Oxford University Press's Blog, page 958

April 9, 2013

Reflections on Ebbets Field

At the turn of the 20th century, the baseball team in Brooklyn was known as the Superbas and they played ball at Washington Park, between First and Third streets along Third Avenue near the Gowanus Canal. While the park was convenient for its patrons, located in a densely developed part of the borough and connected to trolley lines on 3rd and 5th avenues, fans and players frequently complained about the awful odors emanating from the canal and nearby industrial works.

By the end of the aughts, Charles Ebbets, team owner and president, had grown unsatisfied with these rented grounds, even after spending significant money to upgrade and enlarge the seating area in 1907. In addition to the odors and the limited capacity of its wooden grandstand (undoubtedly a fire trap), the owner was unhappy with those who watched the games for free from the roofs of nearby tenements and the adjacent American Can Factory. At the same time, the advent of reinforced concrete was ushering in a building boom in baseball; several of Brooklyn’s rivals had already built or were in the process of erecting larger, “fireproof” ballparks.

After touring some of these newly built parks, including Shibe Park in Philadelphia and Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, Ebbets hired the architect Clarence Randall Van Buskirk to design the franchise a modern ballpark with more seats and fan comforts commensurate with these facilities. Van Buskirk worked on plans in secrecy for over a year, while Ebbets, through a dummy company began buying up properties on a large block bound by Bedford Avenue and Montgomery just east of Prospect Park. The subterfuge was intended to prevent landowners to squeeze him on the lots that would comprise the ballpark assemblage.

Ebbets Field, New York City, on opening day, 1913. Via WikiCommons

In 1913, the team moved to Ebbets Field at 55 Sullivan Place, in what is now considered the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn. Like the new ballparks of its rivals, Ebbets Field was a two-tier concrete pavilion concentrating seating around home plate, which was strategically placed near the block’s narrower southwest corner. With its gracefully arched brick window bays, pilasters, Corinthian columns and roof ornament, Ebbets Field was one of the more elegant of the ballparks constructed during this era. Its entry rotunda at the corner of Sullivan Place and Cedar Place (now McKeever Place), featured marble wall treatments, gilded ticket cages, and a marble mosaic floor inlaid with a stitched baseball pattern at its center, while a 12-arm “bat-and-ball” chandelier hung from the stuccoed ceiling above. But like its counterparts in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, Chicago and Detroit, Ebbets Field was less an architectural gem and more of a utilitarian structure that could be incrementally expanded as the team’s market grew (unlike CitiField or the new Yankee Stadium, which were designed and built in its more or less final form). Starting with an initial capacity of 18,000, additions to the stadium over the years — enlarging bleachers and extending the upper deck around the lower seating bowl — brought the park’s capacity to 34,000 by 1937 and filled out its footprint with all but its left field bleachers, covered in two decks.

When Ebbets Field was completed in 1913, its market was relatively local, with most fans traveling to the park by trolley, subway or elevated train, or on foot.

When Ebbets Field was completed in 1913, its market was relatively local, with most fans traveling to the park by trolley, subway or elevated train, or on foot. Indeed when unveiling the plans for the park, Dodger management boasted that the field was in proximity to 15 points of transit that connected to 38 different transit lines. Aside from cementing the franchise’s nickname as the “Trolley Dodgers,” or later, just Dodgers (officially becoming the teams name in 1932 after 18 years as the Robins), its location was also well connected to growth markets in southern and eastern Brooklyn, areas that were still developing during the 1910s. But by the 1950s, the park’s location had become a liability, ill-suited to the growing metropolitan scale of its fan base, who were now spreading out across Long Island and throughout the region. The stadium offered only 750 parking spaces and no nearby highway access. Even if Robert Moses had accommodated then Dodger owner Walter O’Malley’s 1955 request to move the Dodgers to the more centrally located site at the corner of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues, where the Brooklyn Nets now play basketball, Ebbets Field would have still met the same fate, demolished in the 1960 to facilitate the construction of an apartment complex.

We preserve ballparks in memory more than in actual conservation of bricks and masonry.

The demise of Ebbets Field was not terribly different than other beloved parks of its day. Beginning in the 1950s, major league teams demanded new, larger stadiums on sites accessible to suburban fan bases within their own or new cities. In 1957, when the Dodgers left Brooklyn along with the Giants who left Manhattan for San Francisco, other teams were doing the same (the Boston Braves, St. Louis Browns and Philadelphia Athletics and Washington Senators all relocated during the 1950s). During the following decade, most of the teams that did not relocate, received new, taxpayer-financed stadiums on spacious sites well connected to regional highways, much like what the Dodgers replacement, the New York Mets received when Shea Stadium was completed in Queens in 1964.

These trends resulted in the eventual demolition of all but two ballparks from the early 20th century era, Wrigley Field in Chicago and Fenway Park in Boston (the last to be taken down was Tiger Stadium in 2009 on Detroit’s Westside, a loss still mourned by many Tiger fans). Yet a generation and a half later, most of the mid-century parks have been demolished as well (Dodger Stadium in L.A. is one of the few survivors). Again threatening relocation, teams have demanded and received (mostly) downtown sites for the construction of nostalgically inspired, amenity-laden palaces mostly paid for with public money, and an ever larger share of the profits they generate. We preserve ballparks in memory more than in actual conservation of bricks and masonry.

Few current Brooklynites ever saw the Brooklyn Dodgers play, and likewise, there are only a few Dodger fans who possess memories of the team’s 1940s-50s golden era and its stellar roster of players, including future hall of famers Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese, Duke Snider, and Roy Campenella. As the Dodgers begin their 51st season at Dodger Stadium (and their 55th in L.A.), they have played there for six more seasons (and counting) than their 45-year run at Ebbets Field. While memories of the Dodgers grow more distant from the collective consciousness of Brooklyn’s 2.6 million residents, the team’s legacy is still very much with us. The design of the Met’s new home, CitiField in Queens, was inspired by Ebbets Field and includes an updated version of the park’s famed rotunda. And bringing the New Jersey Nets to Brooklyn has been justified in part as returning a major league team to the borough which lost the Dodgers.

As part of the Atlantic Yards project, city and state leaders gave the Nets a home at Flatbush and Atlantic avenues, the location denied the Dodgers, and conflated bygone allegiances, rivalries, and civic identities. Playing now in an arena named for a global bank amid a constellation of well gentrified Brooklyn neighborhoods, the Nets betray the “old school” image they attempt cultivate through their branding strategy and marketing campaigns. Tying the Nets identity specifically to Brooklyn rather than “New York” — a regional catch all that encompasses over 20 million people — captures both the nostalgia for the Dodgers and Brooklyn’s relatively recent ascension as hippest place in the universe. Time will tell if it was a wise long term strategy. Surely public money spent to lure the Nets in and subsidize Atlantic Yards could have been better spent.

Looking southwest across Bedford Avenue at Ebbets Field Apartments on a mostly sunny afternoon. Photo by Jim Henderson, public domain via WikiCommons

By contrast, the 1,300-unit housing complex, the Ebbets Field Apartments, which replaced the beloved home of the Dodgers, was a more modest and far better public investment. The immense rental complex, whose 26-story towers dwarf the more modestly scaled development east of Prospect Park, is architecturally uninspiring and a mere footnote in the history of the borough. Yet it serves a vital function, being built as part of New York State’s Mitchell Lama program, which sought to increase the supply of affordable housing for New York’s rapidly diminishing middle class of the 1960s and 1970s (the complex’s owner opted out of Mitchell Lama in 1987). Similarly, the site of the Polo Grounds, the Giants home until they left for San Francisco was rebuilt in the mid-1960s as public housing. While these developments do little to excite our collective memory or sense of community, they continue to serve as the homes of thousands of New Yorkers and perhaps will continue to do so long after the Mets, Nets, and the region’s other sports franchises again demand new facilities.

Daniel Campo is assistant professor at the School of Architecture & Planning at Morgan State University. He is the author of the forthcoming The Accidental Playground: Brooklyn Waterfront Narratives of the Undesigned and Unplanned (Fordham University Press, August 2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only US History articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Reflections on Ebbets Field appeared first on OUPblog.

Woman – or Suffragette?

In 1903, the motto “Deeds not Words” was adopted by Emmeline Pankhurst as the slogan of the new Women’s Social and Political Union. This aimed above all to secure women the vote, but it marked a deliberate departure in the methods to be used. Over fifty years of peaceful campaigning had brought no change to women’s rights in this respect; drastic action was, Emmeline decided, now called for. The “deeds” encouraged by the WSPU, such as stone-throwing, arson, window-breaking, and parliamentary deputations, would all be widely reported over the ensuing years. In the collective memory, it was however not deeds but words — and one word, suffragette, in particular — which came to epitomise this period and its aims.

The (UK) National Archives Catalogue Reference: AR 1/528

-ette and the conflicts of meaning

Suffragette neatly evokes the conflicted history of this time. If some women (and men) campaigned for the female right to vote, others campaigned against it. Even among those who supported female suffrage, there could be marked divides. First used in the Daily Mail in 1906, suffragette was not only new but a deliberate (and deliberately negative) coinage, intended to divide the suffragists, whose campaigns remained peaceful, from those who, as Pankhurst urged, should henceforth adopt more ‘militant’ methods. Suffragette, as a compound of suffrage (“The casting of a vote, voting; the exercise of a right to vote,” as the Oxford English Dictionary would confirm) plus the suffix -ette, was by no means complimentary. On one hand, -ette was a diminutive and was often seen as trivialising in intent, as well as distinctly patronizing; a lecturette (first used in 1867) was “a short lecture,” a meteorette “a small shooting star.” Both were very different from their non-diminutive counterparts.

-Ette had moreover another meaning which had become familiar in recent years. This, as in leatherette, first used in 1880 and cashmerette, used in 1886, signalled the idea of imperfect imitation, as well as inauthenticity. As a result, just as leatherette was a fake version of leather, so too, by implication, were the suffragettes ‘fake’ — and profoundly improper — versions of the suffragists. Densely polysemous, -ette was also starting to emerge as a specifically female suffix, a use which can be seen in forms such as poetette. Defined as “A young or minor poet; (sometimes esp.) a young female poet” in the Oxford English Dictionary, this already indicates the transitions at work, as the diminutive shades into the specifically female — a semantic development which was undoubtedly aided by the prominence of suffragette itself. Here too, notions of true and false, norm and other, intervene. ‘True’ women, as anti-suffrage writers regularly stressed, would never engage in militant activities of this kind. “Woman—or suffragette?” the writer Maria Corelli demanded in 1907. One could not, at least in anti-suffrage rhetoric of this kind, be both.

Lashing the wind

Trying to control meaning, as Samuel Johnson long ago affirmed in his Dictionary of 1755, is, however, rather like trying “to lash the wind.” One might feel better, but little result will be achieved. Suffragette, in fact, offers a precise illustration of Johnson’s point. Intended as a term of derision, it was nevertheless swiftly appropriated by the suffragettes themselves. Rather than a mark of stigmatization, it became a positive badge of identity — of shared aims and aspirations. A magazine was launched, named The Suffragette (copies of which were often left at sites of militant activity). In 1911, Sylvia Pankhurst published a history of the campaign so far. She called it The Suffragette: the History of the Women’s Militant Suffrage Movement, 1905-1910. Even the pronunciation could be hijacked for positive ends. Writing in the Observer in 1906, Lady Hugh Bell stressed the genuine appropriacy of the word. The dismissive -ette could, she argued, be converted into -gette, conveying not powerlessness but the “jet of enthusiasm” which united action for the vote across the land. It was also “feminine enough,” she noted — “a fine flowing word.” The Pankhursts suggested another version by which -gette was to be pronounced ‘get’ — succinctly indicating the suffragettes’ determination to ‘get the vote’ on equal terms with men.

Acts of definition

Whether dictionaries can ever capture this complexity of meaning is an interesting question. “A female supporter of the cause of women’s political enfranchisement, esp. one of a violent or ‘militant’ type,” wrote Charles Onions, defining this word in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1915. A single pronunciation appears in the accompanying transcription. One suspects that, had the Pankhursts been asked to define this word, it would have been very different. As the opening of Pankhurst’s The Suffragette extolled: “the adventurous and resourceful daring of the young suffragettes who, by climbing up on roofs, by sliding down through skylights, by hiding under platforms, constantly succeeded in asking their endless questions, has never been excelled.” “Instantly the crowd roared, “Votes for Women!”—”Three cheers for the Suffragettes!”” Emmeline Pankhurst’s 1914 My Own Story records, here describing events in 1907. Words, then as now, can mean different things to different people. Point of view can influence the act of meaning, in dictionaries as well as outside them. Were the suffragettes brave, or foolhardy? Courageous or ‘violent’? Women or suffragettes — or, of course, both?

Lynda Mugglestone is Professor of History of English at the University of Oxford and Fellow and Tutor in English at Pembroke College. She edited the newly revised and updated Oxford History of English. She is the author of Dictionaries: A Very Short Introduction and Talking Proper: The Rise of Accent as Social Symbol. She is the editor of Johnson’s Pendulum (with Freya Johnston) and Lexicography and the OED: Pioneers in the Untrodden Forest. She has contributed to The Oxford History of English Lexicography and The Oxford Handbook of the Victorian Novel.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only lexicography and language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Woman – or Suffragette? appeared first on OUPblog.

Latin America in the world today

The Hispanic world is in the news lately, and the news is mostly good. Latinos in the United States are a growing political force, and developments in Latin America are at the forefront of world affairs.

To start with, Latinos, the largest minority in the United States (approximately 57 million strong and slated to double by 2030), are acknowledged to be the deciding factor in Barack Obama’s re-election. After years of political stagnation, a record number of Hispanics cast ballots for president this year, finally assuming the political power long promised to them. It is fair to say that after the 2012 presidential election, the United States is no longer the same in large part because Latinos have taken their place as a mainstream force in American politics and society.

The issue of immigration, which made diverse factions within the Hispanic community coalesce into a united front, is at the forefront of President Obama’s domestic policies. It is likely that he will soon bring to the table the status of millions of undocumented young people who were brought here by their parents or other guardians and who have contributed to the nation’s wellbeing through steady work and study. Republicans in Washington, whose conservative views on immigration lost them credence among Latinos, are beginning to re-think their position. Even conservative talk-show host Sean Hannity has recently announced that he has “evolved” on immigration, and now supports a “pathway to citizenship” for illegal immigrants without criminal records. This is a welcome transformation. In a country with a two-party system, a weak Republican Party threatens us all by leaving us with a one-sided view.

Those who are young and undocumented and seeking legal status are called Dreamers because of the way they were defined by the failed DREAM Act. I like the appellation. America may have the largest economy in the planet. Its military strength might be feared. But the American Dream is still what the country is about, and Latinos, especially those under thirty, are committed dreamers. The face of America will be different when their status is turned around, and when immigration is addressed in a responsible way by placing the right patrolling resources on the US-Mexican border: we need a more humane border security system that stops illegal crossings, together with an efficient method of granting visas to temporary workers.

Meanwhile, the world’s attention is focused on Latin America. The Mexican economy has been growing in the past few years, in spite of the fact that narco-traffic, and the government’s war against it, has caused more than 60,000 deaths. The country’s new leader, Enrique Peña Nieto, has promised to change gears, de-emphasizing the role of the military in an effort to reduce casualties. But trust in national politicians has always run low among the population; the running joke is that the biggest calamity to befall Mexico isn’t the drug cartels but the political cartels that traffic in people’s trust. One need only look at Ciudad Juárez, the epicenter of the tragedy affecting Mexico, to see the cause of that mistrust.

Ciudad Juárez at dusk looking west toward Misión de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. Photo by Daniel Schwen, 2004. Creative Commons License.

In Brazil, economic stability has proven to be so durable that financial specialists are calling it a miracle. To a large extent, this economic miracle is the work of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a former union leader who served as the nation’s president until the end of 2010. Poverty has been dramatically reduced the middle class has grown, and Brazilian exports are reshaping the hemisphere. Ironically, it was a leader once arrested for his labor-organizing activities who turned things around.

Another benchmark in the history of commanding left-leaning governments that came to power in Latin America in the nineties was the regime of Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s caudillo, who passed away on 3 March 2013. Not since Evita Perón and Ernesto “Ché” Guevara has there been such outpouring of emotion at the death of a political leader. In spite—or perhaps because of—of all his failings, Chávez metamorphosed himself into an icon the likes of which Latin America hasn’t seen for decades. His life-long connection to Simón Bolívar, known as El Libertador, who in the early half of the nineteenth century fought to create a unified, independent South America free of foreign intervention, makes him a hero whose legacy will be debated for generations. Postcards, watches, and coffee mugs with Chávez’s effigy are already sold to tourists not only in Caracas but also in countless places from Mexico to Cuba, from Bolivia to Argentina.

Argentina, known as a factory of trendsetters in the region (think of Jorge Luis Borges), has recently offered a new type of trailblazer: a Pope. Who would have thought that the first non-European leader of the Catholic Church to be elected would be from the place known as “el sótano del mundo” (the world’s basement)? Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires, a Jesuit known now as Pope Francis (after Francis of Assisi), has already made a profound impression by making the role less pompous, more down-to-earth. He identifies with the poor, not with the ecclesiastically powerful.

And he is described as a conciliator, a quality that should come in handy as the bankrupted hierarchy of the Vatican tries to clean up its act after decades of accusations of child molestation. Pope Francis’ humility is particularly striking when one considers that Argentines have a reputation in Latin America as manufacturers of pomposity and self-aggrandizement. Maybe that’s why his first few weeks in office have been as surprising as they are refreshing in the Spanish-speaking world.

All this to say that Latin America is where things are happening. And the Latino population of the United States is as much a part of Latin America as it is of the country where Dreamers will soon be spelled without a capital D. For that reason, it seems to me that talking about North and South is no longer pertinent. Now it is just el mundo hispánico.

Ilan Stavans, Editor-in-Chief of Oxford Bibliographies in Latino Studies, is the Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. A native from Mexico, he received his Doctorate in Latin American Literature from Columbia University. He is the author of numerous books, including On Borrowed Words: A Memoir of Language (Penguin) and Spanglish: The Making of a New American Language (Harper). He is general editor of The Norton Anthology of Latino Literature. His work, adapted into stage and film, has been translated into a dozen languages. His children’s book Golemito (NewSouth) will be out in May. And Pablo Neruda: All the Odes (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux), which he edited, is scheduled for October.

Developed cooperatively with scholars and librarians worldwide, Oxford Bibliographies offers exclusive, authoritative research guides. Combining the best features of an annotated bibliography and a high-level encyclopedia, this cutting-edge resource guides researchers to the best available scholarship across a wide variety of subjects.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Latin America in the world today appeared first on OUPblog.

Lessons from Iraq 10 years on

Ten years after the capture of Baghdad on 5 April 2003 by US troops, following an invasion of Iraq by US and UK forces, we are still awaiting the outcome of the Chilcot Inquiry which was set up by the government of Gordon Brown in 2009. The report has been delayed at least until the end of 2013 due to the reluctance of the government to release key documents, but the outcome as regards the illegality of the invasion should not be in doubt.

Any student of international law, and the laws governing the use of force in particular (the jus ad bellum), knows the recognized exceptions to the prohibition on the use of force (self-defence and enforcement action taken under the authority of the UN Security Council) and that attempts by the US and the UK to fit their actions of 2003 into these exceptions were either exercises in political hubris or damage limitation by skilled lawyers. Rather than rehearse these debates, I’ll attempt to lay out a path to a clearer understanding of the Security Council as a recognized source of authority for using force (The invasion of Iraq was purportedly undertaken under the authority of that organ to enforce disarmament resolutions of that very same organ.) Given the calamitous effects of the ill-judged invasion of Iraq in 2003, where no Weapons of Mass Destruction were found, we should have expected profound changes in the work of the Security Council and the attitude of the permanent members towards collective security.

There has been some evidence of positive change. The main protagonists in favour of the use of military force against Libya in the spring of 2011, France and the UK, were clearly mindful of the lessons from Iraq, taking care that their actions were underpinned by legality by securing a clear authorising resolution (Resolution 1973) from the Security Council. This suggested a return to respect for the jus ad bellum but, as the operation against Libya unfolded, it became clear that some of the problems that undermined the legality and legitimacy of the invasion of Iraq remain.

Resolution 1973 contained an enforceable no-fly zone, a measure that had been mooted since early in the Libyan crisis, but it also allowed NATO states to go further and take military action to protect civilians, leading to an on-going debate as to whether this could include the targeting of Gaddafi and his forces even when they were not attacking or about to attack civilians.

Thus, even though there was a clear and current authorisation to use force against Libya, there were shades of the debate that occurred in 2003 in relation to Iraq concerning the interpretation of older resolutions going back to Resolution 678 of November 1990. Nevertheless, there is a vast difference between the argument made by the UK in relation to Iraq in 2003 — namely that a 1990 authorisation to use force to implement Security Council resolutions in the context of removing Iraq from Kuwait was somehow still a valid authorisation 13 years later for invading Iraq and removing Saddam Hussein — and the interpretation of a Resolution adopted in March 2011 sanctioning necessary measures in Libya, which was being implemented by states within a week of its adoption by the Security Council.

U.S. Army Soldiers from the last convoy out of Iraq line up to turn in their weapons and other equipment after completing the last mission of the nearly nine-year war in Iraq, at Camp Virginia, Kuwait, Dec. 18, 2011. (U.S. Army photo by Capt. Michael Lovas/Released)

The legal basis for the Libyan action was much stronger, but the Libyan operation didn’t eliminate fundamental problems within the UN collective security system so starkly revealed by the Iraq crisis of 2003. The system is rudimentary and depends upon political consensus between the five permanent members (P5) being present. Such consensus was achievable in March 2011 but not in March 2003. However, as with Resolution 678 (1990) in the case of Iraq, Resolution 1973 (2011) was to be the only source of authority for the use of force against Libya and, therefore, was subject to greater and greater demands placed upon it, stretching the Resolution beyond its meaning and contrary to the collective understanding of that resolution.

This process of deliberate misinterpretation by those permanent members wanting to act under the authorising resolution happened over a much longer period of time in the Iraq crisis, not only as regards the only clear authorisation for the force against Iraq in 1991 (Resolution 678), but also Resolution 1441 (2002) adopted in the build-up to the invasion of 2003, where the consensus in the Security Council was that it fell short of authorising force, particularly as it didn’t contain any authorisation of ‘necessary measures’. Let’s hope that there is no attempt by the US and others to reach back to 1950 to resurrect the authorising resolution against North Korea (Resolution 83), though recent discussion about possible breakdowns in the Korean War armistice is a worrying sign.

The change in the Security Council in 2011 that brought the P5 together sufficiently to adopt an authoring resolution appears to have been helped by the emergence in the early 21st century of the idea that there is a responsibility to protect (R2P) on the part of the international community, when a state has failed to protect its population from crimes against humanity or other similar egregious acts. The UN World Summit Outcome Document of 2005 seemed to place this responsibility on the Security Council if a state had failed to protect its own population. Although Resolution 1973 did invoke some of the language of R2P in condemning the Libyan regime, it clearly didn’t represent the development of a positive duty to act on the Security Council as the Council’s failure to act in the case of Syria shows. Crimes against humanity and systematic war crimes are being committed in Syria in a spiralling blood bath. Indeed an Independent Commission of Inquiry on Syria reported that crimes against humanity were being committed in Syria in 2011. We are now in 2013 and the situation, if anything, has got worse.

What started out in appearance at least, as an application of the emerging R2P doctrine to protect civilians in Libya based on a clear Security Council mandate, was within a few weeks heading towards another instance of illegal regime change as in Iraq in 2003, with all the problems that entailed. Unfortunately, the unwillingness of those permanent members using force in Libya (UK and France with the assistance of the US) to learn all the lessons of Iraq, by abusing the mandate given to them, has meant that those permanent members that normally advocate non-intervention (Russia and China) have a reason to block any move towards a resolution that authorises necessary measures, or indeed, remembering Iraq, any resolution that might be so construed. The temporary coming together of the permanent membership in March 2011 has proved to be the exception as the people of Syria know to their cost.

What’s the solution to such an unreliable, but central, component of the collective security order and the jus ad bellum? Reform of the Security Council? Definitely. Restrictions on the use of the veto? Certainly. For instance, if the Security Council were to be extended by the addition of new permanent members then three negative votes should be required for any decision to be blocked. But until all of that, and more, is achieved the Security Council and its permanent members must remember that when they cannot agree on military action action, they should at least agree at least on a common diplomatic and non-forcible approach to any crisis, including targeted sanctions, if they are to retain primary responsibility for peace and security.

Nigel D. White is a Professor of Public International Law at the University of Nottingham in the UK. He has written extensively on the United Nations, collective security and the international laws governing the use of force. His most recent book Democracy Goes to War: British Military Deployments under International Law was published by Oxford University Press in 2009, looks at the role international law plays in the political decision-making of the United Kingdom. He is Co-Editor of the Journal of Conflict and Security Law published by Oxford University Press.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in Public International Law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Lessons from Iraq 10 years on appeared first on OUPblog.

Musical scores and female detectives of the 1940s

The dangerous dames, fall-guy private eyes, and psychologically unstable heroes and villains who roam the streets of the 1940s crime film have often been linked with anxieties surrounding changing roles for men and women in the years around World War II. Although appearing less regularly, the evolution of the ‘working-girl’ detective character can also be connected with these shifts in gendered identity. Amateur investigators who take on a ‘case’ to get the man they love out of trouble, these women are usually white-collar office workers whose professional skills and urban familiarity prove invaluable aids to sleuthing. Their activity justified as a means of ensuring conventional romantic happiness, these leading ladies are allowed to occupy the privileged space of the detective — a role that drives the narrative forward and which, despite literary forebears such as Miss Marple, Nancy Drew and the like, remained primarily a male domain.

These agent female detectives therefore pose a challenge to the crime film’s traditional gender politics, and (like other elements of story, mood, and characterisation) music and sound play a crucial role in their construction. The classical Hollywood score consistently draws upon various cultural stereotypes to forge an expressive and easily understood set of musical signifiers of identity. From the jazz, blues, and ‘exotic’ cues associated with the femme fatale, to the strident, brass-driven sound of the hero, and the soaring strings, harps, and flutes of the ‘good wife’, film music encourages us to hear characters as Hollywood wishes. Music therefore provides a significant means through which female characters can be moved between various positions in relation to issues of crime, criminality, and romance. They may be romantic leads, femmes fatales, victims, or detectives — or take on several roles within the same film.

Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), Deadline at Dawn (1946), and The Big Steal (1949) demonstrate some of the dramatic and musical approaches to the characterisation of the working-girl detective. All three are cheaply produced ‘B’ pictures released by RKO Radio Pictures — the smallest of the major studios and a company noted for its relatively experimental approach to commercial filmmaking, as well as its crime and noir films. As the slideshow below indicates, the soundtrack of these films is used to support the activity of the female detective — giving women credibility as sleuths and highlighting the suspenseful nature of the situations they find themselves in — but music is also used to reposition these same women into the more conventional and socially acceptable roles of the love interest or the victim of crime.

Figure 1

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Whenever Mike in Stranger on the Third Floor thinks of his girlfriend Jane, we hear a romantic musical theme full of the signifiers of the 'good wife'. We see and hear Jane through Mike, helping to diminish her agency as an independent working woman.

Figure 2

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Music and voiceover narration privilege Mike's experience, working alongside striking Expressionist cinematography to depict Mike's nightmarish vision of his trial and imprisonment for a murder he didn't commit.

Figure 3

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

After Mike's real-life arrest, only Jane will believe his story about the mysterious stranger he suspects of the crime. Accompanied now by taut and suspenseful music, she tracks down and confronts her quarry.

Figure 4

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Once Mike is freed, Jane's agency as detective is short-lived. The status quo is reaffirmed: the film finishes with a reprise of the 'good wife' material as the couple head to the registry office.

Figure 5

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Deadline at Dawn opens with sailor Alex suffering amnesia. He buys time with June, a cynical and weary dancehall worker and tells her about his troubles. 'Exotic' music and styling characterise June's profession as seedy and demeaning, emphasising her lack of agency at work.

Figure 6

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

After the duo retrace Alex's steps and discover a murder victim, June immediately takes charge of the case. Sparse, angular, and chromatic 'detective music' accompanies June eavesdropping on a potential suspect, and emphasises Alex's comparative weakness.

Figure 7

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

But June is soon repositioned as Alex's love interest, when paternal taxi driver Gus gets involved. Slow and romantic descending string lines accompany the revelation of her true feelings, cementing the shift in

Figure 8

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

When Gus is revealed as the murderer and Alex's memory is restored, he is able to occupy a more conventionally masculine role. The previously feisty, independent June swaps her past lives as a cynical showgirl and cunning detective for a future role as a military wife.

Figure 9

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Filmed on location in Mexico, the soundtrack to the The Big Steal heavily features 'Latin'-style music.

Figure 10

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Joan's association with Latin sounds initially seems to cement her characterisation as the film's femme fatale.

Figure 11

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

But as the narrative develops, it becomes increasingly clear that Joan's knowledge of Mexican culture and language empowers her to act as detective, helping Halliday to clear his name and evade his pursuers.

Figure 12

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Joan's familiarity and affinity with Mexico, which result from her secretarial work for the head of an international company, mean that the film's Latin soundtrack functions to support and extend her agency.

Figure 13

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/upload...

Joan and Halliday's integration into Mexican culture is complete by the end of the story. They speculate about how big their family will be as the locals dance in the background.

');

');tid('spinner').style.visibility = 'visible';

var sgpro_slideshow = new TINY.sgpro_slideshow("sgpro_slideshow");

jQuery(document).ready(function($) {

// set a timeout before launching the sgpro_slideshow

window.setTimeout(function() {

sgpro_slideshow.slidearray = jsSlideshow;

sgpro_slideshow.auto = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.nolink = 0;

sgpro_slideshow.nolinkpage = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.pagelink="self";

sgpro_slideshow.speed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.imgSpeed = 10;

sgpro_slideshow.navOpacity = 25;

sgpro_slideshow.navHover = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.letterbox = "#000000";

sgpro_slideshow.info = "information";

sgpro_slideshow.infoShow = "S";

sgpro_slideshow.infoSpeed = 10;

// sgpro_slideshow.transition = F;

sgpro_slideshow.left = "slideleft";

sgpro_slideshow.wrap = "slideshow-wrapper";

sgpro_slideshow.widecenter = 1;

sgpro_slideshow.right = "slideright";

sgpro_slideshow.link = "linkhover";

sgpro_slideshow.gallery = "post-38478";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbs = "";

sgpro_slideshow.thumbOpacity = 70;

sgpro_slideshow.thumbHeight = 75;

// sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.scrollSpeed = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.spacing = 5;

sgpro_slideshow.active = "#FFFFFF";

sgpro_slideshow.imagesbox = "thickbox";

jQuery("#spinner").remove();

sgpro_slideshow.init("sgpro_slideshow","sgpro_image","imgprev","imgnext","imglink");

}, 1000);

tid('slideshow-wrapper').style.visibility = 'visible';

});

Despite their low budgets, these films demonstrate the complex ways in which music contributes to the classical-era crime film, making use of a range of styles and approaches to both articulate and curtail the agency of the female detective. Music interacts with storyline and structure, image construction, and other elements of the soundtrack as an interlinked and mutually dependent aspect of multimedia narrative. These soundtracks include cues ranging from generic, easily reusable ‘library’ music to expansive themes in the leitmotif tradition — but all are shaped by their interaction with other elements of narrative, and go on to shape the film in turn. What we might ordinarily think of as ‘Jane’s theme’ in Stranger on the Third Floor actually functions to reflect Mike’s possessive paternalism. The Latin rhythms that accompany Joan’s Mexican adventures in The Big Steal serve to highlight the cultural competence that helps her crack the case, rather than passing her off as a typically exoticised and expendable femme fatale.

All three films feature saccharine (and occasionally unconvincing) ‘happy endings’, where the female lead’s agency as detective is exchanged for a less threatening, more conventional positioning as an eager bride-to-be. But this typical 1940s shift in register from the criminal to the romantic cannot entirely negate the pleasurable ways in which these women challenge and extend the more usual characterisations of the classical crime film. Their role as detective may not be as clearly defined as later incarnations of the female cop, for example, but these working-girl investigators play a crucial part in unravelling mysteries, seeking justice, and keeping their men safe from harm. A crucial contributor to the gendered discourse of 1940s Hollywood, the soundtrack mediates between the positioning of women as detectives and archetypal good wives; these city sleuths not only reflect the evolution of the urban workforce, but also articulate the anxiety that surrounded it.

Catherine Haworth is a Research Fellow at the University of Huddersfield. A member of the Centre for the Study of Music, Gender and Identity, she is interested in issues of representation and identity across various media, with a particular focus upon music for film and television. You can read her Music & Letters article, ‘Detective agency? Scoring the amateur female investigator in 1940s Hollywood’ for free online for a limited time. Follow her on Twitter @CathreeneH.

Music & Letters is a leading international journal of musical scholarship, publishing articles on topics ranging from antiquity to the present day and embracing musics from classical, popular, and world traditions. Since its foundation in the 1920s, Music & Letters has especially encouraged fruitful dialogue between musicology and other disciplines. It is renowned for its long and lively reviews section, the most comprehensive and thought-provoking in any musicological journal.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Musical scores and female detectives of the 1940s appeared first on OUPblog.

April 8, 2013

The legacies of Margaret Thatcher’s rhetoric

The death of Margaret Thatcher has already prompted an outpouring of reflections upon her place in history. One aspect of her legacy that deserves attention is her use of rhetoric and the way in which, to a great degree, she helped reshape the language of British politics as well as the substance of policy. Historians divide about when original Thatcherism really was. Certainly, Thatcher’s brand of low tax, anti-union, pro-middle class politics had antecedents in the 1950s if not earlier. Yet, if her economic ideas were borrowed from others, her discursive style contained elements that were radically new.

Baroness Margaret Thatcher, 1925-2013

It was not that aggressive political language was unprecedented in Britain, of course. At the 1945 election, Thatcher’s political hero Winston Churchill alleged that if a Labour government were elected it would have to fall back on ‘some form of Gestapo’ – a taunt which itself owed something to his continued use of the rough-and-tumble style of the Edwardian era. And there were other post-war Conservatives, such as Quintin Hogg and Enoch Powell, whose rhetoric was in some ways more outrageous than Thatcher’s own. What was new about her, though, was her ability not merely to bring what she called ‘conviction politics’ into the mainstream but to make it all but hegemonic as an ideal of political conduct.

To understand this, we need to appreciate what she was reacting against. Again, historians differ about whether there really was a ‘post-war consensus’, whereby the leaders of the main parties reached broad agreement on the desirability of Keynesian economic management and a moderately generous welfare state. What is clear, though, is that by the late 1960s there were an increasing number of voices claiming that such a consensus did exist, and that it was an elite stitch-up aimed at marginalising dissent and suppressing the unarticulated common sense desires of the mass of the British people. As Conservative Party leader after 1975 Thatcher successfully posed as the radical spokeswoman of ordinary Britons against the cosy arrangements of the small-‘c’ conservative Establishment, which in her view encompassed everything from trades union leaders to the hierarchy of the Church of England.

Furthermore, it wasn’t just the content of the consensus to which she objected; that is to say, she did not just think that the politicians of the post-war years happened to have arrived at a mistaken set of policies. Rather, she believed that it was their very manner of conducting politics – the quest for agreement and the aspiration to avoid strife – that had inevitably led to bad outcomes. As Thatcher put it shortly before she entered Downing Street, ‘The Old Testament prophets didn’t go out into the highways saying, ‘Brothers, I want consensus.’ They said, ‘This is my faith and my vision! This is what I passionately believe!’ Searching for areas of agreement with one’s opponents, then, was something she found inherently suspect.

President Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at Camp David in 1986

This was not the whole story, of course. Once in office she could not do away wholly with the need for compromise, policy reversals, or downright electoral caution. However, the myth of the ‘iron lady’, which the media helped perpetuate, gave her substantial political cover for any such deviations from the true path of ideological grace. It was only when she began to completely believe the myth herself that she came unstuck, gradually dispensing with ministers who were willing to challenge her, and seemingly starting to value her own inflexibility as an inherent political virtue. Cue the disaster of the Poll Tax, battles over Europe, and her eventual exit from power.

Plainly, the effects of the Thatcher years have been long-lasting, and today’s debates about welfare and austerity are conducted very much in her shadow. Her idealisation of unyieldingness (or, if you prefer, obstinacy) as form of political conduct has been of equal importance. Tony Blair was borrowing from her playbook when he boasted that he did not have a reverse gear – a fairly significant defect, one might think, in any kind of vehicle. But perhaps her most powerful trope was her populism. Her ‘conviction’ rhetoric served as token of her alleged difference from other, more conventional politicians. This language served her very well electorally, but at the same time it served to devalue the inevitable, and arguably desirable, compromises of the ordinary political process.

Today, then, Thatcher’s economic views command considerable support across the political mainstream: the market is king. Yet the politicians who preach this post-Thatcherite consensus are themselves the object of popular hostility. They are now being attacked from the right, with UKIP gaining success by painting them as out of touch with the common people – the same trick that helped bring the Tories victory in 1979. RIP Maggie Thatcher; Long Live Nigel Farage.

Richard Toye studied at the University of Birmingham and subsequently the University of Cambridge, where he completed his Ph.D. He is currently Professor of Modern History at the University of Exeter. His books include Rhetoric: A Very Short Introduction (2013), Lloyd George and Churchill: Rivals for Greatness (2007) and Churchill’s Empire: The World That Made Him and the World He Made (2010).

The Very Short Introductions (VSI) series combines a small format with authoritative analysis and big ideas for hundreds of topic areas. Written by our expert authors, these books can change the way you think about the things that interest you and are the perfect introduction to subjects you previously knew nothing about. Grow your knowledge with OUPblog and the VSI series every Friday and like Very Short Introductions on Facebook.

Image credits: Margaret Thatcher By Williams [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; President Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at Camp David 1986. As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image is in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The legacies of Margaret Thatcher’s rhetoric appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembering Margaret Thatcher

Could it be that far from the all-powerful ‘Iron Lady’ that Margaret Thatcher was actually a little more vulnerable and isolated than many people actually understood?

By Matthew Flinders

Can it really be almost a quarter of a century since one of the most defining moments of my own personal political history? I can still remember the day as if it were yesterday. An A-level Politics seminar on the fifth floor of Swindon College; the 28 November 1990; a bright and clear day; and suddenly the door bursts open and someone screams, ‘She’s gone! It’s over! She’s gone!’ Exactly who had gone and what was over were not immediately obvious to me but in a strange way they didn’t need to be because at a deeper level what was obvious from the reactions of everybody around me was that a distinct chapter in British political history had ended. Two decades on and as a Professor of Politics I clearly have a much sharper awareness of exactly who Mrs Thatcher was and what was thought to be over (or not over as the case proved to be) in terms of a distinct approach to governing. But the announcement of her death takes me back to that seminar room and to that strange feeling that a distinct chapter in British political history has — once again — ended.

But what can I say that has not already been said about this grocer’s daughter? What can I write that will separate this obituary from the countless others that are at this moment being written (or — more accurately — rapidly retrieved from pre-prepared files)? The answer to these questions lies not in outlining the contours of Mrs Thatcher’s political career (an already well-furrowed literary terrain), but in teasing-out exactly why her approach to politics provoked such strong reactions and how she managed to cast such a long shadow over the past, present, and future of British politics. Approached in this manner at least three inter-linked issues deserve brief comment — her ideology, her style, and her vulnerability.

First and possibly foremost, Margaret Thatcher forged a new relationship between the state and the market. Having witnessed the trials and tribulations of the Heath government in the mid-1970s and then the ‘Winter of Discontent’ in the late 1970s, Mrs Thatcher was adamant that the relationship between the state and the market had to change. From reforming the state to reducing the power of the trade unions, from privatization to economic reform, and from European affairs to selling-off council houses, Mrs Thatcher undoubtedly shifted the political-economy of Britain in ways that subsequent Prime Ministers have sought to modify or amend but not significant alter. Indeed it is possible to argue that a post-Thatcherite consensus appears to exist in a thread that runs through Major, Blair, Brown, and Cameron. Whether this is viewed as a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ thing is for the moment secondary to the fact that Mrs Thatcher’s legacy has cast a shadow both far and wide. If her policies were distinctive then so too was her uncompromising political style. The ‘Iron Lady’ was a conviction politician in the sense that she believed in the capacity of her political philosophy and economic convictions to deliver positive social change. There was no middle-way; you were either with her or against her. From her ‘The lady’s not for turning’ speech to the Conservative Party in October 1980 through to her European Union rebate negotiations, Mrs Thatcher was in many ways the original ‘Ronseal politician’ — to steal a coalition phrase — in the sense that her rhetoric was generally backed-up by subsequent political reality.

There is, however, a need to dig a little deeper. An obituary should expose the essence of a person and not simply repeat their achievements (or failures). To highlight Mrs Thatcher’s ideology or style — even to dissect the various subsequent forms of Thatcherism — are hardly new additions to a congested historical canvas. The twist or barb in the tail of this obituary is therefore not a focus on Mrs Thatcher the politician but on Mrs Thatcher the person qua politics. Framed in this manner what one achieves is a quite unique perspective on a quite remarkable but possibly isolated and vulnerable woman. To describe the ‘Iron Lady’ as vulnerable might appear to some readers as an almost ridiculous statement but even the mighty Achilles had a weak heel. Indeed, if — as I will argue — Mrs Thatcher exhibited three potential vulnerabilities in her life then it is possible to use these to further underline her remarkable career and achievements.

First and foremost, Mrs Thatcher was a woman who succeeded in a man’s world. She became an MP in 1959, the first woman to lead a major British political party in 1975, and the first female Prime Minister in 1979. There is little doubt that in some ways being a women brought advantages when faced with a political party that had overwhelmingly been educated in single sex public schools and were therefore ill-prepared to deal with a powerful woman. But it also brought with it a sense of exceptionalism and difference. A second source of vulnerability stemmed from the fact that Mrs Thatcher was not ‘one of them’. Born the daughter of a grocery shop owner — indeed being brought up in the flat above the shop — she was not born into the ‘great and the good’ British political establishment. Indeed, resting between the lines of almost every political biography of Mrs Thatcher is a sense that she was always in the Conservative Party but never quite part of the Conservative Party; never quite accepted or respected by Tory grandees or elements of the political establishment. This is a critical issue as her outsider-within status arguably helps explain her style of governing and her almost clinical approach to defining friends and enemies. The final element of vulnerability has, I would argue, become clearest since her departure from frontline politics. Since leaving the House of Commons at the 1992 General Election — saying that this would allow her more freedom to speak her mind — what has been most striking is the manner in which she generally refrained from heckling from the political sidelines. Her illness may have played some role in this but I sense there was also a degree of social and political isolation; a sense that she no longer fitted in; a frustration that her ‘there is no such thing as society’ speech was always taken out of context and used against her; or a fear that no one would want to hear what she had to say. I could be wrong but deep down I can’t help but think that maybe the ‘Iron Lady’ was a little softer than many of us understood.

Margaret Thatcher

13 October 1925 – 8 April 2013

Margaret Thatcher. Photo by Marion S. Trikosko. 1975 Sept. 18.

U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection. Library of Congress.

Matthew Flinders is Professor of Parliamentary Government & Governance at the University of Sheffield. He was awarded the Political Communicator of the Year Award in 2012 and is a member of the Advisory Board for the Economic and Social Research Council’s ‘The Future of the United Kingdom and Scotland’ Programme. Jack Straw’s response to his criticisms can be found in the journal Parliamentary Affairs (Vol.63, 2010). Author of Defending Politics (2012), you can find Matthew Flinders on Twitter at PoliticalSpike and read more of Matthew Flinders’s blog posts on the OUPblog.

The post Remembering Margaret Thatcher appeared first on OUPblog.

March Madness: Atlas Edition – A champion!

Today’s the day! Either Michigan or Louisville will end March Madness with a victory, and we can all return to our normal television programming — although we hope intelligent madness continues.

Since the 11th of March, Oxford University Press has been running March Madness: Atlas Edition based on statistics drawn at random from Oxford’s Atlas of the World: 19th Edition. Mexico and Indonesia met in the finals while Madagascar and Turkey competed for third place.

To get to this point, we’ve asked:

Sweet Sixteen: 11 March Which country has the highest GDP per capita?

Round of 8: 18 March Which country has a higher level of endemism?

Final Four: 25 March Which country’s capital will be more populated by 2015?

To determine the winner, we asked: Which country has a larger industrial output (that includes mining, manufacturing, construction, and energy)?

For Third Place: Madagascar vs. Turkey WINNER: Turkey

For First Place: Mexico vs. Indonesia

OUP is pleased to announce that the winner of the 2013 March Madness: Atlas Edition is Indonesia!

First place: Indonesia

Second place: Mexico

Third place: Turkey

Indonesia’s industrial output equals $389 billion (US dollars), 10 billion ahead of Mexico. Turkey beat out Madagascar for third place with an output of $209 billion. Indonesia, with its 136,000 islands of which 6000 are inhabited, exports oil, natural gas, tin, timber, textiles, rubber, coffee and tea (to name a few). Mexico, in second place, is largely agricultural, but oil and oil products are its chief export, while manufacturing is the country’s most valuable activity. Mexico is the leading silver producer. In Turkey, agriculture employs 21% of people, and textiles, cars, machinery and paper products are the leading exports. In Madagascar, fishing, farming and forestry employ about 80% of people, but population growth has stressed the region’s forests and the unique wildlife.

Thanks for playing along, either on the courts or in your atlas! May the madness continue…

Oxford’s Atlas of the World — the only world atlas updated annually, guaranteeing that users will find the most current geographic information — is the most authoritative resource on the market. The Nineteenth Edition includes new census information, dozens of city maps, gorgeous satellite images of Earth, and a geographical glossary, once again offering exceptional value at a reasonable price.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only geography articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post March Madness: Atlas Edition – A champion! appeared first on OUPblog.

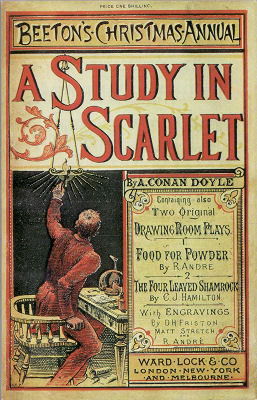

Sherlock Holmes knew chemistry

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle claimed that he wrote the Sherlock Holmes stories while waiting in his medical office for the patients who never came. When this natural teller of tales decided to write a detective story, he borrowed the concept of a cerebral detective from Edgar Allan Poe, who had “invented” the detective story in 1841 when he wrote The Murders in the Rue Morgue. So, in 1887, the brilliant Holmes debuts in A Study in Scarlet. The second Holmes story, The Sign of the Four, is a rewrite of The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841). Instead of an Orangutan scaling the unscaleable wall and killing the occupant, Doyle uses Tonga, a pygmy from the Andaman Islands to do the job. The third Holmes story, A Scandal in Bohemia, is a rewrite of Poe’s The Purloined Letter. Instead of seeking the Queen of France’s letter, Holmes must find the King of Bohemia’s incriminating photograph.

Doyle wrote a total of 60 Holmes stories and most of the time Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson share lodgings in London. Their very lives reflect the superior English education of that era. At 221b Baker Street the conversation is full of mathematical terms such as surds, conic sections, and the fifth proposition of Euclid. We hear about astronomy too: the obliquity of the ecliptic and the dynamics of asteroids. But Holmes is a chemist at heart. Before Watson even meets Holmes he is told by Young Stamford that Holmes “is a first-class chemist.” Almost every one of the tales contains a reference to some chemical. They range from elements like zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu), to industrial chemicals such as sulphuric acid and the dye Tyrian purple. Of course numerous poisons are mentioned, and several are used.

Doyle wrote a total of 60 Holmes stories and most of the time Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson share lodgings in London. Their very lives reflect the superior English education of that era. At 221b Baker Street the conversation is full of mathematical terms such as surds, conic sections, and the fifth proposition of Euclid. We hear about astronomy too: the obliquity of the ecliptic and the dynamics of asteroids. But Holmes is a chemist at heart. Before Watson even meets Holmes he is told by Young Stamford that Holmes “is a first-class chemist.” Almost every one of the tales contains a reference to some chemical. They range from elements like zinc (Zn) and copper (Cu), to industrial chemicals such as sulphuric acid and the dye Tyrian purple. Of course numerous poisons are mentioned, and several are used.

Watson, the narrator, makes Holmes’s devotion to chemistry very clear. While still a student Holmes spent his Christmas break working on experiments in organic chemistry. Holmes had a “chemical table” in their Baker Street flat. On at least one occasion the odors drove Watson to leave the premises. Another time Holmes suspended working on a case because he had “a chemical analysis of some interest to finish.” Would that Sherlock had solved more cases by chemical means, but still the chemist finds much of interest in nearly every one of the 60 tales.

Arthur Conan Doyle was also at the forefront of forensic innovation. Holmes used fingerprints (before Scotland Yard), footprints, dogs, document analysis (before the FBI started its document section), and cryptology. After Doyle’s death it was noted that,

“Poisons, handwriting, stains, dust, footprints, traces of wheels, the shape and position of wounds, the theory of cryptograms — all these and other excellent methods which germinated in Conan Doyle’s fertile imagination are now part and parcel of every detective’s scientific equipment.”

There is more science in the first half of the “Canon” and its prevalence has clearly affected the popularity of the individual tales. The Holmes stories have been ranked several times and the results consistently support the idea that those stories which contain science are preferred over those that do not. Even Conan Doyle’ own rankings agree with this. In 1927 he listed his favorite stories — 19 of them. Fifteen were from the first 30 stories and only four from the last 30. Other rankings yield the same result. In 1959 The Baker Street Journal listed the results of a poll which named the ten best and the ten worst Sherlock Holmes tales. Eight of the ten best were from the first half; while nine of the ten worst were from the last half. Sherlock Holmes was, and is, a detective that every scientist can love.

James F. O’Brien is the author of The Scientific Sherlock Holmes: Cracking the Case with Science and Forensics. Like our country he was born in Philadelphia on the Fourth of July, many years ago. He has degrees in chemistry from Villanova and Minnesota. He played college and professional basketball. He retired from Missouri State University as Distinguished Professor. A lifelong fan of Holmes, O’Brien presented his paper “What Kind of Chemist Was Sherlock Holmes” at the 1992 national American Chemical Society meeting, which resulted in an invitation to write a chapter on Holmes the chemist in the book Chemistry and Science Fiction. O’Brien has since given over 120 lectures on Holmes and science.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only science and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Cover of Beeton’s Christmas Annual for 1887, featuring A. Conan Doyle’s story A Study in Scarlet. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Sherlock Holmes knew chemistry appeared first on OUPblog.

Holocaust Remembrance Day

Holocaust Remembrance Day was originally declared a state holiday in Israel in 1951. The date, the 27th of the month of Nissan, was chosen in memory of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. In the United States, a week-long series of “Days of Remembrance of the Victims of the Holocaust” was ratified by US Congress in 1979 to coincide with Yom HaShoah, which falls sometime during April or May. This year, it is held on 8 April 2013. In Israel, the United States, and Canada (which followed suit in 2000), Yom HaShoah remembrances are built on the sacred obligation to commemorate the martyrs and victims, to honor the survivors, and to pay respects to the liberators.

In Europe, on the other hand, Holocaust memory is inevitably bound up with troubling questions about perpetration and collaboration. For every life that was taken, someone pulled the trigger, someone watched, someone profited, and someone processed the paperwork. Wherever the Holocaust is commemorated in the European community, multiple layers of individual and corporate guilt are evoked. The presence of this guilt, even in the third and fourth generation, makes Holocaust remembrance awkward. The inability to come to terms with guilt for the Jewish genocide may explain why it took the European Union until 2013 to put the “International Holocaust Remembrance Day” on its official calendar.

In Europe, on the other hand, Holocaust memory is inevitably bound up with troubling questions about perpetration and collaboration. For every life that was taken, someone pulled the trigger, someone watched, someone profited, and someone processed the paperwork. Wherever the Holocaust is commemorated in the European community, multiple layers of individual and corporate guilt are evoked. The presence of this guilt, even in the third and fourth generation, makes Holocaust remembrance awkward. The inability to come to terms with guilt for the Jewish genocide may explain why it took the European Union until 2013 to put the “International Holocaust Remembrance Day” on its official calendar.

Since 1945, European governments had developed various memorial strategies that gingerly sidestepped the problem of personal, institutional, and communal complicity and collusion in Nazi killing programs. Many constructed narratives of victimization and/or heroic resistance that were designed to alleviate moral qualms. The most infamous examples involved the governments of Austria, East Germany, and Poland, all of whom claimed victim status at the hands of (fascist) Nazi Germany. Such claims to victimization allowed individuals and institutions to deny responsibility for collaboration in the Holocaust. West Germany was the least successful in claiming the victim mantel—though not for lack of trying. Naturally, these victim narratives of oppression and powerlessness were not entirely wrong. But they obscured and falsified local histories of betrayal and persecution of Jews at the hand their Gentile Polish, Lithuanian, Ukrainian, French, Austrian neighbors. No matter how much a country or particular persons suffered at the hands of the German Nazi regime, they could still be active in the brutalization of their Jewish neighbors.

The European Union declared 27 January its day of remembrance, following the 2005 resolution by the United Nations that also designated 27 January as “International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust.” Notably, this day does not follow the Jewish calendar, but marks the day of liberation of Auschwitz by the Soviet Army in 1945.

One million people were killed in the extermination camp of Auschwitz; its name has become synonymous with the Nazi achievement of turning mass murder into an industrialized process using innovative technologies, such as gas chambers and crematories. At no other extermination site were so many people killed at the hands of so few. In Auschwitz, the inmates themselves were forced to become cogs in the machinery of death and recruited to perform the grueling labor of extermination. This death camp was explicitly designed to shield SS-personnel from the human costs of killing—although there was still unspeakable brutality committed by individuals. But the focus on Auschwitz allows European officials, once again, to sidestep local histories of collusion and complicity. In its extremity, Auschwitz allows disassociation and distancing from the human ordinariness of those who plan, administrate, and commit mass murder. Surely, the brutes in charge of that camp could not have been Ordinary Men, to quote Christopher Browning’s book, and could not have lived as ordinary businessmen, doctors, teachers, and policemen in the post-war world (which they did).

The Holocaust was not committed by an alien species of evil Nazis, who invaded, hijacked, and occupied various countries and forced their populations to stand by and watch the unfolding of genocide. On the contrary, the systematic murder of six million required the active participation of many people across Europe, who were convinced that discriminating, humiliating, disowning, ghettoizing, enslaving, deporting, and killing Jews was the proper and profitable thing to do. Unless their perspective and precise nature of culpable wrongdoing can be openly articulated, the memory of the Holocaust will continue to be affected and infected by denial and evasion. It is not possible to honor the victims without acknowledging the perpetrators. Their guilt manifests in the compulsive drive toward exculpation which seeps into and distorts national memorial strategies.

It may not be a bad thing that the world now observes two separate dates in remembrance of the Holocaust, one anchored in the Jewish calendar, the other rooted in the Western calendar of the liberation of Auschwitz. But unless we strive to connect the histories of victimization and perpetration and join in commemoration as descendants of Jewish victims and Gentile perpetrators, we will not be able to repair this rift or build a reconciled future.

Katharina von Kellenbach is Professor of Religious Studies at St. Mary’s College of Maryland and author of Anti-Judaism in Feminist Religious Writings and the forthcoming The Mark of Cain: Guilt and Denial in the Post-War Lives of Nazi Perpetrators.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: A lit Yom Hashoah candle in a dark room on Yom Hashoah. Photo by Valley2city, Wikimedia Commons.

The post Holocaust Remembrance Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers