Oxford University Press's Blog, page 628

August 17, 2015

The undiscovered elements

How can an element be lost? Scientists, and the general public, have always thought of them as being found, or discovered. However, more elements have been “undiscovered” than discovered, more “lost” than found.

There are three great advances that revealed the true relationship of chemical elements to one another: Dmitri Mendeleev’s doctrine of the periodic table (1869), Henry Moseley’s law (1913) that conferred a number and an identity on every element by virtue of its number of nuclear protons, and Frederick Soddy’s discovery (1921) that more than one type of atom could occupy the same place in the periodic table as long as that all-important proton number were the same. Despite these markers along the trail, many scientists continued to make conceptually absurd and ridiculous errors. Many of these wrong turns were the results of experimental errors, whereas others arose from incompetence, scientific fraud, unorthodox beliefs, a misplaced nationalism, or just plain obstinacy.

But there’s more to be learned from these false discoveries than their “wrong science.” For example, Johann Bartholomäus Trommsdorff, who burst on the chemical scene in 1800 by announcing the discovery of augusterde (soon to be proven false), came from a family engaged in the pharmacist’s profession for an uninterrupted 200 years. Trommsdorff, unfortunately, did not bring glory to the family by announcing some years later the discovery of another non-existent element, crodonium. And then there was the case of Eugène Anatole Demarçay, who truly discovered europium, but then postulated the existence of another four elements that he provisionally designated by the Greek letters Γ, Δ, Ω, and Θ. Demarçay dedicated a good part of his brief life to research, exposing himself without precautions to radiation, harmful substances, and toxic vapors with serene resignation as he saw his health deteriorate rapidly. The story of the Japanese chemist, Masataka Ogawa, is particularly tragic. For all of his professional life, he claimed to have discovered element number 43, calling it nipponium after his native land. However, this elusive element was never isolated, and Ogawa died still chasing a phantom. Fear permeates the story of the Italian Luigi Rolla. He spent 17 years and carried out over 56,000 fractional crystallizations in the search for element 61, which he named florentium, only to have his worst fear realized: that priority for the discovery was claimed by a team of chemists from Illinois. It was only years later that both groups were discredited since the element did not exist except as a short-lived radioisotope.

It is understandable that the hunt for so many elements was on and that many scientists went down the wrong track. Time was of the essence, and the rewards for new discoveries were immense. Caution was often thrown overboard by both amateurs and professionals hot on the trail of the prestige that would accrue to someone who could expand the periodic table, gain the right to give a new element its name, and thereby create an eternal monument.

Enrico Fermi. Office of Public Affairs, United States Department of Energy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Enrico Fermi. Office of Public Affairs, United States Department of Energy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Surely one of the brightest stars to shine in the Italian physics firmament was Enrico Fermi, the precocious physicist who received his doctorate in that discipline from the University of Pisa at only 21 years of age. In 1927 at age 26 he was elected Professor of Theoretical Physics at Rome, a post created specifically for him, and for the next seven years he was occupied with theoretical studies on spectroscopic data. In 1934 things changed dramatically when he turned his attention to the atomic nucleus, demonstrating that he could accomplish nuclear transformations through neutron bombardment. The official website of the Nobel prize states: “This work resulted in the discovery of slow neutrons that same year, leading to the discovery of nuclear fission and the production of elements lying beyond what was until then the Periodic Table.” In 1938, Fermi was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for this work, and immediately thereafter departed Italy for the United States in order to escape Mussolini’s Fascist regime. Fermi’s original paper on this topic hypothesized the first production of the transuranium elements, which he named ausonium and hesperium, thus expanding the periodic table beyond uranium, but further work has shown that this supposition was incorrect. Had he and his colleagues not laughed Lise Meitner’s suggestion of nuclear fission to scorn, they would have made the greatest discovery of the 20th century. Nevertheless, Fermi’s subsequent brilliant work was enough to win him a place in the periodic table itself – element 100, fermium. He died an untimely death of stomach cancer at the age of 53. So here we learn that even the brightest stars can sometimes lose their luster.

But dogged sticking to one’s errors as well as stupidity and incompetence are not easily forgiven by the scientific establishment. Particularly frowned upon are press conferences and criminal proceedings before the peer review of a publication. Thus it was with Martin Fleischmann, the British electrochemist, who died in 2012 a lonely and bitter man. Right up to the end he remained convinced of his (imaginary) energy-producing, “cold” fusion of deuterium on palladium electrodes – he was right, of course; the world was wrong. He had long ago forfeited his credibility as a scientist. Even worse are the liars, cheats, and charlatans of every shade, which unfortunately, pop up again and again. Sooner or later they will be exposed because the system is infallible and self-correcting, at least on issues which are really interesting. Yet it can take quite a long time until the issue is finally put to rest, especially considering the alarming proportions of scientific illiteracy.

Feature Image: Test tubes. Photo by Armin Kübelbeck, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The undiscovered elements appeared first on OUPblog.

Freedom from Detention for Central American Refugee Families

August 19th is World Humanitarian Day, declared by the UN General Assembly in 2008, out of a growing concern for the safety and security of humanitarian workers who are increasingly killed and wounded direct military attacks or infected by disease when helping to combat global health pandemics. World Humanitarian Day is an occasion to express our solidarity with the tens of thousands of humanitarian professionals and volunteers who serve and sacrifice on behalf of war- and disaster-effected communities. It is also our opportunity to stand with the tens of millions of the world’s citizens who are the direct victims of armed conflict, human rights abuses, and environmental disasters.

As a response to conflict and insecurity throughout the world, humanitarian action is grounded in the tenets of international humanitarian law. The foundational principles are humanity, the alleviation of suffering, distinction, the protection of civilians, and proportionality and necessity, the use of military force only sparingly and as a last resort. These customary principles find expression in the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, ratified by the United States, particularly Common Article 3, which requires the humane and non-discriminatory treatment of civilians, detained persons, and wounded combatants.

The principles and treaty provisions of international humanitarian law combine with international refugee law to affirm the dignity, agency, wellbeing and legal personality of all individuals confronted with violence and forced displacement in time of war or peace. The US Congress enacted the 1980 Refugee Act to establish procedures for granting asylum to individuals with a well-founded fear of persecution consistent with US obligations under the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees.

Since the summer of 2014, thousands of mothers and children fleeing gang, cartel, and domestic violence in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala have been detained in Texas and Pennsylvania, in corporate detention centers under contract with the US Department of Homeland Security, as they pursue their asylum claims in Immigration Court. Initially, most of the arriving moms and kids were detained in Artesia, New Mexico, until December of 2014, when they were transferred to Texas and re-interned, along with hundreds of newly arriving families, in two family immigrant detention centers in the San Antonio area – Karnes managed by GEO Group, and Dilley by the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA).

McAllen, TX, USA – July 8, 2014: A volunteer member of a Catholic Charities Disaster Response Team talks with a Central American refugee mother and child at the intake and orientation table of the reception hall of the Sacred Heart Catholic Church. (c) vichinterlang via iStock.

McAllen, TX, USA – July 8, 2014: A volunteer member of a Catholic Charities Disaster Response Team talks with a Central American refugee mother and child at the intake and orientation table of the reception hall of the Sacred Heart Catholic Church. (c) vichinterlang via iStock.Over the past 12 months, the plight of detained mother and child asylum-seekers from Central America has been met with a groundswell of community solidarity with the families as refugees with bona fide claims to protection from persecution. The painful experiences of these families, at home, in flight, and in detention, has led to mounting interfaith and grassroots opposition to the internment of mothers and children in jail-like facilities with inadequate medical care amid mounting evidence of child endangerment and maternal trauma. At the same time, non-profit immigrant service agencies such as RAICES of San Antonio and national lawyers groups such as the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) have brought volunteer lawyers and law students into the detention centers, to assist the mothers in their initial interviews with asylum officers, and with their bond and asylum hearings in Immigration Courts.

Litigation filed at the federal level has led to two important rulings by federal district court judges this year, the first in February rejecting the Administration’s claim that the families are presumptive risks to national security; and the second in July finding the detention of children in closed facilities to be a violation of the 1987 Reno v. Flores consent decree on the protection of migrant youth.

Despite community activism, hunger strikes, suicide attempts on the part of mothers, and Judge Dorothy Gee’s most recent finding that the government is in violation of the Flores settlement, the Obama Administration continues to maintain that the internment of asylum-seeking families in private detention facilities is a viable policy. The Administration’s position with regard to Flores flies in the face of the government’s release of hundreds of mothers and children since Judge Gee’s ruling, and the June 2015 statement of Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson that the long-term detention of immigrant families should be discontinued.

As an American looking forward to 19 August, I am mindful of the humanitarian community volunteers and advocates working on either side of the US-Mexico border who demand due process and equal protection for Central American asylum seekers, and to all Americans regardless of descent. Our US elected officials also have a humanitarian role to play. How will they observe their obligations under international and US refugee law on World Humanitarian Day?

The post Freedom from Detention for Central American Refugee Families appeared first on OUPblog.

August 16, 2015

Incoherence of Court’s dissenters in same-sex marriage ruling

The Supreme Court’s much-anticipated decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, the same-sex marriage case, is pretty much what most people expected: a 5-4 decision, with Justice Kennedy — the swing voter between the Court’s four liberals and four conservatives — writing a majority opinion that strikes down state prohibitions. Justice Kennedy’s reasoning is pretty much what was expected as well, arguing that the right to marry the person of one’s choice is a fundamental liberty, and buttressing this right with the requirement that states treat their citizens even-handedly under the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause. Perhaps his heavy reliance on liberty is a bit of a surprise; if so, it is a welcome one.

The four dissenters, who wrote four separate opinions, offer a real surprise however. It’s not their position, their basic arguments, or even the intellectual weakness of those arguments (there is, after all, no principled basis for opposing government recognition of same-sex marriage). It’s the incoherence, insensitivity, and generally hysterical quality of those opinions that provide the drama in this important but widely-predicted decision.

Chief Justice Roberts’ dissent, which all of the other conservatives joined, is the most temperate, but even that one is filled with howls and howlers. He begins with the argument that marriage is traditionally between a man and a woman; it is, he writes, “a social institution that has formed the basis of human society for millennia, for the Kalahari Bushmen and the Han Chinese, the Carthaginians and the Aztecs.” If his point is that marriage has been around for a long time, it seems odd to use two presently existing ethnic groups, the Bushmen and the Han Chinese, as examples. Maybe he was getting the Han Chinese confused with the Han Dynasty, which collapsed a few centuries before the fall of Rome. But why are the Bushmen (more properly known as the San) being used as an example of ancient history: Because they live a simpler lifestyle than we do? Because they have darker skins? The Carthaginians and the Aztecs are indeed past civilizations, however, and both, despite many great achievements, were notorious for their extensive reliance on slavery and human sacrifice. (One of the Carthaginian achievements was to bequeath to us the word “gorilla,” which referred to what were probably the flayed skins of sub-Saharan African people that hung in their central square). Justice Roberts continues by asking “Just who do we think we are?” to contradict the practices of these ancient civilizations. The answer, John, is that we’re the people who established a nation based on human rights and human liberty. We’re the people who overturned the traditions that perpetuated inequality and injustice for all those previous millennia.

Image Credit: White House Photographer. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: White House Photographer. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.Justice Roberts continues that traditional marriage is designed for the purpose of procreation, “which occurs through sexual relations between a man and a woman … For the good of children and society, sexual relations that can lead to procreation should occur only between a man and a woman committed to a lasting bond.” No John, procreation occurs through the fertilization of a human egg by a human sperm, something that modern medicine enables us to perform outside a man or a woman. Many children, for straight as well as lesbian individuals and couples, are conceived that way these days. If the biology is a bit out of date here, the morality is both out of date and confused. Is the Chief Justice really saying that while homosexual sex is just fine, heterosexual sex outside of marriage by people of child-bearing age is a moral wrong? And is that a sufficiently coherent moral basis to justify state law prohibitions against same-sex marriage? The effort to connect the ban on same-sex marriage to procreation and child-rearing inevitably founders on a myriad of obvious contradictions (polygamy should be encouraged for its procreative efficiency, old or infertile people shouldn’t be allowed to marry). But the basic one, in the context of this case, is that Roberts touts as the exclusive province of heterosexual marriage exactly what the petitioners are asking for: the opportunity to be “committed to a lasting bond,” often for the sake of raising their biological or adopted children.

Next, Justice Roberts turns to the majority’s argument that traditional marriage is not worth upholding, since it was typically arranged by the parents and included coverture, the legal doctrine holding that the wife’s legal identity was subsumed by her husband’s. But those features aren’t central to the concept of marriage, the Chief Justice argues in a disparaging tone: ‘If you had asked a person on the street how marriage was defined, no one would have ever said, ‘Marriage is the union of a man and a woman, where the woman is subject to coverture’.” Yes they would have, John. They might not have known the legal term, but those people on the street would all have understood marriage to be about the husband’s dominance over his wife. Men who failed to carry out this role were scorned, and sometimes ostracized; women who objected to it were seen as monstrosities. As a seventeenth century poet wrote: “I know not which live more unnatural lives, Obedient husbands, or commanding wives.” The subordination of the woman was central to the traditional definition of marriage, just like the man and woman requirement.

Having gotten marriage wrong, Justice Roberts proceeds to get the Supreme Court’s role wrong as well. The real question in the case, he says, is whether the decision about same-sex marriage “should rest with the people acting through their representatives or with five lawyers.” But the decision can’t really be described as resting with “five lawyers” John. It’s a decision of the Supreme Court of the United States, which, like most of our institutions, reaches its decisions by a majority vote of its members. That Court’s role is to protect human rights from the “people acting through their representatives.” Ever since our nation was founded, the dangers that inhere in the “tyranny of the majority” have been widely recognized. The universally-acknowledged purpose of the Court you lead, John, is to counteract that basic flaw in an otherwise desirable system of government. When a minority group is unpopular and widely scorned, when it finds the majority ranged in unity against it, when that majority acts to deny the minority the basic rights to which all people are entitled, and which the members of the majority enjoy, it is precisely the Court’s role to invalidate the majority’s actions and ensure the rights of all Americans.

Drawing on an unfortunate theme in modern political theory, the deliberative justification for democracy, Justice Roberts glorifies the political debate about gay marriage that is currently being carried on in the states. That debate reflects the true spirit and operation of our democratic system, he says; the Supreme Court, by declaring laws against same-sex marriage unconstitutional, “puts a stop to all that” in his view. This is the theme that the other three dissents trumpet at extraordinary length, and in such high-pitched, hysterical terms, that even the Chief Justice cannot bring himself to join them (although two of them join him). The picture of a benevolent, edifying debate about public policy is weirdly unrealistic, and patently offensive, when applied to a social movement organized by one of the most consistently disadvantaged and disparaged groups in our society to fight for equal rights and decent treatment. The current controversy is not a rational debate about public policy. It’s an effort by committed people, both gay and straight, to end centuries of discrimination, a word that none of the dissenters ever use in over 60 pages of dissent, not even once. It represents a deeply moral initiative to recognize that in our modern world, people should not be denied the opportunity to pursue their goals and receive equal treatment because of their gender or sexual orientation.

Featured Image Credit: “Rainbow flag: banner, harvey milk plaza, castro, san francisco” by torbakhopper. CC BY 2.0, via Flickr.

The post Incoherence of Court’s dissenters in same-sex marriage ruling appeared first on OUPblog.

Who was Richard Abegg?

One of the most interesting developments in the history of chemistry has been the way in which theories of valency have evolved over the years. We are rapidly approaching the centenary of G.N. Lewis’ 1916 article in which he proposed the simple idea that a covalent bond consists of a shared pair of electrons. No doubt there will be celebrations and special issues of various journals that will be motivated by the arrival of this centenary. But as in all celebrations we tend to forget some lesser known contributors who provided important steps towards the eventually adopted theories. Here I would like to recall the work of one of these sub-alterns, the German chemist Richard Abegg.

Abegg had the good fortune of studying and working with Lothar Meyer, Ladenburg, A.W. Hoffman, Ostwald, Arrhenius, and Nernst before his life was tragically cut short at the age of 41 when he died in a ballooning accident. But before this untimely end Abegg provided what was perhaps the most important step in valence theory between the discovery of Mendeleev’s periodic system and G.N. Lewis’ notion of octets of electrons.

After publishing his periodic table in 1969, Mendeleev had noticed that the valences of many elements obeyed an important relationship that has been called his rule of eight. Mendeleev observed that the formulas of hydrides occurred in four forms, namely RH, EH2, RH3, EH4. Meanwhile, with oxygen the following forms are found,

Richard Abegg. Image Credit: Meisenbach Riffarth & Co Berlin, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Richard Abegg. Image Credit: Meisenbach Riffarth & Co Berlin, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.R2O, RO, R2O3, RO2, R2O5, RO3, R2O7, RO4

Mendeleev noted that for no element does the sum of the hydrogen and oxygen equivalences exceed eight.

Oxide RO4 R2O7 RO3 R2O5 RO2

Hydride none RH RH2 RH3 EH4

Significantly, for what is to come, this relationship seems to only apply to elements from just four groups in the periodic table. Mendeleev’s rule remained obscure until it was noticed by Abegg who gave it a new lease of life by making it more general.

Instead of confining himself to compounds of oxygen and hydrogen, Abegg concentrated on the maximum and minimum valences available to each element, even if this was the case only in principle. The deeper significance of Abegg’s approach is that he did not face the same problem as Mendeleev when it came to compounds from groups I to III in the periodic table. It is as though Mendeleev was assuming that hydrogen was the most electronegative element whereas in fact elements such as those in groups I to III are typically more electropositive than hydrogen. Of course Mendeleev could not approach matters from an electrical point of view as Abegg did, since no such electrical views had yet been developed in the 1870s. And even when they were by the likes of Arrhenius, Mendeleev remained famously opposed to them.

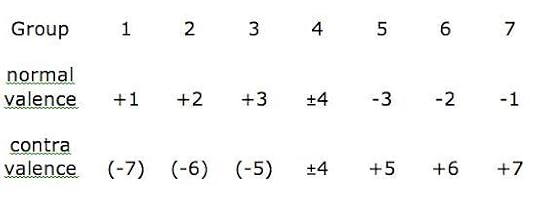

Figure 1. Abegg’s normal and contra-valences that together add to eight, (ignoring the signs in front of each individual value).

Figure 1. Abegg’s normal and contra-valences that together add to eight, (ignoring the signs in front of each individual value).According to Abegg’s rule of eight, elements are in principle capable of showing a maximum electropositive valence (normal valence) and a maximum electronegative valence (contravalence) in which the sum of the two valences is always equal to eight. Clearly Abegg had succeeded in generalizing Mendeleev’s rule, by making it more abstract and in removing the apparent problems that had prevented Mendeleev’s rule from being applicable to all eight groups of the periodic table.

In addition, in an article written in 1899 Abegg wrote,

The sum of eight of our normal and contra-valences has therefore the simple significance as the number which represents for all the atoms the points of attack of electrons; and the group number of positive valency indicates how many of the eight points of attack must hold electrons in order to make the element electrically neutral.

Abegg’s points of attack would soon become the eight electrons arranged at the corners of cubes, which would it turn become pairs of electrons at the corners of a tetrahedron and eventually a ring of eight electrons. And the rest, as they say, was history, especially in the hands of somebody as capable as G.N. Lewis.

Featured image: Wave. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Who was Richard Abegg? appeared first on OUPblog.

Individuals as groups, groups as individuals

People exist at different times. My life, for instance, consists of me-at-age-five, me-as-a-teenager, me-as-a-university-student, and of course many other temporal stages (or time-slices) as well. In a sense, then, we can see a single person, whose life extends over time, as akin to a group of people, each of whom exists for just a short stretch of time.

This perspective raises a host of interesting questions. Here’s one: Coherence is often considered a rational virtue. Rational people have beliefs, desires, and other attitudes that cohere with each, that fit together nicely, while having attitudes that clash with each other is a mark of irrationality. Certainly that’s the case for coherence at a single time. If there’s a time where you have inconsistent beliefs, then that’s irrational. But what about coherence over time? Is that a rational virtue too? Should your beliefs and desires held at different times fit together in any particular way? Should your actions, performed at different times, fit together as part of a sensible long-term course of action?

Many philosophers have thought so. After all, if your beliefs, desires, and actions at different times don’t cohere with each other, then you’re likely to engage in self-defeating behavior. If you keep changing your mind about what to try to achieve or about how best to achieve it, then (so the thought goes) you’ll wind up achieving nothing. You will start projects but promptly abandon them as soon as you adopt different goals or change your views about the best way of reaching your goals.

But there are grounds for suspicion. To take the case of belief, why should what you believed in the past matter for what you ought to do now? Shouldn’t it just depend on what evidence you have right now? And letting facts about how you acted in the past influence your present decision-making can seem like committing the sunk-cost fallacy.

More to the point, why should you treat your past selves differently from how you treat other people? Why should your past selves’ attitudes and actions matter more for how you rationally ought to be going forward, than any stranger’s attitudes and actions? Seeing yourself as akin to a group (a group of time-slices), it’s tempting to think that your different time-slices are no more beholden to each others’ attitudes and actions than are the members of any other group.

Insights about individual rationality can help us design better group decision-making procedures, and insights about groups can lead us to revise our views about individual rationality.

Beyond demoting the importance of coherence over time, adopting this perspective means taking certain analogies seriously. We can see memory as a kind of testimony – testimony from one’s past selves. And whether one should trust one’s memory will depend on exactly how reliable one thinks it is, just as whether one should trust someone’s testimony depends on how reliable one thinks that person is. And we can see intentions as like commands or advice coming from one’s past selves. Whether one should satisfy that intention then depends on how good one thinks one’s past self was as an advisor, or on whether there are any costs to disobeying its commands. (A useful way to control one’s future selves is to change their incentives; think of the smoker who tries to quit in part by betting his friend that he won’t have a cigarette in the next month.)

This idea, that individuals are akin to groups, goes back at least to Derek Parfit. In his highly influential Reasons and Persons (OUP, 1986), he writes that “when we are considering both theoretical and practical rationality, the relation between a person now and himself at other times is relevantly similar to the relation between different people” (p. 190). Parfit thought that personal identity over time was unimportant both for rationality and, more controversially, for morality. (The latter raises some other interesting issues: If your past and future selves are like other people, as far as morality is concerned, is it morally wrong to coerce your future self, like our foresighted smoker, or is it sometimes morally permissible to coerce others, if it’s for a good reason? Is it wrong to harm one person to benefit her in the future, say by sticking her with a needle to vaccinate her, or is it sometimes morally permissible to harm one person to benefit a different person?)

Taking seriously the analogy between individuals and groups opens promising avenues for new research. There is a vibrant debate about group rationality, about how we should take individuals’ beliefs or preferences and aggregate them to come up with a ‘group belief’ or ‘group preference.’ This is important for democracy and for other cases where people must act as a unified group–that is, as akin to a single individual–as in the case of a panel of judges who must issue a joint opinion. Group Agency by Christian List and Philip Pettit, is an excellent discussion of these issues.

We might even go further and think of individuals at particular times–your different time-slices, say–as group-like in some respects. When you seem to have contradictory beliefs, perhaps it’s useful to think of yourself as a fragmented person, with each fragment having a different (but consistent!) set of beliefs. And in cognitive science, it is now common to think of the mind as consisting of different semi-autonomous subsystems (though whether these subsystems are like individuals varies depending on the case) – there is Marvin Minsky’s Society of Mind hypothesis, Jerry Fodor’s modularity hypothesis, and Kahneman and Tversky’s division of the mind into System 1 (which is fast, automatic, and subconscious) and System 2 (which is slow, effortful, and conscious).

Seeing individuals as groups, then, opens opportunities for cross-pollination. Insights about individual rationality can help us design better group decision-making procedures, and insights about groups can lead us to revise our views about individual rationality, for instance, by leading us to conclude that coherence over time isn’t a rational imperative. And, as Parfit himself thought, it can lead us to a more open, generous stance, where we treat the boundary between ourselves and others as less important than we otherwise might.

Featured image credit: City sunny people street by David Marcu. CC0 via Pexels.

The post Individuals as groups, groups as individuals appeared first on OUPblog.

August 15, 2015

Getting to know the Online Product Marketing Team

Spanning the Atlantic from New York to Oxford, the Global Online Product Marketing team is a motley bunch with a love for all things digital. As custodians of a diverse portfolio of online offerings, they definitely know what’s what on the web. Read on for some literary and digital favourites from the team, and a glimpse into the minds of our online gurus here at Oxford University Press.

What is your favourite blog or podcast and why?

“This American Life and The New Yorker fiction podcast.”

—Sam Zimbler, Marketing Associate

“I am obsessed with the Invisibilia podcast from NPR. Read the description from their site and just try not to listen: “Invisibilia (Latin for all the invisible things) is about the invisible forces that control human behavior—ideas, beliefs, assumptions and emotions. Co-hosted by Lulu Miller and Alix Spiegel, Invisibilia interweaves narrative storytelling with scientific research that will ultimately make you see your own life differently.”

—Erin Fegely, Assistant Marketing Manager

Erin Fegely. Used with permission.

Erin Fegely. Used with permission.“I love Desert Island Discs on Radio 4, it’s perfect listening when cooking or doing the mind-numbing chore of ironing my work shirts. My life goal is to be on it, so Kirsty Young, if you’re reading this…”

—Barney Cox, Senior Marketing Executive

“Clutch Magazine is one of my favorite blogs. It’s for women of color like myself. The blog reports on beauty, health, love, sex, fashion, and politics in a fun tone while expertly addressing serious matters that affect young African-American women in today’s society.”

—Miki N. Onwudinjo, Junior Level Marketing Coordinator

“Brain Pickings. The images and quotations paired together are really inspiring.”

—Georgia Brodsky, Assistant Marketing Manager

If you had to be trapped in an elevator for ten hours with any famous person living or dead, who would it be?

“I’m extremely claustrophobic and I’m having a mini panic attack just imagining this scenario; given that fact, I am going to have to pick Thich Nhat Hanh who I am sure could calm me down.”

—Erin Fegely, Global Assistant Product Marketing Manager

“Agatha Christie! I love crime fiction (some may say I’m a little bit obsessed)—especially the novels of the Golden Era of crime, with Christie being the Queen of Crime. I bet she would be able to while away the hours coming up with stories of murder and intrigue, and I’d love to ask her about her writing style, inspirations, and what she was doing in Yorkshire when she disappeared.”

—Hannah Charters, Associate Marketing Manager

“Firstly, ten hours, that’s a long time! I don’t think I’d want to be trapped in an elevator with anyone for ten hours, at least not without prior warning, so I could bring snacks. I’d pick somebody fascinating from history so they could tell me all about their life to pass the time. Let’s go with Cleopatra VII, the last Pharaoh of Egypt.”

—Barney Cox, Senior Marketing Executive

Barney Cox. Used with permission.

Barney Cox. Used with permission.“Michael Pollan, so we could spend ten hours talking about food and then exit the elevator to gorge ourselves on local eats.”

—Georgia Brodsky, Assistant Marketing Manager

Which fictional literary world would you most like to inhabit and why?

“Lyra’s world in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy—I would love to know what animal my dæmon would be!”

—Hannah Charters, Associate Marketing Manager

“I’d live in Dorne in Game of Thrones, preferably in the Water Gardens, whilst steering clear of all the beheadings, poisonings, and massacres. The buildings are beautiful, everyone dresses stylishly, and I bet the food would be good too (although I’d pass on the grilled snake). Plus, winter is coming and I want to be somewhere warm.”

—Barney Cox, Senior Marketing Executive

“I would inhabit the fictional literary world of Alice in Wonderland because I think abstractly and have an avant-garde mind suited for that distorted realm.”

—Miki N. Onwudinjo, Junior Level Marketing Coordinator

“Gatsby’s home and grounds, right at the beginning of a cocktail party, when everyone still has their wits together. I can’t imagine anything more glamorous.”

—Georgia Brodsky, Assistant Marketing Manager

What website do you visit most often in your spare time and why?

“Colossal. It is an art and design blog that always inspires me (and I want to own everything in their store).”

—Erin Fegely, Assistant Marketing Manager

“Does Netflix count? I choose Netflix. I don’t know what I did before Netflix, I probably just stared at my living room wall.”

—Barney Cox, Senior Marketing Executive

“I visit Reddit too much in my spare time for the AMA’s and NoSleep scary stories. Reddit has the weirdest and most interesting stories and first-person accounts.”

—Miki N. Onwudinjo, Junior Level Marketing Coordinator

“New York Times Most E-mailed articles. To see what people are talking about!”

—Georgia Brodsky, Assistant Marketing Manager

What was the last book you read?

“The Story of B by Daniel Quinn.”

—Sam Zimbler, Marketing Associate

Samantha Zimbler. Used with permission.

Samantha Zimbler. Used with permission.“The Lowlands by Jhumpa Lahiri. It’s beautifully written.”

—Victoria Davis, Assistant Marketing Manager

“The Dinner by Herman Koch. Sold as “the European Gone Girl” and set in one of my favourite cities, Amsterdam, this book is a dark and suspenseful summer read.”

—Erin Fegely, Assistant Marketing Manager

“American Gods by Neil Gaiman. I bought this a few years ago and it had been sitting on my bookshelf in all its black-and-gold glory until a few weeks past when I finally decided to give it a go. I really enjoyed it! I love the concept of old gods wondering around America, driving taxis and running funeral homes because nobody believes in them anymore. Also, fun fact, Neil Gaiman once signed my copy of Coraline with a picture of an angry mouse.”

—Barney Cox, Senior Marketing Executive

“120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade.”

—Miki N. Onwudinjo, Junior Level Marketing Coordinator

“The Whole World Over by Julia Glass.”

—Georgia Brodsky, Assistant Marketing Manager

Image Credit: “Power Cut” by Graham Holliday. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Getting to know the Online Product Marketing Team appeared first on OUPblog.

Stanley Milgram: Life and legacy

Stanley Milgram was born on the 15 August 1933. In the early 1960s he carried out a series of experiments which had a significant impact not just on the field of psychology, but also exerted enormous influence in popular culture. These experiments touched on many profound philosophical questions concerning autonomy, authority, and the capacity of individuals to do the right thing in difficult circumstances. They were the source of much controversy with respect to both what they proved and to how they were carried out. Follow the timeline below to understand their intellectual genesis, ingenious setup, and controversial legacy.

Headline image credit: Illustration of the setup of a Milgram experiment by Fred the Oyster. CC CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Stanley Milgram: Life and legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

Mullah Omar’s death and the Haqqani factor

The recently-acknowledged death of Taliban leader Mullah Muhammad Omar has prompted a raft of commentary on what this means for the movement, particularly in relation to its ability and willingness to continue engaging in peace talks. But how much can we reasonably know about how the Taliban will move forward, particularly when so much hinges on how the leadership transition unfolds?

At the time of writing, both the rationale for not immediately reporting Omar’s death, and the implications of this delay for the leadership transition process, remain unclear. Although some reports claim Omar died two years ago, the Taliban’s statement on his passing suggests it was more recent. Their claim that Omar lived in Afghanistan for fourteen years would place his death sometime after late May this year (using Hijri calendar approximations), given that this date corresponds to the beginning of the American invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. If the statement more specifically references the date on which Mullah Omar ordered an evacuation of Kandahar in late 2001, the time frame of his death edges closer to the first week of July 2015. This would mean Omar could conceivably have approved or authored his last Eid message, as these typically have a long lead-time and involve input from a range of figures.

We may never know why Omar’s death was not immediately announced, or how the decision to delay was received within the group. In retrospect, it seems clear that the Taliban’s decision to transfer authority for internal and external political affairs to the Political Office may have been driven in part by Omar’s illness, and by the desire to formalise an authority structure (which was not a new initiative but may have taken on greater urgency as leadership instability loomed). What we do know is that the Taliban’s political apparatus has gone into overdrive since Omar’s death was acknowledged, producing a spate of statements and audio-visual materials designed to counteract what it clearly perceives as damaging rumours about how the leadership transition is being handled.

Statements released by the group show that it is concerned about perceptions of cohesion and unity, not only within the rank and file but also among a younger generation of field commanders who are growing in influence. How empowered they feel to shape the movement or to remain within its ranks will be key in determining how the group fares during this time of transition and challenge. Maintaining appeal for this younger generation may go some way towards explaining the appointment of Sirajuddin Haqqani as Deputy Leader. Preserving and growing the narrative that the Taliban is incorruptible and operates in the service of the Afghan people, unlike the Afghan government (a key element in the ability of the group to gain and maintain local level support), will also be key to keeping the rank and file in check, growing its influence, and pushing back against ISIS.

But for now stability is paramount. As the Taliban’s history tells us, disagreement and discord will be kept out of public view wherever possible. The release of a letter by Mullah Abdul Qayyum Zakir of the Taliban Leadership Council disputing claims that he and others challenged the leadership process is therefore particularly noteworthy.

Perhaps most significant of all, however, is the release of a rare statement by an elder of the Afghan Jihad, Jalaluddin Haqqani, one of the most influential figures in the milieu and a staunch Taliban ally, whose son Sirajuddin was elected as Deputy to the newly appointed Leader, Mullah Akhtar Muhammad Mansur. Haqqani’s support has long been crucial to the Taliban’s survival. In fact, his decision to allow the Taliban access to territory under his control in the early 1990s, rather than ordering his mujahidin to fight its forces, was key to the group’s survival and expansion. His sanction now, and the influence of his son as a new Deputy, may well prove crucial to the Taliban’s fortunes.

In his statement, Haqqani was careful to stress his view that new leader Mullah Mansur was appointed in a legitimate manner and was suitable for the position, calling on junior and senior figures to pledge their allegiance and obey their new leader. Haqqani also gave reassurances that his mujahidin would obey Mansur as they had Omar before him, and pointedly recommended to ‘all members of the Islamic Emirate’ that they should ‘maintain their internal unity and discipline’ because the defeat of the enemy (the Afghan government) was near.

There was no mention in Haqqani’s statement of peace talks. His reference to the defeat of the enemy may be a sign that he, and perhaps by extension his son Sirajuddin, are positioning themselves against future peace talks. Managing this tension within the Taliban will be a key challenge for unity and cohesion. But if need be, the Taliban can afford to step back from talks; its strength is growing rather than weakening. It may be pressured to do so by field commanders whose own positions are growing stronger. The leadership transition process may therefore see the Taliban’s participation in peace talks scaled back as it turns its attention towards negotiating, maintaining and consolidating unity and cohesion both in its ranks and with its allies.

Agreement on the peace process was always going to be difficult and, with Mullah Omar’s death and a newly appointed leader, it has potentially been made more so. Yet it may well be that because of this difficulty we will come to know more about Mullah Omar’s death. If Omar was, in fact, alive and did approve his last Eid message, which outlined precedent and legitimacy for peaceful interaction and talks as well as the establishment of a Political Office, the Taliban will have an interest in revealing this, as a means of legitimating further engagement in peace talks.

A version of this article originally appeared on the Hurst Publishers blog.

Featured image: Mountain ranges in Sar-e Pol, Afghanistan. U.S. Geological Survey. Public domain via USGS Flickr.

The post Mullah Omar’s death and the Haqqani factor appeared first on OUPblog.

A comma in Catullus

“I was working on the proof of one of my poems all the morning, and took out a comma. In the afternoon I put it back again.” –Oscar Wilde

Only Oscar Wilde could be quite so frivolous when describing a matter as grave as the punctuation of poetry, something that causes particular grief in our attempts to understand ancient texts. Their writers were not so obliging as to provide their poems with punctuation marks, nor to distinguish between capitals and small letters. If modern editors wanted to recreate the ancient reading experience, we ought to print texts in capitals throughout, with no punctuation or even spaces between the words; but our readers would probably not thank us for doing that. So in our editions we have to make choices about punctuation and the like, based on our understanding of what the texts mean. And if Oscar Wilde could be perplexed by the placing of one of his own commas, we should not be surprised if we sometimes misinterpret the articulation of ancient texts – sometimes with unfortunate results.

The longest poem by Catullus (c. 84-54 bc) contains an account of the wedding of the Greek hero Peleus to the sea-goddess Thetis – a key event in mythological history, which led to the birth of the greatest Greek warrior, Achilles, and (thanks to the intervention of Eris with her golden apple) to the Trojan War in which he would win fame. In one part of the work the Parcae (Fates) describe Peleus’ future to him, opening their song with the following address (64.323-6):

O decus eximium magnis uirtutibus augens,

Emathiae tutamen opis, clarissime nato,

accipe, quod laeta tibi pandunt luce sorores,

ueridicum oraclum

O you who augment your outstanding fame through your mighty

deeds,

Protector of the might of Emathia [i.e. Thessaly], most famous through

your son,

Receive the truth-telling oracle, that the sisters reveal

To you on this happy day

At least, this is how the passage appears in the Oxford Classical Text of 1904, edited by Robinson Ellis. In line 324 he prints a modern emendation, clarissime, ‘most famous’; the manuscripts of Catullus read carissime, which would give ‘most dear to his son’, a senseless phrase, since Peleus at the time of this address is childless. Some half a century later, Roger Mynors in his Oxford Classical Text of 1958 – still the standard text of Catullus, and recently published in Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (or read the translation) – printed a different version of the second line, as follows:

Emathiae tutamen, Opis carissime nato

Protector of Emathia, most dear to the son of Ops

If modern editors wanted to recreate the ancient reading experience, we ought to print texts in capitals throughout, with no punctuation or even spaces between the words

Mynors’s new edition retains the text of the manuscripts (carissime) and, for its punctuation, adopts a suggestion made by A. E. Housman in 1915. By placing the comma before opis rather than after it, and by capitalising that word to make it a proper name, Housman restores what must have been Catullus’ intended meaning, and avoids the need to emend the text. Instead of the flabby phrase ‘Protector of the might of Emathia’ (as Housman remarks, “the might of Emathia did not need protecting: it was itself a protection”), we get the tighter ‘Protector of Emathia’. More crucially, the meaning of the second half of the line is now clear. Ops was a Roman goddess identified with Rhea, mother of Jupiter; so Catullus is saying that Peleus was ‘dear to Jupiter’, recreating in Latin the Homeric epithet διίφιλος (Iliad 1.74 etc.). Peleus was indeed dear to the gods, in that he was allowed to marry a goddess; and since Jupiter himself had previously expressed a personal interest in Thetis, it could be said that he showed Peleus particular favour in withdrawing his claim. This very point is made earlier in the poem in another invocation of Peleus, which is recalled by our passage as interpreted by Housman (64.26-7): Thessaliae columen Peleu, cui Iuppiter ipse, | ipse suos diuum genitor concessit amores (“pillar of Thessaly, Peleus, to whom Jupiter himself, the very father of the gods, conceded his beloved”).

So an apparently trivial change of punctuation allows us to understand a passage of ancient poetry, that had frustrated scholars and readers for centuries. No wonder C. J. Fordyce (not a man given to hyperbole), in his commentary on Catullus published by Oxford University Press in 1961 and recently added to Oxford Scholarly Editions Online, called this “the most spectacular contribution of modern scholarship to the interpretation of Catullus”. Or as A. E. Housman said elsewhere – not in real life, but as the character of that name in Sir Tom Stoppard’s The Invention of Love – “There is truth and falsehood in a comma.”

Featured image credit: Man sailing a corbita, a small coastal vessel with two masts by Marie-Lan Nguyen. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A comma in Catullus appeared first on OUPblog.

Amartya Sen on the Modi government, education, health care, and politics

“I had been out for a walk and got caught in the rain,” says Sen, smiling as he walks in to greet us. His knees do not permit him to pedal around Santiniketan as he once did. He is in a pleasant mood, in spite of the controversy surrounding his ouster from Nalanda University and his latest book, The Country of First Boys: And Other Essays, out next month.

The din he created on being forced to step down as chancellor of the university ensured that George Yeo, member of the Nalanda University governing board and former Singapore foreign minister, was chosen as his successor, instead of a “hindutva” person. The furore, however, cost Sen precious time to work on his next book, an expanded edition of Collective Choice and Social Welfare.

A strong critic of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Sen has accused the government of clamping down on academic freedom and imposing hindutva ideology on institutions that should otherwise be autonomous. Under Modi, says Sen, government intervention “is much more extensive, politically organised and connected with the hindutva movement.”

Sen’s stint in India is coming to an end; it is time to return to Harvard. But he will be back soon—he visits India five times a year, and spends a couple of months at Santiniketan. “It is my favoured place for everything—walking, talking, writing, listening to music… everything,” he says, smiling. Excerpts from the interview:

You have talked about the need for good education and primary health care. The Modi government has slashed spending for both.

It is not just this government, even the last government was terrible. The neglect of the need for the state to get everyone schooled and literate, and getting everyone some kind of health cover began much earlier during the time of [Jawaharlal] Nehru. If you look at the Five-Year Plan, there were statements that education and health were top priorities, but not much was done. The entire tradition of Indian planning, of ignoring education and health care, continued through Indira Gandhi’s time, the Janata Party government and, later, through the BJP government and UPA I and II. Now, with Modi, it has got worse, because the government has made further cuts.

You have spoken about how Kerala has achieved success in terms of literacy and public health care, compared with states such as Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh.

You can deliver education and health care to all, even with a very poor economy, because a poor economy is also a low-wage economy, and education and health care are labour-intensive. So, first, it is affordable; and second, it will immediately have an impact on quality of life, infant mortality, etc. And, if you push money towards complete immunisation, it would lead to a better standard of living. Third, it would also improve the productivity of labour, because you can’t become an industrial giant with an unhealthy, uneducated labour force. Ultimately, improvement in the quality of labour has an effect on economic growth.

Do you feel that the current government has repackaged old UPA schemes?

That is a political way of putting it, which, perhaps, Rahul Gandhi should say (laughs). I would say the Modi government has not brought about any change. It has spent far too little on education and health care, and hardly any time on organisation of schooling and health care. They have done very little for immunisation; India ranks one of the lowest in the world [in vaccination coverage]. Furthermore, Gujarat is one of the worst performers; in fact, way below Bihar, which shows that the BJP thinking, which is very Gujarat-dominated, has not gone in the direction of immunisation, unlike Bangladesh, which has gone for total immunisation.

The BJP is led by the hindutva view, but it also supports business. The business community is dependent on trained, educated and healthy labour force. They [the business community] could have easily made that into a big issue; which, with a greater imagination, the PM himself could have done.

Modi’s imagination doesn’t quite go in that direction. He has been quite imaginative in diplomacy. He has rebuilt relations with other countries, including China. On the other hand, they [BJP leaders] are too tied up with the Gujarat model, which is physical capital and easy business, while ignoring human capital and capability, and gender inequality.

The Modi government has started programmes such as ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’, Swachh Bharat, insurance for poor, etc.

These are slogans. How much money and effort has Modi spent on the programmes? He has also said that every house should have a toilet. What has happened to that? One has to distinguish between slogan and action.

Even industry isn’t quite as euphoric as before.

I do believe that India needs more economic reforms. Business is still very hard to do. When I was in charge of Nalanda [University], any change there needed the approval of six different ministries.

You have said that government interference in academia is a worrying sign.

There has to be a distinction between a public institution, which is autonomous but accountable, and an institution ‘owned’ by the government. In the first case, the government, on behalf of the state, can support certain institutions and make sure that the criterion of accountability is being met. In the second instance, the government actually owns public institutions and can command it, and that is a very different idea.

Earlier governments, too, confused one model with the other. I believe they did it sporadically, and there was a kind of transgression. That is not new. What is new is that this [interference] has become much more extensive, much more politically organised and connected with the hindutva movement; and it is at a scale that dwarfs previous history.

A version of this article first appeared on The Week. An extract is reprinted here by permission.

Featured image: Delhi road. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Amartya Sen on the Modi government, education, health care, and politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers