Oxford University Press's Blog, page 577

December 8, 2015

Hope from Paris: rebuilding trust

It has begun again: the age-old cycle of hate and counter-hate, self-justification and counter-justification, the grim celebrations of righteousness and revenge. In the US, conservative politicians play on it as demagogues always have, projecting strength and patriotism by refusing to take refugees from the lands terrorized by ISIS; my own governor, Chris Christie, tries to outdo his competition by arguing that even five-year-old orphans from Syria should be stopped and sent back, as if they are tainted by being from the same part of the world as the murderers. In France, anti-Muslim sentiment is said to be rising. Everywhere people want to shut down, to cling to people like themselves whom they can trust, to build walls against people unlike themselves.

We know some things about these cycles. We know with the scientific confidence of good evidence and good theory, that they breed ever-deepening spirals of violence and hatred. ISIS draws its strength from the suspicion and mistrust of Muslims in the West, like a malignant antihero drawing energy from its enemy. It will only grow as our hostility spreads to millions of innocent people tarred with the broad brush of prejudice.

But ISIS is no hero to Muslims. The overwhelming majority among them, by all indications, abhor the attacks in Paris and the brutality of the movement. That is why millions are fleeing to our shores. ISIS can be defeated with ease, but only — only — if Muslims as a whole feel the West is a friend, feel we support their efforts to build better lives for their families.

Amid the heartbreak and terror, amid the recriminations and bombast, there is some reason for hope.

There has been a substantial outpouring of support for Muslims in Paris, on social media, and in the streets – expressions of empathy, concern that they not be demonized. Messages of support have gone viral in social media. A New Yorker named Alex Malloy wrote on Facebook of getting a Muslim cab driver the day after the attacks who wept, from despair and fear that he would be labeled as one of “them.” Malloy’s response drew wide support:

Amid the heartbreak and terror, amid the recriminations and bombast, there is some reason for hope.

“Please stop saying ‘Muslims’ are the problem because they are not and they are feeling more victimized and scared to the day. These are our brothers and sisters as humankind, we are all humans underneath this skin. And they deserve nothing more than our respect and attention. They need our protection. Please stop viewing these beautiful human beings as enemies because they are not.”

And a young Parisian (My nephew, Benjamin Heckscher, also on Facebook) wrote, “This is not really about ISIS … This is about ignorance, insecurity, emotion. It’s about not understanding who other people are, what they want or how they feel.”

This reaction of empathy and understanding is extraordinary. In the past, only small pockets of cosmopolitan elites have been willing to reach out in this way to the ‘other’, beyond the tribe. But now the desire for understanding of others has spread widely, especially of the young who have grown up with the rich exchanges of the internet. It has, for perhaps the first time in history, extended far enough to become a credible counterweight to the ancient, and still strong, tendency to close ranks against an enemy.

We will not make friends with ISIS itself, and it would be folly to try; there is a need for fighting. But we do need to seek friendship with the vast Muslim population who hate ISIS but also feel themselves as aliens in the West. For that, we need to avoid succumbing to the sweet temptations of tribal loyalty, the marching bands and self-congratulatory speeches. As great leaders like Abraham Lincoln well knew, fighting may be necessary but there can be no joy in it: we should empathize with our enemy even as we enter combat, so that when the opportunity for peace comes we know how to seize and build on it.

Meanwhile, we must from the instinct of self-preservation, as well as from the generosity of our best selves, reach out to Muslims wherever we can, welcome them, celebrate their desire for peace and good lives. Together we can clear the poisonous swamps where hatred breeds. We don’t want to get dragged into them ourselves.

Headline image credit: The Eiffel Tower lit in blue white red – Fluctuat nec Mergitur by y.caradec CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Hope from Paris: rebuilding trust appeared first on OUPblog.

Chag Urim Sameach! A Hanukkah music playlist

Music has a long tradition of being associated with winter holidays, something we’re mindful of in the music department of Oxford University Press. As Hanukkah is already in full swing, we asked members of our editorial, marketing, and publicity departments for their favorite Hanukkah songs. Their selections represent a mix of traditional music (such as an eighteenth century choral arrangement of “Maoz Tsur”), modern interpretations (“Hanukkah, O Hanukkah” by the Barenaked Ladies), and originals (“I’m Spending Hanukkah in Santa Monica” by Tom Lehrer). We hope our choices, featured below, encourage you to have a wonderful, musical Hanukkah celebration!

“Ocho Kandalikas” by Maxwell Street Klezmer Band

“One of my favorites is a Ladino song called “Ocho kandelikas.” Here is an entertaining performance by the Maxwell Street Klezmer Band.”

—Suzanne Ryan, Editor-in-Chief, Academic/Trade Humanities

“Chanukah (Shake It Off)” by Six 13

“My sister (a kindergarten teacher) is thinking of using this video to teach her kids about Hanukkah.”

—Helena Palmer, Marketing Assistant, Academic Central Marketing

“How Much Is That Pickle in the Window” by Mickey Katz

“My favorite: “How Much Is that Pickle in the Window” by Mickey Katz. Not totally seasonable but still a classic. Particularly the Klezmerish ending, featuring Katz blowing a mean clarinet.”

—Richard Carlin, Editor, Higher Education

“Eternal Light” by Kenny G

“Have you heard ‘Six 13 Chanukah (Shake It Off)’? It’s on Spotify and pretty cute. Other thoughts: ‘Eternal Light’ by Kenny G and the Glee version of ‘Hanukkah, Oh Hanukkah.'”

—Estelle Hallick, Associate Publicist

Kenny Ellis’s Swingin’ Dreidel

“My knowledge of Hannukah music stems primarily from directing a small a cappella choir years ago. We used to sing a lot of holiday parties and were generally called on to have some Hannukah songs at the ready. Mostly we did some assembly of the big three: ‘The Dreidel Song’ (Here’s a Sinatra inspired arrangement ‘Swingin Dreidel’ by Kenny Ellis), ‘Maoz Tzur,’ and ‘Hannukah, O Hanukkah.’ But some non-traditional favorites: ‘I’m Spending Hanukkah in Santa Monica,’ ‘The Hanukkah Song,’ and ‘Latke Recipe.'”

—Anna-Lise Santella, Senior Editor, Online Products

“Maoz Tsur” by Benedetto Marcello

“Hanukkah, O Hanukkah” by Barenaked Ladies

“Hanukkah in Santa Monica” by Tom Lehrer

“The Hanukkah Song” by Adam Sandler

“Latke Recipe” by the Maccabeats

Image Credit: “Hanukkah Lights” by Tim Sackton. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Chag Urim Sameach! A Hanukkah music playlist appeared first on OUPblog.

The Uber dilemma: are “crowd-work” platforms employers?

Emerging technologies present us with many opportunities – as well as difficulties, particularly when their everyday impact collides with long-established institutions and frameworks. Here, Jeremias Prassl explains how the apparent organizational novelty of these emerging services may not be the positive force it appears to be, and suggests that new operators and platforms should not be exempt from the legal constraints which bind their competitors.

The law has long struggled to adapt to new forms of employment – who should be responsible for the protection of workers’ rights, from minimum wage and working time to discrimination law, in today’s fragmented economy? These fundamental questions are now returning to public discussion as a result of the meteoric rise of so-called “crowd-work”, where online platforms match individual workers and customers to perform ‘gigs’, ‘rides’, or ‘tasks’.

Leading crowd-work platforms have already become household names: think of Uber for taxi drivers, Amazon’s Mechanical Turks for digital services, and TaskRabbit for domestic work.

Their proposition is enticing: as a customer, your driver, secretary, or handyman is but a few clicks away. Initial vetting and a continuously updated rating system ensure high quality standards, as customers are asked to leave feedback for each task performed. As a worker, you will be able to find work wherever it is available, in a fully flexible way to suit individual schedules, and using tools already at your disposal.

The reality behind crowd-work, on the other hand, is often one of precarity and exploitation: Uber drivers risk driving long hours without earning minimum wage levels, and will find themselves barred from the platform if their rating falls below a (high) threshold; Mechanical Turkers often struggle to be paid even for work they have already completed.

The reality behind crowdwork, is often one of precarity and exploitation.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, therefore, lawsuits have begun to spring up around the world – from Uber’s home in California to several European countries, including most recently the United Kingdom.

The question at stake is invariably similar: can electronic platforms be considered the employer of their ‘partners’, ‘taskers’, or ‘turks’? It is only once that question has been answered in the affirmative that workers will be able to enjoy key rights such as the minimum wage or working time protection. A string of recent decisions in the United States has already recognised Uber ‘partners’ as employers; with the help of the GMB trade union, a number of drivers have now launched similar claims before Employment Tribunals in the United Kingdom.

Uber’s official position is to assert that the platform merely acts as an agent for individual drivers (or ‘transport providers’), and cannot therefore be characterised as their employer. From a lawyer’s perspective, however, this assertion is of little importance: UK Courts have long accepted that employment is characterized by the reality of the underlying relationship, rather than any label chosen by the parties.

Over the course of the last century, employment law has instead placed a range of duties on those with the power to hire and fire workers, to control their daily work and pay, and to sell the products of their services on the open market at predetermined rates.

The key question in upcoming domestic litigation will therefore be the extent to which Uber has exercised a series of core employer functions identified in the case law. An increasing number of online resources provide insights into the reality of the relationship between the platform and its drivers: through its app, the platform has close control over the routes drivers are to choose and the prices customers will be charged for each ride. All financial transactions take place via the app, which also sits at the core of Uber’s rating system, enlisting customers to act as the platform’s agents in monitoring worker performance. Even the supposed freedom to work when and as desired is mostly illusionary: ratings are carried from engagement to engagement, and a refusal to accept a series of offers will soon have an impact on a driver’s ratings.

In my mind, there is therefore little doubt that despite the platform’s resistance to bear key responsibilities, Uber should be classified as the employer of its drivers, thus guaranteeing each driver access to her fundamental worker rights in English law. Even customers will profit from such a decision: well-rested workers will be much safer drivers, and in the unhappy event of an accident or other problems, they too will be able to assert their claims for reparation against the employing platform.

Featured image credit: Untitled by Arvind Grover, CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Uber dilemma: are “crowd-work” platforms employers? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 7, 2015

The Little Sisters, the Supreme Court and the HSA/HRA alternative

The Little Sisters of the Poor, an international congregation of Roman Catholic women, are unlikely litigants in the US Supreme Court. Consistent with their strong adherence to traditional Catholic doctrines, the Little Sisters oppose birth control. They are now in the Supreme Court because of that opposition.

Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the regulations promulgated under the ACA, employers with 50 or more employees must provide medical coverage, which includes birth control devices and medications. The regulations under the ACA, colloquially known as Obamacare, exempt churches from providing contraceptive coverage to their employees without requiring such churches to affirmatively elect such exemption. However, these regulations require religious nonprofit organizations like the Little Sisters to affirmatively elect against contraceptive coverage for their employees.

In particular, the ACA regulations require a non-church sectarian entity like the Little Sisters to inform one of three persons that the entity declines to provide birth control to its employees. Under the regulations, a non-church religious organization declining to offer birth control can notify its health insurance carrier or, if the organization self-funds its employees’ health coverage, the organization can inform the administrator of that self-funded coverage. Alternatively, under the ACA regulations, a non-church religious employer can notify the Department of Health and Human Services of the employer’s refusal to provide contraceptive coverage to its employees.

The required notification excuses the objecting religious organization from providing birth control to its employees. The notice also triggers a process to enable these employees to receive birth control coverage without the employer’s involvement.

The Little Sisters criticize this opt-out provision, arguing that, by complying with the regulations, the Little Sisters are triggering birth control coverage for their employees. The Little Sisters’ criticism is joined by other similarly-situated sectarian organizations including East Texas Baptist University and Southern Nazarene University. These non-church religious objectors argue that requiring them to file opt-out notices violates their rights under the First Amendment of the US Constitution, as well as their rights under the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).

The US Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit rejected the Little Sisters’ arguments against the regulatory requirement that they affirmatively elect against contraception coverage for their employees. The US Supreme Court has now agreed to hear the arguments of the Little Sisters and of the other non-church religious objectors asserting the same rights under the First Amendment and RFRA.

As I recently observed in the Rutgers Law Record, an alternative approach can obviate the conflict reflected in the Little Sisters’ litigation while preserving the rights of all employees to spend employer-provided medical reimbursement dollars as they wish. In a nutshell, any religious employer objecting to any otherwise ACA-mandated item of medical coverage should have the right to instead fund an independently-administered health savings account (HSA) or health reimbursement arrangement (HRA) for each of its employees. Any employer maintaining HSAs or HRAs for its employees could then decline to offer its employees any particular form of medical coverage to which the employer objects on religious grounds.

Employees can use their employer-provided HSA or HRA funds to purchase any medical service or device they want—in the same way such employees can use their cash wages as they please. Just as an employer has no control over an employee’s decisions to spend his wages as he chooses, an employer has no control over an employee’s expenditures of his independently-administered HSA or HRA funds. HSA/HRA funds are wages controlled by the employees, except that HSA/HRA funds are not included in employees’ gross incomes and must be spent on medical outlays.

Under this proposed approach, an employee of the Little Sisters who desires extra prescription eyeglasses could use her HRA or HSA for that purpose—while her co-worker could use that account to obtain birth control. In neither case would the Little Sisters (or any other similarly sincere religious employer) participate in the employee’s decision regarding how to expend health care account dollars.

The Little Sisters and their supporters might retort that providing HSAs and HRAs still implicates them in the contraceptive services an employee can obtain with her HSA or HRA funds. However, that employee can use her cash wages to purchase such services. Employers cannot veto their employees’ use of their wages. The funds put into HSAs and HRAs are no different; they are wages which belong to the employee to spend as she sees fit on medical care the employee desires. An employee’s decision how to spend her HSA or HRA funds is the employee’s decision, not the employer’s.

At the other end of the spectrum, some women’s health advocates might argue that a tax-advantaged account is an inadequate replacement for employer-financed contraception coverage. However, in a defined contribution culture such as ours, tax-favored 401(k) accounts are how we save for retirement, tax-favored 529 accounts are how we pay for college, tax-favored transit accounts are how we pay for parking and commuting costs—and tax-favored HRAs and HSAs are increasingly how we purchase medical services.

The Little Sisters’ work is admirable and their views are sincere. Similarly sincere are those who believe that employer-provided medical coverage should include contraception services to which the Little Sisters object. A society that respects religious conscience and individual autonomy should accommodate both these concerns. The HSA/HRA option is the best way to reconcile these contrasting views in a civil and respectful way.

Image Credit: “Ritual” by Monik Markus. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Little Sisters, the Supreme Court and the HSA/HRA alternative appeared first on OUPblog.

Rethinking the “accidents will happen” mentality

Canadians have a vast lexicon of phrases they use to diminish accidents and their negative consequences. We acknowledge that “accidents will happen,” and remind ourselves that there’s “no use crying over spilled milk.” In fact, we’ve become so good at minimizing these seemingly random, unpredictable incidents that they now seem commonplace: we tend to view accidents as normal, everyday occurrences that everyone will inevitably experience at some point.

Despite its pervasiveness, this outlook is deeply flawed, and even dangerous. Decades of research by statisticians, public health researchers, and actuaries show that the events we consider “accidental” are, in fact, socially patterned. Recognizing these patterns makes for a more cautious culture where fewer people are subjected to pain, injury, and even death “accidentally.”

Indeed, one of the primary predictors of unexpected injury is place, so we begin by mapping out the various “hot spots” in which these incidents are most likely to occur:

1. At Home

Staircases, kitchens, and bathrooms see a disproportionate number of unexpected injuries and deaths, leading us to refer to these sites as constituents of “hazardous homes.”

2. At Play

One of Canada’s two national sports, hockey, is also a leading cause of head injury – perhaps understandably, as players fly across the ice at up to 50 kilometers per hour, trying to avoid the boards, goal posts, and each other.

3. At Work

A brief history of labour from the assembly line workers of the Industrial Revolution to the construction workers of today reveals the hazardous nature of many workplaces.

4. On the Road

We’ve long known that driving under the influence or amidst distractions increases one’s chances of crashing. We explore the sociological factors that often inspire such poor decisions, but also delve into collision-predicting structural issues, such as poor lighting, disrepair, construction, congestion, flawed road design, and a lack of reliable, affordable public transportation.

Image credit: Car accident by daveynin. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Car accident by daveynin. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Accidents thus tend to cluster in these inherently dangerous spaces, but certain “types” of people are more likely to suffer their consequences than others. Homes, for instance, are particularly hazardous for the very young and the very old, as these groups spend the majority of their time here. Similarly, those fundamentally dangerous types of work – such as construction, firefighting, manufacturing, mining, and so on – tend to be performed by men, while women generally occupy safer clerical and secretarial positions.

But in addition to being exposed to physical threats more often, certain groups behave in riskier ways that predispose them to unexpected incidents: children, for example, have yet to learn the pain associated with injury, and therefore rarely make efforts to avoid it. And from the moment they are born, men and women are socialized to behave in different ways, with men more often engaging in risk-taking activities that are meant to signal their masculinity. We propose then that “accidents” are not accidental at all: they happen when certain kinds of people act in risky ways in hazardous places.

Despite all of these situational and demographic variables that reliably predict unexpected injuries, most continue to rely on the notion of “accident proneness” as an explanation for repeat injuries. Clearly, from what we have already discussed, certain groups of individuals sustain more injuries than others. But by labelling these people as “accident prone,” aren’t we merely just stating the facts – highlighting the number of mishaps they experience, as opposed to exploring the reasoning behind those incidents?

Ultimately, unexpected injuries and deaths pose a financially and emotionally costly problem for our society as a whole. These potentially devastating incidents are the results of our long-standing social structures: the culture of masculinity, the economics of profit-making, the politics of deregulation, and the cult of efficiency. Our society is programmed to generate accidents, and individual people suffer the consequences. Only by understanding their underlying causes can we work to reduce their occurrence.

Featured image credit: Emergency room entrance by M.O. Stevens. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Rethinking the “accidents will happen” mentality appeared first on OUPblog.

Judgments on Genocide from the European Court of Human Rights

In the space of less than a week, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights issued two lengthy judgments relating to the crime of genocide. The 17-judge Grand Chamber is the most authoritative formation of the European Court, and in recent years the Court has found itself compelled to address a range of issues relating to the prevention and punishment of international crimes.

In Perinçek v. Switzerland, the applicant, a Turkish extremist, had provoked prosecution under Switzerland’s genocide denial legislation by contesting the label that is given to the 1915 massacres of a million Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. He claimed this violated his right to freedom of expression, enshrined in article 10 of the European Convention of Human Rights.

Perinçek had already been successful before the seven-judge Chamber, but, pressed by Armenian organizations unhappy with the initial ruling, Switzerland applied for leave to have the case revisited by the Grand Chamber.

That was probably a mistake.

Not only is the ruling by the Grand Chamber more authoritative, it also clarifies matters in the first ruling that it would have been better to leave ambiguous.

The Grand Chamber majority declined to take a position on whether or not the 1915 massacres should be described as genocide. If there was any doubt about the point, the dissenting judges hammered this home. By insisting upon using the term in the eloquent introduction to their minority opinion, they highlighted the silence of the majority on the point.

The Grand Chamber essentially condemned all legislation criminalizing the negation of historical truth, giving free speech free reign. (The Holocaust is the only exception, it said, because its denial, “even if dressed up as impartial historical research, must invariably be seen as connoting an antidemocratic ideology and anti-Semitism.”)

Speaking of the “time factor,” the Grand Chamber took the view that as the years pass, the anger and outrage of victim groups, and their entitlement to special consideration, diminishes. This is in line with other recent rulings of the Court, notably its rejection in 2013 of an application by Polish survivors of the Katyn massacre of 1940 (Janowiec et al. v. Russia).

The second of the Grand Chamber judgments, Vasiliauskas v. Lithuania, concerned the killing of anti-Soviet insurgents in the early 1950s. A former KGB agent, Vasiliauskas was convicted in 2004 for the crime of genocide of political groups; however this was based on laws passed in the 1990s. He applied to the ECHR, claiming his crimes only became “criminal” 40 years after they were committed, invoking the “principle of legality” set out in article 7 of the Convention.

Modern genocide legislation generally speaks of destruction of a “national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” But some States have opted to add other groups to the list, including political groups.

The Vasiliauskas case hinged on the definition of the crime in the 1948 Genocide Convention. Modern genocide legislation generally speaks of destruction of a “national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” But some States have opted to add other groups to the list, including political groups. This raises no legal problem unless, of course, the legislation is applied retroactively.

The United Nations General Assembly, in a 1946 resolution, recognized that political groups were protected by the international criminalization of genocide. But when it adopted the text of the Genocide Human Rights Convention two years later its members voted to exclude political groups. Although the intentional physical destruction of political groups was not included in the Convention definition, it can hardly be claimed that they had intended to deem this to be innocent conduct, undeserving of prosecution.

The applicants in both cases were successful, but by the narrowest of majorities. In the Perinçek case, the vote was 10 to 7. In Vasiliauskas, the margin of victory was as thin as it can be: 9 votes to 8. The dissenters in Vasiliauskas seemed a lot angrier than those in Perinçek. One of them spoke of “this miserable judgment.” Another described the majority ruling as “lamentable.” There is inevitably much discontent about both judgments, as they deal with issues of great political sensitivity.

Judgments like these, where the judges are so bitterly divided, highlight the difficulty and complexity of the issues being considered but leave us with little certainty about how similar cases will be resolved in the future.

Featured image: European Court of Human Rights. Photo by James Russell. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Judgments on Genocide from the European Court of Human Rights appeared first on OUPblog.

Renaissance of the ancient world

The Eastern Mediterranean, comprising Cyprus, Greece, Israel, Lebanon, and Turkey, is politically one of the most divisive regions in the world. Greece and Turkey have had their historical differences; the tiny island of Cyprus is still divided and Israel and Lebanon’s last altercation happened all too recently disrupting the harvest in the Galilee and Bekaa Valley respectively. These are the only wine regions in the world divided by borders of war and religion.

However, there are similarities that unite them culturally as being part of the Eastern Mediterranean. Visit a restaurant in any of these countries and you will find mezze being served on small plates. They will more often than not be accompanied by the indigenous spirit, Arak, Raki, or Ouzo. The whole area also has a well-established coffee culture too, linked to the generous local hospitality. Strong coffee is served in small cups.

Another common factor is wine. This area was the cradle of the grape, that gave wine culture to the world, long before the vine reached the rest of Europe. The history, archaeology, literature, religious ritual, and folklore bear witness to a very advanced wine industry, which was a mainstay of the economy and an important part of the lifestyle.

In the 19th century, wineries like Achaia-Clauss, Boutari, Carmel, Etko, and Ksara introduced modern wine industries in their respective countries. Doluca and Kavaklidere followed suit in the 1920’s. However until the late 20th century, the region was considered out of step with the technological advances made elsewhere. Greece was primarily known for Retsina. Cyprus produced bulk wines and ‘sherries’. Israel was associated with sweet, kosher wines. Lebanese wines were mainly found in Arab restaurants and Turkish wines in kebab fast food kiosks. The wines were pretty dire, apart from Commandaria, Retsina, and Vinsanto, which remained as historic time capsules to remind us of winemaking in ancient times.

The stirrings of a quality revolution started with three famous names. Domaine Carras from Greece employed the expertise of Bordeaux guru Emile Peynaud. Lebanon’s Chateau Musar caught the world’s attention, being from a most unlikely source and but also due to the charming owner, the much missed Serge Hochar. Yarden introduced New World technology to Israel. These three pioneers were the catalysts that triggered a whole series of changes in their respective countries.

Judean Hills harvest. Photo courtesy of Ranbi. Used with permission.

Judean Hills harvest. Photo courtesy of Ranbi. Used with permission.Firstly, there was an influx of expertise. The Greeks and Lebanese were mainly influenced by France; the Israelis more by California and Australia. Secondly, there was an explosion of new boutique wineries and then the larger wineries responded to the new situation by diversifying and investing in quality. Greece and Israel led this boom, Lebanon was not far behind, and Cyprus and Turkey are the most recent to join this regional trend.

Today, these countries are making wines far removed from their old image. Worth seeking out are the white wines from Greece, especially the minerally Assyrtiko and aromatic Moschofilero. As for reds, the Lebanese blends, often based on Cabernet Sauvignon & Syrah, and Israel’s Mediterranean Rhone style blends and varietal Shiraz, together illustrate the revival of the Levant as a quality wine producing region.

If you want more ethnic flavors, there is no lack of local varieties such as the Turkish Bogazkere, Okuzgozu and Kalecik Karasi, the Greek Xinomavro and Aghiorgitiko, and or the Cypriot Maratheftiko. The Lebanese have their Merweh and Obeideh. Israel lacks wines from indigenous varieties, but if you are looking for more unusual varieties, there are some particularly good Israeli Petite Sirahs.

Regarding this part of the world, it is wise to maintain an open mind and keep learning. Scratch the surface and there are no end of surprises such as Syria’s excellent Domaine Bargylus and the intriguing wine made by Cremisan Monastery from two Palestinian varieties, Hamdani and Jandali.

The Eastern Mediterranean has reawakened after being asleep for 2,000 years. It is now a fascinating wine region with a perfect climate, high elevations, unique terroir, indigenous varieties and advanced technology in vineyards and wineries. Experts compare New World and Old World wines. This region represents the Ancient World.

The Eastern Mediterranean is today making exciting wines that are sought for their quality, originality and the fact that they come from the world’s ‘newest’ quality wine region. For the first time it may be said that the long history of winemaking in the region is now matched by the high quality of its wines. The Eastern Mediterranean is one of the fastest developing, most exciting and most dynamic wine regions in the wine world. A whole new world – in one of the oldest wine producing regions on earth!

The post Renaissance of the ancient world appeared first on OUPblog.

December 6, 2015

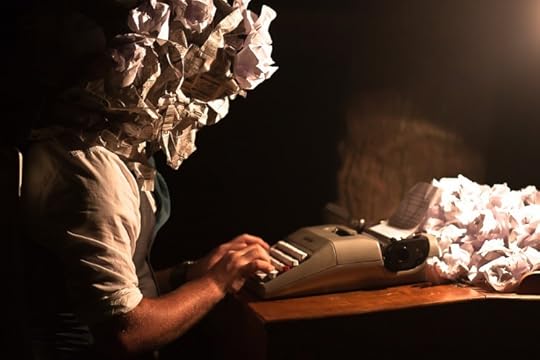

How to write a letter of recommendation

It’s that time of the year again. Seniors are thinking ahead about their impending futures (a job, grad school, the Peace Corps). Former students are advancing in their careers. Colleagues and co-workers are engaging in year-end reflection and considering new positions. People are applying for grants, scholarships, and fellowships.

That means letters of recommendation.

When a request comes out of the blue during a busy week, our first reaction is sometimes to shudder. “Yikes,” we think, “one more task to fit in on top of exams, papers, proposals, committee reports, and the usual slew of email.” Task saturation.

Sure, letters of recommendation are work, but it is writing that makes a difference in people’s lives. If you keep a few principles in mind as you approach your letters, writing recommendations can be rewarding and even enjoyable.

The letter is not about you.

If you’ve read Julie Schumacher’s epistolary novel Dear Committee Members, you know the comic effect that arises when a letter of recommendation is more about the writer than the subject. Most of us are not as clueless as her protagonist, but it is easy to slip into too much first person. Letters should focus on the recommendee and their accomplishments, strengths (and weaknesses), and potential. There’s a time and place for introducing your favorite subject, but not when you are writing a letter of recommendation.

So instead of writing this:

I first met so-and-so when she took my introduction to the English language course two years ago and I was so impressed with her research and writing ability that I encouraged her to enroll in my advanced grammar course, where I have students write an in-depth paper…

You might try this:

So-and-so came to our department two years ago and performed impressively in the introduction to the English language, where she wrote a fine short paper on gender and pronouns. Later in advanced grammar, she wrote an in-depth paper on adjective clauses in written English texts.

Oh, and don’t start the letter by saying your name. They’ll see that at the end.

Provide some evidence and detail.

Try to show as well as tell. It’s one thing to extoll someone’s abilities to communicate, research, or think, but it’s even better to be able to say how you know. Was there a standout effort or project? If so, what was unique about it? What was notable about the way that the person contributed to class discussions, organizational efforts or community? How did their efforts go beyond the norm? What are they best at?

“Writer’s Block I” by Drew Coffman. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Writer’s Block I” by Drew Coffman. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Remember to contextualize.

Reference forms often ask simplistic questions like: “Compared to all the candidates you have known, where do you rank this person?” Ugh. Who can say? And who keeps track of people that way?

For students, try to focus on them as real people, not as some percentage or even a grade point average. Are they juggling work, family, and school? Are they funny, thoughtful, diligent, well-prepared, diffident? Do they know what they want to do or are they experimenting (or even drifting)? Are they excited about school, learning, and their possible careers?

The same is true for colleagues. Try to put them and their work in. What are they involved in and committed to in your institution or community? Are they tapped for organizational priorities? Are they able to keep their balance while multitasking? Why are they ready for this new opportunity now?

Be honest but tactful.

The most important part of a reference rests in your ability to be honest about someone’s abilities and background. It’s a delicate task sometimes, but we do no one any favors if we gloss over weak points.

Honesty can be tricky in letters, since readers cannot see your face, they cannot ask follow up questions, and they may over-interpret remarks as more negative than they are meant to be. Are you damning with faint praise (“The student is a good writer” but not excellent) or sending a hidden message (“She often comes up with ideas that no one else considers” perhaps trivial ones or “He has a strong work ethic” but not much else). Be aware of what uncharitable readers might read into your letter.

One strategy that works for me is to link a weakness with a discussion of a complementary strength or other attributes. So, for example, you might find yourself explaining that someone is “intellectually ambitious though sometimes takes on topics that are hard to manage in just one semester” or that while a person is “somewhat quiet in class, her written work shows that she is engaged with the material.”

Another strategy is to point out to the recipient of the letter what is still needed to make someone flourish: “His skills have improved tremendously in a short time, and with further opportunities to develop them, he will be a solid researcher.”

Give your letter an ambiguity check.

I once told an excellent student who was prone to excessive wordplay that I would write in her letter of recommendation that “you’ll be very lucky if you can get her to work for you.” I was just kidding of course, though it’s always worth giving letters that final check not just for typos, autocorrects, and grammatical infelicities, but also for its potential for misreading. You never know what you might have said.

Think of recommendations as an opportunity.

I’ve come to appreciate the reflective aspect of writing letters of recommendation. In the day-to-day bustle of work, you may be too busy to think about all of your students and colleagues as people. Writing letters of recommendation is an opportunity to reflect on what people might be accomplishing in the future. It allows us not just to respond to tests, papers, and projects, but to a person’s aspirations.

So when you get that visit, call, or email asking you to write a recommendation whose work you value, don’t think “yikes.” Just say “yes.”

Image Credit: “Mystery Writers” by Nana B Agyei. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to write a letter of recommendation appeared first on OUPblog.

Fire and ashes: success and failure in politics

Politics is a worldly art. It is a profession that is founded on the ability to instill hope, convince doubters and unite the disunited – to find simple and pain free solutions to what are in fact complex and painful social challenges. In recent months a small seam of scholarship has emerged that explores public attitudes to politics and politicians through the lens of Daniel Kahneman’s work on behavioral economics and psychology. ‘Think fast’ and the public’s responses are generally aggressive, negative and hopeless; ‘think slow’ and the public’s responses are far more positive, understanding and hopeful. Such findings resonate with my own personal experience and particularly when I founded a “Be Kind to Politicians Party” as part of a project for the BBC and it was amazing how many people I was able to recruit in a fairly short time.

The aim of telling this tale is not to make the reader feel sorry for politicians, or really to defend them or their profession. The ‘aim’ – if there really is one – is to promote the public understanding of political life and to steer it away from over-simplistic representations of sleaze, scandal and self-interest. (P.J. O’Rourke’s Don’t Vote for the Bastards – It Just Encourages Them! suddenly springs to mind.)

Admitting to the pressures and dilemmas of political life is rarely something that a politician dares acknowledge while in office but political memoirs and autobiographies frequently admit to the anguish created by a role that is almost designed to ensure a decline in mental well-being. Job insecurity, living away from home, media intrusion, public animosity, low levels of control, high expectations, limited resources, inherently aggressive, high-blame, low-trust, etc….Why would anyone enter politics? Exploring the pressures placed on individuals as politicians – we often forget that politicians are individuals – is a topic that a small seam of scholarship has explored with Peter Riddell’s In Defense of Politicians (in spite of themselves) (2011) providing a good entry point to a more scholarly and complex field of writing where Gerry Stoker’s Why Politics Matters (2006) and David Runciman’s Political Hypocrisy (2010) form critical reference points.

But what has so far been lacking is a political memoir written by an academic that reflects solely on the paradoxes and dysfunctions of democratic politics. That is, until Michael Ignatieff penned Fire and Ashes (2013) as something of a cathartic process post-political recovery project.

Until 2006 Michael Ignatieff was a hugely successful and acclaimed academic, writer and broadcaster who had held senior positions at Cambridge, Oxford and Harvard. After 2006 he was an elected member of the Canadian House of Commons, and from 2009 Leader of the Liberal Party. Ignatieff was therefore an academic schooled in the insights of the political and social sciences who made the decision to move from theory to practice. “What drew me most was the chance to stop being a spectator,” Ignatieff writes, “I’d been in the stands all my life, watching the game. Now, I thought, it was time to step into the arena.”

Despite its title, the deeper insights of his book are less about success or failure, fire or ashes, but about the manner in which the demands of democratic politics appear to almost oblige individuals to adopt a certain way of being that grate against the ideals and principles that led them to enter politics in the first place. Put slightly differently, the political hypocrisy that is so often detected by the public, ridiculed by the media and even attacked by opposition politicians who are spared the dilemmas of power are arguably systemic in nature rather than representing the failing of specific individuals.

The reality of modern attack politics, of 24/7 media news, of the internet, of all those elements that come together to form ‘the system’ is that an individual’s freedom to actually speak openly and honestly is suffocated. The energy and life – possibly even the hubris – that propelled an individual to enter politics can be very rapidly destroyed by a systemic negativity and cynicism that means that spontaneity must be surrendered to a world of soundbites and media management.

But to end at this point – to blame elements of “the system” – in the hope of explaining the rise of anti-politics would be wrong. There remains a deeper tension at the heart of democratic politics that takes us right back to Bernard Crick’s classic Defense and a focus on the essence of compromise. Democratic politics is – when all is said and done – an institutional structure for achieving social compromise between contesting demands. And here lies both the rub and the real insight of Ignatieff’s experience: the worldly art of politics requires that politicians submit to compromises in a world in which compromise is too often associated with weakness and failure. Moreover, specific sections of society must be made to feel that they are special and that their demands are not being diluted when in fact they are due to the harsh realities of political life. To a certain extent, the hypocrisy, half-truths and fake smiles become essential due to the simple fact that no politician can please everybody all of the time. Democratic politics is a crucible for compromise.

But for the individual who enters politics with a very clear mission the need for compromise and conciliation – combined with an environment that is based on aggressive “fast thinking’ – can be soul destroying. “As you submit to the compromises demanded by public life, your public self begins to alter the person inside,” Igantieff notes, “Within a year of entering politics, I had the disorientated feeling of having been taken over by a doppelganger, a strange new persona I could hardly recognize when I looked at myself in the mirror…I had never been so well dressed in my life and had never felt so hollow.”

The “hollowing-out of the state” is a topic that has received a huge amount of academic attention, as is the “hollowing-out of democracy” but could it be that the “hollowing-out of politicians” demands at least a little consideration within debates about “why we hate politics”?

Igantieff is, however, nothing if not resolutely positive about the beauty of democratic politics and the capacity of politicians. His aim – like a lot of my writing – is not to put people off stepping into the arena but to help people enter the fray better prepared than he was. Better prepared in the sense of understanding the need to “play the game” in the sense of being worldly and sinful, while also remaining faithful and fearless at the same time.

Image credit: “Parliament Sunset” by Greg Knapp, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Fire and ashes: success and failure in politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Holograms and the technological sublime

The hologram is a spectacular invention of the modern era: an innocuous artefact that can miraculously generate three-dimensional imagery. Yet this modern experience has deep roots. Holograms are part of a long lineage: the ability to generate visual ‘shock and awe’ has, in fact, been an important feature of new optical technologies over the past century and a half.

From the 1850s until the First World War, generations of viewers immersed themselves in the depths of stereo views to explore exotic locales and unsettling scenes. The Victorian stereoscope created an insatiable public appetite for novel visual experiences. Its American populariser, Oliver Wendell Holmes, noted its “frightful amount of detail” that encouraged the mind to “feel its way into the very depths of the picture.” Dangerous perspectives and technological accidents became important sub-genres. Viewing the shocking visual aftermath of conflagrations, train wrecks, and typhoons proved popular, and battlefields held a vicarious fascination – akin, perhaps, to trending topics in social media today. Stereo views generated a burgeoning pastime and profitable trade around the world.

The flip side of these expanding markets was that the viewing public became increasingly keen for new visual surprises. This was an age of visual tricks, when ‘scientific optics’ could reveal disorienting new illusory effects; the creators and promoters of stereoscopes also introduced optical toys such as the kaleidoscope, zoetrope, and magic lantern. These devices dazzled the viewer with vivid mutating shapes, transient animated scenes or spectacular projections. These amusements combined surprise, spectacle and entertainment to extend the visual vocabulary of Victorian audiences.

Image credit: A view of the inside of the Magic Lantern by The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: A view of the inside of the Magic Lantern by The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.But the impacts of stereography and optical illusions were supplanted, in turn, by new technologies that gave imagery a new vibrancy and jolt of reality. Cinema extended the perceptions of audiences in its own ways. The Lumière brothers’ 1895 film of an approaching steam locomotive famously startled audiences, and editing tricks, colour imagery and wide-screen formats kept successive generations on the edges of their seats. Audiences after the Second World War were equally, if briefly, captivated by the spectacle of 3-D movies. Viewers of the 1952 adventure film Bwana Devil had close encounters with leaping lions and near-tactile romantic scenes. Within a year, over thirty 3-D movies, relying on more than a dozen commercial processes, appeared on cinema screens: House of Wax contrasted the thrill of a three-dimensional fight with a comically deep table tennis game, and Dial M for Murder had audiences avoiding a lunging hand.

So when holograms were first exhibited they joined a panoply of optical techniques that had successively shaken up new audiences. This reaction of disorientation, wonder and even fright – what historian David Nye dubbed ‘the technological sublime’ – has been a common experience in modern times.

The first three-dimensional holograms publicly exhibited in 1964 awed audiences with their baffling realism. Bathed in speckly-red laser light, these featureless glass plates acted like windows onto another world to reveal three-dimensional scenes that could be meters deep. Later varieties of hologram exhilarated fresh spectators by recreating full-colour and even animated views, extending the tradition of the zoetrope. The ethereal images could even straddle the surface of holograms, and yet evade the viewer’s touch. Holograms were later to be found popping out of magazines or shape-shifting on art gallery walls. For over two decades, waves of innovation in holograms startled audiences with fresh perceptual tricks.

Even so, hologram technology did not hold centre stage for long. For their first viewers, the wonders of holograms were shared with the equally remarkable optical properties of laser beams. And during the mid-Sixties, Op Art, reproduced via magazines, television, exhibitions and fashion, disconcerted wider audiences. But an even more democratic mass experience of the decade was the psychedelic light show. Strobe lights, enveloping screens and the abstract melting shapes of brilliant liquid dyes could reliably disorient and awe even jaded observers.

Yet surprise is evanescent. Each of these sensory shocks exhilarated and confounded new audiences but eventually became less compelling. Technological innovation and novelty seemed essential to reproduce the sublime experience, but the fleeting effect proved challenging to maintain. Physicist Stephen Benton, later a professor at MIT and a well-known figure in the field of holography, recalled how the head of Polaroid Corporation encouraged impressive ‘demos’ and perpetual surprises from his staff: “as long as – when you bumped into Edwin Land – you had something in your pocket he hadn’t seen before, that’s all it took!”

The same has been true for at least five generations of audiences. The history of optical technologies suggests that we crave fresh visual experiences, and that only a few of them have enduring impact. New ways of capturing that visual delight continue to exercise the minds of hologram innovators today.

Featured image credit: Op Art Bench (Part 3) by Scott Symonds. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Holograms and the technological sublime appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers