Oxford University Press's Blog, page 583

November 25, 2015

Etymology gleanings for November 2015

It is true that the etymology of homo confirms the biblical story of the creation of man, but I am not aware of any other word for “man” that is akin to the word for “earth.” Latin mas (long vowel, genitive maris; masculinus ends in two suffixes), whose traces we have in Engl. masculine and marital and whose reflex, via French, is Engl. male, referred to “male,” not to “man.” Its etymology is, as usual, unknown. Comparison with Sanskrit (pú)mans “man” seems to have been abandoned. Russian chelovek (stress on the last syllable) is a compound. Although its etymology is not quite certain, rather probably, chel– has the root of a word for “rise, grow,” while –vek is related to Latvian vaiks “child” and its Lithuanian cognate. The similar-sounding Latvian compound was borrowed from Slavic. And yes, the old English word for “animal” was deor, related to German Tier. Now deer means “stag,” and the change of meaning (from “animal” to “the most often hunted animal”) has been traced in minute detail.

Patty ~ Paddy

I certainly did not imply that the idiom that’s what Patty shot at “nothing” was coined in or limited to Minnesota. However, before a listener to my talk show informed me that this phrase had been her father’s favorite, I was not aware of its use in living speech, and so close to home. I had seen it in the literature on idioms but never heard from anyone. The discussion about the origin of Patty will never yield definitive results: perhaps indeed Patty, perhaps Paddy, or a case of so-called hypercorrection (“urbanization”), with Paddy changed to Patty. See my note on paddy wagon in the March gleanings for this year. Instruments show that in a word writer, when pronounced as rider, the vowel is not identical to the vowel of the genuine rider. This can be true, but hi-tech is not my forte (“fort”). As indicated in that post, people write title wave, deep-seeded prejudice, and futile relations for tidal, seated, and feudal. I assume that, like me, they don’t care for the evidence of instrumental phonetics and simply make no distinction between t and d between vowels. And this is all that matters for phonology.

Contrary

Contrary or contrary? The line about Mary, Mary, quite contrary leaves no doubt that the adjective in it has stress on the second syllable. Besides this, we have contrarian, contrarious, and others. The usually helpful book Laut und Leben by Horn-Lehnert contains no section on these doublets, but I assume that contrary is a relic of the (Old) French pronunciation contraire. If so, we have a trivial case of an English word striving but not always attaining initial stress: compare capitalist ~ capitalist (the latter now probably obsolete), formidable ~ formidable, recondite ~ recondite, exquisite, ~ exquisite, and the like. In our case, there is a slight semantic difference between the two forms of contrary.

Mary, Mary, quite contrary. She is contrary even in pronunciation.

Mary, Mary, quite contrary. She is contrary even in pronunciation.On calves, paths, and the German Consonant Shift

Indeed, from an etymological point of view nothing connects calf and path in any language. The reason initial pf- occurs only in borrowed German words (never mind Pfad) is not far to seek. Pf goes back to Germanic p, which, in its turn, goes back to Indo-European b. But for some reason, b, if it existed in Indo-European, occurred in a few sound symbolic and sound-imitating words and nowhere else. Therefore, Germanic had p only in loanwords, if we disregard such dubious cognates as Engl. pool and Russian boloto “swamp” (stress on the second syllable). But Latin had initial p in abundance; hence German Pfeife “pipe,” Pfund “pound,” Pfennig “penny,” and the rest, including Pfalz. All of them were taken over from Latin early enough to undergo the so-called Second Consonant Shift; p to pf is part of it.

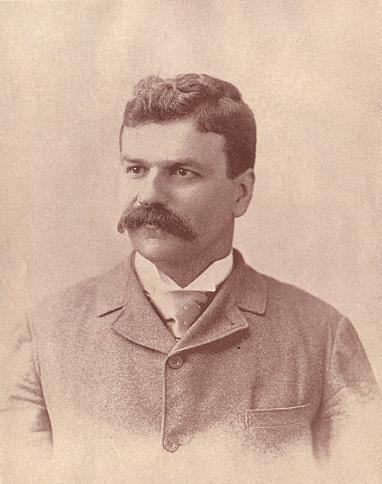

Sam Walter Foss (1858-1911), the author of the poem”Calf-Paths,” among hundreds of others.

Sam Walter Foss (1858-1911), the author of the poem”Calf-Paths,” among hundreds of others.A reality check

Last month I spent some time flogging the dead horse named actually, but actually is not the only filler that is expected to add weight to trivial statements. I also quoted an old man speaking admiringly about his grandson. Every sentence had at least (!) one occurrence of really. This is the way many people speak nowadays. Here is a typical beginning from a letter to a student newspaper:

“It’s only been a week, but I think I’m really starting to fall for this guy. He’s really got a lot of going for him; (a short catalog of his attractive features follows)…, he’s a real charmer. We’ve hung out a few times since meeting at a mutual friend’s party; it went really well. As awesome as a lot of his traits are, he’s really lacking in the hygiene department.”

The upshot is: “Wash and change your underwear regularly, for a bad smell is really off-putting, though nobody ever really likes hearing they smell bad.” Whence this epidemic? People specializing in sociolinguistics have written many pages about the use of like and you know (“he said it like ten times you know”), but I am not sure I have read anything about really. Are we so uncertain of every statement we make that instead of saying the earth is round we have to say the earth is actually (really) round?

Splitting all the way

My taunts directed at gratuitous splitting have, as they say in newspapers, backfired. Several correspondents defended the split infinitive (actually, I never attacked reasonable splitting) and reminded me that it had existed for centuries. H. W. Fowler knew it all long before we were born. But I never stop admiring the ingenuity of the splitters.

Consider the following sentence: “The University Senate’s Academic Freedom and Tenure Committee wants to then turn the idea into state legislation.” I understand: there is no good place for then here, though wants then to turn is not too bad, but isn’t to then turn ugly? I would like to now make you an offer? I was unhappy to yesterday hear the news? We’ll have to later return to this question? Similarly, I cannot stop admiring sentences like “Universities do a lot of things they used to not do.” This was said by a man occupying a very high position at the University of Minnesota where I teach. I am sure he did not speak so when he was young, but now that he is a Regent he cannot afford antiquated grammar. Why does a journalist write that Americans will have to once again commit their manpower, etc.? Why didn’t he say that Americans will once again have…? So I am asking: To be or to not be? To immediately launch attacks, to financially compensate prisoners…. Was the split infinitive invented for begetting such monsters?

I repeat after Walter Turner: “Do we now ever see unsplit infinitives?

Image credits: (1) Mature Fallow deer Stag with antlers at Safari Wilderness Preserve in Lakeland, Florida. Photo by Seth Eisenberg. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) Mistress Mary, Quite Contrary. Illustration by William Wallace Denslow from the Project Gutenberg EBook of Denslow’s Mother Goose (1902). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Sam Walter Foss, poet. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for November 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

An African tree produces white flowers: The disappearance of the black population in Argentina 110 years later

The 2014 Men’s World Cup finals pitted Germany against Argentina. Bets were made and various observations were cited about the teams. Who had the better defense? Would Germany and Argentina’s star players step up to meet the challenge? And, surprisingly, why did Argentina lack black players? Across the globe blogs and articles found it ironic that Germany fielded a more diverse team while Argentina with a history of slavery did not have a solitary black player. The Argentine team in the World Cup could have easily been mistaken for a European team. In fact the team reflected the commonly held belief that Argentine roots reside in Europe because of mass immigration that began at the end of the nineteenth century and continued through the 1940s.

“Argentina Players Pose for team photo during the 2014 World Cup final match between Germany and Argentina at The Maracana Stadium on July 13, 2014 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.” By Amin Mohammad Jamali, via Getty images.

“Argentina Players Pose for team photo during the 2014 World Cup final match between Germany and Argentina at The Maracana Stadium on July 13, 2014 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.” By Amin Mohammad Jamali, via Getty images.It is during this massive wave of immigration that journalist Juan José Soiza Reilly wrote the article that described how it affected the black population. On 25 November 1905 his article “Gente de color,” which appeared in Caras y Caretas proclaimed:

“Little by little, this race is becoming extinct…the race is losing in the mixture its primitive color. It becomes gray. It dissolves. It lightens. The African tree is producing white Caucasian flowers.”

25 November 2015 marks the 110th anniversary of this infamous saying. The roots and trunk were of African descent, representing the past, but the white buds on the tree would bring forth whiteness, representing the future. The saying reflected a lost battle because the Argentine nation slowly erased black Argentines from its identity.

This declaration, along with others (such as one made by the ex-president Carlos Menem, who noted while visiting Howard University in the 1990s that, “there are no blacks in Argentina, that is a Brazilian problem”), have continued to perpetuate the belief that there are no blacks in Argentina. But, as observations about the 2014 Argentina soccer team have revealed, it has not stopped people from questioning, what happened to the black population? In response, various myths have attempted to explain this conundrum. Some argued the wars, such as the wars of independence movement 1810-1820 and the Paraguayan War 1864-1870, killed them all, others argued yellow fever took its toll on the population, others proclaimed they migrated to Uruguay, and some simply stated “they disappeared.”

Yet, based on the first official census in 1778, at its height, African descendants accounted for up to 60% of the Argentine population. So, “what exactly happened to the black population?”

In general, scholarship has focused on the black experience in Buenos Aires and the nineteenth century. The first wave of historians who focused on the decline of the black population were social historians who provided demographic and social explanations. These historians debunked the myths of black disappearance pointing to the Argentine republic’s concerted efforts to lighten the black population in the censuses by using labels such as trigueño (wheat colored, which was applied to dark-skinned Europeans and light-skinned blacks) or pardo (an ambiguous racial category), rather than moreno (brown) or negro (black) to define their racial makeup. They also combed through military records and argued that the idea that blacks were killed off in the war was not true. In fact, more whites than blacks died in the wars of independence. They concluded the black population did not “disappear” numerically, but rather because of whitening—an ideology that stressed a white nation was a modern nation.

Leaders such as ex-president of Argentina Domingo Sarmiento (1811-1888) and Juan Bautista Alberdi (1810-1884) argued that the republic was at a crossroads in the 1840s. In order to progress, Argentina had to let go of barbarism and welcome civilization. In order to do this, they stressed the need for European immigration in order to make Argentina a modern country. Indians and other examples of barbarism had to be eliminated and the republic sanctioned the genocide of this population, known as Conquest of the Desert in the 1870s. By the end of the nineteenth century, in the midst of European immigration, Sarmiento encouraged miscegenation. He argued the mulatto (mixture between black women and white men) would incorporate the brute force of the African and the intellect of the European and slowly rid the population of “African blood.”

“Almond trees, Mallorca, Spain” by Lisbeth Hjort (via Getty images)

“Almond trees, Mallorca, Spain” by Lisbeth Hjort (via Getty images)The second wave of historians shifted to the black contributions to the Argentine republic. Many scholars utilized the black newspapers, a gem that is rarely used in analysis, to delve into the black community’s realities at the end of the nineteenth century. Moreover, the commemoration of Argentina’s bicentennial in 2010 brought to light black soldiers’ successful efforts on the battlefield, which brought about the abolition of the slave trade in 1812 and the Free Womb Act of 1813, which declared that all babies born to slave mothers are free.

Historians also shifted the focus to the interior of the country. By studying the interior cities such as Córdoba, Tucumán, Salta, Mendoza, and Catamarca, historians provide a more complex understanding of the black experience in Argentina. It must be stressed that areas such as Córdoba, which has a strong ecclesiastical presence, maintained a more traditional and hierarchical culture than Buenos Aires, which was more liberal. Such cultural differences have allowed historians to explore various black historical experiences. Today, it is no longer acceptable to rely on Buenos Aires as the only narrative of black history in Argentina.

Presently, historians have shifted the question of black disappearance to an early period, the late colonial (1776-1810), and early republican periods (1811-1853); historians such as myself are also investigating the “pre-whitening” period. Doing so highlights the social and economic conditions that brought forth the “whitening” period. In particular, black women have become a central focus. Her role as concubine, wife, and mother were crucial to the budding Argentine nation.

Nevertheless, despite the increase in scholarship to debunk the idea that Argentina was founded and shaped by European immigrants, the belief that there are no blacks in Argentina remains the narrative. Clearly, we still have a lot of work to do.

Featured image credit: “la albiceleste” by William Brawley. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post An African tree produces white flowers: The disappearance of the black population in Argentina 110 years later appeared first on OUPblog.

‘A girl who made the peacock look ugly, the squirrel unloveable': Martial mourns a lost love

I begin with one of Martial’s more troublesome twentieth-century Avid Fans: the poet, editor, translator, and Fascist propagandist, Ezra Pound:

For the gossip of Naples’ trouble drifts to North,

Fracastor (lightning was midwife) Cotta, and Ser D’Alviano,

Al poco giorno ed al gran cerchio d’ombra,

Talk the talks out with Navighero,

Burner of yearly Martials,

(The slavelet is mourned in vain)

The Fifth Canto: 110-16

‘Navighero, ǀ Burner of yearly Martials’ is Pound flaunting his alpha-nerd credentials in European literary-historical trivia: Andrea Navagero was a Venetian poet who, when fellow poets approvingly ranked his poems with Martial’s for wit, indignantly burned them (according to some sources making an annual ritual of doing so).

Navagero took offence at the comparison because of Martial’s reputation for immorality, but Pound’s bracketed aside – “The slavelet is mourned in vain” – points to a dissonant reception strand. Martial’s three epigrams on the dead slave-girl Erotion, of which 5.37 is the longest (the others are 5.34 and 10.61), have always attracted readers, and counterpoint the prevailing perception of Martial as a mercenary wit and socio-sexual opportunist. Common and scholarly readers alike find in them the key to ‘the true man’ beneath the commercially necessary mask of irreverence and filth; by sharing in his grief for Erotion we come into imaginative sympathy with ‘one of the most human and companionable of Latin authors’ (L. J. Lloyd, Greece and Rome 22 (1953)), 39-41, although he considers this particular poem a mere set-piece).

A girl more sweetly voiced than ageing swans…

This lament for his beloved pet begins like a love poem, with praise so immoderate (not to say clichéd) that some critics have thought it must be wittily ironic. I am happy for these critics if they have never experienced overwhelming loss; like falling in love, bereavement is often hard to put into words, and cliché renews itself as the primal speech of shared extremes. Think of any Valentine’s or “With Deepest Sympathy” card: what else is one supposed to say? Is bereavement a time to be clever? Then again, maybe Martial is artfully simulating; if so, he is an acute observer of the psychology of grief.

Mourning statues at the Staglieno Cemetery in Genoa. Creative Commons license via Pixabay.

Mourning statues at the Staglieno Cemetery in Genoa. Creative Commons license via Pixabay.The multisensory images piled up in the opening lines are certainly heady. Warmed in the hand, amber gives off a pine scent; at 3.65, Diadumenus’ kisses smell as sensuously exotic as “buffed amber,” and it is still used in aromatherapy. The Getty Museum supplies a useful list of ancient uses. Swans were famed for the brilliant purity of their plumage, and pallor made a woman a catch (tanned skin connoted manual labour); at 1.115 Martial is being courted by a girl “whiter than a bathed swan.” But swans also only sing just before they die (Party Favours 77) – hence our ‘swansong’ – and white connoted purity, emphasised by comparing Erotion to the virgin snow and ‘untouched lily’, both images of transient fragility as well as innocence. In an article in Classical Quarterly (42: 253-68 (1992)) Patricia Watson argued that Erotion was not just Martial’s pet but his sex-toy; but the poem’s insistence that she is ‘untouched’ seems to me to count strongly against it.

The roses of Paestum, a Greek colony, were proverbially fine; compare 12.31, “rose-beds that concede nothing to Paestum’s twice-yearly flowering.” Paestum supplied Rome’s perfume trade as well as its garland-makers. Martial’s wording alludes closely to Virgil, whose Georgics wish for space to celebrate ‘the roses of twice-flowering Paestum’ (biferique rosaria Paesti, 4.119); Ovid and Propertius glorify them too, though in terms too general to pin down the varietal, which of course could well be extinct by now. Tantalisingly, in Travels in the Two Sicilies 1777-1780 (1783-5) the travel writer Henry Swinburne attested that in his day a fragrant wild rose still bloomed among the ruins; “As a farmer assured me on the spot, it blooms both in spring and autumn.”

A girl who made the peacock look ugly, the squirrel unloveable…

When in The Praise of Folly (1509) Erasmus insists on the compatibility of flattery with genuine goodwill – ‘Is any creature more obsequious than a squirrel? But is any more friendly to man?’ – he perhaps has Martial’s poem in mind, as the modern commentators note (Erasmus, too, was an Avid Fan). According to the greatest expert on classical fauna I know, Sian Lewis, squirrels are hardly mentioned at all in surviving classical texts. To the standard wish-list of lost classical texts we’d like back – the second book of Aristotle’s Poetics (the McGuffin of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose), Cato’s Origins, the memoirs of Agrippina, and so on – perhaps we should add some hitherto-unknown volumes of ancient squirrel-lore.

And Paetus tells me I’m not allowed to grieve. He beats his breast and tears his hair…

The last seven lines of the poem are typically seen as an abrupt change of subject and tone, from decorous to humorously satirical, and for this reason critics often dismiss 5.37 as a mere rhetorical exercise and a tasteless one at that. Certainly Paetus (a fit name for a stodgy hypocrite if there ever was one) plays to type as the aristocratic abacus-rattler who only married for money; we can compare his showy and empty gestures of mourning to the Saleianus of 2.65, shedding crocodile tears as he counts his inheritance. But I can’t help but read these particular lines as furious. No-one ever knows quite what to say to the heartbroken (though the Romans tried to make a science of it) but there is nothing more calculated to incense the victim of loss than “You’ve no business being so upset, because…”

Anyone who’s lost a beloved pet – and Erotion is no more and no less than that to Martial – will know how he feels.

Featured image: Mourning Angel by Oliver Schmid. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post ‘A girl who made the peacock look ugly, the squirrel unloveable': Martial mourns a lost love appeared first on OUPblog.

Academic knowledge and economic growth

The fading role of the corporation as the exclusive institutional locus for the generation and exploitation of technological knowledge has recently brought the academic system back to center stage of analysis of the determinants of economic growth. The wide consensus on the centrality of the academic system as a crucial engine for the generation of knowledge – the basic engine of economic growth – has also called increased attention on its accountability and the assessment of its efficiency.

Policies aimed at fostering economic growth through public expenditure in tertiary education should be better aware of the different contribution of each specific academic discipline. Rather than introducing measures affecting the allocation of resources in the broad spectrum of academic knowledge, policies might instead introduce ad-hoc measures to foster specific disciplines, for example through differentiated enrollment fees for students.

Two distinct notions of efficiency apply in this context. Internal efficiency accounts for the relationship between the resources invested and the output produced at the academic system level. External efficiency accounts instead for the relationship between the resources transferred to the academic system, their output in terms of knowledge, and its effect on the output of the economic system at large, primarily in terms of increased levels of productivity.

Some kinds of scientific knowledge, and more specifically some disciplinary fields, are fundamental resources for the generation of technological change and, ultimately, also economic growth.

The literature that studies the economic features of knowledge has made it possible to understand that knowledge should not be considered as a homogenous basket of an undifferentiated good. Knowledge differs on many counts. A crucial difference concerns the capability of the different types of knowledge to support the introduction of innovations to the economic system. Some kinds of scientific knowledge, and more specifically some disciplinary fields, are fundamental resources for the generation of technological change and, ultimately, also economic growth. This is due to the fact that this type of knowledge can be applied fruitfully to very different domains; it can be easily recombined to generate further new technological knowledge and it often allows those who generate it to retain the economic value of their inventions. In this respect, this type of knowledge can be considered as intangible capital or intermediate input able to actually foster technological change. Other kinds of knowledge instead have a much narrower scope of application and do not provide substantial economic returns for those who generate it. This latter type of knowledge shares instead the characteristics of final goods able to affect the utility of final consumers.

Using data from several OECD countries on research and development expenditures in higher education, and combining it with the number of university graduate students in different disciplinary fields, we find that there are important differences in the contribution of these fields to economic growth. Hard sciences and social sciences contribute more to economic growth than, respectively, medical sciences and human sciences.

This sheds some light on the crucial issue of the intra-academic and interdisciplinary allocation of the resources devoted to the academic system as a whole. It seems more and more important to call attention on the differences among academic fields in terms of their actual capability to contribute economic growth. It seems worthwhile exploring and carefully assessing which fields deserve more funding than others, as long as public funding is advocated to support economic growth.

The undersupply of knowledge items which resemble capital goods has different consequences than the undersupply of knowledge items which resemble final goods. If the former is undersupplied, the introduction of upstream innovations that have positive effects on downstream industries is inhibited. However, if the latter is undersupplied, only the final consumers are affected.

Public policy can subsidize academic research for several reasons that might have little to do with economic growth. Moreover, economic growth is only one of the possible measures of external efficiency of the university system; an academic system might display very high levels of non-economic external efficiency that could be measured by other indicators, such as incidences of disease, life expectancy, achievements in human rights, and the relationship between leisure and work time. However if and when subsidies of the university system are advocated as a means to enhance economic growth, then public support of the academic system should focus on the academic fields that are better able to contribute to economic growth. Policy guidelines should be fine-tuned to this necessity and, on the demand-side, might introduce incentives for students to enroll in specific academic fields, through differentiated fees for example.

Headline image credit: Library-books-shelf by Sweetaholic. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Academic knowledge and economic growth appeared first on OUPblog.

The “Greater West” and sympathetic suffering

The terrible violence that has plagued the Middle East for the last fifty years and is increasingly a plague upon Europe and the United States is too often referred to as a clash of civilizations when it should instead be regarded as an internal struggle. The fundamental issues at stake – the tension between civil societal norms and religious zeal, the questions of ethnic and national identities, the conflict between advocates of social and technological change and the champions of traditional morality, and the unease produced by the real or perceived failures of modern governance and free markets – are common to all three regions.

Clearly, the degree to which they extend and the virulence with which they are debated varies enormously; yet we do ourselves a disservice when we isolate jihadist violence as a unique and uniquely foreign problem. Within the Arab world, these issues take the form of conflicts between modernizers and traditionalists (the former being advocates of democracy, women’s rights, and cultural pluralism, and the latter being the champions of sharia-based theocracy); they also include dissatisfaction with the political boundaries imposed on the region by European diplomats after the two World Wars and the governing regimes installed to maintain them. But Europe and the US also roil with conflicts over government overreach, foreign immigration, equal rights for all, manipulation of electoral processes, the treatment of women, the omnipresence of weaponry and violence in society, and the role of religious commitment in civic life. Nothing excuses horrors like the recent jihadist attacks in Paris — but it is important to remember that a single angry zealot in Norway, Anders Breivik, driven by motives analogous to those of the Parisian terrorists, killed and wounded as many people in 2011; so too with the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995, when an embittered political and religious ideologue, Timothy McVeigh, killed 168 innocent people and wounded 680 more. Terrorism is an American and European problem as well as an Arab one.

The “Greater West” (that is, the geographic and cultural territory homelands of the three great monotheisms) is now, and as ever, confronted with a host of problems. If we are to confront them intelligently, we need to recognize that they are largely shared by all of us. To think of the recent attacks as an outrage caused by a uniquely intolerant and vicious Islamic world is both delusional and dangerous. It is also self-serving. It is hypocritical of the US to attempt to impose democracy on the Islamic world when it engineered the overthrow of a democratic government in Iran (1953) and endorsed the overthrow of democratically chosen governments in Algeria (1991) and Egypt (2012). It is equally hypocritical of Muslim religious leaders to insist that they condemn jihadist violence, when not a single one ever issued a fatwa against Osama bin Laden. The often-repeated assertion that Islam is a religion of peace would convince more people if a single cleric declared a single Islamic terrorist a de facto apostate. On the other hand, paeans to Christian mercy would ring more true if US and European political leaders would not call for admitting only Christian war refugees from Syria and Iraq.

At its root, Islam is as much a Western religion as are Judaism and Christianity, having emerged from the same geographic and cultural milieu as its predecessors. For centuries we lived at a more or less comfortable distance from one another. Post-colonialism and economic globalization, and the strategic concerns that have attended them, have drawn us into an ever-tighter web of inter-relations. The rise of secularism in Europe has eroded its religious identity and is challenging that of the US, while at the same time growing ethnic and cultural pluralism has challenged to their sense of national identity. The Arab states, for their part, struggle to retain their relative religious and cultural homogeneity while nursing historical resentments against “the imperialist crusaders” whom they blame, conveniently, for whatever problems that trouble them at any given time.

The troubles of the 21st century Greater West will not be solved by a simplistic divisiveness that pits “them” against “us.” Only by recognizing that we are all experiencing the same sufferings, confusion, and doubt – although, admittedly, in different ways and to different degrees – can we begin to regard one another with the combination of respect and sympathy that defines true tolerance.

Featured image credit: White Doves at the Blue Mosque, by Peretz Partensky. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The “Greater West” and sympathetic suffering appeared first on OUPblog.

November 24, 2015

Where did all the antihadrons go?

Describing the very ‘beginning’ of the Universe is a bit of a problem. Quite simply, none of our scientific theories are up to the task.

We attempt to understand the evolution of space and time and all the mass and energy within it by applying Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. This theory works extraordinarily well. But when we’re dealing with objects that start to approach the infinitesimally small – elementary particles such as quarks and electrons – we need to reach for a completely different structure, called quantum theory. Now, the general theory of relativity can’t handle some things in ways that quantum theory can, and vice versa. But when we try to put these two venerable theories together to create some kind of unified theory that could do the work of both, we find that they really don’t get along and the whole structure falls apart.

So far, nobody has been able to figure out how to fix this.

It’s therefore no surprise that there are many mysteries surrounding the very beginning of the Universe, in a hot ‘big bang’. But we can be reasonably confident in what our scientific theories are telling us about the subsequent evolution of the Universe from about a trillionth of a second of its coming into existence. Now, I would respectfully suggest, that’s not so bad.

At this moment in its history, the Universe was witness to a parting of the ways between the weak nuclear force, which acts on atomic nuclei and is responsible for some kinds of radioactivity, and the electromagnetic force. This event left us with a collection of elementary particles and forces pretty much as we know them today. Our current theories suggest that the Universe then evolved as it expanded and cooled through a series of ‘epochs’ in which different kinds of particles dominated. First up were the quarks, which quickly combined together after about a millionth of a second to form larger particles, such as protons, neutrons, and mesons (collectively called hadrons, which is Greek for ‘thick’ or ‘heavy’).

Now, we’ve no reason to think that the quarks would not have combined to produce equal numbers of hadrons and antihadrons, particles with the same mass but opposite electrical charge – the same numbers of positively-charged protons and negatively-charged antiprotons, for example. And, as hadrons and antihadrons tend to annihilate to produce energetic gamma ray photons when they meet each other, we might anticipate that, after about a second or so, there are no hadrons left in the Universe.

Oops.

There must be something else going on. We’re witness to the simple fact that, as far as we can tell, the visible Universe – stars, galaxies, planets, rock, ocean, sky, life – consists of atomic nuclei containing protons and neutrons. So, what happened to all the antihadrons? We have no choice but to accept that, when all the hadron-antihadron annihilation reactions were done, what was left was a small residual number – about one particle per billion – of regular hadrons. This might be random chance. If there is some subtle physical mechanism which determines that hadrons could be expected to dominate, we do not yet know what this mechanism is.

Spiral Galaxy NGC 3982 by Hubble Heritage. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Spiral Galaxy NGC 3982 by Hubble Heritage. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.One possibility is that there are subtle differences in the strengths of the force between proton and proton and between antiproton and antiproton. Although one proton experiences electrostatic repulsion when pushed up close to another proton, the strong colour force binding the quarks inside each particle ‘leaks’ beyond its borders, so two protons actually experience a mutual attraction. This attractive force is essential as it serves to hold more complex nuclei – consisting of many protons and neutrons – together. If the force between antiproton and antiproton were for some reason weaker, this could explain the source of the hadron-antihadron asymmetry.

In some very recent experiments by scientists working on the STAR detector at Brookhaven National Laboratory’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider in the US, the interactions between antiprotons have been measured for the first time. In these experiments heavy gold atoms are accelerated and smashed into each other, occasionally producing a pair of antiprotons in the ensuring chaos. The antiprotons ‘scatter’ off each other and are detected, providing measures of the strength of the interaction between them and the range over which it acts.

The bottom line is that, within the accuracy of these measurements, there is no difference in strength and range in antiproton-antiproton interactions compared with proton-proton interactions. The strong force works just the same for antiprotons as it does for protons – it is not responsible for the hadron-antihadron asymmetry.

The mystery deepens.

The post Where did all the antihadrons go? appeared first on OUPblog.

Holy horsecrap, Batman! The equine BS vocabulary

When horses were a common means of transportation, horseshit was as common as potholes are today. While actual horse feces is rare nowadays, horseshit is as common as ever in our vocabulary. The list of synonyms and euphemisms—such as horsefeathers, horse hockey, horse hooey, horse pucky, and horse apples—is huge, taking up many pages in the Dictionary of American Regional English, Green’s Dictionary of Slang, and the Historical Dictionary of American Slang. I recorded a bushel of these terms in my latest research, and I noticed that there were even more horsey terms than I suspected, including horse biscuits, horse burger, horse chips, horse cock, horse collar, horse doughnuts, horse radish, and horse turd.

But the English slang stable is vast, even vaster than what’s recorded in any slang dictionary. Just in time for election season, here are some of the rarer euphemisms terms for horseshit. Most of these terms are more commonly used for literal horseshit, which I was surprised to learn is still a problem in some horse-centered communities. But in all the following cases, the writer is talking about the kind of horse dumplings that are pure poppycock.

Please consider using these terms during the next Presidential debate, whether you’re a commentator or participant. As my grandpappy told me, “Say it, don’t step in it.”

horse cookies

“So in other words we’re stuck with the same pile of horse cookies that have been moved from one side of the corral to the other; just like during the prior regimes.” (14 September 2013, Toronto Sun)

horse crapola

“A few people tweeted me today with them being able to get around the price ranges. Is this confirmed or just horse crapola?” (15 March 2015, NepentheZ on Twitter)

horse doodoo

“The obesity ‘epidemic’ is a government- and media-fueled giant pile of horse doodoo.” (18 July 2014, Eatocracy)

horse dookie

“But despite her success with the genre, Karr admits that she often mistrusts memory. ‘I have no doubt that I’ve gotten a million things wrong and that someday some cavalry of people will ride into my life and say, “This is so much horse dookie, we can’t even believe it.”‘” (15 September 2005, NPR)

horse droppings

“If Katie Hopkins Ruled the World (TLC) was a mixed bag: part game show, part tabloid talk show, part gaseous deposit of horse droppings.” (5 August 2015, The Telegraph)

horse dung

“Ah, Dallas’ owner, president and GM – known to the wider world as the 3 greedy monkeys: Hear no evil, see no evil, and speak a load of horse dung.” (7 November 2015, Pro Football Talk)

horse excrement

“Romney fed the anti-abortion bible thumpers the same line of horse excrement that trump is now feeding them and it did romney no good,so the question becomes what makes trump think following Romney’s failed campaign strategy will work now?” (10 September 2015, comments section of Washington Times)

horse feces

“Obama appears so bored and disinterested pushing this horse feces to his drooling, weak-minded adorers, can’t this fool find anything else more important to discuss? Iran? ISIS? Rioting minorities who kill each other? Anything else?” (22 April 2015, Washington Times)

horse filth

“I heard the Santa Song and could not stop laughing all the way in Trinidad, in the Caribbean. That is the worst song in the world and that blond chic can’t sing! Carly Rae is safe, the 2 songs are different. Carly’s song is hot and the other is horse filth.” (8 November 2012, Daily Mail)

horse leavings

“And there is a shift in this rivalry. For as long as I can remember, the Cards were held up as the model organization. They bring players through, they all blossom, they play the game THE RIGHT WAY (which is total horse leavings anyway) and they never get caught out with bad contracts and bad players.” (3 May 2015, Chicago Now)

horse poo

“I love and respect my parents, and not because they hit me (I hate the horrible meme that goes around saying ‘I learnt respect because I was smacked/hit as a child’ what a load of horse-poo) but because they are good people who did the best they can, and I imagine this is how they themselves were parented.” (19 October 2015, The Daily Telegraph)

horse poopy

“What a bunch of horse poopy this article is.” (15 June 2015, Star Pulse)

horse scat

“Why do I think the old Hildebeest be diggin’ on the Duggar debacle? Well, it’s principally because it’s keeping the coverage off her abysmally unattended stump speeches, her intergalactic horse-scat and the disgustingly dirty Clinton Cash.” (7 June 2015, Townhall)

horse waste

“The head of the nation’s largest labor union is ramping up his rhetoric to fight President Obama’s Pacific trade pact, calling a key part of the White House argument ‘horse waste.’” (14 May 2015, Washington Post)

horse you-know-what

“Saban getting excited talking about headlines about players living up to 5-start expectations. He said it’s ‘horse you-know-what.’” (3 September 2015, AL.com)

Featured image credit: lóláb-horse-rider by Spary. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Holy horsecrap, Batman! The equine BS vocabulary appeared first on OUPblog.

Policing concert hall patriotism: causes

Policing patriotism at the concert hall is a time-honored tradition. One of the latest targets is the Fort Worth Symphony, which has endured public criticism for performing The Star-Spangled Banner regularly before its concerts. One fed-up critic, Scott Cantrell, recently urged all American orchestras to abandon the practice because a concert should “transport” listeners to “another world” away from “narrow nationalism.”

Peddling the existence of an ideal musical world separate from the messiness of the real, political world is the rhetorical weapon of choice for patriotism police.

E.T.A. Hoffmann, a figure perhaps best known for writing the novella The Nutcracker and the Mouse King, was among the first to rail against concert hall patriotism. Music lovers know Hoffmann for his effusive 1810 review of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Hoffmann claimed that Beethoven’s symphony has the power to reveal the “wonderful realm of the infinite” to its listeners — precisely the opposite of “narrow nationalism.”

Hoffmann’s thesis is noteworthy because other reviewers did not hear the symphony’s transcendence. Commenting on an 1809 performance in Leipzig, one critic described passages in the generally delicate second movement as “ruggedly military.” It was hardly divorced from the real world, which was embroiled in a state of total war thanks to Napoleon Bonaparte’s armies. For Austrians, the triumphalism of the finale reflected real aspirations, not an astral kingdom.

The belief in the possibility of musical transcendence was a radical departure from the prevailing paradigm of musical listening at the time. Joseph Haydn’s symphonies were so successful because they combined engaging musical rhetoric with recognizable musical signs now called “topics.” The pleasures offered by these otherwise abstract elements rooted listeners in reality.

Hoffmann, however, was not so concerned with listening. His conception of Beethoven’s symphony relied heavily on visual analyses of the score that did not necessarily reflect one’s perceptions of the music in time. For Hoffmann, the work itself could stand outside our experience of its sounds.

How to address supposedly “non-transcendent” music became a distinct challenge for believers in the Hoffmann paradigm. Their standard solution was to police patriotism. National pride blocked the path toward transcendence. Hoffmann explained in his review that the sublimity of Beethoven’s music has “nothing in common” with the real world. In contrast, he called the openly patriotic symphonies of Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf “ridiculous aberrations that should be punished with complete oblivion.”

But even Beethoven himself was not above writing patriotic music for the concert hall. Caught in the fervor of the moment, he wrote an extended instrumental work celebrating Joseph Bonaparte’s defeat in 1813: Wellingtons Sieg, Op. 91. The work’s overall soundscape matches the militarism of the Fifth, but its quotation of national anthems and realistic portrayal of a battle elicited apoplectic responses from Hoffmann’s acolytes.

George William Curtis, a New England transcendentalist and self-described “Beethoven worshiper,” complained to his friend John Sullivan Dwight that Wellingtons Sieg was a “sad disappointment.” The vexed Curtis couldn’t comprehend “what Beethoven meant by writing it” or “how he could be so purely external.” His only conclusion was that it must have been a joke.

The impulse to deprecate patriotism in instrumental music persisted throughout the nineteenth century. Joachim Raff wrote his First Symphony (1861) while fueled by anticipation for German national unification. One of the movements contains a blatant quotation of a patriotic song. The symphony actually won a major contest, but the judges complained specifically about the quotation. Covering his tracks, Raff later justified it in a preface that explained how the entire piece represents German unity.

When the powerful conductor Theodore Thomas gave the American premiere of Raff’s symphony in 1863, patriotism police showed up in droves. One reviewer complained about the “priggish preface,” while another thought it absurd to believe that symphonic music could be “in any way descriptive of German unity.” Thomas never performed it again: critics had taken it into custody.

Apparently playing patriotic music before a concert should also be unacceptable. Cantrell concludes that “The Star-Spangled Banner is as out of place” at a concert as “eating hot dogs and guzzling Cokes during a performance of a Brahms symphony.” Hoffmann would have agreed. But the sharp distinction between transcendence and nationalism falls apart when examining German symphonies with no patriotic pretense — pieces of so-called “absolute music.”

German musicians long believed that injecting patriotism into a symphony, as Raff had done, was too blustery. From their point of view, the genre itself was distinctly German. Critic August Kahlert gushed in 1843 that “the domain of the symphony has, for a long time, indisputably belonged to the Germans.” Simply writing one, no matter how abstract, was a patriotic gesture for a German. (Some composers, such as Carl Reinecke, continued to be openly patriotic anyway. His music, like Raff’s, is still serving a life sentence.)

Should intellectual property be abolished?

The Economist has recently popularised the notion that patents are bad for innovation. Is this right? In my view, this assessment results from too high an expectation of what should be achieved by patents or other intellectual property.

Critics of intellectual property rights seem to think that they should be tested by whether they actually increase creativity. Similarly, in the field of competition law, commentators suppose that it is necessary to balance the innovation promoted by intellectual property against the competition safeguarded by competition law.

This approach tends to be too strict on intellectual property rights. In order to justify them and their exploitation on this basis it is necessary to show that they actually achieve an increase in innovation. By contrast for competition law to apply there is no need to show that its intervention would actually result in improvements in efficiency, only that it is necessary to maintain competition. It is assumed that, at least in the long run, competition promotes greater efficiency.

Intellectual property rights should not be seen as an alternative to competition, but rather as essential to enable competition in factors such as innovation and quality. In the absence of protection by intellectual property rights a business can often appropriate the benefit of a rival’s efforts in these areas instead of striving to better them.

In this respect intellectual property rights are similar to tangible property rights, which are necessary to enable competition in production, since otherwise it would be more profitable to steal the products made by a rival than to try to make similar products more efficiently.

Properly understood, intellectual property rights restrict competition in some factors (production and distribution) in order to enable and enhance competition in others (innovation and quality). So there is not really a need to reconcile a conflict between the protection of intellectual property and competition, but rather a need to find a balance between different forms of competition.

This balance is provided to a large extent by the rules of intellectual property law, which determine the scope of protection according to the subject-matter. However, competition law may further regulate this balance where the exploitation of intellectual property restricts competition in a way or to an extent that it is not justified for the protection of its specific subject-matter.

And whether that is the case can generally be tested by comparing competition in all aspects (including innovation and quality) resulting from the conduct in issue with the competition that would otherwise exist, taking into account the existence, ownership and justified scope of the intellectual property rights (the counterfactual). If the comparison is negative, competition law should in principle intervene.

Both intellectual property and competition law enable economic operators to profit by doing better than other economic operators and thereby encourage them to strive to do so, that is to compete. But whether more innovation, better quality, or more efficient production or distribution actually result depends on many other factors for which neither intellectual property nor competition law should be held responsible. Striving for improvement does not always succeed.

It should be considered sufficient that intellectual property and competition law provide a framework which enables economic operators to compete in innovation, quality and efficiency. We should look elsewhere, or wait a little longer, if greater innovation, quality and efficiency are not in fact achieved.

Feature image credit: I have an idea @ home, by Julian Santacruz. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Should intellectual property be abolished? appeared first on OUPblog.

November 23, 2015

Max Planck and Albert Einstein

There was much more to Max Planck than his work and research as an influential physicist. For example, Planck was an avid musician, and endured many personal hardships under the Nazi regime in his home country of Germany. Throughout much of his life, Planck maintained a strong relationship with Albert Einstein–both as a mentor and professional colleague and as a valued friend. To learn more about the life of Max Planck and his relationship with Albert Einstein, check out the following slideshow.

Max Planck and Music

Max Planck was an adept musician in addition to being a skilled scientist. As a kid, he demonstrated great talent as a singer, pianist, and organist—playing organ during church and singing in both his Lutheran church’s choir and his school’s choir as a soprano. Later in life, when he would frequently host parties with his first wife Marie, Planck was known to perform with his house guests. A favorite trio formed between Planck, his son Erwin, and Albert Einstein—who played the violin. Image credit: Max Planck 1878. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Max Planck Discovers Albert Einstein

Today, Max Planck is recognized for “discovering” Albert Einstein and his radical theories. In 1905, Einstein lacked both a Ph.D. and a university teaching position. However, Planck almost instantly supported Einstein’s relativity theory, and in part through Planck’s backing, Einstein became a key figure among the scientific community. Image credit: From left to right: Nernst, Einstein, Planck, Millikan, and von Laue in 1931. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Max Planck Lectures

Planck gave many lectures over the course of his life, though interestingly, one of his favorite topics of discussion on the relationship between science and religion. Planck enjoyed arguing that science and religion support one another in that the premise for both is that “there exists a rational world order independent from man” and “that the character of the world order can never be directly known but can only be indirectly recognized or suspected” (“Religion and Natural Science,” in Scientific Autobiography and Other Papers). The Nazi party disliked these talks because Planck failed to emphasize religion through a specifically Christian lens, and instead treated religion more openly. Planck’s broad-minded views on religion were similar to the religious convictions of Albert Einstein. Image credit: Eugen Fischer (left) and Max Planck (right) by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories’ DNA Learning Center. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikipedia.

Max Planck and Black Body Radiation

Some of Planck’s most influential work revolved around his study of black-body radiation. Planck sought to uncover fundamental truths about the universe by exploring why all objects—regardless of size, shape, or composition—when at the same temperature would emit light at the same wavelengths. Einstein came to refer to Planck’s work in this area as “previously unimagined thought, the atomist structure of energy” (J. Heilbron, Dilemmas, p. 25). Image credit: Max Planck in 1918 by AB Lagrelius & Westphal. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Max Planck and Nazi Germany

By the winter of 1943, it was dangerous for German scientists, Max Planck included, to make any references to Albert Einstein in front of Nazi personnel—who believed Einstein to be a Jewish traitor. In 1993, Einstein became one of the first scientists to voice warnings about the terrors of the forthcoming Nazi regime. Though Planck remained driven with fierce loyalty to his German homeland, he did continue to commend Einstein’s work from time to time in his lectures. Image credit: 1927 Solvay Conference on Quantum Mechanics by Benjamin Couprie, Institut International de Physique Solvay, Brussels, Belgium. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Einstein's Relativity Theory

Einstein’s presentation of relativity theory inspired a decent amount of confusion—among the scientific community and general public, alike. This discomfort in Einstein’s theories mostly stemmed from their complexity, as they describe perception of motion from different vantage points that would require movement at rather unfathomable speeds in order to be detected. With Planck’s unwavering support, however, understanding of the brilliance of Einstein’s theories slowly spread. Planck was one of the first scientist following Einstein to publish a paper on general relativity, and he encouraged the publication of all five of Einstein’s radical papers in Annalen der Physik—a journal in which Planck served on the editorial board in 1906, and later would go on to operate as a chief editor. Image credit: Max Planck in 1933. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Planck and Einstein's friendship

In many ways, Einstein and Planck were opposites. Planck’s conservative politics, stern organization, and devotion to a professorial role in academia were countered by Einstein’s liberal beliefs, light-hearted disorganization, and distaste for university culture. However, the two maintained a deeply rooted friendship stemming from their shared devotion to a search for fundamental truths. Image credit: Max Planck by Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R0116-504. CC BY-SA 3.0 de via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: “Artist’s impression of the surroundings of the supermassive black hole in NGC 3783″ by M. Kornmesser, European Southern Observatory. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Max Planck and Albert Einstein appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers