Free will and quantum conspiracy

We all agree that heredity, previous experience, and environment influence our choices. But why do some claim that, fundamentally, free will is an illusion? The easy answer: Free will does not fit within a scientific worldview. Free will mysteriously brings about a choice, and a physical event, without a prior physical cause. A motive for denying free will is to explain away that mystery. It’s a good motive. Explaining mysteries is a motive driving the scientific endeavor.

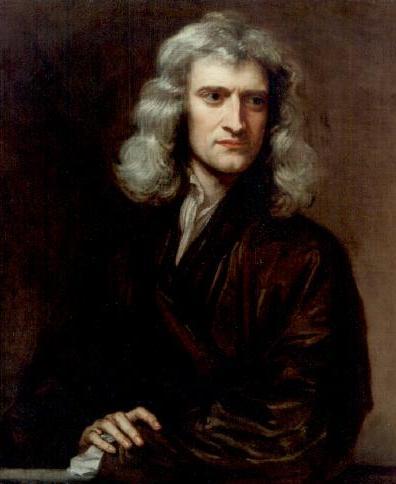

Our strict sense of cause and effect came with Newton’s physics, “classical physics.” To an “all-seeing eye” that knew the position and velocity of each atom in the universe at a given moment, the entire future of universe would be known. The idea that every event, even every thought, has a prior cause is part of our Newtonian heritage; it’s the determinism of classical physics. Most arguments denying free will are ultimately based on this determinism. Classical physics provides an extremely good approximation for the big things we ordinarily deal with, but it’s just an approximation. It fails completely for the atoms and molecules that big things are made of. Reasoning about free will should not be based on classical physics, a fundamentally flawed physics.

Our strict sense of cause and effect came with Newton’s physics, “classical physics.” To an “all-seeing eye” that knew the position and velocity of each atom in the universe at a given moment, the entire future of universe would be known. The idea that every event, even every thought, has a prior cause is part of our Newtonian heritage; it’s the determinism of classical physics. Most arguments denying free will are ultimately based on this determinism. Classical physics provides an extremely good approximation for the big things we ordinarily deal with, but it’s just an approximation. It fails completely for the atoms and molecules that big things are made of. Reasoning about free will should not be based on classical physics, a fundamentally flawed physics.

Quantum physics, or quantum mechanics, is the most battle-tested theory in all of science. No prediction of quantum mechanics has ever been wrong. It applies universally, to the big as well as the small. One-third of our economy is based on things designed with quantum mechanics. A quantum measurement problem was recognized at the inception of the theory almost a century ago. Physicists usually present it in mathematical terms, where the human issue of free will is obscure. The quantum measurement problem is sometimes, more appropriately, called the observer problem, a name emphasizing that it can be seen directly in quantum-theory-neutral observations.

The observer problem arises because you can demonstrate that a small object had either of two contradictory properties. The usual property considered (in what is sometimes called wave-particle duality) is the property of extension, how big something is. You could, for example, demonstrate that an object had been compact, concentrated in some small location, like a grain of sand. Alternatively, you could demonstrate that the object had been not compact, that it was spread out over a wide range, like a patch of fog.

Problem: Since we feel that we could have demonstrated either of two contradictory properties, what was the “actual” property of the object before we chose which of the two contradictory properties to demonstrate?

The standard quantum physics solution: Accept free will as something beyond physics. (“The free choice of the experimenter” is our preferred physics usage, not “free will.”) The experimenter’s free choice of demonstration, without any physical force on the object, creates the “actual” property the object had.

An alternate solution: Deny free will. Quantum mechanics then requires a determinism that conspires to match the experimenter’s not-free choice to the “actual” property the object had.

Bottom line: Denying free will implies a mysterious conspiratorial determinism.

Bruce Rosenblum and Fred Kuttner are the authors of Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness. Bruce Rosenblum is currently Professor of Physics, emeritus, at the University of California at Santa Cruz. He has also consulted extensively for government and industry on technical and policy issues. His research has moved from molecular physics to condensed matter physics, and, after a foray into biophysics, has focused on fundamental issues in quantum mechanics. Fred Kuttner is a Lecturer in the Department of Physics at the University of California at Santa Cruz. He devotes most of his time to teaching physics after a career in industry, including two technology startups, and a second career in academic administration. His research interests have included the low temperature propoerties o solids and the thermal properties of magnets. For the last several years he has worked on the foundations of quantum mechanics and the implications of the quantum theory.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only physics and chemistry articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image Credit: Portrait of Isaac Newton (1642-1727) by Sir Godfrey Kneller (August 8, 1646 -October 19, 1723). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Free will and quantum conspiracy appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers