Oxford University Press's Blog, page 604

October 15, 2015

How did life on earth begin?

News broke in July 2015 that the Rosetta mission’s Philae lander had discovered 16 ‘carbon and nitrogen-rich’ organic compounds on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The news sparked renewed debates about whether the ‘prebiotic’ chemicals required for producing amino acids and nucleotides – the essential building blocks of all life forms – may have been delivered to Earth by cometary impacts. The argument goes that the shock of an impact may be sufficient to produce these essential life chemicals, so seeding the young Earth with the ingredients required to get life kick-started.

It’s an appealing idea. Estimates of the quantity of prebiotic organic substances available on the primitive Earth are sensitively dependent on assumptions about the nature of Earth’s early atmosphere. However, in one such estimate, a total of one hundred billion kilograms of organic material is thought to have been made available to the primitive Earth each year, of which the dominant source is so-called ‘exogenous delivery’ by comets.

The amount of biomass on Earth today is estimated to be of the order of a million billion kilogrammes of carbon. If these estimates of the amount of available prebiotic organic material are order-of-magnitude correct, then a quantity equal to today’s biomass could have accumulated on the primitive Earth within just ten thousand years.

But delivery is only the beginning, of course. We might suppose that any organic chemicals leaching from the debris of cometary impacts will likely become dispersed in the Earth’s vast oceans, oceans that are being churned by the gravitational influence of a Moon that is much closer than it is today. And, unfortunately, logical next step in the journey to life requires that we string the building blocks together to form long chains, leading eventually to proteins and nucleic acids. This coming together is going to be very difficult if the building blocks are greatly diluted in a large volume of water.

Now it’s a simple fact that there is no such thing as a ‘standard model’ for the origin of life. Unlike particle physics and cosmology, there is no consensus theory that provides a commonly-agreed, standard interpretation.

The Lost City alkaline hydrothermal vent field features a collection of about 30 carbonate chimneys each between 30-60 metres tall. This picture shows a five-foot-wide ledge on the side of a chimney which is topped with dendritic carbonate growths. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The Lost City alkaline hydrothermal vent field features a collection of about 30 carbonate chimneys each between 30-60 metres tall. This picture shows a five-foot-wide ledge on the side of a chimney which is topped with dendritic carbonate growths. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.But I personally like the idea that life might have begun in the environments of alkaline hydrothermal vents. These are geological features that can be found close to the spreading centres of the Earth’s tectonic plates, such as the Mid-Atlantic Ridge which runs along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. Such vents are sources of molecular hydrogen, a side-product of a natural geological process called serpentinization.

In one possible scenario, the hydrogen reacts with carbon dioxide dissolved in the ocean, catalysed by iron-nickel-sulphur minerals. This is the first step in a sequence which can potentially produce a huge assortment of organic chemicals. I suspect that the real message from Comet 67P and from the array of substances found in interstellar molecular clouds is that the production of prebiotic chemicals, and thence amino acids and nucleotides, is a really rather irresistible consequence of chemistry, however and wherever it happens.

And there’s more. The vents form tall chimneys of calcium carbonate, structures with interconnecting pores of the order of a tenth of a millimetre. These could well have been the places where organic chemicals produced by natural processes became trapped and concentrated, allowing a trial-and-error biochemistry to develop. This environment provides a natural electrochemical gradient (a flow of positively-charged protons across the thin inorganic membranes between the pores), very reminiscent of the mechanism by which living cells manufacture adenosine triphosphate (ATP), used to transport energy.

The path leading from a primitive metabolic cycle, to RNA, to the genetic code, to DNA and to primitive cellular structures is highly speculative but nevertheless quite plausible.

Evolutionary biochemist Nick Lane, at University College London, has built a simple bench-top laboratory reactor (in the University’s aptly-named Darwin Building) with which he and his colleagues hope to simulate the chemical and geological environment of an alkaline hydrothermal vent. Early experiments have provided a preliminary proof of concept, and some empirical evidence that mild alkaline hydrothermal conditions, a supply of molecular hydrogen and carbon dioxide, an iron-nickel-sulphur catalyst and a micropore structure transected by natural proton gradients can indeed produce simple organic chemicals. Further results are expected this year.

The post How did life on earth begin? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 14, 2015

Gin a body meet a body

I am not sure that any lexicographer or historian of linguistics thought of writing an essay on James Murray as a speaker and journalist, though such an essay would allow the author to explore the workings of Murray’s mind and the development of his style. (Let me remind our readers that Murray, 1837-1915, died a hundred years ago.) So instead of immediately coming to the point, which today is the origin of the word body, I would like to begin with a long quotation from Murray’s Presidential Address given in 1897. He was at that time the president of the Philological Society.

“In referring to Professor Skeat’s Etymological Dictionary I have been tempted to contrast its cautious inductions with certain derivations that have been passed under my hands since commencing the Dictionary. The original Etymological Committee, you may remember, announced that they were prepared to receive ‘well-considered derivations of difficult words’. Several of these were in due course submitted, and have been preserved among the papers; I do not know that they would amuse anybody more than their writers, such of them as are still alive, and I propose at some future date, when we have a very dry paper, to bring in a little collection of these ‘well-considered etymologies’, and read them for edification, reproof, and instruction in foolishness. Thus one eminent philologist has ‘always had an impression that abide is from Hebrew beth a house, which in Persian is abád’. He is ‘not sure whether body is from the same root, but the Ags. [Anglo-Saxon, Old English] synonym bánhús [literally “bone-house”] supplies strong supporting evidence’.”

I don’t think Murray published a collection of such letters. But if he did, I would like to be informed, because I try to read everything he wrote.

Any comprehensive etymological database looks like Dickens’s dust heaps: most of it is garbage, but those who have the time and patience to rummage through one layer after another will be rewarded by many treasures. Nor does the nature of “well-considered derivations” change as the years go by. In 1985 another eminent philologist could not decide whether body is related to Breton bed ~ Welsh byd “world, universe,” Sanskrit bodh “tree” (with reference to the world tree as the pillar supporting the world), or a combination of the ancient root bhu- “to swell” and Old Engl. deag “color, hue, tinge,” the etymon of the modern word dye. Thomas Keightley, a good folklorist but an unreliable etymologist, thought that body had something to do with booth, a word allegedly used by the clergy for “tabernacle” (St Paul’s “body”). The idea is not laughable, but booth is a Middle English borrowing from Scandinavia, and its etymon never meant “body.” Moreover, body was already known in Old English and had the same meaning it has today. Another tempting “neighbor” is bottom, but it deserves a special post.

A promising database.

A promising database.While sifting through everything my database provides, I never lose imperturbability, or high indifference, as a great nineteenth-century poet once put it, for the goal (finding a word’s origin) is hard to achieve and following the devious paths in pursuit of the truth is instructive and useful. Etymologists cannot be bored and share the delights of their profession with phoneticians. As regards phonetics, Otto Jespersen, a famous linguist, was right; however stupid a talk at a conference may be, one can always observe the speaker’s accent and thus profit by the experience.

The distant history of body evades researchers. Even the excellent etymological dictionary of Old High German, in an entry on a cognate of body, makes do with a survey and offers no recommendations. The sought-for solution is so unclear that some people traced the word to an obscure foreign language (the substrate), but it is rather improbable that the name for a basic physical structure should have been taken over from such a source. The word designating “body” in all the old Germanic languages was lik (with long i, as in Engl. Lee). English like (conjunction, adjective, and verb) goes back to it, and so does lychgate (lych “body”). If we look at serious rather than fanciful derivations of body, we’ll note that at one time the best language historians connected body with the verb bind, and did so with great conviction. However, it is an unpromising conjecture with respect to both sound and meaning.

More realistic attempts to etymologize body center on the words denoting receptacles, and here the story resembles the one familiar in connection with the origin of barrel (the subject of a relatively recent post). Etymologists wandered around Engl. butt “a large cask,” Old Engl. buterie “leather bottle” and byden “tub, vat, etc.,” German Bottich “tub” (compare Botticher “cooper”), Old Icelandic buðkr “box” (the word different from the source of booth), and a few others of the same type. None of them are unthinkable as the base of “body,” for a body is indeed a kind of box or casket. But they came to the Germanic-speaking world from Romance; their source could have been apotheca “wine cellar” or Medieval Latin buttis “vessel,” or some such word. The question is the same that suggested itself in connection with the substrate: Why should Germanic speakers have borrowed a basic word for “body” from foreigners when they had a native one?

In West Germanic, lik was ousted to the periphery. In German, its reflex Leiche means “corpse” (and the words for “body” are Körper, a borrowing of Latin corpus, and Leib, a cognate of leben “to live”), while, in English, lych also refers to the mortuary sphere and has hardly any independent currency. Body, from bodig, has (or rather had) a cognate only in Old High German, namely botah. Thus, the Old English and the Old German noun shared the root but differed in the suffixes: bod-ig versus bot-ah. A similar picture can be observed in the history of the English word ivy and its German congener Efeu.

Gin a body meet a body.

Gin a body meet a body.What I am going to suggest is of course guesswork. I start from the existence of numerous words discussed in the previous posts: bad, bud, bed, bod–kin, Swedish badd-are “something big,” Old Engl. beadu “battle” (with its Romance look-alikes), and Old Saxon undar–bad-on “to frighten.” Some of them perhaps could have a long vowel in the root alternating with a long one. Their semantic base can be tentatively defined as “big, strong, requiring an effort, swelling (and therefore frightening).” Incidentally, body has once been tentatively compared with bud (by Ferdinand Holthausen), and among the oldest etymologies of body (it still has at least one influential supporter) we find bhu– “to swell” given as its ancient root. Yet I doubt that body has anything to do with any Indo-European root. It is more likely that in the Middle Ages, rather than in the days of Indo-European antiquity, Europe was swept by a wave of slang words beginning with b and ending in d. Perhaps some originated in baby language, while others owe their existence to jocular (“ludic”) popular usage. When an old noun referring to the structure of a living creature suddenly yields to an upstart, one is almost forced to admit that, excluding the possibility of a borrowing, a slang word triumphed over a respectable old-timer. At that period, it must have been “cool” to supply all kinds of qualities and things with b-d labels. So bod for lik appeared and, to conceal its low origin, allowed a suffix to be appended to it. Is this conjecture worthy of discussion? It is not for me to decide. Our bodies are fragile things. And so are most etymologies.

Image credits: (1) The Dust Heaps, Somers Town, 1836. Wellcome Images. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “Song LXXVI Gin a Body Meet a Body.” The Musical Repository. National Library of Scotland. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 via digital.nls.uk. (3) Robert Burns. Portrait by Alexander Nasmyth. (1787) Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Gin a body meet a body appeared first on OUPblog.

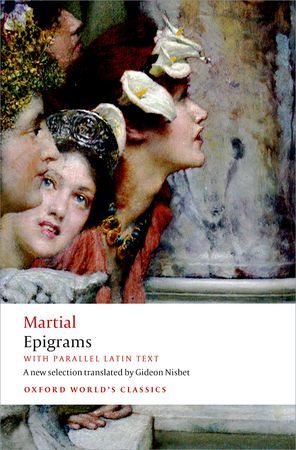

Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group Season 4: Martial’s Epigrams

“If you’re one of those terribly serious readers, now is a good time to leave.”

– Martial, Epigrams

The poet we call Martial, Marcus Valerius Martialis, lived by his wits in first-century Rome. Pounding the mean streets of the Empire’s capital, he takes apart the pretensions, addictions, and cruelties of its inhabitants with perfect comic timing and killer punchlines.

Martials’ Epigrams represents quite a departure from our previous seasons of the reading group. Our third season of #OWCReads ended with an exciting, Dickens-themed Twitter Q&A with Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, who helped us get our heads around Great Expectations. We now wave goodbye to Pip, Estella and Victorian London as our #OWCReads group takes on the exciting, funny, and often raunchy world of Martial.

Packed with incident and detail, Martial’s Epigrams brings Rome vividly to life in all its variety; biting satire rubs alongside tender friendship, lust for life besides sorrow for loss. Social climbers and sex-offenders, rogue traders, and two-faced preachers all are subject to his forensic annihilation and foul-mouthed verses. Gossipy, clever, and above all entertaining, they express amusement as much as indignation at the vices they expose. We are pleased to announce that Gideon Nisbit of the University of Birmingham has offered to give us a guided tour of the colourful streets of Ancient Rome as described in Martial’s Epigrams.

You can follow along, and join in the conversation by following us on Twitter and Facebook, and by using the hashtag #OWCreads.

Featured Image: Ancient Rome, CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Oxford World’s Classics Reading Group Season 4: Martial’s Epigrams appeared first on OUPblog.

Tax competition – a threat to economic life as we know it

The creativity of rich individuals and their tax advisors to hide private wealth in tax havens, such as the Cayman Islands or Switzerland knows hardly any bounds. Just as unethical, though often legal, are the multiple techniques multinational corporations use to shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions such as Panama or Bermuda. And even though small states have a structural advantage when it comes to engaging in tax competition, that is, attracting capital from abroad, big economies have become adept at playing the game, too: The United States, Germany, and with the Cayman Islands and Jersey, two jurisdictions politically dependent on the United Kingdom all feature in the top ten of the Tax Justice Network’s 2013 secrecy index.

As illustrated by widespread media coverage and numerous civil society campaigns, tax avoidance offends people’s sense of justice. Tax competition is part of a wider trend of the isolation of economic forces from electoral pressures under capitalism. The mobility of capital in an environment of deregulated markets allows capital owners to extricate themselves from the social contract. They benefit from public goods and infrastructure without paying their fair share. This trend undermines fiscal autonomy and it contributes to rising inequalities in income and wealth.

We can distinguish three types of tax competition that target portfolio capital of wealthy individuals, paper-profits of multinationals, and foreign direct investment (FDI) respectively. What should be done about these phenomena from an ethical perspective?

First, all forms of what the OECD has called ‘poaching’, that is the intrusion or free-riding by one state on another state’s tax base, should be eliminated. This rules out the first two types of tax competition previously mentioned, and thus would put an end to both individual tax evasion and corporate profit-shifting. Yet, there is a hic. Once you prohibit fiscal free-riding of this kind, the incentives for individuals and, in particular, for multinationals to actually relocate to a different jurisdiction, will increase markedly. If Apple and Starbucks and you-name-your-favourite-multinational can no longer reduce their effective tax rates to a fraction of the nominal tax rate in many countries, they will be more likely to move their activities (and jobs) to low-tax jurisdictions altogether. Incidentally, this is one of the reasons why the governments of rich countries have tolerated the injustices of poaching: they are afraid of the economic fall-out from closing loopholes.

Second, therefore, we have all the more reason to develop an ethical perspective on the third type of tax competition, the competition for FDI. What, if anything, is wrong for instance with Ireland’s low corporate tax rate and the fact that it attracts a disproportionate share of FDI in the European Union? Such policies should be prohibited when two conditions are jointly met: first, when the policy is strategically motivated, that is when it specifically targets attracting capital rather than pursuing independent political motives; and second, when it is effective in doing so, that is when it results in a net capital inflow to the country that adopts the policy. Regulating the competition for FDI is admittedly more complex than regulating the two forms of poaching. However, note that our current practices in international trade are very similar to what is proposed here. The World Trade Organisation (WTO) prohibits subsidies, because they undermine the level-playing field of international trade. Since a tax break and a subsidy are but two sides of the same coin, coherence calls for a regulation of the competition for FDI, too.

Whatever the precise contours of a regulation of tax competition, it requires a multilateral solution. This in itself presents a non-negligible challenge, since such a reform will necessarily produce winners and losers. The creation of an International Tax Organisation (ITO) with powers similar to those of the WTO would be an effective means to promote reform.

Some are likely to object that regulating tax competition risks being inefficient and / or violating national sovereignty. With regard to efficiency, on the contrary, the loophole characteristic of tax competition tend to favour an inefficient tax mix. As to sovereignty, any modern understanding of the concept recognises that the protection of sovereign rights comes with the obligation to respect the equivalent rights of others. From this perspective, shoring up the effective fiscal sovereignty of states calls for a regulation of tax competition rather than being opposed to it.

Featured Image Credit: British budget business by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Tax competition – a threat to economic life as we know it appeared first on OUPblog.

October 13, 2015

Should we ‘consent’ to oral history?

All of those presidential candidates who promise to change the world on “my first day in office” have a lot to learn about the federal government’s glacial pace. The government does tend to do the right thing, so long as you have the patience to wait a few years (or decades). On 8 September 2015, a 20-year struggle culminated in a ruling from the US Department of Health and Human Services that specifically excludes the following from human subject regulation: “Oral history, journalism, biography, and historical scholarship activities that focus directly on the specific individuals about whom the information is collected.”

The federal government began issuing rules that required universities to review human subject research back in 1980. At first, the regulations applied only to medical and behavioral research, but in 1991, the government broadened its requirements to include any “interaction with living individuals.” In 1995, a university hierarchy declined to accept a doctoral dissertation because the history graduate student had failed to consult the university’s institutional review board (IRB)—an entity none of her professors knew existed. She eventually received a retroactive exemption, but the incident sent shivers through the oral history community.

IRBs at universities, staffed almost entirely by those in the medical and behavioral sciences, began trying to fit oral history interviewing into protocols more designed for blood samples. IRBs instructed oral historians to keep their interviews anonymous, erase their recordings, and avoid asking possibly intrusive questions, which defeated the purpose of their projects. One student was met with resistance for naming the scholars in her field whom she had interviewed. Others were cautioned not to ask about illegal activities—even when interviewing civil rights activists who remained proud of the civil disobedience that led to their arrests. At their most illogical, there were boards that wanted researchers to obtain permission from third parties who had been mentioned during an interview, and even urged archivists to require researchers to apply for IRB clearance just to read an oral history transcript or listen to a recording in their collections.

Some scholars simply abandoned interviewing as a research or teaching tool to avoid the hassle. For years, a professor had partnered her college students with local high school students to conduct community-based oral histories, but she had to abandon the project when her campus IRB asked for certification that all participants in research activities were over the age of eighteen. Boards also expected faculty advisors who supervised theses and dissertations using oral history to take a standardized test on research ethics, despite its painfully clear orientation towards pharmacology.

In 2003, the Office of Human Research Protection (OHRP) approved a statement drafted by representatives of the Oral History Association and American Historical Association that defined oral history practices as fundamentally different from the quantitative research that the federal regulations had intended to cover. It argued that oral historians “do not reach for generalizable principles of historical or social development; nor do they seek underlying principles of laws of nature that have predicative value and can be applied to other circumstances for the purpose of controlling outcomes.” The OHRP agreed that people should be free to give their informed consent to be interviewed and to have those interviews opened for research, without any federally-mandated review. It has taken another dozen years for the government to issue that statement on its own. This decision is a victory for common sense and lifts a great burden from all oral historians. Let us hope that the IRBs get the message.

Image Credit: “A woman interviews her father for StoryCorps” by romanlily. CC BY NC ND 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Should we ‘consent’ to oral history? appeared first on OUPblog.

Arabia: ancient history for troubled times

In antiquity, ‘Arabia’ covered a vast area, running from Yemen and Oman to the deserts of Syria and Iraq. Today, much of this region is gripped in political and religious turmoil that shows no signs of abating. In addition to executions, murder, and a bloody war against the security forces and other armed groups, the so-called Islamic State (ISIS) is also waging a relentless assault on the culture and heritage of Syria and Iraq. This represents a savage attempt to impose its own narrow view of history on the region, as well as to plunder artifacts for sale on the black market. But while contraband dollars support its operations, it is also the suppression of diversity that drives ISIS; the group is particularly devoted to the eradication of any inconvenient reminder of the pre-Islamic past, where communities of Jews and Christians flourished and pagan deities were worshiped. The conquering Muslim armies of the seventh and eighth centuries may have swept past the now-endangered archaeological sites of Syria and Iraq, but the Islamic State sees the destruction of such places as key to its core mission. This line of thinking explains their destruction of the Temple of Bel at Palmyra, parts of Hatra in Iraq, and countless other structures and sites. Elsewhere, the war in Yemen is causing a great amount of damage to the country. Even without war, Middle Eastern heritage finds itself in danger; in Saudi Arabia, for example, building work has claimed parts of ancient Mecca, erasing alternative narratives of the past.

Palmyra, Syria. Photo by yeowatzup, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Palmyra, Syria. Photo by yeowatzup, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.In light of the seemingly endless attacks on culture and the loss of so many lives, it is more essential than ever to take stock of the region’s rich and varied ancient history. Framed by the vast expanse of the Roman and Persian empires, Arabia and its northern limits—Syria and Iraq—offered a land of contrasts. A traveller to Yemen would find lush mountains, rain, and farmland, but in the centre of the Peninsula and to the north, he would struggle across gravel, basalt, and sandy deserts. (To cross these areas required specialised knowledge, as a Roman military expedition to Yemen learned in 25 BCE). From the city of Zafar in Yemen to the famous emporium at Gerrha on the Gulf, and from the villages of Syria to the oases and watering holes of northern Arabia, a traveller would find a wealth of different peoples. Arabia included communities of Christians, such as those famously massacred at Najran in the sixth century CE. Pagans flourished throughout, but the Yemeni kings for much of the fourth and fifth centuries were Jews, before they adopted Christianity in the sixth. Arabia was a land where Roman and Persian agents competed for primacy in an ancient version of The Great Game, a competition spurred by the importance of the sea and land routes linking Arabia to the lands of the Mediterranean, Iran, and Central Asia. This network took Arab merchants to the Greek islands of the Aegean as well as to the Persian capital of Ctesiphon, near modern Baghdad. Trade, and the imperial ambitions of Rome and Persia, allowed religious, political, and cultural ideas to travel across the ancient Middle East. Arabia was far less of an isolated backwater than some ancient sources, fascinated with its supposed, legendary exoticism, would like their readers to believe.

Temple of Baal Shamin, Palmyra. Photo by E.jaser. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Temple of Baal Shamin, Palmyra. Photo by E.jaser. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Why does this matter today? Encouraged by the lack of international action, ISIS continues its determined effort to utterly erase the monuments of the ancient past in Syria and Iraq, whether they be Shia shrines, Christian monasteries, or pagan temples. ISIS already claims franchises in Libya and has taken responsibility for bombings in Saudi Arabia, while the climate in places such as Yemen is febrile. The war in Syria in particular has already taken a terrible toll, but the attack on heritage, deeply connected as it is to the human cost, should be recognised for what it is. If Syria was ever to be reconstituted in the future, it would be missing the cultural underpinning of much of what made the country such a rich patchwork of communities; the same fate threatens Iraq, if the government fails to tackle ISIS. But the communal history of the world suffers as well, because much connects our own understanding of the past with the history of the Middle East. And so more than ever, it is vital to appreciate what is being lost: places like Hatra and Palmyra represented everything that ISIS avows to hate—multicultural and ethnic diversity, crossroads between east and west, and places of communication and cultural transfer. Appreciating the deep and complex history of Arabia is more crucial than ever for making sense of troubled times.

Image Credit: “Temple of Bel complex in the background and the agora on left center in Palmyra, Syria” by Bernard Gagnon. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Arabia: ancient history for troubled times appeared first on OUPblog.

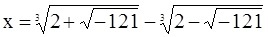

The real charm of imaginary numbers

In this blog series, Leo Corry, author of A Brief History of Numbers, helps us understand how the history of mathematics can be harnessed to develop modern-day applications today. In this second post, looking specifically at the impact of imaginary numbers on our comprehension of the physical world, Leo explores how theorems change over time.

Few elementary mathematical ideas arouse the kind of curiosity and astonishment among the uninitiated as does the idea of the ‘imaginary numbers’, an idea embodied in the somewhat mysterious number i. This symbol is used to denote the idea of, namely, a number that when multiplied by itself yields -1. How come? We were consistently told in the early years of secondary school that two numbers of the same sign, positive or negative, when multiplied by each other always yield a positive number. Now we are told that this is not always the case, and here we have this ‘number’ for which the rule does not hold? What kind of number is this if it breaks such a fundamental law about the multiplication of numbers? Is the mystery and the apparent contradiction solved just by calling i an ‘imaginary number’?

The truth is that when one is introduced to imaginary numbers, it’s not the first time that a fundamental idea previously taught, is turned upside down. Think, in the first place, about the negative numbers. When learning in primary school the job of subtracting numbers, a typically curious child may ask the teacher how to subtract, say, six from four. A typically cautious teacher would answer, “well, … ehem, … that can’t be done.” Indeed, it makes a lot of pedagogical sense to let the pupil acquire good mechanical skills in performing the operations without having to worry about such nuances, and there is no immediate need to bring up confusing issues such as the idea of negative numbers. All of this can be clarified later on, simply by telling the child that, “well … yes … actually, we can subtract 6 from 4 with the help of a new idea, the idea of negative numbers.” Most children tend to pass this experience without a lasting negative impact, though perhaps for some this is the beginning of the kind of post-traumatic symptoms so commonly associated in our society with the study of mathematics.

Image credit: Girolamo Cardano. Stipple engraving by R. Cooper from the Wellcome Library, London. CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Girolamo Cardano. Stipple engraving by R. Cooper from the Wellcome Library, London. CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.At any rate, the difficulty that typically arises immediately after becoming aware of the existence of negative numbers relates to the rule ‘minus times minus yields plus’. It really takes time until one becomes used to this strange rule, and, let’s be frank, many intelligent people never really come to believe it, and much less to understand its justification. And then comes the news that the number i breaks that rule.

The story of imaginary numbers is interesting not only because it touches upon the most central topic of mathematics, numbers and their properties, but also because there is a dramatic parallel between, on the one hand, the path that the individual student crosses before reaching a clear understanding of the topic and, on the other hand, the historical path that the world of mathematics at large had to cross for the same purpose. It may sound strange at first, but in general, central developments in the history of mathematics happen as the more complex ideas give way to simpler ones. This is opposite to the way in which we are typically taught, namely from the simple to the complex.

Roots of negative numbers started to surface repeatedly when the great mathematicians of the Renaissance worked out solutions for equations involving cubes and fourth powers of the unknown. The most prominent of these was Girolamo Cardano (1501-1576). The techniques he developed led to correct answers to the problems that he investigated, but the intermediary stages often involved calculations with roots of negative numbers such as:

For Cardano equations such as x2 + 1 = 0, or even the simpler one x + 3 = 0 have no solutions. Just like we were initially told in school. But his techniques were making roots of negative numbers, as in the example above, ever more conspicuous and unavoidable. He continued to look at them as ‘sophistic’, ‘subtle’ and ‘useless.’ Nevertheless his mathematical curiosity did not let him just ignore them. He searched ways to apply to these numbers the same formal mathematical procedures he had considered to be legitimate for integers and fractions, while at the same time “putting aside the mental tortures involved.”

The conceptual status of imaginary numbers was successfully clarified only slowly in the centuries following. They became central to our conception of mathematics at large by the mid-nineteenth century. No less interesting is the fact that this apparently artificially concocted idea also became fundamental for physics. Many of the central pillars of modern physics, such as electrodynamics, cannot even be conceived without imaginary numbers.

Featured image credit: Formula mathematics psychics by markusspiske. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post The real charm of imaginary numbers appeared first on OUPblog.

A session life for me: Studio musicians and London’s popular music industry in the 1960s

The popular music industries of the 1960s produced thousands of recordings with each studio relying on an infrastructure of producers, engineers, music directors, songwriters, and, of course, musicians. In recent years, documentaries have introduced us to instrumentalists and singers who formed the artistic backbones of America’s major studios. In Detroit, The Funk Brothers kept Motown’s assembly line of hits purring for The Supremes, The Four Tops, The Temptations, and many others. In Los Angeles, the so-called Wrecking Crew gave us the instrumental backing for The Beach Boys, The Byrds, and The Mamas and the Papas, to name only a few. Indeed, every major studio relied on such professionals, whether in Muscle Shoals, Memphis, Chicago, or New Orleans. And the same was true on the other side of the Atlantic in London.

Like Los Angeles, London boasted a network of recording studios associated not only with popular music, but also with film. An orchestral musician might participate in a film scoring session in the afternoon and be reading through an arrangement by George Martin for Cilla Black at night, if they were not already engaged in a theater pit. But the core of London’s profitable popular music industry depended on various combinations of guitars, basses, keyboards, and drums, often with backing singers on hand.

Session guitarists “Big Jim” Sullivan, Vic Flick, Jimmy Page (sometimes called “Little Jim”), Joe Moretti, Bryan Daly, and Joe Brown all began playing in bands until their technique, knowledge, and sound brought them to the attention of producers and of contractors. Similarly, bassists Allan Weighell, Herbie Flowers, John Paul Jones, Eric Ford, or Ron Prentice established their reputations as live performers before becoming denizens of the sunless world of recording studios. Producers turned to drummers like Bobby Graham, Clem Cattini, Ronnie Verrell, and Andy White because they had learned how to read music, how to hold a band together on stage, and when to play (and when not).

The major studios collectively agreed to three standard session times a day: 10:00 a.m-1:00 p.m, 2:30 p.m.-5:30 p.m., and 7:00 p.m.-10:00 p.m. Contractors like Charlie and Nita Katz (who will turn 100 in October) might book a musician to play a morning session at the EMI Recording Studios in St. John’s Wood, an afternoon session at Decca’s West Hampstead studios, and an evening session at Pye’s studios near Marble Arch. Musicians might also be engaged to record a commercial before the morning session or after the evening session. Other studios such as Olympic, Regent Sound, Trident, or IBC had more flexible hours, but all had to work around the system established by the majors.

In the first half of the sixties, production crews and musicians generally presumed that in a three-hour session (which did not include arriving in time to set up your equipment and to allow the studio staff to position microphones) a singer and musicians would be able to produce at least four completed recordings. Allowing a few hours for musicians to find the right groove for a song did not figure as part of the schedule, unless stars like The Beatles were involved, and even they might end up recording late at night to avoid scheduled day use of EMI.

Many of the best-known recordings of the era by The Dave Clark Five, Herman’s Hermits, and Them, as well as Peter and Gordon, Dusty Springfield, and Cilla Black, feature these musicians, whether acknowledged or not. Indeed, producers (commonly known as artist-and-repertoire managers in the early 1960s) and music directors relied on session musicians to realize their often-unspecific ideas about a performance in the studio.

In 1964, pianist and music director Reg Guest came up with at least two different arrangements for the landmark recording of “The Crying Game” (the orchestral version was never released), but it was Jim Sullivan’s musically and technically inventive guitar playing delicately embroidering Dave Berry’s vocal that distinguish this disc. Using a DeArmond foot pedal (originally intended for a pedal-steel guitar) to play with tone and volume, Sullivan painted tears onto Geoff Stephens’ song.

The power of this performance was not lost on Beatle George Harrison, who would experiment with this sound on recordings like “Yes It Is” and “I Need You.” As importantly, Sullivan invented those iconic guitar licks in the studio. Indeed, the abilities, not only to play flawlessly, but also to be endlessly creative and spontaneous on cue, represented the fundamental characteristics of a successful session musician. The daily grind could be grueling and psychologically draining, but the gallows humor between musicians and the mutual professional respect helped to sustain them. They accepted their session fee and heard themselves on the car radio as they drove from one gig to the next.

This version of the studio world faded after 1968 when first eight-track and then sixteen-track recording equipment arrived along with the establishment of more private studios, which meant that the need for four perfect sides in three hours was no longer quite so pressing. But their impact on the music of that golden age is undeniable and there is much to learn from that process.

Featured image: Old radio. (c) via iStock.

The post A session life for me: Studio musicians and London’s popular music industry in the 1960s appeared first on OUPblog.

A Chekhovian view of privacy for the internet age

Defining “privacy” has proven akin to a search for the philosopher’s stone. None of the numerous theories proposed over the years seems to encompass all the varied facets of the concept.

In considering the meaning of privacy, it can be fruitful to examine how a great artist of the past has dealt with aspects of private life that retain their relevance in the Internet age. An example is provided by the short stories of the great Russian writer Anton Chekhov (1860-1904), whose work often deals with the distinction between the public and the private spheres. Space constraints lead me to focus on only two of his hundreds of short stories.

In perhaps his most celebrated story, The Lady with the Little Dog (1899), two people engaged in an adulterous affair gradually come to realize that they have, inconveniently and unexpectedly, fallen in love, with no idea of how to resolve the situation. The society in which these characters lived made a sharp distinction between their private and public lives, and required them to keep their liaison strictly secret, as the male protagonist notes:

“He had two lives: one was the public one, which was visible to everyone who needed to know about it, but was full of conditional truth and conditional deceit, just like the lives of his friends and acquaintances, while the other one was secret. And by some strange coincidence—perhaps it was just chance—everything that was important, interesting, and essential to him, in which he was sincere and did not deceive himself, and which made up the inner core of his life, was hidden from others, while everything that was false—the outer skin in which he hid in order to cover up the truth, like his work at the bank, for example, the arguments at the club, his ‘lesser species’, and going to receptions with his wife—was public….” (quoted from Chekhov, About Love and Other Stories, translated by Rosamund Bartlett)

The value of the private realm is shown by Chekhov’s portrayal of the development of the characters’ relationship. Modern-day critics of privacy have sometimes found it to be nothing more than an excuse for concealing what is shameful or forbidden (e.g. Google’s Eric Schmdt stating “If you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place“).

Portrait of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov by Osip Braz. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Anton Pavlovich Chekhov by Osip Braz. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Chekhov demonstrates the value of the private sphere by showing how it allows the development of our inner selves. In the story, the relationship between the two main characters seems like a tawdry fling at the beginning, but is revealed to be something profound and meaningful by the end. To Chekhov, the private represents what is honest and sincere, whereas the public often involves deception of both others and ourselves. I am sure he would have found that our modern preoccupation with revealing our inner selves via online services and social networks, and the merging of the public and private realms though constant online availability, has led to the loss of something valuable and particularly human.

Considering privacy as an inner realm where we can be honest with ourselves means that we must have the ability to admit other human beings into it when we need to. This theme is explored in the short story Misery (1886), where the protagonist is a sleigh driver who is forced to work in the harsh winter while in emotional anguish because of the recent death of his son. When he attempts to discuss his loss with his passengers he encounters only disinterest and ridicule, and is finally able to confide his sorrows only to his horse. This example of loneliness in a crowd puts one in mind of communication on the Internet, where it is easier to interact with an unlimited number of people than to find a sympathetic listener for one’s innermost concerns.

Chekhov values privacy because it allows a higher quality of inner deliberation, and helps us remain true to ourselves. In his view, we tend to engage in greater dissembling and rationalisation in the way we act towards others than in private contemplation. Maintaining an inner, private sphere thus allows us to hold an honest inner dialogue and to see ourselves more clearly. In addition, human beings must retain the power to determine the limits of the private realm to which they can retreat, which cannot be wholly devolved to the state, regulators, or the private sector. Privacy must enable the individual to make meaningful choices about the limits of his or her inner life.

Chekhov’s examination of private life demonstrates his sensitivity to the distinction between what we really are and what we pretend to be to other people. While these insights reflect the highly stratified society of pre-revolutionary Russia in which he lived, they are still valuable for today’s computerised and globalised world, in which we are struggling to maintain a private realm and to define its boundaries.

Featured image credit: System Lock, by Yuri Samoilov. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A Chekhovian view of privacy for the internet age appeared first on OUPblog.

October 12, 2015

Cars – are they a species?

The Edwardian seer and futurologist, H. G. Wells, wondered whether aircrafts would ever be used commercially. He did the calculations and found that, yes, an airplane could be built and, yes, it would fly, but he proclaimed this would never be commercial – the amount of oil-based fuel required was far too great, totally unrealistic. That a global politico-economic nexus would arise just in order to extract this black, sticky stuff (oil and oil products) was simply too fantastical a prospect for Wells to anticipate. (Question: what ‘obvious’ trends are our current futurologists missing?)

One of our contemporary seers is the naturalist and broadcaster Sir David Attenborough. He suggests that grass has ‘herded’ elephants, arguing that the elephants cull the trees and so enable the grasslands to increase their dominion. Is it too much to suggest that cars have likewise procreated and spread by bending human society to their own ends? We now have ‘birthing centres’ (car factories), a ‘food-distribution system’ (petrol stations), a road network, and so on. And cars are enmeshed in human society in so many ways beyond mere transportation. They are implicated in our courtship rituals, our ID system, our status hierarchy, our social interactions (for example, we become a ‘different person’ behind the wheel), and so on, and so on.

Much of this behaviour is counter-intuitive and must be trained into us; guiding an object of very large momentum in a straight line almost directly at another approaching object of equally large momentum – narrowly missing a head-on collision – would never pass ‘health-and-safety’ standards if introduced today.

The fact that the car-society has arisen by evolution rather than by edict doesn’t mean that we like all the consequences. While the advantages of cars are many, there are aspects that we don’t like at all: cities are divided by highways, we choke on fumes, obesity is a problem that in turn further increases our dependency on the car, and there is a high rate of death on the roads. In fact, the death toll is so high (it is by far the main cause of death in 5- to 50-year-olds), that an equally high death rate from any other source (war, murder, radioactivity, drugs, deaths while in custody, etc.) would cause public outrage, not to say pandemonium. As the cause is cars and other vehicles, we submit with barely a murmur. An even bigger side-effect of the car-society, which we are also barely aware of, is the impact on the climate.

A car should really be called a ‘boiler-on-wheels’ and, in rich hot countries where people have car air-conditioning, ‘a-fridge-on-a-boiler-on-wheels.’

Just as remarkable as the growth of the car-society is the fact that cars are a kind of heat-engine. Nature doesn’t like to get work from heat, and it can only do this to a certain limited efficiency, as I discuss in my blog, “Global Warming and the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics.” We have the astonishing fact that cars, even while they can be improved by better fuels, electronic ignition, computerization, are inherently inefficient. It’s a bit like ordering your dinner and then throwing most of it away every time. Cars and all heat-engines can only run by throwing away waste heat. The energy from the fuel goes partly into moving the car forward, and also into combating friction, air resistance, and expulsion of waste gases, but the major part of the fuel’s energy goes into heating up the engine block. A car should really be called a ‘boiler-on-wheels’ and, in rich hot countries where people have car air-conditioning, ‘a-fridge-on-a-boiler-on-wheels.’

What is to be done? My feeling is if evolution got us into this mess, then evolution could get us out of it. For sure (and despite the Jevons’s Paradox), we must try and improve engine-efficiency, increase public transport, and walk and use bicycles more, but in order to change the direction of societal evolution there must, inevitably, be societal changes. I tentatively propose two changes: more cars, but each tailored to a particular use (for example, a tiny one-person car for getting you and one briefcase from home to the train or bus station) and free cars (like free bicycles in some cities today). Perhaps if cars are freely available, then the motivation for proving one’s wealth by car-ownership will diminish.

If a new species has indeed arisen, what is the unit ‘organism’ which has evolved? Despite the title of this blog, it cannot be a car, pure and simple; we could, rather, call it the ‘car-human.’ If, at some later stage, robot-driven cars appear in large numbers then the unit will have speciated. For a society of ‘robot-cars’ we may well wonder whose or what needs are being served.

Image Credit: “강변북로의 교통체증 Traffic Jam, Gangbyunbuk-ro (Nothern Riverside City Expressway in Seoul)” by Doo Ho Kim. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Cars – are they a species? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers