Oxford University Press's Blog, page 645

July 9, 2015

The reality of the sweating brow

Many, perhaps most people listen to music with the hope that it permits them to step outside of the world as it usually is, the demands it places on us and the ugliness that so obviously mars it. People gravitate to music’s bright melodies, infectious rhythms, and perhaps especially to lyrics that, whether Beethoven’s or Beyoncé’s, give us some kind of life-raft or a phrase that clarifies our condition. What, though, can we know about music that usually contains no direct linguistic references outside of its titles? And what might the assessment of its religiosities in the crucible of race mean for us today?

Jazz is a family of musics that has always resisted its own name, its own pigeon-holing. Pianist Thelonious Sphere Monk said of jazz: “It’s about Freedom, more than that is complicated.” Guitarist Pete Cosey responded to questions about whether Miles Davis’ electric bands of the early 1970s played jazz by insisting: “don’t say that, that’s a dirty word.” Duke Ellington insisted on avoiding the term “jazz,” famously saying that there are only two kinds of music, good and bad. He heard music as “beyond category,” noting that “to have a category, one must build a wall” and that a category “is a Grand Canyon of echoes. Somebody utters an obscenity and you hear it keep bouncing back a million times.”

One of the biggest, most binding categories in American life is “race,” something underscored of late by the challenges of Rachel Dolezal and the church shootings in Charleston. Perhaps unknown to some, the history of jazz’s reception implicates it in a related history of racial representation and self-determination in America. From its inception, the music was thought by both detractors and advocates to represent a modern, urban, secular America. Critics feared its libidinous urgings and heard the absence of the sacred in its propulsive swagger. Supporters championed it as art music, the very sound of progress and sophistication. Yet aside from these and other debates, what we hear in jazz from its contested beginnings to its multiform present is the abundance of race and religion.

Blendings of the musicological, the anthropological, and the moral often characterized the alarmed reactions to jazz’s emergence, many of which sought to serve as definitions in their own way. Famed revivalist Billy Sunday, the popular advocate of Muscular Christianity, judged with characteristic bluntness that jazz was simply “bunk.” Daniel Gregory Mason called jazz a “sick moment in the progress of the human soul.” Early critics found jazz to be musically “objectionable” because there was too much “ad libbing,” its formal freedoms portending social chaos and threats to musical respectability (and all that it stood for). Others objected on political grounds to “this Bolshevistic smashing of the rules and tenets of decorous music, this excessive freedom of interpretation.” Some feared, tellingly, that “jazz could have degenerative effects on the human psyche” or that it might popularize interracial sex (even African-Americans occasionally expressed such nervousness, with one journalist wondering in print if jazz might not be a stealth weapon of the KKK).

Jazz was scorned as “barbaric, sensuous, jungle music which assaulted the senses and sensibilities, diluted reason, led to the abandonment of decency and decorum, undermined dignity, and destroyed order and self-control.” While it was embraced by marginal figures for these very reasons, jazz’s innovations more commonly induced cautions. Varèse announced that jazz was “a negro product, exploited by the Jews.” The National Socialist Party of Germany dismissed jazz as the deviant, decadent product of American cultural miscegenation, while critic Theodor Adorno worried that jazz was a low art product of the culture industry, whose “veneer” and “rhetoric of liberation” actually masked its deep conservatism. But most American audiences and observers were less concerned with socio-political implications than with the music’s alleged libidinousness. Walter Kingsley wrote in the New York Sun – echoing the music’s early syntactic associations, e.g. “jaz her up” or “put in jaz” – that “[j]azz music is the delirium tremens of syncopation.” The New Orleans Time-Picayune contrasted the rhythmic urges of jazz with the “inner court of harmony” where true music lives (so much for Art Tatum!). Jazz may have been associated with the modern (which brought together seductions and revulsions of its own, including the possibility that jazz was the soundtrack of a permissive secularism), but it was also heard as atavistic and brutish. Anne Shaw Faulkner warned that jazz “might invoke savage instincts.” To justify such alarmism, Faulkner insisted that jazz “originally was the accompaniment of the voodoo dancer, stimulating the half-crazed barbarian to the vilest deeds.” These formulations of authentic music through the dynamics of wildness and control resemble obviously long-standing characterizations and denunciations of African-American religion (or indeed of enthusiastic religion broadly speaking) as too sweaty, emotional, and erotic. They constitute a field of representational and material constraint that musician Anthony Braxton has called “the reality of the sweating brow.”

Fats Waller, seated at piano. World Telegram & Sun, photo by Alan Fisher. Library of Congress.

Fats Waller, seated at piano. World Telegram & Sun, photo by Alan Fisher. Library of Congress.This was a music that seemed to spill beyond limits – moral, musical, racial – and to many demanded their vigorous reassertion. Big band music, while it is now often remembered for its art music aspirations, often had a lower-class or lower middle-class appeal, and African American churches in particular railed against it, frequently trading in typical “devil’s music” discourse. As Ralph Ellison recalled, “jazz was regarded by most of the respectable Negroes of the town as a backward, low-class form of expression.” Fats Waller’s father was a pastor at Abyssinian Baptist Church, and as a child “[m]usic and religion became the keystones of Waller’s life.” But in response to his growing love for rag and jazz, his father told him that such music was “the devil’s workshop.” Though “jazz” has been subject to manifold misrepresentations that have obscured its musical values and complex cultural sources, its very multiplicity and instability has enabled its creative associations with religiosity beyond these early critiques: with established religious traditions, intentional communities, histories, and practices of self-cultivation beyond society’s normative gaze.

These links have long served jazz musicians as sources of identity and sustenance in a world that marginalizes creativity that cannot be easily commodified. Both these connections and their unstable fortunes are framed and constrained by a racial habitus whose long history echoes in parallel interpretations of jazz and religion. Curtis Evans documents changes occurring to the “racial habitus” between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in categorical shifts from “savage” to “emotive savant,” from degraded “animism” to “civilized religion.” “Race” came to depend on “religion” as one of its fundaments, and the racial taxonomies central to American public life took shape in part via a discourse that posited black religion’s innateness, emotionality, primitivism, and irreducibility. Both attraction and revulsion turned on these imagined traits, their wildness, their excess, their merging in spectacle. Jazz was born amidst and took shape in these very conversations linking racial imaginaries with religious naturalism and its socio-political implications. So too have jazz audiences persistently recapitulated these tropes, theorizing black creativity for the creators.

While cultured despisers may once have lamented black religion’s “heathenish observances,” “insane yellings,” and “violent contortions,” these very “unhallowed performances” and enthusiasms have long titillated white jazzbos who make of black vernacular music a cultural accessory. It was through the noisy embodiment of black religion that critics fashioned their understanding of black culture, proximity to which they warned could endanger one of falling under the spell of those sounds, lusty and immediate. Such sensory expression has also been the vehicle through which jazz’s reception dynamics reinforced key features of the racial habitus. Archie Shepp called jazz “the product of the whites – the ofays – too often my enemy,” but also “the progeny of the blacks – my kinsmen.”

American civic identity has always been bound up with, even dependent on, such representations of dark-skinned others. The extremism and abandonment associated with black expression have persistently been associated with threats to social stability or moral rectitude, even as their apparent exoticism proved alluring to audiences and observers. Musical performance, ostensibly a “natural” outlet for black expressivism, has been cited as evidence of the sorts of ontological enthusiasms rendering African-Americans unfit for other kinds of public discourse or participation. Though the music remained a source of cultural identity, and while its fluidity and evasion of reference helped fashion social criticism too, sound faced an uphill battle in enacting any change.

Albert Ayler’s dreams of universal sound were dismissed by reviewers who sneered, “[s]incerity, alas, has never yet sufficed to make notable art.” John Coltrane’s innovations were denounced as “anti-jazz.” “Jazz” again emerges as a discourse of commercial, aesthetic, and hence cultural limitation, even as its democratic freedoms are trumpeted. Attempts to move beyond its well-heeled expectations (gentlemanly swing, soul patches, Debussy-like chordal substitutions) are often met with questions about its authenticity. Braxton describes his endeavors as “creative music” since, “if I write an opera, then of course it’s a jazz opera. If I go have a hamburger, it’s a jazz hamburger.” Anthony Davis has said, “If somebody uses tradition as a way of limiting your choices, in a way that’s as racist as saying you have to sit at the back of the bus.” Clarinetist and composer Don Byron links such cultural and political limitations not only to slavery and Jim Crow but to the Tuskegee experiments conducted on African-American sharecroppers beginning in 1932, which he describes as “metaphors for African-American life.” It is easy to understand the urgency of these contentions considering that jazz criticism and “reception dynamics” have often appropriated the fantastical languages of the older (but alas, not yet extinct) racial habitus. In the 1930s, purportedly reputable jazz criticism was published with titles like “Shout, Coon, Shout!” Louis Armstrong was called a “noble savage,” whose playing exuded “intensity” and “intuition.” (Of course, Armstrong was also accused of “race betrayal” while Charlie Parker was dismissed as “too intellectual.”)

Even after such overt racism was largely erased, mid-century jazz-talk traded in a kind of exoticism and essentialism that recapitulated and echoed arguments about black religion’s “naturalism” and emotionality. Like other African-American creative traditions, “jazz” has challenged and subverted and ignored and overcome such misrepresentations and misunderstandings. And when musical expression is understood as religious – in inspiration or outcome, institution or ritual – the power of these challenges is amplified, given a larger history and cultural resonance.

If the expressive arts are, as Nathaniel Mackey says, “reaching toward an alternate reality, [and] music is the would-be limb whereby that reaching is done,” religions are like mutagens transforming already unstable identities into vehicles of new experience or change. Through shifting use of the languages and practices of “religion,” musicians have confronted or evaded or jazzed the languages and practices of authenticity that have often functioned as constraints on creativity and agency. This has not taken place through “religion” exclusively, or always even obviously. But religions, in all their unstable formations, have been “critical levers” in performance, community, and devotions; in relations of power between musicians and spirits; in meditation or trance states; in musical cosmologies that point beyond the social order. Religions are not simply counter-signs for players; rather, in these improvisations towards gods and spirits, drums are struck differently, breath becomes quickened by spirits, and ears awaken to the edifying possibilities of music that makes it possible to live differently in the world.

Featured Image: Instrument. By Drew Patrick. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post The reality of the sweating brow appeared first on OUPblog.

The US Supreme Court, same-sex marriage, and children

During the decades of debates over marriage equality in the United States, opponents centered much of their advocacy on the purported need to maintain marriage as an exclusively heterosexual institution in order to promote the well-being of children. It was therefore fascinating to see the well-being of children play a crucial role in the US Supreme Court’s ruling on the constitutionality of same-sex marriage bans in Obergefell v. Hodges, albeit not in the way opponents of marriage equality hoped.

As a constitutional matter, Obergefell is grounded in the fundamental right to marry, a right that the Court recognized in several late twentieth-century rulings, including its decision in Loving v. Virginia striking down interracial marriage bans. The Court in those cases didn’t grapple extensively with the meaning or purpose of marriage. But if there is one thing that the marriage equality movement engendered, it was repeated and wide-ranging debates over why society privileges marital relationships. It was therefore not surprising that Justice Kennedy in his majority opinion in Obergefell elaborated extensively on why the fundamental right to marry exists to begin with. One of the reasons, Kennedy explained, is to safeguard children by providing them with permanency, stability, and material benefits.

Opponents of marriage equality repeatedly claim that married mothers and fathers who are biologically related to their children constitute the optimal family form in promoting the well-being of children. Opponents then contend, with varying degrees of explicitness, that children raised by lesbians and gay men are vulnerable to greater risks of harm. Justice Kennedy, however, turned that claim on its head by pointing out that it was same-sex marriage bans which placed the hundreds of thousands of children raised by same-sex couples at risk of losing the permanency, stability, and material benefits that can accompany marriage. In other words, the Supreme Court concluded that allowing lesbians and gay men to marry individuals of their choice promotes rather than undermines child welfare.

SCOTUS DOMA 53. By JoshuaMHoover. 26 June 2013. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

SCOTUS DOMA 53. By JoshuaMHoover. 26 June 2013. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.About a decade ago, same-sex marriage opponents developed a new claim, one that focused on the well-being of the children of heterosexual parents. This claim, known as the “responsible procreation” argument, contended that marriages by same-sex couples delinked marriage from procreation, making it more likely that heterosexuals will have children outside of marriage, to the detriment of those children. If marriage is understood as having nothing to do with procreation, it was argued, straight couples would have less of an incentive to have children within marriage. Several courts, including the New York Court of Appeals, relied on this argument to uphold the constitutionality of same-sex marriage bans.

But the Supreme Court rejected such odd reasoning. As Kennedy explained, heterosexuals weigh many factors in deciding whether to marry or have children. But no heterosexual couple decides to do either depending on whether the government allows same-sex couples to marry.

It is undoubtedly the case that before the campaign for marriage equality started in earnest about twenty years ago, most people assumed both that marriage was meant only for different-sex couples and that it was better for children to be raised by heterosexuals than by LGBT people. Those assumptions were there until the end. One of the dissenting justices in Obergefell claimed it was reasonable to believe that “states formalize and promote marriage, unlike other fulfilling human relationships, in order to encourage potentially procreative conduct to take place within a lasting unit that has long been thought to provide the best atmosphere for raising children.”

But one of the main purposes of the American Constitution’s provisions protecting rights to liberty and equality is to subject these types of assumptions to empirical and logical scrutiny. The decades of constitutional litigation over marriage equality engendered countless studies, hearings and trials, briefs, position papers, and judicial rulings that examined the relationship between marriage exclusion and child well-being. At the end of the day, proponents of that exclusion were unable to establish that keeping marriage as an exclusively heterosexual institution benefits either the children of heterosexuals or those of lesbians and gay men. And that is one of the main reasons why they lost before the Supreme Court.

Featured image: US Supreme Court in Spring with Fountain. © markphariss via iStock.

The post The US Supreme Court, same-sex marriage, and children appeared first on OUPblog.

July 8, 2015

The history of the word ‘bad’, Chapter 2

Quite often the first solid etymology of an English word comes from Skeat, but this is not the case with the adjective bad. In the first edition of his dictionary (1882), he could offer, with much hesitation, two Celtic cognates of bad, one of them being Irish Gaelic baodh “vain, giddy, foolish, simple.” Much later, Charles Mackay, who believed that Irish Gaelic was the source of most English words, mentioned beud “mischief, hurt” as the etymon of bad. Richard Coates in a 1988 publication cited Cornish badus “lunatic” appearing in William Pryce’s dictionary (it is spelled lunatick there). Pryce did not deal with etymology, and Coates only says that for phonetic reasons badus and Engl. bad cannot be related because the oldest attested English forms of bad invariably had two d’s. Is badus a genuine Cornish word or a Latinization of the English adjective? Cornish bad “bad; stupid” has a solid tradition in texts, but I repeat my question: Wasn’t it a borrowing from English? In any case, Skeat’s ao and Mackay’s eu are incompatible with a in Engl. bad. Eric Partridge, whose English etymological dictionary should be studiously avoided, referred to Webster’ dictionary instead of the OED, used a wrong book for his information, and derived bad from the Celtic root bados ~ badtos “to be wide or open… the basic idea of the adjective being ‘wide-open’ (to all influences, especially the worst’).”

Now that we have left behind the boldest flights of the etymological imagination (see also Chapter 1 with its depressing title “From Bad to Worse”), we should realize that bad is a vague concept. Its vagueness makes our task especially difficult. That is bad which is not good (look up the definition of bad in dictionaries!): harmful, corrupt, deficient, and so forth. A bad man is immoral, a bad coin is counterfeit, a bad egg is rotten, a bad etymology is faulty, etc. Much has been made of the dialectal use of bad “ill, sick,” but this case is also trivial. One can be in good health, so that, when one is in pain, one, naturally, feels “bad.” The English Dialect Dictionary by Joseph Wright isolates the following senses of bad as they occur in regional speech: “profligate, tyrannical, and cruel in conduct; sick in pain; sorrowful; difficult, hard.” None of them comes as a surprise. Perhaps the only usage that is unexpected concerns the adverb, when we say I need it badly; there, badly means “very much indeed.” If we imagine that bad traces to some ancient word, it is impossible to guess what it could mean. It is “bad” to be giddy and vain (see Skeat); mischief (Mackay) is also “bad.” Therefore, when we see Skeat reconstructing the root PAD “fall,” from which bad was allegedly derived, we mercifully look the other way. Also, how could Latin p- correspond to Engl. b-?

Hermaphrodite

HermaphroditeStrangely, Skeat did not pay attention to the 1873 article on bad by Christian F. Koch. Koch’s idea that bad is related to Old Engl. badu “battle,” though wrong, is not absurd. More important, that article contained a passage which might have enlightened Skeat and to which I’ll soon return. The main event in the history being discussed here was the publication of the first volume of the OED (1884). The earliest citation of bad, written as badde, goes back to 1297, that is, to Middle English. Murray wrote that, according to the suggestion of Professor [Julius] Zupitza (he should not be confused with his son Ernst, an even more distinguished philologist), the etymon of badde is Old Engl. bæddel “hermaphrodite.” The consonant l was allegedly lost as in much, from mycel, and in a few other words, while the sense development from “effeminate” to “bad” looked acceptable: all deviations from the average physical norm were considered “bad.” If this etymology is correct, bad has always had a short vowel.

In 1883, so exactly between the dates at which Skeat’s dictionary and the first volume of the OED were published, Gregor Sarrazin’s one-page article appeared. In it he traced bad to Old Engl. gebæded (long æ!), the past participle of bædan “to afflict, oppress”; the letter æ had the value of a in Modern Engl. add. My parenthesis with an exclamation mark is needed because, according to some sources, Old English also had bædan “to defile” with short æ, but this distinction is probably unnecessary. Whether we are dealing with two senses of one verb or a pair of homonyms is a moot question. Sarrazin, who set up an etymon with a long vowel, expressed some doubts about his reconstruction because bad has never been attested with a prefix, and Murray went to the trouble of discussing that article and respectfully (sic) rejecting its idea. Sarrazin’s bad developed from “oppressed” or, much better, from “defiled.”

It is true that bæddel was not pressed into service in connection with bad before Zupitza, but bædling, its synonym, almost its doublet, turned up in Diefenbach’s 1851 dictionary, and Koch, to whose article I promised to return, referred to it. Koch also cited Modern Engl. badling “a worthless person,” a North Country word, and Skeat, with his keen interest in dialects, could have come to nearly the same conclusion as Zupitza, had he noticed it. There is no certainty whether bædling had a short or a long vowel (compare the difficulties with bædan). Zupitza, a German, whose main area of study was English, must have been aware of the works by Diefenbach and Koch that neither Skeat nor Murray had read and only substituted bæddel for bædling, a word well-known to his predecessors. It is unnecessary to reconstruct bad from bæddel by strictly phonetic means, that is, by postulating the loss of l. The adjective could have been a back formation on either noun or led a long underground existence. Wait another week for a more definitive conclusion.

The OED’s etymology of bad found wide recognition (Skeat also accepted it), though Friedrich Kluge followed Koch (bad, “probably identical with Old Engl. abæded ‘forced, compelled’”), while Ferdinand Holthausen, an eminent scholar and the author of an etymological dictionary of Old English, preferred to derive bad from bædan (long æ) “to defile.” Another dissenter was Charles P. G. Scott, the etymologist for The Century Dictionary (CD). He followed Heinrich Leo and reconstructed Old Engl. bede ~ pede from the attested adjective orped “adult, active,” to which he ascribed the sense “hermaphrodite,” as in the OED. This etymology, itself an unnatural hybrid of two hypotheses, had no chance for survival, for how could “active” become “hermaphrodite”? Also, orped remains a word of unknown origin despite one ingenious conjecture about its derivation and is thus unfit to help us out.

How pregnant sometimes his replies are.

How pregnant sometimes his replies are.A. L. Mayhew in a fiercely aggressive and viciously unfair review of the first volume of the CD, called Scott’s hypothesis absurd, and here he was right. It disappeared from the second edition, in which bæddel is called the etymon of bad, but Scott added a pregnant remark: “…perhaps of nursery origin arising as a dissimilated form (*ba-da,*bad-da) of *ba-ba, modern dialectal babbah (German bäbä), used as an exclamation to warn infants not to touch or taste something thus indicated as ‘bad’… cf. na-na, ta-ta, tut-tut, as used similarly in warning or remonstrance” (the abbreviations have been expanded; asterisks mark unattested forms). Those who have read the post titled “Approaching the big bad word bad” will remember that I came to a similar conclusion by reasoning that that monosyllabic words beginning and ending with b, d, and g often have an expressive origin. However, I needed no reference to dissimilation. Nor will I need it in the future.

To be concluded.

Image credits: (1) “Bad” in Volume I of the 1933 edition of the OED. Photo by Alice Northover. (2) Ermafrodito, affresco Romano di Ercolano, 1–50 d.C., Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Johnston Forbes-Robertson as Hamlet, c. 1899. Photo by Lizzie Caswall Smith. Emory University. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The history of the word ‘bad’, Chapter 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

The lasting appeal of Great Expectations

According to George Orwell, the biggest problem with Dickens is that he simply doesn’t know when to stop. Every sentence seems to be on the point of curling into a joke; characters are forever spawning a host of eccentric offspring. “His imagination overwhelms everything”, Orwell sniffed, “like a kind of weed”. That is hardly an accusation that could be leveled against Great Expectations. If some of Dickens’s novels sprawl luxuriously across hundreds of pages, this one is as trim as a whippet. Touch any part of it and the whole structure quivers into life.

In Chapter 1, for example, Pip recalls watching Magwitch pick his way through the graveyard brambles, “as if he were eluding the hands of the dead people, stretching up cautiously out of their graves, to get a twist upon his ankle and pull him in”. Not until the final chapters do we realize why Pip is so haunted by the convict’s apparent reluctance to stay above ground, but already the novel’s key narrative method has been established. To open Great Expectations is to enter a world in which events are often caught only out of the corner of the narrator’s eye. It is a novel of hints and glimpses, of bodies disappearing behind corners, and leaving only their shadows behind. Whichever of Dickens’s two endings is chosen, it’s hard to finish the last page without thinking of how much remains to be said.

Of course, none of this occurred to me when I first read Great Expectations as a child. Growing up in the 1980s, this story of class mobility and get-rich-quick ambition resonated with all the force of a modern parable. The revelation that there was another story behind the one I was enjoying was as much a shock to me as it is to Pip, but that only increased my admiration for a novelist who treats his plot rather as Jaggers treats Miss Havisham in her wheelchair, using one hand to push her ahead while putting “the other in his trousers-pocket as if the pocket were full of secrets”. I suspect that’s one reason why Great Expectations is such a popular novel. Readers grow up with it. It’s probably also why so many of them sympathise with Pip, whose narrative voice involves the perspective of a wide-eyed child coming up against that of his wiser, sadder adult self. Anyone who first reads the story as a child and returns to it in later years is likely to feel a similar mixture of nostalgia and relief.

Antique camera by condesign. CCo Public domain via Pixabay.

Antique camera by condesign. CCo Public domain via Pixabay.

But it isn’t only individual readers who have grown up with Great Expectations, our culture has too. Dickens once claimed that David Copperfield was his ‘favourite child’, and that Great Expectations was a close second. It’s no coincidence that both novels are about how easily children can be warped or damaged, but of the two it is the shorter, sharper Great Expectations that has aged better. Few works of fiction have enjoyed such a lively creative aftermath. Peter Carey has rewritten it in Jack Maggs. Television shows from The Twilight Zone to South Park have echoed it in ways that range from loving homage to finger-poking parody. Even the title has come to settle in the public consciousness, with video dating agencies like ‘Great Expectations Services for Singles’ and shops like ‘Grape Expectations’ (wine) or ‘Baked Expectations’ (cakes). It’s hard not to be fond of a novel that so perfectly reflects its author’s restless, rummaging imagination.

But why would anyone want to read the novel today? Inevitably there are as many reasons as there are readers, and I hope that some lively discussions will emerge from OUP’s decision to choose Great Expectations as their big summer read. For some people, this is a novel about the fact that we never fully leave our childhood behind. For others, it is one of the most realistic love stories ever written, in which the many feelings associated with love – joy, hope, disappointment, regret, despair – mingle on the page without ever reaching a clear conclusion. For others still, this is a novel full of images that stick in the memory like burrs, from Pip crying in the graveyard to the ghastly appearance of Miss Havisham. Indeed, perhaps it is appropriate that this is one of the few novels written by Dickens that includes a plural noun in its title, because the longer you spend with this brilliantly compact work of fiction, the more you start to realise that it is in fact many novels in one.

Featured image: Leather shoes by Antranias. CCo Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The lasting appeal of Great Expectations appeared first on OUPblog.

Stop worrying about Cyber Pearl Harbor and start collecting data

A moderate and measured take on cyber security is a bit out of place among the recent flood of research and policy positions in the cyber security field. The general tone of the debate suggests that cyber war is here, it is our present, and will be our future. One gets millions of hits if ‘Cyber Pearl Harbor’ is Googled. The basic assumption is that our future military, diplomatic, and conflict history will involve the use of computers as the main avenue of attack and defense. Our perspective challenges this view and does so with the tools of social science, a necessary turn given the general tone of the debate.

In our research we were able to marshal a massive amount of evidence useful in dissecting the actual trends of the cyber battlefield. We demonstrate that while cyber-attacks are increasing in frequency, they are limited in severity, are directly connected to traditional territorial disagreements, and mostly take the shape of espionage campaigns rather than outright warfare. Given this evidence, we question the dynamics of the cyber security debate and offer a countering theory where states are restrained from using cyber actions due to the limited nature of the weapons, the possibility of blowback, the connection between the digital world and civilian infrastructure, and the reality that any cyber weapon launched can be used right back against the attacker. Given all these reasons and our data, we must be skeptical of the tone of the cyber security debate.

Cyber strategies and tactics are like any other technological development. At first it offers immense possibilities and promises to give states an edge, yet the reality is that technological advances rarely change the face of the battlefield, either diplomatic or military. New technologies can be used to defeat specific threats or defenses, such as the tank and the stalemate of the trenches in World War I, but are often limited in other contexts. Tanks need to be supported by infantry and logistical teams constantly supplying gas or towing the machines, limiting their effectiveness and reach. Cyber strategies will be no different; they will be just another piece in the arsenal but not game-changing on their own.

These sorts of claims of revolutionary importance are easy to make, and persuasive given certain examples, but there are always counter examples. For instance, nuclear weapons and the ending of World War II call into question the idea that technology does not change international interactions. Yet, the important point is that no one example or story tells the complete picture – for that we need evidence and data.

National Security Operations Center floor in 2012 by the National Security Agency. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

National Security Operations Center floor in 2012 by the National Security Agency. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.This is where our research can make an important and lasting statement. We examine all cyber actions between rival states to understand how this new technology is used by the most disputatious members of the international system. By looking at the complete picture, we get a different view of the evidence and data. No longer does one attack stand out, but the total picture emerges and it is a picture of a restrained international system developing a norm against the use of cyber weaponry.

Social science matters and it is important, and this book really owes an intellectual debt to J. David Singer, who started the effort to quantify war at the University of Michigan with the Correlates of War project. Our project builds on this methodology and uses many of the same coding strategies. We recognize that data is a work in progress and seek to build more and more knowledge through subsequent updates. By gathering the full picture, we can gain the perspective that really matters in these emerging policy debates.

The problem with collecting data where it does not exist already is the obvious trouble that comes with starting such an endeavor. Often it was claimed it would be impossible to collect cyber conflict data, that such data would present a skewed picture of the scope of the field. Yet the theoretical impossibility of collecting data should never be the barrier in starting such an undertaking, the only real barrier should be the literal impossibility of collecting such information. As we went along collecting data we found that official leaks to the media were helpful, but more importantly for the cyber security field was the obvious impetus by cyber security firms to demonstrate their ability to identify attacks and release reports forensically accounting for the process behind the attacks. This sort of information was exactly what we were looking for and it continues to be available to this day as the ultimate calling card to drum up business, to protect companies and states, but also as a source of information in our investigation.

Of course, data is always biased by the person collecting the data and interpreting the evidence. This is also a strength of data: others can come along and use it for their own ends. We are excited about the emerging work that takes our data to build different perspectives. The basic point is that we need to stop engaging important policy questions through prognostication that would be more suitable on a 2 a.m. television advertisement. Political scientists and policy makers should not be fortune tellers who make guesses about the future without reference to what we know now. We have evidence from the recent past and emerging contemporary situations, so let’s use it to engage critical policy questions. That is what we do with our research and I encourage others to not be daunted by the effort required to build a dataset; it is an important step needed for all critical policy questions.

The post Stop worrying about Cyber Pearl Harbor and start collecting data appeared first on OUPblog.

What are the ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ of international donation?

The Nepal earthquake. The conflict in Syria. Malaria. More than two billion people in or near “multi-dimensional” poverty (Human Development Report 2014). While the world is getting better in some respects, massive needs and injustices remain. Many of us want to do something to help. For individuals in rich countries who lack personal ties to individuals or organizations in poor or disaster-affected countries, “doing something” often means donating to an international non-governmental organization (INGO). But how should we (for I count myself in this group) choose which INGO(s) to fund? While this is a difficult question, and one for which I can’t offer a complete answer, my research on humanitarian INGOs suggests some tentative conclusions.

First, figure out why you are donating. Many of us feel we are donating because we want to “do good,” but this is rather vague. Is your aim to do as much good as possible? Are you trying to compensate for harms to which you have contributed, directly or indirectly? Do you want to honor a friend or family member by contributing to a cause they support? Are you in search of the “warm glow” feeling that comes from joining a collective effort to address a high-profile emotive issue, like the recent earthquake in Nepal? Answering this question is crucial, because pursuing these different aims often leads to supporting different organizations or causes. In particular, donations that honor friends and family or cultivate a “warm glow” feeling often do not do as much good as possible. The suggestions that follow are primarily for individuals who wish to do as much good as possible.

“Haitian Child Collects Water in Camp for Displaced” by United Nations Photo. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

“Haitian Child Collects Water in Camp for Displaced” by United Nations Photo. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.If that is your aim, a good first step is to identify and resist the psychological pull of morally irrelevant factors. For example, research on the “identifiable victim effect” supports what INGOs have known for decades: individuals in wealthy countries donate more in response to a close-up photograph of a single child’s face than they do in response to other kinds of text and images. In laboratory experiments, a photograph of two or more people and a photograph with accompanying statistical information raised less money than a photograph of an individual child with no background information. (This helps explain why “child sponsorship” programs raise so much money.) Yet while they tug at our heartstrings, these sorts of images convey virtually no helpful information. They can even be misleading, insofar as they imply that aid recipients are helpless victims. Donors who want to do as much good as possible should ignore these sorts of images.

There are other emotionally compelling features of INGOs or the situations they address that, upon scrutiny, appear morally irrelevant. One is the visual drama. For example, while the presence of large amounts of rubble is visually gripping, many kinds of very serious suffering and harm, such as early death from diarrhea or measles, lack a visually gripping element but are no less important—or addressable—for this fact. Furthermore, many INGOs seek to attract donors by pointing out that they work in a large number of countries. But while it is morally important that an INGO assists a wide range of individuals and does not make invidious distinctions, where those individuals happen to live does not seem to matter.

After excluding morally irrelevant factors, your next step is to identify factors that are morally relevant. One of these is where other people are donating. Some high-profile emergencies, such as the 2005 Indian Ocean tsunami, are “over-funded,” with more money available than organizations on the ground can use effectively. Donating more to these situations is unlikely to do much good. Another morally relevant consideration is cost-effectiveness: how much does an INGO accomplish with every dollar it spends? Cost-effectiveness can be difficult to measure, but it appears that some interventions are vastly more cost-effective than others, at least when outcomes are measured in “Quality-Adjusted Life Years” or QUALYs. For example, Toby Ord argues that providing anti-retroviral therapy to people with HIV/AIDS in developing countries generates 1-2 QUALYs/$1000, while educating prostitutes generates 26 QUALYs/$1000. By taking cost-effectiveness into account, you can avoid funding dramatic projects that tug at your heartstrings but in reality provide little benefit.

“Woman dairy farmer in Bangladesh” by IFPRI-IMAGES. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr

“Woman dairy farmer in Bangladesh” by IFPRI-IMAGES. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via FlickrCost-effectiveness is not the same as the amount of money an INGO spends on administrative costs. Some charity evaluation websites, such as Guidestar, suggest that the less money an INGO spends on administrative (versus program) costs, the more effective it is. But “administrative costs” typically include preliminary research to decide which projects to undertake in addition to after-the-fact program evaluations, both of which are important for ensuring that aid is cost-effective and has minimal negative effects. So while very high administrative costs are a red flag, INGOs with very low administrative costs are not necessarily better than those with moderate administrative costs.

While cost-effectiveness is important, a narrow focus on maximizing cost-effectiveness can, in practice, require ignoring numerous outcomes, processes, and relationships that many people value but are difficult to measure, such as social justice and empowerment of the poor and marginalized. For this reason, incorporating these values probably requires accepting less rigorous empirical evidence that a project is doing the most good.

To summarize—ask yourself why you are donating. If your aim is to do as much good as possible, don’t fall prey to the identifiable victim effect, visual drama, or other compelling but morally irrelevant aspects of INGOs or the situations they address. Do put significant weight on cost-effectiveness, but also incorporate other important values, such as social justice. On a more practical level, remember that larger INGOs often have more capacity than smaller INGOs to do rigorous research and project evaluation, and that INGOs that receive more of their funding from governments are often more constrained by those governments’ agendas than INGOs that are funded largely by individual contributions.

These are general suggestions for how individuals who want to do as much good as possible might proceed in deciding where to donate; they do not lead to the doorstep of one INGO. Insofar as taking the steps outlined above requires information that is not readily available, would-be donors have good reason to ask INGOs to provide it. Donors might also consider funding other types of actors, such as social justice organizations based in the global South.

Once would-be donors have decided which INGO(s) or other organization(s) to support, another question arises: What does it mean to be a responsible donor? Part II of this post will address this question.

Image Credit: “A child walks on top of a tent in a refugee camp” by FreedomHouse. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What are the ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ of international donation? appeared first on OUPblog.

Global warming and clean energy in Asia

The year 1896 was “a very good year” for many reasons. It was in that year that Puccini’s Opera, La Bohème, premiered, gold was discovered in the Yukon, and the Dow Jones Industrial Average finished its first year at around 41. But perhaps closer to our subject, two other events stand out. Firstly, Henry Ford introduced the gasoline-fueled automobile to America and, secondly, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius suggested that a greenhouse-like warming of the planet could result from increasing atmospheric CO2. Thus, the possibility that the industrial revolution would ultimately become incompatible with the physical environment was first envisioned.

Modern industry is foundational for contemporary society. Yet, its dependence upon fossil fuels, primarily, and upon other chemicals, secondarily, threatens to destroy that very same society. One should note, at the outset, that those industrial processes do not so much create greenhouse gases, as they are termed, but rather release them. In fact, the term “fossil fuels” originates in the idea that they – petroleum, coal, and natural gas – originate in the decayed remains of plants and animals that lived long ago. Although not universally accepted, this theory originates with the 18th century Russian chemist Mikhail Lomonosov, who first argued: “Rock oil originates as tiny bodies of animals buried in the sediments which, under the influence of increased temperature and pressure acting during an unimaginable long period of time, transform into rock oil.”

Thus, global warming threatens to restore our planet to an ancient equilibrium – an equilibrium that was home to tropical plants and dinosaurs, but not to man.

It is because of this integration with our economic system that the problem is so complex. And, in particular, because of the way our economic system incorporates so much of society, climate change issues are, indeed, issues for every man and woman on the planet.

As the chemist Nathan Lewis has said: “The currency of the world is not the dollar, it’s the joule” (Lewis, Nathan S. (2007), “Powering the Planet”, Engineering and Science). Thus, the value in modern industrial processes is that they harness energy, focusing the transformational power of machines into production. Unfortunately, although there are numerous sources of energy which are not accompanied by the emission of greenhouse gases – solar and wind – the technology of transmission and storage of energy is still in its infancy.

Image: “Mulan Wind Farm”, by Land Rover Our Planet. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

Image: “Mulan Wind Farm”, by Land Rover Our Planet. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.Fossil fuels are simply one of the most efficient forms of stored energy. They are also a convenient form in which to transport energy to the places where it is needed.

Fossil fuels are integrated not only into our economy, but into our society as well. The automobile, for example, is as much a cultural icon as it is a means of transportation. Thus, the economic consequences of energy production, use, storage, and transmission, as well as any attempts to control these processes, will reflect in the political arena, in daily life, on Wall Street, and on the global economy through a plethora of intricate, often interlocking, mechanisms.

Western society has developed itself, largely oblivious to concerns of climatic change. The benefits in terms of quality of life are manifest, and they have become, arguably, the West’s primary export to the rest of the world. The, so-called, under-developed world has bought-in to the program and now seeks to align itself, economically, if not culturally, with the West. Yet, just as this dream begins to appear real, the limitations imposed by global warming are becoming apparent.

Figure 1. Image Credit: “Annual GDP Growth Rate for China, India and U.S.”, used with permission from the authors. Data Source: The World Bank; National Bureau of Statistics of China; Central Statistics Office of India; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Figure 1. Image Credit: “Annual GDP Growth Rate for China, India and U.S.”, used with permission from the authors. Data Source: The World Bank; National Bureau of Statistics of China; Central Statistics Office of India; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.China, in particular, and Asia, in general, has stepped up to the plate, as it were. GDP growth rates in Asia have been in the high single digits for decades, double or triple that found in the US. In Figure 1, we can see that China and India, representing a significant portion of the world’s population, are growing rapidly.

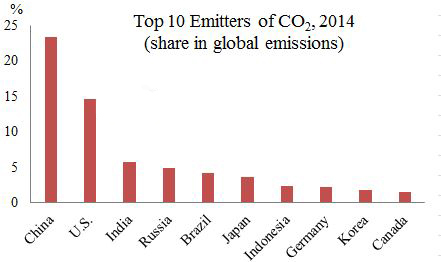

Yet, this growth has come with an environmental cost. As outlined earlier, the expenditure of energy, largely derived from fossil fuels, is matching Asia’s economic growth. Figure 2 shows individual country’s CO2 emmissions as a percentage of global CO2 emmissions.

Figure 2. Image Credit: “Top Ten Emitters of Co2, 2014″, used with permission from the authors. Data © Statista 2015.

Figure 2. Image Credit: “Top Ten Emitters of Co2, 2014″, used with permission from the authors. Data © Statista 2015.Obviously, the West cannot simply say “slow down” to Asia. This is a non-starter. Yet, one cannot escape the facts. Global warming will, ultimately, through its devastating effects on global systems, destroy the very economic engine that fuels Asian (and Western) development.

The challenge of Asia is to figure out how to maintain its development, while addressing the issues surrounding greenhouse emissions.

This may not be as farfetched as it sounds. Most of Western development took place in a crude industrial environment. The internal combustion engine, for example, is largely a nineteenth century technology, although it was conceived of earlier.

Yet, from modern computers to advanced materials, Asia today has the advantage of a century of innovation and technological progress. It need not wade through the swamp of carbureted engines and untreated exhausts that the West passed through. Nowadays, computer-controlled fuel injection is available and catalytic converters reduce noxious emissions. But there are also advances in solar panels and wind generation, computer control of electrical networks, etc. New “green” technologies are not only beneficial to the environment; they are also an important economic engine in and of themselves, providing entrepreneurial opportunity and jobs to those nations which adopt them.

Asia is well-aware of this. China has been a “high speed” investor in clean energy since 2004. In fact, according to recent data from The Bloomberg New Energy Finance Report, China leads the world in renewable energy investment, spending a total of $89.5 billion on wind, solar, and other renewable projects in 2014 alone. Thus, rather than trying to contain Asian growth, sound market principles suggest that exactly the opposite strategy may encompass the best hope of finding a solution to the problem of global warming.

Featured image: “#431 Global warming get warmer houses”, by Mikael Miettinen. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Global warming and clean energy in Asia appeared first on OUPblog.

July 7, 2015

All life is worth saving

Just as in Clarence Darrow’s day, the death penalty continues to be practiced in many American states. Yet around the world, the majority of nations no longer executes their prisoners, showing increasing support for the abolition of capital punishment. Recently, in December 2014, when the United Nations General Assembly introduced a resolution calling for an international moratorium on the use of the death penalty, a record 117 countries voted in favor of abolition, while only 38 nations, including the United States, voted against it. Indeed, falling just behind China, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, the United States is recorded to have the fifth highest rate of execution worldwide.

Since Jamestown settlers first executed Captain George Kendall in 1607, jurisdictions across the United States have approved the execution of approximately 16,000 people by various methods, including hanging, firing squads, gas chambers, electric chairs, and lethal injection. As these executions continued throughout American history, many prominent abolitionists have raised their voices against capital punishment, both in the past and the present. Dr. Benjamin Rush, an eminent physician, author, and civic leader who signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776, was an early advocate for abolishing the death penalty, while many of the country’s founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, favored limitations on the practice. Most recently, during the twentieth century, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, and author Sister Helen Prejean all emerged as outspoken opponents of capital punishment.

Over the course of 400 years, the popularity of the death penalty has fluctuated, with some states abandoning their use of capital punishment earlier than others. In the mid-1800s, death penalty abolitionists achieved some success, thanks largely to societal changes that included prison reform movements, religious revivals, an influx of new immigrants, and the rise of the anti-slavery movement. People interested in these issues, however disparate, found in each other a common purpose, arguing that the use of capital punishment reflected how those in power treated the poor and powerless.

Falling just behind China, Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia, the United States is recorded to have the fifth highest rate of execution worldwide.

In 1847, Michigan became the first state to abolish capital punishment in the United States. Like some other states, Michigan had gradually been limiting its use of the death penalty in the preceding decades, and by the 1840s, its legislature featured many reform-minded lawmakers. Rhode Island subsequently abolished the death penalty in 1852 and Wisconsin followed suit in 1853, prohibiting capital punishment for all crimes.

Throughout different abolition periods, such as the early 1900s and the mid-twentieth century, opponents of capital punishment have raised a variety of arguments against the practice. Many question whether the death penalty serves any valid purpose, suggesting it does no more to deter crime than the threat of imprisonment. Others reason that the death penalty is inhumane and therefore inconsistent with religious principles. Most importantly, many abolitionists have highlighted the obvious fallibility of a system based on human juries and judges. Indeed, this argument has gained clout in modern times, as scientific breakthroughs in DNA testing and investigative techniques have led to the discovery of innocent people on death row. The question of race–whether the death penalty can be applied fairly and without racial bias–has also emerged alongside concerns that capital punishment targets society’s most disadvantaged.

An important turning point arrived in the 1960s and 1970s, when the Supreme Court of the United States began to address the practice as a constitutional issue. In Furman v. Georgia (1972), Supreme Court Justices found that existing procedures for the death penalty violated the United States Constitution because of the broad discretion afforded to jurors, who were capable of arbitrary and racially discriminatory decisions.

Given the worldwide trend of countries prohibiting capital punishment, many observers predicted the case would end the death penalty in the United States. However, as part of a backlash against the Supreme Court, several state legislatures renewed their death penalty laws; and in 1976, the Supreme Court upheld some of these new procedures, reintroducing capital punishment as common practice and starting a new era for the practice.

Over the following decade, the Supreme Court evaluated another broad attack on capital punishment in McCleskey v. Kemp, in which Warren McCleskey’s attorneys presented statistical evidence illustrating the racial bias of the justice system. The Supreme Court, rejecting this claim, thereby affirmed that any changes to death penalty laws would have to established through political processes.

Image: “Group of people holding signs at a death penalty protest” by OBS onthemove. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image: “Group of people holding signs at a death penalty protest” by OBS onthemove. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Ever since the United States resumed executions after 1976, nationwide jurisdictions have sent approximately 1,400 people to their deaths. In the modern era, 1999 was notable for the highest number of executions, with 98 death row inmates executed that year. While this number dropped to 39 in 2013, more than 3,000 people remain on death row across the country.

Recently, however, activists have found some success in illuminating the drawbacks of the death penalty through educational efforts. During the past decade, seven states have repealed the practice of sentencing prisoners to death, including Illinois, the same state in which Clarence Darrow infamously defended murderers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb.

Presently, the federal government, along with 31 states, has upheld the use of capital punishment, whereas only 19 states (and the District of Columbia) have prohibited it. A Gallup poll in winter 2013 showed that the death penalty continues to be popular among American citizens—at least in theory—with up to 60 percent indicating their support for capital punishment in the case of convicted murderers. For some, the death penalty continues to serve as a fitting punishment and just retribution for society; for others, it continues to be justified by religion. Other advocates even assert that the death penalty may deter crime. Still, when asked to make a choice between capital punishment and life imprisonment without parole, support for capital punishment is shown to drop, as citizens are split equally between the two options.

In the past year alone, the debate surrounding the death penalty has been inflamed by botched executions, notably in the Arizona execution of Joseph Wood, who took two hours to die from lethal injection. There are also increasing concerns about the expense of the modern death penalty for taxpayers. In Texas, for example, the cost of a death penalty case today is thought to be nearly three times more expensive than imprisoning someone in maximum security for 40 years.

Charged and complex, the public debate surrounding the death penalty has once again been brought to the fore, even spilling over into international territory as European manufacturers discontinue their supply of lethal drugs to the United States. Because the death penalty in America is largely a state issue, the success of abolition efforts will most likely be gradual. However, the recent global trend against capital punishment has been encouraging to those who, like Clarence Darrow, believe that both logic and humanity demand an end to the practice of killing prisoners.

A previous version of this article appeared in the Old Vic program for the play Clarence Darrow (starring Kevin Spacey).

Featured Image: “Red Hats Execution Chamber” by Lee Honeycutt. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post All life is worth saving appeared first on OUPblog.

Happy 120th birthday BBC Proms

In celebration of The BBC Proms 120th anniversary we have created a comprehensive reading list of books, journals, and online resources that celebrates the eight- week British summer season of orchestral music, live performances, and late-night music and poetry.

William Walton Edition Complete Set Composer: William Walton & General Editor: David Lloyd-Jones.

A collected edition of the works of one of England’s finest and best-loved composers. A definitive and fully practical edition, based on the form in which the composer ultimately wished his music to be performed, and including in some cases both original and revised versions.

Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast will feature at the First Night of the Proms on 17th July.

Hear, Listen, Play! by Lucy Green.

Based on over 15 years’ original and world-renowned research by the author and her research teams, the book discusses how popular musicians learn in the informal realm, and then applies many aspects of their learning practices to three main areas within music education.

Read Brett Clement’s article A New Lydian Theory for Frank Zappa’s Modal Music from the Music Theory Spectrum journal.

Find out how children in schools across the UK have been working on their own responses to music by Beethoven and others at the Ten Piece Prom on 18th July.

Out of Time by Julian Johnson

If all music since 1600 is modern music, the similarities between Monteverdi and Schoenberg, Bach and Stravinsky, or Beethoven and Boulez, become far more significant than their obvious differences. Johnson elaborates this idea in relation to three related areas of experience – temporality, history and memory; space, place and technology; language, the body, and sound. Read the free introduction from Out of Time, available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

If all music since 1600 is modern music, the similarities between Monteverdi and Schoenberg, Bach and Stravinsky, or Beethoven and Boulez, become far more significant than their obvious differences. Johnson elaborates this idea in relation to three related areas of experience – temporality, history and memory; space, place and technology; language, the body, and sound. Read the free introduction from Out of Time, available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

Karen Leeder will be giving a talk on the poetry that inspired Beethoven at Proms Extra on the 24th July.

Bollywood Sounds by Jayson Beaster-Jones.

The first monograph to provide a long-term historical insight into Hindi film songs, and their musical and cinematic conventions, in ways that will appeal both to scholars and newcomers to Indian cinema. Read chapter one from Bollywood Sounds, available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

In celebration of 50 years of Asian programmes on the BBC, music from Bollywood will be featured at Prom 8 on 22nd July.

Anything Goes by Ethan Mordden

From “ballad opera” to burlesque, from Fiddler on the Roof to Rent, the history and lore of the musical unfolds here in a performance worthy of a standing ovation. Chapter one from Anything Goes is available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

From “ballad opera” to burlesque, from Fiddler on the Roof to Rent, the history and lore of the musical unfolds here in a performance worthy of a standing ovation. Chapter one from Anything Goes is available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

Read Paul Wittke’s article The American Musical Theater (with an Aside on Popular Music) and David Brodbeck’s article A Tale of Two Brothers: Behind the Scenes of Goldmark’s First Opera, both from The Musical Quarterly journal.

Prom 11: Fiddler on the Roof will be performed on the 25th July.

Ezra Pound: Poet by A. David Moody

This second volume of A. David Moody’s full-scale portrait, covering Ezra Pound’s middle years, weaves together the illuminating story of his life, his achievement as a poet and a composer, and his one-man crusade for economic justice.

Read the poem The Shyness of Beauty by Laurence Binyon, a contemporary of Pound, from the Music & Letters journal.

Poets Jo Shapcott and Sean O’Brien discuss Pound’s poetry at Proms Extra on 29th July.

Arranging Gershwin by Ryan Banagale

Ryan Banagale approaches George Gershwin’s iconic piece Rhapsody in Blue, not as a composition but as an arrangement — a status it has in many ways held since its inception in 1924, yet one unconsidered until now. Read chapter one from Arranging Gershwin available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

Ryan Banagale approaches George Gershwin’s iconic piece Rhapsody in Blue, not as a composition but as an arrangement — a status it has in many ways held since its inception in 1924, yet one unconsidered until now. Read chapter one from Arranging Gershwin available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

Hear Rhapsody in Blue at Prom 32 on 9th August.

Nilsson by Alyn Shipton

In this first ever full-length biography, Alyn Shipton traces Nilsson’s life from his Brooklyn childhood to his Los Angeles adolescence and his gradual emergence as a uniquely talented singer-songwriter. With interviews from friends, family, and associates, and material drawn from an unfinished autobiography, Shipton probes beneath the enigma to discover the real Harry Nilsson.

Alyn Shipton will be discussing swing and its influences at BBC Proms Extra on 11th August.

Some of These Days by James Donald

This book extends beyond pure dual biography to recreate the rich community of actors, architects, poets, directors, and musicians who interacted with—and were influenced by—each other.

Read Mark Burford’s article Mahalia Jackson Meets the Wise Men: Defining Jazz at the Music Inn from The Musical Quarterly journal, and find out more about the Jazz tradition and its roots on Oxford Bibliographies online.

The BBC will be showcasing current UK jazz talent at Prom 35 on 11th August.

Conan Doyle by Douglas Kerr

From the early stories, to the great popular triumphs of the Sherlock Holmes tales and the Professor Challenger adventures, the ambitious historical fiction, the campaigns against injustice, and the Spiritualist writings of his later years, Conan Doyle produced a wealth of narratives. He had a worldwide reputation and was one of the most popular authors of the age. Read the free introduction from Conan Doyle, available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

From the early stories, to the great popular triumphs of the Sherlock Holmes tales and the Professor Challenger adventures, the ambitious historical fiction, the campaigns against injustice, and the Spiritualist writings of his later years, Conan Doyle produced a wealth of narratives. He had a worldwide reputation and was one of the most popular authors of the age. Read the free introduction from Conan Doyle, available exclusively on Oxford Scholarship Online.

The BBC will pay homage to the world of Sherlock Holmes at Prom 41 on 16th August.

The Oxford Handbook of Sondheim Studies edited by Robert Gordon

This collection of never-before published essays addresses issues of artistic method and musico-dramaturgical form, while at the same time offering close readings of individual shows from a variety of analytical perspectives. Read a free chapter from the Handbook, ‘Sondheim’s Genius’, available exclusively on Oxford Handbooks Online.

Sondheim’s renowned works will be performed at Proms Chamber Music 5 on 17th August.

The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume I: 1695-1717 by Richard D. P. Jones

The first volume of a two-volume study of the music of J. S. Bach, covers the earlier part of his composing career, 1695-1717. By studying the music chronologically, a coherent picture of the composer’s creative development emerges, drawing together all the strands of the individual repertoires (e.g. the cantatas, the organ music, keyboard music).

Find out why Johann Sebastian Bach is regarded as one of the greatest composers in the history of European art music on Oxford Bibliographies online, and read David Schulenberg’s article Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach: a tercentenary assessment from the Early Music journal.

The BBC Singers and the Academy of Ancient Music will celebrate Bach at Prom 48 on the 21st August.

Music from OUP featured at the Proms

Belshazzar’s Feast edited by Steuart Bedford

Belshazzar’s Feast has been featured in an amazing 32 Proms. The earliest proms performance of this work was in September 1946, fifteen years after its world premiere at the Leeds Festival in October 1931. The first proms performance was conducted by Adrian Boult, who also conducted the first London performance of Belshazzar’s Feast with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in November 1931.

Symphony No. 2 edited by David Russell Hulme

Walton Symphony No 2 has been featured in 4 Proms. The earliest proms performance was in August 1961, just a year after its composition. This proms premiere was conducted by Malcolm Sargent, who was the chief conductor of the proms at the time.

Prelude and Fugue: The Spitfire edited by David Lloyd-Jones and Concerto for Violin composed by Ralph Vaughan Williams

The first ever proms performance for both Walton’s Prelude and Fugue: The Spitfire and Vaughan Williams’ Concerto for Violin (also known as Concerto Accademico).

Find out more about Orchestral Music from Oxford Bibliographies online.

Do you have any Proms reading materials that you think should be added to this reading list? Let us know in the comments below.

Featured image credit: BBC Prom by Paul Hudson. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Happy 120th birthday BBC Proms appeared first on OUPblog.

A tiny instrument with a tremendous history: the piccolo

Although often overlooked, the piccolo is an important part of the woodwind instrument family. This high-pitched petite woodwind packs a huge punch. Historically, the piccolo had no keys, but over the years, it has transformed into an instrument similar in fingering and form to the flute. It still serves as a unique asset to the woodwinds.

The piccolo is about half the size of the flute.

Other than size, the biggest difference between the two instruments is that the piccolo is pitched one octave higher.

Unlike the flute, piccolos can be made out of plastic, wood, or metal.

The piccolo was often referred to as the “petite flute” or “flautino” – but so were flageolet or small recorders, sometimes making it difficult to determine what instrument that composer had in mind.

In Italian, ‘piccolo’ is used as an adjective to describe various instruments that are the smallest and highest in pitch of their type. These include the violin piccolo, piccolo clarinet, and piccolo timpani.

Man in uniform playing piccolo. Photo by Bengt Nyman. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Man in uniform playing piccolo. Photo by Bengt Nyman. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Some of the most famous piccolo parts can be found in Beethoven’s Egmont ov and in John Phillip Sousa’s march The Stars and Stripes Forever.

The piccolo was originally designed for military bands to make the flute parts more prominent.

Piccolos were once available in the key of D♭ but are currently only sold in the key of C.

The piccolo can often be confused with the fife, which is similar in form but creates a louder, shriller sound.

The piccolo is the most highly pitched instrument of all the woodwinds.

Featured Image: Philharmonic Orchestra of Jalisco by Pedro Sánchez. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A tiny instrument with a tremendous history: the piccolo appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers