Oxford University Press's Blog, page 639

July 23, 2015

Beauty and the brain

Can you imagine a concert hall full of chimpanzees sitting, concentrated, and feeling ‘transported’ by the beauty of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony? Even harder would be to imagine a chimpanzee feeling a certain pleasure when standing in front of a beautiful sculpture. The appreciation of beauty and its qualities, according to Aristotle’s definition, from his Poetics (order, symmetry, and clear delineation and definiteness), is uniquely human.

A sense of beauty requires a brain as complex as the human brain: able to generate self-consciousness, thoughts and feelings, neural attributes that no chimpanzee or any other animal possesses. Beauty is a feeling that can only be born in the brain of an educated person within a given society. Beauty is a sentiment that emerges from the functional dialogue between the distributed networks of the sensory and association areas of the cerebral cortex, in conjunction with the activity of the emotional brain (the limbic system). Indeed, beauty is knowledge and emotion, and as such, is also individual, since it arises from personal memories and experiences in concert within the culture in which we live.

The appreciation of beauty evoked when someone is faced with a painting of Velazquez, the hurtful colours of Van Gogh, a sculpture by Rodin, the harmonious force and sublime cadences in the music of Beethoven, or the grandiose architecture of Gaudí’s Sagrada Familia, requires a high degree of visual and auditory consciousness, and a refined education in sensory perception. But beauty can also be evoked beyond the sensory world in ideas. Of course, a physicist could speak of the beauty of the general theory of relativity.

These days, new hypotheses are arising in neuroscience, based on scientific evidence, on how the brain may construct the abstractions (ideas) which are the building blocks of knowledge. We know that there are networks in the brain in which neurons respond to a single perspective of an object (form, orientation, and depth) but not to other perspectives. We also know that there are neurons that respond to the presentation of the entire object irrespective of the perspective presented, giving probable indication that these latter neurons synthesize all views from the previous neurons. Some of these neurons respond not just to the specific object presented but to different objects of similar shapes and colors. It has been suggested that specific neural circuits containing these last neurons are responsible for the construction of abstractions or an “ideal” object that may accommodate many different objects within that same category. Therefore, when nature shows us hundreds of birds of all shapes and sizes, movements and colors, songs and different behaviors, the brain is capable of creating the concept, the idea, of a “bird,” which summarizes all birds in the world. This “universal” bird is an abstraction created by the brain, an idealization of a bird that neither exists nor could exist in reality, thus making a “pure and immutable essence of the bird,” as Plato might have posited. This is how the human brain works, by categorizing and classifying the sensory world through concepts and ideas. Using this brain-based process of consciousness and abstraction, man attained the basic principles for thought, language, art, and communication. Art, in fact, is abstract and symbolic cognition, plus emotion.

Today, we know in part how the flow of sensory information through the different hubs and nods located in the sensory areas of the cerebral cortex reaches the emotional areas of the brain. It is in this last area that sensory information is labelled with reward or punishment, pleasure or pain. It is after this emotional labeling that cognitive processes are elaborated in the association areas of the cerebral cortex. Therefore, the brain, and particularly the brain of an artist, already works with ideas and abstractions that are emotionally meaningful. This should be very relevant for understanding the act of creation and the capacity of a work of art to evoke beauty. But what seems more interesting when talking about beauty, especially in relation to individuals contemplating a work of art, is that beauty does not really exist in the artistic work. Beauty is genuine and personal, created by those who contemplate the artwork. In other words, the beholder would actively create in his own brain his own conception of beauty which would involve both knowledge (abstraction or idea) and emotion and pleasure (pleasure of the finest nature, as Immanuel Kant would point out, involving less satiety and more durability).

All this leads us to understand how a work of art can be found beautiful for several people but not for others. Or how the beauty of an idea may be appreciated by just one person in the world. Or conversely, how a sculpture or a painting or any other piece of art could be recognized as beautiful by millions of people. In fact, it appears that when that creative personal process of beauty takes place in a large number of people in front of a specific masterpiece, it is then that the work is recognized as universally sublime.

Featured image: Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Wholtone (2008). CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Beauty and the brain appeared first on OUPblog.

Down the doughnut hole: fried dough in art

Fried dough has been enjoyed for centuries in various forms, from the celebratory zeppole of St. Joseph’s Day to the doughnuts the Salvation Army distributed to soldiers during World War I. So important were doughnuts for boosting troop morale that when World War II came around, the Red Cross followed closely behind the US Army as it advanced across Europe, offering doughnuts from trucks specially outfitted with vats for deep-frying. After the war, chains like Dunkin’ Donuts began dotting the landscape, first in the United States, and then worldwide. Our national love affair with these fried treats is expressed in National Doughnut Day (5 November), National Jelly-Filled Doughnut Day (8 June), and National Cream-Filled Doughnut Day (15 June). The granddaddy of them all is National Donut Day, the first Friday in June, initiated in 1938 by the Salvation Army. But it may have been the cartoon character Homer Simpson who consolidated the doughnut’s status as an American icon when he declared that he’d sell his soul to the devil for his beloved doughnuts.

Homer’s remark prompts us to wonder: If William Blake found a world in a grain of sand, then what’s in a doughnut, or rather, in its hole? Is the hole present as empty space, or is it absent, a void? Is a doughnut hole still a doughnut?

The cartoonist Bill Griffith picked up on this existential note in one of his “Zippy the Pinhead” strips from 1994, titled “A Hole New Thing.” Zippy contemplates Emily Eveleth’s luminous doughnut paintings, giving Griffith a chance to engage in lively verbal play, riffing on the doughnut, its hole, and their commodification in American culture. His text reads:

“Zippy Dear, you seem preoccupied tonight—you’ve barely touched your Krispy Kreme!”

“I have seen th’ doughnuts of Emily Eveleth!!”

“Oh? Does she work at Hostess…or Dunkin’? And is our relationship threatened by your involvement with her baked goods?”

“Emily Eveleth aesthetically selects doughnuts and transforms them to a higher level of doughnutness!!”

“Now I know why you’ve been so glazed lately!”

“If the doughnuts of Emily Eveleth met the apples of Paul Cezanne, would they fritter away their time discussing the holeness of the universe??”

“Delicious art, Emily!”

Though Eveleth’s doughnuts are highly realistic, she animates them beyond their objectness, making them appear at once concrete and abstract, hinting at other realms. Eveleth sometimes presents solitary doughnuts, as in “Order” (2007), in which a lone doughnut shimmers with light against a spare, flat background, tempting us to pleasure. The painting’s simplicity highlights the textured airiness of the pastry, its sugary glaze. But this is no Pop-Art confection in candy colors; the longer we gaze at this initially alluring doughnut, the more the jelly appears as a violation, like blood seeping from a wound, reminding us that pleasure can also inflict pain. While the foreground shimmers with light, the doughnut mediates between the viewer and the void of the black background, suggesting the sense of loss that ensues once desire has been fulfilled.

Jelly doughnuts in particular engage Eveleth’s imagination. An early prototype for the sugary pillows we enjoy today is found in a recipe for “Gefüllte Krapfen” in Kuchenmeisterei (Mastery of the Kitchen), a cookbook for the elite that was published in Nuremberg in 1485. This early version of jelly doughnuts consisted simply of pieces of leavened dough deep fried in lard and sandwiched together with jam. You can get a sense of this sandwich style in New Zealand photographer Peter Peryer’s striking image of plump, cream-filled doughnuts dripping with jelly. By contrast, today’s jelly doughnuts are mechanically injected with a syringe, revealing only a small orifice to suggest the sweet surprise within.

Doughnuts carry not only philosophical and sexual connotations along with their promise of deliciousness. When prepared as a final indulgence before Lent (the Fastnacht) or for a celebration of the Hanukkah miracle (sufganiyot), they emblematize larger religious ideas. As Zippy says, the artist Emily Eveleth raises doughnuts to a “hole” new level, imbuing them with longing and a desire for something beyond the simple taste of sweet on the tongue. Here we face the essence of the jelly doughnut, its insides exposed, inducing feelings of melancholy and desire.

Headline image: Photo by Ryan A. Monson. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Down the doughnut hole: fried dough in art appeared first on OUPblog.

July 22, 2015

Praising a cat to sell a horse

For a long time the etymology of the word bad has been at the center of my attention (four essays bear ample witness to this fact). The latest post ended with a cautious reference to the idea that Middle Engl. bad ~ badde (a noun that occurred only once in 1350 and whose meaning seems to have been “cat”) is, from an etymological point of view, identical with the adjective bad. The context of that single citation justifies the cautious gloss “cat” in the OED, and the Middle Dutch partial look-alike signifying something like “doll; pet child” gives this interpretation a tiny boost. I realize that my conclusion will carry conviction only to those who will agree that bad came into existence as a baby word, like booger and its kin. The sphere of baby words is circumscribed by the experience of a very small child; pets, especially cats, figure prominently in it. The same syllable is often applied to any toy, a doll, a cat, and all adults, for the phonetic possibilities of a one- and even two-year old are limited. Therefore, homonymy rules the young speaker’s usage. The complex b-d, as follows from words like baby and daddy, does occur in the vocabulary of infants. My aim consists in selling this etymology of bad and badde (for the moment, my hobby horse) by praising a few idioms with the word cat, so I am swopping one cat for another, and there is no real dobbin in the bargain.

Idioms with the word cat are often baffling. Perhaps the most famous of them is to rain cats and dogs, which I discussed long ago. Despite some doubts expressed in the comments, I still think that the explanation in the note I cited is plausible. It highlights the problem of dealing with cat: the word may refer not to the animal but to some object called cat, as happened, I believe, with heavy rain. Two phrases among dozens we find in English are particularly curious: not enough room to swing a cat in, and to whip the cat. The first is known very well, while the second is technical, dialectal, and probably obsolete. My sources are dictionaries and the suggestions I found in the old issues of Notes and Queries [NQ].

About swinging a cat I can say little in addition to the fact that the OED quotes a relevant 1665 example. In books on the history of games I was unable to discover any information about holding a cat by the tail and swinging it, but people have often been cruel to animals, and one can imagine the pastime that gave rise to this saying. Still, as a description of narrow space, the expression sounds odd, to say the least. The reference to “the former sport of swinging a cat to the branch of a tree as a target” sounds less than fully convincing, to use diplomatic language, because no evidence turned up to prove that such a sport existed and because trees don’t grow in small rooms. Those authors who mention the game give no references (the usual problem with books on phrases, from Brewer’s classic on) and for that reason should be treated with mistrust. The other hypothesis looks more realistic at first sight. Allegedly, cat is here a cat-o’-nine tails. If this is correct, the idiom must have originated as naval slang. But, as pointed out by everybody who has dealt with the idiom, the word cat-o’-nine-tails was found in English texts later than the phrase in question (which of course says very little about their currency in everyday speech), so that this conjecture looks dubious on chronological grounds. Besides, no etymologies offered so far clarify the allusion to restricted accommodation. I’ll return to swinging a cat below.

Whipping the cat?

Whipping the cat?By contrast, the literature on whipping the cat is not too sparse, and the OED has a good deal to say about this idiom. At different times, it could mean “to get drunk,” “to lay blame for one’s offence on someone else,” “to work as an itinerant tailor, carpenter, etc. at private houses by the day,” “to play a practical joke…,” and “to practice (practise) extreme parsimony.” No pre-seventeenth-century examples are given. It causes surprise that both picturesque idioms appeared in English so late and approximately at the same time. Joseph Wright in The English Dialect Dictionary gives several examples of the saying under whip and under cat, along with the nouns whip–cat and whip-the-cat “an itinerant tailor.”

The most informative note on the subject was written by L. R. M. Strachan, a distinguished philologist, in NQ, vol. 168, 1935: 357 (just in case: Strachan rhymes with drawn). Rather curious is the heading of the article reprinted in NQ (2nd Series/IX, 1860: 325) from a Philadelphia newspaper for June 1793. American correspondent Uneda, a frequent contributor to NQ, didn’t say which newspaper published the report. It dealt with the executions and accusations of treason of the members of the Convent during the bloodiest days of the French revolution. It is titled “Whipping the Cat.” The allusion is, as I think, to one “patriot” laying blame on another.

In Australia, whipping the cat was used to denote a foolish action and competed with flogging pussy, while in the Australian bush it was synonymous with crying over spilt milk. The French idiom il n’y a de quoi à fouetter un chat “never mind it; the whole thing isn’t worth a straw,” literally, “no need to whip a cat” (to which I can add avoir d’autres chats à fouetter “to have other things to do or to worry about [other cats to whip]”) has also been noticed, but despite the presence of the same image and nearly the same intent in both languages, the origin of the expression in English and French does not become clearer. Who whipped the cat and why was it considered a thing of little consequence?

The French idioms do not seem to be old; they are probably even more recent than their English analogs. It has been suggested that French chat “cat” stands for chas “eye of the needle” and that the phrase originated in the language of tailors (should we add: in their international slang?). Tailors loom large in the history of the English saying, but whether chat stands for chas, and, even if it does, how the English and the French phrases interrelate (if at all) remains unclear. The obscene origin of fouetter, allegedly standing for foutre (the French equivalent of our F-word), and especially of the phrase flogging the pussy is not unthinkable but unlikely. Such associations must have occurred to people in retrospect.

This is the protagonist of Gogol’s short story “The Overcoat.” Cat fur for marten fur was good enough for him.

This is the protagonist of Gogol’s short story “The Overcoat.” Cat fur for marten fur was good enough for him.Grose (A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue) cited a story that has been made much of in the discussion of whipping the cat. It is about a sturdy country nincompoop who is told that a cat can pull him across a pond. A wager is laid, the people on the other side pull the rope, whip the cat attached to it, and produce the impression that the unfortunate animal has done the trick. This is a most unlikely source of our idiom. Of all the senses of the phrase to whip the cat the one dealing with itinerant tailors and other journeymen is (or was) by far the best-known. It looks as though in their lingo cat meant something very small (as chat does in French!), and whipping it was tantamount to being engaged in the pettiest business thinkable. In Gogol’s heart-breaking short story “The Overcoat,” an impoverished clerk needs a new overcoat. Saving for it takes a long time, but finally he scrapes together the necessary sum. He and his tailor go shopping for the best cloth and a good collar. Marten fur proves to be too expensive, and they substitute cat fur for it. Is it possible that cat was a habitual replacement for expensive furs?

If cat indeed stood for “a small, insignificant, cheap thing,” it explains the attested reference to parsimony (to whip the cat would be “to save every farthing”). The sense “to cry over spilt milk” belongs here too, at least partly. And we may recall that another exercise in futility is to flog (whip, beat) a willing (dead) horse. Laying blame on others and playing practical jokes were then fanciful extensions of the idiom’s initial meaning. “To get drunk” (the sense supported, among other things, by a sign on a pub discussed by a correspondent to NQ) could have been prompted by someone drinking one glass after another and becoming intoxicated by slow degrees. The similarity between the English and the French idiom remains a puzzle. By contrast, if cat did at one time have the meaning “something very small and insignificant,” no room to swing a cat in stops being absolutely opaque. Here then is my cat. Will it jump?

Image credits: (1) The Tailor of Gloucester at Work. Beatrix Potter, 1902. Public domain via WikiArt. (2) The cover of The Overcoat by Igor Grabar, 1890s. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Praising a cat to sell a horse appeared first on OUPblog.

“a rather unexpected start”: Alice Northover on the OUPblog

On the tenth anniversary of OUPblog, we’ve asked past editors to reflect on their experiences and favorite memories. Today we speak to Alice Northover, our current blog editor who joined in 2012.

I had a rather unexpected start for the OUPblog.

I spent my first day getting to grips with all the customizations and plugins of the blogging platform. I was armed with quite possibly the most amazing exit memo ever written (thank you Lauren). I was fully confident that a smooth transition was underway.

On the second day I found out that my official introduction to the blog wouldn’t be happening as Kirsty was going on maternity leave immediately. I was left to run the blog without any official handover. What three editors and two UK editors had spent six and half years building was left in my hands. I was directionless, overwhelmed, and alone (not really; Nicola Burton was on board as UK editor).

I did have a vague idea of the OUPblog ethos. I’d known the blog by reputation for some time (making the rounds in publishing circles). I’d read the odd article here and there. It was one of the things that made me so excited to join Oxford University Press.

As I skimmed through the archives and reviewed incoming blog posts, I learned who the regular contributors were and what topics were typically covered. Beyond the usual spelling and grammar, I picked through each author’s approach, what had intrigued them and would ultimately intrigue our readers. I girded myself for the painful process of rejecting work that was not fit for the blog, either in terms of quality or placement.

While gradually cultivating the tone and tenor of the blog, I searched for ways to reach new audiences. My predecessors had built this amazing blog; more people should be reading it.

First, I looked to increase the breadth (and consequently volume) of our publishing. Moving from origins in the US Publicity team and the gradual inclusion of the UK with Kirsty, our new focus was bringing all of our academic publishing, in one form or another, into the OUPblog. Not just books, but journals, online reference, printed music, higher education, and dictionaries (which had previously only made the occasional appearance) would now be part of our regular editorial content. An OUPblog Editorial Board was formed with representatives from different departments to generate ideas and commission content. People who would normally never work with each other were soon chatting about what possible nerdy tie-ins we had for new movies over the phone every month.

Second, I looked to overhaul our technology and technical practices. Six years is a long time in technology and much of the blog was dragging behind despite periodic updates and redesigns. Titles, urls, and site structure needed work. Users were visiting an online magazine, but our navigation didn’t make it easy. Excess code and plugins dragged down our page load time. Our mobile site was functional but boring, and clearly wasn’t attracting the desirable wasting-time-on-my-iPhone audience. We had difficulty integrating with other OUP websites, and moving from one to the other was far from seamless. Google and other sites clearly saw the value in our content, but we needed a better way of presenting it.

After a series of small fixes, we began work in earnest on the next major redesign of the OUPblog, our most ambitious to date, in 2014. I consulted with staff across the Press. I drew up a lists of wants and needs, problems and glitches, for our developer. I put together a ‘look book’ of OUP websites, competitor websites, and those which we desired to emulate. Most importantly, we made the investment to switch to responsive design, giving us a beautiful, consistent experience across phones, tablets, and desktops. After months of work, in August 2014, our updated site launched and our traffic skyrocketed. The appetite for smart blogging is there, and growing, given the right balance and technical proficiency.

Not only has our blog prospered over the last ten years, but our once small blogosphere has flourished. Other university presses, such as Yale, Princeton, and Columbia (to name a few), have built up their blogs from small operations to substantial, regularly updated sites. New online magazines, such as Aeon, Berfrois, The Conversation, and Pacific Standard, specialize in approachable academia. JSTOR Daily recently won an award as the new kid on the block. It’s great to see so many seeking and sharing academic insights for the thinking world.

Featured image: Phone By Thom. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post “a rather unexpected start”: Alice Northover on the OUPblog appeared first on OUPblog.

All the Year Round, A Tale of Two Cities, and Great Expectations, 1859–1861

We continue our Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group this week with some biographical background on the author around the time of Great Expectations’ publication. The following is an extract from the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography‘s entry of Charles Dickens.

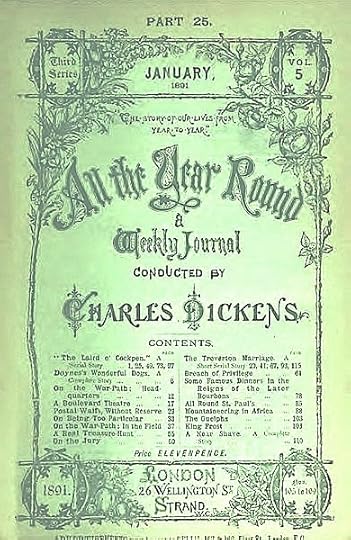

When, in 1859, Dickens decided to publish a statement in the press about his personal affairs he expected that Bradbury and Evans would run it in Punch, which they also published. He was furious when they, very reasonably, declined to insert “statements on a domestic and painful subject in the inappropriate columns of a comic miscellany” (Patten, 262). Dickens therefore determined to break with them completely and to return to his old publishers Chapman and Hall. Bradbury and Evans’s co-operation was needed, however, for the launch of the elegant Library Edition of Dickens’s works (twenty-two volumes published, 1858–9; re-issued with illustrations and eight more volumes, 1861–74). But Dickens forced the dissolution of Household Words, owned jointly by himself and Bradbury and Evans, and the last number appeared, despite all the hapless publishers’ efforts to prevent the closure, on 28 May 1859. Dickens, meanwhile, had begun publishing from, 30 April, a new weekly periodical with the same format and at the same price as Household Words called All the Year Round. Wills continued as his sub-editor and he and Dickens were the sole proprietors, Dickens owning 75 per cent of the shares as well as the name and goodwill attached to the magazine. While maintaining the tradition of anonymity for all non-fictional contributions, All the Year Round differed from its predecessor in various ways, not least in its greater emphasis on serialized fiction. A new instalment of the current serial stood always first in each weekly number, and Dickens editorially proclaimed “it is our hope and aim [that the stories so serialized in the journal] may become a part of English literature” (All the Year Round, 2.95).

Dickens himself inaugurated the series in spectacularly successful fashion with his second historical novel, A Tale of Two Cities (serialized from 30 April to 26 November 1859), the basic plot of which was inspired by the story of the self-sacrificing lover Richard Wardour (Dickens’s role) in The Frozen Deep. In this novel, the second half of which takes place during the French Revolution, Dickens set himself the task, he told Forster, “of making a picturesque story, rising in every chapter with characters true to nature, but whom the story itself should express, more than they should express themselves, by dialogue”, glossed by Forster as meaning that Dickens would be relying “less upon character than upon incident” (Forster, 730, 731). In its tightly organized and highly romantic melodrama, and the near-absence of typical ‘Dickensian’ humour and humorous characters, A Tale of Two Cities certainly stands apart from all his other novels, although—as in his earlier historical novel—one of the great set pieces of the book is the anarchic destruction of a prison, an event to which Dickens’s imagination responded with powerful ambiguity. Thanks partly to this new Dickens story, and partly to a vigorous advertising campaign organized by Wills, All the Year Round had an initial circulation of 120,000. Wilkie Collins’s sensationally popular ‘sensation novel’ The Woman in White followed A Tale of Two Cities in the serial slot, contributing not a little to the maintenance of the magazine’s impressive circulation figures. These eventually settled down to a steady 100,000 with an occasional dip but soaring always (up as far as 300,000) for the special ‘extra Christmas Numbers’. Dickens eventually wearied of this latter feature, however, and killed it off after 1867.

Cover of magazine 3rd series “All the Year Round” by Charles Dickens 1891. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Cover of magazine 3rd series “All the Year Round” by Charles Dickens 1891. Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsCompared with Household Words, All the Year Round features far fewer journalistic pieces by Dickens himself, the Uncommercial Traveller essays (see below) notwithstanding, and had a much greater focus on topics of foreign interest, notably the struggle for Italian unification, and much less concern for the political and social condition of England than the earlier magazine. Nor could it be quite so topical as Household Words since every issue had to be finalized a fortnight before its due publication date, Dickens having contracted with the New York publishers J. M. Emerson & Co. to send them stereotype plates of every issue in order to ensure its simultaneous appearance on both sides of the Atlantic (an arrangement later somewhat modified).

On 28 January 1860 Dickens began contributing to his new journal a series of occasional essays in the character of the Uncommercial Traveller. They were discontinued when he began work in earnest on Great Expectations (1 December 1860 – 3 August 1861) and not resumed until 2 May 1863 (carrying on until 24 October 1863). The Uncommercial Traveller essays, which feature some of the finest prose ever written by Dickens, take sometimes a quasi-autobiographical form, with reminiscences of childhood, like Nurse’s Stories or Dullborough Town (that is, Rochester), and are sometimes examples of superb investigative reporting, notably of lesser-known aspects of life in London; yet others focus on the process of travel itself, in its many various forms.

As for his fictional writing, Dickens had intended his next novel to be published in the old twenty-monthly-number ‘green-leaved’ format, but changed plans when Charles Lever’s A Day’s Ride, which followed The Woman in White, failed to hold readers’ interest and caused a perceptible drop in the circulation figures. Dickens assured Forster that “The property of All the Year Round’ was “far too valuable, in every way, to be much endangered” by this development (Forster, 733); nevertheless he was determined to take no risks and so ‘struck in’ with his new story, Great Expectations, the second of his novels to be written wholly in the first person, now replanned as a weekly serial. The circulation figures promptly recovered and in this chance way (at least, as regards its format) there came into being the story that for many critics (and for many ‘common readers’ too) represents the very highest reach of Dickens’s art as a novelist—even with the revised ending that Bulwer Lytton persuaded him to write in order to avoid too starkly sad a conclusion to this masterfully structured and brilliantly written story of money, class, sex, and obsessive mental states with, for the first time ever in Dickens’s major fiction, a protagonist who is unambiguously working-class. The novel was published in three volumes unillustrated, Dickens probably recognizing that Browne’s style had not really kept pace with the development of his own novelistic art, as was evidenced by the feebleness of the illustrations Browne supplied for the volume edition of A Tale of Two Cities.

Featured image: Old Books by jarmoluk. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post All the Year Round, A Tale of Two Cities, and Great Expectations, 1859–1861 appeared first on OUPblog.

The Urgenda decision: balanced constitutionalism in the face of climate change?

Over the coming months and years, much will undoubtedly be written about Urgenda v Netherlands, the decision by a District Court in the Hague ordering the Dutch Government to “limit or have limited” national greenhouse gas emissions by at least 25% by 2020 compared to the level emitted in 1990. A full analysis of the decision is due to appear in the Journal of Environmental Law before the end of the year, but given the myriad of legal issues thrown up by the case, it deserves the close and immediate attention of a wide community of scholars and practitioners.

In brief, the Court found that the State was in breach of its duty of care to Dutch society by failing to take sufficient mitigation measures to prevent dangerous climate change. Up until 2010, the Netherlands had a national target for reducing emissions by 30% by 2020 compared to 1990 levels. The government continued to accept that national reductions of 25-40% by 2020 were needed in order to effectively support the global aim of preventing temperatures rising above 2°C; however, the present mitigation path would only achieve 17%. At this time, the government did not attempt to argue that the scientific consensus had changed or that the original target was economically impossible. Instead, it submitted that the State had no legal obligation to take the more onerous mitigation path, and that allowing any part of the claim would intrude upon the State’s political discretion and interfere with the “separation of powers.”

Urgenda’s claim was based upon a number of arguments. However, the Court found that, as an NGO, Urgenda could not claim a breach of any constitutionally enumerated human rights nor could it rely upon the international “no harm” (Trail Smelter Arbitration) principle. A claim based on “hazardous state negligence” was actionable though. The Court considered all relevant constitutional rights and State treaty obligations, along with a host of other “soft law” and official information (including Ministerial letters, policy documents, decisions of the Kyoto Protocol COPs, the Netherlands commitments under the Doha Amendment, and so on) in order to create a framework first to ascertain the minimum standard of care required by the State and second, to establish the parameters of the State’s discretion. A reduction of 25% reflected the minimum standard of care necessary.

The decision is fascinating due to the way the Court dismissed excuses for avoiding unilateral state action, ones that have been part of the climate change discourse for so many years. The fact that emissions were caused by third parties was irrelevant; the government had the sovereign power to control emissions—i.e. “systemic responsibility”—within its territory. The comparatively minor contribution of the Netherlands to global emissions was inconsequential and the “but for” test, inapplicable. In other words, “any anthropogenic greenhouse gas emission, no matter how minor, contributes to an increase of CO2 levels in the atmosphere and is therefore to hazardous climate change. Emission reduction therefore concerns both a joint and individual responsibility of the signatories to the UN Climate Change Convention.” There was no evidence to support contentions of “carbon leakage.” Any “waterbed effect” in the EU ETS would be minor, and relying predominantly on adaptation created too much uncertainty and was not cost-effective. Fundamentally, “prevention was better than cure.”

Just this brief explanation of the case suggests many issues for exploration. Environmental lawyers may see a crystallisation of the non-regression principle. International and tort lawyers will want to examine the use of “soft law” as informing duties and standards of care for tortious liability. But the case is particularly interesting for public lawyers and political scientists concerned with the relationship between the branches of government.

The Dutch Court explained that its role was simply to review “lawfulness,” but their decision might be perceived as suggesting something more than that—an example of a court overstepping constitutional boundaries. The Court was acutely aware of this possibility. Under a sub-heading entitled “The Separation of Powers,” the Court explained why the decision did not qualify as something beyond constitutional remit. Dutch law does not establish a “full” separation of state powers, rather there is a “balance” within the constitution; citizens require legal protection from the State, and in being tasked with adjudicating over those disputes, the judiciary has “democratic legitimacy.” Further, the Court cannot refuse to decide matters within its jurisdiction simply because there may be political ramifications. Interestingly, the polycentric nature of the debate is a difficulty that the Court did not fully address, other than stating that, as the Court did “not have a clear picture of the magnitude and meaning of … [all] consequences,” there was a need for some restraint in what the Court should order.

The Court alluded to a general difficulty in correctly confining the judicial role in cases of alleged state negligence where the issues of “should citizens be protected” (i.e. is there a duty and is it being flouted) and “how to achieve that protection” are conflated. However, where the issues can be spliced and a minimum standard of protection can be reduced to quantifiable terms (in this case, the percentage reduction) from how that reduction is achieved (the policy issue), then it appears permissible for the courts to establish that standard. In doing so, they will remain within the correct confines of their role, protecting rights rather than creating policy.

Urgenda follows closely on the heels of ClientEarth, R (on the application of) v Secretary of State for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs [2015] UKSC 28 (29 April 2015), a case in which the UK Supreme Court ordered the UK government to comply with the nitrogen dioxide limits provided for in the EU Air Quality Directive. Nitrogen dioxide is toxic and the direct cause of multiple deaths annually, but it is also relevant to the climate change problem; it is an indirect greenhouse gas (unregulated by the Kyoto Protocol) and created predominantly by burning fossil fuels. In my own jurisdiction of New Zealand, the Chief Justice has issued several powerfully worded judgments in climate change-related cases and recently called (extra-judicially) for freedom “from such conceptual shackles as the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty,” a desire “to think less barrenly about … the ‘law-state,’’’ and a framework provided by new constitutional map-makers that will protect things of societal value threatened by “not [having] a shared sense of what is important.”

None of this, I believe, portends a constitutional revolution. Nor perhaps is it evidence of an evolutionary continuum, where the courts cement a greater constitutional role for themselves over time. It may, however, be evidence of the courts “taking up the slack,” shifting, and changing position as the context demands in order to restore the constitutional equilibrium, with the prospect of withdrawal when the need passes. Climate change is providing that context.

Lord Woolf has referred to a time “unthinkable” when courts may have to take responsibility for re-balancing the constitution. What is most interesting to me about the Urgenda case is the idea that this might be a time “unthinkable”: a time when the political branch is unwilling or unable to protect fundamental rights; a time of environmental destruction on such a massive scale that, as the Dutch Court put it, we are facing “catastrophic consequences”; an awareness on the part of the Court that “the other” has abdicated its responsibility; and the realization that it is time to take up the slack. Are the branches of the Dutch State shifting, re-adjusting within constitutional parameters, acknowledging and acting upon their relative strengths and weaknesses in order to cope with the “unthinkable?”

What the Netherlands does now is critical. Even Goldsworthy admits that the “courts can initiate change, provided that the other branches of government are willing to accept it.” Will the Dutch government reject the Urgenda decision and appeal, re-claiming sole responsibility for the “wicked problem” of climate change? Or will it acquiesce and by corollary accept, perhaps even welcome, the constitutional re-balancing?

Image Credit: “Prinses Amalia windmolenpark 4″ by Ad Meskens. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Urgenda decision: balanced constitutionalism in the face of climate change? appeared first on OUPblog.

The future of development – aid and beyond

Just over a year ago, in March 2014, UNU-WIDER published a Report called: ‘What do we know about aid as we approach 2015?’ It notes the many successes of aid in a variety of sectors, and that in order to remain relevant and effective beyond 2015 it must learn to deal with, amongst other things, the new geography of poverty; the challenge of fragile states; and the provision of global public goods, including environmental protection.

The questions raised in the UNU-WIDER Report remain highly relevant, and the second half of 2015 provides an unprecedented opportunity to address them. Before turning to that opportunity, though, it is worth recalling that the last 15 years have seen extraordinary progress against the objectives set out in the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The proportion of people living in absolute poverty has been halved; far more children (girls as well as boys, and the UNU-WIDER rightly emphasises the gender dimension of development) are attending primary school, and far fewer of them are dying before they reach their fifth birthday. Undoubtedly rapid economic growth in China and India has been a major factor in this progress, but aid has also played a significant role.

In Africa as well as Asia, many countries are making significant progress. Many of them are looking to move to middle-income status over the coming decade or so, and will as a consequence become less dependent on the large-scale transfer of concessional resources. Bilateral financial aid will in practice focus on a decreasing number of fragile states and countries emerging from conflict, in which the conditions for transformational change do not exist and which lack human and institutional capacity.So – as the UNU-WIDER Report notes – aid will have an important continuing role in those countries both in addressing issues of governance and capacity-building, but also providing direct support to the social sectors.

Marines and Pakistani Soldiers unload supplies by United States Marine Corps Official Page. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

Marines and Pakistani Soldiers unload supplies by United States Marine Corps Official Page. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.At the moment, the majority of poor people live in middle income countries; there are more poor people in India alone than in the whole of Africa. That will change over the coming decade and a half, and by 2030 – recognising the aspiration to eliminate absolute poverty by that date – deep poverty will be essentially a problem of fragile states, which will be found mainly in Africa. Whilst other flows such as remittances and foreign direct investment will as a general rule become more important, and in the overall scheme of things aid will become less important, aid will remain crucial for those poor, fragile states.

Aid is not just about supporting individual countries, and the international community will have to cooperate increasingly closely in supporting ‘global public goods’. Addressing the challenges of climate change (both mitigation and adaptation) is perhaps the most obvious example, but others include the need to address issues of environmental pollution; or preventing the loss of bio-diversity; or working together to combat deadly diseases which, as the recent outbreak of ebola in West Africa has reminded us, are no respecter on national boundaries.

The environmental problems in particular have been created – or at least exacerbated – by the more developed countries, and the negative effects have been felt most strongly by the less-developed countries. It will take very significant resources to address them, and there are strong grounds – both moral and self-interest – for the better-off countries to provide the bulk of those resources.We ignore the existential threats to our Planet – and to humankind – at our peril.

Whatever the future of aid, and the crucial role of continuing concessional financing for a number of countries, it is important also to address other policies which impact directly and negatively on developing countries. It is important to have a ‘whole of Government approach’ to development, described by some as ‘policy coherence for development’. This includes, for example, looking at the full range of issues such as the cost associated with transferring remittances; the impact of agricultural subsidies and rules of origin; the application of intellectual property rights etc – all of which can have a significant negative impact on developing countries.

The second half of 2015 provides an extraordinary opportunity to address these and other issues. There are (at least!) four very significant meetings taking place, beginning with the ‘Financing for Development’ Conference taking place in Addis Ababa in the second half of July, which will give some indication of the total resources from all sources (aid; remittances; private sector investment) available to support the development aspirations of less-developed countries. Second, there will be a Conference in New York in the second half of September to decide on a new set of ‘Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs) to replace the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) which expire at the end of 2015.

The broad shape of the SDGs is already clear – a comprehensive set of 17 Goals, the over-arching one of which is to see the elimination of absolute poverty by 2030.The SDGs are based on three key pillars – economic growth; equity (‘leave no-one behind’); and sustainability (look after the Planet, on which succeeding generations will depend). The SDGs reflect a comprehensive consultation process, and it is interesting that employment and job-creation were noted as a key priority, after health and education, by respondents in that process – an area also flagged by the UNU-WIDER Report as being of crucial importance.

There are then two major Conferences in December. The first of these, in Paris, is on the environment, thus linking very strongly to the sustainability pillar of the SDGs. It is potentially an event which will attract more Heads of State and Government than any previous Conference – so we must hope they will not wish to leave without a significant agreement. And finally there will be a meeting of Ministers of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in Nairobi, also in December, to try to make progress on a range of trade issues which have made little progress for many years but which have the potential to stimulate world trade to the benefit of better off and poorer countries alike; trade, like peace and security, is in many ways a global public good.

So a good many of the issues raised in the UNU-WIDER Report of March 2014 not only remain relevant, but will come into sharper focus as we move into the second half of 2015.The remainder of this year will effectively establish the framework for international development for the coming fifteen years. We had better get it right.

This post originally appeared on UNI-WIDER, 29 May 2015.

The post The future of development – aid and beyond appeared first on OUPblog.

July 21, 2015

Ten years of social media at OUP [infographic]

The creation of the OUPblog in 2005 marked our first foray into the world of social media. A decade later, more than 8,000 articles have been published and we’ve evolved into one of the most widely-read academic blogs today, offering daily commentary from authors, staff, and friends of Oxford University Press on everything from data privacy to the science of love. While eagerly anticipating our next chapter, we would be remiss in not taking a moment to reflect on our own story, one filled with inspired beginnings, incredible milestones, and generous support from our readers. From the launch of our Facebook to the day we hit 100,000 Tumblr followers, take a moment to explore ten years of social media at OUP.

Download a JPEG or PDF version.

Image Credit: “Social Media Bookmark-Bookmark” by Christine. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ten years of social media at OUP [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

What Happened, Miss Simone? : Liz Garbus’ documentary in review

Award-winning director Liz Garbus has made a compelling, if sometimes troubling, documentary about a compelling and troubling figure—the talented and increasingly iconic performer, Nina Simone. The title, What Happened, Miss Simone?, comes from an essay that Maya Angelou wrote in 1970. In the opening seconds of the film, excerpts from Angelou’s words appear: “Miss Simone, you are idolized, even loved, by millions now. But what happened, Miss Simone?”

That passage and the opening segment of What Happened—which juxtaposes Simone’s strange behavior at a concert at the Montreux Jazz Festival to “Eight Years Earlier” and an interview and vibrant performance she gave in 1968—suggest that this may be a “typical” celebrity biopic documenting the ascent and descent of a gifted yet tortured star. However, at its best, What Happened, Miss Simone? asks questions that prove to be both much more important and interesting. “What happened” is the frame through which Garbus explores how a classically-trained pianist produced an enormous catalogue of music, from love songs to political anthems, Beatles to Bob Dylan, folk to jazz. The film considers why Simone, who began her career in the late 1950s to sing popular music in her unforgettable baritone voice and who was “not allowed to mention anything racial” in her house growing up, gave 1960s black activists some of the most politically engaged music that the movement had. Garbus also asks what happened when Simone’s genius and commitment to black freedom converged with decades of mental illness. What happened, in other words, when a black woman dared to question white supremacy, envisioned freedom, sought love and sexual pleasure, and wanted both commercial success and political commitment at a moment when the United States could not accommodate these desires and demands. These are the questions that animate What Happened, Miss Simone? and make it a mesmerizing portrait of a figure who, precisely because she refused to fit herself into conventional categories, for too long fell outside of the stories we tell about this era.

Garbus allows Simone to tell her own story as much as possible and relies on performances as one important way to do so. We see 26-year-old Simone in 1959 on Hugh Hefner’s (short-lived) television series, Playboy Penthouse, where she performed her first big hit, “I Loves You Porgy,” alongside Hefner and the all-white patrons of his television penthouse. In 1963, Simone realized a lifelong dream when she gave a concert at Carnegie Hall (though she bemoaned the fact that she was not performing Bach). Two years later, Simone performed the incendiary “Mississippi Goddam” on a makeshift stage for 40,000 protesters after the Selma to Montgomery march. The film concludes with Simone’s performance of “My Baby Just Cares for Me” in the early 1990s, after she’d been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and was taking the correct medication; with the help of friends and Chanel—which used the song in an advertising campaign—Simone made a comeback after years of mental illness and relative obscurity.

“Nina Simone, 1965″ by Dutch National Archives. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Nina Simone, 1965″ by Dutch National Archives. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Garbus intercuts the many priceless performances with still photos, Simone’s voice from interviews, and scans of handwritten letters and diary entries. The film also refreshingly eschews the “talking heads” approach in which “experts” tell us what to think from their positions of authority. Instead, most of the other voices and “characters” in What Happened are those who lived alongside Simone through these years. This device often works beautifully. Early in the film we “meet” Al Schackman, the guitarist who started playing with Simone in 1957. As he talks about their “telepathic relationship” on stage—she never looked at him or told him what song or what key she would play in before their first show—we see them performing together and hear his explanation of how “before you knew it we were just weaving in and out.” As her singing voice crescendos, he describes her ability to make any piece her own, “morphing” it into “her experience.” We then get her perspective: “I was interested in conveying an emotional message… so sometimes I sound like gravel and sometimes I sound like coffee and cream.” In another section, we see Simone’s performance of “Ain’t Got No, I Got Life” (from the musical Hair) alongside her affirmations about the importance of black history and black identity. This clip showcases Simone’s ability to cover other music, anticipating, perhaps, the mash-ups of today; taken together, the interview and performance transform these melodies associated with a white-dominated counterculture into a ballad for black power.

But the effort to capture all the possible layers of “what happened” to Nina Simone has trade-offs. Quite simply, What Happened is very packed. It’s not always clear when different events took place. Garbus seldom includes dates to accompany Simone’s voice-overs, nor do we know who is asking the interview questions that we hear at some points.

Even more, Garbus’ method confers a great deal of authority on her non-expert narrators. The role that Simone’s ex-husband, Andy Stroud, plays in What Happened is particularly problematic. On the one hand, it is a great gift that Stroud—a former New York City police detective who became Simone’s manager after their marriage and who has long avoided public attention—speaks so freely. But the casualness with which he discusses his physical and emotional abuse of Simone is unnerving to say the least, and at times he equates her emotional illness with her radical politics. What are we to make of his assertions that he was always pushing for commercial success but that Simone got “sidetracked” by politics—even though, he says derisively, she still wanted nice things, which is why he “promised her that she was going to be a rich black bitch.”

Their daughter, Lisa Simone Kelley (executive producer and herself subject to abuse from Simone in the 1970s), is integral to What Happened and implicitly props her father up when she acknowledges his abuse but declares that her parents “were both nuts” and questions her mother for staying in an abusive relationship. Stroud’s descriptions of escorting Simone to the piano when she was struggling, taking her to psychiatrists when she was unwell, and listening to how “extreme terrorist militants” were “influencing her” become a kind of evidence that he was a concerned husband who had her best interests and career in mind; this narrative focus downplays the abuse that accompanied Stroud’s apparent concern.

Garbus may be asking her viewers to judge these “witnesses” as we make sense of the nexus of genius and mental illness in Nina Simone—to listen, weigh in, assess, and push back, rather than take everything that everyone says at face value. But it’s not a given that everyone will do that and sections of the film depict an abusive relationship in ways that pathologize Simone and her politics. This is not to say that What Happened does not offer other perspectives; Attalah Shabbaz, for example, Malcolm X’s daughter, notes that participating in black activism in the 1960s “rendered chaos in any individual’s [life]. People sacrificed sanity, well-being, life… Nina Simone was a free spirit in an era that didn’t really appreciate a woman’s genius. So what does that do to a family?” But this insight contrasts with the competing notion that Simone was emotionally unstable and therefore militant in pursuit of black freedom.

Still, with its beautiful weaving together of the professional, personal, and political dimensions of Simone’s life and its inspiring recovery of voices, What Happened, Miss Simone? will surely be the definitive source against which other accounts of Simone’s life are measured. Certainly, it is a researcher’s dream come true. Garbus has unearthed a treasure trove of riveting material; one can only hope that the DVD includes “extras”—the clips from the cutting room floor that didn’t make it in. Ultimately, the lurking question of What Happened, Miss Simone? is filled with devastating poignancy. What happened that the stars aligned so that Simone’s talents could be a voice that inspired and continues to inspire? What happened that she could be such a cogent voice for change and radical politics, well before “black power” was a phrase that people used? What happened that a black woman, who suffered so very much in her own life, could affirm black female power and racial liberation in the myriad and unforgettable ways that she did? We may not have answers, but we can be grateful that Nina Simone continues to inspire, educate, and yes, entertain.

Image Credit: “nina4″ by GLinG GLoMo. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What Happened, Miss Simone? : Liz Garbus’ documentary in review appeared first on OUPblog.

Policing – the new graduate career path?

Launched in 2014 as a two-year leadership development programme, Police Now has a mission to transform communities, reduce crime, and increase the public’s confidence in policing. By recruiting outstanding and diverse individuals, it aims to develop leaders in society and on the policing frontline.

The links between crime, deprivation, and opportunity are widely documented. The fact that you live in a more deprived area shouldn’t increase the likelihood of you fearing, suffering, or getting involved in crime. Unfortunately, there is a body of evidence which suggests that all of these hold true. Our most disadvantaged communities experience twice the rate of property crime and four times the rate of personal crime, compared to those areas in the next worst decile for crime.

The proximity of police officers to our communities’ most entrenched social issues means that we are well placed to address them at the root, as well as responding to their consequences. The Police Now programme has a vision of our society where the links between crime and deprivation are broken.

As anyone who has experienced the very best of the British policing profession could attest, high quality policing can contribute to the transformation of a community, laying the foundations for flourishing neighbourhoods, and the lives of those who live there. It is Police Now’s overarching aim to contribute to the creation and development of safe, confident communities in which people can thrive. Our ‘Theory of Change’ is that by attracting Britain’s best graduates to a policing career, training them intensively as community leaders, and then deploying them as police officers in those communities who need us most, we can have a disproportionate impact.

Police Now is designed explicitly as a leadership programme – bringing the brightest into policing and placing participants into demanding roles where they can develop as leaders within a single local community over the two years of the programme. Participants will be trained as highly effective police officers, but will also be expected to develop a clear vision for local change – co-created with their community – and to take a collaborative and strategic approach to pursuing that vision, looking beyond the parameters of their pure policing role.

David Spencer, Director of Police Now © Police Now

David Spencer, Director of Police Now © Police NowOur initial research with final year university students revealed perceptions of policing which – while not perhaps surprising – provided us with an understanding as to why it has not traditionally been seen as an obvious career route for large numbers of the UK’s best graduates. Some 38% of the final year students responding to our initial surveys said that they “did not go to university to join the police”. Some of the comments included that policing would be “boring work” and not “intellectually challenging enough”. As anyone who has had even the shortest of policing careers will attest, the work is rarely boring and leadership as a police officer in a deprived community is challenging in every way – including intellectually. Only 5% of our respondents told us that they had even considered applying for a policing career.

Police Now aims to demonstrate that the policing profession and the programme itself are careers that the very best of Britain’s graduates should consider. The challenges and opportunities inherent in a policing career have the potential to fit well into graduate expectations. Graduates tell us that the most important motivations for them in choosing a first career are leadership opportunities, responsibility, challenge, excitement, variation, and altruism – all integral to policing.

At the end of the two year development programme, participants will either continue in a policing role or will leave the profession taking with them lessons of leadership and a passion for transforming deprived communities. We as a profession need to better articulate the work we do, how we do it and why. In years to come having a cohort of Police Now ambassadors working in business, politics, policy-making, journalism, and other professions will support us in that mission. It cannot be right that given the importance of policing within society the House of Commons has 90 former Special Advisors, 100 lawyers, but not a single former full-time police officer.

Established only last year, Police Now has already made great strides forward. We have attracted impressive graduates to join the profession (over 1200 applicants for our first cohort of 70 places, with 56% of applicants saying they would not have applied for a policing career if it weren’t for Police Now). We have developed a training programme unlike any other in policing, and recently described by a senior policing colleague as “the best planned and designed training programme I’ve seen in ten years”. Now we need to deliver on making a difference in the communities who need us most in the years to come – contributing to transforming them and the police service that serves them.

Featured image: Officers on beat by West Midlands Police. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Policing – the new graduate career path? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers