Oxford University Press's Blog, page 646

July 8, 2015

Global warming and clean energy in Asia

The year 1896 was “a very good year” for many reasons. It was in that year that Puccini’s Opera, La Bohème, premiered, gold was discovered in the Yukon, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average finished its first year at around 41. But perhaps closer to our subject, two other events stand out. Firstly, Henry Ford introduced the gasoline-fueled automobile to America and, secondly, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius suggested that a greenhouse-like warming of the planet could result from increasing atmospheric CO2. Thus, the possibility that the industrial revolution would ultimately become incompatible with the physical environment was first envisioned.

Modern industry is foundational for contemporary society. Yet, its dependence upon fossil fuels, primarily, and upon other chemicals, secondarily, threatens to destroy that very same society. One should note, at the outset, that those industrial processes do not so much create greenhouse gases, as they are termed, but rather release them. In fact, the term “fossil fuels” originates in the idea that they – petroleum, coal, and natural gas – originate in the decayed remains of plants and animals that lived long ago. Although not universally accepted, this theory originates with the 18th century Russian chemist Mikhail Lomonosov, who first argued: “Rock oil originates as tiny bodies of animals buried in the sediments which, under the influence of increased temperature and pressure acting during an unimaginable long period of time, transform into rock oil.”

Thus, global warming threatens to restore our planet to an ancient equilibrium – an equilibrium that was home to tropical plants and dinosaurs, but not to man.

It is because of this integration with our economic system that the problem is so complex. And, in particular, because of the way our economic system incorporates so much of society, climate change issues are, indeed, issues for every man and woman on the planet.

As the chemist Nathan Lewis has said: “The currency of the world is not the dollar, it’s the joule” (Lewis, Nathan S. (2007), “Powering the Planet”, Engineering and Science). Thus, the value in modern industrial processes is that they harness energy, focusing the transformational power of machines into production. Unfortunately, although there are numerous sources of energy which are not accompanied by the emission of greenhouse gases – solar and wind – the technology of transmission and storage of energy is still in its infancy.

Image: “Mulan Wind Farm”, by Land Rover Our Planet. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

Image: “Mulan Wind Farm”, by Land Rover Our Planet. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.Fossil fuels are simply one of the most efficient forms of stored energy. They are also a convenient form in which to transport energy to the places where it is needed.

Fossil fuels are integrated not only into our economy, but into our society as well. The automobile, for example, is as much a cultural icon as it is a means of transportation. Thus, the economic consequences of energy production, use, storage, and transmission, as well as any attempts to control these processes, will reflect in the political arena, in daily life, on Wall Street, and on the global economy through a plethora of intricate, often interlocking, mechanisms.

Western society has developed itself, largely oblivious to concerns of climatic change. The benefits in terms of quality of life are manifest, and they have become, arguably, the West’s primary export to the rest of the world. The, so-called, under-developed world has bought-in to the program and now seeks to align itself, economically, if not culturally, with the West. Yet, just as this dream begins to appear real, the limitations imposed by global warming are becoming apparent.

Figure 1. Image Credit: “Annual GDP Growth Rate for China, India and U.S.”, used with permission from the authors. Data Source: The World Bank; National Bureau of Statistics of China; Central Statistics Office of India; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Figure 1. Image Credit: “Annual GDP Growth Rate for China, India and U.S.”, used with permission from the authors. Data Source: The World Bank; National Bureau of Statistics of China; Central Statistics Office of India; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.China, in particular, and Asia, in general, has stepped up to the plate, as it were. GDP growth rates in Asia have been in the high single digits for decades, double or triple that found in the US. In Figure 1, we can see that China and India, representing a significant portion of the world’s population, are growing rapidly.

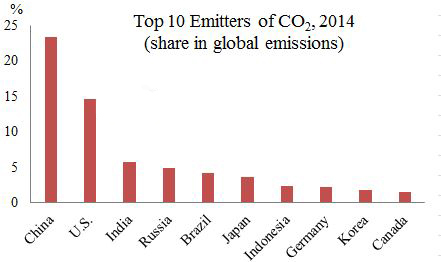

Yet, this growth has come with an environmental cost. As outlined earlier, the expenditure of energy, largely derived from fossil fuels, is matching Asia’s economic growth. Figure 2 shows individual country’s CO2 emmissions as a percentage of global CO2 emmissions.

Figure 2. Image Credit: “Top Ten Emitters of Co2, 2014″, used with permission from the authors. Data © Statista 2015.

Figure 2. Image Credit: “Top Ten Emitters of Co2, 2014″, used with permission from the authors. Data © Statista 2015.Obviously, the West cannot simply say “slow down” to Asia. This is a non-starter. Yet, one cannot escape the facts. Global warming will, ultimately, through its devastating effects on global systems, destroy the very economic engine that fuels Asian (and Western) development.

The challenge of Asia is to figure out how to maintain its development, while addressing the issues surrounding greenhouse emissions.

This may not be as farfetched as it sounds. Most of Western development took place in a crude industrial environment. The internal combustion engine, for example, is largely a nineteenth century technology, although it was conceived of earlier.

Yet, from modern computers to advanced materials, Asia today has the advantage of a century of innovation and technological progress. It need not wade through the swamp of carbureted engines and untreated exhausts that the West passed through. Nowadays, computer-controlled fuel injection is available and catalytic converters reduce noxious emissions. But there are also advances in solar panels and wind generation, computer control of electrical networks, etc. New “green” technologies are not only beneficial to the environment; they are also an important economic engine in and of themselves, providing entrepreneurial opportunity and jobs to those nations which adopt them.

Asia is well-aware of this. China has been a “high speed” investor in clean energy since 2004. In fact, according to recent data from The Bloomberg New Energy Finance Report, China leads the world in renewable energy investment, spending a total of $89.5 billion on wind, solar, and other renewable projects in 2014 alone. Thus, rather than trying to contain Asian growth, sound market principles suggest that exactly the opposite strategy may encompass the best hope of finding a solution to the problem of global warming.

Featured image: “#431 Global warming get warmer houses”, by Mikael Miettinen. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Global warming and clean energy in Asia appeared first on OUPblog.

July 7, 2015

All life is worth saving

Just as in Clarence Darrow’s day, the death penalty continues to be practiced in many American states. Yet around the world, the majority of nations no longer executes their prisoners, showing increasing support for the abolition of capital punishment. Recently, in December 2014, when the United Nations General Assembly introduced a resolution calling for an international moratorium on the use of the death penalty, a record 117 countries voted in favor of abolition, while only 38 nations, including the United States, voted against it. Indeed, falling just behind China, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, the United States is recorded to have the fifth highest rate of execution worldwide.

Since Jamestown settlers first executed Captain George Kendall in 1607, jurisdictions across the United States have approved the execution of approximately 16,000 people by various methods, including hanging, firing squads, gas chambers, electric chairs, and lethal injection. As these executions continued throughout American history, many prominent abolitionists have raised their voices against capital punishment, both in the past and the present. Dr. Benjamin Rush, an eminent physician, author, and civic leader who signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776, was an early advocate for abolishing the death penalty, while many of the country’s founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, favored limitations on the practice. Most recently, during the twentieth century, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, and author Sister Helen Prejean all emerged as outspoken opponents of capital punishment.

Over the course of 400 years, the popularity of the death penalty has fluctuated, with some states abandoning their use of capital punishment earlier than others. In the mid-1800s, death penalty abolitionists achieved some success, thanks largely to societal changes that included prison reform movements, religious revivals, an influx of new immigrants, and the rise of the anti-slavery movement. People interested in these issues, however disparate, found in each other a common purpose, arguing that the use of capital punishment reflected how those in power treated the poor and powerless.

Falling just behind China, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, the United States is recorded to have the fifth highest rate of execution worldwide.

In 1847, Michigan became the first state to abolish capital punishment in the United States. Like some other states, Michigan had gradually been limiting its use of the death penalty in the preceding decades, and by the 1840s, its legislature featured many reform-minded lawmakers. Rhode Island subsequently abolished the death penalty in 1852 and Wisconsin followed suit in 1853, prohibiting capital punishment for all crimes.

Throughout different abolition periods, such as the early 1900s and the mid-twentieth century, opponents of capital punishment have raised a variety of arguments against the practice. Many question whether the death penalty serves any valid purpose, suggesting it does no more to deter crime than the threat of imprisonment. Others reason that the death penalty is inhumane and therefore inconsistent with religious principles. Most importantly, many abolitionists have highlighted the obvious fallibility of a system based on human juries and judges. Indeed, this argument has gained clout in modern times, as scientific breakthroughs in DNA testing and investigative techniques have led to the discovery of innocent people on death row. The question of race–whether the death penalty can be applied fairly and without racial bias–has also emerged alongside concerns that capital punishment targets society’s most disadvantaged.

An important turning point arrived in the 1960s and 1970s, when the Supreme Court of the United States began to address the practice as a constitutional issue. In Furman v. Georgia (1972), Supreme Court Justices found that existing procedures for the death penalty violated the United States Constitution because of the broad discretion afforded to jurors, who were capable of arbitrary and racially discriminatory decisions.

Given the worldwide trend of countries prohibiting capital punishment, many observers predicted the case would end the death penalty in the United States. However, as part of a backlash against the Supreme Court, several state legislatures renewed their death penalty laws; and in 1976, the Supreme Court upheld some of these new procedures, reintroducing capital punishment as common practice and starting a new era for the practice.

Over the following decade, the Supreme Court evaluated another broad attack on capital punishment in McCleskey v. Kemp, in which Warren McCleskey’s attorneys presented statistical evidence illustrating the racial bias of the justice system. The Supreme Court, rejecting this claim, thereby affirmed that any changes to death penalty laws would have to established through political processes.

Image: “Group of people holding signs at a death penalty protest” by OBS onthemove. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image: “Group of people holding signs at a death penalty protest” by OBS onthemove. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Ever since the United States resumed executions after 1976, nationwide jurisdictions have sent approximately 1,400 people to their deaths. In the modern era, 1999 was notable for the highest number of executions, with 98 death row inmates executed that year. While this number dropped to 39 in 2013, more than 3,000 people remain on death row across the country.

Recently, however, activists have found some success in illuminating the drawbacks of the death penalty through educational efforts. During the past decade, seven states have repealed the practice of sentencing prisoners to death, including Illinois, the same state in which Clarence Darrow infamously defended murderers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb.

Presently, the federal government, along with 31 states, has upheld the use of capital punishment, whereas only 19 states (and the District of Columbia) have prohibited it. A Gallup poll in winter 2013 showed that the death penalty continues to be popular among American citizens—at least in theory—with up to 60 percent indicating their support for capital punishment in the case of convicted murderers. For some, the death penalty continues to serve as a fitting punishment and just retribution for society; for others, it continues to be justified by religion. Other advocates even assert that the death penalty may deter crime. Still, when asked to make a choice between capital punishment and life imprisonment without parole, support for capital punishment is shown to drop, as citizens are split equally between the two options.

In the past year alone, the debate surrounding the death penalty has been inflamed by botched executions, notably in the Arizona execution of Joseph Wood, who took two hours to die from lethal injection. There are also increasing concerns about the expense of the modern death penalty for taxpayers. In Texas, for example, the cost of a death penalty case today is thought to be nearly three times more expensive than imprisoning someone in maximum security for 40 years.

Charged and complex, the public debate surrounding the death penalty has once again been brought to the fore, even spilling over into international territory as European manufacturers discontinue their supply of lethal drugs to the United States. Because the death penalty in America is largely a state issue, the success of abolition efforts will most likely be gradual. However, the recent global trend against capital punishment has been encouraging to those who, like Clarence Darrow, believe that both logic and humanity demand an end to the practice of killing prisoners.

A previous version of this article appeared in the Old Vic program for the play Clarence Darrow (starring Kevin Spacey).

Featured Image: “Red Hats Execution Chamber” by Lee Honeycutt. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post All life is worth saving appeared first on OUPblog.

Happy 120th birthday BBC Proms

In celebration of The BBC Proms 120th anniversary we have created a comprehensive reading list of books, journals, and online resources that celebrates the eight- week British summer season of orchestral music, live performances, and late-night music and poetry.

William Walton Edition Complete Set Composer: William Walton & General Editor: David Lloyd-Jones.

A collected edition of the works of one of England’s finest and best-loved composers. A definitive and fully practical edition, based on the form in which the composer ultimately wished his music to be performed, and including in some cases both original and revised versions.

Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast will feature at the First Night of the Proms on 17th July.

Hear, Listen, Play! by Lucy Green.

Based on over 15 years’ original and world-renowned research by the author and her research teams, the book discusses how popular musicians learn in the informal realm, and then applies many aspects of their learning practices to three main areas within music education.

Read Brett Clement’s article A New Lydian Theory for Frank Zappa’s Modal Music from the Music Theory Spectrum journal.

Find out how children in schools across the UK have been working on their own responses to music by Beethoven and others at the Ten Piece Prom on 18th July.

Out of Time by Julian Johnson

If all music since 1600 is modern music, the similarities between Monteverdi and Schoenberg, Bach and Stravinsky, or Beethoven and Boulez, become far more significant than their obvious differences. Johnson elaborates this idea in relation to three related areas of experience – temporality, history and memory; space, place and technology; language, the body, and sound. Read the free introduction from Out of Time, available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

If all music since 1600 is modern music, the similarities between Monteverdi and Schoenberg, Bach and Stravinsky, or Beethoven and Boulez, become far more significant than their obvious differences. Johnson elaborates this idea in relation to three related areas of experience – temporality, history and memory; space, place and technology; language, the body, and sound. Read the free introduction from Out of Time, available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

Karen Leeder will be giving a talk on the poetry that inspired Beethoven at Proms Extra on the 24th July.

Bollywood Sounds by Jayson Beaster-Jones.

The first monograph to provide a long-term historical insight into Hindi film songs, and their musical and cinematic conventions, in ways that will appeal both to scholars and newcomers to Indian cinema. Read chapter one from Bollywood Sounds, available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

In celebration of 50 years of Asian programmes on the BBC, music from Bollywood will be featured at Prom 8 on 22nd July.

Anything Goes by Ethan Mordden

From “ballad opera” to burlesque, from Fiddler on the Roof to Rent, the history and lore of the musical unfolds here in a performance worthy of a standing ovation. Chapter one from Anything Goes is available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

From “ballad opera” to burlesque, from Fiddler on the Roof to Rent, the history and lore of the musical unfolds here in a performance worthy of a standing ovation. Chapter one from Anything Goes is available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

Read Paul Wittke’s article The American Musical Theater (with an Aside on Popular Music) and David Brodbeck’s article A Tale of Two Brothers: Behind the Scenes of Goldmark’s First Opera, both from The Musical Quarterly journal.

Prom 11: Fiddler on the Roof will be performed on the 25th July.

Ezra Pound: Poet by A. David Moody

This second volume of A. David Moody’s full-scale portrait, covering Ezra Pound’s middle years, weaves together the illuminating story of his life, his achievement as a poet and a composer, and his one-man crusade for economic justice.

Read the poem The Shyness of Beauty by Laurence Binyon, a contemporary of Pound, from the Music & Letters journal.

Poets Jo Shapcott and Sean O’Brien discuss Pound’s poetry at Proms Extra on 29th July.

Arranging Gershwin by Ryan Banagale

Ryan Banagale approaches George Gershwin’s iconic piece Rhapsody in Blue, not as a composition but as an arrangement — a status it has in many ways held since its inception in 1924, yet one unconsidered until now. Read chapter one from Arranging Gershwin available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

Ryan Banagale approaches George Gershwin’s iconic piece Rhapsody in Blue, not as a composition but as an arrangement — a status it has in many ways held since its inception in 1924, yet one unconsidered until now. Read chapter one from Arranging Gershwin available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

Hear Rhapsody in Blue at Prom 32 on 9th August.

Nilsson by Alyn Shipton

In this first ever full-length biography, Alyn Shipton traces Nilsson’s life from his Brooklyn childhood to his Los Angeles adolescence and his gradual emergence as a uniquely talented singer-songwriter. With interviews from friends, family, and associates, and material drawn from an unfinished autobiography, Shipton probes beneath the enigma to discover the real Harry Nilsson.

Alyn Shipton will be discussing swing and its influences at BBC Proms Extra on 11th August.

Some of These Days by James Donald

This book extends beyond pure dual biography to recreate the rich community of actors, architects, poets, directors, and musicians who interacted with—and were influenced by—each other.

Read Mark Burford’s article Mahalia Jackson Meets the Wise Men: Defining Jazz at the Music Inn from The Musical Quarterly journal, and find out more about the Jazz tradition and its roots on Oxford Bibliographies online.

The BBC will be showcasing current UK jazz talent at Prom 35 on 11th August.

Conan Doyle by Douglas Kerr

From the early stories, to the great popular triumphs of the Sherlock Holmes tales and the Professor Challenger adventures, the ambitious historical fiction, the campaigns against injustice, and the Spiritualist writings of his later years, Conan Doyle produced a wealth of narratives. He had a worldwide reputation and was one of the most popular authors of the age. Read the free introduction from Conan Doyle, available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

From the early stories, to the great popular triumphs of the Sherlock Holmes tales and the Professor Challenger adventures, the ambitious historical fiction, the campaigns against injustice, and the Spiritualist writings of his later years, Conan Doyle produced a wealth of narratives. He had a worldwide reputation and was one of the most popular authors of the age. Read the free introduction from Conan Doyle, available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

The BBC will pay homage to the world of Sherlock Holmes at Prom 41 on 16th August.

The Oxford Handbook of Sondheim Studies edited by Robert Gordon

This collection of never-before published essays addresses issues of artistic method and musico-dramaturgical form, while at the same time offering close readings of individual shows from a variety of analytical perspectives. Read a free chapter from the Handbook, ‘Sondheim’s Genius’, available exclusively on Oxford Handbooks Online.

Sondheim’s renowned works will be performed at Proms Chamber Music 5 on 17th August.

The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume I: 1695-1717 by Richard D. P. Jones

The first volume of a two-volume study of the music of J. S. Bach, covers the earlier part of his composing career, 1695-1717. By studying the music chronologically, a coherent picture of the composer’s creative development emerges, drawing together all the strands of the individual repertoires (e.g. the cantatas, the organ music, keyboard music).

Find out why Johann Sebastian Bach is regarded as one of the greatest composers in the history of European art music on Oxford Bibliographies online, and read David Schulenberg’s article Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: a tercentenary assessment from the Early Music journal.

The BBC Singers and the Academy of Ancient Music will celebrate Bach at Prom 48 on the 21st August.

Music from OUP featured at the Proms

Belshazzar’s Feast edited by Steuart Bedford

Belshazzar’s Feast has been featured in an amazing 32 Proms. The earliest proms performance of this work was in September 1946, fifteen years after its world premiere at the Leeds Festival in October 1931. The first proms performance was conducted by Adrian Boult, who also conducted the first London performance of Belshazzar’s Feast with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in November 1931.

Symphony No. 2 edited by David Russell Hulme

Walton Symphony No 2 has been featured in 4 Proms. The earliest proms performance was in August 1961, just a year after its composition. This proms premiere was conducted by Malcolm Sargent, who was the chief conductor of the proms at the time.

Prelude and Fugue: The Spitfire edited by David Lloyd-Jones and Concerto for Violin composed by Ralph Vaughan Williams

The first ever proms performance for both Walton’s Prelude and Fugue: The Spitfire and Vaughan Williams’ Concerto for Violin (also known as Concerto Accademico).

Find out more about Orchestral Music from Oxford Bibliographies online.

Do you have any Proms reading materials that you think should be added to this reading list? Let us know in the comments below.

Featured image credit: BBC Prom by Paul Hudson. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Happy 120th birthday BBC Proms appeared first on OUPblog.

A tiny instrument with a tremendous history: the piccolo

Although often overlooked, the piccolo is an important part of the woodwind instrument family. This high-pitched petite woodwind packs a huge punch. Historically, the piccolo had no keys, but over the years, it has transformed into an instrument similar in fingering and form to the flute. It still serves as a unique asset to the woodwinds.

The piccolo is about half the size of the flute.

Other than size, the biggest difference between the two instruments is that the piccolo is pitched one octave higher.

Unlike the flute, piccolos can be made out of plastic, wood, or metal.

The piccolo was often referred to as the “petite flute” or “flautino” – but so were flageolet or small recorders, sometimes making it difficult to determine what instrument that composer had in mind.

In Italian, ‘piccolo’ is used as an adjective to describe various instruments that are the smallest and highest in pitch of their type. These include the violin piccolo, piccolo clarinet, and piccolo timpani.

Man in uniform playing piccolo. Photo by Bengt Nyman. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Man in uniform playing piccolo. Photo by Bengt Nyman. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Some of the most famous piccolo parts can be found in Beethoven’s Egmont ov and in John Phillip Sousa’s march The Stars and Stripes Forever.

The piccolo was originally designed for military bands to make the flute parts more prominent.

Piccolos were once available in the key of D♭ but are currently only sold in the key of C.

The piccolo can often be confused with the fife, which is similar in form but creates a louder, shriller sound.

The piccolo is the most highly pitched instrument of all the woodwinds.

Featured Image: Philharmonic Orchestra of Jalisco by Pedro Sánchez. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A tiny instrument with a tremendous history: the piccolo appeared first on OUPblog.

Jeremy Phillips speaks to the Oxford Law Vox

“It wasn’t seen, it was absolutely invisible. There was not a single university in the country that offered it as an undergraduate course. There was no textbook in the subject, and there was only one university which offered it even as a postgraduate option.”

In the second of Oxford’s new series of Law Vox podcasts, Jeremy Phillips, editor of Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, describes how the field of intellectual property law looked when he started his illustrious intellectual property law career. Jeremy’s conversation with Law Vox also addresses how intellectual property evolved and grew to encompass many different features. He uses the analogy of Tracey Emin’s bed to explain how intellectual property touches many aspects of our lives without us consciously realising it:

“Tracey Emin’s bed is something which is so familiar. We all have a bed, which we don’t necessarily make every day, and we all have the typical mess which hangs around it. We don’t really see in detail, what it is that we leave behind us when we get dressed and go to work, because it’s so much taken for granted. That is very much the case with intellectual property – it so pervades everything we do. Every time you go to the shops, you’re making a decision. Shall I buy this product or that product? You’re actually relying upon years of patient work by intellectual property practitioners, in protecting brands, in patenting products, in registering designs, or containers and packaging, and lawyers who then license the distribution of products.”

As the conversation moves on Jeremy discusses topics which address how intellectual property interacts with the commercial world, and in talking about how the world of copyright in books, articles and literature forms a large part of this. Jeremy delineates copyright law’s parameters, and points to how intellectual property is a champion of creativity:

“Copyright doesn’t protect ideas, it doesn’t protect facts, it only protects the way in which you express them. If somebody comes up with an interesting scientific theory, and writes it down and publishes an article it’s there for everybody. The only thing they can’t do is to copy it, in the way in which it’s been expressed, but the idea there is for everybody to use. Intellectual property emancipates ideas, and encourages people to disclose them.”

“Wayne Rooney”, by Austin Osuide. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Wayne Rooney”, by Austin Osuide. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In Jeremy’s discussion of trade marks, he uses the example of Wayne Rooney to show how trademarks are distinguishable from patents and copyright, and how trademarks frequently extend to areas that are decidedly non-creative on the part of the individual registering the trademark:

“Most trademark rights have nothing to do with intellectual property at all because they’re not to do with protecting the fruits of the creation of the individual. If you happen to be born with a name like Wayne Rooney, and register ‘Wayne Rooney’ as a trade mark, you can license your name in respect of sports products and all sorts of other things and make a lot of money out of it, but Wayne Rooney did not name himself. If he had any particular intellectual power it certainly didn’t go into creating himself. The basis upon which trademarks are protected is only that they enable ordinary people like you and me, consumers, to distinguish one lot of goods from another.”

Turning to the future, Jeremy describes what interesting questions might come up in intellectual property in the next few years that he is keeping an eye on, including dispute resolution in intellectual property:

“Well, it’s like asking me which of my children I love the best isn’t it? I love them all for their different qualities, and it’d be invidious to pick one. I will give you a couple of choices and I’ll tell you what they are because they don’t involve specific subject areas. One is the dispute resolution issue. If you have somebody who says: ‘This is my intellectual property right and you’re infringing it’, then somebody else who says, ‘I’m not infringing it,’ then whether it’s a patent or a trade mark or a design, it doesn’t matter, you’ve got a potential piece of litigation and I feel that a mature system like the intellectual property law system where we’ve had laws now for a long time, and the way in which the courts work is quite predictable should produce a situation in which cases can usually be solved before they go to court.”

If you want to learn more about what Jeremy Phillips thinks about the future of intellectual property law, you can listen to the full conversation on Soundcloud.

Featured image: ‘Headphones’, by kev-shine. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Jeremy Phillips speaks to the Oxford Law Vox appeared first on OUPblog.

July 6, 2015

The continuing benefits (and costs) of the Giving Pledge

The recent news about charitable contributions in the United States has been encouraging. The Giving Pledge, sponsored by Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, Jr., recently announced that another group of billionaires committed to leave a majority of their wealth to charity. Among these new Giving Pledgers are Judith Faulkner, founder of Epic Systems; Hamdi Ulukaya, founder of Chobani Yogurt; and Brad Keywell, a co-founder of Groupon. Moreover, Giving USA reported that charitable donations in 2014 reached an all-time high of $358 billion.

There is a connection between these two events. The Buffett-Gates Giving Pledge, augmented by a rising stock market, has undoubtedly stimulated charitable contributions, not just by Pledgers, but by individuals of more modest means. The Giving Pledge has reminded Americans of all income levels of the importance of a vibrant nonprofit sector, supported by robust charitable contributions.

However, the admirable benefits of the Giving Pledge should not obscure two important consequences resulting from increased charitable donations. First, the Giving Pledge erodes the federal tax base, particularly the federal estate tax base. Second, the Giving Pledge can be satisfied by gifts and bequests to family-controlled private foundations. While some private foundations are commendable institutions pursuing important charitable objectives, others are not.

Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, Sr. have been vigorous supporters of the federal estate tax. In this sense, there is considerable irony in the fact that Giving Pledgers avoid all federal estate taxes on the money they leave to charity. Indeed, much of the Giving Pledgers’ wealth consists of appreciated stock for which they have paid no federal income tax.

Mr. Buffett and Mr. Gates, Sr. have spoken eloquently of the need for wealthy individuals to repay the public for the government services that made their wealth possible. A Giving Pledger (or other charitable donor) who leaves appreciated stock tax-free to charity makes no such repayment.

Moreover, the Giving Pledge can be satisfied by a gift or bequest to a family-controlled private foundation. Many of these foundations, like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, are commendable institutions pursuing important causes. However, other family foundations are little more than dynastic devices for advancing questionable agendas. The controversy surrounding the Clinton Foundation has exposed to many the less attractive aspects of some family foundations.

In an article in the Florida Tax Review, I called for the limitation of charitable deductions for federal estate taxes. Such a limit would balance the need to encourage charitable giving with the countervailing policy that all persons should pay some tax. I called, at a minimum, for restrictions on the federal estate tax charitable deduction when wealth is bequeathed to a family foundation rather than to a public charity.

The Giving Pledgers need not wait for the federal tax law to be changed. Giving Pledgers can agree now that part of the wealth they transfer should go to the federal treasury to compensate—in whole or in part—for the estate taxes avoided by their charitable bequests. In addition, Giving Pledgers can make a commitment to leave part or all of their resources to public charities rather than private foundations.

In this way, the Giving Pledge’s beneficial impact on American society will be strengthened as the costs of the Pledge are reduced.

Image Credit: “Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation” by Lester Public Library. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The continuing benefits (and costs) of the Giving Pledge appeared first on OUPblog.

Capturing the essence of Madame Bovary

A new film adaptation of Gustave Flaubert’s French classic Madame Bovary, starring Mia Wasikowska and Ezra Miller, has just been released.

Considered to be one of the great masterpieces of 19th century literature, Madame Bovary tells the tragic story of Emma Rouault, whose unhappy provincial marriage leads her into two adulterous affairs — first with the young and intelligent Léon and then with the dashing and seductive Rodolphe.

The tragic story has been told and retold in a number of adaptations since the text’s original publication in 1856 in serial form. But what differences from the text should we expect in this film adaptation? Will there be any astounding plot points left out or added to the mix?

Film director Sophie Barthes explains one of the decisions she made that forces the film to deviate (at least slightly) from the text:

…[T]he choice was not to have a child which would be processing the whole story because in the book she’s very ambivalent about her child, and if you put only a few scenes then she just becomes a bad mother. And I think with Madame Bovary everything is much more complex than that. She’s not a bad mother, she’s just a conflicted person about everything. So all the little choices you’re making along the way, in the process you hope you don’t lose the spirit of the book.

An adaptation is, of course, a derivative work and allows for creative liberty. We see this with many film adaptations; it is not always necessary to recreate every detail or plot point in a book to get a certain theme or message across.

Despite her taking creative liberties, Barthes also explains that she captures what she hopes is the essence of the protagonist Emma Bovary:

She embodies a piece of [the] human condition. … The complexity of the character, her psychology, the fact that you can never really grasp who she is… she is an eternal character because she has very early bi-polarity. … There’s something about her that is very enigmatic and you can never fully grasp who she is.

As far as the director’s intentions are concerned, her adaptation of Madame Bovary will in fact do it justice. But we’ll leave that decision for you to make.

If you’ve seen the movie already, what did you think? Were the creative liberties justified, given its medium and 2-hour length? Let us know in the comments section.

Featured image: Madame Bovary. (c). Alchemy/Millennium Entertainment via NYTimes.com.

The post Capturing the essence of Madame Bovary appeared first on OUPblog.

Echoes of caste slavery in Dalit Christian practices

In the mid-twentieth century Dalit migration from the villages of southern princely State of Travancore to the villages in the Western Ghats hills in the north was reminiscent of Exodus, although we are yet to have substantial narratives of the difficult journeys they undertook. In the new villages in the British Malabar where they settled down, they could own small pieces of land and become marginal farmers. One of the surprising things is that majority of the Dalit migrants from Kerala were Dalit Christians. It is worth speculating if the story of Exodus had anything to do with their migration and spatial mobility, which they saw as a necessary escape from the land of slavery that the Travancore was.

The oral history of Dalit Christian migration often alludes to the story of Exodus. However, slave castes ran away into the wilderness to escape even before they came into contact with British missionaries. In the mid-nineteenth century British Missionaries met runaway slaves hiding deep inside the forests of Travancore, forming ‘maroon communities’ in today’s Kottayam district. The Hill tribes inhabiting these forest tracts never disturbed the asylum seekers. In a matter of few years the runaway slaves also came into contact with the Church Missionary Society missionaries and learned the basics of Christian faith and prayers. Reflecting on the experience liberation of African Americans in his seminal book, Black Reconstruction, W.E.B. Du Bois, refers to liberation from slavery as “the coming of the Lord…. This was the fulfillment of prophecy and legend. It was the Golden Dawn, after chains of a thousand years for the first time.” We may observe a similar coming of the Lord phenomenon in the case of slaves in Kerala.

The experience of Dalits in early twentieth century Kerala shows their multiple engagements with the problem of liberation from the vestiges of slavery and their craving for liberation. The idea of liberation that they learned from the Gospel had a fundamental effect in transforming their lives. Religion became a central site of the experiences of modernity to Dalits. Du Bois observed, “for most of the black folk emancipated by civil war God was real. They knew Him. They had met him personally in many a wild orgy of religious frenzy, or the black stillness of night.” In the stillness of the night in the Travancore villages the slave caste men women and children met for prayers in their slave schools or sometimes in the jungles. These were the places where they met God, transforming such places into sites of liberation and modernity for the slaves.

‘A school of untouchables near Bangalore’ by Lady Ottoline Morrell (1935). NPG Ax143754. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

‘A school of untouchables near Bangalore’ by Lady Ottoline Morrell (1935). NPG Ax143754. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. © National Portrait Gallery, London.As late as the 1940s the descendants of slaves struggled hard to achieve a dignified social life. Dalits in several parts of Kerala faced several indignities, including forcing them out of public roads and preventing them from using white and clean clothes to mention a few. The structural violence of food scarcity was another thing that overshadowed their lives. They had to wage protracted struggles to overcome these oppressions. They faced institutionalized social injustice that continued well into the postcolonial period.

Nevertheless, we come across highly imaginative inversions of the symbols of structural violence, heavily loaded with meanings. Even today, a peculiar practice is part of the observances and rituals of Passion Week in a predominantly Dalit congregation of the Marthoma Syrian Church in the Trivandrum district of Kerala. At noon meals on Good Friday, rice gruel is served to the people in the small holes that are dug into the ground. Usually a piece of plantain leaf is fixed in the hole before the gruel is served that keeps the gruel from being mixed up with earth. In the days of caste slavery slaves used to be fed in such holes, and it remains in the social memory of former slave castes in Kerala as a symbol of oppression and humiliation. In the current context this practice becomes a perfect identification with the sufferings and humiliation of Jesus. The dalits of the congregation wanted their history of oppression to have larger meaning in contemporary life.

Similar inversions of memories and symbols of slavery remind us of the multiple ways in which the modernity of slavery remains with us.

The post Echoes of caste slavery in Dalit Christian practices appeared first on OUPblog.

Lies, truth, and meaning

Words have meaning. We use them to communicate to one another, and what we communicate depends, in part, on which words we use. What words mean varies from language to language. In many cases, we can communicate the same thing in different languages, but require different words to do so. And conversely, sometimes the very same words communicate different things in different languages. In Estonian, I am told, a zealous germophobe would enjoin us to join her in cleaning the rooms by saying ‘Koristame ruumit!’ But she should take care in expressing this enthusiasm in Finland, for in Finnish this very same sentence means ‘let’s decorate the corpses!’.

One of the most important consequences of differences in meaning, is a difference in truth. It is because ‘tall’ and ‘friendly’ mean different things, that what we say with the sentence ‘Maria is tall’ can be true even though what we say with the sentence ‘Maria is friendly’ is not, or conversely. If we know when what we say with a sentence is true, we therefore know a lot about what it means. Much of our contemporary understanding of linguistic meaning in both philosophy and linguistic semantics exploits this fact, by trying to characterize the meanings of words in terms of their contribution to what would make sentences involving them true.

One of the most ancient puzzles in philosophy, the paradox of the liar, reputedly due to Epimenides of Crete circa 600 BC, yields a surprising lesson about the limits of this strategy for understanding meaning. In the version I’ll consider here, Epimenides speaks as follows:

Epimenides: What I am saying right now is not true.

What Epimenides says is that what he says is not true. So if what he says is true, then it is true that what he says is not true, and hence what he says is not true. But if what he says is not true, that is precisely what he says! So it is true. So either assumption about the truth of what he says leads to a contradiction. This is the paradox.

“The moral, these philosophers say, is that a consistent language cannot contain its own semantic vocabulary.”

We can avoid accepting a contradiction, if we deny that Epimenides says anything, when he speaks as above. It turns out that other, harder, versions of the paradox make it difficult to accept this as the solution. But even if we grant that this resolves the paradox, the liar still challenges the idea that meaning can be explained in terms of truth. This is because the sentence uttered by Epimenides is clearly meaningful. Even if we deny that, strictly speaking, there is anything that Epimenides can say by uttering it, it is precisely because the words mean what they do, that nothing can be said with it. But there is no consistent answer to what it would take for what this sentence says to be true.

One common moral drawn by many philosophers and logicians, generalizing on ideas from Alfred Tarski, is that this problem arises because the language whose words we are trying to understand includes the very word – true – that we are using to cast light on meaning. In jargon, it includes its own semantic vocabulary. The moral, these philosophers say, is that a consistent language cannot contain its own semantic vocabulary. This conclusion is drastic. It appears to rule out the possibility of monolingual speakers understanding the meanings of words in their own language.

A more promising conclusion is that though truth carries information about meaning, it is the wrong place to look for the nature of meaning. One striking clue to how to think differently about meaning comes from expressivism, the contemporary heir to the emotivist theory of ethics. In the 1930’s, emotivists like A.J. Ayer and Charles Stevenson claimed that the meaning of moral words like ‘wrong’ cannot consist in a contribution to what makes sentences involving them true, but must lie in some other feature of what they are used to do. Contemporary metaethical expressivism takes this thought seriously and proposes that what makes declarative sentences meaningful is what it takes to believe what we can say with them, rather than what it takes for it to be true.

Expressivists don’t eschew the word ‘true’, but it isn’t part of their semantic vocabulary. That is, they don’t use it to explain meanings. They can make sense of how Socrates’ and Epimenides’ sentences could both be meaningful, because what makes a sentence meaningful is just that there is a condition that you must satisfy in order to believe what it says. But there is no inconsistency in accepting that there is such a condition. Indeed, we know something about it – in the case of what Socrates says, we know that it is rationally inconsistent with knowledge of what Socrates and Epimenides actually said.

Expressivism therefore allows us to make sense of how Socrates’ and Epimenides’ sentences could be meaningful, because it doesn’t require that there be any conditions under which they would be true. It may seem surprising to get insight into the liar paradox from a skeptical view about the role of moral language. But philosophy is full of surprises.

Featured image credit: “I’m not a liar!”, by Tristan Schmurr. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Lies, truth, and meaning appeared first on OUPblog.

July 5, 2015

DIY democracy: Festivals, parks, and fun

Wimbledon has started, the barbeques have been dusted off, the sun is shining, and all our newly elected MPs will soon be leaving Westminster for the summer recess. Domestic politics, to some extent, winds down for July and August but the nation never seems to collapse. Indeed, the summer months offer a quite different focus on, for example, a frenzy of festivals and picnics in the park. But could this more relaxed approach to life teach us something about how we ‘do’ politics? Is politics really taking place at festivals and in the parks? Can politics really be fun?

The recent suggestion that the Glastonbury Festival provides a model for policy reform took many academics and commentators by surprise. “If you want to know how to achieve those things the politicians promise but never quite deliver — a ‘dynamic economy’, a ‘strong society’, ‘better quality of life’ — stop looking at those worthy think-tank reports about the latest childcare scheme from Denmark or pro-enterprise initiative from Texas” Steve Hilton, the former Director of Strategy for David Cameron argued in The Spectator in June this year, “just head down to Worthy Farm in Somerset… it’s got so much to teach us”. Personally, I’ve never been ‘a festival person’ (and yes, there is such a type) and images of the festival each year only convince me that I should never go.

But the notion of festivals as the source of a new politics, of a new way of organizing society, and for delivering and protecting collective goods without the ‘hard’ elements of the modern state (i.e. police, laws, prisons, etc.) keeps nagging at my mind. After studying political science for nearly two decades maybe I can no longer see the wood for the trees (please note the nice use of the park-based metaphor)? Have I become so fixated on the formal institutions and procedures of representative democracy that I no longer recognize the emergence of ‘insurgent’ patterns of engagement? Are festivals the source of new forms of ‘civic-ness’ and arenas for debate?

Glastonbury, 2010, by Neal Whitehouse Piper. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Glastonbury, 2010, by Neal Whitehouse Piper. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.Steve Hilton’s comments were not, in fact, that new. At a pre-election debate at the University of Sheffield in April, the former Home Secretary David Blunkett and The Times columnist Matthew Parris both reflected on the growth and role of arts and culture festivals in terms of promoting public engagement in politics. Parris suggested that “festivals are the new political arenas” adding that “conventional politics is out of favour and festivals have emerged to fill an important social function”. There are limits to this argument. Indeed, it is only a short intellectual hop, skip, and jump before one takes this logic and ends up with Nigel Farage and his cliché that “every pub is a parliament” but there is something about the ethos and culture of festivals, especially the smaller and less professional music, literary, or arts events, that does resonate with the broader anti-political climate. Put slightly differently, in a climate dominated by ‘disaffected democrats’ is there something about how festivals do everyday politics that MPs might reflect upon during the summer recess?

I think there is but I am not sure exactly what ‘it’ is.

What does the existing academic research tell us about the politics and political implications of festivals? Very little, if anything at all. The existing research has been captured by an economic lens that generally attempts to measure the financial value of festivals to a town, village, or community – in this regard it tells us a lot about the price of everything but absolutely nothing about the broader social value.

So what might the ‘it’ be that makes festivals potentially important in democratic terms?

In reality it is unlikely to be just one issue and it is equally unlikely to be able to tangibly define, bottle, or transfer this quality or essence to other forums but one crucial element seems to be letting the people govern.

“Let the people govern!” I hear our MPs cry in fear – as they pack their flip flops, sun cream, and their already well-thumbed copy of Bernard Crick’s In Defence of Politics – but there is something about stepping-back, trusting the public, and seeing what happens.

Steve Hilton gives the example of the Dutch town of Oudehaske where all traffic lights, road markings, speed limits and traffic signs were removed so that road-users would be forced to interact with each other and consciously navigate the streets. “When you treat people like idiots, they’ll behave like idiots,” the project’s leader, traffic engineer Hans Monderman, said. “Who has the right of way? I don’t care. People here have to find their own way, negotiate for themselves, use their own brains.” By removing external controls imposed by bureaucrats, the transport system was made more human. And everything improved: fewer accidents, better traffic flow.

In the UK the thousands of people that can be seen doing the ParkRun every Saturday morning provide a wonderful example of the power of one person to make a big difference. In 2004 Paul Sinton-Hewitt had the idea of people in local communities coming together for a regular run in their local parks. You could try and win if you wanted but most of it all was for fun and personal challenge. Since then the ParkRun initiative has emerged into a social movement. Run by volunteers on a rota basis there is no fee to take part, the internet and bar codes make registering easy and social media provides easy access to results and ‘nudges’ to come again. Over 40,000 people have volunteered to marshal races and over a million people participate each year. In 2009 Sinton-Hewitt was presented with the Runner’s World ‘Heroes of Running’ award for philanthropy for his work with ParkRun and in 2014 became a CBE in the Queen’s birthday honours for services to grass roots sports participation.

You might not think that running in the park is at all political – but it is. It is a perfect example of the ‘everyday politics’ that has a very real and direct impact on people’s lives. It is a mass participation activity for collective community benefit that is facilitated by the internet and delivered by volunteers. There is no profit motive (what a refreshing thought). “The implication being?” I hear you ask. Well, the implication is not some neo-liberal Tea Party argument about the need to get the state and those meddling politicians out of our lives. But it is to think about the potential for unleashing similar participatory endeavors and most of all to think about how such projects and opportunities can be genuinely opened-up to all sections of society. Possibly even do a little detailed research. But I would say that, I’m an academic.

Featured image credit: Glastonbury wellies, by judyboo. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr.

The post DIY democracy: Festivals, parks, and fun appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 237 followers