Oxford University Press's Blog, page 590

November 12, 2015

“Fordham professors write your books, right?”

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Today, Kate O’Brien-Nicholson of Fordham University Press discusses one of the great misconceptions about university press publishing.

“Fordham professors write your books, right?” This is often less a question than an assumption and probably the biggest misconception about not just our, but all, university presses.

Most people have heard the phrase “publish or perish”. They seem to visualize professors endlessly researching, churning out manuscripts, and ultimately presenting them to “their” presses for publication. Fordham professors do research and produce some wonderful books but more often than not they are published by other presses. This is the case for all legitimate university presses.

Our mission is to further the values and traditions of Fordham University through the dissemination of scholarly research and ideas. These ideas can and do come in from some interesting sources.

Take Cool: How Air Conditioning Changed Everything, one of our newer titles that is enjoying global success. Author Sal Basile is a longtime professional musician and singer with the St. Patrick’s cathedral choir. Medical doctor, Michael Good, was so passionate about relatively unknown German wartime hero, Karl Plagge, that he took on The Search for Major Plagge: The Nazi Who Saved Jews. Basile made the transition from music to wider social commentary; Good opened files that had been untouched for over fifty years and spent several years interviewing survivors, demonstrating that great scholars can come from unlikely places.

One of the more familiar places for us is of course New York City, and many overlook the outstanding regional histories that university presses from New York to Hawaii publish. Whether it’s abandoned islands or the synagogues of the Lower East Side, we’ve been able to draw on the skills of not only local historians, but also professional photographers to record and present the city. Great works of scholarship can also look good on a coffee table.

And to be sure, we don’t discriminate against professors from other universities. This season, one of our featured titles is Who Can Afford to Improvise? James Baldwin and Black Music, the Lyric and the Listeners, an insightful meditation on black music and culture and James Baldwin’s centrality to black music and culture. Author, Ed Pavlić, is a professor of English and Creative Writing at University of Georgia.

Our authors come from inside and outside of academia – all over the world. Although we are extremely proud of the books that originate from within the Fordham community, there is no Fordham-biased nepotism in our offices. If your ideas have merit and your research is legitimate we want to talk about your book.

Photo by Sara Levine for Oxford University Press.

The post “Fordham professors write your books, right?” appeared first on OUPblog.

University Press Week blog tour round-up (Thursday)

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Here’s a quick round-up of topics discussed on the University Press Week blog tour on Thursday.

For the last few years, the AAUP has organized a University Press blog tour to allow readers to discover the best of university press publishing. On Thursday, their theme was “#tbt” or “Throwback Thursday” featuring the histories of various presses, some fascinating photographs and artifacts from university press history, and historical context from university press authors on today’s concerns.

20 years of Project MUSE. The MUSE team highlights articles, journals, and Lincoln-induced insanity with 20 links, one for each year of its history.

200 years of scholarly publishing. University of Minnesota Press has an extensive timeline of publishers and their foundation dates.

From printer’s blocks to 3D printing. University of Chicago Press examins the relationship between scholarship, technology, and the academic institution.

Publishing on the Prairies. Ephemera from 40 years of publishing with University of Manitoba Press.

Creating with Paper. University of Washington Press shares snaps and facts from 100 years of their publishing history.

Double-take. Duke University Press shares surprising journal covers from the past several years.

Can you put a filter on that? University of Texas Press recalls Mark Cohen’s street photography from the 1970s to today.

One book, one hundred years. University of Michigan Press examines the long history of Michigan Trees, first published in 1913.

2010’s Book Publishing Cause Célèbre. Mark Twain imposed a 100 year embargo on his autobiography, and University of California Press took on the challenge of its frenzied publication.

Judging an academic journal by its cover. University of Toronto Press reviews the evolution of its journals’ covers.

Waiting for the Second Avenue subway. Fordham University Press author Joseph B. Raskin on the history of the New York City subway system.

Be sure to look out for blog posts from Temple University Press, Columbia University Press, University of Virginia Press, Beacon Press, University of Illinois Press, Southern Illinois University Press, University Press of Kansas, Oregon State University Press, Liverpool University Press, University of Toronto Press, and Manchester University Press later today.

Featured image: Bad Pyrmont, Deutschland. Photo by Sebastian Unrau. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post University Press Week blog tour round-up (Thursday) appeared first on OUPblog.

Tracheal Intubation Guidelines

We are used to lines that guide – from those that keep our words straight on the page to those that direct planes down runways or trains along tracks. Moving from lines that guide our direction to guidelines that direct our behaviour, particularly in clinical medicine, is a very exciting time.

The science of anaesthesia (from the Greek an– and aisthēsis meaning “without feeling”) has facilitated rapid advances in surgery that have allowed the treatment of disease and suffering from hip replacements to liver transplants. Anaesthetists are frequently compared to airline pilots. Pilots are responsible for guiding travellers safely from one place to another; anaesthetists are responsible for guiding their patients safely though surgical procedures. There are other similarities too: flying and administering anaesthesia are essentially very safe and both professions are known for their safety culture. Just as the general public has a right to expect that their pilots perpetually strive to make air travel safer, patients can rest assured that anaesthetists are always working to make anaesthesia safer.

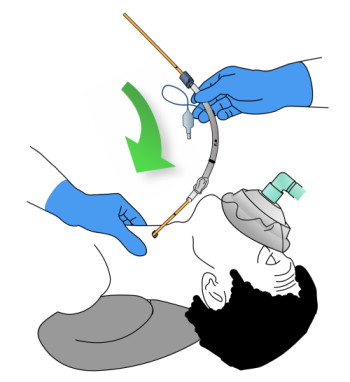

This week, a working party of the Difficult Airway Society published guidelines in the British Journal of Anaesthesia to help anaesthetists deal with a rare event that can harm patients. When a patient is having a general anaesthetic, the anaesthetist must help the patient with their breathing by keeping their airway clear for the administration of oxygen. Whilst in most situations this is straight forward, there are certain unforeseeable situations which can make this challenging.

The guidelines are an update to the original version published 11 years ago and represent the bringing together of published science, a recent massive project looking at how well airways are managed across the UK, and an understanding by the group that a cohesive and deliverable strategy was required in the emergency setting to provide best patient care. The guidelines take into account the numerous ways by which an anaesthetic procedure can be performed and address how human factors might influence performance in a crisis- an impact that can affect everyone from the most senior member of staff to the most junior.

Illustration by Christopher Thompson (via BJA)

Illustration by Christopher Thompson (via BJA)The science involved the review of over 7,000 abstracts related to tracheal intubation. That information was sifted and collated to generate a cohesive system of steps that assist the anaesthetist and direct the focus of care to the oxygenation of the patient. The guidelines even allow for the patient to be woken from anaesthesia without having had surgery should oxygenation prove challenging. Whilst this may seem strange or even unfair to some, think of it like the airline pilot who abandons take-off after starting the engines because of some previously unknown fault. I think the majority of us can see how a safety-first approach is so vitally important.

The author group is aware that there are perpetual advances in medicine and whilst they acknowledge that it is impossible to predict the future, the guidelines also provide questions to ask of new technologies that may just be becoming available or may have yet to be invented. This gives anaesthetists a way of considering how developments in anaesthetic practice and equipment provision might be adopted into the guidelines whilst maintaining the primacy of patient oxygenation.

What do the guidelines offer the non-anaesthetist? They take the complex subject of tracheal intubation and airway management and ask a simple question- what should I do if the plan I had made doesn’t work?

This series of plans (a strategy) all focused on achieving the same outcome but accepting that any part of the plan may fail can be applied to many areas of anaesthesia, medicine generally, and to complex procedures in many environments- although obviously the steps will be different!

When we take the train, we are confident that the lines (or tracks) will guide us safely to our destination. In the same regard, we hope that the updated guidelines for anaesthetists will make their patients’ journeys through surgery even safer and will provide reassurance to patients everywhere that should a difficulty occur with their breathing after the induction of anaesthesia, their anaesthetist will have a strategy to handle it.

Featured image: Track by Monsterkoi. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Tracheal Intubation Guidelines appeared first on OUPblog.

Place of the Year 2015 nominee spotlight: Nepal [quiz]

As voting for the Place of the Year 2015 continues, we would like to take a moment to highlight one of the shortlist nominees. Nepal made global headlines after a devatating earthquake ripped through the country back in April until a second earthquake of similar magnitude hit in June. Its death toll for the two events hit nearly ten thousand, leaving thousands more injured and uprooted from their homes.

Beyond earthquakes, Nepal is a highly diverse country, and there are few others that can match its wondrous flora, fauna, and landscapes. So how much do you know about Nepal? Find out in this quiz, with information pulled from Atlas of the World: Twenty-Second Edition.

Make sure to cast your vote on the shortlist for Place of the Year 2015 by 30 November.

Place of the Year 2015 shortlist

Keep checking back on the OUPblog, or follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr for regular updates and content on our Place of the Year 2015 contenders.

Headline Image Credit: Cho La Pass. Photo by VascoPlanet Photography, Nepal. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Place of the Year 2015 nominee spotlight: Nepal [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Beginning Theory at 20

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Today, Manchester University Press author Peter Barry discusses the evolution of his ground-breaking and critically-acclaimed undergraduate textbook on literary and cultural theory.

I had settled down with a pint and a ploughman’s at The Wellington in Park Road — the Friday lunchtime custom of LSU College academic staff — when Paul Gardner, our convivial HoD, asked casually, if I might be interested in devising an undergraduate course in literary theory. Being young and naïve (it was around 1982), I expressed enthusiasm, and Paul said, as if casually, ‘Could you do it for Monday?’ My weekend ended there, and on the Monday I gave him the outline syllabus for a theory course. It went through a fast-track validation route that Paul had set up, and by the following September I was teaching it, as part of a new degree scheme. It was the first undergraduate course in literary theory in the UK, and in due course (pun intended), it became Beginning Theory.

In 1992, I encountered a woman just outside Sussex University, on the platform of Falmer Station. She was reading one of the two (postgraduate) student-directed books about literary theory which then existed. She was in tears, and I had the distinct thought that it must be possible to write about theory without provoking that reaction. It’s a bizarre idea, I know, and (with the obvious exception of Terry Eagleton, who instigated it) it never really caught on, except with (at most) half a dozen people worldwide.

When I write, I talk to myself (which is OK, so long as you say the right things). One of the things I often tell myself is ‘It’s not extreme enough – make it more extreme’. When I come back to a piece that I thought I had pushed to an extreme, it usually feels more normative than it did when I was writing it, but (I hope) it never just feels standard, run-of-the-mill academic normal. Being extreme in the context of literary theory means using ordinary language, explaining fully, finding the example that works, then working it all the way through, and never pretending to be a full believer in what I only half believe.

Anita Roy, who was the MUP commissioning editor in the early 1990s, sent me the bundle of readers’ reports, saying that I should use anything in them that seemed helpful. (All of them pretty snooty about the possibility (perhaps even the desirability) of writing about literary theory in a way that students can understand.) She came to LSU shortly afterwards at my invitation to do a talk to the Humanities Research Group, which I had set up with Dr Jane McDermid (now Reader in History at Southampton University). No official letter had yet been sent, and I had assumed that MUP wasn’t going to do the book. During the meal afterwards, at a pizza house in Rochester Place, Anita Roy said something that made me ask in surprise ‘Do you mean you’re commissioning it?’ and she looked puzzled and said, yes, of course we are. So that was that – I’ve been with MUP ever since, and have never wanted to be anywhere else.

Anyone who writes a high-selling academic book has to pay a price – it is the sin for which there is no absolution. But when I lecture, and I see people nodding with understanding, I feel that I can want nothing better. As a writer and teacher, the only quality I value is clarity; as Ezra Pound said, clarity is the writer’s only morality. I have no interest in accolades from professors, and the ones I like come from students worldwide in emails. The nicest always tell the same basic story: I was enjoying English, and then in Year 2 we were hit by the theory course, and I was about to give up the subject – tears are often mentioned – then someone told me about your book. There was one email I wanted to have quoted on the front cover; it was from America and it read in full ‘This book is the real fucking dope – I’m pissed my profs didn’t tell me about it sooner’. Others come from readers of humbling erudition; one explained the three transmission errors I had made in a single-line Latin quotation. We silently corrected them, and I imagined the pain my Latin teacher would have felt on seeing them. As we have gone through numerous re-prints over twenty years, errors we corrected a decade earlier sometimes rise from the dead to haunt us, going unnoticed through two or three reprints before we realise they are back, and need to be weeded out all over again.

At a deeper level, revising and updating a book of one’s own seems straight-forward, in theory, but in practice re-entering the mind-set of a quarter of a century ago is nearly impossible. I feel about for the way back into a certain line of argument, but am often defeated. It’s easier to write a new book than to revise an old one, though I am pressing on anyway towards the goal of the fourth edition. I’m sometimes asked how it feels to have written a book that everyone seems to know about, and I say that it feels nice. All I mean is that I like the fact that people know my name – it’s as elemental as that. Sometimes I have to confess that I’m not the author of illustrated books with titles like How to Photograph Your Girlfriend, and I imagine that my namesake may occasionally have to explain that he is not responsible for the faults of Beginning Theory. I remain extremely grateful for the 20-year support and friendship of Commissioning Editor Matthew Frost at MUP, and likewise that of John McLeod, ex-LSU, and now Prof at Leeds University, who is co-editor of the Beginnings series. Being from Liverpool, my lifelong ambition was to be a paperback writer, and I’m pleased that it has happened. Also, I remain constantly optimistic that, as it says in the Beatles song, ‘I’ll be writing more in a week or two’.

On Friday last week, more than thirty years after that lunchtime in The Wellington (still naïve, but no longer young), I got an email from MUP inviting me to do a blog piece. I had already agreed to do it before scrolling down to the punch-line, which read, as I should have anticipated, ‘But we will need it by Monday’.

The post Beginning Theory at 20 appeared first on OUPblog.

November 11, 2015

University Press Week blog tour round-up (Wednesday)

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Here’s a quick round-up of topics discussed on the University Press Week blog tour on Wednesday.

For the last few years, the AAUP has organized a University Press blog tour to allow readers to discover the best of university press publishing. On Wednesday, their theme was “Design” featuring interviews with designers, examinations of the evolution of design, and parsing the process itself.

“Like a lot of us, I stumbled into publishing.” Interview with Northwestern University Press Art Director Marianne Jankowski.

The many layers of book design. Princeton University Press launched their own tumblr on design.

Design through the decades. MIT Press has a video that illustrates the trends in design through MIT Press covers.

“To each idea its book, and to each book its cover.” Karl Janssen, Art Director and Webmaster of University Press of Kansas, discusses book cover design.

How structure becomes design. Georgetown University Press Languages Director Hope LeGro weighs in to discuss how an acquisitions editor prepares a language textbook manuscript and accompanying materials to move into design.

How can you be both plain and fancy? Syracuse University Press interviews designer Lynn Wilcox.

“The words themselves are our art direction.” Stanford University Press interviews the husband-wife designer duo Anne Jordan and Mitch Goldstein.

Statistics are sexy. Harvard University Press blog chats with HUP Senior Book Designer Jill Breitbarth about one of her recent projects, a forthcoming book from Stephen M. Stigler.

Free fonts. Athabasca University Press dives into the designer’s toolbox.

Typography only. Yale University Press book designers talk cover design without images.

Be sure to look out for blog posts from Project MUSE, University of Minnesota Press, University of Chicago Press, University of Manitoba Press, University of Washington Press, Duke University Press, University of Texas Press, University of Michigan Press, Minnesota Historical Society Press, University of California Press, University of Toronto Press, and Fordham University Press later today.

Featured image: Landscape. Photo by Larry Chen. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post University Press Week blog tour round-up (Wednesday) appeared first on OUPblog.

You’ll be a man, my son. Part 1

The title will probably be recognized at once: it is part of the last line of Kipling’s poem “If.” Unfortunately, Kipling’s only son John never became a man; he was killed in 1918 at the age of eighteen, a casualty of his father’s overblown patriotism. Our chances to reach consensus on the origin of the word man are not particularly high either.

John Kipling, Rudyard Kipling’s only son, who was not given the chance to live to his father’s prophecy “Yours is the earth and everything that’s in it.”

John Kipling, Rudyard Kipling’s only son, who was not given the chance to live to his father’s prophecy “Yours is the earth and everything that’s in it.”Like a host of other researchers, I have my pet theory concerning the origin of man and made it public several years ago, but the unsuspecting public has passed it by (or perhaps the malevolent world only feigned indifference). This circumstance and the habit of the Internet to recycle with pomp and authority discarded explanations would not have induced me to fight (re-fight) an old battle, but it so happened that, while looking through my post on the etymology of wife, I noticed a question about Latin vir “man,” which I have never answered, and a suggestion that the word wife might have something to do with the idea of covering the female during sex rather than hiding the bride’s face under a veil during the wedding ceremony. This conjecture seems unlikely to me not only because it has no support among the words for wife in the languages of the world (I cannot find an analog of the woman being called this for the reason proposed) but also for linguistic reasons; it fails to account for the neuter gender of the ancient word. I should also repeat what I have said many times in the past. Comments are always welcome. However, when they are offered long after the appearance of the post but appear on the page for that post, I may never see them, for, obviously, in preparation for my monthly “gleanings” I cannot be expected to look through more than five hundred essays on the off-chance that something new has turned up somewhere. The hayrick is huge, and the needle is all but invisible. So please, whatever your suggestions may be, use the rubric “Comments” after the most recent posts.

A bride, not a woman, and not neuter.

A bride, not a woman, and not neuter.Before coming to the point (and, among other things, discussing the query about Latin vir), I should repeat very briefly what I once wrote about wife. Wife at one time meant “woman,” not “female spouse,” as it still does in midwife, fishwife, old wives’ tales, and the like. Numerous etymologies of this word have been offered, but none of them could explain why the noun denoting “female” was neuter, as German Weib “woman” still is: das Weib. Without overcoming this grammatical difficulty, we will get nowhere, so I suggested that our word once designated a group of people belonging to a woman’s kin and containing the root of the pronoun we and a suffix (Indo-European –bh, as in the name of the Scandinavian family goddess Sif). Later, I reasoned, the word began to be applied to an individual female but retained the gender of the ancient collective noun.

Details can be found in the old post and in my long 2011 article. Here they are relevant only in so far as my reconstruction of the history of man bears some resemblance to what I think was the origin of wife. For comparison, I can refer to the scholarship on the word god (see a series of fairly recent posts devoted to it). In Germanic, only the plural (neuter plural!) gods existed. At one time, the gods were viewed as a multitude; the concept of a singular god dates to a much later period. The Scandinavians distinguished between two divine families: the Æsir and the Vanir. They had no trouble calling Thor an As and Frey a Van (the Icelandic spelling has been simplified) and did not need a term for “god in general.”

Words like man and woman testify to a high level of abstraction. Boy and girl, male and female are different. When a baby comes into the world, its sex must be defined, so that a label is needed. J. Hammond Trumbull, an American anthropological linguist of the past epoch, noted that man as an individual homo is untranslatable into any Native American language, for “distinction is always made between native and foreigner, chief and counselor, male and female,” and so on. From the modern point of view, the world of our ancestors was overclassified and tended to avoid abstractions. Therefore, while reading old literature, we notice with surprise or amusement that everything and everybody has a name. A sword, a cauldron, a rock—nothing remained nameless. It was practically impossible to say “A tall farmer carrying an ax walked past a lake with his son,” for one expected something like: “A tall man called William carried the ax Hewer and was seen walking with his son Jack past Lake Fishpond.” Although man did once refer to a homo (as follows even from the English word woman, originally a compound: wif + man), this must have been a later development. In searching for the etymology of man, we should have a clear picture of what we are trying to find.

Not only Germanic man presents great difficulties. No hypothesis on the origin of Greek ánthropos, familiar to us from anthropology “the study of man,” and Russian chelovek (stress on the last syllable) can be called fully satisfactory. Latin vir fared better. Vir is most likely related to vis “force, strength; a large quantity,” yet that is all we can say with certainty. Incidentally, vir had a Germanic cognate, and its traces are still discernible in the noun world, an ancient compound wer + eald “the time of man.” Under the circumstances that have not been fully clarified, the temporal reference gave way to the spatial one, namely “the place where people live.” A more exotic compound is werewolf “man-wolf,” a popular character from old stories, someone who assumes a wolf’s shape and behaves like a wolf. Those interested in this subject should consult works on lycanthropy (Greek lycos means “wolf,” and ánthropos has been mentioned above). Only homo seems to be transparent. Language historians are agreed that homo is akin to Latin humus “ground.” If this conclusion is correct, the word reflects the notion that humans were made from soil.

Did Mannus look like one of those?

Did Mannus look like one of those?Engl. man has related forms in all the Germanic and numerous non-Germanic Indo-European languages. The most interesting of them is the name Mannus, mentioned by Tacitus, according to whom Mannus was a god venerated by the “Teutons.” Unfortunately, no myth about this deity has come down to us, but Tacitus is a reliable source. Also, it is possible that such tribal Germanic names as Alemanni and Marcomanni retained the vestiges of the cult of Mannus (more tangible traces of this cult have also been found), but perhaps manni is the Latinized plural of the word for “man.” In any case, Mannus cannot be ignored in the search for the origin of the word man. The grammatical affiliation of that word presents serious difficulties. Here we should only take into account the circumstance that in the Old Germanic languages every noun belonged to some declension. Occasionally the forms vacillated between two declensions, but the recorded forms of man show traces of four or even five declensions. Apparently, the speakers felt most uncertain about how to use that noun.

The best-known Germanic word for “man” was guma, which sounds like Latin homo, and indeed the two must have been related. Is there a connection between homo ~ guma and man? An old etymology combined them and produced the protoform ghmonon, a good but rather improbable hybrid. A hundred and fifty years ago scholars often yielded to what might be called the Indo-European temptation. Thus, girl, probably a rather late borrowing from Low German, in which it had no respectable parentage, was once traced to ghwerghw, a cross between the German noun and Greek parthénos “woman.” One shudders at the thought that the primitive ghmonon called his baby girl ghwerghw. But then what do we know?

To be continued.

Image credits: (1) Old Slavic pagan stone statue. (c) tiler84 via iStock. (2) John Lockwood Kipling and Rudyard Kipling circa 1890. University of Sussex Library Special Collections. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) The Bride by Gertrude Kasebier, 1902. Public domain via WikiArt.

The post You’ll be a man, my son. Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

‘Tomorrow I’ll start living': Martial on priorities

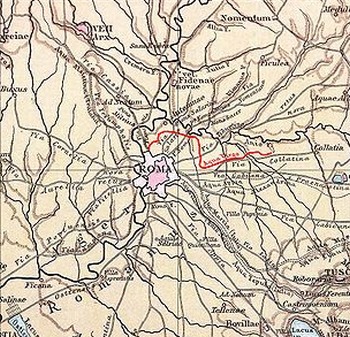

‘Dear Martial’ – what a strange coincidence that Martial’s soul-mate, who leads the life he himself dreams of living, is called ‘Julius Martial’. In our selection we meet him first at 1.107, playfully teasing the poet that he ought to write “something big; you’re such a slacker”; at the start of book 3, JMa’s is ‘a name that’s constantly on my lips’ (3.5), and the welcome at his lovely suburban villa on the Janiculan Hill 4.64 is so warm, ‘you will think the place is yours’. Let’s play along and pretend he’s a wealthy friend and patron (and for all we know, he really was). His resources don’t make the daily rituals of the capital – social calls, legal advocacy – any less wearisome than they are for his favourite client; if only they could live a life of proper leisure, and spend every day “going out for a drive, some plays, some little books, the Campus, the portico, a bit of shade, the Virgo, the baths.”

This catalogue of refreshing amenities presents the imperial capital at its most charming. The Aqua Virgo, built by Augustus’ right-hand man Agrippa, brought water in from ten miles or so to the north; it snaked into town by way of the Gardens of Lucullus on the Pincian and ran overground on arches into the Campus Martius (‘the Campus’). The Campus was outside the city proper and a traditional venue for sport and leisure. Martial’s ‘portico’ is likely the one, begun by Agrippa’s sister Vipsania, where a child was killed by a falling icicle at 4.18; it was near the Virgo, and its stone was ‘slippery-wet from the constant runoff’ where it leaked. By Martial’s time the Virgo mostly served private households, who paid for the privilege (Martial tries to finagle free access to the Marcia at 9.18).

Shade and running water were as crucial to a tolerable life in the Roman summer as they are today, and naturally our poet reckons ‘some little books’ every bit as indispensable (cf. 2.48’s ‘just a few books – provided I get to pick them’); the Latin word, libellus, is what Martial calls his own books, just as Catullus had his.

A map of The Aqua Virgo (in red) transporting water into the city. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

A map of The Aqua Virgo (in red) transporting water into the city. Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsRomans enjoyed a carriage-ride, ideally out to their little or not-so-little places in the country (8.62, 12.57; and cf. the loaded SUV of 3.47, faking the good life by stocking up on farm produce at the supermarket on the way). Which of ‘the baths’ one patronised was a matter of individual preference and whim (3.20) – emperors kept building more (Book of Shows 2, 2.48), and there was more to them than simply keeping clean. From the baths one might segue naturally into dinner, perhaps playing it by ear depending on present company (6.53), though tiresome individuals might try to blag invitations from the unwary (11.77, Vacerra in the public toilets).

Martial’s wish that they could step back from the rat-race – ‘What kind of person knows how to live, but keeps putting it off?’ – is echoed later in the book (5.58): “‘Tomorrow I’ll start living’, you say, Postumus: ‘always tomorrow…'”

Postumus is a frequent target of horrible accusations (follow him through the index) but this poem’s conclusion, ‘Anyone with sense started living yesterday’, throws the reader back to 5.20 and Team Martial’s failure to get its own priorities straight.

Image Credit: Roman Bath by crjsmit. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post ‘Tomorrow I’ll start living': Martial on priorities appeared first on OUPblog.

Research for the developing world: Moving from development studies toward global science

Research for the developing world is the application of science to the challenges facing poor people and places.

In the 20th century, such research fell into two camps: one rooted in the traditions of social sciences, such as sociology & political science coalescing around development studies, and one rooted in the natural sciences, such as tropical medicine and agriculture. The former took developing countries as a subject of study, the latter as a setting for application. The former elaborated distinct theories and concepts, providing unique explanations distinct from those used for advanced economies. The latter remained grounded in universal theories and concepts, such as human physiology and soil morphology, to deal with distinct phenomena–such as pathogens and plants–that simply did not exist in temperate climates.

The intellectual landscape has now moved beyond this quaint dichotomy.

In the first instance, a more diverse set of disciplines contribute to understanding human societies and aspirations to improve them. Business schools & marketing, design & engineering, and ICTs & digital technologies joined the established curricula of ideas for enhancing the quality of life in the developing world. These fields chart a middle course, rallying concepts of ‘what works’ elsewhere, while the remaining focused on reaching the ‘bottom billion.’

In the second instance, the camps of social and natural sciences have themselves transformed. Whereas development economics was once a distinct discipline for poor places, the field is increasingly integrated across borders: applying insights from behavioural science, grappling with asymmetric information, and fostering entrepreneurship and employment. Similarly, agriculture is undergoing a global revolution driven by the potentials for geo-positioning, real-time market information, and precision farming. Molecular biology, genetics, and data analytics pushed the leading edge of health and agricultural research upstream into the laboratory and hackathons.

Image credit: Agriculture by StateofIsrael. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Agriculture by StateofIsrael. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Consequently, research for the developing world became less predicated on exceptionalism, field experience, and career-long specialization.

A previous generation of scholars and practitioners elaborated ideas and applications for a developing world viewed as distinct from the global north and somehow common within itself. Yet constraints and opportunities vary across Bolivia and Botswana, Egypt and Ethiopia, or Nigeria and Nepal. Our theories for explaining continuity and change in human society must account for such diversity, whether through consilience or epistemic pluralism. The developing world may share a commonality of constrained resources–capital, technology, or talent–but such initial conditions do not necessitate a separate set of concepts to explain social and natural change. Understanding of development is richer for drawing from multiple disciplines and methods.

Research for the developing world is increasingly embedded in global science, rather than set apart from it. Yet there is a cost. Scholars and practitioners are subject to similar pressures that shape research careers elsewhere. The credibility of a young academic is less based on her or his field experience accompanying people experiencing development, and more on amassing peer-reviewed publications in highly-cited journals. In establishing a professional reputation, it is a liability to spend substantial time in the field or collaborate with less-proficient colleagues abroad. More recent performance assessment schemes do consider the ‘impact’ of a scholar’s work on real-world policy and practice, yet these measures do not weigh as heavily as criteria of academic excellence.

Looking back, research jobs and funding became increasingly open to specialists who wish to benefit people in Africa or Asia, while maintaining a career in their area of expertise. Looking forward, the rise of international collaboration, through such programs as Newton Fund or Horizon 2020, is altering research in and by developing world. Advanced economies seek to tap scientific expertise anywhere, while developing countries seek to plug into global science.

Research for the developing world is at a crossroads: fading as foreign aid contributes an increasingly modest share of science funding in the global south, yet thriving with efforts to address ‘one world’ global challenges. New programs promise to improve human well-being through knowledge and innovation on pandemic disease, climate change, food security, intrastate violence, forced migration, and more. Such programs are driven by funders in the global north and south, such as science granting councils, as well as international coalitions such as Belmont Forum, Global Resilience Partnership and Saving Lives at Birth.

Beyond their stated goals of creating a better world, such programs alter the opportunities and incentives to pursue a research career. History provides vital insights into these unintended consequences. At this crossroads, ‘research for the developing world’ is being subsumed under the consensus of peer review and global scholarship. Yet research for ‘global challenges’ deserves funding that is fit-for-purpose: one that encourages careers with substantial ambition to achieve transformative change over the coming decades.

Featured image credit: Earth by Kevin M. Gill. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Research for the developing world: Moving from development studies toward global science appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten things you never knew about Elizabeth Stuart, ‘the Winter Queen’

Elizabeth Stuart (1596–1662) was the charismatic daughter of King James VI of Scotland (later James I of England) and Anna of Denmark. She married the Calvinist Frederick V, Elector Palatine, at age 16, and lived happily in Heidelberg, Germany, for six years before being crowned Queen of Bohemia at 23 and moving to Prague. Although she was deposed by Catholic forces after barely a year in power and experiencing only one winter in Prague – hence the soubriquet ‘Winter Queen’ – she never relinquished the title, establishing a court in exile in The Hague, Holland. From here, the outlawed couple fought frantic military and diplomatic campaigns to regain the Palatinate, their lands in Germany which had been overtaken by the Spanish. Although she lived out most of her life in exile, only returning to England in May 1661, her grandson would later ascend the British throne as George I.

The entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography for Elizabeth Stuart gives two dates for her birthday: 16 and 19 August 1596. Her husband’s birthday wishes in a postscript of 1621 establishes it beyond question that the date is 29 August (19 August Old Style). In light of this recent scholarship, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography will update their entry in 2016. Here are ten other things you never knew about her.

Monkeys, parrots, and dogs. According to the household accounts of her childhood, Elizabeth spent 8 shillings and 3 pence on ‘strewing herbs, and cotton to make beds for her grace’s monkeys’, ‘mending parrot’s cages’, and ‘for shearing her grace’s rough dog.’

Gerard van Honthorst. Portrait of Elizabeth Stuart, 1635. Private collection by courtesy of Hoogsteder & Hoogsteder, The Hague. Used with permission.

Gerard van Honthorst. Portrait of Elizabeth Stuart, 1635. Private collection by courtesy of Hoogsteder & Hoogsteder, The Hague. Used with permission.Gunpowder, treason, and plot. Guy Fawkes and his cronies weren’t just trying to assassinate King James and Henry, Prince of Wales. Their plan involved abducting Elizabeth, marrying her off, and turning her into a Catholic puppet queen.

Brotherly love. In 1612, when Henry, Prince of Wales, was dying of typhoid, Elizabeth disguised herself as a servant in a vain attempt to gain access to his sick chamber. Fifty years later, she was interred next to Henry in Westminster Abbey, as she had stipulated in her Will.

Daddy’s credit card. Her post-nuptial journey from Margate to Heidelberg took 58 days. By the time she arrived in the capital of the Lower Palatinate, she had given away all her jewels as gifts. King James had to send an ambassador to retrieve the Crown Jewels from her ladies-in-waiting who had left her service.

Cannon fire. The Battle at White Mountain on 8 November 1620 did not take Frederick and Elizabeth by surprise. In letters written from the battlefields of Bohemia, Frederick had been trying to persuade his fearless wife to leave the capital ever since the beginning of September. She steadfastly refused to leave Prague and abandon her subjects. Her secretary Sir Francis Nethersole wrote, ‘we can in this towne heare the Canon play day and night, which were enough to fright another Queene. Her Majesty is nothing troubled therewith’. In the end Elizabeth, eight months pregnant, had to be dragged out by two English ambassadors.

Father complex. She referred to Maurice, Prince of Orange, who had once asked for her hand as a second father. She had a troubled relationship with her own father, King James. He negotiated with her Catholic enemies, but she wanted him to unreservedly engage in battle: ‘I remember neuer to haue read in the Chronicles of my ancestours, that anie king of England gott anie good by treaties but most commonlie lost by them, and on the contrarie by warrs made always good peaces.’ When James sent her a portrait of himself in a casket full of diamonds, she threw the diamonds on the floor shouting how she wished he had sent her soldiers instead.

Gerard van Honthorst. Portrait of Elizabeth Stuart, after 1642. Private collection by courtesy of Hoogsteder & Hoogsteder, The Hague. Used with permission.

Gerard van Honthorst. Portrait of Elizabeth Stuart, after 1642. Private collection by courtesy of Hoogsteder & Hoogsteder, The Hague. Used with permission.Resemblance to her godmother. Elizabeth traded on her relationship with Queen Elizabeth I, plucking out her hair to have the same coiffure as her late godmother, wearing her iconic string of pearls and other jewellery that she had inherited, and mimicking her signature when signing letters. One deranged man, John Lambert, actually believed Elizabeth I had taken possession of the body of the Queen of Bohemia. He stabbed her minister Thomas Scott to death to get closer to his beloved Virgin Queen.

Cult of widowhood. After her husband’s death in 1632, the English exchequer paid £1,000 to redecorate the widowed queen’s stately home – ‘all the rooms in the Queen’s house, walls, beds and all, covered with black’. For forty years thereafter all her letters were sealed with black wax and black floss, like mourning cards.

All or nothing. Elizabeth’s stubbornness and political machinations obstructed many peace negotiations, for instance in 1636. Emperor Ferdinand offered her family a compromise: half the Palatinate. It was a kind offer, coming from a man whose Crown they had usurped back in 1619. She insisted on ‘tout ou rien’, however, and persuaded her brother’s ambassador, the Earl of Arundel, to walk away. In 1648 her son would accept the same offer.

Secret codes. She wrote hundreds of letters in cipher code, employing at least seven keys during her lifetime, encrypting her letters herself with hieroglyphics and polyalphabetic substitution systems. Cipher codes were meant to protect her letters from prying eyes – she did everything in her power to stop her father, the Duke of Buckingham, and later her brother from reading the bellicose plans she was devising to undermine the Stuart Crown’s conciliatory tactics.

Whatever happened, her monkey Jack, who had accompanied her to Heidelberg and Prague, still sat beside her in The Hague when she wrote her letters as ‘knauish as euer he was.’

Featured headline image: Heidelberg Castle by MyPentaxK200d. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ten things you never knew about Elizabeth Stuart, ‘the Winter Queen’ appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers