Oxford University Press's Blog, page 625

August 26, 2015

Industrial policy in Ethiopia

The ‘Africa Rising’ narrative means different things to different people. Yes, Africa has performed better in the last decade. But views diverge on the drivers of growth and on its sustainability, and on whether this growth will translate into structural transformation. For instance, the recent fall in oil prices has laid bare the vulnerability of some African economies, suggesting lack of diversification. At the very least, growth has been uneven among regions and countries. The ‘Afro-euphoria’ of recent years is as removed from reality as its equally over-wrought predecessor, blanket ‘Afro-pessimism’.

To get a truer picture, one has to look at specific sectors and policies in a single country. This is what I have done, with the eyes and ears of a policy-maker who has taken time out to undertake detailed research. Ethiopia is widely regarded as one of the poster children of Africa’s renaissance and economic transformation. With more than 90 million people, it is the second most populous country in Africa. Its economy has been growing at about 11 per cent over each of the past 12 years, primarily driven by agriculture, and without any resource boom such as oil or minerals. GDP per capita has increased four-fold, the number of people living below the poverty line has halved, and life expectancy has increased by 19 years to 64. The country has achieved this after facing down many of the woes that have beset the continent ‒ and fuelled Afro-pessimism ‒ for decades: totalitarian military rule, famine, civil war. On top of all this, it is landlocked. Yet it remains a beacon of change in an unstable ‘bad neighbourhood’.

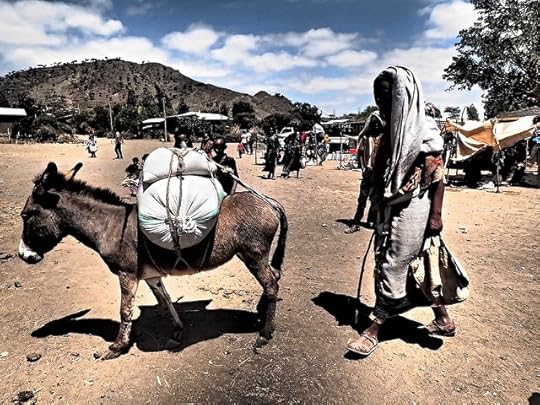

Image credit: Walking to the market, Ethiopia, by SarahTz. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Walking to the market, Ethiopia, by SarahTz. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.What has changed to make this possible? Is this growth trajectory a blip or will it really lead to catch-up? Perhaps it is too early to say. But clues lie in the government’s single-minded focus on developing and transforming agriculture as a foundation for economic take-off. This has enabled Ethiopia to now shift focus to manufacturing with a view to becoming the leading manufacturing powerhouse in Africa by 2025 through a carbon neutral strategy. The manufacturing sector will have to grow by 25 per cent annually if the overall vision is to be achieved, and manufacturing exports will have to expand dramatically.

To encourage manufacturing to expand and play its distinctive role in economic development, the government has put enormous emphasis on publicly funded infrastructure. Currently, Ethiopia spends more than 55 per cent of its federal budget on infrastructure and skills development. This includes building Africa’s largest hydro-power project, funded entirely through domestically mobilized resources; an electric railway system, the first of its kind in Africa; and the ongoing transformation of universities and technical vocational systems so as to support the productive sectors.

The Ethiopian experience shows that learning by doing is just as important in policymaking as in production. Ethiopia has been making bold experiments, based on looking at what works and what does not. With each experiment and experience, policymaking capacity gradually improves. There is no short-cut alternative to learning-by-doing. The key question for many countries is whether they can experiment in the absence of policy independence? Ethiopia has exploited its available policy space, and has consistently followed its own development path. In many ways, its development path has been unique in Africa, diverging from the normal prescriptions of international financial institutions. However, blueprints and naïve ‘lessons from’ approaches are unlikely to work. Ultimately, what determines a country’s catch-up is not geography, ethnic homogeneity, and culture, or ‘good governance’ indices. It is a compulsion to change, and persistence in implementing a strategy while at the same time adapting in the face of mistakes and a shifting context.

Headline image credit: ‘Ethiopia, Eastern Omo-river’, by Rita Willaert. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Industrial policy in Ethiopia appeared first on OUPblog.

August 25, 2015

Cancer science and the new frontier

What is the future of cancer research? In recent years, new developments in this rapidly changing field have delivered fundamental insights into cancer biology. Patient options have not only increased but improved, with thousands of individuals benefiting from these often life-saving discoveries, many of which have been documented by the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, an internationally acclaimed source for original cancer-related research, up-to-date news, and information.

In celebration of its 75th anniversary, Zachary Rathner, Associate Editor of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, spoke with Dr. Leroy Hood, American president and co-founder of the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle, Washington. Dr. Hood, who has made his career on the leading edge of cancer research, has pioneered advances in systems medicine and its applications to cancer, making headway in fields of immunology, neurobiology, and biotechnology. From triple drug therapies to assessing disease transitions, he discusses the potentialities—and challenges—medical researchers and practitioners will face as they forge ahead.

Image Credit: “Sertoli Cell Tumor, NOS” by Dharam Ramnani. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Cancer science and the new frontier appeared first on OUPblog.

America’s mass incarceration problem

The United States holds the world’s largest prison population, but just how deep does our nation’s system of punishment and containment run? In the Fall 2015 issue of the Journal of American History, which is freely available online, historians examine the origins and consequences of America’s carceral state. These articles discuss how mass incarceration’s effects seep into all facets of American society—economic, political, legal, and social. Process, the blog of the Organization of American Historians (OAH), delves into such perspectives through a series of posts by authors from this special issue.

“Flocatex and the fiscal limits of mass incarceration“ by Alex Lichtenstein

Parallels in punishment between the South’s postbellum and post-civil rights eras

In his article, Alex Lichtenstein draws parallels between punishment in the South’s post-Reconstruction era and post-civil rights era. The New South used a brutal penal system, including chain gangs and convict leasing, to establish economic control and racial dominance. Lichtenstein explores similar trends of radicalized punishment in modern-day “Flocatex” (a combination of Florida, California, Texas). These states are considered “innovators” in a sprawling carceral state. Florida demonstrates a growing reliance on private prison contractors to increase capacity at low costs. California shows a shift from therapeutic punishment to retributive punishment. In Texas, an increase in the infrastructure of punishment has created a new carceral landscape and economy. What can the “peculiar regional political economy” of the post-Reconstruction South teach us about disturbing new trends in the criminal justice system?

“Objects of Police History” by Micol Seigel

Confronting popular conceptions of “the boys in blue”

Imagine your average local cop. On the beat, dressed in blue, patrolling local neighborhoods, armed only with a walkie-talkie and a revolver. Micol Seigel confronts this image in her article, “Objects of Police History,” which explores the life and death of a federal agency, the Office of Public Safety (OPS). Established by John F. Kennedy in 1962, OPS sent American officers abroad to Cold War hotspots to instruct foreign police on “professional methods.” Their tactics were often violent and politicized, blurring the lines between civil servants and militarized officers. OPS globalized the US police, creating lasting trends of counterinsurgency, militarization, and privatization. Our quaint concept of local cops may no longer be valid, as Seigel points out that America’s police now “regularly leap territorial borders, blend civilian and military features, and serve private interests.”

“Police” by Anja Osenberg. CC0 via Pixabay.

“Police” by Anja Osenberg. CC0 via Pixabay.“Less Crime, More Punishment“ by Jeffrey S. Adler

The crime and punishment paradox in America’s interwar period

Jeffrey Adler examines a “curious, counter-intuitive relationship” in America’s legal system between World War I and World War II. For the first quarter of the twentieth century, America’s violent crime rates skyrocketed while incarceration rates remained low. Then something changed. Between 1925 and 1940, crime and punishment began to move in paradoxically opposite directions. Adler focuses on Chicago and New Orleans, where plunging crime rates met markedly rising incarceration rates. During the course of this “war on crime,” law enforcement began to disproportionately target African Americans, causing an exploding African American prison population and—as Adler argues—foreshadowing our current carceral state.

“Queer Law and Order” by Timothy Stewart-Winter

The gay community and the fight against police harassment

“What happens if we view the history of the lesbian and gay rights movement in terms of its relationship to the criminal justice system?” Timothy Stewart-Winter addresses this question in his article, “Queer Law and Order,” which traces the history of sexuality alongside the emergence of the carceral state. The gay community struggled with police harassment in the 1960s and 1970s with routine police raids on gay bars. Patrons of these bars—mainly white, middle-class men—sought liberal allies. They aligned themselves with the African American community and other minority groups fighting against harsh policing tactics. Getting police out of gay bars was an important milestone, but Stewart-Winter says that the victory caused a shift in priorities away from battling police brutality, and fellow minority groups lost an important ally.

Image Credit: “Prison” by Barbara Rosner. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post America’s mass incarceration problem appeared first on OUPblog.

Space, place, and policing [interactive map]

“For policing scholars, space, places, and the physical and social environment have served as significant contextual backdrops,” state Cynthia Lum and Nicholas Fyfe, special editors of the Policing Special Issue.

To mark Policing’s new collection on “Space, Place, and Policing: Exploring Geographies of Research and Practice”, we’ve put together a map showcasing the global and place-based approaches the journal’s contributors have taken towards policing research. The development of crime pattern theories along with technologies, including computerized crime mapping have provided police researchers and practitioners with further understanding of the causes of crime and a fresh perspective on how to address these issues.

Explore the map below to discover 15 articles from Policing’s archive on geographical approaches to policing and its research. Click on each pin to discover an article focused on, or researched at, that location.

Featured image: May Day March and Occupy Chicago by Mikasi. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Space, place, and policing [interactive map] appeared first on OUPblog.

Good health is a creative act

Musicians lead demanding lives. Practicing, sight-reading, rehearsing, and auditioning all can be stressful and, at times, actually painful. How to stay healthy and free from pain? I think the answer lies in realizing that your health is completely tied in with your creative efforts, or the way you respond to music itself. In brief, good health is a creative act. Here are seven tips to get you started.

To be a musician is to speak the language of music. When you think of yourself as a musical storyteller, your performances become lively and interesting. Let’s suppose you’re a string player. Your bow can travel back and forth along the string because you mentally say, “Elbow: open; elbow: close.” These are physical commands. Or the bow can travel back and forth because you mentally say, “YES, yes, YES, yes.” These are linguistic commands, rather than physical ones. To every bow stroke there might correspond a word or a syllable. The words and syllables can be banal or clever, soppy or cynical, in English or in Italian, literary or gibberish. The main thing is for you to appreciate the difference between physical and linguistic commands, and develop the art of integrating them in your every gesture.

Imagine you’re walking down a dark corridor with low ceilings above your head and wobbly wooden boards under your feet. Every step you take requires you to make physical decisions with psychological and emotional components. Coordination, then, requires a nimble mind and a steady heart. This may be obvious when you’re walking that dark corridor, but it also applies to playing a scale at the piano or turning a page when sight-reading a score. Body and mind together, right here, right now.

The primary dimensions of music are rhythm and sound. Bringing them into life requires the participation of your body as you move in space. It’s useful to think of coordination, rhythm, and sound as being completely interdependent. Would you like to improve your sound? Then become aware of how you’re coordinating yourself when you sing and play. Would you like to release tight shoulders? Sense the beats and beat subdivisions of the pieces you’re performing, and let rhythm itself (rather than muscular effort) drive your music making.

Pedro’s violin. Courtesy of Pedro de Alcantara.

Pedro’s violin. Courtesy of Pedro de Alcantara.You can improve your playing or your singing by working on your coordination away from the practice room: tango lessons, Tai Chi, Alexander Technique. There are many wonderful ways of opening up your perception, making friends with your legs and feet, or just enjoying the physicality of moving in space. When you watch Artur Rubinstein at the piano, you can’t help but imagine that he must have been a fabulous ballroom dancer too.

You can improve many aspects of your music making through indirect means. Suppose you’re a pianist and you’re working on a piece by Maurice Ravel. Attend a French film festival. Listen to the French language whether or not you understand it. Suss out the rhythms of spoken and sung French. Listen to Edith Piaf or Charles Trenet singing French hits from decades past. It’s possible that your playing of Ravel might become a bit more fluent, or a bit more coherent, or a bit more idiomatic – without your having to spend endless hours repeating passages from the actual piece you’re learning.

Who were the great violinists of the past? Niccolò Paganini, Henri Vieuxtemps, Henryk Wieniawski, Ole Bull, Eugène Ysaÿe, and George Enescu, to name a few of the best. What did they have in common? They were all composers as well as instrumentalists. The same would apply to flutists, cellists, or pianists. Even if you aren’t a trained composer, it’s useful to be a performer who thinks like a composer, that is, who performs with an understanding of how a composition unfolds. Take a phrase from something you’re preparing for performance. Improvise versions of it, some simpler than the original, others more complex. Improvise a version so simple that it resembles a scale. Now play the following sequence: a scale, a simple tune that resembles a scale, a simple tune that is a compromise between a scale and the phrase from your concert piece, the phrase from your concert piece. You’ve now become the composer of the piece you’re playing.

The playwright Noël Coward is credited with saying, “Work is more fun than fun.” I’m not sure what he meant by it, but all I know is that working on the multidisciplinary skills of making music (and this includes attending French film festivals and taking tango lessons) is tremendous fun.

Featured image: Violin. (c) carroteater via iStock.

The post Good health is a creative act appeared first on OUPblog.

The top ten films all aspiring lawyers need to see

Preparing for law school doesn’t have to be purely academic; there’s plenty you can learn from film and TV if you look in the right places. We asked Martin Partington, author of Introduction to the English Legal System, for his top ten film recommendations for new law students and aspiring lawyers. Iconic cases, legendary lawyers, fact and fiction – which films would make it on to your list?

1. Twelve Angry Men (1957)

This US film is set in the jury room, where 12 jurors have to decide the outcome of a seemingly open and shut case. In the UK, no one knows precisely what goes on in the jury room. Direct participant research is prohibited by law. So dramas like this offer a version of what might happen. One question to ponder: how do you think the verdict might have differed if the jury had been told it could reach a majority verdict (possible in England and Wales) rather than a unanimous one?

2. The Paper Chase (1973)

Another US film features a first year law student’s experience of taking a class in contract under the supervision of the fearsome Professor Kingsfield. It shows how the much vaunted socratic method of legal education – where students are fiercely quizzed by their professors – works in practice. You may end up relieved that your course is demanding in different ways! The intellectual limitation of the film is the suggestion that all legal education is about textual analysis of cases and statutes. It takes no account of the social importance of law. For a different take on the law school experience, you could try Legally Blonde (2001).

3. In the Name of the Father (1993)

Image Credit: ‘To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)’, Trailer (Cropped Screenshot), Image from Universal Pictures, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)’, Trailer (Cropped Screenshot), Image from Universal Pictures, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons.This is an Irish-British-American film based on the story of the Guildford Four, four people falsely convicted of the 1974 IRA‘s Guildford pub bombings, which killed four off-duty British soldiers and a civilian. The story is important as it formed part of the background to major changes in the criminal justice system of England and Wales, including the creation of the Criminal Cases Review Commission and the Crown Prosecution Service. Warning: its portrayal of the trial process is a travesty of reality – it should not be taken as any sort of representation of what happens in practice.

4. To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

Based on Harper Lee’s classic novel, this tells the story of attorney Atticus Finch’s defence of a black man falsely accused of rape. The recent publication of Harper Lee’s follow up novel Go Set a Watchman brings a new dimension to the tale. How does the new book change your perception of Finch?

5. Erin Brockovich (2000)

A great ’cause lawyering’ film. A clerk in a small law office pursues an action against a huge corporation, suspected of widespread land pollution. It’s a pity no similar UK film was made about the Sunday Times classic investigation into the thalidomide drug.

6. Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)

Post World War 2 trial of 4 Nazi judges, accused of using their position to support German state goals of cleansing the country of Jews. Worth seeing both for its own sake, but also as the back drop for the more recent creation of International Criminal Tribunals charged with the hearing of cases against those accused of war crimes.

7. Reversal of Fortune (1990)

Image Credit: ‘Noose’, Photo by Patrick Feller, CC by 2.0, via Flickr.

Image Credit: ‘Noose’, Photo by Patrick Feller, CC by 2.0, via Flickr.Based on a true story it centres on the appeal by Law Professor Alan Dershowitz in the case of Claus von Bulow, a wealthy Dane found guilty of the attempted murder of his wife. An interesting film: not least because it shows the engagement of legal academics in real litigation – something which does not often occur in the UK.

8. 10 Rillington Place (1971)

A film about the trial for murder of Timothy Evans: one of a number of high profile miscarriage of justice cases that ultimately led to the abolition of the death penalty in the UK in 1965. Worth watching as a reminder of why the death penalty needs to remain abolished.

9. A Separation (2011)

Iranian film focusing on an Iranian middle-class couple who separate, and the conflicts that arise when the husband hires a lower-class care giver for his elderly father, who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease. I’ve included it here because it features some proceedings before courts in Iran, although it is hard to know how accurate the representation of the working of the Iranian court system truly is.

10. 10th District Court (10e Chambre – Instants d’Audience) (2004)

Documentary on the work of a Paris Criminal Court. Worth viewing to compare how the French criminal justice system operates to the work of Magistrates’ Courts in England and Wales.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Hammer, Books, Law’, Photo by succo, CC0 Public Domain, via Pixabay.

The post The top ten films all aspiring lawyers need to see appeared first on OUPblog.

August 24, 2015

The new intergovernmentalism and the Greek crisis

Just as some thought it was over, the Greek crisis has entered into a new and dramatic stage. The Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, has declared snap elections to be held on the 20th September 2015. This comes just as the European Stability Mechanism had transferred 13 billion Euros to Athens, out of which 3.2 billion was immediately sent to the European Central Bank to repay a bond of that amount due on the 20th August. Tsipras has calculated that with public backing for the third bail-out, he can use the election to rid himself of the Left Platform faction within Syriza, which has been vigorously opposing the bail-out deal. He can then recast himself as a more centrist figure, whilst Left Platform re-launches itself as an anti-austerity, anti-bailout party.

What might the new intergovernmentalism have to tell us about the Greek crisis? It is always tricky to use theories to explain a moving target, especially one as protean as the Greek crisis, but there are at least three insights into the crisis that the new intergovernmentalism can provide us with.

The first is an explanation for Syriza’s failed attempt at renegotiation with the Troika. There is still some hope of debt relief for Greece but almost all of what Tsipras had promised to achieve when he was elected in January this year has been left by the wayside. The key reason for this failure is that both Tsipras and Yanis Varoufakis, the former finance minister, wildly over-estimated the appetite in Europe for more supranational integration. They came to the negotiations with the view that – in the name of a more solidaristic European Union – they might convince creditors to ease the burden on Greece. They argued that the crisis in Greece was not only the result of Greek profligacy; other member states, and especially those with banks that had lent to Greece in the boom years, needed to shoulder some of the blame. Sharing the blame, sharing the burden, and recasting Europe as a more socially-minded and integrated political community: this was the hopeful message of Syriza.

It fell on deaf ears, to say the least. Mildly supportive remarks early on from the likes of François Hollande and Matteo Renzi were soon drowned out by more hostile demands that Greece toe the line and pay back all its borrowed Euros. Underlying resistance to the Greek message was a refusal to accept its supranational implications. The new integovermentalism argues that post-Maastricht European integration is based on an “integration paradox”: a significant expansion in the scope and depth of EU integration but without definitive and lasting transfers of powers from national governments to supranational EU institution. This paradox fits with the Greek bail-out deal. EU integration has moved forward as instruments – such as the ESM – are strengthened and new ones are created. But there is no heady flight towards fiscal union or any real burden-sharing. The language of European responsibility and solidarity deployed by Syriza is empty rhetoric, unmatched by any political wish or will on the part of the EU’s member states.

Another insight the new intergovernmentalism provides is about why – in the course of the last six to eight months – Yanis Varoufakis became a persona non grata. Appointed finance minister after the January elections, Varoufakis toured European capitals in an attempt to drum up support for his plan for reforming the Eurozone. He attended all the Eurogroup meetings, making the same case behind closed doors that he was making to newspapers, blogs and anyone who would listen. He was described by his admirers as charismatic and handsome and was probably the only Eurozone finance minister to have his own (shortlived) Tumblr account created by his fans, entitled ‘Varoufakis Doing Things’.

For all his efforts, Varoufakis became in the space of just a few months public enemy number one for the Eurogroup. He was first side-lined by Tsipras as a condition for the continuation of talks between Greece and its creditors. He then resigned of his own accord, though it was clear he would have been kicked out had he not gone first. Why did Eurogroup finance ministers end up hating Varoufakis so much? Some of the explanation probably lies in the patronising tones he used to address his political peers. He saw the whole enterprise as an intellectual activity where the most logically consistent argument wins and there was no doubt he thought his argument was superior to all others. Being lectured by Varoufakis about economics and being asked to hand-over billions of Euros in loans at the same time was too much for people like Schäuble.

A more likely explanation is that Varoufakis openly flouted the guiding norms of the Eurogroup. As argued by the new intergovernmentalist framework, deliberation and consensus have become the key norms of day-to-day decision-making at all levels of EU policymaking including the Eurogroup. As norms, deliberation and consensus are not necessarily democratic; that depends on the wider institutional setting. The Eurogroup is a closed and private body, with no real legal status in the EU’s treaties. Its deliberative and consensual nature is far-removed from Varoufakis’ notion of presenting demands on the behalf of the Greek people. Acting as an open and unabashed representative of his own people, Varoufakis exposed the Eurogroup’s democratic failings and the other members could not forgive him for it. He had to go.

A final insight provided by the new intergovernmentalism is to do with the febrile nature of Greek politics. It is striking that Tsipras, though elected according to all the procedures of party government in Greece, has understood his power in a plebiscitarian way and has sought to renew his mandate at every critical juncture in the negotiations with the Troika. Greek party government is in crisis. The governing parties of Pasok and New Democracy have been either swept away or fatally weakened by their association with the boom and bust of the last decade. What remains are the margins – Syriza, Independent Greeks – that have sought to govern but have done so very conscious of their own weakness. This is why Tsipras has needed to renew his mandate through referenda so often. The new intergovernmentalism tells us that these problems in domestic preference formation – i.e. crises in the political system itself, in the very means by which interests are aggregated together – have become a standalone input into European integration. The EU cannot shield itself from the challenges faced by party government across Europe today. In fact, these challenges have become a constitutive part of the EU integration process itself.

Headline image credit: “We Remain in Europe I” by alk_is. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The new intergovernmentalism and the Greek crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

Why we like to blame buildings

On 27 October 2005, two French youths of Tunisian and Malian descent died of electrocution in a local power station in the Parisian suburb of Clichy-sous-Bois. Police had been patrolling their neighborhood, responding to a reported break-in, and scared that they might be subject to an arbitrary interrogation, the youngsters decided to hide in the nearest available building. Riots immediately broke out in the high-rise suburbs of Paris and in hundreds of neighborhoods across the country. The unrest persisted well into November. The media attributed the widespread violence directly to the living conditions in the drab concrete housing blocks, which often formed the backdrop in images of burning cars and people throwing Molotov cocktails.

Accepted wisdom has it that the continuing social unrest in the banlieues, as these suburbs are called, is a direct result of their built form: repetitive slabs and blocks of modern housing, often in large isolated estates. But this logic—of a direct and causal relationship between the built environment and human behavior—is not at all new. In fact, environmental determinism accompanied the very making of the French suburbs in the postwar period and the development of modern urbanism more generally. Why is it that we assign so much power to buildings?

‘La Dame Blanche (Garges, near Paris) in the early 1960s’ by Roger Henrard. © used with permission from ADVO.

‘La Dame Blanche (Garges, near Paris) in the early 1960s’ by Roger Henrard. © used with permission from ADVO.After World War II, France evolved in less than three decades from a largely rural country with an outdated housing stock into a highly modernized urban nation. This evolution was largely the result of the massive production of publicly funded housing and state-planned New Towns on the outskirts of existing cities. The scale of these developments was unprecedented — tens of thousands of housing units rising simultaneously.

In this development, architecture undertook a whole new role — a social project. It was shared and shaped not only by architects and planners, but also by government officials, construction companies, residents’ associations, real estate developers and social scientists alike. Even with this broad constituency, its logic and language were remarkably consistent. Never before — and not since — were modernization and modernism so pervasive and so closely allied. Never before was modern architecture built so rapidly on such a massive scale. And perhaps never before did entire generations come to believe how much better their lives were than those of their parents — especially in the material realm of everyday experience.

“Sarcelles Lochères, postcard image of around 1960″ © used with permission from Kenny Cupers.

“Sarcelles Lochères, postcard image of around 1960″ © used with permission from Kenny Cupers.The French suburbs were not built in a day or according to a singular principle. To be sure, architects and planners were engaged in large-scale reorganization and modernization; but this hardly implied a unified agenda or one-off implementation. Motives competed and projects conflicted. Crime and violence in France’s mass housing did not erupt only in recent years; female depression and youth delinquency were only the most sensational problems reported by journalists and social scientists at the height of construction during the 1960s. Such concerns accompanied the rapid postwar urbanization, and during this period architecture was not only planned and built, but also inhabited, criticized, studied, modified and revised. Mass housing was not just produced but also consumed, and these processes were intimately intertwined.

“La Grande Borne, Grigny, near Paris, ca. early 1960s” by Fonds Aillaud © . Used with permission from Kenny Cupers.

“La Grande Borne, Grigny, near Paris, ca. early 1960s” by Fonds Aillaud © . Used with permission from Kenny Cupers.In the eyes of many observers today, however, the outcome is a monstrous catastrophe. In recent decades, much mid-century housing has undergone physical degradation and been left to those with no choice to live anywhere else. Today many larger collective projects — especially those built in the 1950s and 60s — are sites of high rates of youth unemployment and crime. More than 700 projects have been officially labeled “urban problem areas” by the French government, stigmatizing more than five million inhabitants, predominantly from ethnic minorities. The continuing unrest in a relatively small number of these deprived neighborhoods (the riots of 2005 and 2007 being the most notorious) has come to symbolize the country’s (sub)urban crisis, and critical observers in France and abroad have decried the contemporary banlieue as emblematic of social and racial apartheid.

How could the architects and planners conceive of placing near-identical towers and slabs in vast, isolated and ill-defined open spaces? With Le Corbusier usually taking the brunt of the critique, three decades of building production have become synonymous with modernism’s failure: its rationalistic hubris, its inflexible and inhumane urbanism, its denial of people’s needs and aspirations. Architects and planners themselves have participated in these virulent critiques; which were not without self-interest — if the origin of social malaise lay in design, so too would the solution. But the problem with handing out blame is not that it would incriminate the wrong culprits, but rather that it reduces the history of a significant part of the urbanized world to a singular error.

In the meantime, historical shortsightedness has helped to legitimize the current policies of massive demolition. The famous footage of Pruitt-Igoe being imploded in 1971 is now shorthand for an approach that can seem the clearest way out of mass housing, and since then it has been demolition, rather than improvement, that has gained purchase. Yet rarely does this do more than simply displace the social problem of poverty; meanwhile the legacy of the golden age of state welfare is disappearing even before it has been properly understood.

Instead of the prevailing assumption of triumphant rise and spectacular fall, the history of the banlieue is one of accumulative experimentation and continual revision. It is not the outcome of a natural evolution, and public housing was not an experiment that was necessarily bound to fail. We like to blame the resulting buildings not only to legitimize certain political choices today, but also to deny the fundamental uncertainty of the present that historical awareness forces upon us.

Featured image: “Housing estate in Saint-Denis”. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why we like to blame buildings appeared first on OUPblog.

Greece: The paradox of power

Why doesn’t Greece reform? Over the past few years the inability of successive Greek governments to deliver on the demands of international creditors has been a key feature of Greece’s bailout drama. Frustrated observers have pointed to various pathologies of the Greek political system to explain this underperformance: the lack of political will; entrenched sectoral interests resisting change; and the irrational allocation of resources skewed by clientelism and corruption. There is, of course, a significant element of truth in all these assertions. Yet, for many outsiders the real elephant in the room remains unnoticed. The endemic weaknesses of the Greek public administration are indeed crucial in understanding much of what has gone wrong over the past 5 years (and before). Back in 2010 the beleaguered Greek government had very little input into its own ‘rescue’. Lacking basic capabilities and running out of time, it almost entirely ‘sub-contracted’ the design of the bailout programme to the IMF, who, by its own admission, grossly overrestimated the capacity of the domestic system to deliver. Unrealistic expectations were built on the assumption that an F1 driver will steer a Ferrari to perfection. In reality, it wasn’t a Ferrari but a rusty Trabant.

Since then there has been a depressing list of blunders that has exposed both the limits of Greece’s governability and the naivety of its creditors. Privatisation targets (set at 50 billion Euros) were pulled out of thin air, only to be discovered that many state assets were marred by legal uncertainties and bureaucratic blockages which greatly diminish their value. Some of the pension and salary cuts (particularly in the public sector) were so poorly implemented that their legality was subsequently challenged in court, resulting in huge bills for the Greek treasury. The control of central government over the finances (and staffing practices) of local authorities still remains sketchy. More worryingly the quality of the legislative process in the Greek Parliament has suffered greatly under the suffocating deadlines of ‘prior actions’ that accompany the release of funds by Greece’s creditors.

Plenary debate on Greece with PM Alexis Tsipras by European Parliament. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr

Plenary debate on Greece with PM Alexis Tsipras by European Parliament. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via FlickrWhilst in they were in opposition, the current governing parties in Greece accused their predecessors of turning the Greek Parliament into a ‘sausage machine’ of bailout laws at the request of the ‘Troika’ of creditor institutions. Now in power, SYRIZA’s leader Alexis Tsipras is facing a similar criticism. His ‘in-principle’ agreement for a third bailout was debated in Parliament for less than a day and all ‘prior actions’ demanded by the creditors were fast-tracked within two weeks.

The PM’s current predicament, like that of his predecessors, reflects deep-rooted weaknesses at the very heart of the Greek ‘core executive’. Despite the fact that a prime minister in Greece possesses formal, constitutional powers that are amongst the strongest in Europe, the centre of government lacks the appropriate resources to coordinate ministry ‘silos’ that operate with a significant degree of autonomy. We explore this discrepancy, the paradox of power between formal strength and operational weakness, in more detail in our latest book. The Greek PM does not have at his disposal a permanent bureaucracy (a ‘Cabinet Office‘) for the coordination of government business. Instead, he is surrounded by political appointees and the operational norms are ones of trust and personal, particularistic contacts, in a setting that lacks effective process and is hopelessly disconnected with the wider public administration. The ‘system’ is devoid of institutional memory and is designed for the short term; rather than the control, coordination and accountability of substantive reform programmes.

All of this conspires to create a false sense of ‘security’ for the Greek Prime Minister. With no mandarins and no bureaucratic gate keepers to contend with, the PM faces few formal barriers on how to exercise his authority. But, in reality, ‘the emperor has no clothes’: he lacks effective systems of management across a public administration that is overly-rigid, has poor skills and technologies, is sometimes corrupt, and whose resources are distributed following political logics of clientelism rather than bureaucratic efficiency. Altogether, the PM sits astride a system of governance that has many dysfunctionalities.

There are important lessons here, for both Greece’s leaders, but also its lenders. Greek prime ministers are apt to discover the limits of their operational capabilities. Greece’s creditors – and the European Union, in particular – are faced with the challenge of how to deal with a partner that lacks the capacity to deliver, even if the political will to do so exists. The book offers the first extensive study of how Greece is governed from the ‘inside’ and is based on extensive interviews and archival materials. It asks a fundamental question in the Greek case – how can a PM establish control and coordination across his government – but the answer has implications of international significance.

Headline image credit: “Greek flag” by Trine Juel. CC BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Greece: The paradox of power appeared first on OUPblog.

August 23, 2015

America’s irrational drug policies

Ten students and two visitors at Wesleyan University were hospitalized after overdosing on the recreational drug Ecstasy, the result of having received a “bad batch.” The incident elicited a conventional statement from the President of the University: “Please, please stay away from illegal substances – the use of which can put you in extreme danger.” But the drug is so widespread that warnings of this sort sound fatuous. A more realistic approach, adopted in many university settings, would be to provide a testing booth where students can check the purity of their Ecstasy supply.

Drug overdoses are certainly a serious danger. Fortunately, the twelve people involved in the incident survived, but, as we all know, there have been many premature fatalities. In recent years, these have included a number people who enriched our lives, such as Corey Monteith, Whitney Houston, Philip Seymour Hoffman, John Belushi, River Phoenix, Janis Joplin and Chris Farley, among others. Moralists will point out that these untimely deaths reveal the danger of illegal drugs, and they do. But they also reveal the dangers of the legislation that makes narcotics and related drugs illegal.

Mind-altering substances, from Ecstasy, to LSD, to heroin and cocaine aren’t good for your body, but they aren’t lethal. They kill only when they are taken in excessive amounts, which generally occurs because they are sold on the street, without adequate control of quality or dose amounts. Many legal substances, including Tylenol and sleeping pills, can kill you if taken in improper dosages. But few people die from them—unless they are trying to commit suicide—since they are marketed by reputable companies in carefully controlled and labelled form. These companies can’t market narcotics, however, because our policy is that selling or taking these substances is a serious criminal offense.

Image credit: ‘Drugs’. Photo by Almond Butterscotch, CC by-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr.

Image credit: ‘Drugs’. Photo by Almond Butterscotch, CC by-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr.The reason for our anti-drug laws, according to their proponents, is that we are trying to protect people from themselves. But declaring people criminals and putting them in prison seems like a peculiar way to protect them. Conviction and imprisonment are designed to punish, that is, to inflict harm; in practical terms, a conviction often ruins one’s career and prison often ruins one’s life. Another claim is that anti-drug laws protect those dependent on the users, such as their partners or children. But even if a person inflicts indirect harm on his or her dependents by using drugs—failing to keep a job for example—it seems unlikely that those dependents are better off if the person is taken to prison and deprived of an entire career. As for using criminal punishment to deter others from undesirable behavior, our society allows the use of only blameworthy persons for this purpose. We might deter poor performance in school by imprisoning children who consistently get failing grades, but we shun such expedients.

It is certainly true that a person who is heavily dependent on a mind-altering drug is likely to lead a sub-optimal existence. But we generally don’t declare people criminals for failing to achieve their full potential. Addicts are not the walking dead; they can have stable and productive lives, at least if they are not hounded and oppressed by the criminal justice system. Perhaps, had they not been opium addicts, William Wilberforce would have succeeded in abolishing slavery in the British Empire ten years earlier, Samuel Coleridge would have written more poetry (although he might not have written Kubla Khan), and Wilkie Collins would have developed another new genre besides detective fiction; perhaps Sigmund Freud would have plumbed further recesses of the human mind if he hadn’t been a cocaine addict and the Beatles would have stayed together and produced another fifteen albums if they hadn’t taken hallucinogens. But all these heavy drug-users contributed to our society, and the people listed above didn’t do so poorly either.

The real reason why we maintain our irrational drug policies is the survival pre-modern morality, which can be described as a morality of higher purposes. According to that morality, people are supposed to serve the state and the society by contributing to the economic order. The defining feature of the substances that have been criminalized—which are after all quite different in their chemistry and their effects—is that they produce enjoyable experiences. This leads to concern that people will spend too much of their lives in a drug-induced haze instead of reporting to work in the office, the factory, and the toll booth.

But these laws are ineffective, they are cruel, they are phenomenally expensive, they corrupt the police, and they unleash savage criminal cartels on our democratic allies such as Columbia and Mexico. We need to distance ourselves from the old morality of higher purposes and embrace the newly developing morality of mental health and human self-fulfillment. For a fraction of the money that we spend in our hyper-aggressive, inhumane ‘War on Drugs’, we could provide treatment for everyone who wanted to escape from an addition. This would be a much better way to control the drug problem. And it would be nice to have Harris Wittels, Corey Monteith, Whitney Houston, Philip Seymour Hoffman, John Belushi, River Phoenix, Janis Joplin and Chris Farley still with us to enrich our lives.

Featured image credit: ‘Pills’. Photo by epSos.de, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post America’s irrational drug policies appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers