Oxford University Press's Blog, page 651

June 22, 2015

Being defaced: John Aubrey and the literary sketch

John Aubrey might have made an excellent literary agent. When Charles II was restored, Aubrey told Thomas Hobbes to come down to London straight away to get his portrait painted. It was a successful bid for patronage. Aubrey correctly calculated that Hobbes would meet the King at the studio of Samuel Cooper, ‘the prince’ of miniaturists. Cooper painted two watercolour miniatures, “as like as art could afford.” One the King took away for his “closet” at Whitehall Palace, and another was not finished.

This incomplete sketch is now in the Cleveland Art Museum. The formidable “old gent” stares out with a firmness and vitality out of all proportion to the state of finish of his portrait; the surrounding detail is barely sketched in. It could stand as Aubrey’s biographical signature. As he explains, he was offered this portrait by Cooper once he had finished it but, “like a foole,” did not insist on taking it at once in its unfinished state. Cooper then died and Aubrey lost his chance.

This was the story of Aubrey’s life, as he chose to tell it. His own portrait, also by Cooper, was stolen from the Ashmolean Museum in his lifetime, along with another precious miniature by Nicholas Hilliard. Brief Lives describes the hit and miss process of constructing memorials from materials which are, as he put it, “like fragments from a shipwreck, sinking to the bottom, or like winged birds, which fly away if not swiftly trapped.” Insisting on literary completeness and polish, waiting for the perfect moment, allowing the birds to escape: his works are nets: full of holes, but swarming with a mixed catch.

Portrait of Thomas Hobbes, c. 1660. Samuel Cooper (British, 1608/09-1672). Watercolor on vellum in a gilt metal frame; 7.3 x 6.3 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, The Edward B. Greene Collection 1949.548. Used with permission.

Portrait of Thomas Hobbes, c. 1660. Samuel Cooper (British, 1608/09-1672). Watercolor on vellum in a gilt metal frame; 7.3 x 6.3 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, The Edward B. Greene Collection 1949.548. Used with permission.In the preface of the Life of Thomas Hobbes, Aubrey said that “First sketches ought to be rude, as those of paynters: for he that in his first Essay will be curious in refining will certainly be unhappy in inventing.” This much-quoted defence of the state of his unfinished works has always been taken as a spontaneous confession. But it is not actually spontaneous at all. Aubrey is quoting from a letter written to him by the musical theorist Thomas Pigot. This letter was the beginning of a process during which Aubrey manoeuvred to bring Pigot’s unfinished treatise, ‘de Sono,’ to the notice of the Royal Society. In return, Aubrey asked Pigot to visit a manor house near Oxford to transcribe an inscription on a copy of Holbein’s group portrait of Sir Thomas More and his family, “for it begins to be defaced.”

In Brief Lives, whose defaced Greek title, Schediasmata, means “a thing made extempore”, Aubrey was even more determined to present the world with an unfinished work, and to defend the integrity and inventiveness of the ‘rude’ sketch. The Lives tell the story of wasted creativity and unfinished projects, such as William Harvey’s manuscript on the anatomy of insects which was plundered during the Civil War, and a canal-building scheme which did not receive funding. Yet behind the text is a much more complex story, with which Brief Lives is intertwined, one of intellectual patronage and the beginnings of a sense of the national heritage. Aubrey was engaged to an amazing degree in attempts to support the ingenuity and talent of his vast circle, bringing the marginal and the neglected to the centre, finding copies of lost and minor works, and images of lost faces.

When you open the manuscripts of Brief Lives what strikes you immediately is their visual vitality. They have the sketchy quality of works in progress, great complexity of interlinings, crossings-out, inserted papers, and the marginal comments of friends. They contain pictures and coats of arms, printed portraits, horoscopes, and architectural drawings. There are 160 images in the manuscripts, and the Lives have an unmistakable look. You can follow the research taking place, the changes of information, the involvement of others, and, less positively, the censorship of many pages by a collaborator whom Aubrey had trusted. Brief Lives is a work which charts the vicissitudes of writing a ‘modern history’ in a particularly turbulent century. Aubrey claimed that the truth appeared in the work “exposed so bare, that the very pudenda are not hid.” In it Aubrey presents us with a nude portrait of the seventeenth century, in an incomplete form, one which he called its “puris naturalibus” — a pure state of nature.

Header image credit: John Aubrey, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Being defaced: John Aubrey and the literary sketch appeared first on OUPblog.

Climate change and self-adapting law

How would law look different if we had always known about climate change? One difference – I would suggest – is that it would have been constructed so as to self-adapt to the changing context that it seeks to govern. What does it mean to self-adapt? An example of self-adapting law can be found in long term supply agreements. These agreements recognise that swings in the price of a particular commodity may alter the underlying economics of an entire transaction. Therefore they include an escalator clause that alters the terms of the contract as related prices change. Similarly, in the face of climate change, we need to ferret out the unintended, harmful, non-adaptive parts of existing law that may make climate change worse and draft new laws that are self-adapting.

Elsewhere, I have termed the unintended harmful non-adaptive parts of existing law as a negative legal feedback to climate change. In the science of climate change, a negative feedback is a physical process triggered by climate change that exacerbates the underlying process of climate change. For example, melting of the tundra in the far North, as a result of warming, may lead to the release of significant amounts of methane that in turn may accelerate the process of warming. A legal feedback, unlike a physical feedback, does not accelerate or mitigate the underlying process of climate change itself. Rather, it accelerates or mitigates the damage that will be felt as a consequence of any level of climate change. Moreover, a legal feedback, unlike a physical one, is not fixed in the laws of nature, but rather is socially constructed and thus can be changed.

An example of a negative legal feedback will arise from the international law of baselines from which ocean boundaries are drawn. The law of baselines is a set of detailed rules that, broadly speaking, seek to give content to the principle that baselines (and the boundaries drawn from them) should follow the general direction of the coastline. In many cases, the law of baselines allows such lines to be based on geographic features barely above sea level. Therefore, almost any change in sea level from climate change may have quite dramatic effects on certain baselines. This physical effect on what legally counts as a baseline may have a potentially dramatic effect on boundaries. This is because the baselines and boundaries generated from them are “ambulatory” (that is, the baselines – and therefore the boundaries, adjust themselves to a changing coastline). Consequently, the unanticipated rise in sea level in particular geographic situations will result in unintended and significant shifts in the outer boundaries of the oceanic zones claimed by coastal states. The law of baselines gives rise to a negative legal feedback because it increases both the potential for the waste of resources aimed at protecting what counts as a baseline, as well as private and interstate conflict over the uncertainty of boundaries.

In contrast, the “public trust doctrine” in US common law, which places certain restrictions on the alienation and use of waterways in the United States, is an example of a self-adapting law. The public trust doctrine has, built into it, a measure of flexibility that intentionally accommodates change in the environment. While US states differ in whether they set the boundary of the public trust at the high tide mark, low tide mark or at the vegetation line, those boundaries (and therefore the boundary of the trust) are ambulatory and take into account changes in water levels. This flexibility will thus take into account sea level changes as it happens extending the trust potentially over what is privately held adjacent land. Whether the doctrine extends to lands that are highly likely in the future to be submerged by a rising sea level is yet to be decided, but it at least seems possible. Unlike the case of ocean boundaries above, the reason for the legal boundary is not frustrated by rising sea levels. Since the purpose of the public trust doctrine is “an affirmation of the duty of the state to protect the people’s common heritage of streams, lakes, marshlands and tidelands, surrendering that right of protection only in rare cases when the abandonment of that right is consistent with the purposes of the trust” (Nat’l Audubon Soc’y v. Superior Court, California Supreme Court, 1983), then the movement of that doctrine along with the waters its governs furthers that purpose. There is, of course, the interests of those on the other side of any boundary. In the case of the public trust, the interests of the private property owners are threatened more by the rising sea level than by the protections they gain with all others from the extension of the public trust doctrine to not only its land but to all other lands submerged.

It is sometime said that the law is a living thing. On the one hand, the law in its totality may be conceived in this way because it changes through legislation and judicial construction, it changes as a result of imaginative argumentation and it reflects society’s changing values. On the other hand, particular laws are artifacts. Given that these laws were made with past circumstances in mind, it is possible that they do not suit the needs of today. The world may change in ways that were never contemplated when particular policy choices are made into law. Ideally, law should change with the world around it. But given the slow pace of legal evolution, there is inevitably a period of time when the law has not yet changed to reflect modern realities and in that period it often fails to promote either wise policy or just outcomes. Since legal doctrine is fundamentally challenged by climate change in this way, legal disputes are inevitable and adjudicative processes will be important sites for testing and developing doctrine that has not yet adapted to the reality of climate change. Equally, legal scholars have an important task in helping to construct a law that is responsive to such significant change.

Featured image credit: Coast By Owen Walters. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Climate change and self-adapting law appeared first on OUPblog.

June 21, 2015

Islamic State and the limits of international ethics

The moral outrage at the actions of Islamic State (IS) is easy to both express and justify. An organisation that engages in immolation, decapitation, crucifixion and brutal corporal punishment; that seemingly deploys children as executioners; that imposes profound restrictions on the life-choices and opportunities of women; and that destroys cultural heritage that predates Islam is despicable. What drives such condemnation is complex and multifaceted, however. For example, for Muslims, the perversion of their faith, the decontextualization of the words and deeds of the Prophet, and the insistence on a singular account of one of the world’s richest traditions of theological jurisprudence are central. For liberals, the denial of fundamental human rights, the rejection of equality, the repression of debate or criticism, and cruelty stand out as determining the immorality of IS’s actions and beliefs. And so on. There are multiple bases for outrage, and those bases may share many traits.

Moral condemnation of the actions and doctrines of IS thus reveals one way in which accounts of ethics that draw their inspiration from very different bases can nevertheless coincide. IS is intolerable in a rich and specific sense of the idea of toleration. It is not the antithesis of something that must be put up with, undesirable though it is, for practical reasons of immutability, whether in the short or long term. Instead, IS is intolerable because it seemingly offers no basis for reciprocity of toleration. IS’s moral condemnation of Shi’ism and Shiites, of Sunni Muslims who do not share its interpretation, of Jews and Judaism, or liberalism can only manifest in violent rejection. This feeds a political response by those threatened by IS that is frequently seen as necessarily violent. Negotiation or rapprochement with IS is, simply, impossible. Self-defence, through the use of force, is not only morally justifiable but a moral imperative. In a political situation a group is governed by a belief system that necessitates the destruction of those who reject that system, the limits of any possible bases for toleration are removed. This is not simply about not ‘putting up’ with such a belief system; it is about recognising that it can offer no basis for reciprocal acceptance of the potential contribution such a system might make to the continual dialogue amongst human communities about how to live. That dialogue must, to be worthwhile, include an account of how to live together that IS appears incapable of entering.

Kurdish protest against ISIS, by Alan Denney. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Kurdish protest against ISIS, by Alan Denney. CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0 via Flickr.Violent and exclusionary political projects are unknown – far from it – but those that require for their existence the destruction of others are, thankfully, a comparative political rarity. Those rare exceptions are, necessarily, terrifying because the negation of the possibility of inter-communal dialogue represents such a departure from deep-rooted ideas about the ethical underpinnings of politics, at many levels. The idea of ethical diversity through different ethical traditions and their manifestations in diverse communities is often seen as presenting a serious challenge to the possibility of a universal ethic, or, at least, to the establishment of a political system rooted in an operationalising a meaningful, substantive universal ethic. In international relations, the idea of ethical diversity as partially and imperfectly manifested in sovereignty has long led many to argue that some kind of ‘live and let live’ principle is the best that can be achieved (if ‘you’ don’t interfere in ‘our’ affairs, ‘we’ won’t interfere in ‘yours’ and we will all get along better that way). Such a system is attractive to some, but objectionable to others who fear it reflects a moral relativism that makes it impossible to convincingly deplore inhuman cruelties perpetrated in the name of sovereignty. The universal condemnation of IS belies such a relativist critique, but does highlight the question of what makes such a consensus possible, given the purported absence of the basis for consensus.

What seems telling about these rare exceptions is that their radical intolerance is predicated on accounts of their own community’s value that are exceptionally closed and sclerotic. The community’s narrative of its own value, its place in the world, and the place of others is seen to be unquestionable, and that to seek to question that narrative invites severely repressive consequences. Authority within the community is understood to be typically exceptionally hierarchical and rooted in self-referential claims about authoritative interpretations of fundamental precepts that brook no objection. As a result, any potential bases for entry into the inter-communal debate about how to live together are denied and toleration of the other – where toleration is understood as recognising and valuing the distinct contribution a different perspective may bring – is impossible. In many cases, in relations with other communities, those points of entry may appear biased and irrational, the processes of change they enable apparently glacial in their progress, or their internal decision-making systems illogical or heavily loaded, but where they are present there is a basis for mutual toleration because change is immanent and the potential for living together thus present.

The moral condemnation of IS is valid for many reasons and in many ways, and what unites them all, is a necessary rejection of a perspective on humanity that is so closed and sclerotic as to preclude the very possibility of toleration. A group such as IS is terrifying – morally speaking, as well as politically – because it rejects any possible basis for participating in the process of living well, together.

The post Islamic State and the limits of international ethics appeared first on OUPblog.

OUP staff discuss their favourite independent bookstores to celebrate Independent Bookshop Week

In support of Independent Bookshop Week, a campaign run by the Booksellers Association that supports independent bookstores, we asked staff from the Oxford University Press UK office what their favourite independent bookstores were. We received a very enthusiastic response, and discovered that our UK staff visit and revisit indies all over the country for the love of books that these stores inspire. Here’s what our staff had to say about their favourite indies:

*****

“There’s an independent bookshop in Bicester called Cole’s. We order everything from them (including DVDs) and have done for as long as I can remember. (They had a play room out the back which I know gave my parents some peace to shop.) The staff are so friendly and knowledgeable, they can suggest excellent books and even call us up as soon as an order is ready to be collected. It’s where we queued up to buy all the Harry Potter books and it has such an amazing atmosphere that encourages children to read. (They even tweet.)”

– Alice Leigh, Marketing Assistant, Law

*****

“Maria von Trapp can keep her raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens. Two of my favourite things are books and cake – and Jaffé & Neale in Chipping Norton provides both of those in spades. With events throughout the year, including the Chipping Norton Literary Festival, a book club, and a huge selection of new and second hand books, it is well worth a visit. The children’s section is lovely too with plenty of choice; I always seem to come away with something I haven’t seen before! P.S. try the orange polenta cake. It’s immense.”

– Rachel Fenwick, Marketing Manager

Jaffe & Neale bookstore. Photo by Rachel Fenwick.

Jaffe & Neale bookstore. Photo by Rachel Fenwick.*****

“I love many UK independent bookshops but my absolute favourite independent bookshop is based in Paris, Shakespeare & Co., because of its intimate atmosphere, tiny reading nooks, and its long literary history. Having opened in 1951, the book shop is supported by its founder, George Whitman’s philosophy: “Be not inhospitable to strangers lest they be angels in disguise.” As a result of this, Shakespeare & Co. has helped writers and those involved in the arts by allowing them to sleep at the shop. They also host musical and literary events there, and the bookshop now has its own ‘Paris Literary Prize’ for unpublished writers. I visited in 2008 with my best friend Grace, and I bought an old copy of one of my favourite childhood books, The Waterbabies by Charles Kingsley.”

–Miranda Dobson, Marketing Assistant, Law

*****

“Hay-on-Wye is the promised land for those of us who prefer our books old and dusty. Richard Booth is the self-appointed king of ‘the Kingdom of Hay’, and Richard Booth’s Books is my favourite of the many secondhand, independent bookshops in said kingdom. It’s not quite as dusty as some, but the choice is superb, and I never fail to leave with heavy bags and a lighter wallet.”

- Simon Thomas, Marketing Executive, Oxford Dictionaries

Richard Booth’s Books. Photo by Simon Thomas.

Richard Booth’s Books. Photo by Simon Thomas.*****

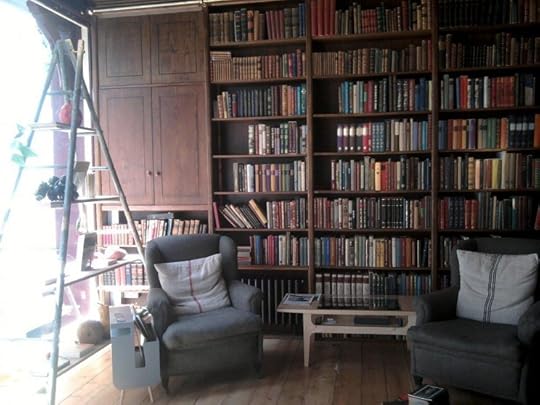

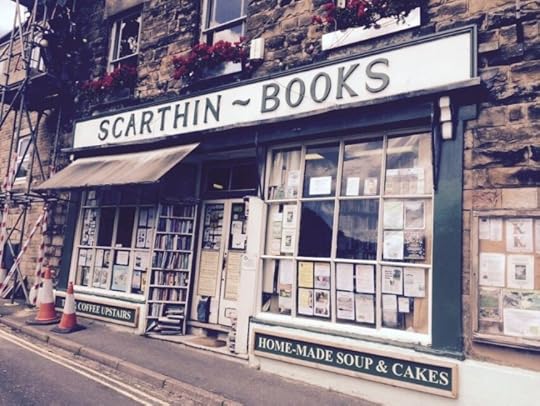

“My favourite independent bookshop is Scarthin Books in Cromford, Derbyshire. It was definitely my second home when I was growing up, and I wouldn’t like to comment on how many days I have spent in there. I am now given a time limit when we visit. There are miles and miles of book shelving. In fact they have just had to have four steel columns installed to support the weight of the 100,000 books! It is regularly listed as one of the top bookshops in the world, the staff are ridiculously knowledgeable and the café is always full of amazing cakes. What more could you want?”

– Hannah Paget, Trade Marketing Executive

Scarthin Books. Photo by Hannah Paget.

Scarthin Books. Photo by Hannah Paget.*****

“Although a bit of a trek from Oxford and not quite close enough to nip in on a whim, Mr B’s Emporium of Reading Delights is exactly that. Tucked away in a little side street behind Bath’s main shopping street and just a stone’s throw away from the Jane Austen Centre, it’s got everything you expect from a great indie bookshop. If short on time, you can briefly browse and discover new gems from the excellent staff recommendations or (if you have more time) spend most of the day in the ‘Bibliotherapy Room’ with a hot drink and a good book. And since it’s Bath, there are of course bath tubs used for the displays.”

– Kim Behrens, Associate Marketing Manager

Mr B’s Emporium of Reading Delights . Photo by Kim Behrens.

Mr B’s Emporium of Reading Delights . Photo by Kim Behrens.*****

Featured image credit: “Bookshelves,” by gpoo. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post OUP staff discuss their favourite independent bookstores to celebrate Independent Bookshop Week appeared first on OUPblog.

How is the mind related to the body?

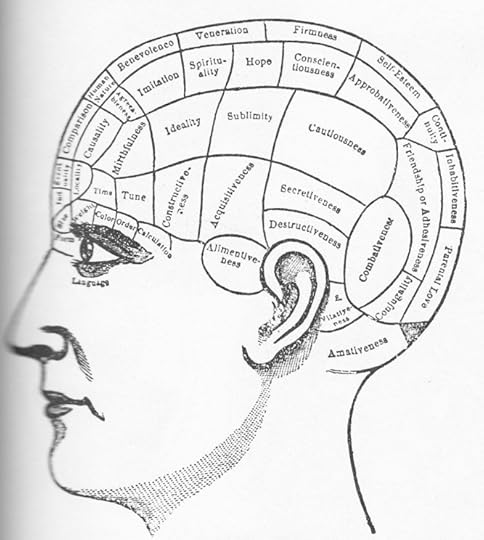

At one point in the recent film The Imitation Game the detective assigned to his case asks Alan Turing whether machines could think. The dialogue that follows is perhaps not very illuminating philosophically, but it does remind us of an important point: the computer revolution that Turing helped to pioneer gave a huge impetus to interest in what we now call the mind-body problem. In other words, how is the mind related to the body? How could a soggy grey mass such as the brain give rise to the extraordinary phenomenon of consciousness?

The mind-body problem is one of the most controversial issues in philosophy today, and it generates intense passions among the parties to the debate (witness the recent exchange between Galen Strawson and other philosophers in the correspondence columns of the Times Literary Supplement). Some modern philosophers, such as Colin McGinn, believe that the mind-body problem is so intractable that we shall never be able to solve it; we simply don’t possess the concepts necessary to understand how consciousness could emerge from a material system.

When did the mind-body problem arise in philosophy? The computer revolution may have given an impetus to discussion of the issue, but it surely didn’t give birth to it. The usual answer to this question is that a distinctively modern version of the problem arises with Descartes. Despite some recent attempts by scholars to argue that Descartes is the last of the Scholastics, the traditional answer is plausible. Descartes does seem to be the first philosopher to articulate a modern-sounding concept of consciousness, and to ask how such consciousness is related to the brain. Certainly Descartes’ substance dualism sparked a huge debate in the century that followed the publication of his Meditations. The debate may have gone underground at times but in one form or another it has persisted until the present day.

Brain, by Lovelorn Poets. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Brain, by Lovelorn Poets. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.Descartes is in many ways one of us, but in reading his discussions of this issue we are immediately struck by a difference from modern debates. When Descartes and his disciples worry about the mind-body problem, they always have their eyes on theological issues; they seem to be constantly looking over their shoulders to see how the Church will react. In the period of Descartes the mind-body problem was not a freestanding, academic issue; it was intimately bound up with the issue of immortality. Descartes thought that he could ‘sell’ his philosophy to the Catholic Church by showing that his solution to the mind-body problem provided a secure basis for the Christian doctrine of immortality. Materialism, by contrast, seemed to undermine this doctrine.

The related problem of personal identity has a similar history.

Few philosophical problems prove so engaging to students today as the issue of what makes someone the same person over time. And if we ask when this problem got started in philosophy, the traditional answer still seems the right one: the first recognizably modern formulation of the problem is found in Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding. But once again we see how fundamentally the context has changed.

Today the problem of personal identity arises in part by extrapolating from recent developments in biomedical technology: philosophers famously ask what we would say about cases in which one person’s live brain has been successfully transplanted into the body of another human being. The appeal to science fiction, if not the choice of examples, goes back to Locke; Locke himself pioneered the use of such thought-experiments to test our intuitions about personal identity. But Locke’s basic motivation is quite different from that of philosophers today. Locke wants to explain how a person can survive the destruction of the body at death even if there is no persisting immaterial substance. Like Descartes he is worried about what the Church – in his case the Anglican Church – will say in response to his theory.

So the experience of reading the great philosophers of the early modern period can be a strange and disconcerting one. In one way they seem so modern: they address many of the philosophical concerns that we have today. And yet at times in reading them we seem to be in an unfamiliar world where the agenda is a theological one. We might describe the situation by saying that the seventeenth century is a Janus-faced age: with one face it looks forward to the modern world and with the other it looks back to the middle ages. For many of us that is precisely the source of its endless fascination.

The post How is the mind related to the body? appeared first on OUPblog.

June 20, 2015

Getting to know our Institutional Marketing team for Latin America

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into our offices around the globe. This week, we are excited to introduce three members of our Institutional Marketing team for Latin America. Seth, Molly, and Juan work with libraries and other institutions around the world, from setting up educational webinars to holding Library Advisory councils, from updating librarians on new journals and websites to providing them with tools to help faculty and students.

Seth Clark, Assistant Marketing Manager

What’s your favorite Spanish word?

Definitely ‘sacapuntas‘! It sounds like an angry expletive, though you’re really just saying, ‘pencil sharpener!’

What’s the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

That’d have to be a drawing from my daughter, Gracen. It’s my four year-old’s rendition of the Cary OUP office (which she thinks is a skyscraper), made complete with a lovely four-story rose. Maybe someday she’ll be added to Benezit!

Seth Clark. Photo used with permission.

Seth Clark. Photo used with permission.If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

I’d probably go back to where I started: the classroom. I taught high school Spanish for six years, working with some really awesome students and teachers.

What is your favorite food?

I’m addicted to tacos al pastor. There’s a little taquería where I live in North Carolina that has, hands down, the best tacos al pastor I’ve ever had. I also love dark beer, if you can count that as a food (yeast, right?).

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

I’ll be checking the click-through rates of our Facebook ads that are running in Latin America. We reach about one million university students each month, highlighting content from OUP’s online resources. Last month, for example, 5,410 students clicked on an ad highlighting Marriage quotes in the Oxford Dictionary of Humorous Quotations, Fourth edition..

Molly Hansen, Marketing Associate

What’s your favorite word in Portuguese?

Ótimo (awesome)—I find myself saying this instead of awesome sometimes. It’s a word with a lot of energy.

Molly Hansen. Photo used with permission.

Molly Hansen. Photo used with permission.What’s the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

A set of three cups I lovingly call “Bad Cups” that I made in a clay casting class in college. The three are either misshapen or poorly glazed and are now stuck together after being stacked for so long. My little (out)casts! The second strangest thing on my desk is a red feather boa.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

Fulfilling my childhood dream of being a dolphin trainer. Or starring in the next Star Wars movie.

What’s your favorite food?

Grilled cheese from a churrascaria—a slab of mozzarella or other kinds of cheese seared and then sliced on the table. The most heavenly melted cheese you can imagine! Even better when washed down with a caipirinha.

Juan Fuentes, Marketing Associate

What is your favorite word?

My favorite word is abacaxí, meaning pineapple in Portuguese.

Juan Fuentes. Photo used with permission

Juan Fuentes. Photo used with permissionWhat is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

A miniature gavel/neck massager. It’s an interesting rolling wooden instrument to release tension. My co-worker Mackenzie Warren gifted to me. Ha!

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

Broadcast journalism (I’m addicted to the news!) or law school.

What is your favorite food?

Chiles en nogada, which consists of poblano chiles filled with picadillo (a mixture usually filled with shredded meat, fruits and spices) topped with walnut-based cream sauce, called nogada, and pomegranate seeds, giving the three colors of the Mexican flag. ¡Viva México!

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q &A?

Ordering OUP swag, flyers and preparing for Feria Internacional del Libro de Buenos Aires/International Book Fair of Buenos Aires!

Image Credit: “Tulum” by Ashley Halsey Hemingway. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Getting to know our Institutional Marketing team for Latin America appeared first on OUPblog.

Murders in rural Mississippi: remembering tragedies of the Civil Rights Movement

On 21st June, Mt. Zion United Methodist Church in Philadelphia, Mississippi will hold its fifty-first memorial service for three young civil rights workers murdered by the Ku Klux Klan at the start of the Freedom Summer. Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner were activists who planned to create a voting rights school at the church, located in rural Neshoba County. This year’s service, while not the same highly visible event as last year’s half century remembrance, is nevertheless the centerpiece of a tradition that has continued uninterrupted since the men were killed in 1964. The three men — two white, one black — became martyrs to their cause, while the church was burned to the ground and five of its members were brutally beaten by masked men. Mt. Zion Church goers remember the deaths of the young men, as well as their goal, unrealized even now, of full and equal voting rights for black Americans.

These rural Mississippians, like African Americans elsewhere, recognize that their full participation in voting has been recently compromised by the Supreme Court’s 2013 decision to remove certain protections from the 1965 Voting Rights Act — a symbol of the goals of the three men who were killed. The basis for the Court’s decision, according to its Chief Justice, is that “times have changed” and blacks no longer need federal surveillance, even as white legislative gerrymandering continues to dilute the black vote. For most white Americans this change to the Voting Rights Act may seem relatively inconsequential, but for the people at Mt. Zion and other activists, the struggle over the vote has had a long and difficult history. The differences in perspective on this matter illustrate the often contrasting ways blacks and whites remember the past and further, how collective memory can affect decisions in the present.

This voting change appears to be one of the consequences of what dissenting Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg referred to as an example of second-generation Jim Crow barriers. Perhaps it has taken this long for the aesthetic achievements of the Civil Rights Movement, namely the appearance of highly-placed blacks in national politics, industry, sports, and entertainment, to show in stark relief the unresolved legacy of the old Jim Crow among the other 99 percent. In most areas of life, like health care, job opportunities, family formation, educational equality, and especially justice and policing, black Americans stand in inequitable need. But white people who control the distribution of such goods cannot be expected to remember what they do not know, or never knew, about segregation and discrimination. They do not know, for example, that when older members at Mt. Zion Church were asked about what troubled them most about the old Jim Crow, they spoke most often of what was less visible, of the hurt that came from the rejection of their common humanity, revealed in not being addressed by their given names, of being turned away from worship in churches whose doors were purportedly open to everyone. Being depersonalized is a hurt hard to expunge.

A missing persons poster created by the FBI in 1964 shows the photographs of victims Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A missing persons poster created by the FBI in 1964 shows the photographs of victims Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Mt. Zion Church members, as well as their urban kin, remember important events of the past differently from whites, and that difference has significance for the entire nation. Virtually all African Americans remember that their slave relatives were paid nothing to build the industries, farms, trade, monuments, and educational and other institutions that made the country the most prosperous in the world. Yet most white Americans feel disconnected from that history: “I owned no slaves”; “I was not even born, so I can’t be responsible.” The implications of these differing views of the past contribute to misunderstandings that too often erupt into violence in our streets.

No single racial community can effect change by itself. Street violence won’t end by equipping the police with cameras and teaching them new techniques for working in high crime areas. The power of collective memory is such that it requires new and creative ways to narrow the divide between black and white communities. The American Dilemma, that discrepancy between who we think we are and how we really behave toward each other, endures, preserved in our different collective memories. For years, the American historical record has marginalized black memory, or as philosopher Paul Ricoeur has said, we have privileged history—as the narrative written down and remembered—over memory. In this version of the record, early America was inhabited by moral, law abiding people, whose color did not need to be mentioned since in the dominant imagination they were all the same color. Anything new inserted into this account occurred only after careful consideration by the record keepers themselves. The contributions of black Americans require a more inclusive narrative: collecting stories from black communities is the beginning of national acceptance of black people as historical actors.

It is a large task. In the 1990s, President Clinton’s Commission on Race brought together leaders of both races, who were advised to gather local people in town meeting-like sessions to hear their concerns. With no fixed agenda, participants could address a broad range of issues, including affordable housing, the needs of single mothers, the equal administration of justice, and the nurturing of leaders and group advocates. Eventually energies flagged, however, and Clinton’s effort disappeared from the national scene.

The racially charged encounters that happen in our streets, our jails, our schools, and other social institutions owe much to our failure to achieve reconciliation. Reconciliation requires the admission (or at least the awareness) of complicity by one side and a willingness to forgive on the other. The observance of a national “Day of Reconciliation,” a public historical event with symbolism and ritual similar to the commemorative service at Mt. Zion Church, could be one way to open the conversation between two communities long estranged and help bridge the gap between narrative history and collective memories. Some white residents of Neshoba County wonder aloud each year why the members of Mt. Zion Methodist Church “just don’t get over it.” When the time comes that collective memory is understood in the light of a more comprehensive narrative history, perhaps they will no longer feel the need to raise the question.

Featured image: Civil right workers Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner’s Ford station wagon (pictured) was located in northeastern Neshoba County, Mississippi on Highway 21. The three workers disappeared on June 21, 1964, prompting in a massive federal search for the men. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Murders in rural Mississippi: remembering tragedies of the Civil Rights Movement appeared first on OUPblog.

The role of logic in philosophy: A Q&A with Elijah Millgram

Elijah Millgram, author of The Great Endarkenment, sits down with Svantje Guinebert, of the University of Bremen, to answer his questions and discuss the role of logic in philosophy.

Svantje Guinebert: Elijah, on occasions, you’ve said that logic, at least the logic that most philosophers are taught, is stale science, and that it’s getting in the way of philosophers learning about newer developments. But surely logic is important for philosophers. Would you like to speak to the role of logic in philosophy?

Elijah Millgram: For analytic philosophy, logic has become the name for a branch of mathematics whose introductory courses are conventionally taught in philosophy departments. And maybe it still pays to have our undergraduates take these classes; Stanley Cavell once said that it’s a sociological fact about analytic philosophy that there is one course that you know every analytic philosopher has taken, and that’s the Introduction to Deductive Logic. It’s the one piece of shared culture; they all know how to read a backwards E.

But, yes, I think it’s stale science and I’m not sure how much further we philosophers want to invest in this.

However, there is an older sense of logic which maybe corresponds to our notion of philosophy of logic. In this older sense of logic, the question is “what counts as a good argument? What counts as a good inference?” And sometimes it answers the question of how to think. Logic in that sense, which is not necessarily the same as the branch of mathematics, seems to me… well, let me say this with an analogy. Ethics is to applied ethics as logic in this sense, or philosophy of logic, is to all the rest of philosophy. All the rest of philosophy is applied logic.

Svantje Guinebert: What do you mean by “applied logic,” and how does it turn out to be philosophy?

Elijah Millgram: You actually see this in the history of different philosophical traditions. Each philosophical tradition evolves a view of what a successful argument is. And that view of argumentation shapes the content of that tradition. This is one of the reasons I’m interested in the theory of rationality; the deepest changes arise out of changes in your views about logic, so construed. You get enormous leverage. When you change your philosophical views about argument, all the other philosophy follows suit: moral philosophy, metaphysics, epistemology; it’s all just applied logic. But not logic in the sense of what is taught in these math classes; it’s applied philosophical logic.

Svantje Guinebert: If much of philosophy is, as you’re putting it, applied logic, what do you want to say about the content of philosophy? For instance, why is ethics a part of philosophy?

Elijah Millgram: If you think about some of the questions that philosophers traditionally address themselves to—such as, How should I live? What is it like to be an upstanding, ethically responsible citizen?—these questions predate philosophy, and in our own past and in other cultures they are subjects of wisdom literatures. And every culture has a wisdom literature. For example, in the Old Testament, you find books like Ecclesiastes and Job; I suppose that the ancient Greeks produced this sort of wisdom literature also—maybe some of the authors were sophists. What makes philosophy different from that? Not the subject matter it covers.

Svantje Guinebert: So philosophy shares its ideas with other intellectual enterprises?

Elijah Millgram: Certainly there’s overlap. But philosophy starts when Socrates comes to people who have these views, and maybe very wise people have these views, and he says: “That’s fine, but give me an argument.” If you had to characterize philosophy not in terms of its subject matter, well, remember that Aristotle says there are four causes for a substance: there is the formal cause, the efficient cause, the final cause and the material cause. In the toy example that we serve up in our classes, at the beginning—okay, it’s a little bit misleading, but don’t worry about that now—if you’re thinking about a sculpture, the formal cause will be the design of the sculpture, the efficient cause will be the sculptor, and the final cause will be his commission, or perhaps that the sculpture will be put in a temple. And then there is the material cause, which is the bronze or the wood or the marble of which the sculpture is made.

Philosophy is characterized by this: the material cause of philosophy is argument. Argument is the clay you work in — that’s the skill you’re trying to teach your students. What matters is the ideas, but the ideas have to be executed in this medium. And they‘re learning to produce arguments such that, when you put them in a kiln, they won’t crack. That requires a throughgoing—and hard—mastery or command of the medium.

Svantje Guinebert: And so logic is first philosophy because…

Elijah Millgram: Yes, because when you change the medium, the ideas are executed differently, in about the way that the still life comes out differently in oils and charcoal. But also because the possibilities of the new medium give you new ideas.

Featured image credit: Chichen Itza Yucatan Pyramids, by darvinsantos. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The role of logic in philosophy: A Q&A with Elijah Millgram appeared first on OUPblog.

June 19, 2015

Sweetness around the world

No matter where in the world you go, pastries are a universal treat. From Turkish baklava to Italian cannolis, French croissants to American cherry pie, these morsels of sweetness are a culinary tradition that knows no borders. Whether you’re boarding an overseas flight or hanging around the neighborhood, we’ve hand-picked several pastry shops from the Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets to add to your personal itinerary.

Image Credit: “Sweet dreams” by poolie. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Sweetness around the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Palliative care around the world

With a failing NHS and an ageing population in Britain, palliative care is a topic currently at the forefront of healthcare debate. Whether to abandon treatment in favour of palliation, is a challenging decision with profound implications for end-of-life care.

Worldwide, palliative care is an increasingly significant field as less-economically developed countries attempt to remedy short-comings in systems of care, to ensure the dying receive the support they and their families need. This interactive map takes the reader on a brief journey around the world highlighting some of the recent and past innovations in the field.

Headline image credit: Group of mature male friends sitting together on bench. © Yuri via iStock.

The post Palliative care around the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers