Oxford University Press's Blog, page 588

November 16, 2015

Marie-Antoinette and the French Revolution

Although most historians of the French Revolution assign the French queen Marie-Antoinette a minor role in bringing about that great event, a good case can be made for her importance if we look more deeply into her politics than most scholars have. Perhaps the best way to frame the question to be resolved here is: why did Marie-Antoinette come to embody so much of what seemed so wrong about the Old Regime that her removal from power, and ultimately her execution, seemed necessary to achieve the goals of 1789?

One answer is that Marie-Antoinette, last daughter of the Empress-Queen Maria Theresa of Austria, entered France under dubious circumstances. Her marriage to the future King Louis XVI in 1770 was intended to strengthen the alliance that France had struck with Austria in 1756. Austria had been France’s most constant enemy for over two centuries, and it is not surprising that the alliance did not dispel deeply ingrained fears and resentments on both sides. In France, the Austrian alliance was widely regarded as a ruse whereby Austria was trying to weaken and possibly destroy France under the guise of friendship. Marie-Antoinette’s marriage to the next French king appeared to many observers in France as another Austrian maneuver to achieve that end, since it was widely believed that Marie-Antoinette, once she became Queen, would exercise considerable influence over her husband and act on orders sent to her from Vienna. Far from assuaging these fears by drawing attention away from Marie-Antoinette’s origins at the time of her wedding, her sponsors did everything they could to publicize her background since they were trying to reinforce the interdynastic foundations of the Franco-Austrian alliance. In particular they stressed the close mother/daughter relationship between Maria Theresa and Marie-Antoinette, who was widely represented as the heir to her mother’s stainless ‘virtue.’ That Marie-Antoinette would always be known as ‘the Austrian woman’ was thus not merely the product of her enemies’ efforts to defame her, but also the result of her sponsors’ foreign policy.

Image credit: Portrait of Marie-Antoinette of Austria by Jean-Baptiste André Gautier-Dagoty. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Portrait of Marie-Antoinette of Austria by Jean-Baptiste André Gautier-Dagoty. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Despite continuing fears of Austrian bad faith, Marie-Antoinette—who presented a young , pretty, fresh face—was immensely popular at first, especially since she allied herself politically with ‘patriot’ forces struggling against the alleged corruption and ‘despotism’ of the royal court. Her numerous acts of benevolence were widely advertised by Marie-Antoinette’s handlers, who tried to maintain her ‘virtuous’ image by steering her away from involvement in court politics. But this image could not be sustained, especially after she became Queen in 1774. For one thing, Marie-Antoinette was in reality no saint. She soon began to gamble, and her notoriously expensive taste in fashions gradually erased her early image as a princess who truly cared for the people. Moreover, her late-night partying without the King give rise to false rumors of extra-marital affairs, rumors that were abetted by Louis XVI’s well known incapacity to consummate the marriage until 1777.

Second, as Queen with influence over government appointments and court patronage, Marie-Antoinette strongly championed her favorites at the expense of those who incurred her disfavor. Her leverage with the King increased with the birth of her first two children, a daughter in 1778 and a son in 1781, and by 1783 Marie-Antoinette could claim to have had a role in recruiting three government ministers. Such interventions won her supporters, but also created enemies who feared that she would purge them from office or strip them of court favors to which they felt entitled.

Finally, once Marie-Antoinette’s brother, Joseph II, took overall command of the Austrian state following the death of Maria Theresa in 1780, he pursued an expansionist foreign policy that not only clashed with French interests, but also raised questions about the loyalty of Marie-Antoinette, since on multiple occasions Joseph asked her to garner French support for his adventures. Indeed, beginning in the early 1780s, false, but widely credited rumors circulated that Marie-Antoinette was sending enormous sums of French government money to Vienna in support of Joseph’s aggression against French allies like Turkey.

Had France not experienced major financial and diplomatic crises at the end of the 1780s, Marie-Antoinette would almost certainly have been spared her fate. But once France entered into a revolutionary spiral in 1787, three factors virtually assured that she would become one of the ensuing Revolution’s victims. First, in the wake of the King’s failure to get his financial plan adopted, Marie-Antoinette acquired more influence in the government that she had ever exercised, which at this critical moment made her seem largely responsible for the monarchy’s slow collapse. Second, far from showing support for the patriotic rising of 1789, Marie-Antoinette sided with the most reactionary members of the government, who sought to repress it. Finally, having always been ‘the Austrian woman,’ Marie-Antoinette fell under immediate suspicion for aiding and abetting France’s enemy, Austria, once war between these two allies erupted in April 1792. If Marie-Antoinette did not ’cause’ the French Revolution, her declining reputation and often unwise decisions certainly helped discredit the Old Regime and made its replacement seem necessary for the salvation of the nation.

Featured image credit: Marie Antoinette being taken to her Execution, 1794 By William Hamilton (1751-1801). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Marie-Antoinette and the French Revolution appeared first on OUPblog.

Three challenges for the International Criminal Court

The Rome Statute system is a partnership between the International Criminal Court as an institution and its governing body, the Assembly of States Parties. Both must work together in order to overcome a number of challenges, which fall within three broad themes.

First is the issue of credibility. One of the main criticisms following the conclusion of the trial of Thomas Lubanga in 2012 was that after ten years of the Court’s existence it had spent the best part of a billion euros and produced only one first instance verdict. But in the three years following, we can now count three final verdicts (in the cases against Lubanga, Mathieu Ngojolo Chui, and Germain Katanga), a further final decision on reparations in Lubanga’s case, and another judgment from the trial chamber (in the case of the Prosecutor v Jean-Pierre Bemba) due later this year. The ICC has never been busier. In the last month we have seen the arrest of Abu Tourab for crimes against cultural heritage; the Prosecutor extending the ongoing preliminary examination into the situation in Ukraine to cover the period following the Russian annexation of Crimea; and as the Court gets ready to move to its new permanent premises later this month, it will conduct four simultaneous trials for the first time. The Court has made the shift from a fledging court to a mature institution.

But there is still work to do. The ICC President Silvia Fernandez de Gurmendi has stated that expediting the trial process is her top priority. Quicker proceedings are central to the Court’s credibility; they are key to any deterrent effect the institution may have, essential to ensure justice for victims, and a vital element of a fair trial. States have a role to play here too. The Court will rise or fall on the full and timely cooperation of States. More States need to become members. There are nowhere near enough States who have entered into witness relocation or sentence enforcement agreements. There continue to be too many fugitives at large.

The second challenge facing the ICC is the question of its legitimacy. The Prosecutor continues to face criticism over selection of situations and cases. But there is a ready answer to the complaint that the Court is only investigating and prosecuting African cases; the majority of these situations have arisen from self-referrals or where non-member States such as Cote d’Ivoire (at the time) and Ukraine have accepted the Court’s ad hoc jurisdiction, while two situations were referred to the Prosecutor by the UN Security Council. Only one – Kenya – was proactively initiated by the Prosecutor, and that after the Court ruled that domestic action by the Kenyan authorities was insufficient. Some say the Court’s legitimacy will be established only on the day the Prosecutor opens a non-African situation. That is likely to come soon following the Prosecutor’s request to open an investigation into the situation in Georgia. In addition, the majority of “preliminary examinations”, i.e. the precursors to full investigations, currently underway are not in Africa. It must not be forgotten, as the ICC Prosecutor has said, that the victims of the crimes she is investigating and prosecuting are also African – and number into the tens of thousands.

There is also a key role for States in overcoming the questions around the Court’s legitimacy. The Court’s global standing is undoubtedly undermined by the fact that only two of the permanent members of the UN Security Council are members of the Court, yet the Security Council can refer situations to the Prosecutor, with no effective follow-up. As we saw in the case of Syria, members of the Security Council can veto a referral even where horrific crimes are taking place. The only answer is that every State in the world must become a member of the ICC.

The third theme focusses on ensuring realistic expectations for the Court. As Carsten Stahn says, the ICC is a “persistent object of faith”. Expectations are unrealistically high, and this will inevitably lead to disappointment. It is easy to find scapegoats: whether they be the UN Security Council that does not follow up on its referrals with money or coercion, or States Parties that refuse to pay its contributions on demand or question budgets. But the ICC, a judicial institution, inhabits a world of realpolitik — a world where ISIL exists, and where Great Powers act where and when they can to protect their interests. This is a harsh environment for the delicate plant of international justice. But it is also a world where the demand and need for accountability has never been greater.

So the challenges are immense. That said, the ICC is clearly here to stay. We should consider ourselves lucky that States were able to agree a treaty at the Rome Conference in 1998. Perhaps it would not be possible today. The Court’s current challenges are just that. They are immediate difficulties – whether financial or arising from the Court’s work – within the context of a much bigger and longer historical perspective.

Featured Image: ICC Construction, November 2014. Photo by Roman Boed. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Three challenges for the International Criminal Court appeared first on OUPblog.

5 academic books that will shape the future

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Following on from our list of academic books that changed the world, we’re looking to the future and how our current publishing could change lives and attitudes in years to come.

From books about artificial intelligence to modern Christian ethics, from books discussing the future of economics to transformative experience, we have scoured our recent titles to bring you the books that we think will shape the academic landscape in years to come. What current book or text do you feel will have a big impact on our academic future? Which academic book do you think will change lives in years to come? Share your suggestions in the comments below.

Featured image credit: ‘Day 158: Diffusion of Knowledge’, by Quinn Dombrowski, CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post 5 academic books that will shape the future appeared first on OUPblog.

November 15, 2015

What to do about whooping cough?

A century ago, pertussis—or whooping cough as it is also known—was one of those infectious diseases that most children went down with at some stage. There was a lot of suffering from the severe and prolonged bouts of coughing, and many deaths occurred, especially in very young children. But the number of cases was dramatically reduced after the introduction of the whole cell pertussis vaccine (as part of the DTP vaccine) in the 1940s, and by the 1970s there were very few cases seen in the developed world. However, adverse publicity over the high rate of side effects caused by the whole cell pertussis vaccine, some of them severe, led to development of less reactogenic acellular pertussis vaccines.

The acellular vaccine has replaced the whole cell vaccine in most of the developed world, but the number of pertussis cases has risen substantially in several countries over this time period. In 2012, there were several serious outbreaks in the United States, and the country as a whole had the highest number of pertussis cases since 1955, just a few years after introduction of the whole cell vaccine. Pertussis, in fact, is probably the only vaccine-preventable disease that is currently on the rise.

Pertussis is caused by acute respiratory infection with the bacterial pathogen called Bordetella pertussis. This bacterial pathogen is closely related to B. parapertussis, which can also cause pertussis-like disease in humans, and to B. bronchiseptica, the cause of kennel cough in dogs and respiratory disease in several other animals. When an infected person coughs or sneezes, the bacteria are spread in aerosol droplets and can infect another person when they inhale those aerosols. The bacteria then establish infection in the upper and lower respiratory tract and produce several toxins that are major players in the disease pathogenesis. One of these toxins is called the pertussis toxin, which causes the extreme leukocytosis that is characteristic of pertussis and likely contributes to fatal disease in young infants.

But with widespread vaccination against the disease, why has pertussis re-emerged? We hear about parents who refuse vaccines for their children, either because of religious beliefs or concerns about vaccine safety. Indeed, the anti-vaccine movement that has come about in recent decades probably started with the adverse publicity surrounding the whole cell pertussis vaccine in the 1970s and 1980s. However, the rate of vaccination in the United States and other developed countries is still very high, and the relatively small number of vaccine refusers cannot account for the re-emergence.

But with widespread vaccination against the disease, why has pertussis re-emerged? The most likely culprit is the acellular vaccine.

The most likely culprit is the acellular vaccine. Several studies, both in humans and animal models, have shown that this vaccine induces an inferior type of immune response that is relatively short-lived, with vaccinated individuals becoming susceptible to infection within a small number of years. Another likely contributing factor to the re-emergence of pertussis is the evolution of B. pertussis strains that can evade the immunity elicited by the acellular vaccine.

As a dramatic example, most currently circulating strains have completely lost expression of pertactin, a protein on the surface of the bacteria and one of the very few components in the acellular vaccine. Therefore, the immune response to pertactin elicited by the acellular vaccine is now virtually useless in protecting against pertussis.

So what can we do about this situation? New vaccination strategies, such as immunization of pregnant women to protect their newborns against pertussis, will be helpful, but still rely on the acellular vaccine. Going back to the whole cell vaccine might be effective in reducing the incidence of pertussis, but would probably be unacceptable to the general public because of the side effects. Most of us in the pertussis field believe that development of a new vaccine is warranted.

‘Pertussis’ by the Center for Disease Control. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Pertussis’ by the Center for Disease Control. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.At a minimum, the currently used alum adjuvant could be replaced with an alternative adjuvant that elicits a superior type of immune response, but very few such adjuvants have been approved for human use. A less reactogenic whole cell vaccine would probably be very effective, but the cause of the reactogenicity is not completely understood. Development of a new acellular vaccine formulation with different antigenic components would also likely be effective, but which components to include is not clear. Another candidate vaccine is a live attenuated strain (deficient in pertussis toxin activity and another couple of components) that has already been tested in phase 1 clinical trials with good safety and some immunogenicity. But other hurdles exist in development of a new vaccine: will vaccine manufacturing companies be willing to take on the expense of new vaccine development, and can we find a suitable population with sufficient pertussis disease and infrastructure to carry out clinical trials?

In my view, the biggest problem is our relative lack of understanding of the basics of pertussis infection, immunity, and disease. This can only be remedied by continued and increased basic research in this field, and we must try to recruit talented young investigators to pursue this research. Another problem arising from our poor understanding of pertussis pathogenesis is the complete lack of effective treatments for pertussis.

Individuals suffering from the severe and prolonged cough may seek medical advice, only to be told that there is nothing available to help them. In addition, fatalities from pertussis in young infants continue to occur despite hospitalization and intensive care. It is clear that continued basic research on this pathogen, and the disease it causes, is essential for the development of new and improved vaccines and therapies.

Image Credit: “Syringe Needle IV” by Psychonaught. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What to do about whooping cough? appeared first on OUPblog.

Katy Perry vs. William Shakespeare: Grammar showdown

Why is Katy Perry’s song title “I Kissed a Girl” grammatically correct? Did William Shakespeare know how to correctly use “who” and “whom?” Are students as terrible at using modern grammar as they think they are? We sat down with author and grammarian, Stephen Spector, to learn more about the history of English grammar and how we can get better at using it.

Featured image credit: “Childrens talk, English & Latin,” from the General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Katy Perry vs. William Shakespeare: Grammar showdown appeared first on OUPblog.

Are you a foreign affairs expert? [quiz]

From peace missions and cyber attacks, border disputes and disarmament treaties taking place across the globe, there’s no doubt that 2014 was a tumultuous and eventful year for foreign affairs and international relations.

Which government declared itself feminist in 2014? Do you know which countries spend the most on their military? Who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014?

Take the quiz below to test how well you were paying attention to the news last year, and find out whether you’re a foreign affairs expert.

Featured image credit: United Nations General Assembly Hall in the UN Headquarters by Basil D Soufi. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Are you a foreign affairs expert? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Amartya Sen on gender equality

Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, author of The Country of First Boys: And Other Essays talks to Amrita Dutta from The Indian Express about why inequality persists, his educational experiences, and his love for Sanskrit literature.

Could you talk a bit about your love for Sanskrit literature? What sense does it give you of ancient Indian culture?

Sanskrit and maths were my favourite subjects in school. When the Nobel academy asked me to donate two items to its museum, I gave them Aryabhata’s book on maths, Aryabhatiya, which I had read in Sanskrit in school, and my bicycle. The bike I had used to collect data about the famine period. I would ride to farms in Bengal and get them to open their dusty rooms where they had kept their records. I used it even more while researching on gender and inequality, when I would go to villages near Santiniketan to weigh boys and girls under the age of five. (By the time girls were five, they had fallen behind in terms of weight.) I was very proud that I had become quite good at weighing children. I had a very good research assistant, the first Santhal in her village to get a BA. On one occasion, she called me to help her weigh a teething child. And I did it without getting bitten.

I get an extraordinary positive impression of the past, which makes me very proud. I get an impression of a very cerebrally active society — never as remarkable as the Chinese in observational science — but in the philosophy of science, and the speculation of it, very high brow. On the philosophy of jurispredence. In fact, my book Idea of Justice is based on a distinction that only Sanskrit scholars make, between niti and nyaya. I think Kalidasa’s Meghdootam is extraordinarily important to understanding Indian culture. But my favourite play is Shudraka’s Mricchakatika — and it had a profound influence on my understanding of justice. I also like the Vedas, and I don’t think you have to be a passionate believer in Hindutva to like it — it is a great book. People don’t even recognise that it is not just a book on religion but also a book on human behaviour. Some of the verses are absolutely overpowering. But I don’t at all accept the view that the Vedas had interesting mathematics. It had some arithmetic puzzles, that is all.

When you started analysing women’s health and education with respect to economic growth, in the 1960s, what were the reactions?

I became interested in gender equality when I was in college at Presidency, Kolkata. Marx’s idea of false consciousness, I thought, applied to women. I also did a few papers when I was teaching in Jadavpur University. I was amazed not just at the inequality but the fact that people knew about it and took it for granted. Secondly, if you drew their attention to it, they would give you lectures about culture. I was told that this was a Western point of view, that Indian women do not think of themselves as individuals, but as an extension of their families. I had an argument at the Delhi School of Economics in the 1960s, and I said this was a form of ultimate denial of a person’s individuality, which is one of the huge possessions we have. That is the way inequality survives, by making underdogs become upholders of the inequality.

You have lived all your life on university campuses, haven’t you?

My father was a teacher, my grandfather was a teacher. One reason I haven’t retired even though I am 81 is because I love students, and they like me. Ultimately, when I look back on my life, the thing that I am happiest with is that I was a teacher.

You have written for decades on India’s education. What was your experience of school like?

I was very lucky because I went to a very nice school in Santiniketan. [Before that], I had a little over a year at St Gregory’s School in Dhaka, which was very keen on performance. After I got the Nobel, I visited the school. The headmaster said they had started a few scholarships in my name. He also said he got out my old exam scripts to inspire the students. Inspire, I said? ‘That was my hope,’ said the headmaster. But then he checked that my position in class was 33rd in a class of 36, and he wondered whether it was a good idea.

I have to say I became a relatively good student once I went to Santiniketan, where no one worried about grades, it was almost shameful to worry about them. One of my teachers described a classmate of mine: “She is quite an original thinker, even though her grades are very good.” I liked that aspect: there was no pressure to be a first boy.

Not only were there girls with me (I was in school in the 1940s) but my mother was also schooled there earlier. She was proud of the fact that she did judo there, 90 years ago. She must have been one of the first Indian women to do judo. She had a Japanese teacher, who for the first week, only taught them how to fall without hurting themselves. In some ways, the idea of what happens to those who fall seems to me not just an approach fit for judo, but for humanity at large—and for social policy.

Featured image credit: Kids school rural by antriksh. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Amartya Sen on gender equality appeared first on OUPblog.

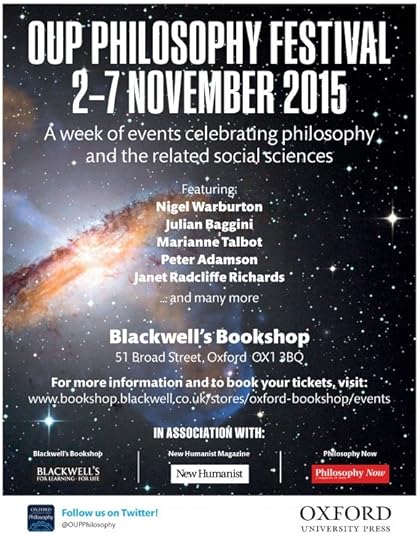

The OUP Philosophy Festival 2015

The Oxford Philosophy group at OUP teamed up with Blackwell’s Bookshop Oxford to celebrate Philosophy in all its diversity. From a philosophical balloon debate (where David Hume blew the audience away with a song about the problem of induction) to panels dealing with war, gender, and the ethics of everyday life, we explored a huge variety of philosophical problems and had fun in the process. Here’s a few snapshots of what went on last week.

OUP Philosophy Festival

For one whole week, we celebrated the power and freedom of philosophical thought with the help of Blackwell’s Bookshop. Events ranged from a philosophical balloon debate, lunchtime ‘Philosophy Bites Back’ interviews, and a full day of panel discussions, debates, and talks with some of the most prominent and well-known philosophers of our time.

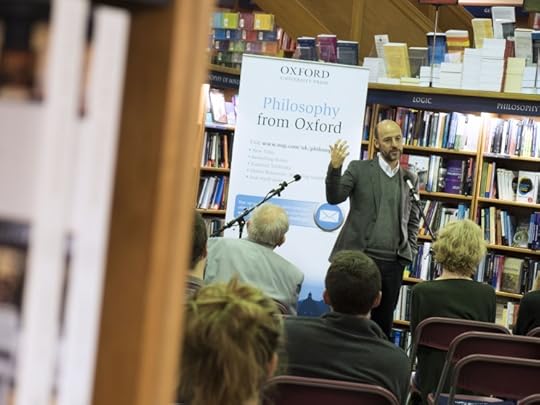

Philosophy Lunchbites

Nigel Warbuton, presenter of the hugely popular ‘Philosophy Bites’ podcasts gave a series of lunchtime interviews with a diverse range of philosophers. A much better use of a lunch-break than Buzzfeed! Here he speaks with his co-producer David Edmonds on ‘The Trolley Problem’. Photo by Katie Stileman for Oxford University Press.

The Great War Debate

In honour of the WWI centenary year we approached the much broader topics of war, conflict, justice, and killing. Nigel Biggar (left), Jeff McMahan, and Sibylle Scheipers looked back at both historical and current conflicts to shed fresh light on some of philosophy’s oldest questions: Is war ever just? Is pacifism the best way forward? Is killing in war any different from murder? Photo by Jack Campbell-Smith for Oxford University Press.

#WithoutAnyGaps

Peter Adamson, producer of the marvelous ‘History of Philosophy without any gaps’ podcast series. We linked up with Philosophy Now magazine to celebrate Peter’s series of books with OUP, based on the podcast. Photo by Jack Campbell-Smith for Oxford University Press.

The Gender Gap

What can philosophy do to narrow the gender gap? Veronique Mottier, David Papineau, and Jo Wolff covered a diverse range of topics relating to gender and inequality, with Marianne Talbot acting as chairperson. Photo by Jack Campbell-Smith for Oxford University Press.

Throw in some VSI Soapbox talks and an Oxford World’s Classics Balloon Debate, you’ve got yourself one mind-stretching week! Photo by Jack Campbell-Smith for Oxford University Press.

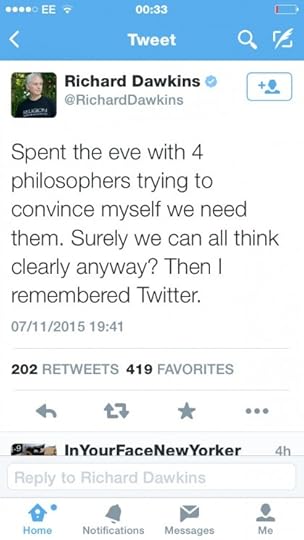

Even anti-philosophy advocate Professor Richard Dawkins was convinced… almost!

Did you attend the festival? Let us know your highlights in the comments below.

Featured image credit: ‘Galaxy.’ Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The OUP Philosophy Festival 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

November 14, 2015

A timeline of academic publishing at Oxford University Press

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Today, we present a timeline that shows the history of academic publishing at Oxford University Press.

How much do you know about the history of publishing at Oxford University Press? The first book was printed just two years after Caxton set up the first printing press in England. Fell type moulds were introduced two centuries later to make Oxford’s publishing comparable with the finest in Europe. This allowed the Press to expand and move offices several times until they ended up at their current home on Great Clarendon Street. International offices were set up, predominantly in the 20th century, although the New York office, the first outside the UK to be developed, opened in 1896. You can discover more about how academic publishing has developed in Oxford since 1478 below.

Featured image credit: Ducks in the OUP quad, image courtesy of Oxford University Press.

The post A timeline of academic publishing at Oxford University Press appeared first on OUPblog.

The AUTO- age

How readily someone may be understood when using a new word will depend on several factors: the intuitable transparency of meaning, its clarity in context, the receptiveness of the audience, and so on. It’s scarcely surprising, then, that coiners or early adopters of new terminology often exhibit a certain hesitancy. Among the early evidence cited by the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) for any particular word, it’s not uncommon to find quotations which deliberately refer to the use of the word in question, or contain some knowing, self-conscious mention of it. In them, an author might declare his or her own coinage (as, for example, at Americanism n.) or, ironically, protest against a form or usage considered to be barbarously incorrect. But the tone is more usually tentative, enquiring about a word’s legitimacy or fitness for purpose, as with the first recorded instance of autobiography n., in 1797:

Self-biography.. We are doubtful whether the latter word be legitimate: it is not very usual in English to employ hybrid words partly Saxon and partly Greek: yet autobiography would have seemed pedantic.

Despite these pedantic origins, autobiography is easily recognizable in this familiar sense, meaning ‘an account of a person’s life given by himself or herself, esp. one published in book form’. It is a relatively rare example of an enduring everyday word which uses the prefix auto- where we might substitute self- nowadays, being less concerned about, or aware of, taboos surrounding etymological miscegenation.

OED’s entry for auto-, (comb. form) contains other similar but less successful formations such as autotherapy, n., and auto-diagnosis, n. An autoburglar, n. is a curious nonce-word for ‘a person who burgles his or her own house’, and the gruesomeautocannibalism, n. links to autophagy, n., ‘the action of feeding upon oneself’. Here the use of auto- is more typically scientific, as defined at sense 1.a.:

relating to chemical, biological, or organic processes, with the sense ‘originating within or acting on the body or organism in question; self-produced; self-induced.’

In this sense, terms like autohypnosis, n. (1889) and autosuggestion, n. (1885) anticipate the advent of modern psychology and its detailed academic exploration of the human ‘self’.

Toys and curiosities

The most noticeable feature of auto- is its surge in productivity in the mid- to late-nineteenth century, which saw an explosion of vocabulary relating to ‘automatic’ technology.

Automatic, adj. has a long history relating to ‘spontaneous’ action and ‘mechanical’ contrivance, once characterized by the ingenious automaton, n.: ‘a moving device having a concealed mechanism, so it appears to operate spontaneously’. OED’s entry, first attested in 1616, elaborates:

Originally denoting various functional instruments including clocks, watches, etc., as well as moving mechanical devices made in imitation of human beings; later (from the early 19th cent.) usually restricted to figures simulating the action of living beings and widely regarded as toys or curiosities, as clockwork statues or animals, images striking the hours on timepieces, etc.

In the Victorian era, electricity and combustion engines pushed this idea of ‘self-generated movement’ beyond the realms of the quaint and the clockwork toward something altogether more dynamic and urgent, and auto- proved particularly useful in imagining and expressing this new technological potential.

Auto-converter, n., auto-valve, n., and automotor, n. are all typical of their time, applied to newly invented things ‘that function automatically’, and constituting a new sense of auto-, comb. form. Crucially, many relate to component parts not only of automatic but of automobile machinery.

‘Lord Salisbury motored’

First attested in 1876 in the sense ‘propelled by some internal mechanism, self-moving’,automobile enjoyed a short history as an adjective before acquiring its noun form. Exactly like its equivalent, motor car, automobile, n. was used throughout the 1880s to mean ‘a motorized railway or tram vehicle’, before the invention of the vehicle which it most obviously denotes. In 1895, both motor car and automobile were first used for:

A road vehicle powered by a motor (usually an internal-combustion engine), esp. one designed to carry a driver and a small number of passengers; a car.

As OED’s entry shows, the Encyclopaedia Britannica could claim in 1902 that automobilewas ‘the usual expression’ for the modern car in Europe and America.

By then, and in a strikingly short period of time, the invention had spawned a wealth ofauto- associated terminology and commentary. Among OED’s evidence, the year 1899 alone yields auto, n., autoing n., automobiling, n., and autoist n.:

1899 Boston Herald 4 July 4/7 If we must Americanise and shorten the word, why not call them ‘autos’?

1899 Milwaukee (Wisconsin) Jrnl. 19 July 5/7 Society is wondering over the tea cups as to whether it shall go ‘automobiling’, ‘autoing’, or ‘biling’.

1899 Weekly Register-call (Central City, Colorado) 17 Mar. 3/5 In London he is called ‘autoist’, ‘autocarist’ or ‘motocyclist’.

All of which, as with similar quotations at motor car n., motor v., and motoring, n., are noticeably self-conscious, conveying the level of contemporary excitement and discussion:

1895 F. R. Simms Let. in Autocar 21 Dec. 92/1, I think it is nothing but right that the ‘iron horse’, like cycling, should also have its verb. I beg to suggest motor-touring, say motouring or motoring, the verb would thus be to motour (motor). Of course it might strike us as rather funny now, if we read in the paper ‘Lord Salisbury motored’ this afternoon from Downing Street, and arrived at Paddington Station at exactly six o’clock.

1895 Daily Chron. 29 Oct. 5/1 A name has not yet been found for horseless carriages.‥ The latest suggestion we have had is ‘motor car’.

Reckless speed

Other permutations of car-related auto- words around this time include autocrime, n.,autodrome n., and automania, n.—the latter defined in 1902 by a popular car magazine,The Horseless Age, as ‘the development of a taste for reckless speed’.

The reckless speed with which such words appeared left another magazine, Motor Car World, in no doubt that ‘Automobilism will be the method of locomotion of the future!’ (cited at automobilism, n.). The method of the future, perhaps – but not quite the word. As with several similar terms, automobilism now seems forced and redundant, and is marked as ‘arch. and hist. in later use’.

The abundance of these terms, and the breathless self-referential nature of their beginnings, reflects the pace of the car’s early development and popularity. It also suggests the phenomenon of a technology accelerating and evolving more rapidly than the language needed to describe it, making an immediate and settled vocabulary elusive. A legacy of this may be the confusion that still exists with the interchangeability of auto, automobile, car, and motor car. In much the same way, multiple computing and internet terms vie for pre-eminence today.

Autos in the OED

Interestingly, the invention and mass production of the car coincided with the composition of the OED, so that the first published section of the dictionary, the 1884 fascicle covering A – ANT, arrived too early to contain many auto- related entries. As the long process of compiling the first edition progressed, these must have seemed like glaring omissions. They were ultimately gathered alongside other material that had accrued during the writing process to form the first Supplement, published when the various alphabetical sections were issued as a complete set for the first time, in 1933.

One of the many additions to the newly-revised set of auto- entries in the OED is the inclusion of auto– (comb. form 2) as a separate entry in its own right, being a shortened form of automobile, n. ‘prefixed to the names of vehicles with the sense ‘self-propelled; powered by motor’’, as in autocab and autobus. Which shows just how far automobile has travelled beyond its origins.

Image Credit: “Steyr endurance automobile, signed by driver” by Richard. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The AUTO- age appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers