Oxford University Press's Blog, page 652

June 19, 2015

For refugees, actions speak louder than words

Syria. The Mediterranean. The Andaman Sea. Yet again, the plight of refugees features prominently in news headlines. Images of boat-loads of individuals seeking asylum or masses of humanity surviving in camps, like Za’atari in Jordan, have led to calls for more to be done to respond to the plight of refugees. These calls will likely intensify as we get closer to 20 June, World Refugee Day, when groups in more than 100 countries will host events and issue reports to increase awareness about the needs of refugees and to mobilize a more effective response.

But this is not the first World Refugee Day, and the crises we see today are not the first refugee crises. Indeed, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) was created by the Member States of the United Nations in 1950 with a mandate to ensure the protection of refugees and find a solution to their plight. For more than 60 years, this UN agency has worked with governments and other partners to try to respond to the needs of refugees. Today, UNHCR works in 123 countries around the world to help refugees, the internally displaced and stateless persons. It is a massive task.

One way that UNHCR and states try to respond to particular challenges faced by the forcibly displaced is to develop new policies. Many of these policies are global as they are meant to guide the actions of UNHCR and states around the world. In recent years, for example, global policies have been adopted on promoting alternatives to refugee camps, mainstreaming issues of age, gender, and diversity into UNHCR’s activities, promoting protection for refugees in urban areas, responding to the needs of refugees with disabilities, and encouraging solutions for protracted refugee situations. The announcement of each new policy brings with it considerable hope that at least one challenge faced by refugees can, and will, be resolved. This hope may explain why UNHCR, governments and other groups invest considerable time and resources in the policy-making process.

But do these policies make a difference? Too often, they do not. Despite agreement on a policy to respond to protracted refugee situations, two-thirds of the world’s refugees still spend five or more years in exile, and the average duration of a refugee situation is approaching 20 years. Despite agreement on a policy to pursue alternatives to camps, a significant number of refugee-hosting states require refugees to remain in closed camps, denied the right to support themselves and their families through paid work and self-reliance. And despite the existence of a policy since 1985 on the need to rescue asylum-seekers in distress at sea, thousands of people continue to perish in the Mediterranean in their pursuit of asylum in Europe.

How do we understand the apparent gap between the claims of these global policies and the realities for refugees today? This question has motivated a new research focus on the making, implementation and evaluation of global refugee policy. A more critical and systematic engagement with the global refugee policy process reveals the range of factors and interest that guide the making of policy and often limit its implementation. Indeed, our understanding of the global refugee policy process can borrow many lessons from the broader study of global public policy, and its understanding of the tensions and struggles inherent in so many efforts to make global policies and implement these policies in regional, national, and local contexts.

For example, the case of negotiating a global policy on children at risk shows how the making of policy is not always a technical and consensual process, but can be a highly contested and political. Likewise, the implementation of global policies in local contexts is far from inevitable, but may be limited and frustrated by domestic politics in refugee-hosting countries, like Tanzania, or the influence of actors in local contexts that are not bound by global policies, as seen in Southern Africa.

At the same time, however, a more careful understanding of global refugee policy may identify those instances when global policies do matter, especially where they can place limits on the otherwise restrictive policies and practices of states. For example, the standards of global policy have arguably been used to challenge the non-entrée policies of European states and promote refugee protection standards in the Asia-Pacific region.

Many of these themes were further explored in a recent seminar series at the Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford. Presentations considered the meaning of global refugee policy, the process by which certain global policies, such as UNHCR’s policy on urban refugees, may be changed, how the views of those outside the formal policy process may influence the development of new policy, and the case of global policy on internal displacement highlights the tensions and complexities of the policy process itself.

Together, this work encourages us to think more critically and systematically about the process by which global refugee policy is made, and the interests and factors that affect its implementation. These policies claim to be able to address the many problems faced by refugees today, yet they so often fall short on this promise. We need to develop a better understanding of why this happens and how the words of global refugee policy can be more predictably translated into action.

On World Refugee Day, and every day, actions to help the world’s refugees will speak louder than words.

Headline image credit: World Concept. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post For refugees, actions speak louder than words appeared first on OUPblog.

Just a face in the crowd

The widespread practice of uploading photographs onto Internet social networking and commercial sites has converged with advances in face recognition technologies to create a situation where an individual can no longer be just a face in the crowd. Despite the intrusive potential of face recognition technologies (FRT), the unauthorised application of such technologies to online digital images so as to obtain identity information is neither specifically prohibited nor a critical part of the international law reform discourse. A compelling issue facing nations around the world is hence how to respond to this evolved digital landscape and properly govern the use of face recognition technologies so as to protect the privacy of its citizens.

To address this issue of the proper governance of face recognition technologies, it is perhaps useful to begin by considering how modern digital communications have undermined the traditional philosophical paradigm of privacy law. Traditionally, privacy laws were conceived to protect a vulnerable observed from a powerful observer, reflected in the entrenching of the Big Brother motif in contemporary culture. Yet in the digital realm, as has been noted in the literature, entities are simultaneously the observed and the observer, intruding upon the privacy of others even as their own privacy is violated. Further, whilst our present laws largely seek to protect privacy by controlling the flow of information, by imposing duties and responsibilities on those who receive, transmit and store such information, the rapid and widespread electronic dissemination of information is increasingly making illusory such attempts at control. In such a changed landscape, a new objective for privacy laws is perhaps to curtail the intrusive impact of FRT by creating protected or safe spaces for the exchange of information. Finally, it is relevant to address changing societal conventions as to digital privacy. It is often said that digital natives, those who played on the Internet whilst playing Sesame Street, have a different conception of privacy to digital immigrants, those who transitioned to the Internet during their adult life. Whilst this may be somewhat of a simplification, in designing a regulatory framework for FRT it is still useful to examine to what extent such changing norms have undermined the traditional public policy basis of privacy laws.

When a new technology emerges, it is often tempting to focus on the particular social harms and problems generated by the technology and to invent a whole new governance framework. Such an approach, as we have seen in other areas such as digital copyright law, commonly leads to a mosaic-like regulatory framework, where each piece of law retains its beauty and integrity but forms a fragmented whole. A better approach might perhaps be to analyse the operation and effect of the new technology, identify analogous technologies which are the already the subject of mature laws, and then use these established laws to guide the governance of the new technology. In this way, we can ensure that our laws move forward as a coherent and consistent whole, with new and emerging technologies being systematically encompassed within a broader overarching governance framework.

Adopting such an analogous-technology approach, we can perhaps glean some insights for the future regulation of face recognition technologies from existing regulation of telecommunications and access (TIA). TIA laws essentially govern the use of listening devices and interception technologies that can be used to de-privatise what would otherwise be private information. TIA laws do so, not through provisions aimed at controlling the data flow, but rather through the regulation of the use of the technology to create, in effect, protected spaces on telecommunications networks. Whilst TIA laws admittedly relate to the exercise of investigative powers by public law enforcement officers, and FRT laws will have to encompass both relations between private entities and relations between the state (public law enforcement) and individuals, the structure and design of TIA laws can instruct the design of FRT laws on such complex issues as what constitutes valid consent, the relevance of the distinction between public and private communications, and the nature and ambit of permissible exceptions to laws prohibiting the use of FRT.

Integrating and analysing these and other considerations to formulate a nuanced and comprehensive governance framework for face recognition technologies is a complex undertaking. Whilst the Australian Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) governs the collection, use, storage, and disclosure of personal information about individuals, Australia, unlike the EU, does not have specific data protection laws.

In the EU, data protection laws (EU Directive 1995/46/EC and its national implementation) applying to private entities will have to respect principles such as informed consent (although other justifications might be applicable), purpose limitation, and data minimisation. In the current age, questions arise as to the meaning of these principles in the age of Big Data as is reflected in the current debates about the general EU Data Protection Regulation which will replace the 1995 Directive.

Big data and face recognition technologies raise the question of whether consent is a meaningful justification for the processing of facial recognition data. The user is by definition unsure what he or she is consenting to. Consent to publication and republication of a photo on another profile, for example, is one thing, but aggregating information across the Internet and re-identifying individuals through face recognition technology from a single tagged photo goes much further and beyond the imagination of the average user. Powerful FRT means that users cannot foresee how and by whom their personal identifying information will be used, hence the limits of consent to justify such processing. Interception by law enforcement is and probably has to be clandestine. FRT is also clandestine in the sense that it leads to unexpected outcomes of re-identification. Hence users are in need of protected, private spaces where FRT cannot be used.

Featured image: Photo montage by geralt. CC0 via pixabay.

The post Just a face in the crowd appeared first on OUPblog.

The Jurassic world of … dinosaurs?

The latest incarnation (I chose that word advisedly!) of the Jurassic Park franchise has been breaking box-office records and garnering mixed reviews from the critics. On the positive side the film is regarded as scary, entertaining, and a bit comedic at times (isn’t that what most movies are supposed to be?). On the negative side the plot is described as rather ‘thin’, the human characters two-dimensional, and the scientific content (prehistoric animals) unreliable, inaccurate, or lacking entirely in credibility.

Within the paleontological community, there have been a few voices criticising the appearance of some of the CGI dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures. For example, the velociraptor is too large, and they do not show the raptors with feathers or at least a ‘shaggy’ filamentous covering. Their hands and claws are also not articulated correctly. The mosasaur is too big (not strictly true, as some mosasaur fossils are very large!), and the pterosaurs are seen eating the wrong sorts of organisms altogether! Quite a few of these technical criticisms reflect the fact that paleontological research has made advances in the two decades and more since the first Jurassic Park movie appeared on our screens.

So, why are the ‘dinosaurs’ so inaccurate? I listened with considerable interest to an interview in the run-up to the launch of the movie, by a friend and colleague Jack Horner (a genuine dinosaur palaeontologist from the Museum of the Rockies in Montana who acted as an advisor to the Jurassic World production team). In the face of these criticisms his basic point was that Jurassic World was entertainment and in the final analysis it was “… just a movie”. It was never intended to be a documentary about the scientific basis of our understanding of prehistoric life. Of course he was able to advise the animators on the most likely posture and style of movement displayed by the CGI movie stars so that they look as life-like as possible. Jack was naturally concerned about the absence of filaments and/or feathers on some of the dinosaurs, but from an editorial perspective there was an over-riding need to maintain some continuity in appearance of the animals seen by audiences in previous movies: the raptors had to look like the raptors of the original Jurassic Park. And that simple and essentially pragmatic acceptance (the need for continuity) underplates the awful dilemma faced by any ‘expert/consultant’ hired by the production team of a multimillion dollar enterprise such as Jurassic World.

The priorities of the movie makers with regard to narrative and appearance will always outweigh the science-based accuracy desired by the advisor. In such circumstances, commercial ‘reality’ always trumps scientific realism. All any advisor can hope for is that the film makers don’t take too many liberties with the animals and how they are portrayed (thereby avoiding some of the scorn of peers) and that there might be some financial benefit from any success at the box-office that can result in genuine paleontological research as a very desirable spin-off. Even small amounts of money (by movie-industry standards) can be enormously beneficial for real scientific research programmes. So are there any other benefits that accrue from movies about dinosaurs?

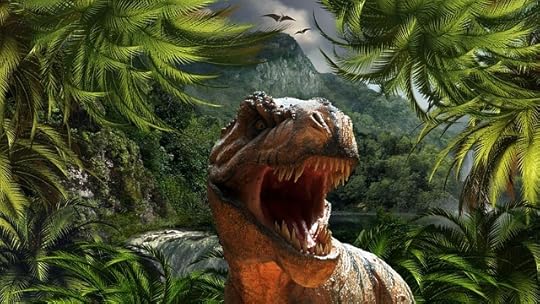

Tyrannosaurus Rex, the “King Lizard”, is perhaps the best known of the Jurassic Dinosaurs (Image: Public Domain via Pixabay)

Tyrannosaurus Rex, the “King Lizard”, is perhaps the best known of the Jurassic Dinosaurs (Image: Public Domain via Pixabay)There is little doubt that the first Jurassic Park had a beneficial impact on the public interest in dinosaurs. I went to see that film and still remember the thrill of that first glimpse of the incredibly realistic CGI brachiosaur browsing on a tree. I was mightily impressed (even if I didn’t like the way it reared up on this hind legs!). Children and students were inspired by such visions and wanted to know more, museums were inundated with visitors and the challenge was to use the interest to tell visitors more about the scientific study of such ancient creatures. Michael Crichton’s original plot-line of Jurassic Park linked the then comparatively new biotechnological developments (DNA amplification using PCR) with the neat twist of being able to extract dinosaur blood cells (and of course DNA) preserved in the stomachs of blood-sucking insects. Believe it or not, the publicity surrounding that film actually facilitated a number of lines of research into biomolecule preservation in ancient fossil animals. This research was not motivated by the prospect of bringing dinosaurs back to life, but as a chance to investigate the evidence of some biomolecules (or fragments thereof) being preserved in fossils that were 10s of millions of years old (if the conditions of preservation were just right). Counter to the scientific expectation of the time (biomolecules could not possibly survive for millions of years) some remnants have indeed been found.

But where are we now, I wonder? Jurassic World seems to me to represent a progressive and I believe unavoidable drift toward entertainment at the expense of scientific credibility. We are now in the realm of the imaginary dinosaur (prehistoric monster) funfair disaster movie and lightweight morality tale. At best it perhaps conjures up that old aphorism about our tampering with ecology (our biosphere) at our peril. Beyond that, palaeontologists should either stay at home or do like everyone else: switch off brain, sit back with a bag of popcorn, and enjoy the show. As Jack Horner said: “it’s just a movie”!

Featured image credit: “Velociraptor” by sgtfury. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The Jurassic world of … dinosaurs? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 18, 2015

Ramadan and remembrance

Ramadan is an important time for Muslims, whether they live in New York City, Tehran, Cairo, or Jakarta. While there is great diversity in Islam, for most Muslims this month reflects an intensification of the religious devotion and contemplation that characterizes many Islamic traditions from prayer (salat) to pilgrimage (hajj/ziyarat).

Ramadan is structured around food, a lack of food, and prayer—the early meal before dawn, the fasting during daylight, the meal at the end of the day, and the daily prayers. Sunni Muslims pray five times a day and often perform extra prayers (tarawih) during the month of fasting. Shi’a generally pray three times a day and typically do not perform these extra prayers, although this is somewhat dependent on their sectarian identity (Twelver/Ithna Ashariyya, Sevener/Ismaili, Zaydi, Alevi, to name some). Shi’a Muslims have extra supplications throughout the year that are continued during Ramadan, such as Du’a Tawassul, a supplication that appeals to the Imamate for guidance and protection.

Readings from Islam’s revelatory text make this month particularly important, as many Muslims read the entire Qur’an over the month of fasting. The attention given to the Qur’an reflects the belief that the Prophet Muhammad first received the revelations through the Angel Gabriel (Jibril) during the month of Ramadan. Ramadan is looked at as an especially holy time, reflected in such traditions as Prophet Muhammad’s statement,“When Ramadan begins, the gates of heaven open, the gates of hell close, and demons are chained.”

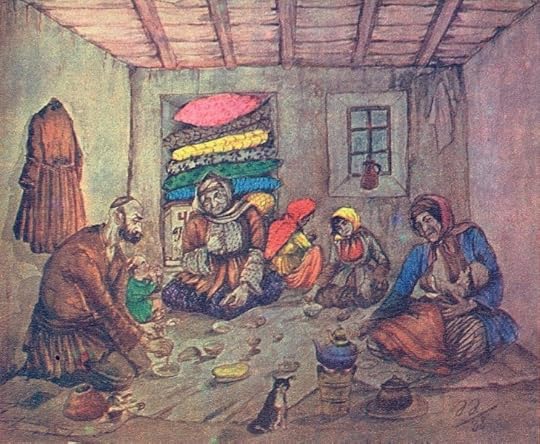

“Ramazan with the poor” by Azim Azimzade. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Ramazan with the poor” by Azim Azimzade. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Ramadan is neither a duty nor a series of rituals and performances. At its core lie important theological beliefs about suffering, redemption, and hope that revolve around the idea of dhikr, or the remembrance of Allah. Ramadan is about remembering God through a disciplining of the body, mind, and heart that asks Muslims to reflect on the less fortunate—the poor, the hungry, those thirsty for water. These thoughts cross one’s mind naturally. When one is hungry, one thinks of the poor and starving. When one is thirsty, one cannot help but think of all those in the world who are without safe, potable water.

During the month of Ramadan, Muslims typically abstain from food, water, bad speech, sexual intercourse, and malicious behavior during the daylight hours. Islam’s emphasis on mercy and compassion is evident in the many exceptions made for those who are not required to fast—menstruating, pregnant, and breastfeeding women, those with medical conditions, individuals who are ill. Ramadan’s emphasis is thought to be on the dietary fast, or the abstaining from food and water during daylight, but even this practice is intended to purify the heart. According to Rumi,“Shari’ah is just theoretical knowledge.” It is only when these rituals train the heart that one comes to know Allah. One knows Allah through remembrance, an important theme in the Qur’an:

“Remember your Lord over and over; exalt Him at daybreak and in the dark of night.” 3:40

“When you are not in prayer, remember God standing and sitting and lying down.” 4:103

“Remember the Lord in your heart, humbly with awe and without utterance, at dawn and at dark, and be not amongst the neglectful.” 7:205

“The hearts of those who believe are set at rest by God’s remembrance, indeed, by God’s remembrance (only) are hearts set at rest.” 13:28

Ramadan is a time of the year during which the forgetfulness that builds up in one’s heart is remedied through prayer, and bodily and spiritual fasting, all of which are practices directed toward remembrance. This month is one in which religious contemplation retrains the heart and the body for the coming months, establishing a cycle that is mnemonic, restorative, and deeply spiritual.

Image Credit: “Ramadan.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Ramadan and remembrance appeared first on OUPblog.

Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Pipe Dream

The seventh of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s stage works, Pipe Dream came along at a particularly vulnerable time in their partnership. After the revolutionary Oklahoma! (1943) and Carousel (1945)—with, above all, two of the most remarkable scores ever heard to that point—they disappointed many with Allegro (1947), eventually revealed to be intensely influential as the first “concept musical,” but built around a strangely deconstructed score using bits and pieces and giving the leads too little to sing, the musical equivalent of Pixy Stix.

Rodgers and Hammerstein shows were supposed to produce great cast albums. Oklahoma!’s 78s moved past a wonderful overture on side one to “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” on the next disc, “The Surrey With the Fringe On Top” right after that, and so on—twelve cuts of absolutely first-rate music theatre, its characters jumping out of the speakers at you. Just to hear Alfred Drake’s Curly conjuring up the experience of a surrey ride expanded the American musical’s horizons after years of “The Best Things in Life Are Free” and “Easter Parade.” Anybody could sing those songs, but only this particular cowboy—braggy and full of himself yet hiding a fierce tenderness for his sweetheart—was right for “Surrey.”

Allegro’s cast album sold so poorly that it wasn’t transcribed to LP till a generation later. Then came South Pacific (1949) and The King and I (1951), Rodgers and Hammerstein back in form with character-rich scores. However, another setback followed. Me and Juliet (1953) by any other team would have satisfied as a backstager with fabulous scenery and a ton of dancing, completely devoid of generic cliché. Unfortunately, it was devoid of everything else, too, with a lot of principals but no interesting conflict—Oklahoma!’s cold war of landowners (the farmers) and laborers (the cowmen), for instance, or The King and I’s battle to the death between two egomaniacs. Me and Juliet’s score was no better than agreeable; here was another cast album that didn’t sell.

So Rodgers and Hammerstein were right back where they had been after Allegro, and the team needed to reaffirm the brand with another of their great “musical plays,” an Oklahoma! or so. However, it was the 1940s that hosted their serious works. In the 1950s, they were doing musical comedy, a less highly strung format, with none of those angsty musical scenes or soliloquies that tear the heart open. After The King and I, Rodgers and Hammerstein wrote in a more direct communication style. You know… songs.

And that’s when Pipe Dream happened along, breaking one of the creative world’s primary rules: don’t make art with your friends. Rodgers and Hammerstein were personally close to novelist John Steinbeck and his wife, Elaine (who had been a stage manager on Oklahoma!), and someone thought it would be fun for Rodgers and Hammerstein to do a Steinbeck musical. But the complex alchemy of writing and putting on a big show is very demanding on everybody’s ego. There will be criticism, blaming, and good old-fashioned screaming. You can make art with people you respect, but not with people you like, because you will need to hurt their feelings.

But then, Pipe Dream didn’t start with Rodgers and Hammerstein and the Steinbecks. It was originally a project for Frank Loesser with producers Cy Feuer and Ernest Martin, because all three had presented Broadway with Guys and Dolls, and Steinbeck’s fiction, set in northern California among society’s outlaws and the women who love them, seemed to promise another smash hit of the same kind.

Then Loesser drifted away; Rodgers and Hammerstein got involved (and bought Feuer and Martin out for a percentage); Steinbeck, who was supposed to write a libretto based on the storyline of his novel Cannery Row, announced that he didn’t want to write a libretto; and anyway, Cannery Row didn’t have a storyline–it was an atmosphere piece.

Guy Raymond (George Herman), Annabelle Gold (Sonya), Keith Kaldenberg (Red), Nicolas Orloff (Dizzy), Don Weissmuller (Slim), Mike Kellin (Hazel), G.D. Wallace (Mac), Gene Kevin (Slick), Jenny Workman (Kitty), Hobe Streiford (Whitey) and Warren Kemmerling (Eddie) in Pipe Dream (1955). Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Guy Raymond (George Herman), Annabelle Gold (Sonya), Keith Kaldenberg (Red), Nicolas Orloff (Dizzy), Don Weissmuller (Slim), Mike Kellin (Hazel), G.D. Wallace (Mac), Gene Kevin (Slick), Jenny Workman (Kitty), Hobe Streiford (Whitey) and Warren Kemmerling (Eddie) in Pipe Dream (1955). Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections.Instead, Steinbeck wrote a novel, Sweet Thursday, set in Cannery Row and inventing what every musical needs, a love plot. This one united two Steinbeckian winner-losers (that is, interesting people who for neurotic reasons aren’t having interesting lives). Doc, a marine biologist, is loafing his days away with scientific busy work, and Suzy is a vagrant who fronts her vulnerability with dangerous anger. But musicals do love odd couples, from Naughty Marietta to Marie Christine.

So Hammerstein turned Sweet Thursday into a libretto, Rodgers and Hammerstein gave it lift and emotion with their fifties-style musical-comedy numbers, and they renamed it Pipe Dream because at one point Suzy takes up residence inside a boiler pipe. (Yes, really.) The show marked a departure from Rodgers and Hammerstein because of the wastrels and bordello girls in the narrative. Yet it was typical Rodgers and Hammerstein as well. It had a strong sense of community (as with Carousel’s fisherfolk and South Pacific’s seabees). It made room for an opera soprano, Helen Traubel, as the bordello madam (because Rodgers vastly preferred singers who act to actors who sing; most Rodgers and Hammerstein productions had sopranos or mezzos in at least one role). It lacked high-fashion choreography (which had given South Pacific an extra shot of realism). There was also the offbeat nature of the show as a whole (as every Rodgers and Hammerstein project had been offbeat except Me and Juliet).

So far, so good, but Pipe Dream did not work. Some blame Helen Traubel, though, as we can see in MGM’s Sigmund Romberg bio, Deep In My Heart, she was a performer of warmth and power, exactly what her part needed. She may have been on the stately side, though, and the musical as a form needs vitality from its stars.

Some feel Rodgers and Hammerstein had trouble getting into Steinbeck’s earthy worldview. They didn’t exactly tiptoe around it; some of the scenes were set inside the bordello. And early on, Doc’s latest one-night-stand, Millicent, feeling ignored by Doc, assumed that his pal—a man named Hazel—was Doc’s boyfriend. “Maybe that explains the whole thing!” she cried, angrily, as she left. It’s a very advanced moment for a musical of 1955.

Nonetheless, there was the feeling that Pipe Dream ended up a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical but not a Steinbeck musical, and I think I know why, because some years ago in London I gave a speech introducing a staged concert of Pipe Dream. Then, home again, I did exactly the same thing way uptown, in a theatre so far to Manhattan’s northeast that it should have been under water. The English had enjoyed my improvisational talk well enough, but I decided to prepare the second talk, so I opened with the first lines of Cannery Row, in which Steinbeck describes his setting as “a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream…Its inhabitants are, as the man once said, “’whores, pimps, gamblers, and sons of bitches,’ by which he means Everybody.”

I quoted these lines to emphasize that Steinbeck’s world is writerly and paradoxical and above all anarchic. It’s everything going off at once yet nothing ever happens—and musicals are about people who make things happen. For instance a belle vamps the football hero so he’ll play for the home team and win the big game. (That’s Leave It To Jane.) Or a sinner blows his money on the temptress known as Miss Georgia Brown and, she, feeling religion coming on, gives it away to the church so he gets into heaven after all. (That’s Cabin in the Sky.)

Thus, Pipe Dream couldn’t have worked, because its characters resist the musical—especially the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, which is orderly to a fault. Cannery Row is disorderly, so when Pipe Dream’s people are running around trying to fix Doc and Suzy up, it’s not natural, because it overturns the authentic Cannery Row environment. The show really needed lazy songs, pointless songs, songs that sneak up on you and then wander away; but what kind of musical is that?

“William Johnson (Doc) and Judy Tyler (Suzy) in Pipe Dream” (1955) Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

“William Johnson (Doc) and Judy Tyler (Suzy) in Pipe Dream” (1955) Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections.True, the score is wonderful as sheer music, and some of the character numbers work well. Suzy’s “Everybody’s Got a Home But Me” catches her strength and wistfulness at once, and Hazel’s “Thinkin’” is properly goofy. Doc sounds the forgiving Steinbeckian philosophy in “All Kinds Of People.” But “How Long?,” a choral number when Cannery Row is heartening Doc up in his courtship of Suzy, is too darn organized. It has a terrific vocal arrangement, which eventually reaches six-voice harmony, but it misrepresents Cannery Row. The inhabitants don’t spend their time heartening anyone, and, frankly, these people are not in harmony with each other or anything else. Remember, Cannery Row is a stink, a grating noise, a dream. It’s eternally inconclusive, and if there’s anything a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical is, it’s conclusive. Every song finishes off a scene, an idea, a hope.

So that’s what I said in my New York speech before a performance of Pipe Dream, and the whole time I was talking I saw the audience glaring at me in fury. They didn’t want a speech. They wanted the show to start.

I bring this up now because there was a thread recently on one of the Broadway sites on this very matter, as theatre buffs, trolls, and the usual “me, too” schmengies discussed whether or not managers of small theatre companies should program an address before a performance. Are they imparting information we need to have? Or are they just showing off before a captive audience?

I was especially taken with one post, recalling an organization in San Francisco that gave an annual luncheon that was ruined for several years by a co-chair who, at the very end when people wanted to leave, would launch into a ramble through whatever was on his mind, including pauses during which he would grin while slowly reaching for his next paragraph. The poster called it “insufferable.” The second year the co-chair did this, some folks got up and left while he talked, and though the facing bench told him to mind the light (as they put it in Quaker meetings), he kept on giving his insufferable talk till he was removed from his co-chairmanship.

Now, why did he do this? Was the occult pleasure of controlling the room enough to outweigh the disadvantage of appearing selfish and needy? And are speeches a bad idea altogether? Because the one I gave before that little New York Pipe Dream sure was.

I didn’t take part in that online thread, but I’m posting now. I think these little-theatre organizations have to decide whether they lean toward Broadway or the church-basement bake sale. The former is professional, sophisticated, polished. The latter observes clubhouse manners, rustic and informal. Both attitudes are viable; it’s simply a matter of fixing your ID in one tone or the other. If you want respect, omit the speech and start the overture. If you want the relaxed air of friends getting together, keep the speech. But if the audience is glaring at you while you give it, it may be that you and your public have incongruent agendas.

And don’t make art with your friends.

The post Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Pipe Dream appeared first on OUPblog.

Six people who helped make ancient Naples great

The city that we now call Naples began life in the seventh century BC, when Euboean colonists from the town of Cumae founded a small settlement on the rocky headland of Pizzofalcone. This settlement was christened ‘Parthenope’ after the mythical siren whose corpse had supposedly been discovered there, but it soon became known as Palaepolis (‘Old City’), after a Neapolis (‘New City’) was founded close by. These twin cities – both of which are now absorbed into the fabric of modern Naples – were home to some of the most beguiling mythological and historical characters in classical antiquity. Here are just six of them.

Parthenope

Originally this half-bird creature roamed the Campanian coast with her siren sisters, chanting melodies that were sweet – but deadly. Homer tells us that any sailor who came too near to the sirens would “never again be welcomed home by his wife and children”, and describes the piles of bones covered in rotting flesh that decorated the sirens’ lair. Odysseus managed to escape this fate by stuffing his crew members’ ears with wax. He left his own ears unplugged but tied himself to the ship’s mast, which enabled him to hear the song but resist the seduction. Parthenope was distraught and threw herself in the sea. When her drowned body washed up on the shore, some Greek sailors built her a tomb which became the focus for commemorative games and a mysterious torch race.

![Detail of the Fountain of the Spinacorona by Little john via Wikimedia Commons [public domain].](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1434646227i/15247822.jpg) Spinacorona by Little john. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Spinacorona by Little john. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.After antiquity, Parthenope was hailed as a protectress and symbol of Naples. One sixteenth-century fountain shows her standing in the crater of Vesuvius, holding her breasts in her hands as two streams of water spurt out of her nipples to quench the volcano’s superheated flow. A more gruesome image is found in Curzio Malaparte’s 1949 novel La Pelle (‘The Skin’), by which time it had become customary to represent the sirens as mermaids. In the film adaptation of the novel, we see the small, childlike body of what appears to be a siren served up at a banquet for some contemptuous foreign dignitaries – a clear allegory for the city’s decline during and after the Second World War (and enough to put you off fish forever).

Virgil

The Roman poet Virgil was buried in Naples, making the city an eternal place of pilgrimage for other poets and artists. Petrarch, Dante, and Mozart are some of the more famous tourists to have visited the site of Virgil’s tomb on the hill of Posilippo, although it’s unlikely that this modest columbarium tomb really contains the great poet’s body (that was simply wishful thinking on the part of Petrarch). Another set of medieval stories turned Virgil into a sorcerer, whose masterpiece was an egg with the power to keep Naples safe for as long as its shell stayed intact. This egg was hidden inside the Castle that still bears its name – the ‘Castel dell’Ovo’, on the tiny island of Megaride across from Via Parthenope on the mainland.

Lucius Cocceius Auctus

Lucius Cocceius Auctus was an Augustan architect renowned for building two enormous tunnels through the Neapolitan subsoil, known today as the Crypta Neapolitana and the Grotta di Seiano. The geographer, Strabo, thought that Cocceius must have taken inspiration from ancient stories of the Cimmerri, a mythical race of people said to live underground in a network of tunnels around the nearby Lake Avernus. Whatever his source, Cocceius’ subterranean creations soon became central to Naples’ urban identity and would themselves go on to inspire some highly atmospheric literary descriptions – as well as a set of colourful medieval legends.

![Crypta Neapolitana by Mentnafunangann [CC BY-SA 3.0] via Wikimedia Commons](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1434646227i/15247823._SY540_.jpg) Crypta Neapolitana by Mentnafunangann. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Crypta Neapolitana by Mentnafunangann. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Tiberius Julius Tarsos

The Roman freedman Tiberius Julius Tarsos built a temple to the Dioscuri in the centre of Naples; today, you can still see two of its Corinthian columns built into the facade of the church of S. Paolo Maggiore. Originally these columns supported a magnificent pediment filled with sculptures of mythical and historical figures including Artemis, Apollo, and perhaps also a personification of the local Sebethos river. Legend has it that St Peter himself made these sculptures fall from the pediment when he passed through Naples on his way to Rome, and what Peter didn’t manage to destroy, a seventeenth-century earthquake unfortunately finished off for him. Luckily, we still have drawings made by Renaissance artists and antiquarians which preserve details of this great monument, including the large marble inscription from the front of the facade naming Tarsos and the gods to whom the temple was dedicated.

Saint Janarius (4th century)

No list of great Neapolitans could leave out the early Christian martyr Saint Janarius (San Gennaro in Italian), or the two vials of his dried blood which still liquefy miraculously three times a year. San Gennaro is said to have been put to death in Pozzuoli in 305AD, in the final year of the Diocletianic Persecutions. He and some fellow Christians were beheaded inside the Solfatara crater, which was already a place redolent with ancient mythological associations (Strabo described it as the ‘Forum of Hephaestus’). Like Parthenope and Virgil before him, Gennaro was swiftly adopted as the city’s patron and protector, and – again like Parthenope – he was also seen to combat the fires of Vesuvius with one of his bodily fluids. This time though, it wasn’t the quenching nature of breast-milk, but the ‘sympathetic magic’ of erupting red blood which stopped the flow of volcanic materials.

Romulus Augustulus

Romulus Augustulus was the last Roman Emperor, and he made Naples great(er) by ending his life there. He’d been exiled to the city at some point during the later fifth century, and imprisoned on Megaride in the very castle that would later become home to Virgil’s legendary egg. In hindsight, the body of Romulus Augustulus had its own talismanic quality – for just as the fate of Naples was linked to the fragile egg, the death of Romulus signalled the end of the whole Roman imperial lineage. Even more mysterious is the fact that his body vanished without a trace, and that no monument (other than the castle itself) survives to commemorate him. But then, perhaps that’s the perfect way to end an Empire?

Headline image: Napoli da Corso Vittorio Emanuele by IlSistemone. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Six people who helped make ancient Naples great appeared first on OUPblog.

Parent relationships: perspectives from emerging adults

Relationships with teens and parents can be difficult, but significant changes often take place during emerging adulthood as well. How do emerging adults relationships with their parents develop? Are they better or worse than their teenage years?

Whether living at home or just moving away, both parents and emerging adults experience a shift in their relationship. While many emerging adults prefer living independently, they find that they grow closer with their parents. Moreover, parents find that as their children become adults, they are viewed more as friends. With data from the new edition of Jeffrey Jensen Arnett’s Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties, we present this infographic on emerging adults’ attitudes towards parental relationships.

Download the pdf or jpg of the infographic.

Headline image credit: Drivers License. Uploaded by State Farm. 19 August 2013. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Parent relationships: perspectives from emerging adults appeared first on OUPblog.

June 17, 2015

The Democratic Party and the (not-so?) new family values

“You [as parents] have no rights. That statement is coming true at an alarming rate – but here and there, isolated voices are crying out, ‘This far and no farther – we will not surrender…’”

—John Steinbacher, The Child Seducers, 1970

In 1970, archconservative journalist John Steinbacher seethed at what he considered the worst casualty of the Sixties, a decade defined by two Democratic presidencies, expanded federal intervention in what felt like every dimension of daily life and defiant young activists sporting shaggy beards and miniskirts rejecting authority of all kinds. Unable to withstand these seismic shifts, he despaired, the American family was in grave peril. In the 45 years since Steinbacher’s bestseller, this far-right outrage has amplified from a handful of “isolated voices” to become a cri de coeur of contemporary conservatism, an impassioned mission to safeguard “family values” and the nation’s moral health from the depredations of ethically suspicious liberals.

During the same period, Democrats have mostly sidestepped the accusation that their principles and policies are at root “anti-family.” Instead, they loudly champion the civic benefits of polemical policies such as comprehensive sex education, abortion, and gay rights and gleefully exploit Republican transgressions (think South Carolina governor Mark Sanford’s infidelity, North Carolina senator Steve Wiles’ drag-queen past) more as a means to expose conservative hypocrisy than to cement their own party’s credibility as defenders of family values.

Yet if Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton’s splashy new campaign is any indication, these familiar positions are in flux, and family will be front and center in the 2016 presidential campaign.

Perhaps least likely to spearhead a liberal reconquest of family values, given Clinton’s powerful identity as a career-focused feminist, the notorious infidelity of her own husband, and comments like her derisive 1992 slight that she could have “stayed home to bake cookies and have teas,” she is already unapologetically positioning herself as a champion of the American family for 2016. Her campaign videos cast her as a kindly grandmother, a mother of the bride, and an adoring daughter, co-opting the familiar language of right-wing groups such as Focus on the Family to celebrate gay and interracial marriage, family leave policy, and the contributions of working women.

Clinton’s rhetorical about-face is initially jarring, but actually harkens back to a long progressive tradition of advocacy for policies that strengthen (rather than sabotage, as conservatives for decades have successfully suggested) American families.

Long before Steinbacher and his ranks bemoaned the destruction of the American family, early twentieth-century women framed their pleas for welfare and protective labor legislation as an extension of their identities as mothers and guardians of the sacred family. This mobilization provided a key foundation for the suffrage movement; these feminists went on to demand the vote as a way to extend the moral guidance they exercised at home as mothers and wives into the public sphere. During the Depression, this “maternalist” political strategy was powerfully elaborated by activists who demanded a “family wage” with the goals to legitimize the housework performed by women and to expand males’ access to the shrinking pool of jobs that would enable them to remain breadwinning heads-of-household. As a raft of feminist scholarship has shown, this activism effectively narrowed the provision of many New Deal economic benefits to the married and cemented traditionally gendered divisions of labor. Decried by conservatives in Steinbacher’s day and today as the most damaging phase in the decades-long expansion of the fearsome federal government, the quintessentially liberal New Deal did more to inscribe an assumed nuclear family in federal policy than any “family-values conservative” will have you believe. Embodying a range of intents and impacts, progressives have been intimately invested in elevating the family for over a century.

It was only after World War II, when women’s workforce participation grew dramatically, and when the sexual revolution, feminist, and gay liberation movements converged in what looked to be a full frontal assault on heterosexual marriage and its attendant domesticity, that the Steinbachers of the world found an eager, emergent conservative movement seeking a rallying cry. By 1972, activists such as Phyllis Schlafly seized upon the family as the imperiled target of liberals and progressives, and threatened that if the Equal Rights Amendment passed, women would end up “drafted by the military” and using “public unisex bathrooms,” not to mention forgoing their “dependent wife” Social Security benefits.

Multicultural family. Photo by Pankoroku. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Multicultural family. Photo by Pankoroku. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Still, progressives hardly abandoned their interest in protecting families during this tumultuous period. From different quarters, Democratic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s controversial 1965 report on the state of the black family demanded federal action to counter the trend of female-headed households in poor black communities. Countercultural feminists celebrated womanhood specifically in service of intensified family bonding, championing “attachment parenting,” natural childbirth, and co-sleeping, a movement that has moved from the cultural fringes to shape policies like the contemporary breastfeeding measures adopted by the Obama White House and New York City.

Today’s cultural climate is arguably ripe to redefine “pro-family” as something more inclusive than the heterosexual, white, suburban version of pious domesticity that conservatives have made one of their most resonant tropes in the last half-century. The New York Times recently reported an unprecedented consensus on abortion, the issue that helped cement the Right’s hold on the family with the passage of Roe v. Wade in 1973. Working mothers, it turns out, might confer long-term benefits on their children’s development as individuals and family members. The widening acceptance of gay marriage in the United States and abroad and the spread of gay families even in conservative enclaves intimates that the moment might be optimal for the Democrats make the fight to protect the family a core plank of the platform.

The impact of resuscitating this liberal tradition as part of the 2016 Democratic platform is anyone’s guess. Will it radically reshape one of society’s most conservatizing institutions, enabling progressives to advance in territory unchallenged for decades? Will it alienate progressives resistant to an apparent throwback to early twentieth-century maternalist politics that defined even civically active women foremost as mothers and wives? It’s possible, given the newly public voices of those who decide not to have children and who might not race to the polls to support a candidate who launched her campaign with the declaration that “When families are strong, America is strong!,” a refrain that feels reflexively right-wing in 2015. What is assured is that these social and cultural questions, often dismissed as secondary to economic or geopolitical concerns, will be paramount in the presidential contest of 2016.

Featured image: Family portrait. Photo by Eric Ward. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Democratic Party and the (not-so?) new family values appeared first on OUPblog.

Approaching the big bad word “bad”

In the near future I’ll have more than enough to say about bad, an adjective whose history is dismally obscure, but once again, and for the umpteenth time, we have to ask ourselves why there are words of undiscovered and seemingly undiscoverable origin. Historical linguists try to reconstruct ancient roots. However, roots need not be looked upon as generators of words. It is far from obvious that at one time, however remote, complexes like bher, bhel, and so forth were the main units of human speech, flying or floating around Peter Pan-like, and that only later they added suffixes and began to resemble modern words. However, this is what some nineteenth-century scholars, who were inspired by the structure of languages like Chinese, thought. Yet Chinese reached its present stage after centuries of development, and in this respect it resembles English, with its predominantly monosyllabic native vocabulary. At least in the Indo-European family the oldest languages known to us have long, often very long words.

Even if we succeed in obtaining a primordial root endowed with an obvious meaning, we seldom know how its sounds and sense met. For example, good has the root meaning approximately “passing, fitting.” But what is there in the g-d complex to suggest the idea of appropriateness? As far as we can judge, absolutely nothing. In many other cases we have no way to reach the level of the protolanguage. A typical case is slang. Apparently arbitrary groups of sounds, which certainly do not trace to Indo-European (no doubt about that), acquire a recognized meaning and refuse to disclose their origin. Why bloke, dud, and dude? Bloke is supposedly a borrowing from Shelta, the cryptic language of Irish tinkers, among others. (Shelta is itself a word of unknown origin.) We find duds “clothes; rags, tatters,” so that dud “worthless fellow” may be a transferred use of dud “rags, tatters” (compare the history of brat “child,” believed to go back to brat “coarse garment”), but alas, the origin of dud “rags” is also unknown. Dude fares slightly better. At one time, I wrote a post about dude and was rewarded by numerous comments (for nowadays everybody is a dude, right?). If the root g-d suggests satisfaction, are we allowed to extract a hidden meaning from d-d?

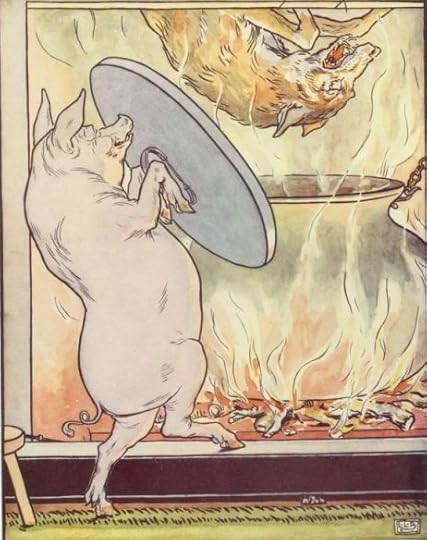

This is the Big BAD Wolf. Quite expressive, isn’t it?

This is the Big BAD Wolf. Quite expressive, isn’t it?The most tempting hypothesis in etymology connects hundreds of words with sound imitation and sound symbolism. Fierce battles raged in the past among those who thought that language developed from words like bow-wow and those who sought the beginnings of language in interjections. Yet even those complexes are capricious. Do pigs “say” oink-oink and dogs “say” bow-wow? Is oops a word worthy of our interest? Regardless of the answer, squeak, squeal, grunt, bark, chirp, and hush, to mention a few, are certainly onomatopoeic (sound imitating) words, while good and bad are not. Unlike sound imitation, sound symbolism is a hazy concept. Specialists who study the connection between the phonetic shape of words and their meaning call their branch of linguistics iconicity. Some of their conclusions cannot be put into question. People regularly lengthen vowels and make them more open to designate a large size. They also do all kinds of other things along the same lines. André Martinet, one of the most distinguished linguists of the twentieth century, wrote a book in which he analyzed the origin of long consonants in various languages and concluded that they were of “expressive nature.” Not all of his examples are convincing, but dozens of them are. For instance, when people coin a verb denoting a strong effort, they tend to lengthen the final consonant. The word tries to mirror the action.

It has also been noticed that monosyllabic words beginning and ending with b, d, g and having a short vowel in the middle often resemble those explored by Martinet. Big, bob (in all of its senses), bib, gig, gag, agog, dud (see it above), and many others can be called expressive. Bag and bug, both suggesting swelling, like big, belong with them. A look in a dictionary shows that none of the words listed above has an ascertained etymology. Dig was mentioned last time in connection with bed. If bed signified an object dug with an effort, its distant origin may be expressive, like that of dig. Even when a word of this type has been borrowed or is suspected of having been borrowed, like gab and the possibly related gob, they are felt to be expressive, slangy, or at the very least not belonging to the neutral style. Beg is not sound symbolic (this verb was discussed in great detail some time ago), but begging is an action that evokes strong emotions in those who ask for alms and those who receive them. Perhaps the stylistic coloring (a nasty verb to describe a terrible thing) helped it to come into existence and stay in the language. One of the toughest words to etymologize is dog. We notice that it shares its structure with dig, big, bug, and the rest.

Don’t visualize ancient roots in this form.

Don’t visualize ancient roots in this form.Sound symbolism and expressivity are hard to pinpoint. The researcher depends on what the informants say and “feel.” Some people believe that gl- suggests light, while sl- suggests mud. Others cite glove, gloat, glum, and gloom and ignore glare, glisten, glow, and gleam. Slime, sleaze, slop, slip, and slither coexist with slow, slay, slim, slave, and sledge. Nothing can be proved here, but ignoring emotions in the life of language should not be recommended. It is only dangerous to be run away by too much zeal, to use the passive construction now becoming obsolete. Once, instead of being a useful tool, sound symbolism becomes a skeleton key meant to open all doors, it loses its value.

The musings offered above are meant to introduce the next post that will deal with the etymology of bad directly. It will be shown that despite some progress in the search for this word’s distant past, its origin has not been found. In principle, if after multiple attempts to discover a definitive etymology of an old word the solution escapes a host of knowledgeable people, the chances of a future breakthrough are not high. To be sure, an important but formerly neglected cognate, a previously unknown foreign source, or a new document can suddenly (almost miraculously). Failing that, the word will probably never lose its sad label “origin unknown.” As far as our topic is concerned, I should like to say only one thing. Bad is a word of the structure discussed above. It belongs with bed, beg, bog, gab, and so forth. It is clearly an expressive word. No one wants to be called bad. Therefore, it may be that bad has no etymology in the strict sense of this term. To put it differently, it might have been coined as a spontaneous expression of disapproval or disgust, like ick or yuck. Who knows? Perhaps the etymology of bad should be looked for somewhere in that verbal quagmire, or let us call it “bog.”

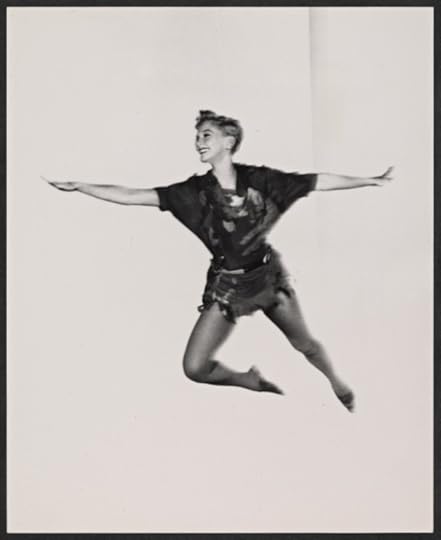

Image credits: (1) Cartoon big bad wolf. © lineartestpilot via iStock. (2) Three Little Pigs – the wolf lands in the cooking pot – Project Gutenberg eText 15661. Illustration by L. Leslie Brooke, from The Golden Goose Book, Frederick Warne & Co., Ltd. 1905. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Peter Pan. [1954]” Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library. Copyright: The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The post Approaching the big bad word “bad” appeared first on OUPblog.

50 shades of touch

Disgusting or delighting, exciting or boring, sensual or expected, no matter what you think about it, 50 Shades of Grey is certainly not a movie that passes by without leaving a mark on your skin. Based on E.L. James’ novel (honestly, somehow even more breathtaking than the movie), it tells the story of the complicated relationship between the dominant multi-millionaire Christian Grey, and the newly graduated, inexperienced, and shy, Ana Steele. Christian leads Ana towards his sensuous and deviant world (though, who really does take the lead is unclear), made of ropes, riding crops, chains, and strict rules. Since the first time I saw the movie, and when I read the book, I could not help but think about the sense of touch, the main object of my scientific research into the neurocognitive mechanisms of human perception, emotions, and desires. After all, isn’t the novel about the sensual power of touch? How arousing can a light touch on the neck be? A kiss to the hair? And what about the constriction of rope around your wrists? I was reflecting about where this incredible power comes from, and here my research can help.

We now know that human bodies have a privileged path to pleasure, one that passes through the sense of touch: CT fibers. These neural fibers conduct information to the brain from the non-glabrous areas of the body (from those body parts with hairs) and are activated by a caress like stimulus. They must signal comfort and pleasure to our brain, which reacts accordingly. This system is probably an inheritance from our monkey-like ancestors, social animals that used to groom one another, also as a way to set their reciprocal status (dominance) within the group. However, touch is much more than that; it also contributes to the release of hormones, oxytocin in particular, the bonding (or cuddle, as popularly defined) hormone. From a scientific point of view, touch actually sets the pace of a relationship, as there is evidence regarding the presence of a strong correlation between the level of blood oxytocin, the amount of touch within a couple, and the quality of their relationship as rated by the couple.

The two main characters in the novel seem to be attracted towards one another by a magnetic force, which pushes their bodies towards unexplored limits. Another important function of touch is actually to set the limits of our body, to define what is ‘us’ and what is not. Not surprisingly, in the last few years, discussion on the neural substrates of ‘body ownership’ has become very popular among cognitive neuroscientists. That is, how our brains can define which body parts do and don’t belong to us. “Where our touch begins, so do we,” I often tell my students at university, and when someone touches us, we lose a bit of this limit; we become part of the other person.

Undeniably, the novel is also about the relationship between dominance and submission; about the question of who is really in charge. However, what really is the difference between these two aspects? Isn’t the sense of touch the real leader in this situation too? Who can touch? When? How? Where? We can watch and hear, but we cannot touch someone without consent. In the author’s second novel, 50 Shades Darker, the ‘untouchable’ Christian asks Ana to use a red lipstick to draw on his chest a map of body areas that she is allowed to touch and areas that are off-limits. Again I’m led to wonder, is touch really that powerful? Scientific research provides a positive answer to this question. Touch has been shown to affect people’s compliance towards a request, their willingness to give more, and their desire to please someone. A number of researchers have shown that people are much more willing to say yes to a request if they are touched first.

The Oculus Rift,. A 2013 virtual reality headset from Oculus VR, a company Facebook acquired in 2014 for $2 billion. By Sebastian Stabinger. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Oculus Rift,. A 2013 virtual reality headset from Oculus VR, a company Facebook acquired in 2014 for $2 billion. By Sebastian Stabinger. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Finally, 50 Shades of Grey is also about the boundaries between pleasure and pain. Many people may wonder why some individuals are willing to receive corporal punishments by someone they love (and even take pleasure from it). More generally, how can a ‘spank’ be perceived as pleasant? The answer to these kind of questions certainly has much to do with the ‘reward neural circuits’, buried in some of the deepest and evolutionarily oldest parts of our brain. No one would perceive pain as pleasant when out of the right context. Just as other sensations, pain is a creation of the brain; as a colleague of mine is often heard saying: ‘no brain, no pain’, and I’m inclined to agree. Many stimulations in the brain interact to determine the perception of pain, and touch certainly takes an important role in this modulation of sensations. Sensual touch is a strong reward, and the brain can lead you everywhere in order to get its reward. Even pain under these conditions can become pleasant.

It’s interesting to consider the same novel without so much reference to touch, and even more interestingly, how our lives might be without tactile sensations. How might our relationships be? These thoughts lead me to think about another aspect relevant to my research: human-machine interfaces. Modern technology, if it continues to be effective, will need to use touch, especially in order to reproduce social interactions. Virtual reality in particular will have limited use without the capability to reproduce realistic connections between our bodies and objects, and/or between people’s bodies (being them real on just computer-generated). Here, I have a specific scene from the movie in mind, the one where Christian uses an ice cube to arouse Ana (admittedly a very often-adopted image in fictional erotic scenes). The effect is strong, and its visual impact intuitive. How can technology reproduce something similar? The sensation of wetness on the skin is certainly a very complex one. From a neuroscientific point of view, it requires the activation of at least two classes of receptors: one for temperature; the other for movement over the skin. Without this mixture of neural signals (and the brain’s interpretation of them) we cannot get such a sensation, just as when you do not feel your body wet while lying completely still in a bathtub full of hot water. So how can these sensations be reproduced artificially? Every time I think about these aspects, I can’t help but think about what a huge challenge this is. Will technology ever be able to get even close? Will touch through interfaces become possible between two people separated by miles? I want to be positive, but in order to get there, researchers will need to increase their study into the powerful and still mysterious sense of touch, in all its 50 (and more) shades.

As a neuroscientist, and a man who is hypnotized by the magic behind that sense, I am definitely thrilled about what we will learn in the future regarding the brain mechanisms responsible for tactile sensations!

Featured image: “Shades of Gray” By AnonMoos. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 50 shades of touch appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers