Oxford University Press's Blog, page 634

August 3, 2015

Animal, vegetable or mineral? [quiz]

In the late eighteenth century, against a troubled background of violent change on the continent and rising challenges to the Establishment at home, botanists were discovering strange creatures that defied the categories of ‘animal, vegetable, and mineral’. Scientists started to question: What of coral? Was it a rock or a living form? Did plants have sexes, like animals? The boundaries appeared to blur. And what did all this say about the nature of life itself? Were animals and plants soul-less, mechanical forms, as Descartes suggested? The debates raging across science played into some of the biggest and most controversial issues of Enlightenment Europe. Take the quiz below and test your knowledge of this exciting period in the history of life sciences.

Quiz image credit: Low Tide, by Dawn Endico. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flikr.

Featured Image credit: Coral Reef at Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, by Jim Maragos/U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. CC BY 2.0 via Flikr.

The post Animal, vegetable or mineral? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about Nordic countries and international law?

Which Nordic state had sovereignty over Iceland until 1918? Which state was allowed to discriminate against a transgender woman by annulling her marriage? Who disputed ownership of Eastern Greenland before the Permanent Court of International Justice? Which Nordic state has been the subject of the most UN human rights complaints? In preparation for the European Society of International Law’s 11th annual conference, this year held in Oslo, test your knowledge of Nordic countries in international law with our quiz.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Featured image: Oslo, view of the main harbour at sunset from beneath the fortress. Photo by Moyan Brenn (Francesco). CC BY 2.0 via aigle_dore Flickr

The post How much do you know about Nordic countries and international law? appeared first on OUPblog.

Being a responsible donor

Part one of this post addressed a familiar question: how should individuals concerned about international issues decide where to donate money? Here I turn to a second, less familiar question that follows from the first: what is entailed in being a responsible donor after the question of where to donate has been settled? While this latter question cannot be sharply distinguished from the former, my main focus here will be: what are individuals’ responsibilities after they click on the “donate now” button?

A large literature offers ample evidence that humanitarian and development aid organizations frequently have unintended negative effects. For example, by bringing large quantities of resources into high-conflict, resource-poor areas, humanitarian aid frequently exacerbates tensions among social groups. Humanitarian aid can also displace governments by providing goods and services in their stead, thereby reducing governments’ capacity and perceived legitimacy. Development aid can promote counterproductive social policies. Both kinds of aid can lure talented local professionals away from positions in government and public universities by offering higher-paying NGO jobs, thereby weakening the public sector; development and humanitarian aid can also distort local markets by increasing demand for some goods and services (e.g. drivers, housing) and lowering the cost of others (e.g. staple foods).

While unintended, many of these negative effects are by now anticipated, at least in their general outlines. The best organizations work hard to minimize them, but some negative effects remain. Aid organizations must therefore make difficult practical judgments about which of these unavoidable negative effects to grudgingly accept as a “cost of doing business,” and which to avoid by reducing or even eliminating aid in some contexts.

“Food Chain” by United States Marine Corps Official. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

“Food Chain” by United States Marine Corps Official. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.In short, donating to aid organizations is not like putting coins into a “do-gooding machine” that magically transforms money into lives saved or poverty alleviated. It is, instead, more like many other human endeavors: messy, uncertain, ambiguous, and morally risky.

Indeed, donating to aid organizations is in many respects like donating to the campaign of a candidate for elected office. However, because donors typically fund aid organizations that work far away, donating to an aid organization is like funding the campaign of a candidate for elected office in another country. And because aid recipients typically cannot sanction aid organizations (via a vote, withholding funds, or other means), donating to an aid organization is most like funding the campaign of a candidate for elected office in a foreign country in which many people are disenfranchised.

This analogy suggests that donors have at least three distinct responsibilities after they donate.

First, just as citizens don’t expect politicians to have only positive effects, donors should not expect aid organizations to have only positive effects. Expecting aid organizations to have only positive effects perpetuates a vicious cycle in which aid organizations do not disclose their negative effects because they fear losing donors, and donors, in turn, never learn that some negative effects are an unavoidable aspect of aid provision. Rather than expecting aid organizations to be do-gooding machines, donors should ask the organizations they fund to engage in open and frank communication regarding both the positive and negative effects of aid.

Second, just as democratic citizens communicate with their elected representatives and hold them accountable if they perform badly (by voting them out of office or not contributing to their campaigns), donors should also communicate with the organizations they fund, and hold them accountable if they perform badly, by withdrawing funding.

“Refugee camp in Liberia, along the Ivory Coast border” by Oxfam International. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

“Refugee camp in Liberia, along the Ivory Coast border” by Oxfam International. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.There are at least two ways that donors might hold aid organizations accountable: by demanding that they meet specific ex-ante requirements and/or by asking them to explain and justify their actions ex-poste. Because aid organizations work in unpredictable contexts, have reason to be responsive to aid recipients’ preferences, and are constantly learning new things, donors should put relatively more weight on ex-poste explanation (e.g. asking aid organizations to explain what they accomplished after the fact) rather than demand compliance with very specific ex-ante promises.

Third, just as powerful citizens have a responsibility to fight for the enfranchisement of those who have been wrongfully excluded from a political community, donors also have a responsibility to support aid recipients’ capacity to hold aid organizations accountable. In other words, it is not enough for donors to hold aid organizations accountable directly themselves. They must also encourage aid organizations to be more accountable to the people they most directly affect: aid recipients and other vulnerable people significantly affected aid organizations’ activities (such as poor people who live nearby to refugee camps).

These three responsibilities— developing appropriate expectations, holding aid organizations accountable, and empowering aid recipients to hold aid organizations accountable—are really difficult to fulfill. Most ordinary individuals in wealthy countries who donate to aid organizations know very little about aid, compared to both aid workers and aid recipients. They also often feel that they have “done their bit” by donating. Putting these two thoughts together, they conclude that it was (more than) enough for them to donate money, and they are more than justified in leaving everything else to the professionals.

I think this conclusion is too hasty. First, donors can do relatively simple things, like ask the organizations they fund what sorts of negative effects they have, and in what ways they are accountable to their intended beneficiaries (and other vulnerable people). In addition, the very fact that donors are differently situated than aid organizations, and have different incentives, suggests that their biases are likely to be different, which in turn suggests that the process of aid organizations justifying themselves to donors might well be fruitful—despite donors’ limited knowledge. Indeed, while its implications for donating have yet to be worked out in detail, research on epistemic democracy suggests that groups—especially diverse groups— can exercise good judgment, even when individuals within that group are relatively ill-informed. While this does not mean that donors can ever be adequate surrogates for aid recipients themselves, it does suggest that donors’ ignorance might not be quite as much of a roadblock as it might initially appear to be.

That said, the difficulties, for donors, of fulfilling the responsibilities to which donating seems to give rise suggests the need for structural reform in the aid sector more generally. In particular, responsible donorship, as I have described it, would be more feasible if there were more watchdog organizations, “meta-charities,” journalists, and other actors and institutions independent from aid organizations, devoted to providing donors with relevant information—including, especially, organizations with the capacity to listen to aid recipients directly. Ideally, this information would come from a wide range of disparate sources, perhaps roughly analogous to the information provided by political parties, endorsements, online commentary and journalism in the context of conventional politics.

The description of responsible donorship that I have sketched here suggests that donating—even donating motivated by a simple desire to “do good”—offers no escape from the messy world of politics. There are no magical do-gooding machines. We must alter our expectations, and design our institutions and practices, to accommodate this fact.

Headline image credit: “Providing clean water to millions of people” by DFID – UK Department for International Development. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Being a responsible donor appeared first on OUPblog.

August 2, 2015

Dangerous minds: ‘Public’ political science or ‘punk’ political science?

The end of another academic year and my mind is tired. But tired minds are often dangerous minds. Just as alcohol can loosen the tongue (in vino veritas) for the non-drinkers of this world fatigue can have a similar effect (lassitudine veritas liberabit). Professional pretensions are far harder to sustain when one is work weary but I can’t help wondering if the study of politics has lost its way… heretical to hear or music to the ears of the disenchanted?

What is the core role of a professional political scientist in the twenty-first century? Where do our social and professional responsibilities lie within and beyond the discipline? How does political science differ, if at all, from the broader social sciences in terms of defining principles and values? On what criteria should we judge success and failure? How is the external context in which political science operates changing and what role is the discipline playing in terms of shaping or informing that context? These are the questions that have concerned me for some years and that I have engaged with in my writing on the concept of ‘engaged scholarship’. But Jeffrey C. Isaac’s recent editorial ‘For a More Public Political Science’ in Perspectives in Politics—in my opinion possibly the best political science journal in the world—jolted me out of my end-of-semester weariness.

It is an essay that resonates with my concern over professional pretensions: “[as editor] why make believe that I am simply enacting the anonymous and ineluctable requirements of ‘science’” Isaac writes, “Everybody knows that this is not the case. And yet we so often pretend. Why pretend?”

Pretending is not something that is easy to do when you are tired and maybe that’s why Isaac’s arguments hit home with such alacrity at this particular moment in time. The lecture halls and seminar rooms are empty, most academic offices lay vacant, administrators administrate with a lazy summer swagger but in a matter of weeks the whole academic cycle will start again. Maybe that’s the problem. Could it be that the whole higher education system has become trapped in a market-led cycle or spiral of its own creation that promotes conformity over difference, results over risk, customers over citizens and ‘safe bets’ over ‘creative rebels’? This question brings me back to Isaac’s essay and its ‘academic-political purpose’:

“My purpose is simple: to clarify, defend and expand the spaces in political science where broad and problem-driven scholarly discussions and debates can flourish.”

It seems as if something is going on (again) within American political science. That all is not well and that a number of long-standing tensions and schisms that had for some time been managed through the post-Perestroikan stand-off, within which the creation of Perspectives on Politics formed a key element, have once again risen to the surface. In this context Isaac’s essay covers a lot of well-worn ground but then concludes with a distinctive twist, hook or barb. It revisits the debates concerning methodological pluralism, hyper-specialization, and a perceived statistical supremacism that have raged for several decades before then identifying and criticizing a resurgent positivism in the discipline ‘which I believe jeopardizes what this journal represents’. There is then, for Isaac, a need to politicize the internal disciplinary debate about which sub-field ‘is allowed to claim the mantle of ‘political science’ and to present itself as speaking for the discipline’. The concern is that some of the Perestroikan energies may have been co-opted or overtaken to the extent that they now threaten the sense of intellectual and methodological value, the belief that qualitative and interpretive approaches produce different but equally valid forms of knowledge to large-n quantitative analysis.

Image: “Punk”, Rock al Parque, 2010, by Lucho Molina. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr.

Image: “Punk”, Rock al Parque, 2010, by Lucho Molina. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr.But why do I care? European political science, in general, and British political studies, in particular, has generally evolved without the same internal divisions and bitter enmities. ‘Peretroika-lite’ is the way I have described the emergence of similar issues in the European context in recent years but my sense is that the shadow of exactly those neo-positivist pretensions that worry Isaac are becoming more pronounced. In the UK I am frequently told that the future of the political and social sciences lies in the realm of digital scholarship and its capacity for utilizing the increasing availability of mega-data. Now I don’t know about you but ‘data-scraping’- let alone debates about data transparency or data-analytical techniques – does not float-my-boat when it comes to thinking about my role as a scholar. However, there is also something slightly disquieting about Isaac’s position. Indeed, this is probably where the notion of ‘dangerous minds’ as a symptom of the end of my twentieth year as an academic starts to emerge. Indeed, two naughty little thoughts come to mind.

Firstly, does the notion of public political science that Isaac promotes really offer salvation to a discipline that some might see to be in perpetual crisis?

Secondly, does political science actually have anything to offer the public?

The answer to both these questions is obviously ‘yes’ and ‘yes’ but let me play devil’s advocate for a few moments in order to contribute to the debate that Isaac has so valuably initiated (or revived).

First of all the notion of public political science clearly takes its inspiration from Michael Burawoy’s influential critique of sociology and his movement for public sociology. And yet my sense is that the ambition and vigor behind the public sociology movement has always been far greater than the vision that Isaac seems to be discussing. Indeed, from my position on the other side of the Atlantic I have always been taken by how internalized the debates within American political science have always seemed to be and how little they have focused on the role of the public or the role of the discipline as an intermediary between the governors and the governed. The Caucus for a New Political Science that was founded as a section within the American Political Science Association in 1967 has, to my mind, always offered a more convincing model of public political science. The Caucus’s journal New Political Science was established in order to underline the relevance of the discipline and to promote a more problem-focused and solution-focused form of political science. The notion of public political science is therefore not a matter for intra-disciplinary debates but for the ambitious dissemination of research findings into the public sphere and also the engagement of the public within the research process. This latter element is really where the potential lies in terms of demonstrating both ‘the trap’ and ‘the promise’ (to borrow from C Wright Mills) of political science. How might we actively recruit the public as active participants and collectors of data into the research process?

Secondly, encouraging the dissemination of research findings into the public sphere is all well and good as long as the discipline actually has something to say. Put slightly differently, engaging in ‘the art of translation’ whereby the discipline ‘talks to multiple publics in multiple ways’ (to borrow one of Burawoy’s phrases) might actually be counter-productive unless it has something of value to say. This is a critical point as the discipline risks ridicule and reduced funding if the message it promotes is one of limited ambition and limited results. Now this is obviously a naughty and quite scandalous little thought that will be used against me for the rest of my career but could it be that what we actually need is not public political science but punk political science? Yes, ridiculous I know but just stick with me on this. One of the most striking elements of the rise of managerialism and market-logic within universities has been the dampening down not simply of the intellectual spirit but also and more prosaically the time to think.

Hidden behind Isaac’s analysis is the creation of an incentives and sanctions framework within higher education that says ‘This is what a successful scholar should be doing’. But where is the intellectual counter movement, the restless minds that don’t want to follow the crowd, the scholar who rejects the notion of education as little more than a preparation for the workplace and economic growth, the square pegs that cannot be knocked-into round holes? Political science just seems to have… lost its political oomph, it’s vim and vigor, its intellectual ‘get-up-and-go’ seems to have ‘got-up-and-gone’. I’m over egging the pudding (a very English phrase I’m sorry) but I wonder how many readers would pretend that this is not really the case. Could it be that what we need is not public political science but a form of punk political science that challenges all conventional ways of doing the study of politics just as the punk movement challenges conventional ways of doing politics. Whether this period of creative chaos could emerge from within given the institutional and cultural restrictions that large sections of the discipline seem to have imbued and accepted is a pointed question. But I cannot help but think it might be one that is worth exploring…

I’m sorry, I did tell you I was tired.

The post Dangerous minds: ‘Public’ political science or ‘punk’ political science? appeared first on OUPblog.

William Lawrence Bragg and Crystallography

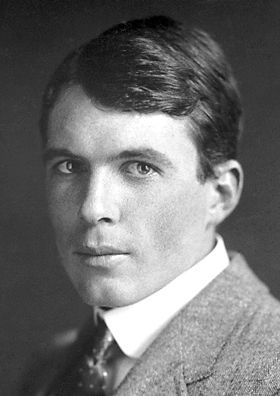

The history of modern Crystallography is intertwined with the great discoveries’ of William Lawrence Bragg (WLB), still renowned to be the youngest Nobel Prize in Physics. Bragg received news of his Nobel Prize on the 14th November 1915 in the midst of the carnage of the Great War. This was to be shared with his father William Henry Bragg (WHB), and WHB and WLB are to date the only father and son team to be jointly awarded the Nobel Prize. Experiments made in early 1912 by a German team working under the physicist Max Laue, had shown that X-rays could be scattered by a crystal, but they could not quite explain their results in full. It was WLB, at the age of 22 years, who worked out how to interpret their results and how to determine the atomic structures of crystalline solids for the first time. Father and son subsequently continued to work together, solving many crystal structures, including that of common salt and diamond, until the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. Following the war, both WLB and WHB set up renowned research groups devoted to Crystallography, producing ever more important discoveries that have led to over 26 Nobel Prizes.

WLB came from a middle-class family originating in Cumbria. He was brought up initially in Adelaide, Australia but then moved to England with his parents in 1906, where he was further educated in Cambridge. It was there that he met his wife-to-be, Alice Grace Jenny Hopkinson. She came from a totally different background, one related to the aristocracy and even to royalty. Unlike WLB, Alice had no understanding of science and was of a very different personality. He was shy, private, given to periods of depression, and intensely focussed on his research. Nonetheless he had many outside interests too; bird-watching, gardening, travelling, and especially sketching and painting, and was devoted to his family. It may be that it was this artistic bent, with his keen visual acuity, that enabled WLB at such a young age to succeed where the German scientists had failed, for Crystallography is both a mathematical and visual science. He was certainly not a member of the establishment. Alice, on the other hand, was lively, outgoing and forthright in expressing her opinions. And yet, despite these huge differences, they formed a love-match that persisted throughout all their lives together.

William Lawrence Bragg, by Nobel foundation. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

William Lawrence Bragg, by Nobel foundation. Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsThe story about WLB and his discoveries, his scientific achievements, especially those leading to many Nobel Prizes, have been well documented. However little has been made known about Alice. Fortunately, both left behind hitherto unpublished autobiographies, which reveal much about their personalities and the events that shaped their lives.

WLB’s account begins with his early years in Australia, his move to England and his famous discovery, followed by his close involvement in his work during Wold War I, where his experiments on sound-ranging enabled the enemy guns to be located with some precision. This is described in much detail. His autobiography is accompanied by many of his sketches made during his extensive travels, and he describes the many famous people whom he met and with whom he worked. Alice’s autobiography gives much detail about her early family members, some of whom were part of the German upper classes. She describes their personalities as well as their idiosyncrasies. After her marriage to WLB, she immersed herself in public duties, becoming Mayor of Cambridge, and Chair of the Marriage Guidance Council, among many other activities. She is particularly revealing about her attitudes to certain individuals within the Royal Society, who shunned her husband after he took over the Directorship of the Royal Institution following a rancorous affair that ended with the ousting of the previous Director. She has interesting comments to make too over WLB’s controversial willingness to write a Foreword to James Watson’s famous book, The Double Helix (read Kersten Hall’s blog post about William Asbury, James Watson and the forgotten road to the Double Helix), in which WLB was compared unflatteringly to Colonel Blimp. Watson has since claimed that it was Lady Bragg who persuaded her husband to write this, but in her autobiography she makes it clear that it was WLB’s decision alone.

WLB will be remembered, not only for his scientific research, but also for his impact on the many schoolchildren who attended his Schools’ Lectures at the Royal Institution. Approximately 20,000 children attended each year over a ten year period. These lectures were filled with amazing practical demonstrations covering all areas of science. WLB used to say that he wanted to show science to children.

WLB and his father can truly be said to have transformed all our lives, for their work has enabled us to understand the structures of metals, organic and inorganic compounds, pharmaceuticals, proteins, viruses, and just about everything that exists in solid form. It is interesting to speculate what the world would look like had WLB not made his discovery so long ago.

Featured image credit: Advanced Theoretical Physics, by Marvin (PA). CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr.

The post William Lawrence Bragg and Crystallography appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Lao Tzu

This August, the OUP Philosophy team is honoring Lao Tzu as their Philosopher of the Month. But who was this mysterious figure? When did he live, what did he teach, and what exactly is the ‘Tao’? Read on to find out more about Taoism:

Who was Lao Tzu?

Lao (Laozi) Tzu is credited as the founder of Taoism, a Chinese philosophy and religion. An elusive figure, he was allegedly a learned yet reclusive official at the Zhōu court (1045–256 BC) – a lesser aristocrat of literary competence who worked as a copyist and archivist. Scholars have variously dated his life to between the third and sixth centuries BC, but he is best known as the author of the classic Tao Te Ching (‘The Book of the Way and its Power’).

According to tradition, Lao Tzu is believed to be an older contemporary of Confucius and the founding figure of Taoism in China. Despite this, many modern scholars doubt the existence of Lao Tzu as a historical figure, and postulate that the Tao Te Ching was written by various authors from the fourth and third century BC. Regardless of Lao Tzu’s historical or mythical status, Taoism is a major school of thought and has been influential throughout Chinese culture, art, and religion.

What is Taoism?

According to Lao Tzu’s teachings, the Tao (Dao), or ‘Way’ is at the center of all life –conceived as the complete totality of existence. The way to mystical freedom is by way of letting go of conventional concerns and achieving union with the Tao. Once union has been achieved, such conditions as poverty and wealth will become meaningless, and ordinary societal values will no longer apply.

The Oxford Companion to Philosophy 2nd edition states that:

Image Credit: ‘Portrait of Lao Zi (Lao Tzu); February 1922, from Edward Theodore Chalmers Werner’s ‘Myths and Legends of China’. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Portrait of Lao Zi (Lao Tzu); February 1922, from Edward Theodore Chalmers Werner’s ‘Myths and Legends of China’. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.“The basic tenet of Taoist thought is that the operation of the human world should ideally be continuous with that of the natural order, and that one should restore the continuity by freeing the self from the restrictive influence of social norms, moral precepts, and worldly goals.”

In essence, Taoism advocates humility, religious piety and harmony with the Tao. Lao Tzu was seen as the living representation of the Tao – bringing salvation and unity into the world.

What is the Tao Te Ching?

The Tao Te Ching (or Daodejing) consists of eighty-one aphoristic and poetic chapters – of what is known today as a mystical, religious, or philosophical text – written by Lao Tzu. It is a work about which there is little agreement. It is a source of Chinese and East Asian reflective traditions, frequently translated into European languages and confusingly subject to diverse and starkly contrasting description and interpretation. It is generally agreed however, that it existed in written form from approximately 300 BC, as the result of earlier oral transmission.

The Tao Te Ching broadly describes the Tao as the source and ideal of existence. It is understood as a series of contradictions; it is unseen, but not transcendent, immensely powerful yet supremely humble, being the root of all things. People have desires and free will (and thus are able to alter their own nature), however many act ‘unnaturally’, thus upsetting the natural balance of the Tao. The Tao Te Ching intends to return its students to their natural state – in perfect harmony with the Dao.

It starts with the classic lines:

The Tao that can be spoken is not the eternal Tao

The name that can be named is not the eternal name

The nameless is the origin of Heaven and Earth

The named is the mother of myriad things

Previous ‘Philosophers of the Month’ have included Jacques Derrida, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Søren Kierkegaard. Why not follow #PhilosopherOTM on Twitter for more philosophy content?

Featured Image: ‘The Three Gorges Landscape China – Yangtze River’ by cq19690527. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Philosopher of the month: Lao Tzu appeared first on OUPblog.

August 1, 2015

Overfishing: a bigger problem than we think

Many of us probably tend to take fish for granted, as it’s a fairly sustainable resource—at least, that’s what we’d like to believe. It’s difficult to imagine that we could even come close to depleting what seems to be limitless; after all, the earth is mostly covered in water. But as Ray and Ulrike Hilborn discuss in an excerpt from their book, Overfishing: What Everyone Needs to Know, there is reason for concern in our flippancy towards our complex ecosystem.

Overfishing is harvesting a fish stock so hard that much of the potential food and wealth will largely slip through our fingers. Yield overfishing is the most common. It prevents a population from producing as much sustainable yield as it could if less intensively fished. The population will typically be less abundant, but it can and often does stabilize in an overfished state. However, with extreme overfishing, in which the forces of decline are consistently greater than the forces of increase, the population would continue to decline and could become extinct.

Economic overfishing occurs whenever too much fishing pressure causes the potential economic benefits to be less than they could be. Many fisheries simply have more boats than needed to catch potential yield, and seasons have become shorter and shorter as more boats enter the fishery and catch the allowable harvest more rapidly. Far more money than is needed to catch the fish is spent on boat repairs, maintenance, fuel, and insurance. For example, governments may have subsidized vessel construction and fuel expenses or large fleets may have developed rapidly when the fisheries first began.

Related to any form of fishing is the ecological or ecosystem impact. Yet in that context there is no “optimal” level because, obviously, the actual number of fish in an ecosystem will decline continuously with increased fishing pressure; thus any amount of fishing can be said to be “ecosystem” overfishing, and to achieve the least possible impact means no fishing whatsoever. In some cases the total number of fish may be higher in a fished ecosystem if we remove important predators. However, any fishing is ecosystem overfishing to those with a focus on natural ecosystems.

But since we need to eat, let’s look at abundance.

There is a relationship between the abundance of fish in an ecosystem and fishing pressure, sustainable yield, profit, and ecosystem impacts. When there is little or no fishing, there is little sustainable yield and precious little profit. As fishing pressure keeps increasing, first the profit peaks and then at higher fishing pressure the sustainable yield peaks. As fishing pressure further increases, both profits and sustainable yield decline. And when that happens we are said to be in a state of biological or economic overfishing. Normally we would expect profits to be highest when the fishery takes less than the biological yield.

Overfishing has been with us since man first started fishing. Even with pre-industrial technology, natural resources could be overexploited, and we know that when humans first arrived in new parts of the world some of the more easily captured species were hunted to extinction. The historical record for fish is not as reliable as it is for land animals, but it is safe to assume that the most vulnerable species bore the brunt of first contact.

The concept of overfishing was already widely discussed in scientific circles in the second half of the 19th century. The British scientist Sir Norman Lockyer used the word in the journal Nature in 1877: “Nor does it seem to me quite worthy of my friend, in discussing the probabilities of overfishing in the sea, to try to prove his case by bringing forward an instance of overfishing in the rivers leading to a smaller supply of food.” That overfishing involves taking too large a portion of a population was well understood by 1900, when Walter Garstang of Oxford University wrote:

We have, accordingly, so far as I can see, to face the established fact that the bottom fisheries are not only exhaustible, but in rapid and continuous process of exhaustion; that the rate at which sea fishes multiply and grow, even in favorable seasons, is exceeded by the rate of capture.

The biology of overfishing is always a question of the “rate at which sea fishes multiply and grow” compared to their “rate of capture.”

As fishing technology got better, our ability to catch fish did, too, but the ability of the fish to multiply and grow stayed the same. Steam- and then oil-powered fishing vessels were the most important technological innovations. Trawl nets, which are dragged through the sea and were small when fishing boats still had sails, got ever larger as the fishing fleets switched to boats with ever more powerful engines after World War II. Other technological advances were made in fishing nets, especially cheap monofilament gill nets that almost anyone could afford. They are made of a near invisible mesh that traps fish behind their gills when they swim into the net. As these nets cost just a few dollars, their use spread around the world. Electronics such as global positioning systems (GPS) and fish-finders allowed fishermen to repeatedly find the same best fishing spots associated with reefs and rocks on the bottom and to do so in the fog.

We now have the technology to overfish almost every imaginable marine resource. The question is, do we have the political will and the social and cultural institutions to restrain ourselves?

Image Credit: Photo by stickfish. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Overfishing: a bigger problem than we think appeared first on OUPblog.

Rivers in distress

A river is a natural, living, organic whole, a hydrological and ecological system. It flows; that is its defining characteristic. As it flows, it performs many functions. It supports aquatic life and vegetation; provides drinking water to human beings, their livestock and wildlife; influences the micro-climate; recharges groundwater; dilutes pollutants and purifies itself; sustains a wide range of livelihoods; transports silt and enriches the soil; maintains the estuary in a good state; provides the necessary freshwater to the sea to keep its salinity at the right level; prevents the incursion of salinity from the sea; provides nutrients to marine life; and so on. It is also an integral part of human settlements, their lives, landscape, society, culture, history, and religion.

Unfortunately, most people think of a river simply as a channel carrying water. It is this limited perception that enables the engineer to regard a river as a pipeline to be manipulated at will, and the economist to regard it merely as the source of a marketable commodity for human use and trade. Abstraction of water from rivers is regarded as ‘use,’ and in-stream flows, particularly flows to the sea, are regarded as ‘waste.’ Industry thinks of a river not merely as a source from which water can be extracted for its use, but also as a drain into which its waste can be discharged. Large farmers want dams and canals to be built for diverting water for irrigation. Agricultural run-off, containing residues of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, pollutes and contaminates rivers and aquifers. Construction workers regard the river-bed as a source for construction material, i.e., sand. Builders, developers, ordinary people wanting to own houses, industry and commerce looking for land, even urban planners and governments, tend to look longingly upon the floodplains of a river as so much land lying unused. Floods with which people in earlier times had learnt to live with and derive some benefit from are now regarded as disasters to be controlled; their destructive power has indeed increased because of extensive occupation of the floodplains.

“Saving rivers will have to be part of saving our world and ourselves.”

The engineering-cum-economic approach is aggravated by what lies behind it, namely the driving force of what has come to be called ‘development,’ meaning the multiplication of wants, the aspiration for ever-rising ‘standards of living,’ and the obsession with ‘growth.’ Driven by that force we genuflect before the twin gods of consumption and production. This is what Mahatma Gandhi called ‘greed.’ His oft-quoted observation may be recalled here: “The world has enough for everyone’s need but not enough for anyone’s greed.” Greed, so defined, doubtless created the spectacular world that we live in (and glorify by the name of ‘civilisation’), but it is also destroying that world; it makes unsustainable drafts on natural resources and at the same time pollutes the air that we breathe and the water that we drink, and devastates our habitat.

The results are there for all to see. Rivers have always been worshipped in India, and yet they are in a deplorable state today. Many rivers in the country are declining or dying. It is difficult to find living, healthy rivers, and even the few that exist are under threat of decline. The decline of the Yamuna is a striking illustration of these trends. The Yamuna is a 1400 km-long river system with around 30 tributaries contributing to the making of what was once a perennial and sacred river that was part of our mythology (the Krishna lore and the Mahabharata epic) and history (ancient cities of Delhi, Mathura and Agra standing on it). Today, the river is no more than a sewer. The water quality of the river in the city at zero (0) Dissloved Oxygen (DO) is so bad that not even a turtle can be found in it against a large number of crocodiles and turtles that the river harboured in early twentieth-century. According to the Central Pollution Control Board, some 3500 MLD (million litres per day) of a toxic cocktail of sewage and industrial waste enters the river in Delhi through some 22 drains entering the river. After an investment of almost Rs 5000 crores in the creation of Sewage Treatment Plants, electric crematoriums, toilets, and ghats at a number of places in Haryana, Delhi, and UP, the position is that the heavily polluted stretch of the river has actually increased from the previous 500 km to the present 600 km from Panipat to Etawah. So, what has gone wrong? Can the creation of more pollution abatement infrastructure in Delhi revive the river? The answer is a clear no.

The existing infrastructure, once made fully operational, will indeed help to some extent, but only if adequate flow in the river is maintained all year. In 1999, the Supreme Court had mandated the maintenance of at least 10 cumec (360 cusec) at all times throughout the river. For 360 cusec to flow in the river at Etawah, where the river Chambal meets and revives river Yamuna, there must be at least 1000 cusec flowing in the river downstream of Delhi. Given human greed, this seems a pipe-dream.

Another matter that deserves attention is the security of the river’s floodplains. Against an expert mandated norm of at least a 5 km-wide floodplain between the embankments, nowhere in the National Capital Territory of Delhi is the available floodplain more than 3.5 km. Clearly, the city is ill-equipped to deal with the flood fury when it strikes the city periodically, as it will. Even this floodplain has been invaded by ill-conceived constructions by public authorities and private agencies, such as the Akshardham temple complex, the Metro Depot, Bus Depot, Commonwealth Games village, and power plants.

Nothing less than a major transformation of our ideas of development and civilisation will save our rivers. Saving rivers will have to be part of saving our world and ourselves. One despairs of seeing such a transformation actually taking place, but its failure to happen will have consequences that no one will want to contemplate, and that gives one a faint hope for the future.

Image Credit: “INDIA” by frederik_rowing. CC By NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Rivers in distress appeared first on OUPblog.

Toilet paradigms and the sanitation crisis in India

Sanitation has evinced considerable interest from policy-makers, lawmakers, researchers and even politicians in recent years. Its transformation from a social taboo into a topic of general conversation is evident from the fact that one of the central themes of a recent mainstream Bollywood production (Piku, 2015) was the inability of the protagonist’s father to relieve himself. While these are welcome developments, the need to urgently address the plethora of sanitation-related issues in India is undisputed. Inappropriate sanitation remains a major cause of water-borne diseases that adversely affect a significant percentage of the population. As a leading cause of water pollution, sanitation is also a key element of any discussion on environmental quality, given the centrality of water to environmental policy debates.

On the positive side, the recent astronomical increase in the visibility of sanitation on different platforms has resulted in sanitation becoming the first key policy initiative of the new government elected at the Union level in 2014. The over-arching Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) adds new dimensions to the sanitation debate and updates certain components of the existing policy framework, as in the case of rural areas. The launch of the SBM, and the enactment of a law prohibiting the abhorrent practice of manual scavenging in 2013 confirm the role of law and policy in addressing the various sanitation-related issues. This is not news to people who have been working in the field but it highlights the importance of legal and policy instruments.

However, there is still little or no clarity concerning the appropriate level and extent of intersection between sanitation and law and policy frameworks. Sanitation has often been and still is reduced to ‘toilets’ and ‘defecation’. This is accompanied by a limited understanding of what the achievement of an ‘open defecation free’ status entails. While these are central concerns, there are other equally important issues that fall outside the mainstream ‘toilet’ paradigm but require immediate attention if the sanitation crisis in India is to be addressed in a holistic manner.

The limited focus of the mainstream sanitation framework is one of the reasons why the law and policy frameworks concerning sanitation appear relatively limited when they are, in fact, very broad. In general terms, such frameworks seek to include (to varying extent): Image: “Slum and dirty river” by meg and rahul. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Image: “Slum and dirty river” by meg and rahul. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Provision of toilets, including sufficient water to service them, and equitable and appropriate access for all;

Provision of proper wastewater treatment and disposal, and sewerage networks, or alternative means to ensure that black water does not contaminate sources of drinking water;

Making the link between liquid and solid waste and provision of solid and liquid waste management;

Consideration of the different needs in rural and urban areas, whether in terms of infrastructure, or environmental or social conditions;

Understanding sanitation as including manual scavenging. (Manual scavenging is a critical sanitation issue that was the first to be addressed in strong legal terms in the Constitution of India. However, the constitutional mandate to eradicate manual scavenging has not been entirely realized yet);

Linking sanitation workers and sanitation, as well as sanitation workers and manual scavenging since rehabilitated manual scavengers are often employed as sanitation workers;

Linking sanitation and health. (The link between sanitation and health is well established in practice but it requires further emphasis in the legal framework);

Linking sanitation, water and environment. (This is important especially in the context of the significant contribution that black water makes to water pollution, itself a key issue affecting environmental quality that can further be linked to health in the context of waterborne diseases);

The piecemeal nature of the existing legal instruments and policy documents need not be a hindrance to resolving the sanitation crisis. If we tackle the knowledge deficit and bring together the various legal and policy dimensions of the issue, we can better ensure environmental quality and public health for everyone.

Featured Image: “Ganges river at Varanasi in India 2008″ by JM Suarez. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Toilet paradigms and the sanitation crisis in India appeared first on OUPblog.

What can we expect at Japan’s 70th war commemoration?

As we approach the 70th anniversary of the end of Japan’s War, Japan’s ‘history problem’ – a mix of politics, identity, and nationalism in East Asia, brewing actively since the late 1990s – is at center stage. Nationalists in Japan, China, and the Koreas have found a toxic formula: turning war memory into a contest of national interests and identity, and a stew of national resentments. “Coming to terms with the past” has now become a quid pro quo of political demands and rebukes – for apology, remorse, compensations, and claims for territories – fueling mistrust and suspicion.

Seventy years have now passed since the end of a war that killed 25 million people in Asia, which will be commemorated on 15th August. Many observers have raised their hopes and expectations that this could be an opportunity to ‘reset’ the history problem. Much could be accomplished, they believe, with a magnanimous political gesture or a statement toward a genuine reconciliation and a better collective future for the region, especially by the head of the Japanese government.

An obstinate hurdle to realizing this hope, which is often overlooked, is that the history problem is also about personal identity. We can better understand the emotional import of the upcoming commemoration on 15th August by recognizing that for many Japanese people, it is about defining the humiliating legacy of our fathers and grandfathers – their mistakes and failures. War memory is ultimately family memory, and the questions are personal: What did our fathers and grandfathers do in the war? Did they act honorably at their time of reckoning? Do we portray them as innocent or guilty? Do we protect or incriminate our own family members? We may be in a better position to anticipate the forthcoming politics of war responsibility at the 70th anniversary by taking account of the family legacies of Japan’s elite politicians.

Hiroshima Dome 1945 by Shigeo Hayashi. CC0 1.0 public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Hiroshima Dome 1945 by Shigeo Hayashi. CC0 1.0 public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Some would like to see Prime Minister Abe renew Japan’s apology in a definitive statement of wrongdoing as Prime Minister Murayama did on the 50th anniversary in 1995. However, this would be a revolutionary statement for Abe. He is the grandson of Kishi Nobusuke who masterminded the growth of colonial Manchuria’s economy, and served as munitions minister in the wartime Tojo cabinet. For Abe to reaffirm Murayama’s statement would be tantamount to redefining his colonial and wartime achievements as dreadful wrongs. Is it conceivable that Abe would be prepared to declare, as Murayama did, that his grandfather pursued a “mistaken national policy, advanced along the road to war, only to ensnare the Japanese people in a fateful crisis, and, through its colonial rule and aggression, caused tremendous damage and suffering to the people of many countries, particularly to those of Asian nations”? Such a statement by Abe would be truly ground-breaking.

Others would like to see Prime Minister Abe renew Japan’s vow for peace, in a definitive statement to “never again” engage in war. This would also be a revolutionary statement for him. It was also Kishi, as Prime Minister in 1960, who cemented Japan’s security alliance with the United States, so that American military power would dominate Asia using its strategic bases in Japan. For Abe, vowing to pursue a pacifist future would be tantamount to repudiating this grand design for Japan’s regional power. He sees the East Asia region as a dangerous neighborhood, and is now railroading new national security laws through parliament, based on a unilateral ‘reinterpretation’ of the pacifist constitution.

It would be a mistake, however, to see Mr. Abe’s statements as a complete representation of Japanese national sentiments. The ‘history problem’ is larger and more complicated than the legacy of elite families who dominated wartime Japan. Ordinary Japanese citizens — the rank and file in wartime — have also inherited war memories, and not surprisingly, they diverge a great deal from those of elite families. Many grassroots families remember the war as devastation – especially in 1944-45 – and have passed those memories to their children and grandchildren. Still others remember the harm that the Japanese military inflicted in Asia and attempt to atone in their own ways. These memories are at the root of Japan’s long standing anti-militarist sentiments and defense of the peace constitution.

With all the attention that will be paid to Abe’s speech making on the 70th anniversary in August 2015, it would be all too easy to lose sight of the broad range of sentiments and opinions that make up Japan’s attitude toward its past. Japan’s neighbors, friends and foes alike, would do well to keep this broader picture in view.

Heading image: Memorial Cenotaph, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park by BriYYZ. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What can we expect at Japan’s 70th war commemoration? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers