Oxford University Press's Blog, page 617

September 14, 2015

My life as a ‘career Special’

In 2004, I was waiting on a tube platform and spotted posters asking: ‘Police – could you?’. I thought about that a lot and realised, at that point in time, I couldn’t. I didn’t feel certain enough that, in difficult situations, I would have good enough judgement to always do the right thing. Fast forward ten years and I’d done a fair bit of growing up. I’d worked in a police force and spent a lot of time with officers – both regulars and Specials. I saw how their work involved a hugely complex mix of skills in communication, split-second reactions, legal knowledge, and protecting the most vulnerable in our communities. I reckoned that, finally, I was up to the challenge and had time, skills, and commitment to offer. Turns out, that decision was the easy bit…

My journey from application to warrant card is a story for another time, but I’m four stones lighter, I laugh in the face of the dreaded bleep test, can reel off mnemonics like my times tables, have a new appreciation of effective fabric conditioner, and know the closing times of every good take-out place in Brighton. I’ve also found personal strength I never believed I had, fallen into step with ambulance and coastguard colleagues trying to save lives, and told a mother that she won’t ever see her son again.

Not every shift is a good one. I’ve cried in the locker room, lain awake all night worrying I missed something in a search, and every week I wonder if I’m good enough to be doing this and wearing this uniform.

My intention is to remain as a ‘career Special’. Because recruitment for regular officers has been so scarce over the past few years, most of those training with me as Specials did so as a route into policing as a profession. I love my day job and I have no plans to give it up. I believe that having Specials with workplace experience outside policing can bring real benefits to forces – not as substitutes for regular officers but to boost numbers and specialist skills, bringing in expertise in areas where forces aren’t yet able to offer training.

At a time when officer numbers have been reduced in all forces, I see how claims of Specials being recruited as ‘policing on the cheap’ come about, and how some officers feel that the money spent training Specials could be invested in training regular officers instead. I don’t think I can make that situation any better by quitting – instead I show up and do a good job where I can. We’re lucky; in Brighton, regular and PCSO colleagues are incredibly generous and step in often with offers of support, development, and opportunities. We have some brilliant long-term Specials who offer help and guidance to those of us who still have a shiny hi-vis and a squeaky stab vest. Every time I book on duty, I am grateful for the knowledge, support and humour of my colleagues, uniformed or not, paid or voluntary.

Not every shift is a good one. I’ve cried in the locker room, lain awake all night worrying I missed something in a search, and every week I wonder if I’m good enough to be doing this and wearing this uniform. Even on the toughest shift, though, the trust placed in me makes me stand up taller and listen more patiently, because I can choose to do this or not to do this – and I choose to turn up, turn out, and do what I can.

Featured image credit: Officers on beat by West Midlands Police. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post My life as a ‘career Special’ appeared first on OUPblog.

From ad hoc arbitral tribunals to permanent courts: three examples

Should investment disputes be solved by a permanent court or by arbitral tribunals? This is one of the key questions that might kill the efforts for what would be the largest regional free-trade agreement in history, covering 46% of world GDP: the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). Cecilia Malmström, the European Commissioner for Trade, stressed the point again a few days ago.

It isn’t the first time that the question looms large whether certain disputes should be resolved by arbitral tribunals, appointed in an ad hoc manner for each new dispute, or by a permanent court. Let us briefly recall two such earlier debates, and then elaborate a bit on the current situation in the TTIP.

In 1907, the Second Hague Peace Conference, one the world’s most important attempts to reduce war by strengthening the systems available for the pacific settlement of international disputes, had to grapple with exactly that issue: should interstate disputes be resolved by arbitration, as was the case up to then, or by a permanent court? The United States didn’t like arbitration. They thought it was too expensive and prevented the development of a reliable body of case law. The US delegate to the conference argued that the costs of dispute resolution should be split among all nations; after all, peaceful settlement is in the interests of a wider community than the parties to the dispute. The same idea that the court acts on behalf of a wide community, rather than being only the agent of the disputing parties, makes its rulings relevant for the wider community, clarifying the law for the wider community. Each new dispute is an opportunity to advance the law, to improve it and to harness bellicose states even more.

But the resistance to a permanent court was strong. It took 15 years more to create the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ), the predecessor of the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Clearly the World Court has contributed enormously to the development of international law. Few would contend that its creation was a mistake. Yet it isn’t without shortcomings, chief among them being, probably, the less than ideal level of independence of its judges from political powers.

Let us fast forward. Twenty years ago, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the London Court of International Arbitration, a proposal was made to create an international court of arbitral awards. This would have been a permanent international court which would replace national courts in dealing with annulment, recognition, and enforcement of awards. Arbitral awards, instead of being challenged in the courts of the seat of each arbitration, would be challenged – and annulled or upheld – before that international court. The party losing the arbitration wouldn’t oppose the recognition or enforcement of the award in the courts of the place where the assets are located that the prevailing party wants to go after. That opposition would take place before the permanent international court. So the idea here was not to replace arbitration by a permanent court, but to replace national courts by a permanent international court.

The resistance to this proposal essentially took the form of what economists and political scientists call satisficing: searching not for the best possible alternative (so-called optimal decision-making), but aiming for a threshold of acceptability. In other words, the current system is not ideal but it is good enough. The additional loss of state control over arbitration, entailed by the proposal for an international court of arbitral awards, wasn’t perceived to be worth the additional improvement of the working of international commercial arbitration.

Now to the question of the judicialization of investment disputes and the TTIP. Why should these disputes not be dealt with by a permanent court? Why should the TTIP not include a dispute settlement provision providing that all disputes between an investor and the host state of the investment shall be resolved by a permanent investment court specific to the treaty?

Satisficing, here, would be a risky argument. To say that the current system of investment arbitration works well enough – reaches a threshold of acceptability – not to warrant the additional complications that the creation of a permanent court would entail, would be a risky argument. True, the criticism and worries expressed by academics and civil society hasn’t caused any meaningful renegotiation of the various treaties that create the investment arbitration system. But that may well be due to the fact that the “backlash” hasn’t yet trickled down to the level of states and public decision-makers. Most states know less than we, who read posts like this, probably think they do.

The idea that we don’t need a sound judicial creation of international investment law wouldn’t be a good argument either. The law that investment arbitral tribunals have created so far is, by mostly every account, too fragmented and inconsistent. But even consistency alone, which theoretically could be achieved with the current system, wouldn’t fix the soundness of the law produced. Consistency isn’t a silver bullet. It is only good if the contents of the law are sound. suggests that investment arbitrators are one of three kinds: either they are investor friendly; or they are “social” and then they award states lower compensation but take decisions on the merits that are effectively investor-friendly; or they are of a managerial type and then they make fact-intensive decisions. In his argument, the result is that the investment law that gets created would either remain fragmented (fact-intensive) or get ever more investor-friendly. A permanent court might be more balanced.

The one count on which a permanent court would probably fare less well than the current arbitral system is independence from political powers. But that, precisely, is what the political powers negotiating the treaty may want dearly.

Featured image credit: Global network concept. (c) braverabbit via iStock.

The post From ad hoc arbitral tribunals to permanent courts: three examples appeared first on OUPblog.

Twelve important figures in the modern history of wine

Many people have influenced the world of wine over the course of the last 400 years. They have changed, developed, and perfected the winemaking process, introduced grapes and viticulture to different continents, and left their mark on an industry that has been with us since the dawn of civilization. Below is a timeline that highlights twelve of the many important figures who have had a significant impact on the world of wine as we know it today.

Featured image credit: Wine cellar in Chvalovice near Znojmo, by Che. CC BY-SA-2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

September 13, 2015

English in 2065

This month, students are heading back to school many recent high school graduates are off to college. At institutions across the country, deans are dutifully studying the Beloit College Mindset List to remind their faculty of the recent cultural experiences that have shaped the today’s youth—and to remind us of how much the world has changed.

While language is seldom part of the Mindset List, it too changes alongside cultural touchstones. Yesterday’s ironic novelty or fresh metaphor becomes today’s common usage and tomorrow’s cliché. The passage of time will settle many, but not all, of the grammatical disputes of our day. Those who worry about the language of others will give up on old peeves and find new things to try to police. And if you have any doubts that attitudes toward correctness evolve, just take a look the “Words and Phrase Commonly Misused” section of The Elements of Style over the years.

Since fall is also the season for prognostication—the 2016 election, the World Series, the Oxford Dictionary Word of the Year, holiday sales figures—I want to offer some predictions about tomorrow’s English. What will the English language be like when today’s students begin to retire? Here is a baker’s dozen of not-quite scientific predictions for English in 2065, most of which are already underway.

The word segue will have been replaced by the spelling Segway, as in “Now, let me Segway into a new topic.” It’s just too logical to not take hold.

The word coupon will become like economics. No one will notice if you pronounce it COOP-on or CUE-pon.

The compound mountain lion will continue to gain in popularity over the alternative cougar, which causes problems for headline writers and search engines because of its secondary meaning.

Almost all one- and two syllable nouns will be used as verbs: to gift, to gym, to verb, to tweet, to car, to Facebook, to adult, to coffee, to effort, to action.

The verb do will continue to blend with the verb have in expressions like “I’ll do the braised chicken wrap.”

The adverb hella will be in widespread use across the country, except in New England, where wicked will be maintained, and among children under ten, who will say hecka.

We will no longer be freaked out by—or even notice—uptalk or the pronunciation of nuclear as “nukular.” There will, however, still be efforts to stamp out the use of literally to mean figuratively, including a short-lived ironic use of “illiterally” at some point.

English teachers will win the battle to suppress the use of off of to mean from (as in, I got it off of the internet). Instead, they will begin to turn their attentions to the expression blasé faire (for laissez faire) and to site being used for cite (a mistake that will arise because most citations will be from websites).

The merger of vowels will continue with Dawn and Don, and Erin and Aaron, becoming homophones for most speakers.

The verb to out will lose any association with sexual orientation and will simply mean to reveal something kept secret.

The expression by accident will be replaced by on accident.

Your guys’s will be the standard plural possessive, except in two places: the South, where y’all’s will predominate, and in fancy restaurants.

Dude will be gender neutral.

Print this out and save it. Then check back with me in fifty years to see how close I came with these predictions. In the meantime, what do you think will change in the English of 2065?

Image Credit: “Into the Future” by Natalie Schmid. CC BY NC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post English in 2065 appeared first on OUPblog.

Grandparents’ Day: A reading list

On Sunday 13 September, the United States will celebrate National Grandparents’ Day. This annual holiday, held on the first Sunday after Labor Day, celebrates our grandmothers and grandfathers. Marian McQuade, grandmother to 43 and great-grandmother of 15, is widely credited with founding the holiday. She believed the nation should celebrate the many contributions older adults have made to U.S. history; her dream was put into action in 1978 when then-President Jimmy Carter signed a proclamation to “honor grandparents…and to help children become aware of strength, information, and guidance older people can offer”.

With older adults living longer than ever before, the number of children who have living grandparents (and great-grandparents) has risen dramatically throughout the 20th and 21st century. More than 65 million Americans now identify as grandparents. The role of grandparent has changed dramatically in recent decades, with more grandparents living with or serving as primary caretaker to their grandchildren. Roughly 10% of grandparents live with their grandchildren, often because their own children are unable to care for their offspring.

Grandparenthood today is filled with joy, but also with stress and challenge. In celebration of Grandparents’ Day 2015, we have created a reading list of new articles from Gerontological Society of America journals that reveal the challenges facing grandparents, the ways that our relationships with our grandparents shape our own lives and well-being, and how grand-parenting is intertwined with other social roles, like volunteering and work.

‘Race/Ethnic Differentials in the Health Consequences of Caring for Grandchildren for Grandparents’ by Feinian Chen, Christine A. Mair, Luoman Bao, and Yang Claire Yang, in Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences.

This study finds that grandparents who babysit their grandchildren a moderate amount have better health than those who don’t babysit, especially Hispanic grandparents. Living with grandchildren harms one’s health, especially among White and Black grandparents, although these health declines are lessened for those with high levels of education, income, wealth, and social support. Black grandparents who live with grandchildren without the child’s parent present experience greater health declines, due to the stress of full-time care giving.

‘Social Support and Grandparent Caregiver Health: One-Year Longitudinal Findings for Grandparents Raising Their Grandchildren’ by Bert Hayslip Jr., Heidemarie Blumenthal, and Ashley Garner, in Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences.

This study shows that grandparents, especially grandmothers, caring for their grandchildren are at a heightened risk of depressive symptoms and poorer quality health, although social support protects against these symptoms. Social support helps to mitigate against the stressors related to caring for grandchildren, such as feeling trapped by one’s responsibilities or having to discipline one’s grandchildren. Programs to help increase social support and to enhance parenting skills may protect stressed grandparents from compromised physical and mental health.

Image Credit: for reading grandmother grandchild by dassel. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image Credit: for reading grandmother grandchild by dassel. Public Domain via Pixabay.‘Solidarity in the Grandparent–Adult Grandchild Relationship and Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms’ by Sara M. Moorman and Jeffrey E. Stokes in The Gerontologist.

Researchers explored how three aspects of grandparent-grandchild relationships affect the mental health of both generations; emotional closeness, frequency of contact, and the exchange of practical help and advice. For both grandparents and adult grandchildren, greater closeness reduced depressive symptoms. For grandparents only, receiving practical support yet not providing such support to grandchildren, was linked with more depressive symptoms in the older generation. Grandparents and grandchildren can be an important source of emotional support for one another, although interactions in which the older generation feels dependent or burdensome may harm their psychological health.

‘Grandparenthood and Subjective Well-Being: Moderating Effects of Educational Level’ by Katharina Mahne and Oliver Huxhold, in Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences.

This article shows that higher quality relationships with adolescent and adult grandchildren are linked with higher levels of life satisfaction, positive affect and negative affect, and lower levels of loneliness among older adults. However, the benefits of grandparenthood are considerably smaller for grandparents with lower levels of education. The authors note that better educated and financially well-off grandparents might enjoy light-hearted leisure time with their grandchildren, whereas economic strain among poorly educated older adults may be linked with more sorrowful or dependent relationships.

‘Grandparenting Roles and Volunteer Activity’ by Jennifer Roebuck Bulanda and Margaret Platt Jendrek, in Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences.

Volunteering is an important way for older adults to remain socially and cognitively engaged; this paper explores whether caring for grandchildren fosters or impedes volunteering among older adults. The authors find that grandparents raising coresidential grandchildren are less likely to volunteer, compared to grandparents providing no regular grandchild care. However, grandparents who provide nonresidential grandchild care are the most likely of all to volunteer. The stress and time demands of raising and living with a grandchild pose an obstacle to other forms of social engagement, while the less stressful non-coresidential care facilitates volunteering.

‘What Drives National Differences in Intensive Grandparental Childcare in Europe?’ by Giorgio Di Gessa, Karen Glaser, Debora Price, Eloi Ribe, and Anthea Tinker, in Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences.

Researchers explored associations between intensive grandparental child care and work behavior across 11 European nations. Higher levels of intensive grandparental childcare were found in countries with low labor force participation among younger and older women, and low formal childcare provision, where working mothers rely on grandparental support on an almost daily basis. The authors conclude that encouraging older women to remain in the workforce is likely to affect grandchild care which in turn may affect mothers’ employment, particularly in Southern European countries where there is little formal childcare.

Image Credit: Cooking chef teaching granny by PublicDomainPictures. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Grandparents’ Day: A reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know the film adaptations of Shakespeare’s work? [quiz]

It’s fun to read Shakespearean plays, but watching our most beloved scenes on stage or screen makes the characters and the plots even more engaging. Reading the scene in which Juliet wakes up to find her Romeo dead is indeed tragic, but watching Claire Danes and Leonardo DiCaprio lock eyes right before he dies is heart-wrenching. Gazing, unable to reach through the screen and offer help, as Ralph Fiennes is outnumbered and murdered in his directorial debut, Coriolanus, is unparalleled.

Movie and television adaptations of Shakespearean plays are numerous, and in many languages other than English, but how many of them do you know? Test your knowledge of Shakespeare film in this quiz, from the early 20th century to the present day.

Featured Image: Lobby card from the 1936 MGM film Romeo and Juliet. Pictured are John Barrymore, Leslie Howard, and Basil Rathbone. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know the film adaptations of Shakespeare’s work? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Paradoxes and promises

Imagine that, on a Tuesday night, shortly before going to bed one night, your roommate says “I promise to only utter truths tomorrow.” The next day, your roommate spends the entire day uttering unproblematic truths like:

1 + 1 = 2.

The grass is green.

The sky is blue.

She continues on, in this vein, until going to bed. As she is about to fall asleep (and we assume she goes to bed before midnight), she proudly pronounces:

I kept my promise.

The question is this: Has she?

Your roommate’s pronouncement has a similar logical form to the truth-teller:

This sentence is true.

Unlike the Liar paradox:

This sentence is false.

which is true if false, and false if true, the truth-teller is true if true, and false if false. So it is indeterminate between the two truth-value assignments – it could be either one, and no inconsistency, incoherence, or any other sort of problem arises either way.

Likewise, your roommate’s pronouncement is, logically speaking, indeterminate. If we assume that is true, then in fact every one of her pronouncements on Wednesday was true, and hence she kept her promise. If, however, we assume it is false, then in fact it is not the case that each of her pronouncements on Wednesday was true, and so she failed to keep her promise.

But there seems (in my mind, at least) to be a strong intuitive push to attribute truth to your roommate’s assertion. In other words, it would be totally perverse to respond to your roommate’s assertion along the lines of:

Well – perhaps not. Maybe you are lying right now!

But why is this? After all, nothing in the logic of the situation seems to privilege an assignment of truth to your roommate’s assertion over an assignment of falsity.

It is worth examining how other, superficially similar situations work. First, note that if your roommate had, on Tuesday, promised to only tell truths on Wednesday, and then said true things throughout the course of the day on Wednesday, and then, just before falling asleep, finished off the day with:

I didn’t keep my promise.

then we have a paradox. If the last sentence is true, then every sentence uttered by your roommate is true, so she kept her promise, so the last sentence must be false. But if the last sentence is false, then your roommate did not utter only truths on Wednesday, so she didn’t keep her promise, so the last sentence must be true.

Similarly, if you roommate, on Tuesday, promised to only utter falsehoods on Wednesdsay, and then on Wednesday said only false things like:

1 + 1 = 3.

Grass is blue.

The sky is green.

during the day and finished up the day with:

I kept my promise.

then we, again, have a paradox.

The final case, however, is the most interesting. Imagine that your roommate, on Tuesday night, promised to only state falsehoods on Wednesday, and then made only false claims during the next day, and finished up the day with:

I didn’t keep my promise.

Here there is no paradox. If the final claim is true, then she didn’t keep her promise, because at least one of her assertions (in fact, this last one) is not false. If the claim is false, however, then she did keep her promise, but is lying to us about it.

So this fourth case, like the one we started with, is indeterminate: there seems to be nothing in the logic of the situation that privileges either assignment – truth or falsity – to the final claim made by your roommate.

But what is interesting in this case is that (again, at least in my mind) there is no intuitive ‘push’ to assign truth to your roommate’s claim, rather than falsity. This makes it rather different from the first case. The question is why it is so different.

The answer, I think, lies in looking at more than the logic of the sentences in question. In particular, it lies in noticing that, when we are communicating linguistically, we are implicitly agreeing to live up to certain expectations, and interpreters construct their understandings of our utterances (and their truth values) in part in virtue of these same expectations.

The first such default expectation on the part of interpreters is that we will tell the truth (at least most of the time). Thus, listeners are justified in adopting something like the following principle, when interpreting our utterances.

Truth-telling Principle:

All else being equal, I should attempt to interpret speakers as if they are telling the truth.

Of course, things are not always equal. But the upshot of this principle is this: when confronted with an apparently sincere utterance that has two interpretations, where on one interpretation the utterance is true, and on the other interpretation the utterance is false, and where there are no other reasons to prefer one of these understandings of the utterance over the other, listeners should opt for the interpretation that makes the assertion true, since this accords with the expectation that speakers generally tell the truth.

The second expectation is that we will keep our promises (again, at least most of the time), and hence we have a second principle:

Promise-keeping Principle:

All else being equal, I should attempt to interpret speakers as if they are keeping their promises.

Again, things are not always equal. But the upshot of this principle is this: when confronted with an apparently sincere utterance that has two interpretations, where on one interpretation the speaker is keeping a promise, and on the other interpretation the speaker is failing to keep that same promise, and where there are no other reasons to prefer one of these understandings of the utterance over the other, listeners should opt for the interpretation where the speaker is keeping her promise, since this accords with the expectation that speakers generally tell keep their promises.

We can now easily explain the intuitive difference between the first and fourth case described above. In the first case we have two choices: either your roommate is telling the truth (and hence also keeping her promise), or your roommate is lying (and hence failing to keep her promise). Both of the two principles described above weigh in favor of the first option, however, so we are strongly motivated to assign truth to your roommate’s utterance.

In the second case, however, things don’t work out so uniformly. Again, we have two choices: either your roommate is telling the truth and hence failing to keep her promise, or your roommate is lying and hence keeping her promise. What we called the Truth-telling Principle weighs in favor of the first option, but Promise-keeping Principle weighs in favor of the second option. The two principles conflict, and hence we remain undecided between the two options, with no intuitive preference for one over the other.

Image credit: “Truth”, by Daveblog. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Paradoxes and promises appeared first on OUPblog.

September 12, 2015

Finding wisdom in Old English

Anglo-Saxon literature is full of advice on how to live a good life. Many Anglo-Saxon poems and proverbs describe the characteristics a wise person should strive to possess, offering counsel on how to treat others and how to obtain and use wisdom in life. Here are some words in Old English (the name we give to the Germanic language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons) that describe what a wise person should aspire to be—and some qualities it’s better to avoid.

wis

Old English had many words for ‘wise’: wis, gleaw, snotor, and more. Frod seems to describe someone who’s grown wise from experience, while someone who is learned in books can be called boccræftig. There are plenty of words to describe the opposite quality, too: a person who is not very wise may be unwis or samwis (like Tolkien’s simple, though very loyal, Samwise Gamgee), dollic (‘foolish’), or dysig (‘stupid,’ related to our dizzy).

wærwyrde

The right and wrong way to use speech is a recurring concern in Old English poetry. A wise person should be wærwyrde ‘careful with speech’ (as if ‘wary with words’), and there are many faults to be avoided in speaking. One should not be hrædwyrde ‘hasty with words’, or oferspræce ‘too talkative’ (like a person who ‘over-speaks’), or twispræce‘double in speech,’ deceitful or overly flattering (the verbal equivalent of being ‘two-faced’). Anglo-Saxon poems often point out that it’s easy to talk big, but not always so easy to match actions to words. As a character in Beowulf says, every warrior needs to be able to recognize the difference between worda and worca, ‘words’ and ‘works.’

geþyldig

We’re told that a wise person should be geþyldig, ‘patient, forebearing’ and not hatheort ‘hot-hearted, impulsive’; as an Old English proverb says ‘Geþyld byþ middes eades’, ‘patience is half of happiness.’ The wise should act moderately (gemetlice) to both friends and foes, and ought to avoid anger (irre) and drunkenness (druncen). Young people should be taught self-control; ‘stieran mon sceal strongum mode,’ one poem advises, ‘a strong mind needs to be steered.’

rumheort

Generosity was an important quality for Anglo-Saxon lords, who were expected to retain the loyalty of their followers by distributing rich gifts (gifa). One proverb points out, a little cynically, that ‘Swa cystigran hiwan, swa cynnigran gystas’—‘the more generous the household, the more noble the guests.’ But not all the language of generosity is so pragmatic, and Old English poetry has one especially evocative compound meaning ‘generous’: rumheort, literally ‘roomy-hearted.’ It suggests someone who is great in spirit, generous with more than just possessions—much as we might say someone has a ‘big heart.’

leohtmod

A poem known as Precepts advises that the best way to be happy is to be georn wisdomes ‘eager for wisdom’ and leoht on gehygdum ‘light in your thoughts’—to be cheerful and friendly rather than resentful and critical. Another poem says that a woman should be leohtmod, ‘light in spirit,’ as well as rumheort with her gifts. She should keep secrets (rune healdan) and give her husband advice (ræd). As you’ll have gathered, many Anglo-Saxon poets agreed with the maxim ræd biþ nyttost—‘advice is the most useful thing.’

A version of this blog post first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “The first folio of the heroic epic poem Beowulf, written primarily in the West Saxon dialect of Old English” by the British Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Finding wisdom in Old English appeared first on OUPblog.

Our diet and the environment [infographic]

Our diets are a moral choice. We can decide what we want to eat, though more often than not we give little thought to our diet and instead rather habitually and instinctively eat foods that have been served to us since a young age. Of course, poverty and isolation can limit our accessibility to choose what we eat. However, as Lisa Kemmerer argues in her book, Eating Earth: Environmental Ethics and Dietary Choice, those individuals who are affluent enough to make conscious decisions about their diets should think twice about the environmental ramifications of their dietary choices—because these ramifications can be drastic.

Download a JPEG or PDF version of the infographic.

Feature Image Credit: CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Our diet and the environment [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Shakespeare’s work: pure genius or imitatio?

William Shakespeare was undoubtedly a literary mastermind, yet several allusions and quotations in his works suggest that he gathered ideas from other texts. Ovid’s Metamorphoses, for example, was alluded to more than any other classical text, and the Bishop’s and Geneva Bibles were quoted numerous times in his works. Shakespeare’s reliance on source material from external literature was a common practice of the time period. He would have learned this habit of absorbing and imitating other texts (imitatio) in grammar school and from classics that were translated into English. The following is a collection of sources that appear to have influenced several of Shakespeare’s works, such as Coriolanus, As You Like It, and Antony and Cleopatra.

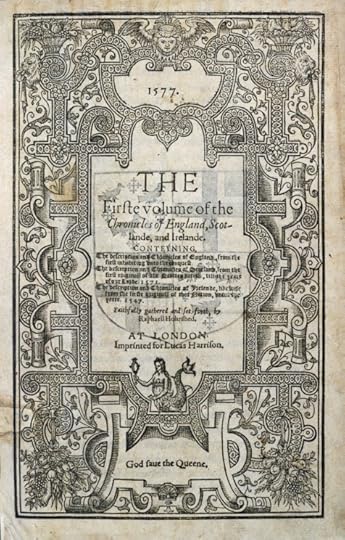

Raphael Holinshed, Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande (1577)

Holinshed’s ‘Chronicle’ was the single most important source for Shakespeare’s history plays. It was used as a source for his historical play, ‘Henry VI, Part 2′.

Image: “Raphael Holinshed. Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande. 1577″ by Susan Gibson. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Folger Shakespeare Library

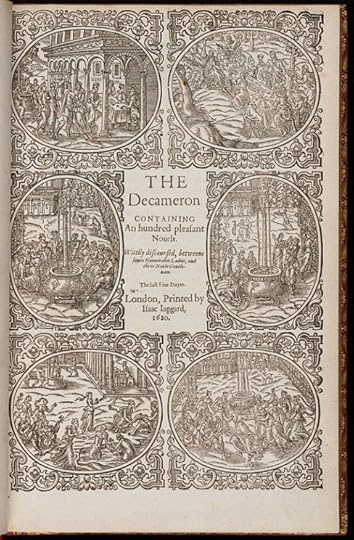

Giovanni Boccaccio, The decameron containing an hundred pleasant nouels (1620)

Shakespeare learned the habit of ‘imitatio’, or imitation, in grammar school as he studied the classics. In particular, one of the top three plot sources for his plays was Giovanni Boccaccio’s ‘The Decameron’.

Image: “Title page The Decameron printed by Isaac Iaggard London 1620″ by Isaac Iaggard. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

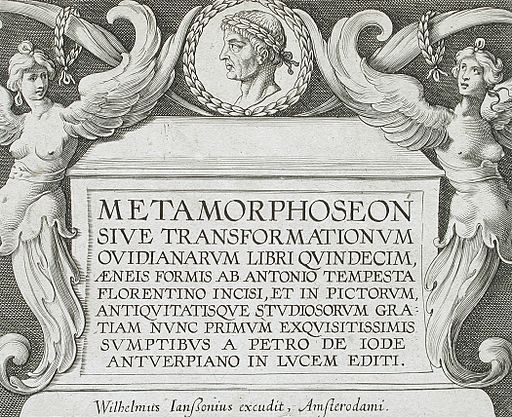

Ovid, Metamorphoses (1606)

Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ was a strong classical influence on Shakespeare’s work, particularly his sonnets. He included more allusions to “Metamorphoses” than any other classical text.

Image: “Frontispiece with the Bust of Ovid” by Antonio Tempesta and Wilhelm Janson. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

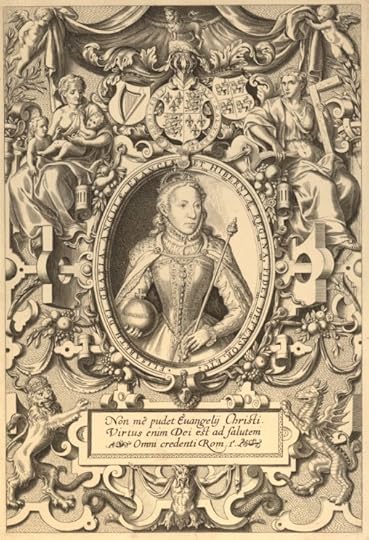

The Bishop's Bible (1568)

Despite his use of The Bishop’s Bible in his earlier plays, Shakespeare later switched to the Geneva Bible.

Image: “Elizabeth I Frontispiece Bishops Bible 1568″ by Franz Hogenberg. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Geneva Bible (1560)

Aside from classical source material, Shakespeare also incorporated scriptural quotations and allusions from the Geneva Bible.

Image: “Geneva Bible” by Aurevilly. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

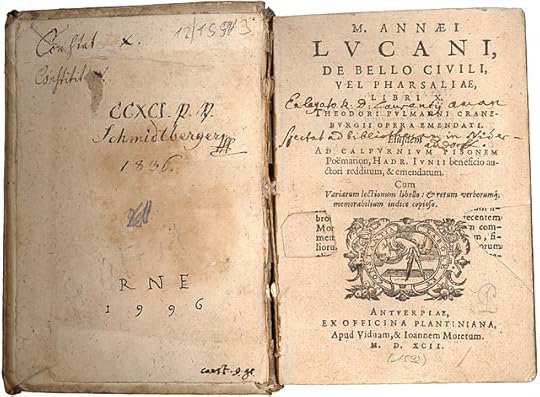

Lucan, Pharsalia or the civill warres of Rome (1592)

Once classical texts were translated into English, Shakespeare continued his use of ‘imitatio’. Lucan’s ‘Pharsalia’ appears to be a direct source for the tragedy, ‘Antony and Cleopatra’.

Image: “Lucanus, De bello civili ed. Pulmann (Plantin 1592), title page” by Aristeas. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

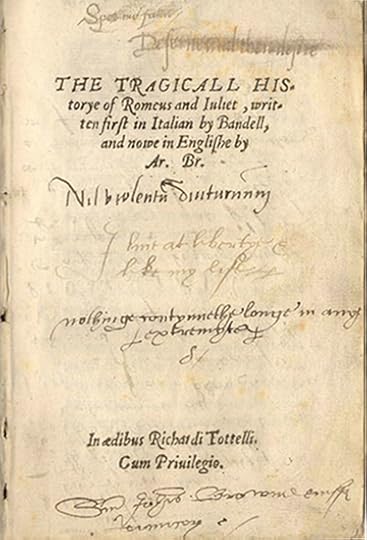

Arthur Brook, The tragicall historie of Romeus and Iuliet (1587)

The relationship between these two texts, Brooke’s and Shakespeare’s, is apparent through the similar title. Brooke’s publication, which was originally a translation of an Italian story, was an incredible influence on the Shakespearean tragedy we know today.

Image: “Arthur Brooke Tragicall His” by Arthur Brooke. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Featured Image: “Globe Theater Innenraum” by Tohma. CC BY-SA via Wikimedia Commons

The post Shakespeare’s work: pure genius or imitatio? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers