Oxford University Press's Blog, page 576

December 10, 2015

Welcome to Sital Niwas, Madame President

Nepal has had an extraordinarily eventful 2015. It has been rocked by catastrophic earthquakes and burdened by a blockade from India, but it has also (finally) passed a new constitution and elected its first female head of state, Bidya Devi Bhandari, who took office in October.

In electing Bhandari as the second president of the post-monarchy democratic period, Nepal joined its South Asian neighbor countries, most of which have or have had female heads of state or heads of government: Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka. Like most of the prominent political women who have led in these other contexts, Bhandari’s political career was early on tied to that of a man in her life – in her case, her husband Madan Bhandari, who was a prominent leader in the moderate communist Unified Marxist–Leninist (UML) party. Bidya Bhandari, however, was a powerful student leader for the UML prior to her marriage, and at the time of her husband’s death in 1993, was the chairperson of the women’s wing of the General Federation of Nepalese Trade Unions (GEFONT), meaning that her political career was far less derivative from his success than many other South Asian political women. After her husband’s death, Bhandari took over his parliamentary seat and rose to become a UML central committee member. She eventually became the UML’s vice-chairperson, and is a confidante of Nepal’s current Prime Minister, K.P. Sharma Oli.

In becoming president of Nepal, Bhandari is stepping into a still-evolving role – one which was only created in 2008 and which will be challenged in interesting ways by both her gender and the recent history of the practices she will be asked to perform. While the presidency is procedurally modeled on the British-style parliamentary system, the position in practice has taken over many of the duties – particularly religious duties – once performed by Nepal’s king. In addition to convening parliament, administering oaths of office to the cabinet, and accepting the credentials of new diplomats, the president is also expected to worship Krishna at a particular temple on Krishna Janmastami, receive a private blessing from the Living Goddess Kumari during Indra Jatra, and bless the leadership of the government during Dasai.

President’s building (Shital Niwas) by Krish Dulal. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

President’s building (Shital Niwas) by Krish Dulal. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The majority of the president’s explicitly religious (formerly royal) ritual responsibilities are Hindu, and that might theoretically constrain the identities of the people qualified to perform them. In Hindu contexts, people are not considered to be interchangeable: each person’s social identity (age, gender, caste, marital status, and family relationships) matter for the kinds of religious actions they are expected to perform (or not perform). Men do not have the same dharma (religious duties) as women; widowers do not have the same dharma as husbands; mothers do not have the same dharma as their daughters. Presumably, then, kings do not have the same dharma as presidents, even if an interim and then post-interim government insists on sending a non-king to perform a king’s ritual.

When Nepal made the transition from having a king perform its state-level public ritual to having the interim prime minister and then president perform its state-level public ritual, the change was real and revolutionary. In both the monarchy and post-monarchy periods, however, the core rituals of the Nepali state were performed by middle-aged to elderly high-caste Hindu males. There was no precedent for a president receiving a private blessing from the Living Goddess Kumari during Indra Jatra, but there was nothing in particular in the logic of Hindu ritual practice to prevent it.

When I was conducting my doctoral research between 2008 and 2011 on the transition away from monarchy, and the refiguring of state ritual as part of that transition, it was widely acknowledged that Nepal’s first president was an entirely appropriate candidate to perform all the rituals the king used to. But people from the government and religious leaders wondered, many times, what would happen in the future if the party-based electoral logic of the presidency started to conflict with the gendered, birth-based, familial logic of Hindu ritual. What if a future president was a woman? What if a future president was a low-caste dalit? What if a future president was a non-Hindu, especially a Muslim?

It is time now to find out the answer to the first hypothetical – and hopefully future presidents will continue to push the boundaries of who can represent the nation. For now, given a high-caste Hindu woman in office, the most likely ritual conundrum will likely concern menstrual purity. When Hindu women menstruate, they are barred from participating in rituals, and at 54 it is entirely possible that Bhandari has not yet entered menopause. What would happen if the president began to menstruate on the third day of Indra Jatra, or the seventh day of Dasai?

For conservative Hindus, this consideration might be enough to bar women from taking a ritually-laden leadership role in the first place, but the Nepali state has embraced a far more interesting and challenging approach to its presidency. Indeed, Bhandari’s main opponents in the election were both members of Nepal’s ethnic minorities, meaning that the presidency would have been pushed in new directions regardless of the outcome. What will be interesting to watch in the months and years to come will be whether presidential ritual performances are modified (perhaps even enhanced) around the identities of this and future presidents, and to continue to analyze what the shifting public performances of the state mean for imagining the Nepali nation.

Featured image credit: Nepal Himalayan Adventure 2012 by Ayesha Shafi from Frontierofficial. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Welcome to Sital Niwas, Madame President appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know Ezra Pound? [quiz]

Ezra Pound was a major figure in the early modernist movement. Born in America in 1885, he left his home country in 1908 and would spend much of his life in Europe. The years he spent in London are part of the emergence of modernist literature both in his own work and through his involvement with many of the writers, artists, and musicians of the early twentieth century. During his lifetime he developed close interactions with leading figures such as W. B. Yeats, Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, and T. S. Eliot. Yet his life was marked by controversy and tragedy, especially during his later years. A flawed idealist and a great poet, Ezra Pound was caught up in the turmoil of darkening times, and struggling, sometimes blindly and in error and self contradiction, to be a force for enlightenment.

How familiar are you with his work and personal life? Find out more and test your knowledge in the quiz below.

Featured image credit: Ezra Pound Blue Plaque, Kensington Church Walk – London by Jim Linwood. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post How well do you know Ezra Pound? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

100 years of Frank Sinatra [infographic]

On 12 December, we will celebrate what would have been Frank Sinatra’s 100th birthday. As his biography in Grove Music puts it, “In the course of his long career Sinatra’s name became virtually a byword for the American popular singer, and his singing represents a consummation of this longstanding tradition not likely to be equaled.”

And so, we wish you happy birthday, Frank.

Download the infographic in pdf or jpg.

Image Credit: Grace Kelly and Frank Sinatra on the set of High Society, 1956. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 100 years of Frank Sinatra [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

What are human rights?

On this anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it is worth reflecting on the nature of human rights and what functions they perform in moral, political and legal discourse and practice.

For moral theorists, the dominant approach to the normative foundations of international human rights conceives of human rights as moral entitlements that all human beings possess by virtue of our common humanity. What constitutes a human right, according to this approach, isn’t determined by a positive legal instrument or institution. Human rights are prior to and independent of positive international human rights law. Just because a legal order declares something to be a human right doesn’t make it so. Conversely, the fact that a human right doesn’t receive international legal protection doesn’t mean that it isn’t a human right. The existence or non-existence of a human right rests on abstract features of what it means to be human and the obligations to which these features give rise. The mission of the field is to secure international legal protection of universal features of what it means to be a human being.

On moral accounts such as these, human rights protect essential characteristics or features that all of us share despite the innumerable historical, geographical, cultural, communal, and other contingencies that shape our lives and our relations with others in unique ways. They give rise to specifiable duties that we all owe each other in ethical recognition of what it means to be human. Rights and obligations can also arise from the bonds of history, community, religion, culture, or nation. But if such rights relate simply to contingent features of human existence, they don’t constitute human rights and don’t merit a place on the international legal register. And if we owe each other duties for reasons other than our common humanity – say, because of friendship, kinship, or citizenship – then these duties don’t correspond to human rights and shouldn’t be identified as such by international legal instruments.

In recent years, political theorists have generated a distinctive account of the nature and role of human rights. Unlike most moral approaches, which focus on universal features of our common humanity, political conceptions define the nature of human rights in terms of their discursive function in global politics. Human rights, according to political conceptions, don’t necessarily correlate to the requirements of moral theory. Global human rights practice, for several political theorists, is a social practice whose participants invoke or rely on human rights as reasons for certain kinds of actions in certain circumstances. They represent reasons that social, political, and legal actors rely on in international arenas to advocate interfering in the internal affairs of a state and to provide assistance to states to promote their protection. What this practice reveals is that human rights protect urgent individual interests against certain predictable dangers associated with the exercise of sovereign power. States have a primary obligation to protect urgent interests of individuals over whom they exercise sovereign power, but external actors, such as other states and international institutions, have secondary obligations to secure protection when a state fails to live up to its responsibility.

Legal theorists of human rights, in contrast, typically start from the premise that international law, not moral theory or political practice, determines their existence. An international human right to food, for example, exists because the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights enshrines such a right. Its international legal status as a human right derives from the fact that international law, according to the principle pacta sunt servanda, provides that a treaty in force between two or more sovereign states is binding upon the parties to it and must be performed by them in good faith. Similarly, the right to development is a human right in international law because the UN General Assembly has declared its legal existence. The international legal validity of a norm – what makes it part of international law – rests on a relatively straightforward exercise in legal positivism; a norm possesses international legal validity if its enactment, promulgation, or specification is in accordance with more general rules that international law lays down for the creation of specific legal rights and obligations.

Determining the legal validity of an international human right is a relatively simple legal task. But legal validity doesn’t determine the normative purpose of a human right, and legal conceptions of human rights that seek to explain their purpose in terms that go beyond positivistic accounts of their legal production threaten to reintroduce moral and political considerations into the picture, which undermines the possibility that human rights can be understood in distinctly legal terms.

For example, human rights in international law are legal outcomes of deep political contestation over the international legal validity of the exercise of certain forms of power. Such contestation doesn’t cease upon the enactment of an international instrument that enshrines a human right in international law. Contestation continues over its nature and scope in particular contexts as diverse as individual or collective disputes requiring international legal resolution, opinions offered by international legal actors on state compliance with treaty obligations, juridical determinations of the boundaries between domestic and international legal spheres, and negotiations among state actors that yield binding or non-binding articulations of international legal obligations. Once transformed from political claim into legal right, and as subsequently as a result of interpretive acts that elaborate their nature and purpose, human rights in turn empower new political projects based on the rules they establish to govern the distribution and exercise of power. How to separate the legal dimensions of human rights from their political origins and outcomes is a challenge to those who seek to ascribe legitimacy to human rights in distinctively legal terms.

In my work, I seek to meet this challenge by defining the nature and purpose of human rights in terms of their capacity to promote a just international legal order. On this account, the mission of international human rights law is to mitigate the adverse effects of how international law deploys sovereignty as a legal entitlement to structure global political and economic realities into an international legal order. It contrasts this legal conception of international human rights with dominant moral conceptions that treat human rights as protecting universal features of what it means to be a human being. This account also takes issue with dominant political conceptions of international human rights, which focus on the function or role that human rights play in global political discourse. It demonstrates that human rights traditionally thought to lie at the margins of international human rights law – minority rights, indigenous rights, the right of self-determination, social rights, labour rights, and the right to development – are central to the normative architecture of the field.

Featured image: Mountains. Photo by Paul Earle. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post What are human rights? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 9, 2015

To whet your almost BLUNTED purpose…Part 1

Yes, you understood the title and identified its source correctly: this pseudo-Shakespearean post is meant to keep you interested in the blog “The Oxford Etymologist” and to offer some new ideas on the origin of the highlighted adjective. Blunt is of course a word of unknown origin, but in the bleak December, as well as in the blooming June, outside an introductory course to students, only obscure, even impenetrable words are worthy of discussion. The others are the stuff no one’s dreams are any longer made on.

In the OED, Murray gave a survey of the rather numerous dismissible conjectures on the etymology of blunt and left the question in limbo, where, to judge by the most authoritative recent sources, it still stays (even the otherwise courageous Henry Cecil Wyld refused to commit himself). I am aware of a single ingenious but unconvincing post-1884 hypothesis along the same lines and will later mention it. However, some progress in the discussion of the history of blunt has been made. Unfortunately (and here I’ll harp on a familiar note), our post-Skeat and post-OED English etymological dictionaries are mainly teamwork written in a hurry: their editors and contributors, with the partial exception of Weekley, had no knowledge of the countless suggestions on the origin of English words made in journals, reviews, and fugitive miscellanies. To my mind, a fairly convincing derivation of blunt was offered half a century ago, and in what follows I will give it full credit, but, regardless of that attempt to see light, a look at the old opinions about blunt will be instructive: among other things, it will show how researchers go in circles, unaware of or uninterested in the ideas of their fellow travelers.

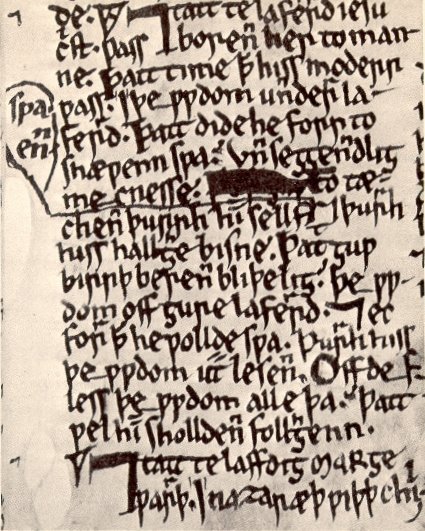

A page from the manuscript of the Middle English poem Ormulum (ca. 1200), in which the adjective blunt turned up for the first time.

A page from the manuscript of the Middle English poem Ormulum (ca. 1200), in which the adjective blunt turned up for the first time.Blunt first surfaced in Ormulum, a poem composed at the end of the twelfth century. This work (a long collection of versified homilies) is as dull from an artistic point of view as it is useful to language historians—mainly, but not exclusively, on account of its bizarre orthography. The poem’s author, a monk called Orm, spoke the Lincolnshire dialect. Lincolnshire, East Midlands, was part of the Danelaw, so that, not unexpectedly, the text is full of northern words, and for years etymologists have been trying to find the Scandinavian root of blunt. The few native (English) words that sound like blunt do not match its meaning. The French provenance of this adjective need not be considered, because the place name Bluntisaham, that is, a “hall” belonging to a man called Blunt, was known as early as 950, long before the Norman invasion of England. Bluntisaham also makes the Scandinavian provenance of blunt unlikely. The Century Dictionary recognized this fact and said that blunt was probably of English heritage, but the etymology it offered (a rehash of some old guesses) leaves one disappointed.

The situation is familiar: the recorded history of rather many English words begins with personal names. This is what happened to boy and bad (for bad, see a relatively recent series of posts). To put it differently: the adjective blunt existed as an independent word but did not make its way into books until 1200 (the Middle English period), while as a personal name it was attested long before that date. Such names (Bad, Blunt, and their likes) must have originated as nicknames. It should be remembered that medieval nicknames had an almost inconceivably offensive ring. The public reveled in every physical defect. References to ineptitude and mishaps, along with sexual innuendos, were flaunted like family heirlooms, but, strangely, they don’t seem to have aroused the targets’ wrath. Thus, someone was known as bad/Bad and his “neighbor” as blunt/Blunt, but what did blunt ~ Blunt mean? Obtuse, stupid?

Anyone can see why pint had a long vowel.

Anyone can see why pint had a long vowel.The OED groups the senses of blunt according to the known chronology: first, “dull, insensitive, stupid, obtuse,” then “of an angle, edge, or point ‘obtuse’; of a tool or weapon: ‘without edge or point.” “Dull, stupid, etc.” is the meaning found in the Ormulum; the first mention of “with a dull edge” surfaced only in 1398. But literal meanings, one should think, should precede the figurative, metaphorical ones: it seems that people began to speak about blunt knives and swords and only then, by association, about blunt (stupid) individuals. Therefore, the great Middle English Dictionary reversed the order and classified the senses according to logic, rather than dating: “dull, not sharp, without edge,” followed by “dull, stupid, obtuse, ?morally blind.” In addition to blunt, the Middle English spellings blont, blount, blond, and blund are given. They make the already puzzling situation even more so, but that is why the origin of blunt is “unknown.” Something, we assume, must be wrong with the large picture.

The list cited above (blont, blount, and blond, alongside blunt) is less innocent than it seems. In a way, the entire etymology of blunt depends on the final consonant. If it were d, it would be natural to try to connect blunt with blind and especially with blunder. Blunt people are apt to make blunders and sometimes forget themselves and behave, as though they were blind. The connections are far-fetched, but less probable semantic links have sometimes proved viable. We will see that numerous researchers tried to break open this door (blunt supposedly from blind and blunder). However, blunt clearly had final t. Besides, blount cannot be a continuation of blunt, because the diphthong in it (the sound we now spell as ou) can go back only to a long vowel, as in Modern Engl. too, boo, woo: thus, hus yielded house, nu became now, etc. Very early, short u was lengthened before nd but not before nt! Therefore, in the modern language, find does not rhyme with flint. The only word that has a diphthong before nt is pint, and that is why no genuine English noun, adjective, or verb rhymes with it. The history of pint reads like a thriller, but it should not concern us here.

This is an ounce, but not the one you expected. Not every ounce is small. Shelley, in Prometheus Unbound, spoke about hooded ounces pursuing hinds.

This is an ounce, but not the one you expected. Not every ounce is small. Shelley, in Prometheus Unbound, spoke about hooded ounces pursuing hinds.The family name Blount must once have had long u, as in count, mount, and their likes. All of them are of French origin. But there was no French blunt! It seems that late Middle Engl. blunt “lacking sharpness; stupid” was confused with blond “having fair hair,” though their meanings had nothing in common and though blond never had final -t. I have read the statement that the family name Blount meant both “blunt” and “blond.” This is a precarious formulation. How could such senses coexist in one word? To a non-specialist it may seem odd that a minor complication (the difference between final d and t) can derail a seemingly reasonable etymology. Alas! It can and should, because neither the Anglo-Saxons nor the French devoiced final b, d, g. Likewise, Modern Engl. robe, lend, and brig are distinct from rope, lent, and brick. In the science of etymology (sorry for the pompous phrase), half of the work depends on phonetics. God is not related to good, and Latin deus is not related to Greek théos (both mean “god”) only because their sounds do not match. If we disregard such niceties, we will end up in the Middle Ages, a period good to study, but not to live in.

So where do we begin the search for the “scientific” etymology of blunt? Wait for the answer until next week.

Image Credit: (1) “Lincolnshire” by Anonymous. Public Domain via Google Maps. (2) “A page from the Ormulum demonstrating the editing performed over time by Orm (Parkes 1983, pp. 115–16), as well as the insertions of new readings by “Hand B” by Geogre. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Beer” by StockSnap. Public Domain via Pixabay. (4) “A three-year-old jaguar kept at the Belize Zoo, west of Belize City, Belize” by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen. CC BY SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post To whet your almost BLUNTED purpose…Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Something of myself: the early life of Rudyard Kipling

“My first impression is of daybreak, light and colour and golden and purple fruits at the level of my shoulder.” With this beautiful sentence, so characteristic in its fusion of poetry and physical, bodily detail, Rudyard Kipling evokes the fruit-market in Bombay, the city (now Mumbai) where he was born in 1865. It comes from the first chapter of his posthumously published autobiography, Something of Myself (1937). As the title implies, Something of Myself is a partial offering, in some places inaccurate, in many devious. But its symbolic language doesn’t lie. Kipling would have been four or five at the time his Portuguese ayah and Hindu ‘bearer’ took him and his little sister Alice to the fruit market. The child lives in Paradise, marked not by the English language and English customs, but by the languages and customs of India in all their uncontrollable variety. (Kipling’s opening invocation in Something of Myself is to “Allah the Dispenser of Events.”) The child is open, curious, unconstrained. “Our ayah was a Portuguese Roman Catholic who would pray—I beside her—at a wayside Cross. Meeta, my Hindu bearer, would sometimes go into little Hindu temples where, being below the age of caste, I held his hand and looked at the dimly-seen, friendly Gods. . . . There were far-going Arab dhows on the pearly waters, and gaily dressed Parsees wading out to worship the sunset.” (The Parsee, “from whose hat the rays of the sun were reflected in more-than-oriental splendour,” will return in the Just-So Stories, scattering vengeful cake-crumbs in the Rhinoceros’s skin. Kipling forgot nothing.) By contrast the regimen of the Anglo-Indian family is stiff and formal. “In the afternoon heats before we took our sleep, she [the ayah] or Meeta would tell us stories and Indian nursery songs all unforgotten, and we were sent into the dining-room after we had been dressed, with the caution ‘Speak English now to Papa and Mamma.’ So one spoke ‘English,’ haltingly, translated out of the vernacular idiom that one thought and dreamed in.”

It doesn’t matter whether this ‘really happened’ or whether Kipling’s early childhood was “really like that.” Biography (which Kipling came to refer to as the “Higher Cannibalism”) has to take account of myth. Kipling is offering us this gift, giving himself away in the only way he knows, that of art. Paradise is light and colour, freedom from narrow-mindedness, and the stories and songs of India, “all unforgotten.” What followed? Exile in England: six years in the “House of Desolation,” the boarding-house in Southsea where his parents inexplicably abandoned him, at the age of five, with his three-year-old sister, for six long years. But that, as Kipling said in one of the most famous of his many catchphrases, is another story.

View of a temple from a window, a sight familiar to Kipling in his early years. Image by Paul McGowan, Public Domain via Pixabay.

View of a temple from a window, a sight familiar to Kipling in his early years. Image by Paul McGowan, Public Domain via Pixabay.Our evening walks were by the sea in the shadow of palm-groves which, I think, were called the Mahim Woods. When the wind blew the great nuts would tumble, and we fled–my ayah, and my sister in her perambulator–to the safety of the open. I have always felt the menacing darkness of tropical eventides, as I have loved the voices of night-winds through palm or banana leaves, and the song of the tree-frogs.

There were far-going Arab dhows on the pearly waters, and gaily dressed Parsees wading out to worship the sunset. Of their creed I knew nothing, nor did I know that near our little house on the Bombay Esplanade were the Towers of Silence, where their Dead are exposed to the waiting vultures on the rim of the towers, who scuffle and spread wings when they see the bearers of the Dead below. I did not understand my Mother’s distress when she found ‘a child’s hand’ in our garden, and said I was not to ask questions about it. I wanted to see that child’s hand. But my ayah told me.

In the afternoon heats before we took our sleep, she or Meeta would tell us stories and Indian nursery songs all unforgotten, and we were sent into the dining-room after we had been dressed, with the caution ‘Speak English now to Papa and Mamma.’ So one spoke ‘English,’ haltingly translated out of the vernacular idiom that one thought and dreamed in.

– Extracts from Something of Myself (1937)

Image Credit: Feature Image Taj Mahal, Creative Commons licence via Pixabay

The post Something of myself: the early life of Rudyard Kipling appeared first on OUPblog.

Birdwatching at the Federal Reserve

Seven years ago this month the federal funds rate—a key short-term interest rate set by the Federal Reserve—was lowered below 0.25%. It has remained there ever since.

Lowering the fed funds rate to rock-bottom levels did not come as a surprise. The sub-prime mortgage crisis led to a severe economic contraction, the Great Recession, and Federal Reserve policy makers used low interest rates—among other tools—in an effort to revive the economy. By the end of 2015, the US economy has rebounded. The unemployment rate, which topped out at 10 percent in October 2009, is now 5%. And GDP is growing at respectable, if not spectacular rates.

And so the big question facing the Federal Reserve is when to start raising interest rates. Those worried that the Fed’s low interest rates will soon generate inflation and a speculative boom argue for the gradual rise to begin sooner—perhaps as early as the Federal Reserve’s mid-December policy-making meeting. These are the inflation hawks. Those more concerned about the less-than-robust recovery of the economy argue for interest rate rises to be postponed into 2016. These are monetary policy doves.

Rather than discuss the merits of each of these arguments, I’d like to focus on the question of who will be making the decision.

The answer is not as simple as you might think.

The top policy making group at the Federal Reserve is the Board of Governors, a group of seven governors, appointed to 14-year terms by the president. Two of those governors are chosen to four year terms as chair (Janet Yellen) and vice chair (Stanley Fischer). Only five of the seven governors’ seats are filled at the moment; President Obama’s nominees for the two open seats have been in Senate confirmation limbo for eleven and five months respectively.

Fully staffed or not, the Board of Governors does not set the federal funds rate—that job belongs the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC consists of all the governors plus the presidents of five of the twelve regional Federal Reserve regional banks (Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Dallas, Kansas City, Minneapolis, New York, Philadelphia, Richmond, San Francisco, and St. Louis). The president of the New York bank is always on the committee; the presidents of Chicago and Cleveland serve every other year; the other nine presidents serve every third year.

OK, so now you have learned more than you ever wanted to know about the structure of the Federal Reserve System.

The big question facing the Federal Reserve is when to start raising interest rates.

But is it relevant to the future path of interest rates?

As of 1 January 2016, the voting membership of the FOMC will change. The governors and president of the New York Fed will remain on the FOMC, but the presidents of the Atlanta, Chicago, Richmond, and San Francisco banks will rotate off and be replaced by the presidents of the Boston, Cleveland, Kansas City, and St. Louis banks.

Will these personnel changes affect the likelihood that interest rates will start to rise sooner? They may.

Reuters, Bloomberg, and other news sources classify Fed governors and branch presidents as hawks or doves, depending on their attitudes toward inflation.

According to these ratings, the outgoing FOMC members include one hawk, Richmond’s Jeffrey Lacker, one dove, Chicago’s Charles Evans, and two neutrals, Atlanta’s Dennis Lockhart and San Francisco’s John Williams. The incoming members include three hawks, Cleveland’s Loretta Mester, St. Louis’s James Bullard, and Kansas City’s Esther George, and one dove, Boston’s Eric Rosengren.

These personnel changes suggests a slightly more hawkish FOMC in 2016, although the Reuters scorecard suggests that doves will remain in the majority. Further, these calculations omit the potential hawk-dove consequences of the confirmation of President Obama’s two nominees.

A more hawkish FOMC means greater Fed attention to the dangers of increased inflation and that, other things being equal, interest rate increases will become more likely after 1 January.

Whatever kind of bird you are, the Federal Reserve and, especially, the FOMC will be at the very center of economic news in 2016. Get out your binoculars!

Featured image credit: Modern-day meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee at the Eccles Building, Washington, D.C. by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Birdwatching at the Federal Reserve appeared first on OUPblog.

Human rights and security in US history

This Human Rights Day, commemorating the 10 December 1948 proclamation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, we embark on a year-long observance of the 50th anniversary of the two International Covenants on Human Rights: the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 16 December 1966. Together these documents form an International Bill of Human Rights, the birthright of all human beings with respect to civil, political, cultural, economic, and social rights.

The United States has drawn world focus on rights and freedoms – freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear – often in the context of preserving and promoting human rights through strong national and homeland security efforts, and requisite defense support to civil authorities, in the wake of natural and man-made disasters threatening each of those rights and freedoms.

Defense support of civil authorities must be considered in light of an evolution, rather than revolution, involving over a century of domestic federal troop deployments and 200-plus years of legal precedent, starting with the US Constitution, Article I, Section 8 as the basis for Federal government support, including Department of Defense assistance, to State and local authorities, as well as the 10th Amendment, inasmuch as “[t]he powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it, are reserved to the States respectively.”

The Insurrection Act of 1807 was one of the first and most important US laws still in force on this subject to limit executive authority to conduct military law enforcement on US soil, and was followed some 71 years later by the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878. Each of those and other civil support laws has evolved over time — consistent with the times and the popular will expressed through Congress.

Amongst the many lessons re-learned or real-world experiences validated, US interagency cooperation demonstrates that after state and local authorities had reached their capacity in dealing with previous disasters, additional federal authorities may have to assist local authorities with response to civil unrest and other challenges. Months after the disastrous effects of the October 2012 Superstorm Sandy, and weeks prior to the devastating 15 April 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, the Summer 2013 El Reno tornado in Oklahoma, and the wildfires in both Arizona and Colorado, the US Department of Defense (DOD) issued a DoD instruction and a strategy document clarifying the rules for the involvement of military forces in civilian law enforcement and DOD support to Federal, State, tribal, and local civilian law enforcement agencies, including responses to civil disturbances. This is especially important in the realm of so-called complex catastrophes that would overwhelm local and state agencies individually and require federal agency involvement with the DOD supporting an overall effort.

Thereafter, during the Spring of 2014, another series of domestic natural disasters included deadly severe storms severe storms, tornadoes and flooding; in the aftermath of destruction, National Guard members worked, “in coordinated efforts with civilian agencies … responding to communities in several states across the south.”

At least 62,000 unaccompanied children from Central America have come across the US-Mexico border from the Fall of 2013 up through the time of this writing; they were believed fleeing gang activity that could threaten to US national security. In defense support to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the unaccompanied children stopped by US Border Patrol are now being cared for by HHS’ Administration for Children and Families (ACF).

Aside from the aforementioned bases for support, Section 1208 of the 1990 National Defense Authorization Act (later titled Section 1033, which subsequently became Section 2576a), has allowed the Secretary of Defense to transfer to Federal and State agencies personal property of the DOD, including small arms and ammunition, suitable for use by such agencies in counter-drug activities and excess to DOD needs. Since its inception, the “1033 program” has transferred more than $5.1 billion worth of property. Critics of the program, such as the ACLU, claimed “a disturbing range of military gear [is] being transferred to civilian police departments nationwide.” This “1033 program,” coupled with National Guard deployment in Ferguson, MO, became the subject of critical media focus in the wake of police response to riots in August 2014 following the police shooting of crime suspect Mike Brown. Thereafter, President Obama issued the 16 January 2015 Executive Order 13688, which, along with the 18 May 2015 Law Enforcement Working Group Recommendations Pursuant to Executive Order 13688, directs executive departments and agencies to better coordinate their efforts to operate and oversee the provision of controlled equipment and funds for controlled equipment to law enforcement agencies.

The FBI has aptly observed that “[t]here’s no room for failure—when it comes to weapons of mass destruction, even a single incident could be catastrophic.” Former Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta warned the Nation in Fall 2012 of a potential coming “cyber Pearl Harbor; an attack that would cause physical destruction and the loss of life … [that] would paralyze and shock the nation and create a new, profound sense of vulnerability.” The policies and legal authorities governing Defense Support to Civil Authorities extend to cyber operations, as they would in any other domain. The Department of Defense works closely with its interagency partners, including the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security, to address threats to the United States from wherever they originate and to protect the rights of its citizens from foreign and domestic threats.

As George C. Marshall, the great soldier-statesman remarked in his 23 September 1948 speech to the United Nations General Assembly, “in the modern world the association of free men within a free state is based upon the obligation of citizens to respect the rights of their fellow citizens. And the association of free nations in a free world is based upon the obligation of all states to respect the rights of other nations.”

Image credit: Army Spc. Anthony Monte helps a woman displaced by Hurricane Sandy at an emergency shelter at the Werblin Recreation Center in Piscataway Township, N.J., Oct. 29, 2012. Monte is assigned to the 50th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, New Jersey Army National Guard. Department of Defense. Public domain.

The post Human rights and security in US history appeared first on OUPblog.

Ready for the winter holidays? [Quiz]

With the most widely-celebrated winter holidays quickly approaching, now is the time to test your knowledge of the cultural history and traditions that started these festivities. For example, what does Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer have to do with Father Christmas? What are the key principles honored by lighting Kwanzaa candles? What makes a dreidel spin? Find out the answers to these wintry mysteries and much more below! All quiz content from across Oxford’s online reference products has been made freely available for a short time.

Featured image credit: Depiction of the Menorah on the Arch of Titus in Rome, by Steerpike. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Quiz image credit: Northern lights in Ruka, Finland, by Timo Newton-Syms. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Ready for the winter holidays? [Quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

December 8, 2015

The politics of science funding

Government funding of science has become an increasingly prominent issue in the United States. Examining the current debate and its consequences, Social Forces Editor Arne L. Kalleberg interviews Gordon Gauchat about his recent article, “The Political Context of Science in the United States: Public Acceptance of Evidence-Based Policy and Science Funding.”

How might your study help us understand the current political debate in the United States over the science of climate change?

The results of the study ultimately show that the instrumental model of public perceptions has serious limitations. The instrumental model essentially claims that promoting science literacy and the dissemination of scientifically accurate information will convince the public about the seriousness of climate change. Not only does the instrumental model misunderstand the problem, I think a lot of scientists believe it to be true. Alternatively, this study suggests a more profound challenge for climate scientists and policymakers, because public apprehensions about science’s authority are associated with deeply held cultural dispositions and identities.

When we look at these results in conjunction with recent work on cultural cognition, not only are cultural dispositions—such as belief in religious authority or free markets—entrenched worldviews, but they also act as interpretive frameworks. In other words, people use these dispositions to access and understand new information, including scientific knowledge. So, appeals to science literacy and expert claims are unlikely to move those segments of the population that climate scientists and policymakers most need to sway.

What are the various positions taken by the current Presidential candidates about the utility of scientific inquiry and research funding? How does your study help to distinguish among these different positions?

Given the results of the study, Republicans and conservatives are more likely to evince skepticism about the role of scientific knowledge in government policy decisions. In fact, conservative Presidential candidates rarely invoke scientific expertise to make claims, because conservatives as a group increasingly appeal to alternative cognitive authorities—religious authorities (i.e., the bible, religious leaders) or economic markets and authorities (i.e., business leaders).

Interestingly, we can see the religious conservatism and laissez-faire conservatism (dispositions) play out in candidates’ views on science-related policies. For example, muted and oppositional views toward climate change indicate the laissez-faire disposition. Opposition to vaccine requirements similarly represents an anti-regulatory disposition. At the same time, some candidates have voiced skepticism about the age of the earth and biological evolution, which signifies religious conservatism. Overall, candidates have deployed some or all of these science issues to appeal to the different “cultural forces” within the party. I think the broader question for future research is why scientific authority has become a vehicle for indicating political identity. One possibility is that preferences for different cognitive authorities (i.e., religious, scientific, business leaders) may facilitate the construction of group boundaries and thus identity projects around being “conservative” or “liberal.” The different sources of cultural knowledge people recognize (or trust) thus becomes an important way to demarcate political identities.

What are the implications of your study for the future of government funding of science? In particular, how might your study help explain the debate over restrictions on the funding of political science research by the National Science Foundation?

Government funding for science is likely to be politicized moving forward because “opposition” to funding coheres on the political right. However, disciplines on the periphery of science in the public mind—political science, sociology, and even economics—are the most vulnerable to these challenges. That is, conservatives and liberals also have different views on what “counts” as science—with older male conservatives being especially critical of sociology. So, it is unclear that conservative political leaders would target “science” funding in totality, and instead might restrict funding to certain disciplines—those without the credibility and social esteem of physics, chemistry, or medical research. Removing programs from the National Science Foundation would be an effective way for conservatives to quickly relegate political science or sociology to a “less than scientific” status, a strategy that would simultaneously appeal to their base of support, alienate strong intellectual adversaries, but not greatly offend the public at large.

Government funding for science is likely to be politicized moving forward because “opposition” to funding coheres on the political right.

How can social scientists—and scientists in general—engage most effectively with the public and policymakers to inform policy?

I think this is the core question for social science in the United States. How do we effectively communicate to the public the importance of our research? First, I think we need to think about science and knowledge production in a more practical light, which can be difficult for scholars entrenched in abstract and specialized fields. We faced similar concerns about the relevance of social science in the early twentieth century, and the pragmatist John Dewey had some interesting answers back then. Overall, he suggested that science should produce and communicate sensible tools that people can use to better understand their social environment. I think this means that we need to think about the “tools” we are providing, and how to make those tools general enough to appeal to as many audiences as possible.

The concrete example for me is sociology’s capacity to provide a set of tools that overcome cognitive biases. For example, we often assume (for the sake of cognitive simplicity) that our current social institutions and norms have always been this way (are stable and natural). This bias might obscure the political struggles and social change that produced our social environment or novel potentialities for reforming it.

Overall, it might be effective for social science to explicitly offer practical tools for orienting social problems and overcoming common biases in perceiving social reality. Here, we do not belittle audiences by positing intellectual deficits or elite manipulation, but identity cognitive limitations common to all humans and how they might undermine our collective actions.

To what extent do you think the explosion of information available on the internet helped to undermine the authority of scientists and reliable scientific evidence?

I think social media and the proliferation of information does play a role. The proliferation of information has increased our exposure to “alternative” points of view, certainly. More importantly, I think technological change has greatly accelerated the sophistication and efficacy of identity projects in our society. That is, identity projects can now proliferate more information, and more importantly, offer analysis of the social world on multiple platforms and in many domains of our lives. At the same time, identities offer frames that help us interpret this glut of information. So, I think the information explosion makes preferences for cognitive authorities and social identities more important than ever, because these social phenomena facilitate the sorting of information.

Do we observe similar political and cultural polarization in attitudes toward science in other developed nations? If not, what might be the source of these divisions in the United States?

Unfortunately, the patterns for other developed nations are somewhat muddy and requires further research. Based on preliminary research I have done on this topic, the United States does appear to have stronger political and cultural divisions in perceptions of science. In fact, outside the United States, I observed more political tension with science on the left. However, the cultural sources of these divisions needs to be examined further.

Why do you think cultural and political ideas about science have begun to merge together?

As I mentioned above, I think identity projects in the United States, especially in the field of politics, are more effective at creating contrasts in multiple domains of social life than they were even 30 years ago, making group boundaries more palpable. There is certainly a lot of money dedicated to this activity and a lot at stake in the formation of political identities. Cultural dispositions about evidence-based policy and science funding are new ways for political groups and cultural dispositions to make distinctions. At the same time, the use of scientific expertise to legitimate government policy has become a key feature of the post-war political apparatus in the United States. So, while our political culture has become more sophisticated in using cultural tastes to contrast “us” from “them,” including trust in science and other authorities, the production of scientific knowledge has become a more prominent object in our social world—something that needs to be accounted for in our environment. This has fused together scientific knowledge, culture, and politics.

Image Credit: “Laboratory Scientists Research” by felixioncool. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The politics of science funding appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers