Oxford University Press's Blog, page 615

September 19, 2015

Getting to know Anna Hernandez-French, Assistant Editor in Journals

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into our offices around the globe. This week, we are excited to bring you an interview with Anna Hernandez-French, an Assistant Editor in Scientific and Medical Journals. Anna has been working at the Oxford University Press since September 2012.

When did you start working at OUP?

10 September 2012, so I just passed my three-year anniversary.

What drew you to work for OUP in the first place? What do you think about that now?

I attended the Columbia Publishing Course in 2009 and left with a sense that I was more suited to academic publishing than trade. I admire OUP’s mission—supporting excellence in research, scholarship, and education—and I get a great sense of fulfillment from the small part I play in supporting these goals. What I have found I also enjoy, however, is the day-to-day business aspects of my job. It’s great to build relationships and work one-on-one with some of the best minds in the academic community, and I end up learning a lot of about a number of subjects I might otherwise encounter very little. As an English major, working with scientific and medical journals has been fascinating and definitely expanded my knowledge and interests.

What publication do you read regularly to stay up to date on industry news?

The publication I read most regularly is the Scholarly Kitchen blog, which features posts on key journals publishing topics from a variety of viewpoints (Editors, Librarians, Service Providers, etc.) within the industry and the larger academic community.

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

About half an hour after I get into the office in the morning, once I’ve sorted through my inbox and laid out the day’s to-do list. It’s very satisfying.

What’s the least enjoyable part of your day?

The inevitable and constant rearranging and postponing of items on my to-do list as other, more urgent things arise.

Photo of Anna Hernandez-French. Used with permission.

Photo of Anna Hernandez-French. Used with permission.What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

A purple nerf gun I got at the team’s 2014 Christmas Yankee Swap. It shoots secret messages in foam capsuls, so it’s obviously a very handy item to have around the office. It was a very sought-after item among my teammates.

What was your first job in publishing?

I interned in the Academic/Trade books division before taking on a permanent role in Journals Editorial.

What’s your favorite book?

This is always a tough one. I have a long list of much-loved books, some of which I reread periodically (and all of which I try to own in print), but I usually come back to Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment as my absolute top favorite.

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

I have a catch-up call with one of my journal’s Production Editors, another call with another journal’s Editor-in-Chief, and then I will be reviewing and following up on logistical details for our team’s Fall conference, Oxford Journals Day, which I am organizing this year.

What is your most obscure talent or hobby?

I like to make handmade cards for birthdays and holidays, collage-style. When I was growing up, my siblings and I were expected to make handmade thank you cards for our friends and relatives who sent us Christmas presents. I found I was much better at cutting and gluing paper than I was at drawing.

What is the longest book you’ve ever read?

I think that would have to be The Wandering Jew, at 887 pages, according to the internet (my copy, which I don’t have on hand, seemed longer). I’ve not yet attempted War and Peace.

What one resource would you recommend to someone trying to get into publishing?

I’ve found that the most important and enduring resource for me has been personal connections within the industry. Whether it be through your alumni network, an internship, or one of the publishing courses like the Columbia Publishing Course that I attended, making contacts in the industry is key not only to landing your first job, but also providing you with a network that will aid and support you throughout your career.

Image Credit: Photo by Kate Donaldson. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Getting to know Anna Hernandez-French, Assistant Editor in Journals appeared first on OUPblog.

Who was Giles Cory?

“Monday, Sept. 19, 1692. About noon, at Salem, Giles Cory was press’d to death for standing Mute; much pains was used with him two days, one after another, by the Court and Capt. Gardner of Nantucket who had been of his acquaintance: but all in vain.” Thus reads Judge Samuel Sewall’s terse account of one of the most gruesome incidents in early American history, one that continues to horrify yet fascinate. Who was Giles Cory? Why was he accused of witchcraft? And how did he come to such a horrible fate?

Giles Cory was a prosperous farmer who lived in the part of Salem Village that is in present-day Peabody, Massachusetts. In 1685, the elderly twice-widowed Giles married Martha Pennoyer Rich, a widow who was about 9 years his junior. In April 1692, both Martha and Giles were arrested for suspicion of witchcraft. During the Salem witchcraft outbreak very few church members were accused –that is Puritan saints who believed that God had spoken to them and promised them salvation. Yet the Corys were both church members, and ironically, it seems likely that their membership may have led to their accusation.

Prior to her first marriage, Martha Cory had given birth to a bastard mulatto son, who now lived in the Cory household. This checkered past must have raised eyebrows if not objections when she applied to become a member of the Salem Village church on April 27, 1690. Unlike Salem Town and other congregations who had relaxed the church membership process and also accepted the Halfway Covenant, Reverend Samuel Parris and his Salem Village church maintained the traditional high standard. An applicant for church membership had to stand before the congregation and publicly confess their sins, and provide a testimony of their personal religious experience. It was a daunting task, even for the most devout. Yet, Martha Cory was up to the task, and was proud of her status. When later questioned for witchcraft, she proclaimed “I am an innocent person: I never had to do with Witchcraft since I was born. I am a Gospel Woman.”

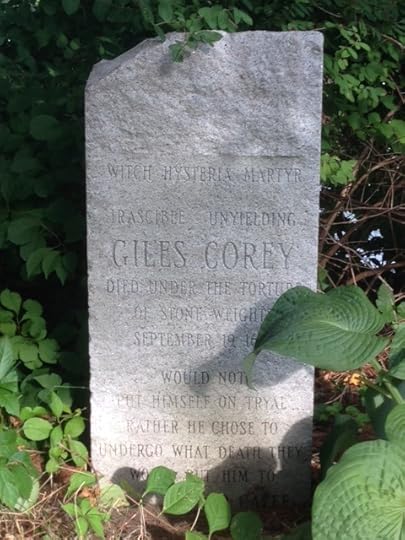

This modern memorial stone stands next to Martha Cory, on property they once owned in what is now Peabody, Massachusetts. The actual burial site of the Corys is unknown. Photo by Emerson W. Baker

This modern memorial stone stands next to Martha Cory, on property they once owned in what is now Peabody, Massachusetts. The actual burial site of the Corys is unknown. Photo by Emerson W. BakerMartha wanted her husband Giles to join her as a church member. In seventeenth-century New England, everyone went to the meetinghouse to attend worship. A church was not a building, rather the term referred to the core group of the congregation who were “saints” accepted into full church membership, with eligibility to receive the sacraments of communion, as well as baptism for their children. Once Reverend Samuel Parris was ordained in 1689, Salem Village formed a church and began to accept members, including Martha Corey.

Why then, did her husband Giles become a member of the neighboring church in Salem Town, on April 26, 1691? A meetinghouse two and a half miles further away from home than Salem Village, where his wife was a member in Salem Village? The most likely answer is that Giles knew could not meet the strict requirements of Salem Village, so instead applied at the Salem Town church.

With the active encouragement of its minister, John Higginson, in 1666 Salem Town church changed their requirements for membership from public confession to the candidate’s good behavior for a month, along with a private confession of faith to the minister. The first person to be accepted under these new rules was Bartholomew Gedney. He would soon be joined by John Hathorn and Jonathan Corwin. All three would be judges of the Court of Oyer and Terminer that conducted the witch trials in 1692.

Presumably Giles had to seek this less strict church because of his checkered past. His admission to the Salem Town church even noted that he had “been a scandalous person in his former time, but Got having in his later time awakened him into Repentence.” Now, however, this once “scandalous person” had beaten the system. Not pure enough to become a Salem Village saint, his membership in the Salem Town church still gave him the right to receive communion at Salem Village. Surely some devout Salem Villagers must have felt their church was defiled to have the Corys present at the Lord’s Supper. It is not surprising they were early targets of accusation in 1692.

Although Giles may have reformed, people still remembered his scandalous behavior in the 1670s, when his neighbor John Proctor accused Giles of setting fire to Proctor’s house, and another man accused Cory of tearing down his fence and stealing wood, hay, and carpentry tools. Worse, in a fit of anger Giles Cory used a stick to severely beat his hired hand Jacob Goodell, an act which led to the man’s death several days later. The court fined Cory though some thought he had gotten away with murder.

In 1692 one of the afflicted said “Giles Cory or his apparition” beat them, and Mary Warren specified that Cory hit her with his staff. While Giles was being pressed to death, Thomas Putnam Jr. wrote to Judge Samuel Sewall to inform him of the well-remembered death of Goodell. Interestingly, Deodat Lawson noted that “an Ancient Woman, named Goodall,” was among the large group of women who claimed to be afflicted by Martha Cory. Was this Jacob’s mother or aunt striking back at the Corys for their mistreatment?

We now know who Giles Cory was and why people might accuse him of witchcraft. This man had a scandalous and violent past. He had gained a bad reputation as well as enemies. Some Salem Village Puritan saints must have felt that this underserving sinner had beaten the system, and they were reminded of it every time Giles sat among them to receive communion. Surely he was a symbol of Satan’s attack on the Salem Village church.

Feature Image: Photo courtesy of Emerson W. Baker.

The post Who was Giles Cory? appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about fool’s gold? [quiz]

Many people have heard of Pyrite, most-commonly referred to as fool’s gold, but far less people know about pyrite’s cultural significance or its prevalence throughout history. From American mining lore to Greek philosophy and medieval poetry, pyrite appears throughout our past, and continues to influence our lives today. Take this quiz to find out how much you know about fool’s gold, or perhaps discover how much more you have yet to learn.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Feature Image: Pyrite by James St. John, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How much do you know about fool’s gold? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Shakespeare and film around the world

From the birth of film, Shakespeare’s plays have been a constant source of inspiration for many screenwriters, directors, and producers. As a result, hundreds of film and television adaptations have been made, each featuring either a Shakespearean plot, theme, character, or all three.

Although the most frequently-produced and well-known adaptations are filmed and directed in the United Kingdom and the United States, Shakespeare’s work has traveled all around the world. From Mexico to Australia, Tibet to Russia, and Italy to Japan, Shakespeare has been translated into many languages and adapted onto screens in many ways. Take a look at these various films from around the world, all of which provide unique insight into their individual cultures by their respective filmmakers.

Featured Image: Hollywood Playhouse presents “Will Shakespeare” by Clemence Dane. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Shakespeare and film around the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Religious belief: A natural phenomenon with natural causes

Suppose the government runs random screening for a very rare mutation – Mutation X – present in 1 in every million. The test is 99% accurate. If your result is positive, does this mean that you probably have Mutation X?

No. Imagine that there are 100 million people, of which 100 are X-carriers and 99,999,900 are not. On average, 99% of the X-carriers, that is 99 people, will test positive. But 1% of non-carriers, that is 999,999 people, will also test positive. So you know that you are in one of these groups, but not which. In fact, you should be about 10,000 times more confident of being in the non-carrier group, because there are 10,000 times more people in it. You should be practically certain that the test is wrong.

This is a secular, quantitative, and imaginary application of the simple and devastating critique of religion that we find in David Hume’s great 1748 essay ‘Of Miracles’. Hume’s main point is that ‘no testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous than the fact, which it endeavours to establish’.

Its real secular applications are widespread. If a reliable journal reports an experiment that violates well-established physical laws, or if a senior politician quotes a surprising statistic, or if an intelligent person of general good sense testifies that homeopathy cured her gallstones – in all such cases and in innumerable others, always ask yourself: what is more likely? Is it (a) that the experiment/politician/person was involved in some error or fraud, or (b) that the thing it reports is actually true? And usually (a) wins by a mile. The general lesson: if a reliable witness reports something amazing – don’t believe it.

Turn now to religion. In our time, as in Hume’s, billions of people all over the world derive their moral framework, attitude towards life, and conduct towards others from belief in a supernatural entity and the miraculous achievements of its terrestrial agents: Moses, Mohammed, or Jesus. The evidence on which they base these life-changing (and in extremis, for others if not themselves, life-ending) beliefs derives entirely from (scriptural) testimony. How much support does that testimony really give those beliefs?

Image: Statue of David Hume, Edinburgh, by TwoWings. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image: Statue of David Hume, Edinburgh, by TwoWings. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Practically none, said Hume, because which is more likely: that the Red Sea should – magically – part just long enough for the escape of an enslaved people, or only that they should preserve such a myth? That an angel visited an Arab businessman in a cave, or only that half the world should be deceived into believing this? ‘That the whole natural order be suspended, or that a Jewish minx should tell a lie?’ (This was Christopher Hitchens’s question about the virgin birth; but I think Hume would have enjoyed both its irreverence and its specific mockery of the ‘Roman superstition’.) The questions practically answer themselves, and the answers undermine all of the evidence that anyone in modern times has ever had for the central claims of Judaism, Islam or Christianity. Hume concludes with venomous irony that ‘the Christian Religion not only was at first attended with miracles, but even at this day cannot be believed by any reasonable person without one.’

But in truth, and as Hume knew, religious belief is no miracle but a natural phenomenon with natural causes. Hume was supreme amongst philosophers in balancing an acute sensitivity to the demands of rationality with a clear-eyed appreciation of the infirmities that make everyone fall short of them. The consequent tension is the central theme of his greatest work, Book I of the Treatise of Human Nature (from which he omitted ‘Of Miracles’ in face of the real dangers then attending public atheism). His Natural History of Religion documents the operation, over history and prehistory, of those infirmities that in his view begot modern monotheism. Driven by fear, we impute agency to natural processes around us – this leads to polytheism. Driven by servility, we compete to attribute extreme and flattering qualities to these fictional agents, until (as he wrote): ‘a limited deity, who at first is supposed only the immediate author of the particular goods and ills in life, should in the end be represented as sovereign maker and modifier of the universe’. Fear and servility: these sources of religion may in barbarous times have seemed, and have often really been, conducive to survival, but they never had much to do with truth.

But neither are they irresistible. In 1784, Immanuel Kant wrote that ‘Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s own understanding without another’s guidance […] “Have the courage to use your own understanding” is therefore the motto of the Enlightenment.’ Hume’s point about miracles is a specific application of Kant’s principle: if somebody – anybody – speaks of miracles, don’t just believe it. Always weigh for yourself how likely it is that these things happened, against the speaker’s tendency to error and his interest in getting you to believe. That is quite important enough, but it hardly exhausts the value of Kant’s message. Skepticism of grand claims and distrust of authority remain our best safeguards, not only against superstition, but also against mass hysteria and many modern forms of social and state-imposed tyranny.

Headline image credit: ,Annunciation (Annunciazione)’, by Sandro Botticelli. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Religious belief: A natural phenomenon with natural causes appeared first on OUPblog.

September 18, 2015

Bringing the Digital Humanities into the classroom

As a leader in oral history and digital humanities, Doug Boyd always gives his time to preach the gospel of the intersection of the two, particularly using OHMS as a conduit to bring the two of them together effectively. We at the OUPblog always appreciate the time he gives us to speak to or write about his work. Chime into the discussion in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+. If you’d like to discuss an innovative project you’re working on, consider submitting it for publication on this blog. — Andrew Shaffer

I spent four days last month with my colleague and friend, Doug Boyd, as he and I (mainly he) gave oral history workshops in Milwaukee and Madison. While the idea to bring Boyd to Wisconsin for these trainings began with Ann Hanlon, Digital Humanities Lab head at UW-Milwaukee, I jumped at the chance to find groups to sponsor his time in Madison. I knew it would give attendees (and me) an opportunity to pick his brain about oral history, digital humanities, and his latest creation, the Oral History Metadata Synchronizer (OHMS).

It would also give Andrew and I a chance to promote Boyd’s new article, co-written with Janice W. Fernheimer, and Rachel Dixon, titled “Indexing as Engaging Oral History Research: Using OHMS to ‘Compose History’ in the Writing Classroom.” For those unfamiliar with OHMS, Boyd has talked about it in an OUPblog podcast, and also maintains a website and blog on the topic. Here are some excerpts of our chat.

Doug, why bring OHMS into the classroom?

It was not my original intention when I created OHMS to have students in the classroom working on the back-end. But once the Nunn Center began to increase our indexing efforts, we began to learn a great deal about indexing that shaped policies and workflow. Most of all, I saw the student workers really engaging with oral history in a new way. I originally tested the concept of using students in a classroom setting with a graduate Library Science course that I was teaching. OHMS provided the class with an engaging opportunity to learn something completely new about metadata, and incorporate a digital humanities element into the course. At the time we did not have very well developed tutorials for OHMS, so I was not expecting much in term of the outcome. That said, I was blown away when the interview indexes were turned in. The quality of the index was outstanding. I had the students write reflective papers on the process and got some really great feedback—they loved the opportunity to contribute to what the Nunn Center was doing and loved working with OHMS. The project provided a real opportunity to enhance the quality of pedagogy—to connect the classroom more directly to the archive. When UK Professor Jan Fernheimer and I connected, I was eager to put OHMS to the test in an undergraduate classroom. As the article suggests, the experiment was an incredible success.

Why did you feel it important to co-write the piece?

From the beginning we felt like we were creating a collaborative model, so there was no doubt when we began looking back at the experience that we needed all three voices present in the article. I have written a great deal about OHMS, but never from this perspective. What really made this successful was Professor Fernheimer’s course design and energy. She was willing to experiment and was flexible enough to roll with variables that presented themselves during the semester. I think I can speak for Jan when I say that both of us were adamant that we needed student voices represented in this article—and not just in the form of quotations from their papers. Rachel Dixon’s perspective on being a student in that class is what makes this article so very powerful and the impact of OHMS as a pedagogical tool so real. I think there should be much more collaboration with regard to scholarship, especially integrating students into the process.

Have you brought OHMS into other classrooms? What were the results?

As a matter of fact, yes. Since the article was originally submitted, I used the experiences gleaned from working with Professor Fernheimer’s classes when presented with the opportunity to work with Charlie Hardy and Janneken Smucker at West Chester University this year. Charlie and Janneken were teaching a digital history course and wanted to utilize OHMS to present interviews Charlie conducted back in the 1980s that documented the First Great Migration North to Philadelphia (the interviews had been archived at the Nunn Center). By the end of the semester, the students had used OHMS and Omeka to produce the Goin’ North website that won the 2015 Oral History Association Award for Use of Oral History in a Non Print Format. I am so proud of this collaboration. It was largely built on the lessons learned from the original collaboration presented in our article and really takes the model of using OHMS as a pedagogical tool to the next level.

Image Credit: “Classroom” by Miki Yoshihita. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Bringing the Digital Humanities into the classroom appeared first on OUPblog.

10 ways hospitals can heal the planet

A healthy and sustainable environment is a necessary foundation for human health. On that most people agree. But there is an interesting paradox in health care: As hospitals deliver life-saving care to people, their environmental footprint — pollution, energy use, waste production, etc. — can be harmful to our health.

A growing segment of health care business and clinical leaders are addressing this glaring contradiction, and the medical community is taking an increasing vocal role in raising public awareness on the perils climate change poses to human health.

Here are 10 ways hospitals can heal the planet:

Advance a healthier economy. Hospitals are more than an important part of the community, their impact reaches across the globe. Health care generates about 17 percent of all U.S. economic output, making it large enough to create and lead a national, and even global, transformation that considers environmental sustainability in every dimension of economic activity. Eliminating mercury, minimizing incineration, creating demand for products that don’t contain harmful chemicals are successes led by U.S. hospitals that have had global impact.

Buy solar and wind energy. With around the clock operations and highly technical environments, hospitals are, let’s face it, energy hogs. Replacing fossil fuel with renewable energy sources like wind and solar is the single most impactful thing hospitals can do to mitigate against the effects of climate change on health.

Make every watt count. Reducing energy demand is as much a part of any good energy strategy as buying renewables. From low-cost to more substantial upfront investments, energy-reduction initiatives can have measurable impact on improving air quality and patient health, and reducing operating expenses.

91957046 by mattwalker69 CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

91957046 by mattwalker69 CC BY-SA 2.0 via FlickrBuild green. Studies increasingly show the benefits of green design on the environment, cost and staff retention. At Kaiser Permanente we have made it a policy to pursue a minimum of LEED gold certification for new construction of hospitals and other major construction projects. Our own experience has shown that when green design and construction principles are adopted early in the planning process, there is little to no added cost, and return on investment is almost immediate.

Support sustainable food systems. With their substantial purchasing power and focus on health, hospitals and health systems are in an ideal position to create change within the wider food system. By supporting local farms and producers and promoting healthy diets with reduced meat consumption, hospitals and health experts can encourage healthy food habits in the community and make over a tired industrial food system that until recently served up Jell-O and canned peaches as hospital food.

Reduce hospital waste. Hospitals in the U.S. generate some 7,000 tons of waste per day, or more than 2.3 million tons a year. By making smarter purchasing decisions upstream and recycling, reusing, and composting waste, hospitals can save money while diverting loads of waste from landfills and incinerators.

Detox. In the absence of effective public policies on chemicals of concern, the burden of absorbing the mounting knowledge of chemical toxicity in our environment and to respond to it can fall to doctors, nurses and others who work in health care. By adopting an institutional commitment to safer chemicals, tapping into resources to help understand more about potentially harmful chemicals and where they lurk, and flexing that special purchasing muscle, hospitals can help bring safer, better products to market. Vinyl-free latex-safe gloves, PVC-free carpets and flooring, DEHP-free IV tubes, and flame-retardant-free furniture are just a few examples of health care products that didn’t exist or were not widely available until health care purchasers worked with suppliers to develop them.

Studies increasingly show the benefits of green design on the environment, cost and staff retention

Collaborate. Hospitals are anchor members of their communities and communities play a major role in addressing many of our most pressing environmental concerns. By partnering with environmental groups, local governments, NGOs and other community organizations, we can build communities with healthy ecosystems that support human health, plants and animals.

Speak up about health and the environment. With a focus on prevention and proven clinical best-practices, doctors and public health experts are moving the dial on smoking, obesity, and some of our toughest lifestyle-related diseases. By applying our expertise in preventive medicine to climate change, we can influence global climate actions to address what many now consider our century’s greatest lifestyle disease for which we’re all at risk.

Focus on total health. Healthy populations and healthy communities depend on healthy environments. Greening hospitals is not about saving the planet. It is about being anchored in health because that’s the mission of hospitals and that’s where we have expertise and credibility. Hospitals have roles to play in supporting healthy communities beyond providing direct medical care. They can influence environmental health through grantmaking to environmental organizations, purchasing locally, supporting active transportation, and more. Improving the health of communities includes improving the health of the environment.

Featured image credit: Nasa Earth Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post 10 ways hospitals can heal the planet appeared first on OUPblog.

Incorporating sex as a biological variable in preclinical research

In the spring of 2015 the National Institutes of Health announced new guidelines for the incorporation of sex as a biological variable in any research they fund. Chromosome compliment (XX for female, XY for male in all mammals), gonadal phenotype, and gamete size define sex as a biological parameter. (In contrast, gender is a human construction based on an individual or society’s perception of sex.) A mandate for inclusion of women and minorities in clinical trials had been successfully established long ago, but the gender balance did not trickle down to studies on animals and cells, or indirect human research (preclinical research).

We spoke with Margaret M. McCarthy, PhD, author of “Incorporating Sex as a Variable in Preclinical Neuropsychiatric Research” in a recent issue of Schizophrenia Bulletin, about the issue of separating sex and gender, considering the biological parameter of sex, flawed studies, and future research findings.

Why is the NIH requiring consideration of sex as a biological variable in preclinical research?

Because sex matters. Several analyses of published articles in multiple fields of biomedical research have found that the overwhelming majority of studies on animal models either use exclusively males or don’t report the sex of the animals they are studying (which usually means males). Preclinical research is used to inform clinical trials and 8 out of the last 10 clinical trials that were halted early were due to adverse events in women, some of them life-threatening.

Did any of those clinical trials involve treatments for schizophrenia?

No, but it is well established that schizophrenia is a very different disease in men versus women. Jill Goldstein at Harvard has studied this extensively and notes that at younger ages males are more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia and have stronger negative symptoms and less depressive symptoms than women. At older ages the prevalence switches so that women are more likely to be diagnosed. There is a mix of evidence as to why there are these differences, suggesting we need more fundamental research on the topic, and that begins with animal models.

Why don’t most researchers study both males and females?

For several reasons. One is a long standing bias that females are more complicated than males because their hormones cycle over days, weeks, or months. There is also a view that the only sex differences between males and females are those directly associated with reproduction. And lastly, a lot of researchers just think males are the norm, after all the researcher is more likely to be a man than a woman due to the paucity of women in science.

How is the NIH going to fix redress this imbalance?

By requiring that all research funded by them and that involves either animals or cells must both report the sex of the subjects and must analyze for the effects of sex on the endpoints they are measuring. This means that scientists must no longer use exclusively males, they must mix males and females in their groups and conduct a statistical analyses that determines if there is a difference. The NIH hopes to assure this becomes a routine component of research by including it as what is called a “review criteria,” meaning when a grant is peer-reviewed to determine if it is suitable for funding (only ~10-20% of grant proposals are awarded funding), the degree to which sex as a biological variable has been effectively incorporated into the experimental design will be assessed. This does not mean that everyone has to start studying sex differences. Indeed, if the researcher finds there is no difference in the response of males and females they can now include both sexes in all of their research going forward, which saves a lot of animals from going to waste. (Think about what happened to all those female littermates in the past).

Why is the NIH facing such resistance to this new requirement?

Because change is hard. Some believe they are going to have to double or even quadruple the number of animals they use (not true), so they can control for the estrus cycle (even more not true), and that this will cost a fortune but nobody is giving them any more money. Some are also sure, without any evidence, that whatever they are studying will not differ between males and females. They might be right, and so they only need to demonstrate that definitively once, and then they can move on using males and females in their research with confidence that there is no greater variability introduced by including females. Their sample size can remain exactly as it always has. Indeed their variability might even go down as it has been found that group housed male mice and rats form a dominance hierarchy which greatly impacts the physiology of the dominant and subordinate animals in very different ways. So in the end, males may be introducing just as much variability into a study, or even more, than females with all their pesky hormones ever do.

How will we know if it worked?

A few of ways. One result will be that the same types of analyses of published research that reveals the huge discrepancy in representation of females in animal and cell tissue studies can be repeated in five years and verify that the imbalance has been corrected. If it’s not, that means that the peer-review process is failing and the evaluation of sex as a biological variable has not been properly done. Second, no clinical trials would be started unless the preclinical findings were thoroughly vetted for males and females. Third, we should begin to see sex-specific treatments or dosing regimes approved by the FDA. This has already begun with the recommendation for lower doses of Ambien for woman, but unfortunately this was only after adverse events had occurred. The goal is to prevent or reduce this type of post-hoc modification going forward.

Featured Image: Lab rat. (c) JanPietruszka via iStock.

The post Incorporating sex as a biological variable in preclinical research appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about pilgrimages?

Pilgrimage has been celebrated in literature from The Canterbury Tales to Paulo Coelho’s The Pilgrimage. Pilgrims in funny hats and buckled shoes play an outsized role in the American national mythos, but pilgrimage traditions encompass much more than the Puritans. From medieval Japan, where the first pilgrimage package tours were offered, to modern-day Mecca, which welcomes 30 million pilgrims for the annual hajj, to Africa, Latin America, and beyond, pilgrimage is a global phenomenon.

Test your knowledge of pilgrimages throughout history, across religions, and around the world.

Quiz image credit: Pilgrimage Church, by ADD. Public domain via Pixabay.

Headline image credit: Kataragama, female devotees. Photo by Arian Zwegers. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post How much do you know about pilgrimages? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 17, 2015

Celebrating five years of Oxford Bibliographies

The librarians at Bates College first became interested in Oxford Bibliographies a little over five years ago. We believed there was great promise for a new resource OUP was developing, in which scholars around the world would be contributing their expertise by selecting citations, commenting on them, and placing them in context for end users. It would be an innovative approach for finding authoritative and trusted sources, and one that was likely to work well in an online environment.

In the summer of 2010, our research librarians agreed that they would really like to see how we might make use of Oxford Bibliographies at our undergraduate liberal arts institution. OUP also wished to work with libraries and their end users to make sure that needs for ongoing use would be met.

Along with other libraries, we were able to offer our ideas in the early months when a core list of subject modules was already in place, with additional ones being worked on in the wings. Librarians, students, and faculty from various departments—such as classical and medieval studies, philosophy and religious studies, history, and sociology—responded to very comprehensive questionnaires and interviews that I believe were engaging for all. In truth, we still benefit from that engagement as we continue to think about where and how to improve access and use, such as initiating an informal faculty conversation this fall. At that time, we were able to offer opinions about the presentation of the resource as a database site, suggest potential new functionality, including increased linking, citations, and associated notes, and give advice about bibliographic records and other means of discovery. Some suggested possible new modules that would be of interest as well.

The platform and resource itself evolved rapidly. The number of subjects covered is now is very broad, ranging from African Studies to Victorian Literature.

Why has this resource worked for our college? There are so many reasons, but above all, these particular online bibliographies essentially help us accomplish what we try to do for our students and faculty all the time.

We are always striving to keep our collections relevant and reliable with resources that can quickly help introduce students to topics they need for their study and research. We usually only have a small amount of time with them at our research desk or in bibliographic instruction classes to teach them the basics. Wanting to make sure that our time is as valuable and efficiently used as possible, we often recommend this particular resource. We know they will find Google and large databases—as well as citations—from our vast discovery system, but getting to the heart of a new topic is key.

Our ability to recommend a resource that students can go back to when they have gone to their study places is reassuring for them—and for us. At first, they may just need an overview on a topic, but the next step of their journey may require knowledge of journals in the field, primary sources, films, or even knowledge of the best data sets available. Oxford Bibliographies provides a discovery system unlike ones that merely bring all our resources together. Instead, it is backed by evident mastery of a field of study constructed in a coherent framework, and may even seem to have a personal quality about them. (This is not to say that we don’t also feature the Bibliographies effectively in our large discovery system.)

Getting an overview of a topic will not only ground a young researcher, but will help orient a faculty member to an unfamiliar topic. Thus, the expert is aided as much as the novice. Faculty members can use it to develop bibliographies of their own for a class, or a librarian may find that he or she has missed getting an important title for the library’s collection. Several faculty members have said that they routinely direct their seminar or thesis students to make use of Oxford Bibliographies, which, as part of their structure, will also list related articles on a given topic. If, for example, you are reading about Buddhist Art and Architecture on the “Silk Road,” you will find that you can seamlessly move to articles—or module topics—on Buddhist art and architecture in Japan or Mongolia. This is yet another form of discovery and one that is truly exciting for anyone.

As we move toward an era of online research, we continue to find grounding in scholarship that we can rely on, particularly when it comes to avoiding overwhelming amounts of information. The schedule for new topics that will be added to Oxford Bibliographies is ambitious and even exhilarating. Since libraries have such an array of resources, however, we need to pay attention to the details. We still need to place our links carefully in resource guides, and we need to ask discovery providers to get the best metadata possible from publishers. Most importantly, however, we need to continue to work closely with our faculty and students to make sure they know what we have and how we can help.

Image Credit: “Mary Idema Pew Library Learning and Information Commons (Grand Valley State University, August 10-12, 2015)” by Corey Seeman. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Celebrating five years of Oxford Bibliographies appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers