Oxford University Press's Blog, page 642

July 16, 2015

This land is your land

Seventy-five years ago folk singer Woody Guthrie penned the initial lyrics to “This Land Is Your Land,” considered by many to be the alternative national anthem. Sung in elementary schools, children’s summer camps, around campfires, at rallies, and during concert encores, “This Land Is Your Land” is the archetypal sing-along song, familiar to generations of Americans. But what most do not know is that Guthrie, the “Oklahoma Cowboy,” actually wrote the song in New York and that its production and dissemination were shaped by the city’s cultural institutions. Indeed, “This Land Is Your Land” is essentially an urban creation.

From the moment of his arrival in 1940, New York at once exhilarated and exasperated Woody Guthrie. In his first days in Manhattan, he marveled at Midtown skyscrapers and delighted in the frenzied pace of crowds on the streets. But he also roamed the Bowery, the city’s skid row, a national synonym for despair and penury. Lined with dilapidated flophouses and disreputable saloons, the Bowery left Guthrie “disgusted” with deprivation in New York and motivated him to write the song “I Don’t Feel at Home on the Bowery No More.” The city’s impoverished conditions became a muse for the Dust Bowl troubadour, just as they would be later on for such artists as Lou Reed (“Dirty Boulevard”) and Nas (“NY State of Mind”.)

Irregular in his hours, often physically disheveled, and seemingly always toting a guitar, Guthrie was a hard guest to accommodate. He lived in various places before checking into the ramshackle Hanover House, on the corner of 43rd Street and Sixth Avenue (currently the site of the International Center of Photography.) On 23 February 1940, he sat in his room and began to compose a song, inspired largely by his recent hitchhiking trips across parts of the country. On the road, Guthrie developed an appreciation for the natural beauty of America.

The other spur was Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” sung by Kate Smith, heard constantly on radios and jukeboxes nationwide. The patriotic tune, in the form of a prayer, irritated Guthrie. It seemed smug and nonsensical, out of touch with the Americans he had met in migrant camps and under railroad bridges. It had nothing to do with his people from Pampa, Texas or Okemah, Oklahoma, struck by the Dust Bowl and dispossessed of their farms.

Photo Credit: American Flags, Washington monument, Washington by Nuno Caruso. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr

Photo Credit: American Flags, Washington monument, Washington by Nuno Caruso. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via FlickrGuthrie ripped out a piece of paper from his notebook and started to craft a rebuttal to Berlin’s “God Bless America.” He wrote “God Blessed America” on top. Guthrie based the melody on the Carter Family’s “When the World’s On Fire,” itself derived from the Baptist hymn “Oh My Lovin’ Brother.” He jotted down verses that celebrated the scenic majesty of the country and political lyrics that questioned the sanctity of private property, a fundamental component of capitalism. In contrast to Irving Berlin, Guthrie was optimistic but not Pollyannaish about the promise of America, and was not about to overlook the nation’s shortcomings.

At the bottom of the page, Guthrie added, “All you can write is what you see.” He put the piece of paper away and ignored the song for four years.

In April 1944, Guthrie began to record songs at Moe Asch’s studio in midtown Manhattan, on 117 West 46th Street. Moe Asch recorded mostly Yiddish music for his small Asch-Stinson label but also had produced albums by Lead Belly and Pete Seeger. Guthrie and Asch impressed each other immediately.

On 25 April 1944, the date of the last session, Guthrie recorded 34 songs, including “God Blessed America,” the parody of the Irving Berlin tune that he had written four years earlier. In his log, Asch jotted down the title as “This Land Is My Land.” The song did not receive any special attention that day. At some point, Guthrie had modified the lyrics. At the end of each verse, he substituted “This land was made for you and me” for “God blessed America for me.”

The song witnessed other alterations. In 1945, Guthrie performed “This Land Is My Land” on the radio on WNYC’s American Music Festival and on WNEW’s The Ballad Gazette. He also published it in 1945 in his songbook Ten of Woody Guthrie’s Songs, Book One. In the songbook, Guthrie omitted the two political verses about private property and people on relief. The Great Depression lyrics lacked resonance at the end of the war, a time of intense patriotism and nearly full employment.

In 1951, Moe Asch released “This Land Is My Land” on the third volume of his Songs to Grow On, a children’s song collection for his Folkways Records label. Cognizant of the audience and perhaps wary of the Red Scare, Asch, too, left out the political verses. In 1952, Decca recorded “This Land Is My Land” but did not release it. In 1956, Ludlow Music published it, vastly increasing the circulation of the song. During the 1960s, numerous artists performed renditions of the tune, eventually known as “This Land Is Your Land.” Pete Seeger and Guthrie’s son Arlo typically included the political verses.

To many people, “This Land Is Your Land” represents America’s best progressive and democratic traditions. A particularly poignant version was performed on 18 January 2009, at President Barack Obama’s Inaugural Celebration at the Lincoln Memorial. Bruce Springsteen, Pete Seeger, and Seeger’s grandson Tao Rodriguez-Seeger sang it with verve, with the elder Seeger thrusting his arms in the air and leading the crowd. Born out of an author’s personal experiences outside and inside the nation’s greatest metropolis, “This Land Is Your Land” sprung to life in a distinctive New York cultural environment. Like many other musicians before and after, whether Duke Ellington or Patti Smith, Woody Guthrie was able to pursue his artistic dreams in New York and, in the process, make invaluable contributions to American culture.

Featured Image: Acoustic Guitar. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post This land is your land appeared first on OUPblog.

What makes Earth ‘just right’ for life?

Within a year, we have been able to see our solar system as never before. In November 2014, the Philae Probe of the Rosetta spacecraft landed on the halter-shaped Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. In April 2015, the Dawn spacecraft entered orbit around the largest of the asteroids, Ceres (590 miles in diameter), orbiting between Mars and Jupiter. And in July, the New Horizons mission made the first flyby of the dwarf planet Pluto, making it the most distant solar-system object to be visited. Other spacecraft continue to investigate other planets, for example, Cassini (whose Huygens probe landed on Titan) studies Saturn and its moons, and Orbiters and Rovers are exploring Mars.

The cameras on such spacecraft return fascinatingly beautiful images (see, for example, NASA’s Solar System Exploration). But they show a deadly beauty, hostile to life as we know it. No planet in the solar system other than Earth is able to support human life, unless humans bring oxygen, food and shelter with them, and even then it would only be for short, dangerous visits. Among the many exoplanets discovered outside our solar system, some may be Earth-like, but most clearly aren’t.

What makes Earth ‘just right’ for life? Part of the answer is that the environment has shaped life just as life has shaped its environment. In other words, Earth itself was ‘terraformed’ by the life it supported over time. For example, the large fraction of pure oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere wasn’t a condition for life to develop on this planet, but a consequence of it. Photosynthesis, first by cyanobacteria and later by plants, started in a nitrogen-carbon dioxide atmosphere at least some 2.4 billion years ago, ultimately resulted in 21% molecular oxygen by volume.

Comet 67P on 7 August (a) by the European Space Agency CC BY-SA 3.0-IGO via Wikimedia Commons.

Comet 67P on 7 August (a) by the European Space Agency CC BY-SA 3.0-IGO via Wikimedia Commons.It appears that what was essential to life on Earth from the outset was the abundance of liquid water. And that has to do with the irradiation of the Earth by sunlight; closer to the Sun would be too warm, further too cold. A somewhat heavier Sun would not have provided stable irradiation for almost five billion years. A lighter Sun would have its ‘habitable zone’ so close that magnetically-driven ‘weather in space’ and gravitational tides would likely pose severe hazards to life.

The abundance of water in the Earth’s oceans and atmosphere caused ‘geochemical weathering’ of rocks and soil, a chemical process that removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and stores it in sediments. This process removed much of the carbon dioxide in Earth’s early atmosphere, but continued sequestration would ultimately remove so much that plants couldn’t survive. As plants ‘breathe in’ carbon dioxide to grow, this would mean no food, and ultimately no oxygen for mammals, including humans. Carbon dioxide is, however, brought back into the atmosphere by volcanic eruptions (with fossil fuel burning as a modern-day additional source). Volcanism works because of the high temperature inside the Earth, which drives plate tectonics and its associated volcanic eruptions. It also happens to drive the magnetic dynamo that shields life on Earth from hazardous cosmic rays from the Sun and throughout the Galaxy.

That Earth still has an active dynamo and plate tectonics is a consequence of its size. Had Earth been smaller, like Mars or like the Moon, its interior would have cooled off so much by now that neither of these processes would work any more. It is also likely a consequence of the presence of water, which works to promote plate tectonics, and removing water from a planet can help stop its plate tectonics. This appears to have happened to Venus, being closer to the Sun than Earth.

However there are other factors associated with the Earth being ‘just right’ for the life that it supports. The sciences that look into this are astrobiology (focusing on the biological aspects), geology (focusing on planetary properties), and heliophysics (looking at the physics of the sun-space environment). Exploring the universe around us, they enable an ecological understanding of why we live in our exact environment, and where else in the Galaxy we might look for similar conditions. As we have no means of interstellar travel, and as interplanetary travel doesn’t get us to another suitable environment, we have only this one oasis, Earth, to call home.

Featured image credit:The Earth seen from Apollo 17 by NASA/Apollo 17 crew; taken by either Harrison Schmitt or Ron Evans. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What makes Earth ‘just right’ for life? appeared first on OUPblog.

What stays when everything goes

Imagine the unimaginable. Suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), the person with whom you shared most of your life has forgotten who you are, and even worse, can no longer remember their own experiences, their relationships, and how to behave appropriately in everyday situations. But although most of their long-term memory is heavily impaired, they may continue to relate astonishingly well to autobiographically relevant pieces of music.

After several years of this disease, Turner’s mother-in-law “ED” (a clergyman’s widow) and Jacobsen’s partner’s grandmother “SB” had each lost almost all ability to recognize and recall. But although barely able to identify their children, or even themselves, they could both clearly recognize familiar music. In church, ED joyfully led the congregational singing of less well-known hymns, and SB sang along with great enthusiasm to recordings of nursery rhymes that she used to sing to her children. Even more strikingly, their response to the music gave the impression that they were touched by something that was no longer accessible by looking at once-familiar faces, nor by reminders of autobiographical events, nor by involvement in often-encountered everyday situations. Music seemed to establish a secure connection and willingness to actively communicate that was hard to achieve by other means. The act of hearing and singing familiar songs perhaps induced a sense of security, confident social interaction, and simple pleasure that Alzheimer’s patients rarely experience. Their moments filled with familiar music could be their only times without great doubts and anxious questionings of their state.

This almost paradoxical ability of ED and SB, also described by Oliver Sacks in his book Musicophilia, together with conflicting scientific views on the preservation of musical memory in Alzheimer’s, gave us the initial impetus for our study.

To begin with, we needed to face the challenge that musical memory itself is not yet well understood. While the brain’s temporal lobes have often been suggested as crucial for musical memory, as well as for autobiographical memory and memory of facts, these brain areas are generally affected early and severely in the progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. So this suggestion was quite inconsistent with the frequent anecdotal observations of musical memory preservation in Alzheimer’s. Because there are few neuroimaging studies of long-term musical memory, and none that met our rigorous standards, we had to devise a novel experimental paradigm, and an appropriate analysis strategy, to locate brain areas most crucial to this human capability.

Image by Sven Schiemann. Used with permission.

Image by Sven Schiemann. Used with permission.To achieve this, we played carefully controlled excerpts of well-known, recently acquired, and previously unknown musical pieces to young healthy human subjects, while recording their brain responses with ultra-high-field functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). This gave us exceptionally high sensitivity and precise spatial localization. From the fMRI recording during music listening, we could determine where patterns of brain responses were distinctive for these different levels of music familiarity. Using a machine learning technique, we could identify areas crucial to musical memory that provided significant information regarding whether the musical excerpt was well-known, recently acquired, or unknown. Of particular importance were areas close to the brain’ s midline, remote from the temporal lobes, specifically the caudal anterior cingulate gyrus and the ventral pre-supplementary motor area. This was rather surprising, because these areas are not usually considered strongly relevant to any kind of memory, although some data already exist suggesting that they are involved with music familiarity judgments. On further consideration, however, we came to recognize that because most conventional music depends on sequences of expectations and their fulfillment, it is at least plausible that these regions — often associated with sequence planning, sequence evaluation, and complex motor sequences — could indeed be fundamental to the formation of musical memory.

The second part of the study investigated the fate of these musical memory areas in patients suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease. We hypothesized that such areas would be relatively spared in the progression of this disease. Using 20 Alzheimer’s subjects and 34 healthy controls, we evaluated three essential Alzheimer’s biomarkers within the musical memory regions that we had discovered in healthy young subjects, and compared these values to biomarker severity in the rest of the brain. This clearly showed that the areas we found to be crucial to musical memory are among the least affected by advanced Alzheimer’s in the entire brain.

To our knowledge, this is the first study showing that regions crucial to musical memory coding are strikingly well preserved in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, our results support the idea that music is remembered implicitly, akin to remembering a complex series of movements, rather than as a discrete entity or specific countable events.

We hope that this work raises many interesting new questions, and that it provides insights that can help in the management of those who suffer from Alzheimer’s Disease and other forms of dementia, where every moment of joy and peace is valuable. If music as a tool can create such states, we need to understand and use it.

Featured image: Music, Notes, Clef, Sound. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What stays when everything goes appeared first on OUPblog.

July 15, 2015

The history of the word “bad”, Chapter 3

The authority of the OED is so great that, once it has spoken, few people are eager to contest or even modify its verdict. The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology adds perhaps (not probably!) to Murray’s etymology, cites both bæddel and bædling (it gives length to æ in both words) and adds that there have been other, more dubious conjectures. But it has been known since at least the fifties of the nineteenth century that before bade (the earliest recorded form of bad) surfaced in a Middle English text (1297), it constituted part of proper names. Sometimes it was an element of compounds, but it also occurred as Badde. Medieval nicknames, which later became accepted given names, were often of the most offensive kind or resorted to the humor that makes us wince in embarrassment. A similar chain of events (a name, probably a nickname, and then a regular word) is known from the history of lad.

The only original work on bad written since the publication of The Century Dictionary is the article by Richard Coates, to which I referred in Chapter 2. It deals with personal and place names. Coates concluded that the vowel in badde must have been short, but he did not press this point and admitted that the situation is in part unclear. And so it is. No doubt, the regular spelling with dd presupposes a short vowel. The relatively few Old English words with long vowels before a double consonant had r, l, or m in close proximity, such as næddre “adder” (a nadder became an adder in the modern language; German still has Natter), nædl “needle,” maþþum “treasure,” and the like. Badde does not belong to this group. If badde had a short vowel, its derivation from bædan “oppress; defile,” advocated by Koch, Kluge, and Holthausen (see the previous post), seems to be ruled out. Bædan “oppress” certainly had a long vowel, as follows from its cognates (Gothic baidjan and others). The origin of the other bædan is more problematic, but the presence of a long vowel in it is also assured. The OED online takes cognizance of Coates’s publication but remains noncommittal.

The adder lost its n but none of its poison

The adder lost its n but none of its poisonWe know that Middle English had the adjective badde. What could be its origin? All serious sources emphasize the fact that bad lacks cognates in other languages. This consensus may be wrong. Hermann Jellinghaus, an eminent student of Low (that is, northern) German, discovered an 1828 dictionary of a dialect in which the adjective but “unripe; simple-minded, stupid” (the German glosses are unreif and einfältig) turned up and compared it with bad. Even if this but is indeed a cognate of bad, we don’t know how to make the next step. Much more important is the tiny article by J. H. Kern, published in the main linguistic Dutch periodical (and in Dutch). The title appears in my bibliography of English etymology at bad, so that I’ll dispense with references (the same holds for Jellinghaus) and will only say that Kern was a first-class philologist and both Murray and Bradley had a high opinion of him. In Middle Dutch, the diminutive badderken “doll; pet child” has been found, but it turned up only once in a text from Brabant. The authors of the great Middle Dutch dictionary wondered whether it was an error for the much better known babbaerdeken, but Kern was justified in accepting the form as it was recorded.

Not necessarily bad but self-willed and unpredictable

Not necessarily bad but self-willed and unpredictableThe syllable –ken of badderken is a diminutive suffix. Thus, if the word is genuine, its stem is badder-. Kern asked: “Can the unattested badder not be connected with Old Engl. bæddel?” He refused to discuss the relations between the suffixes -el (English) and –er (Dutch). I think it will be rash to ignore the Middle Dutch form and will now say what I think about the ultimate origin of bad. Scott made a legitimate point when he asserted that bad was probably a baby word, like booger and several others he cited, though, in my opinion, dissimilation (ba–ba to ba–da, to badda) played no role in its history. Bad must indeed have served to warn children of danger, and I suggest (here I am on much more slippery ground) that it was often pronounced emphatically, with a long vowel, exactly like Modern Engl. bad. We often hear ba-a-ad! Even pronouncing dictionaries register this variant. The stylistic register of the Old English word prevented it from appearing in the literature of the period, even in the glosses. Middle Dutch badder- “doll; pet child” bears out the idea that we are dealing with a baby word, but I would risk adding a last detail. The OED cites the rare and obsolete noun badde “cat.” Its origin is said to be unknown. Nothing is more natural than using a baby word for cat (compare puss and pussy). It did not necessarily refer to the nasty pet, a creature like “The Cat that Walked by Himself,” immortalized in Kipling’s tale, but cats are unpredictable creatures.

If I am right, bad is not a back formation on bæddel; on the contrary, bæddel “a bad man” was formed from it. Coates arrived at the same conclusion but by his own reasoning. Similarly, there is no need to derive bad from some past participle. More likely, the sound complex bæd existed even in Old English, though we see it only as the root of the verb bædan. In it the vowel was long. Bædan “oppress” and bædan “defile” could have been coined at different times but from the same root. In Old English, bæd remained a baby word (the standard adjective for “bad” was yfel “evil”). It left the nursery around the thirteenth century, at which time it could already function as a nickname. As already pointed out, the borderline between a medieval nickname and a given name is often blurry. The vowel in bæddel was, to the extent that we are allowed to depend on its spelling with dd, short. Just as a long vowel can serve emphasis, so can a long consonant (hence perhaps dd). The vowel length in bædling is indeterminate.

In dealing with words like bug, boogey and their kin, the concept of the congener becomes vapid. Is Russian buka, a synonym of Engl. boogey, its congener? The same question should be asked about Old Engl. bad(d)-, Middle Dutch badd-, and Modern Low German but. They resemble the members of the international boogey family. Wearing the same uniform does not presuppose consanguinity. Therefore, the idea that bad is related to Classical Greek spatalós (“luxurious”; W. Freeman Twaddell) leaves me unimpressed. The Germanic adjective hardly had regular cognates elsewhere in Indo-European. Yet the Old Saxon verb udarbadon “to frighten” is worthy of mention in this context (Old Saxon is a Germanic language once spoken on the northwest coast and in the Netherlands.) This verb has been compared with some Celtic forms, but I doubt that this comparison stands. Old Saxon scholars refuse to decide whether the vowel a in –badon was short or long. It was probably long, because undarbadon seems to be related to Old Engl. bædan. If it had the same root as Engl. bad, Kern’s guess gets an important confirmation. Oppression and defilement are bad, and so is fright. Undar– means “under,” so that the verb might refer to “being under a bad thing.” Our baby word appears to have made its way through the entire North Sea region. If so, the Anglo-Saxons brought it to Britain from their continental homeland.

This is the end of a long journey in search of a good etymology of the English word bad. If my considerations deserve credence, I’ll be happy. But if someone has enough ammunition to find a better etymology, I’ll be the first to rejoice.

Image credits: (1) European Adder. © Andy_Astbury via iStock. (2) Rudyard Kipling’s “The cat that went by himself” 1902 via Boop.org.

The post The history of the word “bad”, Chapter 3 appeared first on OUPblog.

The best of a decade on the OUPblog

Wednesday, 22 July 2015, marks the tenth anniversary of the OUPblog. In one decade our authors, staff, and friends have contributed over 8,000 blog posts, from articles and opinion pieces to Q&As in writing and on video, from quizzes and polls to podcasts and playlists, from infographics and slideshows to maps and timelines. Anatoly Liberman alone has written over 490 articles on etymology. Sorting through the finest writing and the most intriguing topics over the years seems a rather impossible task.

Yet this was my charge as editor as we planned our anniversary celebrations. Fortunately, I was able to call on our former blog editors, a host of editors across the Press, and a number of our regular contributors to make their own choices. The blog posts selected have been compiled below, along with commentary, and they have also been made into a free e-book, The OUPblog Tenth Anniversary Book: Ten Years of Academic Insights for the Thinking World, available in PDF, Kindle, Nook, Google Play, iBooks, and Kobo.

“The fall of Rome—An author dialogue” (Part 1; Part 2) with Bryan Ward-Perkins and Peter Heather

“One of the most memorable pieces for me was the dialogue I facilitated between Bryan Ward-Perkins and Peter Heather. Somehow we had two books on the fall of the Roman Empire coming out the same time. Fortunately, the authors were also colleagues at Oxford (or friendly rivals if you ask the right one). The resulting two-post epic was a delightfully easy and open exchange that generated a considerable number of comments (at least for those early days) that ranged all the way to the American Civil War and the Sherman tank. Clearly, the readers loved it and I think the authors did, too.”

—Matt Sollars, OUPblog Founding Editor (2005–2006)

“Lincoln’s finest hour” by James M. McPherson

“To say it was hard to pick one favorite post is an understatement. Even five years after leaving OUP, I remain honored and amazed by all the incredible authors who contributed to the blog during my tenure. One post that stands out in my mind as an irrefutable favorite is James McPherson’s essay, ‘Lincoln’s finest hour.’ McPherson’s post is a strong reminder that politicians once valued the American people more than they valued campaigning for their jobs.”

—Rebecca (Ford) Bernstein, OUPblog Editor (2006–2010)

“A mystery-y-ish-y word trend: The –y suffix has gone bananas” by Mark Peters

“Though I generally prefer to write humorously, this post feels like the closest I’ve come in the blog to writing something that could be in a linguistics journal. Recording the existence of unlikely, preposterous words such as secret identity-y and mystery-y-ish-y feels like I made a nice contribution to the literature on slang morphology. I was psyched to build on the great stuff Michael Adams has done and document some seriously whacked-out words.”

—Mark Peters, OUPblog contributor

“John Lennon and Jesus, 4 March 1966” by Gordon R. Thompson

“Blogging can generate informative reader feedback, especially when some of the readers prove to have played a role in the narrative. Such was the case with “John Lennon and Jesus,” not to suggest that either the Beatle or the religious figure necessarily had access, nor that they contacted me. However, the relevant managing editor of Datebook did take umbrage after my suggestion that the reprinting and the repackaging of Maureen Cleve’s 1966 interview had partially motivated Lennon’s assassin. Of course, causal explanations often prove to be undependable, but humans do live in and react to a symbolic world with its multivariate interpretations, and one deranged individual did come to believe that a Beatle had put himself above Christianity. One consequence of the modern globalization of telecommunications and transportation has been an ongoing debate about society and religion. Revisiting how a casual comment by John Lennon about history developed into a confrontation between cultures offers a brief glimpse into the origins of the world we now inhabit.”

—Gordon R. Thompson, OUPblog contributor and author of Please Please Me

“The teal before the pink: Ovarian Cancer Awareness Month” by Gayle Sulik

“We would be hard-pressed to find anyone living in America who was not familiar with Susan G. Komen for the Cure, much less the flood of pink ribbons that descend upon us across the web, on our doorsteps, and in stores each October. Yet, for the millions of donors and race participates that Komen has amassed, few seem to know much about what the organization actually does, or where exactly the money goes. I’ve chosen to highlight the work of Gayle Sulik because she has been instrumental in bringing to light the controversies surrounding Komen and how the commercialization of breast cancer has actually helped companies profit from the disease. Her work sends the necessary message that cause marketing is not philanthropy, and not every so-called charitable organization is particularly charitable. She has challenged us to rethink the marketing campaigns that tug at our heart strings, and moreover, whether we as individuals are actually supporting the causes we have been led to believe are important.”

—Lauren Appelwick, OUPblog Editor (2010–2011)

“Nobody wants to be called a bigot” by Anatoly Liberman

“Writing a post every week for so many years, summer or winter, rain or shine, requires a lot of work, but, as I now know, the effort is worth the trouble. People respond from all over the world, ask questions, disagree, point out mistakes (catching a blogger’s errors is everybody’s favorite occupation), and occasionally praise. In etymology, good solutions published in fugitive journals and rarely read reviews often get lost: the truth has been unearthed but remains hidden and unappreciated. Dictionaries keep saying that bigot is a word of unknown origin, but I encountered an old explanation that seemed excellent to me and was happy to advertise the discovery. Also, while working on the history of bigot, I realized that beggar and bugger belong to the same “nest” and later wrote about both. And last but not least, the post has been noticed. Nowadays, to be noticed even for a brief moment is no mean feat.”

—Anatoly Liberman, OUPblog columnist and author of Word Origins and How We Know Them

“Our Antonia” by Edward A. Zelinsky

“Writing regularly for the OUPblog has been an excellent experience for me, a monthly opportunity to address pending issues of law and public policy in an increasingly important forum. However, the post I enjoyed writing most was my book review of the novel My Antonia by Willa Cather. My Antonia is a story of family, personal identity, and first love set in my home state of Nebraska. The chance to reflect on these themes makes this my favorite effort.”

—Edward A. Zelinsky, OUPblog columnist and author of The Origins of the Ownership Society

“Mars, grubby hands, and international law” by Gérardine Goh Escolar

“Wrapping up my first year as blog editor, there was a great deal of excitement around the red planet. After the phenomenal landing of Mars Curiosity in August, the initial results were eagerly anticipated. As the staff searched for people to comment, we were surprised to find an international law angle to our astronomical concerns. I couldn’t be more pleased when Gérardine Goh Escolar delivered a blog post combining such specialist knowledge with a sense of humor: the perfect combination for academic blogging.”

—Alice Northover, OUPblog Editor (2012–present)

“The dire offences of Alexander Pope” by Pat Rogers

“Pat Rogers’s post on Alexander Pope is entertaining, informative, and instructive in equal measure. Pope isn’t a popular poet in the manner of William Wordsworth, yet he’s responsible for some of the most famous phrases in the English language. In a short space Rogers tells us why The Rape of the Lock is such a brilliant poem, how Pope creates his effects, why he is such an important and influential poet and satirist, and how his targets have so many parallels in the modern world. Above all, Rogers’s enthusiasm, his combination of broad description with close reading, his erudition and ease of communication encapsulate the essence of Oxford World’s Classics—and he makes you want to read Pope!”

-—Judith Luna, Senior Commissioning Editor for Oxford World’s Classics, Oxford University Press

“A flag of one’s own? Aimé Césaire between poetry and politics” by Gregson Davis

“Davis ties together literature and politics to explore the complexities of Aimé Césaire’s thought. The post is appropriately international in scope, and Davis effortlessly integrates a brief history of postcolonial history into his account. Davis’s recollection of his personal encounters with Césaire only serves to underscore the author’s deep engagement with the issues surrounding negritude and the legacy of colonialism.”

—Timothy Allen, Associate Editor, Reference, Oxford University Press

“The G20: Policies, politics, and power” by Mike Berry

“The idea of revisiting a ‘classic’ with a mind to understanding the work in current context appeals. Published in 1958, John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Affluent Society stayed on the bestseller list for six months and has never been out of print since. As with many iconic books that transcend the disciplinary boundaries of their author, it stimulated widespread interest and heated debate, but is now more often referred to rather than read. However Galbraith’s critique of the orthodox economics of his day is, I believe, of continuing relevance, and such understandings are especially important in today’s economic climate. Mike Berry looks back from the vantage point of the present to see how well Galbraith’s analysis of affluence has fared in the intervening half-century. For the record, and as you’d expect, it covers inequality, insecurity, inflation, debt, consumer behaviour, financialization, the economic role of government (‘social balance’), the power of ideas, the role of power in the economy, and the nature of the good society.”

—Adam Swallow, Commissioning Editor, Economics and Finance, Oxford University Press

“Q&A with Claire Payton on Haiti, spirituality, and oral history” by Caitlin Tyler-Richards

“In this piece, Claire Payton discusses the problems and possibilities of her oral history work in Haiti. She raises important issues concerning doing oral history outside of her native language, and the possibility of using oral history to give voice to the voiceless. The piece also touches on the ethics and responsibilities of doing oral history in the aftermath of disaster.”

—Troy Reeves, OUPblog contributor and Managing Editor of the Oral History Review

“Lucy in the scientific method” by Tim Kasser

“I love working with psychology content because it can take you in so many surprising directions. There’s so much more to psychology than the proverbial couch! Take Tim Kasser, a professor of psychology at Knox College who studies materialism and consumer culture, among other things. Since Kasser was a teenager, he had dreamed of writing a biography of John Lennon, but it wasn’t until two decades later that he was able to apply his expertise as a research psychologist and scientist—and shed his outlook as “fan”—towards a systematic investigation into understanding Lennon through his lyrics. In this piece, Kasser outlines his three-step process for understanding the meaning behind a song. His method is rigorous, but those who, like me, remember poring over liner notes in high school will appreciate the pursuit of interpreting the language of a beloved song.”

—Abby Gross, Senior Editor, Psychology, Oxford University Press

“Neanderthals may have helped East Asians adapting to sunlight” by Qiliang Ding and Ya Hu

“This article in Molecular Biology and Evolution highlights how advances in genome sequencing, as well the analysis of ancient DNA, is helping to enhance our understanding not only of evolution but of our human history. The authors present evidence that the co-existence of Neanderthals with early humans during their migration out of Africa may have helped East Asian populations adapt to sunlight exposure. Where we come from and how we’ve developed as a species is a truly fascinating field of study, and as the science becomes more sophisticated we can uncover insights such as this which give an incredibly evocative peek into our past. “

—Jennifer Boyd, Publisher, Journals, Oxford University Press

“Thinking more about our teeth” by Peter S. Ungar

“Being in the Pam Ayres school of dental hygiene, I often find myself thinking of teeth. This is a lovely little piece that covers a great deal (as do all the VSIs) (slugs have teeth?!) and made me want to read the whole book, so I can appreciate the small miracle of those (in my case) much neglected molars and canines.”

—Luciana O’Flaherty, Publisher, Global Academic Business, and Very Short Introductions series editor, Oxford University Press

“Kathleen J. Pottick on Superstorm Sandy and social work resources”

“This brief interview encapsulates, in so many different ways, what we are all about. Here we have a social work professor who was herself impacted directly by Hurricane Sandy, forming a university-community-agency initiative designed to ensure that practitioners in the field had the information they needed in order to effectively serve their clients and communities. The product itself, the Encyclopedia of Social Work (ESW), is intended to do just that—to provide authoritative, up-to-date information to scholars, students, and practitioners where they are, and Prof. Pottick worked with partners at OUP, Rutgers, and local agencies to make this happen. It’s just a great story that shows what social workers do, how an online encyclopedia can provide a valuable service in the age of Wikipedia, and the real impact that a scholarly press can have on people in need within our own community.”

—Dana Bliss, Senior Editor, Social Work, Oxford University Press

“‘You can’t wear that here’” by Andrew Hambler and Ian Leigh

“Legal topics are often a little inaccessible, meaning that a blog post uses up several paragraphs just explaining what the problem is. Here, the title (‘You can’t wear that here’) and the first sentence (‘When a religious believer wears a religious symbol to work can their employer object?’) immediately locate the issue for the reader, leaving the rest of the article to explain the state of play and future direction of the law on wearing religious symbols in the workplace. At the time of the legal judgment that this post examines, newspapers had to try and summarise the case in terms of somebody winning or losing, while specialist legal blogs debated the judgment’s significance for specific Articles of the European Convention on Human Rights. The OUPblog piece managed to provide an accessible but nuanced explanation of the legal principles and findings yet also set out the judgment’s significance in one pithy sentence: ‘The idea that employees must leave their religion at the door has been dealt a decisive blow.’”

—John Louth, Editor-in-Chief, Academic Law Books, Journals, and Online, Oxford University Press

“Does the ‘serving-first advantage’ actually exist?” by Franc Klaassen and Jan R. Magnus

“As a fan of both sport and statistics, this post drew me in from the start. The Moneyball phenomenon is yet to hit tennis in force, and this post hints at the potential that lies within the incredible dataset the authors created for their book. However, the post equally highlights how statistics can be misrepresentative and the dangers faced when they are interrogated closely. I hope Andy Murray has read this blog!”

—Christopher Reid, Editor, Medical Books and Journals, Oxford University Press

“Transparency at the Fed” by Richard S. Grossman

“I like this post because the writing is punchy, in contrast to a lot of academic writing—including my own—that is ponderous. It is also timely, as central bank behavior and practices are—and will continue to be—a hot topic in the coming months. Finally, I like it because it uses history to illuminate an issue of contemporary policy, one of my favorite approaches.”

—Richard S. Grossman, OUPblog columnist and the author of Wrong

“Publishing tips from a journal editor: selecting the right journal” by R. Michael Alvarez

“Of the various blog posts I’ve done, I think this one is the most generally interesting. It provides some much-needed advice from the perspective of a journal editor about the matching problem that plagues many academic writers (not just in political science, but across the humanities and sciences). I also have found that authors hunger for honest guidelines about how to try to publish their material, and I believe that this post provides that perspective.”

—R. Michael Alvarez, OUPblog contributor and Co-Editor of Political Analysis

“United Airlines and Rhapsody in Blue” by Ryan Raul Bañagale

“Ryan’s blog post is a microcosm of his book Arranging Gershwin, which explores ways in which arrangements of George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue define and redefine nationalist associations, taking it from a New York soundscape to an American icon to a corporate logo to an international anthem. Like most of my favorite posts on the OUPblog, Ryan discusses a work familiar to many and points out aspects you might not have noticed, broadening your interpretation and enriching your experience of the work.”

—Anna-Lise Santella, Senior Editor, Music Reference, Oxford University Press

“Why study paradoxes?” by Roy T. Cook

“My favourite thing about the OUPblog is the diversity of the content we publish. Working on the blog every day means I get to read about fascinating subjects I know very little about. For example, articles like ‘Why study paradoxes?’ by Roy T. Cook introduced me to the concept of mathematical paradoxes. Mathematics was far from my favourite subject in school, but this article makes a very complex mathematical concept easy to understand as well as engaging and entertaining. In fact, this article captivated me to such an extent that I researched other mathematical paradoxes when I went home after work. Something I never thought I’d do!”

—Daniel Parker, OUPblog Deputy Editor (2014–present)

“Scots wha play: An English Shakespikedian Scottish independence referendum mashup” by Robert Crawford

“Shakespeare’s plays have been endlessly adapted. When done well, these adaptations can be wonderful, but rewriting and re-interpreting Shakespeare is no simple feat. Robert Crawford so brilliantly dramatized the Scottish Referendum and set it against the backdrop of arguably one of the most important works of literature that takes place in Scotland, Macbeth. It’s undeniably comedic, but there is also something somber about dramatizing one of the most important events in recent British history and relating it to a classic tale of power, ambition, and corruption.”

—Julia Callaway, OUPblog Deputy Editor (2013–2015)

“The Oxford DNB at 10: New research opportunities in the humanities” by David Hill Radcliffe

“One of the pleasures of the OUPblog is the space it offers for free thinking and for looking ahead. Here Professor David Hill Radcliffe of Virginia Tech University ponders the future for humanities research as large digital works—including the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography—are reconfigured to cast new light on the past. The potential to interconnect millions of people, events, and artefacts presents opportunities of which we’re only now becoming aware.”

—Philip Carter, Publication Editor, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press

“Facebook, the gender binary, and third-person pronouns” by Lal Zimman

“Gender and sexual identity have been powerful catalysts for change in the English lexicon in recent decades. In this post, Lal Zillman explores how new ways of thinking about gender are challenging one of the most fundamental parts of the English vocabulary: pronouns.”

—Katherine Martin, Head of US Dictionaries, Oxford University Press

“In defence of horror” by Darryl Jones

“This post by Professor Darryl Jones is, I think, an excellent example of what a blog post is capable of doing. It’s intelligently written and draws insightful parallels between the gory horror films we have watched at home or in the cinema and classical literature, where there is more gore than could potentially be shown on celluloid. Cannibal Holocaust may shock with its graphic scenes, but Euripides had a mother parading about with her son’s head on a stick thousands of years before. Professor Jones’s post is also entertaining, showing that the blog is an ideal forum for the most academic ideas to be conveyed in an engaging manner. It’s one of my favourite blog posts for all of these reasons.”

—Kirsty Doole, OUPblog Deputy Editor (2010–2014) and Publicity Manager, Oxford University Press

“Race relations in America and the case of Ferguson” by Arne L. Kalleberg

“How did a tragedy in a nondescript suburb of St. Louis, Missouri, bring race relations to the fore of American consciousness? In an interview with Arne L. Kalleberg, editor of Social Forces, Wayne Santoro and Lisa Broidy develop a framework for understanding the shooting that shook a nation, blending statistical objectivity with human nuance. Memorializing Michael Brown, they examine the intersection of policymakers, protesters, and public, uncovering not only a local but nationwide pattern of structural violence that makes ‘Ferguson more typical than atypical.’”

—Sonia Tsuruoka, OUPblog Deputy Editor (2015–present)

“The origin of work-hour regulations for house officers” by Kenneth M. Ludmerer

“The issue of work-hour regulations for house officers is the most contentious and emotional issue in medical education since the Flexner Report of 1910. The subject involves some timeless concerns in medical education—namely, the ultimate responsibility of medical education to the public, and the fact that cultural forces as well as scientific and professional developments shape the evolution of medical education and practice.”

—Kenneth M. Ludmerer, OUPblog contributor and author of Let Me Heal

“Eleanor Roosevelt’s last days” by Philip A. Mackowiak

“This blog post initially grabbed me because, though I knew how Franklin Roosevelt died (of a stroke, shortly after Yalta in 1945), I could not say the same about Eleanor Roosevelt. I was unaware of the painful, prolonged, and cruel circumstances of her death in 1962, of a bone marrow disease that was aggressively treated past the point of any hope, and contrary to her own wishes to end treatment. Here we have a case study of a famous patient’s last days, but also an introduction to changing medical views on end-of-life care. Reading how celebrities and public figures choose to die—or are denied the choice—made me think about what control ordinary people have over their treatment and care in the face of terminal illness, and sent me back to excellent recent discourse such as Dr. Ken Murray’s article in the Wall Street Journal, ‘Why Doctors Die Differently.’”

—Maxwell Sinsheimer, Editor, Reference, Oxford University Press

“Jawaharlal Nehru, moral intellectual” by Mushirul Hasan

“Mushirul Hasan’s article reflects a crucial moment for Indian scholarship. As India transforms, how does the legacy of our greatest intellectuals inform our future? And the new, global scale of our academic publishing, including scholarly blogs such as this, allows us to have this debate more openly within South Asia and beyond.”

—Sugata Ghosh, Director, Global Academic Publishing, India, Oxford University Press

“Vampires and life decisions” by L.A. Paul

“Academic philosophy has sometimes been criticized for becoming detached from ‘the real world.’ I think this is unfair: the abstract and the general are just as much part of our world as the concrete and the particular. But in recent years philosophers have increasingly focused on topics which everyone thinks about, to do with the human condition—such as emotion, happiness, the self, and the meaning of life. Laurie Paul has come up with an original approach to a practical problem which we all face: how to make big decisions about our lives, decisions that will themselves transform who we are, making us different people from the people who did the deciding. Her blog post ‘Vampires and Life Decisions’ is a vivid expression of this key idea.”

—Peter Momtchiloff, Commissioning Editor, Philosophy, Oxford University Press

“Rip it up and start again” by Matthew Flinders

“This was a piece written in a burst of New Year energy. I wanted to make a provocative argument and to say something that I thought really mattered and where there were still opportunities for change. As soon as the piece went live there was an instant online explosion of support for what I was saying. Then a senior political correspondent with the BBC penned a strong rebuttal of my argument that only served to throw petrol on the fire of a debate that was already well alight. What next? A phone call from a group of Northern MPs telling me that my piece had inspired them to start a campaign for a ‘Parliament of the North.’ Private investors, think tanks, a media launch, a national competition . . . the power of the blog.”

—Matthew Flinders, OUPblog columnist and author of Defending Politics

“Oppress Muslims in the West. Extremists are counting on it.” by Justin Gest

“The beauty of the OUPblog is its versatility. Some posts act like a flare: they burn bright for a brief spell, achieving their purpose by illuminating the landscape, but not lingering long. Others remain relevant for years after their debut, such as the numerous postings on paradoxes. To demonstrate the depth and breadth of OUP’s publishing, however, a post should meet a number of criteria. It should have a strong argument. It should stand up long after its initial posting. It should be clear, crisp, and compelling. It should be based on empirical research. And it should ideally shed light on an important issue of the day by enlisting the tools and perspectives of the academy to educate those who may not have access to long-form scholarship. Justin Gest’s piece on the self-defeating perils of Islamophobia checks all those boxes, and more.”

—Niko Pfund, President of OUP USA and Academic Publisher, Oxford University Press

“Does philosophy matter?” by Walter Sinnott-Armstrong

“This blog post was refreshing and timely—two things that I’m usually hoping for in things that I choose to read in my spare time. Sinnott-Armstrong calls out a couple important trends in philosophy that, while maybe particularly egregious in this argument-based, oftentimes macho discipline, are certain to plague others as well: the contempt for people who can’t keep up with scholarly arguments or even specific ‘in’ language and the snobbery towards authors who choose to address the wider public in books written for general readers instead of focusing on super-specialized journal articles. As someone who encounters a lot of dense philosophical prose, I hope that readers cherish what Sinnott-Armstrong says here, in practice and in spirit.”

—Lucy Randall, Editor, Philosophy, Oxford University Press

Do you have any personal favorites? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Featured image: Home office. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post The best of a decade on the OUPblog appeared first on OUPblog.

Miss Havisham takes on the London Gentleman: An OWC audio guide to Great Expectations

Perhaps Dickens’s best-loved work, Great Expectations tells the story of Pip, a young man with few prospects for advancement, until a mysterious benefactor allows him to escape the Kent marshes for a more promising life in London. Despite his good fortune, Pip is haunted by figures from his past – the escaped convict Magwitch, the time-withered Miss Havisham, and her proud and beautiful ward, Estella – and in time uncovers not just the origins of his great expectations, but the mystery of his own heart.

A powerful and moving novel, Great Expectations is suffused with Dickens’s memories of the past and its grip on the present, and it raises disturbing questions about the extent to which individuals affect each other’s lives. In this Oxford World’s Classics audio guide, listen to Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, Professor of English at Magdalen College Oxford, explore this timeless piece of literature.

Featured image: London by Montaplex. CCo Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Miss Havisham takes on the London Gentleman: An OWC audio guide to Great Expectations appeared first on OUPblog.

Who was Jonas Salk?

Most revered for his work on the polio vaccine, Jonas Salk was praised by the mainstream media but still struggled to earn the respect and adoration of the medical community. Accused of abusing the spotlight and giving little credit to fellow researchers, he arguably become more of an outcast than a “knight in a white coat.” Even so, Salk continued to make strides in the medical community, ultimately leaving behind a legacy larger than the criticism that had always threatened to overshadow his career. We sat down with Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs, author of Jonas Salk: A Life, to get to know a little more about the mysterious researcher and virologist, as well as some of his personal and professional highs and lows.

What is polio?

Why was Jonas Salk disliked by the medical community?

The man behind the lab coat

Image Credit: “Courtyard rill fountain — Salk Institute, La Jolla, California” by Jim Harper. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who was Jonas Salk? appeared first on OUPblog.

Can leadership be taught?

Leadership training has become a multi-billion dollar global industry. The reason for this growth is that organizations, faced with new technology, changing markets, fierce competition, and diverse employees, must adapt and innovate or go under. Because of this, organizations need leaders with vision and the ability to engage willing collaborators. However, according to interviews with business executives reported in the McKinsey Quarterly, leadership programs are not developing global leaders. And despite all the costly leadership training, Gallup surveys show that fewer than one third of employees in the U.S. and U.K. are engaged in their work.

Not only do these programs fail to develop leaders, executives openly say they can be destructive by wrongly assuming that one model of leadership fits all cultures and roles. The training sometimes clashes with the organization’s culture.

Can leadership really be taught? Experts have learned that people with leadership qualities can be helped to become more effective leaders. But no amount of training will make some people into the leaders organizations need.

What are the natural qualities of leadership? The answer follows from the difference between management and leadership. Management has to do with administering processes and getting tasks done. It doesn’t even require managers. A manager can give the functions of management to others. Management can be taught. Leadership is a relationship in a context. A leader cannot give away his or her particular relationship to followers. But why and how people follow the leader depends on the needs and values of followers as well as the qualities of the leader.

“The Leader”, by David Spinks. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

“The Leader”, by David Spinks. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.People follow a leader either because they have to or because they want to. People follow dictators out of fear. They are seduced by demagogues. But neither dictators nor demagogues will gain the collaborative and creative followers organizations need. The natural qualities of a collaborative leaders start with a purpose and passion for improvement that connects with followers. This improvement may be the quality of life, population health, economic development, human development, productivity. Leaders energize organizations with their purposeful passion.

Many of those who flock to leadership programs lack this kind of purpose and passion. Rather, their purpose is punching the ticket needed for promotion, especially when it comes with a certificate from a prestigious program. They can be taught to understand themselves and others, listen to others respectfully, and communicate more effectively. Although these skills may strengthen leaders, they do not create leaders.

Leadership development is best done starting with the people at the top of an organization. The focus is on creating a leadership team that shares a leadership philosophy. This includes the purpose of the organization, the practical values essential to achieve that purpose, the criteria for ethical and moral decision making, and the measurements that will support the values and purpose.

It is also important to discover the personalities of leaders and how their intrinsic motivations best fit different leadership roles. Some are visionaries, some are operational experts, some are motivated to help people or to create collaboration. They need to share a leadership philosophy and learn to work as a team.

Featured image credit: “Snow Geese 03″, by TexasEagle. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Can leadership be taught? appeared first on OUPblog.

July 14, 2015

Was the French revolution really a revolution?

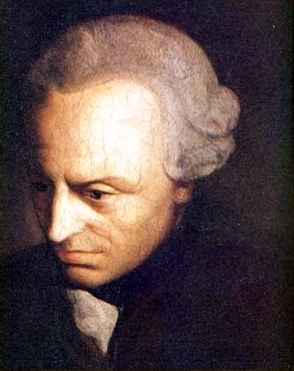

The French celebrate their National Day each year on July 14 by remembering the storming of the Bastille, the hated symbol of the old regime. According to the standard narrative, the united people took the law in its own hands and gave birth to modern France in a heroic revolution. But in the view of Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), the famous German philosopher, there was no real revolution, understood as an unlawful and violent toppling of the old regime. Writing in the wake of the events, he concluded that the King, by a “very serious error in judgment” had unintentionally abdicated and left the power to the people. Was it a revolution, or not?

Kant’s view has often been derided as a sneaky way to justify the revolution without being seen in public as doing so. Defending the revolution publicly could attract the King’s ire. The Prussian king, like all Europe’s sovereigns, feared the advancement of the revolution, and endorsements by opinion leaders might hasten that outcome. Kant, who was a professor at Königsberg, was Germany’s premier philosopher. He had many followers and defended a highly idealistic moral theory with clear affinities to the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. Thus, fear of censorship could have been Kant’s reason for misrepresenting the event as something else than a revolution.

Immanuel Kant painted portrait by Père Ubu. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

Immanuel Kant painted portrait by Père Ubu. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.But perhaps Kant’s interpretation was quite sincere? If we explore Kant’s politics in context the first thing to notice is the scope of his argument: it was about the events of 1789, not the various (and bloody) transformations of the next decade. Moreover, the events he had in mind resembled a fairly orderly democratic transition. King Louis XVI was facing a disastrous debt crisis and his juridical institutions were recalcitrant to establish new taxes to make up for the debt. To solve the situation, the absolute monarch invited all male taxpayers over 25 years of age to elect deputies to a representative assembly (called the Estates-General), which was to deliberate about solutions to the debt and on how to improve the state’s wellbeing in general. This proto-democratic assembly met at Versailles on May 5, 1789. The assembly was rigged to give veto power to the nobility and the clergy – the defenders of the old regime – but on the initiative of the commoners the assembly soon jettisoned that restriction. Asserting its sovereignty, the assembly started preparations for a new constitution enshrining the values of liberté, égalité, and fraternité.

This is usually thought of as a revolutionary act, since the King had not intended to relinquish his absolute power. He had just asked for advice on how to run the country. But according to Kant, the King’s intentions were of no consequence. Once he had committed the error of setting up a representative organ he was no longer the sovereign ruler. Absolutism relied on the notion of the monarch as the sole representative of the people (which otherwise would be a disorderly multitude). Once the monarch abandoned that task he could no longer claim to be the ruler, and his sovereignty automatically “passed to the people”.

Kant’s view was not so exotic at the time. Edmund Burke (1729-1797) too thought the King had abandoned absolute sovereignty, something that pleased the conservative publicist, who was sceptical to absolute power whether in the hands of the king or the people. But Burke and Kant disagreed on what came in its stead. Burke concluded that power reverted to the ancient constitution of the feudal society that existed prior to royal absolutism. That society had dispersed power among the church, the nobility, the commoners, and the king. Kant, however, did not consider government of such mixed nature to be a real government at all, but just a collection of groups and persons pursuing their private interests.

Moreover, the representative assembly Louis XVI had convoked was elected by the people (or at least the propertied males) and was to represent not just special groups but also the nation as a whole. This was perfectly in line with Kant’s view of popular sovereignty as the ultimate source of justice in any government. He shared this view with Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748-1836), who was not just the most influential French popular leader but also an admirer of Kant. Like Sieyès, Kant did not hate monarchy. He simply considered that once the popular assembly had been set up, the King was reduced to a constitutional monarch, with no right to reverse the process. The popular uprising that followed in the summer of 1789 and that culminated with the storming of the Bastille was not a revolution since sovereignty was already with the people. It was just the result of popular fears that the monarch would claw back the power he had abandoned.

If Kant was right, we should revise the standard narrative of the foundation of modern France. It was not a violent revolution by the courageous masses, but a democratic transition set in motion by the king himself. And perhaps France should celebrate its National Day on May 5.

Header image credit: Revolution! by doc(q)man. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Was the French revolution really a revolution? appeared first on OUPblog.

Greece’s uphill battle: a weekend roundup

With the world bracing for Greece’s exit from the Eurozone, Donald Tusk, President of the European Council, miraculously announced that a deal with the debt-crippled country had been reached. After nearly 17 hours of negotiations at the Euro Summit, Eurozone leaders extended a $96 billion bailout to Greece in what has proved to be the third bailout since 2010. As rumors continue to circulate regarding Greece’s next steps, Stathis Kalyvas, leading expert and author of Modern Greece: What Everyone Needs To Know, joined the global conversation, responding to the announcement of the recent bailout via Twitter.

[View the story “Stathis Kalyvas on the Greek economy – weekend roundup ” on Storify]

Image Credit: “A picture of some Euro banknotes and various Euro coins” by Avij. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Greece’s uphill battle: a weekend roundup appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers