Oxford University Press's Blog, page 585

November 21, 2015

To Savor Gotham: book launch

Food lovers with a soft spot for New York City gastronomy congregated on Tuesday, 17 November, to celebrate the upcoming book Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover’s Companion to New York City, edited by Andrew F. Smith. The bright, colorful cover parallels the diversity and richness of what it’s like to eat in the Big Apple; with nearly 570 A-Z entries on the history of NYC food and drink, we could hardly wait to dig right in to the book. And what better way to launch a book on New York City food and drink by savoring Gotham’s food and drink? We take a look at the highlights of the night.

Savoring Gotham, all lined up in a row.

Beer generously provided by Brooklyn Brewery.

(left to right) Max Sinsheimer (OUP editor), Niko Pfund (OUP President), Garrett Oliver (contributor & author of foreword)

Editor-in-Chief Andrew F. Smith signing copies of Savoring Gotham.

Photos taken by Jonathan Kroberger for Oxford University Press.

The post To Savor Gotham: book launch appeared first on OUPblog.

Thinking the worst: an inglorious survival posture for Israel

Sometimes, especially in humankind’s most urgent matters of life and death, truth may emerge through paradox. In this connection, one may usefully recall the illuminating work of Jorge Luis Borges. In one of his most ingenious parables, the often mystical Argentine writer, who once wished openly that he had been born a Jew, examines the bewildering calculations of a condemned man.

Approaching desperation, this unfortunate soul, upon suddenly remembering that expectations rarely coincide with reality, intentionally imagines and re-imagines the circumstances of his own impending death. By completing this process, the doomed prisoner’s final reasoning quickly becomes quite simple. Because these circumstances have already become expectations, he calculates, death (at least for the present) will have to find someone else. For now, at least, his own mortality can be gratefully pushed aside. By thinking the worst, he will actually be saved.

With this complex lesson, Borges illustrates, by deploying both indirection and inference, the unanticipated benefits of deliberately “negative” thought. Oddly, perhaps, but not incorrectly, he leads us to understand, in certain life-threatening contexts, that actively imagining worst-case outcomes can be life-extending. Although starkly counter-intuitive, such easily discarded forms of understanding can still have unanticipated strategic benefits.

Understandably, in the Middle East today, Israel – arguably, the ill-fated individual Jew writ large – refuses to typify the enthusiastically trembling character of Borges. To be sure, especially as it now faces the latest onslaught of barbarous Palestinian terror, Israel should not assume (1) a deliberately unheroic or fearful posture in world politics; or (2) that it has already been “condemned to death.” But there is more.

Israel does face genuine existential perils. These perils are not “merely” the readily visible threat from a steadily nuclearizing Iran, and/or the dangers from expanding terrorism. They are also the result of distinctly tangible interactions, or synergies, between several seemingly separate dangers.

More precisely, considered in more narrowly military parlance, and over time, the combined effect of escalating rocket attacks from Gaza or Lebanon, and Iranian nuclearization, could create a negative “force multiplier.” Left unimpeded, Israel’s resultant “cascade of synergies” (that is, its utterly core vulnerabilities) could then bring the Jewish State face-to-face with potentially unprecedented harms. Soon, this portent could become even more ominous in the midst of steadily growing regional and global chaos, including what assorted Palestinian murderers and their supporters now crudely attempt to sanitize as a “Third Intifada.”

Under authoritative international law, the deliberate killing and wounding of noncombatants is never “freedom fighting.” Never. In pertinent law, this behavior is incontestably murder. Nothing more.

For nation-states, as for individuals, fear and reality can go together naturally. With such an apparently odd fusion in “mind,” Israel should soon begin to imagine itself, assertively, but also as the ingathered post-Holocaust Jewish community, as entirely mortal – as mortal, in essence, as any individual human being. Then, and perhaps only then, Israel’s leaders could more effectively implement the specific political and military policies needed to effectively secure their beleaguered state from further terrorist escalations, and, ultimately, from prospectively irreversible capitulations.

At first, this cheerless advice may resonate as very strange counsel. After all, one would normally insist, death fear, by definition, any death fear, is corrosive and even cowardly. Why, then, should Israel embrace cowering weakness as a deliberate national policy?

There is a good answer, but it will require an antecedent willingness to think seriously. Sometimes, truth may emerge through irony and paradox. Plainly, no sane analyst would ever suggest any encouragement of Israeli weakness or cowardice as policy.

Still, certain reassuring intimations of a collective immortality, that is, hints routinely encouraged by a fawning policy architecture of contrived hopes and false dawns, could unwittingly discourage Israel from taking needed steps toward a durable safety. On the other hand, admitting that the state, just like the many discrete individuals who comprise it, could actually disappear, might set the stage for a more disciplined and possibly indispensable sort of national strategic thinking.

In world politics, certain national expectations are pretty much universal. As with most of its enemies, Israel conveniently imagines for itself, a national life everlasting. And why not? After all, unlike the country’s many lascivious foes, both external and internal, Israel does not see its path toward immortality, either individual or collective, via the “sacred” murder of “unbelievers.” Instead of war and terror, which still remain the unambiguously preferred Arab/Islamic way of interacting with despised “others,” Jerusalem sees Jewish country survival as the end product of several vital and more-or-less overlapping factors. These factors include (but here, in no particular order of preference), divine protection; well-reasoned diplomatic settlements; and/or prudent military planning.

Singly or collectively, there is nothing inherently wrong with harboring a collective faith in such particular sources of national and personal safety. Still, even this faith ought never be allowed to displace a prior and primary awareness of conceivable national impermanence. Like Borges’ condemned man, Israel, going forward, would do better to recall the potentially considerable benefits of “imagining the worst.” In the absence of such a painful and difficult recollection, Israeli strategic planners could easily overlook certain distinctly vital and irreplaceable requirements of national survival.

In every recognizable way, Israel remains different from its multiple adversaries. An evident asymmetry of purpose may place the Jewish State at a moral and legal advantage, but also, at the same time, at a detectable strategic disadvantage. While Israel’s enemies, especially Iran, manifest some of their own “positive” hopes for immortality by openly contemplating the mass slaughter of Jews (religiously, the Jihadi nexus between these positive hopes, and ritualistic slaughter, is often codified, fixed, and compelling, for both Sunni and Shia elements), Israel’s leaders display their own country’s hopes for survival with periodical acquiescence to conspicuously relentless foes. These regrettable forms of futile surrender include the incremental and unreciprocated desertion of vital lands, and the too-frequent release of jailed Arab terrorists, also in equally unreciprocated gestures of Israeli “good will.”

In the end, Israel’s search for “good will” will prove to have been a distressingly vain, indecent, and too-costly display of largesse. Israel, after all, a country smaller than America’s Lake Michigan, remains the only state in world politics that is expressly singled out for theologically and doctrinally-based slaughter. Moreover, this existential predicament, undiminished by jurisprudential expectations of the 1948 Genocide Convention, is not likely to change anytime soon. Consider, in this regard, that U.S. President Barack Obama went ahead with the recent Vienna Pact on Iran, despite that Agreement’s express violation of both the 1968 Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), and the Genocide Convention.

There is a very important and corollary question to raise at this point. Israelis must finally inquire, after a notably brief and evidently fragile interlude of statehood: Shall a tragic Jewish wandering begin all over again? It is a terrible, but also unavoidable, query.

However unwittingly, by stubbornly denying its own collective mortality, Israel may effectively prepare to hand its sworn enemies master keys to the Promised Land.

Exeunt Omnes?

This cannot be allowed to happen. For Israel, part of the blame for past error must lie with its long-term and unquestioned acceptance of the sterile American security paradigm. Significantly, in spite of its persistent permutations, mutations, and still-ongoing re-configurations, the easily captivating American ethos of “positive thinking” has generally been flush with suffocating strategic error. By finally rejecting such a long-patronizing ethos, and by being spurred on, instead, by newly encouraged imaginations of national disaster, the People of Israel could begin to move toward a far more thoughtful and secure defense posture.

The alternative, that is, to proceed with a deceptively “positive” collective ethos, could prove much more injurious. Philosophically, of course, such continuance could also make a mockery of Borges’ deducible literary insights, and his most deeply hidden truths. Nonetheless, Israel ought not to be concerned with incurring any purely philosophical costs, and, to be sure, its leaders would never have any such apprehensions.

In the end, the plainly counter-intuitive argument for cultivated imaginations of disaster is not a plea for Israeli pessimism as such, but rather a purposefully “last call” for facing up to worst-case survival scenarios. Because such an ironic courage could represent the “hopeful” start of a more promisingly gainful national security posture for Israel, it ought never be dismissed out of hand. Not by any means.

L’chaim! (“To life”)

Featured image: Jorge Luis Borges, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Thinking the worst: an inglorious survival posture for Israel appeared first on OUPblog.

Time and tide (and mammoths)

In July 1867 the British historian Edward Augustus Freeman was in the thick of writing his epic History of the Norman Conquest. Ever a stickler for detail, he wrote to the geologist William Boyd Dawkins asking for help establishing where exactly in Pevensey soon-to-be King Harold disembarked in 1052. Drawing on his own experience of digging the area for fossils, Dawkins explained that the sea had reached further inland in 1052 than it had both before and after that point in time. “Your postscript suggests to me the most amazing picture,” Freeman wrote back: “Harold sailed over those trees, and I found mammoth remains under them.” The resulting sketch shows three layers: on top is Harold in his boat, below it the trees of Freeman’s own day, and below these, at the lowest level, two woolly mammoths (see illustration on right).

Freeman’s ‘amazing picture’ is not the sort of ground section familiar to archaeologists, where the present appears at the top and one travels further back in time the lower down one progresses. Instead present is sandwiched between pasts. Freeman’s relationships with Dawkins and other natural scientists, his close attention to geography as well as his unusual conception of chronological precedence, all formed part of Freeman’s lifelong mission to establish a ‘science of history,’ one that borrowed methodologies and theories from the natural sciences without reducing mankind to so many passive atoms subservient to ‘laws.’ A reviewer and public commentator renowned for his peppery put-downs of rivals such as J. A. Froude and Charles Kingsley, Freeman had little time for what he called ‘picturesque’ history, whether that was the hero-worshipping approach of Thomas Carlyle or T. B. Macaulay’s ‘Whiggish’ focus on the development of political institutions.

Image credit: Drawing by William Boyd Dawkins in a letter to Edward Augustus Freeman. PP Freeman/Dawkins/1/15. Used with permission from Jesus College, Oxford.

Image credit: Drawing by William Boyd Dawkins in a letter to Edward Augustus Freeman. PP Freeman/Dawkins/1/15. Used with permission from Jesus College, Oxford.Where Macaulay had proposed that all societies climb up a single ladder of civilization, Freeman saw a much more dynamic, quasi-cyclical process in which past and present, then and now mirrored and echoed each other. Freeman’s love of drawing analogies in his historical writing cause past and present to fold into and onto each other. In this grand historical pageant it can sometimes feel as if we are watching a small troupe of historical actors slipping in and out of different roles, appearing at one instant in a Saxon witenagemot, at another in a New England vestry meeting.

The greatest example of this disappearing-and-reappearing act is Freeman’s account of the Norman Conquest itself. Historians had seen this as the imposition of a feudal ‘Norman Yoke’ on sturdy Saxon shoulders. In Freeman’s hands this becomes conquest in reverse. The Saxons lose the battle (Freeman insists we refer to it, not as the Battle of Hastings, but as the Battle of Senlac), but win the war, as they strip the Normans of their ‘French polish’, exposing conqueror and conquered’s true unity, as fellow members of a great Teutonic race.

While Freeman delighted in such assimilations, it remained clear that in this process one race – the Teutonic one – is uniquely favoured with the power to assimilate other races, without itself being assimilated. Race, apparently, held the key to Britain’s future as well as her past, and Freeman’s vast output of journalism ensured that this key was regularly applied to current affairs, in obedience to Freeman’s most famous dictum, that “history is past politics, politics present history.” Freeman’s role defining the embryonic academic discipline of history left a lasting legacy, shaping (for good and ill) how Britons as well as Americans viewed their shared past. Sellar and Yeatman’s 1066 and All That (1930) shows Freeman’s model of history to have been in satirically rude health forty years after Freeman’s death in Alicante.

For us today, Freeman’s racialism is less comic, especially when dressed as ‘science.’ But there is no denying the ambition, scope and imaginative power of his historical vision, which he and his followers applied to the built environment, to constitutional theory and to party politics as well as to England’s medieval past. After Freeman, past and present would, in one sense, remain the same: interlocking with each other, with human society and with the landscape itself. But in another sense they would never be the same again.

Headline image credit: Exterior of the inner bailey of Pevensey Castle, East Sussex by Prioryman. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Time and tide (and mammoths) appeared first on OUPblog.

Going to the pictures with Shakespeare

Not so long ago, we ‘went to the pictures’ (or ‘the movies’) and now they tend to come to us. For many people, visiting a cinema to see films is no longer their principal means of access to the work of film-makers. But however we see them, it’s the seeing as much as the hearing of Shakespeare in this medium that counts. Or rather, it’s the interplay between the two.

Some Shakespeare films appeal directly to the kinship between cinema-going and the live theatre. Olivier’s Henry V (1944) begins in an Elizabethan theatre, involving both a historical period and the viewers’ sense of themselves as an audience — the effect doubly appropriate in a film made in wartime, asserting the values of communal spirit and shared emotions. His Hamlet (1948) begins with an overture – a device used for ‘event’ films since the advent of sound — and the image of theatrical paraphernalia, and although it moves beyond this frame, the architecture of its sets suggests on a magnified scale the kind of spaces created in the theatre with the adaptable steps, rostra, and archways of the ‘unit’ set common in the middle of the last century.

Liberation from the studio – the movement outdoors for Olivier’s Battle of Agincourt – is what marks Henry V as a particular kind of cinema, whilst Hamlet remains a handsome, elegiac but almost entirely indoors affair. That claustrophobia is an important element of Olivier’s psychology-centered interpretation of the play, where there is no Fortinbras and no political context, whereas in the Russian director Grigori Kozintsev’s 1964 Hamlet we see Elsinore in daylight, as a busy military and administrative machine in a landscape. This widens the scope of the play, supporting the view of a tragedy of a society and not simply of an individual and his associates.

This suggests one of the important advantages the film can have over the theatre. Not only can the camera bring us close into the faces of the actors, it can also show us with greater effect the world beyond and around them. Film-makers can use Shakespeare’s dialogue to great effect, but usually need relatively little of it.

The pictures we are shown in Shakespeare films can haunt our imagination; the delivery of the lines often has less impact. Think of the death of Washizu, the Macbeth figure in Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957), grimacing in dismay and agony as he is skewered by the arrows of his own men; or the relentless, mud-churning battle of Shrewsbury in Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight (1964); or the spectacular death-fall of Ian McKellen as the anti-hero of Richard Loncraine’s 1996 Richard III.

Charlton Heston as Antony, 1950. Photo by Chalmers Butterfield (via Sba2 at English Wikipedia). CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Charlton Heston as Antony, 1950. Photo by Chalmers Butterfield (via Sba2 at English Wikipedia). CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.Now try to identify a sound-byte from these films that has stayed with you. In the case of the Japanese film, it’s probably the eerie music and silence of the scene leading to the murder of the ‘Lord’ and the swishing sound of the kimono of Washizu’s wife as she goes to fetch the drugged sake from a closet. With Welles’s film, as with his others, it’s probably the sound of the actor-director’s voice as much as anything he actually says. In McKellen’s performance, it’s the incisiveness of that first soliloquy, though it is made memorable in cinematic terms by the novelty of being delivered partly from the stage of a ballroom and partly in a gents’ lavatory.

In each of these cases – and we could multiply them from many other films – the pictures live alongside the words, not simply when they illustrate an event (such as a battle or a storm) that cannot be presented as fully on stage, but more generally because these sights, welded to the spoken dialogue, are more often than not the main reason why we go to the pictures. But now turn the argument round; the pictures have to grow out of the words, and however few of them the script uses (usually no more than 25 or 30%), they are the ultimate source of vitality. In some cases, such as Olivier’s mesmerizing performance as Richard III in his 1955 film, it is the actor’s personal performance that gives them a centrality unusual in the cinema. Kenneth Branagh’s epic Hamlet, with its claim to present the whole of the text, has an extraordinary variety and clarity of interpretation through speech as well as imagery. In another mode, the versions of Much Ado About Nothing by Branagh (1993) and Joss Whedon (2013) achieve the intimate comedy of relationships that we find in the screwball comedies of the 1930s.

Moreover, the language animates many films that take off from Shakespeare but have no claim to deliver the play itself, such as Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho (the two parts of Henry IV), Tim Blake Nelson’s O (Othello), or even Gnomeo and Juliet (Shakespeare’s tragedy, the garden gnome version). The secret lies in that dynamic relationship between dialogue and image, and the effect of both in inspiring and giving vitality to that imaginative quality we can call the vision of a film.

The post Going to the pictures with Shakespeare appeared first on OUPblog.

The phosphene dreams of a young Christian soldier

On a blustery St. Martin’s Eve in 1619, a twenty-three year old French gentleman soldier in the service of Maximilian of Bavaria was billeted near Ulm, Germany. Having recently quit his military service under Maurice of Nassau, he was new to the Bavarian army and a stranger to the area. The weather and lack of associates motivated the youth to remain alone in his room for days at a time. It was a comfortable room, warmed against the bitter cold by a porcelain stove. One can imagine that such cozy solitude might provide occasion for the young man to reflect on his course in life. He had studied law at Poitiers and military science at Breda but had yet to decide on a career. Perhaps, he hoped for some guidance as he crawled under the covers for a warm winter’s nap. That young soldier was Rene Descartes and, as legend has it, guidance came on that fateful night of 10-11 November 1619 in the form of three dreams.

The first dream begins with Descartes walking along a road amongst terrifying shadows or phantoms. He was forced to walk to the left due to a feeling of feebleness in his right side. Descartes was ashamed of walking in this manner and tried to straighten up but was struck by a whirlwind that spun him around several times on his left foot. He then saw a college up ahead and began to walk toward it with the intention of entering the school’s chapel to pray. But, on his way, he passed an acquaintance without acknowledging him and turned back to greet him only to be pushed back by the blowing wind. At the same time, Descartes saw someone else at the center of the courtyard, who politely called his name and remarked that he wanted to find Monsieur N. so as to give him something, which Descartes imagined to be a melon from a foreign land.

In the second, Descartes heard a loud sound that he took to be thunder. The fright from the noise woke him. Upon opening his eyes, he saw sparks of fire from the stove glittering about the room, but dismissed them as nothing out of the ordinary, having remembered that he had had the experience before while awake.

The third dream finds Descartes at a table with a book on it. Upon closer examination he is pleased to discover that it is a dictionary or encyclopedia, for he believes it will help him in his studies. At the same time, he also finds a collection of poems, picks it up, and opens it to a random page to find the verse “What path in life should I pursue?” A man Descartes did not recognize then appeared and highly recommended a poem beginning with the line “It is, and it is not.” Descartes recognized this as the opening to a poem by Ausonius and looked for it in the poetry collection but to no avail. He then told the man that he knew of another poem by Ausonius with the first line “What path in life should I pursue?” The man asked to see it but, again, Descartes couldn’t find it. The encyclopedia disappeared during this time only to reappear a moment later at the end of the table but not as complete. Finally, the man and both books disappeared.

Descartes, in his Discourse on Method, famously refers to his time holed up in a stove-heated room as the time when he discovered his new method. It is also the setting of his later Meditations on First Philosophy. So, Descartes’ time at Ulm was clearly important to his personal and intellectual growth. However Descartes’ first biographer, Adrien Baillet, takes things a step further by suggesting that these dreams were the divine inspiration for this new method. Unfortunately, Descartes’ own account of these dreams is no longer extant, and so there is no way to confirm whether or not he believed this himself. However, a quick look at aspects of Baillet’s report of the dreamer’s reaction may prove insightful.

According to Baillet, Descartes understood the buffeting whirlwinds of the first dream as an evil spirit trying to compel him to do something. In the second dream Descartes interpreted the thunder as the Spirit of Truth (or the Holy Spirit) taking possession of him. Also recall that he witnessed the glittering sparks from the stove but then calmed himself with the memory of such things happening during waking life. Descartes took the third dream’s encyclopedia as representing all the knowledge of the sciences, while the poetry collection represented philosophy and wisdom joined together. He also took the verse “It is, and it is not,” which is the “yes and no” of Pythagoras, to mean the truth and falsity of human knowledge and the profane sciences.

Notice that the reference to an evil spirit foreshadows the scenario for doubt in the First Meditation wherein an evil demon keeps him off balance with his constant deception. The second dream was in some ways indistinguishable from waking life, which is a key point of the dream argument. Finally, “it is, and it is not” is one way of expressing the law of non-contradiction, which is a basic principle of geometrical reasoning. Also, recall that this line was found right after the verse “What path in life should I pursue?” One might then infer that the light of truth expressed through the Holy Spirit emblazoned these images into Descartes’ closed eyes to move him to pick up Pythagoras’s tool and set off on the path of discovery, which is the mode of demonstration underpinning the entire Meditations.

Perhaps Baillet intended his reader to make just such an interpretation in an effort to save Descartes’ illustrious works from the numerous condemnations they received from both pope and king, including placement on the Index of Prohibited Books in 1663. By encouraging his readers to infer that a divine light inspired Cartesian method and philosophy, Baillet may have been trying to save his legacy from this literary hell. However, without Descartes’ own account of these dreams’ influence on him, we are left with only the daydreams of our own shadowy speculations.

Featured image credit: René Descartes’ Principia Philosophiae by Nightryder84 (Own work). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The phosphene dreams of a young Christian soldier appeared first on OUPblog.

November 20, 2015

Spain 40 years after General Franco

Forty years ago today (20 November), General Franco, the chief protagonist of nearly half a century of Spanish history, died. ‘Caudillo by the grace of God’, as his coins proclaimed after he won the 1936-39 Civil War, Generalissimo of the armed forces, and head of state and head of government (the latter until 1973), Franco was buried at the colossal mausoleum partly built by political prisoners at the Valle de los Caídos (Valley of the Fallen) in the Guadarrama mountains near Madrid.

Under the guiding hand of King Juan Carlos, appointed Franco’s successor in 1969 when the dictator decided to re-instate the Bourbon monarchy, opponents and moderate elements in the regime came together and negotiated a transition to democracy, sealed in the 1978 Constitution.

Since then, Spain has enjoyed an unprecedented period of prosperity and peaceful co-existence, even taking into account the country’s prolonged recession which ended in 2014. The country telescoped its political, economic, and social modernisation into a much shorter period than any other European country.

Economic output increased almost tenfold between 1975 and 2015 to around $1 trillion.

Per capita income rose from $3,000 to $25,600.

The structure of the economy is very different: agriculture’s share of output dropped from 9% to 2.5%, industry – including construction – from 39% to 23%, and services increased from 52% to 74%.

Employment by sectors has changed even more: only 4% of jobs today are in agriculture compared to 22% in 1975, 14% of employment is in industry and construction, down from 38%, while services employ 76%.

Exports of goods and services more than tripled to 32% of GDP.

The inward stock of foreign direct investment in Spain surged from $5.1 billion in 1980 (the earliest recorded figure) to $722 billion in 2014.

The outward stock of direct investment jumped from $1.9 billion to $674 billion, with the creation of well known multinationals.

The number of tourists rose from 27 million to an estimated 68 million this year.

There were 123 cars per 1,000 people in 1975 and more than 500 today.

The population rose by 10.4 million to 46.4 million, mostly over a 10-year period as a result of an unprecedented influx of immigrants. In the decade before the 2008-13 crisis, Spain received more immigrants proportional to its population than any other EU country.

Average life expectancy for men and women was 73.3 years in 1975; today it is 82 years. Spanish women live 85 years, almost the longest in the world.

Close to 30% of the population was under the age of 15 in 1975; today it is 15%. Those over the age of 65 rose from 10% to more than 18%.

The average number of children per woman has more than halved to 1.3, one of the world’s lowest fertility rates.

“Francisco Franco and Carmen Polo” from Dutch National Archives, The Hague, Fotocollectie Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANEFO), 1945-1989. CC BY-SA 3.0 NL via Wikimedia Commons.

“Francisco Franco and Carmen Polo” from Dutch National Archives, The Hague, Fotocollectie Algemeen Nederlands Persbureau (ANEFO), 1945-1989. CC BY-SA 3.0 NL via Wikimedia Commons.Spain also became one of the world’s most socially progressive countries, a far cry from the rigid and asphyxiating morality of the Franco regime and the strictures of the powerful Catholic Church. In 2005, Spain legalised marriage between same-sex couples. Only three other countries at that time had taken this step –Belgium, Canada and the Netherlands.

In the Basque Country, the terrorist group ETA, which murdered 857 people in its more than 40-year fight for an independent state (95% of them since 1975), has been defeated by the rule of law. The group declared a ‘definitive’ ceasefire four years ago, although it has yet to lay down its arms.

The main black point as regards the economy is the unemployment rate: up from a mere 5% in 1975 to a whopping 22% today, although that low level at the end of the Franco regime was artificial as the economy was protected from the chill winds of competition and could not have sustained that situation for much longer.

No Spanish company was known outside of Spain in 1975, except, perhaps, for Iberia, the flagship airline, and the Real Madrid football club. Today, there are at least 20 companies with significant positions in the global economy. Santander is the largest bank by market capitalization in the euro zone and the leader in Latin America, Iberdola is the world’s main wind farm operator, and Inditex, best known for its Zara brand, is the world’s top fashion retailer by sales.

The country today faces several challenges. The massive unemployment, austerity, and corruption that flourished during the 2000-2007 boom are impacting politics. Two new upstart parties at the national level, the centre right Ciudadanos (Citizens) and the anti-austerity leftist Podemos (‘We Can’), will challenge the conservative Popular Party and the Socialists (the two parties that have alternated in power since 1982) in the general election on 20 December. Opinion polls show none of them will win an absolute majority.

The most heated problem facing Spain is the issue of Catalan independence. The parties campaigning for independence, an unholy alliance of conservative nationalists, radical republicans, and anti-capitalists, won 48% of the vote in September’s regional election and 53% of the seats in the Catalan parliament. This is hardly a clear mandate to declare a separate state.

Franco famously said that he had left his regime and its institutions ‘tied up, and well tied up.’ One, however, has proven to be very difficult and sensitive to untangle, and that is how to openly confront Spain’s recent past. Perhaps the wounds caused by a civil war are the most difficult to heal and so, this argument goes, better left as they are.

There is still no consensus on what to do with the contentious Valley of the Fallen monument, which in no way can be called a site of reconciliation. The failure to agree on how to confront the past makes it difficult to find an accord over an uncertain future.

Featured image credit: “El Valle de los Caídos” by Sigils. CC BY-SA 3.0 ES via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Spain 40 years after General Franco appeared first on OUPblog.

What history can tell us about food allergy

What can the history of medicine tell us about food allergy and other medical conditions?

An awful lot. History is essentially about why things change over time. None of our ideas about health or medicine simply spring out of the ground. They evolve over time, adapting to various social, political, economic, technological, and cultural factors. If we want to know anything about the health issues that face us today and will face us in future, the very first thing we should do is turn to the history of such issues. This is particularly important if we are dissatisfied with current ways of thinking about and treating particular conditions (as I have argued in the past with respect to ADHD or hyperactivity) or if we are bamboozled by the causes and deeper meaning of other conditions, such as food allergy. Otherwise, we are uninformed and highly likely to repeat the mistakes of the past.

A few weeks ago, my 16-month-old daughter broke out in spots. As the parents of two remarkably healthy children, my wife and I were bemused. Our first thought was that she may have come down with chicken pox, a real pain, but not the worst thing in the world. We looked up some of the early symptoms of chicken pox online, which appeared to confirm our suspicions and steeled ourselves for a week of scratching and crying.

The following morning however, the spots had disappeared. We were flummoxed. Could chicken pox be a 24-hour thing? No such luck. Then, I remembered that I was the author of a book on food allergy. Could it have been something she ate? I tried to think about what she had been eating and then it struck me: strawberries.

Scottish people are often maligned for never eating fruits or vegetables. While this is true for some people, the traditional Scottish diet is actually chock-full of healthy foods. The cold and rainy climate allows us to grow plenty of neeps (turnips) and tatties (potatoes), and there is also a thriving berry industry in places such as Perthshire, and strawberries are central to this. Every year, when the sun shows its face and the buds begin to emerge, the first punnets of strawberries appear in supermarkets. And we dutifully buy them up, gobbling strawberries as fast as we can.

Although these days, thanks to greenhouses and breeding, the strawberry season can last well into the autumn. Traditionally, it was short, so people needed to get strawberries while they could. Possibly because of this overconsumption of strawberries at one time of year, symptoms attributed to strawberries are one of the most common instances of bizarre reactions to foods found in literature prior to 1906, when the term ‘allergy’ was coined. Sir Thomas More even claimed that none other than King Richard III took advantage of the fact that strawberries gave him a rash for political gain. In his History of Richard III, More states that the monarch surreptitiously consumed strawberries and then blamed the rash that followed on witchcraft orchestrated by one of his political opponents, Lord Hastings. Hastings was summarily executed.

None of our ideas about health or medicine simply spring out of the ground. They evolve over time, adapting to various social, political, economic, technological, and cultural factors.

Hoping that my daughter would never take advantage of her apparent sensitivity to strawberries, we stopped buying them for a couple of weeks. Then, we decided to conduct an experiment, and gave her a few. No rash. We waited another day or so and gave her a few more. Nothing. Although we were relieved in one way, we remained bewildered. Perhaps something else caused the rash? Or maybe the reaction was temporary or caused by eating way too many strawberries? Maybe it was some kind of intolerance, and not an allergy at all? It might be tempting to gravitate toward such an answer, but a quick look at many allergy websites suggests otherwise. Strawberries, they say, are not only common allergens, but reactions to them might be a harbinger of allergies to pineapples, kiwis, and other fruits. So what to do?

My research suggests that millions of parents have wrestled with such dilemmas in the past, and continue to do so today. Since food allergies can be interpreted by people (including physicians) alternatively as either deadly serious or completely overblown, it is difficult for parents to know what to do. Making matters more complicated is the fact that many allergies are known to fade away as children get older. I would be loath to give any sort of medical advice, but I hope it is some solace to parents these conundrums are not new. And, in the words of Dr. Spock, parents should also trust themselves to a large degree with respect to their children and possible allergies.

This article originally appeared on the Columbia University Press blog.

Featured image credit: “Strawberries” by Brian Prechtel. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What history can tell us about food allergy appeared first on OUPblog.

Obstacles on the road to a European Energy Union

Is Europe heading towards an Energy Union — the ambitious goal announced by the Commission at the beginning of this year? If so, many would say that it is about time. Energy has long been neglected by Europe. Europe did not even have any formal competence in this area until the Lisbon Treaty of 2007. Even then, its reach was strictly circumscribed. Member states retain the right to determine their own energy mix and the conditions for exploiting their national resources. On the face of it, this leaves little for Europe to do.

In practice, of course, things have not been quite so restrictive and Europe has played an increasing role in energy, in response to a growing commonality of interests between member states in three main areas:

The single market in energy. This seeks to create a level playing field for energy competition across Europe. It was a late starter, compared with other sectors, but over the past decade or so considerable progress has been made, to the extent that by the end of 2014 the single market in energy was, at least nominally, in place.

Climate change. Europe has common goals in this area and shares the burden of meeting climate change targets. All member countries are increasingly investing in low carbon sources, like renewables, and their energy systems are heading towards the same decarbonisation goal.

Energy security. In the past different member states have faced fundamentally different circumstances. The UK, for instance, being an energy exporter at the end of the last century, and determined to retain control over the development of its North Sea oil and gas. But all European countries are now increasingly dependent on imports from the same sources, and in particular Russia.

Image credit: Pilsen and Pollution by Señor Codo. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Pilsen and Pollution by Señor Codo. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.The proposal for an Energy Union was first put forward by Donald Tusk, then Prime Minister of Poland. He called on the Union to engage in collective purchasing of Russian gas, in an effort to reduce Russian dominance of European gas markets. This proposal never got off the ground — allowing buyers’ cartels would undermine the painful progress towards a single market — but the idea of an Energy Union was eagerly picked up. With Europe facing a series of crises and dissent in other areas, the idea of making progress on energy was particularly attractive and the conditions seemed favourable. But the obstacles are also serious. As the gas example indicates, the three trends outlined above do not necessarily pull in the same direction.

The push for decarbonisation, for instance, creates tensions with the single market and energy security goals. It inevitably involves government intervention in markets, and with each government entitled to intervene in its own way, the risk is of fragmented national markets rather than a level European playing field. In practice, Germany has chosen to close its nuclear fleet and invest heavily in renewables. Since these are inflexible and intermittent, the result has been huge flows of power into neighbouring countries, driven not primarily by market forces but by the German government’s policy preferences. Meanwhile the UK has decided to invest in nuclear and to support that investment by guarantees and payments outside the market under long term contracts, potentially foreclosing a significant proportion of the market from competition (and in practice there was only one bidder for the first plant, at Hinkley). So the single market is at risk of being undermined.

Even more fundamental problems may arise with basic market structures – electricity markets, for instance, are based on marginal prices, yet the new renewable sources generally have zero marginal cost and their introduction into the market creates widespread distortions, making it impossible to finance new plants directly from the market itself. To underpin investment, governments have therefore been introducing new instruments, like capacity mechanisms, on a national basis. Meanwhile, the Commission has been running hard to keep up and to introduce a degree of harmonisation in renewables support and capacity payments, but national priorities tend to dominate.

So the question may be not so much, ‘can Europe make progress towards an Energy Union?’ as ‘can Europe avoid sliding back into nationalised energy policies?’ The challenges are complex and sensitive and so far, despite its ambitious goal, the Commission has been proceeding rather cautiously and seems generally to be following rather than leading the process. Can this be changed? And what new policy initiatives are needed, if Europe is indeed to make progress towards an Energy Union? Without a determined effort by the Commission, the Energy Union goal may turn out to be little more than hot air.

Featured image credit: Untitled by steve p2008. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Obstacles on the road to a European Energy Union appeared first on OUPblog.

Correcting the conversation about race

On 6 November 2015, the New York Times featured a poignant five-minute documentary called “A Conversation About Growing Up Black,” produced by Joe Brewster and Perri Peltz. Brewster and Peltz present Rakesh, Miles, Malek, Marvin, Shaquille, Bisa, Jumoke, Maddox, and Myles. The youngest are 10 and the eldest is 25 years old. These nine individuals are very different from one another (hair, height, weight, skin color, voice, manner of speech, body language… all those things that combine to make each of us unique). As with all human beings, each of them is his own universe of individuality and each occupies several universes of other individuals known as family, friends, teammates, school mates, colleagues, and the like.

But we never learn much about the individuality of these individuals: where they live; where they go to school or work; what their worldviews might be on faith, politics, or the environment; what are their talents, their challenges; what they love, and what they dislike. Instead we are introduced to them as racialized human beings, adversely racialized nominally black males to be specific, who by dint of this social relegation are subject to suspicion, discrimination, degradation, and brutality.

We encounter them as living, breathing targets of racism.

We are graced with their eloquent and compelling meditations on racism, their narratives of being misrepresented, misunderstood and mistreated, and their heroic resolve to successfully navigate the mine-infested landscape of the racist country in which they live – for themselves and for their loving, protective, and worried parents.

It is a heartbreaking five-minutes of film.

And it will change nothing.

It will change nothing not because the producers or their nine testifiers lack courage or dedication to overcoming the scourge of racism. It will change nothing because it is, like virtually every effort made to resist racism, ironically and tragically recapitulative of the essence of racism – that is racialization.

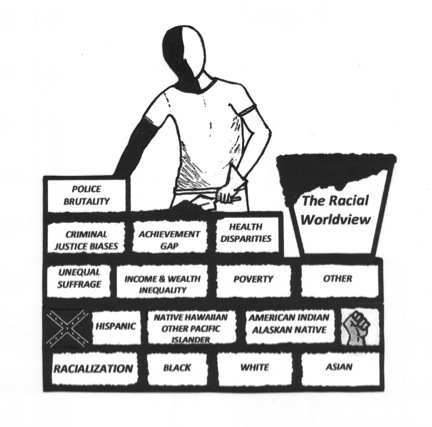

Racialization is the process by which races are fabricated. (The concept as utilized here is an adaptation of the concept defined in the Report of the Commission on Systemic Racism in the Ontario Criminal Justice System.) It entails the following steps:

Selecting some human characteristic as the signifier of subspecies difference between people (e.g. having a cleft chin);

Sorting people into different races based on the signifying characteristics (e.g. cleftchins on the seedy side of the wall/tracks, “normalchins” on the salubrious side);

Attributing qualities to the members of the so-called races that supposedly correspond to the signifying distinction (e.g. those cleftchins are not only odd craniofacially, they also tend towards moral deviance);

Essentializing the purported differences between the so-called races (e.g. cleftchins are different to the bone. The differences between them and us is not a matter of how they choose to behave, it is function of immutable inherited depravity and inferiority);

Acting as if this absurd chain of inference justifies discrimination, disenfranchisement, and acute and chronic instances of micro, mezzo, and macro inequity.

To end racial strife we must stop racializing others and stop racializing ourselves. Racialization is the mortar that holds together the edifice of racism, whether manifest at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, structural, institutional, or systemic level.

What might it look like to dissolve the mortar of racialization? Let’s take two statements from Brewster and Peltz’s “A Conversation About Growing Up Black” video.

(1) Brewster and Peltz writing within the racial worldview:

“Imagine strangers crossing the street to avoid you, imagine the police arbitrarily stopping you, imagine knowing people fear you because of the color of your skin. Many of this country’s young black men and boys don’t have to imagine.”

An alternative in a nonracial worldview:

Imagine strangers crossing the street to avoid you, imagine the police arbitrarily stopping you, imagine knowing people fear you because of the color of your skin. Despite the fact that relegating people to racial subgroups has long been known to be specious, many of this country’s nominally black men and boys don’t have to imagine.

(2) Brewster and Peltz writing within the racial worldview:

“In this Op-Doc video, “A Conversation About Growing Up Black,” we ask African-American boys and young men to tell us candidly about the daily challenges they face because of these realities. They speak openly about what it means to be a young black man in a racially charged world and explain how they feel when their parents try to shelter and prepare them for a world that is too often unfair and biased.”

An alternative in a nonracial worldview:

In this Op-Doc video, “A Conversation About Growing Up Racialized,” we ask adversely racialized young men to tell us candidly about the daily challenges they face because of the imposition of a false and stigmatized identity. They speak openly about what it means to be seen as members of a factitiously inferior human subgroup and explain how they feel when their parents try to shelter and prepare them for a world that is governed by the lethal absurdity of race.

While it is quite natural in terms of social convention for the producers of the video to write about their subject in racialized terms, it is quite unnatural in terms of biological and genetic reality. Because our systems and signals of meaning are facilitated, bound together, nourished, and shaped by the words we use, this shift in the language of race is not mere semantic maneuvering. Every time we matter-of-factly invoke the concept of race as a legitimate way of characterizing a human being, we further reify and concretize the illusion of subspecies within the one human species, and we savagely diminish complex individuals to one-dimensional targets. Use of the language of race has become so commonplace that it seems impervious to change. Calls to stop using the word “race” seem futile, if not heretical or dangerous (almost sure to provoke vehement knee-jerk rebukes and charges of dangerous colorblindness and post-racial fantasizing). Referring to individuals as members of races seems too deeply rooted and intertwined in popular and technical parlance to be retired. We seem trapped within the racial worldview. But we are not.

Towards the end of the video, Maddox, age 10, provides the following assurance to the world: “I want people to know that I am perfectly fine and I’m not going to hurt anybody or do anything bad.” Rakesh, also age 10, expresses the same simple, liberating, nonracial worldview principle so famously intoned by Martin Luther King Jr. over fifty years ago: “I should be judged about, like, who I am and, like, and what kind of person I am.” Neither of these individuals refers to himself as a “black” person.

To be clear, for all I know, each of these boys might very proudly embrace a sense of racial identity that simply was not expressed in these parting statements. What’s important to note is that they did not seem to feel a need to self-racialize in their expressions of the universal human desires to be trusted and appraised on the basis of being a fellow human being – nothing more, nothing less, nothing other.

While is quite necessary to relentlessly make all possible efforts to prevent, understand, and, as with this video, document the effects of racism, efforts that reproduce the reification of false differences (versus the effects of perceptions, beliefs and behaviors predicated on false differences) can never be sufficient. We must add to all efforts to quell racism a dedication to quit racialization and the racial worldview.

Image credits: (1) Bricks. CC0 via Pixabay. (2) Courtesy of Carlos Hoyt.

The post Correcting the conversation about race appeared first on OUPblog.

Einstein’s mysterious genius

Albert Einstein’s greatest achievement, the general theory of relativity, was announced by him exactly a century ago, in a series of four papers read to the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin in November 1915, during the turmoil of the First World War.

For many years, hardly any physicist—let alone any other type of scientist—could understand it. After general relativity received its first experimental confirmation in the solar eclipse of 1919, by astronomers led by Arthur Eddington, a famous story tells of how Eddington was approached by a fellow astronomer who had recently published a book on Einstein’s 1905 special theory of relativity. He said: “Professor Eddington, you must be one of the three persons in the world who understands general relativity.” When Eddington demurred, his colleague persisted: “Don’t be modest, Eddington,” and received the crushing reply: “On the contrary, I am trying to think who the third person is.” But after some decades of controversy, since the space programme of the 1960s general relativity has been regarded by most cosmologists as the best available explanation for the observed structure of the universe, including black holes, if not the complete explanation.

However, even today hardly anyone apart from specialists understands general relativity—unlike, say, the theory of natural selection, the periodic table of the elements or the concept of wave/particle duality in quantum theory. So why is Einstein the world’s most famous and most quoted (and misquoted) scientist, far ahead of Isaac Newton or Stephen Hawking—and also a legendary byword for genius? His fame is a puzzling phenomenon. As an Einstein biographer, let me to try to unravel the mystery, at least a little, by considering the reactions to Einstein of a wide range of people during his lifetime and since his death in 1955, as well as his own surprised reaction to his fame.

For example, when Einstein gave lectures about general relativity at Oxford University in 1931, the capacity academic audience soon ebbed away—baffled by both Einstein’s mathematics and his German—leaving only a small core of experts. Afterwards, a cleaner rubbed the equations off the blackboard (though thankfully one blackboard was saved and is on display in Oxford’s Museum of the History of Science). Yet, in the very same year, when Einstein and his wife appeared as the personal guests of Charlie Chaplin at the premiere of Chaplin’s film, City Lights, in Los Angeles, they had to battle their way through frantically pressing and cheering crowds—on whom the police had earlier threatened to use tear gas. The entire movie theatre rose in their honour. A somewhat baffled Einstein asked his host what it all meant. “They cheer me because they all understand me, and they cheer you because no one understands you,” quipped Chaplin.

Albert Einstein, 1947, via the Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Albert Einstein, 1947, via the Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In the 1940s, Einstein informed a biographer: “I never understood why the theory of relativity with its concepts and problems so far removed from practical life should for so long have met with a lively, or indeed passionate, resonance among broad circles of the public… I have never yet heard a truly convincing answer to this question.” To a New York Times interviewer he disarmingly remarked in 1944: “Why is it that nobody understands me, yet everybody likes me?”

Part of the reason for Einstein’s fame is surely that his earliest, and best known, achievement—his 1905 special theory of relativity—seems to have come out of the blue, without any prior achievement. Einstein (like Newton, but unlike Charles Darwin) did not have anyone of distinction in his family. Indeed Einstein himself insisted in old age that “exploration of my ancestors … leads nowhere” in explaining his particular bent. He was not notably excellent at school and college (unlike Marie Curie); in fact he failed to obtain a university post after graduation and had to accept a position as a patent clerk. He was not part of the scientific establishment, and worked mostly alone, during the period 1905-15. In 1905, he was young and struggling, with a newly born child. His apparently sudden outbreak of genius inevitably intrigues us all, regardless of whether or not we grasp relativity.

A further reason for his fame is that Einstein was active in many fields far from physics, notably politics and religion, including Zionism. Best known are his open opposition to Nazi Germany from 1933, his private support for the building of the atomic bomb in 1939 and his public criticism of the hydrogen bomb and McCarthyism in the 1950s, which was secretly investigated by the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover, who was determined to prove that Einstein was a Communist agent. In 1952, Einstein was offered the presidency of Israel, but declined. Clearly, his turbulent later life and courageous stands fascinate many people who are bemused by general relativity.

According to the philosopher Bertrand Russell, who knew Einstein personally: “Einstein was not only a great scientist, he was a great man.” The mathematician Jacob Bronowski proposed: “Newton is the Old Testament god; it is Einstein who is the New Testament figure… full of humanity, pity, a sense of enormous sympathy.” The science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke guessed: “Einstein’s unique combination of genius, humanist, pacifist and eccentric made him accessible—and even loveable—to tens of millions of people”. The biologist Richard Dawkins calls himself: “unworthy to lace Einstein’s sockless shoes… I gladly share his magnificently godless spirituality.”

Such a combination of solitary brilliance, personal integrity and public activism is rare among intellectuals. Add to this Einstein’s lifelong gift for witty aphorism when dealing with the public, the press and fellow physicists. For example, his popular summary of relativity, given to his secretary for communication to casual enquirers: “An hour sitting with a pretty girl on a park bench passes like a minute, but a minute sitting on a hot stove seems like an hour”. Or his sceptical response to the role of chance introduced in quantum mechanics: “God does not play dice.” Or my own favourite Einstein comment: “To punish me for my contempt of authority, Fate has made me an authority myself.” And one has at least some rationale for Einstein’s unique and enduring fame.

Featured image credit: Albert Einstein in a Classroom. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Einstein’s mysterious genius appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers