Oxford University Press's Blog, page 654

June 15, 2015

How do we remember the Battle of Waterloo?

From the moment the news of the victory was announced in London, Waterloo was hailed as a victory of special significance, all the more precious for being won on land against England’s oldest rival, France. Press and politicians alike built Waterloo into something exceptional. Castlereagh in Parliament would claim, for instance, that Waterloo was Wellington’s victory over Napoleon and that ‘it was an achievement of such high merit, of such pre-eminent importance, as had never perhaps graced the annals of this or any other country till now’. It had been a decisive victory, perhaps even an iconic victory, and certainly, in the British public’s eyes, a British one. In the moment of victory Waterloo was hailed as a national triumph and a testimony to British martial qualities of grit and stoicism in the face of the enemy. The contribution of the other nations that contributed to the Allied army (Dutch, Belgians, Hanoverians, Nassauers, even the Prussians) was singularly overlooked.

The initial jubilation that greeted the news of victory and the publication of the Waterloo Dispatch was undoubtedly spontaneous – joy at the victory and at the defeat of Napoleon, relief that the war was finally over – but spontaneous celebration soon gave way to official ceremonies with a more political purpose. Across Britain and throughout the British Empire Wellington and Waterloo were celebrated in the names of squares, bridges and railway stations, of mills and factories, of new towns and cities that were springing up from Canada to New Zealand. Particular emphasis was placed on Scottish and Irish involvement as the British government sought to inspire loyalty to what was still a relatively disunited Kingdom. Pride in Waterloo was used to cement the bonds that held Britain and the Empire together.

Others had greater difficulty in commemorating the battle, or saw it as less integral to their national identity. Prussia – and later in the century Germany – saw Leipzig as the decisive battle that had not only ended the Napoleonic Wars but had brought German together in a common cause to defend their territory against outside invasion. Berlin in the post-war years did have its Belle-Alliance Platz, and Hanover, unsurprisingly as the home of the King’s German Legion, feted its own contribution to the victory. Similarly, German celebrations focussed strongly on Blücher, and the contribution of the Prussians to the victory under their 73-year-old commander. But the level of celebration, and the commemoration, remained muted when compared to Britain.

Waterloo Lion, by Isabelle Grosjean. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Waterloo Lion, by Isabelle Grosjean. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Holland, the other major contributor to the Allied army at Waterloo, gave the battle rather more prominence, naming a major street in Amsterdam the Waterlooplein, and constructing the first and most eye-catching memorial, on the battlefield itself, the Butte du Lion, to commemorate where their young Prince Willem had sustained a wound in the fighting. If Waterloo signalled Napoleon’s ultimate defeat, the end of the war also marked a key moment in the rise of the House of Orange, as Orange rule was restored to Holland and Dutch honour was secured through the annexation of the southern Netherlands, today’s Belgium. Waterloo remains for the Dutch a dynastic triumph.

For France, of course, there was little to celebrate. Napoleon had lost his army at Waterloo as it was routed in the final retreat, and in the days that followed he was forced to abdicate for a second time. There would be no memorials to Waterloo, either in Paris or in provincial France, and the monument to the French troops on the battlefield itself would not be built till 1904.Throughout the nineteenth century France – encouraged by the poetry of Stendhal and Hugo – would regard Waterloo as a ‘glorious defeat’, epitomized by the last stand of the Imperial Guard and the (doubtless apocryphal) mot de Cambronne. The scale of the disaster may even have served to enhance Napoleon’s legend for a romantic age. The French would always see Waterloo as Victor Hugo’s ‘morne plaine’.

There are memorials to Waterloo and to Wellington’s victory across Britain and across the world: statues, victory arches, columns, military monuments. Streets, squares and bridges are named in their honour, and public subscriptions were opened to fund local memorials. Towns and villages took the name of Waterloo, including one on the Fylde in Lancashire and Waterlooville in Hampshire. In Canada Waterloo has become a major city in Ontario; in New Zealand the capital is Wellington; and no fewer than fourteen American states have towns called after the battle. In Spanish America, too, Wellington was hailed as the general who had driven Napoleon out of Spain. The Belgian historian Yves Vander Cruysen has drawn up a list of all the communities he can find that are named for the battle, and in all he has found 124. They are, of course, heavily concentrated in the English-speaking world, colonized in many cases by men who had fought at Waterloo and who, on being demobilized, sought adventure elsewhere.

Featured image credit: “Braine-L’Alleud – Butte du Lion dite de Waterloo”, by Jean-Pol Grandmont. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How do we remember the Battle of Waterloo? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 14, 2015

“Deflategate,” Fox News, and frats: this year in public apologies

Since publishing Sorry About That a year ago, I’ve been trying to keep track of apologies in the news. Google sends me a handful of news items every day. Some are curious (“J.K. Rowling issues apology over slain ‘Harry Potter’ character”), some are cute (“Blizzard 2015: Meteorologist apologizes for ‘big forecast miss’”), and some are sad (“An open apology to my kids on the subject of my divorce”).

A good apology meshes moral awareness and social repair work. As your mother probably told you when you were a child, you must say what you did wrong and sincerely express that you are sorry. In the best possible case, you are able to say what will be different in the future and make some restitution or other corrective action. A weak apology often fails to identify the harm done, perhaps because it is too embarrassing to name. Instead of actually apologizing for something, people may just say that they were wrong or that they have regrets—or, if they are really casual about things, offer the phrase, “My bad.” Weak apologies can also suffer from excessive explanation, blame-shifting, and excuses. “I apologize,” someone will say, “but…” How genuine have public apologies come across this year so far? Let’s take a look at some of the noteworthy ones from the first part of 2015.

In January, Fox News found itself apologizing for its reporting on alleged “no-go zones” in England and France, issuing a series of retractions and corrections. Summing it all up, Fox anchor Julie Banderas said, “Over the course of this last week, we have made some regrettable errors on air regarding the Muslim population in Europe.” She catalogued the mistakes and ended by saying, “We deeply regret the errors, and apologize to any and all who may have taken offense, including the people of France and England.”

“Benedict Cumberbatch” by Sam (Honeyfitz). CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Benedict Cumberbatch” by Sam (Honeyfitz). CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. Also in January, actor Benedict Cumberbatch apologized for using the word “colored” when discussing the opportunities for black actors in the United States and the United Kingdom. Cumberbatch told People magazine,“I offer my sincere apologies. I make no excuse for my being an idiot and know the damage is done. I can only hope this incident will highlight the need for correct usage of terminology that is accurate and inoffensive.” Cumberbatch pointed out that he felt ashamed and foolish and that he “apologize[d] again to anyone who I offended for this thoughtless use of inappropriate language about an issue which affects friends of mine and which I care about deeply.”

Both Fox and Cumberbatch rely on the stock phrasing of apologizing to anyone who was offended, but Cumberbatch does a much better job of indicating his embarrassment and articulating why it was important for him to apologize. Fox, on the other hand, merely regrets the errors without chagrin or reference to what should have been the case journalistically.

February began with another journalistic apology, this one from NBC anchor Brian Williams for misstatements about his involvement in a ground fire incident in Iraq. On his Nightly News broadcast, William said he “made a mistake” in recalling events. “I want to apologize,” he added. “I said I was traveling in an aircraft that was hit by RPG fire. I was instead in a following aircraft.” Williams characterized his remarks as “a bungled attempt” to thank veterans. His statement failed because he was unable to give the transgression any better name than a mistake, resulting in an incomplete, impersonal apology. Williams might have done better by addressing the possibility that self-promotion was a motive rather than honoring veterans, but that would have been a harder statement to make.

Also in February, Alex Rodriguez, baseball player for the New York Yankees, issued a short handwritten letter “to the fans” in which he said he took “full responsibility for the mistakes that led to my suspension” and offered “regret that my actions made the situation worse than it needed to be.” He added that “I can only say I’m sorry” and that he was ready to put this behind him and return to baseball. Despite writing out his apology long-hand, A-Rod was unable to convey sincerity since his apology lacked any real reflection and discussion about his suspension, just references to “mistakes” and a “situation.” February was a bad month for apologies.

“Alex Rodriguez” by Keith Allison. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Alex Rodriguez” by Keith Allison. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. In March, expelled University of Oklahoma student Levi Pettit, the 20-year-old videotaped leading a racist chant at the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity, apologized. Pettit began by saying that he was “deeply sorry” for the pain his actions caused. He noted that what he had said in the chant was “mean, hateful, and racist” and that there were “no excuses” for his behavior, adding that he would “be deeply sorry and deeply ashamed of what I have done for the rest of my life” and was committed to being a different person in the future. Pettit’s apology was successful not just because of its naming of what he had done and would do in the future, but because he delivered it together with African American leaders from Oklahoma, showing a willingness not just to apologize publicly, but to face some of those he had harmed by his words and actions.

In April, Rolling Stone managing editor Will Dana apologized further for last November’s story “about a University of Virginia student’s account of her alleged gang rape at a campus fraternity house. Dana officially retracted the story, saying “We would like to apologize to our readers and to all of those who were damaged by our story and the ensuing fallout, including members of the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity and UVA administrators and students. Sexual assault is a serious problem on college campuses, and it is important that rape victims feel comfortable stepping forward. It saddens us to think that their willingness to do so might be diminished by our failings.” Dana’s apology, and that of Sabrina Rubin Erdely, the author of the retracted story, didn’t just acknowledge mistakes but also identified that harm caused by their poor reporting—the effect on other and future victims of rape.

May was notable too for an apology that did not come—from the New England Patriots quarterback, Tom Brady. Following the release of the Wells report, which concluded that it was likely that Brady knew that staffers were deflating footballs, the four-time Super Bowl winner merely said, “I don’t have really any reaction,” adding that he had not had time “to digest it fully but when I do I’ll be sure to let you know how I feel about it.” We’ll see what the future brings for Tom Brady.

Then again, we still have six months left in 2015, so we’ll just have to wait and see what the rest of the year brings in the way of good and bad public apologies.

Image Credit: “Sorry” by Alexa Clark. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post “Deflategate,” Fox News, and frats: this year in public apologies appeared first on OUPblog.

Oil, arms, and corruption: a poisonous nexus?

While world military spending has fallen slightly in recent years, some regions, notably Africa and the Middle East, have seen continuing rapid increases. When SIPRI published our annual military expenditure data for 2014 this April, we featured a list of the 20 countries with ‘military burdens’ – the share of military expenditure in GDP – above 4%. This compares with only 13 in 2005.

There are three features that are notable of these countries. First, not surprisingly, many (14) were either in conflict or had a recent history of armed conflict. Second, only 3 of the 20 were functioning democracies. The third feature was oil: 13 of the 20 countries, and all of the top seven (Oman, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan, Chad, Libya, the Republic of Congo, and Algeria) are major oil producers.

The Middle East, home to many of the world’s top oil producers, has always been a region of high military spending. In recent decades, however, there has been a surge in military spending in many countries whose oil booms have been more recent affairs. In Africa, most prominent are the continent’s top two spenders: Algeria, whose military spending has trebled in real terms since 2005, and increased seven-fold since 1995; and Angola, whose spending has increased 270% since the end of their civil war in 2002. But also noteworthy are Chad, whose spending increased by a factor of 6.5 in just two years from 2005 to 2007, as their new oil pipeline came online; Republic of Congo (spending quadrupled since 2005); Nigeria, South Sudan, and even Ghana, whose spending almost doubled in a single year in 2011 as their oil revenues came online, albeit from a very low starting point. Outside Africa, Azerbaijan, Russia, Kazakhstan, Ecuador, and Vietnam are notable examples.

Of course, with new oil resources (or high oil prices, as were seen over most of the past decade), comes increased GDP. But in most of the cases above, military spending has increased not only in absolute terms but even as a share of GDP. Why should oil (and more generally natural resource) revenues be linked to high military spending and arms acquisition? There are a number of possible reasons:

Source of revenue: First, the proceeds from resource exports provide a direct source of income to the government without taxing the general population. Large-scale military spending that might be highly unpopular if paid for by the people at large may be easier to get away with if it is from an external source of funding – even though the opportunity cost is the same. Conflict: Resource exploitation can itself be a source of grievance and conflict, due to environmental damage, the failure to benefit local populations, and/or disputes over how the spoils are divided—and thus of higher military spending. The Niger Delta region of Nigeria is an example of the first two, and the current wars in South Sudan of the third. Gates of oil refinery in Port Harcourt, Nigeria by sixoone. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Corruption in the arms trade: Major international arms deals are frequently the subject of vast bribes, in both the developing and developed worlds. The multi-billion pounds Al Yamamah oil-for-arms deals between the UK and Saudi Arabia in the 1980s and 1990s, where perhaps over a billion pounds were paid in bribes to top Saudi decision-makers, is a particularly egregious example. The secrecy involved in such deals makes them an ideal vessel for corruption, and thus for channeling the proceeds of natural resource revenues into the bank accounts of the elite. Corruption in the military establishment: It is not just arms acquisition that can be subject to corruption in military spending. Skimming of pay, the use of ‘ghost’ soldiers, corruption in awarding of contracts, selling or renting of military property, and the awarding of senior positions can all be means by which the military budget can be a lucrative source of income for elites. The military may not be unique in this, but blanket secrecy and the effective impunity from investigation and prosecution enjoyed by the military in many countries may make it particularly susceptible. Nigeria is one country where endemic corruption in the military has severely impeded its effectiveness, in particular in the fight against Boko Haram. Angola is one of the most corrupt countries in the world according to Transparency International, and is a major reason why vast oil wealth sits alongside extreme poverty. Despite their $6 billion dollar, 5.2% of GDP military spending, they actually buy very little by way of major armaments. Very little is known about Angola’s military spending, but the question should be asked as to whether it is really providing for national defence, or if it is more a huge vehicle for patronage and enrichment of favoured groups. The “rentier state”: The idea of the ‘rentier state’ encompasses many of the phenomena discussed above. When a state derives the bulk of its revenues from the sale of natural resources, the whole nature of the state and its priorities may be distorted. Protecting the source of these resource rents may become more important for regime survival than promoting economic development. Politics, even in a nominally democratic country, may become more about the division of the spoils between different groups than about how the country is governed. Thus, the military become a key means by which the continuance of the regime and access to resource rents are guaranteed. In a polity corrupted by the centrality of resource revenues, the military may be the most corrupt institution of all.

Gates of oil refinery in Port Harcourt, Nigeria by sixoone. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Corruption in the arms trade: Major international arms deals are frequently the subject of vast bribes, in both the developing and developed worlds. The multi-billion pounds Al Yamamah oil-for-arms deals between the UK and Saudi Arabia in the 1980s and 1990s, where perhaps over a billion pounds were paid in bribes to top Saudi decision-makers, is a particularly egregious example. The secrecy involved in such deals makes them an ideal vessel for corruption, and thus for channeling the proceeds of natural resource revenues into the bank accounts of the elite. Corruption in the military establishment: It is not just arms acquisition that can be subject to corruption in military spending. Skimming of pay, the use of ‘ghost’ soldiers, corruption in awarding of contracts, selling or renting of military property, and the awarding of senior positions can all be means by which the military budget can be a lucrative source of income for elites. The military may not be unique in this, but blanket secrecy and the effective impunity from investigation and prosecution enjoyed by the military in many countries may make it particularly susceptible. Nigeria is one country where endemic corruption in the military has severely impeded its effectiveness, in particular in the fight against Boko Haram. Angola is one of the most corrupt countries in the world according to Transparency International, and is a major reason why vast oil wealth sits alongside extreme poverty. Despite their $6 billion dollar, 5.2% of GDP military spending, they actually buy very little by way of major armaments. Very little is known about Angola’s military spending, but the question should be asked as to whether it is really providing for national defence, or if it is more a huge vehicle for patronage and enrichment of favoured groups. The “rentier state”: The idea of the ‘rentier state’ encompasses many of the phenomena discussed above. When a state derives the bulk of its revenues from the sale of natural resources, the whole nature of the state and its priorities may be distorted. Protecting the source of these resource rents may become more important for regime survival than promoting economic development. Politics, even in a nominally democratic country, may become more about the division of the spoils between different groups than about how the country is governed. Thus, the military become a key means by which the continuance of the regime and access to resource rents are guaranteed. In a polity corrupted by the centrality of resource revenues, the military may be the most corrupt institution of all. The idea of the ‘resource curse’ – whereby natural resource wealth fails to benefit the population as a whole, and instead becomes a source of conflict and corruption – is widely discussed. The role of military spending as a key building-block in this poisonous nexus perhaps merits closer attention.

Image credit: Oil pump in Baku by Gulustan. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Oil, arms, and corruption: a poisonous nexus? appeared first on OUPblog.

Looking for God in the sociology of religion and in Game of Thrones

Religion has played an increasingly significant part in Season 5 of the HBO series Game of Thrones, with the ‘Faith Militant’ taking over the reins of power at King’s Landing, mostly unopposed. Yet Internet discussions indicate that some viewers have found this storyline unsatisfying, as the Sparrows are depicted as crazed religious fanatics, piously obsessed with driving out vice and immorality from the city. George R. R. Martin has described his inspiration for the Sparrows’ rise to power and reforming zeal as the Protestant Reformation, while also drawing on his own Roman Catholic upbringing, in conceptualizing the broader background of the Faith of the Seven in Westeros. Commentators have suggested that the Sparrows’ storyline might be more compelling if the motivations of the Faith Militant were portrayed more in terms of a grassroots religious revival movement, emerging out of protest against the inequality, violence, and corruption pervading Westeros. Perhaps. But what is also missing – at least in the HBO series (I haven’t read the books) – is any depiction of the Sparrows’ sense of a relationship with God or the divine (specifically here ‘the Seven’) and how this relationship then motivates their actions.

This absence of the divine in the portrayal of the Faith Militant maybe reflects the fact that God is something of a taboo in contemporary society, far more so than sex or violence, as sociologist of religion, Linda Woodhead, has commented in her research on religion in modern Britain. But, perhaps surprisingly, God has also been largely missing as an actor in both the sociology and the anthropology of religion. This is in part, as anthropologist Jon Bialecki has noted, due to social scientific disciplinary presumptions of ‘methodological atheism’, which, for the purpose of study, takes religious concepts and figures to be human externalizations, and brackets out the possibility of their having a divine referent. Within the sociology of religion, the study of God and sacred figures as social actors has mostly been avoided, out of concerns that this raises metaphysical questions beyond the empirical limits of the subject. Meanwhile in anthropology, relations with sacred figures have often been constructed as fetishistic in colonial encounters. Thus there has been a tendency in both disciplines to treat deities and sacred figures as projections of human needs, or as epiphenomena of broader social and economic processes, or to ignore questions concerning transcendental orientations altogether. Yet relations with supernatural beings are amenable to social scientific study, since they are always inevitably mediated by actions, symbols, gestures, rituals, and other things we can examine. In fact in recent years, there has been a growing interest among anthropologists in how individuals relate to the divine or transcendental.

The Seven Faced God. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Game of Thrones Wiki

The Seven Faced God. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Game of Thrones Wiki This growing body of literature opens up an important direction for work in the broader study of religion, since to really understand the experience of faith means engaging with people’s different forms of sociality with sacred figures. This doesn’t mean entering into theological speculation. Rather, it suggests recognizing that any empirical account of religious lives, concerned with the reality of people’s lived experiences, needs to consider how these relationships with transcendental and sacred figures shape and are shaped by their relationships with other social actors. Also, to explore the material and embodied means by which these relationships are formed and experienced. Understanding the experiences of conservative evangelical Christians, for example, requires attending to their sense of relationship with God. Specifically, how their experience of God as pure coherence can lead them to both desire coherence and to become conscious of forms of subjective fragmentation within themselves, leading them to work to form themselves as oriented towards God and as ‘aliens and strangers’ in the world. This is somewhat different from some charismatic evangelicals’ modes of relationality, in which God is experienced less as a holy ‘Other’ and more as someone ‘who wants to be your friend’ anthropologist Tanya Lurhmann found in her research with the Vineyard movement in Chicago and Northern California.

The Sparrows come across as simplistic stereotypes in Game of Thrones in part because, as viewers, we can’t really understand their motivations, with their relationships with and devotion to the God of Seven bracketed out. Academic portrayals of contemporary religious lifeworlds can also seem flat when they fail to engage with the complex textures of individuals’ experiences of sacred figures in their everyday lives. For example, the ways they experience these characters as making demands of them, offering particular comforts, and exerting pressures on their other social relations. As Robert Orsi argues, many scholars of religion end up feeling somewhat dissatisfied with explanations of religion purely in social terms. This is not because they don’t believe in the value of such analyses, but rather because they fall short of the realness of the phenomena they are attempting to describe in people’s experience. Part of the challenge of the turn towards practice, embodiment and materiality in the sociology of religion is to consider these modes of sociality with sacred figures. A challenge that, as Orsi acknowledges, potentially unsettles established modern binaries of knowing, such as the real and imagined, past and present, and self and other.

Featured image credit: Jonathan Pryce as The High Sparrow, in the HBO series’ Game of Thrones. (c). HBO via Game of Thrones Wiki.

The post Looking for God in the sociology of religion and in Game of Thrones appeared first on OUPblog.

Paradox and flowcharts

The Liar paradox — a paradox that has been debated for hundreds of years — arises when we consider the following declarative sentence:

“This sentence is false.”

Given some initially intuitive platitudes about truth, the Liar sentence is true if and only if it is false. Thus, the Liar sentence can’t be true, and can’t be false, violating out intuition that all declarative sentences are either true or false (and not both).

There are many variants of the Liar paradox. For example, we can formulate relatively straightforward examples of interrogative Liar paradoxes, such as the following Liar question:

“Is the answer to this question ‘no’?”

If the correct answer to this question is “yes”, then the correct answer to the question is “no”, and vice versa. Thus the Liar question is a yes-or-no question that we cannot correctly answer with either “yes” or “no”.

Interestingly, I couldn’t think of any clear examples of exclamatory variants of the Liar paradox. The closest might be something like the following Liar exclamation:

“Boo to this very exclamation!”

If one (sincerely) utters this sentence, then one is simultaneously exhibiting a positive attitude towards the Liar exclamation (via making the utterance in the first place) and a negative attitude towards the exclamation (via the content of the utterance). But I am far from sure that this leads to a genuine contradiction or absurdity.

Figure 1, image courtesy of Roy T Cook. Please do not reproduce without permission

Figure 1, image courtesy of Roy T Cook. Please do not reproduce without permission There are, however, a number of very interesting imperative versions of the Liar. The simplest is the following, popularized in the videogame Portal 2:

“New Mission: Refuse this Mission!”

Accepting the mission requires refusing the mission, and refusing the mission requires accepting it. Thus, the mission is one we cannot accept, yet cannot refuse.

Let’s consider a slightly different kind of interrogative paradox: algorithmic paradoxes. Now, an algorithm is just a set of instructions for effectively carrying out a particular procedure (often, but not always, a computation). One of the most informative and useful ways of representing algorithms is via flowcharts. But if we aren’t careful, we can formulate flowcharts that provide instructions for procedures that are impossible to implement.

Consider the flowchart in Figure 1. It has two states: the start state, where we begin, and the halt state, which indicates that we have completed the procedure in question when (if?) we reach it. Of course, not every flowchart represents a procedure that always halts. Some procedures get caught up in infinite loops, where we repeat the same set of instructions over and over without end. In particular, the fact that a flowchart contains a halt state doesn’t always guarantee that the procedure represented by the flowchart will always halt.

The start state in Figure 1 contains a question, and arrows leading from it to other (not necessarily distinct) states corresponding to each possible answer to that question. In this case the question is a yes-or-no question, and there are thus two such arrows.

So Figure 1 seems to be a perfectly good flowchart. The question to ask now, however, is this: Can we successfully carry out the instructions codified in this flowchart?

The answer is “no”.

Here’s the reasoning: Assume you start (as one should) in the start state. Now, when carrying out the first step of the procedure represented by this flowchart, you must either choose the “yes” arrow, and arrive at the halt state, or choose the “no” arrow and arrive back at the start state. Let’s consider each case in turn:

Figure 2, image courtesy of Roy T Cook. Please do not reproduce without permission

Figure 2, image courtesy of Roy T Cook. Please do not reproduce without permission If you choose the “yes” arrow and arrive at the halt state, then the procedure will halt. So the correct answer to the question in the start state is “no”, since carrying out the algorithm only took finitely many steps (in fact, only one). But then you should not have chosen the “yes” arrow in the first place, since you weren’t trapped in an infinite loop after all. So you didn’t carry out the algorithm correctly.

If you choose the “no” arrow and arrive back at the start state, then you need to ask the same question once again in order to determine which arrow you should choose next. But you are in exactly the same situation now as you were when you carried out the first step of the procedure. So if the right answer to the question was “no” at step one, it is still “no” at the step two. But then you once again end up back at the start state, and in the same situation as before, and so you should choose the “no” arrow a third time (and a fourth time, and a fifth time, … ad infinitum). So you never reach the halt state, and thus you are trapped in an infinite loop. As a result, the correct answer to the question is “yes”, and you should not have chosen the “no” arrow in the first place. So you didn’t carry out the algorithm correctly.

Thus, the Liar flowchart represents an algorithm that is impossible to correctly implement.

Like many paradoxes, once we have seen one version it is easy to construct interesting paradoxical or puzzling variants. Once such variant, closely related to the No-No Paradox (go on – look it up!), is the construction given in Figure 2, which involves two separate flowcharts.

In this case we can carry out both algorithms correctly, but never in the same way. If we choose the “yes” arrow when implementing the first flowchart, then we must choose the “no” arrow over and over again when implementing the second flowchart, and if we choose the “no” arrow (over and over again) when implementing the first flowchart then we must choose the “yes” arrow when implementing the second flowchart. So we have two identical flowcharts, but we can only correctly carry out both procedures correctly by doing one thing in one case, and something completely different in the other.

Not a full-blown paradox, perhaps, but certainly puzzling.

Featured image credit: “Ripples”. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Paradox and flowcharts appeared first on OUPblog.

June 13, 2015

What is the history of the word ‘hip’?

James Brown was famously introduced by Lucas ‘Fats’ Gonder at the Apollo Theater in the early 1960s as ‘The Hardest Working Man in Show Business,’ an epithet that stuck with Brown for his entire life. It is a fitting term for the word hip–the hardest working word in the lexicon of American slang. For more than 110 years, hip has found a prominent place in our slang, reshaping and repurposing itself every few decades to carry itself forward, from the early twentieth century’s hip to today’s hipster movement.

Hep or hip

For years hep and hip were used interchangeably. Hep was recorded first, on 9 May 1903, in the Cincinnati Enquirer. The first recorded example of this sense of hip (meaning ‘very fashionable’) is found in George V. Hobart’s 1904 slang-rich short novel Jim Hickey: A Story of One-Night Stands: ‘Say Danny, at this rate it’ll take about 629 shows to get us to Jersey City, are you hip?’ A year earlier, cartoonist T.A. Dorgan had used the names ‘Joe Hip’ and ‘old man Hip,’ but the first full-blown hip would have to wait until 1904. The ‘aware’ sense of hip here quickly grew to include world-wise, sophisticated, and up-to-date with trends in music, fashion, and speech. It expanded to the adjectival hipped in 1920, and to a verb hip in 1932, meaning ‘to make aware.’

Hip may be a simple, three-letter word, but its etymology (when used in this way) is a mystery. It is a textbook example of lexical polygenesis; there are many unproven explanations for hip’s etymology. Some involve the body part (boots laced up to the hip, a wrestler having an opponent on his hip, a flask of liquor carried in the hip pocket, or the opium smoker reclined on the hip), or an apocryphal character named Hip or Hep (a Chicago saloon-keeper, a Cincinnati detective, a circus man), or the ploughman’s exhortation of ‘Hep!’ If any of the competing explanations rings the truest, it is probably the suggestion by Holloway and Vass in The African Heritage of American English that hip is derived from Senegalese slaves, for whom xipi in their native Wolof language meant ‘to have your eyes open, to be aware.’

Hepcats and hipsters

Hep gave way to hepcat, meaning a knowledgeable and fashionable jazz aficionado. In the September 1937 issue of Downbeat, a caption over a picture showing three male musicians and a female singer reads: ‘3 Hep Cats and a Hep Canary.’ If there is any ambiguity as to the compound status of this usage, the first unambiguous compound is found in the 13 March 1938 San Francisco Chronicle. It was not until 1940 that we saw hipcat, meaning the same thing.

This was also the case with hepster and hipster–hepster first appeared in the title of Cab Calloway’s Hepster’s Dictionary, punning no doubt on the rhyme with ‘Webster.’ While the dictionary contained an entry for hep cat, it did not have one for hepster, which suggests that Calloway was simply punning and not using a term then in common usage. Hipster would not appear until 1940, although it would soon outpace hepster in popularity. Both terms referred to a white fan of jazz, and usually of jazz played by black musicians.

Hippie

Next came the early sense of hippie. In the 1950s, hippy or hippie took on a somewhat derisive tone when applied to those who posed as hipsters but were not in fact the genuine article. In A Jazz Lexicon, Robert Gold identifies this use as ‘current since 1945,’ although his first citation is from Night Light by Douglas Wallop (1953); had he looked a little harder, he would have seen it used in George Mandel’s 1952 Flee the Angry Strangers. This is the sense in which Shel Silverstein used hippie in Playboy in September 1960, ‘Then the hippies, they come on cool–they will let me make it if I dig to! Ha!!!!’ And it was in this sense that Orlons sang ‘Where do all the hippies meet?’ in their 1963 number-three Billboard hit ‘South Street’.

The first use of hippie in a new 1960s countercultural/flower child sense came in a series of articles on the evolving Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco by Michael Fallon which began running in the San Francisco Examiner on 5 September 1965. Still using beatnik in the headline, Fallon used hippies, heads, and beatniks interchangeably in the body of the article.

Hip-hop

A tad over a decade later, hip showed up in hip-hop, referring to a subculture that originated in the black and Hispanic youth of America’s inner cities, especially in the South Bronx neighborhood of New York in the late 1970s. The word hip-hop, like many of its slang giant peers, has several claimed parents, but no solid evidence supporting any of the claims. Disco Fever club DJ Lovebug Starski, Afrika Bambaataa of the Universal Zulu Nation, Club 371’s DJ Hollywood, and Keith ‘Cowboy’ Wiggins of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five are all said to have coined the term hip-hop, but proof is scant. The earliest recorded usage found to date is from nine years after DJ Kool Herc began the experiments that produced the art form, in the 1979 song Rapper’s Delight, with ‘Said a hip hop the hibbit the hippidibby hip hip hoppa you don’t stop’. Out of the scat context, the earliest usage is from the 24 February 1979 New Pittsburgh Courier, which reported that D. J. Starksy was “responsible for the derivation of the ‘Hip-Hop.'”

Hipster

Almost a century into its journey through American slang, hip had at least one more life up its sleeve in the form of the new hipster movement, referring to relatively affluent young Bohemians living in gentrifying neighborhoods. It is an opaque term, and one which is generally not used by anyone considered by others to be a hipster. Two profiles of Williamsburg, Brooklyn–ground zero of the contemporary hipster movement–appeared in 2000, and neither used the term hipster. The New York Times used the term bohemians while Time Out New York used the term ‘arty East Village types.’ By the time that Robert Lanham’s The Hipster Handbook was published in 2003, hipster had crept back into the lexicon.

All in all, hip has had a remarkable and unusual slang life. With a few notable exceptions, slang is ephemeral. While there are examples of words that have risen, fallen, and risen again (groovy, sweet, and tasty all come to mind), hip is unique in its ability to navigate 110 years, adding suffixes every few decades to emerge fresh and new. It has been a long and strange trip for hip, and there is nothing to suggest that there won’t be a new hip variant again soon.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Hipsters in Berlin” by Timo Luege. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What is the history of the word ‘hip’? appeared first on OUPblog.

Yeats at 150

Today, 13 June is the 150th anniversary of the birth of William Butler Yeats. The day still resonates because Yeats’s life did not so much terminate as simply enter a new phase upon his death in 1939. In Auden’s famous phrase, he “became his admirers” and was “scattered among a hundred cities.” This is no exaggeration. Witness the extraordinary Yeats-generated energy in Irish poetry, the continuing vibrant presence of the insistently Irish poet throughout Europe and the Americas, the flourishing Yeats societies in Japan and Korea, and the recently announced .

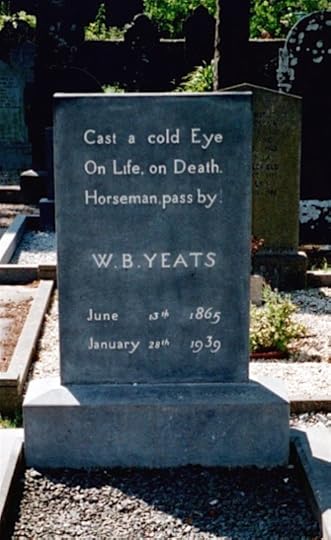

The phenomenon of Yeats’s enduring life resolves the contradiction he posed between perfection of the life and perfection of the work. He is still alive because his work remains vital. He had the magical ability to form words into a living organism that can continue on its own long after the poet’s death. A sense that he would continue to live through his poetry may explain the command in Yeats’s epitaph to cast a cold eye on both life and death. The poetry is what matters, and it transcends the poet’s life and death.

Yeats’s continuing vitality reflects the fact that he was one of those writers Lionel Trilling described as “repositories of the dialectic of their times”. They continue to find readers long after their deaths because they contain “both the yes and the no of their culture” and are thus “prophetic of the future”.

Grave of William Butler Yeats; Drumcliff, Co. Sligo, Ireland by Andrew Balet, CC by 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons

Grave of William Butler Yeats; Drumcliff, Co. Sligo, Ireland by Andrew Balet, CC by 2.5 via Wikimedia CommonsYeats’s poems are still vigorously going about on their own. But the 150th birthday celebration is marred by devastating violence across the globe that seems an eerie validation of the prediction of Yeats’s cyclic theory of history that the era beginning in 2000 would bring an influx of apocalyptic chaos. Current events seem to answer the haunting question at the end of “The Second Coming”: “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?”

War and violence are a part of Yeats’s poetry because they were a part of the dialectic of his times, but the violence of “The Second Coming” is located in the imagination, and poetry itself is intimately involved with violence. Indeed, Wallace Stevens defined the nobility from which poetry arises as “a violence from within that protects from a violence without….the imagination pressing back against the pressure of reality.” Seamus Heaney locates this “redress of poetry” in its use of language, rhyme, rhythm, meter, and stanzaic form to create or suggest an alternative–more noble–reality.

Yeats’s 151st year will provide many occasions to search for a similar element of redress in a poem that will see heavy duty during the centenary of the Easter 1916 rising. “Easter 1916” challenges commemorators of the rising with the assertion that the beauty engendered by rebellion was terrible. Moreover, the poem’s signature Yeatsian question makes room for an alternative reality by interrogating all war: “Was it needless death after all?”

As Yeats’s 150th birthday elides into the 100th anniversary of “Easter 1916”, it is time to read his 1916 poem in the context of his subsequent plea for healing sweetness in “Meditations in Time of Civil War”. In the midst of war’s havoc, Yeats notices bees building near an empty stare’s nest in the crevices of his tower. Lamenting that ‘We had fed the heart on fantasies, / The heart’s grown brutal from the fare”, he prays: “O honey-bees, / Come build in the empty house of the stare.” If we see the ‘terrible beauty” of 1916 as a step toward honey bees building in the empty house of the stare, the combination of these two iconic poems fulfills the promise of Yeats’s 1901 declaration that “the end of art is peace.” Seamus Heaney’s adoption of this same phrase in “The Harvest Bow” is another reminder that Yeats at 150 is alive and well.

Featured image credit: Letter written from William Butler Yeats at Ballinamantan House, Co. Galway, Ireland, to Ezra Pound, 15 July 1918. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Yeats at 150 appeared first on OUPblog.

A Magna Carta reading list

“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land”

—Clause 39 of the Magna Carta

King John II of England ascended to the throne in 1199 after a tumultuous accession war with his nephew, Arthur of Brittany, and Arthur’s ally Phillip II of France. King John inherited the Angevin Empire, consisting of England, most of Wales and Ireland, and a large swathe of France stretching south to Toulouse and Aquitaine. Yet this empire was crumbling. It is in this context that one of the greatest legal documents in the world was written. The Magna Carta was intended to guarantee the rights of several rebellious barons, but its repercussions stretch to modern discussions of rights, representation, and power.

As we approach the 800th anniversary, we’ve gathered resources from across Oxford University Press, a brief selection of which are offered below.

The Magna Carta on Oxford Constitutional Law

The Magna Carta is a cornerstone of law and liberty in Western society. Rights that many often take for granted today originated with that ink and paper. For example, clauses 20 and 21 stipulate that punishment meted out to criminals should only be in proportion to the original offence. As a whole, the Magna Carta document also provides a fascinating insight into the seemingly-obscure gripes and grievances suffered by the English 800 years ago. Clause 23, for example, states that nobody should be forced to build a bridge over a river.

The Magna Carta key players on Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online

The people who make up the story of the Magna Carta are a diverse and eccentric cast. King John II – who squeezed as much money out of England as he could, and made numerous enemies in the process – is well known. Robert Fitzwalter, the leader of the rebellious barons, and the scholarly Archbishop Stephen Langton, who was “probably the mind responsible for the attempt to set down in writing what the barons wanted,” played vital roles in the signing of the historic document.

‘The Rebellion’ in The Northerners: A Study in the Reign of King John

What led a handful of barons in Northern England to take up arms against the English monarch? And how was it that this rebellion took John almost completely by surprise? This chapter paints a fascinating picture of the run-up to the now-famous rebellion, the ensuing skirmishes, and how the barons eventually succeeded in getting King John into the negotiations which would lead to his signing of the Magna Carta at Runnymede.

‘The Enforcers of the Magna Carta’ on Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online

“Many were … united in a deep hatred of John, and all in their resolution to resist him by force if need be.” Who exactly were the barons who stood united behind Robert Fitzwalter? This essay brings to life the key players from within the rebel faction who were trusted with the enforcement of the terms of the Magna Carta, for, as any lawyer will tell you, it is one thing to pass a law, but quite another to enforce it.

‘Magna Carta’ in The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Legal History

Copied painstakingly by hand in the last quarter of the thirteenth century into manuscripts and statutes across England, the Magna Carta is the earliest-known legislative text cited by English common law professionals. Here, the history of the document is traced, including how various amendments were added and clauses taken away, and how it became an integral part of the country’s legal culture.

‘The Evolution of Constitutional Monarchy’ in The Monarchy and the Constitution

The English monarchy is one of the world’s oldest constitutional monarchies and Vernon Bogdanor traces the evolution of this 1000-year-old institution, taking into account the influence of the Magna Carta, the Bill of Rights, and the monarchy under Queen Victoria.

‘Magna Carta’ in Shaping the Common Law: From Glanvill to Hale, 1188-1688

The United States has perhaps the most famous constitution in the world of any modern nation, and Magna Carta has had a profound influence on the American legal and constitutional tradition. So much so, in fact, that the Kennedy Foundation opened a memorial at Runnymede celebrating the debt America owes to the document. In this chapter, the fascinating journey of England’s arguably most-important export in America is told – from the English colonies to the seat of American government.

What resources do you recommend for learning more about this historic document? Let us know in the comments below.

Featured image: King John of England, 1167-1216. Illuminated manuscript, De Rege Johanne, 1300-1400. MS Cott. Claud DII, folio 116, British Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A Magna Carta reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Ludwig Wittgenstein

This June, the OUP Philosophy team are proud to announce that Ludwig Wittgenstein is their Philosopher of the Month. Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein (26 April 1889 – 29 April 1951) was an Austrian-born philosopher and logician, regarded by many as the greatest philosopher of the 20th century for his masterpieces: Tractatus logico-philosophicus (1921) and the posthumous Philosophical Investigations (1953).

Wittgenstein was born the youngest of eight children into a wealthy industrial family in Vienna, Austria. He intended on studying aeronautical engineering, but his interest in the philosophy of mathematics led him to the University of Cambridge where he studied under Bertrand Russell. Wittgenstein and Russell developed a strong relationship, and Russell recognized Wittgenstein’s genius and encouraged him to pursue philosophy and the foundations of logic. After returning to Austria in 1913, Wittgenstein joined the Austrian army during the First World War (1914-1918) and became a prisoner of war. While prisoner, he managed to draft his first important work, Tractatus logico-philosophicus, and send his manuscript to Russell. He became a naturalized British citizen in 1938 and lectured at the University of Cambridge until 1947. Wittgenstein spent his remaining years writing. His last words were, ‘Tell them I’ve had a wonderful life.’

In addition to the Tractatus and Philosophical Investigations, collections of Wittgenstein’s work published posthumously include Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics (1956), The Blue and Brown Books (1958), Notebooks 1914–1916 (1961), Philosophische Bemerkungen (1964), Zettel (1967), and On Certainty (1969). You can discover more about the life of Ludwig Wittgenstein via the timeline below:

Keep a look out for #PhilosopherOTM across social media and follow @OUPPhilosophy on Twitter for more Philosopher of the Month content.

Featured image credit: “Cambridge-Architecture-Monument”, by blizniak. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Philosopher of the month: Ludwig Wittgenstein appeared first on OUPblog.

June 12, 2015

Celebrating pride through oral history

In recognition of Pride Month, we’re looking at some of the many oral history projects focused on preserving the memories of LGBTQ communities. The LGBTQ Oral History Digital Collaboratory is connecting archives across North America to produce a digital hub for the research and study of LGBTQ oral histories. The University of Chicago is cataloguing the history of students, faculty, and alumni for its “Closeted/Out in the Quadrangles” project. The University of Wisconsin – Madison continues to collect the histories of Madison’s LGBT Community, and has even prepared mini-movies to make the materials more accessible.

The current issue of the Oral History Review includes reviews of two recent projects that offer innovative uses of oral histories to tell the stories of LGBTQ communities. Lindsay Hager offers an in depth review of the 2012 documentary United in Anger: A History of ACT UP. The documentary chronicles the development of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), relying extensively on the materials preserved in the Act Up Oral History Project. Hager’s review is accessible in the current issue of the Oral History Review.

Liam Lair offers a review of Steel Closets: Voices of Gay, Lesbian, and Transgender Steelworkers by Anne Balay. Lair puts the book into the context of the current “it gets better” narrative, suggesting the world looks very different from the position of working class LGBTQ communities and communities of color. Drawing on extensive oral histories with working class LGBTQ individuals, the book offers a critical contextualization of the progress currently shaping discourses around LGBTQ communities. Lair’s review of Steel Closets can be read in the current issue of Oral History Review, while the book is available for purchase.

And now for something completely different…

Registration recently opened up for the 2015 Oral History Association Annual Meeting in Tampa! You’ve got until August to register for early bird pricing, so make sure you get your tickets ASAP.

We’d love to hear about other LGBTQ focused oral history projects. Chime into the discussion by commenting below or on the Oral History Review Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, and G+ pages.

Image Credit: “2012 06 09 – 0708 – DC – Capital Pride Parade” by Bossi. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Celebrating pride through oral history appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers