Oxford University Press's Blog, page 589

November 14, 2015

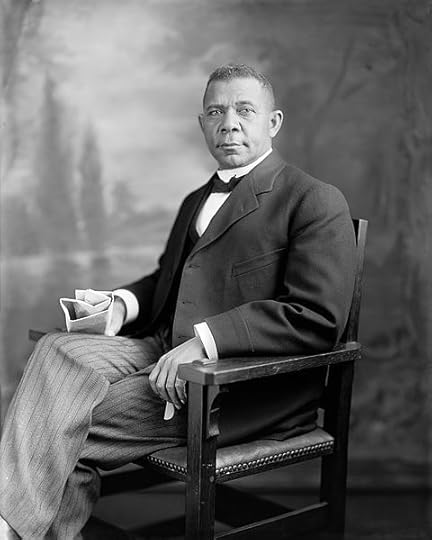

Booker T. Washington’s undervalued legacy

When Booker T. Washington died on this day in 1915, he was widely regarded not just as “the most famous black man in the world” but also “the most admired American of his time.” In the one hundred years since his death, he and his legacy have lost much of their luster in the eyes of the public, even though he, no less than Frederick Douglas, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Martin Luther King, Jr., is one of the foremost figures in the history of the American civil rights movement. All four were eloquent proponents of the cause. All four advised U.S. presidents on matters pertaining to race relations. All four braved the dangers of virulent racism to play critical roles in nudging forward equal rights for their people. King’s dazzling oratory and martyrdom earned him singular acclaim among the four, whereas Washington, for reasons rooted in the wisdom of hindsight, has been relegated to the periphery of the civil rights movement as the least among its leaders. Modern historians have tended to dismiss him as an anomaly and an embarrassment for having accepted segregation, for his outward humility and his opposition to black militancy. He has been criticized for having struggled to get what he could for his people rather than what they deserved, for having been subservient to white interests, for remaining silent before racial injustice, for accepting second-class education for blacks, and for suppressing dissent among blacks who opposed him.

Photograph of Booker T. Washington taken sometime between 1905 and 1915, from the Harris & Ewing Collection at the Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Booker T. Washington taken sometime between 1905 and 1915, from the Harris & Ewing Collection at the Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.And yet, Washington accomplished much during a career that coincided with an end of effective black political power in the post-Civil War South. At a time when vigilante groups such as the Klu Klux Klan, the White League, and the Red Shirts made learning to read and write in the Deep South a life-threatening endeavor for black Americans, he succeeded, in just two decades, in building from scratch a university in Tuskegee, Alabama that boasted one hundred new buildings, a faculty of nearly two hundred black men and women, a student body composed of people of color from around the world, and an endowment of nearly two million dollars. The thousands of graduates of what is now the Tuskegee University are his principal legacy. However, he also used his position and influence as Frederick Douglass’s successor in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War to direct charitable contributions from northern philanthropists such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Julius Rosenwald to many of the nation’s other black institutions and causes.

Shortly before he died, Washington began to abandon his accommodationist tactics in advancing the civil rights of black Americans by denouncing unequal educational facilities, disenfranchisement, lynching, and segregation of his people. What more he might have accomplished if the evolution of his program hadn’t been cut short by the ravages of malignant hypertension, unfortunately, will never be known.

Featured image credit: Segregation 1938b by John Vachon, U.S. Farm Security Administration. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Booker T. Washington’s undervalued legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

Film-makers choices in adapting Richard II

The start of a film version of a Shakespeare play offers a pretty good clue to the nature of the adaptation. So how, for instance, does Richard II begin? In one sense it begins like this:

ENTER KING RICHARD, JOHN

OF GAUNT, WITH OTHER

Nobles and attendants.

(Q1, 1597, A2r)

Which is perhaps not too radically different from beginning like this:

Actus Primus, Scæna Prima

Enter King Richard, John of Gaunt, with other Nobles and Attendants.

(F1, 1623, b6r)

On stage, any number of events can mark the start. I cannot help but think particularly of Sam West as Richard (RSC, The Other Place, 2000, directed by Stephen Pimlott) sitting on the coffin that, at the production’s end would hold his body, reading a speech (usually from the prison scene) before deciding whether to turn, mount the stairs to the throne, commit to the evening’s performance and to being King, and, when he had committed, the house lights cut out and the stage lights crashed on. Or of Richard Pasco and Ian Richardson (RSC, Royal Shakespeare Theatre, 1973, directed by John Barton), leading lines of actors onto the stage, summoned by a figure dressed as Shakespeare and, as they held aloft between them a crown and a mask, he nodded at the one who would play Richard that night and the actors began to dress for the performance. These two stage productions are seared into my memory so that I cannot read or think about the play without their coming to mind. Neither begins as Q1 begins. Each defines its approach through these pre-dialogue moments. Each uses actors and, in Pimlott’s case, simple and necessary props to create that definition.

And on screen? It might begin with a slow tracking shot across a wooden ceiling in an astonishing medieval building, down across a beautiful crucifix and then a tapestry and finally to a throne with Richard in it, impassive, holding orb and scepter, before a rapid full reverse to a shot of dozens of courtiers looking back at him. The opening shot lasts 50 seconds, while a voice-over, Richard’s we might assume, close-miked and intimate, almost whispering, certainly not located in the acoustic of the vast space we are looking at, speaks lines that, for those who do not know the play, will prove to come from much later on:

Let’s talk of graves, of worms and epitaphs,

Write sorrow on the bosom of the earth.

Let us sit upon the ground

And tell sad stories of the death of kings –

How some have been deposed, some slain in war,

Some haunted by the ghosts they have deposed,

Some poisoned by their wives, some sleeping killed –

All murdered. (3.2.145, 147, 155-60)

If we know the play very well, we might note that the speech has been cut, sixteen lines down to eight, and that the third line has been truncated by removing “For God’s sake,” leaving this wondrous line of eight monosyllables and one dissyllable oddly short of three of them. This is the opening of Richard II as a film for television, directed by Rupert Goold, made as part of The Hollow Crown, four films covering the second tetralogy, released in 2012.

‘9’ by Kirill Proskurin. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

‘9’ by Kirill Proskurin. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Or it might begin with a strong, perhaps even startling, overhead shot, looking straight down at a woman, hunched down beside a draped coffin, her arm stretched out over it, clearly in grief. Before the camera moves back and down, we hear the sound of feet, and people start to come into shot, taking up formal positions behind and beside the coffin, while projections on to the curtains of thin chains behind them create the image of a grand medieval interior but which the foreground revealed as a thrust stage with audience members either side of it. The shot lasts a long 80 seconds, with no dialogue, only the sound of three angelic women’s voices, accompanied by a solo trumpet, the singers seen in the gallery. Finally it cuts to a medium shot of the two old men, one either side of the coffin, one in tears, grief-stricken, the other patting the mourning woman’s arm comfortingly. This is the opening of Richard II as a live relay of the RSC’s 2013 production by Gregory Doran, transmitted to cinemas on 13 November 2013, a month into the production’s run, and subsequently released as a DVD.

Two very different and equally arresting openings. One uses a chunk of text to define the production’s sense of the key moment, visual imagery to define historical moment, the presence of the crucifix to foreshadow its interest in Richard as Christ or as Saint Sebastian, and an edit and the locational distance to mark Richard’s separation from his court. The other makes us overwhelmingly aware of grief, of mystery (who is in the coffin?), of a space at once ecclesiastical and political (actually evoking Westminster Hall), and also a space that is a stage in a theatre with an audience present, not a location shoot for a film. Both openings make us want to watch and listen and consider and think. Two invitations to engage with Shakespeare on screen.

The post Film-makers choices in adapting Richard II appeared first on OUPblog.

November 13, 2015

OAPEN-UK: 5 things we learnt about open access monographs

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. In this blog post, we are looking at the potential of open access monograph publishing.

In September 2010, the OAPEN-UK research study set out to investigate the potential of open access monograph publishing in the humanities and social sciences disciplines (HSS), which was, at the time, a relatively unknown concept. The collaborative study aimed to contribute to the evidence base and understanding of open publication models, in order to inform the debate and direction taken by the scholarly community.

OUP joined the study for the final two years of the project; contributing 18 academic titles to the experiment which were made open access under a Creative Commons licence. Here’s what we learnt.

1. How to make a book open access

OUP have previously made books and chapters freely accessible on many occasions but this study required us to establish a more formal open access process. The 18 titles were made freely available online as a PDF download under a Creative Commons (CC BY-NC-ND) licence, and were free to read via Oxford Scholarship Online and Google Books. We needed to think about the practicalities of this task and the challenges of hosting open content on systems and websites that were designed for other business models. Based on our initial experiences from this pilot, we’re continuing to work towards more durable solutions for hosting open access content and developing better process/workflows for open books.

2. The difficulty of establishing a controlled experiment

The study methodology sought to use matched pairs to provide a control for the evidence. Each experiment title was matched with another title to measure the impact of open availability on sales and usage patterns. There was an immediate challenge in finding suitably matched titles given the range of variables; similar publication dates, the research area, price point, audience, etc.; added to this were the challenges of creating similar market conditions to allow for a fair experiment. It became clear that there are many factors that can affect the course of sales and usage over a book’s publication life and sales channels will often mean that there is little concrete information on the eventual purchaser, let alone the intended use. Eliminating the potentially confounding variables for outputs that, by definition, are highly individual to sufficiently allow comparison with a meaningful control has proven very difficult. We’ve built a wealth of data over the two years, but realistically we have to be very careful about the interpretation of that data. A larger, or longer, study might better eliminate these complex variables but any further research into this area would benefit from a process that would offer insight into the intended use, purchase decisions, and profile of the end-user.

3. Readers are discovering and using open titles

Nevertheless, the provision of a freely downloadable, open access PDF version of each experiment title was a distinctive factor in this experiment. These were placed on our websites and made available through the OAPEN Library and the Directory of Open Access Books. From Sep 2013 to Aug 2015, OAPEN-UK measured a total of 21,151 COUNTER compliant PDF downloads of these titles and 43,655 non-COUNTER compliant downloads. We reported 4,441 PDF downloads from our own website, which we measured from across 124 countries worldwide. The highest usage rates on our website occurred in the UK, US, Netherlands, Germany, and Australia, and it was pleasing to note that some titles received the best usage levels in the countries relevant to the research focus. This was aided in part by promotion from our local representatives, as well as the authors themselves, who used their own research networks to disseminate the free version. When an author blogged or tweeted about their free book, the usage levels rose significantly. This is interesting both in terms of engaging communities of concern but also in recognising that the scale of the project means it’s difficult to infer how purchasing and usage behaviours would change if the model were more widely-established.

4. We’re gaining skills and awareness of open access

As a business, our skills and knowledge have improved through the practical experience of this pilot. Using what we’ve learnt, we can now look to developing our own policies and best practice for open access to allow authors with publishing requirements to make their work available under a Creative Commons licence. It’s difficult to detach our experience of OAPEN-UK from other developments and conversations about open access monographs that have advanced apace in the last few years. Professor Geoffrey Crossick’s report for HEFCE on Open Access Monographs was well-received as presenting a thoughtful and fair review of the current state of scholarly monographs in the UK as well as possibilities for open access models. Other pilot studies and experiments by publishers and institutions are adding to the debate, leading us to…

5. Collaborative working with all stakeholders

From the outset, the study highlighted the need for a collaborative and agile approach from all stakeholders. While it has been difficult to have confidence in the quantitative evidence produced by the matched pairs experiment, the qualitative evidence provided by the study certainly contributes to our understanding of our own position as publishers, and the challenges now faced by various stakeholders in an open environment for books. It’s hard to address many of the practical challenges raised as the way forward is still so uncertain. OAPEN-UK investigated one of many potential business models; Geoffrey Crossick’s report highlighted a “mixed environment” for books which could exist for the foreseeable future, whereby we have a number of business models in use for open publication, which may even vary between disciplines. This makes it very difficult to plan for and to invest in the necessary development, but one thing is clear, that the best direction now is to work together collaboratively, in the spirit of the OAPEN-UK project, and find solutions that work for all stakeholders.

Featured image credit: Computer keyboard, by Marcie Casa. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post OAPEN-UK: 5 things we learnt about open access monographs appeared first on OUPblog.

University Press Week blog tour round-up (Friday)

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Here’s a quick round-up of topics discussed on the University Press Week blog tour on Friday.

For the last few years, the AAUP has organized a University Press blog tour to allow readers to discover the best of university press publishing. On Friday, their theme was “University Presses in Conversation with Authors” featuring interviews with authors on publishing with a university press, writing, and other authorial concerns.

Why publish with a University Press? Eric Tang, author of Unsettled, reveals why Temple University Press was a great home for his work.

Speaking of translators, won’t this be expensive? Yes. Christine Dunbar discusses the Russian Library series with Columbia University Press.

Poetry and being alone. University of Virginia Press speaks with poets Tiana Clark and Emily Vizzo.

Galvanizing and sustaining. Beacon Press Executive Editor Gayatri Patnaik interviews Jeanne Theoharis, author of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks.

Let’s talk Scandal. University of Illinois Press interviews Feminist Media Studies series editor Carol Stabile.

An accidental discovery leading to new information about Civil War-era chemical weapons. SIU Press intern and SIU MFA-in-poetry candidate Kirk Schlueter interviewed Guy R. Hasegawa about his new book, Villainous Compounds.

“no one writes letters any more” University of Kansas Press interviews Lisa Silvestri, author of Friended at the Front.

From tens of thousands of images to 500. Oregon State University Press speaks with Larry Landis, author of A School for the People: A Photographic History of Oregon State University.

You have to be patient. Dr Jon Hogg, Senior Lecturer at the Department of History, University of Liverpool, talks to Alison Welsby, Editorial Director at Liverpool University Press about a forthcoming Open Access e-textbook, Using Primary Sources.

Just Food. University of Toronto Press spoke with Galya Hildesheimer and Hemda Gur-Arie, authors of “Just Modeling?: The Modeling Industry, Eating Disorders, and the Law” about their article, their experience publishing it with IJFAB, and how their research fits into the wider study of feminist bioethics.

Featured image: Suché skály, Česká republika. Photo by Jakub Sejkora. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post University Press Week blog tour round-up (Friday) appeared first on OUPblog.

Getting to the core of StoryCorps, and other audio puns

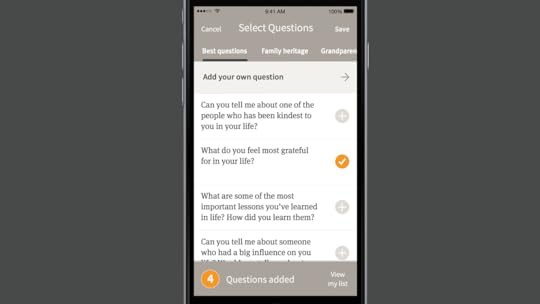

In two weeks, as students across the United States are enjoying their Thanksgiving break, StoryCorps wants to give us all a bit of homework. Calling it the Great Thanksgiving Listen, they are asking high school students to use their mobile app (available in iTunes or Google Play) to “preserve the voices and stories of an entire generation of Americans over a single holiday weekend.” Being both excited about the idea and curmudgeonly skeptical about the value of crowd-sourced oral history, I decided to try out the app to see what all the fuss is about.

The good:

Opening up the app and setting up the recording is very straightforward. When creating a new interview, you can enter the names of the participants, as well as an estimated time limit, which can be used or ignored during the actual recording. Perhaps the most useful part of the pre-interview process is the extensive list of questions to ask in an interview, as well as the ability to add in new questions. They’re divided into multiple categories, like “Warm up,” “Family heritage,” and “Remembrance,” with questions ranging from the very light (“What songs remind you of summer?”) to the incredibly heavy (“How do you imagine your death?”). Since I was interviewing my still-very-much-alive mother for this test run, I chose to avoid the morbid questions and stick to slightly lighter fare. Once the questions have been selected, the app allows you to arrange them into a logical order before starting the interview.

During the recording, the app works wonderfully. It begins with a basic prompt asking who is participating, then presents the questions you’ve pre-selected. You can swipe through the questions as you go, and drop markers into the interview timeline to easily find where topics shifted. When the interview is over, the interview can be uploaded to the StoryCorps website or kept it on the device for future enjoyment.

The bad:

Shortly after I started the recording for the first time, my mom had a few questions about what exactly we were doing again. This required a bit of explanation, so I tried to pause the recording while we discussed it. There is no try, however, nor is there a pause button. There is only do, and what I did was press the stop button, which completely ended the interview. Once the interview stops, it’s done. There is no going back to restart it. The audio can’t be edited. Once it’s done, it’s really done. This was frustrating on its own, but the biggest annoyance came when I realized that I couldn’t copy the interview and start again. Instead, I had to start from scratch, selecting the questions and adding in the metadata. Allowing the questions to be copied over from one interview to the next, as well as the ability to make interview templates, could be useful when interviewing multiple people about the same subjects.

Image courtesy of author.

Image courtesy of author.Some more quirks arose after the recording finished. The app asks you to take a picture of both interviewer and interviewee, and won’t let you move forward until you’ve taken one. It also doesn’t allow users to upload previously taken images, even if both you and your mother have already changed into your pajamas after a very long day and you don’t particularly want to have a picture taken at that moment. Additionally, you can choose to upload the finished interview to the StoryCorps website or keep it in the app, but there is no option to export the audio without first uploading it to the website. This makes sense for an organization whose primary interest is preserving the interview, but it is frustrating for an end user who may not want their awkward questioning and terrible puns to be forever preserved in the Library of Congress.

More familiarity with the app could have helped to circumvent these issues, but these minor annoyances add up to a somewhat less pleasant experience than should be reasonably expected from such a friendly looking application.

The ugly:

Aside from a few kinks, the app works great. It works great, that is, when it works. After using the app for a few days on my iPhone, I updated to Apple’s latest and greatest software, which completely disabled the app. For a couple of weeks, the test interviews I had done were locked deep inside my phone, inaccessible until the developers could fix the problem.

The long awaited update finally came; however I was frustrated to find out when I opened that app that the interviews I had conducted were gone. In the process of installing the update, the app had decided that what we really needed was a clean slate to move our relationship forward. To be fair, I could have avoided this fate by uploading the audio to the StoryCorps website. I had intended to, but it was the beginning of the semester and I hadn’t had the time to finish filling in the summary and metadata before the update came out.

The interview I used to test the software is now gone forever. For a light hearted conversation between a mother and son, this probably isn’t a major loss. But the app’s downtime and the possibility of erasure could seriously derail a more time sensitive or serious oral history project. The bugs all seem to be worked out now, so hopefully the Great Thanksgiving Listen can go off without a hitch.

If you decide to try out the app, or have experience with other similar applications, we’d love to hear from you! Consider submitting your experiences to the blog, or chime into the conversation in the comments below, or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, and Google+.

Image Credit: “Story Corps” by Omar Bárcena. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Getting to the core of StoryCorps, and other audio puns appeared first on OUPblog.

Junior doctor contracts: should they be challenged?

On Saturday, 17 October, 20,000 people marched to protest against the new junior doctor contracts in London for the second time.

The feeling at the protest was one of overwhelming solidarity, as people marched with placards of varying degrees of humour. Purposely misspelled placards reading “junior doctors make mistaks” were a popular choice, while many groups gathered under large banners identifying their hospital, offering 30% off – a figure the BMA published, noting the potential cuts junior doctors could face to their salary. Many placards joked that they were just passing through on the way to the airport, as it’s argued countries such as Australia offer far better contracts for junior doctors.

Similar protests have taken place throughout the United Kingdom, including in Leeds and Belfast as the country expresses outrage against the new junior doctor contracts.

The new contracts, proposed by UK Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt, aim to reduce the number of essential hours that a doctor is allowed to work. The Health Secretary has referred to the contracts as a “good deal”, telling BBC Radio 4’s Today programme that the plans will benefit junior doctors, and increase patient safety.

The junior doctor protest, London, 17 October 2015. Photographs by Stefanie De Lucia.

The junior doctor protest, London, 17 October 2015. Photographs by Stefanie De Lucia.The British Medical Association, who entered into talks to negotiate new contracts for junior doctors in 2012, paints a very different picture. They have said that the offer made by the Government is unacceptable, and decided to leave negotiations. The BMA insists that “[they] cannot allow a new contract to be imposed which would be bad for doctors, patients and the NHS.”

In interviews conducted with junior doctors, as well as Oxford University Press authors and editors, we investigate why junior doctors are protesting, and the potential impact the new contracts could have on healthcare in the UK. From a feared decline in patient safety, to a decline in contributions to academic research, there seem to be many potential repercussions of the new junior doctor contracts….

Lydia Spurr, Co-author, So you want to be a doctor?

Recent times have been unsettling for us as junior doctors. Although the current pay-structure isn’t perfect, it’s difficult to understand how the proposed changes will not lead to lower take-home pay – in exchange for longer, or more antisocial hours.

Ultimately, we’re not asking for higher pay, or time off: we’re asking to be treated fairly and for our representatives to be able to negotiate with the government. We are under threat imminently from the enforcement of an unfair contract, which threatens to remove safeguards to our working hours. This is a retrogressive step with clear and direct implications for the safety of both patients and doctors. Personally, I’m unable to trust a government who continue to misquote and misinterpret data to support their own agenda, and who continue to attempt to demonise and demoralise junior doctors.

Attending the protest in London on 17th October highlighted without doubt the camaraderie and unity of the very people this contract is going to affect – thousands of junior doctors, but also their families and patients. More recently, the government’s offer of an 11% rise in basic pay is grossly misguided, miscalculated, and mistimed with the opening of strike ballot. As doctors, we have a duty to protect our patients; the current offers seriously threaten to reduce our ability to do this effectively. While strike action may be unpopular with some, it is driven by our genuine desire to protect both ourselves and our patients.

Anonymous – CT1 anaesthetics trainee:

The reason we are all protesting is fundamentally because the nation’s health is seen as second to profit amongst today’s politicians. The current secretary for health has no concept of life working as a junior doctor. We are tired of working dangerous hours, tired of having no choice of when we take annual leave, and we refuse to be penalised for standing up for patient safety. We want to let the public know how exhausted we are as a profession, and that this should not be allowed to continue. According to WHO figures, the NHS is currently the most efficient healthcare system in the world. We have one of the lowest numbers of doctors per capita in Europe, and what Jeremy Hunt is proposing is further stretches in this service. We cannot let this happen.

Eleana Ntatsaki and Vass Vassiliou, Associate Editors, Oxford Medical Case Reports:

Junior doctors are committed to continuing professional development at every opportunity. In their limited spare time, as well as studying for difficult and expensive mandatory professional exams, they read and evaluate research, complete numerous work-related online assessments, and attend additional training courses and medical conferences. They produce high-quality academic manuscripts about interesting and complex cases in order to share this clinical experience and learning with the wider medical community, submitting them for publication to journals like the Oxford Medical Case Reports.

It would be a great loss, not only for the NHS and our patients, but for the whole academic community, nationally and internationally, if junior doctors were to be deprived of the motivation and time to continue contributing to the academic world and forced to bypass their inquisitive and reflective nature and extremely strong sense of vocation or even exit this profession.

Dr Charis Banks, junior doctor:

During my career I have worked 12 days in a row, I have worked 100 hours in 8 days, I have worked 3 hours longer than I was being paid to do – every day, for months. I am not unique, this is what we do – my colleagues and I – and we do it because we care about our patients. We miss time with our own family and friends so that we can look after yours.

So why am I angry? I’m angry because Jeremy Hunt is trying to destroy the NHS without the general public realising. He is trying to impose a new contract on us. He has decided that it is ‘sociable’ to work at 9pm on a Saturday night. He has decided that the current safeguards which are in place to protect us from working 100 hours every week are unnecessary. He has decided that on top of increasing our hours he will cut our pay, by 30%.

I want to tell you we are always here, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, front-line medical and nursing staff providing acute and emergency healthcare to patients whenever they need it. We will fight and keep fighting to save the NHS and to protect our patients – what other choice do we have?

Featured Image Credit: ‘Stethoscope’ by Parentingupstream. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Junior doctor contracts: should they be challenged? appeared first on OUPblog.

Harriet Jacobs: the life of a slave girl

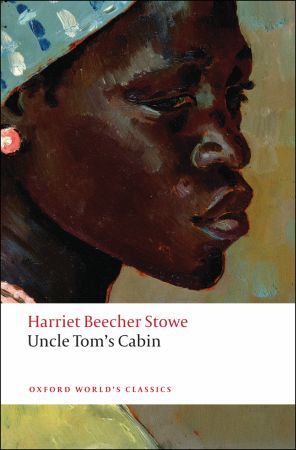

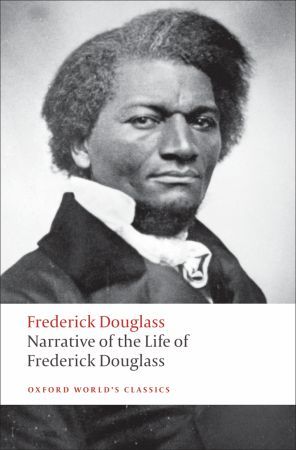

In 1861, just prior to the American Civil War, Harriet Jacobs published a famous slave narrative – of her life in slavery and her arduous escape. Two years earlier, in 1859, Harriet Wilson published an autobiographical novel, Our Nig; or, Sketches from the Life of a Free Black, tracing her life as “free black” farm servant in New England.

Both books tell moving stories about African American women suffering at the hands of white racists (Jacobs was particularly concerned to show how slavery enabled appalling sexual abuse). Both underline how such racism did not just exist amongst slave-owning southerners and pro-slavery advocates, but also amongst slavery’s opponents. Wilson shows how her Northern farming family, though broadly anti-slavery, allowed her to be tortured by the family matriarch, whilst Jacobs’ book explores how racist incidents blighted her life in the so-called Free North. Jacobs even exposes how Harriet Beecher Stowe, who she turned to for assistance, wanted to use Jacobs’ story merely to underline Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s accuracy. Jacobs objected, because she would lose all authorial control. Frederick Douglass also experienced this problem: white editors and sponsors generally wanted escaped slaves simply to tell their story—leaving all analysis and ethical reflection to whites. This patronizing attitude was, at its core, racist.

One justification for such patronage was a belief that proving the authenticity of African American narratives was vital. Our Nig and Incidents were written at a time when southerners, recognizing how anti-slavery sentiments threatened slavery’s continuation, were keen to depict African American as northern propaganda, misrepresenting the benevolent institution of slavery. To combat such mendacity, abolitionists urged African Americans to limit themselves to straight autobiography, arguing that such simplicity enhanced credibility.

Even today critics still often focus upon pre-Civil War African American writings’ autobiographicality. Important research has resulted, proving that Wilson was a species of indentured servant, kept in near-slavery until eighteen years old, and that Jacobs’ incredible story of her concealment in a tiny attic for seven long years was true.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

‘by Harriet Beecher Stowe

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

‘by Harriet Beecher StoweYet such an emphasis preserves a species of unconscious racism, by underplaying how African Americans dealt culturally with existence before the Civil War. Their lives were so restricted, oppressed and even violently repressed that they developed and drew upon a common reservoir of images, symbols, and metaphors, in order to generate as much oppositional power as possible. Consequently, their valuation of originality and individuality were different to those of whites: more complex and nuanced.

Instead they revisited existing narratives strategically, to add heft to their stories. One famous example is William Wells Brown, who constantly laced-in other writers’ resources. Close to plagiarism though it was at times, his work re-deployed established attacks on racism. Both Wilson and Jacobs incorporate a similar, if more subtly adaptive process, in artful narratives that even have central “characters”: Frado and Lucy, respectively.

Wilson’s narrative is highly structured. Her title page foreshadows key themes: Our Nig; or Sketches from the life of a Free Black in a Two-Story White House, North Showing that Slavery’s Shadows Fall Even There; By “Our Nig”. Frado cannot escape the circle of slavery (Our Nig <> “Our Nig”); her white farm house’s racism is legitimated by the White House; she is not “Free,” despite the Declaration of Independence; and, like New Englanders generally, her farm family tells two stories: publically, one of benevolence; privately, one of racism. Her story is also carefully shaped. To enhance our sympathy, Frado is constructed as a lively child, but the ways she displays her bright personality – outsmarting an aggressive male sheep, dancing on a farmhouse roof, making her teacher believe his desk is on fire – draw upon common symbolic motifs in children’s stories. Relatedly, her beatings echo those depicted in slave narratives.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

by

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

byFrederick Douglass

Jacobs’ narrative similarly introduces incidents drawing on stock representations of slavery. For example, in both John Brown’s 1855 slave narrative, Slave Life in Georgia, and Jacobs’ Incidents painful cleansing agents are applied to a slave’s back just after a whipping; and slaves are tied up in a back-straining “buck” in order to enhance their pain. Jacobs also draws upon Theodore Weld, Angelina Grimké Weld and Sarah Grimké’s 1839 anthology of slave mistreatments, American Slavery As It Is. Take this passage:

I turn to another [scene] … a stage [was] built, on which a mother with eight children were placed, and sold at auction. … seven of the children were torn from their mother, while her discernment told her they were to be separated probably forever, causing … the most agonizing sobs and cries …. The scene beggars description

… In the “Macon (Ga.) Telegraph,” Jan. 15, 1839, MESSRS. T. AND L. NAPIER, advertise for sale Nancy, a woman 65 years of age, and Peggy, a woman 65 years of age.

In Incidents this becomes:

I saw a mother lead seven children to the auction-block. She knew that some of them would be taken from her; but they took all. The children were sold to a slave-trader, and their mother was brought by a man in her own town. … I met that mother in the street, and her wild, haggard face lives to-day in my mind. She wrung her hands in anguish, and exclaimed, “Gone! All gone! Why don’t God kill me?” I had no words wherewith to comfort her.

… I knew an old woman, who for seventy years faithfully served her master. She had become almost helpless, from hard labor and disease. Her owners moved to Alabama, and the old black woman was left to be sold

Both stories draw upon stock narrative elements—the auction block and the old, discarded slave, but Jacobs ramps up the power by selling off “all” the slave mother’s children. Jacobs constantly works into her life story an African American tradition of refashioning common tropes drawn from many sources to create powerful patchworks, stitching together slavery’s patterns of personal and institutional excess and cruelty.

Certainly, both Wilson and Jacobs are writing autobiographically, but this is artfully laced with communal tropes, in order to enhance the levels of resistance their narratives can provide in denouncing racism and varieties of enslavement. This is quite different from white writers’ valorization of individual creativity. But it proves to be far more compellingly forceful when seeking to confront head-on nationwide racist cruelty. These narratives need to be read in this light. And we can learn from their observation that almost no whites are free from traces of racism.

Featured image: Old Wagon by Brigitte Werner, Public Domain via Pixabay

The post Harriet Jacobs: the life of a slave girl appeared first on OUPblog.

The politics of the ‘prisoners left behind’

At the time of its creation, the Imprisonment for Public Protection (IPP) sentence, targeted at ‘dangerous offenders’ considered likely to commit further serious offences, elicited little parliamentary debate and even less public interest. Created by the Labour government’s Criminal Justice Act 2003, the sentence was subsequently abolished by the Conservative-led coalition government in the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012.

Why should we be concerned with this extinct sentence? Why, indeed, might we reasonably describe it as one of the most important developments in British sentencing law and penal policy in recent decades? We can do so, first, because of what it represents: the dramatic rise of preventive sentencing and risk-oriented penal policy. Second, because its effects have been dramatic: over 8,200 IPP sentences having been imposed from April 2005 to September 2012. This has contributed to the dramatic rise of the indeterminate prison population in England and Wales, which heavily outstrips those of its European neighbours.

Further, twelve years on from its creation, this preventive sentence has proved to have a very long tail. As of June 2015, over 4,600 of those sentenced to IPP remain in custody. Over 3,500 are still in prison despite having passed their tariff expiry date, the minimum period they must spend in custody before release. Campaigners have argued that delays to their release are inherently unfair: Parliament recognized this when abolishing the sentence, but did nothing to address the position of those imprisoned under the original legislation. Delays to release are often caused by prisons’ failure to provide the necessary training and treatment programmes, and delayed Parole Board hearings. The continued detention of these prisoners also presents substantial control problems for the prison governors and staff charged with their management. David Blunkett, the Home Secretary who had introduced the sentence, has publicly regretted the injustices that it had caused.

All of this might lead to us viewing the IPP sentence – its creation and its subsequent effects – as being a clear demonstration of the inability of politicians to pursue penal policies that are both reasoned and responsible. Take the politics out of penal policy: bring back the Royal Commission; imitate the Monetary Policy Committee. There is clearly something in this diagnosis. However, there are three points which we might usefully make.

As of June 2015, over 4,600 of those sentenced to IPP remain in custody. Over 3,500 are still in prison despite having passed their tariff expiry date, the minimum period they must spend in custody before release.

First, while ministers formally bear the responsibility for policy decisions, any critic must recognise that policy outputs are the result of interactions between a range of politicians, civil servants, and many other participants. The working relationship between these participants can differ greatly, and importantly, influence policy formation. As regards to ‘prisoners left behind’, while the political risk associated with releasing ‘dangerous’ offenders is clear, key civil servants also supported (and still support) this position as being entirely responsible.

Second, we must be careful in our understanding of ‘populist’ policies. For example, Lisa Miller argues that increased state interest in crime control has tended to track actual levels of violent crime. In this sense, state response to public concern is not in itself necessarily problematic, even if specific measure might be. If governments contain in their manifesto various criminal justice policy commitments, it is hard to argue that their election does not confer some level of legitimacy on future measures they may take.

Third, this does not necessarily mean that a misguided public, providing knee-jerk reactions to exceptional crimes, are part of the problem. An equally, if not more, compelling case might be made that developments such as the IPP sentence result from a deficit in meaningful public engagement. Policymakers currently operate in a realm of what I have come to term ‘illusory democratization’ – the public are a constant reference point, the idea of ‘the public’ as a driver of hasty reforms and often a perceived constraint on progressive policy change, but meaningful engagement with specific publics is an exception to the general rule. Many have convincingly argued that involving the public much more centrally in deliberations relating to crime policy is not only appropriate in a democratic society, but may lead to better outcomes in the short and longer term.

As regards to the IPP ‘prisoners left behind’, it seems unlikely that further action will be taken, notwithstanding the huge costs – financial and human – of this situation. This battle has been waged, resolution has been reached, and there is little prospect of it moving up the policy agenda once again. However, we may be approaching a fork in the road for penal policymaking more generally, with there being potential for a less punitive, more progressive path being taken. Talk is not necessarily action: how the government’s penal policy agenda unfolds in the coming months, what position the Labour opposition decides to adopt, and to what extent the localism agenda opens up space for public deliberation, remains to be seen.

Featured image credit: Barbed wire fence by Stokpic. CC-BY-2.0 via Pixabay.

The post The politics of the ‘prisoners left behind’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Seven ways to start and keep your writing going

Beginnings are tough. But if we’d only get started, our marks and words on the page can bootstrap our next moves. Marks and words on the page feed what in neuroscience is called our brain’s “perception-action” cycle. Through this biologically fundamental mechanism, we repeatedly act on the world, and then look to see what our actions have wrought in the world. The world talks back to us, telling us how close we are, or how far we are, from what we’d hoped to achieve (our goals).

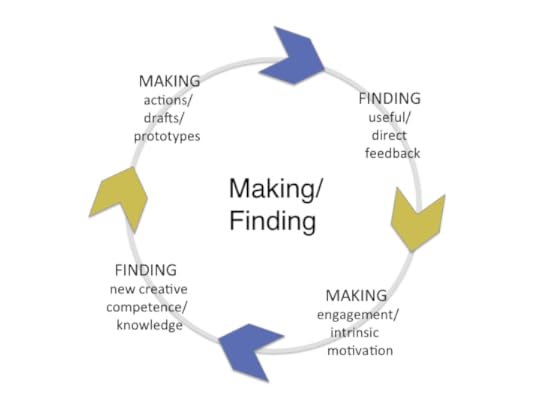

Once the words are on the page or on the screen, they’re physical objects (out there in the environment) that we can see and move. Now we’ve embarked on a three-way conversation of mind-brain-environment. We’re in a making-finding cycle, in which we are partnered with the world, rather than being isolated in our own head.

The continuing cycle of making and finding.

The continuing cycle of making and finding.By taking tangible actions in pursuit of our creative goals (making) we promote informative and sometimes surprising discoveries (finding). We can nudge and noodle and rearrange. The shapes and sounds of the letters, the syllables, the words and phrases, become tangible things that we can structure and connect, or even set aside.

But we need to make the first move — and again and again each time we try to resume our writing. So how do we do that? Here are seven pointers:

Don’t wait for inspiration (or perfection). Make writing a varied but stubborn habit. Start anywhere: beginning, middle, end, or revising what you wrote the day before.

Sneak up on writing; it doesn’t need a red carpet.

Ask your body to help. Move and keep moving through space — a walk can work wonders.

If you’re stuck, explain to a kindred spirit where you are and where you’re headed. Or back-up one or several steps, and closely resurvey the options.

Capture your emerging thoughts right away. Preserve and periodically reshuffle your growing treasure trove of ideas. They may be starting points for a new chapter, a new episode, or a plot turn.

Mind and mine the details. As Leonard Cohen observes, we seem to have an appetite for detail. But be judicious or, as Alice Munro notes, those details can become “too much of a weight.”

Be purposeful, but not overly single-minded. Experiment, experiment, experiment. In the words of Margaret Atwood: “I have no foolproof anything. There’s nothing foolproof.”

Featured image: Writing on keyboard. CC0 via Pexels.

The post Seven ways to start and keep your writing going appeared first on OUPblog.

The case for chemistry

As we look forward to Chemistry Week 2015, Peter Atkins explains why chemistry is at the heart of all science.

What is all around us, terrifies a lot of people, but adds enormously to the quality of life? Answer: chemistry. Almost everything that happens in the world, in transport, throughout agriculture and industry, to the flexing of a muscle and the framing of a thought involves chemical reactions in which one substance changes into another. Everything you touch, taste, or smell, be it natural or synthetic, has emerged from sequences of chemical reactions. Strip away chemistry and you strip away colour from fabrics and vegetation. Strip away the material products of chemistry and you return to the Stone Age (but even those stones were the result of chemical reactions). Strip away anaesthetics and you are left to grit your teeth.

Yet chemistry, despite all its positive contributions to life and, through medicine, the postponement of death, does not lie happily in the regard of many. Why is that? Like most problems, there are several contributions to the answer. Chemistry is an intricate subject, where the relative importance of influences has to be judged. There is perhaps less that is predictable in chemistry than there is in physics, and consequently more, dauntingly, to be learned. It may be that teachers, despite their best efforts, sometimes brought in to present an unfamiliar subject, lack the confidence that deep understanding gives, and transmit that discomfort to their pupils. Perhaps a syllabus is ill-conceived. Perhaps the elimination of practical demonstrations, regarded as too risky by the timidly or pragmatically wisely risk-adverse, no longer stimulate the interest that lies at the heart of commitment. Maybe the connection between a deep-seated concept and its myriad consequence in the observable world is not brought out, and interest withers on the vine. Perhaps the concepts that are the essential currency of chemistry–atom, molecule, energy, entropy–are perceived as too abstract for comfort.

Whatever the origin of distaste and fear, there are remedies. Chemistry is an intensely visual subject crying out for propagation by visualization. Computer graphics, now so extraordinarily powerful that it can conjure out of imagination the lives of dinosaurs and even dead actors, can convey with striking impact most of the central concepts of chemistry and its role in providing the infrastructure of physics and the elucidation of biology. Those who commission TV programmes should realise that if only they could overcome their prejudices, they have a rich seam of visual images that they could mine strikingly and almost endlessly.

Then there is also the stimulating intellectual pleasure of understanding that chemistry provides. A great advantage of studying (or just reading about) chemistry is that it furnishes insight that adds to the pleasure of superficial reaction. It is rather like music. A piece of music can be enjoyed at face value; but deeper enjoyment–when the mood takes you–can be achieved if you know the compositional structure. So it is with the everyday world. The world can be enjoyed at face value, but when the mood takes you the enjoyment can be deepened by knowing what is going on in the lives of its atoms. That deepened pleasure should be a part of our conveying attitudes to chemistry.

In a similar vein, as I have hinted at, chemistry lies at the heart of science and enables you to reach out for elucidation and understanding in different directions. For its explanations it draws from the deep well of physics, and through understanding chemistry you are led seamlessly into quantum theory and thermodynamics, and maybe even beyond. For its applications it is now so secure in its ability to conjure with complex matter that it elucidates the molecular mechanisms of organisms. Thus, through learning chemistry you are led seamlessly into molecular biology and all its amazing consequences.

There is much to be said for rooting out fear and distaste of chemistry and replacing it by the illumination it brings to the world, allied with a gratitude for all its artefacts. Next time you observe the autumnal changing of a leaf from green to gold, look at it with a chemist’s eye, and deepen your delight.

Featured image credit: Chemistry Lab Equipment, CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The case for chemistry appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers