Oxford University Press's Blog, page 605

October 12, 2015

Can you get X out of X in our Latin poetry quiz?

The shadow of the Roman poets falls right across the entire western literary tradition: from Virgil’s Aeneid, about the fall of Troy, the wooden horse, and the founding of Rome; through the great love poets, Catullus, Propertius, and Tibullus; Ovid’s Metamorphoses, treasure-house of myth for the Renaissance and Shakespeare; to Horace’s Dulce et decorum est, echoing through the twentieth century. We all take it for granted … so now’s the time to check your working knowledge.

Audentis Fortuna iuvat!

Featured image credit: ‘Virgil Reading the Aeneid to Augustus, Octavia, and Livia’. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Quiz image credit: Rome: View of the Colosseum and The Arch of Constantine by Antonio Joli. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Can you get X out of X in our Latin poetry quiz? appeared first on OUPblog.

The power of the algorithm

Recently Google Inc. was ordered to remove nine search results after the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) ruled that they linked to information about a person that was no longer relevant. Almost ten years ago, that individual had committed a minor criminal offence and he recently put a request to Google that related search results be removed, in compliance with the decision of the European Court of Justice relating to Google Spain. Google removed the links and this became a news story. Journalistic content including the individual’s name and details of the original criminal offence started featuring in search results. It was this second set of search results that the ICO ordered Google to remove, despite their claim that these articles were essential to a recent news story on a matter of significant public importance.

In line with the European Court, the ICO confirmed that links prompted by searching on an individual’s name are ‘data processing’ for the purpose of data protection law, and a person has a right to request the removal from the search results of information about themselves that is no longer relevant. In Google Spain, the scope that the European Court gave to the right to erase personal information is remarkably broad. It covers instances where personal information has been initially made available on the Internet legitimately, or where the information is true, as well as instances where the inclusion of the information in search results does not cause any prejudice to the person.

One of the most significant contributions of this case was that, to an extent, it introduced a right of informational self-determination in that individuals can have an active role in the determination of the way in which their personal information is presented online. This exceeds the scope of informational privacy, and the narrowly defined ‘right to be forgotten’ as featuring in the proposed Data Protection Regulation.

How far does this new right go? Delisting search results is only one of many functions for which search engines have been called to take responsibility. However, their obligation to remove personal information also extends to other services provided in the course of the searching process. One of those services, perhaps the most influential one, is the autocomplete function. This is the algorithm that ‘predicts’ the words you would enter in the search bar while you are still typing, and suggests possible word-combinations. Although the algorithm obviously makes searches easier and faster, it has become source of litigation in various jurisdictions in cases where automated suggestions appeared to convey a deceptive or defamatory meaning, or to prompt the search in ‘wrong’ directions.

In Germany, for instance, defamatory autocomplete suggestions should be removed upon request, after a man won a lawsuit against Google for his name being associated with the words ‘scientology’ and ‘fraud’ in Google’s autocomplete function, claiming these were defamatory insinuations. In its decision, which was issued a year before Google Spain, the Federal Supreme Court found that the autocomplete function creates an expectation to Internet users. Because the algorithm-driven search program incorporates the searches previously made by other users, and presents current users with the combination that is most frequently appearing in search results, users expect that the suggestions are informed by real content and hence have an informative meaning. This is true, despite the fact that there may not be search results confirming the suggestion.

The Google Spain decision expands the scope of requests for removal of autocomplete suggestions both in a procedural and substantial way. All major search engine operators have already put in place a ‘notice and take down’ procedure, similar to the one adopted in some jurisdictions for claims on copyright infringement, to deal with requests of removal of search results. Google has recently included, for users browsing from the EU, a separate procedure to request the exclusion of ‘offensive predictions’ made by its autocomplete function.

From a substantial point of view, the Google Spain decision has extended the ground to request removal to instances where autocomplete suggestions do not even convey a defamatory meaning or false factual information. Applications for injunctive relief regarding the misuse of personal information may now be successful. Readers may remember the case of Max Mosley, the former head of Formula One involved in a British tabloid sex scandal in 2008. Mr Mosley’s application for an injunction against News Group Newspapers was refused in 2008, because the relevant material had become so widely accessible that there was no longer a reasonable expectation of privacy in relation to it, or it would make little practical difference to accept the application. Google Spain gave Mr Mosley a new opportunity to seek the removal of those photographs from search results (as well as the removal of the results from autocomplete suggestions) on the basis of ‘a viable claim which raises questions of general public interest, which ought to proceed to trial’.

Whereas it is true that censoring search results can be dangerous and is for various reasons unwelcome, there are instances where purely algorithmic operations may violate the rights of individuals. On one side, there are arguments in favour of the protection of the fundamental freedoms of speech and uncensored access to information online. On the other side, personality rights on the Internet ought to be preserved, especially where their processing is disproportionate to the legitimate aim of facilitating the search of information online.

Conflicts of rights in this context shed new light on the seemingly settled issue of search engine liability. Search engines are the less and less neutral carriers of information and may act as publishers, as content providers and as data controllers. In their role as primary information gatekeepers of the web, they have an enlarged duty to comply with individuals’ requests to participate in the way in which information about themselves is organized and presented.

Featured image: ‘BalticServers data center. Photo by BalticServers.com (Fleshas). CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The power of the algorithm appeared first on OUPblog.

On the unstoppable rise of vineyard geology

The relationship between wine and the vineyard earth has long been held as very special, especially in Europe. Tradition has it that back in the Middle Ages the Burgundian monks tasted the soils in order to gauge which ones would give the best tasting wine, and over the centuries this kind of thinking was to become entrenched. And why not? The vines were manifestly taking up water from the soil, and, presumably, with it everything else that they needed to grow and make grapes. The belief that the vineyard soil was central to wine flavour was simply self-evident. It seemed wine was made of the soil.

However, eventually there was the discovery of photosynthesis – that in fact vines are chiefly manufactured, as it were, from sunshine, air and water – but this didn’t really dent the popularity of the soil idea. Scientifically, we now know that while the vineyard geology – the rocks and soils in which the grapevines are rooted – supplies some of the vine’s (modest) nutritional needs, its main role is to do with providing the right amounts of water. In some circumstances there may be other effects, such as the thermal behaviour of the soil surface and the influence of alkalinity on microbiology, and certain grape cultivars do seem to prefer particular conditions. But scientifically it seems the primary influence of the geology on the vine, and hence indirectly on wine flavour, is in providing good drainage while at the same time possessing ways of conserving water for times of need. In fact these water matters are so important that in practice today they are routinely and precisely engineered with artificial drains and irrigation (just as the other factors are manipulated), which would seem to rather undermine the pre-eminence of the natural geology.

Nevertheless, despite this, the proposition that the vineyard geology shapes the eventual wine has nowadays risen to unprecedented heights. All over the world, remote-sensing technologies are being used to pinpoint variations in geological properties; vineyards are being peppered with soil pits. Of course, it all chimes with the current yearning for more “natural” foods and knowledge of provenance: through bestowing a “sense of place”, a wine said to depend on its vineyard geology offers immeasurable marketing possibilities. After all, the geology is one of the few things in wine-making that cannot easily be replicated elsewhere. Thus growers all over the world enthusiastically claim that their particular vineyard geology is wholly unique, and consequently their wines so very special.

Photograph courtesy of Alex Maltman. Do not use without permission.

Photograph courtesy of Alex Maltman. Do not use without permission.It is now almost de rigeur to at least mention the geology in vineyard descriptions. Back-labels on wine bottles pronounce such things as: “the chateau is on sandy limestone from the Cretaceous period”; “the wine speaks of the vineyard’s granitic soil”; “the vines grow on argilo-calcareous soils with sea-shell fossils”; and (most impressively) “our vineyard has Triassic and Jurassic sediments on undulating Proterozoic granulite and migmatite with numerous dolerite dykes”. Some wine writers believe that the geology can actually be tasted in the wine: “you can taste the volcanic ash of nearby Vesuvius”; “wine allows me to taste soil and bedrock”; “a “graphite or schisty-ness flavor which I identify as coming from the soil of the Priorat”; “in Brouilly, there are veins of blue granite nuanced in the wines”.

And now, arcing over all this like a newly discovered comet in the night sky, we have the concept of minerality. This idea of tasting minerals in the wine glass is brand new. Suddenly, tasting notes not only declare wines to be ‘full of minerals’, ‘mineral laden’, ‘brimming with minerals’ and the like but even particular geological minerals are specified – as in a quartz, gypsum, or graphite minerality, or certain rocks -as in a chalky, slaty or granite minerality.

So, although the scientific basis has not changed, today in the world of wine there is a new level of interest in things geological. Now wine lovers need to know their tuff from their tufa, and their slate from their schist; writings about Burgundy’s Côte d’Or enthuse about colluvium and argilo-calcaire; numerous wines are named after varieties of rock – greywacke, orthogneiss, amphibolite, and mylonite among them. In view of all this, I imagine that those Burgundian monks would be highly pleased with their legacy!

The post On the unstoppable rise of vineyard geology appeared first on OUPblog.

October 11, 2015

Words from books

October is an important month for book festivals—in Boston, Austin, Madison, Baton Rouge, and of course Frankfurt, Germany, which hosts the world’s oldest book festival. In honor of these book festivals, I want to delve a bit into the way that the language of books expanded the English vocabulary.

The earliest books were not books per se, but inscriptions on stone or wood. The term stele, for an upright stone, wooden slab, or clay, is still a very specialized term. Soon, however, clay, wooden tablets, and papyrus scrolls made writing more portable. Fast forward to today, when tablets now refer to computers and we scroll on our computer screens, tablets, and phones. The meaning of both words has been extended to follow changes in reading technology.

Clay tablets did not need tables of contents, but papyrus scrolls left us the term syllabus, which comes to us from the Greek word sillybos, a label affixed to a scroll giving its contents. The Romans used the term titilus instead, from which we get title. The scrolls themselves were kept in a wooden jar—stacking was not an option—which was known in Greek as a bibliothek (from biblion for “book” + theke meaning “case”), which has become the word for “library” in various languages.

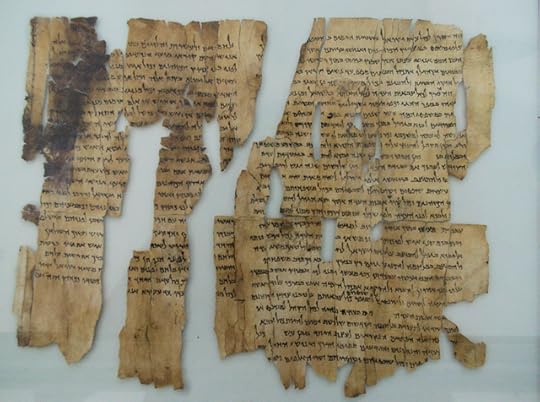

Image credit: “Dead Sea Scroll — The World’s Oldest Secrets” by Ken and Nyetta. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: “Dead Sea Scroll — The World’s Oldest Secrets” by Ken and Nyetta. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The prefix biblio-, of course, also shows up in a variety of book-related words—like bibliophile and bibliography. Bible is a biblio-variant that took on a specialized religious association but has been used figuratively to mean any authoritative book since the early 1800s. Less durable has been the word tome, referring originally to the cut scrolls of papyrus. Tome has the same root as atom or appendectomy and is used today to mean a physically or intellectually weighty book.

Papyrus gave way to parchment and eventually to paper, which made its way from China to the Middle East to Europe. Early books were handwritten and hand-copied, giving us the term manuscript, which now simply refers to the original text of a work.

In early manuscripts, uniform handwriting was at a premium (since a book might be produced by many scribes) and there was no modern punctuation. Instead, sentences were separated by making the first letter larger and sometimes coloring it red, a process known as rubrication. Later religious works included directions in red and rubric came to mean an established custom. In present-day universities, the word has evolved to indicate a scoring guide that lays out grading expectations.

The Old English word bōc (“book”) has a Germanic origin most likely from the word for the beach tree, the material of early wooden writing tablets. The word text, indicating the wording of something, makes an appearance in English in the late fourteenth century, from the French word texte and related to the Latin word for something woven. Text was extended to encompass original or authoritative works, then to the idea of anything that can be read as a text, and in more recent times, has been converted to a verb as a shortening of “to send a text-message.”

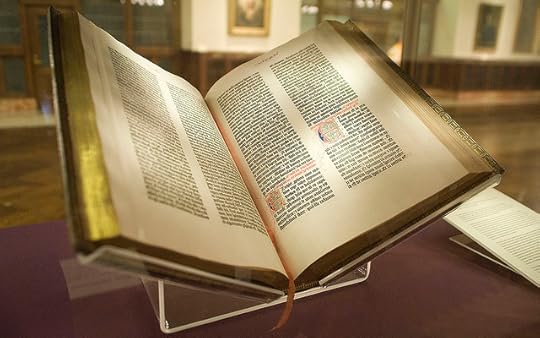

“Gutenberg Bible” by NYC Wanderer. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Gutenberg Bible” by NYC Wanderer. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.The insights of Johannes Gutenberg and fifteen other artisans revolutionized book production with uniform movable type, adapting the technologies of olive oil and wine making (the press) as well as coin and jewelry making (the fabrication of letters). The letters or characters used in printing were soon referred to as type, from the Greek word for “impression” or “mark.” Like all novel technologies, printing with movable type was quickly and continuously refined through the Renaissance and into the Industrial Revolution. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, further technological innovations improved the efficiency of printing, moving from wooden presses to iron ones and from continually reset type to the process of stereotyping, where a mold was made of a page of set type. The mold could be stored and reused for future printings. A stereotype came to mean something repeated without change and later, a preconceived oversimplification.

By the mid-nineteenth century, printmakers had developed a method of making uniform type automatically—a process known as type-casting, tripling the speed with which type could be made and setting the stage for automatic typesetting. It was not long before the meaning of typecast was extended to refer to the casting of actors in a certain roles. And by the late 1800s, we had the noun typewriter and the back-formed verb typewrite, later shortened to just type, bringing us full circle.

So as you browse the publisher’s offerings at your local book fair—wherever that might be—take a moment to appreciate not just the words on the page but the words that printing and publishing have contributed to the English language.

Image Credit: “Stockholm Public Library” by Samantha Marx. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Words from books appeared first on OUPblog.

Clement Attlee and the bomb

As the new leader of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, wrestles with his own beliefs about nuclear weapons and those opposing beliefs of many members of the Shadow Cabinet, it is interesting to look back to the debates which took place in the Labour Government of Clement Attlee in the immediate post-war period.

Despite being a member of the wartime Cabinet, Attlee had little knowledge of the Manhattan project and the development of the atomic weapons that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. When he became Prime Minister shortly afterwards he was immediately faced with the question of whether Britain should become a nuclear power itself. In these early days before the Cold War gathered momentum, the Attlee government had a major dilemma: whether to pursue an internationalist or a nationalist agenda. He recognised that the modern conception of war to which his generation had become accustomed was now ‘completely out of date’ in the nuclear age. If the world lapsed into a major war again he believed that every weapon available would be used resulting in ‘the destruction of great cities and, in the deaths of millions.’It seemed to him that some form of deterrence was the only answer, but what if deterrence broke down?

The Prime Minister’s initial conviction was that every effort had to be made to bring about some form of international control. He told his Cabinet that “time is short…only a bold course can save civilization.” As a result he decided to take the initiative and write to President Truman. In his letter he told the US President that “the world was now facing entirely new conditions” and if the international community was to “rid itself of this menace” far-reaching changes in the relationship between states would be necessary. It was important he said to “bend our utmost energies to secure a better ordering of human affairs which so great a revolution at once renders necessary and should make possible.” He appreciated that there would be risks involved in associating the Soviet Union in this process, but in the new circumstances “acts of faith” were called for.

Harry Truman, Clement Attlee and Mackenzie King boarding the USCG Sequoia to discuss the atomic bomb by BiblioArchives / LibraryArchives. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

Harry Truman, Clement Attlee and Mackenzie King boarding the USCG Sequoia to discuss the atomic bomb by BiblioArchives / LibraryArchives. CC BY 2.0 via FlickrIn the time prior to Attlee’s meeting with President Truman to discuss these radical ideas a major debate took place in the British Cabinet about the question of international control. The Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, told colleagues that Britain had “everything to gain and little to lose by making Russia party to knowledge of the atomic bomb process.” It would be worth, he argued, “trusting to their good faith” by negotiating an international control agreement. These views were shared by other members of the Labour Cabinet at the time.

When Attlee met Truman (and the Canadian leader, Mackenzie King) in November 1945 he argued that “a real attempt must be made to build a world organisation upon the abandonment of power politics.” Alongside these beliefs in the need for radical change, however, Attlee also recognised that, as Prime Minister, he had to make sure he looked after Britain’s national interests, until such a time as the desired changes in international politics were actually achieved. In the Washington Declaration which followed the meeting the importance of pursuing international control was stressed but at the same time a secret agreement was made to share scientific research between the three states. By this time, Attlee and the other leaders were beginning to wonder whether sharing nuclear secrets with the Soviet Union would be such a good idea after all.

Here we see the contradictions at the heart of Attlee’s dilemma. His lofty and noble thoughts of putting aside nationalist ideas came directly into conflict with the sober calculations of Realpolitik. Although the Western powers and the Soviet Union pursued the aim of international control for a number of years in the late 1940s, increasingly different national perspectives dominated the discussions rendering it unachievable. As the Cold War gathered momentum the Labour government of Clement Attlee took the decision in 1947 to develop a British nuclear deterrent which has continued down to the present day. Faced with the harsh realities of world politics internationalism gave way to nationalism.

It remains to be seen whether the contemporary Labour Party faced with a similar dilemma can resolve it any better than their predecessors did nearly seventy years ago.

Headline image: HMS Edinburgh Fires Final Sea Dart Missiles by Defence Images. CC BY-NC 2.0 via Flickr

The post Clement Attlee and the bomb appeared first on OUPblog.

Reasonable suspicion for arrest in the era of Operation Midland

On 21 September 2015 the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) released a statement into Operation Midland. Within this statement the MPS provide a description of the current practice of investigating claims of child sexual abuse or serious sexual assault: “Our starting point with allegations… is to believe the victim until we identify reasonable cause to believe otherwise.”

The practical reasons for such a position are clear; those who have suffered an assault of this nature are likely to be vulnerable, and it is beyond doubt that disclosing information of this sort to a police officer can be a highly traumatic experience. By adopting this start point, the MPS provide immediate support and reassurance to complainants; Operation Midland provides a demonstration of this policy in practice:

“…At the point at which we launched our initial appeal on Midland, after the witness had been interviewed for several days by detectives specialising in homicide and child abuse investigations, our senior investigating officer stated that he believed our key witness and felt him to be ‘credible’. Had he not made that considered, professional judgment, we would not have investigated in the way we have”.

“We must add that whilst we start from a position of believing the witness, our stance then is to investigate without fear or favour, in a thorough, professional and impartial fashion, and to go where the evidence takes us without prejudging the truth of the allegations”.

Grounds for Arrest / Reasonable Suspicion

Does a starting point of belief, in the absence of further investigation, meet the test of reasonable suspicion in the absence of other evidence?

The power of arrest (without warrant) is contained within s. 24 Police and Criminal Evidence Act:

1. A constable may arrest without a warrant—

i. Anyone who is about to commit an offence.

ii. Anyone who is in the act of committing an offence.

iii. Anyone whom he has reasonable grounds for suspecting to be about to commit an offence.

iv. Anyone whom he has reasonable grounds for suspecting to be committing an offence.

2. If a constable has reasonable grounds for suspecting that an offence has been committed, he may arrest without a warrant anyone whom he has reasonable grounds to suspect of being guilty of it.

3. If an offence has been committed, a constable may arrest without a warrant—

i. Anyone who is guilty of the offence.

ii. Anyone whom he has reasonable grounds for suspecting to be guilty of it.

‘Reasonable suspicion’ is a low threshold, two stage test:

Does the arresting officer honestly suspect ‘A’ has committed the offence; and

Would a reasonable man be of that opinion, having regard to the information which was in the mind of the arresting officer.

The concern with the current MPS policy is simple – does a starting point of belief, in the absence of further investigation, meet the test of reasonable suspicion in the absence of other evidence? The first element of reasonable suspicion is subjective; it is concerned with what is in the mind of the officer at the point of arrest. This stage would seem to be met by MPS policy. If the arresting officer believes the complainant, then it follows that the officer would hold a reasonable suspicion that the suspect has committed the offence under investigation.

Therefore, we move to the second, and objective, test. Would a reasonable man, having regard to all the information, form the same view as the arresting officer? The reasonable man is not subject to MPS policy and therefore the starting point of belief cannot apply to this stage of the test. In itself, this causes difficulties as it is hard to see a position where an officer can ‘believe’ a complainant whilst objectively assessing the account. Therefore, MPS policy cannot differentiate between an offence subject to this policy and an offence which falls outside the scope of this policy. The objective test for reasonable suspicion must be met before a lawful arrest can be made.

The police may be reluctant to disclose information about the investigation on arrest. However, PACE Code C para 3.4(b) provides ample assistance to advisors seeking information:

“Documents and materials which were essential to effectively challenging the lawfulness of the detainees arrest and detention must be made available to the detainee or their solicitors. Documents and materials will be essential for this purpose if they are capable of undermining the reasons and grounds which make the detainees arrest and detention necessary”.

While the threshold for reasonable suspicion is low, if an arrest is based on the account of a complainant alone, those advising must be alive to this issue, to ensure that their client is not unlawfully detained.

Featured image credit: Traffic Car c.2012 by West Midlands Police. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reasonable suspicion for arrest in the era of Operation Midland appeared first on OUPblog.

A world with persons but without borders

How can contemporary Kantian philosophy help solve the current refugee crisis?

By “contemporary Kantian philosophy” I mean contemporary, analytically-rigorous philosophy that’s been significantly, although not uncritically, inspired by the 18th century philosophical writings of Immanuel Kant.

Here I’ll present an argument based on some highly-plausible Kantian metaphysical, moral, political premises, about a huge real-world problem that greatly concerns me: the global refugee crisis, including its current manifestation in Europe.

1. All human persons, aka people, are (i) absolutely intrinsically, non-denumerably infinitely valuable, beyond all possible economics, which means they have dignity, and (ii) autonomous rational animals, which means they can act freely for good reasons, and above all they are (iii) morally obligated to respect each other and to be actively concerned for each other’s well-being and happiness, aka kindness, as well as their own well-being and happiness.

2. Because the Earth is a sphere, because planetary spheres are finite but unbounded spaces with no inherent edges or borders, and because all people live on our planetary sphere within essentially interconnecting surface-spaces, they must share this Earth with each other.

3. People are embodied conscious animals living in forward-directed time, and living in spaces whose inherent directions (right-left, etc.) are all centered on, and determined by, the first-persons embedded in those spaces.

4. In order to live, and in order to live well and be happy, people need to be able to occupy certain special spaces in which they eat, rest or work, sleep, have intimate emotional relationships and/or families, etc., aka homes, and also to move freely across the surface of the Earth, without having their dignity or autonomy violated, and without violating others’ dignity or autonomy.

Image: Refugee-Solidaritätsdemo – Refugees are human beings by Haeferl. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image: Refugee-Solidaritätsdemo – Refugees are human beings by Haeferl. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.5. By virtue of the spherical shape of the Earth, by virtue of their embodiment, but above all by virtue of their dignity and autonomy, all people inherently belong to a single universal cosmopolitan moral community, aka humanity, that transcends any political state.

6. By sharp contrast, everyone also accidentally belongs to one or more arbitrarily-established social institutions, nation-states, that occupy arbitrarily-divided areas of the Earth’s surface, and are ruled by special groups of people called governments, whose rule is enforced by police and armies.

7. The function of governments is to issue commands of various kinds, without regard to their specific moral content, justified instead by political authority, backed up by force or the threat of force, aka coercion, for the purpose of protecting various self-interests of certain people specifically enclosed, governed, and controlled by that nation-state, call them citizens. Other people who live within these nation-states, and are also controlled by those states, but are not citizens of them, are foreigners.

8. The current refugee crisis is, first, caused by authoritarian, wicked governments of certain contemporary nation-states, e.g. Syria, and also by certain brutal insurgencies, themselves wannabe nation-states, e.g. ISIS, that are violating the dignity of innocent citizens and innocent foreigners living within various states, mistreating them in various ways, and often torturing or murdering them, leading to massive migration of those oppressed people, in order to survive and in search of a better life.

9. This crisis is also, second, caused by the existence of arbitrarily-established borders between other contemporary nation-states, expressing highly restrictive government-imposed travel and immigration policies in those states, e.g. Hungary, including many states that are comparatively quite well-off, or even very rich, and also significantly less authoritarian and/or wicked.

10. But, by virtue of their dignity, autonomy, and essential embodiment, people need homes, and they need to be able to move freely, and they also need to be treated with kindness by others, most obviously by those who live in immediately adjoining nation-states, but also by everyone on the face of the Earth, even if they live very far away from those others, e.g. in North America, simply because everyone shares the same spherical space of the Earth and because they all inherently belong to humanity.

11.Therefore the citizens of all relatively well-off, and significantly less authoritarian and/or less wicked nation-states in the world, especially including those in continental Europe, Scandinavia, the United Kingdom/British Isles, South America, and above all North America, should voluntarily do the following:

“each local community, as determined by a reasonable cadastral map of that country, guaranteeing fair distribution, should raise enough money to support one entire family, or, say, 4-10 people, and re-locate them to a safe place somewhere on the Earth, where their dignity and autonomy are respected and where they are treated with kindness, including finding them homes and providing them with free health care, schooling, a guaranteed minimal income, jobs, etc., and more generally, safe haven.”

Image: May Day Immigration March, by Jonathan McIntosh. CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image: May Day Immigration March, by Jonathan McIntosh. CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons.12. Ideally, the families or 4-10 people would be given safe haven in the particular local community that provides support for them. Since each re-located group would contain no more than 10 people, it would not constitute an “invasion of foreigners,” and since all re-located people would receive a new home, and experience the special benefits of safe haven in that local community, they would be extremely unlikely to move in large numbers and high concentrations to areas that lacked these special benefit.

13. This in turn would remove one major psychological trigger of nativist, xenophobic thinking, the irrational fear of Other-filled slums—the irrational fear of “District 9s.” But more generally, everyone should do their best to recognize and suppress in themselves, and to recognize and criticize in others, the irrationally fearful thinking expressed by such all-too-familiar slogans as “Foreigners get out!”, “Vas y étrangères!”, and “Ausländer raus!”

14. Once relocated to their new homes in safe havens, the refugee foreigners would be permitted to become citizens of the nation-state in which they had their new homes. But otherwise they would also be permitted autonomous freedom of movement anywhere within that nation-state, and more generally across the surface of the Earth, without borders, provided that they also respected the dignity and autonomy of all other members of humanity, and were prepared to treat them with very same sort of kindness that they themselves had received.

Featured image credit: Refugee Camp, by CDC. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A world with persons but without borders appeared first on OUPblog.

October 10, 2015

Do East and West Germans still speak a different language?

On 12 September 1990, about ten months after the Fall of the Berlin Wall, the foreign ministers of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) met with their French, American, British, and Soviet counterparts in Moscow to sign the so-called Two-Plus-Four Treaty. This paved the way for the German Reunification, which was finalized roughly one month later, on 3 October—the Tag der Deutschen Einheit (‘Day of the German Unity’)—when the five eastern states officially joined the FRG.

It’s now been 25 years since these events took place, and as Germany is looking forward to celebrating the anniversary of its reunification on Saturday, one can expect the German press to commemorate this special date as usual—with a myriad of articles exploring the differences that supposedly still exist between East and West. In the past, such discussions have typically focused on the question of whether the East German economy has finally caught up with the West’s (no, it hasn’t), but what about the linguistic legacy of the GDR?

German was, of course, the official language spoken in both the GDR and the FRG. But still, the two states weren’t just separated by a geopolitical border. GDR politicians were keen on forcing a linguistic division by creating a vocabulary that was supposed to distinguish them from their enemy neighbours—an attempt that frequently yielded humorous results.

A language division?

Unsurprisingly, a lot of the language used at that time reflected the GDR regime’s socialist ideology. For instance, the official name of the GDR was Arbeiter-und-Bauern-Staat (‘workers and peasants’ state’)—so called in accordance with the Marxist-Leninist world view of the East German state. Similarly, the Wall was officially known as Antifaschistischer Schutzwall (‘Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart’). The term Schutzwall has defensive connotations and is hence used euphemistically here, giving the impression that the people of the GDR had to be protected from an outside threat.

Socialist ideologies also infiltrated everyday language use. The lexicon of the GDR differed quite a bit from that of the FRG in that it deliberately borrowed words from Russian while the latter was awash with Americanisms, indicating the political alignment of each state. While in the West a space traveller was called Astronaut, to use an oft-cited example, in the East they said Kosmonaut, cognate with the Russian космона́вт. Furthermore, on weekends, the people of the GDR would spend time relaxing in their Datsche (‘summerhouse’), taken from Russian дача, or take part in a Subbotnik (fromсуббота ‘Saturday’), to do some (not quite) voluntary community work.

Apart from Russian loanwords, the GDR jargon was filled with convoluted technical terms. A canteen was referred to as a Werkküche (‘work kitchen’), a swimming pool turned into the equally political charged Volksschwimmhalle (‘people’s swimming hall’), and to order a side dish in a restaurant one had to ask for a Sättigungsbeilage (‘filling side dish’). There were no Krankenhäuser (‘hospitals’) in East Germany, but Polikliniken, and students attended a Polytechnische Oberschule (‘Polytechnic Secondary School’), the standard type of school in the school system of the GDR.

As the state wanted to promote atheism, words with religious connotations also had to be mostly avoided. Thus, Weihnachtsgeld (‘Christmas bonus’) became Jahresendsprämie (‘year-end bonus’)—a decision that led to the satirical coinage of the term geflügelte Jahresendsfigur (‘winged year-end figure’) for Weihnachtsengel (‘Christmas angel’). This term was, of course, not a word that people actively used as it is sometimes assumed. Its sole function was to parody the language politics of the GDR.

The linguistic legacy of the GDR

Having grown up in the eastern part of a unified Germany, such words sound as alien and comical to me as they probably would to someone from the West. Obviously, a lot of them lost their function because of the economic and political changes that took place after the collapse of the GDR. The Ausreiseantrag (‘exit visa’) became obsolete once the borders were opened and people were free to travel between East and West. You’d also have difficulties finding an Intershop anywhere in today’s East Germany—a shop where foreign goods and top-quality GDR goods were sold for freely convertible currency. But, with so many words now gone out of active use, are there any that have survived the Fall of the Wall?

For a start, although I do my shopping at the Supermarkt (‘supermarket’) nowadays, many East Germans are still familiar with the terms Konsum (‘cooperative shop’) or Kaufhalle (‘shopping hall’). Their usage, however, tends to be restricted to rural areas in East Germany only. I also use a Plastetüte (‘plastic bag’), rather than a Plastiktüte to pack my shopping. These two words in particular might seem innocuous to an outsider, but for Germans the Plaste vs. Plastik question constitutes a national controversy. (I’ll stop here without elaborating further.)

You also need to be careful with your answer when asked what time it is. Saying Viertel Neun (‘quarter nine’) or Dreiviertel Neun (‘three quarters nine’) instead of Viertel nach Acht (‘quarter past eight’) or Viertel vor Acht (‘quarter to eight’) is often assumed to be an East German peculiarity. I’ve sat through many discussions with West German friends, trying to explain to them the logic behind these expressions—often to no avail. However, it is a misconception that this is an East/West issue. East Germans generally understand and use both forms, but these are regional variants that also exist in parts of West Germany.

Leistungskontrolle (‘efficency control’) and Kurzkontrolle (‘short control’) are more unlikely to sound familiar to a West German. In East German schools, that’s still what we call exams or short tests. We also had a Polylux at school, which was the generic name for Overheadprojektor (‘overhead projector’) in the GDR, that is still widely used today. In fact, the word is so popular in the East that I remember my university professor being thoroughly mocked when he referred to the device with its more common name Overheadprojektor.

Growing together

While these are some terms from the former GDR that are still in use, it would be wrong to assume that their usage was restricted to the eastern part of the Federal Republic. A lot of the examples mentioned here are probably well known to West Germans, too, and quite a few of them actually made it into the gesamtdeutsche (‘all-German’) lexicon. For instance, the terms Ossi and Wessi, short for East German and West German, never actually left the vocabulary. Today, they are mostly used as a form of insult by each side, though.

In the media and everyday conversations, Germans still often speak about Ostdeutschland (‘East Germany’) and Westdeutschland (‘West Germany’) when discussing any economic or social differences that might still exist between the two parts of the country. However, attempts have been made to replace them with the more neutral designations neue (Bundes-) Länder (‘new states’, for East German states) and alte (Bundes-) Länder (‘old states’, for West German states). One of the reasons for this is that geographically, states like Thüringen and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern are not actually located in the East, but in central and northern Germany respectively. Moreover, the names appear anachronistic when used not in a historical context, but to point to the current political situation in Germany, as they contain a reference to a division that ceased to exist 25 years ago.

A version of this blog post originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “Remains of the Berlin Wall” by John deSousa. Public Domain via Flickr.

The post Do East and West Germans still speak a different language? appeared first on OUPblog.

Perceiving dignity for World Mental Health Day

Each year in July, I greet a new group of post-doctoral psychiatric trainees (‘residents,’ ‘registrars’) for a year’s work in our psychiatric outpatient clinic. One of the rewards of being a psychiatric educator is witnessing the professional growth of young clinicians as they mature into seasoned, competent, and humanistic psychiatrists. Over the course of my year, and in our residents’ stage of training, the most dramatic change is not in developing their skills as clinical interviewers, nor in expanding their knowledge of psychopharmacology, or refining their insights as psychotherapists, but in transforming their very perceptions of patients.

When they begin in July, their major concern is to learn about their patients, from the medical record as well as from the patient themselves. They inherit a panel of patients from their predecessors, and over the course of the year, evaluate and work with new intake patients. In the late summer months and into the fall, they consider the evidence base of the patients’ treatments, they are concerned if this or that patient is ‘really’ bipolar, and they try to grasp and understand the patient’s psychopathology. They wrangle with patients’ polypharmacy, wean them off of their chronic benzodiazepines, check for drug interactions, and get them social service assistance for everything from dentures to fallen roof repairs.

Instead of a case they see a multidimensional human being, imbued with dignity, noble in the glory of their diversity.

By the Texas wintertime they have become familiar with their patients, and start to engage more with discussions of their patients’ lives rather than their symptoms and problem list. This is where the magic starts.

By springtime the residents typically anticipate, eagerly so, the visits of most, but not all of their patients. (Psychiatrists are human, after all!) By this time they have witnessed a few awakenings and flourishings of their patients, and shared the joy of these improvements. However, what they have witnessed even more frequently is the resolve, resilience, and courage of most of their patients in struggling with their biomedical, interpersonal, and social ordeals. Like reading a fiction page-turner, the residents can’t wait to know what has happened next in their patients’ unfolding stories.

But something else happens during these late spring to summer months. Their perception of the patients themselves transform. Instead of a case they see a multidimensional human being, imbued with dignity, noble in the glory of their diversity. A few of the residents become aware of the transformation of their own perceptions, and often express a sense of the privilege they have in engaging with people’s lives in such an intimate way.

This change in perception of patients is even more profound as they finish up their year. The American internist George L. Engel, the originator of the ‘biopsychosocial model’ of medical practice, was fond of telling a story about his own transformation through medical education. Before his medical training, he would encounter a homeless man on the street and hear a dry, hacking cough. By the end of his training the tubercular nature of the cough would announce itself to him. Thus his perception changed from a simple cough to the immediate perception of disease. Like Engel, our residents’ perception of patients transform through learning and experience. However, in our year the residents’ perception transforms from patients-as-cases to patients with human dignity restored. This restoration of dignity is independent of the patients’ restoration of physical or mental health; the change is in the doctor, not the patient.

Unfortunately, as we recognize World Mental Health Day on 10 October 2015, we should appreciate that too often the ideal of full dignity for all is not met everywhere, including in our own mental health neighborhoods and communities. Thanks to a robust and invigorated group of mental health service users around the world, social and political structures are being created in many countries that not only recognize the dignity of all, but imbricate this dignity by embracing our patients and service users as full partners – ‘co-producers’ – in not only how services are designed and treatments are provided, but also how service users are described and understood. Mental health services around the world, using practice models such as “values-based practice” are rethinking not just treatment of the mentally ill, but the terms of engagement, the design of services, and the negotiation of clinical relationships. The restoration of dignity may begin with the development of mental health services, but is not realized until all voices in the community are engaged fully, and dignity is a matter of perception, not construction.

Featured image: “Sunflowers” by Bruce Fritz. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Perceiving dignity for World Mental Health Day appeared first on OUPblog.

Biology Week: a reading list

Biology Week is an annual celebration of the biosciences in the UK organised by the Royal Society of Biology. By engaging the public through fun and interesting activities, Biology Week aims to promote the life sciences and their importance in our understanding of the planet we inhabit. In honour of this, we have compiled a reading list of biology titles that have helped further the cause through education and research.

Biology Week 2015 will run from Saturday 10th – Sunday 18th October. Join us in the discussion in the comment section below or by using the Twitter hashtag #BiologyWeek. Take a look at OUP involvement in Biology Week here.

The Animal Kingdom: A Very Short Introduction, by Peter Holland

by Peter Holland

Part of the Very Short Introduction series, this book takes the reader on a journey through the complex system of the animal kingdom, presenting definitions of key terms within their zoological contexts, as well as expounding on new views of evolutionary science.

Read Chapter 1.

Wildlife Conservation on Farmland: Two volume set, edited by David W. Macdonald and Ruth E. Feber

Since the establishment of an agricultural society, farming and wildlife have constantly interacted. This two-volume set examines the effects on the biosphere using real-life examples. Volume 1 provides practical considerations for nature conservation on lowland farms, while Volume 2 explores conflict between wildlife and agriculture through Wildlife Conservation Research Unit case-studies, suggesting possible solutions and policies.

Human-Wildlife Conflict: Complexity in the Marine Environment,  edited by Megan Draheim, Francine Madden, Julie-Beth McCarthy, and Chris Parsons

edited by Megan Draheim, Francine Madden, Julie-Beth McCarthy, and Chris Parsons

Looking specifically at the marine biological world, this volume explores the increasing attention paid to the human-wildlife conflict (where wildlife impacts humans negatively and vice versa) and its effects on conservation. By examining an array of case studies relating to the subject, the text provides a valuable reference for graduate students and researchers in the field of marine conservation biology.

Principles of Development: Fifth Edition, by Lewis Wolpert, Cheryll Tickle, and Alfonso Martinez Arias

The authors of this volume tackle the complexities of developmental biology to present a textbook that clearly explains the science to undergraduate and postgraduate students. Looking at how cells behave in all kinds of animals, custom-drawn artwork allows for a visualisation of the processes. Animations of key developmental processes have been made available online for this new edition, alongside problem-solving examples.

Organism and Environment: Ecological Development, Niche Construction,

and Adaptation, by Sonia E. Sultan

Graduate students taking courses in ecology, evolution, and developmental biology will find Sonia E. Sultan’s book an invaluable resource for recent research into ecological development as experienced in various natural systems. As biologists try to understand how organisms evolve in rapidly changing environments, Sultan here presents a framework in which these investigations can take place.

Genetic Analysis: Genes, Genomes, and Networks in Eukaryotes: Second Edition, by Philip Meneely

Starting with a survey of the all the key terms and concepts utilised in the study of genes, Meneely presents an up-to-date guide on how molecular genetics can be used to improve our understanding of biological systems. This second edition incorporates the significant advances made in recent research, including on human genetic diversity, exome sequencing, and complex traits. The updated Online Resource Centre is of great additional value to the undergraduate and graduate students at whom this book is targeted.

Molecular Biology of RNA: Second Edition,  by David Elliott and Michael Ladomery

by David Elliott and Michael Ladomery

This text provides a methodical introduction to the constantly developing field of genetics and RNA biology. It has been hypothesised that this molecule – rather than DNA – is the essential ingredient in the origination of life. The updated textbook, with new introductory material and expanded chapters, is therefore a timely addition to the resources currently available to students.

Introduction to Protein Science: Architecture, Function, and Genomics: Third Edition, by Arthur Lesk

Updated with recent research and developments, Introduction to Protein Science is a comprehensive primer for the field. Covering topics such as the structure and function of proteins, the methods and experiments used to study them, and practical applications for our knowledge in biotechnology and medicine, this textbook is essential for students of bioscience and biochemistry. Web-based exercises make this an all-inclusive textbook.

Testosterone: Sex, Power, and the Will to Win, by Joe Herbert

by Joe Herbert

Testosterone is widely known for being the hormone that activates masculinity in a mammal, changing both body and brain to make a male. Much research has been done in recent years to understand how and why this happens. Herbert’s volume discusses the nature of this hormone and how its existence has and will shape mammalian interactions and societies.

Conservation Education and Outreach Techniques: Second Edition, by Susan K. Jacobson, Mallory McDuff, and Martha Monroe

With a focus on techniques, this book provides guidance on planning and implementing programmes for conservation education and outreach. Readers are given the tools to generate original plans and evaluate the effectiveness of their efforts, in order to spread knowledge about the importance of conservation efforts around the world. This second edition takes into consideration new case studies and new methods of outreach.

Nests, Eggs, and Incubation: New ideas about avian reproduction,

edited by D. Charles Deeming and S. James Reynolds

Ornithologists of all kinds will be excited by this book on avian reproduction, which covers every aspect of the process as observed and recorded by leading authorities in the field. The text incorporates four comprehensive aspects: the nest, the egg, incubation and the study of avian reproduction. This accessible volume is an up-to-date resource for anyone interested in avian biology.

A Dictionary of Biology: Seventh Edition, by Robert Hine

With contributions from leading scientists and Nobel Prize winners, this is the authoritative dictionary for all terms biological. The seventh edition has been updated to incorporate 250 new terms essential for use in research, teaching and learning.

Plants: A Very Short Introduction,  by Timothy Walker

by Timothy Walker

As the sustaining element of the biosphere, plants play an incomparably important role in the evolution of animal life and the Earth’s climate in general. Providing an overview of plant life and its evolution over time, this Very Short Introduction emphasizes the importance of conservation for utilitarian and aesthetic purposes.

Read Chapter 6, on ‘What have plants ever done for us?’

Featured image: Leaves by Beba. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Biology Week: a reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers