Oxford University Press's Blog, page 648

July 1, 2015

George Washington and an army of liberty

To celebrate David Hackett Fischer’s Pritzker Literary Award for Lifetime Achievement in Military Writing, we’ve selected an excerpt from his Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington’s Crossing. Here, as in all of his writing, Fischer brings to life the early days of the American Revolution and the struggle Washington experienced in building a cohesive army with the thoughtful eye for detail and gripping analysis for which he’s known.

It was March 17, 1776, the mud season in New England. A Continental officer of high rank was guiding his horse through the potholed streets of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Those who knew horses noticed that he rode with the easy grace of a natural rider, and a complete mastery of himself. He sat “quiet,” as an equestrian would say, with his muscular legs extended on long leathers and toes pointed down in the stirrups, in the old-fashioned way. The animal and the man moved so fluently together that one observer was put in mind of a centaur. Another wrote that he was in- comparably “the best horseman of his age, and the most graceful figure that could be seen on horseback.”

He was a big man, immaculate in dress and of such charismatic presence that he filled the street even when he rode alone. A crowd gathered to watch him go by, as if he were a one-man parade. Children bowed and bobbed to him. Soldiers called him “Your Excellency,” a title rare in America. Gentlemen doffed their hats and spoke his name with deep respect: General Washington.

As he came closer, his features grew more distinct. In 1776, we would not have recognized him from the Stuart painting that we know too well. At the age of forty-two, he looked young, lean, and very fit—more so than we remember him. He had the sunburned, storm-beaten face of a man who lived much of his life in the open. His hair was a light hazel-brown, thinning around the temples. Beneath a high forehead, a broad Roman nose bore a few small scars of smallpox. People remembered his soft blue-gray eyes, set very wide apart and deep in their sockets. The lines around his eyes gave an unexpected hint of laughter. A Cambridge lady remarked on his “appearance of good humor.” A Hessian observed that a “slight smile in his expression when he spoke inspired affection and respect.” Many were impressed by his air of composure and surprised by his modesty.

George Washington by Charles Wilson Peale, 1776. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

George Washington by Charles Wilson Peale, 1776. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.He had been living in Cambridge for eight months and was a familiar sight in the town, but much about him seemed alien to New England. Riding at his side on most occasions in the war was his closest companion, a tall African slave in an exotic turban and long riding coat, also a superb horseman. Often his aides were with him, mostly young officers from southern Maryland and northern Virginia who shared the easy manners and bearing of Chesapeake gentlemen.

It was Sunday afternoon, March 17, 1776, and George Washington had been to church, as was his custom. At his headquarters the countersign was “Saint Patrick” in honor of the day, but nobody was bothering with countersigns, for that morning the shaky discipline of the Revolutionary army had collapsed in scenes of jubilation. American troops had at last succeeded in driving the British army from Boston, after a long siege of eleven months. The turning point had come a few days earlier when the Americans occupied Dorchester Heights overlooking the town. The British garrison organized a desperate assault to drive them away. As both sides braced for a bloody fight, a sudden storm struck Boston with such violence that the attack was called off on account of the weather. The Americans seized the advantage and greatly strengthened their position. On the night of March 16 they moved their heavy guns forward to Nook’s Hill, very close to Boston.

The next morning, March 17, British commanders in Boston awoke to the disagreeable sight of American batteries looming above them and decided that the town was untenable. While Yankee gunners held their fire, the British troops evacuated the town “with the greatest precipitation.” Altogether about nine thousand Regulars boarded transports in the harbor, along with 1,200 women and children of the army, 1,100 heartsick Tories, and thirty captive Whigs. The ships paused for a few anxious days in Nantasket Roads, while Americans worried that it might be a ruse. Then the ships stood out to sea, and the largest British army in America disappeared beyond the horizon.

When the British troops sailed away, many Americans thought that the war was over, and the hero of the hour was General Washington. Honors and congratulations poured in. Harvard College awarded him an honorary degree, “in recognition of his civic and military virtue.” In Dunstable, Massachusetts, the sixth daughter of Captain Bancroft was baptized Martha Dandridge, “the maiden name of his Excellency General Washington’s Lady.” The infant wore a gown of Continental buff and blue, with “a sprig of evergreen on its head, emblematic of his Excellency’s glory and provincial affection.”

As spring approached in 1776, Americans had many things to celebrate. Their Revolution had survived its first year with more success than anyone expected. The fighting had started at Lexington Green in a way that united most Americans in a common cause. Untrained militia, fighting bravely on their own turf, had dealt heavy blows to British Regulars and Loyalists on many American fields: at Concord and Lexington on April 19, 1775, Ticonderoga in May, Bunker Hill in June, Virginia’s Great Bridge in December, and Norfolk in January of 1776. North Carolinians had won another battle at Moore’s Creek Bridge in February, and the new Continental army had gained a major victory at Boston in March. Another stunning success would follow at South Carolina in June, when a British invasion fleet was shattered by a small palmetto fort in Charleston harbor.

In fourteen months of fighting the Americans won many victories and suffered only one major defeat, an epic disaster in Canada. By the spring of 1776, royal officials had been removed from power in every capital, and all but a few remnants of “ministerial troops” had left the thirteen colonies. Every province governed itself under congresses, conventions, committees of safety, and ancient charters. A Continental Congress in Philadelphia had assumed the functions of sovereignty. It recruited armies, issued money, made treaties with the Indians, and controlled the frontiers. European states were secretly supplying the colonies, and American privateers ranged the oceans. Commerce and industry were flourishing, despite a British attempt to shut them down.

In the spring of 1776, the goal of the American Congress was not yet independence but restoration of rights within the empire. They still called themselves the United Colonies and flew the Grand Union Flag, which combined thirteen American stripes with the British Union Jack. Many hoped that Parliament would come to its senses and allow self-government within the empire. More than a few thought that the evacuation of the British army from Boston would end a war that nobody wanted. The members of the Massachusetts General Court were thinking that way on March 28, 1776, when they thanked George Washington for his military services and wished that he might “in retirement, enjoy that Peace and Satisfaction of mind, which always attends the Good and Great.” The implication was that his military work was done.

Tories persisted in every state, but they were not thought to be a serious threat. Americans laughed about a Tory in Kinderhook, New York, who invaded a quilting frolic of young women and “began his aspersions on Congress.” He kept at it until they “stripped him naked to the waist, and instead of tar, covered him with molasses and for feathers took the downy tops of flags, which grow in the meadow and coated him well, and then let him go.” For the young women of Kinderhook, the Revolution itself had become a frolic.

In that happy mood, one might expect George Washington would have shared the general mood. Outwardly he did so, but in private letters his thoughts were deeply troubled. To his brother he confided on March 31, 1776, “No man perhaps since the first Institution of Armys ever commanded one under more difficult Circumstances than I have done. To enumerate the particulars would fill a volume—many of my difficulties and distresses were of so peculiar a cast that in order to conceal them from the enemy, I was obliged to conceal them from my friends, indeed from my own Army.”

Washington understood that every American success deepened the resolve of British leaders to break the colonial rebellion, as they had broken other rebellions in Scotland, Ireland, and England. He was sure that the Regulars would soon return, and he was very clear about their next move. As early as March 13, 1776, four days before the British left Boston, Washington advised Congress that the enemy would strike next at New York and warned that if they succeeded in “making a Lodgement,” it would not be easy to evict them.

The next day, while most of his troops were still engaged around Boston, George Washington began to shift his regiments to Manhattan. He informed Congress that when the last British troops left Boston he would “immediately repair to New York with the remainder of the army.” To save his men the exhaustion of marching on the “mirey roads” of New England, he ordered his staff to plan transport by sea.

The defense of New York was a daunting prospect. Since January, Washington and his officers had discussed the supreme difficulty of protecting an island city against a maritime enemy who commanded the waters around it. They knew the power of the Royal Navy and respected the professional skill of the British army. But Washington was more concerned about his own army than that of the enemy. The problem was not a shortage of men or munitions. Half a million free Americans were of military age. Most were ready to fight for their rights, and many were doing so. The great majority owned their own weapons, and Europeans were happy to supply whatever they lacked.

Washington’s dilemma was mainly about something else. He did not know how he could lead an amateur American army against highly skilled Regular troops. After a year in command, Washington wrote “licentiousness & every kind of disorder triumphantly reign.” The problem was compounded in his mind by the diversity of his army. He wrote, “The little discipline I have been labouring to establish in the army is in a manner done away by having such a mixture of troops.” They came from many parts of America. They joined in the common cause but understood it in very different ways. This great “mixture of troops” who were used to no control presented George Washington with a double dilemma. One part of his problem was about how to lead an army of free men. Another was about how to lead men in the common cause when they thought and acted differently from one another, and from their commander-in-chief.

Featured image: Washington Crossing the Delaware. Emanuel Leutze. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post George Washington and an army of liberty appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group Season 3: Great Expectations

‘You are to understand, Mr. Pip, that the name of the person who is your liberal benefactor remains a profound secret…’

—Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

When a mysterious benefaction takes Young Pip from the Kent marshes to London, his prospects of advancement improve greatly. Yet Pip finds he is haunted by figures from his past: the escaped convict Magwitch; the time-withered Miss Havisham and her proud and beautiful ward Estella; his abusive older sister and her kind husband Joe. In time, Pip uncovers not just the origins of his great expectations but the mystery of his own heart.

In our second season of #OWCReads, Professor Roger Luckhurst took us on a terrifying journey down the darkest streets of Victorian London as we explored Bram Stoker’s Dracula. This season, we remain in London for a very different kind of voyage. We are pleased to announce that Robert Douglas-Fairhurst will be overseeing season three of #OWCReads, which will feature his favourite Dickens novel, Great Expectations.

Perhaps the best loved of all Dickens’ novels, Great Expectations attracts readers of all ages, and has been adapted frequently for television, radio, and film. By taking part in the #OWCReads group you’ll get the opportunity to dive deeper into the intricacies of this classic text, and find out more about the life and times of Charles Dickens – as well as learning about what inspired the great man himself.

You can follow along, and join in the conversation by following us on Twitter and Facebook, and by using the hashtag #OWCreads.

Featured image: The Opening of the New London Bridge. David Cox, 1853. Public domain via WikiArt.

The post Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group Season 3: Great Expectations appeared first on OUPblog.

Hearing, but not understanding

Imagine that your hearing sensitivity for pure tones is exquisite: not affected by the kind of damage that occurs through frequent exposure to loud music or other noises. Now imagine that, despite this, you have great problems in understanding speech, even in a quiet environment. This is what occurs if you have a temporal processing disorder, potentially diagnosed as auditory neuropathy, dyslexia, specific language impairment or auditory processing disorder. Your ears works fine, yet, for some reason, your brain fails to acknowledge this.

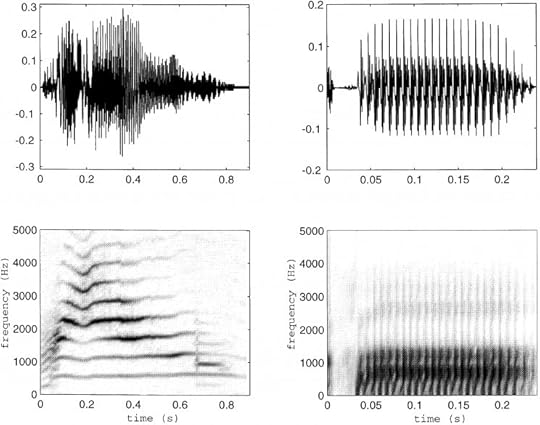

Sound is characterized by its frequency content (low-to-high tones) and its temporal dynamics (rapid fluctuations in loudness), which together determine its pitch and timbre. The temporal aspect becomes important when the sound is complex, i.e., contains many harmonics, such as a kitten vocalization (Figure), a musical note, or a spoken sentence. The scale of the dynamics varies from the periodicity in a high tone (rapid fluctuations inversely proportional to the frequency), that in a vowel reflecting the vocal cord vibration (Figure), and in the prosody of a spoken sentence. A harmonic sound, such as a musical note, can have both a periodicity pitch and a frequency pitch.

Sound is a fast and tiny fluctuation in the ambient air pressure that causes movement of the eardrum, transmitted via tiny bones in the middle ear to fluid in the inner ear, which causes a vibration mimicking the sound pressure fluctuations in the basilar membrane. Siting on top of that membrane are the hair cells that function as microphones and produce electric fluctuations that cause the release of a chemical, causing the auditory nerve fibers to fire action potentials (electric pulses) in synchrony with the sound pressure fluctuations. The auditory nerve comprises about 30,000 fibers that normally produce action potentials in mutual synchrony.

Figure. Two vocalizations illustrate similarities and differences in periodicity (top row) and harmonic structure (bottom row). In the left-hand column, a kitten meow is presented. The right-hand column illustrates the waveform of a /pa/ phoneme with a 30 ms voice-onset time. Credit: Joe Eggermont (2001).

Figure. Two vocalizations illustrate similarities and differences in periodicity (top row) and harmonic structure (bottom row). In the left-hand column, a kitten meow is presented. The right-hand column illustrates the waveform of a /pa/ phoneme with a 30 ms voice-onset time. Credit: Joe Eggermont (2001).Problems with conveying these high periodicities can occur in the interface (synapse) between hair cell and auditory nerve fiber; either through a genetic problem or by long exposure to occupational or recreational noise. This problem is called ‘auditory synaptopathy’. Problems can also occur due to dysfunction of the insulating layer around each auditory nerve fiber, also caused by gene expression problems; this is called ‘auditory neuropathy’. The phenotype of both disorders is good frequency sensitivity –near normal audiogram– but severely disrupted speech understanding. In the case of synaptopathy where the auditory nerve fibers are functioning properly, cochlear implants provide excellent rehabilitation. In the case of neuropathy, however, the successful restoration of speech perception with cochlear implants is much less. Cochlear implants consist of electrode arrays that are surgically implanted into the cochlea and receive electrical input from a sound processor, as a treatment for severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss.

Quite often dysfunctions in speech understanding occur in dyslexia, specific language impairment, and auditory processing disorders. But in these cases it is harder to pinpoint specific structural problems in the central nervous system. The underlying communality may be developmental delays in auditory temporal processing, ultimately resulting in attention overload or other cognitive problems. There is no agreement on the underlying causes here, but again processing of simple tones appears intact whereas processing of complex sounds is affected.

General neurological disorders can also involve problems with auditory temporal processing, but typically more in the longer time frames such as rhythm, intonation and prosody, and word order discrimination. So for instance, in patients with schizophrenia, autism and epilepsy, we often find abnormalities in brain rhythms and in the connections between brain structures. There are also suggestive genetic links between schizophrenia and epilepsy, between schizophrenia and dyslexia, and between autism and specific language impairment.

In these disorders the auditory system is not the only one affected, and often the integration of the auditory and other sensory modalities is affected as well. The amount of complex information in need of processing by the brain poses a dilemma, one which I recently phrased as such: “We live in a multi-sensory world and one of the challenges the brain is faced with is deciding what information belongs together. Our ability to make assumptions about the relatedness of multi-sensory stimuli is partly based on their temporal and spatial relationships. Stimuli that are proximal in time and space are likely to be bound together by the brain and ascribed to a common external event…. Audio-visual temporal processing deficits are found in dyslexia, in specific language impairment and in auditory processing disorder. In autism, the temporal integration window for audio-visual tasks is lengthened and this relates to speech processing deficits. In autism, schizophrenia, and epilepsy all temporal processing disorders were multi-modal.”

Understanding, diagnosing and rehabilitating the various auditory temporal processing disorders requires a good understanding of the basic temporal processing carried out in the inner ear and auditory nerve, as well as in the central auditory nervous system. Basic measures of temporal processing are all based on, and can largely be understood on, the basis of faithful transmission of the periodicities in sound, via the electrical pulses generated in the auditory nerve. These are the bottom-up mechanisms, but they are not sufficient for understanding the clinical problems. This requires incorporating attention and general cognitive mechanisms of communication, and integrating these top-down processes with the bottom-up ones.

Featured image: (Nature of time) 1903 by Poul la Cour by Morten Bisgaard. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Hearing, but not understanding appeared first on OUPblog.

Prince Charles, George Peele, and the theatrics of monarchical ceremony

Today marks the forty-sixth anniversary of Prince Charles’s formal investiture as Prince of Wales. At the time of this investiture, Charles himself was just shy of his twenty-first birthday, and in a video clip from that year, the young prince looks lean and fresh-faced in his suit, his elbows resting on his knees, his hands clasping and unclasping as he speaks to the importance of the investiture:

Well I feel that it is a very impressive ceremony. I know perhaps some people would think it is rather anachronistic and out of place in this world, which is perhaps somewhat cynical, but I think it can mean quite a lot if one goes about it in the right way; I think it can have some form of symbolism. For me, it’s a way of officially dedicating one’s life or part of one’s life to Wales, and the Welsh people after all wanted it, and I think also the British on the whole tend to do these sorts of ceremonies rather well, and for this reason, it’s done well, in fact, and I think it’s been very impressive, and I hope other people thought so as well.

Charles’s reflection on what the investiture means to him—a “dedication” of his life to Wales—is a striking one, made only more striking by his claim that the Welsh people “wanted it.” Does Charles speak there of the moment in 1969, imagining that the Welsh people were clamoring for a new prince of Wales (they certainly were not universally clamoring, as a recent report reminds us)? Or does he intend to reach back further into history, suggesting that the entire history of the English princedom of Wales was merely a fulfillment of Welsh desire?

Príncipe Carlos de Inglaterra (1973) by Iberia Airlines. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

Príncipe Carlos de Inglaterra (1973) by Iberia Airlines. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.If it’s the latter, then the best we can say, perhaps, is that he’s certainly not the first man to have suggested it. In the early 1590s, George Peele debuted his chronicle history play Edward I; in it, the English king must vanquish foes from both Wales and Scotland, but it’s Wales—and her prince—that gives him the most vexing difficulty. In the play’s early scenes, “Lluellen” (Peele’s spelling for Llewelyn ap Gruffydd) is a dynamic presence, a character who has commanded the loyalty of the Welsh and who has designs on dominating all of England and Wales, returning the native Britons to their ancient glory. Though Edward’s forces will eventually vanquish Lluellen and his countrymen on the field, the real battle for Wales, according to Peele, is won not by sword but by ceremony—specifically, by investiture ceremony.

The “investiture” ceremony that takes place in Peele’s play is set at Caernarfon Castle, where Charles would also find himself in 1969. And if Charles tended toward understatement in acknowledging “some form of symbolism” to the investiture, Peele fairly delighted in such symbolism. In his version of the first-ever ceremonial presentation of an English prince of Wales, Peele has the infant prince dressed in Welsh frieze, presented with Welsh cattle and corn, cheered by native Welshmen and women brought along by eager Welsh lords looking to make a deal with the English king. It is, as Peele’s stage directions indicate, a “showe,” and the play makes clear that this is ultimately what defeated the native prince of Wales—the presentation of an English prince, with a dash of Welsh flavor.

On that day 46 years ago, the monarchy also saw fit to make such symbolic gestures. There was the setting, of course, at Caernarfon, but there was also the coronet of Welsh gold, as well as the prince’s own speech in what was by all accounts very good Welsh—a speech in which he encouraged Wales “to look forward without forsaking the traditions and essential aspects of her past.” What Peele’s play and Charles’s ceremony share is a sense of the theatrical, a sense of how profoundly performance can work on the hearts and minds of spectators. Peele, of course, was writing during a time when the theatrical and the historical overlapped uniquely, when many of the most famed and popular entertainments of the day found their origins in English history, when Shakespeare himself was making a name in chronicling the exploits of English kings and princes (including, of course, that most memorable prince of Wales, Hal, whose father wrestles with another native competitor, the memorable “Glendower”). One wonders what men like Peele and Shakespeare might’ve thought about Prince Charles on the stage in Caernarfon, “dedicating” his life to Wales. It is, to be sure, a call to service that would have been unfamiliar to a culture that understood the princedom at least in part as an instrument of English dominance over its western neighbor.

Between Peele’s stage show and Charles’s formal investiture are many important—and richly suggestive—deployments of the title “prince of Wales.” Some of these live on stage, many during the sixteenth and early seventeenth century, and some live in the historical record. All of them, however, are important expressions of the acutely symbolic function of the investiture ceremony, and, perhaps more importantly, the deeply complicated and frequently obfuscated history of how the English heir to the throne came to be called the “prince of Wales.”

Image Credit: “Caernarfon Castle Panorama” by deadmanjones. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Prince Charles, George Peele, and the theatrics of monarchical ceremony appeared first on OUPblog.

The limits of regulatory cooperation

One of the most striking structural weaknesses uncovered by the euro crisis is the lack of consistent banking regulation and supervision in Europe. Although the European Banking Authority has existed since 2011, its influence is often trumped by national authorities. And many national governments within the European Union do not seem anxious to submit their financial institutions to European-wide regulation and supervision. Given this impasse, is it possible that national authorities can manage regulation and supervision via informal cooperation rather than via something more concrete like an official banking union?

History suggests that the answer is no.

It is not difficult to understand why countries—particularly countries that are as closely linked economically and financially as the Europeans—would want to cooperate in the area of financial regulation. Because of the contagious nature of banking instability, no country is truly an island. A crisis in Greece will hurt French banks; a crisis in France will hurt German banks; a crisis in Germany will affect Dutch banks. And so on. Hence, it is in everyone’s interest to make sure that their neighbors’ banks remain stable.

And, to a certain, extent, the Europeans have cooperated, both with each other and other countries. The Basel accords, for example, prescribe capital standards which have been voluntarily adopted by many countries. The European Stability Mechanism, set up to manage the resolution of failed European banks organization, was established in 2012. Still, the adoption of unified regulation and supervision has eluded the Europeans.

Even though a more stable banking system is in everyone’s interest, many European governments are reluctant to put their financial institutions on the same regulatory and supervisory footing as those of their neighbors for fear of losing their competitive edge–a phenomenon economists refer to as “regulatory competition.” The fact that Europeans are engaged in regulatory competition should come as no surprise to Americans who have experienced such competition between the federal and state banking authorities for more than 100 years.

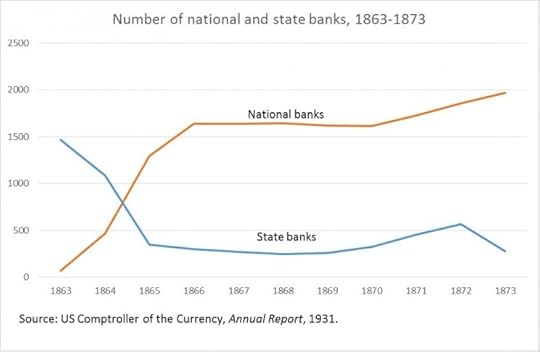

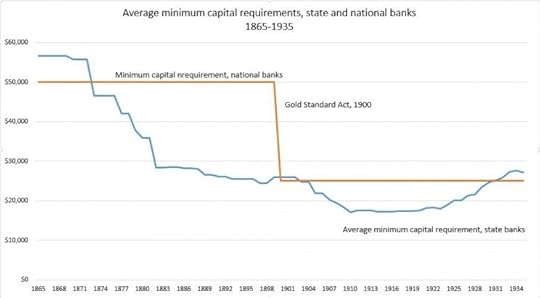

Figure 1. Image provided by Richard S. Grossman.

Figure 1. Image provided by Richard S. Grossman.From 1789 until 1863, the US government stayed largely out of banking, leaving the business of chartering (i.e., creating) banks to the state governments. This was a good deal for the states, since they made money by imposing taxes and fees upon banks, as well as forcing them to buy—and hold–bonds issued by the state. It was a good deal for the state banks too, since they were allowed to print money–which they could lend out at interest—as long as they had enough gold or silver to buy back any of their outstanding notes when asked.

In order to raise funds to fight the Civil War, the federal government created a new type of bank, the “national bank.” These were to be created and supervised by the federal government, pay fees to the government, and be required to buy and hold US Treasury securities as a condition of doing business. Like state banks, they were also allowed to issue banknotes. This was the birth of the “dual banking system.”

Because the federal government wanted national banks to thrive, they provided them with an advantage over their state-chartered rivals by placing a tax upon state bank-note issues, effectively driving them out of existence. This was the first shot in the regulatory competition between state and federal regulators, and contributed to a surge in the number of national banks and a decline in their state-chartered counterparts (see Figure 1).

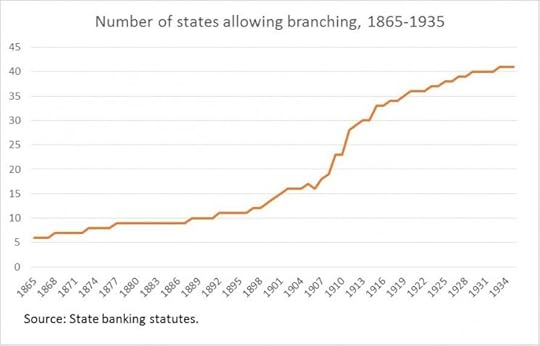

Figure 2. Image provided by Richard S. Grossman.

Figure 2. Image provided by Richard S. Grossman.The states did not take this lying down, and made it easier for state banks to establish branches, something national banks did not do, thus giving a competitive advantage to state banks (Figure 2). Additionally, they began to reduce the minimum capital requirement—the amount of funds that banks need–to get a state charter. This led to a fall in the average state minimum capital requirement (Figure 3). The federal government’s counterpunch came in 1900, when they lowered the minimum capital requirement for national banks.

Lest you think that this legacy of federal-state regulatory competition is a thing of the past, consider the opening lines of a recent publication by the Texas state banking department aimed at potential bankers:

“Why Choose a Texas State Bank Charter? Just as market competition provides customers a choice among banks, the nature of the dual-banking system allows bankers a choice between regulators.”

Figure 3. Image provided by Richard S. Grossman.

Figure 3. Image provided by Richard S. Grossman.Regulatory competition remains alive and well today in the United States, but it is significantly tempered by the fact that almost all state-chartered banks are subject to oversight by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Federal Reserve.

In Europe, the supervisory and regulatory differences across countries are much greater and there is no equivalent to the US’s federal system of oversight. Unless the EU can establish a full banking union, regulatory competition will remain a threat to Europe’s banking system.

This post is based on a presentation made by Richard S. Grossman at the Law Institute of the University of Zurich on June 1, 2015.

Featured image credit: Euro bank notes, by martaposemuckel. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The limits of regulatory cooperation appeared first on OUPblog.

June 28, 2015

When politicians talk science

With more candidates entering the 2016 presidential race weekly, how do we decide which one deserves our vote? Is a good sense of humor important? Should he or she be someone we can imagine drinking beer with? Does he or she share our position on an issue that trumps all others in our minds? We use myriad criteria to make voting decisions, but one of the most important for me is whether the candidate carefully considers all the evidence bearing on the positions he or she advocates.

Recent unprecedented temperatures in India and flooding in Texas remind us that global climate change is an issue that will be more important than ever in the next presidential election. Climate change is also an issue that inspires pronouncements by politicians–sometimes thoughtful but often foolish. What kind of evidence do politicians have in mind when they make these pronouncements?

Jeb Bush was campaigning in New Hampshire on 20 May 2015 when a voter asked about his position on climate change. According to Reuters, he said, “Look, first of all, the climate is changing. I don’t think the science is clear what percentage is man-made and what percentage is natural. It’s convoluted. And for the people to say the science is decided on, this is just really arrogant, to be honest with you.” Is it, in fact, arrogant to say “the science is decided?” What does it mean for the science to be decided, and what is the evidence about this?

Is it, in fact, arrogant to say ‘the science is decided?’ What does it mean for the science to be decided, and what is the evidence about this?

Bush was talking about the scientific consensus that many aspects of climate are changing due in large part to human activities that add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. The most thorough evidence for this consensus was reported by John Cook and eight colleagues in Environmental Research Letters in 2013. Cook’s group analyzed almost 12,000 peer-reviewed books and papers in the scientific literature and reported that 97% of those that took an explicit position agreed with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, concluding that humans cause global warming.

“The science is decided,” in Bush’s terms, doesn’t mean that scientists understand everything about climate change or that they are unanimous about the causes and consequences of climate change. On the contrary, global climate change is a very active area of research with new discoveries reported every month. “The science is decided” does mean that the basic causes of climate change are well understood and the contributions of fossil fuel use to climate change in the past 100 years are well documented. Likewise, a consensus of 97% doesn’t mean that the remaining 3% includes some brilliantly creative scientists poised to revolutionize climate science. Most of us know that the Earth is round, but members of the Flat Earth societies that still exist in the twenty-first century aren’t going to change that fact.

How can those of us who aren’t climatologists evaluate this consensus among climate researchers that humans cause global warming? Let me suggest an analogy. Suppose you visit your doctor for an annual checkup, and she says that your blood test shows more white blood cells than normal, suggesting a bone marrow biopsy to test for leukemia. Unfortunately, the biopsy is positive and she refers you to an oncologist, who suggests a bone marrow transplant with a modest chance of success. You decide to get a second opinion. This oncologist agrees with the first, so you seek a third opinion. This oncologist also agrees, so you travel to a different part of the country for a fourth opinion. This continues until you’ve seen 50 oncologists, all of whom agree with the diagnosis and treatment. Now you decide that you should try some doctors in different countries. Since you have unlimited financial resources, you decide that you’ll get 100 opinions from around the world before deciding what to do. After several months, you’ve seen 97 oncologists who agree with the original one that you have leukemia and that a bone marrow transplant is indicated, but three who think that everything is fine and you don’t need any treatment. What would you decide? There’s a strong consensus that you have leukemia and need a transplant; if you reject the evidence of this consensus, it suggests that you have very strong motives to refuse the treatment in spite of the consensus. Similarly, people may reject the scientific consensus about global climate change because they have strong incentives to reject the “treatment”–controlling emissions of greenhouse gases.

“The science is decided” is shorthand for the overwhelming scientific consensus about the basic facts of climate change. Bush called it “really arrogant” to say the science is decided. Commentators such as Timothy Egan of the New York Times thought Bush was referring to scientists here, but it seems more likely in this case that he was referring to President Obama, who told Coast Guard Academy graduates on the same day that “the science is indisputable.” Perhaps Obama should have been more precise and said “the basic science of climate change is indisputable.”

Another candidate for president, Ted Cruz, demonstrated real arrogance in March 2015 when he compared himself to Galileo. “It used to be [that] it is accepted scientific wisdom the Earth is flat, and this heretic named Galileo was branded a denier,” he commented. In fact, Galileo was branded a heretic by the Catholic Church in 1633 because he relied on the scientific method to test his beliefs rather than simply accepting traditional beliefs on faith. It’s ironic that Cruz and other ostensibly religious politicians who deny the evidence for climate change align themselves with the seventeenth century Church of Pope Urban rather than the twenty-first century Church of Pope Francis.

Image Credit: “Power plant pollution” by Hans. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post When politicians talk science appeared first on OUPblog.

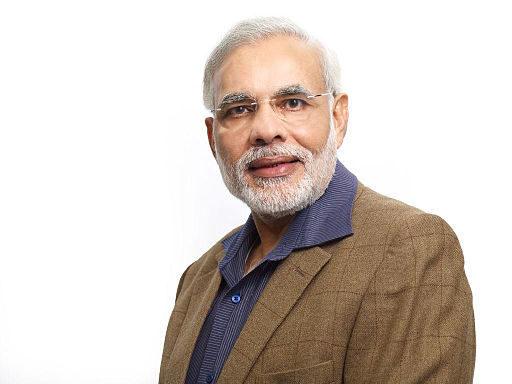

India’s foreign policy at a cusp?

Is India’s foreign policy at a cusp? The question is far from trivial. Since assuming office, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has visited well over a dozen countries ranging from India’s immediate neighborhood to places as far as Brazil. Despite this very active foreign policy agenda, not once has he or anyone in his Cabinet ever invoked the term “nonalignment”. Nor, for that matter, has he once referred to India’s quest for “strategic autonomy” — a term of talismanic significance to the United Progressive Alliance government.

Modi’s studious avoidance of these terms, along with a series of choices during his first year in office, may well bespeak new era in India’s foreign policy. Apart from his avoidance of such fraught language Modi has taken decisions that suggest a clear break with the past. For example, without much fanfare he invited President Barack Obama as the chief guest at India’s annual Republic Day Parade. Long after the Cold War’s no, no other prime minister had even considered such a gesture. Given the many past vicissitudes in Indo-US relations, his invitation to Obama was laden with meaning: India was now ready to move toward a more cordial working relationship with the United States.

His ability to take touch decisions was also on display during his visit to France. Thanks to the vagaries of India’s complex defense procurement process, the purchase of 126 Rafale medium multi-role combat aircraft has long been in abeyance. While in France, cognizant of the acute needs of the Indian Air Force, Modi chose to purchase 36 aircraft in a “fly away” condition. Admittedly, this abrupt decision is not without its critics. Nevertheless, it did demonstrate a clear-cut willingness on his part to make a demanding decision affecting India’s vital security needs.

Closer to home he has also demonstrated a remarkable degree of verve and imagination in the conduct of the country’s foreign policy. Past regimes had ineffectually protested the Pakistan High Commissioner’s feckless dalliance with various Kashmiri separatists on the eve of many Indo-Pakistani bilateral talks. However, in August 2014, when High Commissioner Abdul Basit chose to do yet again, despite a clear warning from the Ministry of External Affairs, the Prime Minister’s office simply called off the Foreign Secretary level talks.

“Narendra Damodardas Modi” by Narendra Modi. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Narendra Damodardas Modi” by Narendra Modi. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Similarly, even though intent on courting better economic ties with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and attracting investment from that country, Modi apparently did not mince his words in his conversations with Xi Jinping during his trip to the PRC in May 2015. According to multiple press reports he candidly informed his Chinese host about India’s concerns about the long-standing border dispute.

Not only has Modi displayed gumption in dealing with India’s two most nettlesome neighbors, but he has also displayed a degree of magnanimity in his handling of smaller neighbors. A number of past governments had failed to tackle the trying issues of enclaves along the Indo-Bangladesh border. Once again, Modi moved with dispatch to settle the issue even though it required a constitutional amendment. It remains to be seen if he can demonstrate similar skill in resolving the issues surrounding the Teesta river waters.

The vast majority of these choices and decisions show a willingness on his part to embark on a more bold and inventive foreign policy. That said, there are at least two potential pitfalls that could dog his footsteps. First, his foreign policy seems to be mostly a function of his own ideas and initiatives. It is far from clear the extent to which he has been able to persuade India’s substantial bureaucratic apparatus to get on board with his novel moves. Unless he succeeds in convincing the stolid foreign policy apparatus of the wisdom and necessity of his actions he may well face considerable foot dragging in the future. Second, at a more substantive level, apart from a stated interest in visiting Israel, he has evinced scant interest in other parts of the Middle East. Given India’s current and foreseeable dependence on petroleum from the region, the remittances of its guest workers and the danger of the spread of radical Islam, his inattention to this critical region is disturbing. It can only be hoped that in due course he will turn his gaze toward this vital area.

Barring serious missteps and some focus on persuading India’s foreign policy establishment of the virtues of his policies, Modi may well be able to bring about much-needed shifts in India’s foreign policy orientation.

Featured Image: “President Barack Obama speaks with Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the 2015 Republic Day Parade”, by Pete Souza. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post India’s foreign policy at a cusp? appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know Ludwig Wittgenstein? [quiz]

This June, we’re featuring Ludwig Wittgenstein as our philosopher of the month. Born into a wealthy industrial family in Austria, Wittgenstein is regarded by many as the greatest philosopher of the 20th century for his work around the philosophy of language and logic. Take our quiz to see how well you know the life and studies of Wittgenstein.

You can learn more about Wittgenstein by following #philosopherotm @OUPPhilosophy

Feature Image: Austria by barnyz. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How well do you know Ludwig Wittgenstein? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

June 27, 2015

Twerking since 1820: an OED antedating

When the word twerk burst into the global vocabulary of English a few years ago with reference to a dance involving thrusting movements of the bottom and hips, most accounts of its origin pointed in the same direction, to the New Orleans ‘bounce’ music scene of the 1990s, and in particular to a 1993 recording by DJ Jubilee, ‘Jubilee All,’ whose refrain exhorted dancers to ‘twerk, baby, twerk.’ However, information in a new entry published in the historical Oxford English Dictionary this month, as part of the June 2015 update, reveals that the word was in fact present in English more than 170 years earlier.

The OED’s new entry gives 1820 as the first date for the word twerk, then used as a noun meaning ‘a twisting or jerking movement; a twitch’ and originally spelled twirk. This is the first example of the noun found by the OED’s researchers, from a letter to the author of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley:

Really the Germans do allow themselves such twists & twirks of the pen, that it would puzzle any one.

(1820, Charles Clairmont, Letter, 26 Feb.)

The noun eventually developed other senses, referring to ‘an ineffectual or worthless person; a fool, a “jerk”’ by 1928; to ‘a (minor) change or variation, esp. of an odd or negative type; a twist’ by 1940; and, by the late 1990s, to the notorious dance.

Twerk was being used as a verb by 1848, meaning ‘to move (something) with a twitching, twisting, or jerking motion’. Early examples show people twerking their spurs, thumbs, and hats, and (in intransitive use) to a kitten’s tail twerking. The meaning referring to the dance continues to be attested first in the 1993 song by DJ Jubilee, but the OED’s editors believe that these meanings are ultimately connected and represent the same word, deriving most likely from a blend of twist or twitch and jerk, although the verbal use relating to the dance is probably influenced by similar uses of the verb work.

Twirk or twerk?

In spite of the fact that the twirk spelling is earlier, the OED has made the twerk spelling the headword form. This is because while it is a later development, it is the most common spelling overall, particularly in recent use. Usage referring to the dance is most often spelled with an e, but there are some exceptions, for instance in this example from 1999:

Teens at the Waggaman Playground gym gathered around the dance floor to ‘twirk’. For my adult readers, I’ll translate for you. Twirk is the latest dance move.

(1999, Times-Picayune (New Orleans) (Westwego ed.) 11 Mar., p. 3f 4/1)

The variety of spellings used in all meanings made OED editors confident that the various twirks and twerks were properly considered as the same word, and this new perspective presents a very different narrative of the word’s history. Instead of being a spontaneous coinage in 1990s New Orleans, twerk is seen as an old word which filled a number of roles in English from the nineteenth century through the twentieth and into the twenty-first, but did not become widely current in our vocabulary until the very recent ubiquity of a particular rump-shaking dance move.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Engraving by George Stodart after a monument of Mary and Percy Shelley” by Henry Weekes (1853). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Twerking since 1820: an OED antedating appeared first on OUPblog.

Real change in food systems needs real ethics

In May, we celebrated the third annual workshop on food justice at Michigan State University. Few of the people who come to these student-organized events doubt that they are part of a social movement. And yet it is not clear to me that the “social movement” framing is the best way to understand food justice, or indeed many of the issues in the food system that have been raised by Mark Bittman or journalists such as Eric Schlosser, Michael Pollan, or Barry Estabrook.

Social movements attain what clarity of purpose they have because they have a morally compelling cause. The labor movement, the women’s movement, and the civil rights movement had factions and divisions over strategy, tactics, or the value of subsidiary goals. But each was united by faith in the underlying justice of a unifying cause, however vaguely stated. There are a lot of things wrong with our contemporary food system, but that is about the only thing on which people enrolled in today’s food movement agree.

I would submit that the whole idea of a food movement came out of academia. First dozens and later hundreds of sociologists, anthropologists, and geographers have studied discontent and protest over food issues under aegis of social movement theory since the 1960s. Their work on the food system originated as studies on bona fide social movements: the labor movement (Caesar Chavez), the women’s movement (globally, most farmers are women), and the civil rights movement (slavery, sharecropping and the racialization of migrant agricultural labor). By 2000, an idealistic crop of young activists had taken their courses. They mobilized the social movement idea to organize urban gardens, fair trade, and new efforts to improve the standard of living for farm and food system workers. Ethical vegetarians, opponents of genetic engineering and advocates for slow food, raw milk and organic farming were more than happy to join the mix.

I have been advocating an alternative idea since the early 1980s. “Food ethics” is less sure that we have the answers than the food movement, but it shares many of the same concerns with our existing food system. Food ethics would be the cultivation and dissemination of a more reflective, more open-minded and more compassionate consideration of the way that food is produced, processed, distributed, and consumed at both local and global scales. It sees many of our current problems as a failure to think broadly and deeply enough about food and agriculture. It hopes to mobilize the resources of philosophical ethics—a rich moral vocabulary and a willingness to engage in serious debate—both as social critique but also within the corridors where key decisions about food system policy and practice are currently made.

“Wheat”, by Hans. Public domain via Pixabay.

“Wheat”, by Hans. Public domain via Pixabay.Food ethics is not opposed to a food movement. Indeed, the consciousness raising work of journalists like Bittman or of activists such as Raj Patel or Frances Moore Lappé provides crucial material for ethical reflection. What is more, I have come to see a focus on food as an important corrective to narrowness, over-abstraction and reductionism in philosophy itself. When food activists talk about “getting it right” they mean something more important than a philosophically adequate characterization of the sources of normativity. They mean to do something. Academic philosophy could use some of that fire.

For these reasons, I wish Bittman success with his new book A Bone to Pick. Yet while he questions whether the food movement is tough enough to deserve that name, my concern is complexity in food issues that warrants more careful inquiry. Our food practices need the kind of debate that philosophers have always excelled at—a debate where arguments are crafted, then considered carefully and where people sometimes change their mind. Getting serious about food ethics will take more than ethical theory, to be sure. It will require the marriage of a philosophical mindset with careful study of how our food system actually operates.

For example, Bittman’s column calls for an end to “routine use of antibiotics in food production. “ He is on to something. For decades, meat producers have been feeding their animals on grains containing a subtherapeutic amount of antibiotics. They do it because the animals grow faster, or to put it in food industry talk, they make more efficient use of their feed ration. After more than a decade of debate over this practice and its impact on the increase in antibiotic-resistant strains of pathogens, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a request for voluntary discontinuance of the practice last December. There has been much discussion as to why a stronger regulatory action was not taken, but one piece of this controversy is reflected in Bittman’s own language.

What does “routine use” mean? Using antibiotics looks different depending on what kind of food animal you are talking about, and the reasons why they’re being used. Producers of pork and beef use antibiotics to treat sick animals. Taking that kind of routine use off the table would violate standards of humane animal husbandry. In addition, a flock or herd will be given a preventative dose (large enough to have therapeutic effect) when there are reasons to suspect that animals have been exposed to disease-producing microorganisms. Such prophylactic dosing poses an especially tricky ethical conundrum. Producers wouldn’t be doing it if they didn’t think it worth the expense, but should they be weighing the benefits to animal health against the risk of resistant bacteria?

“Routine use” also conceals important elements of agency. As long as feedgrains with antibiotics are widely available, farmers are going to feel compelled to buy them. They put themselves at too much of a competitive disadvantage if they don’t. Although it’s encouraging that the drug industry is at least taking steps to remove growth-promotion from their list of approved uses for these drugs, commentators should be making it clearer that the ball is not in farmers’ court, in the first place. The eventual success of FDA’s voluntary effort will depend on the action of millers and pharmaceutical makers, as well as processors and retailers who will specify the advance contracts for animal products.

In a world where we leave such details of the antibiotics question at the level of “routine use”, livestock producers will suspect that they are being primed as targets for skewering. They will not be especially clear in their protest either, preferring to complain about government interference without explaining the details. With more clarity about how food production actually works, we’ll be able to address issues with the kind of focus that true seriousness demands. Maybe we will even make some strides in social change. Making food issues real will require a level of rigor in thought and speech that we have yet to see from the food movement. Maybe ethics can help.

Feature Image: “Plant-Crop-Grain”, by Unsplash. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Real change in food systems needs real ethics appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers