Oxford University Press's Blog, page 607

October 8, 2015

The science of rare planetary alignments

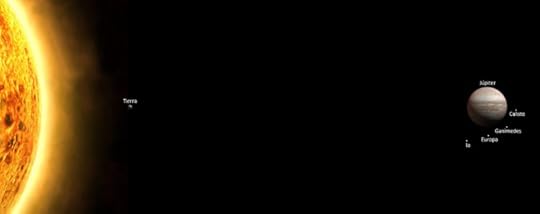

The alignment of both the Sun and the Earth with another planet in the Solar System is a rare event, which we are seldom able to observe in a lifetime. The Sun-Venus-Earth alignment for example only takes place once every 105.5 or 121.5 years. Similarly, the next Sun-Earth-Mars alignment will only occur in 2084. But on 5th January 2014, we were lucky enough to witness one such rare event: the alignment of the Sun, Earth, and Jupiter. Much to our surprise, we saw a new physical effect never observed before.

During these alignments, the planet farthest away from the centre of our Solar System sees the other planet crossing, or transiting, in front of the Sun. During the Sun-Earth-Jupiter transit for example, observers on Jupiter would see the Earth transiting in front of the Sun. No such transit would be visible from the Earth, however we have worked out an ingenious technique to “observe” these transits using the outer planet in the alignment as a reflecting mirror. Instead of directly observing the transit, we can observe the light being reflected by the outer planet as the transit takes place to study the effect the transit has on the light coming from the Sun.

Side view of the Sun-Earth-Jupiter alignment. Image by Paolo Molaro / NASA. Used with permission.

Side view of the Sun-Earth-Jupiter alignment. Image by Paolo Molaro / NASA. Used with permission.After having first applied this technique to the transit of Venus in 2012, during which light reflected by the Moon was used to study Venus, we used this method to observe the Earth during the Sun-Earth-Jupiter alignment. It was like following the passage of the Earth in front the Sun while comfortably sitting on Jupiter. Or more precisely, on one of its moons – Ganymede or Europa – since Jupiter itself, due to its high rotational speed and turbulent atmosphere, is by no means an ideal mirror.

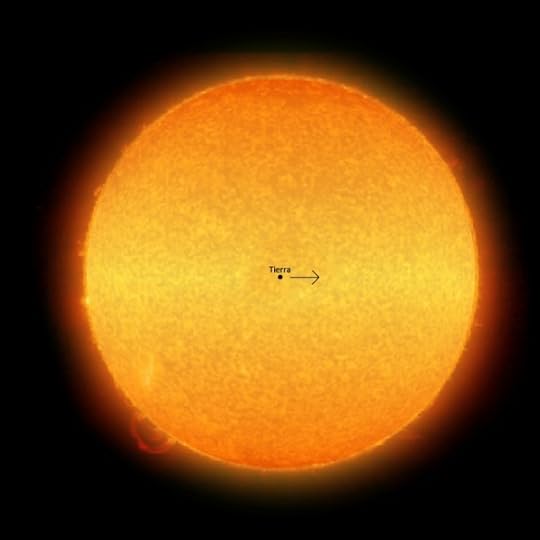

Earth shown as it would appear to an observer on Jupiter on 5th January 2014. Image by Paolo Molaro / NASA. Used with permission.

Earth shown as it would appear to an observer on Jupiter on 5th January 2014. Image by Paolo Molaro / NASA. Used with permission.The scientific aim of the observations was to study the Earth’s atmosphere as sunlight passed through it, and to measure the small drift in the positions of the spectral emission lines due to the occultation of part of the solar disc. Methods like these are also being used to study properties of the multitude of exoplanets currently being discovered (e.g. by NASA’s Kepler mission), in order to infer atmospheric composition and orbital parameters.

The event was followed from the Galileo telescope at La Palma, Canary Islands, and from the European Southern Observatory’s 3.6m telescope at La Silla in Chile. These were the only sites in the world able to observe the transit with the necessary high precision spectrographs. But instead of the expected decrease in the solar brightness due to the eclipse, we actually saw an increase. At the beginning we thought we had made a mistake during one of the observations, or that something in the instrumentation had not worked properly. We double-checked all the possible causes but found nothing unusual or wrong. Finally, after almost a year, we realised what had happened, and step by step we were able to interpret what had seen: a totally new physical effect never measured before.

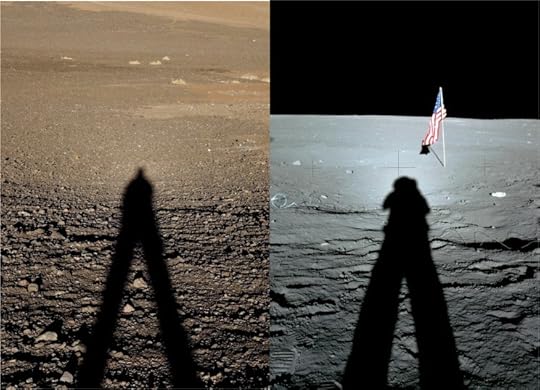

This is a peculiar effect that occurs because Jupiter’s moons Europa and Ganymede have no atmosphere – the light from the source, i.e. the Sun, comes from directly behind the observer on Earth. You may remember the light surrounding the head of the shadow of astronauts on the Moon.

On the left

, the shadow of Simone Zaggia, one of the co-authors, at the Paranal Observatory in the desert of Atacama. On the right, the shadow of the astronaut Charles “Pete” Conrad, commander of the Apollo 12 mission, on the Moon. The brightening around their heads show the opposition brightening effect (also called Opposition Surge). This effect acted during the Earth transit to enhance the light of the Sun around the Earth, producing a new effect which we called the Inverse Rossiter-McLaughlin effect. Image by Molaro / NASA. Used with permission.

On the left

, the shadow of Simone Zaggia, one of the co-authors, at the Paranal Observatory in the desert of Atacama. On the right, the shadow of the astronaut Charles “Pete” Conrad, commander of the Apollo 12 mission, on the Moon. The brightening around their heads show the opposition brightening effect (also called Opposition Surge). This effect acted during the Earth transit to enhance the light of the Sun around the Earth, producing a new effect which we called the Inverse Rossiter-McLaughlin effect. Image by Molaro / NASA. Used with permission.The observed increase in brightness occurs only when the alignment is perfect. As it moved through the disk of the Sun, the Earth’s atmosphere was acting as a lens and increasing the intensity of the light from the areas of the Sun around its projected image. The result on the spectral lines was to move them exactly the opposite of an eclipse, and by far stronger. Our model explains the observations in every small detail.

The next alignment between the Sun, Earth, and Jupiter will occur pretty soon in 2026. After that, we will have to wait until 2109. We really hope to have a second chance to follow this new transit and confirm our theories with the new Extremely Large Telescope under construction in the Atacama desert in Chile.

Featured image: The Solar System by Harman Smith and Laura Generosa, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The science of rare planetary alignments appeared first on OUPblog.

A mapping of musical modernity

What has history got to do with music? Music, surely, has to do with the present moment. We value it as a singularly powerful means of intensifying our sense of the present, not to learn about the past. If we listen to Mozart, it’s for pleasure, not for a snapshot of Viennese life in the 1780s. Nevertheless, that begs the question why we take pleasure in something from such a distant time and place. We don’t enjoy the plumbing systems of the 1780s, or surgical procedures of nineteenth-century medicine, nor do we wear the clothes our grandparents did. So why do we use music from all these times as part of our own present? Why is old music still so resonant?

One answer to that question is that, for all the differences of musical style across several centuries, the concerns of old music are remarkably similar to those of today. Such a view pushes against a normative understanding of history which sees historical time unfold like the line on a graph, moving irreversibly from left to right. Music history has certainly been told that way, as a narrative of development and progress which sees each generation take up and transform the achievements of previous ones. Of course, that produces a glaring and awkward contradiction – unless you want to argue that the latest music is always the best.

Which leaves you with a history of linear change without any corresponding logic of explanation. A more interesting view might be something that looks like a map of the London Underground or the New York subway. What happens to our understanding of music if we think of the broad period of modernity, from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, not as a journey along a one-way road, but as a space traversed in multiple directions? Such a mapping of musical modernity would suggest not only reading in different directions (backwards and laterally, as well as forwards) but also the intersecting of quite different lines – those of music with those of science, technology, politics, literature, philosophy. Since all these lines and all their possible connections are present simultaneously, Bach is as present as Boulez, and the exploration of tonal space is a short stop from the great voyages of discovery that shaped modernity from the sixteenth century onwards.

Music has often been a poor relation in the big accounts of western history and society and for several reasons: it doesn’t represent the world with the visual precision of painting or literature, is notoriously difficult to talk about, and is widely agreed to lack objectivity. But what happens if we take it seriously as a way of knowing the world, a kind of knowledge both embodied and highly cerebral at the same time, sensuous (and therefore particular, subjective, and personal) but also rational (and therefore general, objective, and shared)? It may be that we have seriously underestimated music’s role in our collective world-building.

Recent shifts in frameworks of knowledge from philosophy to neuroscience, evolutionary biology to acoustics and linguistics, lend themselves to such a view. Of course, music hardly competes with the kinds of knowledge that science affords. Its value lies elsewhere – in the unremarked and unattended ways in which it confirms, questions and re-makes our habitual ways of knowing the world. In which case, to think about the music of our past is to map a geography of sensibility – the frameworks in which we have represented our experience of the world and of ourselves. From that perspective, music suddenly seems pretty central to the story of modernity.

Aside from the words it sometimes carries, music rarely speaks about the world directly, nor does it record historical events like some acoustic chronicle. It offers no discursive account of the Reformation or the French Revolution, colonialism or capitalism, Descartes or Newton, industrialization or the rise of digital technologies, and yet it is highly articulate about the changes in sensibility of which such events are as much a product as a cause. The history of instrument making and tuning systems, for example, is a material form of the history of scientific rationalism, and the great musical forms of the past four centuries are no less ordered in their structure and grammar than forms of linguistic thought. Yet at the same time music is utterly counterfactual, the work of the imagination, imitating the world only to remake it in ways both playful and critical.

So, to reverse my opening question, what has music got to do with history? Rather more than we thought, perhaps, once we understand that music does not simply reflect modernity but plays an important part in its making. But of course, though it may be the object of historical scrutiny, music remains first and foremost a present experience, an aesthetic encounter here and now. From the sounding of the first note, no listener thinks of history, even though in every bar of music – from Monteverdi to Berio, and Beethoven to Saariaho – we participate in a network of thought and sensibility that runs through music like the DNA of our modernity.

Image credit: Music Company, Petworth. William Turner. Tate Gallery, London, UK. Public domain via WikiArt.

The post A mapping of musical modernity appeared first on OUPblog.

10 things you may not know about our Moon

Throughout history, the influence of the full Moon on humans and animals has featured in folklore and myths. Yet, it has become increasingly apparent that many organisms really are influenced indirectly, and in some cases directly, by the lunar cycle. Here are ten things you may not know about the way the Moon affects life on Earth.

Palolo worms, a gastronomic delicacy in seas around the Samoan Islands, emerge in vast numbers to be caught by local fishermen only during days of the third quarter on the Moon in October or November.

Common Green Crabs transferred from a rocky sea coast to a marine aquarium continue to “sleep” at intervals coinciding with times when the Moon-driven tide has ebbed on their home beach.

Sea Lice which live in beach sand near high water mark during spring tides avoid being left high and dry during neap tides by swimming up, fortnightly, into the falling tide, timed by their own internal biological clocks of Moon-related periodicity.

Wideawake Terns on Ascension Island in the equatorial Atlantic Ocean – where seasonal changes in day-length are small – return to the island to breed after every tenth lunar month, not every calendar year.

Image credit: Moon, by Bryan Jones. CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Moon, by Bryan Jones. CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0 via Flickr.African Scarab Beetles are able to roll to safety, for later consumption, balls of elephant dung, travelling in straight line directions determined by the position of the Moon.

Young stages of an insect, the Ant Lion, excavate funnel-shaped pits in sand into which fall other insects which are captured as food. The Ant Lion builds larger pits during Full Moon, when prey insects would be more wary, and does so even if it is prevented from seeing the Moon.

Sandhoppers foraging in sand dunes on Mediterranean beaches are able to navigate accurately to the strand-line at night using the position of the Moon, compensating for the changes in position of the Moon by use of their own internal lunar clockwork.

Beach-living Midges swarm to mate randomly if they are unable to see the Moon, but exposure to moonlight for three nights only induces fortnightly mating swarms, by setting in motion the midges’ internal Moon-related biological clocks.

Young Shore Crabs moult just after full and new Moon and continue to do so in aquaria when they are unable to see the Moon.

Human volunteers isolated from time cues in a sleep laboratory fall asleep more quickly during nights of the New Moon.

Featured image credit: Super moon, by Blondinrikard Fröberg. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post 10 things you may not know about our Moon appeared first on OUPblog.

October 7, 2015

Bare bodkins and sparsely clothed buttinskis, or, speaking daggers but using none

Few people would today have remembered the word bodkin if it had not occurred in the most famous of Hamlet’s monologues. Chaucer was the earliest author in whose works bodkin occurred. At its appearance, it had three syllables and a diphthong in the root, for it was spelled boidekin. The suffix –kin suggested to John Minsheu, our first English etymologist (1617), that he was dealing with a Dutch noun. He had good reason for his conjecture. For example, such English family names as Watkins (Watkin, that is, “little Wat” or “little Walter”) and Jenkins testify to their origin from the Low Countries (compare also lambkin, etc.). Stephen Skinner (1671) did not support Minsheu and etymologized bodkin as “little body” (a native English word). To be sure, a Dutch suffix doesn’t prove that the entire word is Dutch. In fulfillment (to give a random example), the suffix is French, but the root is English. Words of this type are many (see also the end of the present post). Therefore, Skinner’s suggestion (people cited it as late as 1898) was not absurd, except that the noun body never had the form boyde and that a bodkin is not a body at all. Ultimately, the Celtic hypothesis won the day. The attempt to explain bodkin as “biter” (its originator was Eduard Mueller) had no success, but a somewhat similar conjecture appeared in Skeat.

The form nearest to Chaucer’s is Scottish Gaelic biodag. The lending language cannot be ascertained, for it is not excluded that biodag was borrowed by Scots from Middle English. But even if biodag is native in Gaelic, its etymology in that language remains obscure. Therefore, since one opaque word cannot shed light on another word whose origin is also unknown, formulations in our dictionaries need refinement, and it is curious to observe the editors’ efforts to say something but, if possible, not too much. Noah Webster derived bodkin from Irish; his editor Mahn (1864) replaced Irish with Welsh. At that time, the fear of making a mistake had not yet taken hold of etymological lexicographers, but, when, in the twentieth century, Webster’s International came into being (there are three editions of it), people became very careful. In the first edition, we find “? Welsh”, in the second, “of uncertain origin”, and in the third only the Middle English form is given. Modern entries have become unassailable but uninspiring.

This is the weapon with which one can make one’s quietus in the quickest way possible.

This is the weapon with which one can make one’s quietus in the quickest way possible.The inspiration for part of what follows comes from a 1932 article by Paul Barbier, an excellent word historian. He cited Middle Engl. bidowe, which occurred only once in 1362 and which seems to mean “dagger.” This is the only example of this obscure noun in the OED. Barbier set out to show that a multitude of French words could be traced to the Basque root bide “road.” I will refrain from following him into the territory alien to me and only say that Middle Engl. bidowe, though an isolated word in Langland’s Pier Plowman, probably does mean “dagger” and that it bears a slight resemblance to Engl. bodkin, which Barbier did not mention. Be that as it may, one wonders whether bodkin could have reached English from Old French. Skeat suggested this route as a distant possibility. In the first edition of his dictionary, he derived bodkin straight from Celtic, but in the fourth he cited Anglo-French beitequin, from MDu beytelkin “a small beetle” and supported his guess by referring to Du. beitel “chisel.” This derivation reminds us of Mueller’s beater. The only scholar who to a certain extent trod the same way was Weekley. He thought of some word like Anglo-French boitequin “little box” (a word not recorded in texts): first a sheath for the weapon, then the weapon kept in it, as happened in the history of tweezers and a few other Romance words. Since boitequin was reconstructed only to explain the origin of bodkin, this etymology does not go too far.

The origin of bodkin would have been rather clear but for an alternation of vowels in the first syllable; we cannot decide whether the sought-for ancient form had a, o, i, oi, io, or something else. Consequently, no conclusion will be fully satisfactory. Neither o could “develop” into oi ~ io, nor oi ~ io could “become” o. A broad look at the linguistic map shows that bod-kin resembles not only some Celtic forms. This fact was brought into prominence by Hensleigh Wedgwood, who in his usual cavalier way strung together words from different languages and called this medley an etymology. However, we should not miss his mention of Slavic bodati “to butt” (Russian bodat’ “butt with the horns”) and French bouter “hunt, pursue,” alongside Gaelic biodag. I am surprised that he missed the Germanic family of Engl. beat and French battre “beat; batter.” It is curious to observe how often European b-d ~ b-t words denote striking, butting, and the like. Possibly from the idea of beating and striking Old English had beadu “battle,” which I discussed in connection with the English adjective bad. Beadu had an exact parallel in Old Icelandic böð (ð was pronounced as th in Engl. the). Male names tell the same story; in addition to Old Irish bodb ~ badb “raven” (a bird of battle) and “warrior maiden”, we find Celtic Boduos, Gothic Baduarius, and Icelandic Böðvar(r). In Slavic, nouns denoting “dagger; thorn, etc.” have been derived from bod– with the help of various suffixes.

The only genuine buttinskis

The only genuine buttinskisIt seems that a common European base b-d existed from which the names of daggers were formed. Bodkin may be independent of biodag and bidowe but related to them in the most general sense of the term “relationship.” The syllable kin need not even be a suffix; it may have come from some French word (perhaps but not certainly of Dutch origin). Compare mannequin, which traveled from Dutch to French and returned to English in its French guise as a doublet of manikin (from Dutch manneken “little man”). A borrowing (a migratory word) in practically every language, the name of a dagger would naturally have acquired dissimilar forms (with oi, i, o, and so forth). In the series on bad, I suggested that Engl. bad came into being as a baby word, a sound symbolic formation coined to frighten children. The b-d military terms whose existence I dared reconstruct here are related to bad (if at all) in the vaguest sense possible. In the world of symbolic and sound-imitating formations, affinity is an almost meaningless concept. Thus, Old Engl. beadu is not a derivative of bad. The reason for the attraction of the b-d group remains a moot point.

It remains for me to say that not long ago the phrase to ride bodkin existed in English. At bodkin the OED gives the sense “a person wedged in between two others where there is proper room for only two.” In Lincolnshire, bodkin was used for a team of three horses, yoked two abreast behind, and one in front. An unexpected definition of bodkin occurs in Hotten’s Slang Dictionary (1859): “Amongst sporting men, applied to a person who takes his turn between the sheets on alternate nights, when the hotel has twice as many visitors as it can comfortably lodge; as, for instance, during a race week.” Apparently, not every bodkin has to be completely bare.

Image credits: (1) Moose sparing. (c) RONSAN4D via iStock. (2) Post Medieval silver bodkin fragment. 2002T293, Abbots Barton, Hampshire. Photo by Portable Antiquities Scheme from London, England. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Bare bodkins and sparsely clothed buttinskis, or, speaking daggers but using none appeared first on OUPblog.

Compassion or compromise? The ethics of assisted suicide

“Death is inevitable, but suffering doesn’t have to be,” says Tennessee native John Jay Hooker, who has devoted his life to fighting for civil liberties, and his deadly cancer hasn’t stood in his way. This past summer, he filed a lawsuit against his state to sue for the right to die on his own terms.

If you found out that you were going to die from a progressive, painful and debilitating disease–say Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig disease) or cancer, would you want someone to tell you that you couldn’t end it all? Even when you could not face the pain and suffering anymore? As long as the decision was truly yours and made while you were mentally competent, before the progression of disease may have made this impossible, would you want some governmental entity telling you that you couldn’t?

Swift, dramatic progress in science has given us the ability to save lives and treat disease more effectively than ever before. However, this same technology has provided the power to prolong the lives of those whose physical and mental conditions are irreversible, and who experience intractable pain.

Just days ago lawmakers in California passed legislation to allow physician-assisted suicide (PAS), pending the signature of the governor. It is modeled after Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act, and would give mentally capable people with terminal illnesses the option of obtaining a physician’s prescription for drugs to end their lives painlessly and with dignity. States with comparable laws include Washington, Montana and Vermont.

Supporters of assisted suicide argue that all individuals have the right to choose what they will do with their lives, as long as they don’t harm others. For most people, the right to die is one they can easily employ. But for some, their disease or condition makes them unable to exercise this right in a dignified way. Physician-assisted suicide is often confused with euthanasia, in which the doctor provides the means of death, usually using a lethal drug. PAS is always administered by the patient, after he/she requests it and consents to it.

One who opposes measures to allow assisted suicide may argue that we as a society have a moral obligation to respect, protect and preserve life. To take it a step further, one might feel that society must oppose any threat to the lives of innocent people. If assisted suicide is permitted based on mercy and compassion, the argument goes, what will prevent us from extending this to anyone whose life may be considered worthless, undesirable, or inconvenient? Brittany Maynard, a 30 year old American woman with terminal brain cancer who decided that she would end her own life, recently became the face of the right-to-die movement. She and her husband moved from California to Oregon so that she could die with dignity, on her own terms. In her final Facebook post, Maynard wrote “Goodbye to all my dear friends and family that I love. Today is the day I have chosen to pass away with dignity in the face of my terminal illness, this terrible brain cancer that has taken so much from me … but would have taken so much more.”

Arthur Caplan, a medical ethicist from NYU, wrote that because Maynard was “young, vivacious, attractive … and a very different kind of person” from the average patient seeking assisted suicide, she “changed the optics of the debate” and inspired people in her generation to think about this issue.

Many health care professionals object to PAS because they feel that certain vulnerable populations may be negatively impacted. This assumes that once PAS is initiated for the terminally ill, it will be offered to or even forced upon other vulnerable groups, such as the disabled or the poor. Further concern surrounds the issue of whether these populations may be assisted to their deaths without actually consenting to them.

State legislators around the country tend to look at the Oregon Death with Dignity Act as a guide, because it has been in effect since 1997, and data since that time has shown that the law has been utilized the way it was intended. In other words, there has been no evidence of a slippery slope for individuals deemed vulnerable or “undesirable.” Similar results have been seen in Washington and Vermont, which have had this type of legislation since 2008 and 2013, respectively.

The conflict has waged over decades; in the 1990s, Dr. Jack Kevorkian assisted in the suicides of over 100 terminally ill patients, with much public protest, and for which he was imprisoned. In 2009, the debate was over a clause in the Affordable Care Act having to do with end-of-life discussions to help regulate health-care costs. Critics of PAS called these “death panels,” as it was felt that these consultations were for the purpose of coercing terminally ill patients to ask to die.

The case against physician-assisted suicide is powerful, as it addresses the fundamental reverence for life, our ability to respond to suffering with true compassion and the risk of slipping down the slope toward minimizing respect for life. But the counter-argument is equally powerful, as it appeals to our empathy and our wish to support individual self-determination; it is saying that allowing a patient to decide when he/she is ready to die and to do so on his/her own terms is the most compassionate thing that we as a society can do.

Featured Image: Courtroom gavel by Joe Gratz, Public Domain via Flickr.

The post Compassion or compromise? The ethics of assisted suicide appeared first on OUPblog.

Don’t panic: it’s October

At the conclusion of the mid-September meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the Federal Reserve announced its decision to leave its target interest rate unchanged through the end of this month. Although some pundits had predicted that the Fed might use the occasion of August’s decline in the unemployment rate (to 5.1 percent from 5.3 percent in July), to begin its long-awaited monetary policy tightening, those forecasts left out one crucial fact.

It’s October.

And although October is when Chinese, Germans, Greeks, Kazakhs, Nigerians, and Spaniards celebrate their national days, Canadians commemorate Thanksgiving, and Americans celebrate Columbus Day, for anyone with a sense of financial history, October is a month to be feared.

Because October is when financial crises erupt.

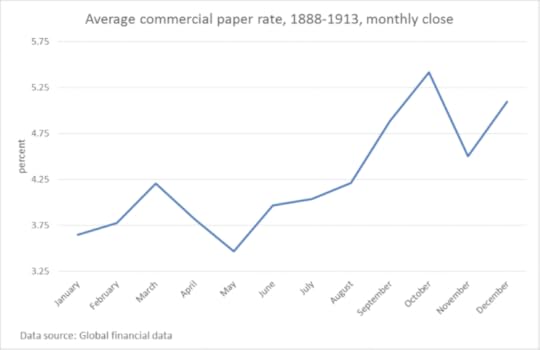

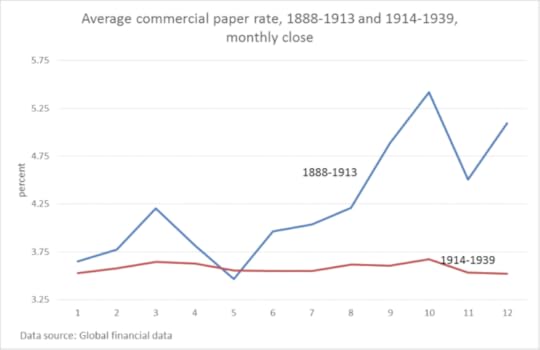

During the 19th and early 20th century, American and European financial crises typically took place in the autumn, mostly in October. It is not difficult to explain this seasonal pattern. In the northern hemisphere, crops are harvested in the fall and shipped from agricultural areas where they are produced to more urban areas where most are consumed. The money to pay for these shipments flows in the opposite direction. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, this outflow of funds from financial centers to more rural areas led to a sharp increase in interest rates during the autumn months. This financial strain often ended in financial crisis. Figure 1 shows this seasonal pattern during the quarter of a century before the Federal Reserve.

Figure 1, by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission.

Figure 1, by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission.Beginning with its establishment in 1914, the Federal Reserve began to smooth out this seasonality and, as can be seen in Figure 2, the autumnal increase in interest rates practically disappeared.

Image credit: Ted Cruz, official portrait, 113th Congress by the Office of Senator Ted Cruz. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Ted Cruz, official portrait, 113th Congress by the Office of Senator Ted Cruz. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Figure 2, by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission.

Figure 2, by Richard S. Grossman. Used with permission.Despite the decline in the seasonality of interest rates, U.S. financial crises have remained very much an autumn event. The most famous financial crisis of all, the 1929 stock market crash on the eve of the Great Depression erupted on 24 October. The 1987 U.S. stock market crash, failure of Lehman Brothers, and the European sovereign debt crisis all emerged in September or October.

There is no consensus view among economists as to why financial crises still cluster in the autumn. The post-1914 financial crises discussed above had a variety of different causes, many of which developed over months—if not years. There was no obvious common trigger for these events.

Let me suggest one: politics—or, more accurately—politicians.

Like swallows returning to Capistrano or salmon to their spawning grounds, politicians flock back to the capital after summer recess and start doing—or threatening to do–things that shake the market. Such governmental actions have been suggested as possible triggers for the 1987 stock market crash and the European sovereign debt crisis.

Could politicians trigger another October crisis? Yes.

A number of Congressional Republicans spent much of September threatening to shut down the U.S. government if Planned Parenthood was not de-funded. Senator Ted Cruz led the charge on this issue, but was joined by fellow GOP presidential contenders Ben Carson, Carly Fiorina, and Chris Christie. At the time of this writing (mid-September), it is not clear if a shut-down will take place, but the possibility is more than idle speculation. And if it occurs, the consequences will be severe.

FOMC members will have another opportunity to raise interest rates when they meet again at the end of October, but perhaps they will hold off until their December meeting. After all, if you are going to rock the boat, make sure you don’t do it in October.

Featured image credit: Stock exchange trading floor by skeeze. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Don’t panic: it’s October appeared first on OUPblog.

Charles Williams: Oxford’s lost poetry professor

It was strikingly appropriate that Sir Geoffrey Hill should have focused his final lecture as Oxford Professor of Poetry on a quotation from Charles Williams. Not only was the lecture, in May 2015, delivered almost exactly seventy years after Williams’s death; but Williams himself had once hoped to become Professor of Poetry. And with supporters of the calibre of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, W.H. Auden and T.S. Eliot – admittedly not all of them Oxford M.A.s – Williams might well have succeeded, but for his sudden death, aged 58, in the final weeks of World War Two.

Charles Williams had come to Oxford with other staff from OUP’s London office when war broke out in September 1939. OUP then had its London headquarters (specialising in textbooks and mass market books) at Amen House near St Paul’s cathedral – too vulnerable to bombing. So when war began, the London business was moved to Southfield House, a mansion on the north-east edge of Oxford.

Williams was a central figure at the Press, running the World’s Classics and the Oxford Standard Authors, both highly successful series. But he was also a notable popular novelist, with a string of fantasy-thrillers to his credit – Buchan-style adventure tales which dealt with eruptions of the supernatural into ordinary life. Their themes now seem oddly prophetic: War in Heaven concerned the theft of the Holy Grail by a gang of black magicians; Many Dimensions was about the Philosophers’ Stone.

Charles Williams. Fair use under copyright law, via Wikimedia Commons.

Charles Williams. Fair use under copyright law, via Wikimedia Commons.But Williams was also an experienced and entrancing lecturer on literature. Forged in the tough environment of London County Council evening classes, his lecturing skills included an encyclopaedic knowledge of poetry (he would quote tracts of Milton, Tennyson or Shakespeare from memory at the drop of a hat), fervent and engaging enthusiasm, and a strikingly odd accent (North London mixed with Hertfordshire, with quirks all his own) which you either loved or hated. Most listeners – used to lectures delivered in a languid ‘upper class’ accent – were shocked and then fascinated by his harsh tones.

Moving to Oxford in 1939, Williams already knew Lewis and Tolkien. In fact he had edited Lewis’s scholarly masterpiece The Allegory of Love for OUP. (It was Williams who devised the book’s snappy title; Lewis’s own title had been The House of Busirane: An Essay on the Erotic Allegory of the Middle Ages – which would have killed the book!) Lewis and Tolikien were both avid readers of Williams’s fantasy thrillers, and they immediately invited him to join the Inklings. He remained a central member of the Oxford Christian writers’ group throughout the war.

Wartime Oxford was short of lecturers, and Lewis immediately set about pulling strings to get Williams to lecture for the English Faculty. He began in February 1940, speaking on Milton, and the results exceeded all expectations.

Fifty years later, former students still remembered his performances vividly – ‘Mounting the steps at a bound and launching straight into a flood of quotation’; ‘telling students “Never mind what Mr. so-and-so says about it, read the text and think for yourself!”’; ‘declaiming like an Old Testament prophet or an enthusiastic evangelical preacher’; ‘Leaping from one side of the stage to the other, and acting in turn the part of each character he was talking about’; ‘clutch[ing] his copy of Wordsworth, once almost throwing it into the air, but luckily catching it again… totally absorbed in his fascination with the subject’; ‘Pacing up and down the platform… return[ing] to its centre table three times to bang on it three times with his fist to impress on his audience that “Eternity — forbids thee – to forget”’. In short, ‘Electrifying!’ Some of those students went on to become teachers of English and throughout their careers returned to their notes on those lectures for inspiration.

Lewis was so impressed with Williams’s lecture on the theme of chastity in Milton’s Comus that he declared, ‘That beautiful carved room had probably not witnessed anything so important since some of the great medieval or Renaissance lectures. I have at last, if only for once, seen a university doing what it was founded to do: teaching Wisdom.’

But Williams was also a notable poet. In 1930 he had edited the first mass-market edition of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and it had galvanised his own writing. In 1936 he had published Taliessin Through Logres, the first of a two-volume sequence on the Arthurian legends.

The poems, together with his powerfully inspiring lectures, had brought him admiration not only from his contemporaries (Auden in New York writing to say that he couldn’t wait to buy Taliessin, though ‘it would take courage’ because he didn’t know how to pronounce it!) but from aspiring undergraduate poets, many of whom were taking short courses whilst awaiting mobilisation. Drummond Allison, Sidney Keyes and John Heath-Stubbs, all at Queen’s College, read his work avidly, attended his readings at the Celtic Society and the Poetry Society, and wrote on Arthurian themes in emulation of his work. Both Allison and Keyes, after an early poetic flowering, would die, tragically, in the war; Heath-Stubbs remained a lifelong enthusiast for Williams’s poetry.

And on days when he wasn’t enjoying a lunchtime drink with the Inklings at the Eagle and Child, Charles Williams could often be found in the King’s Arms with Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin. Less enthusiastic about his poems, both keenly attended his lectures and it was to Williams that Larkin sent the manuscript of his first novel, Jill, hoping that Williams could gain the attention of Eliot at Faber and Faber.

With retirement approaching, Williams began to consider the future; there were murmurs that the Chair of Poetry would suit him ideally; he could continue at the Press whilst lecturing, and perhaps take a college Fellowship afterwards. Not only were the Inklings keen; scholars of the calibre of Helen Gardner and Maurice Bowra were likely to back him.

Then, on 15 May 1945, it all fell apart. An old abdominal complaint suddenly recurred; Williams was rushed into hospital, and died after an emergency operation. In the turmoil of the war’s last weeks, his death passed largely unnoticed by the outside world. But literary Oxford was bereft. Hearing the news, C.S. Lewis’s brother Warnie wrote, ‘The Inklings can never be the same again.’ Another undergraduate poet and future Professor of Poetry, John Wain, heard from a fellow-student (‘she was only just not crying’) as he walked into college. Wain sensed that it was the end of an era: ‘This was a general disaster, like an air-raid… The war with Germany was over. Charles Williams was dead. And suddenly Oxford was a different place.’

Featured image credit: ‘Oxford’, by Mario Sánchez Prada. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Charles Williams: Oxford’s lost poetry professor appeared first on OUPblog.

October 6, 2015

Little progress in how to advise women with dense breasts

Lawmakers around the country are rushing to enact laws that require providers to notify women if their screening mammograms find dense breast tissue. Meanwhile, clinicians remain at a loss concerning how to counsel such women.

As of early August 2015, nearly half the states have laws requiring health professionals to report mammographic breast density to patients. Some also require that the report include information on supplemental screening tests. But although ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect cancers that mammography missed, many questions remain unanswered, including the effect on morbidity and mortality, cost-effectiveness, and insurance coverage.

The problem is widespread, since up to half of all women reporting for screening mammograms have breasts classified as extremely or heterogeneously dense. The problem is especially common for women in their 40s. Dense breasts (those with a high proportion of fibroglandular, as opposed to fatty, tissue) can hide small cancers. Mammographic density is also an independent risk factor for breast cancer, especially advanced cancer.

For 40 years, researchers have worked to understand and refine that risk, but progress has been slow. In May, Karla Kerlikowske, M.D., of the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of California–San Francisco, and colleagues reported the results of a prospective cohort study. They found that not all women with dense breasts are at increased risk—only those with additional risk factors.

Kerlikowske’s group looked at interval cancers—breast cancers diagnosed within a year of a normal mammogram. Interval cancers can be especially aggressive, so adjunct screening tests would probably be most beneficial in women at high risk for such cancers.

The team analyzed more than 800,000 digital screening mammograms from 365,426 women. They calculated each woman’s 5-year risk of developing breast cancer by using the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium risk model. That tool factors in age, first-degree relatives with breast cancer, biopsy history, race or ethnicity, and density on BI-RADS (the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System).

The researchers defined a high rate of interval cancers as more than one case per 1,000 mammograms. Women with extremely dense breasts had high rates if they also had a 5-year breast cancer risk of 1.67% or greater, as did women with heterogeneously dense breasts with a 5-year risk of 2.5% or higher. That added up to 24% of those with dense breasts.

State notification laws “say you should inform women if they have dense breasts and advise them about supplemental imaging,” Kerlikowske said. “But you can’t perform supplemental screening on all women with dense breasts—which is 27 million in the U.S. You should target those discussions to the 24% who are really at high risk.”

Kerlikowske pointed out that the women in her high-risk group were at risk not only of missed cancers but also of advanced cancers. “If you’re going to do supplemental screening,” she said, “that would be the group.”

The Kerlikowske study offers “compelling evidence that breast density should not be the sole criterion to guide decisions about supplemental breast cancer screening,” wrote Nancy Dolan, M.D., and Mita Sanghavi Goel, M.D., both of Northwestern University in Chicago, in an accompanying editorial.

More than 43% of women aged 40–74 years have dense breast tissue, according to a study published last year. Other studies put the proportion of women with dense breasts closer to 50%. And that number could rise with the implementation of a new BI-RADS system. Instead of assessing the percent area of a mammogram that contains dense tissue, the new system classifies any breast with a particularly opaque area as a dense breast, and the classification applies to the denser breast.

Edward Sickles, M.D., professor emeritus and former chief of breast imaging at UCSF, said this reflects that the more serious problem of mammographic density is its ability to mask cancers, rather than its effect on breast cancer risk.

“Although breast cancer risk is slightly higher in women with dense breasts,” Sickles said, “the increased risk has been exaggerated in some publications, which compared those with the densest breasts to those with the fattiest breasts. If you compare a woman with heterogeneously dense breasts to the average woman, her risk is only 1.2 times higher—a rather low level of risk that doesn’t support supplemental screening.” Even women with extremely dense breasts are only 2.1 times more likely than women with average density to develop breast cancer—a risk equivalent to having a first-degree relative with the disease.

Grassroots advocates have persuaded lawmakers in 24 states so far—including New York, Texas, and California—to mandate that providers notify women whose breasts were found to be dense on mammography. Some laws add that women should be urged to discuss supplemental screening tests with their doctors. Similar federal legislation is also pending. However, experts have expressed concern that such notice can create anxiety in patients—and confusion among physicians—because it’s unclear how women with dense breasts can reduce their risk.

“There’s a lot of variability in what’s being reported back to women,” said Rulla Tamimi, Sc.D., a researcher at Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston. “Those laws happened before we were ready. We don’t have clear guidelines or recommendations for these women or their physicians. There’s still so much we don’t know.”

The Texas and Louisiana statutes, for example, require mammographers to give the following notice to patients: “If your mammogram demonstrates that you have dense breast tissue, which could hide abnormalities, and you have other risk factors for breast cancer that have been identified, you might benefit from supplemental screening tests that may be suggested by your ordering physician.” Connecticut, the first state to pass a density notification statue, requires physicians to offer supplemental ultrasonography, MRI, or both to all women with dense breasts. Unlike most states, Connecticut also requires insurance to cover the additional screening.

Radiology studies have shown that supplemental imaging with ultrasound can detect some cancers that mammography misses in women with dense breasts. However, Brian Sprague, Ph.D., of the University of Vermont Cancer Center in Burlington, and colleagues recently concluded a comparative modeling study. They found that supplemental ultrasonography for these women has little effect on outcome but dramatically increases costs and harms, including a high rate of false positives. (The study, published in January in Annals of Internal Medicine, examined all women with dense breasts without trying to stratify them by risk.) Sprague’s team had looked at ultrasonography because it’s widely available in the clinic and relatively inexpensive. Potential alternatives include fast MRI and digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), or 3-D mammography. A computer simulation published in March found that adding tomosynthesis to biennial mammography would avert 0.5 deaths and 405 false-positive results per 1,000 women. The additional cost per quality-adjusted life-year saved was $53,893 with tomosynthesis, compared with $325,000 with ultrasonography in the Sprague study.

But “DBT is not going to be a supplement for 2-D mammography,” said Daniel Kopans, M.D., the Harvard radiology professor who invented DBT. “It will completely replace 2-D mammography, just as digital mammography has replaced screen-film mammography. . . . DBT is actually a much better mammogram, since it finds many more early cancers while having fewer recalls.”

A version of this blog post first appeared in Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Image credit: “Metastatic Breast Cancer in Pleural Fluid” by Ed Uthman. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Little progress in how to advise women with dense breasts appeared first on OUPblog.

For the love of reason

Throughout much of the last century, the idea that we inhabit a somehow disenchanted modernity has exerted a powerful hold in political and public debate. As the political theorist Jane Bennett argues, the story is that there was once a time when God acted in human affairs and when social life, characterized by face-to-face relations, was richer; but this world then ‘gave way to forces of scientific and instrumental rationality, secularism, individualism, and the bureaucratic state – all of which, combined, disenchant the world.’ In this story, reason and religion are oppositional forces, the one succeeding the other. If the path to rationality is interpreted as the process of becoming possessed of and determined by one’s own mind, then this is surely fundamentally at odds with the religious desire for obedience to a revelatory divine voice.

To some extent, the return of religion to public and political forums of discussion has challenged this narrative. It has been problematized, too, by scholars of religion who have shown that the social worlds we inhabit can be religious, avowedly nonreligious and secular at the same time, and in myriad configurations. And scholars engaging with contemporary forms of the sacred show that it is not only religion that enchants, but that secular phenomena – commodities, the free market, the nation state, and others – may also take on a sacred significance.

Nevertheless, the idea that, as philosopher Gillian Rose puts it, Enlightened rationality is the ‘autonomous adversary of “revealed religion”’ persists. There are several reasons for this, but significant of these is precisely the non-rational attachments that some cultures have to the idea of themselves as rational. In fact, the study of both nonreligious and religious groups shows how reason and rationality are not so much culprits in some process of disenchantment but become themselves objects of enchantment.

Through New Atheist discourses, a particular mode of rationalist nonreligious culture has become familiar with, and echoing this, for many non-believers, rationality is central in both their self-understandings and in their understanding of an irrational religious other. Whereas for some nonreligious people, religious others are different in other ways, sometimes negative, but sometimes positive too, rationalist nonreligious cultures conceive of ‘believers’ as ‘stupid’, even ‘insane’ or experiencing a sort of deferment of the intellectual, brought about by suffering and a need for the existential comforts of religion – a Marxist spin on this rationalism that is often kindly meant, but carries with it condescending connotations of mental incapacity.

Image credit: Love romantic candlelight. CC0 via Pexels.

Image credit: Love romantic candlelight. CC0 via Pexels.Somewhat paradoxically, however, we might see these rationalist narratives as themselves becoming enchanted. Rational and scientific knowledge are transcendent: ‘The truth,’ Richard Dawkins’ said on Twitter this week, referring to his new memoir, ‘was true long before humans arrived. And will be after we are extinct. Out out, Brief Candle. Science is the Candle in the Dark.’ Conceived of as knowledge – as truth – the nature of the universe that science and reason reveal is beautiful, a comfort – a candle in the dark – and transcends human life. And for many people, the achievements of human rationality and science are an enormous source of comfort, hope, and inspiration. It therefore does not follow that vulnerability explains why people turn to religion, for they will find the same emotional, symbolic and social comforts that they might find in religion in nonreligious cultures, too.

On the other side of the coin, for all the religious cultures that embrace experience, emotion, community and romance, there are those for whom rationality and reason are instead central. If nonreligious culture emanating from the U.S. and the U.K. bears the mark of Protestantism in its understanding of religion as primarily a matter of cognitive belief rather than embodied practice, then it should not be surprising that rationalism is often present too in religious contexts.

So, for example, the British conservative evangelicals that Anna studied placed a similar emphasis on reason, and the individuals she worked with articulated a sense that their faith was rational and primarily about belief. For this group, the privileging of rationality is in fact a prominent marker of their culture, and is interwoven with the traditions of the gender and class characteristics of the movement: key twentieth-century leaders of British conservative evangelicalism have been upper middle-class and public-schooled men – something that also resonates with rationalist nonreligious cultures, whose figureheads have likewise tended to be upper middle-class white men of similar Protestant cultural heritage.

The rationalism of conservative evangelicals is instructive for thinking beyond the ‘irrational religion / rational nonreligion’ binary in other ways too. So, though the Enlightenment emphasis on rationality is often seen as a turn to the self, yet, for this and some other religious traditions, reason is seen as expressive of a divine order, and the sacred is understood as knowledge about God’s purpose and intentions. Thus, rationalism may involve a turn away from the self and towards other authorities. By this light, we may observe that nonreligious rationalism also orients the individual away from the self, via an attraction towards a coherent order that transcends the individual’s experience of and place in the world.

For both groups, then, reason can be experienced as a source of wonder. Despite the emphasis that some may place on religion in terms of cognitive belief, the ways in which people form these orientations towards reason is an embodied, emotional and social process. As anthropologist Charles Hirschkind describes, ‘reason has a feel to it, a tone and a volume, a social and structural architecture of reception, and particular modes of response.’

Rationalist sensibilities are often bound up with the othering of particular religious and nonreligious groups, and this is not the unique preserve of nonreligious people who may ‘other’ the ‘irrational religious.’ Anna’s conservative evangelicals also expressed a sense of their distinctiveness from charismatic evangelical Christians, whom they saw as placing more emphasis on emotion over reason. These conservative evangelicals also saw themselves as distinctive from a wider culture which they described as having turned away from reason. In one of the sermons that she observed, the minister said that we now live ‘in a world of soundbite and spin, where politicians appear to be elected at least in part on looks and media appeal, newscasters are employed on the basis of their ability to look good in front of the camera, and where celebrity culture has taken over from an age of carefully reasoned, sustained logic in our public discourse.’

Though the idea that the roots of Enlightenment rationalism can be found in Protestant modernity is a familiar one, it has not managed to unseat the idea that religion reaches emotional and symbolic aspects of life that the secular simply cannot and, by the same token, that the nonreligious and the secular have some kind of privileged access to rationality and reason. The dualisms here reflect the Janus-face of Western modernity and the conceptions of self, knowledge and experience that it promotes – a Kantian, disciplined, rational self, and a sensualist, expressive, affective self. Yet, close study of the place of rationality within religious and nonreligious cultures points to how reason may itself become a source of enchantment – formed through particular emotional and embodied practices, in which forms of power and exclusion inhere – for both the religious and the nonreligious.

The post For the love of reason appeared first on OUPblog.

Cuban cultural capital and the renewal of US-Cuba relations

This year, 2015, has been quite a year for Cuba. Starting in January with President Obama’s announcement that the United States and Cuba will re-establish diplomatic and economic relations, followed by Pope Francis’s visit to the island earlier this month, Cuba has been under the global spotlight. Most recently, 21 September marked a new economic era for Cuba with the implementation of new rules that will ease restrictions on American business dealings with the island, a move that many believe will have a mutually positive impact on travel, banking, telecommunications and Internet-based services, and other business ventures. It goes without saying that Cuba faces a future filled with unprecedented possibility.

Thanks to the “informational materials” exemption by the Office of Foreign Assets Control, which allows for the movement of music and other objects of artistic and intellectual expression between Cuba and the United States, Sony Music announced on 15 September that after two years of negotiations, it has signed an international licensing deal to distribute the catalog of Cuba’s state-owned record label Empresa de Grabaciones y Ediciones Musicales (EGREM). Established in 1964 as part of the state’s efforts to nationalize the Cuban music industry, EGREM’s monopoly on music production for most of the twentieth century has enabled it to amass one of the largest collections of Cuban music in the world. Although EGREM has licensed portions of its catalog to independent record labels in the past, this is the first time a multinational corporation has been given access to a majority of its catalog, allowing SONY to distribute over 30,000 audio and video recordings on a global scale. With a catalog that includes artists such as Celina González and Ibrahim Ferrer (of Buena Vista Social Club fame) and groups such as Los Van Van and Irakere, this new agreement will not only enable Cuban musicians to promote their music internationally, but also invite other companies in the United States and abroad to invest in Cuba’s various culture industries.

While Cuba’s post-revolutionary history is marked by isolation and restriction, the island’s cultural imprint has continually been felt throughout the world. Musical manifestations of pre-revolutionary Cuba include the international rumba craze of the 1930s and the subsequent emergence of genres such as Afro-Cuban (or Latin) jazz, the bolero, and mambo. While salsa’s origins lie in New York City and the genre is largely associated with Puerto Rican and Nuyorican musicians and culture, debates still persist as to whether or not salsa is really just “recycled Cuban dance music” (an extension of Cuba’s early twentieth century musical legacy). A cyclical phenomenon that can best be described as transatlantic feedback – in which musical idioms emanating from Africa undergo cultural appropriation in the New World, only to result in the rise of musical by-products that are then absorbed in further processes of musical hybridization by its place of origin – have informed the rise of largely Cuban-influenced genres such as soukous in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Cuba has continued to influence popular music production around the world amid the decade’s long US embargo. From the rise of genres such as cha cha cha in the 1960s, nueva trova and songo in the 1970s, and timba in the 1990s, to the establishment of festivals and conferences such as Cubadisco that set out to foster international relationships with Cuba through cultural exchange, Cuban popular music has thrived and circulated beyond the nation’s borders. Popular artists such as Celia Cruz and Gloria and Emilio Estefan along with other prominent Cuban-American industry leaders have played a pivotal role in the development of Miami as the Hollywood of Latin America. Moreover, the 1993 US Supreme Court decision to legalize santería animal sacrifices and the 1999 release of the critically acclaimed documentary, Buena Vista Social Club, has facilitated growing domestic and international interest in Cuban sacred, folkloric, and popular culture.

So how will this new deal with Sony contribute to Cuba’s dynamic cultural history and how will it affect the island’s economic and political future? How will the growing embrace of Cuban culture in the United States impact its Latino and Latin American immigrant populations, the nation’s largest minority group since 2000? Sony’s current deal pertains to EGREM’s back catalog, so will future profits determine second phase efforts to sign and represent emerging Cuban recording artists? Only time will begin to address these questions. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that the timeliness of Sony Music’s new partnership with EGREM, just six days prior to the US implementation of new regulations that aim to strengthen its relationship with Cuba, will springboard the island’s global impact both culturally and economically.

image credit: Cuba. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Cuban cultural capital and the renewal of US-Cuba relations appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers