via Wikimedia Commons.

They can dive to depths of 265 metres (870 ft).

Antarctic. Photo by Jerzy Strzelecki. Creative Commons License. via Wikimedia Commons.

Underwater they swim at speeds of 9–11 kilometres an hour (6–7 mph).

A Gentoo Penguin swimming underwater at Edinburgh Zoo, Scotland. Photo by Debs from England, 2010. Creative Commons License. via Wikimedia Commons.

Georgia Mierswa is a marketing assistant at Oxford University Press and reports to the Global Marketing Director for online products. She began working at OUP in September 2011.

The Oxford Index is a free search and discovery tool from Oxford University Press. It is designed to help you begin your research journey by providing a single, convenient search portal for trusted scholarship from Oxford and our partners, and then point you to the most relevant related materials — from journal articles to scholarly monographs. One search brings together top quality content and unlocks connections in a way not previously possible. Take a virtual tour of the Index to learn more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post 11 facts about penguins appeared first on OUPblog.

Whose Magic Flute is it, anyway?

One of Mozart’s most enduringly popular operas, The Magic Flute has captivated audiences since its premiere in Vienna in 1791. Centered on the struggles of the heroic Prince Tamino, his beloved Pamina, and the wise Sarastro (with help and comic relief from the birdcatcher Papageno) against the Queen of the Night, we know The Magic Flute as a classic tale of the battle between good and evil, or perhaps between enlightenment and ignorance.

Mozart’s Autograph Manuscript of The Magic Flute

But it hasn’t always been that way. Depending on who we ask, and when we ask them, The Magic Flute might be a very different work. In might not involve the same characters, or it might be about a clichéd love triangle. Some of the music might be taken from other Mozart operas, or some of it might not even be by Mozart at all. We tend to assume that audiences in the past saw the “classic” operas just as we see them today, but for many years that was the exception rather than the rule. So how did we get from there to where we are now?

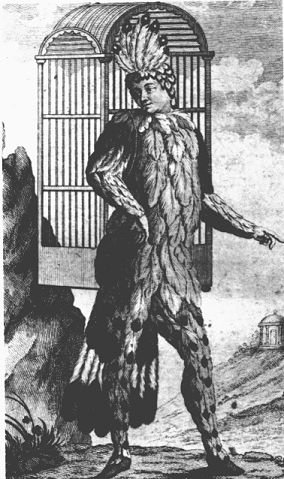

Schikanader in the role of Papageno. This image is from the front page of the original published libretto for the opera.

One way to answer that question is by following an opera in a variety of productions over time, charting the changes it makes along the way and drawing some conclusions about why those changes happen and what they might mean. In other words, by looking at productions of The Magic Flute (for example), we get new insights into the changing mindset that audiences, critics, and theater directors had about “fidelity” or “authenticity” in older music. We might fruitfully look for these types of shifts in any time and place, but I’m personally drawn to the world-renowned opera houses of nineteenth-century Paris.At that time, it was common to heavily adapt theatrical works to conform to their own dramatic standards, remaking older works into forms that audiences would easily understand and appreciate. As hard to imagine as it might be today, in an age when most theaters go out of their way to be as faithful as possible to the music and text of “classical” works, that tendency extended to Mozart’s works, including The Magic Flute. In fact, it actually wasn’t until the early 20th century, over a century after it was written, that The Magic Flute appeared in anything like its original version in Paris.

The first attempt to bring this work to Parisian audiences was in 1801, a decade after it was composed. Appreciation for Mozart’s music, and for Viennese classicism in general, was on the rise in France, and it seemed an opportune moment to begin exposing French audiences to his theatrical music. The many memorable tunes of The Magic Flute made it an ideal choice, but the plot, by Emanuel Schikaneder—who also owned the theater and played the first Papageno—was a bit more esoteric than the standard fare.

And so Les Mystères d’Isis (“The Mysteries of Isis”) was born. The original text was scrapped, although the new story did borrow a few characters and general concepts. Musically the adapters applied a lighter pen to the work; the point was bringing Mozart’s music to Paris, after all. Still, some music was cut, and some from Mozart’s other operas—still unknown in France at the time—was added in. Even odder, the work also contains some music by Haydn, another master of the Viennese classical tradition.

Title page of Les Mystères d’Isis.

Les Mystères was a modest hit, if not quite a blockbuster, and it was occasionally repeated until 1827. Over the next few decades the French mostly lost interest in The Magic Flute, preferring instead to hear adapted French (and occasionally Italian) versions of Mozart’s other operas, especially Don Giovanni, which was a Parisian favorite for most of the nineteenth century.

It wasn’t until 1865 that The Magic Flute reappeared (now called La Flûte enchantée), in a new version commissioned by the director Léon Carvalho, who was renowned as a “faithful and devoted restorer” of eighteenth-century operas, in one critic’s words. And, true enough, Mozart’s music was treated with obvious respect here—the composer was just too famous by the 1860s for any director to do otherwise. The extra music found in Les Mystères disappeared and the cuts to the score were restored.

Title page of the 1865 French version of The Magic Flute (piano/vocal score). Note that the name of the original librettist (Emanuel Schikaneder) is never mentioned, but the French translators are.

Yet the opera’s text was another matter entirely. Schikaneder’s name was nowhere to be found on the published title page (above), and the plot still had much more in common with nineteenth-century French operas than with his original text. The central drama was a love triangle between Tamino, now a humble fisherman/musician; Pamina, recast as the beautiful and chaste girl next door; and the seductive and magical Queen of the Night. (Echoes of Wagner’s opera Tannhäuser are almost certainly intentional…)

Critics and audiences were wowed by this new translation. People unfamiliar with Schikaneder’s text assumed it was “authentic,” and those in the know claimed this “translation” was much better than the original, anyway. This version appeared again in 1875 again to great acclaim, but a third production in 1893 prompted more questions than cheers.

By the 1890s, a number of critics—including many of the most famous composers of the day, like Fauré, Dukas, Saint-Saëns, and Debussy—were calling loudly for more historically informed versions of earlier operas, including Mozart’s. Eventually they found a theater director who was clever or crazy enough to follow their suggestions: Albert Carré.

A front-page picture of Edmond Clément as Tamino in the 1909 Magic Flute production, taken from the French magazine Musica.

In 1909 Carré commissioned a new and highly publicized French translation of The Magic Flute that would bring the work as close as possible to the German original. And he more or less got what he asked for, which was both good and bad for his production. While those in favor of historically informed performances were thrilled, others were much less so. Some of the latter group were genuinely fond of the older version, and others found the original plot to be either ridiculous or simply unintelligible.

But as skeptical as some critics and listeners were about the “faithful” 1909 version, they mostly realized that historically informed performances of Mozart’s operas would soon become the new standard. In just over a century, audiences approached “classic” operas in a totally different way. Before, they had adapted older operas to their tastes; now they had learned to adapt themselves to these older works.

William Gibbons is Assistant Professor of Musicology at Texas Christian University. This blog post is derived from his recent Opera Quarterly article, “(De)Translating Mozart: The Magic Flute in 1909 Paris.” His book on this general topic, Building the Operatic Museum: Eighteenth-Century Opera in Fin-de-siècle Paris, is forthcoming in June 2013.

Since its inception in 1983, The Opera Quarterly has earned the enthusiastic praise of opera lovers and scholars alike for its engagement within the field of opera studies. In 2005, David J. Levin, a dramaturg at various opera houses and critical theorist at the University of Chicago, assumed the executive editorship of The Opera Quarterly, with the goal of extending the journal’s reputation as a rigorous forum for all aspects of opera and operatic production.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: all images courtesy of William Gibbons.

The post Whose Magic Flute is it, anyway? appeared first on OUPblog.

The illusion of “choice”

Recently Planned Parenthood announced that it will no longer use the term “choice” to describe what the organization aims to preserve. It’s about time. The weak, consumerist claim of individual choice has never been sufficient to guarantee women what they need — the right to reproduce or not — and to be mothers with dignity and safety.

I was 26 when the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision legalized abortion in 1973, and like others of my generation assumed that this had settled the matter. I didn’t doubt that Roe v. Wade had established a new order that would change women’s lives forever. The backlash against the civil rights movement was in plain sight then, for example, in the fight against affirmative action, the closing down of Great Society programs, and the growing political attacks on poor mothers who received welfare benefits. Yet many women’s rights activists and others didn’t foresee the long decades of backlash against women’s new sexual and reproductive freedoms that lay ahead. Few understood at the time what would be involved to achieve reproductive freedom for women across race and class lines.

In the 1970s, the Supreme Court’s legalization of contraception for unmarried persons, along with its legalization of abortion, did seem to define “reproductive politics” as a matter of individual choices about pregnancy. It wasn’t long, however, before “choice” didn’t seem to capture what was at issue. For example, reports emerged about how some physicians routinely sterilized poor women — often women of color — without their knowledge and their “informed consent.” Manufacturers of birth control pills and IUD’s were pressured to provide full information about a range of bad side effects. Welfare laws arbitrarily excluded poor women accused of having too many children.

Debates about public funding of reproductive health services, beginning almost immediately after Roe, also revealed the insufficiency of “choice,” as have disputes about the role of religion in civic life; about what constitutes the family and its “values;” about the environment, toxicity, and population growth; and about the potential and dangers of science and technology. In short, “reproductive politics” doesn’t submit to simple mapping and extends far beyond “choice.”

This was predictable, considering how laws, policies, and court decisions have over time allowed various authorities to treat the reproductive capacities of different groups of women differently, valuing and ennobling the reproductive lives of some women while degrading others. Nineteenth-century laws governing the fertility of enslaved Africans, for example, facilitated the origins and maintenance of the slavery system. Laws and policies regulating female fertility have provided mechanisms for achieving immigration, eugenic, welfare, and adoption goals as well as supporting or hindering women’s aspirations for first-class citizenship. In the mid-twentieth century, some (white) women were constituted as good choice-makers while others (poor, women of color) were routinely regarded as bad choice-makers who produced expensive, undesirable children.

Many Americans have accepted the Supreme Court rulings fully legalizing contraception and largely legalizing abortion. Other Americans have, of course, worked against these decisions for four decades. Legislators across the country debate, enact, or reject laws regarding the status and rights of the fetus. They define whether a pregnant woman who has used a controlled substance requires criminal prosecution or medical treatment and whether the state should limit, deny, or provide assistance to poor women who become mothers.

Debates continue over whether “emergency contraception” amounts to abortion; whether the state has the right to mandate a “vaginal probe” before granting a woman her right to abortion; whether the new health insurance exchanges should include or exclude specific reproductive services; whether all babies born in the United States are US citizens; whether gay, lesbian, queer, and transgendered persons, as well as disabled people, have the same rights to parenthood, variously achieved, as heterosexual persons; and whether the relationship between rules governing “gestational carriers” (surrogate mothers) and their clients are public business or private matters. Indeed, all kinds of questions about who gets to be a legitimate mother in the United States, who does not and who decides, transcend “choice,” continue to resist resolution, and shape national politics.

Rather than constituting private matters involving individual choices, reproductive politics involves large social, economic, and political structures. In 2010 the fate of the entire federal health care reform project — passing legislation to ensure care for up to 51 million uninsured Americans — hinged on excluding abortion coverage. In 2011, state legislatures considered hundreds of bills restricting or ending long-established reproductive services and passed a number of them. Meanwhile in the United States, one out of every two women of childbearing age has experienced at least one unintended pregnancy, and low-income women are four times more likely to have this experience than middle-class women. Sexually transmitted infections, some of which can lead to infertility, have been called a “hidden epidemic” affecting all of our communities, while funding for reproductive health services is uniquely threatened.

It remains to be seen if Planned Parenthood and other organizations can convince Americans to replace the idea of individual “choice” with a new concept such as “reproductive justice,” a term that points toward what every woman needs when she decide whether or not to get pregnant, to stay pregnant, and to be a mother.

Rickie Solinger is a historian and curator. She has written and edited a number of books about reproductive politics, including Reproductive Politics: What Everyone Needs to Know, Wake Up Little Susie: Single Pregnancy and Race before Roe v. Wade and Beggars and Choosers: How the Politics of Choice Shapes Adoption, Abortion, and Welfare in the U.S. Solinger has organized exhibitions that have traveled to 140 college and university galleries over the past eighteen years. She lives in the Hudson Valley and New York City.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credits: (1) Pro-choice demonstrators. Photo by internets_dairy’s. Creative Commons Licence via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Planned Parenthood volunteers. Photo by ProgressOhio. Creative Commons Licence via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The illusion of “choice” appeared first on OUPblog.

World Malaria Day 2013

The WHO’s Sixtieth World Health Assembly proclaimed the 25th of April as World Malaria Day in recognition of the continued high mortality caused by this parasitic infection, particularly in young children. The goal of World Malaria Day is “to provide education and understanding of malaria as a global scourge that is preventable and a disease that is curable.”

Over the past few decades, increasing understanding of parasite and vector biology, as well as advancement in diagnostics and therapeutics, are providing inroads into controlling malaria infection and improving clinical outcomes. The development and implementation of diagnostic tests, for example, has been critical for providing reliable data to the treating clinician and for the evaluation of malaria control programs’ effectiveness.

An obstacle to the fight against malaria is the parasite’s capacity to develop drug resistance. Drug combinations are now used routinely, and efficacy studies around the world demonstrate excellent drug treatment outcomes with artemisinin combination therapies (ACT). Future generation antimalarials are being developed to provide additional treatment options in case artemisinin resistance emerges despite ACT.

In October 2007 a goal set by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation during the Malaria Gates Forum reignited the pursuit of malaria eradication. Efforts in the 1940 and 1950s resulted in eradication from Europe, North America, and other regions; however, minimal impact in Africa was achieved. It is for this reason that the proposal for malaria eradication was initially met with skepticism. Nevertheless, this agenda has now been embraced by public health organizations and the scientific community. Countries that have eradicated malaria or are in pre-eradication status are increasing, and there is renewed commitment to reduce the number of malaria cases globally by 75% from 2000 levels by the end of 2015.

An effective vaccine has been a long sought goal in preventing malaria. However, recent studies have shown only modest protection against infection in African children. The development of a malaria vaccine has posed a daunting challenge and may be related to the long evolutionary relationship between humans and malaria. The parasite has developed strategies to prevent the development of sterilizing immunity, as persistence in a human blood stream is crucial for continued transmission. Residents of endemic areas typically do not develop complete sterilizing immunity and thus vaccine developers need to devise ways to provide the human host with a more effective response to prevent or limit infection. Currently, there are a number of vaccines in development and the effectiveness of these additional vaccination strategies will be closely watched.

What is striking about malaria is that, while it is a “preventable and curable” infection, it continues to cause devastating global statistics and individual suffering. Targeting the vector was central for many successful eradication programs. Eliminating or limiting contact with the anopheles mosquito, the disease vector, prevents infection. Efforts to impact vector biology have been primarily through distribution of bed nets and pesticide spraying. Educating local communities to apply sustainable interventions such as habitat modifications to limit vectors (housing modifications with screens, for example) could be important adjunctive approaches and have the benefit of long term sustainability, not requiring long-term donor dependence.

Malaria is curable. Unlike HIV, which requires chronic therapy, and tuberculosis, which requires months of therapy, malaria treatment requires only a short course of medications. How can we assist malaria endemic regions to build an effective health care system to provide rapid diagnosis and timely therapy? Leaders in business such as Michael Porter and his colleagues in the Global Health Delivery Project have advocated for the rapid dissemination of management strategies for the design and management of health care delivery systems in resource poor settings. Funding both practical and known interventions along with funding of discovery of new treatments/vaccines may further improve malaria related outcomes.

World Malaria Day provides an opportunity to critically assess the state of the battle against malaria. Today should be a day to reflect on the approaches that are having a measurable impact, and those that are not. It is a day to reinforce the global and local commitments to control this preventable and curable infection.

Johanna Daily, MD is an Associate Professor of Microbiology & Immunology and of Medicine (Infectious Diseases) at Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

To raise awareness of World Malaria Day, the Editors of Clinical Infectious Diseases and The Journal of Infectious Diseases have selected recent, topical articles, which have been made freely available through the end of May. Both journals are publications of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: An African girl holding a sign with “Malaria Kills” written on it. Photo by MShep2, iStockphoto.

The post World Malaria Day 2013 appeared first on OUPblog.

What to do in winter?

If you live a long way from the equator, the amount of daylight that you have access to in summer compared to winter varies hugely. For example at 41 degrees (Launceston in Tasmania, Australia; Boston, MA, USA; and Portugal, Europe) the length of daylight varies from just over 9 hours in winter to over 15 in summer and even more dramatic at 53 degrees, with hours of daylight from 7.5 in winter to 17 in summer. It is not surprising that this will have impact on the total amount of physical activity that people perform in the different seasons with less activity in winter (14% at 41 degrees south). This is especially true for the amount of active time spent out-of-doors. The flow-on effect of limited outside activity has several health consequences to consider in winter; both reduced sun exposure for vitamin D production and changes in strength from potential deconditioning. This may also impact winter fall rates in older adults, particularly trip related falls.

Vitamin D levels within the body are important for muscle and bone health outcomes as well as adequate immune function. Recommendations for achieving adequate levels of vitamin D include maximizing safe sun exposure where possible, and opting for supplementation when not. At high latitudes in winter the availability of ultraviolet light for vitamin D production is minimal for 3 months (at 40 degrees south reducing from 36 Mega joules/m2 in summer to 8 Mega joules/m2 in winter). This closed window last even longer at higher latitudes (5 months at 53 degrees north). As well the climate at those latitudes is often not conducive to exposing skin for vitamin D gain!

We have recently identified small changes in ankle strength (reduced by 8% in winter) and dynamic balance (reduced 4% in winter) that may be related to the reduction of outside activity during the winter season. Ankle strength is one important link in the chain of physical fall risk factors for older adults. However, the control of motion around the ankle is equally or more important for maintaining postural balance and prevent falling and requires more than just strength. Postural control also relies on proprioceptive input and central balance mechanisms to maintain good ankle strategy. Walking outside in summer appears to offer challenges to balance and proprioceptive input to assist in balance reaction maintenance. Are there activities that we can recommend people do in winter to maintain ankle strength and balance, and help prevent falls?

We have recently identified small changes in ankle strength (reduced by 8% in winter) and dynamic balance (reduced 4% in winter) that may be related to the reduction of outside activity during the winter season. Ankle strength is one important link in the chain of physical fall risk factors for older adults. However, the control of motion around the ankle is equally or more important for maintaining postural balance and prevent falling and requires more than just strength. Postural control also relies on proprioceptive input and central balance mechanisms to maintain good ankle strategy. Walking outside in summer appears to offer challenges to balance and proprioceptive input to assist in balance reaction maintenance. Are there activities that we can recommend people do in winter to maintain ankle strength and balance, and help prevent falls?

It appears that typical falls in summer and falls in winter may be different. Information about inside and outside falls is available for some healthy populations. There are gender differences being found, with more men falling outside than women. The important context of frailty is being explored in Canada, with inside falls being reported to occur in populations that have more markers of physical frailty in terms of slower gait speed and step variation than outside fallers We have found a larger number of outside falls compared to inside falls in summer recently, although other researchers have found weather in winter makes outside falls in winter more common. So perhaps for those able to safely negotiate outside, the adage ‘make hay while the sun shines’ has an important corresponding saying for those who do not work the land ‘walk outside while the sun shines’. Of course there are caveats on this recommendation, with walking programs found to increase falling in people who attempt them who are too frail.

If exercising outside is too difficult because of the weather, we can deliver exercise interventions inside the home. An interesting new area of research is the use of video games to improve activity levels in older adults, and some of these are designed to challenge balance as well. Is this something that older adults may want to do in winter when the weather prevents them going outside? Current recommendations in Australia for exercise to assist in preventing falls indicates that balance activities should be done for 2 hours a week to help reduce falls. These activities should include challenges to balance that move the centre of gravity over the base of support and progressively reduce the base of support. Balance can also be challenged by altering sensory input in terms of surfaces for exercise (softer surfaces are more challenging) or changes to visual input (less visual input increases the challenge). Researchers at Monash University suggest that the level of difficulty should be such that you are challenged but not unsafe. If you use your hands to support you while exercising, it will not challenge your balance or train better balance reactions. So if you want to improve your balance — don’t use your hands.

Following these current guidelines that are based on Cochrane level evidence, it is possible to reduce the risk of falling by up to 38% through targeted exercise programs. Uptake of these appropriate exercises and adherence to fall exercise programs after starting remains disappointingly low, in light of the strong evidence. This is where technology may come into ‘play’ with exer-gaming providing new ways for participants to interact with games and each other, often from the comfort of their own home. The current commercially available sensors allow accurate and immediate feedback for ‘gamers’ and can been used for a variety of exercise goals, not only aerobic, but also to promote stepping and balance reactions. At present no interventional research currently exists to look at seasonal exercise programs to help with the winter reduction in activity (particularly outside activity) that may flow on to impact ankle strength and dynamic balance and winter fall rates. Perhaps activity based videogames may be a new recommended winter pastime for older adults to use with their friends and family.

Dr Marie-Louise Bird is a physiotherapist working at the University of Tasmania, whose area of research includes exercise interventions to improve fall risks in older adults and has recently become increasingly interested in the role of incidental activity to combat sedentary behaviours and motivation for physical activity. She is a committee member for the Australian Gerontology and Geriatrics Group (Tasmanian Branch). She is also a Pilates instructor and mentor for Polestar Pilates Australia. Marie-Louise enjoys mountain biking in Tasmania and Spain. She is the lead author of the paper, ‘Serum [25(OH)D] status, ankle strength and activity show seasonal variation in older adults: relevance for winter falls in higher latitudes’, which appears in Age and Ageing.

Age and Ageing is an international journal publishing refereed original articles and commissioned reviews on geriatric medicine and gerontology. Its range includes research on ageing and clinical, epidemiological, and psychological aspects of later life.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Feet bones anatomy with toes lateral view. By janulla, via iStockPhoto.

The post What to do in winter? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers