Oxford University Press's Blog, page 600

October 23, 2015

Biophilia: technology that transforms music education

In today’s society, technology is fundamentally embedded in the everyday learning environments of children. The development of educative interactive apps is constantly increasing, and this is undoubtedly true for apps designed to facilitate musical development. So much so that computer-based technology has become an integral part of children’s musical lives, with music apps as present in their musical development as pencils and paper. One artist who not only intimately understands this evolution, but also knows how to harness its potential, is Icelandic singer/songwriter Björk.

In 2011, Björk released a concept album entitled Biophilia, presented as the first ‘app album’ ever to be released. It has subsequently made its way into the Museum of Modern Art, New York, as the museum’s first downloadable app in its permanent collection. Four years in the making, Biophilia explores the intersection between music, nature, and technology, with each of the ten songs on the album connected to its accompanying app, linking the song’s theme to a particular musicological concept. In an attempt to redefine how music is made in the 21st century, the ultimate aim of the Biophilia project was to develop a way of making music that is more intuitive and accessible than traditional academic approaches to music education.

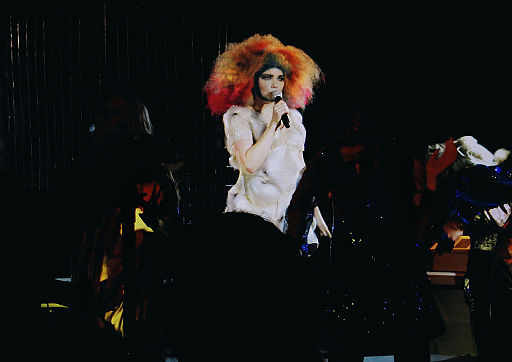

Björk performing at Cirque en Chantier. Photo by Rlef89. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Björk performing at Cirque en Chantier. Photo by Rlef89. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia CommonsThe Biophilia project became the subject of a 2013 documentary entitled When Björk Met Attenborough, originally produced for and aired on Channel 4. During this interview, Björk explains that her quest to transform the way we understand music originated in her own childhood struggles with her classical music training:

“When I was in music school, when I was a kid, there were a lot of things that rubbed me the wrong way. It was hard for me to connect with, being in Iceland, and we were basically getting curriculums from Europe, based on 17th century German classical music. As much as I adore that, but at that time I wanted to connect more with Iceland. And also just how it had become really academic, and was removed from the physical.”

Björk argues that an overly academic approach to music education can be an obstacle to the intuitive act of music-making, particularly among children. This sentiment is echoed during the documentary by the celebrated neurologist, Oliver Sacks: “With the music we have now, there’s something intimidating…if there was some way of drawing anyone into acting with music or creating their own music, I think that would be extraordinary.” To counterbalance the historical approach, Björk harnessed 21st century technology to invent a new means of visualizing sound, providing children with novel resources to explore the ways in which music works.

The apps contained in Biophilia take our intuitive understanding of natural phenomena as a foundation, on which new and novel explanations of musical principles are constructed. They can be categorized as functioning either like conventional video games, or musical instruments. “Mutual Core” is a video game that sets out to explore the theory of chords, by allowing the user to arrange geological layers that can then be played, much like a piano accordion. Chordal tension is illustrated through the differing strata, while the user tries to unite two detached hemispheres, driven apart by energy.

Screenshot from a tutorial of the Mutual Core app, via Bjork on Youtube.com

Screenshot from a tutorial of the Mutual Core app, via Bjork on Youtube.com“Thunderbolt” works more like an instrument, where tapping on the screen generates electrical sparks, and using two or more fingers at the same time produces arpeggios. These arpeggios can be played as backup to Björk’s same-titled song, or independently. The idea behind this app was to depict arpeggios to children in the simplest of manners.

Screenshot from a tutorial of the Thunderbolt app, via Bjork on Youtube.com

Screenshot from a tutorial of the Thunderbolt app, via Bjork on Youtube.comBjörk and her team of computer programmers set out to modify the visual representation of music, with the hope of revolutionizing the way children think about and create music. Biophilia is now a standard part of Iceland’s music curriculum, and several successful music workshops for children have been held around the world. Ultimately, what is incontestable is that children must be encouraged to create their own music–that through experimentation and exploration they can form their own aesthetic judgments. In this respect, music apps like those showcased in the Biophilia project must be applauded and adopted as essential tools in a child’s musical education.

Featured image: Music Class USA. Photo by 인호 조 (Sungmin Yun). CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Biophilia: technology that transforms music education appeared first on OUPblog.

Why know any algebra?

A recent meme circulating on the internet mocked a US government programme (ObamaCare) saying that its introduction cost $360 million when there were only 317 million people in the entire country. It then posed the rhetorical question: “Why not just give everyone a million dollars instead?”

It may have been a joke but some nevertheless found this argument compelling. Their mistake was quickly pointed out – to give everyone a million dollars would cost 317 million million dollars – but some persisted with the error. Their reasoning seemed to go “if you have 360 dollars you can give 317 people one dollar each so if you have 360 million dollars you can give 317 million people a million dollars each!” Others explained: “No Joe, just imagine you have 360 boxes, each containing a million dollars cash. When you go to give each person one of them you will run out after 360 people, leaving the remaining 316,999,640 people empty handed.”

Everyone would agree that adults need to have a grasp of numbers to the extent that they can spot nonsense arguments like this. At the same time however, it may be said that the x and y stuff can safely be forgotten once you leave school as it is practically never used. Anyone will forget the details of any subject if they never go back to it. That is why occasional reading about things mathematical renews confidence and allows you to question what is going on when a topic becomes complex.

For instance, it will give you the power to ask killer questions in pretentious presentations. Often a couple of graphs and equations flashed up on the screen will cower an audience into submissive silence. Never put up with that. Ask the presenter how that equation relates to the topic of their talk. Better still, ask what each of the symbols in the slide stand for. You don’t need to know anything in particular about maths to do that and everyone will soon see how competent your presenter is.

Taking this a little further, it is genuinely useful to know some algebra as it lets you deal with simple mathematical problems and to know that you have them right. And this does happen in real life. A friend once gave a presentation pitch for a contract that involved two factors whose graph was a straight line. He laboured to explain this and an audience member lost patience and pointed out that the two quantities had an obvious linear relationship so of course the graph had to be a perfect straight line. My friend was made to look clueless and, not surprisingly, failed to land the contract. He explained to me later that what most annoyed him was that he had figured that out the night before, and had even written down the equation of the line and

checked it was right. However, he lacked the nerve to say that in his presentation and so when it was pointed out to him, he looked stupid. With just a touch more algebraic confidence he could have carried the day.

It is a worthwhile skill just to be able to see an algebraic problem for what it is even if your own attempts to solve it are a bit clumsy. A recent example concerned the controversial film The Interview, which is about a fictional assassination plot of the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un. A magazine article said that the film grossed $15 million on the weekend of its release, that the cost of the movie was $15 to buy and $6 to rent, and that two million copies were distributed overall. The article went on to say however that the company did not state how many copies were rented and how many were bought. It seemed that it did not occur to anyone at the magazine that they ought to be able to figure that out. A person with some mathematical habits of mind however would at least pause to think, and then would get the answer somehow, as it is not difficult. Working in units of millions there are two equations here: r + s = 2 and 6r + 15s = 15; the first equation counts units of r (rentals) and s (sales) while the second equation counts the money. From these we may deduce that there were 1/3 million sales and 5/3 million rentals overall. (Google simultaneous equations for further details.)

“I have a dream, which is that people will not run for cover whenever anything mathematical appears but rather will pause, think a little, ask a question or two and, if still out of their depth, seek a more qualified person to clear the matter up.”

The most salutory experiences of harm caused by mathematical ignorance however often stem from probability questions, which can fool even intelligent and educated people. It is one thing not to be able to do a problem but it is quite another to imagine that you can do it and be seduced into an utterly false conclusion. As an example, the following question was put to a large group of medical students. A certain condition affects one person in 1,000 and a particular medical test will certainly give a positive result if the person tested has the disease but has a 5% probability of coming out positive for people who have not got the condition. A randomly chosen person tests positive. What is the probability that they have the disease?

The most popular response was that the test was 95% accurate so the probability that it was right was 95%. I’m afraid that answer is not only wrong but represents a mistake on a par with poor Joe’s analysis of the cost of ObamaCare. The correct answer is at the other end of the scale: the chance that the person actually has the condition is less than 2%.

This is a tricky question and even a mathematically aware person might find it difficult to answer. However, I hope that the same person would instinctively be sceptical of the guess of 95% as that number takes no account of the prevalence of the condition in the population, which surely affects the answer. If the condition were very rare, then the chances of a false positive must be high. A quick way to see the right answer is to note that for every 1000 people in the general population, one person will have the condition but about 50 (5% of 1, 000) will be patients who generate a false positive; for that reason a random positive test only has a chance of one in fifty-one of detecting a person with the disease.

We might hope that qualified doctors would know how to interpret any test results that they call for. However, bad mistakes may still happen in serious situations such as court cases where an ‘expert’ witness makes a probability statement. Landmark cases involving cot deaths have led to gross miscarriages of justice. For example, once a probability statement on the likelihood of DNA matches is accepted as fact by the court, there may be only one verdict possible, and that may be the wrong one. I trust that lessons have been learnt from past errors but the risk of blunders remains unless any statement of probability is checked by a qualified statistician. Being an expert in the field of the testimony is not enough. Before a precise probability claim is admitted as evidence, it should be professionally scrutinised with the underlying assumptions, the calculation of the actual probability number and, just as importantly, its margin of error, all checked. I am not sure that would necessarily happen in a British law court.

In conclusion, I have a dream, which is that people will not run for cover whenever anything mathematical appears but rather will pause, think a little, ask a question or two and, if still out of their depth, seek a more qualified person to clear the matter up. It is a modest sounding dream but its realisation would make the world a better place.

Featured image credit: Maths and calculator. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Why know any algebra? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 22, 2015

In search of Thomas Smith Grimké’s portrait

Most biographers would agree that it is difficult to write about someone whose face you have never seen. When I set out to write a biographical entry on Thomas Smith Grimké (1786-1834) for the American National Biography Online, I confronted that challenge. Then I learned that the editors at ANB wanted an image too. Now I had two reasons to find one.

Thomas Smith Grimké was certainly wealthy enough, and for that matter prominent enough, to have a portrait done. The son of a South Carolina state judge and the brother of Charleston’s famous abolitionists Sarah and Angelina Grimké, Thomas was an accomplished lawyer, state legislator, orator, and reformer. In his speeches (which he frequently arranged to have printed as pamphlets and sent to prominent citizens and libraries around the country), he advocated for educational innovation, temperance, and peace. He also led the Unionist side in South Carolina’s intense debate over the state’s right to nullify a federal law (foreshadowing the Civil War to come) and corresponded with James Madison on the history of the Constitutional Convention. Though a Southerner, he was most famous in the North, and, though a slaveowner, he might have—or so his sisters later believed—become an abolitionist if he had not died of cholera at the age of 48, while in Ohio on a lecture tour.

Thomas Smith Grimke portrait in Miami University Art Museum’s collection. Used with permission.

Thomas Smith Grimke portrait in Miami University Art Museum’s collection. Used with permission.Though it was possible that the only portrait of Thomas might be in private hands and therefore difficult to locate, I hoped I would come across a publicly accessible image while doing research for the entry. And I did. In 1924, a historian who specialized in Ohio history published an essay about Grimké in The Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly. Underneath a picture of Thomas were the words, “From a photograph of a painting in the Library of Miami University.” Bingo!

And it made sense. I already knew that Grimké, while on his lecture tour, had given a speech to a student literary society at Miami University of Ohio. According to the 1924 essay, the painting had been commissioned by the society to commemorate his inspiring visit. Learning that the painting was now at the university’s art museum, I spoke with the director, Dr. Robert Wicks, who said he would be happy to show it to me. Luckily, I was already planning to drive from Chicago, where I live, to Charleston, South Carolina to do research on the biography I am writing about the Grimké sisters. I decided to swing by Miami University on my way home.

Thus I found myself one day in October 2014 standing with Dr. Wicks in front of a large and fascinating portrait of Thomas Smith Grimké. The first thing I noticed was that this was not the traditional image of a forceful, successful man. Grimké had a kind face. In capturing this, the artist had done well. I had read enough obituaries by then to know that Grimké was much beloved for his gentle spirit. Now I could see it.

Etching by Doolittle and Munson. Copy from the Indiana Historical Society collection, public domain.

Etching by Doolittle and Munson. Copy from the Indiana Historical Society collection, public domain.I also noticed that his collar and his cravat were askew, as if he was too distracted to pay much attention to his appearance. Fascinatingly enough, this too fit with what I had read in the obituaries. Though a very wealthy man, he was famous in Charleston for walking down the street looking quite disheveled. Just as I had hoped, the picture brought the man to life for me and hopefully it would do the same for readers.

But who was the artist? Dr. Wicks told me this was a mystery since the painting was unsigned front and back. We then looked in the painting’s “object file” to see if I could learn more about when the portrait was painted and, to our surprised delight, found a $25 receipt signed by the artist, Abraham G. D. Tuthill, an itinerant painter. The receipt, it turned out, had found its way into the file in the 1980s, long after the museum had concluded the artist was unknown. The official records had just not been undated.

A few weeks later I located in the general print collections of the Indiana Historical Society an etching of Grimké based on the same painting. But here is what is interesting. While the painting shows Grimké as a tender soul, the etching does not. Doolittle and Munson, early Cincinnati engravers, had enhanced the squareness of his jaw and given his mouth a new firmness. They also straightened his collar a little. Thus does culture insist on tidying up the truth to conform to its own expectations! So I am very glad I have an image of the painting itself, and that Abraham G. D. Tuthill was a good enough artist to accurately capture the character of Thomas Smith Grimké. And I am especially glad to share the fruits of my search with the readers of the ANB.

Image Credit: “Charleston, 1865.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post In search of Thomas Smith Grimké’s portrait appeared first on OUPblog.

Place of the Year 2015: behind the longlist

You don’t need to follow the news too closely to know that 2015 has been a roller coaster of a year. Last week we announced our longlist for Place of the Year 2015, but since then some of you have been asking, “why is x included?”, or “why is y worth our attention?” After careful consideration our Place of the Year committee selects from a rather large pool of nominations, but rest assured that we’ve got our ears to the ground and will do our best to represent the world (and beyond) in 2015. With that, we go behind the longlist and invite you to give your comments on additional reasons why each nomination belongs or not.

Cuba

This past August, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry visited Cuba after Pope Francis and the Vatican urge the US and Cuba to repair diplomatic relations. This comes after a 54-year embargo first imposed by the U.S. when Fidel Castro seized power.

Secretary Kerry Looks Out From the Veranda of Finca Vigia in Cuba. Photo by U.S. Department of State. Public Domain via Flickr.

Greece

Greece faced an economic crisis mid-year after failing to make a loan payment to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and nearly rejected the bailout referendum put forth by their eurozone creditors. In the second half of the year, Greece is placed back on the map as hundreds of thousands of migrants fleeing from Syria bottleneck through its shores and smaller islands such as Lesbos (Lesvos), Kos, Samos, and Leros.

Photo by International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 via Flickr.

Iran

Just this past week, after months of diplomatic efforts, Iran’s supreme leader approved of the nuclear deal between Iran and six major world powers: the US, Britain, France, China, Russia, and Germany. This agreement intends to mitigate the risk that Iran could fuel a nuclear weapon with its large uranium stockpile and uranium enrichment equipment. In exchange, sanctions hindering Iran’s economy and finances will be lifted.

Photo by IAEA Imagebank. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Nepal

In late April of this year, Nepal experienced one of its worst natural disasters since 1934. Also known as the Gorkha earthquake, its magnitude recorded at 7.8 on the Richter scale. Over 9,000 people were killed, leaving another 23,000 injured and hundreds of thousands homeless. Yet another earthquake was recorded mid-May with a magnitude of 7.3, killing another 200 and leaving 2,500 injured.

Bhaktapur, Nepal Earthquake Destruction. Photo by Natalie Hawwa for USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development). CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr.

Nigeria

The Boko Haram insurgency escalated in Nigeria early January after the Baga massacre, in which the extremist group’s militants razed Baga and killed 2,000 people. Violent attacks by the group on the Nigerian people and government continue, ever increasing in intensity and frequency.

NIGERIA-UNREST. Photo by Diariocritico de Venezuela. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

North Korea

North Korea revives the threat of utilizing nuclear weapons against the U.S. The country is now pushing for the U.S. to engage in peace treaty negotiations; if they refuse, North Korea says it will continue expanding its nuclear weapons program.

North Korean Nuclear Reactor Construction Site. Image taken by Wapster. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Palmyra, Syria

Extremist group ISIS seizes control of Palmyra from the Syrian government in May. Their destruction of culturally significant architecture — including the Temple of Bel, the Temple of Baalshamin, and the Triumphal Arches — and artifacts could be seen as an attempt to erase Syria’s diverse history.

Palmyra, Temple of Bel. Photo by Arian Zwegers. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Paris, France

Two men who self-identified as part of the terrorist group Al-Qaeda killed 12 people and injured 11 others when they forced their way into the offices of French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo. The resulting phrase from the attack, “Je suis Charlie”, was adopted by participants of subsequent rallies and advocates of freedom of speech and freedom of the press.

Je_suis_Charlie-7. Photo by Valentina Calà. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Pluto

The first detailed satellite images of Pluto from the New Horizons space probe launched back in 2006 are sent back to Earth. The most endearing characteristic of the dwarf planet is the relatively featureless heart shape that measures approximately 1,000 miles across.

New Horizons Flyby of Pluto. Image by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Spratly Islands

Ownership of the Spratly Islands, located in the South China Sea, is in current dispute among Brunei, China, Malaysia, Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. The area has an abundant amount of resources including oil, natural gas, and fish, and is one of the busiest areas in terms of the amount of ships passing through.

Photo by Image Science and Analysis Laboratory, NASA-Johnson Space Center. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Don’t forget to cast your vote on the longlist by 31 October:

Place of the Year 2015 longlist

Keep checking back on the OUPblog, or follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr for regular updates and content on our Place of the Year 2015 contenders.

Headline image credit: Photo by markus53. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Place of the Year 2015: behind the longlist appeared first on OUPblog.

Ethics at the chocolate factory

Two women are being trained for work on a factory assembly line. As products arrive on a conveyor belt, their task is to wrap each product and place it back on the belt. Their supervisor warns them that failing to wrap even one product is a firing offense, but once they get started, the work seems easy. Then the belt speeds up.

Recognize the scene? Lucy and Ethel at the chocolate factory is a classic episode from the 1950s television program I Love Lucy. It is also a good illustration of how people make rapid judgments in response to changing conditions at work, devising workarounds – shortcuts, fixes, patches – to bridge the gap between the rules of work and what’s actually happening. When I give talks, usually to physicians, nurses, and other health workers, about the ethics of workarounds, I often use this clip from I Love Lucy, in part because it’s fun to have four minutes of nonstop laughter during an ethics lecture, but mostly because it shows how workarounds happen.

Thanks to research from cognitive neuroscience and behavioral psychology, synthesized by Daniel Kahneman and others, we now understand that ‘fast’, instinctive thinking and ‘slow’, reasoned thinking are both part of how we think, and that fast thinking occurs so quickly that we may not recognize what’s going on, or that we’re ruling out options as we make choices under pressure. When Lucy and Ethel notice that the conveyor belt has sped up and that unwrapped chocolates are sliding past them, putting them at risk of being fired, they devise a workaround: grabbing the chocolates off the belt, and eating them, or hiding them under their hats or in their bras. What option do they rule out, or fail to see? They don’t open the door marked ‘Kitchen’, where the chocolates are coming from, to find out if the belt is malfunctioning. They react to what is directly in front of them. There is a short-term reward for their ingenuity: when the supervisor comes back, having stopped the belt for an inspection, she praises Lucy and Ethel. Deciding that these ‘fine’ workers are capable of even greater productivity, she orders the unseen belt operator to “speed it up a little!” Their doom is sealed.

Image credit: Tennessee Ernie Ford and Lucille Ball from an episode of I Love Lucy by Bureau of Industrial Service. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Tennessee Ernie Ford and Lucille Ball from an episode of I Love Lucy by Bureau of Industrial Service. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s ‘social intuitionist’ model of how people make fast, intuitive moral judgments and then persuade others that these judgments are correct, reinforcing the first person’s intuition, helps to explain what’s going on at the chocolate factory and in other work places. (See Chapter Two of Haidt’s book The Righteous Mind for a useful diagram of the social intuitionist model.) An event – here, the belt speeding up – triggers an intuition that the rules they’ve been given no longer work (“Listen, Ethel, I think we’re fighting a losing game!”) Next comes a judgment about the right thing to do: devise a workaround. Lucy and Ethel never even get to the next step of Haidt’s model – coming up with post-hoc reasons to justify their quick judgment – as they persuade each other, by their actions, that what they’re doing must the right thing to do.

Health care workers frequently describe powerful moral intuitions (what we’re doing to this patient is harmful, or unfair, or simply, doing this feels wrong) that arise amid the constant pressures to manage the flow, get the job done, do more with less, and keep the customer satisfied. Peter Ubel has proposed that Haidt’s model should be applied to ethics education in medical schools; less about moral principles, more about moral psychology. Ubel, a physician and behavioral scientist, is not arguing that principles and other rules aren’t important, but rather that – like Lucy and Ethel in the chocolate factory – health care professionals will confront situations that don’t fit the rules, and will, because of how thinking works, tend to make quick judgments, devise quick fixes to accommodate problems, and look to their peers for reinforcement. Remembering that Lucy and Ethel’s fix looked fine to their boss, who rewarded them by making their job even more of a losing game, we also need to apply these insights to organizational ethics.

Feature image credit: Logistics stock transport shipping by falco. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Ethics at the chocolate factory appeared first on OUPblog.

A brief history of European opera

In 1598, Jacopo Peri’s Dafne premiered in Florence. It is widely considered to be the first opera, that genre of classical music in which a dramatic work is set to music. Over the last 400 years it has evolved into numerous different art forms, from the ballad opera of the eighteenth century to the musical theatre of today, and influenced other genres, from Mahler’s cantatas to the ragtime music of the early 20th century. Great works of literature and legend inspired some of the greatest composers, singers, and instrumentalists of their time. We’ve pulled together a brief timeline of pivotal moments in opera history from the international impact of Monteverdi’s Orfeo to how technology has changed opera’s sound.

Information on events in the history of opera in the timeline above are sourced from Oxford Scholarship Online, Oxford Music Online, relevant book chapters, blog articles, and journal articles. Follow the links in each timeline entry to learn more about the subject.

Is there a milestone missing? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Featured image: Marco Ricci – ‘Rehearsal of an Opera’, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post A brief history of European opera appeared first on OUPblog.

Keep the bike but look under the helmet: when Orwell met Corbyn on Upper Street

Many people fear that Jeremy Corbyn’s election as leader will throw Labour into a policy war so long drawn out that it will end up in the zombie world of the undead and unelectable (like the Liberal Democrats). Corbyn has already been subjected to unfavourable comparisons with previous Labour leaders but in truth he is incomparable. Never before has someone just wandered in from the street, as it were, and been crowned. Only 20 MPs support him but party activists love him and it is clear he is capable of reaching the parts other politicians cannot reach – particularly the young. New Labour doesn’t know how to take him on. The Tories don’t know whether to take him on. The press – all the press, not just The Guardian – search for some sort of benchmark. This being an English party now, it’s only a matter of time before George Orwell is brought in to see how Jeremy measures up.

Orwell spent half his life caught between his hatred of ideology and his belief in socialism. As a socialist he felt he was obliged to support the working-class (aka “The People”), and even like them, and believe in them. As an Old Etonian middle-class socialist however, he knew that liking and believing in the exploited class meant not liking, and not believing in, his own class and that, in some visceral way, meant not liking or believing in himself (a tolerable position perhaps for a writer but absolutely impossible in every other respect). Orwell was convinced, therefore, that all middle-class socialists must be hiding something. Which is to say, he saw left intellectuals as in hoc to socialism as an ideology – not their own true feelings – and ideology, as everyone knows, is about power. Lest we forget, INGSOC was a party of left intellectuals.

If he couldn’t abolish himself, and he couldn’t be ideological, Orwell’s way out was to invoke a deeply English middle-class sense of personal duty to the poor and underprivileged. ‘Politics’ therefore was something he elected to do on their behalf; writing about it was his art. His cultural writing was warm and original. He found his best subject in the English people. His political writing, on the other hand, could be cold and brutal, especially when he sensed the lies behind the ideology, as he did in Burma and Spain.

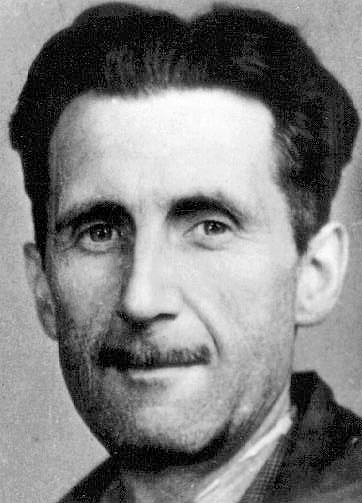

Picture of George Orwell which appears in an old accreditation for the BNUJ (Branch of the National Union of Journalists). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Picture of George Orwell which appears in an old accreditation for the BNUJ (Branch of the National Union of Journalists). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.So how does Jeremy measure up to Orwell? To begin with, the two men have more in common than a posh school and no degree. Apart from their obvious points of resemblance – from anti-colonialism and anti-war to bikes and allotments – both men believed in the power of the state to make life more agreeable for the majority. And although commentators will find in Orwell things to throw at Corbyn to make him look like a crank, the truth is, should they have met on Upper Street one bright Saturday morning and gone for a latte, there is much in one that the other would have warmed to.

Except, of course, that the Labour leader is indisputably a middle-class socialist, and to put it mildly, Corbyn is not the least ideological of MPs. The sheer global range of his ‘positions’ on this and that and everywhere suggests an ideological rather than a sceptical frame of mind – a man who gives the impression of someone not used to real debate and knowing what he thinks even before he thinks it. He uses the 250,000 who voted for him, rhetorically, like a Leninist stick against all those in the party who disagree with him, particularly the MPs. We have yet to see whether he will turn that virtual army into a cadre inside the party. And yet, in spite of Corbyn’s old Trotskyite friends, Orwell could not have helped noticing how easily the Labour leader mixes on the street and, far from being the sort of deracinated left intellectual that gave Orwell “the creeps”, and made him “sick”, that he has represented and lived in his constituency for over thirty years. Anyone who rides a bike round London is not trying to hide from anybody.

But what does he keep under his helmet? Corbyn, for all his ordinariness, is the high priest of “What Is Universally True”. In a long tradition of the platform in these islands, he is against all that is “wrong” and in favour of all that is “true” before seconding the motion. But what then? What about actual workable sustainable realistic coherent government? Robbing Peter to half pay Paul might mean the premium falls on Petra not Peter. Helping one set of people may be at the expense of another equally deserving set of people. Grabbing the levers of state might not get you what you want because the state is itself a variable. Punishing the financial sector is one thing; what do you do when the markets move against you is another.

At which point Jeremy’s International Socialism springs to mind – the perfect partner for the “What Is Universally True” Party. One doesn’t expect to look under Jeremy’s helmet and find Anne Hathaway’s Cottage or Danny Boyle’s Isles of Wonder, but the man never shows much sympathy for the history and culture of his own country except as a testing ground for human rights. Indeed, unlike Orwell he never shows much political interest in history and culture generally. His Brighton speech made literary reference to Okri and Angelou, but only as bolt-ons and after-thoughts (“that man’s a genius”).

Corbyn won the Labour leadership but if he is going to win the country he is going to have to keep the bike and look again under the helmet. Above all, he is going to have to make connections with his own party and the British people that might make for disconnections with himself which, for a man who hasn’t changed his mind in 40 years, is not going to be easy. What is more, he hasn’t got much time. Electoral failure in May will see the sharpening of the knives. Electoral success will see panic over what to think next. He may even have to read some Orwell.

The political future suddenly looks interesting.

Featured image credit: Big Ben. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Keep the bike but look under the helmet: when Orwell met Corbyn on Upper Street appeared first on OUPblog.

October 21, 2015

The “Bottom” Line

As promised in the previous post, I am going from body to bottom. No one attacked my risky etymology of body. Perhaps no one was sufficiently interested, or (much more likely) the stalwarts of the etymological establishment don’t read this blog and have no idea that a week ago a mine was planted under one of their theories. When Dickens’s character Martin Chuzzlewit came to the United States, in New York he met a newspaper editor who didn’t doubt that Queen Victoria began every morning with reading what he had written the day before about Great Britain (it always was vituperation). Martin’s polite attempt to reassure the man was met with contemptuous disbelief. Unlike that editor, I have no illusions about the favorite reading of the greats but will proceed in the belief that no spoken or written word is lost without a trace. Unfortunately, the time between the sowing and “gleaning” may sometimes be too long.

Unlike body, which all dictionaries unanimously call a word of unknown origin, bottom looks deceptively transparent. Old Engl. botm (or boþm; þ was pronounced as th in Engl. thin) “valley” (note the meaning) has cognates in the other Germanic languages: Icelandic botn, Modern German Boden (it means “floor; ground; soil; earth; land”), Dutch bodem, and so forth. Within Germanic, only German Bühne “stage” (originally, “wooden structure”) may be related. More secure related forms have been recorded in Sanskrit, Greek, Celtic, and Latin, though Latin fundus (whose root is seen in Engl. foundation and the verb to found) has been explained as an alteration of fudnus, which it may well be. Unexpectedly, in the Old Germanic words bot– alternated with bod–, as also evidenced in an indirect way by Old Engl. botm ~ boþm, and the existence of two variants—one with t, and one with d—has bothered etymologists for decades. However, I’ll ignore this difficulty and confine myself to saying that years of involved speculation resulted in a rather unexciting conclusion; apparently, the word always had two variants. The subject of this essay will be not the phonetic shape but the etymology of bottom. What were the original connotations of bot– or bod-?

Here is somebody who even amidst a crazy midsummer night’s dream could get to the bottom of things.

Here is somebody who even amidst a crazy midsummer night’s dream could get to the bottom of things.It has been suggested that the initial meaning of our word was “land; earth,” but this suggestion is self-serving: it allowed researchers to trace bottom to the root of Latin fui “I was” and fieri “to become” and to move from “become” to “grow.” Yet it is more likely that in the remote past bottom referred first and foremost to the sea bottom, valleys, and all kinds of foundation. To make the next precarious step in this valley, we should now move to Slavic and Baltic. The Slavic for “bottom” is dno (so in Russian and Polish; in the other languages the forms are nearly the same). Its Proto-Slavic etymon was d’’bno (the double apostrophe stands for an ancient reduced vowel), as is made clear by Latvian dubens “bottom,” Lithuanian dubùs “deep,” and many other similar forms. Dub-ùs is related to Engl. deep, Gothic diup-s, etc., whose Germanic root was deop-. It follows that dno and its cognates meant “a deep place,” which accords perfectly with “valley” and “sea bottom.” If we look at d”b– (as in Proto-Slavic), we will notice that it is the mirror image of bod– (as, for example, in German Boden), with d-b versus b-d. It occurred to etymologists long ago that the sequence d-b is original, while elsewhere it had been reversed (the first to say so was Joseph Vendryes, an eminent and very cautious scholar). Naturally, this hypothesis cannot be proved, but one understands its appeal: the sense of b-d evades us, while the sequence d-b reflects the idea of depth, as in deep.

There has been at least one more attempt to explain the origin of bottom ~ boden ~ botn. Today few people remember the name of the Swiss linguist Wilhelm Oehl. He wrote relatively little, but in the first third of the twentieth century his articles and his little book about words for babbling were referred to in the best works by historical linguists. He also served as Rector (President) of Freiburg University in Switzerland. Oehl had what one can call an agenda (a polite synonym for a bee in the bonnet), a stimulating but dangerous thing in scholarship. In his opinion, hundreds of words we still use were coined as sound symbolic or sound-imitating formations. He showed little interest in Indo-European roots for, according to his idea, words arise, live for a certain time, and disappear, to be replaced by new words of the same structure. The impulse for their creation, he explained, remains the same forever. That is why he compared numerous words in unrelated languages, and it should be admitted that, bee or no bee, his lists are impressive. But he often saw light where few others could detect it. Like all those who deal with roots, he tended to switch consonants, substitute one consonant for another, and in the end get what he was looking for. Sound correspondences in the traditional sense of this term did not bother him, but, since he was a knowledgeable philologist, he managed to avoid the absurdities that taint most theories of deriving all words of all languages from a small number of sound complexes. His works are interesting and instructive, regardless of the plausibility of each detail.

A triumph of globalization: sound symbolism without borders.

A triumph of globalization: sound symbolism without borders.Oehl compared bottom with Greek tópos “place” and Slavic pod “the foundation of the hearth, etc.” He looked on the complexes bod, top, and pod as evoking the idea of stuffing (filling, ramming). This etymology is not too persuasive, but the congeners of pod do have meanings fully corresponding to that of bottom. The Czech form means “soil, ground,” and next to it we find Latvian pads “floor,” Greek pédon “soil,” and of course Engl. foot. When we encounter the sound groups bod ~ bot, pod, and top next to d-b meaning almost the same, we begin to agree that Oehl might have had a point and that the idea of d-b becoming b-d leads us to some roots purporting to render the idea of “stuffing” (ramming) and thereby producing holes, hollows, and other “deep” things, including valleys. Definitive proof is unavailable. Everything depends on how far we are ready to go in reconstructing the remotest past. I may return to this vexing subject in the post on the word path. Also, I am sure our readers will be gratified to know that Engl. top is a word of questionable origin (despite multiple cognates in Germanic), while pod is almost totally obscure, unless it is one of many words like bud and pudding, with the roots b-d and p-d denoting swelling, with which we are back in the sound symbolic swamp.

Even if Oehl was to a certain extent right, I think we needn’t lump together bottom and body. Assuming that despite the evidence of Slavic and Baltic the original root of bottom was b-d rather than d-b, the old cognates of bottom in so many languages testify to the word’s antiquity, while body, I think, was coined relatively late. However, both words may testify to the validity of Oehl’s general approach; the same sound groups are able, it appears, to arise many times in different parts of the world carrying roughly the same meaning.

Featured image: (1) Baby talk. (c) vinnstock via iStock. (2) Typical tales of fancy, romance, and history from Shakespeare’s plays (1892). The Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The “Bottom” Line appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about failure?

To most of us, good scientific research is often defined by the “eureka” moment – the moment at which a successful result is discovered. We tend to only glorify research that leads us to definite solutions and we tend to only praise the scientists that are responsible for this research. In turn, many of the failures and blunders that precede scientific achievements are overlooked. However, these numerous mistakes and false findings during the pursuit of answers are vital to the learning process and therefore to scientific success. Take the quiz below to find out how much you know about mistakes that led to success. It’s okay to fail!

Feature image: 11-08-09 by Dov Harrington. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Quiz Image: Photo by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post How much do you know about failure? appeared first on OUPblog.

Introducing Martial: Epigrams

Who is ‘Martial’?

Up to this point, Madam, this little book has been written for you. You want to know for whom the bits further in are written? For me. (3.68)

Marcus Valerius Martialis was born some time around AD 40 (we know his birthday, 1st March, but not the year) at Bilbilis in Hispania Tarraconensis, a province of oil- and wine-rich Roman Spain. Spanish fans of ancient literature still tout him as a local boy made good, like his approximate contemporaries Seneca (tragedy) and Lucan (epic). He moved to Rome, where the action was, and spent almost all his adult life there, living off wealthy friends and writing a dozen and more books of witty, satiric epigrams. He died some time in the early years of the second century, around the time his young friend Juvenal was starting to write his famous Satires — poems set in a Rome that’s recognisably straight out of Martial, and that still informs our modern sense of “what it was really like” in the mean streets of the imperial capital.

Why read Martial?

The man you read, the man you want — here he is: Martial, famous all round the world for his gossipy little books of epigrams… (1.1)

Martial is “modern” — everyone says so, whatever here and now they actually inhabit. He’s the poet of the big city, but also an enthusiast for the simple pleasures of country living (provided someone else is paying) — pick and choose from his thousands of epigrams and you can have whatever version of the poet you want. Indeed, early in his Vergil-scaled magnum opus Martial himself ironically concedes that only the hardcore will read him all the way through. The rewards for such an an vid fan, though, are great: Martial reboots epigram as a Roman poetic form on a scale never previously attempted and introduces techniques of structure and internal allusion within and across books — “intratextuality” — that it had never before seen. His poems are often brilliantly satirical (and occasionally, terribly sad) when taken individually, but his twelve-book masterpiece is even more than the sum of those thousand-plus parts.

Medieval manuscript of the Epigrams from 1490. Image Creative Commons via Escarlati

Medieval manuscript of the Epigrams from 1490. Image Creative Commons via EscarlatiWhy this selection?

Sure, you could have borne three hundred epigrams, but then who would bear you, book-roll, and read you from start to finish? (2.1)

For the longest time, Martial was not read as a literary author. As a scabrous, fly-on-the-wall exposé of loose pagan morals — yes. As a school text for the generations of Latin learners who parsed and imitated him in classroom exercises — extensively. As a generic model for the Humanist scholars of the Renaissance and Baroque — ubiquitously. As a repository of archaeological data on lost monuments — frequently and perhaps incautiously. But as the witty presence who animates a complex and ambitious mega-text? That is something relatively new. For a long time academic study of Martial lagged behind that of Roman satire, which lagged behind that of other poetic genres; no-one was in a rush to recuperate a disreputable author with a dirty mouth and a reputation for sycophancy and insincerity (all those epigrams sucking up to Domitian, and then maligning him while he was still warm in his grave). Martial was classical by period, but his perceived bad character kept him marginal to the canon of bona fide Classics, which after all still carried the aura of intellectual and maybe even spiritual uplift; it wouldn’t do to appreciate him as Art: good commentaries, for instance, were a long time coming. Since the late 1990s, though, a new generation of scholarship has begun to recuperate Martial as a serious literary artist who pushed his genre hard and created unique effects, particularly in intratextual connectivity (“cycles” is a key term — recurring characters and motifs that knit the books together, collectively as well as individually) and complex self-presentation.

Translating him when I did, I could take advantage of these insights and aim at a selection that showed off (what many of us now think is) Martial’s bold and innovative agenda for epigram. I couldn’t translate the whole thing — a complete Martial would overflow the bounds of a single-volume paperback — but I could try to make my selections convey a sense of his epigrams as the building-blocks of polyphonous serial fiction on a grand scale. I also aimed at giving an impression of the thematic and tonal range of his material: Martial is the undisputed master of satirical epigram but can also write warmly, gently, and movingly. I was able to translate frankly, a liberty not open to all translators in the past, although since the 1970s we have been able to get away with much more. And I cut myself the slack of not attempting verse. Translators of Martial mostly make him rhyme, and while this preserves the sense of Martial’s epigrams as poetry it tends either to lose nuance (the devil of his satire is in the detail) or pad him out, and often both at once. Martial is not a terribly poetic poet and I don’t think he’d mind.

What’s next?

You are my expert listener… (6.1, to Julius Martial)

Over the next couple of months I’ll be posting my thoughts about particular poems by Martial and doing my best to answer your questions about the poems, their frame of reference, and how I went about translating them. I hope to give you a couple of new translations as well as discussing epigrams from the book. I’m grateful for the opportunity to engage with our (Martial’s and my) readers and I look forward to arguing the toss over this magnificent bastard of a classical author. Let’s keep in touch.

Featured Image: Flavian Amphitheatre, Creative Commons via Pixabay

The post Introducing Martial: Epigrams appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers