Oxford University Press's Blog, page 603

October 16, 2015

World Anaesthesia Day: Key events in the history of anaesthesia

To mark World Anaesthesia Day (Friday 16th October), we have selected ten of the most interesting events in the history of anaesthesia. From the discovery of diethyl ether by Paracelsus in 1525, to James Young Simpson’s first use of chloroform in 1847, and the creation of the Royal College of Anaesthetists in 1992 – anaesthesia is a medical discipline with a fascinating past.

Attempts at producing a state of general anaesthesia can be traced throughout recorded history in the writings of nearly every civilisation. Despite this, advancement in this area was still relatively slow. The Renaissance saw significant advances in anatomy and surgical technique, but such procedures remained a last resort. It was scientific discoveries in the mid-19th century that were really critical to the adoption of modern anaesthetic techniques.

Just as it has progressed in the past, anaesthesia is continuing to evolve in the present day. Modern developments such as tracheal intubation, advanced monitoring and new anaesthetic drugs, have all helped the specialty develop. Take a look at our interactive timeline at the bottom of this article for even more fascinating facts, free chapters, and commentary on the history of anaesthesia.

1. The first documented use of anaesthesia during surgery? (140 – 208)

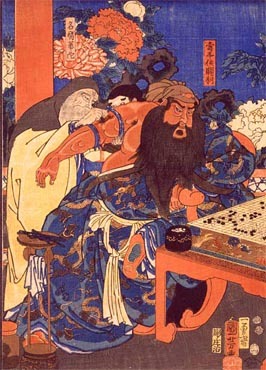

According to Chinese tradition, during The Three Kingdoms period (AD 225–265), the eminent physician Hua Tuo (c. 140 – 208) developed an analgesic potion called mafeisan (a mixture of herbal extracts). One of his patients, General Kuan Yu, was wounded by a poisoned arrow.

Image Credit: ‘Japanese Woodblock: Hua Tuo operating on Guan Yu’ by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798 – 1861), Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Japanese Woodblock: Hua Tuo operating on Guan Yu’ by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798 – 1861), Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.As the story goes, General Kuan Yu drank the potion and played chess as his bone was scraped clean by Hua Tuo while his attendants fainted. Medical scholars believe that this is the first documented use of anesthesia during surgery. According to records, General Kuan Yu maintained his poise, without betraying the slightest sign of pain.

2. Paracelsus discovers the analgesic properties of diethyl ether (1525)

“All things are poison and nothing is without poison, only the dose permits something not to be poisonous.” – Paracelsus

In 1525, Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (1493–1541), better known as Paracelsus, discovered the analgesic properties of diethyl ether. The history of general anaesthesia is rich and storied – even the very concept of anaesthesia has roots in the parallel evolution of religious beliefs and medical science. Paracelsus pioneered the use of chemicals and minerals in medicine. His hermetical views were that sickness and health in the body relied on the harmony of man (microcosm) and nature (macrocosm). While ether was known to Paracelsus in the sixteenth century as sweet oil of vitriol, it took another three centuries for its use as an anaesthetic to be fully realized.

3. Horace Wells witnessed the effects of nitrous oxide (1844)

On 11th December 1844, Horace Wells, a dentist from Hartford, Connecticut, witnessed a public display of a man inhaling nitrous oxide. The man subsequently hit his shin on a bench – but as the gas wore off, he miraculously felt no pain. With inspiration from this demonstration and a strong belief in the analgesic (and possibly the amnestic) qualities of nitrous oxide, on 12th December, Wells proceeded to inhale a bag of the nitrous oxide. Interestingly, inhalation of nitrous oxide for recreational use began as early as 1799 amongst the British upper class, at ‘laughing gas parties’. Today, it is still used for similar purposes – commonly referred to as ‘nos’.

Whilst under its influence, Wells had his associate John Riggs extract one of his own teeth. With the realization that dental work could be pain free, Wells proceeded to test his new anaesthesia method on over a dozen patients in the following weeks. He was proud of his achievement, but he chose not to patent his method because he felt pain relief should be “as free as the air.” Interestingly,

4. William Morton discovers the effects of sulphuric ether (1846)

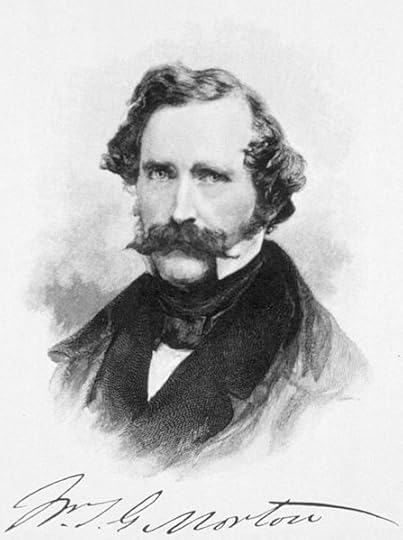

Image Credit: William Thomas Green Morton (1819 – 1868), Unknown author, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: William Thomas Green Morton (1819 – 1868), Unknown author, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Modern anaesthesia as we know it began in earnest on 16th October 1846, with a young Boston dentist named William Morton. He gave the first successful public demonstration of painless surgery using ether; removing a tumour from a young man’s neck in Boston, Massachusetts. Morton had previously worked alongside Horace Wells, and knew of his experiments with nitrous oxide.

Given Wells’s embarrassment when one of his demonstrations went wrong however (removing a man’s tooth using nitrous oxide), Morton sought something more effective. He experimented, with the help of the chemist Dr. Charles T. Jackson, with sulphuric ether, trying it first on his spaniel and then a young man, Eben Frost, again for tooth extraction. It was a great success, and the ether rendered the subjects insensible to the pain inflicted. Morton, and the field of anaesthesia, were on the road to fame.

5. James Young Simpson first used chloroform as a general anaesthetic (1847)

Scottish obstetrician James Young Simpson, 1st Baronet (1811–1870) of Edinburgh, was the first to introduce chloroform for general medical use. Previously, he had used ether in childbirth – but because of the unpleasantness of this drug, he began experimenting with other chemicals. On 4th November 1847, Simpson and two of his friends (Drs. Keith and Duncan) inhaled chloroform – experienced a light, cheery mood – and promptly collapsed.

On waking, Simpson knew he had found a successful anaesthetic. After this point, the use of chloroform anaesthesia expanded rapidly. Chloroform was much easier to use but was later shown to be much more dangerous in overdose than ether. In the early days of its discovery, it was used widely and indiscriminately, and inevitably soon became incriminated in a number of anaesthetic deaths.

6. Karl Koller first uses cocaine as a local anaesthetic (1884)

This discovery signalled the dawn of local anaesthesia. Cocaine had been identified and named by Friedrich Gaedcke (1828 – 1890) and then Albert Niemann (1834 – 1861) in 1855, and was used topically by a number of physicians. It was the use on the eye however, by Karl Koller in 1884, that first stimulated widespread interest.

Koller’s findings were a medical breakthrough. Prior to his discovery, performing eye surgery was difficult because the involuntary reflex motions of the eye to respond to the slightest stimuli. It is perhaps a further comment on the quality and safety of general anaesthesia at the time, that new methods of achieving painless surgery were so vigorously sought.

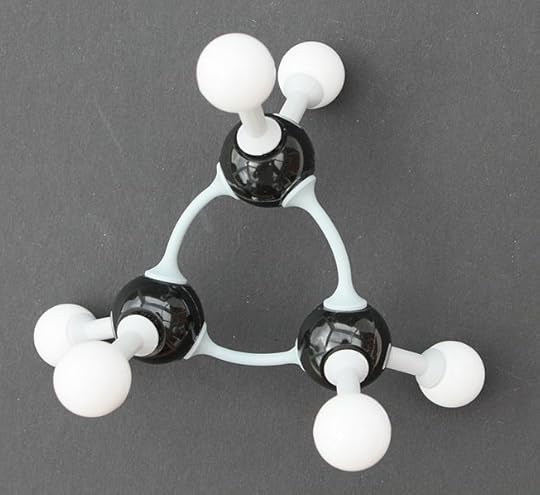

Image Credit: ‘Moleküel – gebaut mit dem Molekülbaukasten; Cyclopropane’, by Bin im Garten, CC by SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Moleküel – gebaut mit dem Molekülbaukasten; Cyclopropane’, by Bin im Garten, CC by SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.7. Emery Andrew Rovenstine pioneered the use of cyclopropane in anaesthesia (1930)

Alongside his colleague at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (Dr. Ralph M. Waters), Rovenstine first developed the anaesthetic use of the gas cyclopropane. When cyclopropane was first introduced in 1929, it was used for thoracic anaesthesia. In 1930 however, Rovenstine reported the use of cyclopropane for thoracic work – with tracheal intubation but spontaneous respiration.

Carbon dioxide absorption with the Waters canister (originally named the ‘Waters To-and-Fro Carbon Dioxide Absorption Canister’, invented by Ralph M. Waters), made use of cyclopropane more economical – and its use took off. By 1939, cyclopropane was the anaesthetic of choice for thoracic anaesthesiologists. Despite its popularity however, cyclopropane was also highly explosive; and ignition could have had serious and even fatal outcomes.

8. Dr. JM Graham performed spinal anaesthesia on Albert Woolley and Cecil Roe (1947)

On 13 October 1947, Dr JM Graham performed spinal anaesthesia on Albert Woolley and Cecil Roe. As a result of the surgery, both suffered permanent spastic paraparesis that blighted the remainder of their lives. The ensuing case did not get to court until 1953. The main witness for the Graham’s defence was Professor Robert Macintosh, author of a leading textbook on spinal anaesthesia and the inaugural Nuffield Professor of Anaesthetics at Oxford University.

Whatever the cause of Woolley and Roe’s paraparesis, the effects upon regional anaesthesia in general and spinal anaesthesia in particular were negative, dramatic, and long lasting. They greatly added to concerns about the safety of spinal anaesthesia raised by a 1950 article entitled: “The grave spinal cord paralyses caused by spinal anaesthesia”; and fueled a fear of regional anaesthesia in general. These reports cast a grey pall over spinal anaesthesia, and may well have delayed its introduction into obstetric anaesthesia.

Image Credit: ‘Garden Gate’, by Eptalon, CC by SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Garden Gate’, by Eptalon, CC by SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.9. Melzack and Wall propose the ‘Gate control theory’ (1965)

In 1965, Ronald Melzack and Patrick David Wall introduced an imaginative and comprehensive theory, known as the gate control theory of pain, to account for horrific injuries that are sometimes not felt as pain, and minor injuries that are sometimes felt as severe pain.

They used recently discovered physiological data and clinical data to suggest that a mechanism in the spinal cord “gated” sensations of pain from pain receptors – before they were interpreted or reacted to as pain. Combining early concepts derived from the specificity theory and the peripheral pattern theory, the gate control theory is considered to be one of the most influential theories of pain because it provided a neural basis which reconciled the specificity and pattern theories and ultimately revolutionized pain research.

10. The first National Anaesthesia Day is held in Great Britain (2000)

The first National Anaesthesia Day was held in Great Britain on 25th May 2000 – organised by the Royal College of Anaesthetists. On a global scale, the World Anaesthesia Day takes place every year, on 16th October. Originally named ‘Ether Day’ it is held in order to commemorate William Morton’s first successful demonstration of ether anaesthesia at the Massachusetts General Hospital on 16th October 1846.

As well as World Anaesthesia Day, the first specialist anaesthetic college was created, by Royal Charter, on 16th March 1992. This was a defining moment in the creation of an independent body, responsible for “Educating, Training and Setting of Standards in Anaesthesia in Britain.” Its work today is as important as ever – and helps paves the way for further developments in the field.

Want to find out more? Take a look at our extended, interactive timeline below:

Featured Image Credit: ‘Anaesthesia: Nitrous Oxide Cyliner, 1939’, from Wellcome Images (Welcome Trust). CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The post World Anaesthesia Day: Key events in the history of anaesthesia appeared first on OUPblog.

Did human grammar(s) evolve?

In order to hypothesize about the evolutionary origins of grammar, it is essential to rely on some theory or model of human grammars. Interestingly, scholars engaged in the theoretical study of grammar (syntacticians), particularly those working within the influential framework associated with linguist Noam Chomsky, have been reluctant to consider a gradualist, selection-based approach to grammar. Nonetheless, these scholars have come up with an elaborate and precise theory of human grammars. It has recently been shown that this syntactic theory can in fact be used, precise as it is, to reconstruct the stages of the earliest grammars, and to even point to the constructions in present-day languages which resemble/approximate these early proto-grammars (Ljiljana Progovac, 2015, Evolutionary Syntax). These constructions can be considered “living fossils” of early grammars, as they have continued to live alongside more recently evolved structures (Ray Jackendoff, 2002, Foundations of Language: Brain, Meaning, Grammar, Evolution).

While some say that we can never figure out language origins because “language leaves no fossils,” my recent engagement with this topic leads me to the conclusion that language, and better yet, the thousands of human languages spoken today, reveal a multitude of living fossils and other clues to language origins. But it is only by using a coherent linguistic theory as a tool that one can access such fossils and clues. Moreover, due to recent advances in neuroscience and genetics, it is now possible to test hypotheses of this kind.

Following a reconstruction method mentioned above, one arrives at the initial stage of grammar which was an intransitive two-slot mold, and in which the subject/object distinction could not be expressed grammatically. In syntactic theory sentences and phrases are considered to be hierarchical constructs, consisting of several layers of structure, built in a binary fashion. Thus, to derive a sentence such as Deer will eat fish, we first put together the inner layer, the small clause (eat fish). The tense layer (will), and the transitivity layer (deer), are added only later on top of this small clause foundation. The transitivity layer enables the grammatical differentiation between subjects and objects (e.g. Deer eat fish; Eat fish by deer).

Importantly, the layer upon which the whole sentence rests is the inner, foundational (eat fish) layer, which can therefore be reconstructed as the initial stage of grammar. The unspecified role of the noun in this layer can be characterized as the absolutive role, as such roles are not directly sensitive to the subject/object distinction. Absolutive-like roles are found not only in languages that are classified as ergative-absolutive, but probably in all languages, in some guise or another. Human languages in fact differ widely with respect to how they express transitivity, and this reconstructed absolutive-like basis provides the common denominator, the foundation from which all the variation can arise. Given this approach, variation in the expression of transitivity can shed light on the hominin timeline, as well as the timing of the emergence of different stages of grammar.

One absolutive-like living fossil is found among verb-noun compounds, such as English: cry-baby, kill-joy, tattle-tale, turn-coat, scatter-brain, tumble-dung (insect); Serbian cepi-dlaka (split-hair; hair-splitter), ispi-čutura (drink-up flask; drunkard), vrti-guz (spin-but; fidget), jebi-vetar (screw-wind; charlatan); and Twi (spoken in Ghana) kukru-bin (roll-feces; beetle). If we compare compounds such as turn-table and turn-coat, we observe that the first describes a table that turns (table is subject-like), and the second describes somebody who turns his/her coat, metaphorically speaking (coat is object-like). But these two compounds are assembled by exactly the same grammar: the two-slot verb-noun mold, unable to make subject/object distinctions.

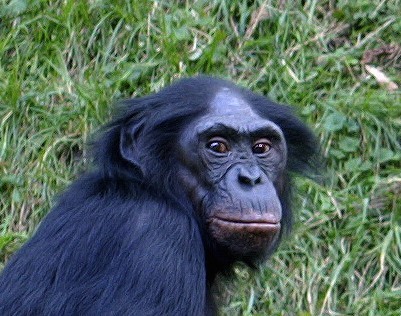

Head of a Bonobo (Pan paniscus) by User:Amir. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons

Head of a Bonobo (Pan paniscus) by User:Amir. CC BY-SA 2.5 via Wikimedia CommonsIt is important that this kind of two-slot grammar, combining a verb-like and a noun-like element, is not completely out of reach for non-humans. The bonobo Kanzi has been reported to have mastered such syntax in his use of lexigrams and gestures (Patricia Greenfield and Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, 1990, “Language and intelligence in monkeys and apes”). If Kanzi is in principle capable of (sporadic) two-sign combinations, then it is conceivable that at least some individuals of our common ancestor with bonobos were, too. Researchers sometimes assume that seeking continuity of grammar with animal capabilities entails finding identical abilities. But that cannot be right, for, after all, humans had millions of years to undergo selection for language abilities since the time of our common ancestor with bonobos. Continuity should thus be sought in the most rudimentary precursors to language abilities.

In addition to being illustrative of a most basic grammar, it is intriguing that verb-noun compounds in many languages specialize for derogatory reference and insult when referring to humans. There have existed many crude, obscene representatives of such compounds in various languages, the vast majority of which, however, have been lost and forgotten. In medieval times alone, thousands of such compounds were used, certainly many more than nature needs. Such abundance, indeed extravagance, is usually associated with display and sexual selection, the force that has also created the peacock’s tail. Just like with the peacock’s tail, what a species selects for is not necessarily good or superior in some lofty sense, or for long-term purposes. It may just be what is found interesting and novel at some particular juncture, in some particular location. As Charles Darwin noted, primates suffer from neophilia (love of novelty), and the human species is certainly guilty of that (Darwin, 1872, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals).

Featured image credit: ‘2100 year old human footprints preserved in volcanic mud near the lake in Managua, Nicaragua’ by Dr d12. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The post Did human grammar(s) evolve? appeared first on OUPblog.

The soda industry exposed [infographic]

Although soda companies such as Coca-Cola and PepsiCo are recognized around the world – the history, politics, and nutrition of these corporations are not as known. Things such as poor dental hygiene, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, can all be prevented by simply not drinking soda. In her latest book, Soda Politics: Taking on Big Soda (and Winning), Marion Nestle exposes the truth behind this multi-billion dollar industry. Check out these hard hitting facts and see how much you actually know about the soda industry.

Feature Image credit: Codd-neck Soda Bottles by Siju. CC-BY- SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The soda industry exposed [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Music: the language of play

Every day after school, eager children cross the doorstep of a suburban Melbourne house. It’s the home of Daphne Proietto, an exceptional piano teacher who gives lessons to children six days a week, entirely pro bono. While some kids would be more inclined to see piano lessons as a chore, these kids can’t wait. The reason? Music for them is more than just an activity; for many of them, it’s their language. As you may have guessed, the students of this particular piano teacher are not your average students; they have autism, and Daphne is using the repetitive nature of music to provide them with a way of communicating that makes more sense to them than the confusion many experience when faced with language.

Interviewed as part of a 60 Minutes report for Australia’s Channel 9, University of Roehampton professor Adam Ockelford gave the following explanation: “Language is inconsistent, and what an autistic child really wants is complete consistency. And what you get with music if you play a C on a keyboard, it’s always going to be the same. I think that predictability is a really key thing for autistic children.” While many of Daphne’s students have little or no speech, and others struggle with the emotional contents of words and their implied meanings, the abstract quality of music is, in contrast, highly appealing. Music as an ordered and consistent system provides them with a highly structured means of communication. What’s more, as Professor Ockelford suggests, “Music is like the language of play. It doesn’t tell you to do anything…. It just is.”

Autism has no cure, but many high functioning adults on the autism spectrum would point to historical figures such as Mozart, Tesla, Einstein, and Lewis Carroll as a justification for the need to embrace eccentric minds as gems of our society. Whether the reason behind the quirks and unconventionalities of these and other innovators is autism or not, what is evident is that unique perspectives are behind some of the world’s greatest advances.

That being said, there are many children with autism who struggle to communicate with language, and have severely stunted social skills. For these children, differing educational programs have been developed in the hope of enhancing their quality of life. While the positive effects of these programs are undeniable, there is an almost incomprehensible omission of music from these programs. This remains an unjustifiable hole in mainstream therapeutic programs that desperately needs to be filled.

Music is important to all children with autism, but especially to a particular subgroup of children on the autism spectrum who exhibit an ability known as absolute pitch: the ability to identify a note without any prior hearing of a note to work from. One in twenty children with autism is thought to have this ability, which is about 500 times more often than in the general population. For these children, music provides them with a consistent and familiar landscape in an otherwise confusing world. So let’s go back to Daphne and her exceptional group of students. Perhaps not surprisingly – even if no less exceptional – all of Daphne’s students have absolute pitch. For them, individual notes are remarkably familiar, and can elicit a high level of emotional arousal in a way that is uncommon for most of us.

Neuroimaging research has shown us that music and language are closely linked in the brain, so it’s not difficult to understand why some children’s language ability does improve through musical training. But perhaps even more importantly for them and their families, music can help build these children’s confidence and self-esteem — something that is so very clear when observing the transformation that many of Daphne’s students have gone through. As Professor Ockelford aptly describes, “Music to me is like a core curriculum for children with autism, because without music we couldn’t learn to speak, without music we couldn’t learn to socialize, and it’s absolutely a key facet in their life that generally tends to be underrated.” Daphne’s students are incredibly lucky to have found a teacher that not only understands the transformative effect of music in their lives, but also is willing to offer it to them with such generosity. How many other children with special needs are missing out on the benefits of a musical education? The answer to that question is, simply, too many.

Featured image: Piano Keyboard, by Scott Detwiler. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Music: the language of play appeared first on OUPblog.

In defense of myth

I approach myth from the standpoint of theories of myth, or generalizations about the origin, the function, and the subject matter of myth. There are hundreds of theories. They hail from anthropology, sociology, psychology, politics, literature, philosophy, and religious studies.

Some theorists of myth, Joseph Campbell above all, consider myth a panacea for all human woes. For him, every culture must have myth, and he attributes contemporary social problems, such as crime, to the absence of myth. For him, there is no substitute.

Other theorists of myth, such as C. G. Jung and Mircea Eliade, maintain that myth is most helpful – for Jung in getting touch with one’s unconscious, for Eliade in getting in touch with God. But neither quite deems myth indispensable. For Jung, dreams are an alternative to myth. For Eliade, rituals are.

All theorists deem myth useful. For some, myth is a very good way of fulfilling whatever need it arises and lasts to serve. For others, myth is as good as any other way. For a few, myth is the best way. For Campbell, myth is the only way. There are no theorists of myth for whom myth is useless, let alone harmful. (By contrast, there are plenty of theorists of religion, which sometimes overlaps with myth, for whom religion is harmful. Freud and Marx are examples.)

I myself am no evangelist for myth, and I am open to all theorists. But I do get miffed at one view of myth: that of myth as simply a false story or conviction, one to be exposed and dismissed. Books with titles like “JFK: The Man and the Myth” exemplify this approach. This view of myth does not even qualify as a theory, for it scorns the question of what myth accomplishes. Here myth accomplishes nothing save to hide the truth. Ironically, there is a full-fledged theory that does consider myth a means to hide the truth: that of the French-born literary critic René Girard. But he ties myth as a cover-up to a whole theory of why myth covers up. He does more than expose the cover-up.

Myth as a false story or belief is not objectionable because myth is thereby false. For me, a myth can as readily be false as be true. (But then it can as readily be true as be false.) The falsity or truth of myth is secondary. What is primary is the need that the story originates and functions to serve.

Carl Jung with Sigmund Freud and others. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Carl Jung with Sigmund Freud and others. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Why was it ever necessary to propagate an inflated, hagiographical account of the life of President Kennedy? Why was a straightforward, unvarnished account insufficient? Would Kennedy have thereby been taken as less of a hero?

Yes, of course, one might reply. How naïve can one be? But then the characterization of a biography of Kennedy as myth shows that myth is much more than a merely false depiction. It is an idealized one, and the idealization is where the appeal lies. Declaring that a depiction of Kennedy is mythic is declaring that the depiction one is alluring. The power of myth, to use a phrase of Campbell’s, is its appeal to more than the facts, and even when the facts are scrupulously accurate. The appeal is what makes a biography mythic. But then myth, whether true or false in its facts, goes beyond the facts.

Put another way, dismissing as false the claim of a myth is not like dismissing as false the claim that I have a tenner in my pocket. Presumably nothing rests on my claim. If I am wrong, so be it. But dismissing as false the claim that Kennedy was a great person is dismissing a claim to which deep feelings are attached. What makes the claim mythic goes beyond whether it is true. It can be true and still be mythic, so that, again, myth is more than a false story. A myth that is false is hard to dislodge because of the commitment to it. But again the grip of a myth rests on more than its falsity – or truth.

Featured image credit: Enchanted Forest, Public domain via Pixabay.

The post In defense of myth appeared first on OUPblog.

October 15, 2015

On Indian democracy and justice

India’s political scene has been changing rapidly in recent years. In the extract from The Country of First Boys And Other Essays below, Amartya Sen reflects on the triumphs and failures of Indian democracy.

We have reason to be proud of our determination to choose democracy before any other poor country in the world, and to guard jealously its survival and continued success over difficult times as well as easy ones. But democracy itself can be seen either just as an institution, with regular ballots and elections and other such organizational requirements, or it can be seen as the way things really happen in the actual world on the basis of public deliberation. I have argued in my book The Argumentative Indian that democracy can be plausibly seen as a system in which public decisions are taken through open public reasoning for influencing actual social states. Indeed, the successes and failures of democratic institutions in India can be easily linked to the way these institutions have—or have not—functioned. Take the simplest case of success (by now much discussed), namely, the elimination of the large-scale famines that India used to have right up to its independence from British rule. The fact that famines do not tend to occur in functioning democracies has been widely observed also across the world.

How does democracy bring about this result? In terms of votes and elections there may be an apparent puzzle here, since the proportion of the population affected, or even threatened, by any famine tends to be very small—typically less than 10 percent (often far less than that). So if it were true that only disaffected famine victims vote against a ruling government when a famine rages or threatens, then the government could still be quite secure and rather unthreatened. What makes a famine such a political disaster for a ruling government is the reach of public reasoning and the role of the media, which move and energize a very large proportion of the general public to protest and shout about the ‘uncaring’ government when famines actually happen—or come close to happening. The achievement in preventing famines is a tribute not just to the institution of democracy, but also to the way this institution is used and made to function.

Now take some cases of lesser success—and even failure. In general, Indian democracy has been far less effective in dealing with problems of chronic deprivation and continuing inequity with adequate urgency, compared with the extreme threats of famines and other emergencies. Democratic institutions can help to create opportunities for the opposition to demand—and press for—sufficiently strong policy response even when the problem is chronic and has had a long history, rather than being acute and sudden (as in the case of famines). The weakness of Indian social policies on school education, basic health care, elementary nutrition, essential land reform, and equal treatment of women reflects, at least partly, the deficiencies of politically engaged public reasoning and the reach of political pressure. Only in a few parts of India has the social urgency of dealing with chronic problems of deprivation been adequately politicized. It is hard to escape the general conclusion that economic performance, social opportunity, political voice, and public reasoning are deeply interrelated. In those fields in which there has recently been a more determined use of political and social voice, there are considerable signs of change. For example, the issue of gender inequality has produced much more political engagement in recent years (often led by women’s movements in different fields), and while there is still a long way to go, this development has added to a determined political effort at reducing the asymmetry between women and men in terms of social and economic opportunities.

There has been more action recently in organized social movements based broadly on demands for human rights, such as the right to respect and fair treatment for members of low castes and the casteless, the right to school education for all, the right to food, the entitlement to basic health care, the right to information, the right of employment guarantee, and greater attention on environmental preservation. There is room for argument in each case about how best to proceed, and that is indeed an important role of democratic public reasoning, but we can also see clearly that social activities are an integral part of the working of democracy, which is not just about institutions such as elections and votes.

A government in a democratic country has to respond to ongoing priorities in public criticism and political reproach, and to the threats to survival it has to face. The removal of longstanding deprivations of the disadvantaged people of our country may, in effect, be hampered by the biases in political pressure, in particular when the bulk of the social agitation is dominated by new problems that generate immediate and noisy discontent among the middle class Indians with a voice. If the politically active threats are concentrated only on some specific new issues, no matter how important (such as high prices of consumer goods for the relatively rich, or the fear that India’s political sovereignty might be compromised by its nuclear deal with the United States), rather than on the terrible general inheritance of India of acute deprivation, deficient schooling, lack of medical attention for the poor, and extraordinary undernourishment (especially of children and also of young women), then the pressure on democratic governance acts relentlessly towards giving priority to only those particular new issues, rather than to the gigantic persistent deprivations that are at the root of so much inequity and injustice in India. The perspective of realization of justice is central not only to the theory of justice, but also to the practice of democracy.

To conclude, the idea of justice links closely with the enhancement of human lives and improving the actual world in which we live, rather than taking the form, as in most mainstream theories of justice today, of some transcendental search for ideal institutions. We will not get perfect institutions, though we can certainly improve them, but no less importantly, we also have to make sure, with cooperation from all sections of the society, that these institutions work vigorously and well. Engagement with reasons of justice is particularly critical in identifying the overwhelming priorities that we have to acknowledge and overcome with total urgency. A good first step is to think more clearly—and far more often—about what should really keep us awake at night.

This extract from The Country of First Boys is a slightly abridged and edited version of the inaugural Professor Hiren Mukerjee Memorial Annual Parliamentary Lecture, titled ‘Demands of Social Justice’, delivered in the Central Hall of Indian Parliament on 11 August 2008. It first appeared in The Little Magazine: Speak Up , volume VIII, issues 1 and 2 (2009), pp. 8–15.

Featured image: Sandstone Hills crevasse. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post On Indian democracy and justice appeared first on OUPblog.

Climate change and the Syrian refugee crisis: being honest about root causes

What should we make of Chancellor George Osborne’s recent claim that we need a “comprehensive plan” to address the burgeoning Syrian refugee crisis, a plan that addresses the “root causes” of this tragic upheaval? The UK government’s way of framing the issue is not unique. Many other governments as well as political pundits of various ideological stripes have been urging us to see the issue in precisely these terms. Invariably, such responses point to the twin evils of Bashar al-Assad and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) as the fundamental problems. In Osborne’s case this identification is then used as justification for advocating the expansion of RAF strikes into Syria (among other things, like creating ‘safe havens’ for refugees). Assad is surely evil—ISIL no less so—but are they alone the “root causes” of the refugee crisis in Syria and beyond? The answer is no.

Whether we are talking about immigrants seeking to enhance their economic prospects or refugees fleeing political repression, human migration is an extraordinarily complex phenomenon. Large-scale migration is rarely traceable to a single root cause. For example, evidence is now mounting that the flow of refugees out of Syria was preceded by a huge internal displacement of people and that the key cause of this internal flow was anthropogenic climate change. In a landmark study published in 2015 researchers have established causal links between climate change and the following events: (a) historically unprecedented drought conditions in Syria beginning in 2007; (b) huge agricultural failure in the region; (c) the migration of some 1.5 million people from rural to urban areas in Syria; and (d) the civil unrest that festered on the peripheries of these urban areas as Assad ignored the emerging problems of crime, overcrowding, unemployment, and an increasingly violent struggle for dwindling resources. When people protested, Assad turned violently on them, deepening and spreading the chaos.

Lebanese Town Opens its Doors to Newly Arrived Syrian Refugees by UNHCR Photo Download. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr

Lebanese Town Opens its Doors to Newly Arrived Syrian Refugees by UNHCR Photo Download. CC BY-NC 2.0 via FlickrThe problem is, moreover, likely to get worse, and not just in Syria. The age of climate change is going to be the age of human displacement, though we can’t be certain just how many people will be on the move. This demographic alteration should put enormous pressure on governments to behave in ways that do not exacerbate social conflict, and obviously not all of them will be able, or inclined to do so. Assad may be just the first in a long line of dictators whose repressive actions are enabled by the environmental effects of climate change.

So how should we respond to this new reality, now and in the future? At the risk of substituting one over-simplified root-cause explanation with another, here’s a deliberately provocative counterfactual. Absent the climate change that we in the rich part of the world have mostly caused, there would have been no large-scale internal displacement of Syrian people from rural to urban areas over the last 10 years or so, hence little ensuing urban unrest, in which case Assad would likely not have been provoked to attack his own citizens. As a result, there would have been far less scope for ISIL to operate and no significant refugee crisis. In other words, our failure to curb our carbon emissions is an undeniable part of the larger story here. If we are going to talk of root causes let’s at least do so in a genuinely comprehensive way rather than cherry-picking the facts to fit a particular policy agenda.

Government officials can claim to accept the science of climate change and yet fail resolutely to notice some of its thornier ramifications, like increased migration and civil conflict in certain parts of the world. Other things equal, you are morally responsible for ameliorating harms you are causally responsible for producing. This homely truth has immense ethical implications for how we in the industrialized world respond to crises like these. For one thing it places an obligation on many of us to increase the number of refugees we are prepared to accept. Germany’s plan to take in 800,000 this year is a model target, whereas the UK’s 20,000 over the next five years is clearly inadequate on moral grounds. But being honest about the role played by climate change in creating refugees also serves to focus the mind on real solutions. Because it does nothing to address the climate crisis, bombing malefactors like Assad into submission is not the far-sighted and comprehensive plan its advocates take it to be. Taking the genuinely long view here requires (a) decarbonizing the global economy as quickly as possible; and (b) working on humane and intelligent schemes for adaptation—including a commitment to resettle refugees on an unprecedented scale—to the changes that are now unavoidable.

Headline image: CO2 emissions by freefotoukCC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr

The post Climate change and the Syrian refugee crisis: being honest about root causes appeared first on OUPblog.

Announcing Place of the Year 2015 longlist: vote for your pick

Today we officially launch our efforts to decide on what the Place of the Year 2015 should be, coinciding with the publication of the Atlas of the World, 22nd edition–the only atlas that’s updated annually to reflect current events and politics.

We asked our colleagues at Oxford University Press for their help, and they all came back with both interesting and significant nominations. So now we open up the question to you: What do you think is 2015’s Place of the Year? Vote in the poll below by 31 October. Or, if you think there’s a place we missed, let us know in the comments.

Place of the Year 2015 longlist

Keep checking back on the OUPblog, or follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr for regular updates and content on our Place of the Year 2015 contenders.

Headline image credit: Photo by artistlike. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Announcing Place of the Year 2015 longlist: vote for your pick appeared first on OUPblog.

Consumer reactions to attractive service providers

Imagine that you are going to buy a health care product. You see a highly attractive salesperson. What would be your reaction? Would you feel very happy? Would you spend more time interacting with the salesperson and be more likely to buy his/her products?

There is a common belief that people have very favorable reactions to physically attractive individuals. People think that attractive individuals are intelligent and sociable. They love to be around them and to be friends with them. Therefore, consumers should be more willing to interact with and buy products from an attractive salesperson than an average looking one. As our research indicates, however, this may not always be true. Customers may react more negatively to a highly attractive service provider than to an average looking one.

Specifically, we find that attractive service providers can sometimes lead consumers to have self-presentation concerns (that is, concerns about their ability to make a good impression on others). When this is true, they often avoid interacting with physically attractive providers and so the providers are relatively ineffective. The processes that underlie this effect can depend on whether the consumer and provider are the same or the opposite sex. When the provider is of the opposite sex, consumers are likely to experience evaluation apprehension and their willingness to interact will decrease. When the provider is of the same sex, however, consumers are likely to compare themselves with the provider and perceive themselves as relatively unappealing. In this case, they will dislike the provider and be unwilling to interact for this reason. Thus, self-presentation concerns will generally decrease consumers’ willingness to interact with a highly attractive service provider, but the reason depends on whether the provider is of the same or opposite sex. If consumers do not experience these self-presentation concerns, however, they will be more likely to approach an attractive provider than an average looking one.

A pilot study, five field and laboratory experiments confirmed these effects.

In a pilot study, we conducted an observational study at a store in a Hong Kong shopping center (Richmond Shopping Arcade) that specializes in Japanese figures, models, and gifts, and is a popular place for Otaku to shop. Otaku is a group of HK Chinese who are believed to have chronically high social anxiety. People with high social anxiety in general have stronger self-presentation concerns than those with low anxiety. As we predicted, fewer Otaku males made a purchase when the female salesperson was attractive than when she was average looking in a toy store. We also conducted an observational study at a hospital where a display of health care products were being sold. We found that female consumers were more likely to interact with a physically attractive male salesperson than with an unattractive one when they were buying non-embarrassing products (i.e. a foot insole) but were less likely to do so if they are buying embarrassing products (i.e. a thermal waist belt to facilitate weight loss). This was because embarrassing products are more likely to activate self-presentation concerns. Our laboratory studies replicated these findings. Interestingly, in opposite sex interactions, embarrassing consumption does not have a negative impact on consumers’ liking of the attractive service providers; it only reduces their willingness to interact with him/her. However, in same sex interactions, embarrassing consumption increases consumers’ feelings of jealousy and negative mood, decreases their self-perceptions of attractiveness and decreases their liking of the attractive service providers; therefore, reduces their willingness to interact with him/her.

Customers may react more negatively to a highly attractive service provider than to an average looking one.

Our research is the first attempt to examine the conditions in which the physical attractiveness of a service provider can decrease as well as increase consumption behavior. As such, it sheds new light on the physical attractiveness and embarrassment research. We also distinguished two different processes of self-presentation concerns underlying the same and the opposite sex interactions: self-presentation motives are sexually driven when an opposite-sex provider is physically attractive, but are driven by social comparison processes when a same-sex provider is attractive.

In addition, our research places constraints on the desirability of using attractive service providers to increase the sale of products. This strategy may indeed be effective when the product being promoted is not embarrassing. It can have an adverse effect, however, when the purchasing of the product is embarrassing. That said, it is important to note that the negative impact of attractive service providers is restricted to face-to-face situations in which the motive to create a favorable impression is relatively high. The use of attractive models or celebrities in advertisements for embarrassing products could have a positive effect on online shopping in which social interaction is not an issue.

Featured image credit: Stairs shopping mall by jarmoluk. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Consumer reactions to attractive service providers appeared first on OUPblog.

Learning to listen

If your experience of school music was anything like mine, you’ll recall those dreaded aural lessons when the teacher put on a recording and instructed you to identify the instruments, to describe the main melody, to spot a key change, perhaps even to name the composer. In my case, this tortuous experience continued into my late teens when, as a music undergraduate at Cambridge, I was compelled to take a paper in aural skills. The ultimate challenge of the final examination was aural dictation, during which we were played an atonal melody that we had to notate. It was an exercise dreaded by almost all by peers, and one that seemed manifestly unfair on those of us who lacked perfect pitch. So why was I taught to listen in this way? What is more, throughout the rigorous training, I was rarely, if ever, asked to exercise the same attentiveness to recordings of popular music. Why not?

This pedagogic practice has its roots in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when the question of how people listened to music – especially art music – became a hot topic among British intellectuals. As a more centralized mode of governance and changes to the voting system put democracy high on the political agenda, culture was increasingly thought about in relation to the rights and duties of Britain’s newly enfranchised public. Indeed the study of music came to be seen not just as something to which people were entitled, but also “as part of their preparation for ‘the responsibilities of citizenship’.”

At the same time, this was an era when technological advances were creating novel ways of accessing music. First the advent of gramophone, then radio meant that musical performance no longer required the presence of a musician. Even large-scale forms, such as symphonies and operas, could for the first time be listened to from the comfort of the home. These developments held huge promise for those seeking to broaden access to art music, but they also threatened to loosen intellectuals’ hold on high culture. In particular, intellectuals feared that disseminating art music via emerging mass media might tarnish it with the negative connotations of popular music, which they frequently dismissed as too commercial and aesthetically inferior.

Some – perhaps most famously Schoenberg – responded to this situation by disavowing mass media and priding themselves on the niche appeal of their art. Others were more optimistic and sought to instil in the public a love of great music. Soon the disjointed efforts of the more inclusively minded music educators began to gather momentum, to the point where they coalesced under the banner of “the music appreciation movement.”

Motivating these cultural pioneers was a belief that the public’s tendency to listen in a “passive,” inattentive way could be combated if they were given tools that facilitated a more “active,” “intelligent” appreciation. There was a fine balance to be struck here. Overly intellectual approaches were considered as superficial as overly emotional ones, but since acquiring factual knowledge about music was an easy way of measuring progress, music educators often ended up focusing on the rudiments of music theory and practice: the names of the instruments, harmony, rhythm, tonality, and form.

Such concerns were not uniquely British. In an age of increasing mobility, the drive to create larger audiences for art music played out in a transatlantic arena. The perceived need to teach the public to listen “properly” took on a nationalist dimension. British and American music educators watched one another closely. Sometimes they exchanged ideas, as for example at the Anglo-American music educators conferences inaugurated in the late 1920s. Other times they used one another as a benchmark of success, comparing not only whose concert halls were fuller (a competition in which America usually came out on top), but also how audiences responded to the musical fare.

Initially reliant on printed media, lectures, records, and educational concerts, the music appreciation movement burgeoned with the growth of radio. However, it arguably reached its pinnacle in the 1940s, when two music education films were produced whose impact is still felt today: in the United States, Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940), and in Britain, the Ministry of Education’s Instruments of the Orchestra (1946), for which Benjamin Britten wrote the music, now better known as The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra.

In many ways, these two films capture the differences in how music appreciation had evolved in the two countries. Walt Disney’s lesson is an imaginative feature-length adventure in Technicolor, in which human beings interact with cartoon characters.

In contrast, the Ministry’s is an austere, black-and-white short, the only playfulness here coming from the effervescent moments in Britten’s score.

Still from the filming of Instruments of the Orchestra, 1946. Reproduced with permission of the British Film Institute.

Still from the filming of Instruments of the Orchestra, 1946. Reproduced with permission of the British Film Institute.If Disney’s creation holds more obvious appeal for children, such a whimsical mix of art music and animation would perhaps have been a step too far for even the most open-minded of Britain’s intellectuals.

The postwar era marked the passing of the first generation pioneers of music appreciation but their legacy remains strong to this day. It continues to shape musical instruction both in school and universities. At a time when the place of the arts in British education is under constant scrutiny, reflecting on the history of our education system might provide a useful perspective. It might help us to discover where we’ve come from; to understand why we teach art and popular music the way that we do, and perhaps even to imagine alternative ways of teaching that are less bound by cultural ideologies inherited from the past.

Featured image: Guitar, Strings by MonkeyMoo. CC0 via Pixabay

The post Learning to listen appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers