Oxford University Press's Blog, page 631

August 11, 2015

Frank Wijckmans speaks to the Oxford Law Vox

In the sixth instalment of the Oxford Law Vox podcast series, competition law expert Frank Wijckmans talks to George Miller about cartels and EU competition law. Frank is an editor, alongside Filip Tuytschaever, of Horizontal Agreements and Cartels in EU Competition Law, and he covers the key themes of the book in his conversation with Law Vox.

Frank begins by addressing the position of cartels in the broader landscape of EU competition law, and its place as a top priority for public enforcers. He also discusses the challenges faced due to the variety of phenomena and practices that are embraced by the term cartel itself, particularly for businesses.

“A number of practices would not naturally feel as being a cartel. And that goes all the way from things like information sharing for instance. When you start exchanging information with a competitor, that information can influence future prices, future volume, your future products, your future strategies. Before you know it you are in a cartel environment, and information sharing is almost inherent in business. So the borderline between being on the safe side and being on the wrong side of the line, that borderline is very difficult to draw, and that’s the big challenge for business at the moment.”

Frank moves on to discuss the inherent difficulties for practitioners when establishing cartel cases in complex circumstances, and highlights the tools that are available in regards to leniency and acquiring evidence. Frank also comments on the reactive nature of the approach authorities are taking when investigating cartel cases.

“What you see is that when leniency applications go in, and the authorities find them sufficiently compelling, is that there are follow up investigations. What you also see by the same token is that in certain sectors there is now a focus from the authorities, once the first case bursts out, in the same sector. People start looking harder in neighbouring sectors and neighbouring markets, at similar practises going on.”

The unique aspects of Horizontal Agreements and Cartels in EU Competition Law are also discussed. In particular, Frank explains how the book provides practical advice for lawyers in the field by juxtaposing perspectives from both private practitioners and public enforcers in each chapter.

“We’ve not asked the authors to criticise each other’s bits, but rather take the perspective of the practitioner. If you are to advise a company, if you are to advise your fellow lawyers handling this particular theme, what are the major mistakes? What are the booby-traps? What are the points of attention? Where, based on your experience as a practitioner, or as an enforcer, can you add value? And that’s what I hope you see in the book.”

Other topics are also explored, including debates surrounding fining regimes, recidivism, and successor liability. Looking to the future, Frank concludes by commenting on what he believes are the key areas to focus on in the next few years.

“First of all – private damages. It’s the area which is going to develop most in the coming years. The member states have been given two years to implement the directive which means that by the end of 2016 every member state will have to have an enacted its proper law facilitating these kinds of claims. It remains to be seen how member states will do that. In terms of case law, we’re monitoring constantly, particularly what comes up out of Luxemburg. The commission cases are forming a certain pattern, but it’s particularly Luxemburg that is setting the scene.”

You can hear the rest of Frank Wijckmans’s insights on cartels and competition law by listening to the podcast on Soundcloud.

You can also learn more about Horizontal Agreements and Cartels in EU Competition Law in Frank’s video introduction to the book on YouTube.

Featured image credit: FFM Skyline, by Carsten Frenzl, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Frank Wijckmans speaks to the Oxford Law Vox appeared first on OUPblog.

August 10, 2015

Are you ready to travel?

There’s more to international travel than booking a flight, finding a place to stay, and figuring out transportation. When traveling internationally, it is important to pay attention to the different vaccinations and immunizations that are required or suggested. Keeping yourself and your travel companions safe should be a top priority when preparing to go on a trip to another country. Are you ready to get on that plane? Test how much you know in our quiz below.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Image Credit: Travel via Moyan Brenn. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Are you ready to travel? appeared first on OUPblog.

Ecologists, drunkards, and statistics

“Statistics,” as an old saying has it, sometimes “are used much like a drunk man uses a lamp post: for support, not illumination”. This sounds bad, but is it? And if so, why?

Scientists sometimes use statistics to support an argument because statistics appear to lend authority that otherwise may seem lacking. It may seem more convincing to mention p-values (or DAIC’s, or what have you) for quantitative statements that are clearly sound; for example, if there are two treatments with 50 individuals each, and in one group 40 reach maturity while in the other group only 10 do, a significance test comparing the treatments provides no new information. But sometimes editors or reviewers require such tests. This excessive use of statistics may make research sound falsely authoritative – and we think it should be avoided – but the harm is just that it can make it harder for readers to see the essence of research because there is so much science-y sounding stuff in the paper. Bad, but not necessarily terrible.

There have been big changes over the last decade or so in the way ecologists practice statistics. For example, we focus much less on null hypothesis significance testing and much more on estimation and on model selection. This entails an awareness that statistical analyses are modeling tools, and that in doing statistics we are looking for useful, well-supported, models of reality. This is often a somewhat more natural way of thinking than hypothesis testing, with its focus on asking what the probability of a more extreme test statistic is, if the (often certainly untrue) null hypothesis were true. This shift to model-centered statistics has facilitated our ability to move from requiring that all data be independent, to including correlated data structure in our models. Generalized linear mixed models, spatial models, and many other useful tools have gained acceptance as a result.

Several years ago Brian McGill warned of “statistical machismo” in ecology, suggesting that ecologists waste effort by using statistics that are more complicated than necessary. That may sometimes be a problem, but we think the bigger problem from using excessively complicated statistics is the potential for falsely convincing others (and ourselves) that our scientific argument is stronger than it really is. A second reason drunkards sometimes cling to lamp posts – we suppose – is that they think they can hide the instability of their strides. And sometimes they probably can, for a while. Scientists sometimes may do something similar: we use statistics to hide the instability of our arguments. When this occurs, the big problem is not that some effort is wasted, or that macho individuals swagger and boast about their statistics; the larger problem is that scientific conclusions may appear to be better supported than is warranted.

It may be inevitable that scientists rely on statistics for support in both senses – stabilizing shaky arguments as well as lending authority to them. After all, we need statistics partly because our ability to reliably discern pattern in a noisy world is quite limited. In this sense, hanging on to some external support can be part of a sensible strategy. But if you rely too strongly on external support – a lamp post or a flashy statistic – to do something, that is inherently weak or unstable, then you are eventually likely to wind up on the ground, injured and embarrassed.

Image credit: Forest in Belgium by Donarreiskoffer, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Forest in Belgium by Donarreiskoffer, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.How can you reduce the frequency with which this occurs? Prior to beginning new statistical analyses, be certain of your conceptual understanding of the methods you intend to use. How do the statistical models relate to the scientific questions you wish to address? While there are often many methods to choose from for a particular data analysis, each one asks questions that are different, and the resulting statistics have different meanings. In switching from one model to another, we may find that we have a more tractable statistical question, but are addressing a different scientific question. While we do not think that every ecologist must know the mathematics underlying the statistics they use, you really must understand the models you use in a qualitative way. A useful rule of thumb is to ask whether you can explain your statistical methods to a scientist untrained in them.

What resolution does your analysis require? Ecology is complicated, and many different things may determine outcomes – but that doesn’t mean that they must all be part of your statistical model. For example, if you are studying individual growth rates of trees, some scientific questions may be adequately addressed by considering a few physical factors, like moisture availability or soil nitrate concentrations. Some questions might require that you also consider density of neighbors. Still, other questions might require that you consider how closely related those neighbors are. But which of these factors are actually needed to address the questions of interest? Using more complex statistics is not a virtue by itself; if older methods like linear regression are adequate (and appropriate, given the data), use them!

Useful empirical research involves coherence between three things: data, statistics, and mechanistic explanation. The statistical part involves more than underlining statements about observed patterns with something like “p < 0.0001;” it involves modeling the data, and sometimes modeling the underlying biological process thought to generate the data. Publishing meaningful research – as well as interpreting others’ research – requires a clear conceptual understanding of the models. The alternative is believing things we really don’t quite understand, and as Stevie Wonder once put it, “When you believe in things you don’t understand, then you suffer. Superstition ain’t the way.”

Feature Image credit: Lamp post by MichaelMaggs. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ecologists, drunkards, and statistics appeared first on OUPblog.

Urban heat islands – What are they and why are they a big deal?

The recent brutal heat waves on the Indian subcontinent, in western North America, and in western Europe are instructive reminders of an often forgotten challenge for an urbanizing human population in a warming world: alleviating urban heat stress. Cities are durable and costly to change, so what we do now to reduce risk in a future with more numerous and more dangerous heat waves that will directly affect future generations. Why is this topic important to focus upon now?

Humans are rapidly moving to cities. As human populations urbanize and the planet warms, the effects of urban heat islands (UHIs) will become more important to our societies. Warmer cities will cause increased human discomfort, require more energy to cool building envelopes, increase air pollution which degrades human cardiopulmonary health, and use more water to keep vegetation alive.

UHIs are a phenomenon of much warmer temperatures in cities than in the surrounding landscape; the increased temperatures are caused by unshaded buildings and pavement reflecting, absorbing and storing the sun’s energy – cities are hotter during the day from reflected heat and warmer at night due to the stored heat in pavement and buildings.

Emergency managers, regional organizations, national governments and adaptation professionals across the world are starting to prepare local climate adaptation plans that include strategies to mitigate UHIs in a future world with stronger heat waves. It will be important in a warmer world to plan for the fact that crowded cities need to maintain (and increase) vegetation to create shade and cool the surrounding air by evapotranspiration. Cities need to ensure cooling breezes flow through, scouring out heat and air pollution. Cities need to have places for at-risk people to go when their dwellings become too hot to bear during heat waves. And cities need to ensure that new buildings are well-insulated against added heat. Planning for uncertainty and many moving parts in cities is a challenging task. Is there anything you and I can do to help alleviate the UHI?

It turns out that human preferences for a certain type of landscape help with reducing the effects of the UHI. Environmental psychologists hypothesize that our landscape preferences come from the vegetation types found in the African savanna where early hominids evolved: scattered tall, spreading trees, some understory plants, and grassland. Now look around at the vegetation in nice neighborhoods: tall trees (but not too many), some understory plants (often flowering), and turfgrass. The very landscape types that humans prefer can help cool cities. The value of a large shade tree goes beyond shading your dwelling and keeping it cool – large, healthy trees raise the property values of the area, greenery is restorative, and many trees in a neighborhood induce us to get out and go for a walk. Designing cities with these needs in mind has multiple, reinforcing benefits for city residents.

Pollution industrial plant by schissbuchse. Public domain via Pixabay.

Pollution industrial plant by schissbuchse. Public domain via Pixabay.In our neighborhoods, we can plant a large tree directly to the west of our dwelling for most effective shading (and avoiding shade on solar collectors). The tree will also add value to the property and the properties surrounding it. Many cities have local groups that have programs that offer shade trees – volunteers and citizens who plant trees report higher satisfaction with their neighborhoods. A well-treed neighborhood also has more residents engaged in physical activity. Getting involved locally has a wide range of benefits.

In our cities, we can advocate for good design to allow large trees to flourish. Trees need an adequate amount of soil to grow, and ensuring local codes and laws are written to provide enough soil for trees will not only benefit the tree, but will reduce infrastructure conflicts, saving taxpayer money. In many places, however, there is a disconnect between the planning and implementation, so we must ensure our urban planners are aware of the importance of trees, designing for tree health, and awareness of what other agencies are doing about the UHI. Good city design at larger scales benefits all city residents – we can advocate for plans that ensure local resilience against future heat waves and alleviating UHIs, as this results in a more livable city for everyone. Getting involved in local decision-making for trees results in positive changes in the way cities are designed.

Lastly, we can insist on a change in building standards that allow for cool roofs. Cool roofs absorb less heat, reducing the UHI and the energy load on buildings. This is an easy to accomplish standard, and easy to grasp for elected officials.

Urban Heat Islands will become more problematic in the future as the planet warms. There are things we can do directly to cool down cities. We can also hold our leaders’ feet to the hot pavement to effect change. The important thing to remember is that there are a number of things we can do. Let us start to do them now, while we remember the brutal heat of 2015.

Image Credit: Atlanta Daytime thermal by NASA. Public domain via NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio.

The post Urban heat islands – What are they and why are they a big deal? appeared first on OUPblog.

What is global law?

Since the end of World War II, with the creation of the United Nations, the rules and structure of the traditional inter-state community have been changing. International law is increasingly shifting its focus from the state to the individual. It gradually lost the features of the classical era, placing greater emphasis on individuals, peoples, human beings as a whole, humanity, and future generations. State sovereignty has been redefined by developments in the field of the safeguard of human rights, peoples’ law, the ‘human’ environment, the common heritage of mankind, cultural heritage, sustainable development and international trade. New norms protect the universal community’s interests. New actors, other than states, are emerging on the international scene. New international norms allow individuals, groups of individuals, corporations, and non-governmental organizations to bring claims before international jurisdictions.

Structurally, we are witnessing an ongoing and gradual ‘verticalization’ of power. The international society has been creating objective rules and procedures to safeguard interests and values of humanity as a whole. Judicial organs and institutionalized procedures to monitor states’ activities have been established. In recent years, there has been a proliferation of international courts and tribunals and, in general, of mechanisms and compliance control procedures which, from their position of authority, ensure respect of norms (customary and treaty-based).

International organizations – in particular those of a universal character – partake in the management of international power by carrying out ‘some’ general functions in several areas of law. The erosion of states’ sovereignty is giving way to a global community and a new international power structure based on multilateral decision processes aimed at protecting fundamental interests and global values.

These changes raise the question of whether the birth of a global community gave rise to a new set of international norms, and whether such norms amount to a system coherent enough to be called ‘Global Law’. This begs the question of whether this new body of laws is different and distinguishable from traditional international law (inter-State law), and if so, what its distinctive features are.

The international legal order is no longer that of the Westphalian era, as a result of the deep transformation of the traditional model of the international community and its constitutive structure.

Globalization is changing not only modern socio-economic and politico-cultural systems but also the law, decision-making processes, enforcement strategies, and the interrelations between multiple normative systems and sub-systems. The international legal order is no longer that of the Westphalian era, as a result of the deep transformation of the traditional model of the international community and its constitutive structure.

It would appear that global law is in an embryonic phase. That is the way legal scholars, who are used to more articulated systems, view it. It is growing as the law of a common humanity bringing with it the emergence of an organizational model of the world’s society based on the gradual integration of various systems of organization (legal, social, economic, etc.) at different aggregation levels, local to worldwide. It is time to focus on a new reality: the gradual transformation of the international community and the structuring process of a global community in which a coherent legal system for a universal human society is being built.

The variety of power centres and decision-making bodies, even informal ones, has led to the development of a multiplicity of supra-national normative regimes and of sub-systems, distinct sets of secondary norms, or relating to a branch of “special” international law, called special treaty-regimes, self-contained regimes, endowed with their own principles, legal institutions, enforcement mechanisms, and dispute resolution mechanisms. We are witnessing a great expansion of global regulatory regimes, especially in economic and social areas. Furthermore, the fact that, apart from the states, other new emerging forces emanating from a multiplicity of actors take part in global governance makes the current legal framework more complex.

The complexity of legal sources is, therefore, the result of the new global order, characterised by growth in interconnection, by changes in social, economic and political dynamics, and by a multi-polar power structure, with continual horizontal and vertical shifts in power.

It is the duty of the courts, in fulfilling their role of applying the norms of international law, to contribute to its harmonious development eliminating the points of conflict which may arise from the interplay between international rules, or between these rules and domestic laws, as well as from the coexistence of different international courts and tribunals.

Legal scholarship, on the other hand, may contribute to the determination of rules of law. It is for international law scholars follow the evolution of the inter-state society towards a global society governed by a law expressed by a wide variety of actors and not only by states.

Their basic task is to provide tools to identify, from the great variety of international practices in political and jurisprudential contexts, a uniform set of legal rules and procedures designed to manage global interests and goods, established for the purpose of institutionalizing governance mechanisms and procedures, defining and allocating powers to the global level, and creating authorities or bodies exercising functions of a public nature.

I like to represent the global legal system as a web made up of filaments (whose properties are resistance, flexibility, and elasticity), arranged in concentric circles linked by threads, evoking the symbolism of weaving. The image of a communal spider web best represents the legal system of a complex multi-polar society. Global law is elastic enough to integrate the heterogeneous elements of the various and different legal orders into a unitary framework. It is up to the community of international legal scholars/lawyers to manage the complexity in the unit of the web of the global law system; the unitary framework retains the flexibility to allow for respecting the diversity of the plurality of embodied legal orders.

Featured image credit: United Nations Flags by Tom Page. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post What is global law? appeared first on OUPblog.

Faith and conflict in the 21st century

As another summer is overcast by reports of religious conflicts and atrocities around the world, I have been thinking about faith, and how the way we understand it affects our response to some of the global challenges we face.

If you were brought up in the western world, you probably think of faith (if at all) in one of two ways. It is the profound, supra-rational conviction or intuition in a believer’s heart and mind which reaches out towards a mysterious divine. Or it is a set of beliefs and practices which people of faith hold are true and right, but about which they often disagree, argue, and even fight.

Both these ideas go back to Augustine of Hippo in the 5th century CE. In his treatise On The Trinity, Augustine described faith as having two aspects: fides quae, the faith which believers believe (that is, the body of Christian doctrine), and fides qua, the faith by which they believe (that which takes place in the heart and mind of a believer). His account has had a huge impact on western Christianity and on western thought in general.

In the 21st century, is it time to reconsider how we understand faith, not only for historical or religious reasons but for contemporary political ones?

Augustine of Hippo by Justus van Gent. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Augustine of Hippo by Justus van Gent. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Augustine’s description of fides was idiosyncratic even in his own day. It would probably have surprised earlier Christians greatly. The core meanings of fides and its Greek equivalent pistis are ‘trust’, ‘trustworthiness’ and ‘faithfulness’ (followed by a wide range of more specialized senses). The authors of the New Testament wrote about the pistis between God, Christ, and those who followed Christ, understood it not primarily as an interior state nor as a body of doctrine, but as a relationship of faithfulness and trust into which ‘the faithful’ entered because they had seen or heard about the love of God and the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Pistis was so central to early Christians’ understanding of their relationship with God that within a couple of generations they were regularly referring to ‘the faith’. This was another term for the new covenant between God and humanity, sealed by the saving self-sacrifice of Christ.

There was nothing intrinsically mysterious about the faith. The phrase ‘the mystery of faith’, which also appears in the New Testament and deeply influenced later Christian thinking, was not intended to mean that pistis was a mystery to community members. It likened the worship of Christ to the Mystery cults which were popular at the time throughout the eastern Mediterranean. What made a cult a Mystery was that only the initiated knew what took place during its main rituals. This was also true of early Christian worship, where only the baptized were allowed to take part in the Eucharist.

All societies and cultures, however, evolve, including religious ones, and Augustine’s definition of faith has dominated western thinking for fifteen centuries. Does it matter now what earlier Christians understood by pistis? I think it does.

For the world’s 2.2 billion Christians, hearing, studying, and learning from the New Testament is still fundamental and formative. Understanding what the people who lived closest in time to Jesus Christ were trying to say when they used pistis language about him and their relationship with him therefore has significant implications for Christians’ understanding of their faith today.

But it matters just as much to everyone else.

In the modern, English-speaking world, we refer to all religious traditions as ‘faiths’. In doing so, we unconsciously impose Augustine’s model on them. We allow ourselves to assume that all religions are intrinsically mysterious; that they always involve supra- rational (or irrational) movements of the mind or heart; that they are based on bodies of doctrine which may at any time be argued or fought over.

We may still be familiar enough with Christianity not (usually) to find this view of it alarming. But when we apply the model to traditions most westerners know less about, we risk creating bogeymen and arousing unnecessary fears. An unfamiliar tradition based on mystery sounds suspicious. One that privileges the non-rational sounds archaic and difficult to negotiate with. One which makes dogmatic truth claims and is willing to fight about them sounds threatening.

“Understanding religious traditions in practitioners’ terms, of course, will not solve the many political and military crises around the world that are tangled up with religion. But it may be part of the solution.”

Religious traditions understand themselves in many different ways, and, in many, faith in either of Augustine’s senses plays little or no part. (Wisdom, for instance, may be more important than belief, orthopraxy than orthodoxy; the focus may be on this world rather than another or on liberation from self-centredness rather than the service of a divinity.) To understand unfamiliar religious traditions and how they inform practitoners private, public, and political lives we need to understand how practitioners themselves understand their tradition.

Understanding religious traditions in practitioners’ own terms, of course, will not solve the many political and military crises around the world in which religion is entangled. But it may be part of the solution.

It is a bad start to involvement in any conflict to assume that the participants or the issues at stake are mysterious, irrational, or driven by dogma. It is more respectful and more productive to seek to understand the issues in participants’ own terms and engage with them on that basis.

Understanding the issues in such terms helps those engaged in conflict resolution to recognize whether religious issues are more or less central to a conflict, and when they are central, how and why, and how they relate to the other issues at stake. Understanding that, creates a basis for better focused and more nuanced negotiations and peace processes. It often also highlights that any religious tradition encompasses different ways of thinking and behaving, many of which do not foster conflict or actively discourage it. There is nothing mysterious, irrational, dogmatic, aggressive, or dangerous to the world about religion per se.

Augustine of Hippo was a great Christian theologian. But in the 21st century, we should be looking both behind his understanding of faith and beyond it. By doing so we can hope to reach a better understanding both of Christianity and of other religious traditions, of religion in general, of the role of religion in global conflicts, and of how we may best seek to resolve such conflicts.

Featured image credit: ‘Candles in a church in Prague’ (cropped) by Dudva, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Faith and conflict in the 21st century appeared first on OUPblog.

August 9, 2015

Tips from a journal editor: being a good reviewer

Peer review is one of the foundations of science. To have research scrutinized, criticized, and evaluated by other experts in the field helps to make sure that a study is well-designed, appropriately analyzed, and well-documented. It helps to make sure that other scholars can readily understand, appreciate, and build upon that work.

Of course, peer review is not perfect. Flawed studies are published, and peer reviewers may miss critical problems or errors in particular studies. Reviewers often do not have the time, nor the inclination, to dig deeply into a study’s methods, or assumptions, or supporting materials, in order to find errors or flaws in a research paper.

Even though peer review is not perfect, as a journal editor I rely heavily on the evaluations and advice provided by peer reviewers. We spend a great deal of time trying to find the right reviewers for each and every paper that we put through the peer review process, and an equally large amount of time reading, evaluating, and putting into appropriate context the responses that we receive from our reviewers.

What is ironic, however, is that despite the importance of peer review in science, it’s not a skill that we typically directly address in our graduate programs, nor in our professional societies. I’m not aware of graduate seminars in “how to be a good peer reviewer”, nor are there materials easily available for scholars to reference when they are asked to undertake a particular peer review task for a journal.

So I thought I’d provide some guidance for journal peer reviewers, at least from the perspective of one of the editors of Political Analysis. Here’s what makes for a good reviewer:

Evaluate the quality of the research reported in the paper you have been asked to review.

Refrain from judging whether the paper is suitable for the journal (unless you are asked for that advice).

Avoid providing a lengthy list of typographical errors.

Reveal your conflicts immediately.

Be timely.

Be brief.

Now, I’ll elaborate a bit more on each point.

First, as a reviewer, your job is to give me an evaluation of the quality of the research reported in the paper that you are provided. Does the theoretical model or hypothesized expectations make sense? Is the data appropriate for testing the hypotheses presented? Are the assumptions of the methodology sound? If the author develops a new theoretical model or estimator, is the math correct? Do the results presented make sense? Are the conclusions appropriate, given the analysis presented in the paper? Those are the most important questions that reviewers need to consider. As a journal editor, I need to know whether a scientific peer reviewer believes that the research reported in the paper is sound.

Second, unless I ask you specifically for your opinion about whether the paper might be suitable for our journal, that’s not advice I’m looking for. After all, I’ve just asked you to review the paper for the journal, so clearly I think that it’s appropriate for peer review! It’s our decision as editors whether a paper might or might not be appropriate for the journal, and while you might have opinions on the matter, in general that’s not what I’m looking for. So refrain from writing in your review that the paper should not be published in our journal because you don’t think the content is suitable for the journal. Unless I ask for that advice, I’m not looking for it.

Third, minor comments — typographical errors in the paper, missing citations, formatting issues, the writing style — really aren’t important to discuss in your review, unless they are so egregious that they detract from your ability to understand what is going on in the paper. Sure, if you want to give the author feedback about these sorts of minor issues, that’s fine, but assuming that we proceed and allow an author to revise their paper, these will be dealt with in the revision, copyediting, and production process. They don’t play an important role in the initial stages of review, unless these problems truly make a paper nearly impossible to understand.

Fourth, ethics. Our journal reviews most papers currently using a double-blind peer review process. That means the editors know who the authors are, and we of course know who the reviewers are. We try our best to avoid asking colleagues to review a paper if they have obvious conflicts of interest. For example, we try to avoid asking for a review from a scholar who we know is a collaborator with an author, who is at the same institution as the author, or who may have some other intellectual conflict with the author. So if you get a paper to review, and you believe you have a conflict of interest that the editor is not aware of, please let us know, as sometimes we may not know of these conflicts. Disclosing the conflict is important; editors can then judge the merits of the review, and proceed accordingly.

Next, be timely. No one wants the review process to drag out indefinitely. Don’t accept review invitations if you cannot fulfill the request in a timely manner. If something comes up that will significantly delay your ability to provide the review in a timely manner, let the editor know. We don’t want to unnecessarily burden you with review requests, and we certainly don’t like to send all of those nagging emails. Being a good reviewer means being providing a timely review.

Finally, be brief and focus on the most important criticisms that you have of the paper. For most manuscripts, we don’t need an evaluation that stretches on for more than four to six paragraphs; in many situations, a review can be far less lengthy than that. We certainly don’t need reviews that go for pages and pages; those tend to be less useful for editors in their decision making, and less helpful for the authors. Stay focused. Let the editors know what you think are the central contributions and important problems with the paper.

While there are no cut-and-dried standards for the conduct of peer review, many journals are starting to provide guidelines for reviewer expectations, in particular when it comes to ethics. Political Analysis has some guidance for reviewers available on our journal’s website, and we will continue to update those guidelines. Hopefully other journals, and our professional societies, will do more in the future to provide guidance to scholars about peer review.

So your job as a peer reviewer for a journal is important. As an editor, we need your evaluation of the scientific merit of the paper we ask you to review. Being a good reviewer is not easy, but it is an important part of being a member of the scientific community.

Featured image: Typing. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Tips from a journal editor: being a good reviewer appeared first on OUPblog.

What five recent archaeological sites reveal about the Viking period

The famous marauders, explorers, traders, and colonists who transformed northern Europe between AD 750 and 1100 continue to hold our fascination. The Vikings are the subject of major new museum exhibitions now circulating in Europe and a popular dramatic television series airing on The History Channel.

Recent years have revealed many spectacular new finds from the Viking age that expand our understanding of their lives and times. Some of these finds — from England and Estonia, reveal the warrior/raider side of Viking life and the dangers therein. Discoveries from Denmark document the extraordinary quality of their ships and shed light on the nature of political and military organization in the Viking period.

Ridgeway, England. The English did not warmly welcome their Viking visitors. Conflict appears to have been common. There is dramatic evidence for this at several places in southern England, especially at a site called Ridgeway near Weymouth, not far from Dorset. During highway construction in 2009, a mass grave was found containing 54 headless human skeletons and a pile of 51 detached skulls that had been cast into an old quarry from Roman times. The grave is dated to around AD 1000. The bodies were those of young men, most less than 30 years of age, who were executed following a violent encounter. Isotopic evidence indicates these men were not natives and may well have come from Scandinavia. The evidence is consistent with a Viking raiding party—50-some men might constitute the crew of a Viking longship with 25 pairs of oars. Perhaps this was a group of raiders who encountered a superior force. They must have been captured, taken to the old quarry, and slaughtered.

Salme, Estonia. Two buried Viking Age ships were uncovered at Salme, Estonia, between 2008 and 2012. Dated to ca. AD 750, these are the earliest known Viking ships to have crossed the Baltic and the earliest examples of mass ship burials. Buried with the two ships were the skeletal remains of 41 individuals, a variety of weapons and tools, and the bones of a number of animals. The materials appear to document the hasty burial of the two ships and the members of their crews who died violently. The grave-goods – weapons and other objects – were of Scandinavian design, largely unknown in Estonia. Isotopic ratios of strontium and oxygen in the tooth enamel of the deceased, in conjunction with the exotic artifacts, point to the Stockholm region of Sweden as a likely homeland.

Jelling, Denmark. Jelling is a sleepy village in the center of the Jutland peninsula with a well-deserved UNESCO World Heritage rating. A series of Viking Age monuments were placed there more than a thousand years ago including rune stones, two huge burial mounds, the largest-known stone ship setting, and an old church. A three-sided rune stone recounts how King Harald Bluetooth united the kingdom of Denmark, the first mention of the name of the modern nation. Harald also built two large burial mounds at Jelling for his parents. The North Mound sits at the center of the ship-shaped stone setting. The present stone church was originally built around AD 1100 and was likely the first such church in Jutland. There are also the foundations of wooden buildings beneath the stone church, two of which were probably wooden stave churches.

Interest in the Viking monuments has been ongoing for more than 400 years, but the surprises keep coming. Excavations since 2007 revealed an entirely new view, including a massive palisade enclosing a large area around the mounds. The entire palisade would have been ca. 1,440 m (4,800′) in length and enclosed some 12.5 ha (30 acres). The symmetry of the constructions is remarkable. The northern burial mound sits directly in the center of this huge timber palisade. The great stone ship setting runs from one end of the palisade to the other. The South Mound lies near the southern side of the palisade, and the largest rune stone at Jelling is exactly halfway between the two mounds. A series of three almost identical buildings were found around the northeast corner of the palisade. These houses are massive wooden halls with heavy walls of vertical timber and several interior divisions. These large buildings or halls were likely part of a magnate estate at Jelling. Thus this sleepy village was once the royal manor of Viking Denmark.

Vallø Borgring, Denmark. There were four known, almost identical Viking ring fortresses in Denmark before the summer of 2012, including the namesake tourist destination at Trelleborg on the island of Zealand. All built around AD 980, each of these fortresses was about a day’s march apart, between 30 and 40 km. But Danish archaeologists noticed there was a gap on the east coast of Zealand. Careful investigations, laser mapping of the landscape, and some trial trenches at a place near the modern town of Køge, south of Copenhagen, exposed evidence for a circular earthwork 145 m (500’) in diameter, the same size as some of the other known fortresses. In Viking times, this fort — known as Vallø Borgring — was strategically located at the intersection of the old road and a small navigable river. There may well be more Viking Age ring forts to be discovered, further documenting the might and sway of the Viking kingdom.

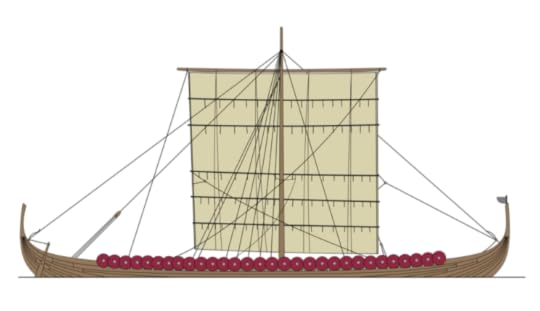

Roskilde, Denmark. The Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde, Denmark, holds the salvaged and reconstructed remains of five ships deliberately scuttled around AD 1070 to block the shipping channel and protect the Viking town. This Museum is one of the more popular tourist attractions in Denmark and has grown substantially over the years. Expansion to a new artificial island was planned and excavation of a channel to create this island began in 1997. Nine new ships were discovered during the digging and eventually removed. One of the ships, the Roskilde 6, is incomplete but estimated to have been 32 m (100′) in length, the longest known Viking warship. A ship of this size must have been the property of a king or noble. Both the timber and craftsmanship were of the finest quality. The ship would have had 78 rowing positions and a crew of 100 men. The mast would have held a single square sail of perhaps 200 m2 (2,150 ft2). The ship was built around AD 1025 and was finally put on exhibit in 2014 after years of conservation and analysis.

These new discoveries prod the imagination and inspire archaeologists, historians, and the general public to learn more about this dynamic period in Scandinavia. The end of the Viking period was ultimately brought about by the arrival of Christianity after AD 1000, leading to the onset of the Middle Ages and long centuries of oppression by the church and state. Some in Scandinavia today would prefer to see a return to the old ways; the religious beliefs of the Vikings, as described in various sagas and myths, have been adopted by some modern individuals and groups. The Vikings are gone but certainly not forgotten!

Jelling Runestones

Image credit:Jelling gr kl Stein by Casiopeia. CC BY-SA 2.0 de via Wikimedia Commons.

Aerial view of Borgring

Image credit: Køge (Lellinge), East Denmark by Danskebjerge . CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the scavenged ship sites in Salme

Image credit: Salme ship scavenged site by Jüri Peets. Image used with permission.

Schematic drawing of the longship type

Image credit: Viking Longship by Ningyou. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Viking Ship Museum – Oslo, Norway, by Alex Berger. CC BY-NC 2.0, via Flickr.

The post What five recent archaeological sites reveal about the Viking period appeared first on OUPblog.

Jazz at the BBC Proms

Celebrating their 120th birthday this year, the BBC Promenade Concerts – universally known as “The Proms” – rank as the world’s biggest classical music festival. With 76 concerts, running from July to September, of which the vast majority focus on classical music, not only do the events reach a sizeable audience live in London’s Royal Albert Hall, or for the earlier daytime concerts, the Cadogan Hall, but there’s a much bigger audience for the nightly live broadcasts on BBC radio and for the highlights on television.

The Proms today include music that lies well outside the classical world that would be recognised by its founder, the conductor Sir Henry Wood (1869-1944). With DJ Pete Tong celebrating house music in Ibiza, Mistajam and Sian Anderson exploring hip hop and grime, and Bollywood plus contemporary Asian sounds in Bobby Friction’s Asian Network Prom, the series has caused a great deal of controversy among those who are appalled at the loosening of its remit to include non-classical genres. The Sibelius Society has written to The Times (20 July) calling into question how this dilution squares with the two “once noble institutions” of The Proms and The BBC. Other readers have questioned whether the Ibiza Prom is a spoof in the manner of the satirical television series W1A, which debunks the BBC’s style of internal management. Yet if broadcasting these fringe late-night concerts via other BBC networks helps to draw in new listeners to the core classical events, that would seem to be an advantage, not least because over 70 of the concerts remain purely classical.

But in just the same way that jazz has hovered at the margins of the BBC’s classical station Radio 3 for over 50 years (the programme I present, Jazz Record Requests, celebrated its half century last year) it has been an integral part of Proms programming for almost thirty years. Its presence infuriates some individuals, both on the radio station as a whole and in the concert series in particular, but nowadays it is generally regarded as a perfectly acceptable adjunct to the core classical repertoire. Unlike house music, hip hop and Bollywood, its presence in the programme passes unremarked upon in most quarters, and is positively welcomed in others.

Almost every year there has been a jazz event that has blended seamlessly into the core programming. Just like the classical concerts, this has included distinguished overseas visitors to London (Wynton Marsalis and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra in 2004), pillars of the UK jazz establishment (Sir John Dankworth and Dame Cleo Laine in 2007), young revolutionaries (Loose Tubes in 1987), and their not-so-young present-day manifestations (Django Bates in 2013, celebrating Charlie Parker, and Nigel Kennedy crossing over from classics to jazz in 2008). There have been celebrations of particular artists and repertoire too, such as Martin Taylor and Guy Barker’s 2012 collaboration on “The Spirit of Django” exploring new settings for manouche gipsy music.

July 26th “BBC Proms” (2008) by Amanda Slater, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

July 26th “BBC Proms” (2008) by Amanda Slater, CC BY 2.0 via FlickrThis year sees a bold and ambitious project, putting two big bands, formed of the UK’s major players, together to tell the story of the development of swing, linked by the singer and radio presenter Clare Teal. It is an outgrowth from a late night event last year, in which Clare sought to recreate the duelling atmosphere of “big band battles” that took place in New York’s Savoy Ballroom in days of yore. But this year, there’s an attempt to add some scholarly weight to the concert, with a pre-concert event (which will be broadcast in the interval) at which I’ll be discussing the history of the music with Dr Harvey Cohen of Kings’ College London and Dr Catherine Tackley of the Open University.

It’s a chance for me to round up some academic hares that have been set running over several years. When I was researching Cab Calloway’s life, I found my investigations were dovetailing with Harvey’s. He and I were both working on the Svengali-like figure of Irving Mills, who more or less invented the role of artist’s agent, but who also extended his activities to publishing, record production, nightclub programming and — on an unprecedented scale in the arts — marketing. He managed both Calloway and Ellington. This is a chance for us to look at how Mills affected much of the growth of the swing era across several bands and decades. Equally, back in the 1980s, I published a series of oral histories, including the life of saxophonist Art Rollini, who played tenor saxophone with Benny Goodman for many years. This event gives me and Catherine the chance to compare Art’s uniquely personal view of the band with Catherine’s forensic account of its gestation and — significantly for this particular Prom — its move into the classical arena of Carnegie Hall.

So thank you BBC for offering the opportunity to pull together live performance and jazz history. Let’s hope that when David Pickard arrives from Glyndebourne to direct the BBC Proms from next year he’s not deterred by the naysayers, and continues to find a place for deeper and more searching explorations of jazz and its history in the programme for the 121st year and beyond.

Featured image: Jazz players. Photo by Pedro Ribeiro Simões, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Jazz at the BBC Proms appeared first on OUPblog.

Curry paradox cycles

A Liar cycle is a finite sequence of sentences where each sentence in the sequence except the last says that the next sentence is false, and where the final sentence in the sequence says that the first sentence is false. Thus, the 2-Liar cycle (also known as the No-No paradox or the Open Pair) is:

S1: Sentence S2 is false.

S2: Sentence S1 is false.

And the 3-Liar cycle is:

S1: Sentence S2 is false.

S2: Sentence S3 is false.

S3: Sentence S1 is false.

The Liar paradox itself is just the 1-Liar cyle (where the Liar sentence plays the role of both the first sentence and the last sentence in the sequence of length one):

S1: Sentence S1 is false.

We can prove, for any finite number n, that if n is odd then there is no stable assignment of truth and falsity to each sentence – that is, that the sequence is paradoxical, and if n is even then there are exactly two distinct stable assignments of truth and falsity (the trick is noticing that any stable assignment will alternate between true sentences and false sentences).

The closely related Curry paradox arises by considering a conditional statement (an “if… then…” statement) that says that its own truth implies that some completely unrelated sentence holds. Here we are assuming that the conditional in question is what logicians call a material conditional: an “if… then…” statement that is false if and only if the antecedent (the “if…” bit) is true and the consequent (the “then…” bit) is false, and is true otherwise. Here is a typical Curry conditional:

C1: If C1 is true, then Santa Claus exists.

We can use the Curry conditional above, plus straightforward platitudes about truth (i.e. that a sentence is true if and only if what it says is the case) to prove that Santa Claus exists:

Proof: Assume (for reductio ad absurdum) that the Curry conditional is false. Then the antecedent of the Curry conditional is true (and the consequent false). The antecedent of the Curry conditional says that the Curry conditional is true. Since the antecedent is true, what it says must be the case. Hence the Curry conditional is true, contradicting the assumption with which we began.

Thus, the Curry conditional cannot be false, so it must be true. But if the Curry conditional is true, then what it says must be the case. The Curry conditional says that, if the Curry conditional is true, then Santa Claus exists. So if the Curry conditional is true, then Santa Claus exists. But we already established that the Curry Conditional is true. Hence Santa Claus exists. QED.

Interestingly, Curry cycles have not, to my knowledge, been investigated until now. A Curry cycle is a finite sequence of conditionals where each conditional in the sequence except the last says that if the next conditional is true, then some clearly false sentence holds, and where the final conditional in the sequence says that if the first conditional is true, then some clearly false sentence holds. The following is an example of the 2-Curry cycle:

“Either Santa Claus exists, or the Easter Bunny exists, or the Great Pumpkin exists.”

C1: If conditional S2 is true then Santa Claus exists.

C2: if conditional S1 is true then the Easter Bunny exists.

And the following is a 3-Curry cycle:

C1: If conditional S2 is true then Santa Claus exists.

C2: If conditional S3 is true then the Easter Bunny exists.

C3: If conditional S1 is true then the Great Pumpkin exists.

The Curry paradox itself is of course just the 1-Curry.

Now, if n is a finite even number, then (similar to Liar cycles) the n-Curry cycle is not paradoxical (where here a paradox arises if we are forced to accept as true one of the clearly false consequents). In fact, each such cycle has two distinct stable truth value assignments where all the consequents are false (hint: every other conditional is true).

Things get more interesting when we look at Curry cycles of odd length, however. These are paradoxical, but in a certain sense not as paradoxical as one might think. One might guess that the 3-Curry cycle above would allow us to prove that Santa Claus exists, and prove that the Easter Bunny exists, and prove that the Great Pumpkin exists. But we can’t prove any of these. What we can prove, however, is:

Either Santa Claus exists, or the Easter Bunny exists, or the Great Pumpkin exists.

Proof: Assume that the offset claim above is false. So “Santa Claus exists” is false, and “The Easter Bunny exists is false”, and “The Great Pumpkin exists” is false. We will show that this assumption leads to a contradiction (and hence that the offset claim above must be true after all). Now, either the conditional C1 is true, or it is false.

Case 1: The conditional C1 is true. The antecedent of conditional C3 says that conditional C1 is true, so the antecedent of conditional C3 is true. Thus, the conditional C3 has a true antecedent and false consequent, so the conditional C3 is false. The antecedent of conditional C2 says that conditional C3 is true, so the antecedent of conditional C2 is false. Thus, the conditional C2 has a false antecedent and false consequent, so the conditional C2 is true. The antecedent of conditional C1 says that conditional C2 is true, so the antecedent of conditional C1 is true. Thus, the conditional C1 has a true antecedent and false consequent, so the conditional C1 is false. This contradicts our initial assumption that C1 was true.

Case 2: Similar to Case 1, and left to the reader (it helps to draw a little 3 x 3 grid, to keep track of the truth values of antecedents, consequents, and conditionals). QED.

We can’t do better than this, though, and similar results hold for longer odd-length Curry cycles. In short, odd-length Curry cycles are paradoxical in that they entail that some clearly false claim is true, but if the cycle contains three or more conditionals (with three or more distinct consequents) then we can’t tell which of the clearly false claims is the one that, according to the paradox, must be true.

Featured image credit: ‘Squares, circles, and lines, oh my!’ Photo by kennymatic, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Curry paradox cycles appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers