Oxford University Press's Blog, page 592

November 9, 2015

The future of scholarly publishing

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Today, our Editorial Director for OUP’s Academic and Trade publishing in the UK reviews trends in the field.

In thinking about the future of scholarly publishing – a topic almost as much discussed as the perennially popular ‘death of the academic monograph’ – I found a number of themes jostling for attention, some new, some all-too familiar. What are the challenges and implications of open access? How do we make our content relevant to a truly global audience? What is the right response to the shifting market, the decline of the library budget? How might we shift our position along the value chain? And whither print?

The advent of digital, market changes, the rise in importance of emerging economies, the decline in library budgets, the move towards open access: these are shifting sands beneath the feet of traditional publishers. But this is nothing new. As Michael Bhaskar points out, in his lively book, The Content Machine: Towards a Theory of Publishing from the Printing Press to the Digital Network, “Publishing, famously, is always in crisis.”

The Internet is a powerful democratising force and the barriers to entry are falling fast, meaning the role of the publisher as gatekeeper needs to change to remain relevant, while continuing to capitalise on brand as a signifier of quality in an era where filtering the sheer volume of content online can prove overwhelming. Digital also makes it possible for us to analyse user data and behaviour, letting us consider the needs of the researcher, the teacher, the student at every stage of the process, and to put the consumer at the heart of what we do for the very first time.

“Scholarly publishers have always served academic constituencies by publishing in what might be called an “intra-tribal” manner—works by scholars in a discipline directed at scholars in the same discipline—but increasingly there will arise a need both to publish inter-tribally (to scholars in other disciplines) and also to serve as a bullhorn for thoughtful, empirical work in an arena of public debate that has become muddled by a rising drone of white noise.”

—Niko Pfund, President of OUP USA

The most significant changes are an evident shift in the market from supply-driven to demand-driven publishing, with libraries adjusting to a difficult budget situation with hybrid models such as evidence-based or user-driven acquisition, which offers more control in the selection of resources and a direct means of matching purchasing decisions to user needs. In short, access is opened to a wide range of digital content, and purchases are ultimately made to reflect the content that sees use during the period.

“The role of the scholarly publisher is changing fundamentally. It will no longer be enough to offer content you can read to aid your research, publishers will need to offer content you have to read. If they don’t do that, they won’t survive. And the quantity of essential content is limited – which has challenging consequences for the number of scholarly publishers.”

—Dominic Byatt, Publisher & Senior Commissioning Editor, Politics

A number of broad trends characterise the industry at present. At one end of the spectrum, publishers are shifting their position in the value chain, and redefining themselves as they go, into training and assessment, information systems, networked bibliographic data, and learning services. Presses are also continuing to consolidate, with mergers and strategic acquisitions building scale and shoring up their output. These shifts are echoed in trends around the aggregation of digital content, with multi-publisher books and journals platforms such as Project MUSE, JSTOR, our own University Press Scholarship Online, and CUP’s University Publishing Online.

At the other end are new entrants defining particular niches: dedicated Open Access presses such as the relaunched UCL Press and Goldsmiths Press, looking to digital first to deliver new and unconventional forms of academic publishing. Meanwhile, start-ups queue up to break ground with the latest author tool or new business model. Want to help drive visibility and impact, build your own bibliographical database, take notes online, develop narratives in a new way, crowdfund your project, sponsor the open dissemination of content, increase your amplification, build networked communities or members clubs with bespoke offerings, provide tools for content translation and transmission, for indexing citations and data mining, or self-publish via a range of options, from do-it-yourself to a full suite of outsourced services? There’s an app (or online tool) for that.

What these contrasting shifts – the move to corner the market and the counter move to provide a focused solution to a single process – have at their heart is the response to a lively and exciting time for the industry. Publishers are redefining their traditional roles, unpicking exactly what it means to deliver content to different sets of users, and the activities this enables – literacy, learning, assessment, research, open dissemination, building communities, and many more – and experimenting with the digital technologies that make this possible.

The future is challenging, no doubt. Research funding and library budgets aren’t likely to blossom any time soon, open access solutions will take some time to find their level, the drive to innovate makes false starts and wrong turns ever more likely, and there are challenges in convincing a digital audience growing accustomed to ‘good enough’ of the importance of filtered and authoritative content. But the underlying opportunities are powerful, and go right to the heart of what we are all about: the chance to commission and create meaningful research and educational content and take it to the widest possible global audience, working with our authors and readers in new ways.

Featured image credit: Woman at laptop. CC0 via Pexels.

The post The future of scholarly publishing appeared first on OUPblog.

University Press Week blog tour round-up (Monday)

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Here’s a quick round-up of topics discussed on the University Press Week blog tour, which kicked off yesterday.

For the last few years, the AAUP has organized a University Press blog tour to allow readers to discover the best of university press publishing. On Monday, their theme was “Surprise!” featuring unexpected ideas, information, and behind-the-scenes looks at the presses.

Cookbooks from a university press? University Press of Florida highlights recipes and photos from recent UPF cookbooks that have changed how people view the Sunshine State, highlighting a thriving food scene that has often gone unnoticed amid the state’s highly-publicized beaches and theme parks.

“If I can sell gay marriage, I think I can sell a book.” University Press of New England Marketing Manager Tom Haushalter reflects on the unusual success of Winning Marriage by Marc Solomon, tracing the years-long, state-by-state legal battle for marriage equality in America. Surprises came in many forms: from the serendipitous timing of the book’s publication with the Supreme Court ruling to the book’s ability to resonate with general readers and legal scholars alike—and many others surprises in between.

When a local newspaper, a local bookstore, and a university press run a features page. Steve Yates, marketing director at University Press of Mississippi, describes how the Press has partnered with Lemuria Books in Jackson and writers across the state to create the Mississippi Books page at the Clarion Ledger.

Guess the Press. University Press of Kentucky quizzes you on some surprising facts about university presses, from publishing Pulitzer Prize-winning novels to seventeenth-century bibles.

246 years and 8 months of work. University of Nebraska Press has an excellent infographic about their staff.

The best classical actor in the United States today” writes mysteries for a university press. Mystery fiction is a surprise hit, and a surprisingly good fit, at the University of Wisconsin Press.

Bonus: AAUP has a slideshow of surprising books, series, products, and more from university presses.

Bonus: The University of California Press’s Alison Mudditt speaks with five experts about innovation in scholarly publishing on Scholarly Kitchen.

Be sure to look out for blog posts from Indiana University Press, Oxford University Press, George Mason University Press, University Press of Colorado, University Press of Kansas, UNC Press, West Virginia University Press, Johns Hopkins University Press, Fordham University Press, and University of Georgia Press later today.

Featured image: Colorado. Photo by Thomas Shellberg. CC0 via Unsplash.

The post University Press Week blog tour round-up (Monday) appeared first on OUPblog.

The legacy of the New Atheism

The ten-year anniversary of the publication of Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion is approaching, and it has already been over ten years since Sam Harris published The End of Faith. These two figures, along with the late Christopher Hitchens, are the most important in the anti-religious movement known as the New Atheism. A few years ago, they were a ubiquitous presence on cable news and talk shows, but recently they’ve somewhat faded from the spotlight (a notable exception was Harris’ heated and highly publicized argument with Ben Affleck on Real Time with Bill Maher last year). At the peak of their public visibility, their fans heralded them as representatives of a dawning new age of reason that would finally put an end to superstition and religious ignorance, while their detractors either counter-attacked them as dogmatic evolutionists or dismissed them as yet another ephemeral anti-religious blip on the radar of history.

The ones who dismissed them as insignificant were wrong—and academics who obsessively reject the idea of secularization are some of the worst offenders in this regard. Social science in general has not yet fully appreciated the significance of the New Atheism and has tended not to take it very seriously, with the exception of those working in the new sub-discipline of secularity studies. But whatever one might think of the New Atheists’ ideas, an honest appraisal would recognize that they have had a significant and lasting impact.

The most obvious evidence of this is the growth and increasing visibility of the atheist movement in America. Fashioning themselves as the last frontier of the civil rights movement, atheists have pushed their way into mainstream American culture by adopting a minority identity and mimicking the strategies of the LGBT movement. Their “coming out” and “Good Without God” campaigns encouraged atheists to tell their friends and neighbors about their non-religious identity and show the country that they are good, moral people. To illustrate their outsider status, they have frequently pointed to surveys indicating that most Americans would rather see a Muslim or a homosexual than an atheist as President.

But they aren’t the outsiders they used to be. A 2015 Gallup poll found, for the first time, that a 58% majority of Americans would be willing to vote for an atheist candidate, and “atheist” is no longer at the top of the list of characteristics that would be a deal-breaker for voters (that spot is reserved for the dreaded “socialist”). Revealing the general demographic shift in views about religion, 75% of those in the 18-29 age category said they would vote for an atheist—precisely the same number who said they would consider voting for an evangelical Christian. It appears that atheist activism may be having the desired effect, especially among young people, though this could also simply be related to a more general trend: people moving away from organized religion. The proportion of Americans who claim no religious affiliation has spiked sharply in recent years, growing from 16% in 2007 to 23% in 2015, with the number soaring to 35% among Millennials. While atheists and agnostics constitute a smaller subset of that group, their numbers are also growing.

The New Atheists might not be responsible for all of this (though they may be for some of it), but we can say that they’re a symptom of some significant cultural changes. They should be remembered for catalyzing a movement for religious dissent and inspiring atheists to come together and find a voice in American public life. But there’s a much darker side to the legacy of the New Atheism that stems from its imperialist and xenophobic tendencies, to say nothing of some thinly veiled Social Darwinism and arguments for eugenics. Sam Harris in particular is now known more for supporting the Israeli occupation of Palestine and ethnic profiling at airport security than for his science-based critique of religious faith. Richard Dawkins’ personal legacy has taken a heavy hit in the past few years, as his rambling criticisms of feminism and Muslim “barbarians” on Twitter have led to charges of sexism, racism, and general arrogance and intolerance. On many social and political issues, the New Atheists are on the same page as the Christian Right.

Many young atheists have discovered that the atheist thinkers they admired turned out to have a lot in common with the worst aspects of the religions they railed against. The result is that the movement has lost a good deal of steam, at least in its New Atheist form. Many atheists today want to move beyond bashing religion to emphasizing the more positive and constructive aspects of atheism, but there’s little agreement about what that means exactly. The conservative narrative of western cultural supremacy and science-driven social progress favored by the New Atheists and a growing constituency of right-wing libertarians has come up against a grass-roots movement of younger activists who tie atheism to ideas about equality and social justice. The dominant trend, however, is still the old militant one, which leaves younger atheist who are disillusioned with the old prophets of scientism wondering if this is the right movement for them.

For all of the differences between these groups, there is a general consensus to transition away from the New Atheism’s wildly optimistic goal of converting the world to a scientific worldview, and toward an emphasis on advancing the social standing of atheists and giving them a voice within a diverse cultural landscape. But regardless of their current standing among atheists, the fact is that the New Atheists gave life to a cultural and political movement. Perhaps they were just the trigger on a gun that was already loaded, but that doesn’t make their role any less important.

The New Atheism, ten years on, is not “new” anymore, but its ongoing influence shouldn’t be underestimated. It would be difficult to say that Dawkins, Harris, and Hitchens were causes of a cultural revolution, but they may be a sign of one. The God Delusion should be regarded as one of the most important books of the past decade if only because it’s so rare for a single book or thinker to galvanize so many people to such a degree, to say nothing of its role in mobilizing activism that would establish recognition of a new minority group in American society. This is a major accomplishment, even if religious belief doesn’t vanish any time soon.

Image Credit: “2012/03/06″ by Sach.S. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The legacy of the New Atheism appeared first on OUPblog.

Max Planck: Einstein’s supportive skeptic in 1915

This November marks the 100th anniversary of Albert Einstein completing his masterpiece of general relativity, an idea that would lead, one world war later, to his unprecedented worldwide celebrity. In the run-up to what he called “the most valuable discovery of my life,” he worked within a new sort of academic comfort. And in just ten years, he had moved from the far margins of science to the epicenter of scientific prestige. This position and this move came about in no small part because of his friend Max Planck, twenty-one years his elder.

The major shift in Albert Einstein’s career began in 1905, when he submitted a number of revolutionary papers to the leading physics journal, Annalen der Physik. Max Planck, the lead editor for theoretical work, was among the first to read them. At the time, Einstein, the young patent clerk, was truly an outsider. But Planck recognized the work’s innovative genius, and he green-lit publishing the articles, including two that outlined what we now call the special theory of relativity.

Planck, who took a very broad view of physics (and physical chemistry, philosophy, linguistics, et cetera), was already primed for relativity. In 1898 and 1899, he had exchanged a series of letters with the Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz, trying to reconcile the crazy-making results from speed of light experiments. After some clever but fruitless head scratching, he returned to the work that would soon give the world a quantum breakthrough and a new fundamental constant, h. But Planck now understood that classical physics had a nasty problem when it came to the speed of light as measured by different observers.

So when Planck the journal editor first encountered Einstein’s ideas concerning space, time, and the universal speed of light, he welcomed and helped broadcast the update: An absolutely constant measure of light’s speed had to replace the comforting and quaint notion that our rulers and clocks would never mislead us. He then wrote one the first major follow-ups to Einstein’s 1905 relativity work, demonstrating how the dynamics of bodies could be treated properly in this new, elastic spacetime. Planck then defended Einstein from waves of skeptics, writing to him that they “must stick together.”

Planck would be less encouraging on the road to Einstein’s self-labeled “theory of incomparable beauty,” general relativity. By pushing his original ideas beyond special, limited cases, Einstein flirted with rewriting Newton’s theory of gravitation. As he began this work, Planck shook his head. “As an older friend, I must advise against it,” he wrote in 1913. “In the first place, you won’t succeed, and even if you do, no one will believe you.”

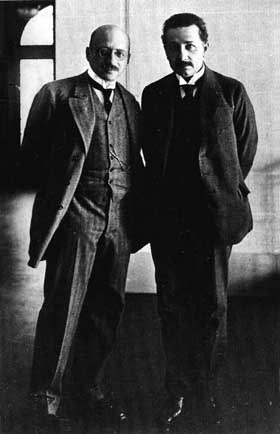

Fritz Haber and Albert Einstein at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut fuer physikalische Chemie und Elektrochemie, Berlin-Dahlem, 1914 by S. Tamaru. Used with permission by Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berlin-Dahlem.

Fritz Haber and Albert Einstein at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut fuer physikalische Chemie und Elektrochemie, Berlin-Dahlem, 1914 by S. Tamaru. Used with permission by Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Berlin-Dahlem.But putting these doubts aside, Planck carefully built an ideal nest for Einstein’s labor. Planck led the charge to create the teaching-free job offer, with record salary, that enticed Einstein to Berlin in 1913. Here, Einstein would spend an incredibly fruitful yet uncomfortable 19 years, spanning the end of the German Empire and the rise of political extremism. Some of his new colleagues wanted Einstein to advance their own fields. The chemist Fritz Haber, for instance, dreamt of a partnership in physical chemistry. Instead, Einstein threw himself into his greatest idea and the difficult mathematical road ahead. Meanwhile, his friendship with Planck grew. He told a colleague that he remained in Berlin because, “to be near Planck is a joy.”

In November of 1915, Einstein completed his theoretical masterpiece. Newton’s falling apple no longer felt the heavy tug of a force; it simply followed the gentle warp and weave of spacetime near our massive planet. But Einstein had not convinced that many colleagues, and major experimental tests would have to wait.

The war years posed challenges for both men, but more so for Planck. He lost his eldest son at Verdun and both of his twin daughters to complications in childbirth. “Planck’s misfortune wrings my heart,” Einstein wrote to a friend. “I could not hold back the tears when I saw him… He was wonderfully courageous and erect, but you could see the grief eating away at him.” The two sometimes played music together in Planck’s home to escape their times and probably to escape talking politics. Planck, the concert-grade pianist, bound himself to his nation and its Kaiser, but Einstein, the casual violinist, leaned strongly to the left.

After the war, dramatic measurements confirmed general relativity by showing Einstein’s predicted deflection of starlight near the sun, a ghostly effect now called gravitational lensing. A war-weary planet cheered the likable genius with front-page headlines and countless invitations. Planck wrote with delight to his friend, changing his ever-flexible mind and calling general relativity an “intimate union between the beautiful, the true and the real.” He signed this letter, “cordial greetings from your devoted servant, M. Planck.”

Their friendship would later be wrecked between Planck’s conflicted patriotism and Einstein’s prescient horror during the rise of the Nazis. The music and the letters ceased. But after Max Planck died in 1947, Einstein, who never set foot in Germany again, wrote a moving tribute to Planck on behalf of America’s National Academy of Sciences. And more privately, he wrote a short note to Planck’s widow, telling her, “The hours that I spent in your home, and the many conversations that I conducted in private with the wonderful man will for the rest of my life belong to my beautiful memories.” In some sense, their concert – including all their tension – plays on, as general relativity and quantum theory stand awkwardly together as two irreconcilable pillars of modern physics.

Featured image credit: Black hole by NASA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Max Planck: Einstein’s supportive skeptic in 1915 appeared first on OUPblog.

Can flour fortification programs reduce anemia?

Two studies published this year yield conflicting results on whether fortifying flour with essential vitamins and minerals improves anemia prevalence. One study published in the British Journal of Nutrition (BJN) showed that each year of flour fortification was associated with a 2.4% decrease in anemia prevalence among non-pregnant women. The second study published in Nutrition Reviews provided little evidence that fortification improved anemia prevalence.

So does fortification affect anemia or not? As an author on both studies, I suggest that the answer depends entirely on the quality of the fortification program.

This is an important question because an estimated 243 million non-pregnant women of child-bearing age, 16 million pregnant women, and 114 million children worldwide suffer from anemia related to iron deficiency, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Prevalence of Anemia in 2011 report. Women who have had iron deficiency anemia say it causes debilitating fatigue. In pregnancy, anemia contributes to 20% of all maternal deaths. In childhood, anemia limits cognitive development.

Currently 83 countries require wheat flour fortification as part of the industrial milling process. Fourteen of these countries also mandate wheat flour fortification . Iron is the most frequently added nutrient, and flour is also commonly fortified with the B vitamins folic acid, riboflavin, and B12. Deficiencies in each of these nutrients can cause anemia. Knowing how effective these fortification programs are is a critical step in recommending ways to improve them.

For the BJN study, we looked at countries that included at least iron, folic acid, vitamin A or vitamin B12 in their fortification programs. Their fortification programs could include wheat flour alone or combined with maize flour. The papers included in this study all included anemia prevalence in non-pregnant women as reported in national surveys, such as the Demographic Health Surveys and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys. Countries were included if they had anemia data from before and after fortification began. Twelve countries that we called “fortification countries” met this criteria. We found 20 countries with at least two national surveys on anemia but no flour fortification program.

Since anemia is affected by many things, we adjusted the findings for the Human Development Index and malaria. In the 12 fortification countries, each year of fortification was associated with a 2.4% decline in anemia prevalence. In comparison, the non-fortification countries had a 0.1% decline in anemia prevalence over time.

The study published in Nutrition Reviews was a systematic review of programs to fortify flour. Only programs to fortify flour with iron were included. We found published and unpublished reports of fortification programs in 13 countries. Each report compared data collected before fortification with data collected at least 12 months after fortification. That review showed that fortification consistently improved women’s iron status, but it provided little evidence that fortification improved anemia prevalence.

This was perplexing. How could two studies conducted practically simultaneously on the same topic produce such different results?

One difference was that all data in the BJN report were from national studies while the Nutrition Reviews paper included both national and sub-national data . Most studies presented data gathered at the subnational level within a selected area of the country; the only national-level data reported were for Fiji and Uzbekistan. The major difference, however, was noted by Richard Hurrell, Professor Emeritus for Human Nutrition, ETH Zurich. He was not involved in writing either paper, but he made an important observation in a letter to the editor of the British Journal of Nutrition. Most of the 12 fortification countries in the BJN study had national programs that used iron compounds recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).

In contrast, most of the studies in the systematic review did not use the WHO-recommended iron compound and did not add the minimum recommended iron level. Most of these reports showed no decline in anemia prevalence with flour fortification. In addition, the programs in the Nutrition Reviews paper reflected a wide variety of compliance with the fortification standard and the percent of population covered by fortified products.

Fortification programs cannot be expected to have a significant health impact if the iron compounds are not bioavailable , meaning if they are not easily absorbed by the human body. Also, programs will not have the expected impact if insufficient iron amounts are used, if the program is not well-monitored, or if a high proportion of the population does not consume fortified foods.

On the other hand, well-planned, fully implemented and carefully monitored programs to fortify flour with the recommended level of essential vitamins and minerals will reduce the risk of anemia from nutritional deficiencies over time.

Featured image: “Flour” by Melissa Wiese, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Can flour fortification programs reduce anemia? appeared first on OUPblog.

How do you decide who ‘qualifies’ as a citizen?

Citizenship tests are meant to focus on facts essential to citizenship, yet reviewing them tells a different story. What knowledge makes one a good citizen?

What Subjects Should be Included?

Citizenship tests are a sort of a “grab bag”; they include a little bit of everything—demography, geography, history, constitutional principles, national holidays, and a long list of practical knowledge of education, employment, healthcare, housing, taxes, and everyday needs. The United States asks about rivers, oceans, and the flag; Australia tests about Kangaroos, the national flower, and mateship; Germany include questions about Pentecost, Rose Monday carnival, and the tradition of Painting Eggs on Easter; Holland focuses on nudity, the importance of bringing a present to a birthday party, and the custom of handshaking in a job interview; France asks about Brigitte Bardot, Edith Piaf, and Molière; Britain includes Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, cricket, and Harry Potter; Spain tests about Picasso, folk dances, and the Camp Nou; and Denmark includes questions about the children’s story, The Ugly Duckling, and the film The Olsen Gang.

Test content is changeable. The current trend in is toward cognitive tests, but just a few years ago one could see other type of questions about social interaction and moral judgment. The British Citizenship test used to ask questions such as: “Suppose you spill someone’s pint in the pub. What usually happens next?” The German Land of Baden-Württemberg asked: “Imagine that your adult son comes to you and declares that he is a homosexual and would like to live with another man. How would you react?” This type of questions no longer exists, due to public criticism, but one may still find some relics of similar questions, such as the German question: “What should parents of a 22-year-old daughter do if they do not like her boyfriend?”

What Should be the Test Format?

One option is a knowledge test, a second option is a behavior test, and a third option is a residency test. While a knowledge test presumes that a person knows and understands a society’s history and culture by answering some questions, a performance test assesses a person’s behavior to determine whether she is a good citizen. For example, it can consider whether the immigrant pays taxes, volunteers in the community, abides the law, and takes part in public life. A residency test presumes “good citizenship” merely through continual residency. According to this test, a person living continuously in the society is presumed to become a good citizen. The test is whether a person lives enough time in the society.

Is the Test Essential for Citizenship?

Citizenship tests are supposed to focus on knowledge essential to citizenship. And yet, reviewing citizenship tests shows that everything goes. Does knowledge about horse races, haggis, the Beatles, and British soap operas make one a good Brit? The previous test included the question “according to Life in the UK, where does Father Christmas come from?” Possible answers were Lapland, Iceland, and the North Pole. The answer to this question, which is more about mythology than history, is controversial. Some people might answer Lapland, while others might say the North Pole. Various societies tell different tales. The real question, however, is whether this information is essential for settling in the United Kingdom. Citizenship tests are not a TV-game show “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire,” or information.com for life in the United Kingdom. They should set the sine qua non for becoming a citizen, and not test whether immigrants can snap back random trivia.

How Should the Test Be Designed?

Here are some guidelines for a future design of citizenship tests.

First, the test should be cognitive, something that can be learnt, rather than “moral,” a measure of one’s inner belief (belief can be encouraged, but not imposed or mandated).

Second, cognitive knowledge is not a blank check to implement policies without restraint. Immigrants should not be expected to spell out how “great” nudity is, or how impolite it is to attend a birthday party without a present, even if these issues are cognitive and learnable. The idea that there is one “correct” way to behave in society runs against liberal theory. Questions such as “What should parents of a 22-year-old girl do if they do not like her boyfriend?” are funny at best and absurd at worst.

Third, the test should focus on what is essential for a newcomer to know in order to become a citizen. Is it really essential to know “How might you stop young people playing tricks on you on Halloween?” or “Until what time do people play jokes on one another on April Fool’s Day?”

Fourth, even if the required knowledge is cognitive, legal, and essential, it should not necessarily be tested; there may be alternatives, such as orientation materials in a mandatory orientation day.

Fifth, the test should be fair and equal. When a test is intentionally designed to exclude specific ethnic groups, it may become discriminatory. Moreover, the procedure of the test must be fair. Among the pertinent issues are the test’s level of difficulty, its cost, the existence of preparation materials, and the number of times that the citizenship test can be retaken, and some possible exemptions of a mandatory test for elder, family, or illiterate people.

Citizenship tests, which are mushrooming worldwide, provide a unique opportunity to learn about Western societies. Reviewing citizenship tests help clarifying who is, in the state’s view, a “good citizen,” and the current understanding of what it means to become a citizen in the liberal state. Becoming a citizen is a serious step; citizenship is the most important benefit a state can offer to a foreigner. Putting immigrants to a test is not unlawful or immoral per se, but the test should not mock the process of citizen-making.

Which Citizenship Test Could You Pass?

Featured image: World Map – Abstract Acrylic by Nicolas Raymond (Freestock.ca). CC BY 2.0 via Flickr .

The post How do you decide who ‘qualifies’ as a citizen? appeared first on OUPblog.

Wine and social media

Can Instagram really sell wine? The answer is, yes, though perhaps indirectly.

In recent years the advent of social media, considered to be the second stage of the Internet’s evolution – the Web 2.0, has not only created an explosion of user-generated content but also the decline of expert run media. It’s a change that has led to the near demise of print media, the decline of the publishing industry more broadly, and a revolution in what it means to sell wine.

Social media has dramatically changed how information is shared. Wine experts and consumers alike now more often share information about wine via social media channels such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and wine blogs. Nielsen studies show that Internet users spend more time on social media sites than any other type of Internet site. This has changed the way news is shared, and even what consumers see as relevant information. As a result, consumers today are swayed far more by the influence of their online peers rather than expert authority. It’s led (among other things) to fewer permanent wine critic positions.

Prior to social media, readers and consumers turned to industrial media sources, and established wine critics for expert opinion. There was no access to the mass of information freely available today online. Expert opinion, then, was communicated via more traditional media channels like newspapers, magazines, and televisions shows. Wine experts traveled extensively (and still do today) then shared their insights through newspaper columns, monthly or quarterly magazines or newsletters. Without their own direct access to vintners, consumers were guided to new brands or top wines by these few voices of leadership. With the advent of social media, consumers are also able to connect directly to vintners via these same social media channels.

Wine Glasses at Sunset, by kieferpix, © iStock Photo.

Wine Glasses at Sunset, by kieferpix, © iStock Photo.While respected wine experts still exist and communicate with readers in a similar (albeit online) model, today when readers turn to such recommendations they do so in concert with those of wine loving peers. Within social media, specific wine-focused communities have arisen via wine dedicated mobile applications like Vivino or Delectable, electronic message boards and wine blogs specifically for the purposes of sharing wine information with wine lovers around the world. Further, traditional wine experts are now also in contact with and influenced by their readers via social media channels. Popular wine blogs that thoroughly research particular aspects of the wine world can influence established wine critics in traditional media positions or even become lead wine critics themselves. Websites like JancisRobinson.com, eRobertParker.com, and Antonio Galloni’s Vinous.com have their own message boards where readers message the experts directly. Conversations occurring on Twitter and Instagram between wine lovers sometimes inform what a wine expert discusses in their own feature articles. In other words, one of the effects of social media in wine has been a general democratizing of authority, dispersing it broadly across online networks.

Social media has also led to a change in wine marketing. The proliferation of information online has also increased general discussion about small production, and unusual wines among consumers. Small labels such as California’s Dirty & Rowdy Family Wine, as one example, launched from an essentially unknown brand to being distributed globally and sold-out within mere months of release in 2012 thanks partially to their presence on Twitter and Facebook. In their case, even a following of approximately 1400 on Facebook and 3200 on Twitter helped make a profound sales impact. By engaging directly with consumers via social media channels, Dirty & Rowdy was able to build an avid consumer following, communicate new releases directly, and expand their markets internationally. In other words, such engagement can lead to consumer consideration and review of wines that otherwise might not have been seen by the traditional wine critic. In this way, the democratization of wine information via social media has also supported consumer interest in broader wine selection.

Featured image credit: image created by Elaine Chukan Brown and used with permission.

The post Wine and social media appeared first on OUPblog.

November 8, 2015

Liverpool University Press: 5 academic books that changed the world

What is the future of academic publishing? We’re celebrating University Press Week (8-14 November 2015) and Academic Book Week (9-16 November) with a series of blog posts on scholarly publishing from staff and partner presses. Today, we present selections from our partner Liverpool University Press.

Which books have changed the world? While thoughts range from Karl Marx’s The Communist Manifesto (originally a political pamphlet) to George Orwell’s 1984 (a novel), great works of scholarship are often overlooked. However, it is these great works that can change our understanding of history, culture, and ourselves. Access to previously unseen historical documents has led to profound discoveries about the people and places that shape us today. Seemingly niche topics examined in depth have led to greater comprehension of the function of language (among other things). Indeed, even the form a published work takes can provide new dimensions and insight in a subject. Here are only five of the many titles from Liverpool University Press that have changed the world.

Photo by Sara Levine for Oxford University Press.

The post Liverpool University Press: 5 academic books that changed the world appeared first on OUPblog.

How to solve an anagram

Many word games—Scrabble, Words with Friends, Scribbage, Quiddler, and more—involve anagrams, or unscrambling letters to make a word. This month, we’re going to take a look at how to do that unscrambling.

Here is the first anagram for you to solve: naitp.

You could solve this with a brute force method, like a computer would. With seven letters, there are 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1, or 120, possibilities. You could work through all of them and look them up in the OED or in your own mental lexicon to find the ones that are legitimate words. At about a minute for each combination, that would take about two hours, not an efficient pace for people. We humans have to try other methods and here are some strategies.

1. Look for likely combinations of consonants

You can start with consonant patterns. Look at naitp, ignoring vowels at first. Instead of 120 combinations, there are just six: ntp, tnp, pnt, ptn, tpn, npt. Then you can expand those to 12 possibilities by adding the vowel sequences a-i and i-a between the three consonants. You’ll find the word patin that way.

“G4C15 Public Arcade at Tribeca Family Street Fair: Zynga.org Words with Friends EDU” by Games for Change. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

“G4C15 Public Arcade at Tribeca Family Street Fair: Zynga.org Words with Friends EDU” by Games for Change. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.You’ll also want to consider possibilities where the consonants cluster together. Here you can eliminate the initial combinations nt, tn, pn (which only occurs in long borrowed words like pneumonia and pneumatic), pt (which is limited to things like pterodactyl), tp, and np. Next think about combinations that might occur at the end of a word or syllable. You can eliminate tn, pn, tp, and np. Which leaves p—nt and n—pt. Trying the vowel combinations ai and ia between the dashes, you’ll quickly find paint. And when you try the vowels i and a at the beginning and end of each combo, you also get pinta and inapt.

2. When possible, start with suffixes

English makes word forms by adding endings. Some of these show grammatical distinctions of number, tense, aspect, comparison, and so on: The letters s, i, n, g, e, and r play a special role in building words: happy + er yields happier, write+ing+s gives writings, awake + en makes awaken, cook + ed is cooked. Inflection aside, new words are also formed by endings that shift the part of speech of a word: –y, -al, –ness, -th, -ity, -ish, -ly,-ion, -ian, –y, -ify, -ist, -ism, -able and –ible, -ance and –ence, -er and –re, -ize and -ise.

Why do suffixes help? Well, consider the anagram gineald. With 7 letters, there are 5040 possibilities, which will take far longer by brute force than the 2 hours needed for naitp. But if you recognize the gin of gineald as the ending –ing, you are left with eald, which gives you just 4 x 3 x 2 x 1= 24 choices, a manageable number to work out. You should quickly find the words leading and dealing.

3. Don’t forget prefixes

“Triple Letter Score (227/365)” by derrickcollins. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

“Triple Letter Score (227/365)” by derrickcollins. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Flickr.Some English prefixes involve the same letters as suffixes: –ed and de-, -er and re-, -en and en-. So, you can often find another anagram by flipping these endings to the front of the word: naitpre will yield both painter and repaint. English has dozens of other common prefixes that are worth getting to know—from a- (a+moral), bi- (bi+monthly) and con- (con+front) to di-, ex-, in-, mis-, per-, pre-, pro- re-, tri-, un-, and more. You can do the same reverse engineering with prefixes as with suffixes or you can recheck for prefixes after you’ve partially solved the anagram. Thus, looking at all of the possible prefixes in naitpre/painter/repaint will cause you to check in-, pre-, per-, and tri- and will soon lead you to the additional word pertain.

Try this one: roosnie. It’s got a lot of vowels and plenty of room for suffixes. The oo might suggest the word soon but quickly you run out of options for the rest: soon+ier, soon+eri, soon+ire, soon+rie. Instead focus on the possible endings –s,- en, -ens, -es, -ies, -er, -ier,-ion, -ions. Working back from the longest ending first, you might try –ions with various combinations of e, o, and r: eor+ions- reo+ions, oer+ions, roe+ions, ero+ions, and ore+ions. No luck. But if you try the next longest ending, –ion and shift the s to the root you get to the word erosion.

Here is one more example: When you have a lot of consonants and few vowels, it pays to start with familiar consonant combinations. Suppose you have the letters: etstlah. Working first with the likeliest consonant clusters gives you st-, -th, -st, -lth, and before long to the word stealth.

Now you give it a try. Here are four string of letters: sretkirc, blissope, creegin, and scedrin. You should be able to find the anagrams for each of them (the last one has three possibilities). The answers are below.

*sretkirc = trickers, blissope = possible, creegin = generic and scedrin = discern, rescind or cinders

Image Credit: “Brain Letter Blocks” by amenclinicsphotos ac. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to solve an anagram appeared first on OUPblog.

What defines good writing?

What distinguishes good writing from bad writing? How can people transform their writing to make it more powerful and more effective? Are universities teaching students how to become better writers? In order to answer these questions and others, we sat down with Geoffrey Huck, an associate professor of the Professional Writing Program at York University.

In your professional opinion as an associate professor of writing, what defines good writing?

I liken good writing to fluent speech, i.e., the kind of ordinary speech that any adult speaker without organic deficits uses naturally on a daily basis. It doesn’t draw attention to itself by being especially lyrical or confounded with solecisms; it’s just routinely effective for the various uses to which it’s put. There are differences between speech and writing, of course, but a good writer is functionally proficient in writing in the same way that an adult native speaker is functionally proficient in speaking. Neuroscience shows us that basically the same brain structures are responsible for fluency in both speaking and writing if you ignore the muscular aspects, so we should expect the two kinds of fluency to be related.

But if that’s so, why aren’t we all good writers?

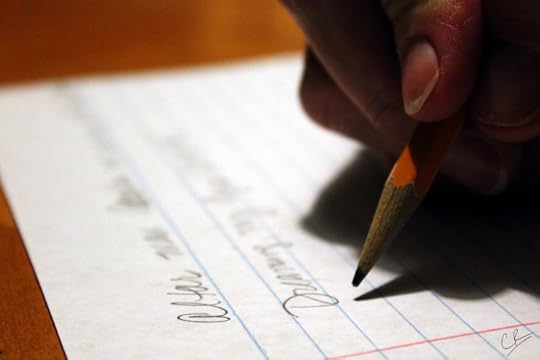

“Writing? Yeah.” by Caleb Roenigk. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Writing? Yeah.” by Caleb Roenigk. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.We become fluent speakers because as children, we have the opportunity and the motivation: we’re greedy to satisfy our physical, social, and emotional needs through verbal interaction, and in the normal case that requires learning to speak our native language fluently. From birth, we’re exposed to a vast number of utterances and linguistic patterns, which we naturally absorb over time (and with little explicit instruction). But written language is characterized by a much larger vocabulary and more complex linguistic patterns, so additional learning is usually required. If one’s primal communicative needs are satisfied by speech, there may be little motivation to develop writing skills to the same degree. For many of our students, the only reason they feel they should improve their writing is that we teachers tell them they should.

Aren’t you taking a rather elitist position here?

Not at all. On the contrary, I think our students are telling us that good writing isn’t particularly rewarded in our society and that as a result, they aren’t particularly interested in putting time into developing writing skills themselves. What’s elitist would be the idea that you can’t be a member of the elite unless you’re a good writer – or, for that matter, a good violinist, a good baseball player, or a good soldier.

But business leaders say all the time that colleges aren’t graduating people these days with appropriate writing skills.

The employment prospects of literature majors, who generally are good writers, have not improved and still seriously lag those of STEM, business, and health majors. You’d think that if business leaders really were concerned about that, they would start hiring humanities graduates in greater numbers. Instead, they hire the kinds of people they want and then later on discover that their writing skills are deficient.

For those students who want to improve their writing, how can they do so?

By reading. By doing lots and lots of reading. If you don’t read for your own pleasure and aspire to discuss your reading and the ideas developed therefrom with others who are important to you, you will probably never become a good writer. However, it’s not necessary that this reading be the kind assigned in courses. What is important is that you be fully engaged with what you read and that the text be somewhat challenging.

How about romance novels and fashion magazines?

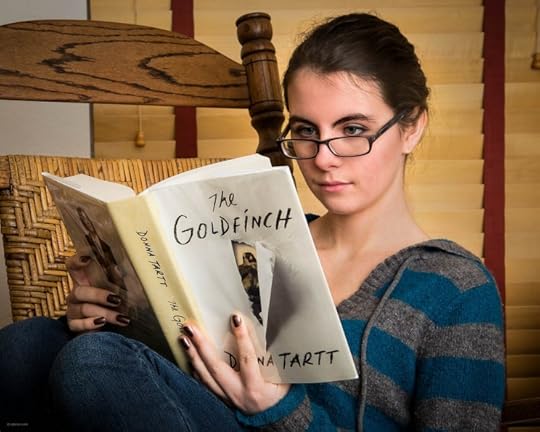

“Maia” by Earl McGehee. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Maia” by Earl McGehee. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Romance novels, sure. But I’m not so sure about fashion magazines, unless you hang on every word and are hoping to be a fashion writer yourself. There is some research that suggests that works of narrative fiction with gripping plots increase cognitive skills, and that may include writing skills. But the point, again, is that you have to be deeply immersed in what you are reading and to want to communicate with others about it.

You mentioned texting and e-mail. What about those?

I know of no research that connects time spent texting or e-mailing with quality of writing at the post-secondary level. All of the research I’m aware of involves the effect on writing of reading books. For all I know, there could be a correlation between texting and writing skill for business and education, but I would be skeptical. Importantly, you need to regularly read the kind of material that you want to read and that you want to be good at writing. That’s how you learn all the myriad complexities of good writing. There’s really no other way.

What about courses in composition and creative writing?

The research that has been done has not convinced me of the usefulness of these courses in improving quality of writing among reluctant readers, although of course many of my colleagues who teach those kinds of classes would strongly disagree. What I would be interested in is solid empirical evidence that they work, but there are serious problems with the methodology in many of the studies, principally because they involve teaching to the test and/or grading to the instruction, which skew the results. I do believe that such courses can help students who are already avid readers. But as a fix for writing deficiencies among post-secondary students in general, I don’t see them helping a great deal. More – and better – research is clearly needed here.

You seem pessimistic about the future of writing in the university.

No, I’m actually quite optimistic. There are probably more good writers today in school than there ever have been in history. Those of us who teach writing tend to focus on the students who are having trouble, which is exactly what we should do. But the reason they are having trouble frequently has little to do with the kinds of composition courses they have or have not taken and a lot to do with the role that reading for pleasure has been playing in their lives since childhood. Can we help a failing student dress up her or his essays in such a way as to get passing marks? Often we can, but that won’t make that student a good writer. We are deceiving ourselves if we think there is a simple pedagogical solution to the problem that doesn’t also involve a major change in interests and lifestyle on the part of that student. What I’d like to see is more cognitive realism about what goes into the making of a good writer, and a little more appreciation for anyone who has become one.

Featured image credit: “A typewriter” by Takashi Hososhima. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What defines good writing? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers