Oxford University Press's Blog, page 637

July 28, 2015

Ethnomusicology’s queer silences

An audible silence lingers in the field and fieldwork of ethnomusicology. Queer subjects and topics have made few appearances in the literature to date. Such paucity isn’t owed to an absence of LGBTQ-identified members and allies; by and large, ethnomusicologists are as fabulous and open-minded as scholars come. So why has queer ethnomusicology arrived late to the party? Queer theory has been around for over two decades. Some might even say that it’s already over, passé, dead. For ethnomusicologists to jump on the wagon now might seem akin to wandering into a club at last call, just as the DJ packs up and everyone else hails taxis home.

So why queer the field of ethnomusicology at this moment?

It’s important to contemplate the lack of queer inquiry in ethnomusicology relative to numerous productive efforts in its sister disciplines (anthropology, history, sociology, and musicology). As Deborah Wong remarks,

“Queering the Pitch: The New Gay and Lesbian Musicology (Brett, Wood, and Thomas 1994) represents an important juncture in musicology but there are no ethnomusicologists in that collection, and in many ways…most ethnomusicologists have still not engaged deeply with sexuality studies or queer theory despite the fact that music is often a key performative means for defining the terms for pleasure and desire.”

Ethnomusicologists have likewise been underrepresented in subsequent collections such as Out in the Field: Reflections of Lesbian and Gay Anthropologists (1996), Out in Theory (2002), and with only a limited presence in Queering the Popular Pitch (2006).

In the early 1990s, queer pursuits in musicology encountered predictable resistance and, in some cases, explicit homophobia. Ethnomusicologists mostly stayed out of the brawl. Maybe it’s because ethnomusicology was in a sense already queer (a disciplinary outsider relative to music history and music theory), and as such, scholars saw little need for explicit articulations of queerness. Maybe ethnomusicologists have harbored anxieties precisely about their queered status in the academy, and have therefore disavowed direct address of queerness in their work for fear of further marginalization. Or maybe the varying challenges, affordances, and pressures of scholars’ disparate field sites have impeded harmonious and ethically sound dialogues about queerness (out of concerns about culturally relative currencies of gender and sexuality).

So what does it mean to queer the field of ethnomusicology?

For starters, consider how artists and musicians do not typically have a singular code of ethics by which they abide; breaking the rules is an essence of artistry. By contrast, fieldworkers across disciplines often need to answer to the codes of institutions, whether it’s the Society of Ethnomusicology, the IRBs of home institutions, or local research clearance. How have such codes bounded ethnographic practice? Could we argue that it’s unethical to normalize fieldwork, something that, by its very nature, may demand spontaneity, improvisation, and possible intervention? How are such codes affecting fieldworkers’ expressions of normalized or non-normative identities? How do we address the boundaries between marked and unmarked deviance (of researchers and informants alike), as well as issues of (dis)ability, aptitude, and value?

Addressing these difficult questions requires collaborative and compassionate efforts. With enough voices chiming in across field sites and disciplinary boundaries, perhaps ethnomusicology’s queer hush will soon give way to a lively chorus of critical debate.

Image credit: Thessaloniki, Greece – June 21, 2014: Participants of the Gay Pride playing drums during the parade in the city of Thessaloniki. Around 10,000 people are estimated to have participated in the parade of the 3rd Gay Pride Thessaloniki. Members of the LGBT protested for their right to diversity in Thessaloniki, Greece. © verve231 via iStock.

The post Ethnomusicology’s queer silences appeared first on OUPblog.

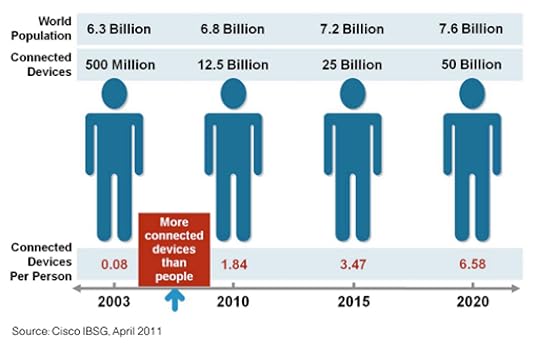

A look at the ‘Internet of Things’

Everyday objects are becoming increasingly connected to the internet. Whether it’s a smart phone that allows you to check your home security, or an app that lets you start your car or close your garage door from anywhere in the world; these technologies are becoming part of what is known as the Internet of Things (IoT). An observable trend is the rapid deployment and consumer use of IoT devices, which can communicate with one another and share information without user input or activity. This trend is evident in the now billions of IoT devices in use by individuals and organizations in public and private sectors. These IoT devices connect people, animals, plants, and objects to the Internet.

People have, and can, become part of the IoT through wearable devices and clothing, including, but certainly not limited to: Garmin Vivoactive, a wearable device that includes, among other features, a global positioning system to track exercise activities; Cityzen Sciences’ D-Shirt that tracks the hear-trate and temperature of a person, as well as the speed and intensity of an individual’s workout; Athos clothing which monitors heart-rate, breathing, and progress of workout and goals; Ralph Lauren’s Polo Tech Shirt designed to monitor the calories burned and the intensity of a workout, stress levels, and heart-rate, among other things; Misfit Shine, a wearable device that tracks adult exercise activities and sleep patterns; Exmovere’s ‘Exmobaby’ that tracks baby’s vital signs, mood, temperature, and movement; and Mimo’s Smart Nursery, which monitors babies’ positons, breathing, and sleeping patterns.

Like humans, animals have been (and can be) connected to the IoT via sensors and wearable devices. For example, the Scout5000 enables the monitoring of pets by providing their owners with an activity pedometer, live streaming of pet activities, and the ability to engage in two-way remote communication with their pet. Similarly to animals, plants are also linked to the IoT via sensors. A case in point are Koubachi sensors that are designed to monitor plants by measuring conditions such as soil moisture and light, for optimal plant growth in individuals’ homes and gardens.

Image Credit: “The Internet of Things – How the Next Evolution of the Internet Is Changing Everything” by Dave Evans. Source: Cisco IBSG, April 2011. Image used with permission.

Image Credit: “The Internet of Things – How the Next Evolution of the Internet Is Changing Everything” by Dave Evans. Source: Cisco IBSG, April 2011. Image used with permission.In addition to people, animals, and plants, objects are IoT-enabled. These objects can be found in a variety of settings, including homes, work places, and education and healthcare centres. In the home, for example, IoT devices have afforded individuals the opportunity to remotely monitor and control energy use, household appliances, and the security of their homes. An example of an IoT technology used in homes is ‘Netatmo Welcome’. This technology uses cameras with facial recognition software to identify entrants to and/or those within a home. Those identified by the camera, both known and unknown, are sent to the owner’s smartphone. ‘Netatmo Welcome’ keeps a record of those who entered the home and the time and date that they entered. It further provides owners with access to the camera’s live streams and past events. Another area in which IoT devices are used is in healthcare. There are numerous IoT-enabled medical devices that are designed to remotely monitor patients’ vital signs, such as breathing, heartrate, blood pressure, and temperature, and internal functions, such as blood sugar levels. Some IoT medical devices are designed to alert physicians in a timely manner if the patient’s vital signs or internal functions are abnormal to prevent harm or even death of a patient.

The purpose of connecting people, animals, plants, and objects to the Internet is to enable their remote, real-time monitoring and the vast collection, storage, usage, and sharing of information about them in order to provide a service to the user. Ultimately, the automation capabilities of the IoT are designed to improve efficiency of actions and activities. IoT devices benefit the user by saving money and time, improving quality of life, and increasing convenience. For medical devices, these benefits can include lowered costs of care, improved quality of care, and improved outcomes for patients. These benefits and conveniences, however, come at a cost: namely to security and privacy. Overall, IoT devices were not built with security or consumer privacy in mind. Accordingly, measures are needed to ensure that these devices and the data they collect are protected from cyberattacks and unauthorized access, monitoring, sharing, and use, to ensure that we can use IoT devices to our advantage and not to our detriment.

Featured Image Credit: “Network – Internet of Things”, by jeferrb. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A look at the ‘Internet of Things’ appeared first on OUPblog.

July 27, 2015

India’s unique identification number: is that a hot number?

Perhaps you are on your way to an enrollment center to be photographed, your irises to be screened, and your fingerprints to be recorded. Perhaps, you are already cursing the guys in the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) for making you sweat it out in a long line. That’s why I want to tell you what these guys really do.

Let me begin with some numbers. The UIDAI claims it will assign a number to half of India’s population by 2015: 600 million Indians to be photographed; 1.2 billion irises to be screened; six billion fingerprints to be collected; and 600 million addresses and other personal particulars to be gathered and brought on record.

When the 600 millionth individual is given her number, the UIDAI system will compare it with 599,999,999 photographs, 1,119,999,998 irises, and 12,999,999,999 fingerprints to make sure that the number being assigned is indeed unique. When in full flow, and right now, it is in full flow, the UIDAI system is adding a million names to its database every single day until the task is completed. No system in the world has handled anything on a mind-boggling scale like this.

Image credit: Iris Scan – Biometric Data Collection – Aadhaar – Kolkata by Biswarup Ganguly. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Image credit: Iris Scan – Biometric Data Collection – Aadhaar – Kolkata by Biswarup Ganguly. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsYou may well ask: what’s wrong with photo identity cards, PINs, or passwords as identifiers? Photographs turn yellow with age, and PINs and password may be forfeited, forgotten or lost, but the body can always provide an unfailing link between the record and the person. The UIDAI system uses biometrics, a far more potent marker. The beauty of biometrics is that it is able to find an anchor for identity in the human body to which data and information can be fixed, so that the biometric identifier becomes the access gateway to the data field.

The UIDAI gives a 12-digit number after receiving and verifying biometric and demographic information. It sends the number along with other information to its central server for verification. The server verifies whether the data sent matches your identity and confirms ‘who you say you are’. Sometimes, funny things happen when the numbers are issued. A unique identification number card was issued in the name of a coriander plant with the photograph of a mobile phone fixed on it. The officials have absolutely no clue of the address to which the card has to be delivered.

Perhaps, the question that is foremost in your mind is: what will the number do for you? Well, if you are below the poverty line, the UIDAI says it is going to do wonders for you. All the subsidies that the government gives to the poor (most subsidies do not reach the poor because the delivery system is so leaky) will now be delivered directly to their doorstep, thanks to the unique identification number.

The unique identification number will make financial inclusion possible for the poor by bringing them benefits directly in cash and giving them the wherewithal for being consumers of the market. The market, by offering a choice of goods, services, experiences, and lifestyles, will enable the poor to define who they are or want to be. They will be free to live their lives in terms of choice and freedom. So, through the unique identification number programme, the government will make the poor free.

If you haven’t got hold of a magic number, please do hurry. You can’t afford to be left out of the bonanza, can you?

Featured Image: “Fingerprint detail on male finger” by Frettie. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post India’s unique identification number: is that a hot number? appeared first on OUPblog.

How much money does the International Criminal Court need?

In the current geopolitical context, the International Criminal Court has managed to stand its ground as a well-accepted international organization. Since its creation in 1998, the ICC has seen four countries refer situations on their own territory and adopted the Rome Statute which solidified the Court’s role in international criminal law. Is the ICC sufficiently funded, how is the money spent, and what does this look like when compared to other international organisations?

Download the full-size jpg.

Featured image: ‘Prison Gate’ by Christopher A. Dominic. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How much money does the International Criminal Court need? appeared first on OUPblog.

July 26, 2015

Ten myths about the French Revolution

The French Revolution was one of the most momentous events in world history yet, over 220 years since it took place, many myths about it are still firmly entrenched in the popular psyche. Some of the most important and troubling of these myths relate to how a revolution that began with idealistic and humanitarian goals resorted to the “Terror”. It is a problem that is as pertinent for our own world as it was for the people of the late eighteenth century.

1. The French Revolution was made by the poor and hungry.

False. Or not initially, though they were certainly involved later. The Revolution was begun by members of the elite, many of them nobles, following a financial crisis which led to state bankruptcy, loss of confidence in the monarchy, and political destabilisation. Almost every successful revolution begins with divisions amongst the ruling elite and loss of control of the army. If revolutions were made by the poor, the hungry, and the desperate, they would happen far more often.

2. Marie-Antoinette, on being told that the people had no bread, replied, “Let them eat cake”.

No, she didn’t. Nor did she suggest they might try brioche, croissant, or any other culinary delicacy. It is true, though, that she was supremely ignorant of, and indifferent to, the lives of the poor. She didn’t have all the affairs her enemies credited her with either – just one, with the Swedish noble, Fersen. But it was true that she was a big spender, lavishing money on a select group of her favourites. It is also true that during the Revolution, in 1792, she betrayed the battle plans of the French to the Austrian invaders in the hope that the French armies would be defeated and the monarchy restored.

Image Credit: ‘Marie-Antoinette, Portrait with a Rose’, by Élizabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1783); from the Musée National du Château de Versailles. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Marie-Antoinette, Portrait with a Rose’, by Élizabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1783); from the Musée National du Château de Versailles. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.3. The French Revolution of 1789 and the fall of the Bastille led directly to the overthrow of the monarchy.

False. The revolutionaries of 1789 set up a constitutional monarchy. This lasted three years. In the end the constitutional monarchy fell in large part because it became obvious that the king himself didn’t accept it, when in June 1791 he attempted with his family to flee France in the flight to Varennes, a plan largely orchestrated by Marie-Antoinette and Fersen. Suspicion of the monarchy was a big factor in the declaration of war on the foreign powers in April 1792. It was a war that went very badly for France and led to a second revolution, on 10 August 1792, that overthrew the monarchy. A National Convention was instated, voted for on the basis of a democratic male franchise. Its deputies declared France to be a republic.

4. Brissot’s Girondin faction were the moderates, opposed to Robespierre’s bloodthirsty Jacobins.

Not true in 1791-1792, when Brissot was the voice of the radical Revolution, calling for war with the foreign powers, in the hope that the turmoil of war would expose the treason of the king. Brissot’s war plan was opposed by Robespierre who thought it a crazy idea, which could go badly for France and lead to increased militarisation. But at the time Brissot’s war policy was popular, and Robespierre was marginalised as a prophet of doom. The situation only changed because events proved Robespierre right. As he had predicted war destabilised the political situation. It generated panic and the search for conspirators. The Girondins were caught up in that downward political spiral, were outflanked, and became moderates. They were overthrown at the demand of the Paris popular militants, the sans-culottes, and condemned as traitors in league with the foreign powers – though their real faults were incompetence, ambition, and recklessness.

5. The Jacobins installed a “system of terror” in September 1793.

A contentious statement. Many historians contest it, pointing out that it wasn’t just the Jacobin deputies in the Convention who voted for terror – it was a policy supported by many deputies. They passed a series of laws which enabled them to use terror. They saw it as justice – albeit the harsh justice of wartime. It was chaotic, ad hoc, and violent certainly, but not a coherent system.

6. The guillotine was the principal means of execution, routinely used from the early stages of the Revolution to hack off the heads of counter-revolutionaries.

No. The revolutionaries of 1789 did not foresee the recourse to violence to defend the Revolution and some, like Robespierre in 1791, wanted the death penalty abolished altogether. Execution by guillotine began with the execution of the king in January 1793. A total of 2,639 people were guillotined in Paris, most of them over nine months between autumn 1793 and summer 1794. Many more people (up to 50,000) were shot, or died of sickness in the prisons. An estimated 250,000 died in the civil war that broke out in Vendée in March 1793, which originated in popular opposition to conscription into the armies to fight against the foreign powers. Most of the casualties there were peasants or republican soldiers.

Image Credit: ‘The Death of Marat’ by Jacques-Louis David (1793), from the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘The Death of Marat’ by Jacques-Louis David (1793), from the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.7. Nobles were subject to execution simply for being nobles.

False. Though nobility was abolished in June 1790 it was never illegal to have been a noble. Some high-profile nobles did die, and many more came under suspicion. Those who fled the country, and became émigrés were subject to execution if they returned. But most held tight and waited for the tide to turn.

8. Robespierre was a dictator who masterminded the ‘Reign of Terror’.

Robespierre’s time in power lasted just one year, from July 1793 to his death in July 1794 in the coup of Thermidor and even in that time he was never a dictator. He shared that power as one of twelve members of the Committee of Public Safety, its members elected by the Convention, which led the revolutionary government. He defended the recourse to terror, but he certainly didn’t invent it.

9. Once you were sent before the Revolutionary Tribunal you had no chance of acquittal – the only outcome was the guillotine.

Nearly half the people sent before the Revolutionary Tribunal in Paris were acquitted. Even after the Law of Prairial in June 1794 expedited the work of the Revolutionary Tribunal, nearly a quarter of the accused escaped with their lives. Ironically, an exception was the revolutionary leaders themselves – all the revolutionary leaders who were sent before the Revolutionary Tribunal between autumn 1793 and summer 1794 were condemned to death.

10. The overthrow of Robespierre in Thermidor (July 1794) was brought about to end the Terror and instil democracy.

No. Robespierre’s fall and execution was engineered by a group of his fellow Jacobins, some of whom were more extreme terrorists than he was, because they thought he was about to call for their arrest and feared for their own lives. They assumed that the terror would continue. As one deputy admitted, Thermidor was not about principles, but about killing. In the turmoil that ensued, moderates were able to regain the initiative and after over 100 of Robespierre’s supporters were guillotined, slowly the terror laws began to be wound down. Successive regimes (the Thermidoreans and the Directory) were not interested in democracy but in keeping the middle classes in power. The Constitution of 1795 reinstated a franchise restricted to men with property.

Featured Image Credit: ‘The Taking of the Palace of the Tuileries, 10 August 1792’, by Jean Duplessis-Bertaux, from the National Museum of the Chateau de Versailles. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ten myths about the French Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know Jacques Derrida? [quiz]

This July, the OUP Philosophy team is featuring Jacques Derrida as their Philosopher of the Month. Derrida was an Algerian-born French philosopher known for his work on deconstruction and postmodern philosophy and literature. A controversial figure, he received criticism from many analytic philosophers. Derrida passed way in 2004, but his works has had a lasting impact on philosophers and literary theorists today.

Take our quiz to see how well you know the life and studies of Derrida.

You can learn more about Derrida by following #philosopherotm @OUPPhilosophy

Feature Image: Building Hotel Classic Architecture Traditional by Unsplash. Public Domain via Pixabay

The post How well do you know Jacques Derrida? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

July 25, 2015

Pluto and its underworld minions

Early this week, the spacecraft New Horizons began its flyby of Pluto, sending a wealth of information back to Earth about Pluto and its moons. It’s an exciting time for astronomers and those intrigued by the dark dwarf planet.

Pluto has special significance not only because it is the only planet in our solar system to have its status as a planet stripped and downgraded to a dwarf planet, but also because along with its largest satellite Charon, it is our solar system’s only binary planet system. In addition to Charon, Pluto has four additional satellites that have intriguing characteristics. Three of these—Styx, Nix, and Hydra—are in what astronomers call an orbital resonance, which means their orbits are related by a ratio of two whole numbers, making the orbits predictable and relatively stable. However, at least Nix and Hydra have an elongated shape and feel the gravity of both Pluto and Charon, such that their motion is extremely complicated. Astronomers refer to this as chaotic rotation, meaning that to an observer on its surface, the Sun can rise and set from random, different directions and the length of a day can also vary greatly. It is also possible that Styx and Kerberos are also in chaotic rotation; however this hasn’t been confirmed yet.

How a planet gets its name

Of course, Pluto is also interesting linguistically. How does a planet get its name? Since 1919, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) has chosen names for planets and celestial bodies as they are discovered. They have a number of guidelines for suitable names.

Keeping with tradition, the planet (as it was classified when it was discovered in 1930) was named after the Roman god of the underworld, Pluto. The name was suggested by Venetia Burney, a schoolgirl from Oxford who had offered it to her grandfather who passed the suggestion on to an astronomy professor, or so the story goes. When it was put to vote by the IAU, Pluto won unanimously. It was also a nice nod to the astronomer Percival Lowell, as his initials are the first two letters of the name Pluto.

Naming Pluto’s moons

Pluto’s largest satellite or moon, Charon, was discovered in 1978 by James Christy and named after the Greek mythological ferryman of the dead. Charon was suggested by Christy who chose the name for its mythological relevance as well as the similarity to his wife’s name ‘Charlene.’ In fact, it’s this charming story that explains why there are two pronunciations of Charon: one with an initial hard ‘k’ and the other with a soft ‘ch’ sound. Apparently Christy and his colleagues pronounce it with a soft ‘ch’ in reference to Christy’s wife, while the hard ‘k’ pronunciation is used by everyone else. Charon, like Pluto, has a contested classification. Although it was first discovered as a moon or satellite of Pluto, as part of a binary system, it could be declared as a dwarf planet in its own right.

Pluto’s additional moons (or true moons if you consider Pluto and Charon as a binary system) were all discovered in the last ten years: Styx (2012), Nix (2005), Kerberos (2011), and Hydra (2005). Each of these is also named in keeping with underworld mythological conventions. Styx is the river one would cross during death. Nix is another spelling for Nyx, the Greek goddess of the night and darkness; the alternate spelling for Nyx was used as there was already an asteroid named Nyx. Kerberos is actually the Greek spelling of Cerberus, the underworld’s three-headed dog. The Greek spelling was chosen as Cerberus was already the name of an asteroid. Hydra is a multi-headed serpent creature that was guardian to the subterranean entrance to the underworld.

While the mythologies for which Pluto and its satellites are named captivate our imaginations, we continue to discover how the celestial bodies themselves are equally if not more captivating in reality. We can only wait and see what New Horizons uncovers about the mysterious dwarf planet and its orbiting minions.

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “New Horizons 3-billion-mile Journey to Pluto Reaches Historic #plutoflyby!” by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Selfies in black abayas

Today, when worlds collide with equal force and consequence as speeding cars on a California highway, can we imagine, escaping the impact of even a single collision? Is the option of being miraculously air-lifted out of the interminable traffic log-jams available for us, even if we are spared physical injury? Just as avoiding California highways is an impossibility (given the systemic destruction of public transportation system), meeting head-on forces of neoliberal globalization with its unique technological, financial, and ideological structures is an inevitability.

No one can be immune to them, least of all those individuals who carve out pulpits in digital spheres to ride on resonance created by viral messaging, to vociferously denounce change, and to profess antediluvian ideologies. Everyone is inexorably a part of the contemporary social and economic reconstruction of our worlds. Even those who are ensconced in rural backwaters and are uncaring of the new logic are nonetheless to drawn into its vortex. Tragedies such as the one at Rana Plaza in Dacca, Bangladesh, exemplify its brutalities. Rural and urban poor are pulverized among labels of global brands and multinational corporations, which mark their personalities equally on shoddy, illegal constructions and on indices of wealth and status.

This is an age of impurities, where boundaries are difficult to maintain and everything collides into the other. Unyielding powers create change far beyond our control. How is it then that we continue to talk about the relentless flux of our immediate realities in neat terms that invoke order and permanence? More importantly why do we continue to presume that some individuals have been left outside of these massive realignments to dwell alone in their isolated or pristine worlds? Or that the world can be precisely reconfigured in taxonomies that work only in the binaries and create divisions such as traditional and modern or fundamentalist and cosmopolitan?

Such viewpoints impose artificial clarities and attempt to contain complexities within simplistic rather than simple categories.

For example, how would you describe the women who grace the photograph on the cover of my book? Here are two young women, dressed in black abayas (the Middle Eastern style cloak and veil), covered from head to toe to signal their allegiance to a modest and decidedly non-Western femininity. Meanwhile, they take pictures of themselves on their iPad to upload within minutes on Facebook or Instagram, waiting with bated breaths for the number of “likes” their photo would receive. Should their personalities be locked within stereotypical perceptions of Muslim women as oppressed and backward? Should their engagement with modern technologies be seen as superficial and unimportant to creating any meaningful engagement with modernity?

It is still generally believed in a country, which has undergone a total overhaul not only in spheres of economy but also personal ideologies and public sensibilities, that Muslim youth have somehow miraculously been air-lifted out of any collisions with the force of new ideas.

However, if the definition of being modern involves an awareness of multiple options and a desire for exploration, then these women are decidedly modern. The media, which peddles anything and everything with slightest potential of being saleable, brings home to them the many options for self-construction both from the West as well as the East. A veiled persona is one among the many alternatives available to them. Their veil, which is imported from the entrepots of the Middle East, and has nothing to do with dowdy burkha worn in India before, implies travel, consumerism, and visions of cosmopolitanism — and this notwithstanding the dominant tendency to see only imports from the West as indicating modernity.

The fact is that these young people are avid pupils of self-help and self-reconstructive philosophies, which are so integral to modern lifestyles. Like other young people, they draw on their extended ambit of their forays, made wider by the omnipresence of media and the preeminence of imagination in everyday life, to find and create “the new me”. The choice of wearing veil is as much a negotiating stance with a patriarchal society as a wish to be more desirable in the marriage market by presenting themselves as the alternative foil to the permissive modern woman. I see this sartorial adventure as no different from the decision of wearing a smart suit to land a job at a multinational corporation. Their modernity is complex and filled with anomalies such as the dreams for being “a working housewife,” but are nonetheless informed by larger debate about citizenship and rights. Otherwise how would it be possible to assay the veiled persona in a climate of rabid anti-Islamicism? Most importantly their complexities make us rethink the definition of modernity, and to redefine from spaces other than those in the western hemisphere.

Featured image: Architecture Detail on Qutub Minar, Delhi. © Bulent Ince via iStock.

The post Selfies in black abayas appeared first on OUPblog.

Preparing for IVR 2015

The XXVII World Congress of the International Association for the Philosophy of Law and Social Philosophy (IVR) will take place 27-31 July 2015 at Georgetown Law Center in Washington, DC. This year’s theme — “Law, Reason, and Emotion” — focuses on the nature and function of law.

Whether they exist in harmony or contention, law, reason, and emotion always play a role in legal discourse. IVR will explore the legal system’s balance between reason and justice with recognition of society’s emotional basis. The conference’s four days of plenary lectures, working groups, and special workshops will examine this relationship.

Plenary lectures will be held each morning at 9:30 a.m. and 11:30 a.m. András Sajó kicks off the first day of the conference, Monday 27 July, with “The Constitutional Domestication of Emotions” at 11:30 a.m. Sajó, one of the editors of The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Constitutional Law, will discuss how early liberal constitutions and the consolidation of the institutions of constitutionalism show that emotions cannot be separated from reason and law. If you want to brush up on comparative constitutional law before the conference, read the introduction of Sajó’s Handbook, freely available on Oxford Handbooks Online.

Special Workshops, which take place every day from 2:30 p.m.-6:30 p.m., will be another conference highlight. These discussion forums are based on collections of papers and feature insight from many key contributors to the field. Over 25 individuals will participate in “Bulygin’s Philosophy of Law” on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday, a presentation of the recently published edited volume of Eugenio Bulygin’s Essays in Legal Philosophy. You can prepare for the session by reading the introduction of the book, which is available in English for the first time. All the conference’s Special Workshops are sure to incite discussion among conference attendees. Working groups, also held daily, will be opportunities to present papers not included in the Special Workshops.

With its variety of lectures and workshops, IVR promises to be an engaging and insightful four days, but don’t forget to take some time to explore some of the city’s many attractions. The conference’s location puts you in close proximity to the famous National Mall and Memorial Parks, but if you’re looking for something different, we suggest:

The National Postal Museum is located in the historic City Post Office Building, just blocks from Georgetown University Law Center. The museum was constructed in 1914 and acted as Washington DC’s post office from 1914 to 1986. There is a 6,000-square-foot research library, as well as five exhibit galleries that tell the story of postal history in America. The National Postal Museum contains one of the world’s largest collections of stamps and philatelic materials, in addition to postal history material that pre-dates stamps, vehicles used to transport the mail, mailboxes and mailbags, postal uniforms and equipment.

The Upper and Lower Senate Park is located between Constitution Avenue, NW, and D Street, NE, and 1st Street and Louisiana Ave, NW. The lower section contains a rectangular reflecting pool bordered by pathways and fountains, and is surrounded by two sets of steps. The upper section is situated on a large fountain and plaza and a tree-lined lawn panel joining the Senate and Capitol grounds.

The National Guard Memorial Museum is located at the corner of Massachusetts Avenue NW and N. Capitol Street. This is the only national museum devoted to telling the story of the citizen-soldier and the National Guard. Five exhibit areas and various theatres show the history of the National Guard from the 17th century to today.

If you’re joining us at IVR, don’t forget to stop by the Oxford booth to take advantage of the 20% conference discount on our collection of books and browse our online products. You can also pick up a free copy of one of our law journals. The American Journal of Jurisprudence may be of particular interest to conference attendees. It explores current and historical issues in ethics, philosophy of law, and legal theory. The editors have selected articles from the journal’s archive and made them freely available for your perusal.

To stay up to date with IVR, like Oxford International Law on Facebook and follow @OUPIntlLaw on Twitter. See you in DC!

Featured image: Georgetown. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Preparing for IVR 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

The end of liberalism?

Following the disastrous performance of the Liberal Democrats in the recent British election, concern has been expressed that ‘core liberal values’ have to be kept alive in British politics. At the same time, the Labour Party has already begun a process of critical self-examination that would almost certainly move it to what they consider more centrist ground—and there has been some talk of Labour and the Liberal rump forming some sort of alliance. Even so, it is clear that this is not vacant ground, but ground they want to contest with David Cameron, who currently holds more sway there. But is this ground really distinct from the ‘core liberal values’ that Liberals are so keen to defend? And in what sense is the election of evangelical Christian Tim Farron to the leadership of the Liberal Party compatible with ‘core liberal values’?

How would we identify those values? We can talk about liberty, equality, the defence of the individual against unwarranted encroachment by the state, the promotion of education, the tolerance and freedom of speech—but what do these big ideas actually entail in the messy realities of practical politics in the early twenty-first century? How do we translate abstract values into practical policies? What sort of limits have to be placed on individual liberty to protect national and collective security? How much does formal equality before the law require a range of other dimensions in order to be fully realized? What are the limits of tolerance for non-liberal cultures within a liberal state?(For example, should France’s stand on the niqab or burka be replicated in Britain?)

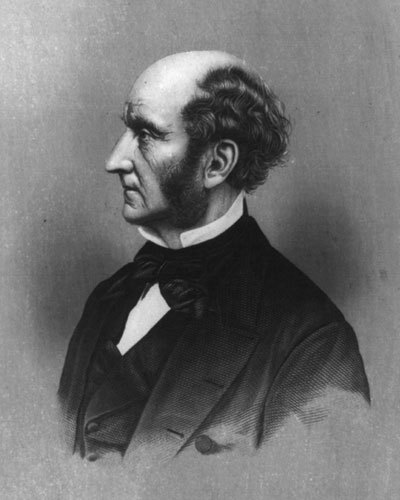

One might think that a return to earlier liberal thinking in this day and age is merely an intellectual indulgence, but that is partly because we are often poor readers of our precursors. Although John Stuart Mill does not have off-the-peg solutions to multiculturalism, benefits traps, or terrorism in the modern state, he remains the founding father of secular liberal thought, and his approach remains wholly pertinent. We are used to reading him as a defender of individual liberty, as an advocate of utilitarianism (with some sense of tension), and we use his work as an often brilliant source book for ideas about political and moral philosophy. But we too often mistake him for a secular liberal universalist—a claim that fails to grasp the complexity of his thinking, and its rootedness in wider sociological traditions of European thought.

Mill’s liberal principles were partly a response to what he saw as the distinctive possibilities and difficulties arising in the age in which he lived. His key essays are best understood, not as inter-related arguments developing a universal framework for ethical and political thought, but as forays into issues that he saw as particularly troubling: the oppression of the individual by the masses, the subjection of women, the need for institutional design to combine democratic participation with responsible decision-making, and so on. The solutions he advanced were not intended to apply to all societies irrespective of their development or conditions. They were pointed proposals to deal with particular evils or realize certain potential goods, in the particular context in which he wrote.

That means that we can learn greatly from him, but that we also have to do some work. We need serious debate about these ‘core values’ and how to realize them in our particular historical context. Understanding Mill better will help us see that the idea of a political spectrum being adequately captured by a single axis of left-to right makes no sense, given the plurality of the values we are committed to, the conflict between those pluralities, and the conflict between policies that increasingly realize these pluralities. As Mill makes clear in Utilitarianism and On Liberty, the world of value is plural, contested, and complex. If the lode star is some idea of individual happiness rooted in a conception of the full development of individual potential, that is not an especially powerful guide, since the content of that idea is something that is historically conditioned, deeply influenced by the challenges and opportunities that a society presents to its members, and is something that changes over time.

“John Stuart Mill” by Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“John Stuart Mill” by Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Mill may not, then, provide us with answers for our time. But he does provide us with some of the best material to reflect on the problems of our society and the possibilities we face. He makes us think harder and more critically about the idea that there is some list of indefeasible goods or rights that apply in every society. Moreover, he does so while sustaining a conception of the core ethical criteria that must enter into the assessment we make of what can and should be done, here and now, in relation to particular challenges.

The partisan world of Westminster politics was one that Mill found challenging during his brief period as an MP. But he brought an intelligence and judgment to debates that is now rarely seen. He did so partly because he was a deep and systematic thinker, because he was open-minded and tolerant, because he did not think the happiness of the few should be sacrificed to that of the manyor vice versa, and because he was historically and sociologically aware that his time had a particular character, calling for particular measures. The sloppy generalities of most politicians and commentators, the sound-bite filled 24/7 news culture that they live in and exacerbate, and the shabby appeal to partisanship rather than principle, threaten to further deplete the trust of ordinary people in the political process. Doing that will leave us open to abuse, as values of fairness, equality, tolerance, and respect for the individual are not an inheritance that we can take for granted; they are an increasingly fragile cultural legacy that has either failed to take root, or has yet to take root in the majority of countries around the world.

Keeping ‘core liberal values’ alive is not simply a case of rehearsing standard pieties. It demands deep and challenging thought about what is required in this particular historical situation, in order to protect and advance the potential for the success of all of its members against a range of potential threats, including members from the state as well as forces outside the state. Mill has no simple solutions to our problems, but understanding his thinking cannot fail to improve our own.

Image Credit: “Old Books” by ChristopherPluta. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The end of liberalism? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers