Oxford University Press's Blog, page 630

August 13, 2015

Hillary has a point: In defense of empathy and justice

Hillary Rodham Clinton had a point when she recently urged: “The most important thing each of us can do… is to try even harder to see the world through our neighbors’ eyes, to imagine what it is like to walk in their shoes, to share their pain and their hopes and their dreams.”

Yale psychologist Paul Bloom objected that we can’t actually do that (at least not as well as we think we can), especially when our neighbor is someone in a quite different situation or condition—say, a stressed-out single parent, a traumatically scarred war veteran, or an autistic child. Besides, declared Bloom, even if we could fully and accurately feel and see from another’s perspective, empathy is often too narrow and parochial to serve as a moral guide. Far less limited, Bloom asserts, is reason: specifically, the impartial principles and procedures of justice. We should “step back” from empathy and “apply an objective and fair morality,” a “dispassionate analysis” of distressing situations. Bloom has even declared that “empathy will have to yield to reason if humanity is to survive.”

Although like Bloom we defend justice, we also defend a corrected empathy against Bloom’s objections. Bloom goes too far in advocating the banishment of empathy from the realm of morality. We should try, as Hillary urged, to take others’ perspectives. True, our perspective taking won’t be perfect, but does it have to be? As the Oxford philosopher Derek Parfit recently wrote: “Though we could not possibly be the horse we are whipping, or the trapped and starved animal whose fur we are wearing, we can imagine such things well enough for moral purposes.”

Morality is most objective and compelling when justice and empathy align. That is, the moral prescription to act is strongest when victims are both wronged and harmed. Such is the case not only in animal abuse but also in genocide, murder, rape, slavery, child labor, and female genital mutilation (despite its continued practice and endorsement in some cultures). Empathy and justice have a deep partnership. Ideally, the partnership is mutual: perspective taking serves justice (would victimizers in their right mind wish to trade places with their victims?), just as justice serves empathy (does not justice seek the right balance of care?).

But is empathy always a worthy partner? We understand why Bloom wants to banish empathy (except as a diffuse compassion or mere spark) from morality. We have long been concerned with empathy’s limitations. Bloom is right to point out how narrow and parochial empathy can be. A nation’s attention is riveted to the domestic story of a baby trapped in a deep well or a teenager’s disappearance amid signs of foul play; meanwhile, an attempted genocide, the murders of millions in Rwanda or Darfur, is scarcely noticed. Hoffman decades ago called this limitation a bias, a selective attention to the salient and intense distress cues of the immediately “here and now” and “familiar/similar” suffering victim.

Yet we do care about the murder of millions as well, as Daryl Cameron and colleagues recently argued. Hoffman called that limitation “empathic over-arousal.” When Scott Seider evaluated a well-intentioned humanitarian course at a high school, he was surprised to find that the students were less motivated than before the course to do something about the massive suffering. One reason, he concluded, was that the students felt overwhelmed and paralyzed by the size and scope of the problems. They withdrew in a way that Hoffman calls “egoistic drift.” Also, over time we can habituate to suffering (perhaps that’s why many city dwellers just pass by the homeless among them on the streets).

Empathy’s limitations represent a flaw, but not a fatal one. In a way, bias and over-arousal preserve empathy (and society) more than destroy it. After all, if individuals were always empathizing with and trying to help everyone, society might quickly come to a halt. It’s also worth noting that, in relationships in which empathy, love, or role-demands and commitments makes one feel compelled to help (for example, a health care professional), over-arousal may intensify rather than destroy one’s focus on helping the victim.

Still, empathy’s limitations generally need correction if empathy is to be a worthy partner to justice. “Stepping back” refers not only to applying fairness, but also to reducing empathic over-arousal. To combat the problem of compassion fatigue, a health care professional may need occasionally to gain some distance by thinking or looking at something distracting or soothing, or thinking ahead to a planned interlude of rest and recreation. Students in a humanitarian aid course need to be given hope that the massive problems can be shrunk, that they can make a difference.

To correct for empathy’s parochial biases, they can be recruited in the service of helping strangers; one can imagine a stranger as part of one’s family or circle of loved ones. It can happen spontaneously; a man chased down and captured a culprit who had pushed an elderly woman onto subway tracks “because that could have been my mom, that could have been a friend of mine.” Gibbs has incorporated such perspective-taking techniques in his and colleagues’ cognitive behavioral work with offenders. To Bloom’s proscription against thinking “of all humanity as a family,” we ask, why not?

Empathic morality alone may not be enough; we emphasize that empathy and justice are co-primary or mutual. If justice serves empathy, the reverse is certainly also true. Empathy’s limitations are minimized when empathy is embedded in principles of justice. Accordingly, morality becomes more stable, less dependent on variations in the intensity and salience of distress cues from victims, less vulnerable to empathic over-arousal (and under-arousal). It’s true that the trapped baby in the well shouldn’t receive disproportionate attention as millions elsewhere are murdered. Still, let’s not throw out the empathic baby with the limitation bathwater. Indeed, empathy’s limitations can be corrected, in part by justice. The limitations do not warrant a denial of empathy’s moral importance, a banishment of empathy from morality, or a disenfranchisement of empathy’s partnership with justice. We should try even harder to take others’ perspectives, to seek a balance of care. Hillary has a point.

Featured image: Photo by Eutah Mizushima. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post Hillary has a point: In defense of empathy and justice appeared first on OUPblog.

August 12, 2015

In memoriam: Terry Vaughn

Oxford University Press mourns the passing of Terry Vaughn, friend, colleague, and fellow traveler. Terry was a legendary editor whose influence in economics and finance publishing was powerfully in evidence for decades and whose contributions spanned the programs of MIT Press, Princeton University Press, and Oxford University Press. His most important legacy, however, is his family and the network of friends and admirers he leaves behind. As we all struggle to make sense of the enormity and suddenness of this loss, the same sentiments are voiced again and again: “Terry was a great editor but an even better person.“ “Terry was one of the nicest people I met in publishing, such a lovely guy.” “I remember him fondly and with admiration.” “There was such an aura of vigor and eternal youth about him.” Renowned for his passions and varied interests, his self-critical introspection, and his warmth and good will (as well as for a marvelously astute and pithy definition of game theory during an editorial meeting several years ago), Terry was a serious person with an easy laugh and a perpetually bemused air. e were very fond of him and we will miss him greatly.

The post In memoriam: Terry Vaughn appeared first on OUPblog.

Playing God, Chapter 2

From what was said last week it follows that pagans did not need a highly charged word for “god,” let alone “God.” They recognized a hierarchy of supernatural beings and the division of labor in that “heavenly” crowd. Some disturbed our dreams, some bereaved us of reason, and still others inflicted diseases and in general worked evil and mischief. The best policy was to propitiate them by invocations (charms) and offerings. The Greek for what we today gloss as “god” was theós (as in theology), and the same word is present in Engl. en–thus-i-asm, going back to Greek via French. The word from which this adjective is formed means “possessed by a god” (again remembering that in our language and in Classical Greek the word god carried quite different overtones). Being “enthusiastic” might suggest ecstasy (the highest pitch of poetic inspiration) or madness. The line separating the two states was tenuous. A close English analog of enthusiastic is giddy, the epithet going nowadays all the way from “dizzy” to “silly,” while a dizzying speed makes us lose control of ourselves. Giddy is obviously and easily allied to god and thus means “possessed by a god.”

The main problem is not only to find the meaning of the ancient root of the word god but to understand what that word once meant and how it could rise in importance over so many other words for “supernatural spirit.” The word god did not show up in the earliest runic inscriptions, but in the Gothic Bible, translated in the fourth century from Greek, it occurs many times. The translator, Bishop Wulfila, needed an equivalent for theós and, apparently, had no trouble finding it. The word was guþ (þ, the letter called thorn, had the value of Engl. th in thin). Wulfila also needed a word for “(Jewish) temple” and coined the compound gudhus, which, let it be noted, was spelled with a d, rather than with a thorn. His word for “a pagan temple” was alhs. Gothic guþ occurs only in contraction as gþ, evidently, to preserve it from desecration, with a horizontal stroke over it (the same happens in the genitive gþs and the dative gþa).Therefore, we cannot be quite sure what vowel stood between g and þ, but, judging by many words like guda-faurhts “god-fearing” and the form elsewhere in Germanic, it was indeed u.

Ecstatic, enthusiastic, giddy.

Ecstatic, enthusiastic, giddy.Naturally, the God of the New Testament had to be he. But masculine nouns ended in –s in Gothic (so dag-s “day”), while gþ had no ending. The evidence from Old Icelandic is especially telling. The word for “God” sounded as guð (ð = th in Engl. this) and was neuter. Moreover, except in the text of the Bible, where it referred to the Christian God and was therefore masculine, it occurred only in the plural. While masculine nouns in Gothic ended in –s, Old Icelandic masculine nouns ended in -r (for instance, dag-r “day”), but guð never had -r. Gothic myths disappeared together with the rest of Goths’ oral tradition (an irreparable loss; only some items of the Gothic vocabulary give us a glimpse of their ancient beliefs), while from Iceland we have a collections of old songs (both mythological and heroic) and a splendid piece of prose containing pre-Christian myths. Those are The Poetic (or Elder) Edda and Snorri’s Edda.

The gods (in the neuter plural!) are often mentioned in both books, and of course there was no need to speak of God in the context of a polytheistic religion. However, Thor, Baldr, Frey, Loki, and others were not maggots in a multitude (according to legend, dwarfs were created like maggots), but distinct male figures and had to be referred to as such. This was easily done. The Scandinavian gods formed two families: the Ǽsir and the Vanir, so that one god was either an áss or a vanr. We can conclude without any hesitation: the ancient speakers of the Germanic languages had the word for “gods” and used it only in the neuter plural (in this they behaved exactly like the Romans: the relevant word was numen). Those “gods” were not deities in some lofty sense of the term but supernatural creatures, like elves, who, in Scandinavia, formed a special bond with the Ǽsir. Judging by the English word elf-shot, their arrows caused lumbago. The Old English adjective ylfig meant “raving mad”; consequently, sending people mental diseases was also within their power. Last week, I noted that elf is related to the German word for “nightmare.” It is amazing how often our distant ancestors associated derangement with the invisible hostile creatures on the lookout for human victims.

I am now returning to the question about why, when the time came to choose a word for the Supreme Being of the Christian religion, the choice fell on god. But before answering it, we have to look at the efforts by the newly-converted pagans, or rather their clerics, to deal with phonetics and grammar. The Goths and the Scandinavians (assuming that the situation in Gothic at one time was the same as in the North), abstracted the singular from the neuter plural, turned it into a masculine noun, but allowed it to remain without an ending. However, the plural was still needed while speaking about false gods, or idols. Wulfila coined the noun ga-liuga-guþ (ga– is a collective prefix, and liuga– is the root of the verb liugan “to tell a lie”). It also seems that, in principle, he preferred to use þ for the name of God, and d elsewhere, but this rule does not work in all cases with sufficient clarity. Old English clerics, when they spoke of the gods in the Christian context, used the ending of the masculine strong declension.

This is King Alfred the Great, a really great English monarch. The first part of his name means “elf,” testifying to people’s belief in the elves’ might.

This is King Alfred the Great, a really great English monarch. The first part of his name means “elf,” testifying to people’s belief in the elves’ might.The Germans, like the speakers of all the other Germanic languages, distinguished between the nouns of the so-called strong and weak declensions (they still do). Details are of no consequence here, but it is characteristic that the word for “God,” historically belonging to the strong declension, was, in the cases other than the nominative, given the ending of the weak one, typical of some names. Such changes are not rare. In Icelandic, two forms competed: Goð and Guð. The alternation reflects the differences in the pronunciation of this word in two Scandinavian dialects. Much later, for enigmatic reasons, Guð acquired an extra consonant and is now pronounced as Gvuth. God proved to be a hard word to deal with. Compare the Modern English taboo forms for “God” and “Lord”: Golly, Lor’, and many others.

Regardless of the primordial meaning of the sound complex god, one wonders how it was formed. According to the prevailing opinion, Old Germanic guð, an ancient past participle, consisted of the root gu– and the ending –ð; –ð is akin to –d in an English past participle like adore-d. Similarly, in Engl. old and cold, final –d is an obliterated trace of a past participle: the original meaning of these adjectives must have been “nourished” and “frozen.” What then was the meaning of gu-?

Hundreds of pages have been written on this subject, but the answer still evades us. This is not surprising, for we are dealing with an elusive entity. The word for “God” in other languages, such as Greek theós, Latin deus (theós and deus are not related!), and Turkish-Mongolian tengri (the latter means “god” and “heaven”), presents similar difficulties. Only Slavic bog looks transparent, but I am not sure that this transparency is not deceptive. The next chapter will be devoted to the mysterious root gu– and a possible solution of one of greatest mysteries of Germanic etymology.

To be concluded.

Image credits: (1) Orpheus in a Wood by Henri Martin (1895). Public domain via WikiArt. (2) Orpheus by Franz Stuck (1891). Public domain via WikiArt. (3) The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “King Alfred the Great.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The post Playing God, Chapter 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Which Great Expectations character are you?

The characters in Great Expectations are a rather lively bunch; even Orlick, who is (arguably) one of the most foul characters in the book, has a deal of depth that makes us love to hate him. Throughout this season’s reading group, have you ever wondered which of Dickens’s characters you’re most like? Find out whether you’re a Pip, Joe Gargery, Jaggers, Magwitch, or Pumblechook in this quirky little quiz below.

Headline image: Photo by Connie Ngo for Oxford University Press.

The post Which Great Expectations character are you? appeared first on OUPblog.

The hidden side of natural selection

The agents of natural selection cause evolutionary changes in population gene pools. They include a plethora of familiar abiotic and biotic factors that affect growth, development, and reproduction in all living things. For example, the evolutionary future of a plant species’ population is shaped by physical agents such as soil moisture and fertility, and by living agents such as competitors, herbivores, pathogens, and pollinators. All of these agents are components of the external environment that surrounds every individual in nature.

But what about the physiological and biochemical conditions that prevail within an organism’s cells, tissues, and organs? The phenotypic variation available for screening by natural selection results from many developmental events occurring within the growing organism. These developmental processes and the genes that control them indirectly can influence many aspects of individual growth, morphology, and reproductive ability. Hence, natural selection can favor particular combinations of genes that optimize the growth and reproductive (Darwinian) fitness of genetically distinct organisms, mediated by the production of specific regulatory proteins, and other physiologically active metabolites. The selection pressures “derive from the internal dynamics of a functioning organism” as stated by Schwenk and Wagner (2004).

Perhaps more intriguing as hidden agents of natural selection are microscopic symbiotic organisms commonly called endosymbionts that reside within the tissues of many animals and plants. Among the best studied endosymbionts are the fungi known as endophytes that live inside the tissues of most plants. These microscopic fungi exist as tubular hyphae that grow between cells in the host plant’s leaves; many of these fungi are asexual, do not produce spores, and are completely hidden from view unless observed under the microscope (Figure 1). The hyphae grow along with the host and may infect the host’s seeds, thereby being transferred to the young offspring that will eventually emerge when the seeds germinate.

Figure 1. Microscopic view at 400X of hyphae (blue) of a fungal endophyte growing within a leaf of perennial ryegrass. Photo by W. L’Amoreaux, Advanced Imaging Facility, College of Staten Island, City University of New York. Image used with permission.

Figure 1. Microscopic view at 400X of hyphae (blue) of a fungal endophyte growing within a leaf of perennial ryegrass. Photo by W. L’Amoreaux, Advanced Imaging Facility, College of Staten Island, City University of New York. Image used with permission.For endophytes to function as significant internal agents of natural selection, they must elicit distinct effects on the phenotypes of the host genotypes they inhabit. Several fungal endophyte species have been shown to affect growth and reproduction of their host plants in either positive or negative ways. The direction of these symbiotic effects typically depend on both environmental conditions and host genotype. For example, in the widespread perennial ryegrass Lolium perenne (Figure 2), interactive effects of host genotype with endophyte infection have been reported for a diverse set of morphological and physiological traits in the host, such as tiller production, carbohydrate storage, net photosynthesis, dry plant mass, and seed yield. For some host genotypes, endophyte-mediated effects are positive, while for others they are neutral or negative. Thus the effects of external agents of selection in the immediate environment may be modulated by endosymbionts acting as additional, internal agents of selection.

Figure 2. The tiny floral units of perennial ryegrass. The dangling, whitish structures are anthers (~2-3 mm long) with pollen. As a grass, the plant is pollinated by wind and flowers do not produce petals or sepals. The seeds that will develop in these floral units may contain the hyphae of endophytic fungi if the plant is infected. In this way, these hidden fungi can be transmitted from one generation to the next. Image Credit: Lolium perenne L. (Perennial Ryegrass)- cultivated by Arthur Chapman. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2. The tiny floral units of perennial ryegrass. The dangling, whitish structures are anthers (~2-3 mm long) with pollen. As a grass, the plant is pollinated by wind and flowers do not produce petals or sepals. The seeds that will develop in these floral units may contain the hyphae of endophytic fungi if the plant is infected. In this way, these hidden fungi can be transmitted from one generation to the next. Image Credit: Lolium perenne L. (Perennial Ryegrass)- cultivated by Arthur Chapman. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia CommonsAs every student of evolutionary biology knows, the result of natural selection is adaptation of the population to its local environment. This means that organisms will be better able to survive and reproduce in a particular selective environment as they become better adapted to it. But can internal agents of selection result in adaptation of host populations? For some mutualistic interactions involving endosymbiotic microbes, the answer may be “yes”. Mycorrhizal fungi, which are microbes symbiotic with the roots of many plant species, are predicted to show co-adaptation with the host populations they have evolved with. In prairies of the American Midwest, a reciprocal cross-inoculation experiment was conducted with three populations of the dominant prairie grass Andropogon gerardii (big bluestem). The roots of this large species are usually host to species of mycorrhizal fungi that improve its growth and reproduction and may be critical to its dominance in the tallgrass prairie ecosystem. Samples of soil from three prairie sites (Kansas, Minnesota, and Illinois) were reciprocally inoculated with fungi, and big bluestem plants from each population were planted into the different soil-fungi combinations. The researchers reported that root colonization of the beneficial mycorrhizal fungi was always greatest on plants in their usual local soil which contained the fungi normally living there. Generally, plants in local soil (inoculated with the local fungi) also showed greater reproduction compared to plants in soil from non-local sites. Thus, the authors maintained that local plant genotypes responded most positively to the molecular signals sent by co-adapted mycorrhizal fungal communities. This implies that the symbiotic fungi at a site had acted as internals agents of natural selection on the local host population in such a way as to maximize plant evolutionary fitness.

These examples provide evidence that the agents of natural selection are not always overt components of the external environment as is often supposed. Internal conditions within the organism interact with its genotype, affecting growth and development, and also the organism’s reproductive capacity compared to other organisms with different genotypes (i.e, its relative fitness). Symbiotic microbes within the bodies of animals and plants are an important part of this hidden side of natural selection and deserve increasing recognition by evolutionary biologists.

The post The hidden side of natural selection appeared first on OUPblog.

Age-friendly community initiatives: coming to a neighborhood near you?

The saying that “It takes a village” is well known when recognizing the role of communities in promoting children’s health and human development. At the same time, there is a growing worldwide movement drawing attention to how much communities matter for people of other ages—especially adults confronting the challenges of later life.

Efforts to make communities better places for older adults (and potentially for people of all ages) reflect a growing field of research, policy, and practice called “age-friendly community initiatives” (AFCIs). In “Age-Friendly Community Initiatives: Conceptual Issues and Key Questions,” our article for the special issue of The Gerontologist in honor of the 2015 White House Conference on Aging, we define AFCIs by identifying their shared elements as follows:

Where: AFCIs are developed in specific geographical areas, which typically are small in size, such as a municipality, neighborhood, or even a cluster of large apartment buildings.

Why: AFCIs share an emphasis on enhancing older adults’ health and well-being, as well as their ability to age in place and connection to their community.

Who: AFCIs involve stakeholders who represent diverse sectors that influence the lives of older adults, such as service providers, transportation authorities, local governments, and private citizens.

How: AFCIs use a range of methods to make social and physical environments better for older adults, such as facilitating community needs assessments, creating new interorganizational partnerships, developing coalitions, and engaging volunteers.

Despite these similarities, an AFCI in one locality is likely to appear quite different from that in another. This is in part because AFCIs are purposely designed to be responsive to the challenges and opportunities that are most relevant to their geographic areas. For example, whereas affordable housing and service accessibility might be key issues for older adults in one community, social isolation and safe mobility might represent the most pressing needs in another community. AFCIs are also likely to appear different from each other because various models and networks have developed in a largely decentralized manner over the past several decades, each with a somewhat unique “flavor.” For example, some models heavily emphasize the built environment and the involvement of local government, whereas other models are more grassroots and focus on engaging the participation of older adults themselves.

Image by OpenClipartVectors. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image by OpenClipartVectors. Public Domain via Pixabay.While there are many examples of AFCIs in the United States in this searchable database, AFCIs remain more the exception than the rule when considering the country as a whole. Therefore, the primary aim of our article was to pose key questions regarding the expansion of AFCIs. We formulated these questions to accelerate research, policy, and practice on AFCIs:

What public policy support is necessary for AFCIs to flourish in diverse communities? To date, there has been limited federal support for the initiation and maintenance of AFCIs. Most public funding has been from state and city governments, and many models have been championed by private philanthropies. Given the investment of resources necessary to develop meaningful community change over time, as well as concerns that communities with the greatest existing resources are the ones most likely to implement AFCIs, public policy at the national level has the potential to more rapidly and equitably expand AFCIs. (For example, Promise Zones are a federal initiative aiming to spur community change on behalf of younger families).

How can advocates engage entities traditionally outside of the field of aging to collaborate on aging-related issues and joint agendas? At their core, AFCIs focus on cross-sector collaboration to address persistent challenges and opportunities related to population aging. However, fragmentation across professional practice, academia, health and social services, government, and philanthropy render it difficult to develop a widely shared agenda around aging. Better understanding of how to overcome these challenges and address ageism at the societal level would be helpful in efforts to expand the implementation and effectiveness of AFCIs.

How can the individual- and community-level outcomes of these initiatives be rigorously evaluated? Despite continued enthusiasm for AFCIs, there has been relatively little systematic examination of whether they yield desired outcomes among older individuals and others. More rigorous evidence regarding the extent to which AFCIs achieve their intended goals would strengthen advocacy for greater investments in AFCIs, especially in terms of public dollars.

Despite these challenges, persistent interest in AFCIs in the United States and other countries suggests that these models are intuitively appealing for addressing key issues for our aging world. By continuing to advance discussions on AFCIs—in academic journals, professional publications, policy briefs, newspaper articles, and even at dinner tables—we as a society can more deeply recognize how aging well is not simply a matter of meeting individual needs, but also transforming communities for the potential betterment of all.

Image Credit: Photo by Joe Mabel. CC BY SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Age-friendly community initiatives: coming to a neighborhood near you? appeared first on OUPblog.

Eroding norms in reinsurance trading: Can it cause industry collapse?

In the face of severe disasters, or ‘Acts of God’, society turns to reinsurance. It is a financial market that insures insurance firms, and thus trades in large-scale disasters. Reinsurance is therefore the backbone for economic and social recovery in times of unimaginable losses, such as Hurricane Katrina or the attack on the World Trade Centre, through enabling insurers to pay their claims. However, rapid and escalating changes are eroding fundamental norms and practices in this important industry.

How does such a unique and important market function? Through an ethnographic “fly on the wall” study we observed the foundations of reinsurance trading: sitting alongside underwriters as they evaluated risks and allocated large amounts of capital. Reinsurance has developed specific trading practices and norms that differentiate it from the majority of other financial markets. One key norm is that in reinsurance pricing cycles do not represent boom/bust dysfunction. Rather in reinsurance trading they enable long-term stabilizing of capital through payback after loss. Since the cost of a risk remains unknown until a disaster strikes, the payouts to restore order post-loss can outweigh the premiums reinsurers receive for offering protection pre-loss. The more severe the event, the higher the required payout and thus the more prices might increase the following year to make payback to the reinsurance firms. Following particularly expensive disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina, the price of all reinsurance cover will increase worldwide to reflect the loss to the reinsurance purse across the industry as a whole. This allows “payback” to the reinsurers to rebuild their capital and adjust pricing to reflect the cost of the risk involved. Such norms mean that pricing cycles between hard (high-priced, post-loss) and soft (low-priced, no-loss) markets. These cycles enable capital to be stabilised through long-term relationships in which reinsurers have an incentive to pay claims and continue to underwrite risks following a loss, rather than abandoning their clients or suspending claims payments in long legal disputes.

Post Hurricane Katrina Mississippi, by karl.bedingfield. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

Post Hurricane Katrina Mississippi, by karl.bedingfield. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.What is changing? Several factors affect the current norms and practices. As large insurers have consolidated they have changed how they buy reinsurance. These large global insurers are buying less insurance generally, as they have become aware of the capital efficiency and diversification benefits inherent in their own global portfolios. In addition, new types of Alternative Risk Transfer products such as Catastrophe Bonds are increasingly prevalent and increasing. These new products are associated with new players such as hedge and pension funds entering the reinsurance market alongside traditional reinsurers. Such players operate on a different and, as yet, poorly understood array of social norms for pricing risks and paying claims. In essence, it is a time of unprecedented change.

What is the impact of these changes? While the exact implications of these changes are unclear, it is already apparent that market pricing cycles are historical rather than current features of the reinsurance market. Warren Buffett warned of an ongoing slump in reinsurance results as new investors and financial products enter the market: “It’s a business whose prospects have turned for the worse and there’s not much we can do about it”. This new reality was apparent in our observations of the industry in 2011. Despite being the second costliest year on record for the reinsurance industry a hard cycle whereby prices increase significantly – as they did following large disasters such as Hurricane Andrew in 1992 – did not eventuate. Rather, the new sources of capital, new products, and the ability for large, diversified insurers to retain more risk showed its effects; the payback of a hard market through which reinsurers typically recoup losses did not follow. That is, the old mechanisms of market cycles by which capital stability was enabled over the long term, have been eroded by the new competitive dynamics. While low prices help to keep the costs of primary insurance down, they may also have devastating effects if reinsurers are unable to build sufficient reserves and returns to pay claims following disasters. At the same time, the novel products offered by non-traditional players and the new industry dynamics have yet to prove their merit in ensuring capital stability and payment of claims.

Japan 日本 March 2011 — Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami by dugspr — Home for Good. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr.

Japan 日本 March 2011 — Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami by dugspr — Home for Good. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr.What are the knock-on effects of change? Eroding of market cycles removes the incentives for long-term relationship-based trading, through both difficult and good times, so potentially also has a domino effect on claims payments and policy renewals. Long-term trading relationships have long had primacy within the reinsurance industry. Reinsurers had an incentive to maintain relationships and pay claims quickly post-loss, keeping capital liquid, as they would also be reimbursed post-loss by the hardening market cycle. As market cycles, which are fundamental to long-term trading relationships erode, a more opportunistic and price-sensitive basis to trading is emerging. As a reinsurance executive explained during one of our interviews, the industry is:

“… going through a shift in mindset. If margins are huge we can always play the relationship game because both of us will win […] One year you might have a loss but you will make it up in three or four years, so we just stick together. If margins get thin…things become more opportunistic on the insurance but also on the reinsurance side […]. There’s not enough margin there to say yes it’s OK, in a few years we’ll all be in the black again …. It’s not going to happen.”

The question of whether reinsurance pricing is cyclical is therefore closely linked with whether or not it is a relationship-based business.

So, do these changes really matter? Evidence suggests that fundamental norms and practices at the heart of the reinsurance market are eroding. We do not yet know the full implications of these changes. While the industry will surely adapt and survive, it is critical to remember its central “job” of ensuring capital flows to those who need it to rebuild, socially and economically, following large-scale disasters. A starting point is awareness that the proven norms and practices that have enabled the industry to function through major disasters in the past are changing rapidly, with implications that are poorly understood.

Headline image: Hurricane Irene (NASA, International Space Station, 08/26/11) by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Eroding norms in reinsurance trading: Can it cause industry collapse? appeared first on OUPblog.

August 11, 2015

How to write a compelling book review

Summer is a time when many of us have a little extra time for reading. For me, that means Go Set a Watchman, some Haruki Murukami and James Lee Burke, plus summer mysteries and thrillers. It means catching up on what local authors and friends have published. And it means reading new books in my field and writing book reviews.

Book reviews are an essential but unappreciated genre. Reviewing is much more than service journalism. Book reviews are the first thing I look at in the Sunday paper, the first section I turn to when I get the latest issue of an academic journal. For publishers, reviews are an important way of getting the word out about books they believe in. For authors, reviews are much needed feedback, giving them both a sense of how their peers view their argument and validation that their work has not gone unread. For book reviewers themselves, writing reviews is an exercise in thinking about other peoples’ thinking and writing about other peoples’ writing.

How do you review several hundred pages of someone’s blood, sweat, and tears in just the 500 or 1,000 words allotted to you by an editor? Of course, it depends on the book—novels, anthologies, nonfiction, and reference books all have different constraints. But there are some general principles that will make reviewing something you can look forward to.

“Books and Laptop” by Kathleen Zarubin. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Books and Laptop” by Kathleen Zarubin. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.First, pay attention to the deadline and length guidelines. Authors and publishers count on timely reviews—reviews that appear when the book is new. And editors have space limitations, even online, so you can speed things along by following guidelines.

Leave yourself plenty of time, so that you can read the book a couple of times. Give it a quick skim, then a careful perusing (in the older sense of the word), carefully reading a chapter a day and taking notes. That gives you plenty of time to form an impression and think your evaluation through. What is the author’s point and who else cares about it? Did the author win your confidence? Overexplain? Preach? Drift? Was the exposition at the right level, well-supported and exemplified? Was the narrative propulsive and the characters and dialogue convincing? Pro tip: As I read nonfiction, I also take notes about things I might want to mention in classes or research ideas to follow up on later.

Your job is to create a relationship between the reviewer, the book’s author, and potential readers. To do that, you need to establish some context for the book. The best reviews quickly situate a book against some social, scientific, cultural, or disciplinary backdrop. A clever title or opening line helps, but it’s more than that. What important ideas or questions does this book address? Who would be interested in the book and why? A good review can amplify that background for readers and may even cause the author to think about the work in a new way. The opening of a Washington Post review of Allan Metcalf’s book, OK: The Improbable History of America’s Greatest Word reads: “Probably there are as many theories about the origins of ‘OK’ as there are theorists to expound them…” If I am interested in that question, I’ll read on.

Keep in mind that a review is also part summary. Sometimes a chapter-by-chapter summary is helpful, especially when the book is organized as an unfolding nonfiction exposition, historically or thematically. But often chapters can be grouped together more holistically (as you would in summarizing a fictional narrative), allowing you to more quickly focus on the cross-chapter theme an author raises rather than strictly on the exposition.

As you summarize, try to fit the best examples from the book into the review, rather than just relying on a retelling of an author’s points. Try to refer to the material that brought the book alive for you, juxtaposing different examples to reinforce your reading of the book. Ben Zimmer’s New York Times review of Green’s Dictionary of Slang gives the flavor of the work itself by including the following examples in his piece: booze, crib, punk, and skeeve. Similarly, if you review an anthology or collection of essays, you have just enough space to discuss a few pieces in depth and will need to briskly note most of the others.

Summary, however it is handled, should be combined with your evaluation of the book. This is your honest judgement of what parts of the book are the strongest and the weakest. Where does the writing sparkle? Where does it lose its way? What might there be more of, or less? What is innovative and what is missing? Who is this book intended for, and who should pass it by? Give the reasons for your judgement, insofar as you can, and avoid being snarky. One of my professors, the late Samuel Levin, joked that he once wanted to begin a review saying, “This book creates a great void in the field.” But he didn’t. Book reviews are not the place for gratuitous put-downs (for example, “This is not a book to be tossed lightly aside. It should be thrown with great force” or “The covers of this book are too far apart.”)

Book reviews are the time to practice the art of brevity and to polish your own writing. You will probably only have a few hundred words, so make each one count. Engage your readers by getting their attention and winning their confidence, by moving briskly through what you have to say, and helping them to decide if they want to read the book for themselves.

Book reviews can lead to other review-like writing. You may find yourself asked to do a longer review article, basically a review of two or three books on the same topic. That’s your opportunity to put similar books in touch with one another and offer a more extended discussion on both the books and the topic. Another opportunity is the bibliographic essay, like those of Oxford Bibliographies . Here, writers survey the literature of an entire area: phonetics, dialectology, aphasia, you name it. The summary and evaluation aspects are concise annotations, while the background context takes place in paragraph-long overviews. For the bibliographic essay, the exciting challenge is to share your expertise with those who may be new to something, helping them to see the whole and establish a plan for further reading.

Following directions. Planning. Context. Summary. Evaluation. Your best writing. Those are the fundamentals. Book reviewing, like book writing, is a lot of work. But it matters to writers, readers, and publishers, and it is well worth the effort. Even in the dog days of summer.

Image Credit: “Library” by Stewart Butterfield. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to write a compelling book review appeared first on OUPblog.

Wendell Willkie: a forerunner to Donald Trump

It is the stuff of political legend: facing a bevy of prominent candidates within the Republican Party, a straight-talking businessman comes out of nowhere to wrest the GOP nomination away from the party’s customary leadership. Energizing volunteers from across the country, the former executive capitalizes on fear about the international situation to achieve a stunning, dark-horse victory unique to American politics. At the Republican National Convention, the galleries rocked with the name of this suddenly charismatic figure. Is this the scenario for Donald Trump? It worked for his predecessor, Wendell Willkie from Elwood, Indiana, a man now largely forgotten except to specialists in political lore.

1940 began as President Franklin D. Roosevelt seemed unlikely to run for a third term, an assumption that apparently offered an opportunity for the resurgent Republicans. The declared GOP candidates included Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio, Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan, and the thirty-seven-year old district attorney of New York City, Thomas E. Dewey. Because of Dewey’s youth, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes quipped that he had thrown his diaper into the ring. None of the three front-runners departed from the isolationist orthodoxy that dominated their party in the last months of what was known as the “phony war” in Europe, where neither the Allies nor Nazi Germany had yet taken the initiative. Building on their victories in the 1938 elections, the Republicans hoped to return to national power and keep the United States out of the European conflict.

“Wendell Willkie.” Public Domain via the Library of Congress.

“Wendell Willkie.” Public Domain via the Library of Congress.Then matters changed. Hitler invaded the Low Countries and then defeated France with stunning suddenness beginning in May 1940. To Eastern Republicans, mindful of the Nazi threat, the prospect of Taft, Dewey, or Vandenberg seemed dismaying. They wanted an alternative choice who would dismantle the New Deal, but also defend the nation against Germany. Their eye soon fell on a former executive of a public utility, Commonwealth and Southern Corporation. Its former president Wendell Willkie was forty-eight and, up until then, a conservative Democrat. He had clashed with Roosevelt over the Tennessee Valley Authority and he spoke out in defense of large corporations. He appealed to business executives and GOP opinion makers along the East Coast.

Soon, thoughts within the party turned to the burly, rumpled Willkie whose ad lib speeches excited crowds. Here was a candidate for eastern Republicans who was an opponent of parts, but not all of the New Deal. On foreign policy, Willkie said, “it makes a great deal of difference to us—politically, economically, and emotionally—what kind of world exists beyond our shores.” Suddenly, Willkie seemed more exciting to Republicans than the blandness of Taft and the evasions of Dewey.

Seventy-five years ago, it was still possible for a candidate such as Willkie to seize the nomination. There were fewer primaries than today and the party structure was more fluid. Because there was no clear front-runner, Willkie divided and conquered. “Willkie for President” clubs sprang up across the nation. Every down-tick in the international news made Willkie more appealing. By the time the Republicans met in Philadelphia, the Willkie bandwagon was rolling. The crowds in the galleries chanted “We want Willkie,” and the delegates yielded to what seemed an irresistible tide.

Alas, Willkie’s campaign peaked the day he was nominated. In his acceptance speech he referred to “you Republicans.” A wag likened the disorganized Willkie campaign to “a whorehouse on Saturday night when the madam is out and all the girls are running around dropping nickels in juke boxes.” By October, with the polls showing him behind the president, Willkie played the isolationist card. “Our boys shall stay out of Europe.” Roosevelt countered with famous assurances that “your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign war.” When he heard Roosevelt’s words, Willkie said, “That hypocritical son of a bitch! This is going to beat me.”

And so it did. Roosevelt beat Willkie by five million votes and 449 to 82 in the Electoral College. The businessman candidate had not won. Conservatives argued that by picking a moderate choice, the party had sold out its heritage for nothing. Willkie was no Donald Trump; he had ideas and the ability to engage tough issues. Could any Republican have won in 1940 against a still healthy FDR? Probably not, but Willkie gave it his best shot. Perhaps there is room in the crowded Republican field for another charismatic newcomer from the world of business who can, for a season, capture lightning in a bottle as Wendell Willkie once did.

Image Credit: “Wendell Willkie’s notification ceremony, Aug. 17, 1940″ by Charles J. Bell. Public Domain via Library of Congress.

The post Wendell Willkie: a forerunner to Donald Trump appeared first on OUPblog.

A prescient voice on climate change

Everyone knows that in June 1962, Rachel Carson published a series of articles that became Silent Spring, the eloquent book that launched the American environmental movement. But far fewer know that in the same month a second American author also raised the alarm about the threats posed not only by the growing use of chemicals, but also by a wide range of environmental ills emerging in those years.

Industrialized agriculture, with its broad use of chemicals, constituted a threat to human health, argued Murray Bookchin (1921-2006) in his first book, Our Synthetic Environment (published by Knopf in June 1962, under the pseudonym Lewis Herber). Crops grown in monocultures were vulnerable to infestations, requiring pesticides; and pesticides like DDT were linked to degenerative diseases, even cancer. Meanwhile cities too were becoming toxic. Pollution was choking the air and waterways. City dwellers, toiling in a deadening monoculture of uniform glass-towered offices, were subject to high levels of stress, deprived of fresh air and sunlight, their walkable streets displaced by the soot-spewing automobile. And finally, nuclear power posed the unprecedented threat of radiation.

Our Synthetic Environment not only warned about these problems; it indicted the social and economic system that generated them. One reviewer, William Vogt, noted that Bookchin “ranges far more widely than Miss Carson and discusses not only herbicides and insecticides, but also nutrition, chemical fertilizers […] soil structure.” The British periodical Mother Earth called Our Synthetic Environment “one of the most important books issued since the war and I thoroughly recommend it to all who are interested in the way we live.” The eminent microbiologist René Dubos lauded both Our Synthetic Environment and Silent Spring for alerting the public “to the dangers inherent in the thousands of new chemicals that technological civilization brings into our daily life.”

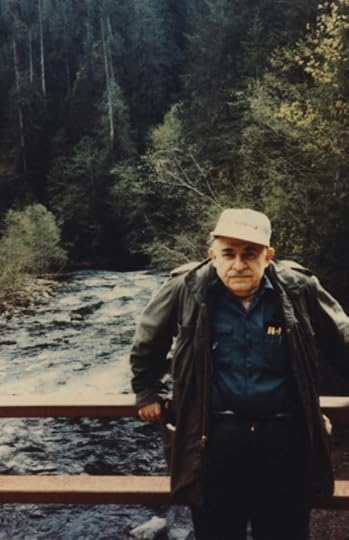

Image Credit: Murray Bookchin poses in 1988 in the Pacific Northwest by Janet Biehl. Used with author’s permission.

Image Credit: Murray Bookchin poses in 1988 in the Pacific Northwest by Janet Biehl. Used with author’s permission.Why was the book mostly overlooked? One reason was surely the fact that its author was a political radical, a former Communist turned anarchist, whose natural métier was broad social analysis. As the culture critic Theodore Roszak speculated a decade or so later, “the staggering breadth and ethical challenge of Bookchin’s analysis” was overwhelming: “Nobody, as of 1962, cared to believe the problem was so vast. Even the environmentalists preferred the liberal but narrowly focused Carson to the radical Bookchin.” Moreover the remedy Bookchin offered was social revolution, and as the environmental writer Stephanie Mills noted a decade or so later, that was “too much for people to swallow in ’62.”

Unfazed, Bookchin went on in his next book to wrestle with an even larger problem. Crisis in Our Cities, published in 1965 (also under the Lewis Herber pseudonym), was mostly a study of urban ills. But in the closing chapter, he explained that “man’s increased burning of coal and oil is annually adding 600 million tons of carbon dioxide to the air. […] This blanket of carbon dioxide tends to raise the earth’s atmosphere by intercepting heat waves going from the earth into outer space.” Now, Bookchin wasn’t a climate scientist—his information source was a brief article in a scientific journal. But the consequences were clear: rising temperatures that would disrupt the climate: “Meteorologists believe that the immediate effect of increased heat leads to violent air circulation and increasingly destructive storms.” Bookchin took a daring leap to suggest that “theoretically, after several centuries of fossil-fuel combustion, the increased heat of the atmosphere could even melt the polar ice caps of the earth and lead to the inundation of the continents with sea water.”

His specific predictions were remarkably accurate, except for the long-range time frame. Rising atmospheric temperatures: check. Violent air circulation: check. Increasingly destructive storms: check. Melting polar ice caps: check. Inundation of the continents with seawater: coming.

Bookchin correctly diagnosed the cause of the looming problem: the burning of fossil fuels. Indeed, “we could not hope to sustain our fossil-fuel technology indefinitely even if there were ample reserves of coal and oil for millennia to come.” So the agenda, he said (still in the 1965 book), must be to shift to alternative sources of energy. “Every day, the sun provides heat energy to each acre of the earth’s middle latitudes in amounts that would be released by the combustion of nearly three tons of coal,” he observed. “If we could fully utilize the solar energy that annually reaches the continental United States, we would acquire the power locked in 1,900 billion tons of bituminous coal!” But unlike coal, energy derived from the sun would be “clean and inexhaustible.”

Wind power would be another clean source: we could “harness the winds for producing electric power at costs that are competitive with fossil fuels.” And finally we could use energy from tides: “sea water will be trapped behind the dam as the tide rises and will then be rereleased as needed into generating turbines.” From these disparate sources, Bookchin suggested piecing together a system “in which the energy load is distributed as broadly as possible.”

He dared to say in the mid-1960s what many today are acknowledging: that the root cause of climate change is capitalism, a system that compels firms to lay waste our common home in order to survive. The incipient greenhouse effect “is symbolic of the long-range catastrophic effects of our irrational civilization on the balance of nature.” To preserve the viability of the biosphere, he argued, we must rethink our economic system and create a “moral economy,” one that places the common good ahead of the unshackled profit motive, within the boundaries of the natural world.

For the rest of the twentieth century, he would profound his visions of a decentralized, humane, cooperative ecological society: in the 1960s to the New Left; in the 1970s to the antinuclear movement; in the 1980s to the Green movement; and in the 1990s to radicals dislocated by the fall of the Soviet Union. He was a genuine original, a prescient thinker who worked out solutions to problems before most people realized they existed. His message has only become more relevant today.

Feature Image credit: New York City pollution in 1967 by John Atherton. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A prescient voice on climate change appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers