Oxford University Press's Blog, page 619

September 10, 2015

Aylan Kurdi: A Dickensian moment

The international response to the photographs of the dead body of three year-old Syrian boy Aylan Kurdi, washed ashore on a Turkish beach on 2 September 2015, has prompted intense debate. That debate has been not only about the proper attitude of Britain and other countries to the refugee crisis, but also about the proper place of strong emotions in political life – a debate between sentimentalists and rationalists. While the sentimentalists think it is right that our feelings about that picture should shape the public debate, the rationalists ask what factual or logical difference a single image can possibly make. This recent episode has been a reminder – for many a troubling one – of the power of raw emotion, and of tears, to transform a political debate.

David Cameron’s initial comments last week, stating his view that taking more refugees into Britain was not the answer to the crisis, made him seem oblivious to the public mood of grief and compassion, and his political opponents, including Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon of the SNP, took the opportunity to condemn his heartless ‘walk on by’ attitude, contrasting it with their own more sympathetic response. Sturgeon reported that she had been ‘reduced to tears’ by the pictures of Aylan Kurdi. ‘That wee boy has touched our hearts,’ she said, ‘but his is not an isolated tragedy’.

The Prime Minister’s office was later at pains to point out that Mr Cameron had made his initial comments before he had seen the photographs of Aylan. Soon Cameron’s tone and policy had both changed. He spoke of being deeply moved, as a father, by seeing the photographs. Those words will have recalled for many of us Cameron’s own heart-breaking experience of losing his son. The 2010 General Election campaign was notable for the fact that both the main party leaders – Gordon Brown and David Cameron – were moved to tears during TV appearances – in both cases when speaking about the loss of their own child. The previous year, speaking in the House of Commons about the death of Ivan Cameron, Gordon Brown said, ‘Every child is precious and irreplaceable, and the death of a child is an unbearable sorrow that no parent should ever have to endure’. It is precisely such a thought that is behind the emotional response to the pictures of Aylan Kurdi.

On the rationalist side of the current debate, however, in a column for the Times headlined ‘Stop crying if you’re serious about migrants’, Matthew Parris has resisted the tide of feeling, arguing that we must not let our hearts rule our heads, and that the proper remedy for the refugee crisis was ‘no more apparent now that we have seen a picture of a lifeless toddler than it was before’. And Parris is not alone in asking why a highly emotional reaction to one photograph of one boy should change anything. The situation has been just as bad for many months, several commentators have noted, with thousands dying in their attempts to cross the Mediterranean. Should an outpouring of sentiment in response to one picture really make Britain, the EU, and the wider world change its policies?

Leaving aside the question of the correct policy towards the refugee crisis, there is certainly no doubt that a single emotional image can have an effect on politics, and I for one think it is quite understandable, and quite right that it should. As Tom Hamilton put it, using a striking analogy in a tweet last week, ‘Asking why people are moved more by one dead boy than by millions of refugees is like asking why people read novels and not spreadsheets.’

We experience, express, and think about our emotions through the cultural resources available to us – through those words, stories, images, and ideas that make up our own particular emotional style. We learn emotional scripts, you might say, through which we feel and perform our own affective lives. These come from many places, but as the contrast between a novel and a spreadsheet so nicely brings out, the arts and humanities – whether photography, fiction, drama, history, or philosophy – offer a richness of resources that can take us beyond the facts and figures. Was anyone ever moved to tears by a statistic?

“Should an outpouring of sentiment in response to one picture really make Britain, the EU, and the wider world change its policies?”

Most would probably agree that imagery and narrative are central to our emotional lives and that these in turn can and should inform our politics. But we might still wonder whether some images and some emotions are more appropriate than others? Is there something especially sentimental or inauthentic about weeping over someone else’s dead child?

Writing in a very different context, and with his own political concerns, the master of the sentimental death in the nineteenth century, of course, was Charles Dickens. Dickens’s death scenes produced pangs of feeling, and bucketsful of tears, famously including those of child characters such as Paul Dombey or Little Nell. Although not as frequently invoked as the death of Little Nell, the demise of Paul Dombey was judged by many at the time to be Dickens’s most successful piece of pathos. A prematurely wise man-child, philosophical, frail and out of place among other children – little Paul slowly fades away, gripped by a vision of a river flowing rapidly out to the sea, carrying him from life to death.

Dickens lived in an era in which infant mortality was at a level that those of us living in the modern West can hardly imagine, and there was a flowing back and forth between real bereavements and idealised literary representations, each giving structure and meaning to the other. Even Oscar Wilde, who famously quipped that one would have to have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing, was a purveyor of highly sentimental stories, including ‘The Selfish Giant’, which ends with the death of a child. We know too, from the recollections of his sons that Wilde used to have tears in his eyes when he read it to them because, he said, ‘really beautiful things always made him cry’.

The images of Aylan Kurdi have given us our own Dickensian moment – a moment of mass emotional response directed towards a contemporary social evil – elicited this time through the medium not of fiction but of photo-journalism. Even Charles Dickens, though, would not, any more than Matthew Parris, have thought that weeping over a child’s death was an end in itself. The point of harnessing human feeling through stories and images is to motivate social action, and that is where tears need to be augmented by other emotions, and by other arguments. Weeping over an image engages our minds and focusses our thoughts on an evil we might otherwise have ignored. Tears are intellectual things. They reveal our beliefs and our priorities and thus have the power to bring about a new political awareness, and to start a new debate.

Even the rationalist Matthew Parris notes, at the start of his recent column, that he wiped away a tear after seeing the pictures of the drowned boy. And the great Enlightenment sceptic David Hume – so hard-headed in many respects – famously argued that in questions of morality and politics, ‘reason is and ought only to be the slave of the passions’. Our heads are inert and directionless without the promptings of our hearts.

Featured image credit: Barbed wire fence, by askii. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Aylan Kurdi: A Dickensian moment appeared first on OUPblog.

September 9, 2015

Divide and conquer, or, the riddle of the word “Devisen”

This is the continuation of last week’s “gleanings.” Once again, I hasten to thank our correspondents for their questions and comments and want only to say something on the matter of protocol. When I receive private letters, I refer to the writers as “our correspondents” because I cannot know whether they want to have their names bandied about in the media. In some cases I ask for their express permission to do so. But while dealing with the comments posted in the blog, I, naturally, have no such compunctions. Therefore, those whose names I withhold should not look upon my reserve as lack of respect.

Engl. device and German Devisen

I received a most interesting letter from a correspondent in Germany. It concerns the German word Devisen “foreign currency; foreign exchange.” In this sense and nearly identical form Devisen occurs in French and several other languages, though not in English. The question was how it acquired its meaning in banking. The letter contained a new explanation and showed the author’s full command of the literature, to say nothing of her mastery of English. I had never thought of the word’s development and owe my familiarity with the main works on it to her. She wondered what I think of her hypothesis. I find it worthy of attention and hope that she will publish an article on the subject in a professional journal, for example, Studia Etymologica Cracovensia. One cannot be sure that any discussion on the Internet will attract the attention of specialists; therefore, a long quote from the letter in what follows won’t go far enough.

The owner of this shield was happy to be left to his own devices.

The owner of this shield was happy to be left to his own devices.Since this blog deals mainly with English, I decided to add a section on the history of Engl. device and devise. My information has been culled from several sources, but especially from Weekley’s An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English, the book to which I always turn when a French connection, real or alleged, has to be elucidated. The origin of device ~ devise from Latin dividere or rather Medieval Latin divisare is obvious. The legal use of the verb devise “to arrange a ‘division’ of one’s property” retains, as usual in law, the word’s etymological meaning. The noun device meant “section, part, something divided.” Prominent among such “parts” were the sections on the escutcheon; hence also “emblem, distinctive mark; motto,” memorable from Longfellow’s “Excelsior” (“a banner with this strange device”). The word was borrowed into Middle English from Old French. Among its meanings over the centuries we also find “plan” (as in left to one’s own devices, an idiom taken over from French wholesale) and “design, figure.” Device “plan” carries the connotation of “trick,” as in artistic device, while devise presupposes a plan akin to plotting. “In this, as in other words, the modern distinction between -s- and -c- is artificial” (Weekley). Some of the recorded senses deviated considerably from “divided section, part.” Yet the leap to “foreign currency” or “promissory note” comes as a surprise.

It remains unclear whether that leap happened in France (so that German borrowed a foreign word) or in Germany, with a subsequent spread of the newfangled term to French and a few other languages. For some time there was an uneasy consensus that because a bank receives many money transfers with addresses like “to London,” “to Amsterdam,” and so on, each of them was a “section” or Devise (German Devisen is the plural of Devise). The problem is why the financial sense arose only in the early nineteenth century, and at the moment no one knows for sure. Scholars pay more attention to the ultimate source of that sense. And now I’ll turn to the letter I received. According to the writer, the modern use of Devisen goes back to

“the emblematic (or heraldic) art form known as impresa in Italy, devise in France, and device in English, and practiced all over Europe in the Renaissance and the Baroque era…. the idea was to combine a more or less gnomic adage or motto with a corresponding allegorical illustration in a witty manner. This intellectual game had five basic rules or conditioni, set forth by Paolo Giovio in his Dialogo dell’imprese militari et amorose (1555) and relayed to the French by Henri Estienne in L’art de faire devises (1645), which in turn was translated into English by Thomas Blount as The Art of Making Devises (1646). Germane to my theory on the origin of the financial term Devisen is the fifth and last of them.”

All three works are available online. Therefore, I’ll skip most of the Italian and the French texts and quote mainly Blount’s English translation, retaining his original spelling:

“And that the Motto (which is the soule of the Devise [Italian: l’anima del corpo, but Blount, as noted, used the French text: l’aime de la devise] be in a strange language, or other than that which is used in the Country [Italian has no or and says simply different from, etc.], to the end, that the intention of it bee [sic] a little removed from common capacities [Italian: perche il sentimento sia alquanto più coperto, French: un peu plus cachée au vulgaire].”

Take the time by the forelock: the rate of exchange changes every minute.

Take the time by the forelock: the rate of exchange changes every minute.Our correspondent’s conclusion runs as follows:

“I… believe that this rule may be at the root of the peculiar meaning ‘promissory notes issued abroad (and therefore not only in a foreign currency but also probably written in a foreign language)’, especially considering the fact that said notes were often embellished with all kinds of heraldic or pseudoheraldic paraphernalia, as many banknotes still are, and in a way indeed resemble the impreses/devises/devices of the 16th and 17th century.”

Why the rules and the terminology of that antiquated art form surfaced in German trading slang two centuries later remains a puzzle. “Possibly masonic lore played a role. After all, the freemasons were just about the only ones who continued the tradition of emblematics at that time and famously managed to perpetuate some of it in the design of the dollar bills.” I should repeat that in my unprofessional view this original reconstruction deserves informed comments from experts (wise men, as such people were called in the Middle Ages).

And now a final flourish. Thomas Blount (1618-1679) was an outstanding lexicographer. His most famous book, Glossographia; or a dictionary interpreting the hard words of whatsoever language, now used in our refined English tongue (1650), is a joy to read because it contains so many words no one knows. He was the first dictionary maker to include citations (in doing so, he anticipated Samuel Johnson and the OED) and quite a few etymologies. In this respect he was also a pioneer. Since his time, every comprehensive English dictionary has felt it its duty to include sections on word origins, and one sometimes wishes Blount had not hit on his revolutionary idea. He had more than a passing interest in devices (in the heraldic sense), as follows from the fact that he featured two woodcuts of them in his Glossographia (note that he spelled the word with an s, thus proving Weekley right) and no other illustrations.

More “gleanings” to follow.

Image credits: (1) Armours at a door/wall of a pub(?) in Tallinn old town. Photo by Samuli Lintula. CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Exchange. (c) Matthew71 via iStock.

The post Divide and conquer, or, the riddle of the word “Devisen” appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know Sherlock Holmes? [quiz]

Sherlock Holmes is one of the most famous detectives of all time. The detective featured in 4 novels and 56 short stories written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and is a regular figure in modern day culture; Holmes has been portrayed on stage, radio, film and television for over a century, most recently by Sir Ian McKellan in the 2015 film, Mr. Holmes.

Test your knowledge with this quiz, based on the novels and short stories, the canon’s history and its place in modern day life.

To brush up on your knowledge of Sherlock Holmes, click here to see our Oxford World’s Classics editions of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s titles.

Quiz image credit: “221B Baker Street”, by becchy. Public domain via Pixabay.

Featured image credit: “Sherlock Holmes”, by symvol. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post How well do you know Sherlock Holmes? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Step 3 to end military suicides: Reduce stigma

This week is National Suicide Prevention Week, and we’ve invited John Bateson to write a series of articles on one group that is particularly vulnerable: military service members. Read Step 1 and Step 2 of 5.

The stigma of mental illness poses a major barrier when it comes to individuals seeking help. As a society, we are much more comfortable admitting physical problems than psychological ones.

Nowhere is this more true than in the military, where troops are trained to be tough and not acknowledge any weaknesses. General George Patton’s infamous slaps of two World War II soldiers who were hospitalized in Italy for psychological reasons is the most obvious example of the military mindset regarding mental health problems, but the same mentality exists throughout much of the military today. This is why encouraging troops to seek help has such little effect. Admission of a mental health problem can result in a commander’s scorn, end opportunities for promotion, and shorten one’s military career.

The military isn’t the only entity responsible for destigmatizing psychological problems, but there are steps the military can take. Here are four:

Individuals who suffer from posttraumatic stress and are able to manage it should be considered strongly for promotions the same as troops who recover from physical wounds. Moreover, when a service member recovering from PTSD is promoted, his or her ability to overcome a serious mental injury should be recognized publicly so that it serves as a model and inspiration for others, just as overcoming a serious physical injury can provide hope and encouragement for people with similar disabilities.

Since the practice is to award Purple Hearts to troops who suffer a serious physical injury in combat, Purple Hearts also should be awarded to those who suffer serious mental health injuries in combat. Injuries are injuries, and none should be minimized.

White House policy regarding letters of condolence must change. Prior to 2011, presidential letters were sent to families of troops killed in battle, but not to active-duty service members who died by suicide. To President Obama’s credit, the policy was amended to include soldiers whose suicides occurred in a war zone. Nearly 80% of suicides by active-duty troops occur stateside, however, and families of these service members should receive letters, too. Their loved ones gave their lives for this country, and acknowledging this can provide a measure of comfort to them. It also will send the message that every suicide—regardless of the circumstances or where it occurred—is a tragedy.

Just as good conduct medals and combat awards are bestowed on troops for a job well done, so should commendations be given when soldiers recognize that their comrades need psychological help and act to see that they get it. It’s part of developing a strong, healthy team.

Reducing the stigma of mental illness will lead more people to admit problems and help reduce the suicide rate of current service members and veterans. It will require institutional changes in policies, procedures, attitudes, and culture in two of our biggest bureaucracies—the departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs—but that is where change needs to happen.

Feature Image: 2009 Army National Guard Honor Guard Competition. US Army photo by Sgt. 1st Class Jon Soucy. The National Guard. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Step 3 to end military suicides: Reduce stigma appeared first on OUPblog.

September 8, 2015

Does war cause xenophobia?

Or does xenophobia cause war? That’s a “chicken and egg” sort of question. The fact is, fear of “the other” had already prevailed in pre-World War I European society—even in more liberal polities such as Britain—later manifesting itself in various ways throughout the conflict. In Britain, nationalism had been heightened by decades of imperial and naval rivalry with Germany. This, coupled with apprehension at surging immigration from Germany and Eastern Europe, stoked fears of the “strangers in our midst.” In the crucible of war, those fears would underpin unprecedented legislation curtailing the rights of aliens who had resided in Britain largely without incident before 1914.

At 11:00 p.m. on 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany following the latter nation’s invasion of neutral Belgium. Shortly after the announcement, King George V emerged with the Queen on the balcony of Buckingham Palace to a cheering crowd. One day later, on 5 August, Parliament enacted the Aliens Restriction Act, targeting the activities and movement of all resident aliens. No alien was permitted either to enter or leave Britain. In addition to being required to register at a local police station, they were barred from traveling more than five miles from their home without a permit, banned from residing in specific areas or owning firearms, and prevented from altering their names to make them more British sounding (as the Royal Family would do in 1917). The Defense of the Realm Act (DORA), followed on 8 August, giving the government the prerogative to control print media through censorship, suspending habeas corpus and imprisoning anyone suspected of interfering with the war effort or assisting the enemy.

Britain was now a “surveillance state.” By the end of August 1914, and upon the recommendation of the General Staff earlier that month, alien residents of military age—those between the ages of seventeen and forty-two—from “enemy” nations such as Germany and Austria were rounded up by the police and held on suspicion of being spies. Those swept up included both long-time residents of Britain as well as relative newcomers on business or travel. Fear of spies and possible internal dissent fomented by “enemy aliens” led one extreme xenophobe to suggest that all German-born men in Britain be “exterminated.” That outrageous call, plus a wave of anti-German riots throughout Britain in October 1914, prompted Britain’s Liberal prime minister, Herbert Henry Asquith (1908-1916), to decide that the internment of “enemy aliens” would protect both Germans from acts of violence and the British public from any potential military danger.

“Herbert Henry Asquith.” Public Domain via the Library of Congress.

“Herbert Henry Asquith.” Public Domain via the Library of Congress.The rapid round-up of “enemy aliens,” however, posed a serious problem for British authorities. Where could they quickly accommodate the thousands of suspected men? (Women, children not of military age, clergy, physicians, and men unfit for military service were exempt.) Temporary shelters, disused factories, and holiday camps were placed at the government’s disposal. Their suitability as internee housing, however, paled in the face of the rapidly increasing numbers of men to be confined. With the sinking of the British ocean liner Lusitania by a German submarine in early May 1915, followed by another round of xenophobic riots called the Lusitania Riots, Prime Minister Asquith chose to commit to a more comprehensive internment policy, one that was intent upon establishing more permanent camps.

There are few remaining historical records detailing the existence of the men who endured life as internees from the beginning of the war until their release in 1919. Fortunately, a twenty five year-old German “alien internee,” Willy Wolff, left a handwritten German diary (later translated into English) that chronicled his arrest in September 1914, temporary confinement in a disused wagon factory, and finally, his internment in Knockaloe Camp on the windswept Isle of Man from September 1915 until 1919.

An inhospitable, desolate place with a circumference of about three miles and enclosed by 695 miles of barbed wire, Knockaloe held over 22,000 men in July 1916. Wolff, dispatched before the war by his German textile firm to a British counterpart near Manchester, described in great detail the strict camp regulations, the disdain with which internees were treated, and the monotony of life behind barbed wire. Life was austere; beds consisted of straw upon wooden planks, the huts had little or no heat, washbasins and toilets were inadequate, food was rationed, meager, and often unappetizing (tinned meats, weak broths with questionable leftovers, stale bread), changes of clothing were infrequent, and stiff penalties were prescribed for infractions, including solitary confinement. Wolff and fellow internees subsisted on news from camp-approved newspapers, occasional packages from home, and infrequent visits from Swiss delegates, finding some relief in social, sports, and hobby clubs.

Wolff was neither a criminal nor subversive. His only crime, if one could call it that, was being a foreign citizen in a country at war with his birthplace. He was a victim of the fact that the First World War provided unprecedented opportunities for states to act upon, or cater to, an already prevalent xenophobia.

Image Credit: “British Empire Union post-World War I poster.” Public Domain via the Library of Congress.

The post Does war cause xenophobia? appeared first on OUPblog.

Step 2 to end military suicides: Beyond combat exposure

This week is National Suicide Prevention Week, and we’ve invited John Bateson to write a series of articles on one group that is particularly vulnerable: military service members. Read Step 1 of 5.

According to a new study of nearly four million men and women who served in the military between 2001 and 2007, deploying to a war zone doesn’t increase a service member’s risk of suicide. The study was conducted by the military’s National Center for Telehealth and Technology, and its findings would seem to serve the military’s purpose. After all, if no causal connection is found between deployment and suicide, recruitment efforts aren’t affected. Researchers hedged a little by noting that they didn’t have access to data on combat exposure, just time spent in a war zone. It’s not much of a caveat, however, considering the asymmetrical aspect of modern warfare and the fact that anyone in a war zone risks being hurt or killed. A more important finding, which received less media attention, was that the results differed for the Army. According to the study, both current and former soldiers experience elevated risks for suicide. Since soldiers constitute the majority of our ground forces, this is notable and contradicts, to some extent, the study’s findings.

That said, a number of experts both inside and outside the military have noted that up to half of all service members and veterans who kill themselves never deploy. They don’t get close to a war zone, much less participate in combat, yet take their lives anyway. Knowing this, the results of the study make sense. Exposure to combat can heighten the risk, but by itself isn’t a determining factor. So what is, and how can it be dealt with effectively?

If military officials truly want to solve the problem, they will be less interested in separating suicide from combat exposure and focus instead on the changes that occur during training.

If military officials truly want to solve the problem, they will be less interested in separating suicide from combat exposure and focus instead on the changes that occur during training. This is when troops learn to be tough, aggressive, and not show any sign of weakness. They learn to suppress emotions, deal with conflict through violence, become intolerant to pain, and be fearless in the face of death. Not coincidentally, these are the same qualities that make an individual more at risk for suicide. Developing ways to reverse this training once someone leaves the service, then implementing them, will go a long way toward ending the problem.

Then there is the fact that troops have easy access to lethal means. They learn how to handle all kinds of weapons, and after they leave the service they often keep firearms nearby for protection and security. Another recent study, this one by Department of Veterans Affairs, found that female military veterans have a suicide rate that is nearly six times higher than female non-veterans. Contributing factors are thought to be higher incidences of sexual assaults in the military and higher rates of PTSD among females. Overlooked was that civilian women who are suicidal tend to overdose while female vets are more likely to use a firearm, which is deadlier. Restricting access to lethal means is difficult in the military, but not impossible. In Israel, the suicide rate for men age 20 to 24—a high-risk group among civilians, and higher in Israel because of mandated military service—was reduced by 40 percent when soldiers no longer were allowed to take their weapons home on weekends. One small institutional change has saved hundreds of lives.

In the past decade, the number of suicides by active-duty troops and veterans has reached epidemic proportions. In response, the military has implemented a variety of strategies—all well-intentioned, but collectively not enough. Military suicides don’t start with combat; they start with basic training. Answers to ending them start there, too.

Feature Image: USA flag by marlidia. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Step 2 to end military suicides: Beyond combat exposure appeared first on OUPblog.

In praise of SoundCloud

When you’re a musician, you’re constantly passing between the private and the public spheres. Practicing by yourself in a soundproof room is a private activity. Playing an audition is a public act. Reading a score silently is private; releasing a CD is public.

Some people are quiet and private by nature and abhor the stage, even though they’re professional musicians. Others are extroverted and gregarious; for them life on the stage is a party, and the torture is to be alone with their thoughts and feelings. In brief, both the timid and the gregarious need to work on their passing from private to public and back again.

For the past couple of years I’ve been posting recordings to SoundCloud, an online platform for sharing sounds. It’s been productive and enjoyable. Among other things, SoundCloud allows me to make the passage from the private to the public sphere in safety, so to speak.

SoundCloud is inherently flexible with a clean, attractive, uncluttered look. Every artist is welcome to use it; every song is welcome; every listener is welcome. You can use it under a pseudonym if you wish. Or you can post your sounds without hiding your pretty face, if you prefer. You can consider it part of your professional profile (therefore turning it into a public arena). Or you can consider it a tool for exploring your creativity (therefore making it a more private experience). You can use it for free, or you can pay a monthly fee to unlock extra features. Uploading and editing tracks is very easy and requires just a click or two.

I’ve uploaded tracks from my professionally recorded CDs, tracks recorded on my iPad Mini, tracks recorded on a handheld device with decent mikes (a Zoom HD3, which only costs a couple hundred dollars), and tracks recorded in an inexpensive neighborhood studio. If you have no equipment and no access to a studio, you can record yourself well enough with a smartphone. I’ve posted unedited tracks, but also tracks that I’ve souped up in some way. (I use a free audio-editing program called Audacity. It’s easy to use — a click here, a click there, and you have shortened a track or an added reverb.) SoundCloud forgives everything.

What I like most about SoundCloud is how much it has inspired my creativity. Some of my tracks are from the mainstream repertory, like the sonata for cello and piano by Claude Debussy. Others are compositions of mine—for solo cello, for cello and whistling, for piano and voice, and many other combinations. A friend of sent me a spoken poem, for which I improvised a piano accompaniment. Some of my tracks are shorter than a minute; we might call them “sonic snapshots.” Others are more elaborate, involving (for instance) cascading harmonics with echoing effects.

On several occasions, the desire to feed my SoundCloud page, as it were, spurred me to musical action. Because I had a sort of professional pride in keeping up a steady stream of fresh postings, I’d get active in the practice room and prepare sketches and songs. What crazy thing can I do with the cello, just so that I share it on SoundCloud? How about tuning the cello in a completely unorthodox way? Sure. I’ll lower the G string to a D, raise the C string to the same D, and have a sort of “D Major cello” with incredible harmonics and resonances. It’s nothing but pure joy.

I’ve long believed that it’s useful for everyone to juggle two or more projects, instead of concentrating on a single one. Turning your attention from one project to another, and then back again, allows you to stay fresh and energized. Musical ideas sometimes need to sit in the backburner for a while and simmer without your paying conscious attention to them.

Although SoundCloud won’t bring you material riches, it allows you to develop your musicianship and professionalism. It allows you to do things you wouldn’t do on stage or in auditions and competitions. It allows you to test the waters when you’re working on something new. It allows you “to be yourself.”

Featured image courtesy of Pedro de Alcantara.

The post In praise of SoundCloud appeared first on OUPblog.

Establishing ICSID: an idea that was “in the air”

As a young ICSID neophyte, I once asked Aron Broches, the World Bank’s General Counsel from 1959 to 1979, how he had come up with the idea for the Centre. “It was in the air,” he explained.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, there were indeed a number of proposals circulating for the creation of an international arbitral mechanism for the settlement of investment disputes, either as part of a broader investment protection scheme or as a stand-alone mechanism. I would like briefly to discuss two of the most important of these initiatives—one supported by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), and the other pursued at the United Nations.

They provide, I think, interesting context for considering ICSID’s beginnings and the prophesies, ventured by some of the participants in the drafting of the ICSID Convention, that investment treaties might call for the settlement of investment disputes by ICSID arbitration.

At the OECD, the initiative was of course its Draft Convention on the Protection of Foreign Property, published in 1962. It combined substantive standards of treatment of investment with provisions on the arbitral settlement of disputes, including investor-State disputes. The OECD Draft was based on a Draft Convention on Investments Abroad, commonly called the Abs-Shawcross Draft Convention, after the leaders of the work to produce it, Hermann Abs of Deutsche Bank, and Hartley Shawcross, a former British Attorney General. Adopted in 1959 by the Association for the Promotion and Protection of Private Foreign Investment, the Abs-Shawcross Draft had been introduced into the OECD’s predecessor organization in 1960 by Germany.

In the Abs-Shawcross Draft, the arbitration procedures were purely ad hoc ones, drawn for the most part from the standard arbitration clauses of the World Bank’s loan and guarantee agreements (and hence of proven acceptability to developing countries). As revised in the OECD Draft, the procedures addressed a number of concerns that have a familiar ring today—frivolous claims, multiple claims arising out of the same facts and raising substantially the same issues, security for costs, and interventions in a proceeding by a non-disputing party to the treaty.

Image: Bank President George Woods (r) signs the ICSID Convention, with Aron Broches (l), General Counsel of the World Bank. Courtesy of World Bank Group Archives – file unit 1891281, box 217582B (www.worldbank.org/archives). Image used with permission.

Image: Bank President George Woods (r) signs the ICSID Convention, with Aron Broches (l), General Counsel of the World Bank. Courtesy of World Bank Group Archives – file unit 1891281, box 217582B (www.worldbank.org/archives). Image used with permission.Following publication of its Draft, the OECD asked the World Bank if it would take over the project. Through its spokesman, Mr. Broches, the Bank declined to do so, believing it could not bridge the gap between industrial and developing countries on the substantive issues involved and still produce a meaningful text. Eventually reissued by the OECD in 1967, the document never progressed beyond the draft stage, although its substantive provisions inspired those of many bilateral investment treaties (BITs).

Work on what became the seminal Abs-Shawcross Draft Convention of 1959 was given a boost when, in a 1958 speech before the UN Commission for Asia and the Far East, the Prime Minister of what was then Malaya suggested that increased flows of private investment to countries in the region, might be fostered by their conclusion of a convention regulating the treatment of such investment. This was followed, at the end of 1958, by a General Assembly resolution, informally called the “Malayan resolution”, asking the UN Secretary-General to study and report on that and other measures for channelling greater flows of investment to developing countries.

A resulting 1960 report of the Secretary-General emphasised that making international arbitral procedures available for the settlement of investor-State disputes would be central to efforts to encourage more investment in developing countries. Given the difficulty of reaching agreement on a broader investment convention, the report suggested that an independent investment arbitration treaty, setting up an arbitration agency, possibly under UN auspices, might be a better alternative, “at least as an intermediary solution.” The report pointed out that an arbitration treaty might in fact provide wider protection than an investment convention; the arbitration treaty might be made to cover all investment disputes while the protection of the investment convention would normally be limited to rules that the parties had agreed to include in the convention. Another possibility mentioned by the report was that the accumulation of decisions of tribunals constituted under the auspices of the arbitration agency might in effect eventually create the “code” of substantive standards of treatment hoped for from an investment convention.

At the UN, however, the idea met with opposition from Soviet bloc as well as Latin American countries. With its less polarized membership, the World Bank was more readily able to embrace such an initiative. Soon after consultations by Mr. Broches at the UN in 1961, he broached the subject for the first time with the Executive Directors of the Bank. He thereby set in motion the process that culminated, four years later, in the opening of the ICSID Convention for signature.

Mr. Broches’s “vision and genius,” to use Professor Christoph Schreuer’s words, also extended specifically to linking ICSID to BITs. The Centre’s governing body is its Administrative Council, consisting of one representative of each State party to the ICSID Convention. Mr. Broches was elected Secretary-General of ICSID at the inaugural meeting of the Administrative Council in early 1967. In his address to the first annual meeting of the Council, held later in 1967, Mr. Broches raised the question of the settlement of disputes under BITs. There were then only about 70 BITs; and they provided for the settlement of disputes only through State-to-State arbitration. “Now that the facilities provided by the [ICSID] Convention were available, it might be advisable,” Mr. Broches suggested in his 1967 address, “to substitute these procedures, at least on an optional basis, for those provided in these treaties.”

The suggestion was reinforced in 1969, when the Secretariat of the Centre issued a set of model clauses that States might use to provide in BITs for their submission to ICSID of disputes with investors of their treaty partners. The same year saw the conclusion of the first BITs with such clauses. Within a decade, ICSID clauses had become a standard feature of the growing network of BITs.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

These remarks were originally given at the 18th Annual IBA International Arbitration Day, ICSID’s 50th Anniversary: A retrospective and a forecast of the future of investment arbitration, February 2015. © International Bar Association.

Featured image credit: “The World Bank Group headquarters buildings in Washington, D.C.” by AgnosticPreachersKid. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Establishing ICSID: an idea that was “in the air” appeared first on OUPblog.

September 7, 2015

John Oliver, Televangelists, and the Internal Revenue Service

John Oliver’s sardonic spoof of televangelists raises important issues that deserve more than comic treatment. Oliver’s satire was aimed both at the televangelists themselves and at the IRS. In Oliver’s narrative, the IRS acquiesces to televangelists’ abuse by granting their churches tax-exempt status and failing to audit these churches. The law defines the term “church” vaguely. The IRS’s allegedly lackadaisical approach, Oliver tells us, permits televangelical preachers to live luxurious lives replete with private planes and tax-free cash, financed by naive and exploited believers.

An initial problem with this critique is that the IRS does not write the Internal Revenue Code. Congress writes the Code, and the American people elect Congress. As Peter Reilly of Forbes observes, in section 7611 of the Internal Revenue Code, Congress constrained the IRS’s ability to audit churches. Oliver criticizes the resulting low audit rate of churches without explaining who is responsible for this low audit rate—namely, Congress.

There are competing interpretations of section 7611. This provision of the Internal Revenue Code might be viewed as a plausible effort to minimize church-state entanglement by constraining the IRS’s ability to audit churches. Alternatively, Code section 7611 might be understood as Congress bending to political pressures from churches. Both narratives might contain part of the truth.

In any event, the low audit rate of churches, which Oliver blames on the IRS, is the responsibility of Congress. For better or worse, Congress has made it more difficult for the IRS to audit churches than to audit other persons and institutions in Code section 7611.

Another bête noire of Oliver’s critique is the private planes used by some televangelists. However, a minister’s personal use of a church-owned plane is taxable income to him, just as a corporate executive’s personal use of a company plane is taxable income to him.

More generally, churches pay more taxes than many people believe (including, apparently, John Oliver). For example, ministers pay self-employment taxes while churches pay FICA taxes on the salaries of their nonclerical employees. In many states, churches are subject to the sales tax, either as buyers or sellers and sometimes in both capacities.

Churches do not pay federal and state income taxes on their basic operations. However, neither do other nonprofit organizations such as colleges, universities, hospitals, and private foundations. It would be interesting for Oliver to compare the lifestyles of the individuals who lead these tax-exempt institutions with the life-styles of the church leaders of whom Oliver is so critical.

Interestingly, one phenomenon which troubles Oliver—small donors sending cash contributions to televangelical churches—is not problematic from a tax perspective. Oliver obviously disapproves of these donors and their responsiveness to televangelists’ appeals. However, small donors’ contributions are typically not tax deductible. Contributions to churches and other charitable institutions are deductible by the taxpayer only if the taxpayer itemizes personal deductions on his Form 1040. This occurs only among more affluent donors whose deductible outlays exceed their standard deduction for income tax purposes.

For 2015, a single taxpayer’s standard deduction is $6,300, while the standard deduction for a married couple filing jointly is $12,600. Thus, the modest donations cited by Oliver, while large relative to the donors’ low incomes, are generally not tax deductible because donors with limited incomes typically do not contribute enough to itemize their deductions. The real beneficiaries of the Internal Revenue Code’s charitable deduction are upper-middle class and wealthy taxpayers. These affluent taxpayers typically do not contribute to churches, but to such secular entities as universities and museums.

Finally, the legal issue of defining a church involves serious trade-offs that Oliver does not explore. Again, Congress, not the IRS, writes the tax law. Congress could, through the Internal Revenue Code, define “church” more restrictively to crack down on the kind of arrangements Oliver satirizes. However, a narrower definition of a “church” could also be used against nonconformist and unconventional religions—which, at times in our country’s history, would have included abolitionist churches, the Catholic Church, the Church of Latter Day Saints, and other now mainstream organizations. For that reason, as a society, we generally seek to minimize church-state entanglement, even though the resulting zone of religious autonomy can be exploited by the kind of ministers Oliver skewers.

Since at least Sinclair Lewis’s Elmer Gantry, evangelical preachers have been subject to the kind of criticism Oliver advances. The IRS, particularly in its handling of exempt organizations, is in many ways a troubled and poorly-managed agency. If we categorize Oliver’s skit as mere entertainment, it was, well, entertaining. However, Oliver evidently seeks to place himself in another tradition of American life, the tradition of Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce, Will Rogers, and Mort Sahl. These humorists participated in important political discussions through their comedic commentary.

By the demanding standards of this tradition, Oliver’s satire of televangelists falls short.

Image Credit: “John Oliver at UB” by Chad Cooper. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post John Oliver, Televangelists, and the Internal Revenue Service appeared first on OUPblog.

The origins of Labor Day: Marches and civil unrest in 1880s Chicago

When I ask college students what they know about the origins of Labor Day, the answer is usually straightforward: not much. But if the labor movement’s story is not on the tip of their tongues, it says less about them than it does about our era. In recent decades, unions – weakened by plummeting enrollments and beset by powerful detractors – have struggled to steer public debate and even to determine the meaning of their own signal holiday. Little wonder that, for countless Americans, Labor Day is more about end-of-summer barbecues and back-to-school sales than it is about capitalism and class politics.

This hasn’t always been the case. Consider the lively debates that animated Chicago’s inaugural Labor Day celebration in 1885:

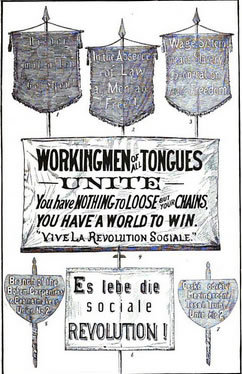

On Sunday, September 6th, organized labor’s most radical wing led a preemptive march through the city’s downtown and near north side. More than 5,000 persons participated in the anarchist and socialist-led demonstration, which included representatives from at least eleven different unions carrying banners with messages such as: “The greatest crime today is poverty!”; “Capital represents stolen labor”; and “Every government is a conspiracy of the rich against the people.” This large subset of the city’s rank-and-file had decided to boycott Monday’s festivities on the grounds that the red flag – radicalism’s most potent symbol – had been expressly banned, but this particular dispute was in fact symptomatic of much larger differences within labor’s camp. The anarchist Sam Fielden emphasized these in his remarks, declaring, “There is going to be a parade tomorrow. Those fellows want to reconcile labor and capital. They want to reconcile you to your starving shanties.”

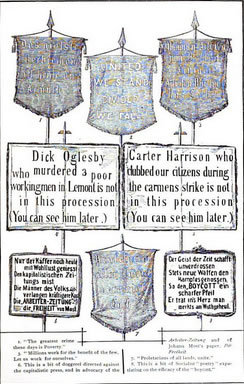

On Monday, September 7th, an “immense crowd” of onlookers gathered as thousands marched in the more mainstream Trade and Labor Assembly’s parade. They, too, carried banners, but these struck more moderate tones: “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you”; “We do not ask for charity, but simple justice”; and “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for recreation.” The procession wound its way to Ogden’s Grove, where a grand picnic commenced and a throng of 10,000 heard speeches from a variety of dignitaries, including Mayor Carter Harrison – this, despite the fact that some in the Assembly had protested Harrison’s inclusion “on the ground that he was a political hack that had no sympathy for the laboring man.” The crowd that day turned out to be mostly friendly and applauded vigorously when the mayor proclaimed, “Labor and capital may seem antagonistic, but they are in fact the best of friends. Make it friendly by organizing and teaching capital that its interest is to pull with you.”

The arguments persisted long after the parade-goers returned home. The Chicago Daily Tribune decried the radical demonstration in an article entitled “Cutthroats of Society,” which began, “With the smell of gin and beer, with blood-red flags and redder noses, and with banners inscribed with revolutionary mottoes, the anarchists inaugurated their grand parade and picnic.” The Trade and Labor Assembly’s march received more favorable reviews from middle-class voices and was even outright celebrated by some. But anyone paying attention knew that respectable opinion could turn as rapidly on the trade unions as it did on the anarchists. Just two months before Labor Day, the police had violently subdued a streetcar workers’ strike. In the process they won the admiration of many middle-class Chicagoans, including one minister who used his pulpit to urge the authorities to maintain order, even if it required them “to mow down the crowds with artillery.”

These snapshots from Chicago’s first Labor Day suggest a crucial difference between the Gilded Age of the late-nineteenth century and the one we find ourselves in today. Even as contemporary disparities between rich and poor approach historic proportions, Americans today are not nearly as engaged in the kinds of freewheeling debates over the morality of capitalism that consumed many of those who lived through industrialization’s peak decades. In their world, devastating recessions elicited fundamental questions about the shape of the nation’s economic life. In their world, concerns about the experiences of the workers and the fate of the working classes saturated public conversation. It is a world removed from our own and yet one that – on Labor Day, no less – is well worth revisiting.

Featured image: “The Haymarket Riot” by Harper’s Weekly. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Post images from Anarchy and Anarchists: A History of the Red Terror and the Social Revolution in America and Europe. Communism, Socialism, and Nihilism in Doctrine and in Deed. The Chicago Haymarket Conspiracy, and the Detection and Trial of the Conspirators by Michael J. Schaack (1889). Public domain.

The post The origins of Labor Day: Marches and civil unrest in 1880s Chicago appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers