Oxford University Press's Blog, page 580

December 1, 2015

Studying pets’ cancers may yield health benefits for humans

Initially tested in pet dogs with bone cancer, a new drug that delays metastasis now helps children with the same disease in Europe.

The immune modulator, which mops up microscopic cancer cells, has not been approved in the United States, researchers say. But, the use of mifamurtide (trade name Mepact, marketed by Takeda) overseas illustrates how companion animals, especially dogs, can serve as preclinical models for faster drug development, with surprising health benefits to both dogs and people.

Unlike the mouse model, they say, dogs develop cancers that share many characteristics with human disease: long latency periods, natural causation, genetic complexity, similar tumor size, and even drug resistance. In osteosarcomas, these parallels appear quite striking.

“Osteosarcoma is really the poster child of comparative oncology,” said Timothy Fan, D.V.M., Ph.D., associate professor in the department of veterinary clinical medicine at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. “It’s a disease that is genetically indistinguishable [in dogs] from that seen in humans.”

Scientists long have recognized that cancers arising spontaneously in dogs, and more rarely in cats, can be useful for studying human cancers. But a resurgence in interest has come mostly within the past decade, with the resolution of the canine genome in 2005 by an international team of researchers, led by the Broad Institute at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Mass. and Harvard University, also in Cambridge. This past June, the Institute of Medicine’s National Cancer Policy Board held its first workshop in Washington, D.C., on the topic: “The Role of Clinical Studies for Pets with Naturally Occurring Tumors in Translational Cancer Research.”

“Each dog breed represents a closed population genetically,” offering tremendous advantages for studying complex genes and their role in cancer and other diseases, said Elaine A. Ostrander, Ph.D., chief of the Cancer Genetics and Comparative Genomics Branch at the National Human Genome Research Institute. A leading authority in the field, Ostrander cowrote an analysis of the canine genome’s resolution.

Even though the American Kennel Club recognizes at least 185 distinct dog breeds, she said “it’s important to remember they’re all members of the same species.” If scientists are studying a particular illness in a particular breed, Ostrander said, it’s very likely they share common ancestry and carry similar genetic mutations not seen in a different breed.

Her lab has collected 50,000 DNA samples from dogs so far. Most samples come from American Kennel Club–approved breeds, Ostrander said, although researchers accept blood or saliva swabs from an occasional feral dog elsewhere in the world or from pets of volunteers who contact the institute. “Our focus is on cancer markers and susceptibility genes and how these spill over to help human diagnoses and treatment of disease,” she said.

A recent example involves a tumor marker identified in dogs who develop bladder cancer. Ostrander and her colleagues discovered a BRAF mutation in the urine of pet dogs that not only triggers their disease but also has been implicated in multiple human cancers. The marker carries an 85% predictability rate, Ostrander said, setting the stage for early diagnostic testing as well as a system for evaluating BRAF-targeted therapies in both dogs and people.

As one of the workshop organizers, Ostrander attributes renewed attention to the canine genome, in part, to the 10-year lag since the genome’s sequencing. Also, “we’re at the beginning of what we hope will be a huge slew of papers coming out soon,” she said. “We’re finding the same [genetic] vocabulary exists between humans and dogs.”

The University of Illinois’s Fan cited several other reasons for the recent focus on companion animals in cancer research. Not only have the technologic capabilities of veterinarians grown, he said, but also societal factors come into play. “People increasingly view dogs as part of their families with high emotional value,” he said, “so they’re willing to do whatever they can for them.”

Cancer occurs often in companion pets, with age the main risk factor, just as in people. Estimates suggest that half of dogs older than 10 years die from cancer, whereas roughly one-third of cats do.

Although cats are part of the spontaneous-cancer equation, Fan said, “huge gaps in the feline genome” remain. Researchers therefore view companion dogs as a better bridge between traditional rodent models and human trials for testing new drugs, devices, and imaging techniques.

Research Infrastructure

The National Cancer Institute–managed Comparative Oncology Trials Consortium supplies the infrastructure for coordinating animal clinical trials nationwide. Through this mechanism, a consortium of 20 academic centers, veterinarians participate in clinical trials to treat dogs with cancers.

Because data from research studies can be generated quickly, given dogs’ comparatively short life spans, “endpoints in drug development may be achieved in about one-fifth the time of human trials,” said Rodney Page, D.V.M., director of the Flint Animal Cancer Center at Colorado State University, in Fort Collins. The university is part of the consortium.

Also, because genetic similarities exist for other cancers, besides osteosarcomas, outcomes may be more predictive of what to expect in people, at far less cost, he and others said.

Only about 11% of drugs showing anticancer activity in the mouse go on to gain approval for human use, according to pharmaceutical data. Moreover, cancer drugs carry significantly higher attrition rates than those in other therapeutic arenas—a 5% success rate, for example, compared with a 20% success rate in cardiovascular drug development (Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:711–6).

“In the classic xenograph trial (using the murine model), we give them drugs and it’s kind of cheating,” said Amy LeBlanc, D.V.M., director of the comparative oncology program at NCI. “It’s a homogenous model. And when we apply drugs in this context, it lacks the stroma or genetic complexity of cancer in humans.”

Another limitation involves size. Because mice are diminutive, researchers cannot track disease longitudinally over time. “We can’t ask questions about basic toxicity,” LeBlanc said. In comparison, dogs are so solicitous during testing, “we know how they’re feeling most of the time,” she said. “Or, their owners tell us, ‘my dog isn’t feeling well.’”

Researchers also can test drugs in dogs that have had no previous treatments. “We routinely run novel investigative drug studies this way,” LeBlanc said. “This doesn’t happen in humans,” given ethical constraints.

Nevertheless, dogs enjoy rigorous protections as research subjects, with consent forms and oversight similar to that seen in people, according to LeBlanc. “And, the nice thing is these animals still live at home.”

Hurdles

A report from the Institute of Medicine workshop, presently under external review, will outline the advantages of integrating animal studies into clinical pathways for humans. The final document also will lay out gaps in knowledge, including the need for further molecular characterization of canine tumors.

“We still need to do the genetics in much more detail in the dog model,” said Michael Kastan, M.D., Ph.D., director of Duke’s Cancer Center, in Durham, N.C., and chairman of the workshop organizing committee. “We’re much further along in understanding human genetics than that of the dog.”

However, over the past decade, he said, targeted therapies, based on genetics, have changed how researchers use companion animals.

“This is a wonderful gift for the pet community,” Kastan said, as pet owners have the option of treating cherished pets with targeted, nontoxic therapies that may extend their lives by months, sometimes years. At the same time, by enrolling a pet in clinical research, new treatments may arise for people.

“I think we’re in our infancy with this,” he said. “But the data we obtain in dogs can inform human trials and help the animals, too. It’s mutually beneficial.”

Tapping into that benefit, workshop participants agreed, will require educational awareness about the opportunities comparative oncology affords and additional funding. Financial support for a cancer atlas in dogs, similar to the human atlas, would help propel the canine genome along toward solving the heterogeneity problem in human tumors, Ostrander said.

Also, funds to develop additional reagents would yield better understanding of immune function, Page said. At least 150 reagents exist in humans and mice to see whether a drug is working, he said, whereas veterinarians draw upon just 30–40 in dogs—and even fewer in cats.

Golden Retrievers

Meanwhile, as cancer treatments in people and animals move slowly toward personalized care, the largest observational trial ever in companion dogs recently got under way. The 10-year Golden Retriever Lifetime Study should yield genetic clues about why this breed experiences such a high rate of cancer, as well as more general information about environmental and nutritional risks.

Investigators know dogs and humans share roughly the same number of genes, but dogs rarely get colon cancers, nor do they often develop lung cancer. “Even though dog tumors have a lot of similarities to our own, dogs don’t smoke,” for example, Kastan said. “They live in our environment but lack our bad habits.”

Altogether, 3,000 dogs have been enrolled in the study, funded by the Morris Animal Foundation, a global nonprofit headquartered in Denver. Fully half of the retrievers are expected to develop cancer.

Page, the principal investigator, compares the research effort to the Framingham Study, which has monitored residents of Framingham, Mass., for cardiovascular disease risks since 1948. “It should be transformative for animal health and cross over to human health as well,” he said.

Sadly, for Leonard Lichtenfeld, M.D., deputy chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society, and the workshop’s final speaker, whatever information emerges comes too late for Lily, his beloved 11-year-old Golden Retriever. Lily died of lymphoma shortly before the workshop began.

Writing in his cancer blog afterward, Lichtenfeld admitted he gave little consideration to comparative oncology before the meeting. Nor did he realize, he said, how personal a journey such knowledge would be.

Still, the promise comparative oncology research holds—for dogs, their owners, and science—intrigues him. Quoting a colleague’s succinct observation, he wrote, “Some of the answers to the treatment of cancers in humans may, in fact, be walking right beside us every day.”

Featured image credit: Photo by paulicek0. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Studying pets’ cancers may yield health benefits for humans appeared first on OUPblog.

Meet the cast of Illuminating Shakespeare

Get to know the team behind the Illuminating Shakespeare project as they reveal their stand-out Shakespearean memories, performances, and quotations.

* * * * *

What was your first encounter with Shakespeare?

“In fifth grade we were taken to a performance of Romeo and Juliet. As hormonal adolescents we were scandalized by ribald actions of some of the extras (they were kissing in a semi-prone position on the apron of the stage) at the party where Romeo meets Juliet for the first time.”

— Christian Purdy

“My first encounter with Shakespeare was seeing an open-air production of As You Like It when I was about eight; I understood nothing at all about it.”

— Simon Thomas

“A Midsummer Night’s Dream studied at school I think around the age of 13, though that was swiftly followed by repeated studying of As You Like It almost every year from age 15 to 21.”

— Katie Hellier

“My uncle had a beautiful old complete edition of Shakespeare’s plays in two volumes on his shelf that I used to take down and look through whenever I went to stay at his house. I didn’t understand what I was reading, but it made me curious as to who this Shakespeare was. Later, when I came to study him at school, the first play we read was The Merchant of Venice. I loved it and never looked back.”

— Kirsty Doole

“I was first introduced to Shakespeare when I was studying for my GCSEs and had the chance to explore his romantic comedy Twelfth Night. With complex love triangles, gender swapping, and a shipwreck, it certainly made interesting reading and the modern twist in the film adaptation She’s the Man back in 2006 wasn’t that bad either.”

— Emma Turner

Hannah Paget is Marketing Executive for Trade Books and Project Co-ordinator for Illuminating Shakespeare.

Hannah Paget is Marketing Executive for Trade Books and Project Co-ordinator for Illuminating Shakespeare.“My first encounter with Shakespeare was in my Year 8 English class. We studied Twelfth Night and it was the first time I realised how funny Shakespeare could be, even if some of the jokes went a little over my head at the time. We also got to watch the film adaptation starring, amongst a stellar cast, Ben Kingsley as Feste. He’s been my favourite Shakespeare character ever since.”

— Alex Beaumont

“In medieval gardens in Stamford, singing an arrangement of ‘Full Fathom Five’ at the start of an outdoor Tempest. Magical.”

— Phil Henderson

“I read my share in high school, and later in college. But those encounters were primed by 90s Shakespeare: Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet and Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet. I’m sure I didn’t understand half of what I was hearing, but loved them nonetheless, and that made future readings more appealing.”

— Regan Colestock

“I can remember my mum telling me the story of Macbeth (she’s an English teacher) when I was quite small. The first Shakespeare I think I ever saw was Julius Caesar at Stratford, but I fell asleep.”

— Emma Smith

“I first read Romeo and Juliet in a ninth-grade high school English class. I didn’t appreciate Shakespeare’s work as much as I do now; I’ve since re-read the play several times and it’s now one of my favorites.”

— Abbey Lovell

* * *

Which character(s) have you acted?

“In college I was cast as Adam in As You Like It. I was nineteen playing a 70+ year old devoted manservant. Later I was cast in An Actor’s Nightmare and got to deliver a few lines from Hamlet where Horatio tells Hamlet how he saw his father’s ghost.”

— Christian Purdy

“At school, I played Puck (A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and Holofernes (Love’s Labours Lost). Being short and not particularly glamorous, at an all-girls school, I was always cast as an elderly man or a sprite. You can call them character roles, or you can just face up to the grim truth about yourself.”

— Sophie Goldsworthy

“I’ve never acted any of the big characters but I have done several turns as the ‘misc’ character actor – the guy who plays all of the other characters in the play. My favourite was in my GCSE version of Macbeth, I got to play a malevolent spirit who threw stuff at Macbeth. I managed to hit him right on the back of the head with a heavy juggling ball (don’t ask) and we still got an A*.”

— Alex Beaumont

Sophie Goldsworthy is the Editorial Director for Academic and Trade, and has been publishing Shakespearean texts and scholarship for the Press for the best part of 20 years.

Sophie Goldsworthy is the Editorial Director for Academic and Trade, and has been publishing Shakespearean texts and scholarship for the Press for the best part of 20 years.“I’ve never acted in a Shakespeare play, however I was regularly given the part of Macbeth in our A Level Literature read-throughs – partly because I was incessantly enthusiastic, partly because I was one of the few willing to commit to a Scottish accent.”

— Helena Palmer

“My first and only Shakespeare role was a theatre class production of Hamlet, where I played the title character. I was on exchange in Toronto for a year, and as the only person in my class with an English accent I was somehow considered a good fit for the Shakespearean language. They very quickly regretted that choice when they realised my acting ability. It was great fun though.”

— Hannah Paget

“I acted as Juliet’s nurse in high school, which was an exciting role to play. I’m no actress, but performing with my classmates was fun, and the assignment brought Shakespeare’s characters and their story to life.”

— Abbey Lovell

* * *

What’s the best Shakespeare production you’ve seen?

“The best Shakespeare production I’ve seen is probably the RSC’s 2007 Much Ado About Nothing, with Tamsin Greig. It was set during the Cuban Missile Crisis, for some reason, but what made it brilliant was Greig’s hilarious performance.”

— Simon Thomas

“I’ve been to so many Shakespeare productions I’ve lost count, but I think the best one that I ever saw was a production of The Winter’s Tale at the RSC in Stratford-upon-Avon. The stage was set-up as a library in a grand old house, where all the action unfolded. However, as that infamous stage direction came to fruition (“Exit, pursued by a bear”) the shelves of books unbelievably transformed into the form of a bear, dragging Antigonus away. I’ve never forgotten it!”

— Hannah Charters

“I don’t know about best, but certainly the most memorable was an open air production of Love’s Labour’s Lost I saw back home in Glasgow in about 2003. Every summer a local theatre company put on a season of ‘Bard in the Botanics’ in the Botanical Gardens where the audience would collect a small plastic stool and cart it around the Gardens as each scene took place in a different location. This particular production was set at the end of the Second World War, so was all in 1940s dress. It was a glorious June evening and as we walked around, we’d occasionally catch sight of a simultaneous production of Titus Andronicus in the distance…”

— Kirsty Doole

“I was lucky enough to see Judi Dench and Anthony Hopkins play Anthony and Cleopatra at the National Theatre in the late 1980s. I can still hear Dame Judi uttering: ‘Give me to drink mandragora. … That I might sleep out this great gap of time / My Anthony is away.’ It gives me chills.”

— Sophie Goldsworthy

“I saw the RSC production of Hamlet that David Tennant was in. Tennant was injured so we saw his understudy who was amazing. The scenes with the mirrors were unforgettable.”

— Katie Hellier

Emma Turner is Senior Marketing Executive for Literature in the UK.

Emma Turner is Senior Marketing Executive for Literature in the UK.“All’s Well That Ends Well in Central Park in 2011. The Delacorte Theater is reason enough to go, tucked into the woods behind a little castle; it feels a bit like summer camp. But the staging was also clever and effective, and a comedy/romance is great summer viewing.”

— Regan Colestock

“I was bowled over by Josie Rourke’s Coriolanus at the Donmar with Tom Hiddleston.”

— Emma Smith

“I’ve seen many productions of Hamlet in my time, but one of the best has to be the Young Vic’s 2011 production with Michael Sheen in the title role. It was set in the gymnasium of a psychiatric unit in the eighties, which was as arresting as it sounds. I’ll never forget the climax of the play scene, where Hamlet lifted a blaring stereo above his head in what seemed to be a twisted nod to Say Anything.”

— Helena Palmer

“The best Shakespeare production that I’ve seen was a performance of Macbeth during Shakespeare in the Park a few summers ago.”

— Catherine Foley

“Friends of mine acted in a performance of Macbeth in college. I knew the effort and time that they’d given in practice, and I enjoyed seeing their hard work pay off on stage. ”

— Abbey Lovell

* * *

What’s your favourite quote?

“My favourite quote comes from Julius Caesar:

‘Men at some time are masters of their fates:

The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,

But in ourselves, that we are underlings.'”

— Christian Purdy

“Much Ado is also my favourite play by Shakespeare, but I have (rather macabrely) told my loved ones that I want this, from Twelfth Night, printed on the front of the order of service at my funeral:

‘Clown: Good madonna, why mournest thou?

OLIVIA: Good fool, for my brother’s death.

Clown: I think his soul is in hell, madonna.

OLIVIA: I know his soul is in heaven, fool.

Clown: The more fool, madonna, to mourn for your brother’s

soul being in heaven.'”

— Simon Thomas

“‘The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool’ – Touchstone in As You Like It, Act 5, scene 1, line 31″

— Hannah Charters

“Going back to Twelfth Night it has to be ‘Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon ’em.’ It’s such a clever quote in the context of the play and it sounds like it could easily have been written by someone in the last few years.”

— Alex Beaumont

“I’m afraid I have a bleak weakness for Albany’s ‘Humanity must perforce feed upon itself / Like monsters of the deep’ from King Lear.”

— Emma Smith

“The most meaningful quote for me is from Hamlet: ‘I could be bounded in a nutshell, and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams’.”

— Helena Palmer

Emma Smith is Professor of Shakespeare Studies at Hertford College, Oxford and adviser for Illuminating Shakespeare.

Emma Smith is Professor of Shakespeare Studies at Hertford College, Oxford and adviser for Illuminating Shakespeare.What’s your favourite play or sonnet?

“My favorite of Shakespeare’s sonnets is no. 104, which begins, ‘To me, fair friend, you can never be old…’ Shakespeare writes that, though time continues to pass, his beloved’s beauty never fades in his eyes.”

— Abbey Lovell

“My favorite plays are the comedy capers, like Much Ado About Nothing and All’s Well That Ends Well. I also have a funny appreciation for King Lear, being a middle daughter named Regan.”

— Regan Colestock

“The Tempest, hands down. It was unlike any other Shakespeare I’d read so far, and I just really, really enjoyed it.”

— Kirsty Doole

“I love Macbeth. It’s so atmospheric and genuinely terrifying at points.”

— Katie Hellier

“Romeo and Juliet. Without a doubt, as tragic as it is, I think most people can’t help but get sucked into the world of two star-crossed lovers who ultimately meet their demise. It’s the original love story.”

— Emma Turner

“My favorite play is The Merchant of Venice, and my favorite sonnet is Sonnet 130, which is one of many devoted to the ‘Dark Lady’.”

— Catherine Foley

“Twelfth Night. Non-stop wit.”

— Phil Henderson

“Much Ado About Nothing is my all-time favourite Shakespeare play. It gets a bit sinister in the middle but I love the back and forth between Beatrice and Benedick. There is a brilliant BBC ShakespeaRe-told version (2005) with Sarah Parish and Damian Lewis set in a newsroom that I have watched many times!”

— Hannah Paget

* * *

Which Shakespearean character would you like to be for the day and why?

“Without a doubt, Falstaff. Who wouldn’t want to spend the day debauching at the Boar’s Head Inn with outlaws and brigands.”

-– Christian Purdy

“Sorry to keep harping on a theme (I have read others, honest!) but I’d love to be Beatrice for a day. She’s so brilliantly sassy.”

-– Simon Thomas

“I’d like to be Robin Goodfellow, often referred to as Puck, from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, because I’d like to be able to move so fast that I can ‘put a girdle round about the earth in forty minutes’!”

-– Hannah Charters

“Controversial as it may be, I would have to choose Lady Macbeth. Who wouldn’t secretly want to be a Shakespearean villain for the day? Ambitious, brutal, and manipulative, she takes no prisoners. Arguably one of the most powerful female figures in literature, she is a lady who knows what she wants.”

— Emma Turner

“Falstaff, obviously. For the lifestyle.”

-– Sophie Goldsworthy

Helena Palmer is Marketing Assistant for Literature in the UK.

Helena Palmer is Marketing Assistant for Literature in the UK.“Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, who wouldn’t want to be queen of the fairies for the day, or is that my inner six-year-old girl talking?”

— Katie Hellier

“One of Macbeth’s three witches. Or the ghost of Hamlet’s father. Earthly and supernatural powers.”

–- Regan Colestock

“A comic woman – maybe Viola or Beatrice. They get what they want.”

— Emma Smith

“I would love to live like Prince Hal for a day, to get the best of both worlds: part time heir to the throne of England, part time party animal!”

— Helena Palmer

“If I could be any Shakespearean character for a day, I would be King Henry VIII of England. Even though he was a real historical figure, and not a character created by Shakespeare, it would still be interesting to see inside the mind of such an infamous and volatile person.”

— Catherine Foley

* * *

Which Shakespearean characters would you match-make or have round a dinner table and why?

“I’d love to introduce Cleopatra (from, of course, Antony and Cleopatra) and Petruchio (from The Taming of the Shrew) because I think she’d make mincemeat of him. But I’d want to stay well away from them. At my own dinner table, maybe all the twins from Comedy of Errors, so I can sort out their confusion with a simple two-second conversation.”

— Simon Thomas

“Dinner with Beatrice and Benedick. With a phone to record what they said.”

— Phil Henderson

“Obviously not Falstaff. For the lawsuits. I’d get Cleopatra round to sort the catering, and invite Hamlet’s father and Banquo’s ghost. Imagine the leftovers.”

— Sophie Goldsworthy

“Feste (Twelfth Night), Falstaff (The Merry Wives of Windsor), and Mercutio (Romeo and Juliet). I think all three of them know how to have a good time and would probably end up under said dinner table.”

— Alex Beaumont

* * * * *

Featured image credit: Shakespeare’s Birthplace – Stratford upon Avon by Elliott Brown, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Meet the cast of Illuminating Shakespeare appeared first on OUPblog.

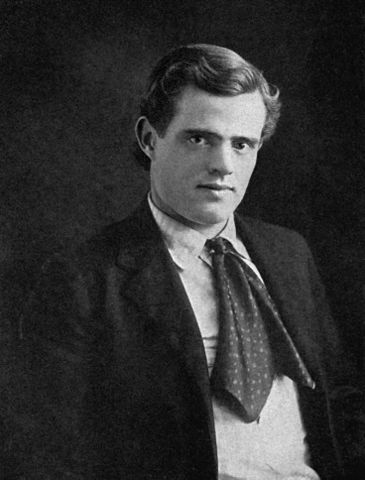

Wartime bedfellows: Jack London and Mills & Boon

What do America’s most famous novelist and the world’s largest purveyor of paperback romances have in common? More than you would think.

Jack London (1876-1916), author of The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and other classics, was published in the UK and overseas by Mills & Boon, beginning in 1912. At that time, Mills & Boon, founded four years earlier, was a general publishing house with a varied list of novels and non-fiction. Jack London was the star author on a fiction slate that included P.G. Wodehouse, E.F. Benson, and Hugh Walpole. When in the early 1930s Mills & Boon switched to a single-genre house specializing in light romances, London and other ‘high-brow’ authors were dropped.

But for four formative years, until his unexpected death at age 40, London was Mills & Boon’s top seller (George Bernard Shaw famously said, “If you wish to compliment me, call me the Jack London of the British Isles”). His notoriously combative personality was wrangled by Mills & Boon’s co-founder, Charles Boon. Boon had cut his teeth at Methuen, where he managed another literary ‘giant,’ Marie Corelli. It was a match made in literary heaven, until the disruption caused by the First World War.

The war could not have come at a worse time for London, who was enjoying unprecedented success in 1914 with his latest novel, The Valley of the Moon, and John Barleycorn, his semi-autobiographical treatise on alcoholism. The war, Boon wrote to London, “has simply put the stopper on from the point of view of selling books of any description. We shall do our best to keep your sales going.”

From his ranch in California, London was as concerned about his book sales as he was the fate of the Allies – a view contrary to the pacifism that initially kept America out of the war. “Of course, I am absolutely pro-ally,” London reassured Boon. “I would rather be a dead man under German supremacy than a live man under German supremacy. If the unthinkable should happen, and England be shoved into the last ditch, I shall, as a matter of course, go into that same last ditch and fight and die with England.” Such Alpha-male bravado would one day become the hallmark of the archetypal Mills & Boon hero.

Image credit: Photo of Jack London, 1903 by LC Page and Company Boston 1903. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Photo of Jack London, 1903 by LC Page and Company Boston 1903. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.London’s novels, pulsing with individual heroism, were popular with soldiers at the Front – until a bogus anti-war pamphlet threatened to derail his popularity. ‘The Good Soldier’ issued by the ‘Stop the War League’ of North London carried London’s byline – and called on young men to quit the army. Charles Boon, understandably, panicked. “A really strong article in our favour would help us no end,” Boon wrote. “Last week nine German spies were captured in London in English officers’ uniforms, and of all places in the world on the tops of buses. This is just to show you what a race we are fighting.”

What proceeded was a media blitz, with both London and his literary agent, Hughes Massie, granting interviews to reassure the public. Neither minced words. In the Daily Express, Massie reported that “Mr. London states that he is ‘with the Allies life and death, by English race and philosophic conviction of the righteousness of their cause.’ He declares there must be only one end of the war – namely, the subjugation of the mad dog Germany.”

The headline in the Daily Graphic, ‘JACK LONDON’S VIEW OF GERMANY, AN INSANE NATION,’ presented London as a Wild West hero, riding to the rescue. From his ranch, London proposed, “Suppose I am lying here asleep and I hear a cry for help. I rush out and find a bloodthirsty brute of a paranoiac maniac engaged in the pleasant task of shooting everyone he can see on the ranch. What can I do? Reason with him? Speak to him kindly? No, I get my own gun, the best one I’ve got; and I creep up as close to him as I can, and I pump his body full of lead. It’s the only treatment possible: the only treatment whereby the place may be freed of this paranoiac and his crazy egotism.” To London, there were 70 million like-minded paranoiacs in Germany all trying to shoot up the Allied ‘ranch.’

The PR campaign worked. London’s books sold in the thousands for the remainder of the war, with fan mail arriving from soldiers at the Front.

It is ironic that, after the war, Germany became London’s biggest European market, even larger than the UK. In 1928, London’s widow, Charmian, boasted to Charles Boon that “My main income now emanates from Germany! That is ONE good result of the War, incontrovertible – that Young Germany needs Jack London and is devouring him. Rather late, but not too late.” A Jack London sales brochure from Germany in 1929 listed all of his titles in translation and touted sales of one million.

When Hitler came to power, however, London’s books were banned, including The Iron Heel, the dystopian novel which foretold the rise of Fascism some two decades before it happened (to the marvel of critics like George Orwell). Seeds were being sown for another world war – and presumably Jack London would have ridden, once again, to the defense of the Allies.

Headline image credit: Snow-bow by James Brooks. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Wartime bedfellows: Jack London and Mills & Boon appeared first on OUPblog.

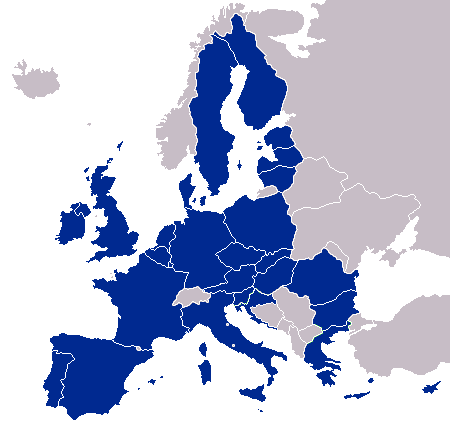

The EU and public procurement law

Public procurement is a most powerful exercise. It carries the aptitude of acquisition; it epitomises economic freedom; it depicts the nexus of trade relations amongst economic operators; it represents the necessary process to deliver public services; it demonstrates strategic policy choices.

The European Union regards public procurement regulation as an essential component of the internal market. Public procurement is identified as a considerable non-tariff barrier and a hindering factor for the functioning of a genuinely competitive internal market. Economic justifications for its regulation are based on the premise that the introduction of competitiveness would bring about price convergence and significant savings to the public sector.

The regulation of public procurement also has significant legal inferences, directly relevant to the adherence of fundamental principles of the EU such as the free movement of goods, the right of establishment, the freedom to provide services, the principle of proportionality, the principle of transparency, the principle of non-discrimination on grounds of nationality, the principle of equal treatment and the principle of mutual recognition.

The purpose for the regulation of public procurement is to insert a regime of competitiveness in the relevant markets and eliminate all non-tariff barriers to intra-community trade that emanate from preferential purchasing practices which favour national undertakings. Apart from reasons relating to accountability for public expenditure, avoidance of corruption and political manipulation, the regulation of public procurement represents best practice in the delivery of public services by the state and its organs.

Public procurement law as a discipline expands from the simple topic of the internal market, to a multi-faceted tool of European regulation and governance, covering policy choices and revealing an interface between centralised and national governance systems. This is where the legal effects of public procurement regulation are felt most. The regulation of public procurement in the European Union has multiple dimensions, as a discipline of European law and policy, directly relevant to the fundamental principles of the common market and as a policy instrument in the hands of member states. The regulation of public procurement reflects on two opposite dynamics: one of a community-wide orientation and one of national priorities.

In addition, the regulation of public procurement is a public policy matter for the European Union. A combination of legal, macro and micro-economic objectives correspond to public sector management principles such as transparency, accountability, fiscal prudency and competition and make public procurement regulation a necessary ingredient for the EU integration process. The commonly accepted assumption is that public procurement is not subject to the same commercial pressure or organisational incentives for sound management as private sector procurement which is underpinned by the foundations of strong competition. This has prompted the imposition, not only by the EU but by many jurisdictions around the world, of legal and regulatory disciplines to encourage the better use of public financial resources, to introduce greater efficiency, and to reduce the risk of favouritism or corruption in public purchasing.

EU member states 2014 by Keshetsven. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

EU member states 2014 by Keshetsven. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The stakes cannot be higher for the EU. Currently, the total public expenditure directed by the Member States in procuring goods, works and services accounts for over €1 trillion. Public procurement in the Member States is a highly fragmented and complex process. There is a large and heterogeneous range of over 250,000 contracting authorities across the EU, to which the EU public procurement rules apply in order to introduce a discipline that ensures undertakings from across the internal market. This is so they have the opportunity to compete for public contracts by removing legal and administrative barriers to participation in cross-border tenders, for ensuring equal treatment and by abolishing any scope for discriminatory purchasing through enhanced levels transparency and accountability.

The strategic importance of public procurement for the European integration process has been recognised by the 2011 Single Market Act which has prompted a series of reforms to the EU Public Procurement acquis. The Single Market Act relies on a simplified public procurement regime in the European Union, which will result from procedural efficiencies and from streamlining the application of the substantive rules. These reforms aim at linking directly public procurement with the European 2020 Strategy which focuses on growth and competitiveness. The current public procurement acquis has prescribed a different regulatory treatment to public sector procurement and utilities procurement, for two reasons. Firstly, a more relaxed regime for utilities procurement, irrespective of their public or privatised ownership has been justified and accepted as a result of the positive effects of liberalisation of network industries which has stimulated sectoral competitiveness. Secondly, a codified set of rules, covering supplies, works and services procurement in a single legal instrument for the public sector aims at producing legal efficiency, simplification and compliance in order to achieve the opening up of the relatively closed and segmented public sector procurement markets. A decentralised enforcement of the public procurement rules has been introduced by the Remedies Directives.

Judicial activism represents the most influential factor in the evolution of the public procurement acquis. The Court of Justice of the EU has contributed immensely to the deficiencies of the public procurement regime which has been experiencing conceptual and regulatory vagueness, limited interoperability with legal systems of Member States and continuous market-driven modality changes in financing and delivering public services. The EU Public procurement law has been moulded by the instrumental role of the Court of Justice of the European Union, which has provided intellectual support to the efforts of the European institutions to strengthen the fundamental principles which underpin public procurement regulation.

Featured image credit: EU Flagga, by MPD01605. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The EU and public procurement law appeared first on OUPblog.

November 30, 2015

Entering an uncharted realm of climate change

This year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference, the 21st annual session of the Conference of the Parties since the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the 11th session of the Meeting of the Parties since the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, will be held in Paris from 30 November to 11 December. Its objective is to achieve a legally binding, universal agreement for all nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and thereby limit an expected global temperature increase to 2°C (3.6° F) above pre-industrial levels.

Keeping the global surface temperature warming at 2°C represents a compromise between reducing the risk of dangerous climate change and the political challenges we face in controlling carbon dioxide (CO2) emission. Of course, many of the more serious impacts could be avoided by keeping the global surface temperature warming below 2°C, as the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) Third Assessment revealed as far back as 2001. Nonetheless, even mid-range emission scenarios project a global temperature rise of 2°C by the end of the twenty-first century. Is setting the temperature ceiling at 2°C safe? Scientists now understand that might not be the case, as the risk of severe impact is already significant. At the same time, the lack of political will from the United States and China, the largest emitters, has made even this goal difficult to achieve. In the meantime, atmospheric CO2 has soared to 398 parts per million (ppm) this year and will likely reach 400 ppm within a year.

What is required to keep global warming below the ceiling of 2°C? Stabilizing the atmospheric CO2 concentration at 400 ppm provides a relatively high chance to achieve this goal. If, however, atmospheric CO2 concentration grows to a somewhat higher level at 450 ppm, then our likelihood to achieve this goal falls to 50%. Evidently, we have already missed our first target due to inaction of the largest CO2 emitters since the 1997 Kyoto Protocol—the first agreement between nations to mandate reductions in greenhouse-gas emissions when the atmospheric CO2 concentration was less than 364 ppm. As a result, the next 15-25 years are likely to be our last chance to limit warming not too far beyond 2°C to avoid dangerous climate change. The success or failure of the Paris Climate Conference will determine whether or not the global community will seize this last opportunity to protect the Earth from entering a dangerous and uncharted realm of global climate activity.

If we fail to limit global temperature warming to 2°C, what will occur? First, we will face a much more uncertain understanding of climate, as discrepancies of future climate change projected by different climate models grow larger under stronger CO2 emission scenarios. What is certain, though, is fairly clear: global sea levels will rise and the cost of protecting coastal mega cities, where 44% of the global population lives, will escalate. While differences in sea-level rise may be relatively small in the 21st century (i.e., a rise 0.5-0.8 m by the end of the century), the sea-level rise caused by warming beyond 2°C would be much higher in the 22nd century—as the risk of irreversible melting of the western Antarctic ice sheet increases. Evaporation will gain in strength, reducing run-off that recharges river flows. More than 2°C warming can also maximize the stress we place on water sources in most river basins globally—as this higher degree of climate change would coincide with higher populations by 2060. Heat and water stress also would cause greater reductions in crop yields, even making rain-fed crops unsustainable in some areas, such as southern Africa.

Time to act is essential. So far, about a half of the CO2 emitted by humans has been absorbed by the ocean and terrestrial ecosystem, but the capacity for the ocean surface layer to dissolve CO2 decreases with warmer temperatures. Large-scale land use, especially in the tropics, releases the carbon previously stored in the soil and living biomass at a rate that largely offsets the CO2 uptake by the terrestrial ecosystem as a whole. Consequently, nature’s ability to absorb excessive atmospheric CO2 has been declining. Although thirteen out of fifteen of the hottest years globally have occurred since 2000, the rate of warming can further accelerate in the near future. Since 2000, the ocean may have temporally reduced the surface warming by transporting heat into sub-surface water layers. As oceanic variability changes its phase, the heat absorbed by the sub-surface ocean will re-surface, and amplify surface temperature warming. 2015 is on its way to become the hottest year ever recorded and may mark the beginning of a decade of even faster warming than in the past decade.

Furthermore, climate models tend to underestimate extreme climate anomalies. For example, the increase of dry season length over southern Amazonia during the past few decades is substantially larger than those simulated and projected by climate models. Thus, the risk of future climatic drying and die-back of the rainforests in that region can be higher than that projected by the IPCC Fifth Assessment published in 2013. The risk of collapse of the western Antarctic ice sheet is likely higher than we previously anticipated, leaving large coastal low lying areas such as Bangladesh, India, and mega cities such as New York and Shanghai more vulnerable to inundation and storm surges for future generations. These and other previously unforeseen higher climate risks further heighten the urgency of preventing CO2 concentration from reaching 450 ppm.

It is encouraging that the United States and China began tackling climate change together when they announced an agreement to curb carbon emissions last November. India and China also issued a joint statement on climate change that included a pledge to submit plans on their own carbon targets before the Paris conference. Together with the European Union, these commitments will in large part shape the future of the planet. While the Paris Climate Conference is unlikely to achieve its goal, it provides the best chance—since the UNFCCC’s launch more than 20 years ago—for a binding global agreement that will put us on track. As the former primary minister of Australia states “The people of the world, particularly the young, now look increasingly to the leaders of these great powers to protect our planet before it’s too late for us all.”

Image Credit: “Dry Riverbed” by Shever. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Entering an uncharted realm of climate change appeared first on OUPblog.

Climate change in the courts: challenges and future directions

The Dickson Poon School of Law, in collaboration with the Journal of Environmental Law, hosted a symposium on ‘Adjudicating the Future’ in September 2015. The symposium brought together judges, academics, and practitioners from around the world to consider the challenges and tasks for courts and tribunals in dealing with climate change issues. This post builds on that discussion, considering three themes that reflect challenges and potential directions for climate change litigation: the vexed question of what constitutes a ‘climate change case’, the justiciability of climate change cases in relation to standing of litigants, and the significant role of constitutional law in responding to climate change. In this fast-moving field, legal academics and legal experts have an important task, now and ahead, in reflecting on how adjudicative processes are accommodating the disruption that climate change inevitably brings to legal systems.

JB Ruhl has concluded that the task of trying to identify ‘climate change law’ is frustrating and elusive since ‘all fields of law will have to adjust’ in light of climate change. Climate change not only affects different areas of law, it also generates myriad legal disputes between various actors within and across legal orders. Cases involving climate change range from judicial review claims and negligence, to public nuisance actions and constitutional claims. In these cases, there is no typical litigant, no central legal question that defines climate change disputes, and no common remedy sought.

Despite this, there is intense academic and public interest in climate cases. This often relates to claims that could break new legal ground, sometimes through the use of existing legal concepts, such as the duty of care, in novel ways (see Urgenda v Netherlands). Other innovative claims are or might include: actions to challenge the investment decisions of pension providers on grounds relating to climate change impacts, actions to bring claims under the UK Climate Change Act 2008, or actions to develop a concept of shared state responsibility in public international law. However, arguments regarding climate policy can equally be pursued through well-established causes of action, such as claims in public nuisance or constitutional law, as discussed below. In fact, the common thread in climate change related cases is not their legal novelty but their reflection of underlying social upheaval threatened by climate change. This is not to say that all ‘climate cases’ are legally interesting – many are very mundane, as Kim Bouwer has thoughtfully explained – but they are inevitable and will often be socially significant.

However, whilst ‘climate change cases’ might reflect climate change conflicts, not all recognise the complexity of climate change. This can affect the justiciability of climate change cases, particularly as regards standing of litigants. Standing varies among different legal systems and often determines what kinds of roles courts can play in relation to climate change. Depending on the legal culture and adjudicative setting, standing can be restricted to those directly affected by a defendant’s action, to states, and to certain kinds of non-governmental organisations. Standing can be particularly problematic for public interest litigants and climate change ‘victims’, since climate change gives rise to different kinds of harm which may have not yet materialised or may be difficult to trace to particular action (see e.g. Kivalina v Exxon Mobil). However, while standing may act as a restraint on what courts can do, it can also provide opportunities for courts to interpret standing rules so as to accommodate the complex social interactions that can lead to climate change disputes. This approach was taken by Dutch and Pakistani courts in Urgenda v Netherlands and Leghari v Pakistan, allowing respectively an NGO, representing present and future generations, and a farmer engaging in public interest litigation, to bring cases against their governments.

Climate change and climate policy also raise a host of constitutional issues, including the opportunities for, and the constraints on, climate action in existing constitutions; the respective rights and duties of different levels of government (and, in a European context, the European Union); and the place of climate change in contemporary constitution-making, especially with respect to the constitutional rights of citizens. Furthermore, climate policy can justify interferences with non-environmental constitutional rights (as in Belgian constitutional law), and could even lead to the evolution of new constitutional jurisprudence, through the expansion of ‘environmental rights’ or the ‘constitutionalisation’ of key environmental statutes, such as the Climate Change Act 2008 (UK).

One example of a constitutional climate case is the recent Leghari case before the Lahore High Court, mentioned above. The petitioner farmer submitted that national and provincial governments had neglected their responsibilities to implement Pakistan’s national climate policy framework, offending the fundamental right to life under the Pakistan Constitution due to the existential threat posed by climate change. The Court found that ‘the delay and lethargy of the State in implementing the Framework offends the fundamental rights of the citizens’ and ordered the creation of a cross-sectoral Climate Change Commission to monitor climate policy implementation. Justice Shah identified a dynamic relationship between Pakistan’s constitutional order and the nation’s response to climate change: ‘Environment and its protection has taken a center stage in the scheme of our constitutional rights … The existing environmental jurisprudence has to be fashioned to meet the needs of something more urgent and overpowering i.e., Climate Change.’

Most national constitutions were adopted before the significance of climate change and its effects were widely understood. The contemporary adoption or amendment of constitutions may therefore represent a particular opportunity to address climate change. For example, Nepal’s new constitution, adopted in September 2015 amid ongoing controversy, includes a ‘right regarding clean environment’, which may be employed to address the effects of climate change in a ‘Least Developed Country’ that is particularly vulnerable to its impacts.

Issues relating to standing and constitutional jurisprudence are but two of the challenges that climate change represents for judiciaries. The negotiation of a new UN international law agreement on climate change obligations at the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) will likely only intensify the pressure on courts around the world to deal with climate disputes. As the imperatives of climate mitigation and adaptation grow ever more urgent, and climate disputes arrive more frequently in legal forums, judiciaries and advocates must accept these challenges with courage and evolving expertise.

Headline image credit: Briksdal Climate Change Norway by Djwosa. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Climate change in the courts: challenges and future directions appeared first on OUPblog.

New York City: the gastronomic melting pot

People from all over the world know New York City for a number of different aspects: the financial prowess of Wall Street, the outrageous cost of living, some of the best live entertainment you can find, among others. But for many of us, we’ve come to known New York City as the gastronomical delight that it is, and for the 8.4 million of us, it’s home. Garrett Oliver, the Brewmaster of the Brooklyn Brewery, weaves a nostalgic memory of food in his childhood in his foreword to the upcoming book, Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover’s Companion to New York City, edited by Andrew F. Smith.

My father was from New York City, and he made very sure that we were from New York City too. I was born in Queens, and no one in my family ever mentioned the possibility of living anywhere else. Although we were an African American family living in a largely African American neighborhood, when we were kids, we did not eat quite like other Americans.

My mother cooked white rice with sugar and butter, a holdover from our southern ancestors. Other nights we ate our spaghetti with butter, pepper, and a shake of “Parmesan” cheese, a recipe I later saw in my many trips to northern Italy. One night would be chili con carne, the next night “rice and peas.” Our neighbor, Mrs. Stafutti, would show up every Christmas with struffoli, a confection she referred to, somewhat less mellifluously, as “honey balls.” My great-aunt Emma often brought over her homemade “chopped liver,” and there was never even the slightest suggestion that it was Jewish in origin or that our neighbors had probably never heard of the dish. Then again, by my teens I had strong opinions about matzah ball soup and owned two yarmulkes—the “plain one” and the “fancy one”—for different styles of bar mitzvahs.

Aside from pizza, my favorite dish in the world was a concoction called “egg foo yong,” a sort of deep-fried omelet of dubious Chinese ancestry, full of onions and swathed in a glassy brown cornstarch sauce. On the way home from school, waiting for the bus, I would pick up brown paper bags of hot zeppoli covered in powdered sugar. As the oil soaked though the bag in splotches, I would empty the bag before I got home. And on weekends, my father and I would gather our dogs—proud, funny German short-haired pointers—and take them into the fields of Long Island and Westchester, looking for pheasant, quail, and chukar partridge. When we returned triumphant, I would end up cleaning the still warm birds, and then my father, an advertising executive, would mount them in a flawless white wine and cream sauce. I never found out where he learned how to cook like that. Nor did I ever learn where he had met his hunting friends, gruff but friendly guys, a few of whom had lost fingers to the machinery of local canning plants.

We did not think we were strange. We were New Yorkers. When I graduated from junior high school, we put on suits and ate at the swanky Chateau Henri IV at the Hotel Alrae on East Sixty-Fourth Street, a haunt of movie stars and illicit lovers alike. My father wanted us to be suffused with the life of the city, and as much as that meant museums and the arts, it also meant food.

The world abounds with great cities, but when it comes to food, there has never been another like New York City. A century ago, people in their millions did not arrive from far-off foreign lands to

make entirely new lives in London, Paris, Rome, Munich, Tokyo, or St. Petersburg. When I moved to London in 1983, London was almost entirely British. Yes, you could find good Indian and Pakistani food, and there was a thin smattering of Caribbean food around if you knew where to look. A few Jewish specialties were on the shelves of Golders Green. But London was British, and what you would largely find was English food, much of it gray. London has recovered nicely, but it is not Gotham. Even today, in a large city like Torino (Turin), Italy, home to 1.7 million people, you will find mostly Italian food—not even “Italian food” (a foreign construct that does not really exist) but Piemontese food. A great Thai restaurant will still be hard to find. More than a century

ago, those millions, hailing from dozens of countries, began to stream into Gotham, and they made it the greatest food city on Earth.

Cheese shop. Photo by Payton Chung. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Cheese shop. Photo by Payton Chung. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.In Lower Manhattan, in the late 1800s, you had choices. Was your family from Campania? Were you tired of Campanese food? All you had to do was take a walk, and you could visit parts of China or Germany. Make your way to Brooklyn, and you could eat in Norway and Russia and Sweden too. There were forty-eight breweries in Brooklyn alone, making 10 percent of all the beer in the country, and we had the most diverse beer culture in the world.

As the rest of the United States largely disappeared into the blandified world of highly engineered Frankenfood, a period from which the country is only now recovering, much of New York City held firm. Arthur Avenue did not hold truck with frozen “TV dinners.” Fresh seafood still wriggled in baskets in Chinatown. We ate Ukrainian pirogies at 4:00 a.m. after the East Village clubs closed. There were still a half-dozen places in Red Hook, Brooklyn, where you could order the swift demise of a live chicken for dinner that night. Jamaican jerk seasoning bubbled in pots a few miles away.

It is true: the city has changed, and things have been lost. Only in the mid-1990s, as I got off the L train in Williamsburg every morning, I could smell the smoke. Lenny Liveri, down the block at Joe’s Busy Corner, was smoking the freshly made mozzarella in a small box out on the sidewalk. By lunch, I would order that smoked mozzarella on a sandwich with prosciutto and pesto, while I listened to the little old Italian ladies verbally beat up the cowed, linebacker-sized Liveri brothers who were building epic sandwiches behind the counter. When the new bearded, tattooed kids started hectoring them for cappuccinos, in the afternoon, no less, the Liveris packed up and moved to New Jersey. They could not take it anymore—these kids. Joe’s Busy. Those were the days.

But these are the days too: the days of the Latin American food at Red Hook ball fields, the days of the Arepa Lady, the days of deciding what region of Thailand you want to eat in tonight, the days of great cocktail bars and dozens of breweries. We always had everything, and we still do. Eating in New York City has never been better than it is today, and a lot of the best stuff is not even expensive.

One day, some years back, I drove from Cap-Martin, France, over the Alps, into La Morra, Piemonte, Italy, to eat lunch. Lunch was brilliant, of course, and I was back in Cap-Martin by nightfall.

And I would still do that drive today. But in Gotham, you take such trips simply because you enjoy the journey. Here, at the center of the world, a universe of food is at your fingertips and always was. Between these pages are the many stories of our tables, millions strong, vaulting over centuries and into the future. Seek and ye shall find. Perhaps we New Yorkers are strange. Good thing, too.

Headline Image: NY Pretzel. Photo by cezzie901. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post New York City: the gastronomic melting pot appeared first on OUPblog.

HIV/AIDS: Ecological losses are infecting women

As we celebrate the 27th annual World AIDS Day, it is encouraging to note the most recent trends of worldwide reductions in new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths. However, the gains charted against the “disease that changed everything” are not equally distributed. In fact, the HIV/AIDS crisis has markedly widened gaps of inequality in health and wellbeing the world over. HIV/AIDS remains a leading factor contributing to health declines in poor nations, where over 95% of the 33.2 million individuals infected with HIV reside. The spread of HIV/AIDS has been especially detrimental to women in poor nations and, in fact, represents the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age. The number of women infected with HIV has increased dramatically in recent years—young women in less developed nations are about twice as likely as men to become newly infected with HIV. Theories of gender inequality provide clear insights into such dynamics, as a wide body of literature highlights the harmful consequences of inequalities in decision-making and control of or access to resources for women. In particular, women in less developed nations face barriers to many educational and health resources, including schools and contraceptives.

The deleterious combination of gender-based inequalities, poverty, malnutrition, lack of education, and inadequate health resources poses acute threats to the wellbeing of women in the less developed world; indeed, these factors are interconnected dimensions of strife that co-occur and exacerbate one another in ways that severely compromise the health and longevity of women in poor nations. What has been underexplored—and what we find to be a critical factor compounding the spread of HIV/AIDS among women—is the influence of environmental losses on women’s health. In short, environmental degradation exacerbates women’s rates of disease (HIV/AIDS) and death (lowered life expectancy) in myriad ways, as elaborated below.

HIV/AIDS, Women, and the Environment

The crux of the connection between women’s health and the environment largely centers on gender norms reflected in the household division of labor in which women are typically charged with providing vital resources to the household that are derived from the natural environment.

As we move forward and strive to eradicate the HIV/AIDS epidemic, we must recognize the strong connections between environmental degradation and the health and wellbeing of women.

Indeed, women supply the bulk of food, water, and other basic necessities for family members; as resource scarcity complicates these tasks, the health and wellbeing of the family is jeopardized and women themselves become increasingly vulnerable to disease. As one example, the productivity of women in less developed nations relies near exclusively on subsistence farming; thus declines in soil fertility and supplies of clean water compromise their ability to provide for themselves and the household. Environmental declines undoubtedly constrain food production and malnutrition potentiates susceptibility to many infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS. Women’s needs for such basic provisions are characteristically subsidiary to men’s, making them disproportionately vulnerable to malnutrition and associated declines in immunity when food and water are scarce. In some cases, severe hunger may increase the likelihood of risky sexual behavior and HIV transmission among women who resign to trading sex for needed household resources. Moreover, resource scarcity reduces the prospects for women to generate income from handicrafts and other cottage industries that rely heavily on natural resource inputs. The additional constriction to earning money posed by ecological decline worsens women’s health insofar as they become entrenched in poverty, which is consequential given the general view that poverty is a major culprit in perpetuating HIV transmission.

As women endeavor to fulfill their household duties in light of resource scarcity, they must travel longer distances over increasingly dangerous terrain to secure food, fuel, and fiber. Resource constraints that shift formerly inconsequential tasks, such as walking to a nearby source to draw water, to hours-long (or even days-long) searches are not only physically strenuous, thus directly impacting women’s health, but also place restrictive demands on women’s time that limit opportunities for educational and economic pursuits that would otherwise contribute to their empowerment. Additionally, there is accumulating evidence that high rates of HIV are found in areas with extensive contact with contaminated water—as supplies of clean water become increasingly scarce, women are more likely to come into contact with and, ultimately, resort to using water that is infested with worms and parasites that compromise overall health by intensifying susceptibility to and progression of life-threatening infections. This is particularly harmful to women as they are more likely to encounter contaminated water in the course of their daily lives and, as a result, experience urogenital inflammation that is a risk factor for HIV infection.

Empirical analysis of the dynamics outlined above confirms that women in less-developed countries are unduly harmed by ecological losses that exacerbate hunger, reduce the availability of public health resources, lower their autonomy, and contribute to the spread of HIV/AIDS and attendant reductions in female life expectancy. In this view, resource scarcity bears a wide range of deleterious effects on the health of women, thus informing our central conclusion that environmental losses are strongly associated with women’s health, in direct and indirect ways. This implies that developmental and epidemiological approaches to improving women’s health may benefit from incorporating environmental dimensions as a key area of concern.

The principal conclusions of our research center on the efficacy of incorporating ecofeminist frameworks into global perspectives on health, gender inequality, and the environment. As we move forward and strive to eradicate the HIV/AIDS epidemic, we must recognize the strong connections between environmental degradation and the health and wellbeing of women. Failing to account for the interconnected nature of these dimensions could lead to severely underspecified models. We strongly advocate that practitioners and policy makers seeking to address current health crises in poor nations adopt holistic approaches that account for the synergies among social, economic, and ecological dimensions.

Headline image credit: Woman watering crops Africa by skeeze. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post HIV/AIDS: Ecological losses are infecting women appeared first on OUPblog.

The need for immediate presidential action to close Guantanamo

Despite promising at the start of his presidency to close the prison at Guantanamo Bay, President Obama has yet to exercise the clear independent authority to do so. In a recent Washington Post op-ed, 2009 White House counsel Gregory B. Craig and Cliff Sloan, special envoy for Guantanamo closure 2013 and 2014, urged President Obama to abandon trying to get Congressional approval and simply use his direct Article II Constitutional authority to close Guantanamo and decide where and how the remaining detainees who have not been cleared for release would be charged and tried. 107 detainees remain and of these 48 have been cleared for release; 10 face serious criminal charges and are to be tried before military tribunals.

The question is not whether the president can unilaterally take the nation to war or hold detainees without congressional authorization. The question is whether Congress can tell the president where military detainees must be held and tried. Craig and Sloan say the answer is an emphatic “no”. Congress’s purported ban on funding any movement of detainees from Guantanamo Bay to the United States restricts where law-of-war detainees can be held, and attempts to prevent the president from discharging his constitutionally-assigned function of making tactical military decisions. Accordingly, the Congressional ban on prisoner transfers violates the constitutional separation of powers.

In a 20 November 2015 Washington Post editorial it is argued that Obama cannot act alone and he must attempt to work with Congress. However, the editorial has no value as it ignores the controlling law embodied in Article II of the Constitution with its specific mandates.

“The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.”

US Constitution Article II, §1

“The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and the Navy of the United States …[.].”

US Constitution Article II, §2

The failure to close Guantanamo and the consequent injury to the Rule of Law does not begin or end only with President Obama. Commencing in 2010, the Republican majority in the House of Representatives has opposed every initiative of the administration, without exception, with no meaningful attempts to seek alternatives. It appears their principal goal is to cripple and ultimately destroy President Obama’s administration, reputation, and legacy.

Thus far, the Republican majority’s assault on the executive branch of the government compromises the president’s ability to govern and is in stark contrast to the Republican complicity in the unprecedented unitary executive power exercised during the Bush administration. There are historic parallels to the far right’s rhetoric, domestic obfuscation, and international jingoism in American social and political history. The current Republican behavior mirrors that of the Southern Democrats in the Congress immediately prior to the United States Civil War and the anti-Communist extremism of the McCarthy era in the 1950s. Republican governors in some states now even openly speak of nullification of federal law and secession. As a result, Congress has been rendered virtually useless in its duty as a partner in protecting the Rule of Law in the many instances where it is under attack. This dysfunction is rare but not unprecedented. The far-right opposition to any informed or nuanced discussion of the fundamentals of government is basic to understanding the context within which the Obama administration must pursue its constitutional and political initiatives. But these impediments Obama faces do not excuse his failure to take or avoid condoning many actions that are within his explicit executive authority. If the President continues on this course, he will have forfeited the opportunity, responsibility, and constitutional obligation to take historic actions in defense of the Rule of Law.

When the Bush administration created the Guantanamo prison for terror detainees, it made no prior announcement. By the time photographs of the sensory deprived and shackled prisoner were revealed to the public, it was a fait accompli. In contrast, President Obama’s first White House counsel Gregory Craig’s efforts to close Guantanamo were disclosed to the public in advance, including details of the specific substitute prisons in the United States for housing Guantanamo detainees and an announcement that the detainees would be charged criminally and tried within the civil courts of the United States. President Obama permitted these disclosures rather than simply proceeding with no fanfare. This may have been stimulated by the fact that he was new to power, desired a bipartisan presidency, and was unaware of the Republicans’ oath to oppose any and everything he presented to the American public. Senate minority leader Mitch O’Connell, announced on the day of Obama’s first inauguration that job number one was to prevent Obama from having a second term. Congressional Republicans would not be a loyal opposition but rather would take the role of disloyal saboteurs. Whatever Obama wants, they oppose. This continues today.

Reportedly, the Pentagon is sending evaluation teams to assess several military and federal prisons as possible replacements for Guantanamo Bay, but it remains to be seen whether the plan the Defense Department presents to Congress will win bipartisan support. Once again, President Obama is apparently simply hoping he can persuade lawmakers to help him close Guantanamo despite the fact that Congress seems determined to prevent it. Obama needs to act, not discuss wishful plans. Undoubtedly, Republicans will very soon be arguing that the recent terrorist attacks in Paris justify the continuation if not the expansion of Guantanamo.

Featured image: Satellite picture of Guantanamo Bay. Photo by NASA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The need for immediate presidential action to close Guantanamo appeared first on OUPblog.

Wine and DNA profiling

Since the advent of DNA profiling of grape varieties in 1993, classical ampelography (gr. ámpelos=vine and lógos=study) has been significantly shaken up. Here is a short overview of the impact of DNA studies on wine:

Wrong labelling

In ampelographic collections, about ten living plants of each grape variety or clone are kept alive for future studies or plantings, which requires a large amount of time and money. Yet, in every collection we estimate an average of 5% of labelling errors. They can now be identified with DNA profiling and duplicates can be eliminated, thus saving time and money.

For example, at the United States Department of Agriculture’s National Clonal Germplasm at Davis in California, Mondeuse Noire from Savoy (France) was long confused with Refosco dal Peduncolo Rosso from Friuli (Italy). Thanks to DNA testing that false identification was put to an end.

In Australia, the grape variety imported from Spain and spread under the name Albariño turned out to be an earlier labelling error in a collection in Galicia (Spain), as it was recently identified as the Savagnin Blanc, to the chagrin of producers who had to correct their marketing strategy. (While I understand the promotion issue, I find this rather good news given the high esteem that I have for the wines made of Savagnin, especially Heida from Switzerland and Vin Jaune from the Jura!)

Synonyms and homonyms

DNA profiling can unexpectedly identify or reject synonyms. For example, the famous Zinfandel from California was long suspected to be identical to Primitivo from Puglia (Italy), which was confirmed by DNA profiling. After a long DNA research nicknamed the “Zinquest”, it was established in 2001 that this variety is native to the Dalmatian coast where it is unofficially called Crljenak Kaštelanski. More recently, in 2011, DNA profiling of a 90-year-old herbarium sample from Dalmatia enabled the identification of the official and historical name of this grape variety: Tribidrag.

Another example, Altesse from Savoy (France) has long been identified with Furmint from the Tokaj region in Hungary, which was conclusively refuted by DNA testing.

Gouais Blanc, the “mother of all grapes”. Photo courtesy of José Vouillamoz.

Gouais Blanc, the “mother of all grapes”. Photo courtesy of José Vouillamoz.The same name can be inadvertently given to different varieties, resulting in what we call homonyms. For example, in Spain several varieties are all called ‘Albillo Something’; the same happens in several countries with Barbarossa Something’ and ‘Schiava Something’ in Italy; and ‘Muscat Something’ or ‘Malvasia Something’ in a number of Mediterranean countries. Yet in may cases these different varieties are in fact not genetically related. Thanks to DNA profiling, these homonym confusions can be solved.

Parentage

DNA paternity testing has revealed several unexpected parentages. The first and most surprising was discovered in 1997 by Prof Carole Meredith and her PhD student John Bowers at the University of California in Davis: Cabernet Sauvignon was shown to be a natural, spontaneous crossing between Cabernet Franc and Sauvignon Blanc, which no one had ever suspected. Since then, other parentage discoveries have debunked some popular legends and have shed some light on the true origins of famous grape varieties: Merlot is a half-brother of Cabernet Sauvignon, because it was found to be a spontaneous progeny of Cabernet Franc and an almost extinct variety named Magdeleine Noire des Charentes; Chardonnay and Gamay from Burgundy are two brothers born from natural crossings between Pinot Blanc and Gouais Blanc, the latter an obscure variety that has been banned in France since several centuries; Syrah is a natural offspring of Dureza from Ardèche and Mondeuse Blanche from Savoy; Sangiovese is half Tuscan and half Calabrian since it is a natural progeny of the Chianti grape variety Ciliegiolo and Calabrese di Montenuovo, an obscure variety from Calabria, etc. Last but not least, the parentage of Tempranillo, the most important variety in Spain, was discovered after the release of my book Wine Grapes (co-authored with Jancis Robionson and Julia Harding).

Some books will tell you that Tempranillo was introduced into Spain by the Cistercian monks of the Abbey of Cîteaux in Burgundy, and that it is possibly a distant cousin of Pinot which took the pilgrim route to Santiago de Compostela. I suggest that you close these books. In 2012 this legend was invalidated with the discovery of the parents of Tempranillo: it is a natural crossing between Albillo Mayor, an old variety form Ribera del Duero where Tempranillo is historically known as Tinta del País (red of the land), and an obscure and almost extinct variety from Aragon called Benedicto, of which we practically know nothing. The crossing must have taken place somewhere between Aragon, Rioja, Castile y León and Navarre, before the first mention of Tempranillo in Rioja in 1807.

Classical ampelography and DNA profiling are complementary sciences whose synergy allows us to better understand the migrations of grape varieties, as well as their kinship, providing a better understanding of the future of wine growing.

The post Wine and DNA profiling appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers