Oxford University Press's Blog, page 644

July 11, 2015

The status of older people in modern times

The nineteenth century witnessed radical changes in the social and economic landscape, especially in Western Europe and North America. Social scientists observed that industrialized countries were becoming wealthier; more powerful and politically more stable. Yet, the changes that accompanied modernization were not altogether positive. There were also dramatic social changes such as the breakdown of the traditional extended family into nuclear families. Social gerontologists, who study the social aspects of aging, started wondering how these changes affect the role of older people in society. Do they lose their social status — their standing or importance in relation to other people within a society? Does modernization decrease the social status of older people at a steady rate? Or is there a more complex relationship? Are there other societal factors that, together with modernization, influence the social status of older people?

Donald Cowgill and Lowell Holmes addressed some of these questions in their Modernization Theory published in the 1970s. They thought that the more modern a society becomes, the more the status of older people declines because of four main reasons:

First, modern health technology (e.g., sanitation, immunization) accounts for higher life expectancies and consequently increases the proportion of older people in the population, which ultimately leads to competition over resources. Policy makers introduced retirement in order to ease competition in the labour market. Since labour market participation in modern societies is tied to income, prestige and honour, retirement stripped this away from older people, undermining their status.

Second, a modern economy means that new professions develop which require special training. This usually results in better paid and more prestigious jobs, therefore raising the status of younger people compared to older ones.

Third, urbanization develops because employment opportunities in modern societies exist mostly in cities making young people leave rural areas. The nuclear family becomes more important at the expense of the extended family. Instead of being supported by their families, older people start receiving institutionalized support.

Fourth, in pre-modern societies most of the population is illiterate. Knowledge is passed on verbally and older people play a crucial role as living repositories of knowledge. In modern societies, however, younger people are usually better educated than their parents and much of the traditional knowledge and skills of older people becomes obsolete.

Modernization Theory became a core theory in social gerontology and continues to be widely referenced, probably because of its intuitive appeal. Yet, very few studies scrutinized it. One exception is Erdman Palmore and Kenneth Manton´s analysis of 31 countries which led to a refinement of the theory. They found that older people’s objective status (education and occupation) does indeed decline in the early stages of modernization; however, it increases in more advanced stages of modernization resembling a J-shaped association. This might be because the funds allocated to support older people (e.g., in the form of retirement benefits) also increase, allowing older people to maintain their status.

One of the major criticisms of Modernization Theory points to the vagueness of its key concepts. In fact, “modernization” has been used interchangeably with terms such as “development” and “industrialization”. It is also not clear what exactly is meant by the concept “status” and whether it refers only to the objective status or also to the subjective social status (how people perceive older adult´s position in society).

In a recent study, my colleagues and I tackled some of these criticisms by analysing representative data from the European Social Survey (ESS) with responses from 45,706 individuals and 25 countries. We focused on the subjective social status of older people because it has important implications for older people’s well-being. We operationalized “modernization” according to Cowgill´s theory and used an index composed of national life expectancy, Gross Domestic Income, levels of education, and urbanization. Since all countries in the European region are in relatively advanced stages of modernization, we expected to find a positive linear association between modernization and social status. We also predicted that employment rates of older people matter for how they are perceived. Individuals and social groups who are not employed are usually stigmatized since they are perceived to be dependent on state welfare and as not contributing to society. Hence, older people who are in retirement may be seen as a threat to the economic resources of the country. This should be especially the case in countries with a weaker economy.

As predicted, our results show that the societal context matters in understanding why the status of older people is perceived to be lower in some countries than in others. In general, we found that the more modern a country and the higher the employment rate of older people, the more positively older people are perceived. However, these two factors also interact with each other. The perception of older people’s status is boosted in not so modern societies if there is a relatively high employment rate of older people indicating that their active contribution to the economy is credited with more positive representations. Hence, a psychological variable like perceptions of older people´s social status is related in important ways to socio-economic aspects of a country. Our findings suggest that raising the employment rate of older people in weaker economies – even if it is just partial employment – could raise both older people´s personal living standards and the way they are perceived by others, which should also have positive effects on their well-being.

Image Credit: Aderna. CC0 via Pixabay

The post The status of older people in modern times appeared first on OUPblog.

Music and metaphysics: HowTheLightGetsIn 2015

HowTheLightGetsIn (named, aptly, in honour of a Leonard Cohen song) has taken the festival world by storm with its yearly celebration of philosophy and music. We spoke to founder and festival organiser Hilary Lawson, who is a full-time philosopher, Director of the Institute of Art and Ideas, and someone with lots to say about keepings things equal and organising a great party.

Hi Hilary, how did the festival first get started?

So, the HowTheLightGetsIn (HTLGI) festival has been running for 6 years now. I’d like to say that there was some grand idea behind it but I’m afraid there wasn’t. As a philosopher I’d had experience of how the academy works and I was aware that culturally speaking philosophy was a joke, more associated with the ‘Monty Python philosopher’s football match’ than serious scholarship. The reason that the academy had walled itself in such a way was that it seemed to be engaged exclusively in a technical conversation about the meaning of words which had no real bearing on people. It had become impenetrable; people couldn’t understand what philosophers were saying. Growing up with philosophy and being a philosopher myself I’d seen this from the inside.

I had an experience twenty years ago where I was at a conference with the American philosopher Richard Rorty who at that time one of the leading philosophers in the world. We were standing at the back of a session, listening to the speaker and I turned to Richard and said “I didn’t understand anything of that”. He turned to me and said, straight away, “yes I didn’t understand any of it either – I very rarely do”. Meanwhile apparently erudite questions were being asked from the floor. There probably wasn’t anyone there who understood what the speaker has said but they were apparently asking these good questions. Afterward Rorty admitted to me: “you know, I’ve been going to these conferences for about 30 years and I hardly ever understand them!” It was like we both knew this but had never called it. I think from that point I thought I’m not going to play this game.

Why did you choose the festival format?

So what we try to do here is provide a framework for serious interaction. There is no attempt to dumb anything down, the philosophers are just there to make their case and try to convince the other people and the panel. If you have two people who are disagreeing about quantum physics you learn more than a solo speaker. Gradually over the years I think it’s beginning to work, people go away and feel genuinely exhilarated. This rarely happens in academic circles because people are constantly worrying about how clever they look or their status but there is really no need.

We are fervently against celebrity culture so we don’t choose people because they are well known. We choose the ideas and the topics first and then we choose people who have a strong and original view. We are therefore trying to cage a creative atmosphere.

HTLGI combines art, philosophy, and music. Why mix the three?

On the one level it’s because it’s fun and it’s nice to have a party. But I think there is another element here which is about fighting the status game. When you have a panel of people, if you’re not careful, the people on the panel become the “gods” as it were and that’s not conducive to conversation. When music drifts in from next door’s tent it is not an intrusion, I think it just softens everybody, people are less status conscious. So music helps to create that atmosphere.

This year the theme of HTLGI was “fantasy and reality”. Does this reflect the dual nature of the festival?

We are driven by our theme and we have a different one each year so of course each one breaks out differently. But we do use our theme to help unite the different elements of the festival. The different people who are on our teams such as arts or philosophy are looking to see what’s coming up in each area and having a theme helps us have an attack plan as to how we divide things up.

We also try to be on the zeitgeist. You’re right that the “fantasy and reality” theme fits with my personal thoughts on the philosophy front but it’s also right for now. We are always looking to stay relevant and so we don’t yet know what our theme will be next year.

It has been said that HTLGI poses an alternative to the increasingly corporate literary festival model. Was this intentional?

I mean we’re different. There are people who want to go along and see their celebrity author and we’re not in that space. You don’t come here to get an autograph; you come here to be involved in a conversation.

There are no solo speakers invited to the festival unless they are also willing to take part in a debate. It’s not just about pushing books it’s about opening ideas up to challenge. There is of course space for the more traditional approach that but it’s a different space. Some people will prefer it, some people will prefer us.

Do you hope to make philosophy accessible to a wider audience? There’s a huge range of people here, from all different age groups, professions, and backgrounds.

You’re right we do have a large age range here, which is remarkable. A lot of literary festivals have an age limit like 50-70 but as you can see here we have a lot of young people and a lot of older people.

I think that if you had a really broad brush, once upon a time us philosophers thought that we could explain the truth of the world and since then there has been slow, gradual withdraw from that. Although very few people describe themselves as post-modernist we are in a post-modernist world and many people as a result are very lost. So we are trying to stand in that space, and lots of people from lots of different places are keen to get involved.

In your introduction to the conference programme you make the statement that published ideas are “dead” as they can’t evolve any further. Do you therefore think that we should get rid of books with everything in discussion or should we just do lots more new editions?

No, not at all, and we shouldn’t get rid of books or formal education. But we should not pretend to seek the “objective truth” but make a more honest space as it mean there’s no need to hide subjective opinions. It’s more about your take on ideas not, for example, what the string theory is as we can look that up on Wikipedia. So we’re not anti-books at all, we just don’t want play the status game.

Featured image credit: How The Light Gets In 2015, banner. Image courtesy of Hilary Lawson.

The post Music and metaphysics: HowTheLightGetsIn 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

July 10, 2015

Uniqueness lost

A few months ago, we asked you to tell us about the work you’re doing. Many of you responded, so for the last few months, we’ve been publishing reflections, stories, and difficulties faced by fellow oral historians. This week, we bring you another post in this series, focusing on the difficult question of what to do with powerful stories that fall outside of an oral history project’s mission. We encourage you to engage with these posts by leaving comments, reaching out directly to the authors, or chiming in on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, and Google Plus . If you’d like to submit your own work, check out the guidelines. Enjoy! – Andrew Shaffer, Oral History Review

“When I went to the Iv’ry Coast, about thirty years ago, I remember coming off the plane and just being assaulted with not only the heat but the color.” These were the first words of the most moving story I have ever heard—but it wasn’t the story I was there to collect. For me, the best oral histories are the ones that sound a human chord, stories that blur the spaces between historically significant narrative and personal development. It’s hard to explain unless you’ve been there. You become involved, attached, and sometimes, devastated. Why? Because every once in a while, a story is outside of the scope of historical inquiry. It can’t be included in whatever project you’re working on, and may never see the light of day. This was the unknown fate of Sandi Howell’s particularly moving story, who I was interviewing for By The Work Of Her Hands, a State Department-funded exhibit that was fostering cross-cultural exchange between Moroccan embroiderers and African American quilters. Sandi was very open about what she calls ‘her uniqueness.’ Little did we know how unique our interview would be.

I was aware of African fabric before, but never had I seen it [makes whooshing noise] like that. I find that if African Americans and Latinos have a different sensibility where colors are concerned, as opposed to European. Everything went together. It was just chaotic, but it was gorgeous, and it was comfortable. It felt right.

Sandi and I sat down in a noisy diner across from her apartment, and her many bracelets jangled, just as loud as the fabric she was describing. I was there to discuss the craft of her quilting, but when her trip to the Ivory Coast came up, a new thread began to emerge.

It was very emotional because even having people from Africa [in the United States], it’s nothing like bein’ there live. It’s also a matter of things you’ve been told all your life or that you’ve heard. ‘Black is not beautiful, black is this, black is that.’ Even being proud of who I was, I never had to go through the black power thing. I’m a kid of the ’60s. We always knew who we were. But now you’re getting it reinforced in this light. To go to the country and see these people. All of a sudden, the connection to the Middle Passage made sense. It was very, very, very emotional.

What do we lose when we call powerful stories irrelevant?

What was even more traumatic was to see faces that looked familiar to me that I knew were not. I had one day [where] I stayed in tears for almost twenty-four hours. Because we were goin’ to the villages. We were talking to the elders. It went from English to French to whatever the language, but it always had to be that three-way translation. There was a group of us that was African American. One day, the chief of the village wanted to know from the interpreter, ‘Why would these black people dress like the white people?’ Oh boy.

An intensity descended upon the table, settling amidst our steaming lunch. A certain awe, a holiness, crept into Sandi’s voice. Everyone has experienced being stopped dead by the workings of the world—but it is rare to discuss these experiences with a stranger. Realizing we were about to embark, Sandi took a breath and continued:

They were tryin’ to get the concept. We were all lookin’ at each other, tryin’ to get the concept, to understand, ‘Don’t they know about slavery?’ No, they didn’t. They said, in terms for them, they thought that the ancestors had gone away to learn a new technology. Oh boy.

Now came the explanation about slavery, and they were aghast. Here comes that explanation of what happened. All of a sudden we were getting hugs. We were welcomed home. I was gone again. I stayed in tears.

Sandi and I were also in tears, abuzz in the intensity of our sharing space. I let out a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding, and laughed tentatively. Sandi laughed too, “Don’t tell me anything. It was wonderful.” We slowly gathered ourselves and continued talking for two hours, in a way much smoother than before, almost as if we’d left being strangers behind.

When I got home and reviewed the tape, I realized I couldn’t use it in the exhibition. Her story—so vibrant and heart-wrenching—did not comment upon her quilting craft. I was devastated. A part of me felt certain that its exclusion meant an essence of ‘uniqueness’ was lost, and that this was also true on a larger scale. Didn’t Sandi’s story provide something vital, not just to any narrative understanding of her character, but also to our understanding of the world? Did our project gain value through editing for historical relevance, even when so much was clearly lost?

I am engaged by oral history because of the way it demonstrates the dramatic phenomenon of the human experience within academia, art, and politics. But where our lives involve this spectrum of disciplines without discrimination, these disciplines heavily categorize, thus losing the universal quality of the human voice. Editing for content is a vital process all oral historians experience, but it calls into question the way we dissect our society and history. What do we lose when we call powerful stories irrelevant?

Image Credit: Photo taken by Eliza Lambert as part of By The Work Of Her Hands, a State Department-funded exhibit fostering cross-cultural exchange between Moroccan embroiderers and African American quilters. Used with permission.

The post Uniqueness lost appeared first on OUPblog.

Stathis Kalyvas imagines Alexis Tsipras’ speech to Greece

How does a leader address a country on the brink of economic collapse? In the wake of Greece’s historic referendum, many people around the world have engaged in fierce debate, expressing very different perspectives over its highly controversial outcome. Earlier today on Twitter, Stathis Kalyvas, leading expert and author of Modern Greece: What Everyone Needs to Know, swiftly responded to the political chorus, making a courageous foray into the world of social media. Here, he imagines his version of what Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’ speech would have been using the hashtag #fauxTsipras.

[View the story “Stathis Kalyvas: imagining Alexis Tsipras’ speech to Greece” on Storify]

Image Credit: “Greek flag” by Trine Juel. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Stathis Kalyvas imagines Alexis Tsipras’ speech to Greece appeared first on OUPblog.

Overcoming the “angel” perception of nursing

Most of us have vaguely positive sentiments about nurses, but at the same time, nursing is plagued by feminine stereotypes that continue to undermine the profession. These double-edged views are never more striking than in efforts to honor nurses, which often rely on emotional “angel” images rather than recognition of nurses’ health skills or tangible contributions to patient outcomes.

Perhaps the most prominent examples appear in the celebrations of nurses that occur in May each year for International Nurses Day, which caps an entire Nurses Week in the United States. Web searches about these events performed earlier this month revealed a few images that hinted at nurses’ expertise and advocacy, like one saluting them for stopping physicians from accidentally killing patients. A few images referred to the unusual challenges of nursing, such as the odd hours and miscellaneous bodily fluids.

But most of the search results instead showed hearts, flowers, and cuddly animals, along with text about a nurse’s gentle touch, caring, dedication, and kindness—in short, the angel. That enduring image defines nurses by their moral virtue, rather than by their health knowledge, life-saving skills, or courageous advocacy. Likewise, a survey of available Nurses Day gifts revealed an emphasis on angels, teddy bears, and hearts. Indeed, one handy feature of this decade seems to be that the “0” in years like “2015” is easily converted into a heart.

Many nurses and their supporters embrace this kind of imagery. In a typical formulation, Johnson & Johnson’s Discover Nursing website urged us to salute nurses during Nurses Week for their “dedication,” “commitment,” and “compassion.” Hospitals often honor their nurses in similar ways. During Nurses Week this year, the University of Texas Medical Branch issued its “Silent Angel Awards.” And what does “angel” mean to that major academic health center?

A: Always thinking of others

N: Numerous acts of kindness

G: Going above and beyond

E: Endless devotion

L: Loved

Meanwhile, a global nursing shortage continues to take millions of lives. Most nations don’t have enough nurses. But even in nations without a severe shortage of nurses, governments and other decision-makers are not funding enough nursing positions to protect the public. To cut costs, many nurses have been replaced by less skilled technicians or assistants. On the whole, the overwhelmingly female nursing profession remains underpowered. As a result, patients die, preventable diseases like Ebola spread, and nurses burn out—making the shortage worse. This public health crisis flows from society’s failure to understand how nurses with sufficient resources improve outcomes, in ways ranging from skilled monitoring to patient education.

The angel stereotype: Lifting hearts, but not saving lives. “Checking in with a Patient” by MyFuture.com. CC BY-ND 2.0 myfuturedotcom Flickr.

The angel stereotype: Lifting hearts, but not saving lives. “Checking in with a Patient” by MyFuture.com. CC BY-ND 2.0 myfuturedotcom Flickr.But you don’t need clinical and educational resources if you are a pillow-fluffing “angel” or a devoted “backbone” of health care. You certainly don’t cause trouble by questioning dangerous practices. On the contrary, you quietly embrace challenges like working intensely for 13 hours without a break for food or the restroom, earning a low salary despite needing to support your family, or taking abuse from patients, physicians, and other colleagues. It’s just what angels do!

Nursing groups sometimes do better in paying tribute to the profession. This year, the International Council of Nurses’ theme for Nurses Day focused on nurses as a cost-effective force for change in health care financing structures. But many national nursing organizations had 2015 themes that focused on “compassion,” and “dedication.” One had a website informing us that “Nursing Rocks” and that “I [heart] nursing.”

Some nurses have argued for new approaches. In 2008, the Journal of Nursing Administration published “An Evidence-Based Approach to Nurses Week Celebrations.” Researchers had surveyed University of Michigan nurses about how they wished to celebrate. Rather than “trinkets,” “beauty makeovers,” or “foodstuffs,” the respondents wanted substance, including more education of the public about the true value of nursing.

Just last month, a Nigerian nurse argued on a nursing weblog that we should not “roll out the red carpet” for Nurses Day. Instead, offering specific complaints about the state of nursing in her nation, “Nursekalu” urged Nigerian nurses to use the occasion to “demand respect, better pay and working conditions!” We fear this may have reduced her chances of getting a “silent angel” award.

But should we have any annual celebrations of nursing? Perhaps such events give dispossessed groups a pat on the head in lieu of the real respect enjoyed by others, like physicians and lawyers. In a 2011 episode of Nurse Jackie, the life-saving (and notably non-angelic) main character dismissed Nurses Week as a “patronizing” event for the “overworked and underpaid.” If we stopped telling nurses how vaguely wonderful they are once a year, we might be able to see better why they deserve to be treated like serious professionals all year.

Nurses Day is 12 May because Florence Nightingale was born on that day in 1820. Later, during the Crimean War, Nightingale raised a ruckus to save British soldiers who were dying of preventable disease because they were not given adequate resources by their own government. The fierce advocate described her work this way: “I stand at the altar of murdered men, and while I live, I shall fight their cause.” Do you think she would add, “I [heart] nursing”?

Feature image credit: An Indonesian woman comforts her daughter as Registered Nurse Renee Cloutier (center) of Project Hope disconnects an intravenous catheter from her arm aboard the hospital ship USNS Mercy (T-AH 19) on Feb. 23, 2005. Photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Rebecca J. Moat, U.S. Navy. Defense.gov News Photo 050223-N-8629M-050 by U.S. Military. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Overcoming the “angel” perception of nursing appeared first on OUPblog.

“Daemonic preludium”, an extract from The Daemon Knows

Hailed as ‘the indispensable critic’ by The New York Review of Books, Harold Bloom has for decades been sharing with readers and students his genius and passion for understanding literature and explaining why it matters. In The Daemon Knows, he turns his attention to the writers of his own national literature in a book that is one of his most incisive and profoundly personal to date. The following is an extract placing Walt Whitman and Herman Melville ‘in conversation’ with one another.

Our two most ambitious and sublime authors remain Walt Whitman and Herman Melville. Whitman creates from the powerful press of himself; Melville taps his pen deeply into the volcanic force of William Shakespeare.

American Shakespeare for the last two centuries has been a prevalent obsession, a more nervous and agile relationship than the bard’s cultural dominance in Britain. Emerson remarked that the text of modern life was composed by the creator of Hamlet. Moby-Dick, Shakespearean and biblical, relies upon Ahab’s fusion of aspects of Macbeth and of Lear. Consciousness, an ordeal in Emily Dickinson, Henry James, and William Faulkner, shares the quality of that adventure in self that is the Shakespearean soliloquy.

Charles Olson, poet and seer, pioneered the study of Shakespeare’s influence upon Moby-Dick. Others have expanded his recognition, and there is more to be apprehended; Macbeth, King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra, and above all Hamlet reverberate throughout Ahab’s odyssey. Is Moby-Dick a revenge tragedy? Only as Hamlet is: not at all. Prince Hamlet rejects Shakespeare’s play and writes his own. Does Ahab accept Herman Melville’s epic? The great captain composes his fate, and we cannot know his enigmatic creator’s intentions any more than we comprehend Shakespeare’s.

I first read Moby-Dick in the early summer of 1940, before I turned ten. My sympathies were wholly with Captain Ahab, to some degree because the Book of Job—and William Blake’s designs for it—were engraved deep within me. More than seventy years later, I teach the book annually and my judgment has not swerved. Ahab is as much the hero as Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost, or Macbeth. You can call them all hero-villains, but then so is Hamlet. I weary of scholars neighing against Ahab, who is magnificent in his heroism. Would they have him hunt for more blubber? His chase has Job’s Leviathan in view, a quarry representing Yahweh’s sanctified tyranny of nature over man.

Illustration of the final chase of Moby-Dick by I. W. Taber. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Illustration of the final chase of Moby-Dick by I. W. Taber. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Moby-Dick is an ecological nightmare; so are we. Melville’s cause is not “save the whales” but “strike the sun if it insults you and strike through the white pasteboard mask of all visible things at God, who has degraded you.” Ahab has passed through Parsee Manichaeism and arrived at an American gnosis, ruggedly antinomian. Yes, Ahab is a dictator who drowns his entire crew with him, except for Ishmael. What would you have? Yahweh’s Leviathan cannot lose; should Ahab yield to Starbuck, who informs him that he only seeks vengeance on a dumb brute? The Promethean captain ought to abhor himself and repent in dust and ashes? Write your own tale then, but it will not be Melville’s.

Moral judgment, irrelevant to Moby-Dick and to Shakespeare, would have provoked Dr. Samuel Johnson not to countenance Ahab nor to finish reading more than a page or two. From the best of opening sentences on, the White Whale remorselessly voyages to a heroic conclusion. Except for Starbuck and Pip, the Pequod’s company votes for its marvelous catastrophe. Ahab is possessed, but so are they (Ishmael included). As leader, their captain finds his archetype in Andrew Jackson, who represented for Melville and others the American hero proper, an apotheosis of the politics of one who characterizes the American Dream. From lowly origins he ascended to the heights of power and brought into sharper focus what is still American nationalism.

Denying Ahab greatness is an aesthetic blunder: He is akin to Achilles, Odysseus, and King David in one register, and to Don Quixote, Hamlet, and the High Romantic Prometheus of Goethe and Shelley in another. Call the first mode a transcendent heroism and the second the persistence of vision. Both ways are antithetical to nature and protest against our mortality. The epic hero will never submit or yield.

Such uncanny persistence is dangerous to all of us. We do not wish to rise crazily with Don Quixote, to plot and counterplot with Hamlet in poisoned Elsinore, to serve under doomsayer Ahab in the Pequod. But how can the reader’s sublime be better experienced than with Cervantes, Shakespeare, or Melville? Only the self-named “Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos,” is comparable to Captain Ahab in the United States. Ahab and Whitman are our Great Originals, our contribution to that double handful or so among whom Falstaff and Sancho Panza, Hamlet and Don Quixote, Mr. Pickwick and Becky Sharp take their place.

Featured image credit: Looking Down Yosemite Valley, California by Albert Bierstadt. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Daemonic preludium”, an extract from The Daemon Knows appeared first on OUPblog.

Five unusual ingredients in sweets

The number and variety of sweet treats in the world is staggering. Though many of us are familiar with the use of fresh fruits in desserts, flavorings in candy, and other ubiquitous ingredients, a great deal are unusual. They’re unusual in the sense that they’re “not commonly occurring,” or that we believe them to be so. With that, here are five ingredients you might find, but not expect, in your next dessert.

Ambergris

What it is: A waxy calculus that is created in the digestive tracts of sperm whales in response to irritation caused by the sharp, indigestible beaks of ingested squid.

How it’s used: It was an important flavoring in high-status renaissance and baroque confectionery and cookery.

What types of sweets it’s used in: Dragees, biscuits, pudding

Sperm Whale. Photo by Biodiversity Heritage Library. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Sperm Whale. Photo by Biodiversity Heritage Library. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Castoreum

What it is: A fragrant food additive harvested from castor sacs at the base of a beaver’s tail.

How it’s used: As an occasional flavoring ingredient, commonly as a vanilla substitute.

What types of sweets it’s used in: Baked goods, candies, puddings, beverages, gum, cigarettes, Swedish schnapps (specifically BVR HJT)

Happy Beaver. Photo by Steve. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Happy Beaver. Photo by Steve. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Insects

What it is: A small arthropod animal that has six legs and generally one or two pairs of wings.

How it’s used: Traces of them show up in about every edible substance but is sometimes used as a “gross out” novelty factor.

What types of sweets it’s used in: Chocolate-covered (e.g., ants), encased in lollipops (e.g., Cricket Lick-It Suckers), in toffee (e.g., InsectNside Scorpion Brittle)

Ant peering over the edge of a leaf. Photo by photochem_PA. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Ant peering over the edge of a leaf. Photo by photochem_PA. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Pekmez

What it is: A grape molasses made from freshly extracted grape juice that is simmered to condense to roughly one-third or one-fourth of its original volume. Also known as petimezi in Greek; vincotto, sapa, or saba in Italian; dibs el inab, debess ennab, or debs el enab in Arabic.

How it’s used: As a sweetener—popular when sugar was expensive.

What types of sweets it’s used in: Cookies, Turkish delight, fried dough puffs, as a topping for various desserts

Grapes. Photo by tribp. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Grapes. Photo by tribp. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Tragacanth

What it is: A gum exudate obtained from various species of wild goat thorn native to the Mediterranean and Middle East.

How it’s used: As a binding agent of gum paste and other edible modeling materials.

What types of sweets it’s used in: Edible decorations, occasionally used in a few specialized goods and biscuits during the early modern period

Photo by Lisa Marklund. CC By 2.0 via Flickr.

Photo by Lisa Marklund. CC By 2.0 via Flickr.Are there any other ingredients in sweets that you think are unusual?

Featured image: Baking. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Five unusual ingredients in sweets appeared first on OUPblog.

Carefully constructed: The language of Franz Kafka

A few months ago I took part in a discussion of Kafka on Melvyn Bragg’s radio programme In Our Time. One of the other participants asserted that Kafka’s style describes horrific events in the emotionally deadpan tone of a bureaucrat report. This struck me immediately as wrong in lots of ways. I didn’t disagree, because time was short, and because I wouldn’t want to seem to be scoring points of a colleague. But it occurred to me that the speaker, a professor of English Literature, had probably only read Kafka in English, and only in the old translations by Willa and Edwin Muir. The Muirs’ translations are beautifully expressed (though not always accurate), but they read rather greyly, and have no doubt contributed to the view that Kafka, himself a civil servant, introduced into literature the language of bureaucracy.

Deadpan style

How true is this? It applies to passages from The Trial and The Castle where bureaucratic procedures are being satirized. So Kafka adopts the language of bureaucracy for a specific purpose. But his language isn’t otherwise unemotional. Josef K. in The Trial experiences a range of unenviable emotions, including surprise, worry, fear, curiosity, lust, annoyance, anger, and depression, all of which are clearly indicated both directly and indirectly.

When Kafka writes in a deadpan style, he again does so for a specific purpose. Take the opening sentence of The Man who Disappeared, the novel formerly known in English as America:

“As the seventeen-year-old Karl Rossmann, who had been sent to America by his poor parents because a servant-girl had seduced him and had a child by him, entered New York Harbour in the already slowing ship, he saw the statue of the Goddess of Liberty, which he had been observing for some time, as though in a sudden blaze of sunlight.”

On the surface, this sentence seems to carry us straight into the action while giving us the basic factual information necessary to understand Karl Rossmann’s situation. But once we have assimilated the data crammed into the sentence, we may do a double take. Karl has been sent across the world, not because he is guilty, but because he is the victim of a crime. All the agency is ascribed to the servant-girl. (We learn later that she is twice Karl’s age, and that she took the initiative in seducing this very innocent teenager; Kafka gives us a raw and distressing account of what would nowadays be called child abuse.)

Franz Kafka, by Atelier Jacobi, 1906. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Franz Kafka, by Atelier Jacobi, 1906. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.So between the lines of his calm exposition, Kafka confronts us with a monstrous act of injustice in which the victim is punished. And this prefigures the subsequent action of the novel, in which the well-meaning Karl repeatedly gets into situations in which he seems to be at fault and is punished with expulsion. Rarely has so much been achieved by understatement.

Translating Kafka

But, it will be said, Kafka wrote in German. And one still occasionally encounters the claim that he wrote in a special dialect called ‘Prague German’ with a restricted vocabulary. This myth originates in late nineteenth-century nationalism. Conservatives who extolled rural life claimed that authentic German was spoken in the countryside and that the language of town-dwellers, like their physiques, was enfeebled. In fact Kafka’s written German uses the full resources of the German language and shows in particular how steeped he was in classic German literature from Goethe down to such contemporaries as Thomas Mann. He uses some dialect terms typical of the southern German language region. Thus in The Man who Disappeared Karl Rossmann brings breakfast on a ‘Tasse’ (tray), which must seem an impossible balancing feat to a northern German for whom ‘Tasse’ means cup. But, although contemporaries could tell from his accent that he came from Prague, there is little or nothing in his written texts to show his origins.

So what is distinctive about Kafka’s style? From my own experience of translating Kafka, I would say it is his control of syntax. When he uses long sentences, they are carefully constructed so as to lead up to the final word or phrase. When translating The Man who Disappeared, I followed this method so far as I could, as in the sentence quoted above. In doing so I was conscious of the currently widespread view that one should avoid domesticating foreign texts. But there were several constraints.

It’s not always as easy in English as in German to construct long sentences without clumsiness. Readers of English expect the point of a sentence to be apparent immediately, whereas with a German sentence your interpretation is provisional until you reach the end. And there were also external constraints. My editor was necessarily concerned about sales and therefore insisted that I should produce an easily readable text. Long sentences had therefore to be used sparingly – a good rule in writing English, but one which imposes limitations on the translator.

That said, translating Kafka was a relatively easy task, and a pleasurable one. Few writers had such a natural, immediate sensitivity to language as Kafka had. He hugely admired Flaubert; Sentimental Education, which he read in French, was his favourite novel. But while Flaubert laboured over his sentences, Kafka, in his rare spells of productivity, produced his fiction with the minimum of revision. He once wrote: ‘If I write “He looked out of the window”, it’s already perfect.’ That may sound like a boast, but it’s a perfectly accurate description of his writing.

Image credit: Psychedelic, by Activedia. Public domain via Pixabay.

This post originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog, 2 July 2015.

The post Carefully constructed: The language of Franz Kafka appeared first on OUPblog.

July 9, 2015

How much do you know about Ramadan?

Every day during the ninth month of the Islamic lunar calendar, Ramadan observers spend their daylight hours fasting. During Ramadan, a sense of belonging, social cohesion, and togetherness is reinforced among community members. There is no eating or drinking from sunrise to sunset. Observers also abstain from sexual activity. At the end of the fast, delicious meals are shared with family and friends. Eid al-Fitr, a three-day festival, awaits observers at the end of Ramadan. How much do you know about the rich history and cultural importance of this religious holiday? Test your knowledge with this challenging quiz.

Learn more about the cultural traditions of Ramadan with Oxford Islamic Studies Online.

Image Credit: “Ramadan lanterns, Souq el Maadi, Cairo, Egypt” by B. Simpson Cairocamels. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How much do you know about Ramadan? appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten questions about Braddock’s Defeat

On 9 July 1755, British troops under the command of General Edward Braddock suffered one of the greatest disasters of military history. Braddock’s Defeat, or the Battle of the Monongahela, was the most important battle prior to the American Revolution, carrying with it enormous consequences for the British, French, and Native American peoples of North America. We sat down to discuss its complex history with David Preston, whose archival research and fieldwork has provided new insight into a pivotal moment long obscured by misunderstanding and mythology.

Who was the real Edward Braddock?

At the beginning of the French and Indian War in 1755, the British government sent Major General Edward Braddock to Virginia with two regiments of regulars to capture the French Fort Duquesne in the Ohio Valley. Over the course of history, Braddock has been typecast as a brash and arrogant Redcoat who ignored the dangers of fighting in America’s woods. The archival record proves that Braddock was a realistic and capable officer who brought his army to the cusp of victory. There is no evidence, for example, that Braddock purposefully spurned the support of Native allies, marched blindly into the woods, or rode across the mountains in his coach and four.

How noteworthy was Braddock’s march?

Braddock’s march of nearly 125 miles across the Appalachian Mountains represents one of the greatest engineering accomplishments of early American warfare. Hiking many extant portions of Braddock’s Road was an epiphany that changed my understanding of the campaign and fueled my appreciation for how Braddock’s army was able to quickly carve a 12-foot-wide military road through such daunting Appalachian ridgelines, rivers, and swamps.

“General Braddock Engraving” by William Sartain, 1899. Public Domain via Library of Congress.

“General Braddock Engraving” by William Sartain, 1899. Public Domain via Library of Congress.What was the experience of the French?

Historians have generally ignored French and Native perspectives on the 1755 campaign. The French were outnumbered, outgunned, and faced crippling supply problems in their Ohio Valley posts. They despaired of their inability to halt or slow Braddock’s relentless march. However, convoys of French reinforcements led by a veteran officer, Captain Beaujeu, came to Fort Duquesne after an epic 700-mile voyage from Montreal, arriving only a few days before the fateful battle at the Monongahela.

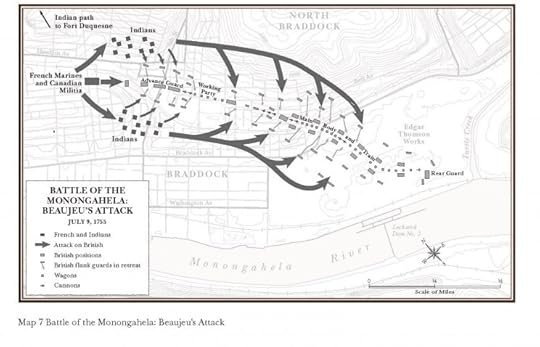

What role did Captain Beaujeu play in the French and Native American victory?

A newly discovered French account from the Archives du Calvados transforms our understanding of French and Native American leadership and tactics at the Battle of the Monongahela. The French commander, Captain Beaujeu, sent out Native scouts who brought him exact intelligence on the location and disposition of the British. Dividing his force into three parallel columns, Beaujeu organized a frontal attack on the British column with his Canadian troops. He instructed the Indians to spread out in the woods on the right and the left, and to withhold their fire until he had engaged the British. The Monongahela was neither a meeting engagement nor an ambush, but a well-planned and executed French and Indian attack on a vulnerable British column.

How many Indian nations fought against Braddock?

A remarkable coalition of 600 to 700 Native American warriors, drawn from half the continent, fought against the British on 9 July 1755. With only 254 French marines and militiamen present, Native warriors represented two thirds of the force that defeated Braddock. Their numbers, tactics, firepower, and discipline were ultimately responsible for the shocking collapse of a conventional British army.

“Trace of Braddock’s Road on Big Savage Mountain, Maryland” by David L. Preston. Used with permission.

“Trace of Braddock’s Road on Big Savage Mountain, Maryland” by David L. Preston. Used with permission.How many casualties did the British suffer?

The Battle of the Monongahela ranks as one of the greatest disasters in all of military history. In the space of four hours, a powerful British army on the cusp of victory dissolved into a mob of panic-stricken individuals. One British record shows that 976 (66%) of the 1,469 personnel who crossed the Monongahela River on 9 July were killed, wounded, or missing.

How did Braddock’s Defeat impact Indian nations?

Victory at the Monongahela greatly fueled Native American alliances with the French in the Seven Years’ War. Triumphant warriors returned to their communities having achieved their main objectives: a victory achieved with minimal casualties, as well as many tokens of war, including scalps, captives, and war materiel (horses, uniforms, weapons, and other supplies seized from Braddock’s captured supply wagons).

How did Braddock’s Defeat transform American warfare?

Braddock’s Expedition helped shift American warfare’s center of gravity to North America’s interior. Prior to 1755, the British had been unable to project large military forces west of the Appalachian Mountains, and had only been able to strike coastal targets on the Atlantic or the St. Lawrence River. Braddock’s Expedition symbolized the new continental reach that British forces achieved during the French and Indian War. The Monongahela disaster also prompted the British and Americans to form light infantry and ranger units (such as Rogers’ Rangers) to meet the challenge of French and Native American irregulars in the woods.

What were the consequences of Braddock’s Road?

Battle of the Monongahela: Beaujeu’s Attack. Author map, courtesy of Mapping Specialists, Ltd.

Battle of the Monongahela: Beaujeu’s Attack. Author map, courtesy of Mapping Specialists, Ltd.After the British finally captured Fort Duquesne in 1758, Braddock’s Road proved to have long-term consequences for American westward expansion. The scars of Braddock’s Road, still visible today, attest to the many thousands of Euroamerican settlers who followed in the British army’s wake, seeking land and opportunity in the Ohio Valley after the war. This was a migration that fueled future conflicts with the region’s Native inhabitants.

How is Braddock’s Defeat remembered in history?

Braddock’s Defeat shaped a distinctly American identity and highlighted differences between the 13 colonies and the British Empire. Revolutionaries frequently recalled the disaster as evidence that British regulars could be defeated through American tactics. The Monongahela had been a defining military experience for a generation of officers who fought in both the Seven Years’ War and the Revolutionary War. George Washington, Horatio Gates, Charles Lee, Daniel Morgan, and Adam Stephen were among the veterans of Braddock’s Expedition who carried its military lessons forward into the Revolutionary War.

Image Credit: “Washington at the Battle of the Monongahela” by Emanuel Leutze, 1858. Used with permission from Braddock’s Battlefield History Center and Braddock Carnegie Library Association. Photograph courtesy of David Kissell.

The post Ten questions about Braddock’s Defeat appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers