Oxford University Press's Blog, page 575

December 12, 2015

Portraits of religion in Shakespeare’s time

Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries was marked by years of political and religious turmoil and change. From papal authority to royal supremacy, Reformation to Counter Reformation, and an endless series of persecutions followed by executions, England and its citizens endured division, freedom, and everything in between. And with such conflict among Christians, there was the perennial need to identify the “other.” Stereotypes of non-Christian groups surfaced in several media. Caricature-like depictions of Jews and Muslims became increasingly prominent among artists. William Shakespeare drew upon the religious unrest of this time period, and incorporated various religious indicators — from accurate portrayals to oversimplified ideas — into his plays, most notably Jewish stereotypes in his character Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. Peruse a slideshow of various works created during the most tumultuous period in English religious history to discover where Shakespeare, and other artists, could have learned these cultural markers.

St. Didacus in prayer

Created by 16th century Antwerp artist Marten de Vos, this painting features St. Didacus praying to an image of Mary and Jesus above an altar. Known as Didacus of Alcalá, a renowned missionary, St. Didacus was later canonized after the Protestant Reformation.

Image: “St. Didacus in prayer” by Maerten de Vos (1591-1600). Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

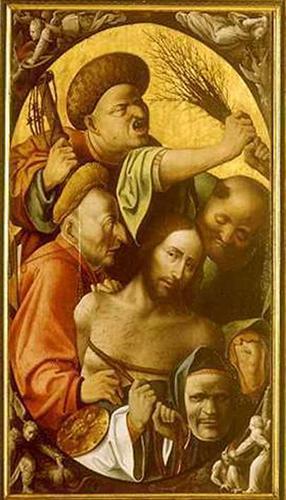

Passion of the Christ

This painting, by artist Hieronymus Bosch, not only illustrates the crucifixion of Jesus, but the common stereotype of Jewish facial features.

Image: “Passion of the Christ” by Hieronymus Bosch. (1515) Public Domain via Wiki Art

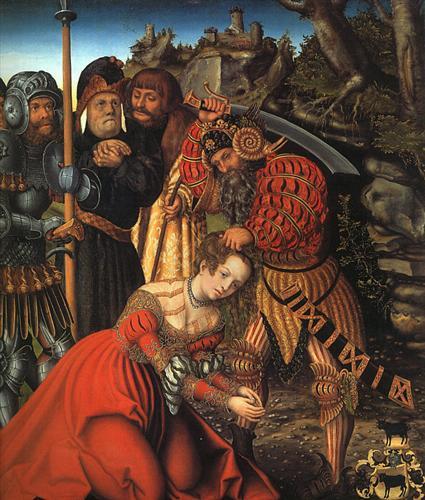

The Martyrdom of St. Barbara

In this painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Barbara is being executed by her father for converting to Christianity. Her father, a pagan, has stereotypical attributes, such as wielding a massive machete and brutally murdering his child.

Image: “The Martyrdom of St. Barbara” by Lucas Cranach the Elder (c 1510). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Public Domain via Wiki Art

Old St. Paul's Cathedral from the East

This engraving of St. Paul’s Cathedral of England was completed by Wenceslaus Hollar in 1652. It is argued that his engravings of Old St. Paul’s give a true general view of the church, although, because of his personal artistic flair, they are not entirely accurate.

Image: “Old St. Paul’s Cathedral from the East” by Wenceslaus Hollar (17th century). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Old St Paul’s (sermon at St Paul's Cross)

This oil painting, by John Gipkyn, was completed in 1616 and also depicts Old St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Similar to the previous artwork, Gipkyn does not remain faithful to the exact architecture of the building, but he does excellently represent the preeminence of the pulpit above the masses.

Image: “Old St Paul’s (sermon at St Paul’s Cross)” by John Gipkyn (161). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Lancelot Andrewes

Lancelot Andrewes was an Anglican bishop and scholar during the reign of Elizabeth I and James I. His influence in English politics and religious matters was great, particularly in his advancement of the career and popularity of John Calvin. The image above is an engraving of Andrewes from the frontispiece of a 17th century book of sermons.

Image: “Lancelot Andrewes” (17th century). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (uploader Dystopos).

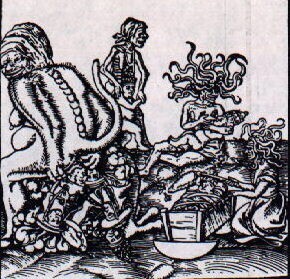

Birth and Origin of the Pope

This anti-pope propaganda was one of a set commissioned by Martin Luther for his work, “Against the Papacy at Rome, Founded by the Devil.” The caricature, illustrated by Lucas Cranach, depicts the Pope and Catholic cardinals coming into existence via the devil’s defecation.

Image: “Birth and Origin of the Pope” by Lucas Cranach (1545). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Cranmer's execution, John Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563)

Thomas Cranmer, a leader of the Protestant Reformation during King Henry VIII’s reign, was tried and executed as heretic during the reign of Henry’s daughter, Queen Mary I. He died a martyr for the Protestant faith and was immortalized in many religious texts.

Image: “Cranmer burning Foxe”. Ohio State University Libraries. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (uploaded by Bkwillwm).

Bury Witch Trial Report (1664)

This frontispiece of a 1664 witch trial report highlights a series of executions in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, England. One trial, lasting a single day, resulted in the execution of eighteen people.

Image: “Bury Witch Trial report 1664″ by Edmund Patrick. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

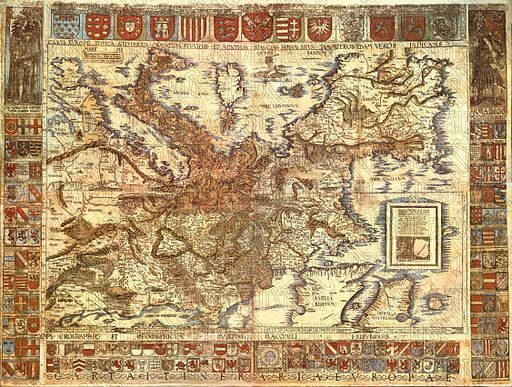

Map of Europe

Cartographer Martin Waldseemüller dedicated this map to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor of Spain. This map of Europe, though illustrated upside-down, clearly depicts Europe and highlights Italy, the epicenter of Roman Catholicism.

Image: “Carta itineraria europae 1520″ by Martin Waldseemüller. Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck, Austria. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Ingoldsby legends. Merchant of Venice/"'Old Clo'!" [graphic] / AR.

This drawing of Shylock from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice comes from a 19th century book of illustrations. It remains true to the stereotypical Jewish representations in art, overemphasizing Shylock’s hooked nose and frugal nature.

Image: “Ingoldsby legends. Merchant of Venice/”‘Old Clo’!” [graphic] / AR.” by Arthur Rackham (1898?). CC BY-SA 4.0 via Folger Shakespeare Library

[image error]

Iudaes. Der Jüd.

In this 1568 woodcut, Jost Amman remains true to Jewish stereotypes by depicting the men with long beards and hooked noses.

Image: “Iudaes. Der Jüd.” by Jost Amman. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The Entrance Hall of the Regensburg Synagogue

Albrecht Altdorfer created this etching of the Regensburg synagogue mere days before it was destroyed and the Jewish population was expelled from Regensburg. Altdorfer was actually one of the chosen few who commanded the Jews to empty the synagogue and leave the city.

Image: “The Entrance Hall of the Regensburg Synagogue” by Albrecht Altdorfer. OASC via

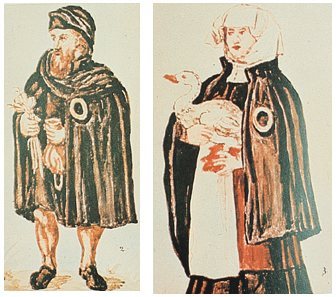

Jews from Worms

In this work by an unknown author, a couple from Worms, Germany wears obligatory yellow badges on their clothes. The man clutches a moneybag and bulbs of garlic, two icons use heavily in stereotypical representations of Jewish men.

Image: “Jews from Worms” by unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

A late voyage to Constantinople…

This illustration from a book published in 1683 documents a Londoner’s travel to Constantinople and other Islamic lands. Like many portrayals of non-Christian people, Muslims too were stereotyped and caricatured.

Image: “A late voyage to Constantinople…” by Guillaume-Joseph Grelot. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Folger Shakespeare Library

Ismāʻīl, the Persian Ambassador of Ṭahmāsp, King of Persia

Ismāʻīl was a son of Shah Ṭahmāsp and a diplomatic representative to the court of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman I. He became the shah of Iran around 1576. Captured here by artist Melchior Lorck, Ismāʻīl is given dramatic facial features and a largely exaggerated turban.

Image: “Ismāʻīl, the Persian Ambassador of Ṭahmāsp, King of Persia” by Melchior Lorck (1557-1562). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Unus Americanus ex Virginia, aetat. 23 [graphic] / W. Hollar ad viuum delin. et fecit.

This etching shows a Munsee-Delaware Algonquian-speaking warrior called Jaques who was transported to Amsterdam from New Amsterdam in 1644. More stereotypical characteristics persist in works created by Christians, typically of those they would often consider to be pagans.

Image: “Unus Americanus ex Virginia, aetat. 23 [graphic] / W. Hollar ad viuum delin. et fecit.” by Wenceslaus Hollar. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Folger Shakespeare Library

Indianen, Erhard Reuwich, 1486 - 1488

This print, made in the late 15th century by Erhard Reuwich, depicts two men talking to each other. The inscription is in both Dutch and Latin, and describes the man on the left in the robes of a cleric and the man on the right in the secular garb of a judge. Both are referred to as Indian, a term also used to mislabel Ethiopians.

Image: “Indianen, Erhard Reuwich, 1486 – 1488″ by Erhard Reuwich. Public Domain via Rijks Museum.

True religion explained, and defended against the archenemies thereof in these times. In six bookes. Written in Latine by Hugo Grotius, and now done in English for the common good.

As the title clearly states, this book was meant to explain the “true religion” and convert those who were Jewish, Muslim, or Pagan to Christianity. Upon close inspection, it is evident that the Christian is looking directly to the Heavens and is the only one receiving the light.

Image: “True religion explained, and defended against the archenemies thereof in these times. In six bookes. Written in Latine by Hugo Grotius, and now done in English for the common good.” by Hugo Grotius (1632). CC BY-SA 4.0 via Folger Shakespeare Library

Featured Image: “Life of Martin Luther” by Breul, H. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Portraits of religion in Shakespeare’s time appeared first on OUPblog.

Does moral obligation derive from God’s command?

‘Divine command theory’ is the theory that what makes something morally right is that God commands it, and what makes something morally wrong is that God forbids it. There are many objections to this theory. The four main ones are that it makes morality arbitrary, that it cannot work in a pluralistic society, that it makes morality infantile, and that it is viciously circular. This article is a reply to the fourth of these objections, that divine command theory is viciously circular.

The objection goes as follows. How do we know that we ought to obey God’s commands? And what do we do if the answer is that we ought to obey them because God tells us to? If we give some other reason, (perhaps ‘because of gratitude’ or ‘because God made us, and we belong to God’), then we still need to say why we ought to be grateful or why we ought to do what our owner says. Suppose we answer, ‘because God tells us to’. Then we will be stuck in the same circle. If we say, we just ought to be grateful, and to do what our owner says, and there is no more to be said, then we will be left with central moral obligations that are not made obligatory by God’s command. Divine command theory will in that way be shown to be false.

There is a response to this objection. We can say that we know the principle that if God exists, God is to be loved to be true ‘from its terms’. This is how Duns Scotus puts the point (Ordinatio IV, dist. 17). We know the principle to be true because we know that if God exists, God is supremely good, and what is supremely good is to be loved.

202/365 – Light of the World by Courtney Carmody, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

202/365 – Light of the World by Courtney Carmody, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.We also know, derivatively from this, that if God exists, God is to be obeyed. To love God is to seek to repeat in our wills God’s will for or willing. This is like loving other human beings, on Kant’s account of what he calls ‘practical love’, where we try to make the ends of those we love our own ends, if those ends are permitted by the moral law. We cannot, however, share all God’s ends in this way, because of the difference between us; we can share the ends that God has for our willing. But this is just to obey God. So we know that God is to be obeyed, derivatively from knowing that God is to be loved.

This means that we need to distinguish the unique obligation to do what God commands from all other specific obligations to do the things God commands us to do. The first of these can be shown to follow from the principle that God is to be loved, in the way just described. For all other moral obligations, their being obligatory derives from their being commanded. This shows, in the vocabulary of Duns Scotus, that the first is natural law strictly speaking, and the others are only natural law in an extended sense.

It does not follow from this that we can only know they are obligatory if we know they are commanded. A robust account of general revelation will hold that God reveals to human beings in general that certain things are obligatory and certain other things forbidden. But the people to whom this is revealed may not know that it is God who has revealed it to them. This is the beginning of a reply to the second objection to divine command theory, namely that it cannot work in a pluralist society. But that would be the subject for a different article.

The post Does moral obligation derive from God’s command? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 11, 2015

Saying goodbye to a great listener: a tribute to Cliff Kuhn, OHA Executive Director

Last month, the oral history world suffered a major loss with the passing of Oral History Association Executive Director Cliff Kuhn. His work touched all of us, and many people have written far more eloquently about his life and his passion than we ever could. Below we have gathered a few of these memorials, as a sort of meta-tribute to a great man, a great leader, and a great listener. To see and share more memories of Cliff, please visit the memorial page set up by the OHA. A memorial service will be held at Georgia State University this Sunday, 13 December.

“Cliff brought high energy, unfailing good humor and generosity, and a larger-than-life personality to everything he did, whether it was welcoming new oral historians to our organization, coaching his sons’ soccer teams, advocating for oral history in front of academic organizations and funding agencies, or making all of the communities he belonged to more democratic, egalitarian, and just. For all of these reasons we grieve with Cliff’s wife and family.”

—Staff, Oral History Association

“Cliff epitomized the ideal of the public historian. He valued shared inquiry for the purpose of deepening our collective understanding of the past. For Cliff, a multivocal, multivalent approach to historical understanding was not just one way to approach historical research, it was the only appropriate way to consider the past.”

—Adina Langer, Curator of the Museum of History and Holocaust Education, Kennesaw State University

“Cliff Kuhn’s many contributions have helped shape oral history work in the modern age. He will be missed, even as his legacy continues to impact the future of the field.”

—Jenna Mason, Office Manager, Southern Foodways Alliance

“Rest in power Cliff Kuhn: friend, mentor, oral historian, public historian par excelence.”

—Todd Moye, Professor of History, University of North Texas

“Anyone who knew Cliff understood what it was for a human being to be passionate about history. Cliff was no career climber, no indulger of superficial gestures or academic fads. He didn’t care about money or fame; as the great poet and essayist Wendell Berry once put it, there are “boomers” and “stickers” in life—and Cliff was definitely a sticker.”

—Alex Sayf Cummings, Assistant Professor, Georgia State University

“Cliff was an irreplaceable advocate for oral history and public history in the classroom, the academy, and the community.”

—Rachel Olsen, Administrative Support Associate, Southern Oral History Program

Atlanta’s WABE, where Cliff was a frequent contributor, featured this moving quote in which he explains his motivation for getting into oral history: “I was interested in putting people into the historic record who historically had not been included in, quote, ‘history’” said Kuhn. “I was interested in the democratic nature of oral history.”

Image Credit: “Headphones in Black and White” by Image Catalog. Public Domain via Flickr.

The post Saying goodbye to a great listener: a tribute to Cliff Kuhn, OHA Executive Director appeared first on OUPblog.

Most powerful lesson from Ebola: We do not learn our lessons

‘Ebola is a wake-up call.’

This is a common sentiment expressed by those who have reflected on the ongoing Ebola outbreak in West Africa. It is a reaction to the nearly 30,000 cases and over 11,000 deaths that have occurred since the first cases of the outbreak were reported in March 2014. Though, it is not simply a reaction to the sheer number of cases and deaths; it is an acknowledgement that an outbreak of this magnitude should have never occurred and that we as a global community remain ill-prepared to prevent and respond to deadly global infectious disease outbreaks.

The idea that this outbreak serves as a wake-up call is intended to provoke governments, global health leaders, researchers, and health care providers to identify the deficits in how the outbreak was managed. (Was the response too slow? Did governments or global health authorities fail to meet their obligations?) Ultimately, it is an acknowledgement, if not a pledge, that we must learn from this outbreak before we are faced with another. Yet, should we be persuaded that the Ebola outbreak will catalyze meaningful change?

‘It’s like déjà vu all over again.’ – Yogi Berra (attributed)

Unfortunately, this may be a more fitting sentiment. In the past 15 years alone, numerous infectious diseases have prompted similar ‘wake-up calls’ to improve global outbreak preparedness and response. These include outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS), H5N1, H7N9, and H1N1 influenza viruses, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-coV), and the emergence of pathogens with antimicrobial resistance, including multi-drug-resistant/extensively-drug-resistant tuberculosis. Perhaps even more to the point is that knowledge and isolated outbreaks of the Ebola virus since 1976 were not sufficient to ‘wake us’ in time to adequately prepare for the current outbreak.

The most important lesson we must learn from this Ebola outbreak regards our inability to learn lessons from past outbreaks. We have hit the snooze button repeatedly and ‘learn’ the lessons all over again when the next outbreak emerges. We either have collective amnesia or collective narcolepsy.

United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER)/Martine Perret. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

United Nations Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER)/Martine Perret. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.Perhaps, in our view, this is a moral lesson of a moral failing. Our failure to learn affirms a defect in our collective moral attitude toward remediating the conditions that precipitate the emergence of global outbreak threats. These conditions include profoundly inadequate public health and primary health care infrastructures in many countries and, more fundamentally, an inability to recognize and accept the responsibilities we share as a global community to address shared vulnerabilities. In practice, this translates into not only investing in global outbreak surveillance infrastructure, but also strengthening health systems in the worst-off countries. This latter crucial point has been acknowledged, but unfortunately has largely received only lip service.

Ultimately, learning this lesson necessitates engagement with the ethics of global outbreak preparedness and response. We must ask why there are repeated failures to implement the ethics guidance developed over the past few decades following outbreaks like SARS and H1N1 influenza. By failing to adequately engage communities in outbreak response, instituting travel bans and restrictions, and declining to share valuable data and tissue, this outbreak saw the adoption of policies and practices that fostered distrust and ran antithetical to the ethics lessons we have purportedly ‘learned’ from past outbreaks. It is as if past lessons have been wiped from our collective memory. Where these ethics learnings were implemented there was substantial progress; for example, burial practices that initially contributed to the spread of Ebola were successfully modified once communities were engaged, which helped to curb the spread of disease.

The fundamental manner in which we approach global outbreak preparedness and response must be seen not as merely technically deficient, but also morally deficient. Commitments to improving global outbreak surveillance and early outbreak warning systems (i.e., technical improvements) must be matched with commitments to cultivating the ethics lessons that emerge following outbreaks. If future actions are guided by the same values that have led to these repeated moral failures, we should doubt whether any meaningful change to global outbreak preparedness and response will occur. Substantial progress is therefore contingent on a reorientation of our moral attitude.

Without acknowledging the moral character of our failures and reorienting the paradigm of global outbreak preparedness and response to one that values global solidarity and justice, it is doubtful whether our repeated shortcomings will be corrected. We cannot entirely prevent infectious disease outbreaks from occurring; however, we can strive to ensure our moral failures are not repeated.

Featured image credit: Ebola Virus From Mali Blood Sample by NIAID. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Most powerful lesson from Ebola: We do not learn our lessons appeared first on OUPblog.

AAR/SBL 2015 annual meeting wrap-up

From 21 – 24 November, our religion and Bibles team was in Atlanta attending the joint American Academy of Religion / Society of Biblical Literature annual meeting. We had a great time interacting with customers and meeting authors. Here’s a slide show of some of the authors who stopped by the booth with their new books. Our conference discount is still good until 24 January 2016! Visit our webstore to browse our newest religion and theology books, and apply promotion code 33751 at checkout to received 20% off.

Andrea Jain

Andrea Jain, author of Selling Yoga: From Counterculture to Pop Culture, with an extra research assistant than last year

Anne Mocko

Anne Mocko with her newly published book, Demoting Vishnu: Ritual, Politics, and the Unraveling of Nepal’s Hindu Monarchy

Anthony M Petro

Anthony M. Petro, author of After the Wrath of God: AIDS, Sexuality, and American Religion

Daniel P. Scheid

Daniel P. Scheid, author of The Cosmic Common Good: Religious Grounds for Ecological Ethics

David M. DiValerio

David M. DiValerio with a copy of his book, The Holy Madmen of Tibet

David Lambert

David Lambert, author of the newly published How Repentance Became Biblical: Judaism, Christianity, and the Interpretation of Scripture

Debra Scoggins Ballentine

Debra Scoggins Ballentine with a copy of her book, The Conflict Myth and the Biblical Tradition

Dominic Erdozain

Dominic Erdozain, author of The Soul of Doubt: The Religious Roots of Unbelief from Luther to Marx

Forrest Clingerman

Forrest Clingerman, co-editor of Teaching Civic Engagement

Gary Slater

Gary Slater, author of C. S. Peirce & Nested Continua Model of Religious Interpretation

Geoffrey Redmond and Tze-Ki Hon

Geoffrey Redmond and Tze-Ki Hon, co-authors of Teaching the I Ching (Book of Changes)

Jonathan Kaplan

Jonathan Kaplan with a copy of his book, My Perfect One: Typology and Early Rabbinic Interpretation of Song of Songs

Joseph T. Reiff

Joseph T. Reiff, author of Born of Conviction: White Methodists and Mississippi’s Closed Society

Julie Ingersoll

Julie Ingersoll, author of Building God’s Kingdom: Inside the World of Christian Reconstruction

Leslie Dorrough Smith

Leslie Dorrough Smith with a copy of her book, Righteous Rhetoric: Sex, Speech, and the Politics of Concerned Women for America

Anthony O'Hear and Natasha O'Hear

Anthony O’Hear and Natasha O’Hear, co-authors of Picturing the Apocalypse: The Book of Revelation in the Arts over Two Millennia

Reid L. Neilson

Reid L. Neilson, co-editor of From the Outside Looking In: Essays on Mormon History, Theology, and Culture

Sara Moslener

Sara Moslener holding a copy of her book, Virgin Nation: Sexual Purity and American Adolescence

Scott Fitzgerald Johnson

Scott Fitzgerald Johnson, author of Literary Territories: Cartographical Thinking in Late Antiquity

Sheridan Hough

Sheridan Hough, author of Kierkegaard’s Dancing Tax Collector: Faith, Finitude, and Silence

Timothy Dobe

Timothy Dobe holding a copy of his book, Hindu Christian Faqir: Modern Monks, Global Christianity, and Indian Sainthood

The post AAR/SBL 2015 annual meeting wrap-up appeared first on OUPblog.

The freewheeling Percy Shelley

In the week I first read the Poetical Essay on the Existing State of Things — the long lost poem of Percy Bysshe Shelley — the tune on loop in my head was that of a less distant protest song, Masters of War. In 1963, unable to bear the escalating loss of American youth in Vietnam, the 22-year-old Bob Dylan sang out against those faceless profiteers of war:

“I hope that you die and your death will come soon,

I’ll follow your casket on a pale afternoon…”

In 1811, when the impact of war abroad had become as unbearably visible as it had for Dylan, Shelley too was driven to wish death upon those murderous men behind desks: “May that destruction, which ’tis thine to spread, / Descend with ten-fold fury on thy head.” By writing as much Shelley ran the very real risk of imprisonment for seditious libel. Just one copy of the pamphlet — smuggled to a cousin named Pilfold Medwin — survived the fiery purge, and that is the one which cropped up in 2006 and is now available online through Oxford’s Bodleian Library.

While Dylan identified with the apparently classless American youth, for Shelley the pawns in the rich men’s game were explicitly the poor, working-class fodder of Georgian warfare. He shows an uncommon sympathy too for the non-British war dead, including the blameless victims of the equally blameless frontline agents of colonialism. While being careful to distance himself from the recently vilified Bonaparte (just another Master of War in his poem), Shelley is — at the tender age of 18 — already the fully fledged radical and reformist poet who in 1819 would exhort British workers to “shake your chains to earth like dew”, remembering that “Ye are many — they are few.”

Unlike Dylan’s ultimately downbeat song, Shelley closes his passionate poetical essay on a hopeful note: “Peace, love, and concord, once shall rule again, / And heal the anguish of a suffering world.” This was the central message of the so-called Cockney school, with which Shelley and other Left-leaning metropolitans (think Leigh Hunt and John Keats) would be associated towards the end of the decade.

Image credit: Percy Bysshe Shelley, by Alfred Clint, 1819. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Percy Bysshe Shelley, by Alfred Clint, 1819. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Above Shelley’s preface he printed the words: “Nunquam ne reponam vexatus totiens?” — “Am I never to retaliate, [even when] repeatedly enraged?” In Juvenal’s first Satire, the quote’s origin, the frustrated Roman poet can hold his famously sharp tongue no more — not because of any social injustice, or the ravages of war — but because he has had quite enough of the windbag poet Cordus reading from his interminable epic poem about Theseus. Shelley’s Latin epigraph might at first glance seem to import little from Juvenal’s poem other than the sheer exasperation expressed, but it also importantly aligns the two poets in a common distaste for the tradition of singing songs about the bloody exploits of great men, or the “noxious race of heroes” as Shelley would call it in a letter to William Godwin the following summer.

In spite of such apparent anti-classicism, the late 1810s and early 1820s saw Shelley and his fellow cockneys produce dozens of classically inspired poems, all concerned — like the Poetical Essay — with post-revolutionary social reform. They consistently posed, if not always answered, the question: How can we hope for a better world in the war-torn ruins of a failed revolution? The cockneys were convinced that poetry had the potential to affect social and political change. Perhaps surprisingly, the poetry they turned to for this was frequently that which drew upon the Greek and Roman classics. Cockney classicism showed a completely different side of the classical world to that used in the traditional educational system, and (less surprisingly) the establishment hated it. A Tory critic wrote that “a Hottentot in top boots is not more ridiculous than a classical cockney.”

Their alternative classics had nothing to do with the rote learning of Latin grammar, rhetorical commonplaces, austere Roman stoicism, or heroic deeds; they wanted to build and explore an unapologetically pagan and openly erotic poetic landscape imbued with the radical and democratic ‘spirit of Greece.’ They used the classics in glorious Technicolor to combat the post-revolutionary introversion of mainstream contemporary poetry and the monochromatic despondency of the period.

In a cluster of bright allegorical poems written around 1818, the cockney poets provoked the establishment with hopeful songs for social reform, mostly wrapped up as love stories between mortals and divinities. Since the poets were considerably more familiar with Latin than they were with Greek, at the heart of this poetic universe of countercultural Hellenism we find traces of a certain Hellenizing Late Republican Roman poet. Catullus had been fully translated into English for the first time only in 1795, and his Greek-style, countercultural poetic made quite an impression on the cockneys.

The part of his work that they drew on most consistently was poem 64, in which Ariadne, stranded by Theseus on the isle of Naxos, is eventually rescued by Bacchus in his aerial chariot. The wine god’s motley crew flies noisily through several cockney classical poems, and his arrival — complete with cymbals, horns, Maenads and the severed limbs of beasts — is an emblem of hope in a world of despair. Bacchus swoops in, ever the harbinger of “Peace, love and concord.” And it is this determined presence of hope that distinguishes many of the political poems of the cockneys from the humble protest song. May our present and future “legislators of the world” take note: Shelley and his fellow patriots dared to do more than simply protest; they built their own utopian ‘Land of Cokaygne’ in the shared imaginative universe of their poems.

Headline image credit: Blake sculpsit © Henry Stead. Used with permission.

The post The freewheeling Percy Shelley appeared first on OUPblog.

Hip Hop therapy: the primacy of reflexivity and cultural dialogue

The rise of Hip Hop as a medium for health, activism, and spirituality within various therapeutic disciplines signals the obvious: Hip Hop is not mere entertainment or a specific genre of music geared towards one particular demographic. As KRS-One notes, “…Hip Hop has always existed as a unique awareness that enhances ones ability to self-create.” In essence, self-discovery and transformation are at the core of creative expression in Hip Hop.

Working as a music therapist over the past 15 years in Washington DC, Chicago, and Philadelphia with adolescents who had experienced trauma and adversity, rap and Hip Hop has played a pivotal role in my work. Though this might be an obvious statement to someone indigenous to the culture, I have had to learn that Hip Hop was more than just a genre of music but an expression rooted in cultural intricacies. Stepping into the culture as a therapist—a white male from a middle-class suburban background—I have taken the stance of a learner. I am a student of Hip Hop; the people I have worked with who are native to its culture have been my teachers, as have been the artists and pioneers whose art I have immersed myself in and studied. My lessons in Hip Hop have helped me become more culturally self-aware of how my privilege impacts decision-making and relationship in therapy, develop empathy for the lived experience of the communities I have worked with, and be more authentic and present as a therapist.

There have been many moments where the people I have worked with have shifted my consciousness about Hip Hop, culture, and healing. One moment that stands out was when I was working with a group of adolescents at an after school community center in Northern Philadelphia, conducting a therapeutic songwriting group called Hear Our Voices, an initiative of the Arts and Quality of Life Research Center at Temple University. During one of our dynamic recording sessions, one of the participants wanted to listen to an up-and-coming street rapper from Philadelphia, Meek Mills. I was intrigued by what they felt made Meek Mills unique and one participant responded, “his flow is the fire of someone wanting to get out of poverty, something we can all relate to.” This comment deepened my listening, and perhaps sensing my authentic interest, the group introduced me to a video showcasing what they felt was the epitome of Philadelphia battle rap: Reed Dollarz, local favorite, versus Trigga, a seasoned veteran from outside of Philadelphia.

I watched the video with the adult staff and teenagers in the room. Initially, I focused only on the aggressive verbal and physical gestures in the video, and felt uncomfortable. I allowed myself to be aware of these feelings, recognized them as the roots of my own cultural messages and biases, and then shifted my consciousness to how others in the room where perceiving the video. The adults and teenagers in the room were more concentrated on the rules of engagement, game play, and artistic interplay involved in the competition. The adults listening with us took the lead in providing teaching moments not only for me but for the teenagers in the room as well, revealing the intricacies of the techniques involved in the battle.

Reed Dollarz begins the competition; he is affective and in control of his talent. Reed purposefully ignores, but is highly aware of Trigga, each move calculated for impact and effect. For example, at 2:03, Reed finally faces Trigga and finishes his verse by enunciating the words “pots and pans.” A defining moment occurs at 4:18 when Reed Dollarz takes advantage of Trigga, who momentarily leans sideways, by whispering in his ear. Although the battle is only halfway done, one of the participants I was watching the video with shouted, “That is the moment; its OVER!” By being an open learner and reflexive of my own biases, I was able to stand in authentic awe of the prowess, technique, agility, nimbleness, creativity, and intuition that went into this battle.

In my initial listening experience and with each subsequent listen, I tend to cycle through some of these dichotomous reactions: I am offended; I am a voyeur; I don’t belong; I am disconnected; I see two highly skilled competitors; I see expertise; I see a community gathered for a shared music experience; I am moved by the prowess and raw emotion involved; I feel connected; there is a shared humanity; I belong and yet I am separate. I feel that all of these responses represent partial truths towards a more holistic understanding of the complexities of creative processes when producing Hip Hop in therapy.

In 1982, Albert LeBlanc proposed a theory of listening using the metaphor of a gate to explain how ones how music preference is created. The gate metaphor suggests our cultural and historical background, as well as our personal narratives determine when we open ourselves up to what a piece of music has to offer and when we shut it down. The process of my gate opening to rap and Hip Hop has been a personal and shared journey that continues to unfold. There are many rewards that can be garnered through sharing our cultural reflexivity, honoring the voices of the people we serve, involving ourselves in honest and open cultural dialogue, and delving into uncomfortable topics involving race, class, power, and privilege. Hip Hop provides a funky interstellar vessel within which discourse can unfold. As a healthcare provider who utilizes the creative forces of Hip Hop as therapy, I feel the weight and responsibility of this task.

Image Credit: “Graffiti” by William Warby. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Hip Hop therapy: the primacy of reflexivity and cultural dialogue appeared first on OUPblog.

Do mountains matter?

Do mountains matter? Today, 11 December, is International Mountain Day, celebrated worldwide since 2003. The fact that the UN General Assembly has designated such a day would suggest a simple answer. Yes – and particularly for the 915 million people who live in the mountain areas that cover 22 percent of the land area of our planet. These are the latest figures, published recently by the FAO and available soon on the website of the Mountain Partnership.

Mountains are clearly vital for those who gain their livelihoods from them; but in what ways are they important for the rest of us? From a global perspective, perhaps their greatest value is as ‘water towers’ – the sources of high-quality freshwater. Mountains supply more than half the global population with water for agriculture, domestic uses, and industry, often in places far from the mountains. The world’s largest irrigation system, in Pakistan’s Indus Basin, depends on mountain water; but so do the inhabitants of Los Angeles, supplied by water piped under the Sierra Nevada and across much of the state. Mountain water is also a source of renewable energy: hydropower, largely developed in many countries in Europe and in the USA, but with great potential for development in other parts of the world – though the social and environmental consequences of dam building, and decisions about who benefits are always complex.

Mountains are also global hotspots of biodiversity. For our growing global population, their foremost value is as centres of agrobiodiversity; the places where most of our major food crops originated. As with potatoes, introduced to Europe from the Andes in the late 16th century, crops that have not so far been widely grown outside the mountains may enable more mouths to be fed; demand for quinoa production, for instance, has grown 20-fold over the past decade. In addition, the genetic diversity of original varieties living in mountain areas may become ever more valuable as climate change progresses. Another aspect of mountain biodiversity is that a particularly high proportion of mountain plants and animals – from gorillas to pandas to edelweiss – are both iconic and endemic, limited in their distribution to very restricted areas. Some are threatened by hunting, the development of infrastructure, or climate change.

Yet they are also attractive to both TV viewers and tourists and, especially where local communities can find a way to channel a significant proportion of the income from tourism to support their livelihoods and societies, biodiversity can have both global and local benefits. This is also true for other mountain species, particularly mushrooms and medicinal herbs, which have global markets but should be sustainably harvested by local people who should then realise an equitable proportion of the eventual sale price, often in cities on another continent. Today, it is the middlemen who usually make most of the profit.

Yosemite National Park on the Sierra Nevada, by David McConeghy from Oxford, OH, USA. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Yosemite National Park on the Sierra Nevada, by David McConeghy from Oxford, OH, USA. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.As now than more half of humankind now lives in urban areas – including many cities, some of them very large, in mountains – we increasingly recognise the benefits of mountain areas as places to escape to. Some people go to the mountains just at weekends, to hike, ski, climb or just enjoy the scenery and high-quality food. Many of us spender longer holidays there, and others, sometimes known as ‘amenity migrants’, live in the mountains for an increasing part of the year just because that is where they want to be; not because their jobs are there. Such people are now found living in mountains in many parts of the world, from California to the Philippines to the Czech Republic. Both visitors and locals need good infrastructure – roads, internet access, and sometimes railways. As the climate warms at lower altitudes, mountains may become more important as places for escape.

Already, some of the clearest evidence of climate change comes from the mountains: shrinking glaciers and plants moving to ever-higher altitudes. Increased numbers of visitors to mountain areas may bring new economic opportunities, but at the same time, they will only be able to come if transport links remain safe and reliable. This will be a real challenge for many mountain communities in the future, as the numbers of heavy rainfalls and other extreme events increase, together with natural hazards such as avalanches, floods, and landslides. In the past, mountain people have been able to live in challenging environments particularly because they have worked together to build terraces and irrigation systems and to manage forests and pasture land.

If we recognise the global importance of mountain areas, this implies a greater need for stronger partnerships, involving not only mountain people but all of us who depend on the mountains in so many ways.

Featured image credit: “Dawn”, by danfador. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Do mountains matter? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 10, 2015

‘Your fame will be sung all round the world': Martial on the convenience of libraries

“Your library of a gracious country villa, from where the reader can see the city close by: might you squeeze in my naughty Muse, between your more respectable poems?” Martial’s avid fans will find themselves on familiar ground here, at the suburban ranch of the poet’s aspirational namesake, Julius Martial (4.64). Then as now, the breezy ridge of the Janiculan was one of Rome’s most desirable locations, handy for town but serenely above its crowds, businesses, and industries: only the super-rich get a full night’s sleep (cf. 12.57), while Martial tosses and turns in the incessant noise pollution of the city below (9.68), only to have to get up at the crack of dawn every morning so he can pay his respects to powerful patrons (e.g. 5.22).

Such villas often had private libraries; you can find out more about them from Lionel Casson’s Libraries in the Ancient World (2001). Some were serious research tools: the most famous example is the Villa of the Pisos at Herculaneum, the so-called ‘Villa of the Papyri’, which has yielded charred fragments of many previously unknown ancient texts on philosophy and literary criticism (and is the model for the Getty Villa in Malibu).

Libraries were sometimes decorated with portraits of authors whose works they housed; the younger Pliny (Letters 4.28) is keen to source some as a favour for his friend Herennius Severus, ‘that great intellectual’. At 7.84, Martial brags that a fan has commissioned just such a portrait of him, painted on a wooden board (as was common in antiquity; the famous Fayum mummy portraits are examples), and this must have been for a private library – compare the preface to book 9. Julius Martial’s library is bound to have included a portrait of his friend. At 5.20 (about which I’ve blogged), when Martial pictures their ideal day together, it includes relaxing over ‘some little books’ – perhaps in a public library, or at their favourite baths, but why not here?

“Your fame will be sung all round the world…”

Ruins of the Villa of the Papyri at the archeological site of Herculaneum, photographed in May, 2000. Image Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Ruins of the Villa of the Papyri at the archeological site of Herculaneum, photographed in May, 2000. Image Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Libraries are a safe haven for Martial’s work; he can’t stop imagining the grisly fates that can befall an unwary book adrift in the big city (e.g. 2.1, 3.2, 3.5, 4.10). In return, he safeguards their future for all eternity – by writing about them, in the books they shelter. The ultimate private library was of course the emperor’s. Martial likes to imagine that Domitian is a fan (1.4, 2.91-2, 4.8, 5.2), and tries to haggle with the court librarian over exactly where he should come in the catalogue, “Please find room for my little books on whatever shelf Pedo, Marsus, and Catullus share.” (5.5)

These are the bygone poets whom he keeps trying to claim as illustrious forebears (e.g. book 1 preface); Martial is always keen to assert his place in a literary pecking order (7.68), though as in 7.17, he’ll take whatever shelf-space he can get.

Late in life, when he retires back to his peaceful little Spanish hometown, libraries (whether public or private) are one of the Roman amenities Martial misses most. They were an integral part of the social scene in which he people-watched and sharpened his wit, “the libraries, the theatres; and those parties…” (book 12 preface)

The younger, citified Martial’s own vision of the good life had been decidedly rustic, and included “just a few books – provided I get to pick them” (2.48); and early in book 12 we do find a honeymoon period of gloating (12.18, 12.31) that he has finally escaped the urban rat-race. By the time he writes the book’s preface three years later, though, he is pining for the capital’s libraries – perhaps not so much as centres of learning (Bilbilis must have had its own) but for the wonderful conversations and chance encounters he had enjoyed there.

The post ‘Your fame will be sung all round the world': Martial on the convenience of libraries appeared first on OUPblog.

Cautious optimism on “No Exceptions” with important caveats

As pleased and excited as I am, by Ash Carter’s announcement, that women will be allowed in all military occupational specialties, I am also concerned that we do it right. Otherwise we may have public failures that cause people to question the decision.

The media and public discussion is preoccupied with the strength of military women: can they make it through Ranger training? Can they drag their wounded comrades to safety?

While these issues are important I am more concerned with other medical issues which may cause problems with the unit fighting strength, cohesion, and morale. These have to do problems which may cause women to under-perform or leave military service early. However all of these problems can be remedied by relatively simple steps, if the military leadership and the public are willing to grapple with them.

The following subjects are uncomfortable. They focus on reproductive and genito-urinary issues, often avoided in public discourse. But they need to be discussed, as the vast majority of military women are in their childbearing years.

“November 13, 2007. The Karakal Battalion during its first winter training session, held in an open area in Southern Israel.” by Israel Defense Forces. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“November 13, 2007. The Karakal Battalion during its first winter training session, held in an open area in Southern Israel.” by Israel Defense Forces. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.One of the biggest problems for active women in the military is unintended pregnancy. Enlisted single service women have double the rate of unintended pregnancy as their civilian counterparts. This is not because women in the service are more promiscuous than their counterparts, I believe, but because birth control is often less available. In the theater of war, until recently in Iraq and still in Afghanistan, birth control may be hard or impossible to obtain in a discreet manner. The same is true on ships.

So if a service woman gets pregnant, and chooses to carry her baby to term, she is not able to deploy. After giving birth, she has six to twelve months (depending on the service) before she can deploy again. This leads to wide spread resentment that she is “getting pregnant to avoid deployment.”

If she chooses to have an abortion, the Military Health System does not pay for the abortion, except in the case of rape or incest. Many women are stationed in foreign countries, such as Korea or Japan, where abortion is illegal. Thus they face the choice of having an illegal abortion, or asking their commanding officer for leave to go back to the US and have an abortion, which can be a very embarrassing situation for these women.

Another health issue for women in the field is the difficulty of finding clean safe bathrooms. I wrote about this in 1990 after being in the field for extended periods in Korea on the DMZ, where porto-potties were often filthy. A women has to take off her “Battle rattle” in order to urinate. There was no place to put your gear down that was not a mess. In Somalia, often there were very long lines for the few porto-potties.

In Kosovo, Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Iraq, if on a convoy, it was too dangerous to stop. Men can urinate in a bottle; it is almost impossible for a woman to do that. Unfortunately, in 2011 in Afghanistan, female soldiers had to wear diapers while on the road.

Thus many female service members restrict fluids, so as to avoid the need to get outside the vehicle to urinate, and potentially be shot or step on an IED. This leads to urinary tract infections (UTIs), and dehydration. If a female service member is experiencing the intense pain from an UTI, she may not be an effective member of the fighting force.

The Female Urinary Diversion Device (FUDD) is a potential solution. While it takes some practice, it is a relatively simple way to be able to urinate without stopping.

Having your menstrual period in the deployed environment is another potential distractor. Another simple strategy is to have women go on commonly prescribed contraceptives to suppress their cycle when in the field. This is not only safe, but covers birth control as well.

Some people reading this blog will say that I am emphasizing all the reasons women should not be in the military, I would counter that argument with stressing how essential women have been to the forces fighting in the “Long War.” Recognition of their different biology will further enhance their success.

Featured image credit: “U.S. Marine Cpl. Mary E. Walls (right), an ammunition technician, and linguist Sahar, both with a female engagement team, patrol with 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment in Musa Qa’leh, Afghanistan, on Aug. 6, 2010″ by Cpl. Lindsay L. Sayres, U.S. Marine Corps. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Cautious optimism on “No Exceptions” with important caveats appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers