Oxford University Press's Blog, page 574

December 14, 2015

Reaganism and the rise of the carceral state

In the moment of Black Lives Matter, with public awareness of mass incarceration and lethal force by police reaching new heights, it’s important to look back on the racial dimension of what I call “the Reagan era” and how that politics led us to where we are now.

Today’s carceral state has its roots in the “war on crime” that took hold in America in the 1980s. That “war” was led by the political forces that I associate with Reaganism, a conservative political formation that generally favored a rollback of state power. A notable exception to this rule was policing and imprisonment. Both Reaganism and the “war on crime” had a racial politics embedded in them, so that these three phenomena—Reaganism as a movement, the “war on crime” and the resulting carceral state, and the racial politics of the 1980s—strengthened and reinforced the others.

All those who care about racial equality of a certain age are likely to remember the 1980s as a bleak time for people of color and for African Americans especially. The social reality of the era was complex. More African Americans were making it into the middle and upper classes than ever before, while others were stuck in impoverished urban neighborhoods. Because of middle-class flight, being a big-city mayor in the 1980s was very challenging; nonetheless, it is significant that, during this decade, African Americans were elected or reelected mayor in four of the country’s five biggest cities (Los Angeles, Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York City).

While African American political power was growing in the city, at least by some measures, Ronald Reagan and the broader conservative movement he led were often openly hostile to urban America and African Americans. When Reagan ran for president in 1980, he peddled a fictionalized tale, one with an obvious racial subtext, of what he called a “welfare queen” living large on the public dole, and he visited Bob Jones University, a segregationist institution in South Carolina, which he called a “great institution.” Moreover, throughout his political career, Reagan was antagonistic toward civil rights law. That was his record, a long record—one that was interrupted only at moments when Reagan bent to irresistible political forces, as when he signed a 25-year extension of the Voting Rights Act in 1982. Reagan was a realist, but there is no mistaking the broad pattern of his views about civil rights.

Amid this political context, the “war on crime” took hold. What did this “war” consist of? At the federal level, “mandatory minimums” were created that treated crack possession far more harshly than possession of powder cocaine, and other laws were enacted that aimed at making sure convicted criminals went to prison and stayed there longer. Meanwhile, U.S. Supreme Court rulings made it easier for police to get convictions. Between 1980 and 1990, the rate of incarceration in America, taking the federal government and the states together, more than doubled—from 139 per 100,000 Americans to 297 per 100,000.

Ronald Reagan did not do all this himself. He played no role in passing laws at the state level. He didn’t appoint local prosecutors. Supreme Court justices appointed by Reagan’s predecessors provided sufficient numbers for majorities in the relevant decisions. We need to come to grips with the broad political forces that caused the incarceration surge, forces of which Reagan was simply the foremost leader, sometimes merely a symbolic leader. This is about Reaganism, not just Reagan. That extends downward to the decisions of state legislators and to prosecutors who may have decided to push for harsher sentencing. And it extends outward from avowed conservatives to many moderates, and even liberals—for example, members of the Congressional Black Caucus—who supported the “war on crime.” One of sign of Reaganism’s success was its capacity to attract wide support at many moments, even from people who supposedly were not conservatives.

Overcrowding in California State Prison, 2006. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Overcrowding in California State Prison, 2006. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In order to understand the broad appeal of these tough-on-crime measures, we also have to see that the fear of crime and urban disorder was raging in America during the 1980s. This tide of fear swelled enormously in the late 1970s, and continued to roll through the 1980s and into the 1990s. Historians need to acknowledge that the long-term increase in rates of violent crime, starting in the 1960s and extending into the 1980s, was real, and they should have sympathy for Americans, most of all for city-dwellers, who were legitimately afraid of violent crime. Sensationalistic media coverage stoked that fear, sometimes in ways that were irrational or destructive. But this was fertile territory, for tabloid journalists and for opportunist politicians, because the fear was already there and the crime was real. It wasn’t racist for people to be afraid of crime, but that fear took the form of a panic, which is never good, and the panic was strongly racialized, which made it truly poisonous.

As many understand now, tough-on-crime policies don’t have to be explicitly race-based or consciously race-biased in order to produce racially disparate outcomes. But the “war on crime” and “war on drugs” measures instituted at all levels of government in the 1980s were often, I believe, consciously directed at young black and brown men. One study (cited by the economists John Bound and Richard Freeman) later found that, between 1980 and 1989, the percentage of African American men aged 18 to 29 without high school degrees who were prisoners rose from 7.4 percent to 20.1 percent. How likely is it that this dramatic, seemingly targeted change, occurring in a rather compressed time period, was just an unforeseen outcome? I would argue, not very likely. I would suggest that those legislators, mayors, and elected prosecutors who stood for office in America’s cities and supported the new lock-’em-up regime understood very well who was going to get caught in the net. At the time, young men of color who were engaged in the illegal drug trade got far less sympathy than they do today. Today, we tend to call many of the crimes for which such men have gotten convicted nonviolent. Back in the 1980s, Americans across the political spectrum treated drug-sellers as people engaged in an intrinsically violent activity, as predators who were tearing poor communities apart and who often targeted children.

It can be disturbing to revisit the 1980s and look at the origins of today’s policing and incarceration state. This is part of the balance-sheet of Reaganism. But if we wish to assign blame, there is a lot of it to go around.

A version of this article originally appeared on the Columbia University Press blog

Featured image credit: Photograph of President Reagan at a Reagan-Bush Rally in New York – NARA – 198556. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reaganism and the rise of the carceral state appeared first on OUPblog.

Intentional infliction of harm in tort law

The tort of intentional infliction of harm would seem to encapsulate a basic moral principle – that if you injure someone intentionally and without just cause or excuse, then you should be liable for the commission of a tort – in addition to any crime that you commit. Occasionally, judges have held that there is such a principle, which is of general application: eg, Bowen LJ in Mogul Steamship v McGregor Gow & Co (1889). While this principle is now uncontroversial in cases of the intended infliction of physical harm (see Bird v Holbrook [1828]), the position has been unclear in so far as it concerns the causation of psychiatric harm. The most important case on intended infliction of psychiatric harm (IIPH) was Wilkinson v Downton (1897). But that case has long been doubted because the defendant had been playing a practical joke upon the claimant, telling her that her husband had been involved in an accident and was lying ‘smashed up’ at Leytonstone. Wright J could find no actual intention to harm, but held that an imputed intention to harm was sufficient to create liability.

In the UK, the development of the IIPH tort came to something of a juddering halt after the passage of the Protection from Harassment Act 1997, given that harassment was an important context in which the tort had operated. Following the decision of the House of Lords in Wainwright v Home Office (2004) IIPH seemed to be all but extinguished. One reason for this was that Lord Hoffmann was unconvinced of the need for such a tort (following reservations expressed in Hunter v Canary Wharf Ltd [1997]). Another was that his Lordship was wary about any principle of liability that did not feature a very precise definition of intention.

The significance of the recent case of Rhodes v OPO (2015) is that it appears simultaneously to revive the IIPH tort and to provide a fairly precise definition of intention. However, it was an unusual case in which to raise the issue, because it involved a claim for an injunction to prevent the publication of a book by a well-known modern pianist. The pianist wanted to tell of the acts of sexual abuse committed against him when he was a child – and the book contains graphic descriptions of what happened. The composer’s ex-wife was concerned that their young son would eventually read the book and, because of various illnesses that made him psychologically vulnerable, would be likely to suffer mental distress (or worse) as a result. An important point made in OPO is that intention is not to be equated with mere recklessness. Thus, Lady Hale and Lord Toulson held that the IIPH tort would be committed where there was an actual intention to cause severe distress, which in fact results in a recognised psychiatric illness.

The OPO decision is both welcome and a disappointment. It is welcomed because it acknowledges the importance of attaching legal consequences to the intentional infliction of harm – which, as already noted, reflects a basic moral principle. OPO also formally brings the causation of both physical harm and psychiatric illness within the same principle. But the decision is disappointing because it provides a restricted definition of intention – which is likely to be satisfied in few cases beyond those with a criminal element to them. One reason for the narrow definition was that OPO arose from an allegation that the tort would be committed following the publication of a book. The case gave rise to freedom of speech concerns, which undoubtedly influenced the court’s formulation of an appropriate principle of liability. Lord Neuberger said that it would “be vital that the tort does not interfere with the give and take of ordinary human discourse (including unpleasant, heated arguments…).” We might even say that it was a ‘hard case making bad law.’

A tight definition of intention which excludes recklessness might be necessary to keep the intentional infliction of harm tort within reasonable bounds – insofar as claims for psychiatric illness are concerned. But is it satisfactory to exclude the tort in cases of recklessness causing physical injury? Claimants who can prove recklessness, of course, will have an action in negligence. But such an action will be restricted because any consequential damage will need to be foreseeable – whereas no such restriction applies in intentional tort. A related difficulty is that the Supreme Court obviously wants proof of subjective intention to harm. But a court will rarely have direct evidence of what was running through a defendant’s mind when he or she acted – unless this has been recorded on Facebook or Twitter beforehand, as it occasionally is! – and will often have to turn to an objective assessment of the facts in order to decide whether that subjective intention was present or not. But when that is so, the difference between ‘subjective intention’ and recklessness becomes very harder to discern.

The problem with ring-fencing liability is, then, that courts will insist upon a clear finding of intention so as not to be accused of deciding on the basis of recklessness alone. Again, such a policy might (just) be defensible in cases of psychiatric illness, but there seems little justification for such an approach in cases of physical injury.

To give just one example of where this approach might prove a bit limiting: What of the schoolyard bully who mercilessly taunts another student about some matter, such as his or her sexuality, so that the latter then commits suicide? Although the case would likely fall within the Protection from Harassment Act 1997, I am not sure that it would fall within the OPO principle – because one simply cannot assume any intention to kill.

Featured image credit: Lady Justice case law by AJEL. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Intentional infliction of harm in tort law appeared first on OUPblog.

December 13, 2015

“Both a Democracy and a Republic” – an extract from Debating India

Public debates have long been a tradition in India and have played a major role in shaping the country’s politics. This especially held true following India’s struggle for independence as national leaders considered the kind of country India should aspire to be. India is a democracy now, but was this what the authors of the Constitution intended? In the following extract, Bhikhu Parekh offers an answer to this fundamental question and reflects on the evolution of the Indian government.

Although India is a democracy, this does not fully describe what the authors of its Constitution had in mind. The Congress resolution on the Objectives of the Constitution moved by Jawaharlal Nehru in the Constituent Assembly on 20 November 1946 included the word ‘republic’ but not ‘democracy’. When asked why, he replied that the former ‘included’ the latter. His reply implied that the term republic was wider than and did not mean exactly the same as democracy, but he did not spell out the difference. After some weeks when the first draft of the Constitution was introduced, it included the word ‘democracy’ but dropped the word ‘republic’. Its final draft had both and declared India a ‘democratic republic’. For its authors, the country was meant to be not just a democracy but also a republic, and it has since 1950 celebrated a republic day separately from its Independence day and given it a very different orientation. This raises the question of what they meant by the two terms and why they did not think either enough. The two terms are also translated by different words with different histories and meanings in vernacular languages (prajasatta or ganarajya as different from lokshahi).

It is often argued that India was declared a republic because rather than retain the British monarch as its formal head as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand had done, it chose to elect its own. While this is true, it is not enough. Since India had made that choice sometime ago, it does not explain why the Constituent Assembly vacillated over what to call the country. More importantly, it stresses only the formal features of the idea of the republic and ignores the deeper meaning and significance it had for its advocates.

“Dancers performing in the 2015 Republic Day Parade in New Delhi” by Pete Souza. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Dancers performing in the 2015 Republic Day Parade in New Delhi” by Pete Souza. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Many leading Indians from the mid-nineteenth century onwards were fascinated by and had written admiringly about the Indian and Western republics from their different perspectives. The republican idea was particularly popular among the spokesmen of the Scheduled and ‘lower’ castes. Jotirao Phule, one of their ablest and earliest spokesmen, had read and was influenced by the Western republican writers including Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man, and praised the republican spirit of equality, love of liberty, and commitment to public well-being. He attributed the post-Renaissance resurgence of Europe to the rise of the republics and the decline of India to the overthrow of the Buddhist republics by the Brahmanic monarchies. Ambedkar took a broadly similar view and was particularly interested in the French and American republics. He studied the latter closely during his years at Columbia University, wrote and lectured on the subject, and made a powerful case for making India a republic. He admired the French revolution of 1789 and its ‘republican’ and egalitarian spirit. His Independent Labour Party (founded in 1931) was later called the Republican Party of India. Although this happened after his death, he had already set the wheels in motion.

Several mainstream liberal and socialists leaders too were great admirers of the republican form of government. Jawaharlal Nehru wrote about the modern European republics in his Glimpses of World History, praising their great virtues such as civic courage, public spirit, egalitarian ethos, and love of freedom, and was most enthusiastic about the French revolution. He declared himself a republican in his Presidential address at the Lahore session of Congress in 1929 and came close to equating republicanism with socialism. J.P. Narayan, Lohia, Narendra Dev, M.N. Roy, and others shared his view.

Although these and other advocates of the republic drew their inspiration from different sources and stressed its different features, they shared a broad consensus on what it meant and why it was important. For them, it overlapped with but was not the same as democracy and referred primarily to neither an elected head of state nor even a form of government as democracy did but to a political and social order characterized by four important features. These were social and economic equality, the state as a public institution, an active and public-spirited citizenship, and separation of powers.

Featured image credit: “The national flag of India hoisted on a wall adorned with domes and minarets” by Dennis Jarvis. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Both a Democracy and a Republic” – an extract from Debating India appeared first on OUPblog.

Fragile democracy, volatile politics and the quest for a free media

A free media system independent of political interference is vital for democracy, and yet politicians in different parts of the world try to control information flows. Silvio Berlusconi has been a symbol of these practices for many years, but recently the Hungarian Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, has been in the spotlight. The latter case shows that young and emerging democracies are particularly vulnerable to media capture by political and corporate interests because of their fragile institutions, polarised civil society and transnational economic pressures. However, we know very little about these young and often deficient democracies in different parts of the world. Most of the existing literature concentrates on the United States, Great Britain or Germany and their experiences are anything but universal. Most of the new democracies lack the socio-economic conditions and institutional structures that characterised the evolution of media in the Anglo-Saxon world.

Politicisation of the state represents one distinctive and often troubling feature identified in new democracies. ‘Business parallelism’ represents another common feature, with some media owners actively engaged in politics and in business at the same time. Media ownership in these countries is quite fuzzy and not sufficiently transparent. Journalists are often underfunded, poorly trained, divided and disoriented. All this makes it difficult for the media to act as independent and unbiased providers of information.

Numerous deficiencies in democratic structures make it difficult for the media to perform properly. A weak state, hegemonic and volatile at the same time, dysfunctional parties, and unconsolidated democratic procedures, all lead to media capture by political and corporate interests. Continuously changing institutional structures produce uncertainty in the field of journalism and prevent the establishment of clear professional norms and routines. Political and journalistic cultures in the countries under consideration often reveal basic features of what a Polish sociologist, Piotr Sztompka, called civilizational incompetence: the lack of respect for law, institutionalized evasions of rules, distrust of authorities, double standards of talk and conduct, glorification of tradition, idealization of the West (or the North.) They lead to lax and non-transparent “Potemkin institutions,” “economies of favours,” hidden advertising (also known as “pens for hire,”), the practice of “compromat” (i.e. smearing political or business competitors), and ordinary corruption in some cases.

Journalist by clasesdeperiodismo. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Journalist by clasesdeperiodismo. CC BY-SA 2.0 via FlickrMany of the liberal solutions adopted or aspired to in the early years of democratic transition have been abandoned or undermined in the countries under consideration. Some governments in these new democracies adopted sophisticated new methods for controlling journalists and information flows, sometimes to the point where the demarcation line between so-called democratic and authoritarian regimes becomes blurred. Traditional forms of coercion and corruptive practices are not abandoned either, making it difficult for the media to scrutinise politicians and civil servants. It is not by chance that foreign investors have progressively abandoned the media field in some of the new democracies: they have seen their investments generating fewer and fewer profits, while pressures from politicians and governments have become more intrusive.

That said the media are not just innocent victims of political and economic manipulation. Rather than acting as an independent watchdog and provider of non-biased information, they have often sided with their business or political patrons, indulging in propaganda, misinformation, or even smears. Manifestations of journalists’ intense or even “intimate” relationships with politicians and media owners abound. Informality prevails over formal normative and procedural frameworks and those informal networks are maintaining and even increasing their importance.

The media and democracy condition each other. Democracy cannot thrive without a free and vibrant media, but the opposite is also true. Democratic deficiencies make it impossible for the media to function properly. Examples of these corrupting interdependencies abound in new democracies, blurring the line between democracy, autocracy and despotism.

However, despite all the deficiencies and problems new democracies reveal the persistent quest for transparency, for equal treatment under the law, for plurality and independence in the world of the media. Media freedom may well be compromised by vested economic interests, political manipulation and cultural habits, but it remains a cherished value in all the countries under consideration.

The post Fragile democracy, volatile politics and the quest for a free media appeared first on OUPblog.

Holograms and contemporary culture

Holograms are an ironic technology. They encompass a suite of techniques capable of astonishingly realistic imagery (in the right circumstances), but they’re associated with contrasting visions: on the one hand, ambitious technological dreams and, on the other, mundane and scarcely noticed hologram products. And today, probably more people have imagined or talked about holograms than have examined them first-hand. Holograms occupy an unusual no-man’s land in contemporary culture. Over nearly seventy years in development, their engineering achievements, commercial applications and anticipated future have fitted together uncomfortably. The result is a technology that inspires divergent uses and unstable forecasts.

Conceived after the Second World War, the first three-dimensional holograms – amazingly life-like images looming behind glass plates – were publicly revealed in the early 1960s. Encouraged by this technological progress, commercial firms and news media anticipated further improvements. Forecasters confidently predicted that holograms would become even more convincingly realistic: projected into space, visible from all directions and potentially incorporating other sensory cues (for example touch, or ‘haptic’ qualities, which have been a continuing line of research for holographers). Holograms had been expensive and difficult to produce, but developers invented ways of embossing holograms onto plastic and metal, which dramatically expanded the applications and market during the 1980s.

Despite their impressive visual properties, holograms remained challenging to light effectively. In uncontrolled environments, even the most sophisticated holograms could appear washed out, dim or fuzzy. Metal foil holograms, trialled for magazine advertisements and consumer items, could look distorted or distracting. Manufacturers adapted by making holographic images less three-dimensional, and by substituting intricate computer-generated patterns instead of imagery of real objects. The new holograms were much better for their applications – bright and reliably identifiable stickers for children’s books, eye-catching fashions such as gift-wrapping foil, and ‘authentication’ labels for identity documents and valuable merchandise – but owed little to the visual qualities of earlier holograms. From the 1990s, these less-demanding holographic products found wider applications, such as holographic ‘glitter’ adorning garments and cosmetics.

Image credit: Pepper’s Ghost stage illusion by Marion, F. L’Optique (1867), Fig. 73. Used with permission.

Image credit: Pepper’s Ghost stage illusion by Marion, F. L’Optique (1867), Fig. 73. Used with permission.This trend towards simpler non-imaging uses for holograms took the commercial products in a different direction than forecasters had predicted. Promises of holographic media had inspired science fiction writers to imagine a hologram-rich future. These predictions were most compelling when depicted visually in science fiction movies and television. Star Wars imagined Princess Leia as a floating projection of light, and successive series of Star Trek represented a ‘holodeck’, then ‘holosuites’, and finally a holographic doctor materialized by computer-generated imagery. Video games from the 1990s recast holograms yet again: in Command and Conquer: Red Alert 2 ‘mirage tanks’ generate holograms to masquerade as trees; in Crysis 2, a ‘holographic decoy’ can attract gunfire, while in Duke Nukem 3D a hologram is able to engage in battle. Such imagined technologies have become more familiar than real-world holograms to modern gamers. Needless to say, none of these capabilities is yet plausible, feasible or competitive with other technologies.

Popular expectations about holograms have extended from futuristic fiction to present-day understandings. Audiences have broadened the notion of holograms to any optical effect that appears to be three-dimensional or floating. Entertainment and electronics organizations carry significant responsibility here. For example, a Victorian stage illusion known as ‘Pepper’s Ghost’ has been the basis of theme park attractions such as Disneyland’s ‘Haunted House’ ride, the Hatsuni Miku ‘virtual star’ in Japan and the Tupac ‘hologram’ performance at the Coachella 2012 festival. But these striking illusions have been domesticated, too. CNN news coverage of the 2008 American election touted its remote reporter visualized ‘via hologram’ and interacting with her counterparts in the main news studio as cameras panned around them. As technologists soon complained, this misrepresented conventional blue-screen video technology to gullible viewers. And for younger audiences, it is difficult to find new hardware for 3-D tablet displays or augmented reality that has not been labelled ‘holographic’ by the manufacturer, reviewers or eager customers.

Thus optimism and credulity, in equal measure, have dogged popular notions about holograms in the early twenty-first century. Engineering achievements, consumer reality and popular anticipations about holograms jostle. Unsurprisingly, the growing disparity between public expectations and achievable goals is a matter of some dismay to practising holographers and firms.

Today, holograms are in our pockets (on credit cards and driving licenses) and in our minds (as gaming fantasies and ‘faux hologram’ performers). But the recurring question for producers and enthusiasts is: why aren’t holograms more often in front of our eyes? For the time being, it seems, the anticipated wonders of holograms have outpaced our ability to deliver them.

Featured image credit: £20 Holograms by Evan Bench. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Holograms and contemporary culture appeared first on OUPblog.

Wealth, status, and currency in Shakespeare’s world [infographic]

In 1623, one kilogram of tobacco was roughly five times more expensive than Shakespeare’s newly published First Folio. The entire collection, which cost only £1, contained thirty-six of his works, many of which incorporate 16th- and 17th-century notions of status, wealth, and money. Most of his characters are garbed in colors and fabrics befitting their social standing, and he frequently presents foreign currencies alongside English coins. So how do the rich and poor fare in Elizabethan England? Explore the infographic below to discover the coins, dress, and literacy of Shakespeare’s world.

Download the infographic as a PDF or JPG.

Featured Image: “A party in the Open Air. Allegory on Conjugal Love” by Isaac Oliver. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Wealth, status, and currency in Shakespeare’s world [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

The paradoxes of Christmas

While most of you probably don’t believe in Santa Claus (and some of you of course never did!), you might not be aware that Santa Claus isn’t just imaginary, he is impossible!

In order to show that the very concept of Santa Claus is riddled with incoherence, we first need to consult the canonical sources to determine what properties and powers this mystical man in red is supposed to have. John Frederick Coots and Haven Gillespie tell us, in the 1934 classic “Santa Claus is Coming to Town”, that:

He sees you when you’re sleeping.

He knows when you’re awake.

He knows if you’ve been bad or good.

So be good for goodness sake!

But can Santa always know if you’ve been naughty or nice?

First of all, it is worth making a rather simple observation: If one tells a lie, then one is being naughty, and if one is telling the truth, then one is being nice (unless one is doing something else naughty at the same time, a possibility we shall explicitly rule out below). After all, my mother, an expert on the subject, told me many times that lying is naughty and truth-telling is nice, by both her own lights and by Santa’s. You wouldn’t call my mother a liar, would you?

Weihnachtsmann in Annaberg-Buchholz, by Kora27. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Weihnachtsmann in Annaberg-Buchholz, by Kora27. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Now, consider Paranoid Paul. Paul, who is constantly worried about whether he has been nice enough to get presents from Santa, at some point utters:

Santa knows I’m being naughty right now!

Assume, further, that Paul is not doing anything else that could be legitimately assessed as naughty or nice. Now, the questions are these: Is Paul being naughty or nice? And can Santa know which?

Clearly, Paul isn’t being naughty: If he is being naughty, then Santa would know that he is being naughty, via the magical powers attributed to Santa in the aforementioned carol. But if Santa knows that Paul is being naughty, then what Paul said is true, so Paul isn’t lying. But since he isn’t doing anything else that could be assessed as naughty, Paul isn’t being naughty after all.

But equally clearly, Paranoid Paul isn’t being nice: If he is being nice, then Santa would know he is being nice. But that would imply that Santa doesn’t know that Paul is being naughty, by the Principle of Christmas Non-Contradiction:

PCNC: No single action is simultaneously naughty and nice.

But then Paul is lying, since he said that Santa does know that he’s being naughty. And lying is naughty, so Paul isn’t being nice after all.

Of course, there is nothing to prevent Paranoid Paul from uttering the utterance in question. And, if he does so, then surely he is either being naughty or being nice – what other Christmas-relevant moral categories are there? (We might call this the Principle of Christmas Bivalence!) So the problem must lie in the mysterious magical powers attributed to Santa Claus in the song. Thus, Santa Claus can’t exist.

This Christmas revelation is probably shocking enough to most of you. But I’m afraid it gets worse.

It is well-known that Santa Claus gives presents to children on Christmas night. What is most important for our purposes are the two strict rules that govern Santa Claus’s Christmas gift-giving. The first of these we might call the Niceness Rule:

Nice: If a child has been nice (overall), then he or she will receive the toys and gifts he or she desires (within reason).

And the second we can call the Naughtiness Rule:

Naughty: If a child has been naughty (overall), then he or she will receive coal (and nothing else).

Following these rules is an essential part of what it is to be Santa Claus – these rules codify his place and purpose in the universe. Thus, they are non-negotiable: Santa does not, and cannot, break them.

This Christmas revelation is probably shocking enough to most of you. But I’m afraid it gets worse.

Let’s again consider Paranoid Paul, who as usual is worrying about his status with respect to the naughtiness/niceness metric. Assume further that, at one minute before midnight on December 24th (the well-known deadline for Santa’s final yearly naughty/nice judgments) Paul’s actions over the past year have, unbeknownst to him, fallen precisely on the line separating the overall naughty and the overall nice. He only has time for one more action, and if it is nice, then he will get the presents he want, and if it is naughty then he will only get coal. Paul, who is aware that his behavior over the past year has been less than exemplary, utters:

I’m going to get coal for Christmas this year!

Such an utterance prevents Santa Claus from giving anything – coal or goodies – to Paranoid Paul.

Santa can’t give Paranoid Paul toys and gifts. If Santa gives Paul toys and gifts, then he can’t give him coal. But this means that Paul told a lie, which would push him over into overall naughtiness. But then Santa should have given him coal, not goodies.

But Santa also can’t give Paul coal. If he gives Paul coal, then Paul was telling the truth. This would push Paul into overall niceness. But then Santa should have given him toys and presents, not coal.

Thus, we once again see that the very concept of Santa Claus is outright inconsistent. And since Santa Claus is an integral part of Christmas, this means that Christmas itself is incoherent, and hence must not exist.

And that’s how the Grinch proved that there’s no Christmas!

I hope everyone who reads this column (regardless of which, if any, winter holiday you celebrate) has a wonderful month and a safe winter holiday! See everyone next year, and thanks!

Featured image credit: Christmas present. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The paradoxes of Christmas appeared first on OUPblog.

December 12, 2015

Manspreading: how New York City’s MTA popularized a word without saying it

New York City, home of Oxford Dictionaries’ New York offices, has made numerous contributions to the English lexicon through the years, as disparate as knickerbocker and hip hop. One of Gotham’s most recent impacts was the popularization of manspreading, defined in the latest update of Oxford Dictionaries as “the practice whereby a man, especially one on public transportation, adopts a sitting position with his legs wide apart, in such a way as to encroach on an adjacent seat or seats.”

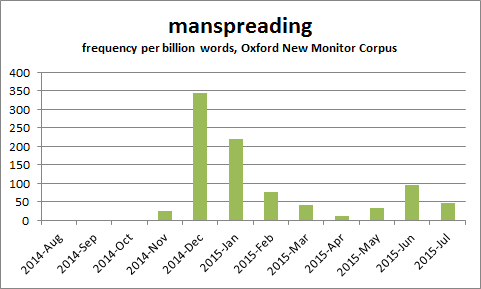

The word met our criteria for inclusion by amassing a large amount of evidence in a wide variety of sources, and it did so in a remarkably short period of time. As the chart below shows, evidence of manspreading on Oxford’s New Monitor Corpus, which is used to track the emergence of new words, closely corresponded with the launch of a campaign by New York’s Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) to encourage courteous behavior on the subway—including ending the practice of taking up more than one seat. Evidence of the word manspreading first registered on our tracking corpus in November 2014 when the campaign was first ‘teased’, and the word’s use shot into the stratosphere in December, when the campaign officially launched.

Most of this early evidence directly mentions the MTA’s “Courtesy Counts” public service campaign, and in the minds of New Yorkers the two are connected—but the MTA assiduously avoided using the word manspreading in its communications. Instead, the posters say “Dude… Stop the Spread, Please.” The Courtesy Counts campaign targets 12 different behaviors, including “pole hogging,” “primping,” loud music, and the wearing of backpacks, but press coverage tended to focus in particular on the “stop the spread” poster, and to refer to the offending posture as manspreading. But how did the MTA’s campaign make the word ubiquitous without actually using it?

The spread of manspread

Manspreading had been simmering on social media for some time before it entered the mainstream consciousness on the coattails of the MTA last winter. Manspreading and related forms are evidenced on Twitter from as early as 2008, although the precise meaning isn’t always clear. An entry for man spread was added to Urban Dictionary in 2010, but with a more general and non-pejorative meaning: “where a dude sits down on a chair and spreads out his legs to make a V shape with them.” By August 2013, the connection with public transport was being made in Australia, and the following spring even some French-speaking Twitter users were using the term to complain about their fellow passengers on the Métro in Paris. 2013 also saw the phenomenon of manspreading (though not the word itself) gain prominence with the founding of a popular Tumblr, Men Taking Up Too Much Space on the Train, which invited its audience to submit pictures of the offending behavior, soon followed by other similar projects devoted to the public shaming of people occupying multiple seats. Interest in the phenomenon was increasing, and a word had emerged to refer to it. All that was needed was a catalyst to raise the word’s profile, and the MTA’s campaign seems to have provided that.

Credit for forging the connection between stop the spread and manspread most likely belongs to the newspaper amNewYork, which is distributed free of charge to NYC commuters. As a commuter paper, it is understandably concerned with matters pertaining to the subway, and in October 2014, even before the MTA’s campaign had been announced, it printed an article headlined: “‘Man spread’ a widening blight on public transportation, say riders.” A straphanger interviewed for the article said she wished the MTA would “put some posters up on the train of a guy sitting like that with a slash through it.” When the MTA announced it was making that dream a reality the following month, amNewYork used the M-word again: “Rude riders who unnecessarily take up space—backpack wearers and ‘man spreaders’—will get a refresher in transit manners.” After that, the MTA and manspreading were conceptually united. Within days of the teaser announcement, man had crossed the pond to the UK press, with the Huddersfield Daily Examiner mentioning the MTA campaign and asking its readers to share their own peeves about commuter behavior. Once the campaign actually kicked off in December 2014, the term truly went viral and international, appearing in publications from England, Australia, the Netherlands, Germany, Korea, and more; by 23 December, the Times of India was declaring “Mumbai’s got its own ‘man-spreaders’.”

Manspreading hit the airwaves, as a topic of segments on The Daily Show and the Jimmy Fallon Show, among others. Celebrities who dared to ride the New York subway were caught up in the manspreading mania, with Tom Hanks being forced to defend his subway posture against manspreading claims, and Dame Helen Mirren commenting of a fellow rider who encroached upon her seat with a wide stance that “He’s doing the classic, the manspreading thing.” Mirren went on to note that while the word was new, the practice wasn’t: “they’ve always done it! It’s just now they’re being called on it.” Indeed, the MTA identified the seat-monopolization scourge in , but at that time referred to the offenders as “space hogs.” A novel aspect of the term manspreading is that it puts the blame for the activity squarely at the feet of the masculine sex.

Is manspreading sexist?

It was no accident that the MTA eschewed the word manspreading. Like the Philadelphia-area transit authority SEPTA, which launched a similar campaign (“Dude, it’s rude”) in 2014, the MTA relied on the word dude. Like guy, dude can refer either specifically to a male person, as in Aerosmith’s 1987 Dude (Looks Like a Lady), or be used (especially as a form of address), for a person of either gender. This gave the agency plausible deniability on any charges of sexist stereotyping, which would not have been the case if they had used the neologism. As interest in manspreading grew around the world in the wake of the MTA campaign, the Toronto Transit Commission was the target of competing efforts by customers, as some urged it to adopt a ban on manspreading and others circulated a petition requesting it avoid the term as sexist for unfairly targeting the behavior of male passengers.

Manspreading follows closely on the heels of a similar buzzword, mansplaining, which refers to the practice (by a man) of explaining something in a manner regarded as condescending or patronizing. In both cases, the male activity is often regarded as an expression of masculine privilege, and the naming of the phenomenon enables its perpetrators to be more easily “called out.” The word man has been a productive element in new words in recent years, and many of its formations, like man boobs, man date, man purse, man cave, man crush, man flu, man hug, mankini, and manscaping, have a quality of mild mockery, poking fun either at masculine foibles, or at the strict limitations of heteronormative notions of masculinity. The word bro, originally short for brother but now most often denoting a type of affable, sporty young man with a penchant for homosociality, has been responsible for a similar flowering of neologisms. There is a critique underlying some of these formations, but it is gentle rather than strident, and their use is not limited to the fairer sex, indicating that the target is in on the joke. These terms carry a mere soupçon of sexism—just enough to preserve a sense of edgy snarkiness that makes them humorous and hashtaggable.

A mutually beneficial arrangement

The association between the MTA’s Courtesy Counts campaign and the word manspreading was unintentional but symbiotic, yielding benefits to both. For journalists, the combination of a punchy neologism describing a widely recognized but hitherto unnamed phenomenon with an actual news hook—a campaign by a major city’s transportation authority—proved irresistible. A flurry of news articles around the world took the word manspreading from unknown to familiar in a matter of months. At the same time, that coverage brought tremendous attention to the MTA’s courtesy campaign, making it successful beyond the agency’s wildest expectations (in raising awareness, at least—whether it actually changes New Yorkers’ behavior remains to be seen). The word manspreading existed before the MTA’s campaign, and it might eventually have been popularized without it, but the “Dude, stop the spread” stick man thrust it into the limelight. Whether the word will continue to succeed, or prove a transient phenomenon, only time will tell.

A version of this blog post originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “02a.WMATA.GreenLine.WDC.27October2015″ by Elvert Barnes. CC BY SA 2.o via Flickr.

The post Manspreading: how New York City’s MTA popularized a word without saying it appeared first on OUPblog.

Migrants and medicine in modern Britain

In the late 1960s, an ugly little rhyme circulated in Britain’s declining industrial towns:

‘I come to England, poor and broke

go on dole, see labour bloke

fill in forms, have lots of chatters,

kind man gives me lots of ackers:

“Thank you very much”,

and then he say

“Come next week and get more pay;

You come here, we make you wealthy

doctor too, to make you healthy.”

…

Send for friends from Pakistan

tell them come on as quick as can;

Plenty of us on the dole

lovely suits and big bank roll;

National Assistance is a boon

all the darkies on it soon –

…

Wife want glasses teeth and pills –

all are free we get no bills;

…

Bless all white man, big and small

for paying tax to keep us all.

We think England damn good place

too damn good for white man’s race;

If he not like coloured man –

Plenty room in Pakistan.’

-‘Portrait of Blackburn – Jeremy Seabrook compares the situation of the immigrants today with that of the working class 50 years ago’, (The Listener, 27 August 1970). NHS logo by NHS. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

NHS logo by NHS. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

At the time, seemingly unstoppable mass migration from Britain’s former colonies had triggered a succession of new laws aimed at restricting entry to Britain, followed by a new political emphasis on ‘race relations’ intended to quell international dismay and reduce internal racial tensions. The poem captures exactly the fears that Enoch Powell capitalised on so successfully in his infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ oration. All migrants, it assumes, are leeches on the British body politic and the Welfare State. Migrant filth and fertility, even simple migrant need, would drive out indigenous Britons, excluding them from jobs, homes, and the health services that they themselves funded.

The doggrel of resentment is depressingly persistent. Often entitled ‘Ode to the White Man’, the verses reproduced here were collected by a British journalist documenting life in the declining northern textile town of Blackburn. The poem was probably in circulation even earlier, given its use of the World War Two military slang ‘ackers’ for cash. Yet ‘Ode to the White Man’ has survived and adapted readily to the changing populations and sites of migration. On the internet, ‘white men’ – now Irish, Canadian, Australian, and American as well as English – subsidise ‘regal’ ‘illegals’, thriving on the supposedly lavish largess of American Medicaid, Australian ‘baby bonuses’, and the British NHS. They are in turn enjoined to find opportunities in Mexico, Vietnam, Kosovo, and of course Pakistan. (Some of the many alternatives have been collected online; note that they are no less offensive then the original. Others include a 1970s version of the British verse and a Canadian version.) Instantly adaptable to the latest migration ‘crisis’ or wave of xenophobia, ‘Ode to the White Man’ reflects abiding international stereotypes of migrants as grasping ‘takers’, intent on exploiting the generous welfare provision of the developed world – of which they are presumed to have intricate and sophisticated knowledge.

Yet this strand of the migration discourse – however persistent – never threaded through British culture alone or unchallenged. If anti-immigrationists (and racists) played on popular anxieties about migrants as vectors of disease, or burdens on the NHS, their opponents were equally keen to deploy medical evidence. Since the 1950s, moral panics about ‘imported illness’ have been repeatedly rebutted by the epidemiological surveys that they prompted. By and large, researchers found that British conditions triggered or exacerbated migrant ill-health on the rare occasions where their rates of illness exceeded those of the indigenous population. Clammy and crowded slums offered ideal conditions for tuberculosis infection; young men far from home caught, rather than transmitted venereal disease; and poverty, fears of racial violence and unfamiliarity with (not over-use of) welfare services led to malnutrition among migrants and their children.

Similarly, representations of migrants as ‘deadweights’ on the social services – and especially the health services – have historically been received with nothing short of glee by political cartoonists and social commentators eager to relish the irony. Long before he condemned migrants, Enoch Powell actively recruited Caribbean nurses to satisfy the voracious labour needs of the young NHS. Migrant doctors and nurses have remained essential to maintaining its services ever since, a fact that has become a truism of migration discourse. Indeed, even a candidate in the recent Labour Party leadership campaign reiterated the argument that Britons are ‘more likely to be treated by somebody who’s non-British than to be queuing behind them.’

The National Health Service is, we have been told, ‘the closest thing the English have to a religion.’ Perhaps it is unsurprising that anxieties about a service so close to our hearts also colour discussions about immigration. Both, it seems, are as intimately and inextricably connected to British identity in the twenty-first century as they were in the twentieth. But the relationship between migration and medicine in Britain has never been simple or one-sided, in politics, in the press, or in the everyday hubbub of the Health Service itself. Scrutinising it through any single lens – whether of race, class, politics, or nationality – can only obscure our vision.

Headline image credit: Waiting room anteroom doctors by TryJimmy. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Migrants and medicine in modern Britain appeared first on OUPblog.

Portraits of religion in Shakespeare’s time

Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries was marked by years of political and religious turmoil and change. From papal authority to royal supremacy, Reformation to Counter Reformation, and an endless series of persecutions followed by executions, England and its citizens endured division, freedom, and everything in between. And with such conflict among Christians, there was the perennial need to identify the “other.” Stereotypes of non-Christian groups surfaced in several media. Caricature-like depictions of Jews and Muslims became increasingly prominent among artists. William Shakespeare drew upon the religious unrest of this time period, and incorporated various religious indicators — from accurate portrayals to oversimplified ideas — into his plays, most notably Jewish stereotypes in his character Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. Peruse a slideshow of various works created during the most tumultuous period in English religious history to discover where Shakespeare, and other artists, could have learned these cultural markers.

St. Didacus in prayer

Created by 16th century Antwerp artist Marten de Vos, this painting features St. Didacus praying to an image of Mary and Jesus above an altar. Known as Didacus of Alcalá, a renowned missionary, St. Didacus was later canonized after the Protestant Reformation.

Image: “St. Didacus in prayer” by Maerten de Vos (1591-1600). Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

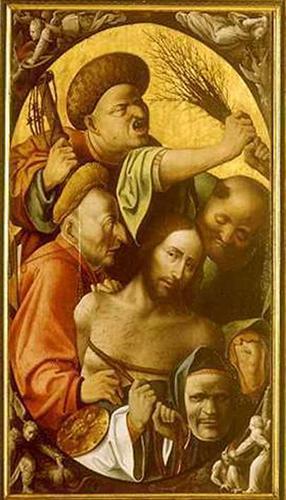

Passion of the Christ

This painting, by artist Hieronymus Bosch, not only illustrates the crucifixion of Jesus, but the common stereotype of Jewish facial features.

Image: “Passion of the Christ” by Hieronymus Bosch. (1515) Public Domain via Wiki Art

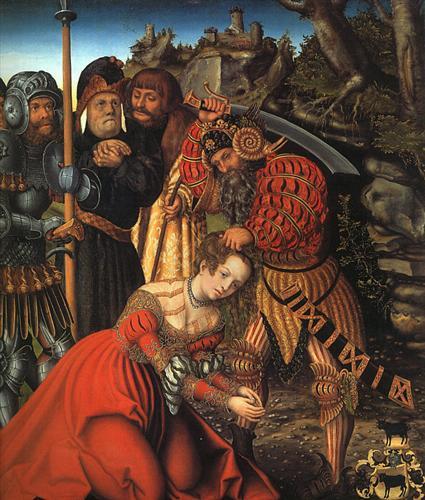

The Martyrdom of St. Barbara

In this painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Barbara is being executed by her father for converting to Christianity. Her father, a pagan, has stereotypical attributes, such as wielding a massive machete and brutally murdering his child.

Image: “The Martyrdom of St. Barbara” by Lucas Cranach the Elder (c 1510). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Public Domain via Wiki Art

Old St. Paul's Cathedral from the East

This engraving of St. Paul’s Cathedral of England was completed by Wenceslaus Hollar in 1652. It is argued that his engravings of Old St. Paul’s give a true general view of the church, although, because of his personal artistic flair, they are not entirely accurate.

Image: “Old St. Paul’s Cathedral from the East” by Wenceslaus Hollar (17th century). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Old St Paul’s (sermon at St Paul's Cross)

This oil painting, by John Gipkyn, was completed in 1616 and also depicts Old St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Similar to the previous artwork, Gipkyn does not remain faithful to the exact architecture of the building, but he does excellently represent the preeminence of the pulpit above the masses.

Image: “Old St Paul’s (sermon at St Paul’s Cross)” by John Gipkyn (161). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Lancelot Andrewes

Lancelot Andrewes was an Anglican bishop and scholar during the reign of Elizabeth I and James I. His influence in English politics and religious matters was great, particularly in his advancement of the career and popularity of John Calvin. The image above is an engraving of Andrewes from the frontispiece of a 17th century book of sermons.

Image: “Lancelot Andrewes” (17th century). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (uploader Dystopos).

Birth and Origin of the Pope

This anti-pope propaganda was one of a set commissioned by Martin Luther for his work, “Against the Papacy at Rome, Founded by the Devil.” The caricature, illustrated by Lucas Cranach, depicts the Pope and Catholic cardinals coming into existence via the devil’s defecation.

Image: “Birth and Origin of the Pope” by Lucas Cranach (1545). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Cranmer's execution, John Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563)

Thomas Cranmer, a leader of the Protestant Reformation during King Henry VIII’s reign, was tried and executed as heretic during the reign of Henry’s daughter, Queen Mary I. He died a martyr for the Protestant faith and was immortalized in many religious texts.

Image: “Cranmer burning Foxe”. Ohio State University Libraries. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (uploaded by Bkwillwm).

Bury Witch Trial Report (1664)

This frontispiece of a 1664 witch trial report highlights a series of executions in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, England. One trial, lasting a single day, resulted in the execution of eighteen people.

Image: “Bury Witch Trial report 1664″ by Edmund Patrick. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

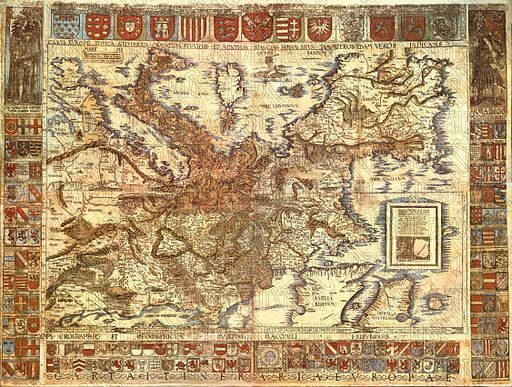

Map of Europe

Cartographer Martin Waldseemüller dedicated this map to Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor of Spain. This map of Europe, though illustrated upside-down, clearly depicts Europe and highlights Italy, the epicenter of Roman Catholicism.

Image: “Carta itineraria europae 1520″ by Martin Waldseemüller. Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck, Austria. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Ingoldsby legends. Merchant of Venice/"'Old Clo'!" [graphic] / AR.

This drawing of Shylock from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice comes from a 19th century book of illustrations. It remains true to the stereotypical Jewish representations in art, overemphasizing Shylock’s hooked nose and frugal nature.

Image: “Ingoldsby legends. Merchant of Venice/”‘Old Clo’!” [graphic] / AR.” by Arthur Rackham (1898?). CC BY-SA 4.0 via Folger Shakespeare Library

[image error]

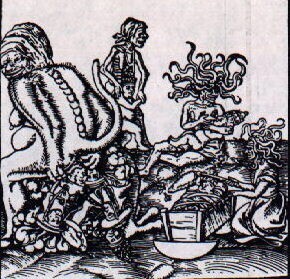

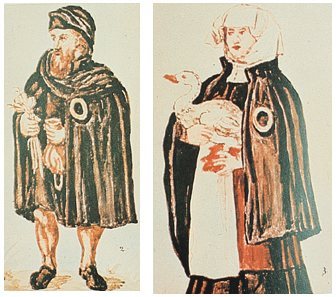

Iudaes. Der Jüd.

In this 1568 woodcut, Jost Amman remains true to Jewish stereotypes by depicting the men with long beards and hooked noses.

Image: “Iudaes. Der Jüd.” by Jost Amman. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The Entrance Hall of the Regensburg Synagogue

Albrecht Altdorfer created this etching of the Regensburg synagogue mere days before it was destroyed and the Jewish population was expelled from Regensburg. Altdorfer was actually one of the chosen few who commanded the Jews to empty the synagogue and leave the city.

Image: “The Entrance Hall of the Regensburg Synagogue” by Albrecht Altdorfer. OASC via

Jews from Worms

In this work by an unknown author, a couple from Worms, Germany wears obligatory yellow badges on their clothes. The man clutches a moneybag and bulbs of garlic, two icons use heavily in stereotypical representations of Jewish men.

Image: “Jews from Worms” by unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

A late voyage to Constantinople…

This illustration from a book published in 1683 documents a Londoner’s travel to Constantinople and other Islamic lands. Like many portrayals of non-Christian people, Muslims too were stereotyped and caricatured.

Image: “A late voyage to Constantinople…” by Guillaume-Joseph Grelot. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Folger Shakespeare Library

Ismāʻīl, the Persian Ambassador of Ṭahmāsp, King of Persia

Ismāʻīl was a son of Shah Ṭahmāsp and a diplomatic representative to the court of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman I. He became the shah of Iran around 1576. Captured here by artist Melchior Lorck, Ismāʻīl is given dramatic facial features and a largely exaggerated turban.

Image: “Ismāʻīl, the Persian Ambassador of Ṭahmāsp, King of Persia” by Melchior Lorck (1557-1562). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Unus Americanus ex Virginia, aetat. 23 [graphic] / W. Hollar ad viuum delin. et fecit.

This etching shows a Munsee-Delaware Algonquian-speaking warrior called Jaques who was transported to Amsterdam from New Amsterdam in 1644. More stereotypical characteristics persist in works created by Christians, typically of those they would often consider to be pagans.

Image: “Unus Americanus ex Virginia, aetat. 23 [graphic] / W. Hollar ad viuum delin. et fecit.” by Wenceslaus Hollar. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Folger Shakespeare Library

Indianen, Erhard Reuwich, 1486 - 1488

This print, made in the late 15th century by Erhard Reuwich, depicts two men talking to each other. The inscription is in both Dutch and Latin, and describes the man on the left in the robes of a cleric and the man on the right in the secular garb of a judge. Both are referred to as Indian, a term also used to mislabel Ethiopians.

Image: “Indianen, Erhard Reuwich, 1486 – 1488″ by Erhard Reuwich. Public Domain via Rijks Museum.

True religion explained, and defended against the archenemies thereof in these times. In six bookes. Written in Latine by Hugo Grotius, and now done in English for the common good.

As the title clearly states, this book was meant to explain the “true religion” and convert those who were Jewish, Muslim, or Pagan to Christianity. Upon close inspection, it is evident that the Christian is looking directly to the Heavens and is the only one receiving the light.

Image: “True religion explained, and defended against the archenemies thereof in these times. In six bookes. Written in Latine by Hugo Grotius, and now done in English for the common good.” by Hugo Grotius (1632). CC BY-SA 4.0 via Folger Shakespeare Library

Featured Image: “Life of Martin Luther” by Breul, H. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Portraits of religion in Shakespeare’s time appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers