Oxford University Press's Blog, page 578

December 6, 2015

Shakespeare and Religion

We want to know what Shakespeare believed. It seems to us important to know. He is our most important writer, and we want to know him from the inside.

People regularly tell us that they do know what he believed, though mainly by showing what his father believed, or his contemporaries believed or, more accurately, what they said they believed—by demonstrating, that is, what was possible to believe. One can reconstruct the field of faith. One cannot say very much with confidence about Shakespeare’s own.

There is wonderful scholarship on what might be called religious thinking in Shakespeare’s England. Also on religious practices. Religion was undeniably the single most important aspect of early modern life. One might have said “single most important detachable aspect,” but it wasn’t detachable. It affected everything else. It shaped how everything was defined and understood. The Speaker of the House in 1601 addressed his colleagues: “If a questions should be asked, What is the first and chief thing in a commonwealth to be regarded? I should say, religion. If, What is the second? I should say, religion. If, What the third? I should still say religion.”

One measure of this would be that probably close to fifty percent of all books published in early modern England were overtly religious texts: Bibles, Books of Common Prayer, metrical Psalms, sermons, biblical commentary, biblical finding aids, religious history, religious controversy, handbooks for living and dying well; but this does not include the large range of books on seemingly secular subjects—cooking, husbandry, even grammar—which turn out to recommend forms of Christian conduct. Religion was everywhere. It saturated the culture—evident not least in the various thoughtless expressions, like “God b’ wi’ you” in leave-taking, which tell the story of the deep embeddedness of religion in the language itself.

Church of the Holy Trinity, Stratford-upon-Avon, England by Oosoom, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Church of the Holy Trinity, Stratford-upon-Avon, England by Oosoom, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsBut religion wasn’t just one thing. There was a Protestant Church of England, but England wasn’t a country only of Protestants—and Protestantism itself wasn’t single. Its very foundational principles exerted centrifugal pressures on the Church that threatened to, in John Taylor’s wonderful word, “Amsterdamnify” England, and to make, as John Donne said, “each man, his own priest.” And there were (a few) Jews, almost none living openly in their faith, and many more Catholics than for a while were acknowledged (and perhaps somewhat fewer than are often imagined by some today and somewhat more than are imagined by others).

In general, they lived in harmony, though not always, of course. Events sometimes made the government viciously sensitive to this lack of uniformity, usually when there was reason to fear an invasion from Spain with the accompanying worry that English Catholics might serve as a fifth column. In 1569 and 1570, in 1586, and again in 1588, in the late 1590s, and again in 1606. But in most times and in most places people lived together peaceably, linked by neighborliness and need, as well as by the recognition that everyone’s grandparents had been Catholics, so the hot rhetoric about the Catholic Antichrist was usually generic–and dampened when it led to thoughts that grandma might be burning in hell.

And it was a government that, however much it was officially Protestant, had on various grounds declined “to make windows into men’s hearts and secret thoughts.” It recognized that religion could be practiced in ways that were visible (and subject to surveillance if necessary), but faith was something private and inaccessible. This is not the imposition of a modern notion of interiority, but recognition of an early modern pragmatism, which recognized faith as a form of subjectivity into which neither Church nor Crown should peer, if indeed either could. Aesop’s story of Momus criticizing Jupiter’s creation of human beings was widely known: the creation of man was imperfect because the god, in Robert Greene’s phrase, had “framed not a window in his breast, through which to perceive his inward thoughts.”

The God of Genesis did no better on this score. “Inward thoughts” are still… well, inward, and the government wisely contented itself with trying only to enforce an outward conformity. So what do we know of Shakespeare’s inward thoughts?

Not very much is my answer, though that doesn’t make many people happy. What is undeniable is that he is extraordinarily sensitive to how much religion mattered in the world in which he lived. That sensitivity is registered in the plays and poems, as religious language, practices, and ideas shape characters and dramatic worlds. How religion mattered to Shakespeare, as a matter of belief and belonging, we don’t know. Nonetheless, “We ask and ask,” as Matthew Arnold said in his poem “Shakespeare,” but we receive no answer: “Thou smilest and art still.”

The post Shakespeare and Religion appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the Month: Baruch Spinoza

The OUP Philosophy team has selected Baruch Spinoza (24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) as their December Philosopher of the Month.

Born in Amsterdam, Spinoza has been called the “Prince of Philosophy” due to his revelatory work in ethics, epistemology, and other fields of philosophy. His works include The Principles of Cartesian Philosophy, Theologico-Political Treatise, and his magnum opus, Ethics.

Spinoza was of Sephardic Jewish descent – his ancestors fled from Portugal to Amsterdam during the Portuguese Inquisition – and he was given a traditional Jewish upbringing. Spinoza’s mother died when he was 6 and his father when he was 22. Spinoza spent his early years as a respected member of his synagogue, running the family business with his brother. However, he was issued a herem at age 23 from the Jewish community. It is not clear what the exact act or event was which caused his excommunication, but it most likely dealt with his radical views on religion and God.

A few years after the banishment, Spinoza left Amsterdam behind. He moved around the Netherlands and finally settled in The Hague. He spent the majority of his time as a private scholar and made a modest living as an optical lens grinder.

Spinoza died at the age of 44 in The Hague, Netherlands most likely due to a lung illness. Although he had a relatively short life, his impact on philosophy was extraordinary. Shortly after his death Opera Postuma was published by his friends, containing the Ethics, one of the major and most influential works of Western philosophy, the unfinished Tractatus Politicus, some lesser works, and some important correspondence. So notorious had Spinoza’s opinions become that they still only gave the name of the author as B. D. S.

His rationalist arguments have influenced leading philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein, Friedrich Nietzsche, Gottfried Leibniz, and many more to come.

Featured Image: Amsterdam skyline. Public domain from Pixabay.

The post Philosopher of the Month: Baruch Spinoza appeared first on OUPblog.

December 5, 2015

Seven important facts to know about climate change

Last week, the the 21st meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 21) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), began in Paris, France. Here, Joseph Romm, author of Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know, provides additional insight into our environmental state of affairs, and what it means for us and the future of humanity.

1. There’s a difference between “global warming” and “climate change.”

Global warming generally refers to the observed warming of the planet due to human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. Climate change generally refers to all of the various long-term changes in our climate, including sea level rise, extreme weather, and ocean acidification.

2. Intense snowstorms are more likely to happen during warmer-than-normal winters.

Global warming has been observed to make the most intense rainstorms more intense. A key reason is the extra water vapor in the atmosphere from warming. This means that when it is cold enough to snow, snow storms will be fueled by more water vapor and thus be more intense themselves. Therefore, we expect fewer snowstorms in regions close to the rain-snow line, such as the central United States, although the snowstorms that do occur in those areas are likely to be more intense. It also means we expect more intense snowstorms in generally cold regions.

3. Despite its phrasing, “global warming,” does not mean winters will cease to exist.

It is still going to be much, much colder on average in January than July. As for daily temperature fluctuations, they are so large at the local level that we will be seeing daily cold records—lowest daily minimum temperature and lowest daily maximum temperature—for a long, long time. That is why climatologists prefer to look at the statistical aggregation across the country over an extended period of time, because it gets us beyond the oft-repeated point that you cannot pin any one single, local temperature record on global warming.

Greenhouse Gases from Factory. Photo by Mohri UN-CECAR for Climate and Ecosystems Change Adaptation Research University Network. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Greenhouse Gases from Factory. Photo by Mohri UN-CECAR for Climate and Ecosystems Change Adaptation Research University Network. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.4. Decreasing the amount of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is not sufficient to stop global warming.

Although atmospheric concentrations (the total stock of CO2 already in the air) might be thought of as the water level in the bathtub, emissions (the yearly new flow into the air) are represented by the rate of water flowing into a bathtub from the faucet. There is also a bathtub drain, which is analogous to the so-called carbon “sinks” such as the oceans and the soils. The water level will not drop until the flow through the faucet is less than the flow through the drain.

Similarly, carbon dioxide levels will not stabilize until human-caused emissions are so low that the carbon sinks can essentially absorb them all. Under many scenarios, that requires more than an 80% drop in CO2 emissions.

5. Reducing or eliminating beef and dairy from your diet helps reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions.

If you have a diet rich in animal protein, then it is likely you can significantly reduce your greenhouse gas emissions by replacing some or all of that with plant-based food. That is particularly true if your diet is heavy in the most carbon intensive of the animal proteins, which includes lamb and beef but also dairy. Globally, the GHG emissions from producing beef is on average more than a hundred times greater than those of soy products per unit of protein.

6. Fossil fuel companies in the US have spent tens of millions of dollars to spread misinformation about climate science.

For more than 2 decades, the fossil fuel industry has been funding scientists, think tanks and others to deny and cast doubt on the scientific understanding of human-caused global warming. In the same way that the tobacco industry knew of the dangers of smoking and the addictive nature of nicotine for decades, but their CEOs and representatives publicly denied those facts, many of those denying the reality of human plus climate science have long known the actual science.

7. Despite our initial enthusiasm, we’ve discovered that corn ethanol generates just as much GHG emissions as the gasoline we use now.

For instance, research has found that corn ethanol from Iowa converts only 0.3% of incoming solar radiation into sugar and only some 0.15% into ethanol. In addition, transporting biomass long distances has a high monetary and energy cost. Finally, internal combustion engines are a very inefficient means of energy conversion. All that inefficiency and energy loss means that you need a huge amount of land to deliver low-carbon biofuels to the wheels of a car, especially compared with say solar and wind power used to charge an electric vehicle.

Image Credit: “Not only our island nation that is sinking” by Nattu. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Seven important facts to know about climate change appeared first on OUPblog.

The Hunger Games are playing on loop— And I am tired of watching

Say you wanted to take over the world—how would you do it? Let’s agree it looks much like the world we live in today, where some countries hold inordinate power over the lives of people in others; where global systematic racism, the shameful legacy of colonization and imperialism, has contrived to keep many humans poor and struggling. Now, let’s add climate change to that picture. How would you take over the world as landmasses slip underwater due to rising ocean levels, storms become more and more destructive, droughts decimate the agricultural stability of multiple countries (like in Syria, for example), and resources become more and more scarce?

The answer is so easy it is almost banal: control food supplies, of course. Hunger is a great way to control the masses, which is exactly what The Hunger Games illustrates.

In case you haven’t read The Hunger Games or seen the film, here is a brief synopsis: after climate change reduced the borders of the United States and many die, the country is divided into 13 districts and one powerful city, the Capitol, which is the seat of the government. Each district supplies food and resources to the Capitol; in return they are given “security” and barely enough food to keep them working. At some point in the novel’s imagined past, District Thirteen rebels, is bombed into oblivion, and in order to atone for Thirteen’s arrogance as well as ensure no other District will attempt the same, every year each district must supply two children for the Hunger Games, a grotesque gladiatorial spectacle where the children are forced to enact national policy—the fight and control over resources—until one “winner” remains. In Collins’ world as in ours, food is the key piece in an oppressive political game.

I am not the first writer to point out that food can be leveraged as a political weapon—Raj Patel, Susan George, and Vandana Shiva argue the same in great depth—and we can see this ideology enacted world-wide as powerful countries import food from others with starving populations. In fact, some countries like the United States have declared through legal maneuvers that food supplies (and, in turn, genetic food patents) are vital to national security. But since I live in a powerful country, the real-life version of Collins’ Capitol, a country that benefits from and controls global trade, why should I care?

Well, let’s say you are a person who can’t invest in the suffering of others. In The Hunger Games the residents of the Capitol are taught not to care about the lives of people in the Districts, to worry only about themselves. People suffering far away seem too remote, or maybe you are busy worrying about your own family, job, and survival to extend your concern to strangers. Compassion requires practice, and in today’s society we are rarely encouraged to express and practice such a radical anti-individualist and anti-capitalist emotion. So, too, the societal and environmental costs of our American lifestyles are often hidden from us, perhaps because if we witnessed and knew the full price of how we have been taught to live our lives we might demand other choices, choices that would not enrich so few while leaving others in devastated and polluted landscapes.

Collins’ book lays the global control of food resources bare for the very people who will inherit our political situation, also making us invest in her characters so we cannot look away, cannot afford not to care. In turn, we realize the Capitol is never satisfied, can never have enough capital. Exploitation benefits them… until it doesn’t. After all, capitalism, the endless accumulation of goods, has no end in sight. Barry Lopez writes about this very problem in The Rediscovery of North America when he notes that the ideology behind founding America, and indeed of global imperialism, was a “ruthless, angry search for wealth [. . .] in which an end to it had no meaning”. As in Collins’ book, power, money, food, and the basic needs for survival are being aggregated on the top of the economic chain, leaving everyone below to barter their lives—as the children of districts are forced to do—for survival.

The Hunger Games by Kendra Miller. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The Hunger Games by Kendra Miller. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.So here’s why you should care: right now you may live in a wealthy country, you may be able to drive to the grocery store to buy your next meal and maybe you will be able to do so for a long time yet. But climate change will threaten global food supplies, period. It will turn the entire world into a fight for food (and water), a global Hunger Games. Already we can see its effects on the weakest, the most marginalized—the exact situation Collins wants young adults to imagine and picture. I live in a powerful country but my family is not particularly wealthy, and it would be easy for them to become a few more of the many considered “disposable.” My community could be District Twelve, where Katniss is from (Appalachia, the unfortunate seat of Big Coal and devastated by mountaintop removal), though more likely, since I live in Iowa, it is District Eleven, the agricultural district. I care about the suffering of others but I am also motivated for personal reasons. I have a child and people I love, much like Katniss, and much like you. I can see the end game of the fight for resources in an overpopulated world teetering on either disaster or massive restructuring, and like so many others, scientists and humanists alike, I am afraid of what the future holds.

Collins’ imagined world may seem exaggerated, but she makes global politics visible for young and unsophisticated readers, so she strips our situation bare of its complexity, thereby making it visibly chilling in its clarity. I can’t help but think that as I write, the Hunger Games play on loop, maybe not here in my small sleepy town but elsewhere, places where people are forced to fight one another for resources to survive, and like many, I am tired of watching. It is not entertaining in the slightest, and also like many, I wish a single heroine would save us from ourselves. But as we see in The Hunger Games, it takes far more than one girl to change an entire social structure—it takes large groups of people brave enough to declare loudly that the global economic system is exploitative and needs to change, that we will no longer live by consuming the health of our planet or the lives of others. Like the characters in Collins’ novel, we can practice compassion, embrace the ethical imperative that the strong have a duty to protect the weak, and declare that true democracy—in which each voice matters in governance—is worth fighting for.

Finally, it may be strange to think that climate change offers us an opportunity, but it does. In The Hunger Games, climate change has already enacted its violence, but we stand on its precipice right now. For too long, we have known we need to change what it means to be human on planet Earth, how we live and consume, how we treat others, how we see ourselves in relation to the rest of the species on the planet. The changes required of us are tremendous and scary. We have been reluctant to tackle them but inaction is a luxury we can no longer afford. Climate change demands of us—not will demand, but demands of us right now—that we embrace global social equality and begin implementing large-scale social and environmental change. As I write this, world leaders are in the process of debating our ability to enact such change at COP21 in Paris. I hope they won’t let us down.

As I watched the last installment of The Hunger Games series just this past weekend, the final portion of Mockingjay, I was struck by the ending. I know critics will say it is too easy, clichéd in its happiness, heteronormative and unimaginative. I can agree with all of those things, but what I saw was a declaration of how we will sacrifice our very lives for common, simply human, desires: family, love, futurity, and peace.

I can’t imagine a more profound message to send to young adults as we teeter on the verge of global instability. If that is a cliché, it is a powerful one I would like to see realized in my lifetime.

Featured image credit: Kayford Mountaintop Removal Site by Kate Wellington. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Hunger Games are playing on loop— And I am tired of watching appeared first on OUPblog.

Could you be a Crime Scene Investigator? [quiz]

From Law and Order to True Detective, the role of the Crime Scene Investigator—at least, as portrayed on the screen—has captivated audiences around the world. Between what is dramatized and romanticized, however, it can be difficult to discern what solving crime actually entails, including the skills necessary to be an effective, knowledgeable practitioner. How much do you really know about crime scene investigation? Test your knowledge on everything from crime scene management to the recovery of evidence with our quiz, and don’t forget to tweet @bstonespolice to let us know how you did.

Get Started!

Your Score:

Your Ranking:

Image Credit: “Crime Scene” by Alan Cleaver. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Could you be a Crime Scene Investigator? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself”

In 1933 in the midst of Great Depression, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in his first inaugural address, wisely stated, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” That wisdom has as much relevance today as it did during the Depression.

After recent attacks in Lebanon, Paris, and Mali – as well as the bombing of a Russian airliner over Egypt – there is widespread fear, exacerbated by the 24/7 news media and by national leaders, other government officials, and political candidates who are heightening fear for political gain.

There are many fears: Fear of more terrorist attacks. Fear of migrants and other people who look different, speak an unfamiliar language, or who practice a different religion. Fear of participating in the daily activities of life – seeing a movie, attending a concert or sports event, eating at a café or restaurant, or even walking down the street. And ultimately, fear of fear itself.

To the extent that terrorists succeed in instilling fear – and others heighten fear – the terrorists achieve their major goal.

And the response to terrorism can, in some ways, be as harmful as terrorism itself: when societies respond with overwhelming military force against nations or people with no involvement in terrorism, as the United States and its allies did in Iraq; when societies undermine civil liberties and violate basic human rights; when intelligence or security operations resort to torture or other forms of cruelty, often against innocent civilians; when huge resources are diverted from human services to military purposes.

USUHS White Coat Ceremony, April 20, 2012 by MilitaryHealth. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

USUHS White Coat Ceremony, April 20, 2012 by MilitaryHealth. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.From a public health perspective, there are many actions that can be taken after a terrorist attack has occurred. These actions include responding to the personal and community mental health consequences of an attack; measures to better understand and address the roots of terrorism; improving community preparedness and response capabilities, enhancing the capability of the public health infrastructure to respond not only to terrorist attacks but also to a wide range of more-frequent natural and human-made disasters, epidemics, and other threats to the public’s health.

Physicians, in taking the Hippocratic Oath, commit to “do no harm.” As nations respond to these terrorist attacks, we, as physicians and other health professionals, need to insure that we do no harm in combating terrorism, and that we strengthen – rather than weaken – our principles.

We need a balanced approach to strengthening systems and protecting people – an approach that protects the public and also protects human rights, civil liberties, and the values upon which our society is based.

Featured image credit: Manifestation Charlie Hebdo by Pierre-Selim. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself” appeared first on OUPblog.

Shakespeare and Holinshed’s Chronicles

Where did Shakespeare obtain material for his English history plays? The obvious answer would be to say that he drew on the second edition of Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland (1587), a massive work numbering no fewer than 3,500,000 words that gave rise to more Renaissance plays than any other book, ancient or modern.

However, there are two problems with this answer. First, Shakespeare, a keen and voracious reader, always supplemented what he found in Holinshed with tidbits from other sources, among them poems, ballads, plays, popular pamphlets, and so on. Secondly, the Chronicles were themselves a mélange of earlier writings compiled at various times and by various hands, and as such very different from what we imagine a history book to be. Whereas we expect a reliable, coherent, and unbiased account of the past, the Chronicles were anything but. They told stories of giants and mythic rulers of Britain descended from ancient Trojans. Divided by religion and nationality, their authors included Protestants (both radical and conformist) and Catholics (both overt and covert); Englishmen, Scots and Irishmen. These men’s competing agendas reflected in a multiplicity of voices, styles, and viewpoints inevitably gave rise to tensions and contradictions. Think of the hysterically anti-Catholic passage describing in gory detail the execution of the so-called Babington plotters condemned in 1586 for conspiring to topple Queen Elizabeth in favour of the Catholic Mary Stuart. This passage was in fact censored by the government for fear it might alienate public opinion, something worth bearing mind when considering how Shakespeare’s King John treats the eponymous king’s conflict with the pope and his poisoning by a Catholic monk – events recounted with less anti-Catholic animus elsewhere in the Chronicles.

Moreover, conventions of history writing in Shakespeare’s time not only permitted but positively dictated that chroniclers invent speeches for major historical figures. Thus in the Chronicles we find Henry V’s rousing oration to his troops before the battle of Agincourt – “I would not wish a man more here than I have …” – which Shakespeare adapted in his Henry V. Nor was there anything odd about chronicles recycling other texts. For instance, the longest section of the Chronicles devoted to Elizabeth’s reign reprinted in full the text of an old pamphlet describing the queen’s procession through London on the eve of her coronation in January 1559, when she had been regaled with several colourful pageants or shows specially devised for the occasion. “Garnished with red roses and white,” the first pageant represented “The uniting of the two houses of Lancaster and York” in the persons of Elizabeth’s grandparents Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, as well as portraying her parents Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, and the queen herself. Clearly, Elizabeth was being urged to marry and secure the succession.

The Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland, Holinshed, 1587 – Title page, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland, Holinshed, 1587 – Title page, Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsShakespeare’s 1-3 Henry VI dramatized the Wars of the Roses, and his Richard III culminated with their auspicious resolution: “We will unite the white rose and the red, / Smile heaven upon this faire conjunction.” Leafing through the Chronicles in search of suitable material, therefore, Shakespeare would have come across not just the blow-by-blow narrative of fifteenth-century civil strife terminated by the union of Lancaster and York but also the description of the early Elizabethan pageant, so hopeful that the English royal line would endure. After the victory at Bosworth, Shakespeare’s Richmond (the future Henry VII) prays for his line’s continuance:

O now let Richmond and Elizabeth,

The true succeeders of each royal house,

By Gods fair ordinance conjoin together,

And let their heirs (God if thy will be so)

Enrich the time to come with smooth-faced peace…

To Richard III’s original audience these lines would have rung distinctly hollow, for Elizabeth had never married and the Tudor line was set to die with her. Then again, at least some spectators might have taken comfort in the fact that there was a direct descendant of “Richmond and Elizabeth,” their great-great grandson James VI of Scotland. However, Shakespeare was careful merely to hint at the sensitive issue of the succession without openly declaring his hand.

It was once assumed that Shakespeare improved on his shoddy, inchoate, and stylistically inferior chronicle sources or that he was a better historian than contemporary historians. We now know this is not quite true. Holinshed’s Chronicles were complex, multi-layered, and highly rhetorical. Besides, in acknowledging the diversity, uncertainty, and conflicting nature of the records on which they themselves drew, they compelled the reader to exercise critical judgment and remain on the alert to possible ulterior motives behind the conduct of monarchs, magnates, clerics, and parliaments.

Students of Shakespeare typically encounter only desiccated chunks of the Chronicles reproduced in modern editions of his plays. But why not see for yourself? The full text of Holinshed’s Chronicles can be accessed on the Holinshed Project website. At the click of the mouse, this electronic edition enables you to encounter first-hand the key source behind not just Shakespeare’s history plays but also two of his major tragedies, Macbeth and Lear, as well as the romantic Cymbeline. Sampling the richness and variety of Holinshed, you can begin to imagine how Shakespeare might have felt when he read it.

Featured image credit: Page banner illustration from page 3 of The Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland, Holinshed, 1587, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Shakespeare and Holinshed’s Chronicles appeared first on OUPblog.

APA Eastern 2016: a conference guide

The Oxford Philosophy team will be starting off the new year in Washington D.C.! We’re excited to see you at the upcoming 2016 American Philosophical Association Eastern Division Meeting. We have some suggestions for things to do and sights to see during your time in Washington, as well as our favorite sessions for the conference.

We recommend visiting the following sights and attractions while in Washington D.C.:

A short walk from the conference center is the renowned Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Prepare yourself before your visit by viewing their animal web cams and see what the pandas, Mei and Tai Shan, are up to!

Enjoy a stroll down Constitution Ave NW to see the Washington Monument, Lincoln Memorial, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the National Mall, and countless other historic sites.

You could also take a trip across the Potomac River to visit Arlington Cemetery, historic Alexandria, and George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

Tai Shan at the National Zoo, by dbking. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Tai Shan at the National Zoo, by dbking. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Situated between Northern and Southern states, Washington is home to an amazing assortment of restaurants and eateries. It’s easy to find great Southern foods such as fried chicken, barbecue, and grits. You can also visit the many New American cuisine restaurants to spot high profiled politicians. And, as it is home to a large immigrant population, you can easily find authentic Ethiopian, Chinese, Korean, Burmese, and Indian cuisines there too.

Keep an eye out for these conference sessions that we’re excited about:

Wednesday, 6 January, 12:30 to 2:30 pm sessions:

Author Meets Critic: Bonnie Mann, Sovereign Masculinity: Gender Lessons from the War on Terror

Wednesday, 6 January, 3 to 6 pm sessions:

Author Meets Critic: Herman Cappelen and Josh Dever, The Inessential Indexical

Thursday, 7 January, 2 to 5 pm sessions:

Symposium: The Philosophy of Romantic Love featuring Daniel Star, Carrie Jenkins, Berit Brogaard, and Michael Smith

Thursday, 7 January, 5 – 6 pm sessions:

APA Prize Reception, winners include Manuel Vargas, Alvin I. Goldman, Kate Manne, Diana Raffman, and many more.

Thursday, 7 January, 5:15 – 7:15 pm sessions:

Society of Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy (SPEP) featuring Edward S. Casey, Ladelle McWhorter, and Linda Martin Alcoff

Publishing Workshop featuring Hilary Gaskin, Sally Hoffmann, Gertrud Gruenkorn, Peter Laughlin, Peter Ohlin, Andy Beck, Andrew Weckenmann, Ties Nijssen, and Marissa Koors

Friday, 8 January, 9 – 11 am sessions:

Invited Paper: Realism and Idealism in Political Philosophy featuring Cynthia Stark, David Estlund, and Philip Pettit

Symposium: Kant’s Formulation of the Universal Law featuring Jennifer Uleman, Pauline Kleingeld, Robert Louden, and Julian Wuerth

Author Meets Critics: Daniel Star, Knowing Better

Friday, 8 January, 11:15 am to 1:15 pm sessions:

The Society of Philosophers in America presents The Obligations of Philosophers featuring George R. Lucas, Jackie Kegley, John Lachs, Bertha Manninen, and Andrea Houchard

Friday, 8 January, 1:30 to 4:30 pm sessions:

Symposium: The Function of Reasoning featuring Hilary Kornblith, Alison Gopnik, Pamela Hieronymi, and Hugo Mercier

Author Meets Critics: Michael Gill, Humean Moral Pluralism

APA Committee Session: The Procreative Asymmetry in Ethics and the Law featuring David T. Wasserman, David DeGrazia, Johann Frick, David Heyd, and Melinda A. Roberts

Friday, 8 January, 7 to 10 pm sessions:

Society of Christian Philosophers presents Contemporary Metaphysics featuring Laura Ekstrom, Trenton Merricks, Meghan Sullivan, and Aaron Griffith

Philosophy, Politics, and Economics Society presents Norms in the Wild featuring Geoff Sayre-McCord, Cristina Bicchieri, and Jerry Gaus

Saturday, 9 January, 9 – 11 am sessions:

Author Meets Critics: Stewart Shapiro, Varieties of Logic

Society of Applied Philosophy presents Parental Rights and Responsibilities featuring Jake Earl, S. Matthew Liao, Amy Mullin, Samantha Brennan, and Colin Macleod

Saturday, 9 January, 11:15 am to 1:15 pm sessions:

Symposium: Kantian Perspectives of Ethics featuring Alan H. Goldman, Grant Rozeboom, Norma Arpaly, and Serene Khader

APA Committee Session: LGBT Rights after Same-Sex Marriage featuring Christopher La Barbera, John Corvino, Esa Diaz-Leon, and Maren Behrenson

Saturday, 9 January, 1:30 – 4:30 pm sessions:

Symposium: The Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish featuring Hilary Kornblith, Karen Detlefsen, Eileen O’Neill, and David Cunning

Society for the Philosophic Study of the Contemporary Visual Arts presents Film and other Visual Arts featuring Christopher Grau, Lindsey Fiorelli, Daniel Dohrn, Morgan Rempel, and Gerad Gentry

Why not take time to visit the Oxford University Press Booth while you’re there? Browse new and featured books which will include an exclusive conference discount. Pick up complimentary copies of our philosophy journals which include Mind, Monist, Philosophical Quarterly, and more. Receive free access to our online resources including Oxford Handbooks Online, Very Short Introductions, Oxford Reference, and more. Enter our raffle for a chance to win some OUP books. And, of course, just stop by to say hi!

Featured image credit: Capitol Building in Washington DC at night. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post APA Eastern 2016: a conference guide appeared first on OUPblog.

December 4, 2015

Lessons for Volkswagen on organizational resilience

Volkswagen shocked the world. The world’s largest automaker admitted to creating software that would deliberately generate false exhaust emission information on many of its popular cars. Making matters worse, Volkswagen’s top leadership seemed unsure about how to respond to the crisis as it threatened the company’s reputation, operations, and long-term strategy.

The challenges faced by Volkswagen are repeated in organizations around the world. We have all seen the headlines: disruptive technology makes Kodak a relic, cyber hacking at Sony, miscalculated risk at AIG, and bad decision making at Lehman Brothers. What can organizations do to build resilience when faced with a devastating crisis?

Over the past 10 years I have worked with a team of researchers who have been studying organizational crisis like the one at Volkswagen. We reviewed product failures and operational crisis, as well decision-making blunders in business, government, the military, and politics. We paid special attention to how organizations learn from errors, failures, and setbacks.

Building resilience involves more than a single process, but requires attention to multiple activities. At Volkswagen, for example, learning might involve rethinking its leadership and operations, redirecting corporate strategy, and rebuilding its sagging reputation. Efforts to build resilience often focuses on four core areas:

Operational resilience occurs when an organization maintains its production and learns to operate even when experiencing catastrophic failure.

Strategic resilience happens when an organization adapts its strategy to changes in the environment, stakeholder interests, or emerging technology.

Managerial resilience surfaces from the know-how and decision-making skills of leaders.

Reputational resilience refers to an organization’s ability to learn from public failures or embarrassing revelations about the organization.

All four areas of resilience require learning, but effective learning across all four areas is difficult. Our research points to four lessons that Volkswagen can learn about resilience from the Texas City disaster, Lehman Brothers, and Air France.

First, resilient organizations build a system wide approach to learning. Every individual in the organization, from the frontline employees to the board of directors, needs to advocate for surfacing and responding to problems, errors, and risks. The BP Texas City oil refinery explosion provides a series of harsh lessons. An official investigation concluded that warning signs of operational failure had been present for years, but leadership failed to address these warning signs. Further, BP management touted low personal injury rates, but overlooked system wide safety issues. Years of budget cuts and lack of investment led the company to ignore important safety issues in favor of easy fixes.

Volkswagen should implement a new system of accountability from upper management to engineers, from the production line to dealerships. Whether it’s the strategic direction of the organization, improving new technologies, testing, or annual inspections, people should be judged not only on financial but educational results.

Second, resilient organizations remain open to bad news. In the case of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, leaders failed to accept the declining position of the company. Employees who brought bad news were treated as disloyal. In contrast, resilient leaders court bad news and opposing viewpoints because these counterintuitive ideas help uncover possible complications. Setbacks become minimized since the organization has already become aware of potential problems.

Volkswagen should create an independent reporting system for potential ethical concerns of employees so problems can be surfaced and addressed in a safe environment.

Third, resilient organizations know that most risks do not unfold without warning but follow predictable patterns. The causes for breakdown are often well documented within an industry or among an organization’s workforce. For example, in the Texas City disaster, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration found over 300 willful violations of safety rules, suggesting that leaders either ignored or were indifferent to significant safety concerns.

Volkswagen should appoint independent internal investigators to discover when and where concerns failed to be given appropriate attention. Staff and systems should be reconsidered in light of multiple failures.

Fourth, when an unfortunate breakdown emerges, organizations need to assure that they can return to normal operations quickly. In reviewing the Air France Flight 944 disaster and other airline accidents, we learned that a common response by pilots in the face of equipment failure is to focus on flying the plane. In other words, pilots often respond to a threat by returning to fundamental issues associated with flight. During the Air France breakdown, pilots became distracted by warning signals and computer reports that led them to overlook the fundamental issues involving generating lift and maintaining airspeed. In the case of organizational leaders, the fundamental issues might involve returning to normal operations, generating review, or regaining reputation.

Volkswagen should focus on their strengths from engineering to design and how to support those fundamentals with new information following their emission scandal.

Organizations like Volkswagen and others will continue to experience threats to resilience. Their ability to learn from other organizations that have experienced crisis will help them overcome organizational challenges that have become an expected part of working in complex world.

Featured image: Zagreb, Croatia – March 15, 2008: Chrome premium Volkswagen sign covered in mud and water after driving through muddy terrain. (c) tstajduhar via iStock.

The post Lessons for Volkswagen on organizational resilience appeared first on OUPblog.

Willem Kolff’s remarkable achievement

Willem Kolff is famously the man who first put the developing theory of therapeutic dialysis into successful practice in the most unlikely circumstances: Kampen, in the occupied Netherlands during World War II. Influenced by a patient he had seen die in 1938, and in a remote hospital to avoid Nazi sympathisers put in charge in Groningen, he undertook experiments with cellulose tubing and chemicals and then went straight on to make a machine to treat patients from 1943.

His first 15 patients died, but the 16th, a 67-year-old woman with acute renal failure caused by septicaemia, recovered after 11 hours of dialysis.

His rotating-drum kidney was a fearsome beast. Blood ran around cellulose (sausage skin) tubing, wound round a drum made of wooden slats, dipping into the ‘bath’ of dialysate at the bottom of its turn. The movement of blood was powered by the rotation of the drum rather than a blood pump. The surface area of the dialyzer was respectable by modern standards at over 2 m2, but it required up to two units of blood to prime the tubing before each dialysis, and ultrafiltration control was inaccurate and unreliable – achieved by adding variable amounts of glucose to the ‘bath’. Dialysate was made by stirring weighed salts into the tap water bath. A water pump from a model T Ford powered rotation.

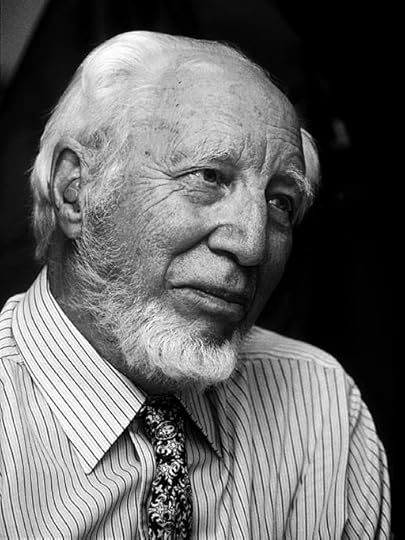

Willem Johan Kolff by KNAW (Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen). CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Willem Johan Kolff by KNAW (Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen). CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Kolff subsequently moved to the USA and went on to more remarkable things. His design was modified in Boston to make the Kolff-Brigham machine, which was widely used in the early 1950s and which, through its use in the Korean War, helped establish the role of dialysis in acute renal failure. The Watschinger-Kolff twin coil kidney introduced the concept of the disposable dialyser, enabled more controllable ultrafiltration, and the Travenol machine that used it became the most widely used machine in the early days of dialysis. Kolff went on to found the ‘Maytag’ programme of dialysis using a coil in a washing machine at the Cleveland Clinic, and to design artificial hearts and other bioengineering challenges.

His success with dialysis was dependent on the work of many who investigated its potential since Thomas Graham first described dialysis (and distinguished crystalloids and colloids) in 1861, and on technical developments, notably the development of cellulose tubing, and of heparin (instead of hirudin from leeches) as an anticoagulant. All of his practical experiments were on humans – he recounted that there was only his conscience as a brake. In the 1940s he investigated alternatives too, testing peritoneal dialysis (PD) and ‘intestinal dialysis’. Willem Kolff died in 2009 aged 97.

In the early 1960s, dialysis was still a very new technology. It was high-tech, life-saving and dramatic. That you can run the blood of conscious patients through a machine to replace a critical body function is still pretty amazing today. The idea of sending patients home to look after such a new, high-tech treatment themselves must have seemed extraordinary. But dialysis was very expensive, and soon, renal units were wrestling with how to stretch their resources to treat as many patients as possible.

Dialysis machines by Irvin calicut. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Dialysis machines by Irvin calicut. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.These pressures led to changes in renal units. Nurses took on tasks that were originally the responsibility of doctors, technicians shared work on the team, and even patients shared the work. Dialysis moved to become a nurse-led team treatment. Ann Eady recalls how the pressure of increasing numbers led to a transfer of the job of needling the fistula at Guy’s hospital. These radical changes in renal units probably had much further reaching consequences in medicine than we generally appreciate.

However, these changes were not enough. Staff salary costs kept dialysis expensive, and units became physically full. Patients were mostly young, and had to be capable of working to be accepted, but even then, there was not capacity to treat those who needed it. For those lucky enough to be accepted, combining dialysis with work and family life were as difficult as they are now. Transplantation was a high-risk gamble, and if it failed, one might not get back onto dialysis.

Haemodialysis carried out at home was introduced in three units thousands of miles apart in 1964, all responding to the same pressures. In Boston (Dr Merrill) in July, Seattle (Dr Scribner) in September, and in London (Dr Shaldon) in October, a patient received unattended overnight home dialysis for the first time. All used Scribner shunts, and some used machines made by patients’ families – some of the early patients were healthcare professionals, though the spread quickly widened. In the same year, Dr Boen reported visiting a patient at home in Seattle to carry out intermittent PD by repeated puncture, using a rigid catheter. It was, however, two more decades before peritoneal dialysis could become established as a realistic medium to long term home option.

HomeDialysisNxStage by BillpSea. CC BY 3.0 via Wikipedia.

HomeDialysisNxStage by BillpSea. CC BY 3.0 via Wikipedia.Some of the earliest UK home dialysis patients appear in the first episode of Tomorrow’s World, 45 years ago (7th July 1965), available on the BBC website, and filmed at the Royal Free Hospital’s unit. A remarkable Pathe newsreel the same year shows Olga Heppell dialysing at home in Harlow. Her machine was in part manufactured by her husband.

In the same year, Stanley Shaldon reported that transferring care to patients in the unit, primarily as a cost-saving measure, led to an increase in quality of care and patients’ independence. By 1968 he was writing about the additional benefits in independence and quality of life from home haemodialysis. Has this changed? Probably not.

Now home haemodialysis is on the rise again. The blogosphere is filled with enthusiastic accounts from patients doing daily dialysis at home, reporting much better health and quality of life. Machines are moving toward supporting home haemodialysis better. Achieving the same high treatment numbers again is made challenging by the different profile of patients today: older, with more comorbidities and greater dependencies. But it was always the best long term treatment if you couldn’t get a safe transplant, and it probably still is.

A version of this blog post first appeared in the History of Nephrology blog.

Featured image credit: Arm of patient receiving dialysis by Anna Frodesiak. CC0 Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Willem Kolff’s remarkable achievement appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers