Oxford University Press's Blog, page 643

July 14, 2015

“Are there black Mormons?”

In the months leading up to the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, a few media outlets reinforced the public perception that Mormons (members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) were mostly white. Jimmy Kimmel asked on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, “Are there black Mormons? I find that hard to believe.” Reporter Jessica Williams from Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show interviewed five black Mormons, calling them “mythical creatures, the unicorns of politics.” She asked whether or not the five Mormons she met comprised the entire population of black people in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Susan Saulny, a reporter for the New York Times, similarly speculated that there were only a “very small number” of black Mormons, a “couple of thousand max” or somewhere between “500 to 2,000.” All three broadcasts revealed a public perception problem for Mormons in the twenty-first century—that they are too white.

The irony lies in the historical evolution of that public perception. Black Saints were among the first to arrive in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847 and have been a part of the Mormon experience from its beginnings. The first documented black person to join this American-born faith was Black Pete, a former slave who was baptized in 1830, when the fledging movement was less than a year old. Other blacks trickled in over the course of the nineteenth century and are woven into the Mormon story. At least two black men were ordained to the faith’s highest priesthood in its first two decades.

Mormons were so inclusive in the nineteenth century that accusations from the outside tended to focus on the perception that they welcomed everyone. In an American culture that favored the segregation and exclusion of marginalized groups, the Mormons stood out. The allegations leveled against them included that they had “opened an asylum for rogues and vagabonds and free blacks,” that they embraced “all nations and colors,” that they maintained “communion with the Indians,” and that their missionaries “walk[ed] out” with “colored women.” The perception was that they welcomed “all classes and characters,” received “aliens by birth,” and integrated people from “different parts of the world” into their communities and congregations.

“KIRCHE, Utah, USA” by Entheta. CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

“KIRCHE, Utah, USA” by Entheta. CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.Within a few months of Black Pete’s conversion in Ohio, news reports in Pennsylvania and New York announced that the Mormons had a black man worshipping with them. The reports were not intended as compliments. In Missouri, Mormons were accused of inviting free blacks to the state to incite a slave rebellion and to steal white wives and daughters. Even white Mormons were suspect. One report complained that they had “nearly reached the low condition of the black population” and another said that the Mormons were “little above the condition of our blacks either in regard to property or education.” Especially after 1852, when Mormons openly practiced polygamy, outsiders projected their fears of race mixing onto the Mormons. Political cartoons liked to imagine multi-racial Mormon families run amok in the Great Basin. In the minds of outsiders, polygamy was not merely destroying the traditional family, it was destroying the white race.

Mormons were certainly aware of the ways in which their status as white people was challenged. One leader acknowledged, “we are not accounted as white people,” while another complained that Mormons were treated “as if we had been some savage tribe, or some colored race of foreigners.”

In the nineteenth century, one way to measure whiteness was in distance from blackness—and so it was with the Mormons. Over the course of the nineteenth century, they moved away from their own black converts toward whiteness. In an uneven process, Mormon leaders barred black men from the lay priesthood and black men and women from the faith’s crowning temple rituals, policies firmly held in place by the early twentieth century.

So successful were Mormons at claiming whiteness for themselves that by the time Mitt Romney sought the White House in 2012, he was described as the “whitest white man to run for president in recent memory.” Even though the Church of the Latter-day Saints includes over one million members in Brazil and 400,000 in Africa and is more racially diverse in the United States than mainline Protestant churches, public perception lags behind.

Jimmy Kimmel’s query from 2012—“Are there black Mormons? I find that hard to believe”—is the polar opposite of the racial problem that Mormons faced in the 1830s. This shift marks a historic evolution for Mormons, from their nineteenth-century beginnings as a congregation “not white enough” to its current status as “too white.”

Image Credit: “Mitt Romney” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post “Are there black Mormons?” appeared first on OUPblog.

Insights into traditionalist Catholicism in Africa

Since the promulgation of the revised missal, popularly known as the Novus Ordo by Pope Paul VI, with the Apostolic Constitution Missale Romanun in 1969, a growing call for either a return to the Tridentine Mass or recognition of the legitimate place of such a rite alongside the Novus Ordo has gained an international status. Groups like the International Una Voce Federation and recently, the Ecclesia Dei Society continue to advocate for this, and their cause has resulted in the Motu Proprio, Summorum Pontificum of Benedict XVI permitting the typical edition of the Roman Missal issued by Pope John XXIII in 1962. Africa has and continues to be part of this conversation. The International Una Voce Federation is actively present in South Africa and Kenya. Ecclesia Dei Society is present in Nigeria and works in collaboration with International Una Voce Federation. Some within these groups identify themselves as traditionalist Catholics stressing the point that they are truly the defenders of the deposit of Catholic tradition. Others argue that they are the true church and that the Roman Catholic Church has fallen into heresy.

While these traditionalist groups share differing views on orthodoxy in relation to Roman Catholicism, their views on traditionalist Catholicism can be defined as an intentionality of meaning geared towards a consciousness that reveals the plenal hermeneutic-revelation of what is authentically catholic and traceable to ecclesial realities of the early church through a biased reading of church history.

For an average catholic, traditionalist Catholicism refers to the schismatic group founded by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, C.S.Sp. However, other traditionalist Catholic groups continue to emerge, who sometimes have no allegiance to or do not trace their origins to Lefebvre’s Priestly Fraternity of Saint Pius X (SSPX).

While the presence of Traditionalists in Africa is small, there is a growing awareness of the presence of these groups and interest in them by Africans. The SSPX has continued to make inroads in Africa and presently has a District of Africa, erected in 2008. Within the district, there are six priories located in five countries; two in South Africa, one in Gabon, one in Zimbabwe, one in Kenya, and one in Nigeria. The first was opened in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1986 and the most recent was opened in 2012 in Enugu Nigeria. There are twenty-two priests, two professed brothers, and eight sisters working in this District of Africa. Of these, there are currently two members of African descent, Rev. Gregory Obih and Rev. James Ngaruro. The former is an ex- Augustinian Friar-Priest from the Province of Nigeria, who left the Roman Catholic Church and joined the SSPX in 2007. He is currently the resident priest of the Priory in Nigeria. The latter is the first African ordained for the SSPX.

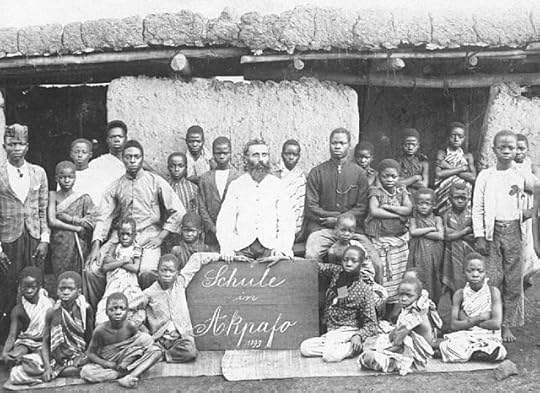

Missionary Andreas Pfisterer 1899 at the mission school in Akpafu, Volta-region of Ghana which was at that time a German colony by the name of Togo by Missionar der Norddeutschen Mission. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Missionary Andreas Pfisterer 1899 at the mission school in Akpafu, Volta-region of Ghana which was at that time a German colony by the name of Togo by Missionar der Norddeutschen Mission. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Another group currently present is an offshoot of the SSPX. This is the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter (FSSP). This traditionalist group refused to follow Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre into schism when he ordained four bishops for his Fraternity in 1988 without papal mandate. The group became a Clerical Society of Apostolic Life of Pontifical Right. Its only presence in Africa is in the Diocese of Orlu in Eastern Nigeria. It runs a parish named Saint Mary’s Church with a canonical status of a personal parish without boundaries. The parish operates a Marian shrine called Nne Enyemaka Shrine (Our Lady of Perpetual Help Shrine). The only African member of the FSSP is Rev. Evaristus Eshionwu. He was ordained for the Diocese of Orlu in 1972 and incardinated into the FSSP in 1999. He is currently the associate pastor of the parish. Though, there is no other presence of this group in Africa, a noticeable rapport exists between the retired bishop of Orlu Diocese, Nigeria, Bishop Gregory Ochiagha. He serves as their sacramental minister for administering sacraments reserved to the bishop for this growing community.

Other traditionalist groups are currently making advances to Africa. Among these is the Traditional Roman Catholic Church, formerly known as the Old Roman Catholic Church of America, who, though tracing its origins to the Old Catholic Church under the Union of Utrecht, has cut ties with the Old Catholic Church accusing it of embracing Modernist views. It claims to be the real Roman Catholic Church, arguing that it has preserved the true teachings handed down from the apostles. While the FSSP has accepted the teachings of the Second Vatican Council, by implication of its communion with the Roman Catholic Church, the SSPX continues to regard some aspects of the teachings of the Council as heretical and deviates from orthodoxy. The Traditional Roman Catholic Church rejects the Council and declares all its teachings heretical. This group is currently headed by Archbishop Mosley who styles himself as His Eminence Shermanus Randallus Pius Moslei, D.D., Primate of the Traditional Roman Catholic Church. This group currently has two African members; one of them is Rev. Cyril Nnadi, an ordained Roman Catholic priest of the Diocese of Umuahia in Eastern Nigeria. He left the Roman Catholic Church and joined the TRCC in 2007. He has served as their judicial vicar since 2009. The other African member is Rev. Hippolyte Marie Pagan from Cameroon who serves as the dean of their online seminary training as well as the legate to the African region.

Tensions continue to brew between followers of the SSPX and those of the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter. They accuse the latter of betraying the cause of the traditionalist by submitting to the ‘Modernist” Roman Catholic Church when it established communion with the Pope in 1988. Both the SSPX and the TRCC stress a literal understanding of extra ecclesiam nulla salus (outside the church there is no salvation), defined to mean an actual membership in the Catholic Church that their groups now represent along with those ecclesial groups they are in communion with. Consequently, they reject categorically the teaching on ecumenism. They are also against religious freedom by consequence of their reading of the theological statement of Cyprian of Carthage.

These traditionalists regard the writings of Michael Davies, a former president of International Una Voce Federation, and The Remnant, a bi-monthly newspaper as their vade mecum. Persons seeking to join these groups are first asked to read the works of Davies on the meaning and beliefs of traditionalist Catholics. Even though The Remnant claims to be an independent traditionalist catholic newsletter, its contents clearly favor the causes of the traditionalists. It updates its members globally on the progress of the traditionalist Catholic movement in the continent of Africa and also helps to raise awareness on how to raise funds to support the projects of the traditionalist groups operating in the continent.

Featured image: Catholic Church in Mombasa by Zahra Abdulmajid. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Insights into traditionalist Catholicism in Africa appeared first on OUPblog.

The British Invasion, orientalism, and the summer of 1965

Fifty years ago, at the height of the British Invasion, The Yardbirds released “Heart Full of Soul” (28 May 1965) and The Kinks, “See My Friends” (30 July 1965). Both attempted to evoke something exotic, mysterious, and distinctly different from the flood of productions competing for consumer attention that summer. Drawing on Britain’s long fascination with “The Orient,” these recordings started sixties British pop down a path that proved both rewarding and problematic.

The diversion had begun perhaps a year earlier when, on 29 July 1964, guitarist Davy Graham and singer Shirley Collins performed at the Mercury Theatre in London in a program the press described as having an “Eastern flavor.” Collins had travelled in the southern United States with folklorist Alan Lomax collecting songs from the Anglo-American tradition. In contrast, Graham had previously spent time in North Africa listening to and engaging in local musics, and began to incorporate these stylistic ideas into his own playing. Notably, his composition “Maajun” (1964) reveals how he had adapted elements from the repertoire of the North African version of the Arabic ‘ūd, a four-stringed short-necked ancestor of the lute (for example, his use of a drop-D tuning on the guitar). Some musicians in London clearly noticed.

Possibly the first to pick up on this idea in pop music, Graham Gouldman had written The Yardbirds’ first hit “For Your Love” (March 1965) and now presented them with a follow-up: “Heart Full of Soul.” He sets his primary melody in D minor to support lyrics about loneliness and despair, shifting to the parallel major during the refrain to evoke optimism. The impression of something South Asian comes through the limited range of the recurring instrumental motif and its apparent lack of resolution. Indeed, an early version of the recording includes anonymous Indian musicians on sitar and tabla, but inadequate microphone choice and placement (and probably producer Giorgio Gomelsky’s inability to convey what he wanted) rendered the sound inadequate. Guitarist Jeff Beck (who had just replaced Eric Clapton) played with the relatively new device of a distortion pedal (probably a Gibson Maestro) to approximate the overtone-rich sound of the sitar.

During a flight layover that The Kinks made in Mumbai in January 1965, a jet-lagged Ray Davies found himself watching the ocean in the early morning hours from his room at the Sun-n-Sand Hotel when a group of fishermen took their nets to the sea, singing as they went. The experience left a deep impression on him. The drone through much of the verse and a melody that rises from the third of the scale, while not entirely exotic, does carry a quality of otherness… Something not quite English any more. Notably, in the realization of “See My Friends,” his brother Dave Davies remembers Davy Graham as an influence, particularly in how he tuned his guitar.

Stereotyping nationalities, ethnicities, and cultures has long been a part of human behavior, and the West has historically offered no exception to this rule in music both popular (The Mikado) and elite (Madama Butterfly). What changed in the 1960s was (a) the speed and the volume at which information disseminated around the world and (b) the increasing commonness with which cultures interacted. That this interaction could never be on an equal footing was a social reality, but in that decade it also became an everyday reality.

The so-called British “invasion” that began in 1964 more properly offers us an example of modern globalization wherein cultures increasingly came into contact with each other through developments in the technologies of transportation and media. As much as Americans understood the experience as an intrusion into their cultural domain, the appearance of artists from Britain, Spain (Los Bravos), Australia (The Easy Beats), etc. on American charts reflected globalization. Rather than a mounted assault on any one culture, mid-twentieth-century technology enabled intercultural interaction on a global scale.

For the British, centuries of imperial involvements and the subsequent creation of the British Commonwealth of Nations (with its guarantee of open travel between the member states) generated waves of immigrants from the Caribbean, Africa, and South Asia, not to mention emigration from Britain to Canada, Australia, and other Commonwealth members. Notably, the Britain of the sixties popular-culture explosion experienced a sudden challenge to its established hegemonies of class and ethnicity through a questioning of British identity.

As Edward Said has broadly observed, the West invented myths about immorality and inferiority to justify its military and economic domination over cultures around the world. But for the adolescents of the sixties, challenging adult norms and the Establishment became a preoccupation and a justification for exploring these presumptions.

Like Ray Davies, some artists came to this musical realm because it challenged established western conceptions of how music worked and opened up their world to other possibilities, whether or not they would be able to take advantage of them. “See My Friends” offered a subtle incorporation of Indian ideas that were probably not entirely obvious to most listeners. Similarly, Gouldman and The Yardbirds’ “Heart Full of Soul” balanced this relationship, taking inspiration from Indian ideas, but incorporating them in a way that would have disguised the possible origins from listeners.

More problematically, when musicians conflated ideas of melodic and rhythmic complexity and/or the acoustic sound of an instrument such as the sitar with an orientalist projection that drug use and open sex was a norm in non-Western cultures, they ultimately generated objectified representations that members of the originating cultures found offensive. Davy Graham’s title of his recording “Maajun” (a term for a mix of marijuana and hashish) provides such an illustration. As interesting as his musical ideas were, conflating them with drug usage betrays an orientalist stereotype of the exotic other.

Over the next three years, numerous other British and American musicians would incorporate ideas and idioms borrowed from the non-Western world. What would begin to change very gradually would be the willingness of musicians from these cultures to see their art appropriated and re-contextualized.

Featured Image: “Ray Davies of the Kinks” by Jean-Luc. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post The British Invasion, orientalism, and the summer of 1965 appeared first on OUPblog.

Rihanna, the Court of Appeal, and a Topshop t-shirt

Can a fashion retailer take a photograph of a celebrity, print it on a t-shirt and sell it without the celebrity’s approval? Yes, but sometimes no – not when the retailer has previously gone out of its way to draw a connection between its products and that celebrity; in this case Robyn Fenty, aka Rihanna.

How did this begin? Rihanna released her sixth album, Talk That Talk, in 2011. One of the singles was We Found Love. Photographs were taken of Rihanna at the shoot for the video to the single. The photographer, who was legitimately entitled to the copyright for the photographs, licensed one of them to Topshop which printed this t-shirt and sold it in its shops and online in 2012.

Because the image was licensed, there was no question of copyright infringement, and Rihanna did not own the copyright in any event.

Rihanna, and the companies that had been set up to exploit her image, did not let that stop them going after what they considered to be unauthorised merchandise. In the English High Court in 2013, Mr Justice Birss found in Rihanna’s favour when he decided that Topshop had committed the tort of passing-off, and caused damage to Rihanna’s goodwill.

Unhelpfully for practices trying to advise clients on what they can and can’t do, Mr Justice Birss concluded:

“The mere sale by a trader of a t-shirt bearing an image of a famous person is not, without more, an act of passing off. However the sale of this image of this person on this garment by this shop in these circumstances is a different matter…”

Topshop took the case to the Court of Appeal, but early in 2015 found out that it had lost again, with the appeal court upholding the High Court’s finding of passing-off.

Passing-off traditionally protects the goodwill a trader has in its business – usually through a name or perhaps a logo or get-up. It is often cited as protecting trade marks which have not been registered and so cannot avail themselves of the protection of trade mark law.

The tort has three ingredients:

Goodwill – i.e., customers know of your business by its name, logo or get-up.

A misrepresentation – a third party has misrepresented to the public that its goods or services are connected to yours, often by using the same or a similar name, logo or get-up.

And finally, that misrepresentation has caused you damage.

Establish all three, and the court will order an injunction and require that the offending party compensate you.

“Rihanna 2012 (Cropped)”, by Liam Mendes, Uploaded by MyCanon – Rihanna. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Rihanna 2012 (Cropped)”, by Liam Mendes, Uploaded by MyCanon – Rihanna. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Passing-off its part of the English common law, developed by judges over time, and thus is capable of evolving, and has evolved, to reflect changes in business and consumer behaviour. One area into which it has developed is to provide protection against false endorsement. In 2002, Talksport radio was found liable for passing-off when it doctored an image of F1 driver Eddie Irvine to show him holding a Talksport-branded radio, and used that image in advertising.

Rihanna was held to have goodwill in her image. Damage to that goodwill would include a lost licensing opportunity for the t-shirts. The key issue for the Court was whether there was any misrepresentation: the High Court judge stated that it was “certainly not” the law that “the presence of an image of a well-known person on a product like a t-shirt can be assumed to make a representation that the product has been authorised.” So Rihanna needed to establish something more than just the fact of the t-shirt if she were to win her case.

Fortunately for Rihanna, Topshop didn’t just put her image on a t-shirt. It had made a considerable effort to emphasise a connection between the business and Rihanna. Topshop ran a competition for a personal shopping appointment with Rihanna. It tweeted when Rihanna visited its flagship store. It made other statements on social media. Topshop sought “to take advantage of Rihanna’s public position as a style icon.” Coming from the video shoot, Rihanna fans and Topshop customers might think the image used on the t-shirt was part of the marketing campaign for the track and associated album. So taking everything into account, the judge felt that a substantial portion of those considering buying the product — namely, Rihanna fans — would think that the garment was authorised. Passing-off was therefore established.

The Court of Appeal agreed. It explained the two critical hurdles that must be overcome by a claimant in Rihanna’s position: (1) the application of the name or image to the goods must tell the consumer a lie; and (2) the lie must be material – it must induce consumers to buy the product. The Court of Appeal was satisfied the trial judge had these important principles in mind and that his application of the facts to them was appropriate. With no findings of errors of principle, the Court of Appeal unsurprisingly upheld the trial judge’s decision. The Court of Appeal does not like to interfere with findings of fact from a lower court, providing everything else is above board, and this was no exception.

One of the three Lord Justices of Appeal added a remark at the end of the judgment that he felt the case was “close to the borderline” – and that it was only open to the trial judge to conclude as he did because of the combination of Rihanna’s past association with Topshop, and the nature of the image used, being one tied in with publicity for Talk That Talk.

There is a caution in both courts’ judgments: they were very clear that they were not attempting to extend the law of passing-off into the realms of a right of personality or image right – there is no such right in English law. Passing-off is flexible, but the vital ingredients remain and Rihanna only succeeded because the particular peculiarities of the image used and her relationship with Topshop put her in a different position to that in which many other celebrities whose images are used in this way are likely to be.

So it’s a good reminder for designers and retailers, but as much as it might be hailed by those with an image worth protecting, it’s also a conservative and cautious decision, heavily reliant on the peculiar facts. It is unlikely to herald a rash of t-shirt cases any time soon.

Featured image: ‘Justice isn’t blind, she carries a big stick’, by Jason Rosenberg. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Rihanna, the Court of Appeal, and a Topshop t-shirt appeared first on OUPblog.

July 13, 2015

From communist power to political collapse: twentieth-century Russia [timeline]

Marked by widespread political and social change, twentieth-century Russia endured violent military conflicts, both domestic and international in scope, and as many iterations of government. The world’s first communist society, founded by Vladimir Lenin under the Bolshevik Party in 1917, Russia extended its influence through eastern Europe to become a global power. The USSR and its controversial leaders polarized diplomacy worldwide, drawing the rival United States near to nuclear war in the 1960s. The events included in our timeline, sourced from Russia in World History by Barbara Alpern Engel and Janet Martin, highlight the most pivotal episodes in twentieth-century Russian history, each of which contributed to the Soviet Union’s eventual collapse in 1991.

Featured image: Plainclothes policemen on patrol in Petrograd during the October Revolution, 1917. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Timeline background image: Flag of the Soviet Union. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post From communist power to political collapse: twentieth-century Russia [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

South Africa and al-Bashir’s escape from the ICC

Ten years after the UNSC’s referral of the situation in Darfur to the Prosecutor of the ICC, the sad reality is that all the main suspects still remain at large, shielded by their high position within the Government of Sudan. The most outstanding case of warrants of arrest remaining to be executed are those issued by Pre-Trial Chamber (PTC) I on 4 March 2009 and 12 July 2010 against Omar al-Bashir, the President of the Republic of Sudan since 16 October 1993, and the first and only non-ICC state party’s incumbent Head of State facing genocide charges, allegedly committed in the Darfur region of Sudan.

Recently, President al-Bashir was able to return to Khartoum after attending the 25th Summit of African Union in Johannesburg in June.

Shockingly enough, South Africa has decided to join the apparent institutionalisation of non-cooperation with the Court requested by the African Union (AU).

As a founding member of the ICC, which under the Nelson Mandela presidency had put human rights at the centre of its foreign policy, South Africa has been one of the strongest supporters of the Court and is one of the few African States to have implemented the provisions of the Rome Statute into domestic law. South Africa has warned al-Bashir twice in past years not to visit the country because he might face arrest.

The South African government, backed by the African National Congress (South Africa’s governing social democratic political party), held the view that the ICC requests were preempted by the obligation to respect al-Bashir immunities as head of a member state of the African Union.

In the belief that the involvement of the ICC in the situation in Darfur poses a threat to peace and security on the African continent, the African Union decided its members must not cooperate with the ICC (pursuant to Article 98 of the Rome Statute) until the UN Security Council has considered the request by the AU for a deferral of its decision to refer the matter to the ICC for investigation.

Notably, this request has not been acted upon. In Resolution 1828, which extended the mandate of the African Union-United Nations Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID), the UNSC turned down the AU the request for a deferral. Instead, the UNSC simply stated in a preambular paragraph that it was ‘taking note’ of the African Union’s concerns, and emphasized in another preambular paragraph ‘the need to bring to justice’ the perpetrators of the ongoing crimes.

Notwithstanding the subsequent practice of the Security Council, the South African government decided that it was obliged to follow the AU decision and consequently not to arrest and surrender the Sudanese President to the ICC during his visit to the country. There is little doubt that this action, in line with the profound strain in the relations between the African Union and the ICC, has been taken in plain defiance of state party obligations vis-à-vis the ICC, the Rome Statute, and UNSCR 1593 (2005).

At the domestic level, the South African government’s decision to let al-Bashir to visit the country, and leave it without being arrested, caused a serious constitutional crisis. The Southern African Litigation Centre (SALC) had brought an urgent application against the government decision to grant immunity to all delegates attending the AU Summit. A South African High Court issued an interim order on 14 June 2015 compelling the State Respondents, including the Department of Home Affair, to take all the necessary steps to prevent the Sudanese President from leaving the country until the Court handed down a final order. The government failed to enforce this interim order.

On 15 June 2015 the South African High Court ruled that the State’s failure to comply with the two ICC warrants of arrest, and to enforce the High Court’s order to detain al-Bashir, was a plain violation of South Africa’s obligations both under international and domestic law. Presumably, the opposition parties and SALC will duly consider pursuing contempt proceedings against the South African government for contravening the High Court orders, and for violating the South African Constitution and the International Criminal Court Act 27 of 2002 that domesticated the Rome Statute’s obligations.

It is not entirely clear why the South African president, Jacob Zuma, has voluntarily decided to join the growing number of African leaders who argue that the ICC is biased against Africa, representing a glaring practice of selective justice, a 21st form of neo-colonialism, and an oppressive tool of Western powers.

Omar al-Bashir, 12th AU Summit, U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jesse B. Awalt/Released, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Omar al-Bashir, 12th AU Summit, U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jesse B. Awalt/Released, public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsA central purpose of the new system of international criminal accountability (established by the creation of the first permanent International Criminal Court) is to prosecute government leaders who might otherwise use their power positions to secure impunity for their crimes.

President Zuma’s political party (ANC) has called for a review of the Rome Statute in order “to compel all member states of the United Nations to be signatories to the Rome Statute to ensure that the ICC is able to act in accordance with the function for which it was intended – a fair and independent court for universal and equitable justice.” The ANC seems to forget that the choice of the Rome Conference has been to establish a Court that “ shall be brought into relationship with the United Nations” but which is not part of the UN system; that the Security Council cannot override the terms of the Statute; that the only way for the ICC to assert personal or territorial jurisdiction over non-party states is where it is invited to do so by that non-party state via a formal declaration, or by the Security Council using its exceptional coercive power under Chapter VII and the trigger mechanisms of Article 13(b) of the Rome Statute — a situation within a non-party state (like Sudan) that threatens the international peace and security.

Investigations and prosecutions in Africa should not be curtailed until the ICC reaches a true universality. Enhancing universality is a priority for the Court and has been since its establishment. Nonetheless, as a treaty-based institution, the ICC has only jurisdiction over crimes committed on the territory, or by nationals, of states that have freely accepted the Court’s jurisdiction by ratifying the Rome Statute. With a membership of 123 states parties (out of 193 UN member states), the ICC still lacks of universal jurisdiction to make it a truly global institution.

In a statement concerning South Africa’s position on the ICC matter, an Acting cabinet spokesperson said that the South African government would review South Africa’s participation in the Rome Statute and that South Africa may, as a last resort, also consider withdrawing from the ICC. Such a decision will only be taken when South Africa has exhausted all the remedies available to it in terms of the Rome Statute, the Charter of the United Nations, and other international law instruments.

Among the reasons for such a dramatic statement, the government mentioned the fact that the Permanent Members of the Security Council, which are not parties to the Rome Statute, may participate fully in discussions on the ICC and referrals to the ICC by the Security Council of a situation in a country. Moreover, the UNSC Permanent Members have taken steps to ensure that their officials and military personnel will not be subjected to the jurisdiction of the ICC.

Secondly, the government mentioned the tension between Article 27 (2), which confers to the ICC the jurisdiction over anyone, irrespective of that person’s official status, and Article 98 that addresses the traditional types of immunities recognized under international law and establishes the conditions under which the Court may proceed with a request for surrender or assistance.

According to the South African government, which referred expressly only to the international agreements mentioned in paragraph 2, Article 98 places a clear obligation on the ICC to assist countries that have difficulties in executing the warrant of arrest for President al-Bashir because of their international obligations.

International Criminal Court in The Hague. © thehague via iStock.

International Criminal Court in The Hague. © thehague via iStock.Also according the South African government the ICC has not acted in good faith during the consultations imposed by Article 97 of the Statute (in case of disagreement as to the general obligation to cooperate). The government asserts that the ICC has not made serious and sincere efforts to assist South Africa in its difficulties in executing the warrants of arrest.

This Article stays at the heart of the complex and carefully drafted provisions contained in Part 9 of the Statute, setting out the scope of State Parties’ obligations regarding international cooperation and judicial assistance for the gathering of evidence and for the arrest and surrender of persons. It establishes a general obligation incumbent upon States Parties to consult without delay with the Court on problems which may impede or prevent the execution of the request, such as breaching a pre-existing treaty obligation. In this respect, it’s difficult to qualify the 2009 AU decision not to cooperate with the Court, pursuant to Article 98 of the Rome Statute, as a “preexisting treaty obligation” incumbent upon African states parties.

As to the duty to consult with the Court under Article 97, the Ambassador of South Africa to the Netherlands and an accompanying legal advisor effectively entered into consultations with the ICC on 12 June 2015. According to the government, the Ambassador stressed in that meeting that he was unable to deal with the technical and legal issues involved, thus asking for a second meeting with the Court, finally arranged for Sunday 14 June 2015.

However, late on Saturday 13 June 2015, the Prosecutor of the ICC made an urgent request to the ICC for an order further clarifying that Article 97 Consultations with South Africa concluded and that South Africa is under the obligation to immediately arrest and surrender President al-Bashir, without giving any notice whatsoever to South Africa. PTC II of the ICC heard the matter and issued a Decision on the same day. It decided that it was unnecessary to further clarify that the Republic of South Africa (RSA) is under the duty to immediately arrest al-Bashir and surrender him to the Court, as the existence of this duty was already explained to South Africa on 12 June 2015 in response to the South African note verbale. Particularly, the Court stressed that South Africa was reminded of the decision issued by the Court on 9 April 2014, in which the PTC II settled the very same matters raised at the time by the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In that decision the ICC chamber clarified that there exists no impediment at the horizontal level regarding the arrest and surrender to the Court of al-Bashir, since the UNSC, acting under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, had already implicitly waived the immunities granted to al-Bashir under international law and attached to his position of a head of state. Consequently, DRC could not invoke any obligation to the contrary, including that of the AU, pursuant to Articles 25 and 103 of the UN Charter. The conclusions reached by the ICC are clearly supported by the proper general interpretative principles and presumptions applicable to the UNSCRs. Therefore they are applicable, mutatis mutandis, to RSA.

In this respect, the argument made by South Africa appears rather as a pretext.

Also questionable is the declaration made by the South African government that it will enter into formal negotiations with the ICC on the matter with the view to understand the ICC’s reasoning and how it interprets Article 97. By consenting to this mechanism, which imposes at the same time an obligation of conduct and an obligation of result (to resolve the matter in good faith), the State Parties to the Rome Statute have agreed upon giving to the ICC the ultimate interpretation of the extent of their duty to cooperate, and the “final say” — being entitled to a decision from the relevant ICC’s chambers.

Sudan and South Sudan Political Map. © PeterHermesFurian via iStock.

Sudan and South Sudan Political Map. © PeterHermesFurian via iStock.Therefore, they have ultimately agreed that it is a matter for the Court to determine whether the requested state may legitimately propose a valid ground for refusing the requested cooperation, since the aim and the ratio of the Article 97 is that States shall consult with the Court without delay in order to resolve the matter and not to water down the ICC’s cooperation regime. Article 87(7) of the Statute confirms this conclusion by expressly giving the power to the Court to make a judicial finding upon any disagreement relating to whether or not a requested state is obliged to cooperate with the Court and whether the impediments enumerated in Article 98 of the Statute apply.

Contrary to what is implicitly asserted by the South African government, clearly not all the problems that might impede the execution of an ICC’s request turn ipso facto into legitimate grounds for refusal of cooperation with the Court. Furthermore, any disagreement relating to whether or not a requested state is obliged to cooperate with the Court in respect of a request for surrender and assistance is a dispute concerning the judicial function of the Court, one that should be settled by the Court itself under Article 119 (1) of the Statute.

The Court’s competence to make a judicial findings on a non-cooperating state’s illegal action, contrary to the provisions of the Statute, consequently shifts the pendulum towards a cooperation model of the Rome Statute more “vertical” and “supranational” than currently qualified.

Analogously, it is questionable that the South African declaration — that it will enter into immediate discussion with the African Union and its member states on African dispute resolution mechanisms — can be better implemented to find an African solution to African problems. South Africa seems to have done nothing more than a lip service to the envisaged amendment to the protocol of the Statute of the African Court of Justice and Human Rights to expand this court’s jurisdiction to include international and transnational crimes, such as terrorism, piracy, and corruption.

It’s worth noting that this draft Protocol is not only studiously silent on any relationship between the African Court and the ICC, but that it provides in its current Article 46 A bis the express respect of immunities attached to the official capacity of any person serving as a AU head of state or government, or anybody acting in such capacity, or other senior state officials based on their functions during their tenure of office. There is legitimate concern that the AU Commission has simply envisaged a negative complementarity with the ICC international criminal system in order to protect the African leaders and the sovereign rights of its members (including fugitives from justice) more than the rights of thousands of African civilian victims.

Those victims, particular women and children, as well as millions of displaced people, remain the distinct feature of the conflict in Darfur.

The post South Africa and al-Bashir’s escape from the ICC appeared first on OUPblog.

Did the League of Nations ultimately fail?

The First World War threw the imperial order into crisis. New states emerged, while German and Ottoman territories fell to the allies who wanted to keep their acquisitions. But at the Paris Peace conference of 1919, the allies agreed reluctantly to govern their new conquests according to international and humanitarian norms and under ‘mandate’ from the League of Nations. In the following three videos, Susan Pedersen, author of The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire, discusses the emegence of the League and the consequences of this decision.

What was the unexpected role played by Germany in the League of Nations?

Susan Pedersen discusses Germany’s surprising power in shaping the mandate system, and its drive for international economic access and control.

What was Sir Eric Drummond’s role in shaping the League of Nations?

A relatively unknown figure, Sir Eric Drummond was the first Secretary General of the League. Susan Pedersen argues that he is unfairly forgotten, as his innovative structure of the League has encouraged the creation of many other international organizations.

Did the League of Nations ultimately fail?

This is a familiar question. However, in this video, Susan Pedersen explains the importance of recognizing the development of the League of Nations over time when determining its success. She argues that it is important to recognise the League as more than just a security arrangement.

Featured image credit: Malaria Commission of the League of Nations, Geneva. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Did the League of Nations ultimately fail? appeared first on OUPblog.

July 12, 2015

Talkin’ about a ‘Revolution’

Amid Fourth of July parades and fireworks, I found myself asking this: why do we call this day ‘Independence Day’ rather than ‘Revolution Day?’

The short answer, of course, is that on 4 July, we celebrate the signing of the Declaration of Independence, a day that has been commemorated since 1777. And the term ‘Independence Day’ has its earliest citation in the Oxford English Dictionary from 1791, when it appeared in an entry in Jacob Hiltzheimer’s Diary: ‘This being Independence Day,’ the Pennsylvania assemblyman wrote, ‘the Governor invited several of the neighbors to dine with him.’ In 1870, Congress got around to making Independence Day a holiday for federal employees (though it was an unpaid holiday until 1938).

In school, however, the events of 1775 through 1783 may either be called the War of American Independence or the Revolutionary War. The term ‘War of American Independence’ suggests a struggle to become a sovereign nation. ‘Revolution,’ on the other hand, implies both a new political order and the overthrow of an older one. So we have every right to be curious about when the term ‘revolution’ joined ‘independence’ in reference to US history.

‘Revolution,’ it turns out, was rarely used in colonial pamphlets in the years leading up to 1776. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense talked of ‘independence,’ using terms such as ‘separation,’ ‘civil war,’ and ‘natural rights.’ When ‘revolution’ was used, it was only in reference to Britain’s Glorious Revolution, the unseating of James II, and his replacement by William and Mary. In Common Sense, the word ‘revolution’ occurs just once when Paine says: ‘Thirty kings and two minors have reigned in that distracted kingdom since the Conquest; in which time there have been (including the Revolution), no less than eight civil wars and nineteen rebellions.’

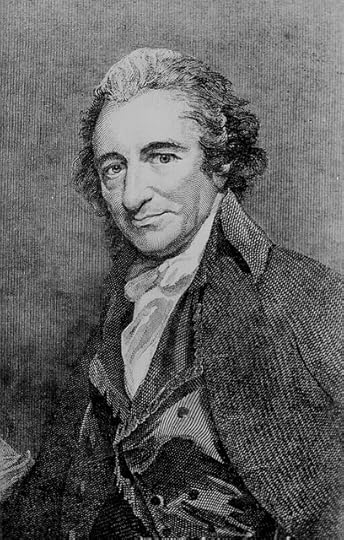

“Thomas Paine, engraving” by Marion Doss. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Thomas Paine, engraving” by Marion Doss. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Historian Ilan Rachum, who has studied the diffusion of the term ‘revolution’ from astronomy to political usage, suspects that the strong association of the word with the overthrow of James II is why the term was generally absent from eighteenth century American political discourse. The term ‘American Revolution’ appears in print in the title of a government publication, apparently for the first time, in February 1779. The report, written to Gouverneur Morris of New York, was called ‘Observations on the American Revolution.’

Thomas Paine himself preferred the usage ‘American Crisis,’ but when the Abbé Guillaume Thomas François Raynal, a French theologian, published Revolution in America in 1781, Paine found himself forced to use that term in his response. Raynal had suggested that American independence was motivated more by a refusal to pay taxes rather than principles of democratic self-government. Paine, on retainer to the new government, responded in 1782 with ‘A Letter Addressed To The Abbe Raynal, On The Affairs Of North America; In Which The Mistakes In The Abbe’s Account Of The Revolution Of America Are Corrected And Cleared Up.’

The causes of the American Revolution, Paine argued, were unique in that ‘the value and quality of liberty, the nature of government, and the dignity of man… produced the Revolution, as a natural and almost unavoidable consequence.’ In Paine’s letter, the ‘American Revolution’ meant a change of government in the direction of a worthier, more deserving political system, not merely the replacement of one leader for another.

Raynal’s Revolution of America and Paine’s critique received wide public attention. Soon, other works began to appear, referring to the American Revolution as Paine did, including Richard Price’s 1784 Observations on the Importance of the American Revolution, and the Means of Making it a Benefit to the World. By 1789, when David Ramsay’s work, The History of the American Revolution, appeared in Philadelphia, the new usage had already gained a wide currency.

As it turns out, we Americans were the real ‘revolutionaries’ in this case–we had revolutionized the meaning of a word.

Image Credit: “Redcoats & Rebels Revolutionary War Reenactment” by Lee Wright. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Talkin’ about a ‘Revolution’ appeared first on OUPblog.

A Yabloesque variant of the Bernardete Paradox

Here I want to present a novel version of a paradox first formulated by José Bernardete in the 1960s – one that makes its connections to the Yablo paradox explicit by building in the latter puzzle as a ‘part’. This is not the first time connections between Yablo’s and Bernardete’s puzzles have been noted (in fact, Yablo himself has discussed such links). But the version given below makes these connections particularly explicit.

First, we should look at Bernardete’s original. Imagine that Alice is walking towards a point – call it A – and will continue walking past A unless something prevents her from progressing further. There is also an infinite series of gods, which we shall call G1, G2, G3, and so on. Each god in the series intends to erect a magical barrier preventing Alice from progressing further if Alice reaches a certain point (and each god will do nothing otherwise):

(1) G1 will erect a barrier at exactly ½ meter past A if Alice reaches that point.

(2) G2 will erect a barrier at exactly ¼ meter past A if Alice reaches that point.

(3) G3 will erect a barrier at exactly 1/8 meter past A if Alice reaches that point.

And so on.

Note that the possible barriers get arbitrarily close to A. Now, what happens when Alice approaches A?

Alice’s forward progress will be mysteriously halted at A, but no barriers will have been erected by any of the gods, and so there is no explanation for Alice’s inability to move forward (other than the un-acted-on intentions of the gods, which isn’t much of an explanation). Proof: Imagine that Alice did travel past A. Then she would have had to go some finite distance past A. But, for any such distance, there is a god far enough along in the list who would have thrown up a barrier before Alice reached that point. So Alice can’t reach that point after all. Thus, Alice has to halt at A. But since Alice doesn’t travel past A, none of the gods actually do anything.

Now let’s change the puzzle a bit. Imagine that Alice is an expert logician enjoying her morning walk (which, as usual, passes through point A). Alice will continue walking unless she hears someone utter a paradoxical sentence or set of sentences. Hearing a paradox is paralyzing to Alice, however. Upon hearing such a thing, she will instantly stop in her tracks (and she is able to detect paradoxes instantaneously, the minute they are uttered). Finally, Alice walks in total silence, never uttering a word.

Abstract Light Painting, by Alexander Nie. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Abstract Light Painting, by Alexander Nie. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.As before, we also have an infinite series of gods G1, G2, G3, … and each god intends to act in a particular way if Alice reaches a certain point on the path past A. But now they are not erecting barriers, but are instead merely making utterances:

(1) G1 will say:

“Everything the other gods have said so far is false.”

if Alice makes it ½ meter past A.

(2) G2 will say:

“Everything the other gods have said so far is false.”

if Alice makes it ¼ meter past A.

(3) G3 will say:

“Everything the other gods have said so far is false.”

if Alice makes it 1/8 meter past A.

And so on.

In short, each god in the series will accuse all of the other gods who have already spoken of being liars, if Alice makes it far enough. Now, what happens when Alice approaches A?

Again, Alice’s forward progress will be halted at A: Imagine that Alice did travel past A. Then she would have had to go some finite distance past A. But, for any such distance, there is a god far enough along in the list (in fact, infinitely many of them) who would have said:

“Everything the other gods have said so far is false.”

before Alice reached that point. Let Gm be any one of the gods whose point Alice has passed. Notice that if Alice passed god Gm, then she also passed all of Gm+1, Gm+2, Gm+3… Now, Gm uttered:

“Everything the other gods have said so far is false.”

when Alice passed the appropriate point (that is, when Alice has reached 1/(2m) meters past A). But before that each of the gods whose number is greater than m (i.e. Gm+1, Gm+2, Gm+3,…) will have already said the same thing about the gods who spoke before them. As a result, Gm’s utterance can be neither true nor false.

Assume that Gm’s utterance is true. Gm’s utterance amounts to his saying that each of Gm+1, Gm+2, Gm+3,… was lying when they made their respective utterances. So each of Gm+1, Gm+2, Gm+3,… must in fact be lying. But then each of Gm+2, Gm+3, Gm+4,… must be lying. But Gm+1’s assertion that:

“Everything the other gods have said so far is false.”

is equivalent to saying that each of Gm+2, Gm+3, Gm+4,… is lying. So Gm+1 is telling the truth. Contradiction, so Gm cannot be telling the truth.

Thus, Gm utterance must be false. But we can run the same argument given in the previous paragraph on Gm+1, Gm+2, Gm+3,… just as easily as on Gm (after all, if Alice passed the point at which Gm makes his utterance, then she also passed all the points corresponding to Gm+1, Gm+2, Gm+3,…). Thus, all of Gm+1, Gm+2, Gm+3,… are lying as well. But then Gm’s assertion that:

“Everything the other gods have said so far is false.”

is true after all. Contradiction again.

Note: The reader who finds the previous two paragraphs difficult may want to consult my previous discussion of the Yablo paradox here.

Thus, Alice cannot walk any distance past A, no matter how short, since doing so would mean she would have to pass a point at which a paradox had already been uttered. So she halts when she reaches A. But, since she doesn’t pass A, no one (neither Alice nor any of the gods) has said anything. So what, exactly, stopped Alice?

The post A Yabloesque variant of the Bernardete Paradox appeared first on OUPblog.

July 11, 2015

Swear words, etymology, and the history of English

Have you ever noticed that many of our swear words sound very much like German ones and not at all like French ones? From vulgar words for body parts (a German Arsch is easy to identify, but not so much the French cul), to scatological and sexual verbs (doubtless you can spot what scheissen and ficken mean, but might have been more stumped bychier and baiser), right down to our words for hell (compare Hölle and enfer), English and German clearly draw their swear words from a shared stock in a way that English and French do not. Given that nearly two thirds of the words in English come from Romance roots and only a quarter from Germanic roots, this seems odd.

English is a language whose vocabulary is the composite of a surprising range of influences. We have pillaged words from Latin, Greek, Dutch, Arabic, Old Norse, Spanish, Italian, Hindi, and more to make English what it is today. But the story of English is above all the story of two languages that were thrown together almost one thousand years ago and have vied with one another for possession of our vocabulary ever since. These languages are Old English and Old French; the event that bound them was the Norman Conquest, the culmination of a dispute between Harold Godwinson and William, Duke of Normandy, over the succession to the throne of England. With Harold’s death at the battle of Hastings (14 October 1066), William seized the kingdom for himself and his heirs; so effectively did he break English power that by 1086, more than 95% of land in England was in Norman hands.

High talk and low talk

Following the conquest, England was thus a two-tiered society, divided upon linguistic grounds. The peasants, who served, spoke a West Germanic language, Old English, the ancestor of both modern English and modern German. The nobles, who ruled, spoke Old French, a Gallo-Roman dialect descended from Latin and spoken in northern France, the ancestor of modern French. Here, then, is the answer as to why our swear words sound so much like German ones; it is precisely because this language is ‘vulgar’ (a word derived from Latin and meaning ‘of the crowd’). Those words that we now call swear words have acquired their power to offend, at least in part, because a long-term cultural prejudice has taught people to view the French vocabulary of the conquerors as elevated and cultured and the Germanic vocabulary of the conquered as distasteful and crass.

The story is more interesting, however, than a simple tale of Romance words ‘good’, Germanic words ‘bad’. There’s also the question of ‘register’—that is, the context in which certain words are used and the impression that they convey. That it was the Romance language superimposed upon the Germanic and not the other way around is visible in the way that some of our most fundamental vocabulary maps onto French and German. Words that define the most basic aspects of life and society often have Germanic origins. Take the body. Anyone can recognise the German Haar, Hand, and Fuss; their French equivalents (cheveu, main, and pied) are less obvious. And whilst the German family looks familiar, with its Vater, Mutter, Bruder, and Schwester, the French one, with père, mère, frère, and sœur looks distinctly foreign. There may be fewer Germanic words in English, but the Germanic root gives most of the words we use in everyday speech; of the 100 most used words in English, almost all are Germanic (as is every word in this sentence, aside from sentence).

The rich man in his castle, the poor man at his gate

The two-tiered society of post-Conquest England is also visible in modern English when we examine the differing contexts in which we use words of Germanic and Romance origins that once meant the same things. Take our word for the place a person lives. The word house comes from an Old English word hus (modern German Haus) and provides the standard vocabulary unit in our language; a house can be anything from a ramshackle hut to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. However, we have another word in English that also means ‘house’, but that carries with it connotations of status, luxury, and wealth. That word is mansion, from Old French mansion (modern French maison), meaning ‘residence’ or ‘home’. A peasant would have called his home a hus, but a lord would have called his a mansion, and over time both words have entered into the fusion that is modern English. The French word, however, has encoded the historical bias that made a mansion grand.

Another wonderful example of this process is the way we refer to animals. Consider the modern words for a number of common animals, farmed in England since time immemorial. The words sheep, cow, and pig all have clear Old English ancestors (sceap, cu, and picg) and so their names clearly come from Germanic roots. Old French, however, has passed its words for these animals into modern English as well, but not, perhaps, in a way we might instantly expect. What did the Normans call sheep, cows, and pigs? They called them moton, buef, and porc, words which survive in modern English not as the names for the animals themselves, but rather as the names for their meat: mutton, beef, and pork. The French speaking aristocrats who ruled the kingdom might go weeks without having to speak about the animals that dotted the countryside, but they would see their meat every day; in the field, a cow might be a cu, but on the table it was buef.

A certain je ne sais quoi

Whether you know much about the evolution of English or not, you’re actually already aware of this phenomenon, even if only dimly. It is programmed into our thinking, even in the twenty-first century, that Romance language gives a loftier style whilst Germanic words are somehow common. George Orwell lamented this tendency in his masterful 1946 essay, ‘Politics and the English Language’, and we enact that prejudice ourselves when we try to formalize our own speech and writings by ornamenting verbiage with Latinate loquacity. The impact of the Romance is amusingly highlighted in Poul Anderson’s 1989 article, ‘Uncleftish Beholding’, a description of the basics of atomic theory using only Germanic words and Germanic principles of word formation:

With enough strength, lightweight unclefts can be made to togethermelt. In the sun, through a row of strikings and lightrottings, four unclefts of waterstuff in this wise become one of sunstuff. Again some weight is lost as work, and again this is greatly big when set beside the work gotten from a minglingish doing such as fire.

There’s a kind of archaic poetry to this, and our culturally programmed preference for Romance words shouldn’t blind us to the beauty that lies in our Germanic lexicon. So cleave to the Germanic wordhoard, lest your swearing grow romantic.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Hate & Anger” by Timothy Vogel. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Swear words, etymology, and the history of English appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers