Oxford University Press's Blog, page 581

November 29, 2015

The first blood transfusion in Africa

Does it matter when the first blood transfusion occurred in Africa? If we are to believe the Serial Passage Theory of HIV emergence, then sometime in the early twentieth century, not one, but as many as a dozen strains of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) passed from West African apes and monkeys to people, although only a handful became epidemic, and only one – HIV-1M – became a global pandemic. Because SIVs have likely infected Africans for hundreds, even thousands of years without become epidemic, the mystery is why in a relatively short time span during early European colonial rule multiple epidemic HIVs emerged in fairly close geographical proximity. Some medical historians and biomedical researchers believe that mass colonial injections campaigns that administered vaccines to tens of thousands of African villagers in rapid succession during and immediately after World War I allowed blood tainted with SIVs to mutate into lethal HIVs. A related theory is that the introduction of blood transfusion therapy in Africa by the end of World War I was the culprit. Blood transfusions allowed large quantities of potentially tainted blood to be passed from one patient to another, facilitating HIV mutation into lethal strains in the ensuing decades. Labor migration, urbanization, and sex work contributed to turn HIV-1M into a continental disease that was later carried to other parts of the world.

New evidence suggests that blood transfusion therapy in Africa might be decades older than previously thought. In 1892 a German military staff doctor in coastal East Africa performed the first known blood transfusion in Africa on a German official on the verge of dying from a disease called blackwater fever, characterized in part by severe anemia. The doctor believed that injecting large quantities of blood would restore lost red blood cells and revive the patient, which it apparently did. What makes the case especially interesting is that the doctor unhesitatingly enlisted an African employee as the donor, and the patient readily agreed – despite the presence of other Europeans who could have supplied blood. The case thus seems to belie expectations of early colonial fears of racial blood mixing. Perhaps this is because this first known blood transfusion in Africa coincided with European breakthroughs in blood serum therapy, which held that people or even animals indigenous to a region were resistant, if not immune, to local diseases. Their blood, and the blood of people who had recovered from a disease, offered possible immunizing agents to vulnerable people, such as Europeans traveling in Africa for the first time. The German doctor may very well have chosen an African to supply blood in the hope that it contained therapeutic properties for blackwater fever, which was believed at the time to be a deadly form of malaria.

Although the first case of blood transfusion in Africa is not likely to have spawned epidemic strains of HIV, it was symptomatic of a medical culture willing to experiment with blood transfusions and injections – not just of human blood, but also of animal blood – for a variety of maladies in the search for life-giving therapies, immunizing agents, or just to determine how mysterious diseases like malaria, dengue fever, sleeping sickness, and yellow fever were transmitted. Diverse people and animals were believed to have had different blood attributes, and this diversity was a strong impetus to medical experimentation. Although modern medical ethicists would shudder at intentionally injecting infected blood into healthy individuals, this is exactly what took place at the turn of the twentieth century in places as far apart as American-occupied Cuba and the Philippines for yellow fever, in Italy, Oklahoma, and Baltimore for malaria, and in Vietnam for typhoid. And in German-controlled Cameroon, where epidemic forms of HIV are likely to have originated, a German doctor after the turn of the century was willing to inject infectious blood from a European suffering from malaria into a healthy person – his own wife – to test malaria transmissibility. She contracted the disease eight days later. Other European and colonial doctors were willing to inject themselves with infectious human and animal blood, and did so as well to colonial subjects who had no say in the matter.

In the past twenty years the timeline for epidemic HIV emergence has been continuously pushed back, from the 1950s to the interwar years. A renewed focus on early blood experiments in Africa and elsewhere, which aimed to uncover modes of transmission and possible immunizing principles of tropical diseases, might help biomedical researchers better understand the origins of epidemic HIV and other diseases.

Image Credit: “Commemorative Red Ribbon White House 2014 World AIDS Day 50174″ by Ted Eytan. CC BY SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The first blood transfusion in Africa appeared first on OUPblog.

What would Mark Twain make of Donald Trump?

The proudly coiffed and teased hair, the desire to make a splash, the lust after wealth, the racist remarks: Donald Trump? Or Mark Twain?

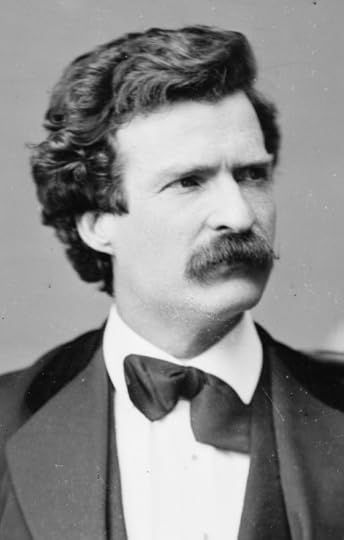

Mark Twain photo portrait, 1871 by Mathew Brady from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Mark Twain photo portrait, 1871 by Mathew Brady from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Tomorrow marks Mark Twain’s 180th birthday; he was born on 30 November 1835, and died on 21 April 1910. He is often celebrated as a great democrat, who stood up for the rights of racial minorities, whose novel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) is about a white boy learning to appreciate and live with a runaway slave. Twain attacked everyone, from the super-wealthy, to European kings who pursued brutal colonial policies, to over-charging cabmen. Alongside this Twain, there was the one who made quite a few racist comments over the years, who dreamt of and schemed for wealth, and loved the company of the kings and millionaires. He knew himself to be an egotist with a desire to show off. He knew himself to be divided, unable to live up to the values that he believed to be right and American.

Mr Donald Trump New Hampshire Town Hall on August 19th, 2015 at Pinkerton Academy in Derry, NH by Michael Vadon. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Mr Donald Trump New Hampshire Town Hall on August 19th, 2015 at Pinkerton Academy in Derry, NH by Michael Vadon. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.I am not Mark Twain’s chosen representative on earth, and I cannot say what he would have made of Donald Trump. I suspect the two would have enjoyed each other’s company for a time – men of the world, both fascinated by and determined to achieve success. But would Twain have seen in Trump the traits he disliked in himself? Further, would he have seen a fulfilment of his fears for the nation? Twain was worried that the United States was becoming a plutocracy, in which political power was controlled by money interests. He was appalled by the predatory techniques of the business leaders of his own day, and appalled by their – to use a 1930s term – “approval ratings” among ordinary citizens. He declared in 1907 that the “political and commercial morals of the United States are not merely food for laughter, they are an entire banquet,” and he lamented that the people “worship money and the possessors of it.” Trump, of course, approaches this in a different spirit: he reminds us, repeatedly, that he is very rich, and that this is a chief recommendation of his candidacy for the presidency. According to him, this means that he knows how to run things, and he cannot be bought off.

In watching Trump, however, another figure springs to mind. Twain disapproved of Teddy Roosevelt, because Roosevelt was “always showing off” and “always looking for a chance to show off.” Twain thought that in Roosevelt’s “frenzied imagination the Great Republic is a vast Barnum circus with him for a clown and the whole world for the audience.” Twain likened Roosevelt to his own fictional character, Tom Sawyer, who would be kind, loyal, treacherous, and equivocating by turns, and always with the aim of drawing attention to himself.

With Trump’s comments on “Mexican rapists,” his unsaying of the same comments, and his boast that he employs “so many Latinos”; with his rejection of gay marriage while claiming to think gays are “great”; his asserting common ground with ordinary Americans, while distinguishing himself from them with references to his personal fortune – is this the same Sawyer-ish, abusive-yet-needy behaviour? Would Twain have seen in Trump the same “irresponsibility” that he saw in Roosevelt?

Finally, both men’s famous hair. Twain double-washed and dried his obsessively so as to get the perfect buoyant, white aureole. He described the process at length in his autobiography. Trump’s hair, most experts to have ventured an opinion agree, is his own, though doubt has been expressed as to whether it is, these days, a natural colour. Perhaps one day Trump too will go on record, and tell us how he produces the endless-forelock/comb-over, as mesmerising as a Penrose staircase.

Featured image credit: American Flag by Unsplash. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What would Mark Twain make of Donald Trump? appeared first on OUPblog.

The European Union: too much democracy, too little, or both?

In a symbolic gesture toward creating an ever closer Union, the European Union conferred citizenship on everyone who was also a subject of one of its member states. However, the rights of European citizens are more like those of subjects of the pre-1914 Germain Kaiser than of a 21st century European democracy. Citizens have the right to vote for members of the European Parliament (EP) but this does not make the EU’s governors accountable as is the case in a normal parliamentary democracy. The result is a democratic deficit.

The votes that European citizens cast in their national constituency are not counted on the basis of one person, one vote, one value. Instead, EP seats are allocated nationally by a system of disproportional representation. Of the EU’s 28 member states, 22 have their citizens over-represented in the European Parliament. A British, French, German or Spanish MEP represents more than ten times as many citizens as an MEP from Malta or Luxembourg.

The rationale for treating citizens so unequally is simple: the EU is a mixture of a few very populous states and many small states. In federal political systems the problem of representing people and states is resolved by having a two-chamber assembly, one consisting of equal electorates and the other having an equal number of representatives for territories unequal in population. MEPs are elected by a compromise system that is much more unequal than that of the US House of Representatives but far more representative than the US Senate.

The European Parliament in Strasbourg by Grzegorz Jereczek. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

The European Parliament in Strasbourg by Grzegorz Jereczek. CC BY-SA 2.0 via FlickrOnce elected, the 751 MEPs do not vote as a national bloc but are divided among eight multi-national Party Groups endorsing trans-national socialist, conservative, liberal, green, nationalist or convenience principles. A Group can have more than three dozen parties from more than two dozen countries. The typical MEP represents a national party that returns only two MEPs. The result is that most MEPs spend their working week conducting politics in a foreign language with foreigners.

Over the years the European Parliament has gained the right to hold the European Council accountable for some though not all of its decisions. This is not democratic accountability but part of a system of elite checks and balances like that of the undemocratically elected British Parliament enjoyed in Queen Victoria’s time.

The European Council collectively makes decisions binding on all of Europe’s citizens. It consists of the heads of the national governments of the EU’s member states. While each is democratically elected, the median national government is endorsed by less than half its voters. British governments represent little more than one-third of Britain’s voters. Angela Merkel heads a coalition government that received the vote of two-thirds of Germans. However, her own party is a coalition and the response of nominal supporters to her refugee policy is a reminder that democratically elected leaders ignore voters at their peril.

The European Union has a democratic surplus since at least seven governments in the Council are up for national election each year. The expansion of the EU’s powers means that European integration can no longer proceed by stealth. Decisions taken in Brussels are increasingly visible in national politics. People who are dissatisfied with Eurozone economic policies or the free movement of peoples across national borders do not need to wait for the 2019 European Parliament election to voice their dissatisfaction. Instead, they can protest by voting in a national election to replace the government that has not been representing their views in the European Council.

Caught by conflicting national and EU pressures, a prime minister can introduce even more democracy, a national referendum on an EU issue. Greek voters have not been able to annul the terms imposed on the country as a result of its national fiscal difficulties. However, the Greek government has yet to fulfil EU conditions fully and may never do so. David Cameron’s willingness to put the UK’s membership in the EU at risk in order to pacify a group of his euro-sceptic MPs is another example of the priority that national leaders are giving to their national electorate.

Votes count but resources decide. No quantity of national votes will enable a national government to stop the world and turn a country into a self-sufficient island. The peace and rising living standards enjoyed by Europeans for more than half a century has been accompanied by an increase in economic, cultural and security interdependence across national borders. However, this does not mean an end of politics, that is, the articulation and reconciliation of different views about what government ought to do. Instead, it adds a new set of institutions and participants to debates about decisions that were once the preserve of national democracies.

Feature image credit: EU Flagga by MPD01605. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr

The post The European Union: too much democracy, too little, or both? appeared first on OUPblog.

This blasted heath – Justin Kurzel’s new Macbeth

How many children had Lady Macbeth? The great Shakespearean critic L. C. Knights asked this question in 1933, as part of an essay intended to put paid to scholarship that treated Shakespeare’s characters as real, living people, and not as fictional beings completely dependent upon, and bounded by, the creative works of which they were a part. “The only profitable approach to Shakespeare is a consideration of his plays as dramatic poems, of his use of language to obtain a total complex emotional response,” he wrote. Head-counting in Dunsinane was merely a distraction from the language of the play, which Knights might well have called ‘the thing itself’.

And yet, the question has often proven irresistible in performances of Macbeth, despite Knights’s now (in)famous denunciation. Indeed, in the opening scene of Justin Kurzel’s sumptuous new film version of Shakespeare’s bloody tragedy, we learn that its answer to Knights’s question is at least one. No words are spoken, but beneath a slate blue, striated sky, a toddler’s funeral is taking place. The grieving Macbeths, played by the magnetically charismatic Michael Fassbender and Marion Cotillard, each approach the body, taking turns to gently balance a posy on the child’s still hands, and then cover his tiny eyes with coloured stones. Their kinsmen silently watch on, each swaddled in blankets, like them, against the brutal Highland winds, before eventually lighting the funeral pyre.

Were he here today, Knights might well have taken such a choice as a painfully literal take on the marital strife that later pushes the Macbeths’ relationship to breaking point, but the truth is that the spectre of child loss has long haunted interpretations of the play. Lady Macbeth’s fierce avowal in the first act that she has “given suck, and know[s] / How tender ’tis to love the babe that milks” her has repeatedly led readers, directors, actors, and audiences to wonder what has happened to this child – a question made all the more relevant by Macbeth’s anxious lines about dynasty and inheritance in Act 3. He might have seized the throne, but he still holds “a barren sceptre” and wears “a fruitless crown”.

In Shakespeare’s own lifetime, child mortality was harrowingly common. At the worst of times, as many as one in three babies died in early modern England before their first year, with many more falling victims to illness throughout their childhood years. By the time he wrote Macbeth, Shakespeare himself had felt the grief of child loss; his young son Hamnet had taken ill in 1596 at the age of eleven, and by August of that year he had died.

Shakespeare didn’t leave any writings that reflected directly on the death of his son – in fact, he didn’t leave any writings that reflected directly on any aspects of his life – but he did represent the world-shattering pain of losing a child in his history play, King John, which he wrote that same year. Here, the bereft Constance refuses to stifle her sorrow for her son Arthur, who has been taken from her and will eventually be killed. Her furious grief becomes the one comfort and companion she can count on in her life: it “fills the room up of [her] absent child,” “puts on his pretty looks,” and “stuffs out his vacant garments with his form.” Even when he is gone, it keeps his memory alive.

In Kurzel’s film, grief likewise proves a potent, world-altering force, conjuring visions in its protagonists’ minds and cloaking the bleak, moody landscape with a heavy loneliness. This landscape itself becomes a powerful character in Kurzel’s version of the play, and the winds and fogs circling around it literally atmospheric. Like the great auteur Akira Kurosawa, who carefully selected the ‘fog-bound’, ‘stunted’ slopes of Mount Fuji as the filming location for Throne of Blood, his Japanese-language adaptation of Macbeth, Kurzel turns the physical world – in this case, the steely Scottish Hebrides – into a central piece of the storytelling.

Aided by cinematographer Adam Arkapaw, best known for his work on True Detective and its malevolent, Louisiana skies, the “blasted heath” of this Macbeth is something brutal and beautiful, awful and awesome. Though the film is set in a feudal, medieval Scotland, visually and emotionally it owes most to the Western. Loss, pain, and emptiness are its hallmarks, death its constant refrain. We know at the start that it shows us a world hostile to young life, and we know by the end that it stamps out the older generations too.

Featured image credit: Black Cuillin By Graham Lewis. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post This blasted heath – Justin Kurzel’s new Macbeth appeared first on OUPblog.

A world with persons but without guns or the death penalty

Over the last year, like many other people in the USA and the rest of the world, I was appalled by the riots in Ferguson and Baltimore, by the Charleston Church shooting, by the death sentence in the Boston Marathon bomber case, and also by the opinion, expressed by the Governor of South Carolina, that the morally right response to the Charleston Church shooting is the death penalty for the killer.

In a recent OUP blog post, “A world with persons but without borders,” I argued that contemporary Kantian philosophy can provide a new, simple, step-by-step solution to the global refugee crisis.

In this post, starting again with a few highly-plausible Kantian metaphysical, moral, and political premises, I want to present two new, simple, step-by-step arguments which prove decisively that the ownership and use of firearms (aka guns) and capital punishment (aka the death penalty) are both rationally unjustified and immoral.

Then, creating a world without guns or the death penalty is up to us.

That Immanuel Kant himself was a defender of the death penalty is irrelevant to my argument: he was simply mistaken about that. But the recognition of Kant’s mistake, in turn, nicely reinforces the point that by “contemporary Kantian philosophy” I mean contemporary, analytically-rigorous philosophy that’s been significantly, although not uncritically or slavishly, inspired by Kant’s eighteenth-century philosophical writings.

All human persons, aka people, are (i) absolutely intrinsically, non-denumerably infinitely valuable, beyond all possible economics, which means they have dignity, and (ii) autonomous rational animals, which means they can act freely for good reasons, and above all they are (iii) morally obligated to respect each other and to be actively concerned for each other’s well-being and happiness, aka kindness, as well as their own well-being and happiness.

Therefore, it is rationally unjustified and immoral to undermine or violate people’s dignity, under any circumstances.

People have dignity as an innate endowment of their rational humanity. Dignity is neither a politically-created right, nor an achievement of any sort. Nor can anyone lose their dignity by thinking, choosing, or acting in a very morally or legally bad way.

The primary function of guns is for their owners or users to manipulate, threaten, or kill other people for reasons of their own, aka coercion, whether this happens arbitrarily or non-arbitrarily.

Notice that I said that the primary function of guns is coercion. Please don’t let the fact that guns can have secondary or tertiary functions, say, for hunting non-human animals, or for recreational shooting, or for holding doors closed on windy days, conceptually confuse you.

United States Constitution by Constitutional Convention. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

United States Constitution by Constitutional Convention. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Notice too, that if it turns out that owning and using guns according to their primary function is rationally unjustified and immoral, then owning and using guns according to their secondary and tertiary functions will be equally rationally unjustified and immoral. If it’s rationally unjustified and immoral for you to own or use a bomb that would blow up the Earth, then it’s equally rationally unjustified and immoral for you to own or use that bomb for hunting non-human animals, for recreational bombing, or for holding doors closed on windy days.

Now arbitrarily coercing other people is rationally unjustified and immoral because it undermines and violates their dignity.

Notice that I said arbitrarily coercing other people. That means manipulating, threatening, or killing other people either (i) for no good reason or (ii) for no reason at all, much less a good reason. Please don’t let the fact that in some circumstances non-arbitrary coercion might be rationally justified and morally permissible, conceptually confuse you.

Therefore, since it fully permits arbitrary coercion, owning or using guns is rationally unjustified and immoral, other things being equal.

Notice, again, that I said other things being equal. Please don’t let the fact that under some special “crisis” conditions, when other things are not equal, when all else has failed, and when the only way to stop someone doing something horrendously immoral (e.g. rape, torture, murder, mass murder, genocide) to you, to someone else, or to many other people, is to use a gun to manipulate, threaten, or kill that evil person, might be rationally justified, conceptually confuse you.

One very important moral and political consequence of the preceding argument is its direct bearing on the Second Amendment to the US Constitution, which says this:

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

In other words, focusing on the material in italics, the Second Amendment says that “the people,” i.e. all Americans, have the moral and political right “to keep and bear arms,” i.e. the moral and political right to own and use guns, unconditionally. The further question of whether the original intention of the Second Amendment was to establish a political right to own and use guns for militias only, or for all Americans, is irrelevant.

Therefore the Second Amendment is rationally unjustified and immoral. More generally, no one, which includes all Americans, and which especially includes all members of the police and the army, i.e. the militia, has the moral right to own and use guns, other things being equal.

All people have dignity, no matter what they have done, that is, they have dignity no matter what moral sins or legal crimes they have committed, because dignity is an innate endowment.

In order to have dignity, you have to be alive, hence no one can have dignity if they are dead.

Therefore it is rationally unjustified and immoral to kill people intentionally, other things being equal.

The only exceptions here are last-resort cases, in which someone is trying to prevent someone else from doing something horrendously evil—say, rape, torture, murder, mass murder, genocide, etc.—to oneself or someone else, or someone is trying to prevent something (like a runaway trolley) from killing many people, and the only way to stop them or it is to kill some people. And even here, only minimal preventive lethal force is morally permitted, because only this is consistent with people’s dignity.

If it’s rationally unjustified and immoral for ordinary people to do X, then it’s rationally unjustified and immoral for the state to do X.

Now the death penalty is when the state legally kills someone in order to punish them, and no case of the death penalty is ever a last-resort case.

Therefore the death penalty is always rationally unjustified and immoral.

Now, let us imagine a world without guns or the death penalty, change our lives accordingly, and then change the world too.

Featured image credit: ‘World May 3D’, by kcp4911. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post A world with persons but without guns or the death penalty appeared first on OUPblog.

November 28, 2015

Analysing what Shakespeare has to say about gender

Humans are very good at reading from start to finish and collecting lots of information to understand the aggregated story a text tells, but they are very bad at keeping track of the details of language in use across many texts. Computers, in contrast, are very good at this level of detail through counting and more advanced statistical analyses while being very bad at understanding a story told in a text or a collection of text. One such statistical approach, collocational analysis, is a way to compute highly-likely lexical combinations which are likely to appear in a highly salient way and can be used to find patterns (or lack thereof) in a collection of texts such as all of Shakespeare’s plays.

Collocational relationships

Collocational relationships are a statistically predicted measure of whether co-occurrence appears more often than by chance. In any given text or collection of texts, co-occurrence measures the probability of word1 occurring in a text that has word2, divided by the probability of word2 occurring in a text that has word1. The conditional probability will be scored on a scale of 0-1; a score of 0 means that word1 never appears next to word2 and a score of 1 means that word1 always appears next to word2.

While this metric may not necessarily be truly indicative of Shakespeare’s use of language, it can certainly make suggestions about how, for example, Shakespeare discusses men and women in a variety of contexts in his plays. Gendered nouns, in particular, provide a set of convenient binaries for a range of registers, such asman/woman (unmarked), lord/lady (higher in register) knave/wench (lower in register). These terms are all generally understood to be semantic equivalents in the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Using one method of computing collocational relationships included in the Wordhoard software package for Shakespeare’s plays, you can see which words only appear with one from each binary (lord/lady etc.), and how likely you are to encounter them.

The Dice Coefficient Test

One test, the Dice Coefficient test (see the Wordhoard Help Files describing collocational analysis), triangulates nicely with three other included statistical tests in the software package. Because multiple collocational measures show very similar results to the Dice Coefficient Test, one can infer that this is quite unlikely to be an artifact of the statistical measurement used. As a result, the collocation relationships described below suggest ways in which Shakespeare uses gendered nouns, but cannot be considered absolute and conclusive facts about his use of them.

Comparisons across each binary pair are therefore possible: man compared to woman, lord compared to lady, and knave compared to wench, and if a collocate is found for man but not woman, it is considered unique. But comparisons across formality by gender are also possible: one can compare unique collocates for woman when compared to those for lady and those for wench. Table 1 explores unique collocations for each binary pair and across register.

As we can see, woman is associated with largely negative adjectives whereas the adjectives associated with lady are all highly complimentary and overwhelmingly positive. Moreover, these negative collocates for woman are predominantly native to English: ‘fat’, ‘foolish’, ‘mad’, ‘waxen’, and ‘weak’, whereas the positive collocates for higher-register lady are all Latinate in root, with examples such as ‘sovereign’, ‘beauteous’, ‘virtuous’, and ‘honourable’. In contrast, man is found alongside largely positive terms (‘good’, ‘proper’ ‘young’, ‘honourable’) or part of recognizable phrases (‘no man’, ‘poor men’, ‘dead man’). Meanwhile, lord’s unique collocates includes highly-frequent function words (including ‘my’, ‘of’, ‘what’, ‘if’, ‘and’, ‘you’, ‘will’) which serve as the building blocks of most language, alongside two more recognizable phrases: ‘lord cardinal’ and ‘dear lord’.

There are very few examples listed for wench, not because there is a huge overlap between wench and knave but because these are the only unique collocations available. Meanwhile, the words used to describe knave are overwhelmingly negative adjectives (‘lousy’, ‘cuckoldy’, ‘lazy’, ‘rascally’) and are easily recognized as ways to build rather recognizable phrases about knaves. Meanwhile, the example of ‘kitchen wench’, a particularly misogynistic phrase, appears only twice in the corpus: once in Comedy of Errors and once in Romeo & Juliet.

Lexical realizations in Shakespeare’s corpus

Although each pair of binary search terms can be considered semantic equivalents, they have quite different lexical realizations in Shakespeare’s corpus. The high Latinate phrasing suggested through collocates for lady is unavailable to the lower status woman and wench through the same methodology. Lord is the only noun investigated which has a strong relationship with very common words in any English text. Meanwhile, man and knave show very stratified descriptions of men across register: man is more likely to describe qualities of men, whereas knave is more likely to be supplementary with regards to low-status individual in question. This practice suggests that social class is stratified at the level of socio-pragmatic lexical relationships in ways which are not visible to linear readers of Shakespeare’s plays, quite contrary to what a reader of Shakespeare’s plays may expect.

A version of this blog post originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Ophelia” by John William Waterhouse. Public Domain via WikiArt.

The post Analysing what Shakespeare has to say about gender appeared first on OUPblog.

Women onstage and offstage in Elizabethan England

Though a Queen ruled England, gender equality certainly wasn’t found in Elizabethan society. Everything from dress to employment followed strict gender roles, and yet there was a certain amount of room for play. There are several cases of (in)famous women who dressed as men and crossed the bounds of “acceptable behavior.” Women constitute an integral part of many of Shakespeare’s plays and poems, yet there are massive gaps between the amount of lines, speeches, and even character roles for men and women. Strong-willed and powerful male characters easily outnumber their female counterparts, and it was men who performed those female roles. Such characterizations would become increasingly complicated as male actors portrayed female characters who, in the play, were disguised as men (the “female page” role). Such contrasting rigidity and fluidity in society and on stage reveal a complex understanding of gender and what it means to be a woman.

Download the infographic as a PDF or JPG.

Featured Image: “Sir Toby Belch coming to the assistance of Sir Andrew Aguecheek” (Twelfth Night) by Arthur Boyd Houghton. Folger Shakespeare Library. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Women onstage and offstage in Elizabethan England appeared first on OUPblog.

The life of culture

Sometimes culture seems to have a life of its own. You catch wind of a juicy bit of gossip and just have to tell your friends. You hear a pop song a few times and suddenly find yourself humming the tune. You unthinkingly adopt the vocabulary and turns of phrase of your circle of friends. The latest fashions compel you to fork over your money, succumbing to what is de rigueur.

But does culture really have a life of its own? Are cultural trends, fashions, ideas, and norms like organisms, evolving and weaving our minds and bodies into an ecological web? Some have answered a resolute yes. The biologist Richard Dawkins, for example, is a strong proponent of this idea and he introduced a term — meme — to name these cultural beasts. In popular parlance, memes now mainly refer to things gone viral on the Internet — think Grumpy Cat or What Does the Fox Say? — not the totality of culture. But could it be that culture is composed entirely of memes and that, like viruses, they are adapted to enter our body and coerce it to make copies before finding a new host to parasitize?

To answer this question, we need to consider whether phrases like “the evolution of culture” can be understood to be more than mere metaphor. Does it make sense to apply Darwinian evolutionary theory to culture? From a distance, it seems obvious that in culture there is variation (multiple variants of cultural traditions), heritability (culture is transmitted from generation to generation), and fitness differences (some cultural variants tend to fare better than others). And because heritable variation in fitness is the cornerstone of Darwinism, we should be free to use the Darwinian framework, as well as the specific models developed in contemporary evolutionary biology, to make sense of cultural dynamics. This straightforward view, however, has received considerable criticism. One critique holds that cultures are composed not of discrete chunks like organisms; they are less like mosaics and more like paintings made of countless, continuous shades of color. And if culture is not made of discrete chunks, how can we conceptualize the success (fitness) of cultural elements?

Image by Grant Ramsey. Used with permission.

Image by Grant Ramsey. Used with permission.The chief concern of our article is to examine these questions. The fitness of an entity is based on its ability to survive and reproduce. When the entity in question is an organism, things are relatively simple: We can usually readily distinguish one organism from another, and we know what it is for them to live, reproduce, and die. But what is it for a cultural unit to live or die? Like zombies rising from corpses presumed long dead, cultural variants can be lost in books or film, only to recrudesce upon rediscovery. And what counts as reproduction? If I get a pop song stuck in my head, has the song reproduced? If I am recorded humming the song, should this count as reproduction?

The problem of cultural fitness can be made much more tractable. One of the major problems with an evolutionary account of culture is trying to individuate and count cultural units. We propose a way to borrow the relative ease of counting organisms and tie this to cultural units. Instead of thinking of culture as disembodied memes, we propose taking an organism-centered approach. Each human can possess or fail to possess a cultural variant, and the only way for this variant to be passed on is for another person to adopt the variant. Cultural variants are thus counted only once per person, relieving us of having to worry about individuating multiple copies of memes inside our notebooks or closet.

This idea of counting traits only once per organism is typical of evolutionary biology. To see how a biologist might study the evolution of plant varieties, consider a species with two variants, one with all white flowers and the other with all purple flowers. If the goal of the study is to say whether there has been evolution in flower color taking place, the biologist counts the number of plants with white flowers and the number of plants with purple flowers; she does not merely count disembodied flowers, since this would be to mistake growth (making more flowers on a plant) with evolution (making more plants of a particular variety). For the same reasons, cultural evolution should be based on counts of humans with cultural variants, not copies of disembodied variants. Taking this view also has the advantage that culture need not always come in isolated packages. Just as humans can have discrete, countable traits (having two arms), they can also have continuously variable (what biologists call quantitative) traits like height.

Although the organism-centered framework offered here does not solve all the problems of applying a Darwinian evolutionary framework to cultural systems, it goes some way toward breaking down the barrier to allow the light of evolution to shine on cultural phenomena.

Featured image credit: Human evolution silhouettes, by Vector Open Stock. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The life of culture appeared first on OUPblog.

November 27, 2015

Oral history and childhood memories

During my second semester at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I took an oral history seminar with Dr. Jacquelyn Dowd Hall. It was an eye-opening experience, not only because of what I learned, but how I learned. We had to conduct two interviews, and after spending nearly two months of class time discussing the historiography and methodology of oral history, I thought I was ready to go. My first interview was with civil rights activist Wyatt Tee Walker, and although he agreed to be interviewed, he was not feeling well and had difficulty speaking. Thrown off, my first few questions were poorly constructed, and I sped through his early life hoping he would have more to say about his activist history later in life. Listen as I struggle:

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/OHRInterview_WyattTeeWalker.mp3

I lost an opportunity during that interview. I could have discovered more about Wyatt Tee Walker based on his early life, but I zoomed ahead. Now, every time I give a workshop on oral history, I hammer home the same message: start with their childhood. What surprises me are the responses from students, who often look incredulous when I tell them. They may think stories about growing up have nothing to do with their project at hand, and they don’t want to waste time talking about childhood memories. They want to cut to the chase and focus on big events later in life. But by leading off your oral history with several questions about what it was like growing up, you will build the foundation for a better interview.

Let’s say you’re interviewing someone for a larger project about an environmental history of Orange County, North Carolina. The long-time director of a local community organization has agreed to talk to you, and from your research, you know this person will have a lot to say about environmentalism in North Carolina over the past twenty years or so. You arrive to interview the person, you chat and get comfortable with one another, and you begin the interview. You may be tempted to launch right in: “Tell me about how you first came to work with ABC Environmental Group…” or “Tell me about how you first became interested in environmentalism.” Resist the temptation, and begin much, much earlier.

Start by asking your interviewee about their childhood. Introduce yourself, the interviewee, mention the date and any other relevant background information, and then ask your first question: “Tell me about your childhood.” Based on how they respond, they will give you the working materials to ask follow-up questions that will give the interview much more substance. Ask about where they grew up, their neighborhood, their family, their education, their religious background, and so on. Ask about individuals in their family: “Tell me about your father/mother/siblings/grandparents or anyone else influential as you were growing up.” (Hint: many people love talking about their grandparents if they knew them well.)

Hopefully by now you’ve forgotten how I opened my interview with Wyatt Tee Walker. Now, consider this example when I interviewed Evelyn Poole-Kober, a local Republican activist in Chapel Hill. How did that one, single question differ from the many incoherent questions I launched at Walker?

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/audio/OHRInterview_poole-kober.mp3

Here’s what happened next. Poole-Kober shared stories about her childhood and adolescence for about a third of the total interview, around 45 minutes. Should I consider these stories wasteful because they weren’t directly related to my project at hand? I don’t think so. She opened up, shared intimate details of her life, and led me through her early life to show where she ended up. These memories enhanced the total value of the interview, and they opened the door to more questions, more stories, and a richer interview about her whole life.

Concentrating on childhood questions also helps oral historians move toward curating oral histories rather than just collecting them. As Linda Shopes suggested in a previous blog post, quality and originality should be stressed over quantity when conducting an oral history project. By focusing the beginning of every interview on childhood, no matter the project, you will generate an unpredictable set of stories and information that researchers working on vastly different projects might one day find useful. Curated in a way that crosses projects, time periods, and disciplines, these stories enliven the field of oral history by rooting the past of each person in vivid ways.

Every oral history interview and project is different. You may not have the time, or you might be unable to dedicate an extended period of time to every person’s childhood and adolescence. But if you can, I suggest that you do. The rewards can be great.

Image Credit: “Childhood Pictures” by martinak15. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Oral history and childhood memories appeared first on OUPblog.

Mitochondria donation: an uncertain future?

Earlier this year, UK Parliament voted to change the law to support new and controversial in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) procedures known as ‘mitochondrial donation’. The result is that the UK is at the cutting-edge of mitochondrial science and the only country in the world to legalise germ-line technologies. The regulations came into force on 29th October this year, and clinics are now able to apply for a licence.

The process involves using part of a donated egg which contains healthy mitochondria to power the cells, and would allow women with mitochondrial disease to have healthy, genetically related children. This is so controversial because mitochondria contain genetic material, which means that the mitochondria donor would be contributing to the genetic make-up of the child and importantly, to the genetic make-up of their future children. As a germ-line technology, which does or does not involve genetic modification (depending on which definition of genetic modification you use), it is not surprising that ideas of Frankenstein science and ‘slippery slopes’ to designer babies have dominated the headlines. As there is no cure and treatment is limited, the possibility of preventing a child from inheriting the disease has been widely welcomed. But the techniques have also attracted criticism from groups concerned about embryo research and those who believe there are safer alternatives.

The change in law was preceded by an intense period of debate and enquiry, where safety was, and remains, a key question. The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), who regulates assisted reproduction and research within the UK, convened an expert panel to conduct three scientific reviews. They found that the techniques were ‘not unsafe’ which proved an adequate basis for the government to change the law. However, this is not the end of the regulatory process. Although the techniques are legalised and clinics can now apply for a licence, the HFEA is not expecting to receive any applications until all safety tests recommended by the expert panel have been carried out and published, and then each case will be considered on an individual basis.

Questions also remain about the future health of the children. The UK Department of Health recommended engaging them in long term follow up. But this raises considerable ethical issues about genetic testing of children and their potential to be medicalised from an early age. It also raises the practical questions: will parents readily agree, and would incentives need to be offered to secure their involvement?

Another important question concerns the role of the mitochondria donor. One of the defining characteristics of technologies involving donation is the potential to produce new social relationships, but what about mitochondria donation? For some, mitochondrial donation appears similar to egg or sperm donation which suggests a genetic (parental) relationship between child and donor. For those who feel that the genetic contribution is minor because of the small number or limited role of the genes involved, mitochondria donation is considered more like tissue or organ donation. Here, the UK government has made some important decisions and the debate has to some extent been settled. Although the mitochondria donor is not to be considered as a ‘parent’ and has no legal obligation towards the child, there is recognition that the child might like to know something about the donor. The child will be able to access non-identifying information such as screening tests, family health, and personal information provided by the donor.

One of the key assumptions on which access to donor information is based (and this also relates to assumptions about families’ willingness to agree to follow up) is that the child will know about mitochondria donation. In the case of sperm donation and adoption, individuals are now able now to access information about their parentage, but accessing this information relies very much on open disclosure practices of families. One of the enduring factors about family life is that many children born through assisted reproduction and those who are adopted are not told of the origins of their birth. Disclosure is not always inevitable, and there are decisions to be made about how to tell (should it be blurted out or drip fed?), who should tell, and when is the right time to tell. We also know that telling a child potentially sensitive information will probably mean that everyone else in their social (and online) world will also know.

The ultimate test for proving whether any novel IVF techniques work, and knowing what the implications are, is through human application. This means there will be a lot of interest in the first cohort of babies born through the technique. But whether families will agree to additional and sustained contact with the clinic, disclose information to their child, and whether they will recognise the donor within their lives, are currently unknowns. We also know very little about how or whether women with mitochondrial disease will choose to use these technologies. How families proceed from here will determine how and whether mitochondrial donation becomes a significant technology of the future.

Featured image credit: “9-Week Human Embryo from Ectopic Pregnancy” by Ed Uthman. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Mitochondria donation: an uncertain future? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers