Oxford University Press's Blog, page 596

November 2, 2015

The killing of Osama bin Laden: the facts are hard to come by, and where is the law?

It is said in the domestic practice of law that the facts are sometimes more important than the law. Advocates often win and lose cases on their facts, despite the perception that the law’s formalism and abstraction are to blame for its failures with regards to delivering justice.

In the realm of international law again facts are surprisingly significant, and yet often hard to come by. Courts and tribunals rely on states for evidence, and increasingly too on the media and civil society for the facts upon which to make decisions. Despite the modern proliferation of law-making, institution-building, and dispute resolution, international norms and legal frameworks still require facts.

Notoriously, international law itself is dynamic, often unenforceable, increasingly ‘soft’ in character, subject to intense contestation and disagreement, and characterised by its critics as utopian and otherworldly. International lawyers are sensitive to such criticism and yet it seems that their time has come.

Law students now study international, transnational, or global law in their standard curriculum to prepare for practice in a globalising world. Human rights have become a dominant normative language with which to frame politics and questions regarding responsibility and intervention. International law has entered the mainstream. When countries go to war citizens, the media, and politicians ask, “is this lawful?” Public debate and opinion engages directly with legal norms and frameworks – so too it seems do decision-makers. In the field of international humanitarian law, legalism has become so dominant that we talk of the phenomenon of ‘lawfare’.

Why then do we know so little about the death of Osama bin Laden? And why, until recently, have relevant questions regarding international legal issues flowing from his killing received so little attention in scholarly and public debate? This is an international legal ‘event’ par excellence, but without a corresponding legal analysis and without the material facts.

Such facts as exist are to be gleaned from media reports, official US accounts, first-hand accounts given by a former SEAL who claims to have been the shooter, and the images provided both in official publicity, but also crucially in film. The film Zero Dark Thirty has dominated popular perceptions of the hunt for bin Laden and acts as a framing mechanism for understanding both the event itself as history and as a mission for the Navy Seals involved, but also as highly ambiguous, unresolved, and contentious.

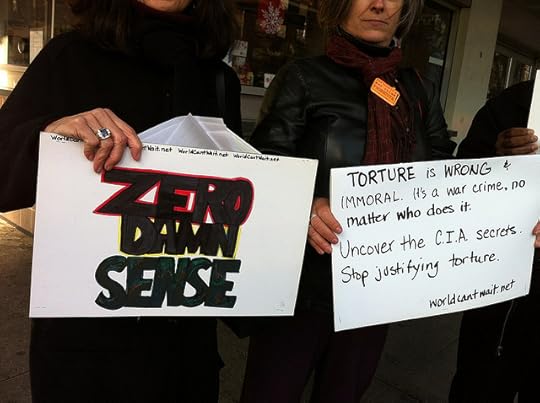

Protesting Zero Dark Thirty in NYC by Debra Sweet. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Protesting Zero Dark Thirty in NYC by Debra Sweet. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.While few have directly contested the official narrative provided, many have criticised the film and its perceived association with government and the US intelligence services. But despite its mainstream allure, the film does not offer the material facts we need. Whilst it alludes to the unlawful nature of torture at CIA black sites in the hunt for bin Laden, it is silent as to the international legal issues arising from the killing itself. Was it lawful, can the incursion into Pakistani territory be justified, was bin Laden a present threat in terms of terrorism, did elements of the Pakistani military and/or intelligence services know of bin Laden’s whereabouts, and what responsibility should ensue?

At the time of writing this post, that ambivalence and silence is shifting. A recent feature in the New York Times Magazine asks “What Do We Really Know About Osama bin Laden’s Death?,” with Jonathan Mahler observing that the “official narrative of the hunt for and killing of bin Laden at first seemed like a clear portrait, but in effect it was more like a composite sketch… And when you studied that sketch a little more closely, not everything looked quite right.” A Washington Post article has responded with the retort – “What do we know about Osama bin Laden’s death? Quite a lot, actually” with Greg Miller writing that “the reality is that there is remarkable agreement across antagonistic governments, credit-hungry security agencies and fiercely competitive news organisations on the most salient facts: that bin Laden was killed in a raid by US Special Operations forces conducted without the cooperation or awareness of the Pakistani government after a decade-long CIA manhunt.”

But doubts about ‘the greatest manhunt ever’ remain. Sceptic-in-chief, Seymour Hersh first stirred the pot with a long piece in the London Review of Books. But suggestions were made that Hersh, whose long and distinguished investigative career includes scoops such as the My Lai Massacre and Abu Ghraib, had failed to get his controversial piece published in The New Yorker and that his sources were thin on the ground. Attempting to prod our collective amnesia, Hersh points to the US Senate Intelligence Committee’s findings that called into question claims that the CIA’s torture program had contributed to intelligence that led to bin Laden.

This false premise formed a central plank in the narrative of Zero Dark Thirty. Hersh’s target is the lying that he alleges “remains the modus operandi of US policy, along with secret prisons, drone attacks, Special Forces night raids, bypassing the chain of command, and cutting out those who might say no.” He calls into question the factual matrix provided and its faithful dramatization by Hollywood, but intriguingly his own critics rely on this very absence of facts to undermine the credibility of Hersh’s reporting. Without more his accusations are said to fly close to conspiracy theory – though a theory that is now finally appearing to gain the mainstream media’s interest and the public’s attention.

For too long the killing of bin Laden has been allowed to be framed as entertainment or as revenge and even catharsis. By keeping the detail of the material facts at one remove, in the realm of intelligence and the secrecy-driven War on Terror, the Obama administration has also kept the law question at bay. For if the facts often trump the law, equally it can be said that the law without facts can flounder. International legal analysis and institutions deserve better facts in this case, and in many others.

The post The killing of Osama bin Laden: the facts are hard to come by, and where is the law? appeared first on OUPblog.

What are the biggest challenges facing international lawyers today?

What role does international law play in addressing global problems? How can international lawyers innovate to provide solutions? How can they learn new approaches from different legal systems? Which fields require greater research and expertise?

With International Law Weekend (ILW) fast approaching, we asked some of our key authors to share their thoughts on this year’s conference theme — Global Problems, Legal Solutions: Challenges for Contemporary International Lawyers.

* * * * *

“The integration of worldwide financial and commercial markets has occurred at an astonishing speed over the last thirty years. Market participants now routinely lend, borrow, invest, trade, hedge and pledge in jurisdictions other than their own. They expect their lawyers to tag along with them in these global adventures.

“For the lawyers, compulsory cosmopolitanism can be discomforting. It isn’t just that laws and judicial procedures differ from one jurisdiction to another. It is something more subtle. Lawyers trained in different legal systems may approach legal problems, client relations, professional etiquette, ethical questions, legal drafting, and correct professional demeanor in remarkably different ways.

“Most lawyers are oblivious to the depth of their own parochialism until they are forced to transact business abroad. We insensibly absorb in law school and the early years of practice an impression of how lawyers ought to think, talk, and behave. And we all insensibly carry with us those notions about the proper deportment of a lawyer when first we venture into the world of cross-border transactions.

“That is when the trouble can begin. Conduct that may be regarded in one place as demonstrating admirable zeal in the pursuit of a client’s interest may strike observers elsewhere as gratuitously gladiatorial and abrasive. At the opposite extreme, lawyers who adopt a posture of respectful reticence in a business setting risk being perceived by client and counterparty alike as bovinely impassive. Commendable attention to detail in one culture may, in other places, be persnickety pencil-pushing. A finely honed sense of the line between the ‘legal’ and the ‘commercial’ aspects of a transaction, and a lawyer’s refusal ever to trespass across that line, may infuriate clients who expect their lawyers to function as an integral part of a deal team, not act as detached legal advisers whenever a pristinely legal issue has been identified.

“The biggest challenge facing international lawyers is therefore self-awareness; the need to recognize one’s own parochialism in the practice of this profession.”

—Lee C. Buchheit, Partner at Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP, New York, and editor (with Rosa Lastra) of Sovereign Debt Management (OUP 2014), also avaiable on Oxford Legal Research Library

* * * * *

“Perhaps the biggest challenge for international lawyers today involves the way in which they conceptualize themselves and their field. ‘International lawyers’ are often seen as focusing primarily if not exclusively on inter-state issues, i.e. public international law. However, globalization has triggered a rapid expansion in the need for experts in private international law. In many ways, this field is even more demanding than public international law, since private international lawyers must gain competence in a particular area of private law (such as family law, criminal law, commercial law and/or arbitration law) as well as expertise in comparative law and international law, including matters relating to both private international law (for example, various conventions promulgated by UNCITRAL or the Hague Conference) and public international law (for example, instruments such as the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties). The situation is made even more difficult because law schools and faculties often do a poor job of training private international lawyers, although there are a few notable exceptions. Looking forward, one hopes that the legal community will begin to recognize the importance of private international law as a specialized field of study and practice and to support the development of experts in this area of law.”

—S.I. Strong, Manley O. Hudson Professor of Law, University of Missouri School of Law, author of Class, Mass, and Collective Arbitration in National and International Law (OUP 2013), also available on Oxford Scholarship Online, and Research and Practice in International Commercial Arbitration: Sources and Strategies (OUP 2009), also available on Oxford Legal Research Library

* * * * *

“Our age is pluralistic. There is no prospect that one specific understanding of international law and one specific project of internationalism will ever come to dominate the profession again. International lawyers are bound to continue to disagree on the frameworks they use to make sense of international law and the projects they want to realise through international law. Such pluralism is not necessarily a bad thing. With pluralism comes an opportunity to acquire more self-awareness about one’s presuppositions and pre-reflective structures Yet, with pluralism comes a risk of fatigue. Indeed, in a pluralistic age, debates on international law requires each participant to reach out to (and understand) the pre-reflective structures of others. Such debates necessitate that any claim about how we understand international law and what we make of it is situated. Debates on international law are thus more painstaking and laborious. Debates on international law may even come to look like debates held in international relations circles. In this context, the risk is not only that international lawyers get tired of situating their claims and disclose their pre-reflective structures but that they also get bored of debates themselves. This is one of the greatest challenges of the pluralistic age we live in.”

—Professor Jean d’Aspremont, Director of the Manchester International Law Centre (MILC), University of Manchester, author of Formalism and the Sources of International Law (OUP 2011), also available on Oxford Scholarship Online, and director of the forthcoming Oxford Database on International Organisations (OXIO)

* * * * *

“A challenge for lawyers concerned with the UN Security Council is coming to grips with the Council’s impact on the development of international law. The issue has become sharper — and more interesting — in recent years as the Council has: (1) broadened the definition of what constitutes a threat to peace and therefore falls within its purview (such as infectious disease); and (2) expanded its ‘quasi-legislative’ powers to impose obligations on all states for an indefinite period in a broad issue area (such as counter-terrorism). While there is much to be said for a proactive Council filling gaps in international law, especially if in so-doing it is able to prevent crises and atrocities, there is risk of the five permanent members abusing that power by making or interpreting the law in a manner that suits them but not the international community more broadly. Fortunately, some checks on the Council do exist, for example the reputational costs associated with being seen to violate accepted norms. A fascinating challenge for lawyers is how to put teeth in those checks while helping to create the space for the Council to act creatively in addressing global threats — both new and old.”

—Ian Johnstone, Professor of International Law at Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, and co-author (with Simon Chesterman and David M. Malone) of the forthcoming Second Edition of Law and Practice of the United Nations

* * * * *

If you’re attending International Law Weekend, don’t forget to stop by the OUP booth to see our collection of international law titles discounted 20%, pick up a postcard for free access to law’s online resources, and browse our collection of law journals. To stay connected throughout the conference, follow us on Twitter @OUPIntLaw and like our Oxford International Law Facebook page.

See you in New York!

Featured image: New York City. CC0 via Pexels.

The post What are the biggest challenges facing international lawyers today? appeared first on OUPblog.

November 1, 2015

Ben Bernanke and Wall Street Executives

In a widely quoted interview with USA Today, Ben Bernanke said that ‘It would have been my preference to have more investigations of individual actions because obviously everything that went wrong or was illegal was done by some individual, not by an abstract firm.’ He makes it clear that he thought some Wall Street executives should have gone to jail. However, ‘the Fed is not a law enforcement agency. The Department of Justice are responsible for that, and a lot of their efforts have been to indict or threaten to indict financial firms. Now a financial firm is of course a legal fiction; it’s not a person. You can’t put a financial firm in jail.’

Going after firms is precisely what the Department of Justice has been doing in the aftermath of the financial crisis. This was nothing new. For some decades, prosecutors have preferred to go after companies rather than individuals, partly because of the alleged difficulties in prosecuting individuals, but also on the grounds that this was an attempt to change the ‘corporate culture’ so as to prevent future crimes. The result has been ‘deferred prosecution agreements’ and even ‘non-prosecution agreements’ in which companies agree to undertake various reforms to prevent future wrongdoing. Such agreements became the mainstay of white-collar criminal law enforcement. There is little evidence that such an approach, including the imposition of heavy fines, does actually change the behaviour of companies. It did, however, bring in billions of dollars ($220 billion by March 2015) and kept government housing policy, which required Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to buy ever-increasing proportions of subprime loans from the lenders, out of the picture in any cases brought against the lenders.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the Department of Justice brought many high profile cases against leading banks, but these were settled out of court, as they resulted in the kind of negotiations which were roundly condemned by Judge Jed Rakoff. He described just going after the company as ‘both technically and morally suspect’ since the prosecutors can only threaten to prosecute the company if there is sufficient evidence to prove beyond reasonable doubt that fraud has been committed, and, if that can be established then the managers concerned should be indicted.

Such condemnation from a judge, from politicians and media led to a radical change of direction announced by the deputy Attorney General in her Memorandum on 9 September. Sally Quillian Yates announced that in the future, the Department of Justice will turn its attention to individual accountability, since one of the ‘most effective ways to combat corporate misconduct is by seeking accountability from the individuals who perpetrated the wrongdoing.’ She argued that this ‘deters future illegal activity; it incentivizes changes in corporate behaviour, it ensures that the proper parties are held responsible for their actions, and it promotes the public’s confidence in our justice system.’ Ben Bernanke’s remarks are certainly in line with the changing views about law enforcement.

However, that is not the fundamental issue concerning the past. It would, of course, have been possible to bring criminal charges against senior executives if they could be shown to have been guilty of fraud as individuals, but the charges were always against the company. The real question is: if senior executives are to be held accountable, then the laws and regulations should be clear, and of course, in force at the time to ensure that administrative actions or prosecutions could take place. For Bernanke to say that some senior executives should be in prison implies that he considers that it was possible to do under the regulations or the laws in existence at the time, but that the regulatory authorities did not refer any case to the Department of Justice nor take the administrative actions open to them at the time or in the aftermath of the financial crisis. The fact that they did not do so implies that they had no case.

Bernanke was in a position to ensure that regulations were in place so that senior executives could be called to account, but his speeches and the full minutes of the Federal Open Markets Committee indicate that he did not see the risks in the growth of the subprime market and weak regulation. Indeed, Bernanke seemed unaware of the extent of subprime lending and its impact on the economy or even on the banking sector. Even as late as May 2007, he stated, ‘we do not expect significant spill-overs from the subprime market to the rest of the economy or the financial system.’ In June 2007, he announced a review of the rules governing lending practices and supervision. It was too little, too late. Looking back later, Bernanke admitted that ‘stronger regulation and supervision aimed at the problems with underwriting practices and risk management would have been more effective in containing the housing bubble.’ The Big Five investment banks voluntarily agreed to be supervised by the SEC under a special, undemanding regulatory regime. Inadequate regulatory frameworks and an unwillingness to take action against individuals meant that senior executives would not, and often could not be taken to task for their alleged misdeeds.

Featured image credit: “The corner of Wall Street and Broadway, showing the limestone facade of w:One Wall Street in the background” by Fletcher6. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ben Bernanke and Wall Street Executives appeared first on OUPblog.

Raw politics: devolution, democracy and deliberation

As a long-time student of politics I have often found myself assessing various kinds of attempts to create new democratic processes or arenas. From citizens’ juries through to mini-publics and from area panels to lottery-based procedures the scope of these experiments with ‘new’ ways of doing politics has taken me from the local ward level right up to the international level. In undertaking these studies the work of leading scholars, such as John Dryzek and Frank Fischer and John Parkinson — all, I should note, Oxford University Press authors — has been invaluable in terms of helping me understand the challenges and complexity of engaging with multiple publics in multiple ways.

And yet my knowledge had always been remote; garnered as it was through books and articles rather than being forged in the heat of running a deliberative process myself. I had, of course, observed the odd event and had even acted as an academic advisor to one or two ‘experiments’ but my role was always somehow peripheral and distant. Put slightly differently, as an academic I had never stepped into the political arena myself to lead and manage a deliberative event around a specific political challenge. Why soil my hands in the rough-and-tumble of real politics when so many others appear to relish the challenge?

But academic life is changing. Academics are increasingly expected to put their heads above the parapet in terms of engaging with public debates and media controversies. They are also expected to demonstrate the basic value and role of the social and political sciences in increasingly visible and demonstrable ways. The point I am rambling myself (and therefore the reader) towards is that last weekend I actually did it!

I actually did it!

With a fabulous group of colleagues and researchers from the University of Sheffield, Southampton University, Westminster University, University College London and the Electoral Reform Society I actually helped to design, manage and deliver a large citizens assembly. It’s focus was the Government’s current plans for ‘devo deals’, ‘metro mayors’ and all that sort of thing but the learning process was far more complex and enriching.

This was raw politics in the sense that forty-five members of the public gave up their whole weekend to learn about, discuss and deliberate the pros and cons of various forms of localism and devolution. It was ‘raw’ in all sorts of ways but not least because the citizens were new to the process, a good cross-section of society had been selected and – most of all – because it was up to the project team to look after and support these good men and women of South Yorkshire not just over the next two days but also for the whole six week assembly process with its constituent phases.

So what did I learn, not about devolution or localism in England, but about the politics and management of deliberative projects?

The first and most basic insight was that the planning of the event is critical in the sense that many of the participants are understandably nervous, this is a new experience for them, and therefore a smiling face and lots of help with the simple issues of finding rooms, leaving bags, registering and knowing where food and drink is available is crucial to the success of the initiative. In many ways all this underpinning work should take place in an efficient manner ‘off stage’ so that the participants feel valued and supported and can therefore focus on contributing to the assembly.

The second insight became really clear to me as the weekend progressed – we were not simply facilitating an assembly in order to fulfill a very clear academic methodology (although we were doing that), we were creating a new community. This is critical because what became more and more evident as the sessions and stages progressed was that a form of social capital was emerging between the assembly members. This took the form of mutual understanding, trust, shared values, an emphasis on listening as well as talking …right through to body language and the sound of laughter as well as speech. What was fascinating to me as a political scientist was that it was possible to almost sense or smell the assembly maturing and developing together as time went on. I’m not saying that there were not challenges or that the project team got everything right all of the time but there was something quite inspirational about bringing a group of people together, who had previously never met each other and came from a broad geographical landscape, to explore a specific political issue. As the bonds created within the assembly grew and tightened so the role of the project team slipped back to a more supporting function. The assembly had almost developed a personality and life of its own.

The third and final insight was more personal and revolved around my own academic experience. Indeed, it would not be over-egging the pudding to suggest that I learnt more about the nature of politics in that one weekend than I had as an academic during the previous two decades. There was a raw energy, a passion and a social learning element that is simply impossible to perceive from the pages of a book. I should, however, note that running a deliberative assembly can be stressful, tiring, demanding, etc. but in this case I was very lucky to be part of a large and well-organised team. So maybe the experience was not quite as ‘raw’ as I’d like to think but it certainly opened my eyes to the difference between ‘the theory of politics’ and ‘the practice of politics’ in ways that I will never forget.

Featured image: “Political Assembly 22-23 January 2015″ by European People’s Party CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Raw politics: devolution, democracy and deliberation appeared first on OUPblog.

The future of married priests

“Western clerical celibacy is in an unprecedented crisis,” says the conservative Catholic canon lawyer Edward Peters. The reason? Since the 1960s, the Catholic Church has permitted married men to be ordained as deacons, an order of clergy just below that of priests; and in the past 35 years about 100 married converts, all former Episcopal priests, have been ordained to the Catholic priesthood. “A lot of people are going to see this as a foot in the door,” said the spokesman for the US bishops when the decision to receive these priests was announced in 1980.

Are these married priests a foot in the door to end required clergy celibacy in the Catholic Church? If you ask them, they certainly don’t think so. They are an unlikely vanguard for change. Very conservative in their views, two-thirds of them oppose optional celibacy—only half of celibate priests do—and are uncomfortable with the idea that their presence may challenge it. They don’t exactly hide being married, but they don’t flaunt it either. Mostly they try their best to fit in with Catholic priestly culture and norms, not challenge or change it.

People say that married priests would help end a shortage of Catholic clergy, but the response to the Church’s openness to receive married priests has so far been underwhelming. Only a handful has come in, and after an early spike of converts in the 1980s, the pace has slowed to a trickle. If it is a crisis, it seems that not many applicants are showing up.

Catholic canon law defends clergy celibacy on the ground that celibate priests are more able to be devoted to the care of a parish than married ones would be—an argument that has its roots in the Bible. In my research I found that married priests worked a little harder than celibate ones did, prayed more, and were more available to parishioners in need. People often think married priests cost a lot more for a parish to maintain, but the difference in compensation is actually quite small, well under ten percent. And if the married priest gets his health insurance—a major factor in priest compensation—through his wife’s employer rather than the parish, he can cost a lot less to maintain.

Image credit: ‘Prayers’ by firstworldchild. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: ‘Prayers’ by firstworldchild. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.In all, marriage did not present many disadvantages for the function of Catholic priestly ministry. But it also did not present many strong advantages either in a way that would make an urgent case for moving to optional celibacy.

The last three popes have all encouraged married priest converts from Anglicanism while making it clear that they have no thought of changing the rule of celibacy for ordinary Catholic priests. The reception of married priests was supposed to be a temporary accommodation to trauma in the Episcopal Church—a ‘pastoral provision.’ At some point, it is envisioned, it will end, and Catholic priests with roots in Anglicanism will have to be celibate, like any other priest. But it has been continuing now for 35 years, and will not likely end anytime soon. Meanwhile over 10,000 men who since 1970 left the priesthood to marry have been quietly readmitted to the priesthood after their marriages ended. And Pope Francis has also quietly ended the century-old prohibition on married Eastern Rite priests in the United States. This is hardly a crisis of celibacy, but there does seem to be a softer attitude, a growing toleration and comfort with the experience of priests who are married.

In one way the married priests, without intending it, may have put a foot in the door. Married priests reported that their reception by parishioners and other priests has been overwhelmingly positive, a perception that is confirmed by the highly positive opinion that almost all priests and bishops expressed about the married convert priests in their midst. For many Catholics, and Catholic leaders, the idea of a married priest is no longer abstract or theoretical. The married priests have shown how it is that a man can be a good priest and also be married. In this way, at least, the married former Anglican priests may have contributed more than they realize to change—not a crisis, but an incremental openness—on the question of Catholic clergy celibacy.

The post The future of married priests appeared first on OUPblog.

October 31, 2015

Preparing for International Law Weekend 2015

This year’s International Law Weekend (ILW) will take place in New York City, from 5 November through the 7th. Organized by the American Branch of the International Law Association and the International Law Students Association, this annual event attracts over 800 attendees including practitioners, diplomats, academics, and law students.

The ILW 2015 theme is Global Problems, Legal Solutions: Challenges for Contemporary International Lawyers. Daily panels will give attendees an opportunity to discuss and debate the role of international law in addressing global challenges, as well as explore innovative resolutions to these problems. The conference’s opening panel takes place at the House of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York on Thursday evening, followed by a reception for all conference attendees. Friday’s and Saturday’s keynote address and panels will be held at Fordham University School of Law.

All the conference events should incite important conversations about international law’s power to address evolving global issues. In addition, the wide variety of topics will present a comprehensive overview of developments in the different areas of international law.

Our Top Panel Picks:

The Road to Paris: What Can We Expect from the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change?

Friday, November 6, 9:00 a.m.

The upcoming 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change will be the topic of this roundtable, where participants will discuss the effectiveness of the likely outcomes of the conference. Before attending this panel, read the first chapter of The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development: A Commentary to get a better idea of the impact of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, adopted at the Earth Summit in 1992.

It’s “Shocking” to Think There Is Corruption at FIFA

Friday, November 6, 10:45 a.m.

This panel will seek to answer the many questions raised by the FIFA indictment of 14 individuals and also discuss developments in this international prosecution. If you’re looking for a detailed explanation of the history and development of international anti-corruption norms, we’ve made the introduction of International Anti-Corruption Norms: Their Creation and Influence on Domestic Legal Systems freely available.

Saving Lives and Building Society The EU’s New European Migration Agenda

Friday, November 6, 3:00 p.m.

Panelists will look at measures in the new EU “European Migration Agenda” which was implemented in response to the worsening humanitarian crisis. Read the introduction of Marie-Bénédicte Dembour’s When Humans Become Migrants: Study of the European Court of Human Rights with an Inter-American Counterpoint, to learn more about how the European Court of Human Rights and Inter-American Court of Human Rights engage with claims lodged by migrants.

Ethics for Counsel in International Adjudication

Friday, November 6, 4:45 p.m.

In this session, Chester Brown, along with co-panelist Judge Joan Donoghue and moderator Jeremy Sharpe, will look at unclear or nonexistent ethics rules for counsel in international adjudication. Brown is the editor of Commentaries on Selected Model Investment Treaties, part of the Oxford Commentaries on International Law series.

Law-making by the UN Security Council

Friday, November 6, 4:45 p.m.

Ian Johnstone, one of the co-authors of the forthcoming new edition of Law and Practice of the United Nations, closes out the first day of panels as a participant in this session, which will address the UN Security Council’s role as a lawmaker.

The Individual Petition Procedure in International Human Rights Law: Has It Lived Up To Its Expectations?

Saturday, November 7, 9 a.m.

Dinah Shelton kicks off the final day of the conference with this panel focused on recent criticisms to the international human rights law movement. If you’re attending, read the introduction of The Oxford Handbook of Human Rights Law, edited by Shelton, which has been made freely available on Oxford Handbooks Online.

International Courts as Architects of the International Legal System and SubSystems

Saturday, November 7, 1:45 p.m.

Jean d’Aspremont is one of the panelists taking on this session examining international courts’ contribution to consolidating secondary rules of international law. d’Aspremont’s Formalism and the Sources of International Law is part of the Oxford Monographs in International Law series and you can read the book’s Introduction for free on Oxford Scholarship Online.

Rising Seas, Baselines Issues: The Work of the International Law Association Baselines and Sea Level Rise Committee

Saturday, November 7, 1:45 p.m.

The Oxford Handbook of the Law of the Sea contributor David Freestone will participate in this panel which will explore two International Law Association committees and their current work with the law of the sea. Freestone’s co-written Handbook chapter on the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico is freely available for you to read before the session.

From international arbitration and sovereign debt, to human rights and the law of the sea, International Law Weekend will explore many emerging trends in international law and its various sub-disciplines. It will be a busy couple of days, but luckily you’ll be in the city that never sleeps! Make some time to explore some of the Big Apple’s many attractions, a lot of which won’t take you too far from the conference.

If you’re attending International Law Weekend, don’t forget to stop by the OUP booth to see our collection of international law titles discounted 20%, pick up a postcard for free access to law’s online resources, and browse our collection of law journals. To stay connected throughout the conference, follow us on Twitter @OUPIntLaw and like our Oxford International Law Facebook page. See you in New York!

Image Credit: “Law” by Daniel Kulinski. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Preparing for International Law Weekend 2015 appeared first on OUPblog.

Catching up with Jack Campbell-Smith, Multimedia Producer

Another week, another great staff member to get to know. When you think of the world of publishing, the work of videos, podcasts, photography, and animated GIFs doesn’t immediately come to mind. But here at Oxford University Press we have Jack Campbell-Smith, who joined the Social Media team as a Multimedia Producer just last year.

When did you start working at OUP?

I started at OUP on the 1st September 2014 – Just over a year ago!

What is the longest book you’ve ever read?

I think one that I’ve very recently finished, The Count of Monte Cristo.

What is your favorite word?

Zephyr – It was my go to put down as a child. I’m not sure how that started, but it usually confused people a lot.

Which book-to-movie adaptation did you actually like?

I think my favourite has to be Lord of the rings. I can’t even count how many times I’ve watched those films. I’ve even managed the extended version marathon once or twice…

Mr Purple. Photo by Jack Campbell-Smith

Mr Purple. Photo by Jack Campbell-SmithWhat is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

A very aptly named ‘Mr Purple’ created by the Blog’s very own Dan Parker. Unfortunately he has lost his arms over the last few months, but he’s got the Dude to keep him occupied.

What are you reading right now?

The Narrow Road to the Deep North by Richard Flanagan. It won the Man Booker in 2014 and it was recently recommended to me.

What is your most obscure talent or hobby?

I’m pretty good at splitting an apple perfectly in two using just my hands.

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

Creating an introduction section for a small series of videos for the Oxford Companion to Wine.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

I’ll usually start the day by grabbing a coffee and then going over emails and checking some of the social channels. After that it can vary depending on what’s on: either filming an author, having meetings to plan projects, animating and/or editing different projects.

What is your favorite animal?

I saw a squirrel patting down some mud with it’s little hands after burying something the other day. So at the moment it’s squirrel.

The post Catching up with Jack Campbell-Smith, Multimedia Producer appeared first on OUPblog.

Shakespeare and the suffragettes

The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were famously the age of “Bardolatry,” Shakespeare-worship that permeated artistic, social, civic, and political life. As Victorian scientific advances including Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, published in On the Origin of Species (1859), destabilised Christianity as ultimate arbiter of truth, rhetoricians invoked Shakespeare’s plots and characters to support their arguments.

The Victorians weren’t the last to appropriate Shakespeare for political purposes. At World War I recruitment rallies, actor Frank Benson (1858–1939) performed Henry V to encourage patriotic young Englishmen to sign up to fight in France and Flanders. During the Third Reich, the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer compared Hamlet to recent German history. Claudius’s usurpation of the Danish throne, denying Hamlet his rights, supposedly recalled the Treaty of Versailles (1919), which had financially crippled Germany in the wake of the First World War. But in the Edwardian era, another group found it powerfully useful to turn Shakespeare’s plays – and above all Shakespeare’s heroines – to their political advantage. These were the suffragists.

Looking at fin-de-siècle and Edwardian theatrical debates about gender roles, Ibsen’s trapped but rebellious heroines are one important focus of debate. But the suffragists and militant suffragettes had inherited Shakespearean heroines like Ophelia (Hamlet), Imogen (Cymbeline), and Hermione (The Winter’s Tale) as beloved Victorian icons of female fidelity, passivity, and suffering. Yet the burgeoning suffrage movement co-opted Shakespeare, claiming that his plays supported independent, rebarbative women.

Portrait of Ellen Terry (1847-1928). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Ellen Terry (1847-1928). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Beloved Victorian actress Ellen Terry (1847–1928), whose daughter Edith Craig (1869–1947) was an ardent suffragist, argued in her lectures that Shakespeare’s women “certainly have more in common with our modern revolutionaries” than with early Victorian literature’s “fragile domestic heroines.” A prologue spoken by suffragist actress Fay Davis at an 1911 Actresses’ Franchise League matinee suggested that if Ophelia had had the franchise – “If instead of suicide-suggestion, / To vote or not to vote had been the question” – Ophelia would have met Hamlet’s “male insolence of sneer and doubt” with “mocking flout,” not madness.

However, The Winter’s Tale proved the suffragists’ favourite Shakespeare play. Shakespeare’s late romance sees Hermione, queen of Sicilia, groundlessly accused of adultery and imprisoned for treason by her husband Leontes. Hermione gives birth to a daughter, Perdita, in prison, whom Leontes rejects. Weak from childbirth, Hermione is exonerated in court by the Oracle at Delphi; however, when Leontes unjustly dismisses the overwhelming evidence of her innocence, both Hermione and her eldest child, Mamilius, suddenly die. Remorse-stricken, Leontes mourns for sixteen years, until Perdita is found, and Paulina, Hermione’s gentlewoman and outspoken supporter, reveals that she has been secretly protecting Hermione, who’s been in hiding since faking her death. The family is miraculously reunited (apart from Mamilius, who stays dead).

In 1912, Lillah McCarthy played Hermione in her husband Harley Granville-Barker’s Royal Court production. McCarthy was an Actresses’ Franchise League member, and inspired Emmeline Pankhurst as Ann Whitfield in George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman (1906). She had also portrayed Justice in Cicely Hamilton’s feminist Pageant of Great Women (1910). In 1912, suffragist newspapers saw McCarthy’s Hermione as an imprisoned suffragette, sent to “Holloway” by Leontes’s “Cabinet Minister.” The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) newspaper Votes for Women entitled its review “The Conspiracy Trial of Hermione” and identified Esmé Beringer’s Paulina as a character who “could have been written since 1905.” For the Suffragette newspaper, Paulina was not just an activist, but “the eternal Suffragette whom the greatest geniuses of all ages have loved to portray.”

Paulina reminded suffragettes of their own experience supporting friends in prison. The Votes for Women critic gave Paulina’s Shakespearean lines an intensely modern setting:

Waiting in the ante-room to see the Governor, and filled, as so many of us have been at the gates of Holloway since 1905, with a sense of the irony of such imprisonments, she exclaims: “Good lady, / No court in Europe is too good for thee, / What dost thou then in prison?”

Paulina inspired the suffragettes because she wasn’t an icon of passive endurance like “dignified, patient, unprotesting Hermione.” As the Suffragette newspaper noted, if ‘all women’ were as docile as Hermione, “Hermiones would continue to be unjustly degraded, Perditas to be unjustly abandoned.”

The suffragists weren’t only fascinated by Shakespeare’s heroines. They attended Stratford-upon-Avon’s Shakespeare Festival and annual Shakespeare’s Birthday Celebrations (still held today). In 1909, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) adopted Shakespeare’s heraldic colours for one Stratford banner, which they decorated with the words “To be or not to be.” They also insisted in participating in the annual processions to Shakespeare’s grave. In the same year, the WSPU were “undoubtedly the most conspicuous figures in the procession,” carrying bouquets of flowers in their union colours of green, purple, and white.

On Shakespeare’s birthday, the 23 April edition of Votes for Women reported that leading suffragette Emmeline Pethick-Laurence, newly-released from prison, had “read the historical plays of Shakespeare” during her imprisonment. At a celebratory meal, Pethick-Lawrence recited Henry V’s St Crispin’s Day speech to fellow-activists, telling them that the spirit of Agincourt was “the spirit that dwells in us.” Where Henry V told his followers that “I would not lose so great an honour, as one man more, methinks, would share from me,” Pethick-Lawrence extrapolated: “that’s what I want you to feel. Don’t let one more go to prison without your being there.” Frank Benson wasn’t the only Edwardian to appropriate Henry V for political purposes. For the activists of the WSPU, Shakespeare was undoubtedly a suffrage playwright. Perhaps that is why the suffragettes’ militancy, despite rumours in 1913, never extended to vandalising Shakespeare’s Birthplace. Some cultural icons, it seems, retain their sanctity.

Featured image credit: Photo shows a woman suffrage meeting in New York City, where British suffragist leader Emmeline Pankhurst addressed a crowd near the Subtreasury Building on Wall Street, New York City, on November 27, 1911. Bain News Service. Public domain. Library of Congress.

The post Shakespeare and the suffragettes appeared first on OUPblog.

Seders, symposiums, and drinking parties

The symposium is a familiar feature of academic life today: a scholarly gathering where work on a given topic or theme is presented and discussed. While the event may be followed by a dinner and drinks, the consumption of alcohol is in no way essential to the business of the gathering. A round of drinks may be something for participants to look forward to after the hard intellectual work is over, but to arrive at the session inebriated (or to imbibe over the course of the event) would mark a person as unfit or incapacitated for the central activity of the symposium, which requires a clear head and focused attention. At a properly staffed symposium, an obviously inebriated participant might well be escorted discretely to the door or otherwise excluded from the proceedings.

Not so in the original symposium, which was a familiar cultural institution in many city states in Classical Greece, with a long afterlife in the Hellenistic period. This all-male affair was an after-dinner drinking party (sumposion), in which participants reclining on couches passed around a kratēr of wine mixed with water (drinking unmixed wine was for barbarians). The drinkers sang songs, conversed, and were perhaps entertained by musicians, dancers, and prostitutes. Inebriation was the norm and the conduct often bawdy, but there was at least nominally an order to the proceedings, with one of the participants in charge, and the drinkers having to wait their turn to speak. A very refined version of such a gathering is depicted in Plato’s Symposium, where the participants, hungover from the heavy drinking of the night before, agree to drink more moderately, dismiss the flute girl, and take turns offering speeches in praise of love—although by the end of the night, after the arrival of Alcibiades, the conduct has reverted to the norm, and Socrates has drunk all the other participants under the table. In Xenophon’s Symposium, Socrates offers to dance for the company after the professional entertainers have finished their show.

Symposium, by Nikias Painter. CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Symposium, by Nikias Painter. CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.Two modern descendants of the Greek sumposion preserve very different features of the original institution. The symposium familiar to the modern academic has dispensed with the drinking and aspires to the intellectual refinement proposed in Plato’s Symposium. The Passover Seder (its unlikely cousin) has preserved the ritual drinking, the reclining posture of the participants, and the orderly progression of activities. In the territories conquered by Alexander the Great, which included the land of the Israelites, the sumposion was the epitome of leisured entertainment among the ruling classes, and so became the model for the conduct of a very special occasion. (The more oppressive side of the imposition of Greek cultural norms on the conquered peoples is the background to the Chanukah story).

A reader of Plato’s Symposium might suppose that the modern academic symposium adheres more closely to Plato’s aspirations for the sumposion than the Passover seder does. However, Plato’s last dialogue, Laws, indicates quite the contrary. Here we find the Athenian spokesperson defending the sumposion against objections from a Cretan and a Spartan, who live in cities where the institution is banned. It is the drunkenness involved in a sumposion to which these interlocutors object and it is specifically the drunkenness that the Athenian insists is crucial to its function. The sumposion, he explains, is a forum for the transmission and preservation of cultural norms, and the drunkenness of the participants (especially the older ones) plays the important role of “softening them up,” making them receptive to the norms and narratives conveyed in the songs sung and stories told over the evening. A properly conducted sumposion, he claims, educates the ethical and cultural sensibilities of its participants, and cultivates their sense of community. Plato’s proposal is that communal drinking (the literal meaning of sumposion, captured also in the Latin root for ‘convivial’) is an effective facilitator of this important social benefit—provided it is restricted to those over thirty years of age!

Featured image: ‘Plato’s Symposium’, by Anselm Feuerbach. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Seders, symposiums, and drinking parties appeared first on OUPblog.

October 30, 2015

What were Tampa’s top Twitter debates at #OHA2015?

Some of you open a can of soup and tweet about it, others of us would never know about your tweet since we don’t use Twitter. Others at this year’s Oral History Association annual meeting put their phones away for a second to do what they do best: listen. Although the conversation continued in between sessions and into the evenings in quips of 140 characters, we worried that it was buried underneath the huge volume of tweets and retweets. Whether polite or Luddite, many oral historians missed debates to which they contribute offline with thought and authority. Here’s your chance to catch up and weigh in on the top five Tampa Twitter debates.

What are the implications of oral history in “real-time?” Are people with smart phones the new oral historians?

This question has enormous implications for oral historians, radicals, activists, journalists, and public historians. In her Friday presentation on documenting Ferguson and new social movements, Nailah Summers asserted, “History isn’t just being written by historians. It’s everyone with a smartphone now.” The discussion began right then and there: do historians have a special place in this movement? Or do they and their privilege need to take a step back? Do activists reliant on technologies disempower those without it?

What do we do to make our work more accessible and organized?

Twitter master Doug Boyd, librarians from small communities and big universities, and many others led us through sessions about OHMS, metadata, old tapes, and new platforms. Every new solution produces a thousand more questions. Are we all— with varying resources, manpower, and skills—on the same page? If you check Twitter, you’ll find a bucketful of thoughts, retweets, and very few answers.

Is the recent IRB recommendation from the Department of Health and Human Services a sign of good things to come?

Most of you seem to think so, but there are some doubts out there about maintaining accountability. Read more in Donald Ritchie’s wonderful post.

Speaking of accountability, how do we address the race, class, and gender divisions inside our own field?

Image courtesy of author.

Image courtesy of author.This is an awkward dilemma oftentimes answered behind the scenes by academe. Oral history’s position as “the voice of the people” is fragile and dependent in part on mutual accountability and self-policing. Did you notice that the sessions you attended exposed you to new conversations, or rehashed old ones? Is the phenomenon of an all-female audience in a panel on women’s stories a healthy breakdown of scholars into subfields, or are we constructing a wall between scholars on the same side? With so many speakers who emphasize intersectionality and boundary-crossing alliances, we should know by now that these are issues that concern us all. What do you think?

Where’s the line between oral history and public history, and what’s their relationship to one another?

Phew, this is a big one. With goals of public accessibility at the center of many cutting edge projects, the line between public history and oral history seems fuzzy. How are their respective missions different from one another with concern for disseminating knowledge at the core of both? The hierarchy between “academic” and “nonacademic” historians complicates feelings and conversations further. Both public and oral historians seem far from consensus on which is a subfield of which or where these overlap, but the presence of public historians in an OHA discussion is encouraging.

A warm thanks to those who tweeted from their panels, planes, dinner tables and hotel bathrooms – and to those who listened to your comrades’ concerns. Social media may not be the answer to our academic and societal problems, but Twitter helps us reach others near and far who share our battles.

Image Credit: “We don’t realize” by Ed Yourdon. CC BY NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What were Tampa’s top Twitter debates at #OHA2015? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers