Oxford University Press's Blog, page 650

June 24, 2015

The history of the word ‘bad’

Our earliest etymologists did not realize how much trouble the adjective bad would give later researchers. The first of them—John Minsheu (1617) and Stephen Skinner (1671)—cited Dutch quaad “bad, evil; ill.” (Before going on, I should note that today quad is spelled kwaad, which shows that a civilized nation using the Roman alphabet can do very well without the letter q.) This was not a bad guess. Kwaad has congeners elsewhere in West Germanic and, quite probably, outside Germanic, though Old English had the puzzling form cwead, with a long diphthong. The sound w was sometimes lost in this word, as one can see in Modern German Kot “excrement,” whose older form was close to the Dutch word. Quaad arose as a noun and became an adjective for the reasons that have not been explained with sufficient clarity. Be that as it may, no path leads from Germanic kw- to Old Engl. b-, but such niceties did not bother anyone until the days when historical linguists realized that words should be compared according to certain rules (or laws). Researchers resigned themselves to the tyranny of those laws, but as a reward etymology stopped being guesswork or at least stopped being entirely such. Although difficulties remained (consider the mystery of Old Engl. cwead), nowadays they are not swept under the rug; if something is unclear, investigators ruefully admit their inability to reconstruct the past.

Some time later, Persian bad appeared on the scene next to its English twin. It sounds roughly like the English word and means the same. Noah Webster chose it as the source of Engl. bad, and his explanation stayed in all the subsequent editions until 1880. Those who copied from Webster sometimes cited two forms: bad and bud, meant as spelling variants of the same word. The Persian-English convergence has led many people astray. They may know it from old sources, but accidentally the great French linguist Antoine Meillet mentioned it in his book on Indo-European as a case of chance coincidence, and since his days this example has been repeated countless times. The moment one mentions the origin of bad, someone asks: “And what about Persian bad?” Answer: “Forget about it.” Such coincidences are not too rare, and more than a hundred and fifty years ago several other languages were discovered in which the sound group bad had the same meaning as in English. Also, we now know that bad is not the original form of the Persian word (its b- goes back to v-). But, even if its history began with b-, nothing would have changed in our reasoning, for we have no way of showing that the English adjective was borrowed from such a distant source, and as a cognate it looks suspicious, since no other language between Persian and English has a similar word.

Salt is good.

Salt is good.A third candidate for the etymon of Engl. bad used to be Gothic bauþs, which has been recorded in the Gothic New Testament in two senses: “deaf; dumb” and “tasteless,” the second sense being applied to salt in Luke 14: 34 (The King James Bible has: “Salt is good, but if the salt have lost his savour, wherewith shall it be seasoned?”). The author of the bad ~ bauþs comparison seems to have been Franciscus Junius, whose posthumous Etymologicum Anglicanum (1743) is a wonderful dictionary. Though an incomparable erudite, he could not help sharing the limitations of his epoch, and from our point of view many of his conjectures are clever curiosities at best. Apparently, the Gothic word had a broad meaning, referring to an impaired faculty, be it hearing, speech, or taste. Thus, it can hardly be called a synonym for bad. Perhaps it had some vague sense “deficient.” Also, the etymology of bauþs is problematic, and comparing one obscure word with another word equally obscure should be disallowed. Even seasoned scholars tend to violate this rule and invariably end up with wrong results. Returning to sound correspondences, we notice that the vowel a in Engl. bad does not match au in Gothic bauþs. Consequently, we are again on a wrong track. Lorenz Diefenbach, a distinguished student of Germanic and Indo-European antiquities, while discussing bad, rejected its relatedness to bauþs as early as 1851, but absurd etymologies die hard, and this one has reemerged more than once.

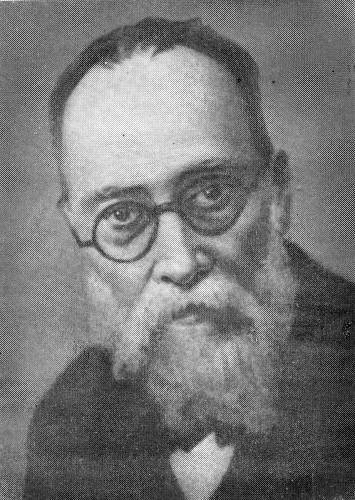

Antoine Meillet, who never took one bad thing for another.

Antoine Meillet, who never took one bad thing for another.I am not quite sure who was the first to cite German böse “bad, evil” in connection with Engl. bad. Perhaps this idea also goes back to Diefenbach (I have no earlier references), and it appears, wedged in between Persian bad and Gothic bauþs, in Webster’s 1864 edition, sometimes known as Webster-Mahn. Carl A. F. Mahn rewrote many of Webster’s untenable etymologies, but he had no clue to the origin of bad, so that repeating Diefenbach’s tentative (and discarded!) opinion looked tempting, but why should anyone have thought to compare bad and böse? They have only the first consonant in common! Hensleigh Wedgwood, Skeat’s predecessor, had a rare knack for stringing together look-alikes from many languages. His lists are often irritating because he had little regard for sound correspondences. Yet quite often, when confronted with his lists, one begins to wonder: can there be something in the wild goose chase he practiced? And of course, he would sometimes hit the nail on the head and even put Skeat right. So it is disappointing to see his short entry on bad (the same in all four editions), in which he cites German böse and Persian bud (sic), with hardly Gothic bauþs, added as an afterthought.

The regular readers of this blog will remember that I seldom indulge in such detailed surveys of the literature, but the history of bad is almost impenetrable, and the guesses have been so many that it will pay off to clear the decks before daring to say something new, and I do have a suggestion that may shed a tiny ray of light on the problem at hand. Naturally, I want to prolong the foreplay and will keep discussing the hypotheses known to me. Yet some of them I have left untouched and have no intention of returning to them. Bad as the past participle of bay “to bark” (to be bayed at is surely an ignoble thing); this is the idea of Horne Tooke, who traced most words to interjections and past participles. Bad as a contraction of beaten or rather beated (!; Charlies Richardson). Bad as a borrowing of Hebrew basch (an alternative etymology in Minsheu) or Rhaeto-Romance bada “pest” (Diefenbach). Bad as a word invented by English scribes who confused it with Latin peior “worse,” the comparative of the unattested pedimus, or a derivative of one of the four roots meaning “to bind,” “to emit sounds,” “to speak,” and “to bend” (a cascade of M. M. Makovskii’s fantasies), or simply one of the words for “base” (Walter Whiter). Too bad, isn’t it?

To be continued.

Image credits: (1) chèvre. (c) laurent via iStock. (2) Antoine Meillet. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The history of the word ‘bad’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Receiving “Laudato Si”: will Pope Francis be heard?

Pope Francis’ recent encyclical, Laudato Si, will be surrounded for some time by intense debate among and between journalists, columnists, Catholic journals, political leaders, and environmentally-focused scientists and NGOs. In other words, the fight over how it’s received is well underway.

In the 125 years or so that papal social encyclicals have been written, their reception has been hotly debated, with the most infamous such episode occurring in the pages of the National Review. In response to the document entitled Mater et Magistra, which emphasized ideas like public property and state intervention in the economy, the editors led with “mater si, magistra no” (mother yes, teacher no).

This aspect of reception turns on the notion of what is authoritative, a mostly intra-Catholic question about what the Pope—or more correctly, the magisterium—is competent to speak about. In the decades since that episode, Catholic opponents and critics of a social encyclical’s message have sometimes avoided the substance of disagreement by simply arguing that Catholics can prudentially disagree about whether theological concepts align (or not) with scientific knowledge and public policy. After climate science deniers and supporters of an unrestrained free market tire of challenging the Pope’s actual arguments, this will be the argument for simple dismissal of Laudato Si.

The most fruitful outcome for the Pope’s viewpoint in general public debate will likely be on the level of mid-range interpretive principles that tack between theological argument and public action, or what the Pope calls “lines of approach and action” (#163-201).

But to understand what the document means among rank-and-file Catholics, and how that might support the widespread change the Pope envisions, reception needs to be analyzed in two ways: the means by which Catholics hear about the encyclical and the organizational structures that Catholics have to reflect and act on it.

It’s fair to say that most Catholics will not have heard—or at least not have heard much—about Laudato Si in the news. Two days after the encyclical’s release, related daily Google searches were less than half of their peak on the day of its release. A similar Catholic pronouncement on nuclear weapons by the National Conference of Catholic Bishops in the mid-1980s, which drew extensive news coverage, was heard of by, at most, one third of Catholics.

If Catholics do hear about the encyclical, it is likely to come through parish-connected sources: bulletins, homilies, discussion groups, visiting speakers, and awareness campaigns. Research on congregations and parishes in the past decade has highlighted the role of clergy and parishioner social networks in shaping political opinion, albeit often in indirect, weak ways. In the mid-1980s, those Catholics that lowered their support for nuclear weapons, presumably in response to the Bishops’ interventions, were those most involved with their parish in terms of attendance and donations. That suggests the possibility of some parishioners receiving the Pope’s message on the environment and shifting their attitudes.

Francis’ high popularity could be an extra bolster in this regard, as a past Pope’s popularity appears to have influenced some Catholics’ opinions on two issues visibly promoted by that Pope, the death penalty and abortion.

The biggest challenge to reception among Catholics, however, is related to the organizational structures that could facilitate reflection and action. The translation of parishioner concern to public and political behavior seems to be a weakness in Catholic organizational life. Catholic parishes in particular seem to suffer an engagement deficit—a lower proportion of giving, volunteering, and participating than non-Catholic congregations. The causes are multiple: size, governance structure, resources base, and cultural norms that silence controversial speech. As a result, there is little opportunity or urgency for Catholics in most parishes. Without spaces to link religious identity to the environment, much less to organize action that transcends the gulf between individual charity and public need, it is unlikely that parishes will be the starting point for a Pope-inspired social transformation.

Neither Francis the spiritual leader nor Francis the pragmatic institutional head is relying on parishes, though. If the Pope has articulated a message that is even minimally received in the pews, that only adds to the intensive mobilization already seen among environmental advocacy groups and NGOs, Catholic or not. This could be an environmental turning point. If it is, it will echo Francis’ historical namesake, a person whom received a vision in a dilapidated chapel and, through life-long agitation among political, economic, and religious authorities sparked a wide-ranging social transformation.

Image credit: St. Rita of Cascia Catholic Church, Tacoma by Tony Webster. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Receiving “Laudato Si”: will Pope Francis be heard? appeared first on OUPblog.

The criminal enterprise of stealing history

After illegal drugs, illicit arms and human trafficking, art theft is one of the largest criminal enterprises in the world. According to the FBI Art Crime Team (ACT), stolen art is a lucrative billion dollar industry. The team has already made 11,800 recoveries totaling $160 million in losses. From Vincent Van Gogh to Pierre-Auguste Renoir to Pablo Picasso, some of the world’s most famous paintings are somewhere on this earth but are still no where to be found. Interpol reports that a majority of these crimes occur in private homes. Museums and places of worship are also commonly targeted. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, Massachusetts alone is missing $500 million worth of valuable pieces that went missing in a heist twenty-five years ago. Discover some of history’s most infamous art heists in this interactive map. Check out Grove Art Online and the Benezit Dictionary of Artists for more information about the artists and their stolen art.

Featured Image: Scheveningen beach in stormy weather by Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (The painting is presently lost following its theft from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in 2003.)

The post The criminal enterprise of stealing history appeared first on OUPblog.

Psychological deterioration in solitary confinement

It is difficult to imagine a more disempowering place than a solitary confinement cell in a maximum security prison. When opportunities for meaningful human engagement are removed, mental health difficulties arise with disturbing regularity. In the United States, where prisoners can be held in administrative segregation for years on end, stories of psychological disintegration are common. A senate judiciary subcommittee on solitary confinement was told of a prisoner whose response to his predicament was to stitch his mouth shut using thread from his pillowcase and a makeshift needle. Another chewed off a finger, removed one of his testicles, and sliced off his ear lobes. A third took apart the television set in his cell and ate it.

A person’s sense of self is forged in a social context and is maintained through interaction. In solitude, without the mirroring effect of others, the personality can threaten to disintegrate. This is a frightening prospect, especially when not anticipated.

Denied the opportunity for meaningful contact, the prisoner in solitary confinement is prevented from being fully human. It was observed of one of the litigants in a case involving the Pelican Bay Security Housing Unit in California that he had ‘not shaken another person’s hand in 13 years and fears that he has forgotten the feel of human contact. He spends a lot of time wondering what it would feel like to shake the hand of another person.’

When social contact is eliminated, the prisoner is left with a limited range of possibilities, prominent among which are truculence and withdrawal. But because belligerence requires energy and because isolation begets listlessness, a state of passivity often results. The restrictions of the physical environment find behavioural expression in a severely limited repertoire of movement, emotional constriction, and poverty of speech.

The potentially pathological side effects of penal isolation were recognised as soon as prisons designed according to the principle of separation opened their doors. During a visit to Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia in 1842, Charles Dickens met men and women who had been separated from their peers and who seemed to have unravelled as a result. The great novelist was shocked by what he witnessed, declaring in American Notes that:

I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain, to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body: and because its ghastly signs and tokens are not so palpable to the eye and sense of touch as scars upon the flesh; because its wounds are not upon the surface, and it extorts few cries that human ears can hear; therefore I the more denounce it, as a secret punishment which slumbering humanity is not roused up to stay.

London’s Pentonville prison, which was constructed along similar lines to Eastern State, was excoriated by The Times newspaper as a ‘maniac-making system’.

But there is a dimension of the solitary experience that is seldom recognised. This is the ability on the part of some prisoners to resist the assault on their identities that accompanies prolonged removal from company.

There are a number of common approaches for prisoners mitigate the harmful effects of long stretches of time spent alone in places not of their choosing and to timetables not of their design. One of these is to alleviate the burden of time by ensuring that there is less of it to deal with. This can be done by sleeping more and through the soporific effects of drug use. Some prisoners become absorbed in activities such as creative writing, craftwork, painting, or litigating. Others devise exercise regimes that do not require a training partner but that fill time and bring about a satisfying kind of tiredness.

If prisoners are to survive psychologically it is important that they shift their time orientation. Dwelling on the past and any associated remorse or regret, or obsessing about a future life which is unlikely to arrive in the wished-for format, introduces a degree of fretfulness that is inimical to successful navigation of the temporal landscape. Solitary prisoners who can achieve immersion in the present steal an important advantage over their environment.

A few manage to reinterpret their situation. Prisoners who can devise, or adopt, a frame of reference – often political or religious – that puts their pain in context seem to draw succour from their circumstances. Even in the most unpropitious of environments then, the capacity for human development cannot be completely eradicated.

Featured image: Prison Cell Bars. © tiero via iStock.

The post Psychological deterioration in solitary confinement appeared first on OUPblog.

Why care?

If your parents required care, would you or a family member provide care for them or would you look for outside help? If you required care in your old age would you expect a family member to provide care? Eldercare is becoming an important policy issue in advanced economies as a result of demographic and socio-economic changes. It is estimated that by 2030, one quarter of the population will be over 65 in both Europe and the USA (OECD, 2011). New funding regimes across the EU are often in the form of cash transfers and thus leave the choice of how to provide the care to families, and some worrying news about the quality of care provided in nursing homes combine to make families consider providing the care themselves as the better and cheaper option. In practice, this means that some family members may be under more pressure than others to choose to provide the care themselves, so a big question is what motivates them, and what happens to their satisfaction as they opt for providing the care themselves in house.

An important factor in the decision to care for one’s own elderly parents are social norms: the EUROFAMCARE study finds that emotional bonds and a sense of duty are very important to determine the decision to care. Whilst there is a wealth of research examining support services, there is less research on private informal care for elderly parents by their own children, and the focus of such research is typically on the labour supply of care-givers, rather than their satisfaction and the motivations behind their choice. And yet these issues affect many people; when looking at the respondents to the BHPS and focussing on those with living parents and whose parents are aged 70 and over, we find around 20% of women and 14% men state they provide some care for their parents.

When one looks more closely, some interesting facts emerge. It is not only that people are more likely to choose to care for their parents if they agree with the statement “Adult children have an obligation to look after their elderly parents” (a question asked to respondents to the British Household Panel Survey), but also that this makes them experience a positive return in terms of life satisfaction, which compensates for the negative impact that the hours of care themselves have.

There are important gender differences in the decision – women are overwhelmingly responsible for this provision of care for parents, both in and outside the household. They are also more likely to agree with the norm and more likely to experience this warm glow feeling from performing the care, and this is in spite of the fact that when it comes to the care itself they actually find it more burdensome than men, perhaps because they are in charge of the less pleasant tasks, such as personal care.

These gender differences are important and should be considered when evaluating the likely impacts of policy reform; financial and demographic considerations have been at the heart of elder care reforms. However, care provision needs to consider also the factors motivating unpaid care provision within households, which remains a key part of the provision. Although there may be a strong demand for eldercare services provided by the market, the pressure towards cash-for-care provision may not be the right solution in all situations, and that polices towards flexible employment accompanied by support to caregivers at home may be more appropriate for both those needing care and those who care for them. The difference between caring for a co-resident and non-resident parent is also important and needs to be taken into account in policy formulation. From a gender perspective, it is apparent that the effect of caring norms on women and men is not symmetric, and this should be taken into account for equity purposes when designing the relevant policies. Our results prove further that a gender disaggregated analysis is essential to understand the likely evolution of this sector.

Headline image credit: Clasped Hands, by Rhoda Baer. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why care? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 23, 2015

Elisabeth Bing and an American revolution in birth

On 15 May this year, Elisabeth Bing died at the age of 100. It is no exaggeration to say that during her long life she perhaps did more than any other individual to humanize childbirth practices in the United States. Obituaries and tributes to her rightly celebrate her role as a founding mother of the Lamaze movement in America and a lifelong advocate for improvement in maternity care.

From the vantage point of American obstetrics today, it is difficult to judge her efforts to improve birth a success. Cesarean section rates have been stuck at sky-high levels that approach nearly one-third of all US births — double what the World Health Organization considers optimal, to improve outcomes for mothers and babies. The US is also one of only eight countries to see a rise in maternal mortality over the past decade. That notorious club includes Belize, El Salvador, and South Sudan. Birthing women in the United States have a significantly greater chance of dying as compared to their counterparts in China or Saudi Arabia. Recently characterized as a “national embarrassment,” our infant mortality rate is equally shocking, ignominiously topping the list for OECD countries.

Unquestionably these indicators are nothing short of a scandal. There is an urgent need to reform the maternal health care system to turn these trends around and offer American women the kind of care that is their right. Reversal demands a call to arms to resume the unfinished revolution in maternity care that Elisabeth Bing and others started more than a half-century ago.

Born in Germany, Bing trained in Great Britain as a physical therapist. She became interested in the work of Grantly Dick-Read, who coined the term “natural childbirth” and believed that with proper support and prenatal education almost all women could give birth painlessly without the aid of anesthesia. Though she had her reservations about the effectiveness of the Read method, she began working with expectant mothers to promote his approach in the 1950s after her emigration to the United States.

Postpartum baby by Tom Adriaenssen. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Postpartum baby by Tom Adriaenssen. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia CommonsAmid the postwar baby boom, expectant mothers, if not medical professionals, were receptive to natural childbirth. The Read approach ran very much against the tide at the time, when middle class, urban, white American women routinely received powerful cocktails of anesthetics and sedatives. These drugs left women so confused that they sometimes had to be restrained lest they lash out violently at their caregivers. Women woke to find they had no memory of having given birth, which left many with feelings of disappointment. Setting off a national conversation about the inhumane treatment of laboring women, a letter in 1957 to the Ladies’ Home Journal described the “tortures” of the American delivery room and captured women’s sense of dissatisfaction. Natural childbirth held out the promise of an alternative: a more dignified birth for women, with supportive husbands at their sides.

By the close of the 1950s, Bing began to encounter writings about psychoprophylaxis, a similar method of childbirth preparation and relaxation that originated in the Soviet Union and that was popularized in France by obstetrician Fernand Lamaze. In 1959 she read the book Thank You, Dr. Lamaze, written by Marjorie Karmel, who had been Lamaze’s patient in Paris. Karmel’s description of her experience with psychoprophylaxis was an ah-ha moment for Bing. “I said, ‘Yes, this is it!’ as soon as I read it,” she later recalled. She contacted Karmel and these kindred spirits soon teamed up with obstetrician Benjamin Segal to found the American Society for Psychoprophylaxis in Obstetrics (ASPO), today known as Lamaze International, the largest non-profit organization dedicated to prenatal education.

ASPO was at the vanguard of a revolution in maternity care practices. In the 1960s and 1970s, ASPO’s core mission was the promotion of the Lamaze method, which used patterned breathing and conscious relaxation to enable women to give birth “awake and aware,” as it was described at the time. But the organization also advocated for a suite of interlocking practices intended to empower women and to make American birth more humane. Rooming-in moved newborns from nurseries into the mother’s room in order to facilitate bonding and breastfeeding. Husbands, partners, and, eventually, other loved ones were brought into labor and delivery rooms as birth “coaches” and companions to offer emotional and physical support to mothers and to establish an intimate relationship with the newborn from her very first moment of life. Bing and her colleagues undertook the challenge of educating medical professionals about the lack of evidence to support what were routine, but often unnecessary practices, such as enemas, pubic shaving, episiotomies, and the administration of intravenous fluids. Taken together, these changes worked to shift thinking about childbirth from a medical crisis to a normal life cycle event.

Bing’s revolution is incomplete. Childbirth in the US remains a highly medicalized procedure. Given the poor outcomes relative to other OECD countries, there are serious questions about the wisdom of our high-cost, high-tech, hospital-based, obstetrician-led maternity care. But it is worth remembering how far we have come in advancing maternity care from the “torture” of the 1950s. Many caregivers and mothers aspire to transform birth more fully into a woman-centered, gentle process. There could be no more fitting tribute to Bing’s life than to press on with the agenda that was her life’s work.

The post Elisabeth Bing and an American revolution in birth appeared first on OUPblog.

Book vs. Movie: Far From the Madding Crowd

A new film adaptation of Far From the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy was recently released, starring Carey Mulligan as the beautiful and spirited Bathsheba Everdene and Matthias Schoenaerts, Tom Sturridge, and Michael Sheen as her suitors. In this classic Victorian-era romance, Bathsheba is courted by these three, distinctly different suitors. As they all compete for her hand in marriage, she must choose between them, and eventually face the consequences of her fickle heart.

Have you seen the film? How does it compare to the novel? Compare this clip from the film with a corresponding excerpt from the Oxford World’s Classics edition of the novel, and let us know what you think.

Bathsheba’s aunt was indoors. “Will you tell Miss Everdene that somebody would be glad to speak to her?” said Mr Oak. (Calling one’s self merely Somebody, without giving a name, is not to be taken as an example of the ill-breeding of the rural world: it springs from a refined modesty of which townspeople with their cards and announcements have no notion whatever.)

Bathsheba was out. The voice had evidently been hers.

“Will you come in, Mr Oak?”

“Oh thank ’ee,” said Gabriel, following her to the fireplace. “I’ve brought a lamb for Miss Everdene. I thought she might like one to rear: girls do.”

“She might,” said Mrs Hurst musingly; “though she’s only a visitor here. If you will wait a minute Bathsheba will be in.”

“Yes, I will wait,” said Gabriel sitting down. “The lamb isn’t really the business I came about, Mrs Hurst. In short I was going to ask her if she’d like to be married.”

“And were you indeed.”

“Yes. Because if she would I should be very glad to marry her. D’ye know if she’s got any other young man hanging about her at all?”

“Let me think,” said Mrs Hurst, poking the fire superfluously . . . . . .

“Yes––bless you, ever so many young men. You see, Farmer Oak, she’s so good-looking and an excellent scholar besides––she was going to be a governess once, you know, only she was too wild. Not that her young men ever come here––but, Lord, in the nature of women she must have a dozen!”

“That’s unfortunate,” said Farmer Oak contemplating a crack in the stone floor with sorrow. “I’m only an everyday sort of man, and my only chance was in being the first comer . . . Well, there’s no use in my waiting, for that was all I came about: so I’ll take myself off home-along, Mrs Hurst.”

When Gabriel had gone about two hundred yards along the down he heard a “hoi-hoi!” uttered behind him in a piping note of more treble quality than that in which the exclamation usually embodies itself when shouted across a field. He looked round and saw a girl racing after him, waving a white handkerchief.

Oak stood still––and the runner drew nearer. It was Bathsheba Everdene. Gabriel’s colour deepened: hers was already deep, not as it appeared from emotion, but from running.

“Farmer Oak––I––” she said, pausing for want of breath, pulling up in front of him with a slanted face, and putting her hand to her side.

“I have just called to see you,” said Gabriel, pending her further speech.

“Yes––I know that,” she said panting like a robin, her face red and moist from her exertions, like a peony petal before the sun dries off the dew. “I didn’t know you had come to ask to have me, or I should have come in from the garden instantly. I ran after you to say––that my aunt made a mistake in sending you away from courting me––”

Gabriel expanded. “I’m sorry to have made you run so fast, my dear,” he said, with a grateful sense of favours to come. “Wait a bit till you’ve found your breath.”

“––It was quite a mistake––aunt’s telling you I had a young man already,” Bathsheba went on. “I haven’t a sweetheart at all––and I never had one, and I thought that, as times go with women, it was such a pity to send you away thinking that I had several.”

“Really and truly I am glad to hear that!” said Farmer Oak, smiling one of his long special smiles, and blushing with gladness. He held out his hand to take hers, which, when she had eased her side by pressing it there, was prettily extended upon her bosom to still her loud-beating heart. Directly he seized it she put it behind her, so that it slipped through his fingers like an eel.

“I have a nice snug little farm,” said Gabriel, with half a degree less assurance than when he had seized her hand.

“Yes: you have.”

“A man has advanced me money to begin with, but still, it will soon be paid off, and though I am only an everyday sort of man I have got on a little since I was a boy.” Gabriel uttered “a little” in a tone to show her that it was the complacent form of “a great deal.”

He continued: “When we be married, I am quite sure I can work twice as hard as I do now.”

He went forward and stretched out his arm again. Bathsheba had overtaken him at a point beside which stood a low, stunted holly bush, now laden with red berries. Seeing his advance take the form of an attitude threatening a possible enclosure if not compression of her person, she edged off round the bush.

“Why Farmer Oak,” she said, over the top, looking at him with rounded eyes, “I never said I was going to marry you.”

“Well––that is a tale!” said Oak, with dismay. “To run after anybody like this––and then say you don’t want him!”

“What I meant to tell you was only this,” she said eagerly, and yet half-conscious of the absurdity of the position she had made for herself: “that nobody has got me yet as a sweetheart, instead of my having a dozen as my aunt said; I hate to be thought men’s property in that way––though possibly I shall be had some day. Why, if I’d wanted you I shouldn’t have run after you like this; ’twould have been the forwardest thing! But there was no harm in hurrying to correct a piece of false news that had been told you.”

“O no––no harm at all.”

But there is such a thing as being too generous in expressing a judgment impulsively, and Oak added with a more appreciative sense of all the circumstances––“Well I am not quite certain it was no harm.”

“Indeed, I hadn’t time to think before starting whether I wanted to marry or not, for you’d have been gone over the hill.”

“Come,” said Gabriel, freshening again; “think a minute or two. I’ll wait a while, Miss Everdene. Will you marry me? Do Bathsheba. I love you far more than common!”

“I’ll try to think,” she observed rather more timorously: “if I can think out of doors; my mind spreads away so.”

“But you can give a guess.”

“Then give me time.” Bathsheba looked thoughtfully into the distance away from the direction in which Gabriel stood.

“I can make you happy,” said he to the back of her head across the bush. “You shall have a piano in a year or two––farmers’ wives are getting to have pianos now, and I’ll practise up the flute right well to play with you in the evenings.”

“Yes: I should like that.”

“And have one of those little ten-pound gigs for market––and nice flowers, and birds––cocks and hens I mean, because they be useful,” continued Gabriel, feeling balanced between poetry and practicality.

“I should like it very much.”

“And a frame for cucumbers––like a gentleman and lady.”

“Yes.”

“And when the wedding was over, we’d have it put in the newspaper list of Marriages.”

“Dearly I should like that.”

“And the babies in the Births––every man-jack of ’em! And at home by the fire, whenever you look up there I shall be––and whenever I look up there will be you.”

“Wait, wait, and don’t be improper!”

Her countenance fell, and she was silent awhile. He regarded the red berries between them over and over again to such an extent that holly seemed in his after life to be a cypher signifying a proposal of marriage. Bathsheba decisively turned to him.

“No: ’tis no use,” she said. “I don’t want to marry you.”

“Try!”

“I have tried hard all the time I’ve been thinking; for a marriage would be very nice in one sense. People would talk about me, and think I had won my battle, and I should feel triumphant, and all that. But a husband––”

“Well!”

“Why he’d always be there, as you say: whenever I looked up, there he’d be.”

“Of course he would––I, that is.”

“Well, what I mean is that I shouldn’t mind being a bride at a wedding if I could be one without having a husband. But since a woman can’t show off in that way by herself I shan’t marry––at least yet.”

“That’s a terrible wooden story!”

At this criticism of her statement Bathsheba made an addition to her dignity by a slight sweep away from him.

“Upon my heart and soul, I don’t know what a maid can say stupider than that,” said Oak. “But dearest,” he continued in a palliative voice, “don’t be like it!” Oak sighed a deep honest sigh––none the less so in that, being like the sigh of a pine plantation, it was rather noticeable as a disturbance of the atmosphere. “Why won’t you have me?” he appealed, creeping round the holly to reach her side.

“I cannot,” she said retreating.

“But why?” he persisted, standing still at last in despair of ever reaching her, and facing over the bush.

“Because I don’t love you.”

“Yes, but––”

She contracted a yawn to an inoffensive smallness so that it was hardly ill-mannered at all. “I don’t love you,” she said.

“But I love you––and as for myself, I am content to be liked.”

“O Mr Oak––that’s very fine! You’d get to despise me.”

“Never,” said Mr Oak, so earnestly that he seemed to be coming by the force of his words straight through the bush and into her arms. “I shall do one thing in this life––one thing certain––that is, love you, and long for you, and keep wanting you till I die.” His voice had a genuine pathos now, and his large brown hands perceptibly trembled.

“It seems dreadfully wrong not to have you when you feel so much,” she said with a little distress, and looking hopelessly around for some means of escape from her moral dilemma. “How I wish I hadn’t run after you.” However she seemed to have a short cut for getting back to cheerfulness, and set her face to signify archness. “It wouldn’t do, Mr Oak. I want somebody to tame me: I am too independent: and you would never be able to, I know.”

Oak cast his eyes down the field in a way implying that it was useless to attempt argument.

“Mr Oak,” she said with luminous distinctness and common sense: “You are better off than I. I have hardly a penny in the world––I am staying with my aunt for my bare sustenance––I am better educated than you––and I don’t love you a bit: that’s my side of the case. Now yours: you are a farmer just beginning, and you ought in common prudence if you marry at all (which you should certainly not think of doing at present) to marry a woman with money, who would stock a larger farm for you than you have now.”

Gabriel looked at her with a little surprise and much admiration. “That’s the very thing I had been thinking myself !” he naively said.

Farmer Oak had one-and-a-half Christian characteristics too many to succeed with Bathsheba: his humility, and a superfluous moiety of honesty. Bathsheba was decidedly disconcerted.

“Well then, why did you come and disturb me!” she said, almost angrily if not quite, an enlarging red spot rising in each cheek.

“I can’t do what I think would be . . . would be . . .”

“Right?”

“No: wise.”

“You have made an admission now, Mr Oak,” she exclaimed, with even more hauteur, and rocking her head disdainfully. “After that, do you think I could marry you? Not if I know it.”

He broke in, passionately. “But don’t mistake me like that. Because I am open enough to own what every man in my shoes would have thought of, you make your colours come up your face and get crabbed with me. That about you not being good enough for me is nonsense. You speak like a lady––all the parish notice it, and your uncle at Weatherbury is, I’ve heerd, a large farmer––much larger than ever I shall be. Mid I call in the evening––or will you walk along with me o’ Sundays? I don’t want you to make up your mind at once, if you’d rather not.”

“No––no––I cannot. Don’t press me any more––don’t. I don’t love you––so ’twould be ridiculous!” she said, with a laugh.

No man likes to see his emotions the sport of a merry-go-round of skittishness. “Very well,” said Oak, firmly, with the bearing of one who was going to give his days and nights to Ecclesiastes for ever. “Then I’ll ask you no more.”

Featured image: Far From the Madding Crowd by Alex Bailey. (c). Fox Searchlight Pictures via Vulture.com

The post Book vs. Movie: Far From the Madding Crowd appeared first on OUPblog.

In memoriam: Gunther Schuller

Gunther Schuller (1925-2015) was one of the most influential figures in the musical world of the past century, with a career that crossed and created numerous genres, fields, and institutions. Oxford offers heartfelt condolences to his family, and gratitude for the profound impact his work continues to have on music performance, study, and scholarship.

Schuller’s list of books with Oxford—Early Jazz (1986), Musings (1989), The Swing Era (1991), Horn Technique (1992), and The Compleat Conductor (1998)—span the range of his musical persona, and decades after their publication remain core titles in their own areas and in the music studies program at OUP. The close friendship between Schuller and his editor, the late Sheldon Meyer, legendary himself in the publishing world, is well-remembered among our ranks, as many of us at the press had the opportunity to meet and work with him on one project or another.

There will no doubt be countless remembrances which will tell of momentous achievements and deeply meaningful experiences. I have the tiniest of anecdotes to share, one that is on face silly and quirky, but to me speaks of a kind and genuine nature that may be easy to forget when considering a character of such import. Soon after I ‘inherited’ Gunther from Sheldon Meyer upon the latter’s retirement from OUP and amidst the fray of discussing his current work, I received a letter-sized envelope addressed to me from Newton Centre, MA. Inside was a carefully clipped article from the Boston Globe that related not to Gunther or his writing, or to anything we had been circling around in our recent missives. The byline named ‘Suzanne C. Ryan’ as its author, and written across the top of the page was the proclamation ‘You have a twin!!’ (indeed, my name is not that uncommon – another one of us was the longtime casting director of Law & Order). A number of these clipped articles followed over the months, and I smiled each time as I imagined Gunther Schuller reaching for his kitchen scissors when he noticed my doppelganger had penned another story for the Globe. This trivial account doesn’t hold any revelations and I can’t claim to have known Schuller well at all, but I am privileged to have had a glimpse of the delightful spirit of this intensely talented and accomplished man. We have lost a great one, but are grateful to him for all he gave.

Featured image: Conductor. © Jirsak via iStock.

The post In memoriam: Gunther Schuller appeared first on OUPblog.

Top 5 most infamous company implosions

Since the global financial crisis in 2008, the world has paid close attention to corporations and banks around the world that have faced financial trouble, especially if there is some aspect of scandal involved. The list below gives a brief overview of some of the most notorious company implosions from the last three decades.

1. Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae

In 2008 Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, two of the largest providers of finance to US home loans, fell on hard times, with the former owing $5.2 billion in July 2008, and the latter reporting a deficit of $10.6 billion the following year. The US government offered billions to prop the two companies up and avoid the US mortgage market grinding to a halt, despite both being insolvent under fair value accounting rules.

2. The Lehman Brothers

One of the most famed and complicated cases of recent years, the Lehman Brothers notoriously filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protect in 2008. With the company assets coming to $600 billion, the Lehman Brothers’ downfall signalled for plummeting confidence and stock prices on Wall Street, and harsher scrutiny of a culture in financial organisations for risk taking and extravagant displays of excess.

“You can’t say the word ‘scandal’ without thinking about Enron.”

3. Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company

This company became insolvent in 1984 because of bad loans bought from Penn Square Bank N.A. The Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company had once been the seventh-largest bank in the US in terms of deposits. An executive at Continental, John Lytle, went to prison for three and a half years after pleading guilty to fraud for “scamming” the company of $2.25 million and stealing nearly $600,000 in bribes for approving risky loan applications.

4. Pacific Gas & Electric Co

PG&E was forced into bankruptcy after California’s deregulation law was passed in 1996, which stopped the company from passing on higher costs to its customers. The company filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy in April 2001, and had accumulated $12 billion in debt and $36 billion in assets at the time of filing.

5. Enron

You can’t say the word ‘scandal’ without thinking about Enron. As one of the more infamous corporate collapses of recent years, the American energy company fell with $63.4 billion in assets, with their share price falling from $90 to £0.10 in the mid-2000s as a result of dodgy accounting practices used to hide loses of billions of US dollars. At the time, this was the biggest bankruptcy in US history. The scandal around Enron is now the subject of countless books, films, and even an award-winning Broadway play.

Featured image: NYC Lehman Brothers building, by Arnoldius (Own work). CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Top 5 most infamous company implosions appeared first on OUPblog.

June 22, 2015

How do we resolve reproductive material disputes?

Recent scientific advances have enabled us to have more control than ever over how and when we reproduce. However, these developments have resulted in serious legal discussions, raising the question: Do we lose the right to control what happens to our reproductive materials once they have left our body? Here, Jesse Wall discusses the courts’ different approaches for such disputes and the justification for their decisions.

* * * * * * * * *

Separated bodily material is difficult to categorize. Take gametes for example. Once extracted, sperm and ova fall somewhere between the category of objects and things, and the category of subjects, persons, and their bodies. For this reason, it is also difficult to legally categorize gametes. Property law takes care of our rights over things, and our right to bodily integrity protects our rights over our body, and it is unclear as to which of these legal categories the right to use and control gametes ought to fall into. As you may expect, it will depend on the gametes in question. Or, more precisely, it will depend on the functional relationship between the progenitor and their bodily material.

Two cases can help explain how our relationship with our bodily material can vary. In the first case (AW v CC [2005] ABQB 290), AW ‘extended a courtesy to a friend’ by gifting CC sperm to assist her in conceiving through in vitro fertilisation. CC did conceive and gave birth to twins. Four embryos remained. Although AW refused to consent to the use of the remaining embryos, the Queen’s Bench of Alberta held that the remaining embryos were CC’s property, as ‘they are chattels that can be used as she sees fit’, and ‘AW is not in a position to control or direct their use in any fashion’.

“The physical separation of bodily material did not sever the functional relationship between the progenitor and his bodily material.”

In a similar case (Evans v Amicus Healthcare [2004] EWCA 727), Evans and her partner (Johnson) created six embryos from their extracted gametes. Before an embryo could be implanted (but subsequent to Evans’ loss of natural fertility due to surgery on her ovaries), the relationship between Evans and Johnson ended. Johnson then sought to have the embryos destroyed. The Court of Appeal of England and Wales held that since the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 required the continuing consent of both parties from the commencement of treatment to the point of implant, Johnson was ‘entitled to withdraw his consent’ and ‘prevent both the use and continued storage of the embryo fertilised by the sperm.’

There are two important differences between these cases: one factual, one legal. The factual difference concerns the relationship between the progenitor and the bodily material. In AW v CC, the progenitor ‘gifted’ or relinquished his sperm. The sperm became a ‘mere object’ since the bodily material retained no connection with the progenitor and his intentions, tasks and projects. The physical separation of the bodily material from the body coincided with the functional separation between the body and the intentional use of the body. In Evans v Amicus Healthcare, the bodily material remained functionally equivalent to the body. The bodily material, like the body, remained the way in which the progenitor engages in tasks and projects. In this case, it was the way in which the progenitor engaged in the project of biological parenthood. The physical separation of bodily material did not sever the functional relationship between the progenitor and his bodily material. What these two cases illustrate is that bodily material is ambiguous; an item of bodily material can be a ‘mere object’ or it can remain functionally equivalent to the body.

“When we apply property law to ‘bodily auxiliaries,’ we risk denigrating the value of the bodily material by reducing something that may have value in its own right into something that has substitutional value.”

Consider how walking sticks are the same. For a blind person ‘finding ‘one’s way among things,’ walking stick may initially be one object among many other objects. Yet ‘once the stick has become a familiar instrument,’ Merleau-Ponty (1945/2003, at 176) explains, ‘the world of feelable things recedes and now begins, not at the outer skin of the hand, but at the end of the stick.’ At which point, the walking stick becomes a ‘bodily auxiliary’ since ‘the stick is no longer an object perceived by the blind man, but an instrument with which he perceives.’ The walking stick no longer has a detached, mechanical relationship with its owner. Rather, like the body, the walking stick becomes the way in which the person experiences the world and engages in tasks and projects. It represents a point of view of the world (that the blind person can have no point of view of). Bodily material may also become a ‘bodily auxiliary’; it may continue to be engaged in tasks that are functionally equivalent to the tasks of the body.

The second difference between the two cases concerns the application of different branches of law to address the disputes. Property law governed the use of the embryo in AW v CC, whereas statutory provisions governed the use of the embryo in Evans v Amicus Healthcare. This is convenient. It is convenient because the legal distinction maps onto the functional distinction (in these two cases). The sperm in AW v CC was a mere object and the sperm in Evans v Amicus Healthcare was a bodily auxiliary. To the extent that property rights protect preferences and choices that exist independently of the rights-holder, it is appropriate for property law to govern the use of mere objects. Yet, when it comes to ‘bodily auxiliaries’—which, like the body, enable preferences and choices that are necessarily associated with a particular person—the application of property law is conceptually and doctrinally problematic.

The problem is that property law provides a particular way of governing the transfer of things, the sale of things, and the remedial consequences of unlawfully interfering with things. The structure of property law is premised upon the contingent relationship between the owner and owned thing and the substitutional value of the item of property. However, the use and control of bodily material may be premised on a particular relationship between the progenitor and the bodily material and may have value in its own right. When we apply property law to ‘bodily auxiliaries,’ we risk denigrating the value of the bodily material by reducing something that may have value in its own right into something that has substitutional value.

Image Credit: ’16-cell stage of a sea biscuit’ by Bruno Vellutini. CC BY SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How do we resolve reproductive material disputes? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers