Oxford University Press's Blog, page 635

August 1, 2015

Digital dating dynamics: age differences in online dating profiles

Online dating is becoming an increasingly prevalent context to begin a romantic relationship. Nearly 40% of single adults have used online dating websites or apps. Furthermore, the world of online dating is no longer confined to young adults; reports suggest adults aged 60 and older are the largest growing segment of online daters. Obviously, adults using these websites are motivated to find a partner, but we know little about why they want to date or how adults of different ages present themselves to potential partners. In other words, do older and younger adults have different motivations to date? If so, how might their online dating profiles reflect these different motivations?

I explored these questions with my co-author Karen Fingerman in our recent study examining the profiles that older and younger adults posted via online dating websites. In the largest systematic examination of online profiles to date, we gathered 4000 online dating profiles from men and women across the United States. We sampled profiles evenly by gender and from four age groups (18 to 29; 30 to 49; 50 to 64; and 65 or over). The final sample ranged in age from 18 to 95.

To get a descriptive picture of the profile content, we looked at the most commonly used words across dating profiles. We noticed a high degree of similarity in what adults wrote about in their profiles, perhaps due to the highly scripted questions that elicit dating profiles. The word-cloud below shows the 20 most commonly used words across the entire sample, with each word scaled in size relative to its frequency. Generally, profiles reflected a common motivation to date; people wrote about looking for love and someone to enjoy life with.

Most common words across all online dating profiles

Image created by Eden M. Davis. Used with permission via

Journal of Gerontology, Series B

.

Image created by Eden M. Davis. Used with permission via

Journal of Gerontology, Series B

.Yet we also found that older and younger adults presented themselves differently to potential dating partners. Below are two word-clouds that show the next 30 most common words, now broken down into the youngest and oldest age groups.

Common words for young adults

Image created by Eden M. Davis. Used with permission via

Journal of Gerontology, Series B

.

Image created by Eden M. Davis. Used with permission via

Journal of Gerontology, Series B

.Common words for older adults

Image created by Eden M. Davis. Used with permission via

Journal of Gerontology, Series B

.

Image created by Eden M. Davis. Used with permission via

Journal of Gerontology, Series B

.To explore age differences systematically, we used a software program called Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, or LIWC. The software calculates the proportion of words in a text sample that fit specific categories. The LIWC software showed that adults of different ages use different language in their dating profiles. Notably, older adults used more positive emotion words such as “sweet,” “kind,” and “nice,” more first person plural pronouns such as “we,” “us,” and “our,” and more words in the ‘friends’ category. These findings suggest that when they present themselves to potential partners, older adults focus on positivity and connectedness to others. Not surprisingly, older adults were also more likely to use health-related words such as “ache,” “doctor,” and “exercise.”

Younger adults, on the other hand, seemed to focus on enhancing themselves in their dating profiles. Younger adults used greater proportions of first-person singular pronouns “I,” “me,” and “mine,” as well as greater proportions of words in categories of ‘work’ and ‘achievement.’

Older and younger adults were equally likely to use words that refer to attractiveness and sexuality, suggesting that adults of all ages share a desire for a physical connection with their dating partners.

While this study gave us a glimpse into the online dating lives of these adults, it did not address how things turned out, such as the number of messages the writer received from potential partners, how many dates they went on, or whether they formed a relationship. Yet, other research suggests that online daters are more likely to respond to people who send messages with fewer self-references. Additionally, research shows that displaying strong positive emotions in an online dating message is related to better first impressions and evaluations of the writer. So it appears that older adults may have a bit of an edge over their younger online dating counterparts when it comes to constructing their profiles. But we will have to wait for future studies to determine how profile content is related to actual dating outcomes.

Overall, our research helps to illuminate the motivations people bring to their online dating profiles. Single adults of all ages are looking to find love and a partner to enjoy life with. However, older and younger adults may highlight different motivations in their profiles, with younger adults focusing on themselves and older adults emphasizing positivity and connections to others.

Image Credit: Photo by Stevepb. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Digital dating dynamics: age differences in online dating profiles appeared first on OUPblog.

Who’s in charge anyway?

Influenced by the discoveries of cognitive science, many of us will now accept that much of our mental life is unconscious. There are subliminal perceptions, implicit attitudes and beliefs, inferences that take place tacitly outside of our awareness, and much more. But we are apt to identify ourselves with our conscious minds. People who take the implicit attitudes test, for example, are often horrified to discover that they harbor racial prejudices or gender biases they were unaware of. If they accept the science, they are forced to believe that these attitudes are in some sense part of themselves. But they are an unwelcome part, an alien part, something to be got rid of if possible.

We are also apt to think that it is our conscious minds that are in control, much of the time; or at any rate, that our conscious minds are capable of taking control. When we pause to reflect, and act on our reflections, it is our conscious thoughts — our conscious beliefs, goals, and decisions — that get to control what we do. Or so we think. But this sense of self-control is an illusion. In reality our conscious minds are controlled and manipulated by unconscious processes.

‘Untitled’, 19th July 2015, by Rachael Carruthers. Image used with permission.

‘Untitled’, 19th July 2015, by Rachael Carruthers. Image used with permission.The reason is simple. Beliefs, goals, and decisions are never conscious. Rather, these states pull the strings in the background, selecting and manipulating the sensory-based contents that do figure in consciousness. Our conscious reflections are exclusively composed of sensory-like events such as visual images, episodic memories, inner speech, and so on. But because we swiftly and unconsciously interpret these events as manifestations of corresponding beliefs, goals, or decisions, we have the impression that we are consciously aware of such thoughts. You can, as it were, hear yourself as deciding to do something when the appropriate sensory-like episode — “I’ll do it now”, say — figures in consciousness. But your access to the underlying decision is just as indirect and interpretive as is your access to someone else’s decision when they say such a thing out loud. In our own case, however, we are under the illusion that the decision is a conscious one.

What are my grounds for making these surprising claims? In short, the science of working memory. This is the sort of memory that is involved when one needs to keep in mind an image or a phone number to report or write down a while later. It is also the short-term memory system in which episodes of inner speech take place. Indeed, many in cognitive science think that working memory is the system in which all conscious episodes play out. It is sometimes described as a “global workspace” because its contents are simultaneously available to many different faculties of the mind (for forming explicit memories, for drawing inferences, for guiding reasoning and planning, and for reporting in speech). But working memory is a sensory-based system. It uses so-called “top-down attention” to activate and sustain imagistic representations in conscious form. There is no place within it for purely abstract non-sensory states such as beliefs, goals, or decisions.

Consider a particular example. You are studying for a French class, trying to learn the meanings of the designated words. But all the while images and memories are being sparked unconsciously by aspects of what you read, see, and hear. These are initially unconscious, but are evaluated by the bottom-up attentional network for relevance to current goals and values. These ideas then compete for top-down attention to enter working memory and become conscious. At a certain point you take a decision (unconsciously) to switch attention from the French words to an image of yourself on a sandy beach, with palm trees, blue sky, and green sea. Before you know it you are drifting in fantasy, while your goal of learning vocabulary struggles to regain control of attention. At a certain point it wins the competition and you snap back, tell yourself off for time-wasting, and focus your attention on the textbook again.

In this manner our conscious minds are continually under the control of our unconscious thoughts. We decide what to pay attention to, what to remember, what to think of, what to imagine, and what sentences to rehearse in inner speech. There is control, of course, and it is a form of self-control. But is not control by a conscious self. Rather, what we take to be the conscious self is a puppet manipulated by our unconscious goals, beliefs, and decisions. Who’s in charge? Well, we are. But the “we” who are in charge are not the conscious selves we take ourselves to be, but rather a set of unconsciously operating mental states. Consciousness does make a difference. Indeed, it is vital to the overall functioning of the human mind. But a controlling conscious self is an illusion.

Header image credit: “Museo Internazionale delle Marionette”, by Leonardo Pilara. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Who’s in charge anyway? appeared first on OUPblog.

July 31, 2015

Why do we prefer eating sweet things?

Is the “sweet tooth” real? The answer may surprise you. Humans vary in their preference towards sweet things; some of us dislike them while others may as well be addicted. But for those of us who have a tendency towards sweetness, why do we like what we like? We are hardly limited by type; our preference spans across both food and drinks, including candy, desserts, fruits, sodas, and even alcoholic beverages. In this short (but sweet) animated video, we take a quick look at the science behind our preference for sweetness.

Begin video transcript:

Our sense of taste is unlike any other. Scientific data supports the existence of the sweet tooth in perhaps half of all humans. We’re born with established likes and dislikes. Craving for sweet foods is partly hereditary.

The enjoyment you feel from eating something sweet is facilitated by the same morphine-like biochemical systems in the brain that are thought to be the basis for all highly-rewarding activities.

From an evolutionary standpoint, our survival depends on our ability to take in energy from our diet. One of the major sources of energy is carbohydrates, which include sugars. In order to maximize our energy intake, our preference for food generally rises with its sweetness intensity.

Humans are not alone; all plant-consuming mammals demonstrate a preference for sweetness. The only mammal species that do not respond positively to sweetness are obligate carnivores, such as cats, that are not reliant on plant-derived carbohydrates. Science has shown why sweet tastes are rewarding.

Expand your knowledge of all things sweet with The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets.

Headline image credit: Donut. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Why do we prefer eating sweet things? appeared first on OUPblog.

Does homeownership strengthen or loosen the marriage knot?

Picture a snapshot of the American Dream. Chances are, this calls to mind a house and a family. Perhaps the most enduring institutions in American society, homeownership and marriage, have shaped the economic fortunes of families in the United States since the country’s origin. So what is the relationship between the two? New research suggests that homeownership, as compared to renting, may significantly affect decisions to marry and divorce.

Are single homeowners less likely to marry than single renters? What role does homeownership play in strengthening marriage and reducing the risk of divorce? In a study recently published in Social Work Research, we sought to investigate these questions for a sample of low- to moderate-income (LMI) households, a population that researchers have not previously studied with these questions. Exploring the relationship between homeownership and marriage among this population is important, as evidence suggests that both marriage and homeownership confer social and economic benefits. Policymakers continue to show interest in the relationship between marriage and homeownership through efforts such as the Healthy Marriage Initiative and consistently promote each as poverty-reduction strategies, even as the housing market and social landscape have shifted.

We hypothesized that (1) single homeowners are more likely to delay marriage than single renters and that (2) married homeowners are more likely to delay or avoid divorce than married renters. In framing our hypothesis, we drew upon Becker’s economic theory of marriage. He asserted that the decision to marry is based on gaining resources and dividing household labor and occurs only if benefits outweigh costs. We also drew upon Edwards’s social exchange theory of marriage. He posited that people choose to marry when it’s mutually beneficial and that partners divorce when the benefits of splitting up outweigh the costs of staying together.

Our study sample consisted of LMI homebuyers with mortgages funded through the Community Advantage Program and a comparison group of renters with the same neighborhood and income characteristics. The survey was longitudinal, and we used data collected in five waves between 2004 and 2008. We used propensity score analysis (PSA) to address selection bias, in this case referring to how people who choose to become homeowners may differ from renters in systematic but unobserved ways, and thus potentially bias the statistical analysis. The PSA method enabled us to isolate homeownership’s respective relationships with marriage and divorce.

Houses neighborhood suburbs by Unsplash. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay

Houses neighborhood suburbs by Unsplash. CC0 Public domain via PixabayOur findings suggest that homeownership may anchor people, making them reluctant to undertake major life changes such as marriage or divorce: compared with renters, LMI homeowners were more likely to remain in their relationship status, whether they were married or single. Homeownership may protect some married couples from the risk of divorce: compared with married renters, married homeowners were 60% to 69% less likely to divorce. However, for single homeowners, the odds of getting married were 51% to 55% lower than for single renters.

These findings affirm that the decisions to marry and divorce may have economic dimensions as well as cultural, emotional, and intellectual ones. The decisions are influenced by an approach that seeks to maximize gain and minimize cost. A home is often the single largest asset for homeowners, particularly for LMI homeowners. Thus, single homeowners have less to gain financially through marriage than do renters, and the potential costs from divorce are greater for married homeowners than for married renters.

What about homeownership influences decisions to marry and divorce? Homeownership (1) provides financial value in the form of the home; (2) implies access to other financial resources, such as stable income and investments; and (3) creates social ties such as links to community infrastructure and to social networks. In addition, marriage decisions by single homeowners are likely influenced by whether the potential partner will add value or divide current assets, and divorce decisions by married partners are likely influenced by the possibility that each will lose assets.

So what do our results mean for practice and policy?

For most people, marriage isn’t simply an economic calculation, so it’s important to contextualize these findings in today’s complex social and cultural landscape. However, our findings suggest that assets, including a home, strongly influence decisions to marry and divorce. Our research also affirms other evidence that marriage and homeownership are often coupled; together, they stimulate family and housing stability. Policymakers would do well to devise initiatives that jointly increase opportunities for marriage and homeownership. Also, the finding that single LMI homeowners are less likely to pursue marriage suggests that practitioners and policymakers should pay attention to approaches that enhance economic and familial stability outside of marriage.

Marriage and homeownership will endure in American society and continue to affect both the national economy and the personal economies of American families. Understanding the relationship between marriage and homeownership is key in providing better welfare policies to support disadvantaged families—and in making the American Dream a reality for those families.

The post Does homeownership strengthen or loosen the marriage knot? appeared first on OUPblog.

Death is not the end: The rise and rise of Pierre Bourdieu in US sociology

Pierre Bourdieu would have turned 85 on 1 August 2015. Thirteen years after his death, the French sociologist remains one of the leading social scientists in the world. His work has been translated into dozens of languages (Sapiro & Bustamante 2009), and he is one of the most cited social theorists worldwide, ahead of major thinkers like Jurgen Habermas, Anthony Giddens, or Irving Goffman (Santoro 2008). That Bourdieu is one of the most prominent social theorists will come as no surprise to those accustomed to the academic scene. A more surprising fact, however, is that he is probably the most cited scholar in the social sciences. In a forthcoming paper on the reception of French sociologists in the United States, Andrew Abbott and I show that, at the turn of this decade, he is referenced in more than 100 sociological articles a year. Important authors like Paul Di Maggio or James Coleman are only cited 60 times, while Mark Granovetter has nearly 50 mentions. Bourdieu is also referenced more often than Émile Durkheim, who for a long time epitomized (French) sociology. (These measures are based on a set of 34 journals published in or central to US sociology. As the number of articles has increased (and the number of references even more so) over the last decades, a rigorous analysis would require normalization. As our current approach does not prevent year-by-year comparison between authors, our main interest, we did not normalize the results here.)

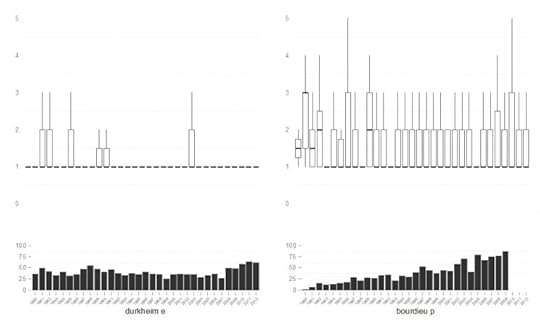

Figure 1: Total number of citations of selected authors

Figure 1: Total number of citations of selected authorsThe son of a postman from the Southwest of France, Bourdieu was far from predestined to become the most influential sociologist of his generation – maybe of the 20th century. Upon arriving at the École Normale Supérieure, the French elite school that was then the pinnacle of academic life, Bourdieu chose philosophy as a major. The curriculum, friendships, and what he saw as the useless posturing of philosophers made him stray from this standard trajectory for aspiring intellectuals at the time. Being drafted into the army had an even stronger influence on this life-course shift. In 1955, Bourdieu was deployed in Algeria, in the midst of the war for liberation. After his military service, Bourdieu remained for several years in Algiers, where he became a lecturer and undertook ethnographic work.

This experience turned the avid reader of philosophy into an empirical researcher. Upon returning in France, his interest expanded to embrace a flurry of objects: from the school system (The Inheritors, 1964) to art lovers and museum-goers (The Love of Art, 1966), from cultural practices (Distinction, 1979) to cultural producers (Homo Academicus, 1984 and The Rules of Art, 1992). His publications cover an impressive variety of topics. From these different sites, he built his theoretical system. The concept of “cultural capital” originates in his studies on education, “habitus” from the analysis of practice in Algeria, “field” from the worlds of art and science, and “symbolic violence” is an attempt to recast the question of the acceptance of power raised during studies on a wide variety of topics including masculine domination and the state.

This diversity of topics influenced the reception of Bourdieu’s work abroad. As has been pointed out (see Sallasz and Zavisca, 2008), it was initially read by different (unrelated) groups. Though it happened fairly early, the reception of his work remained confined to local areas for over two decades. In the United States, this situation changed in the late 1980s following a number of efforts to emphasize the systematic character of Bourdieu’s research. The key initiative among these was the 1992 interview book co-authored by Bourdieu and Loïc Wacquant, Invitation to a Reflexive Sociology. Written in English with a US audience in mind, it aims at presenting Bourdieu’s system to a foreign audience. Our data shows that after publication of this book, his work subsequently gained widespread exposure beyond the limited local fields in which it was already popular. Not only were his concepts now used outside of those fields, but references to his work also increasingly pertained to theoretical aspects rather to empirical ones. Starting in the mid-1990s, Bourdieu was regarded as a general social theorist and read across sub-disciplinary lines—as well as across disciplines.

What will happen next? Although prediction and social science don’t square well, several signs indicate that Bourdieu is currently entering the canon of worldwide sociology. In the United States, our study shows that while the number of references to his work continues to increase, scholars’ level of engagement with the text is decreasing. In fact, over the last few years, references to Bourdieu have become more allusive. To measure this change, we hand-coded several hundred references from different periods. The proportion of those extensively citing Bourdieu has decreased steadily since the 2000s. This trait is characteristic of a process of canonization, when an author becomes equated with an idea or a set of ideas (e.g. Foucault and power, Goffman and face-to-face interactions, etc.), and is therefore considered a mandatory reference on the topic. The citation becomes a ritual. In some cases, the author has obviously not read the text in question.

Figure 2a and 2b: References to Durkheim and Bourdieu; Number of citations per article, boxplot (top) and total number of articles (bottom)

Figure 2a and 2b: References to Durkheim and Bourdieu; Number of citations per article, boxplot (top) and total number of articles (bottom)Has Bourdieu become a museum piece? It does not seem so, at least for now. Scholarly interest is still strong and his work is still very much discussed. A good indicator of this is the number of references to an author per article, and comparison with other authors is telling here. Whereas Durkheim is routinely cited but not much debated, and receives an average of one reference per article citing him (fig2a), Bourdieu’s work is still an object of active investment (fig2b). At least 25% of the articles citing Bourdieu make two references to his work, sometimes many more. Bourdieu may well be entering the canon, but his appropriation abroad still fosters debates.

Image credit: “Pierre Bourdieu, painted portrait” by Thierry Ehrmann via Flickr

The post Death is not the end: The rise and rise of Pierre Bourdieu in US sociology appeared first on OUPblog.

Pluto and Charon at last!

This week I’ve been bemusing my friends by quoting Keats’ On first looking into Chapman’s Homer at them:

MUCH have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

….

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

I’ve been breathing that ‘pure serene’ to which Keats refers while experiencing Pluto and its large moon Charon being revealed at close range for the first time. Granted, Pluto is not strictly a planet, but it is a world that has now very much ‘swum into my ken’, and indeed into the ken of anyone who has been watching the news lately. NASA’s New Horizons probe swept past Pluto and its moons at 17 km per second on 14 July. Even from the few close up images yet beamed back we can say that Pluto’s landscape is amazing. Planetary scientists are now, metaphorically, standing beside Cortez, staring at the newly-revealed Pacific, and surmising very wildly indeed. Charon, Pluto’s largest moon, is quite a sight too, and I’m glad that I delayed publication of my forthcoming Very Short Introduction to Moons so that I could include it.

Pluto (2370 km across, and on the left of the opening image) and Charon (1208 km across, on the right) are icy worlds in two respects. First, their surface temperature is only 40-50 degrees above absolute zero. Second, although they are sufficiently dense that there must be rock deep inside, their outer layers are made of ice. So far as we could tell before we got there, Charon’s surface is water-ice mixed with ammonia, whereas Pluto’s reflectance spectrum showed it to be covered by frozen forms of nitrogen, methane and carbon monoxide (all of which count as ‘ice’), with water-ice presumed to be buried deeper. Pluto’s surface gravity (though only about a fifteenth the strength of the Earth’s gravity) is more than twice as strong as Charon’s, so it has been able to hang on to ices that have vaporised and escaped to space from Charon. It even has a very thin atmosphere of mostly nitrogen gas.

That much we knew already. It will take over a year for New Horizons to transmit all its data, but already we can begin to put flesh on those bare bones. Pluto beguiled us during the approach by showing us its ‘heart’, a tract of bright terrain straddling the equator that seems to be a ‘frost’ or ‘snow’ deposit, now named Tombaugh Regio to commemorate Clyde Tombaugh (1906-1997) who discovered Pluto in 1930. The onboard spectrometer showed us that it is mostly carbon monoxide ice. The first clear views of Charon confirmed it to be markedly less red than Pluto, except for an unexpected dark polar cap.

As we got more detailed images, recorded at closer range, we saw hints of giant fracture systems stretching across parts of both globes. It became apparent that although there are impact craters to be seen, they are relatively few in number. This tells us that the surface of both Pluto and Charon cannot date back billions of years to soon after the birth of the Solar System, otherwise they would bear many more impact scars.

So let’s look at the best of the few pictures that are available.

This image above shows Pluto early in the approach, on 11 July. The ‘heart’ is just beginning to rotate into view at the upper left. I include this picture because at the edge of the globe in the 4 o’clock position there is a shadowed fracture system. This had rotated out of view by the time the spacecraft drew near, but it is important evidence of global faulting, similar to that seen on Charon.

This is Charon on 13 July from a range of 466,000 km, with a detailed insert (located by the box) recorded on 14 July at a range of 79,000 km. The global view show is a north-south fracture system almost on the right-hand edge of the disc, and an east-west fracture system curving all the way across the lower part of the disc. The insert is the most detailed view we yet have. Charon had rotated since the global view, so the sunset line had advanced across the terrain. Notable features in the inset include a mountain rising from within a pit near the upper right corner, and several narrow fairly straight or gently arcuate fractures reminiscent of features on the Moon attributed to local extension of the surface where a dyke (a vertical curtain of magma) has been injected into a fracture. It can’t be molten rock on Charon, but it could be the kind of gooey fluid produced by melting a mixture of water and ammonia ice.

This is the face of Pluto seen during closest approach. ‘The Heart’ (Tombaugh Regio) occupies the lower centre of the disk. Impact craters are visible in some places, such as immediately west of Tombaugh Regio, but their overall scarcity points to a generally young age for Pluto’s surface of less than a billion years and only 100 million years in some places. Is the surface ablating away to space so that old craters are erased? Has older surface been buried and recycled during events that create new surface, such as eruption of icy lavas?

This is a high-resolution image of a 300 km wide area immediately southeast of Tombaugh Regio, oriented with north towards the upper left. The mountain peaks, which are about 3 km high, must be made of water-ice, because other ices would be too weak to stand up as such high masses. Note the absence of impact craters (suggesting young age) and the general ruggedness of the high ground (suggesting faulting and fracturing).

This image is a 300km wide region about 300km north of the previous view. This is within the bright icy plains of Tombaugh Regio. The New Horizons team have speculated that the strange patterning that dominates the carbon monoxide ice surface here indicates convection within the ice. I think that is unlikely (because the convecting layer of ice would need to be nearly as thick as the convection cells are wide) and I think we may be seeing a large-scale equivalent of the polygonal patterned ground observed in Earth’s arctic and on parts of Mars as a result of free-thaw processes. If I’m correct, the knobs or harder ice around the edges of some cells will be giant boulders rather than icy ‘bedrock’.

Finally, a similar-sized region to the west of the previous views, at the western edge of Tombaugh Regio. In the east there are peaks of water-ice projecting up through the probably carbon monoxide ice. The dark surface in the west must be much older, because there are many impact craters on it. Craters at the very edge of the bright ice region have patches of ice within them, and there are almost certainly numerous craters completely hidden in the interior of the bright ice deposit where this ice is thicker.

All images in this blog post are public domain via NASA/JHUAPL/SWRI.

The post Pluto and Charon at last! appeared first on OUPblog.

July 30, 2015

Medicare and Medicaid myths: setting the 50-year record straight

Over the past half-century, Medicare and Medicaid have constituted the bedrock of American healthcare, together providing insurance coverage for more than 100 million people. Yet these programs remain controversial: clashes endure between opponents who criticize costly “big government” programs and supporters who see such programs as essential to the nation’s commitment to protect the vulnerable. Not surprisingly, many myths have emerged in the highly politicized debate about these policies. What better time to set the record straight than today on 30 July 2015, the 50th anniversary of both programs?

“Medicaid originated as a welfare program for people in poverty. It remains a program that exclusively benefits the poor.”

It is true that Medicaid, which initially provided matching federal dollars for states to provide medical assistance to people in poverty, was passed as an afterthought in 1965 and has carried the stigma of poorly financed “welfare medicine.” Yet Medicaid has expanded to cover people above the poverty line, as well as children, and has become increasingly a “middle-class entitlement.” The irony of history is that this poor program now covers more people—66 million in 2014—than Medicare, which covers 52 million people.

“Hospitals became desegregated as a result of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, not due to the passing of Medicare and Medicaid.”

The passage of Medicare and Medicaid was integral to the desegregation of medical care in southern states. As health policy expert David Barton Smith points out, the implementation of Medicare in 1966 was deeply intertwined with the implementation of Civil Rights legislation. Segregated hospitals could not receive Medicare funds, and the threat of losing Medicare and Medicaid dollars became a powerful tool for the federal government to end racial segregation in healthcare.

“Doctor Themed Cupcakes” by Clever Cupcakes. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Doctor Themed Cupcakes” by Clever Cupcakes. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.“Over the decades, Democratic presidents and Congresses have championed expansion of these programs, while Republicans have fought to reduce their scope, eligibility, coverage, and costs.”

Ronald Reagan lobbied against Medicare before its passage, stating that the program was a fundamental assault on liberty. As president, he continued to criticize “big government.” But by the end of his presidency, Reagan had accepted an expansion of Medicare through his support for Medicare Catastrophic Insurance. Rhetoric aside, Republican presidents like Richard Nixon also oversaw costly but crucial new benefits, including coverage for people with kidney disease and individuals with permanent disabilities. Similarly, George W. Bush championed Medicare’s expansive prescription drug coverage benefit in 2003, and did so under a Republican Congress. Democratic presidents have also expanded these programs; Bill Clinton established the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in 1997, which supplemented and expanded Medicaid’s commitments, even while Republicans controlled Congress.

“Medicare is more popular than Medicaid and has much stronger political support.”

While it is true that Medicare enjoys slightly greater popularity than Medicaid, numerous polls have shown that both programs remain popular with Americans. According to a January 2013 Kaiser poll, nearly 50% would not support cuts to Medicaid. The program has survived efforts to block grant it, and has grown to provide security for children, families above the poverty line, and—in the wake of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—many “middle-class” Americans.

“Medicare and government programs have done a poor job of containing the rising cost of healthcare as compared to the private sector.”

While this claim makes good politics, it is simply not true. As political scientist Jacob Hacker noted, from the mid-1980s to the 2010s, Medicare outperformed the private sector despite private plans adopting many of Medicare’s payment modalities, including the diagnosis-related groups (DRG) approach to paying hospitals. Economist Uwe Reinhardt observed that the idea of reimbursing hospitals based on diagnostic categories (rather than fee-for-service) constituted a truly revolutionary innovation that was copied by many countries around the world, and eventually even by the private American health insurance system. These kinds of initiatives continue under the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, a new governmental office created by the ACA.

“Only recently have Governors and state legislatures resisted Medicaid expansion under the ACA.”

From the start, many states were slow to adopt Medicaid. By 1969, five years after passage, 12 states hadn’t joined the program, and it wasn’t until 1982 that Arizona became the final state to join. By then, states decried the rising toll of federal healthcare spending on state budgets, but at the same time also recognized the huge economic benefits of these programs for fields like cardiology, nursing homes, and academic health centers. This explains why, although many states vilify the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, some “red states” like Arizona decided in 2013 that the benefits of Medicaid expansion under the ACA were too good to turn down. It remains to be seen whether other red states will follow Arizona’s path.

“Today’s political fractiousness over the ACA and Medicare and Medicaid is unprecedented.”

Political and ideological divisiveness was present at the origins of Medicare and Medicaid and has rarely subsided. In contrast with the ACA—which passed by the slimmest of margins in the 2010 Democratic Congress under a Democratic president—Medicare and Medicaid was passed at a time when President Johnson enjoyed unprecedented liberal Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress following the 1964 election. By their 30th anniversary in 1995, both of these programs were squarely in the bull’s eye of conservative reform efforts. Republicans in control of Congress pushed for converting Medicaid to a block grant program and for the establishment of a Medical Savings Accounts in place of Medicare.

Myths about Medicare and Medicaid persist for the simple reason that they are politically useful, even as Americans continue to grapple with questions of cost, compassion, and the role of government in their lives. But the facts of history are stubborn. Despite the myths and political turmoil, those who support Medicare and Medicaid can take satisfaction in these programs and their underlying moral commitments, having reached the half-century mark.

Image Credit: “Healthcare Costs” by Images Money. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Medicare and Medicaid myths: setting the 50-year record straight appeared first on OUPblog.

Cancer diagnosis response: Being hit by an existential Mack Truck

When I meet with patients newly diagnosed with cancer, they often find it difficult articulate the forbidding experience of being told for the first time they have cancer. All they hear is ‘die’-gnosis and immediately become overwhelmed by that dreadful feeling: “Oh my God, I’m gonna die!” I often try to meet them in that intimate and vulnerable moment of existential shock and disbelief by stating, “It’s like being hit by an existential Mack truck.” Invariably, the answer that follows is “Yes! I didn’t see it coming. It slammed right into me out of nowhere.”

This becomes my point of entry, as both a psycho-oncologist and existential therapist, for patients facing cancer and their ultimate survival or mortality. Too often in existentialism and oncology, incredible emphasis is placed on facing absence: death, disease, dysfunction, disconnection. This focus on absence does not help our patients grapple with the great unknowns of their illness and existence. I’ve found it is far more beneficial to help focus patients’ toward life’s presence: that which fulfills them with meaning and purpose in the face of cancer. It is far more healing to engage in restorative self-care and marinate in meaning than dwell on death through cancer.

When meeting patients for the first time, I’ve already read their medical chart and objective case history, but I invite them to share their own subjective story of cancer. Through this intimate narrative of cancer I’m able to closely track absence (e.g., fears of mortality, physical pain, mental/emotional suffering) that keep them disconnected from life, as well as presence (e.g., who and what they love, life’s work/goals) that keep them vitally involved and connected to life. After their story is shared, I normalize the reception of a scary cancer diagnosis with some basic psycho-education including common responses and terminology. For example, we may experience an ‘existential crisis’ when our everyday existence is thrown into question. As Martin Heidegger identified in his work Being and Time: “We know our existence in its absence.”

Facing one’s potential untimely demise through the diagnosis of cancer—no matter the age or stage—suffuses the body and mind with mortal terror or what Kierkegaard would term dread. This trauma produces a ‘fight or flight response’—a primitive self-protective/preservatory mechanism for a real or perceived existential danger or threat. The body is inherently benevolent and wants to survive at any cost, but the energy, thoughts, and emotions this mechanism produces may be misdirected and difficult to control. Cancer patients must learn how to effectively harness this response and learn to self-regulate in order to mitigate stress or poor decision-making. Relaxation techniques, such as diaphragmatic breathing, in combination with self-examination reduces cortisol stress hormones. This is crucial to free up the body’s immune system to fight cancer. Patients often perk up when provided tools and a veritable roadmap to help them traverse the dark murky terrain of their initial cancer diagnosis.

Much of my initial work with cancer patients is convincing them that they are in charge of choosing their attitude: die of cancer or live in the face of it. We are inculcated to fear the great unknowns of life, that which are beyond our control. It is essential to shift patients from fear-based stances toward life and cancer, toward a care-based curiosity and interest. Viktor Frankl summed this up by suggesting that “when all else is stripped away physically, mentally, emotionally, spiritually, even existentially—we still have as our last vestige of human freedom the ability to choose at any given moment or in any circumstance how we may find meaning in our suffering .” Nietzsche underscores this message: “He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how.”

I shepherd patients toward sourcing self-regulatory and fulfilling presence to assuage existential angst in the face of absence. As an integrative behavioral health consultant, I help patients employ a healthy lifestyle (diet, exercise, restorative self-care) to strengthen their overall body, mind, and spirit to fight cancer. Once patients start actively engaging in life and become involved in meaningful and purposeful activities, they find the inner strength and empowerment to live fully in the face of cancer—come what may.

Feature image credit: Flock of Seagulls (eschipul). Photo by Kreuzschnabel. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Cancer diagnosis response: Being hit by an existential Mack Truck appeared first on OUPblog.

Who will be singing the next Bond song? Who should be?

Now’s the moment to be a fan of the Bond songs. SPECTRE, the new film, comes out this November. That means we’ll hear an official unofficial leak of the title song sometime this summer. Everybody’s been guessing who the singer is. Twitter says it’ll be Sam Smith or Lana Del Rey. Sam Smith says it isn’t him and claims that he “heard Ellie Goulding was going to do it.” The Telegraph wants to know why no one has considered Mumford and Sons (don’t answer that). Even Vegas is paying attention. Who would you put your money on?

For film-music nerds there has always been an added dimension to the announcement of the next Bond title (whether this happened in the end credits of the previous film, or in some big announcement, once the films ran out of Fleming novels to not-really adapt). We now know there will probably be a song called “SPECTRE” by the fall – unless producers decide the title is unsingable and decide to grant dispensation. (Rita Coolidge was spared having to sing a song called “Octopussy,” for which she’s likely pretty grateful.) Many others probably wondered, too: what kind of voice could belt out a word like “SPECTRE” and make it sound convincing, haunting, and appropriately Bond-esque?

Given how well (and successfully) Adele did this for “Skyfall,” there’s more riding on whether “SPECTRE” make sense as a song than there was on previous songs. Surely the Bond-producers feel some of that pressure. There are some recent choices that felt a bit phoned-in (Chris Cornell? Really?). Adele’s “Skyfall” was a big part of that movie’s identity; the expectations of “SPECTRE” will be huge.

So who will it be? We have our considered opinions as nerds who’ve just written a book about the James Bond songs. But luckily you won’t have to rely on our considered opinions. Because bookies have done the same research that we have, and unlike us they’ve got something riding on this. But all they can give you are odds. We’ll explain them. So here is who it will be, who it could be, and who it should be. Ladies and gentlemen, place your bets.

Lana Del Rey

A strong choice. Self-conscious 60s throwback? Check. Orchestral textures without too much of a beat? Check. Breathy chanteuse with a vague sense of menace? You betcha. So why won’t it be her? Lana Del Rey broke an unwritten rule of Bond-songs: don’t write one on spec. There is a long history of artists sending in songs to the Bond-producers hoping to get picked: Johnny Cash wrote a Tex-Mex “Thunderball,” Alice Cooper wrote a “Man with the Golden Gun.” None of them got picked. While Lana Del Rey didn’t come out and say it, her most recent album contained a Bond-song in all-but-name: “Shades of Cool.” Thanks for playing, Lana.

Coldplay

Wait, you say. Coldplay? In 2006 maybe, but now? Well, picking Adele for the last song was a canny move for the Bond-producers, but traditionally the producers were not exactly known for capturing the musical zeitgeist. Usually by the time they got around to signing an artist for their next film, you could bet that that artist was already getting a bit stale. These are fifty-year-olds with the aesthetic sensibilities of a seventy-year-old picking songs for twenty-year-olds – needless to say, it always goes great. Has your mom heard of Coldplay? Of course, at her Pilates class. At the same time, the decision to go with Adele for “Skyfall” was pretty clued in. If it’s a sign the producers are wising up, Coldplay is probably (and mercifully) out.

Florence and the Machine

Specialists in big, orchestral, almost operatic sound, a strong female voice, and moody, often narrative lyrics – Florence and the Machine have the Bond sound even when not making a Bond song. Which may indeed be what might do them in. A lot of Bond acts were counterintuitive picks at the time. At least once we get beyond the stalwarts (Shirley Bassey, Tom Jones, and Dionne Warwick), you’ll often catch yourself thinking: oh shit, XYZ did a Bond-song? It seems like the producers intended that effect. If Florence and the Machine did a Bond song, it would just like the one they did for that one movie with that girl from Twilight. And for that Game of Thrones trailer. And…

Ed Sheeran

A strange choice at first blush, but that has more to do with the way we think of Bond songs than with the way they’ve actually been. We think menace, up-tempo. But there was a period when Bond songs sounded very different, and the question is whether Bond producers remember that time more fondly than we do. Listen to Carly Simon’s “Nobody Does It Better” or Sheena Easton’s “All Time High” and you’ll be shocked that those were Bond songs. Fan boys griped that they lacked respect for the conventions of the genre, but here’s the thing: consumers ate them up. A Sheeran ballad, downtempo and infused with decidedly vanilla sexuality, could tap into that: no Bond fan’s favorite, but a record that sells. At the same time, who the hell still makes film songs hoping to sell records?

Karen O

Five words: Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. The opening sequence to David Fincher’s Stieg Larsson adaptation (also starring Daniel Craig) was a Bond title sequence done way, way better – disturbing, hallucinatory, visceral in all the ways that Bond-sequences haven’t been for decades. And through it all the rip-roaring Karen O-cover of Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant Song.” You bet the producers saw that sequence and thought: we need something like this to open a Bond-film. But you bet the producers also saw the barely-breaking-even box-office receipts for Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. Why bring on Karen O (or Trent Reznor) when they’ve done a quasi-Bond, and it was widely perceived as a flop?

Adele

They wouldn’t go with Adele again, would they? Well, with any other franchise you could bet on that. But when you get a huge hit out of a singer, when that singer’s effort is called “the best since Goldfinger,” and when Goldfinger was sung by an artist who ended up doing three Bond songs? Doesn’t sound so nuts now, does it? The British tabloids say Adele’s the one. But remember: the Bassey songs (“Goldfinger,” “Diamonds are Forever,” and “Moonraker”) were spread out over a fifteen-year period. So even if the producers think Adele is their new Shirley Bassey, expect her to return a film or two from now, but not right away. Not that it wouldn’t be fun to hear Adele wrap her weirdo hybrid Anglo-American pronunciation around the word spectre.

Lady Gaga

There’s precedent for electronica-based Bond songs; that’s the good news. In our professional opinion that precedent, Madonna’s Die Another Day, is one of the all-time greats. The bad news is that many felt different when the song came out. Critics liked it, but Bond fans were livid. So in handicapping Gaga, the question becomes: who gets to decide? At the same time, nostalgia is the Bond song’s go-to mode, and Gaga’s appeal always contained a healthy dose of nostalgia. So Gaga might actually be a more natural fit than Madonna. Plus, Gaga’s recent collaborations with Tony Bennett have moved her closer to the traditional Bond song sound.

Ellie Goulding

Sam Smith (Vegas’s odds-on favorite for the gig) suggested her – and maybe he’s onto something. Adele was the rare singer who can get fifty-year-old Bond nerds and twenty-year-olds to agree on something. But it was probably the twenty-year-olds who pushed the track up the pop charts. If that’s how the producers see it, then why not go with Ellie Goulding? Sure, the electro-sprite will leave behind the fifty-year-olds, and certainly the Bond nerds. But she’ll bring in the kids, and she might even bring them into the theater before they decide to torrent SPECTRE. Ellie Goulding was spotted leaving Abbey Road Studios.

The question of belonging

” Don’t discuss the writer’s life. Never speculate about his intentions.”

Such were the imperatives when writing literary criticism at school and university. The text was an absolute object to be dissected for what it was, with no reference to where it came from. This conferred on the critic the dignity of the scientist. It’s surprising they didn’t ask us to wear white coats.

Meantime, the individual reader was never mentioned. The fact that people disagreed about literary works, or reacted differently to them, need be of no concern. Critics consider the object, not the consequences.

Does this make sense? Did it ever? To emancipate the literary text from the realities of its production and consumption, to talk about what is essentially an act of communication without reflecting on the partners in the exchange?

One problem was the crudeness of the biographical approach as actually practiced by some outside academe, but above all as stigmatized by the professors. “Biographical fallacy” the University of Houston website warns its students: “the belief that one can explicate the meaning of a work of literature by asserting that it is really about events in its author’s life. Biographical critics retreat from the work of literature into the author’s biography to try to find events … which appear similar to features of the work, and then claim the work “represents those events…,” an over-simplified guess about Neo-formalist ‘mimesis.'”

The biographical critic is a phobic simpleton. Who would dream of engaging in such an enterprise?

And yet…

When we read a novel, or better still many novels by the same author, we can’t help but be aware of an authorial presence, a particular cast of mind that, for all their differences, these books share and that readers enter into relation with as they read. This is why literary biographies are so much more popular than literary criticism. Readers want to know more about the mind they have been in touch with. For years I have been looking for a way to give some system and intellectual respectability to a criticism that remains aware of both the author’s life and individual reader responses, an approach that embraces the whole process of writing and reading from conception to consumption.

The place to start, perhaps, is with the reflection that the way an author writes will be in relation to patterns of behaviour in his or her life, will indeed be part of that behaviour, part of the way the writer positions him or herself in the world. The writing and publication of a poem or novel is itself an event in the life, not separate from it, an event that can shift the relationships that constitute the author’s world.

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov at the age of 29 by The Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Anton Pavlovich Chekhov at the age of 29 by The Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.But enough of abstract preliminaries. Let me try to give you Chekhov in a nut, or blog-shell. Excluded from his family between 16 and 19, Chekov got back into the centre of it by writing stories. And pushed out the father who had been the cause of the trouble. Fleeing debts, his authoritarian father had taken the family to Moscow leaving his third child (of six) to sort out his messy affairs in the provincial port of Taganrog. Three years later, Chekhov rejoined his siblings in a damp basement flat and, as it were, wrote them out of there.

Between ages 20 and 28, he published 528 stories using the income to buy his family a big house in the country. He was now head of the household. All his life would be spent with his mother and younger brothers and sister; all his writing would be about belonging and exclusion, freedom and imprisonment. In a relationship, a family, a group, his characters fear exclusion from it, or yearn to be free of it. Free, they find solitude a prison.

In the country Chekov felt bored and headed for Moscow. Company was so desirable. In Moscow he felt overwhelmed and headed straight back to the country. Company was so vulgar. Then he invited friends to the country. Then he built himself a small house near the big house so he could be free of his friends. In his stories the turning point occurs where the desired relationship or desired freedom is perceived as equally imprisoning as the previous state. Or worse.

Chekhov had started writing as a stopgap while he studied to be a doctor. Then he oscillated between the two professions. Medicine put him in touch with life, but life was overwhelming. Chekhov could find no stable position with regard to belonging, groups relationships. The writing simultaneously dramatizes this instability and brings its author a form of safe belonging: his work is hugely popular, but he remains separate from his admirers.

Chekhov says he wants “to be free, nothing else.” But he also wants to be married. He fears marriage: “every intimacy, which at first so agreeably diversifies life … inevitably grows into a regular problem of extreme intricacy.” So he flirts, has affairs. The short story is a flirtation, a brief relationship. The longer a Chekhov story, the more melancholy it becomes. He tries novels but can’t finish them. They are a prison. Now he starts writing plays, which give him a closer contact with actors and public. On the brink of marrying in 1889, Chekhov cuts loose and flees to the penal colony of Sakhalin Island where for three months he interviews 160 prisoners a day, preparing a file card for each and taking notes on forced labour, child prostitution, and floggings. All his life he never stopped recalling that his father beat him. We can think of his 600 plus stories as file cards of prisoners or those who risk imprisonment, in love, in work, in parenthood, in politics. Essentially, writing had become a survival skill, a form of freedom and solitude that nevertheless put him in a gratifying relation with others.

Needless to say, a reader’s reaction will largely depend on where he or she stands in relation to the question of belonging.

Featured image: Books education school literature by Hermann. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The question of belonging appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers