Oxford University Press's Blog, page 587

November 17, 2015

The flirtatious friendship of Alexander Hamilton and Angelica Church hits Broadway

Theatergoers have been dazzled by the new Broadway hit Hamilton, and not just by its titular lead: the Schuyler women often steal the show. While Alexander Hamilton’s wife Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton provides heart and pathos, her sister Angelica Schuyler Church is sassy, witty, and flirtatious. Ultimately Angelica is the more interesting, complex character in both the musical and the historical record. Her loving friendship with Alexander Hamilton, not to mention other leading men of the era, offers a window into the workings of mixed-sex friendships in America’s founding era.

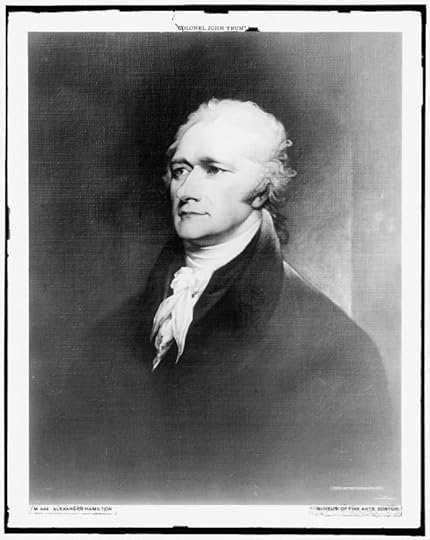

Hamilton writer and star Lin-Manuel Miranda draws on both Ron Chernow’s biography and Angelica’s letters to paint a largely accurate picture of her. Even the rosy pink gown that actress Elise Goldsberry wears in the musical mirrors the 1785 John Trumbull portrait of Angelica. Miranda does take some license, however: we never meet Angelica’s British husband, John Barker Church, nor does her elopement with him in 1777 come up. She was married, to a man both rich and dull, when she first met Hamilton.

That Angelica was a married woman actually made her friendship with Hamilton safer from public scrutiny, as did Hamilton’s marriage to her sister Eliza in 1780. Friendships between men and women were subject to public scrutiny and worries about sexual improprieties, so broadening a friendship from a pair to a set of spouses was helpful. These factors may have emboldened both Alexander and Angelica to express affection for one another with more intensity than most friends.

“Portrait of Mrs. John Barker Church (Angelica Schuyler), Son Philip, and Servant” by John Trumbull. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Portrait of Mrs. John Barker Church (Angelica Schuyler), Son Philip, and Servant” by John Trumbull. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Their relationship as siblings-in-law also allowed for more fulsome language, since such in-laws were treated in many ways like blood relations—who often expressed love for one another without generating any suspicions. Angelica wrote Alexander affectionate letters and joked with Eliza that she should share her husband. “I love him very much and if you were as generous as the Old Romans,” she wrote Eliza in 1794, “you would lend him to me for a while.” In the musical, Miranda riffs on this line by having Angelica sing to Eliza, “I’m just sayin’, if you really loved me, you would share him.” While Angelica’s letters to Alexander are not any more affectionate than other letters between sisters and brothers-in-law, it’s possible that Angelica had romantic feelings for him. Miranda imagines this to be the case, and Angelica sings that “when I fantasize at night/It’s Alexander’s eyes…”

Alexander’s letters to Angelica are clearly flirtatious, but whether this was playful or a sign of romance is impossible to know. He wrote to her in 1787 that “I seldom write to a lady without fancying the relation of lover and mistress,” which was not standard fare in letters between friends or siblings. In one song, “Take a Break,” Miranda plays with this uncertainty as Angelica asks Alexander whether he had romantic intent behind a phrase in letter. While Angelica and Alexander may not have had this precise conversation, many friends of the opposite sex were confused about their feelings for one another.

“Alexander Hamilton” by John Trumbull. Public domain via Library of Congress.

“Alexander Hamilton” by John Trumbull. Public domain via Library of Congress.The close relationship between Angelica and Alexander did generate gossip that the two were having an affair, and the musical avoids a clear answer here. An earlier version of the musical script, according to Miranda’s twitter, had Thomas Jefferson teasing Hamilton about Angelica. Jefferson asks Hamilton to pass along greetings to Angelica, then in England, “since you’re so interested in foreign affairs…” The final musical, however, likely comes very close to the historical reality: Angelica and Alexander were dear friends and may well have been in love. It’s unlikely, given Eliza and Angelica’s lifelong closeness, that Angelica and Alexander had an affair. We can never know for sure: either way, sexual intimacy was not the defining characteristic of their relationship.

Angelica Schuyler Church was a well-traveled and intelligent woman who befriended many men in her lifetime, including Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette. Jefferson told her that if their artist friend John Trumbull were to paint their friendship, “it would be something out of the common line.” It is only fitting that her life, feelings, and friendships would be key to telling her friend and brother-in-law Alexander Hamilton’s story on Broadway today.

Featured image: “US 10 Dollar Bill – Series 2004A.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The flirtatious friendship of Alexander Hamilton and Angelica Church hits Broadway appeared first on OUPblog.

An educated fury: faith and doubt

Novelists are used to their characters getting away from them. Tolstoy once complained that Katyusha Maslova was “dictating” her actions to him as he wrestled with the plot of his last novel, Resurrection. There was a story that after reading Mikhail Sholokhov’s And Quiet Flows the Don, Stalin praised the work but advised the author to “convince” the main character, Melekhov, to stop loafing about and start serving in the Red Army. At their next meeting, Sholokhov said to Stalin, “I tried to do that, but Melekhov does not want it.”

The challenge of controlling the material is one that historians also face, even if the stakes are generally lower. “It does seem,” Carl Becker once protested, “that people living in past times often act as if the convenience of the future historian were a matter of negligible importance.” When I began a project on the ethical roots of unbelief, I had a clear sense of what I was going to argue. It would be a history of conscience in which morality triumphs over faith. Kant, and his moral law within, would be the model. But the sources did not want it.

A central figure in my project, and a vital link between the Reformation and the Enlightenment, was a Protestant philosopher called Pierre Bayle (1647-1706). Bayle enjoyed a legendary status in the eighteenth century as a kind of philosophical assassin, a tireless and agile critic of religious authority. He was the first European thinker to suggest that a society of benevolent atheists might be possible. He offended nearly everybody when he said that religion is no safeguard of peace and social harmony. Bayle was a rigorous and often gleeful destroyer, and his skepticism was rooted in precisely the kind of moral passion that I was looking for. I had my bridge between Luther and Kant. But the closer I got to this fierce and redoubtable thinker, the more he rebelled from the role of a secular icon. Bayle was a believer. The demolition man of the seventeenth century was a man of prayer.

With one eye on the future, on what Hume or Diderot would do with his X-rated portfolio, I had been slow to grasp the intensity of Bayle’s troubled piety. The truth was that he attacked a persecuting church in the name of its “adorable Founder.” He was a master of innuendo and corrosive ridicule, but there were some things he did not joke about. Bayle’s enduring conviction, as he savaged the reputation of a theologian such as Augustine, was that “God is merciful.” For Bayle, a theology of persecution, stitched together with verses from the New Testament, was not so much a failure of logic or interpretive skill: it was blasphemy. My thesis took a religious turn.

As I learned to look back, toward motives and origins, rather than forward toward outcomes, a subversive theory began to materialize: the nemesis of Christian orthodoxy is Christian spirituality itself. Time and again, it was the committed believer, armed with a personal sense of what religion should be, who asked the sternest questions. Piety was dissent. It brought a quality of indignation, an educated fury, more dynamic than the rays of humanist learning in the erosion of orthodoxy. The trail of protest took me back into the appraisive drama of the Reformation, where I found an army of mystics beating Bayle to his task. This is one reason why secularism never lost the feel of sectarianism, a struggle for purity. That is how it began. The Enlightenment was a fizzing reality before Voltaire was invented.

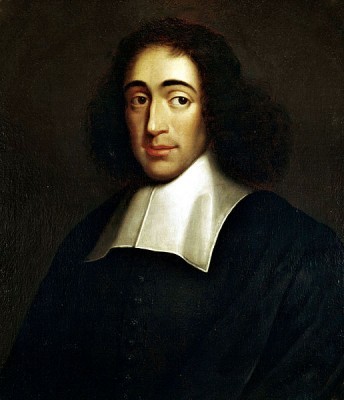

Portrait of Baruch de Spinoza (1632-1677), ca. 1665. Public domain via Wikimeda Commons.

Portrait of Baruch de Spinoza (1632-1677), ca. 1665. Public domain via Wikimeda Commons.In this civil war of the spirit, the English Quakers seemed to be everywhere. They were pioneers of a kind of spiritual rationalism that extolled the “inner light” of Christ above any external authority, including the Bible. It is no accident that Thomas Paine was raised on this deeply Protestant formula, or that Baruch Spinoza developed his biblical criticism in the flamboyant company of a roaming Quaker evangelist and scholar, Samuel Fisher. Voltaire was obsessed with the Quakers, attributing many of his ideas to the “just” and “peaceable” sect. After a year in his company, I believed him.

But the biggest surprise remained Spinoza, the “Moses of modern freethinkers,” who simply refused to play the part posterity had assigned for him. Even more than Bayle, Spinoza judged religion with the nervous energy of an insider. The “prince of atheists” was another bruised believer. Only a handful of scholars seemed to appreciate this. Of all my sources, Spinoza was the one who really got under my skin – a courageous and profound thinker as frequently misunderstood by his admirers as his detractors.

Yet as Spinoza eloquently acknowledged, you cannot force anyone to agree with you. I once gave a public lecture on Spinoza, giving full rein to his mystical affinities and explaining how his suspicions of “providence” surfaced in response to persecution. He was trying to recover jewels from a bonfire. I felt my audience stiffen as I redefined a philosophical bogeyman as a frustrated believer. “But would he pass a Trinity test?” came the first question, steering us back to common sense. I wouldn’t like to ask.

Featured image credit: “Rotterdam, Crooswijk, Begraafplaats. Kunstwerk ‘Pierre Bayle bank’ van Paul Cox. The Netherlands.” by Wikifrits. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An educated fury: faith and doubt appeared first on OUPblog.

Perfumes, olfactory art, and philosophy

What could philosophy have to do with odors and perfumes? And what could odors and perfumes have to do with art? After all, many philosophers have considered smell the lowest and most animal of the senses and have viewed perfume as a trivial luxury. Worse yet, in modern society, the nose and smells have often been the butt of jokes from Gogol’s famous short story to schoolboys snickering over farts. And when people have been asked which of the senses they could give up if forced to make a choice, smell usually comes in first.

It is no wonder then, that even the most expansive lists of the fine arts have seldom included perfumes or that, until the 1980s, there were few artists who used odors or perfumes as part of their artworks, and even fewer who focused their careers on making olfactory art. But over the last three decades things have changed. A growing number of artists have begun to use odors in their artworks and a few, such as Clara Ursitti or Peter de Cupere, devote most of their artistic efforts to olfactory art. As for perfumes, a number of perfumers and perfume enthusiasts, such as Jean-Claude Ellena or Chandler Burr, have become more assertive in claiming that perfume should be considered a fine art, whereas some contemporary artists have created or commissioned perfumes or perfume-like works as part of conceptual, performance art, or installation pieces. Finally, many art museums during the past two decades have exhibited works of olfactory art and there has been at least one notable museum exhibition explicitly treating perfumes as fine art, The Art of Scent: 1889 to 2012 at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design.

These developments raise issues that merit philosophical reflection and I will briefly state my position on several of them. To begin with, I believe the tradition stretching from Kant to Scruton that rejects odors and perfumes as a basis for serious art, claiming that they are evanescent, lack structure, or cannot express meaning, is fundamentally mistaken. Secondly, there is the problem of whether the category ‘olfactory art’ names a coherent art form or is only a term of convenience for grouping art works that involve odors to some degree. I believe the latter is the case. Thus, at one end of the spectrum, there are works like Jana Sterbak’s Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorexic that happened to emit the odor of rotting meat after a few days, but the smell was ancillary to the work’s main point, whereas at the other end of the spectrum there are works like Clara Ursitti’s Self-portrait in Scent #1 in which odor is the primary vehicle of expression. Moreover, although the term ‘olfactory art’ is typically used for works shown in museums devoted to the visual arts, odors have also been used with films, dramas, and music. A notable example of ‘olfactory art’ in this broader sense, is Green Aria, (2009), a collaborative scent opera that presented an environmental narrative through a combination of electronic music, visual images and a series of odors created by a perfumer.

Image credit: Love Stories Perfume by Vetiver Aromatics. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Love Stories Perfume by Vetiver Aromatics. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Finally, there is the question of whether perfumes as normally understood are to be classified and appreciated as works of contemporary art or whether they should be understood and appreciated as works of design. Given an aestheticist definition of art, there seems no reason to deny that perfumes are art works, but given a contextualist definition, even the finest perfumes are not fine art since, like fashion design, they are meant to be worn and typically circulate via different kinds of institutions than most works of contemporary art. Obviously, simply showing some perfumes in an art gallery or museum does not automatically make them into works of fine art, but requires some justificatory arguments. Many of the perfumers who have made a case for perfume as an art form have argued that perfumes are fine art because, like painting or music, they manifest harmony and beauty, but harmony and beauty are hardly central criteria for contemporary art.

Yet, there are some perfume enthusiasts, today, who write blogs that discuss certain niche perfumes more for their unconventional olfactory qualities than for their beauty and harmony, or their wearability. Hence, even though the typical commercial perfume remains a work of design art, there is a close proximity, if not overlap, between some of today’s niche perfumes and the perfume-like scents created or commissioned by contemporary artists.

Featured image credit: Roses by Malte Sörensen. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Perfumes, olfactory art, and philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

The concept of ‘extraterritoriality’: widely used, but misguided and useless

‘Territoriality’ plays a central role under our current paradigm of jurisdictional thinking. Indeed, a State’s rights and responsibilities are largely defined by reference to territoriality. Consequently, the activities of (for example) courts and law enforcement agencies are typically delineated by territorial reference points. Put simply, States have exclusive powers in relation to everything that occurs within their respective territories, and this right is combined with a duty to respect the exclusive powers of other States over their respective territories.

Given the above, it is only natural that much ink has been spilled over the issue of ‘extraterritoriality’; after all, if conduct and activities can be territorial in some circumstances, they can be extraterritorial in others. And while extraterritorial conduct and activities represent a natural aspect of our modern world, characterised by great mobility and extensive cross-border interactions, extraterritoriality causes tensions in the current legal framework.

Our attempts at structuring our world according to a distinction between territorial and extraterritorial has failed; to mark the difference in this way is to invite confusion, and there are two serious problems with this distinction.

First of all, too often, it is not possible to draw a distinction between territorial jurisdictional claims and extraterritorial jurisdictional claims. Consider, for example, the question of whether a State is exercising jurisdiction over activities occurring outside its territory where it regulates the use of personal information about its citizens stored in a cloud computing arrangement with multi-jurisdictional reach. As Kuner points out beyond the disagreements about its meaning as a legal concept, the term extraterritorial has acquired political baggage that makes its use charged with emotion. Indeed, Ryngaert has concluded that, because the term ‘extraterritorial’ is tainted by pejorative connotations acquired over the years, the term ought to be avoided.

Second, even if we were able to draw a sharp line between jurisdictional claims that are territorial, and those that are extraterritorial, identifying a jurisdictional claim as being extraterritorial tells us little, or nothing, of value. Some extraterritorial claims can be indisputably legitimate and useful, while other extraterritorial claims are equally indisputably illegitimate and excessive. Yet too often the false territorial/extraterritorial distinction is used as shorthand for legitimate (i.e. territorial) claims vs illegitimate (i.e. extraterritorial) claims of jurisdiction. Such oversimplifications are unhelpful and invariably create obstacles for a fruitful debate.

In light of the above, it seems reasonable to conclude that the concept of extraterritoriality, despite the central role it is playing at the moment, is associated with two serious problems; (1) it is not possible to distinguish, in a meaningful way, between what is extraterritorial and what is not, and (2) even if such a distinction could be drawn, it does in fact not tell us anything useful. Put simply, as currently used, the concept of extraterritoriality manages to be both meaningless and useless, at the same time as it causes confusion and hinders a constructive debate.

The question is then to what we should move on. I have expressed the view that we may turn our focus to whether or not a jurisdictional claim has ‘extraterritorial effect’ or not; that is, an assertion of jurisdiction ought to be regarded as extraterritorial as soon as it seeks to control or otherwise directly affect the activities of an object (person, business, etc.) outside the territory of the state making the assertion.

This proposal overcomes the first of the two problems outlined above – it makes it feasible to draw a sharp line between what is territorial and what is extraterritorial. However, I now doubt that this definition can fully overcome the second problem I sought to bring attention to above. After all, in many, if not a majority of, cases a claim of jurisdiction will have some extraterritorial effect as defined above. Thus, focusing on an extraterritorial effect will presumably not satisfy the threshold for extraterritoriality, for example, in the context of the presumption against extraterritoriality found in the laws of many countries. As pointed out by the US Government in the ongoing Microsoft case: “The principle against extraterritoriality presumes that Congress does not intend for a law to apply extraterritorially. It does not presume Congress’s intention to be that the law has no incidental effects outside the country whatsoever.”

In light of the above, our obsession with the territoriality/extraterritoriality divide must come to an end, and the main conclusion to be drawn from the above is this: if, as has been demonstrated, the conceptual distinction between territoriality and extraterritoriality does not fully work, the usefulness of the territoriality principle is severely undermined and it is no longer deserving of the supreme position it holds currently.

Featured image credit: NASA Earth’s Light, by GSFC. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The concept of ‘extraterritoriality’: widely used, but misguided and useless appeared first on OUPblog.

November 16, 2015

Historical “emojis”

Oxford Dictionaries has selected emoji as Word of the Year 2015, so we asked several experts to comment on the role that emojis play in language.

Emojis originated as a way to guide the interpretation of digital texts, to replace some of the clues we get in ordinary speech or writing that help us understand what someone is trying to communicate. In person or over the telephone, facial expression and voice modulation help us get our meaning across; in most forms of writing — blog posts, stories, even emails — we have the luxury of expressing ourselves at some length, which hopefully leads to clarity. Emojis are the perfect way to comment on own’s texts when character length and attention spans are short, when you want to make sure that your joke is taken as a joke  or that your friend knows just how funny you found her Instagram post

or that your friend knows just how funny you found her Instagram post  .

.

People have been using pictures to comment on their own and on other’s texts long before these little smiley faces, though. Let’s have a look at some ways people in the past have tried to control the interpretation of texts, sometimes by narrowing down the number of possible meanings, sometimes by multiplying them, and sometimes by just sowing general confusion.

#

In the 14th and 15th centuries, manuscripts were littered with people, often knights, fighting snails. Manuscript pages were carefully planned out; it was expensive and time-consuming to make a book by hand, so these bellicose mollusks are no mere doodles. They meant something, but what? We might expect manuscript illustrations to guide our interpretation of a text, to point us toward a particular meaning. In the Middle Ages, however, images were more often used to open up multiple interpretations, to suggest different ways of understanding a text.

Knight v Snail II: Battle in the Margins (from the Gorleston Psalter, England (Suffolk), 1310-1324, Add MS 49622, f. 193v. © The British Library Board. Used with permission.

Knight v Snail II: Battle in the Margins (from the Gorleston Psalter, England (Suffolk), 1310-1324, Add MS 49622, f. 193v. © The British Library Board. Used with permission.Here, for example, the knight/snail battle appears at the bottom of a page from the Canticle of Moses. This part of Exodus is about how the Lord is “like a man of war” and how he has triumphed over Pharaoh and cast his chariots, horses, soldiers, etc. into the sea. It makes a certain amount of sense to have a knight, then, but the snail? Perhaps Pharaoh posed as much trouble to God as a snail would to an armored warrior. Or perhaps we are supposed to glean another meaning from the knight-mollusk conflict: we on earth also have our battles, but they happen not in the glorious realm of the divine, but the absurd.

#

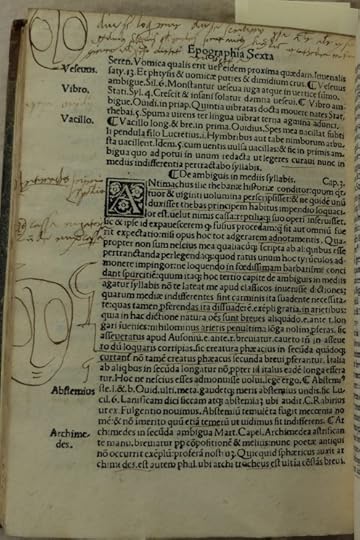

This is an example of doodling. An early reader was studying a 1519 copy of De Syllabarum Quantitate (On the Quantity of Syllables), by the French-Italian religious poet and playwright Giovanni Francesco Conti (known as Quintianus Stoa) and was moved to fill the margins with these faces and scythes. In reality, we don’t know what he or she meant to convey — there was no standard iconography of facial expressions, no helpful emoji dictionary, at the time. Yet the faces still influence our interpretations of the text. They record the reader’s own reaction to Stoa’s writing, which, given the drawings’ blank eyes and small, set mouths (and their presence in one of the book’s most gripping sections, on “ambiguity in the middle syllables”) appears to have been a fairly deep boredom.

UL classmark, Adv.c.25.1. Photo by Jason Scott-Warren. Cambridge University Library. Used with permission.

UL classmark, Adv.c.25.1. Photo by Jason Scott-Warren. Cambridge University Library. Used with permission.This is the  or

or  (= “meh”) of the 16th century.

(= “meh”) of the 16th century.

#

In the past, writers most often tried to control the interpretation of their works with extra words — whether in the main piece of writing itself or in glosses and footnotes — which we cannot afford in this era of 140 characters or less. The early modern writer perhaps most determined to control his reader’s experience was Edmund Spenser. He attached a very long gloss to his Shepheardes Calendar (1579) that explains all the things the reader might have missed or misunderstood. In the first section of the poem, for example, the hero, Colin, loves a lass, but is beloved by another shepherd, Hobbinol: “my love he seeks with daily suit” Colin complains, but “his clownish [rude, unsophisticated] gifts and curtsies I disdain.” The gloss clarifies that “In this place seemeth to be some savor of disorderly love, which the learned call pederasty: but it is gathered beside his meaning.” Spenser has just called “no homo.” (This slang — obviously derogatory — developed in the 1990s when speakers wanted to distance themselves from something that sounded “gay,” and is now fairly prevalent in social media.) The gloss goes on at such length, though, that it protests too much. Is he really denying Hobbinol’s “disorderly” love? Had emojis been available to Spenser, he might more economically have said,

.

.

#

The “laughing so hard that I’m crying” emoji is growing in popularity because the acronyms that previously indicated extreme amusement — LOL (laughing out loud) and LMAO (laughing my ass off) — are more and more used only in an ironic sense. Most emojis are rather straightforward.

= happy.

= happy. = angry.

= angry. = interested in Tinder match’s salacious proposal.

= interested in Tinder match’s salacious proposal.

is more interesting, straddling as it does the line between joy and sadness, showing that sometimes it can be hard to tell one from the other. I’d like to think that part of its popularity lies in our age-old desire to complicate things, to let meanings proliferate rather than narrow them down.

is more interesting, straddling as it does the line between joy and sadness, showing that sometimes it can be hard to tell one from the other. I’d like to think that part of its popularity lies in our age-old desire to complicate things, to let meanings proliferate rather than narrow them down.

Emoji via Twitter open source emoji.

The post Historical “emojis” appeared first on OUPblog.

Emojis and ambiguity in the digital medium

Oxford Dictionaries has selected emoji as Word of the Year 2015, so we asked several experts to comment on the role that emojis play in language.

The selection of emoji by Oxford Dictionaries as its Word of the Year recognises the huge increase in the use of these digital pictograms in electronic communication. While 2015 may have witnessed their proliferation, emoji are not new. They were originally developed in Japan in the 1990s for use by teenagers on their pagers; the word emoji derives from the Japanese e ‘picture’ + moji ‘character, letter’. Its successful integration into English has no doubt been facilitated by its resemblance to other words that begin with the e- prefix – a contraction of electronic – found in words like e-mail, e-cigarette, and e-commerce.

The success of emoji is a direct consequence of the digital medium in which they are used. Electronic communication is a form of writing that resembles a casual conversation more than formal prose, often taking place in real time with a known recipient, but lacking the extra-linguistic cues such as facial expression, tone of voice, or hand gestures that help to convey meaning in face-to-face interactions. New methods of encoding such features of communication emerged to enable senders to include non-linguistic interjections – *sigh* – and physical responses – *facepalm*. Raising one’s voice is made possible by the use of capital letters, while additional spaces add a dash of condescension: D O Y O U U N D E R S T A N D?

The emoticon (a blend of emotion and icon), or smiley, grew out of a need to transmit a broader range of attitudes. It first appeared in computer science bulletin boards in the early 1980s, where the combination of keyboard strokes :-) were used to mark jokes, while :-( indicated seriousness. Despite being dismissed by punctuation crusader Lynne Truss as a “paltry substitute for expressing oneself properly,” emoticons developed to convey a wider range of emotions, including a straight face : |, and ones expressing surprise >:o, and scepticism >:\.

Emoji have come to replace the comparative crudity of the emoticon, enabling the representation of a far greater range of expressions with less ambiguity. Where the double smiley :-)) – used to express increased hilarity – runs the risk of appearing to imply your recipient has a double chin, emoji offer a variety of grinning faces, including ones crying with laughter, or with smiling eyes. While a similar attitude may be rendered by the ubiquitous LOL (‘laughing out loud’), this has the disadvantage of being potentially misconstrued as ‘lots of love’, with embarrassing results. Acronyms describing increased levels of amusement, such as ROTFL (‘rolling on the floor laughing’), are less well-known and considerably less snappy.

The most commonly employed emoji are the smiling, frowning, and winking faces – used to show when a writer is happy, sad, or joking. The desire to flag when a message is intended to be ironic or sarcastic is not new; in 1887 Ambrose Bierce, author of The Devil’s Dictionary, proposed the introduction of the snigger point (or mark of cachinnation ‘laughing loudly’) – a horizontal round bracket resembling a smile – which would be appended to all ‘jocular’ or ‘ironical’ sentences.

But where the use of emoji has grown out of a radical move to shake off the constraints of written language, users remain restricted by the numbers and types of emoji available. The release of new emoji is subject to the approval of the Unicode Consortium, a kind of Académie Française for emoji. Such decisions are frequently contentious, given the lack of representation of certain ethnic groups, their cultures, and religions; it is only recently that it has become possible to choose from a range of skin tones.

While recent updates have enabled greater cultural diversity, the representation of foods, clothes, and places of worship remain highly westernized. However representative emoji become, it is not possible to legislate for the cultural sensitivity of their users. The pine decoration emoji, representing kadomatsu – placed at the front of Japanese homes at New Year to welcome spirits in the hope of a plentiful harvest – is regularly used in the west as an offensive gesture, since it resembles a raised middle finger.

As new emoji continue to appear and it becomes increasingly possible to send entire messages using only these symbols, we might wonder whether there will be any need for language in the future.

For emoji to become a fully-fledged language in its own right we would need a vastly greater number of characters. At present the system remains too crude to represent all but the most straightforward concepts, as is apparent from the rendering of Herman Melville’s classic novel Moby Dick in emoji. In Emoji Dick, the novel’s famous opening sentence ‘Call me Ishmael’ is rendered somewhat cryptically by a series of icons showing a telephone, a man with a moustache, a boat, a whale, and an OK sign. But what is clear from Oxford Dictionaries’ findings is that, whether you  or

or  them, emoji are here to stay.

them, emoji are here to stay.

Featured image: Hand-drawn emoji set. (c) Maartje van Caspel via iStock.

The post Emojis and ambiguity in the digital medium appeared first on OUPblog.

Scholarly reflections on ’emoji’

Smiling Face? Grimacing Face? Speak-No-Evil Monkey? With the announcement of emoji as the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year, we asked a number of scholars for their thoughts on this emerging linguistic phenomenon.

* * * * *

“Once again the medium is the message, as Marshall McLuhan declared half a century ago. As our devices become more versatile, our means of communication become more diverse and versatile too. There was a time not so long ago when computers could communicate ONLY IN CAPITAL LETTERS. Then lowercase letters became available. Then non-Roman fonts and phonetic symbols. Then emoticons, to put feeling back in plain messages ;) :). Then the hashtag, concluding tweets with topics and comments #itsroutinenow. And then, transforming emoticons into icons, the emoji. Full-color, full-sized caricatures, almost flesh and blood, making it possible not just to adorn a story but to tell it entirely in emoji. Pygmalion or Pinocchio made human. Perhaps it’s not surprising that emoji developed in Japan, where the complicated written language is iconographic as well as phonetic. Already emojis have begun to attain a life of their own, independent of any written language. For example, you can read five Bible stories entirely in emoji. They are a little simplified, but just as pidgin languages develop into full-fledged creoles when new generations adopt them as native languages, we can expect emoji to do the same. Perhaps already somewhere in the world a child is growing up learning to communicate exclusively via emoji. [shock horror face emoji]”

—Allan Metcalf, Professor of English at MacMurray College and author of From Skedaddle to Selfie: Words of the Generations

* * * * *

“The choice of the word emoji as the Oxford Word of the Year brings salty tears of joy to my eyes. The choice is inspired in several ways. It’s a fine example of the way in which a borrowing—the Japanese words e (“picture”) and moji (“letter”), meaning picture writing—seems to take on a take on a new etymology based on emo (meaning emotion), perhaps an influence by punk rock, and the use to which emojis are put. The word emoji also illustrates the way in which usage changes to be more flexible. The once ubiquitous smiley or smiley face was too specific to capture the full range of emotions expressed (frowns, joy, laughs, winks, tongues stuck out, and more) so the more general term took hold. Emojis, like other linguistic innovations (such as uptalk and topic changing “hey”), are finding their way into genres and generations where you don’t expect them. When I grade student papers, I usually write extensive comments in the margins, but sometimes I add hand-drawn emoji—a smile, a frown, a surprised look, closed eyes, a confused spiral over my head. Having the options to use emojis gives me yet another way to communicate with my students.”

—Edwin L. Battistella, Professor of Linguistics at Southern Oregon University and author of The Logic of Markedness, Bad Language, Do You Make These Mistakes in English?, and Sorry About That: The Language of Public Apology.

* * * * *

“Language is as subject to fads as is fashion. With online communication, first it was emoticons, then emoji, and now increasingly animated GIFs. Yes, graphic elements complement textual meaning. However, it’s unlikely that graphic communication will replace writing. Keep in mind that while emoji are fun to use, like LOL before them, they not as unambiguous in meaning as their surface form suggests. What’s more, we know historically that writing systems that began as pictures of things (think of Chinese characters and of hieroglyphics in the Middle East) evolved into arbitrary symbols over time. The same is true of sign language systems such as ASL.”

—Naomi S. Baron, Professor of Linguistics and Executive Director of the Center for Teaching, Research & Learning at American University in Washington, DC, and author of Words Onscreen: The Fate of Reading in a Digital World and Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World

* * * * *

“It’s very adventurous for Oxford Dictionaries to choose the ‘Face with Tears of Joy’ emoji as Word of the Year, because — while I don’t consider myself some kind of word chauvinist — I’m pretty sure it’s not a word. That’s not its fault; no emoji is a word. IMHO.

“The distinction between what counts as a word and what doesn’t is fairly straightforward. Words are symbols, of course, but they aren’t pictures. New words are usually made from used word parts. We could express “laughing with tears of joy” as a word — LWTJ, an initialism like LOL ‘laughing out loud’ and ROTFLMAO ‘rolling on the floor laughing my ass off’, just to choose two obvious laughing-focused initialisms. But these initialisms are a little suspect, too. An RSVP is something you send or, if you verb it, something you do, the act of replying to an invitation. But LOL and the hypothetical LWTJ are more like interjections and they comment emotionally on something that’s been said — ‘You forgot to put the top on your juicer and you’ve got juice and bits of beet and carrot all over you and in every corner of your kitchen? ROTFLMAO!!!!!!!!’

“Because they register this meaning beyond words and sentences — pragmatic meaning, the linguists call it —it might be nearer the mark to think of emojis as a new kind of punctuation, not in the service of syntax like commas or semicolons, but more like the exclamation point, a mark of excitement or horror or joy, just the sort of undifferentiated and rather vague mark we could usefully supplement with a more specific emoji.”

—Michael Adams, Professor of English Language and Literature at Indiana University and author of Slang: The People’s Poetry, From Elvish to Klingon: Exploring Invented Languages, Slayer Slang: A Buffy the Vampire Slayer Lexicon, and the upcoming In Praise of Profanity

* * * * *

“I’m not surprised that emoji is Word of the Year. Emojis have attracted a huge amount of interest over the past few months in English, as they offer a novel and intriguing dimension of communication for that language. The interesting question, to my mind, is how long will the novelty last. If the world of text-messaging is anything to go by, not so long. When I wrote Txtng: the Gr8 Db8, a few years ago, the fashion for including weird abbreviations in texting was at its height. Today, hardly any of the abbreviations that were so popular then can be seen in the texts of young people. I was in a school not so long ago, talking to sixth-formers who had collected a small corpus of their texts for analysis. Not a single abbreviation was to be seen. I asked them where they had gone, and was told in no uncertain terms that they weren’t cool any more. One lad confided to me that he had stopped abbreviating when his dad had started! So it goes.”

—David Crystal, author of Txtng: The Gr8 Db8, Begat: The King James Bible and the English Language, Wordsmiths and Warriors: The English-Language Tourist’s Guide to Britain, Words in Time and Place: Exploring Language Through the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford Illustrated Shakespeare Dictionary, and the upcoming Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation

* * * * *

Featured image: Seamless pattern with emoticons. (c) SuslO via iStock.

The post Scholarly reflections on ’emoji’ appeared first on OUPblog.

The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is… emoji

As 2015 draws to a close, it’s time to look back and see which words have been significant throughout the past twelve months, and to announce the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year. Without further ado, we can reveal that the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2015 is…

For the first time ever, the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is a pictograph, officially called the ‘Face with Tears of Joy’ emoji.

An emoji is a small digital image or icon used to express an idea or emotion in electronic communication. The term is a loanword from Japanese and comes from e ‘picture’ + moji ‘letter, character’. It was used in English-language Japanese publications as early as 1997 but remained rare outside of Japanese contexts until 2011, when Apple launched iOS 5 with emoji support. Emoji is not to be confused with emoticon, a facial expression composed of keyboard characters — such as ;) — rather than a stylized image.

Why was an emoji chosen?

Emojis (the plural can be either emoji or emojis) have been around since the late 1990s, but this year saw their use, and use of the word emoji, increase hugely. According to data from the Oxford Dictionaries New Monitor Corpus, usage of the word emoji more than tripled in 2015 over the previous year.

‘Face with Tears of Joy’ was the most used emoji globally in 2015, according to research carried out by SwiftKey, the makers of a smart keyboard app and emoji keyboard. SwiftKey identified that ‘Face with Tears of Joy’ made up 20% of all the emojis used in the United Kingdom in 2015, and 17% of those in the United States, a sharp rise from 4% and 9% respectively in 2014.

Emojis have been embraced as a nuanced form of expression, and one which can cross language barriers. Earlier this year Unicode 8 introduced more diverse emoji, including individuals with various skin tones as well as long-requested symbols such as the mosque, the cricket bat, and the taco. Politicians have solicited emoji answers; works of literature have been ‘translated’; emojis have become part of social campaigns.

The Word of the Year shortlist:

ad blocker, noun: a piece of software designed to prevent advertisements from appearing on a web page.

Brexit , noun: A term for the potential or hypothetical departure of the United Kingdom from the European Union, from British + exit.

Dark Web, noun: the part of the World Wide Web that is only accessible by means of special software, allowing users and website operators to remain anonymous or untraceable

fleek, noun: (chiefly in the phrase on fleek ) extremely good, attractive, or stylish

lumbersexual, noun: a young urban man who cultivates an appearance and style of dress (typified by a beard and check shirt) suggestive of a rugged outdoor lifestyle

refugee , noun: A person who has been forced to leave their country in order to escape war, persecution, or natural disaster.

sharing economy , noun: An economic system in which assets or services are shared between private individuals, either for free or for a fee, typically by means of the Internet.

they (singular), pronoun: Used to refer to a person of unspecified sex.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

The post The Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is… emoji appeared first on OUPblog.

How and why are scientific theories accepted?

November 2015 marks the 100th anniversary of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. This theory is one of many pivotal scientific discoveries that would drastically influence our understanding of the world around us. But how, and why, are these theories accepted – first by the scientific community, and then by the general public? To find out, let’s use Einstein’s relativity as a case study to examine how scientists have made 20th century science as we know it today.

Download the infographic as a PDF or JPG.

Featured image credit: “Albert Einstein during a lecture in Vienna in 1921″ by Ferdinand Schmutzer. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How and why are scientific theories accepted? appeared first on OUPblog.

“Did I do what I should have done?”: white clergy in 1960s Mississippi

In his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr. expressed keen disappointment in white church leaders, whom he had hoped “would be among our strongest allies” and “would serve as the channel through which our just grievances could reach the power structure.” Southern white clergy members in the civil rights era are stereotypically portrayed as outspoken opponents of change, or as chaplains of the segregated system who claimed a purely “spiritual” (i.e., not “political”) role for the church, or as somewhat sympathetic supporters of the black freedom struggle who remained in tormented silence, afraid to stir things up and hurt the church and their own careers. Looking back on that time, many white pastors who led churches in the 1960s have asked themselves, “Did I do what I should have done?”

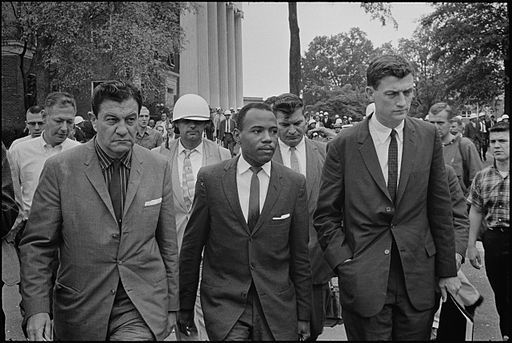

In Mississippi, the state known as “the toughest nut to crack” by movement leaders, a few white church pastors tried to do the right thing. In response to the 30 September 1962 riot at Ole Miss on the eve of James Meredith’s registration as the school’s first African American student, a small ecumenical group of white clergy in Oxford, including Episcopal priest Duncan M. Gray Jr., issued a call for repentance “for our collective and individual guilt in the formation of the atmosphere which produced the strife at the University of Mississippi.” Most white Mississippians aware of this appeal either ignored or rejected it.

“Integration at Ole Miss[issippi] Univ[ersity] / [MST]” by Marion S. Trikosko. Public domain via Library of Congress.

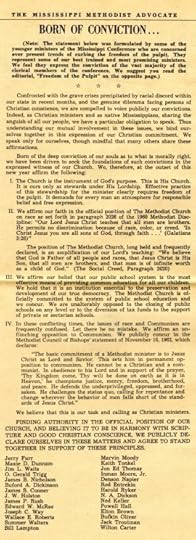

“Integration at Ole Miss[issippi] Univ[ersity] / [MST]” by Marion S. Trikosko. Public domain via Library of Congress. “Born of Conviction” statement from The Mississippi Methodist Advocate, January 2, 1963. Courtesy of the Mississippi Annual Conference, The United Methodist Church.

“Born of Conviction” statement from The Mississippi Methodist Advocate, January 2, 1963. Courtesy of the Mississippi Annual Conference, The United Methodist Church.James B. Nicholson, pastor at Byram Methodist Church near Jackson, hoped in vain that his bishop or the pastors of large Jackson churches would respond publicly to the riot, but then, he said, “I began to realize, why was I looking for the church to say something? …For the whole thing was bearing down on me. What in Sam Hill were you ordained for?” In his 21 October sermon, he told his congregation, “We have let prejudice shut out the Gospel and in many areas of our lives have turned to the gods of segregation and white supremacy to sustain us.” He insisted schools should be kept open when desegregation came and asserted the education of children “is certainly more important than the doctrine of segregation. If the time ever comes when I must choose whether my children go to school with Negroes or else have no school at all, my children will go to school with Negroes.” The congregation tried to dismiss Nicholson; the district superintendent prevented it then but assured them their pastor would not speak on race again (Nicholson made no such promise). Most church members boycotted worship in response.

Later that fall, Nicholson joined 27 other Methodist pastors of the white Mississippi Annual Conference in signing “Born of Conviction,” published in the Mississippi Methodist Advocate on 2 January 1963. In the wake of the Ole Miss riot and the continuing denial of responsibility for it by white Mississippi, these ministers went on record as opposing ongoing massive resistance efforts. The statement called for freedom of the pulpit and quoted the Methodist Discipline: “Our Lord Jesus Christ teaches that all men are brothers. He permits no discrimination because of race, color, or creed.” The signers asserted, “We are unalterably opposed to the closing of public schools on any level or to the diversion of tax funds to the support of private or sectarian schools,” and they affirmed their “unflinching opposition to Communism” in anticipation of the usual accusations of Communist influence hurled at anyone who dared challenge the status quo in Mississippi. “Born of Conviction” attempted to address “the genuine dilemma facing persons of Christian conscience” and responded to the “anguish” of those white Methodists who were deeply troubled by the excessive evil of the segregated system but felt paralyzed and unable to speak against it.

“Born of Conviction” caused a huge controversy in Mississippi. James Nicholson’s decision to sign resulted in his dismissal as pastor of the Byram Church, and two other signers were also ousted from their congregations. The other 25 participants experienced a range of responses, from threats and ostracism to private and sometimes public support; in some churches the statement fostered significant discussion of the race issue. By mid-1964, 18 of the 28 had left Mississippi, including Nicholson; two more left eventually. Some were truly forced to leave; others chose to do so for various reasons. One who could have stayed explained his 1963 departure the following year by saying, “If I could have found any encouragement from a single leader in the Mississippi Conference, not excluding the Bishop or my District Superintendent, assuring me that the cause of justice and brotherhood was the concern of the Methodist Church and that this would be a united effort wherein their support could be felt, I would be there to this day.” Yet eight signers remained in ministry in the Mississippi Conference for the rest of their careers, and two others returned to the North Mississippi Conference by 1967.

The civil rights movement resulted in significant change in Mississippi, the South, and the nation because its leaders and workers risked their lives on a daily basis in the fight for freedom and equality for African Americans. Southern white churches mostly stayed on the sidelines and were thus complicit in white resistance, but some of their clergy and lay leaders spoke or acted against the tide. Though “Born of Conviction” seems mild today, its publication represented a significant denial of Mississippi’s insistence that all its white Christians supported maintenance of segregation. The consequences suffered by many of the signers pale in comparison to the difficulties faced by civil rights workers, but these ministers paid a price for doing at least part of what they “should have done.”

The post “Did I do what I should have done?”: white clergy in 1960s Mississippi appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers