Oxford University Press's Blog, page 622

September 3, 2015

Kuwait’s war on ISIS and DNA

DNA testing and genomics is now so prevalent there are national genotyping platforms. Iceland became the first country in history to sequence the genomes of its population. Other countries are lining up.

The Faroe Islands, an autonomous region of Denmark, is sequencing its population of 50k. GenomeDenmark released its first 30 reference genomes. The Genome of the Netherlands project published a reference genome for the Dutch based on 750 genomes from two-parent-one child ‘trios’. Genomic England is working on a 100k genomes project. The US is interpreting a million genomes as part of Obama’s precision medicine initiative. The Korean Genome project aims to sequence all 50 million living Koreans. Yet more countries are sequencing to unravel the secrets of ancestry, such as Wales’s DNA Wales initiative. These national programmes are further complemented by the Personal Genome Project Global Network, now covering the US, UK, Canada and Austria.

Now Kuwait is changing the playing field. In early July, just days after the deadly Imam Sadiq mosque bombing claimed by ISIS, Kuwait ruled to instate mandatory DNA-testing for all permanent residents. This is the first use of DNA testing at the national-level for security reasons, specifically as a counter-terrorism measure.

An initial $400 million dollars is set aside for collecting the DNA profiles of all 1.3 million citizens and 2.9 million foreign residents. The ready date for this unbelievably ambitious database is September 2016. If completed, especially in this short time-frame, it will forever change the history of the use of DNA in society.

Naturally, the announcement by Kuwait is drawing concerns about human rights. The creation of such a database would be illegal in the US or Europe due to privacy protection laws. A growing list of countries have national DNA profile databases but to date are only for criminals. Europe currently prohibits the creation of such a database based on Article 8 (“Right to a private life”) of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

Image: ‘Kuwait from above,’ by Lindsay Silveira. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

Image: ‘Kuwait from above,’ by Lindsay Silveira. CC-BY-ND-2.0 via Flickr.Compliance will be enforced. Refusal to register ones DNA will result in a fine of $33,000 and a prison sentence of year. Submitting a fake sample will be punished with seven. Even temporary visitors may be tested.

Kuwait’s announcement to monitor DNA is part of a larger story of massive local and global change. The Shia mosque attack, which claimed the lives of 27 and wounded 227, provoked Kuwait to declare war on ISIS. Interestingly, Kuwait’s National Assembly passed a law in April that reinstates mandatory military duty for all men once they reach the age of 18. This law comes into effect in 2017.

Of the world’s 196 countries, how many will exceed the necessary threshold of combined priorities, external contingencies and resources needed to invest in national genomics programs now or in the future? How many will have the luxury to take that step unfettered by issues of national security? Or might they all get there in the end? Could Kuwait’s stance and continued attacks by ISIS soon spread DNA profiling measures through to other countries in the Middle East? Or beyond?

In a ranking of countries and dependencies by population size, Kuwait’s permanent population of 3.4 million is the 133rd most populous of 232 entities, the smallest being Holy See with 799 inhabitants. This means a significant number could conduct comprehensive DNA testing for $400 million or far less using comparable estimates. The 46 that have populations under 200k could do so for a fraction of the cost.

Comprehensive DNA testing, or genome sequencing, of countries with small populations is more feasible than expecting China or India to ever introduce blanket surveys. Prohibitive costs still block its use in many countries. Most notably India has been working for years towards a national DNA database to help with the 40,000 cases of unidentified human remains and missing persons it deals with on a yearly basis. Thus, moving to national identification programmes for most seems a long way off.

But times are rapidly changing, especially now that Kuwait has taken a lead. Costs continue to drop, public awareness of DNA profiling is spreading, and political tensions are escalating.

How many countries will have national genomics/DNA-testing programmes in 50 years – and for what purposes – remains to be seen. While health, genealogy, historical context, disaster identification and criminal forensics have driven the creation of innovative national genomics programs thus far, it is now ISIS and the threat of political violence that has motivated radical efforts by Kuwait to harness the power of DNA under dire circumstances. DNA continues to embed itself it all areas of modern society. How might it play a role next?

Featured image credit: ‘Kuwait city at night,’ by Khaleel Haidar. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Kuwait’s war on ISIS and DNA appeared first on OUPblog.

September 2, 2015

Etymology gleanings for August 2015

I received a question about the greatest etymologists’ active mastery of foreign languages. It is true, as our correspondent indicated, that etymologists have to cast their nets wide and refer to many languages, mainly old (the deader, the better). So would the masters of the age gone by have felt comfortable while traveling abroad, that is, not in the tenth but in the nineteenth century? Probably few of them spoke many languages. Skeat, to give one example, was educated in Classics. I assume that his Latin and Greek were active. There is sufficient evidence that he had excellent command of Old French. Unfortunately, most of our information on the lives of prominent linguists comes from obituaries, which give a survey of the deceased scholars’ achievements and very little else. Sometimes they mention the tragic details of their career (for example, Hermann Paul’s and Friedrich Kluge’s blindness for many years or the persecution of Jewish philologists like Sigmund Feist, Leo Spitzer, and Agathe Lasch, to mention only three, by the Nazis). As an old man, Skeat appended to his collection of essays A Student’s Pastime a rather long essay about his work but preferred not to indulge too much in reminiscences. Not everybody had a wife like Mary Wright, who after the death of Joseph Wright (the author of The English Dialect Dictionary) published a two-volume biography of her husband.

The great Scandinavian historical linguists between roughly the years 1860 and 1920 usually studied at German universities and wrote many works in German. This holds for Sophus Bugge, Alf Torp, Hjalmar Falk, and Adolf Noreen. By contrast, all Elof Hellquist’s works appeared in Swedish. This also holds to a very great extent for Axel Kock. The Germans, such as Kluge and his contemporaries, usually could not speak English. The famous exception was Eduard Sievers. He was married to a Scottish woman, and they spoke English at home. His phonetic ear and power of imitating sounds filled people with admiration; he probably had little or no accent in English. The distinguished Dutch etymologist Johannes Franck, a German, was apparently not fluent in Dutch, though as a philologist he knew the language and its history like few others.

Jacob Grimm learned Modern French during Napoleon’s occupation of Germany. I am not sure whether Antoine Meillet, who felt equally at home in Greek, Gothic, Armenian, and Old Slavic (to him they were mere “dialects” of Indo-European), spoke any of them besides French and (probably) Latin. Roman Jakobson spoke Russian and French as a child. His Czech, which became his main means of communication after he left Russia, was excellent, and so was his German. English took center stage in his life after he fled to the United States from the German-occupied Czechoslovakia. He wrote it beautifully but retained a heavy accent. N. S. Trubetzkoy’s education included French, German, and Italian. Yet he could not even read English: for the publications in that language he needed the help of his wife. So this is how matters stand. Many years ago, I started a project titled “Great Linguists,” and I am sorry that its only outcome has been a series of public lectures and a huge box labeled “Personalia” in my office.

At present, the situation has changed. Most linguists, wherever they live, can now speak at least some English, but native speakers of English are seldom fluent in more than the one foreign language they study professionally (for example, German, Swedish, Russian, Spanish, or French). Even fewer can read any Slavic language. However, etymologists usually obtain a smattering of the languages they cite.

I have only a short postscript to what has been written here. In American usage, the word linguist has supplanted polyglot. Occasionally I hear remarks like the following: “You are a linguist, aren’t you? So is my daughter. She had two years of French and went to a Spanish summer camp. You may like to meet her.” I usually demur.

Jean-François Champollion, the father of Egyptology (1790-1832). He was a polyglot and a linguist.

Jean-François Champollion, the father of Egyptology (1790-1832). He was a polyglot and a linguist.Spelling reform

Masha Bell has written that, given spell-checkers and smartphones, most people can now produce tolerably literate texts on their own. In her view, the reform is needed mainly because it will facilitate teaching people to read English. This may be true from a practical point of view, but I have some trouble sharing her attitude. Nowadays, we can live happily while knowing nothing about a lot of things. Even the multiplication table is a useless burden on memory; calculators do math better and faster than people. Likewise, geography can be dispensed with; engine drivers and pilots know where to go without asking us for instructions. Older literature is another irritant: too many words, too many pages, and, in general, who cares? So what is left? Technology, medicine, food science, and political activism? English spelling is more archaic than serfdom and should be reformed because it is antiquated to the degree of being stupid.

Stephen Bett has a few questions and a few suggestions. For example, should we spell speak like speech? In principle, yes. The distinction between ea and ee is a nuisance. And what about scent and sent? No doubt, scent is a bad joke, and so is ascetic. English does not need the letter c, except perhaps in ck (but I am not sure). Cat can be kat (like kitten), especially because we do have Catherine and Kate, along with Kathy and Cathy. The problem is how to implement the reform. That is why I keep repeating that the public should be inured to the change by infinitesimal degrees: first the most innocuous novelties, such as will hardly raise protest, then slightly more conspicuous alterations, and so on. This is the way the boa constrictor deals with its prey: every time the victim breathes out the space in the chest becomes smaller and the coil gets a tiny bit tighter. At some moment, no space for breathing remains. Once people are taught to appreciate our efforts, they may require more radical changes than we today dare propose. But at present we are exactly where we were 150 year ago (with minor progress in American spelling) and have no reason to rejoice.

A proposed logo for Spelling Reform. Try to guess which part of the group represents the reformers and which resembles the public.

A proposed logo for Spelling Reform. Try to guess which part of the group represents the reformers and which resembles the public.Smaller issues

I have received many questions and comments. Some need long answers. I will address them later and devote one more post to bad and other b-d words. Today I’ll comment only on a few minor queries.

Bar “rod, barrier” and spar “pole”

Affinity between these words has often been suggested, and from the formal point of view the picture looks good: the senses match, and s mobile is not a problem. But if I were to write an entry on spar, I would keep it separate from bar for the reason to which I have so often referred in this blog. Since bar is a word of unknown etymology, it is better not to use it in any reconstruction involving other hard words.

Engl. spoke (noun) and Swedish spak “lever”

Our correspondent wondered why in my discussion of spoke I did not mention Swedish spak “lever.” Alongside Swedish spak, we find Norwegian spak(e) and Danish spag(e). I left them out of consideration because all of them are loanwords. Their source is Middle Low German spake, a cognate of Modern High German Speiche “spoke.” Since for “spoke” the Scandinavian languages had a different word, the borrowing retained only the sense “rod; lever” rather than “spoke.” The noun used in English, German, and other languages (spoke, Speiche, etc.) is West Germanic and has no old cognates in Scandinavian.

Ramp

This question came from Minnesota. Though I have heard it many times, I still have no answer. It seems that all over the United States ramp means a slope or an inclined plane joining two different levels (this is the definition all dictionaries give). But in Minnesota ramp designates what everybody else calls parking garage. Why? The incomparably rich Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE) does not have an entry on ramp, which means that even the editors of this encyclopedia of Americanisms missed the distinction that bothers “Minnesotans abroad.” It is not too hard to find a label for such a phenomenon. We are dealing with an association by contiguity: since a ramp is a slope leading to a parking garage, the entire structure also began to be called ramp. The real question is not how such a change could occur but why it occurred only in a small part of North America. My search in books on American usage and linguistic atlases yielded no result. If some specialists in linguistic geography can shed light on this question, I am sure that at least one ramp in Minnesota will be named after this person.

Brave and bereave

Several letters from a German correspondent deal with the semantics of brave and barbarous. People sometimes run into old posts, and it is good to know that those essays are not as evanescent as one might suspect. I’ll comment on only one part of the letters. Bereave (that is, be–reave) cannot be allied to brave. The root –reave goes back to –raub, and its diphthong is incompatible with –rave in brave. Be– in bereave is a prefix, so that it has nothing to do with b- in brave or in barbarous.

Vowel length in Old Engl. maþþum “treasure”

Indeed, there are obvious arguments for a short vowel in this word. But the origin of the long consonant is unknown, while the word’s etymology poses no problems: Gothic maiþms “present, gift,” etc. Whether the long vowel was shortened before a long consonant already in Old English is anybody’s guess. Therefore, conservative reference books give a in the root length.

To be continued.

Image credits: (1) Epicrates Cenchria Cenchria. Photo by KaroH. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Portrait of Jean-François Champollion by Léon Cogniet (1831). Louvre Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for August 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

Prepping for APSA 2015

This year’s American Political Science Association (APSA) Annual Meeting takes place September 3-6 in San Francisco, where over 6,000 of the world’s foremost academic political scientists will gather for four days of lectures, sessions, networking, and scholarly discussion. This year’s theme, “Diversities Reconsidered”, promises to ignite intellectual discussion among all participants while still staying grounded in the current state of the nation’s political climate.

New to APSA 2015 is the 2015 APSA Annual Meeting app, available via the App Store, Google Play, BlackBerry World, or Windows Store, where users can easily access the Event’s Agenda, stay up-to-date with alerts and notifications, and engage socially with other attendees. Not the most technologically savvy attendee? No worries, APSA has included a simple “how-to” guide to get the application up and running on your Smartphone or Tablet and keep you engaged over the course of the conference.

Every year, Oxford University Press authors are honored in APSA’s annual awards ceremony. This year the C. Herman Pritchett Award, given annually for the best book on law and courts written by a political scientist, is being given to Ran Hirschl for his book Comparative Matters. Oxford would also like to highlight the recipient of the Martha Derthick Book Award, author Nancy Burns, for her book The Formation of American Local Governments. Published in 1994, this book is being recognized as the best book on federalism and intergovernmental relations published at least 10 years ago.

APSA dedicates an extensive amount of resources to keeping all of its members “in-the-loop” as to the status of the organization. First time attending the conference? Join APSA for a brief orientation and learn about the capstone sessions and events at the First Time Attendees Breakfast (Thursday, Sept.3 @7:00am). For experienced conference goers, be sure not to miss the Presidential Address (Thurs. Sept.3@6:15pm) where APSA President Rodney Hero kicks-off the 1st night of the annual meeting, setting the tone for the days to come. Of course, what conference day would be complete without an evening of networking, hors d’oeuvres, drinks, and dancing? Join fellow attendees at the Opening Reception (Thurs. Sept 3@7:30pm) and dive into the world of the American Political Science Association.

Have questions for OUP? Stop by booth 310 in the exhibit hall to check out our latest books, journals, and online resources in Politics. Join us to celebrate the premier online resources offered by Oxford with host David Pervin, Saturday, September 5, from 7-8pm in the Franciscan D room. Cocktails and hors d’oeuvres served! Don’t forget to follow @OUPPolitics on Twitter and engage with other users using #APSA15 in your tweets!

Finally, after a day of intellectual stimuli, enjoy all that San Francisco has to offer! Tour of the famed Alcatraz Island. Buy me some peanuts and crackerjacks at a MLB ballgame at AT&T Park, the home of the Giants. This beautiful City by the Bay will have you begging for some more “California Love”. Check the map below for food recommendations, must-see’s, plus all the sights and sounds of San Francisco.

Image Credit: “Untitled” by Sudheer G. CC-BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Prepping for APSA 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about Great Expectations? [Quiz]

Do you know your Magwitch from your Miss Havisham? Your Philip Pirrip from your Mr Pumblechook? Perhaps Dickens’s best-loved work, Great Expectations features memorable characters such as the convict Magwitch, the mysterious Miss Havisham and her proud ward Estella, as Pip unravels the mystery of his benefactor and of his own heart. Now that the third season of the Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group is drawing to a close, test your knowledge of Great Expectations with our tricky quiz.

Quiz image credit: Lace Tulle Skirt by MAKY_OREL. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Featured headline image: Book reading literature classics by MorningbirdPhoto. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How much do you know about Great Expectations? [Quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

“The discovery of a dead body”, extract from The Murder of William of Norwich

The discovery of the mutilated body of William of Norwich in 1144 soon sparked stories of a ritual murder performed by Jews that quickly spread beyond the walls of Norwich. E. M. Rose examines the events surrounding the murder and the ensuing court case, and launches a historical forensic analysis into the death. The following is an extract describing the discovery of William’s body.

The story of the first ritual murder accusation begins with the discovery of a dead body. In March 1144, William, a young apprentice, was killed and left under a tree on the outskirts of Norwich. Finding a dead body is invariably an awkward experience. It raises troubling questions, draws unwanted attention to the finder, and generally entangles the discoverer in costly officialdom and paperwork, not to mention emotional distress. This was particularly true in medieval England, where detailed rules specified the proper procedures for dealing with corpses. Then, as now, homicide was a serious business involving families, communities, courts, and an entire hierarchy of justice. Many considered it advisable to move a dead body elsewhere, bury it quickly, or hope that it might be devoured by animals or consumed by the elements before it was discovered.

When a peasant stumbled upon a corpse tangled in the underbrush not far from a major thoroughfare outside the city of Norwich, therefore, he knew exactly what to do: at first he ignored it. Earlier that same day, another person who came upon the corpse, a Norman aristocratic nun, Lady Legarda, likewise failed to alert the authorities or to take any responsibility. She said prayers around the corpse with her fellow nuns, and then retreated to her convent, apparently untroubled. The presence of birds circling around the cadaver indicated that it lay unprotected in the open. As was typical in many such cases, the ‘first finder’ of the body was actually the last of several people who encountered it, but the first one who was legally obligated to investigate the death. Saint William of Norwich, Anonymous rood screen painting. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Saint William of Norwich, Anonymous rood screen painting. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

On Holy Saturday (25 March) the day before Easter, the forester Henry de Sprowston was shown the corpse while he was riding through the woods in the course of his duties, looking for people who might be making mischief or, more likely, cutting timber without a license. He was patrolling Thorpe Wood on behalf of his ecclesiastical employer, the Norwich bishop and monks. The right to cut lumber was a valuable privilege that was jealously guarded. Wood was used for heating and cooking, for building halls, cathedrals, parish churches, homes, docks, and the boats needed for the hundreds of shiploads of fine limestone brought from Normandy to build Norwich Cathedral and castle. Good English oak was especially highly prized: tree trunks were employed for the construction of heavy beams in houses, halls, and barns, the branches were used to make charcoal or were dried for firewood, the bark was boiled for tannin used in leatherworking, and the fiber beneath the bark could be used to make rope. This was a period of great deforestation throughout Europe as the population expanded and land was cleared for planting, especially around Norwich, one of the fastest-growing boroughs in the country in an already densely populated region. Landlords, therefore, vigorously enforced restrictions on access to woodland.

The forester’s role was judicial and economic as well as agricultural. In a complicated plan to divide one of their major assets, the bishop owned Thorpe Wood, but part had been given to the monks of Norwich Cathedral Priory, the monastery attached to the cathedral. The woods were to be managed for the joint benefit of monastery and bishop, and each had to approve the trees that the other marked before they were cut down. They also had to agree to any timber sales to a third party. The discovery of a dead body on their land was of consequence to the church authorities in their capacity as landowners as well as comforters of the dead youth’s family.

To deflect attention from his own possibly illicit activities, the peasant led Henry de Sprowston to the dead body. Neither the woodcutter nor the forester recognised the young man, and neither could account for how the body came to be in the woods. Henry de Sprowston launched an inquiry into the death, and while nothing apparently came of his investigation, the body was identified as that of William, a young apprentice leatherworker and son of Wenstan and Elviva. The news spread and people from the city rushed to the woods to see what had happened. After William’s uncle, brother, and cousin identified the body, the dead youth was laid to rest with minimal ceremony and no elaborate marker.

Information about William and the resulting homicide inquiry comes from Brother Thomas’s account of the Life and Passions of William of Norwich, which is one of the only surviving texts from the large library of twelfth-century Norwich Cathedral. Thomas arrived at the monastery a few years after the discovery of William’s body and took a passionate interest in the dead boy, for reasons that will become clear. Six years after the murder, Brother Thomas claimed to have pieced together what had happened during the fateful Holy Week of 1144. He set out to prove that William had been killed for his faith, and therefore deserved to be hailed as a saint.

Featured image credit: Norwich Cathedral by Ziko-C. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “The discovery of a dead body”, extract from The Murder of William of Norwich appeared first on OUPblog.

Meta-analysis of animal studies: a solution to animal waste

Animal research has always attracted a lot of attention because it involves the welfare of animals being compromised. Given this pressure, you would expect that animal studies are performed according to the highest scientific standards; however, there are big methodological problems. Many studies don’t use sound practices like randomization and blinding, which are needed to get unbiased results. Almost everything that gets published is claimed to be significant. Unpublished studies may lead to unnecessary replication. All this results in a waste of animals, time, money, and medical resources that could have been used for better scientific purposes. Moreover, patients can become unnecessarily exposed to non-effective treatments. All this reduces trust in animal study results.

Meta-analysis of animal studies may be part of the solution. Why are meta-analyses of animal studies important? In short: meta-analyses promote an efficient use of information. Many animals already have been sacrificed, so why not use this information? You can only spend your time and money once.

In a meta-analysis, multiple small animal studies are combined, which increases the power to answer a research question—for example, questions related to effects in subgroups. New conclusions can then be drawn without using new experimental animals, or if a new study is needed, meta-analysis may provide a solid rationale for its design and sample size. Note that while meta-analyses of clinical trials emphasize the summary effect, the focus for animal studies is often more on exploring the heterogeneity in the results and on the relation between this heterogeneity and study characteristics.

Furthermore, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of animal studies highlight shortcomings, which should lead to improvements. Researchers can improve the conduct of animal experiments with a better understanding of methodological quality and variations in design (such as species, gender, timing of treatment, etc.). Researchers can also apply lessons in efficiency from clinical meta-analysis, using software and steps designed for clinical meta-analyses for animal studies. Patient safety may increase, because errors in the translation of results from animal studies to clinical practice will be reduced. For example, in order to investigate why promising animal gene therapy research for cerebral glioma failed to translate into clinical efficacy, a meta-analysis in animal models was used. Indeed, it identified areas for improvement in conduct and reporting of the studies.

It is important that each scientist who conducts a meta-analysis of animal studies realizes that the quality of a meta-analysis is dependent on the quality of the primary studies. If the purpose of the meta-analysis is to inform healthcare policy or practice, the original research needs to be both applicable and of sufficient quality. Furthermore, it is important that only sensible comparisons are made in order to reduce the risk of false positive findings and diminish heterogeneity. It is therefore important to always conduct meta-analysis in collaboration with an expert from the field.

Meta-analyses of animal experiments may result in new and very valuable information from already-published experiments—and a better future for animal studies as a whole.

Image Credit: “Your life or My PhD?” by Mycroyance. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Meta-analysis of animal studies: a solution to animal waste appeared first on OUPblog.

Wrong again

Unlike fine wine, bad ideas don’t improve with age.

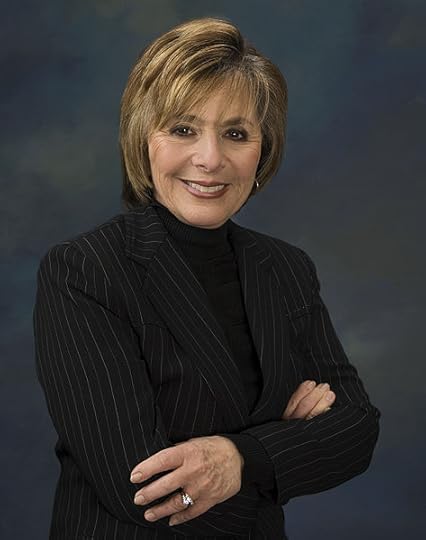

One such idea is the Invest in Transportation Act, co-sponsored by Sens. Barbara Boxer (D-CA) and Rand Paul (R-KY), which would institute a temporary tax cut on profits brought back to the United States by American firms from their overseas operations and use the proceeds to fund investment in transportation infrastructure.

It sounds great. The US corporate tax rate is 35 percent, much higher than rates in other countries, which gives American companies an incentive to keep their overseas profits off-shore and out of the hands of the IRS. The Boxer-Paul proposal would provide firms with a limited-time offer: bring overseas profits home and pay taxes at the bargain rate of only 6.5 percent.

Everyone wins. Firms get to repatriate their profits, which can be used to invest in the United States and create jobs. The government collects more tax, since 6.5 percent of something is greater than 35 percent of nothing. And politicians get to put money into desperately needed transportation infrastructure without having to vote to raise taxes.

Unfortunately, we have been to this rodeo before and wound up with a few hoof-prints on our collective backside as a result.

A decade ago, the American Jobs Creation Act reduced the tax rate to 5.25 percent on profits repatriated by US companies during 2004 and 2005. Firms that took advantage of the law were required to use the windfall to invest in job-creating investment in plant and equipment and research and development.

Senator Barbara Boxer, via United States Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Senator Barbara Boxer, via United States Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.But the law didn’t quite work out as advertised. A Senate report found that the 15 companies that benefitted the most from the law cut nearly 21,000 jobs and slowed the pace of their spending on research and development. Further, they estimated that the law cost the Treasury $3.3 billion dollars over the subsequent decade and called it “a failed policy.”

The Boxer-Paul proposal promises some of the same benefits that the American Jobs Creation Act did, namely that a portion of repatriated funds will be used for job creation, research and development, and investment in green technology. It also mandates—like the earlier law–that firms not use the repatriated profits to increase executive pay, dividends, or stock buybacks. However, an analysis by Jennifer Blouin and Linda Krull in the Journal of Tax Research concluded that firms that repatriated profits under the 2004 law, despite the legislation’s wording and the best efforts of the IRS, did use the proceeds to undertake share buybacks.

The prospect of bringing home profits from foreign operations is attractive. A recent report by Credit Suisse estimated that, as of 2014, S&P 500 corporations had parked more than $2 trillion in earnings overseas. Some of the largest offshore sums were held by General Electric ($119 billion), Hewlett-Packard ($43 billion), Baxter International ($14 billion), and Mattel ($6.4 billion). If all $2 trillion were brought home and taxed at 6.5%, the IRS would collect about $130 billion. Despite these impressive numbers, Washington should not be fooled by the false promise of a tax windfall.

Our transportation infrastructure is a mess. According to the most recent report by the American Society for Civil Engineers, more than 66,000 bridges in the United States are either structurally deficient or functionally obsolete and more than 210 million trips are taken over deficient bridges every day in America’s 102 largest metropolitan areas.

Instead of relying on a gimmick to fund urgently needed transportation infrastructure, our politicians need to deal with the issue head-on. Cut the budget elsewhere, raise taxes, or take advantage of historically low interest rates and borrow the money. None of these will be popular with voters, but they are preferable to the Boxer-Paul plan.

Our corporate tax code needlessly punishes American businesses and encourages all sorts of creative accounting to escape high US corporate taxes. Instead of instituting temporary tax holidays every ten years or so, Congress should reform the corporate tax code once and for all, allowing American firms to use their resources to conduct business instead of gaming the tax system.

You can’t make the same mistake twice. The second time you make it, it’s no longer a mistake. It’s a choice.

Featured image credit: Tioronda Bridge from the west, in disrepair, by Daniel Case. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Wrong again appeared first on OUPblog.

September 1, 2015

Could a Supreme Court justice be president?

Bill Kristol, whose major political contribution to American public life is the national career of Sarah Palin, has another bright idea to free the Republican Party from the looming prospect of a Donald Trump presidential candidacy. The GOP, he writes, should turn to a dark horse from an unlikely source. After naming several long-shot contenders such as Mitch Daniels and Paul Ryan, Kristol essays the presidential equivalent of a two-handed shot from half court. Why not, he inquires, Justice Samuel Alito from the Supreme Court? Never mind that Justice Alito has never expressed interest in the White House and would have to give up his seat to make the race. A man of Alito’s intellect would save the party from the oafish Trump whose slogan on his hat embodies his program to make America great again. Has this potential departure from the Court ever happened before or is the gadfly Kristol innovating again?

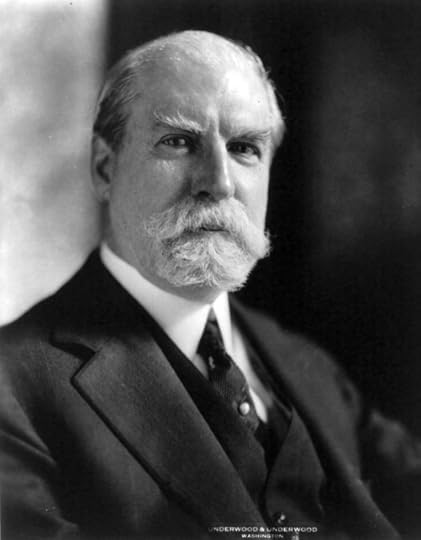

The Republicans faced such a dilemma once before in American history. Against President Woodrow Wilson’s campaign for a second term in 1916, the GOP lacked a strong presidential nominee to counter the resurgence of former president Theodore Roosevelt who hated Wilson, advocated for intervention on the Allied side in World War I, and seemed an unpromising candidate against the sitting president. Several Republican hopefuls pressed to be nominated, but a motley assortment of senators, governors, and also-rans caused no excitement comparable to what the charismatic Roosevelt stirred.

Salvation seemed at hand on the Supreme Court. Justice Charles Evans Hughes, appointed to the Court by William Howard Taft in 1910, seemed the ideal solution. Formerly a reformist governor of New York (1907-1910), Hughes had no baggage from 1912, when Taft and Roosevelt fractured the party. He was a man with no personal blemishes who could lead the Republicans back to the White House against the unpopular Wilson. Republicans of the era hated Wilson with a venom reminiscent of how modern GOP members hate President Barack Obama.

“Charles Evans Hughes, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. 9 September 1931.” Public Domain via the Library of Congress.

“Charles Evans Hughes, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. 9 September 1931.” Public Domain via the Library of Congress.How to convince Hughes to leave the Court? He disclaimed all interest in the presidency and ordered his name removed from primary ballots in the spring of 1916. However, unauthorized advocates kept his name before the party. Meanwhile, Roosevelt’s candidacy struck few sparks; his bellicose positions toward World War I attracted some but alienated many, especially in the Middle West, on which the Republicans counted for victory. When the Republican National Convention met in June 1916, the Hughes candidacy was poised for success. It came on the third ballot. Hughes was nominated and he promptly resigned from the bench. Republicans had their savior and they anticipated the ouster of Wilson and a prompt return to power. A reporter with the New York Times visited Hughes’ headquarters a week after his selection and observed, “The casual visitor would think it was all over except the inauguration.”

Hughes was a brilliant jurist, which he later proved as Chief Justice. Alas for the Republicans, he proved an inept candidate. Certain he would win the presidency, he gave dry discourses that stressed familiar GOP themes about the protective tariff and prosperity. On issues of war and peace, he indicted Wilson’s performance but said little about what he would do instead. Democrats called him Charles “E-vasion” Hughes. Audiences arrived at events enthusiastic, but left deflated and disappointed. A reporter concluded that “Hughes is dropping icicles all over the west and will return to New York clean shaven.”

Though the election was close, Democrats boasted that Wilson had “kept us out of war” and those sentiments won the president a second term. Wilson carried the crucial state of California and won 277 electoral votes to Hughes’ 254. Republican Party members disavowed “smart” candidates like Roosevelt, Taft, and Hughes, which won Warren G. Harding favor in 1920. Hughes returned to private life, but years as Secretary of State and Chief Justice of the United States lay ahead of him. No viable candidate has emerged from the Supreme Court since Hughes (unless we consider the feckless antics of William O. Douglas). Given the cavalry-charge nature of the current Republican presidential race—and the prospect of a campaign against Trump—it would not be surprising if Justice Alito, a smart man, considers Hughes as precedent and ignores the aggressive punditry of Bill Kristol for the lifetime security of a seat on the Supreme Court.

Image Credit: “Charles Evans Hughes campaigns in Winona, Minnesota on the Milwaukee Road’s Olympian”. Public Domain via Wikipedia Commons.

The post Could a Supreme Court justice be president? appeared first on OUPblog.

Is phantom limb pain all in one’s head?

Phantom limb pain is thought to result from changes in brain organisation. Recent evidence challenges this view, leaving this mysterious phenomenon unsolved.

Picture yourself waking up in the hospital. Your body is hurting, but you can’t remember what happened. The doctor tells you that you had a severe accident causing you to lose your left arm. You think: “I definitely don’t feel well, but surely the doctor must be mistaken; I can clearly feel my hand and in fact it is hurting.” You turn your gaze at the blanket covering your hand. You want to lift your hand to show it to the doctors, but when you do so nothing happens. On a second look you realise the doctor was correct; the hand you can feel and move is no longer there…

Even decades following amputation, people report a continuous sensation of the limb that is no longer there. The ‘ghost’ of the hand can be perceived as vividly as you might feel your own hand. For 4 out of 5 amputees, phantom sensation of the missing hand can be perceived as quite unpleasant and even excruciatingly painful. People often describe the feeling as if the phantom limb is being crushed or burnt, or as if electrical currents are shooting through it. Some people experience the same pain they felt during the accident leading to the amputation, or disease leading to the limb loss, over and over again. Phantom pain is a chronic condition, and as such can be hugely debilitating. Beyond the impact of a chronic pain condition on quality of life, phantom limb pain will also make it more difficult for amputees to wear and use a prosthetic limb.

Phantom limb pain is notorious for being difficult to treat with conventional medicine. Doctors are having trouble figuring out how to treat pain in a body part that no longer exists. It is therefore important to provide understanding of the neural causes underlying phantom limb pain. Unfortunately, after decades of research, the origin of this syndrome is still unclear.

Originally, phantom limb pain was considered to be a consequence of the injury caused to the nerves transmitting information from the hand into the spinal cord. Since these nerves normally provide information of touch and pain originating from the hand, false input transmitted via these nerves could explain phantom sensations. But for the past two decades, this account has been largely marginalised, and the focus has shifted to the brain. Phantom pain is currently thought to be driven by brain changes in body representation, triggered by loss of input from the missing hand. Neuroscientists currently think that the region in the brain originally in charge of the amputated limb is invaded by neighbouring brain representations. The primary suspect is input relating to the lips, that following the loss of hand input will be re-routed into the missing hand area. Such mismatch between body representations is thought to cause the experience of pain coming from the phantom hand.

This theory of maladaptive brain plasticity has been extremely influential, not only in the neuroscience community, but also for clinicians. This theory provides clear predictions on how best to treat phantom pain: If pain is caused by maladaptive brain reorganisation, then to alleviate phantom pain we need to reverse it. One popular approach to attempt this is by “reinstating” the representation of the missing hand back into its original territory, using illusory visual information about the missing hand (the mirror box therapy).

Although multiple studies over the years provided evidence in support of the theory of maladaptive brain plasticity, some criticisms were also raised. The main assumption underlying the maladaptive plasticity theory, that input loss from the hand triggers a maladaptive domino effect of changed body representation in the brain, has been recently challenged. For example, our study, recently published in Brain, shows that the lip representation doesn’t invade the brain territory of the missing limb. Moreover, the relatively simple explanation of phantom limb pain being driven by false input from the injured arm nerve has gained new support. Finally, treatments designed to alleviate phantom limb pain based on the theory of maladaptive brain plasticity don’t seem to work consistently.

Instead, recent research shows that the brain territory of the missing hand might be utilised in order to support compensatory behaviour that amputees adopt in order to cope with their disability. According to this line of research, brain plasticity following amputation is adaptive, rather than harmful. The fact that brain resources can be reassigned in order to support new requirements provides new promise to neurorehabilitation – taking advantage of the nerves system abilities to improve rehabilitation.

Featured image: “Brain nebula” by Ivan CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Is phantom limb pain all in one’s head? appeared first on OUPblog.

Yorkshire: the birthplace of film?

Any assertions of ‘firsts’ in cinema are open invitations to rebuttal, but the BBC has recently broken news of a claim that the West Yorkshire city of Leeds was in fact film’s birthplace. Louis Le Prince, a French engineer who moved to Leeds in 1866, became one of a number of late 19th-century innovators entering the race to conceive, launch, and patent moving image cameras and projectors.

There is plenty to be said about Yorkshire’s contribution to cinema; and film historians have long been aware of the groundbreaking contributions of the moving-image inventors working in the county’s great cities around the turn of the twentieth century.

Between us we can claim a number of connections—by birth, residence, and education—with Yorkshire, and when writing the Oxford Dictionary of Film Studies, we thought it would be amusing to include a secret entry on film in ‘God’s own county’ to sit cheekily (if mutely) alongside our entries on national cinemas. There are no pointers to “Yorkshire, film in” from other entries in the dictionary. Readers have to come across it serendipitously. What might they make of our offhand joke? So far we’ve had no feedback.

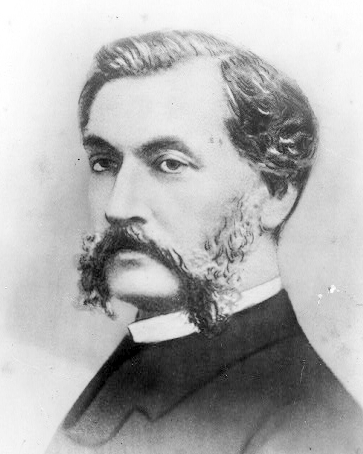

Our entry is circumspect in its reference to the pioneering role of Louis Le Prince. Much more widely acknowledged in this regard, for example, are the Lumière brothers (mentioned in at least ten topics, from “Action film” to “USA, film in the“) and Thomas Edison (referred to in six or more, from “Biopic“to “Trick film“).

As National Media Museum associate curator Toni Booth cautioned in an interview with the BBC: “I think it comes down to definition. The definition of film and the definition of cinema…. As a piece of moving image recording live action–yes I would say [Le Prince] was the first one to do that” (Le Prince’s camera and footage are kept at the National Media Museum in Bradford).

In The First Film, a documentary released on 3rd July this year, filmmaker David Wilkinson sets out the case for Leeds as the birthplace of film and for Le Prince as the father of the new medium, citing not only the Leeds Bridge footage but also a shot of Le Prince’s son playing the accordion and a short actuality filmed on ‘14 October 1888, when a family gathered in the garden in the Leeds suburb of Roundhay. Among the group was Louis Le Prince, who had with him a curious mahogany box. He asked the others in attendance–his son, parents-in-law and a friend–to stand in front of the box and walk in a circle.’

See below for an abridged version of the “Yorkshire, film in” entry:

French cinema pioneer Louis Le Prince (1842-1890) from the New York Public Library’s digital library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

French cinema pioneer Louis Le Prince (1842-1890) from the New York Public Library’s digital library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Yorkshire is one of several UK regional film production centres that can claim a pioneering role in early cinema. In 1888, Louis Le Prince shot Traffic on Leeds Bridge, showing ‘animated pictures’ of horses, people, and trams crossing a bridge in the West Yorkshire city. At the beginning of the 20th century, Frank Mottershaw of the Sheffield Photographic Company made the first of many short ‘story films’, A Daring Daylight Burglary (1903) a 4-minute prototypical chase film featuring 10 shots, some parallel editing, and a train. Mottershaws also made comedy films, crime films (such as The Life of Charles Peace (1905)), and at least one western (A Cowboy Romance, 1908).

At around the same time, the Captain Kettle Film Company made a number of films in and around Bradford, including some westerns; while also in Bradford the Pyramid Film Company made newsreels and a five-reeler, My Yorkshire Lass (1916). Like many regional film production companies, these firms did quite well for most of the 1910s, benefiting from their links with local audiences and exhibitors. However, by 1918 virtually all of them had ceased production in the face of the globalization of the industry and the increasing dominance of US films worldwide.

However, filmmaking in Yorkshire carried on. A 1920 adaptation of Wuthering Heights (A.V. Bramble), filmed 9 miles north of the Brontes’ home in Haworth, was hailed in The Biograph as ‘a real triumph of film art’. Turn of the Tide (Norman Walker, 1935) was shot on Yorkshire’s east coast, and featured the cliffside village of Robin Hood’s Bay.

We of the West Riding (Ken Annakin, 1945), a British Council documentary about the daily lives of workers in the textile industry, was translated into 23 languages and screened in 100 countries.Anderson’s British New Wave feature, This Sporting Life (1962), was shot in and around Wakefield; and Ken Loach’s Kes (1968) was filmed in nearby Barnsley. Rural railway stations in different parts of the county have featured as locations in such films as The Railway Children (Lionel Jeffries, UK, 1970) and Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (Chris Colombus, USA/UK, 2000).

The Leeds International Film Festival, which claims to be England’s largest film festival outside London, has run annually since 1986, and the Sheffield International Documentary Film Festival (DocFest) has been on the festival calendar yearly since 1994.

Featured image credit: Yorkshire country side by gpmg. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Yorkshire: the birthplace of film? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers