Oxford University Press's Blog, page 621

September 5, 2015

Art across the early Abrahamic religions

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are considered kindred religions–holding ancestral heritages and monotheistic belief in common–but there are definitive distinctions between these ‘Abrahamic’ peoples. The early exchanges of Jews, Christians, and Muslims were dominated by debates over the meanings of certain stories sacred to all three groups. In addition to the verbal tales, art played a significant role in the interpretations, often competitive, of the sacred stories they had in common. In mosaics, in stone carvings, and in paintings, we consistently encounter what artists of the three communities wished to emphasize as especially important.

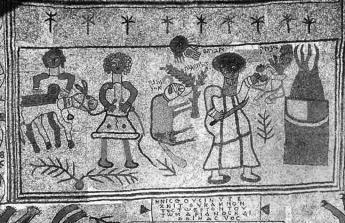

"Aqedah ('binding') scene from the Beth Alpha synagogue".

This mosaic floor decoration in a 6th century CE synagogue captures the moment in which Abraham, about to place his son Isaac onto the fiery altar as commanded, is stopped by God (who speaks, and shows his hand, from above). He then provides a ram as a substitute sacrifice. Abraham’s faithfulness in the “binding of Isaac,” and God’s reward of his obedience, is one Judaism’s foundational narratives.

Figure 4.7 “Aqedah (‘binding’) scene from the Beth Alpha synagogue.” 6th century CE. Photo courtesy of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

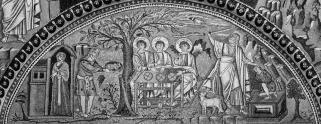

"Abraham extends hospitality to messengers, prepares to sacrifice Isaac".

Standing above the space where 6th century Christians celebrate their eucharistic meal in one of Ravenna’s grand churches, a celebration of Christ’s death and resurrection, this mosaic combines themes. Abraham and Sarah welcome and entertain the angels who foretell the birth of Isaac to them in their old age; and here, in this setting, the near sacrifice of Isaac signals the future sacrifice of Christ, with its powers for salvation.

Figure 4.4 “Abraham extends hospitality to messengers, prepares to sacrifice Isaac.” Mid-6th century CE. Mosaic in San Vitale, Ravenna. © Art History Images.

"The hospitality of Abraham".

In the great Roman church dedicated to Mary, another fine mosaic shows the angels’ visit to Abraham and Sarah in two scenes. The cross atop the door behind Sarah is only one indicator of the Christianization of the story in Genesis 18, for high above, in the church’s triumphal arch, another announcement of a child to be born is made to Mary.

Figure 5.3 “The hospitality of Abraham.” A mid-5th century CE mosaic. Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome © Art History Images.

"The angel Jabril visits Ibrahim’s family"

An image placed in a Muslim book of “stories of the prophets,” this fine Persian painting depicts Abraham’s gathering of his two women and his son Ishmael at “God’s house” in Mecca, where Jabril (Gabriel) announces the miracle of the coming pregnancy of Sarah, and her birth-giving to Isaac.

Figure 6.1 “The angel Jabril visits Ibrahim’s family.” From a 1577 copy of Nisaburi’s Qisas al-Anbiya. © The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Spencer Collection, Persian Ms. 1, folio 33b.

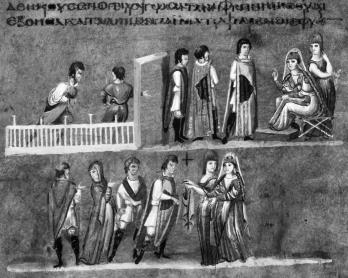

"Joseph runs from Potiphar’s wife, and other scenes"

The concluding chapters of the Book of Genesis recount the story of Jacob’s son, Joseph, whose brothers were responsible for his enslavement in Egypt. The wife of his owner, Potiphar, attempted to seduce the handsome young man—an episode that became a favorite for Jewish, Christian and Muslim interpreters.

Two paintings from a 6th century Christian book show Joseph’s escape from the bed of Potiphar’s wife and a scene in which she prepares to convince her husband that Joseph, whose garment she holds, accosted her. We are left to wonder what the artist intended in placing a cross above the cloak.

Figure 7.2 “Joseph runs from Potiphar’s wife, and other scenes.” The Vienna Genesis. 6th century C.E. Painting: 16 x 26 cm. © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung, Vienna. Nationalbibliothek, cod. theol. gr. 31. Page 31.

"Potiphar’s wife displays Joseph’s garment"

The concluding chapters of the Book of Genesis recount the story of Jacob’s son, Joseph, whose brothers were responsible for his enslavement in Egypt. The wife of his owner, Potiphar, attempted to seduce the handsome young man—an episode that became a favorite for Jewish, Christian and Muslim interpreters.

Two paintings from a 6th century Christian book show Joseph’s escape from the bed of Potiphar’s wife and a scene in which she prepares to convince her husband that Joseph, whose garment she holds, accosted her. We are left to wonder what the artist intended in placing a cross above the cloak.

Figure 7.3 “Potiphar’s wife displays Joseph’s garment.” The Vienna Genesis. 6th century C.E. Painting: 16 x 26 cm. © Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung, Vienna. Nationalbibliothek, cod. theol. gr. 31. Pages 31 and 32.

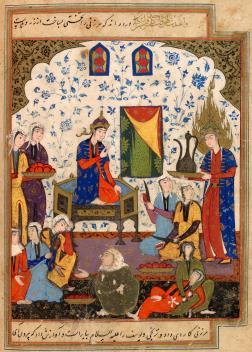

"Yusuf appearing at Zulaykha’s gathering of Egyptian ladies"

Zulaykha (as the temptress of Yusuf (Joseph) is known in Muslim tradition) holds a tea for women who have gossiped about her dalliance with her slave boy. Stunned by his beauty when he appears, the guests are so overwhelmed that they slice their hands with the small knives supplied for cutting fruit.

Figure 9.1 “Yusuf appearing at Zulaykha’s gathering of Egyptian ladies.” From a Nisaburi Qisas ms. Ca. 1580. © The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Spencer Collection, Persian Ms. 46, fol. 48b.

"The opening column of Jonah"

A medieval Jewish Bible marks the beginning of the Book of Jonah (the enlarged first word can be translated “It happened that…”), by an illustration of the resistant prophet emerging from “the great fish” God sent to swallow him. The cap he wears suggests the head-covering worn for prayers, and the note in the margin indicates that this book is to be read at Yom Kippur.

Figure 10.1 “The opening column of Jonah.” Xanten Bible, Germany. 1294. © The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Spencer Collection.

"Gem incised with cycle of Jonah scenes"

This polished piece of carnelian features incisions of the several events of Jonah’s captivity in, and release from, the sea monster God sent to him. It is difficult to determine whether this is a Jewish or Christian product.

Figure 10.3 “Gem incised with cycle of Jonah scenes.” Ca. 300 CE. Width 1.9 cm. Photo courtesy of Christian Schmid and Dr. Jeffrey Spier.

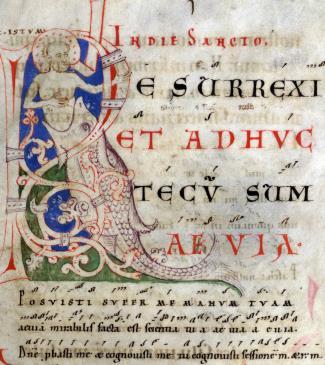

"Jonah and the whale, from a page of the Melk Missal"

A Christian hymn text for Easter shows Jonah, not capped, but haloed, as a Jesus-figure, likening the prophet’s three days in the fish to Christ’s three days “in the heart of the earth” (Gospel of Matthew 12:40).

Figure 11.l “Jonah and the whale, from a page of the Melk Missal.” Late 12th century. Photo: 17 x 26.5 cm. © The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland. The Walters Museum Ms. W 33, folio 9r.

"Sarcophagus depicting Selene and Endymion"

Artistic representations of Jonah lounging beneath the leaves of a gourd plant (see the image above, and Jonah 4:6) are thought to have been influenced by the popular Greek and Roman depictions of the handsome young man, Endymion. The goddess Selene famously kept him from dying, so that she might descend to him for amorous visits.

Figure 11.4 “Sarcophagus depicting Selene and Endymion.” Detail. Ca. 210 CE. Photo: courtesy of the Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California. Getty Museum 76.AA8.

"Yunus emerging from the fish"

One of many intriguing Muslim paintings of Yunus (Jonah) exiting the fish, this one presents the prophet in the guise of an ecstatic mystic, his arms raised in the manner of a Sufi dervish.

Figure 12.4 “Yunus emerging from the fish.” From a copy of Juwayri’s Qisas al-anbiya, ca. 1574-1575. Painting: 23.4 x 13 cm. © Columbia University Library, New York. Smith collection, MS X 892.8 Q1/Q.

All images reprinted in Shared Stories, Rival Tellings: Early Encounters of Jews, Christians, and Muslims by Robert Gregg.

Featured image credit: “Sarcophagus depicting Selene and Endymion.” Detail. Ca. 210 CE. Image used courtesy of the Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California. Getty Museum 76.AA8.

The post Art across the early Abrahamic religions appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Hannah Arendt

The OUP Philosophy team have selected Hannah Arendt (4 October 1906-4 December 1975) as their September Philosopher of the Month. Born into a Jewish German family, Arendt was widely known for her contributions to the field of political theory, writing on the nature of totalitarian states, as well as the resulting byproducts of violence and revolution. Some of her most famous works include; The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), Eichmann in Jerusalem (1965), On Revolution (1963), and On Violence (1970).

Arendt grew up in Königsberg, a city in the Kingdom of Prussia (modern day Kaliningrad, Russia), also the birthplace of philosopher Immanuel Kant. She obtained her doctorate in 1929 from the University of Heidelberg, studying under Karl Jaspers and Edmund Husserl. Due to the rise of Adolf Hitler and the German economy in the wake of World War I, Arendt fled Germany a few years after completing her degree and moved to Paris, France. There she devoted much of her life to working with Zionist organizations, serving as an agent of change and working to fight religious oppression.

In 1940 her work came to a halt – Arendt was seized by the German occupation and prosecuted as an enemy alien. As a result, she was placed in a French Internment Camp. Upon her release, Arendt left Nazi-occupied France and immigrated to the United States, where she became a naturalized citizen. Here she continued her work both as an activist and a scholar. She paralleled the regimes of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin in The Origins of Totalitarianism, coining the controversial term ‘banality of evil’ in Eichmann in Jerusalem, and continued her political research in On Revolution and On Violence. In her later years, Arendt held professorial positions at the University of Chicago, Berkley, Columbia, and Princeton.

Arendt died of a heart attack in New York City, aged 69. She was buried alongside her husband, Heinrich Blüchner, at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York.

You can learn more about the life and works of Hannah Arendt by looking out for #PhilosopherOTM across social media and by following @OUPPhilosophy on Twitter. You can also discover other philosophers via the Philosopher of the Month resource hub.

Featured image credit: “Ammersee Sunset Landscape”, by AndyTriggerRaw. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Philosopher of the month: Hannah Arendt appeared first on OUPblog.

September 4, 2015

Back to the “stove front”: an oral history project about Cuban housewives

We recently asked you to tell us to send us your reflections, stories, and the difficulties you’ve faced while doing oral history. This week, we bring you another post in this series, focusing on an oral history project from Carmen Doncel and Henry Eric Hernández. We encourage you to to chime into the discussion, comment below or on our Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, and G+ pages. If you’d like to submit your own work, check out the guidelines. Enjoy! – Andrew Shaffer

Every utopia contains dystopian spaces, places that must be destroyed and eliminated, for they represent values totally contrary to the ideals on which the new society must be built. In the particular case of the emancipatory project that the Cuban Revolution conceived for women, the kitchen—identified as the symbol of their exploitation and oppression in capitalist societies—became one of these spaces whose walls had to be demolished and, with them, the figure of the housewife. To that end, the Marxist theorists Larguía and Dumoulin proposed in 1971 from the pages of the Cuban cultural journal, Casa de las Américas, that housewives “must commit suicide as a class, through the struggle and through the merging with the proletariat” because, like other small-scale producers, they were a marginal and secondary class that lacked “the authority to lead a country” and “oppose the imperialism.” Leave the kitchen to get into the factory or the office, take the apron off to put the overalls on, drop the ladle to take the cane knife, or replace the mop with the rifle—these became some of the watchwords of this movement through which the housewife would be substituted by a model of female identity more in line with the new socialist state: the working and militant woman.

However, and despite the significant gains achieved during this process, the incitement to leave the domestic space was not always accompanied by a real attempt to challenge the cultural and ideological foundations underpinning women’s domesticity. It was quite the opposite: far from being questioned, the ideals, virtues, expectations, and values associated with traditional female roles were reinforced and transferred from the old to the new model. So, dressed in their new olive green fatigues, Cuban women were still expected to display the same spirit of sacrifice, total commitment, and absolute dedication to the party, the motherland, and the revolutionary cause that had been previously required of them within the household as devote mothers, and faithful and obedient wives. And then, when they were the first who had to give up their jobs due to the crisis of the 1990s that came with the collapse of the socialist block, they were also asked to resign themselves and go back to “the stove front,” to that kitchen where sometimes there were no children left waiting for them, either because they had abandoned the country, tired of these same causes, or because they had died fighting for them in some internationalist mission.

According to the anthropologist Isabel Holgado, during the so-called “Special Period in Time of Peace,” the State delegated its social functions to women, while at the same time certain social services were carried out again at home. Those housewives who had been forced to self-immolation had to rise from their ashes and make a great effort to solve the problems of daily life. In view of their importance in cushioning the impact of the crisis—and so avoiding the collapse of the system—these “domestic strategists” were revalued and even recognized as national heroines by the same government, which had despised them before for being economically unproductive and politically inactive.

Considering the above, the online project “It happened in the kitchen of my house” is conceived as an interdisciplinary and multimedia project. Combining the theoretical and methodological assumptions of oral history with the main concepts of art intervention, it aims to explore this difficult (and sometimes traumatic) process of “returning home” as it was lived by some Cuban woman from diverse parts of the island. Moreover, it strives to draw attention to the kitchen as a political forum for grievance and protest—that is, as a rhetorical space from and about which these women communicated their dissatisfaction, frustration, discontent, resentment, and disagreement with the ruling power. The first stage of the fieldwork was carried out between 2004 and 2008 in different places of Pinar del Río, Havana, and Camagüey provinces, where we interviewed several women of different ages and life paths, some of whom we lived with and accompanied in their quotidian chores. For this, we were granted financial support from the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation-Spanish Embassy in Havana in 2004, from which we would also receive the Visual Art Prize in 2006.

The material gathered during our fieldwork includes the audio and visual recording of the interviews, personal documents of the interviewees, and photographic documentation of their kitchens, all of which are now accessible on the website we created for that purpose earlier this year. Designed as chest of drawers, the website of “It happened in the kitchen of my house” offers people access to free audio files of the interviews, a series of short documentary films based on the audiovisual material collected, the fieldwork notes, and a set of postcards. Created as artistic objects using the aforementioned pictures of the kitchens, some fragments of the interview transcriptions, and personal documents, these postcards are part of an art book made from silkscreen printing, due to be published in 2016. Conceived as a work in progress and as a space for dialogue, the online project “It happened in the kitchen of my house” also includes a section for the articles that are currently being prepared by the authors of the project, as well as by others who are interested in analyzing the previously stated issues associated with the figure of the housewife within revolutionary Cuba.

This article originally appeared in the newsletter of the International Oral History Association.

Image Credit: “Documentation of a kitchen” by Hernández-Doncel. Used with permission.

The post Back to the “stove front”: an oral history project about Cuban housewives appeared first on OUPblog.

Hypertension: more fatal than essential

Hypertension (or high blood pressure) is a common condition worldwide, and is known to be one of the most important risk factors for strokes and heart attacks. It is considered to affect almost a third of all adults over the age of 18. Its prevalence is thought to be increasing to almost epidemic proportions, especially in developing countries. This could be due to many reasons, including better access to healthcare whereby diagnosis is made (and therefore reporting rate rather than true incidence rate is increased), and the increasing “westernization” of lifestyles.

It is interesting to note that hypertension was not always considered a “bad” condition. Indeed, it was considered by the physicians of the early 20th century to be an important compensatory mechanism for the body to cope with illness, hence the term “Essential hypertension”, which unfortunately is still used today, much to the confusion of medical students. It was only in the late 1970’s that the first clinical trials were conducted to see whether or not lowering blood pressure would improve patients’ lives. Not surprisingly, these studies showed a significant reduction in heart attacks and strokes following treatment for high blood pressure.

Hypertension in the long term can affect many organ systems, resulting in their damage (what is referred to as “target organ damage”). The most common effects are left ventricular hypertrophy, which is a concentric thickening of the heart muscle, kidney damage, and effects on the microcirculation of the eye (hypertensive retinopathy). However, the more catastrophic effects of hypertension are heart attacks and strokes. This is paradoxical and has been referred in the past as “the Birmingham paradox” (after the research group that first described it). The paradox is that in hypertensive patients, we have the blood vessels being exposed to high pressure, and one would expect that most of the strokes seen in hypertensive patients would be of a hemorrhagic nature. However, most strokes observed are thrombotic (due to a blood clot). This has been explained by the fact that there is significant platelet activation and endothelial dysfunction in these patients, which can lead to thrombosis rather than hemorrhage.

Headaches and visual disturbances are the common symptoms noticed in patients with high blood pressure. Most patients with hypertension however, do not have any symptoms and are often picked up on routine screening. Occasionally high blood pressure is picked up for the first time when patients present with either a heart attack or a stroke, hence the term, “silent killer”.

Our understanding of hypertension has changed and current guidelines for the management of hypertension suggest not merely trying to bring down blood pressure to a certain cut off level, but, importantly, assessing the overall cardiovascular risk of the patient (i.e. the risk of that particular patient developing a heart attack or stroke within the next 10 years). Along with pharmacological medications, lifestyle modifications are also very important. Dietary changes include reducing salt intake, as chronic increased salt ingestion is associated with a high risk of developing hypertension. In today’s world, we have to be careful, as there is a lot of “hidden” salt in our food. Most processed food (and indeed fast food) has a high salt content, mainly as preservatives, but these can over a long period of time cause hypertension. Reducing alcohol intake, increasing the amount of exercise, and eating what is often referred to as the “Mediterranean diet” can all help reduce blood pressure. The Mediterranean diet is one which is rich in fresh fruits and vegetables and fish.

However, all these life-style changes are limited in the amount of blood pressure reduction they can achieve. The mainstay of hypertension treatment involves tablets, of which there are many different classes. Although there are different subgroups of patients who would benefit from one group of drug over another, in general, most patients can be treated with most drugs. It is often difficult to persuade asymptomatic patients to take tablets that make them feel worse, due to the side effects, in the hope that they might prevent a heart attack or stroke. However, it is essential that patients are counselled with regards to the need for continuing with medications.

Thus we can see that attitudes towards high blood pressure have changed over the last century and indeed over the last few decades. Far from being “essential”, hypertension is now known to be fatal, and its management involves lifestyle changes in addition to pharmacological medications. Many public health initiatives to reduce the amount of salt in our food and provide clear labelling on salt content may go a long way in helping to reduce and prevent the development of hypertension. With better preventive and treatment strategies, it is hoped that in the future, this “silent killer” will not be as fatal as it is now.

Featured image by CDC/Amanda Mills acquired from Public Health Image Library [Public Domain], via FreeStockPhotos

The post Hypertension: more fatal than essential appeared first on OUPblog.

Four myths about the status of women in the early church

There is a good deal of historical evidence for women’s leadership in the early church. But the references are often brief, and they’re scattered across centuries and locations. Two interpretations of the evidence have been common in the last forty years. One claims that women were always excluded from church leadership, beginning with the biblical demand, “women should be silent in the churches” (1 Cor 14:34). The second argues instead that the church was open to women’s leadership in its early years, but excluded women from ordination as church institutions developed.

Although these explanations often represent opposing positions on women’s ordination today, they often share a lot in common in the ways they interpret the ancient evidence. Both interpretations have to explain away evidence that suggests that orthodox women were leaders, and they end up relying on similar arguments to do so. The four myths below can show up in either explanation, depending on who is doing the arguing.

Myth 1. Women were not ordained in the early church.

Many ancient sources identify women office holders. Some are burial inscriptions, like this one: “Tomb of Athanasia, deacon, and of Maria her foster child” (MAMA 3.212b). Some are writings of notable church fathers, who praise women leaders for their outstanding virtue. Other evidence comes from inscriptions donating items to a church, like the inscription on a marble column in a basilica, “Of Celerina, deaconess” (SEG 45-945).

Why did we forget these women? Gary Macy argues that the church revised its theology of ordination in ways that excluded women – but not until the 11th century. Before that, church liturgies included prayers for the ordination of women. As part of the revision process, theologians reinterpreted ancient sources in ways that denied that women had ever been ordained. Apparently their efforts had a lasting effect.

Ancient women were never viewed as the equals of men. In general, social norms and laws allowed men greater freedom and power than women. But this didn’t eliminate the leadership of women, who served as patrons, city officials, and religious leaders. Christian communities seem to have adopted similar patterns. Men were more likely than women to serve in official roles. Even so, women were commonly ordained to tasks their communities deemed important.

Myth 2. Women leaders were heretics. Orthodox Christians eliminated women’s leadership.

Early Christianity is very diverse, so it’s a good idea not to generalize too much. The evidence suggests that women were leaders in many Christian groups, including those we now think of as orthodox. It’s true that some church fathers make explicit statements against women serving in various roles. But these should not be taken as rules that applied to all communities of faith. Tertullian, for example, argues against women’s right to baptize. But other mainstream communities ordained women to play roles in baptism. There is a lot of conflicting evidence about women’s leadership, but it can’t be divided neatly into orthodox and heretical groups.

Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy: “Procession of the Holy Virgins and Martyrs”. Mosaic of a Ravennate italian-byzantine workshop, completed within 526 AD by the so-called “Master of Sant’Apollinare” from the Yorck Project. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy: “Procession of the Holy Virgins and Martyrs”. Mosaic of a Ravennate italian-byzantine workshop, completed within 526 AD by the so-called “Master of Sant’Apollinare” from the Yorck Project. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Myth 3. Women could only lead private groups of women.

Women often did lead groups of women, but in some cases they led men as well. When a leader was chosen for a religious or civic group in antiquity, preference was given to the person of highest status. Women sometimes had higher status than men — due to their wealth or family, or to their extraordinary virtue. If so, they were likely to be chosen as leaders. In a church that put a high value on sexual self-control; single-gender groups were a natural. But men might also seek a woman of acknowledged virtue and status as their leader.

Were these groups ‘private’ rather than ‘public’? Ancient women were ideally described as limited to the private realm. This is somewhat misleading for modern readers, who tend to think of ‘private’ as restricted to the home and domestic labor. For Romans, however, ‘private’ life included commerce, education, religion, and social relations. Women participated in all of these ‘private’ activities, and did so with approval. Religious leadership was also civic in nature because it secured divine favor for the community.

Myth 4. Celibate women could lead, but married women were subject to their husbands.

Some women leaders were married. Women in the Roman world maintained control over much of their property during marriage and thus had access to wealth, an important factor in social status. Like their unmarried counterparts, married women served as patrons, gave gifts, made loans, dedicated buildings and served as civic and religious leaders. Marriage contributed to a woman’s social status, and might therefore increase her opportunities for leadership.

Chastity was a virtue prized by the church in its earliest centuries. Chastity was related to self-control, an important quality of leaders because it meant they could consider the needs of the whole community. So it is not surprising that many leaders were celibate. But chastity was encouraged for all Christians — whether married or unmarried. Christian writers agreed that married persons could — and should — practice sexual self-control. Some women leaders practiced celibacy while remaining married.

The post Four myths about the status of women in the early church appeared first on OUPblog.

Health inequalities: what is to be done?

The research literature on health inequalities (health differences between different social groups) is growing almost every day. Within this burgeoning literature, it is generally agreed that the UK’s health inequalities (like those in many other advanced, capitalist economies) are substantial. There is, for example, a shocking 28 year gap in life expectancy for working age men living in different areas of Glasgow. There is also agreement that health inequalities are largely preventable (i.e. the factors the cause health inequalities are not randomly distributed but the direct consequence of social, political and economic decisions) and that these substantial differences are, therefore, unjust. Yet, when it comes to answering the obvious question, ‘what should we do to tackle health inequalities?’, specific policy advice often seems limited. Why is this?

The civil servants, policy advisors, politicians and health campaigners I’ve interviewed over the past 12 years have often (understandably) assumed that the lack of clear policy advice emanating from health inequalities researchers reflects a lack of consensus. Yet, I was puzzled by this: my interviews with researchers suggested a high degree of consensus within the research field about both the causes of health inequalities and the main policy levers for reducing health inequalities. This was despite the fact I had tried to ensure I was interviewing researchers with different perspectives on health inequalities (based on their published research).

Surveying researchers about their views on policy proposals for tackling UK health inequalities

To explore the issue further, I worked with a colleague, Mor Kandalik Eltanani, to undertake an online survey of researchers involved in studying health inequalities in the UK which involved asking respondents a series of questions about their views on various potential policy responses to health inequalities. First, we used interview data, focus groups, and published literature and reports to identify 99 distinct policy proposals which we then organised into the ten thematic clusters (this included, for example, a cluster focusing on ‘income and wealth’ as well as various clusters focusing on particular ‘lifestyle’ issues such as alcohol, food, and tobacco). We then developed a two-stage online survey using these 99 proposals. The first stage of the survey asked researchers to indicate their level of agreement (five options, from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’) with each of the 99 policy proposals according to various criteria: (1) their ‘expert opinion’; (2) the strength of the available evidence; and (3) what they felt, in current economic, political and social context, would be an ‘appropriate policy recommendation for the health inequalities research community to make’. Forty-one researchers completed this part of the survey.

For the second stage of the survey, we identified the most popular 20 proposals from the first stage (combining the responses given for each of the three criteria listed above) and asked respondents to each divide 100 points between these proposals, allocating more points to the proposals they believed would have the greatest impact on reducing health inequalities in the UK. Ninety-two researchers completed this (much quicker) part.

What we found: researchers respond differently when asked about policies based on their ‘expert opinion’ and policies supported by ‘available evidence’

One of our key findings was that researchers generally responded to policy proposals rather differently, depending on the criteria they were being asked to take into consideration. When researchers were asked to say which policy proposals they agreed would be most effective in reducing health inequalities based purely on their expert opinion, most agreed that we need policies to achieve a fairer distribution of income/wealth. When asked to respond to the same policy proposals based on their sense of the strength of the available evidence, the most popular policy proposal remained one concerning tax and benefits policy to redistribute wealth, beyond this, there was far more of a focus on policy proposals intended to reduce lifestyle-behavioural risks (smoking, drinking, etc).

Why did researchers respond differently to the different criteria?

One potentially obvious interpretation of these differences is that researchers’ personal preferences are informed by factors other than the available evidence (e.g. that they are ideologically driven). There may be some truth in this but my interviews and the feedback in the free-text spaces in the survey suggest the differences are, instead, largely a reflection of the fact, as Ted Schrecker argues, that it is simply easier to study the health impacts of policy changes that attempt to change people’s drinking, eating and smoking behaviours than it is to study the health impacts of macro-economic policies, such as tax and benefits policies. As a result, we have more evidence about the former and less about the latter, even though there seems to be a high-level of agreement amongst health inequalities researchers that the latter kinds of policies are more important for health inequalities. This suggests health inequalities researchers, and those who fund this work, need to get better at matching their research activities with their sense of what is likely to be most effective in reducing health inequalities.

Featured image: “Medicine” by DarkoStojanovic. CC0 via Pixabay

The post Health inequalities: what is to be done? appeared first on OUPblog.

Compassionate law: Are gay rights ever really a ‘non-issue’?

On his recent visit to Kenya, President Obama addressed the subject of sexual liberty. At a press conference with the Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, he spoke affectingly about the cause of gay rights, likening the plight of homosexuals to the anti-slavery and anti-segregation struggles in the United States. He declared that he was ‘painfully aware of the history when people are treated differently under the law … That’s the path whereby freedoms begin to erode and bad things happen. When a government gets in the habit of treating people differently, those habits can spread.’

Under Kenyan law, gay sex is punishable by up to 14 years in prison and homosexuals claim that they are routinely subjected to violent harassment.

The Kenyan President was unimpressed by Mr Obama’s plea. He stated that although the two countries shared a number of values, there were ‘some things that we must admit we don’t share … I repeatedly say that for Kenyans today the issue of gay rights is really a non-issue. We want to focus on other areas … maybe once, like you, have overcome some of these challenges, we can begin to look at other ones, but as of now the fact remains that this issue is not really an issue that is at the foremost minds of Kenyans and that is a fact.’ He was applauded.

The law in Africa lags behind the position in many Western countries. Of the continent’s 54 countries, only one, South Africa, has legalized same-sex marriage. And in many others, antagonism toward LGBTQ rights is overwhelmingly high. In a recent survey of Nigerians, for instance, 98 per cent of respondents expressed negative views about homosexuality. Similar hostility has been recorded in surveys in other African states.

How should we respond to this prejudice?

Different strokes

Democratic countries should, of course, have the right to determine what is morally acceptable to their own communities. Matters such as contraception, abortion, LGBTQ rights, and same-sex marriages are inescapably contentious – even in advanced Western societies. They continue to generate divisive, often acrimonious, debate in the United States, Europe, and other societies. Indeed, it is only relatively recently that English law abolished the offence of homosexual acts and amended the law on abortion to recognize, in effect, a woman’s right to choose.

‘Gay Marriage,’ by unsplash. Public domain via Pixabay.

‘Gay Marriage,’ by unsplash. Public domain via Pixabay.But the question remains: is criminalizing homosexual acts any longer acceptable? Is it OK for a president of a democratic African country to proclaim in 2015 that gay rights are a ‘non-issue?’ It is, of course, not a non-issue for gay Kenyans, but the majority of Kenyans would presumably reply that where the practices of minority offend the moral or religious convictions of the majority, they may legitimately be outlawed.

Law and morals

There is an inevitable tension between law and morality. In my VSI, I suggest that the relationship between the law and the moral practices adopted by society may be represented by two partially intersecting circles. Where they overlap we find a correspondence between the law and moral or ethical values (for example, murder is both morally and legally prohibited in all societies). Outside the overlapping zone, exist, on the one hand, acts which are legally wrong, but not necessarily immoral (for example, exceeding your time on a parking meter) and, on the other, conduct which is immoral, but not necessarily unlawful (such as adultery). The greater the intersection, the more likely the law is to be accepted and respected by members of that society.

Yet, although we cannot easily evade moral questions, there is an increasing recognition in the world that a fair, decent society requires that it treats all its members equally. This is a fundamental element of the concept of the ‘rule of law.’

The rule of law

The roots of this ideal date back to Magna Carta of 1215. Its modern incarnation is most closely associated with the English constitutional scholar Albert Venn Dicey, who in 1885 expounded the fundamental precepts of the British constitution, and especially the concept of the rule of law which, in his view, included the principle of equality before the law described as ‘the equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary law of the land administered by the ordinary courts.’

This is a narrow view of equality, and although contemporary conceptions of the rule of law attempt to adapt Dicey’s rather formal idea to substantive matters of legality, authority, and other elements of democratic governance, even a fleshed-out notion of the rule of law would not seem to preclude a democratic country from legislating against homosexual acts. In other words, while the rule of law dictates that all be treated equally; this applies merely to the equal submission of all to the same law. Where legislation, democratically enacted, discriminates against a minority, do we have the right to condemn?

The law and human rights

Nowadays moral claims are frequently transformed into moral rights: individuals assert their rights to a whole range of goods, including life, work, health, education, and housing. Peoples assert their right to self-determination, sovereignty, free trade, and other desired ends.

Such rights have acquired significance so profound that they are sometimes regarded as synonymous with law itself. Declarations of political rights are often regarded as the trademark of present-day democratic statehood. And the inexorable clash between rival rights is among the distinctive features of a liberal society.

On the international front, a panoply of human rights conventions and declarations attest to the strength of rights talk. The UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, and the International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights, and on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in 1976, reveal, at least in theory, a commitment by the international community to the universal conception and protection of human rights. It exhibits a significant degree of cross-cultural consensus among nations.

It is here, therefore, that we should look to champion and defend the rights of those whose sexual preferences differ from those of the majority. Unless it can be conclusively demonstrated that such acts cause palpable harm to others or to society at large, we ought to repudiate intolerance (even when legally enforced), and embrace the view advocated by the great nineteenth century liberal thinker, John Stuart Mill:

“[T]he sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant.”

In a caring, compassionate, generous world, gay rights can hardly be considered a non-issue.

Featured image credit: ‘Pride’, by nancydowd. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Compassionate law: Are gay rights ever really a ‘non-issue’? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 3, 2015

Between the stacks – Episode 26 – The Oxford Comment

Aside from announcing the start of another academic semester, September also marks an essential, if lesser-known, holiday celebrated since 1987: Library Card Sign-up Month. Once a year, the American Library Association (ALA)—working in conjunction with public libraries across the country—makes an effort to spotlight the essential services provided by libraries now and throughout history. But what, exactly, are the origins of the American public library? Moreover, at a time when government services are being pared down by state lawmakers, how have public libraries survived (and even thrived) in a time of economic downturn?

In this month’s episode, Sara Levine, Multimedia Producer for Oxford University Press, sat down to chat with Wayne A. Wiegand, author of Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library, New York City Librarian Emma Carbone, and Kyle Cassidy, creator of Alexandria Still Burns, a project featuring interviews with over one hundred librarians across America. From Benjamin Franklin’s Library Company of Philadelphia to the safe haven the Sweet Auburn Branch provided to African Americans, we explore America’s love affair with the public library, tracing its evolution alongside political, technological, and demographic shifts and its adaptation to our digital era.

Image Credit: “New York Public Library” by draelab. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Between the stacks – Episode 26 – The Oxford Comment appeared first on OUPblog.

Getting to know Celine in music marketing

Our New York office has welcomed a new assistant to our cubicle jungle. Celine Aenlle-Rocha joined the marketing team in August 2015 after recently graduating from college. We sat down with her to talk about publishing, New York, and sweaters.

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found about working at OUP?

I didn’t realize beforehand how much I’d able to interact with different departments. I’m in marketing but I get to work with editorial, sales, production, and publicity.

What’s the least surprising?

There are a lot of interesting books in the building, and I will never be able to read them all.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

Scheduling tweets, making flyers, reading reviews of our music books, and getting to know the music community.

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

Just getting to know people around the office!

What one resource would you recommend to someone trying to get into publishing?

I attended the Columbia Publishing Course right before I started at Oxford, and it was the best preparation for my job that I could’ve asked for. I learned so much about publishing and marketing that’s really helped me in for my first job.

Celine Aenlle-Rocha

Celine Aenlle-RochaWhat’s your favourite book?

Jane Austen’s Emma. It’s not her most popular book, but it inspired Clueless, which is just amazing.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

I’ve always wanted to try travel writing – hopefully I’d be visiting Oxford in the UK!

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

Eat my yogurt and check my email. It’s not very exciting, but for some reason I don’t get hungry until after my day’s already started.

Who inspires you most in the publishing industry and why?

I love how much Oxford cares about books, literacy, and readers. I enjoy working for a non-profit and knowing that my work benefits the University of Oxford as well as the general readership.

How would you sum your job up in three words?

Challenging, exciting, and fun!

What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in the publishing industry since working at OUP?

Everything is online now, and that influences a lot of the work I do in publishing as well as a marketing assistant. I don’t think it’s a bad thing, it just makes it more of a fun challenge.

What is in your desk drawer?

A sweater. I get cold so easily…

What is your most obscure talent or hobby?

I knit a lot of sweaters. Definitely not as many as I’d like, however, because they take too long! But I love to knit and sew.

What is your favorite animal?

My dogs! They’re in California, which is much too far away.

Featured image: Hyacinth and book. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Getting to know Celine in music marketing appeared first on OUPblog.

The reptiles of Thailand [interactive map]

Thailand is one of the most ecologically diverse countries in the world, housing more than 350 different species of reptiles. Learning about these turtles, tortoises, lizards, crocodiles, and snakes is more important than ever, in light of recent threats to their extinction due to wildlife trade and loss of habitat for agricultural use of their habitat. Explore this map to discover a glimpse of Thailand’s rich reptilian population, with fun facts about each species from A Field Guide to the Reptiles of Thailand.

Featured image credit: Large-eyed Pit Viper by tontantravel. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The reptiles of Thailand [interactive map] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers