Oxford University Press's Blog, page 599

October 25, 2015

Media policy and political polarization

Does media policy impact the rising political polarization in the United States? The US Congress passed The Telecommunications Act of 1996 that comprehensively overhauled US media policy for the first time since 1934, resulting in relaxed ownership regulations intended to spur competition between cable and telephone telecommunications systems. This deregulation allowed for more television channels on cable TV systems, including the inception of partisan news outlets like Fox News and MSNBC.

In today’s media environment, people have a wealth of information at their disposal. The increase in the number of television channels means people can select any number of programs to watch, particularly what political content they want to consume. A number of studies have shown that partisan news outlets draw distinct audiences, with conservatives consuming Fox News and liberals consuming MSNBC. The availability of this content is important because research has shown that watching content on these outlets contributes to political polarization. Furthermore, increased niche programming allows non-partisans who are not interested in politics to tune out altogether.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 created favorable conditions for a dramatic expansion in the number of media channels available to viewers, resulting in a rise in partisan television news channels among others. In turn, partisan television channels have been proven to contribute to political polarization. Does this then mean that the Telecommunications Act of 1996 inadvertently led to increased political polarization? In our recent article, published in the International Journal of Public Opinion Research, we conducted a study which suggests that structural changes to media systems such as the Telecommunications act of 1996 can change the nature of media effects.

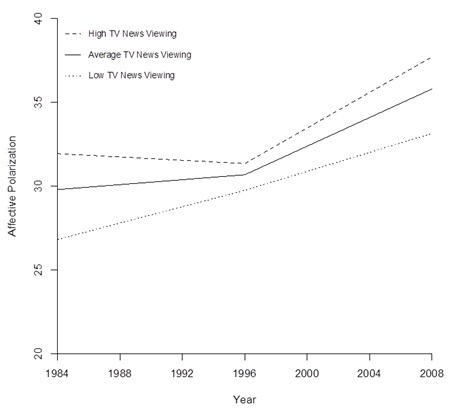

Our study found that the relationship between media and polarization changed after 1996, with TV news contributing more to polarization following the enactment of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 than it did before. After 1996, frequent consumers of TV news showed greater increases in polarization on a year-to-year basis than individuals who spent less time watching TV news (as illustrated in the figure below).

In this case, the policy changes may have encouraged the introduction of partisan media outlets (such as Fox News) and contributed to the increase in horse race coverage that focuses on the positive and negative traits of candidates instead of digging into policy debates. Many people claim that the Telecommunications Act of 1996 helped perpetuate increasing levels of media consolidation – for instance, companies like the Disney Corporation could now purchase major TV networks like ABC. Critics also argue that decreased competition among cable companies following the law led to hikes in cable prices, which incentivized media companies like Fox to create their own cable networks. As a result, there was an increase in the number of cable stations owned by big media companies.

Indeed, the addition of partisan news sources to the media system provides viewers with an opportunity to seek out information that supports their extant view of the world. Scholars have also noted that when these media conglomerates took control of networks such as ABC, news coverage suffered. News is now seen as an additional source of profit instead of a public service for viewers. This is important because the decreased funding of news departments may have contributed to increasing levels of cheap, conflict oriented programming, which has the potential to increase people’s level of polarization. As a result, watching TV news has become more polarizing for those who choose to watch.

Featured Image: Watch TV, CCO via Pixabay

The post Media policy and political polarization appeared first on OUPblog.

Are drug companies experimenting on us too much?

For years, my cholesterol level remained high, regardless of what I ate. I gave up all butter, cheese, red meat, and fried food. But every time I visited my doctor, he still shook his head sadly, as he looked at my lab results. Then, anti-cholesterol medications became available, and I started one. I still watch my diet, but my blood levels became normal.

I am deeply grateful for the drug.

Over the past half-century, pharmaceutical companies have brought us many vital drugs. But increasingly, they are now conducting trials and engaging in practices that raise serious ethical concerns. Most recently, Gilead decided to charge $94,500 for a 12 week trial of Harvoni. Another company announced a 5,000% price increase for one drug – from $13.50 to $750 a pill. (The company backed down, under pressure, announcing it would lower the price hike, but not saying by how much).

Alas, countless patients will not be able to afford these drugs. Those that can obtain them often do so through insurance, including the Affordable Care Act, yet these higher prices then get passed onto taxpayers, and other insured patients.

Drug companies argue that they charge these high prices to cover costs of research and development (R & D), but they in fact spend more on marketing (paying for countless TV ads for drugs) than on R & D. Drug companies are certainly entitled to profit, yet some economists have argued that that should be perhaps 10 times the cost of R & D, not 80 to 100 times, as sometimes occurs now.

But while drug company prices have attracted headlines, we are about to confront critical decisions regarding these corporations’ research as well. In 1974, Congress passed the National Research Act, following revelations about the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which government-funded investigators followed poor African-American men with the disease in rural Alabama. When penicillin became available as a definitive treatment, the researchers, some of whom were affiliated with our nation’s major academic medical centers, decided not to tell the men about the cure, or to offer it to them, because doing so would destroy the experiment. The 1974 Act led to the development of research ethics committees, known as Institutional Review boards (or IRBs) to protect human subjects. In the US, over 4,000 of these committees now exist, overseeing tens of billions of dollars of studies, funded by pharmaceutical companies, NIH, and others.

Research woman female scientist by Juliacdrd. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Research woman female scientist by Juliacdrd. Public Domain via Pixabay.Over the past four decades, however, science has changed; and the regulations and these committees have not kept up.

In the past, countless studies were conducted at a single institution. Now, multi-site studies are common. To recruit enough patients, researchers need to work with 50 or 60 different hospitals; and dozens of different IRBs may then be involved. Yet these committees may disagree with each other, each seeking different sets of changes in a study. The data from these various hospitals may thus be hard to merge or compare. Informed consent forms are now often 40 or 50 pages long, filled with scientific details and legalese that most patients don’t understand.

The rapidly falling costs of whole genome sequencing, from more than $1 billion to now less than $1,000 per patient, have prompted drug companies and academic medical centers to build enormous biobanks filled with the DNA of patients. Yet major questions then arise of how much control, if any, patients should have over what happens to their genetic information. These may seem like minor issues, but the best-seller, The Immortal Lives of Henrietta Lacks highlights some of the problems. Physicians removed cancer cells from Henrietta, an African-American woman who died in 1951, and subsequent research on these cells earned companies massive profits, while her family continues to live in poverty.

As a result of these various problems, on 8 September 2015, the Obama administration released a Notice of Proposed Rule Making (NPRM) which suggested several key reforms in how IRBs work and oversee research by pharmaceutical companies and others. Many of these reforms constitute important steps in the right direction – requiring that researchers use central IRBs for multi-site studies, post consent forms online, and tell participants whether biological samples may be used for commercial profit, and if so, whether these subjects will share in these rewards.

The administration is allowing public comments through until 8 December.

Yet these proposals will no doubt confront stiff opposition. Pharmaceutical companies are already fighting to lower federal oversight of research. The 21st Century Cures Act, for instance, which the US House of Representatives recently passed, and which the Senate will now consider, would significantly lower the standards that drug companies have to meet to get FDA approval for new products. Companies could then market countless drugs that may harm more than help the public.

Admittedly, not all of these suggestions are perfect – some need to be refined. For instance, the administration proposes that consent forms to be posted only after participants have all been recruited. But these forms should be available online before and during recruitment, not just afterwards. Still, these proposals can offer important benefits, and require far more public attention and discussion.

Alas, these topics are complex, because as a society, we seek to balance two ethical goals that can compete – advancing science to help society, while protecting the rights of individual study participants. That balance is not always easy to achieve – especially since science continues to evolve and grow, the NIH budget has decreased in real dollars, and drug companies are pushing to increase their profits.

Drug companies will no doubt push hard, seeking to maximize their bottom line. But all of us – as patients, family members and friends of patients, patient advocacy organizations, health care policy-makers, and citizens should attend to these questions. Ultimately, these issues affect us all.

Feature image credit: Medicine research experiment by Jelly. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Are drug companies experimenting on us too much? appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know Karl Marx? [quiz]

This October, the OUP Philosophy team has chosen Karl Marx as their Philosopher of the Month. Karl Marx was an economist and philosopher best known for The Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital. Although sometimes misconstrued, his work has influenced various political leaders including Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, and the 14th Dalai Lama.

Test your knowledge of Karl Marx in the quiz below.

Featured image credit: 100 East Germany Mark banknote. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Quiz image credit: Karl and his daughter Jenny Marx, 1869, by jensschoeffel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know Karl Marx? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

October 24, 2015

George Orwell and the origin of the term ‘cold war’

On 19 October 1945, George Orwell used the term cold war in his essay “You and the Atom Bomb,” speculating on the repercussions of the atomic age which had begun two months before when the United States bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. In this article, Orwell considered the social and political implications of “a state which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of ‘cold war’ with its neighbors.”

This wasn’t the first time the phrase cold war was used in English (it had been used to describe certain policies of Hitler in 1938), but it seems to have been the first time it was applied to the conditions that arose in the aftermath of World War II. Orwell’s essay speculates on the geopolitical impact of the advent of a powerful weapon so expensive and difficult to produce that it was attainable by only a handful of nations, anticipating “the prospect of two or three monstrous super-states, each possessed of a weapon by which millions of people can be wiped out in a few seconds, dividing the world between them,” and concluding that such a situation is likely “to put an end to large-scale wars at the cost of prolonging indefinitely a ‘peace that is no peace’.”

Within years, some of the developments anticipated by Orwell had emerged. The Cold War (often with capital initials) came to refer specifically to the prolonged state of hostility, short of direct armed conflict, which existed between the Soviet bloc and Western powers after the Second World War. The term was popularized by the American journalist Walter Lippman, who made it the title of a series of essays he published in 1947 in response to U.S. diplomat George Kennan’s ‘Mr. X’ article, which had advocated the policy of “containment.” To judge by debate in the House of Commons the following year (as cited by the Oxford English Dictionary), this use of the term Cold War was initially regarded as an Americanism: ‘The British Government … should recognize that the ‘cold war’, as the Americans call it, is on in earnest, that the third world war has, in fact, begun.” Soon, though, the term was in general use.

The end of the Cold War was prematurely declared from time to time in the following decades—after the death of Stalin, and then again during the détente of the 1970s—but by the time the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, the Cold War era was clearly over. American political scientist Francis Fukuyama famously posited that “what we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such,” with the global ascendancy of Western liberal democracy become an inevitability.

A quarter of a century later, tensions between Russia and NATO have now ratcheted up again, particularly in the wake of the Ukrainian crisis of 2014; commentators have begun to speak of a “New Cold War.” The ideological context has changed, but once again a few great powers with overwhelming military might jockey for global influence while avoiding direct confrontation. Seventy years after the publication of his essay, the dynamics George Orwell discussed in it are still recognizable in international relations today.

A version of this article first appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Image Credit: “General Douglas MacArthur, UN Command CiC (seated), observes the naval shelling of Incheon from the USS Mt. McKinley, September 15, 1950.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post George Orwell and the origin of the term ‘cold war’ appeared first on OUPblog.

History of Eurasia [interactive map]

We live in a globalized world, but mobility is nothing new. Set on a huge continental stage, from Europe to China, By Steppe, Desert, and Ocean covers over 10,000 years, charting the development of European, Near Eastern, and Chinese civilizations and the growing links between them by way of the Indian Ocean, the silk roads, and the great steppe corridor (which crucially allowed horse riders to travel from Mongolia to the Great Hungarian Plain within a year).

The map below highlights a few of the significant places of this ‘big history.’

Featured image credit: China. Crescent lake among the sand dunes of the Gobi Desert not far from Dunhuang by Barry Cunliffe. Do not use without permission.

The post History of Eurasia [interactive map] appeared first on OUPblog.

“There is figures in all things”: Historical revisionism and the Battle of Agincourt

Young Cressingham, one of the witty contrivers of Thomas Middleton’s and John Webster’s comedy Anything for a Quiet Life (1621), faces a financial problem. His father is wasting his inheritance, and his new stepmother – a misogynistic caricature of the wayward, wicked woman – has decided to seize the family’s wealth into her own hands, disinheriting her husband’s children. Young Cressingham joins forces with another disgruntled and scanted son, Young Franklin, and together they undertake to reform their disordered parents.

As the opening of the play makes clear, the greatest consequence of Sir Francis Cressingham’s error in marrying a spoiled, spendthrift young woman of the court is that he has destroyed his public reputation for probity, sobriety, and good government – fatal to his credit, and thus his financial security. “Away!” Lord Beaufort rebukes Cressingham; “I am ashamed of your proceedings, / And seriously you have in this one act / Overthrown the reputation the world / Held of your wisdom.” (Anything for a Quiet Life, 1.1.1-4) Young Cressingham must find a way, then, not only to restore his father’s position and his own inheritance, but to convince public perception that his father’s social and financial incompetence never occurred. In short, he must prove plausibly that his father was only pretending.

Lord Beaufort makes a curious comparison in his opening rebuke of Cressingham that comes back to haunt the play in its last act. “I am ashamed of you,” he tells Cressingham, “For you shall make too dear a proof of it, / I fear, that in the election of a wife, / As in a project of war, to err but once / Is to be undone for ever.” (1.1.14-18) Credit relations in early modern financial dealings were skittish enough that a single social or moral misstep could occasion a destructive spiral in which loss of reputation and financial credit, like lead weights tangled on a line, might plummet one another to an infamous and insolvent deep. So commanders, too, might lose the confidence of their troops, and never order them after.

Young Cressingham seems to remember this comparison when in Act 5 – shortly before his triumphant restoration – he compares himself to Henry V. For, like the wayward prince who later became England’s mythical warrior-king, Young Cressingham has participated with Young Franklin in some high-spirited, but low-minded, japes, including the cosening of a mercer of fifty pounds of fine fabric. It is an episode from the boys’ prodigal youth that Old Franklin sorrows to remember, when Young Cressingham mentions it:

OLD FRANKLIN Yes, I have heard of that too—your deceit

Made upon a mercer. I style it modestly;

The law intends it plain cozenage.

YOUNG CRESSINGHAM ‘Twas no less,

But my penitence and restitution may

Come fairly off from’t. It was no impeachment

To the glory won at Agincourt’s great battle,

That the achiever of it in his youth

Had been a purse-taker—this with all reverence

To th’ great example. (5.1.17-25)

For Middleton and Webster, the example of Agincourt, and of Henry V’s miraculous transformation in its purgative combat, seems at first to represent a moment of historical singularity, a moment in which the prodigal prince’s illicit past was deleted from the historical record and he was created anew.

But this would be to read a little too quickly. Not only did the purse-taking of his youth not impeach Henry V when he came to fight the French at Agincourt, but in fact it came in some way to enable and explain that later victory. Young Cressingham makes from the stolen fabric of Act 2 a new suit for his father, and in these clothes presents him before Lord Beaufort to his wife. She, taking the opportunity that her stepson has offered, claims that she never meant to disinherit him, nor to defraud or emasculate her husband, but only to teach him financial responsibility. Middleton and Webster have been criticised for failing to explain her abrupt change of heart, but in fact their understanding of psychology and ethics is as brilliant as it is subtle. Lady Cressingham sees from Young Cressingham’s own unexpected reformation that her reformation will also rewrite the meaning of her past actions, retrospectively making her volta, like his, expectable. They both recuperate past errors into present triumphs by making it seem as if their errors were no errors, but part (like Prince Hal’s skilful offences) of a shrewd plan.

The lesson is not lost on Sir Francis Cressingham, who immediately declares to the assembled company (much to his son’s delight) that he had expected the very thing that has just caught him by surprise:

CRESSINGHAM All this I know before; whoever of you

That had but one ill thought of this good woman,

You owe a knee to her and she is merciful

If she forgive you. (5.2.291-94)

Cressingham at a stroke recovers his reputation and his financial credit, and in turn his son’s inheritance – by the simple pretense that he always meant to err.

For Middleton and Webster, as for Shakespeare in Henry V, Agincourt provides the emblem and example for this sort of historical revisionism. It is a commonplace of Shakespeare criticism to note how carefully the playwright constructs Prince Hal’s developing mastery of finance, credit, and reckonings through the tavern scenes of 1 Henry IV and 2 Henry IV. The mingled language of purchase, debt, and redemption on the one hand, and military triumph on the other, reaches a fever pitch of fusion in Act 3, scene 2 of 1 Henry IV, when Hal in part reveals his cunning to his doubtful, anxious father. By the time the new king sets sail for France in Henry V, Shakespeare has made him a consummate practitioner of these revisionist and redemptive arts, and they serve him perfectly at Agincourt.

As Fluellen and Gower stride onto the stage in Act 4, scene 7, they are discussing the perfidy of the retreating French knights, who have raided the abandoned English camp, killed the English army’s unarmed boys and servants, and stolen their valuables:

FLUELLEN Kill the poys and the luggage! ‘Tis expressly against the law

of arms. ‘Tis as arrant a piece of knavery, mark you now, as

can be offert. In your conscience now, is it not?

GOWER‘Tis certain there’s not a boy left alive. And the cowardly

rascals that ran from the battle ha’ done this slaughter.

Besides, they have burned and carried away all that was in

the King’s tent; wherefore the King most worthily hath

caused every soldier to cut his prisoner’s throat. O ’tis a

gallant king. (Henry V, 4.7.1-10)

Henry is praised for his justice, in taking French lives to answer for his English dead – be they never so lowly. But a great deal depends on Gower’s “wherefore”, here, and the historical sources from which Shakespeare worked clearly did not justify so conjunctive a transition. As Raphael Holinshed reports in his Chronicles (London, 1587), Henry acted not out of justice, but out of fear:

But when the outcrie of the lackies and boies, which ran awaie for feare of the Frenchmen thus spoiling the campe, came to the kings eares, he doubting least his enimies should gather togither againe and begin a new field; and mistrusting further that the prisoners would be an aid to his enimies, or the verie enimies to their takers in deed if they were suffered to liue, contrarie to his accustomed gentlenes, commanded by sound of trumpet, that euerie man (vpon paine of death) should incontinentlie slaie his prisoner. When this dolorous decree and pitifull proclamation was pronounced, pitie it was to see how some Frenchmen were suddenlie sticked with daggers, some were brained with pollaxes, some slaine with malls, other had their throats cut, and some their bellies panched, so that in effect, hauing respect to the great number, few prisoners were saued. (Holinshed, Chronicles, p. 554)

Misunderstanding the nature of the screams he was hearing, and believing that the enemy might be rallying for a fresh attack, Holinshed’s Henry realised that his own men could not engage them while they were encumbered by the need to ward and protect their prisoners. For fear lest those prisoners should impeach them – valuable though their ransoms might be – the king ordered them slaughtered. Fluellen’s and Gower’s revisionism recuperates Henry’s frantic misjudgment as its opposite, an exemplum of kingly judgment.

But the rest of their discussion makes clear that Shakespeare, like Middleton and Webster in their comedy, was well aware, and skeptical about, the process by which reputations were made. When Fluellen calls Alexander the Great “Alexander the Pig,” the joke occasioned by his allegedly Welsh mispronunciation allows him to drive home the skeptical argument:

FLUELLEN Why I pray you, is not ‘pig’ great? The pig or the great or the

mighty or the huge or the magnanimous are all one

reckonings, save the phrase is a little variations. (4.7.15-17)

That Alexander can be remembered by a Welshman at Agincourt, that he enjoys enough fame to have his title mangled, is a sign of his greatness – so, “pig” might as well, in the “reckoning”, be “magnanimous”. Fluellen further, inexpertly, draws a parallel between Alexander and Henry on the basis that Monmouth and Macedon, the respective birthplaces of Henry and Alexander, both have rivers, “and there is salmons in both” (4.7.28). For, as he argues, “there is figures in all things” (4.7.30), and so it is that Alexander’s splenetic and drunken murder of his friend Cleitus comes to stand as an example for Hal’s sober and mature dismissal of his one-time companion Sir John Falstaff.

The appetite of the historical mind for the figure, the appetite to reverence the great example, is so strong that it imposes it upon both superficial stuff (two locations beginning with m that have rivers) and utterly disparate stuff (a drunken murder, a sober judgment). This – or so Shakespeare implies by situating Fluellen’s and Gower’s bumbling conversation between the battle in Act 4 scene 6 and the final reckoning of the French and English dead in Act 4 scene 8 – is the true lesson of Agincourt. When Hal stands before the English troops to refashion his Machiavellian escape as a victory sent from God, he is only doing what Young Cressingham will do 20 years later: figuring things to his advantage.

Featured image: Facsimile of the Agincourt Carol (15th century). Oxford, Bodleian Library, Manuscript Archives. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “There is figures in all things”: Historical revisionism and the Battle of Agincourt appeared first on OUPblog.

What might superintelligences value?

If there were superintelligent beings – creatures as far above the smartest human as that person is above a worm – what would they value? And what would they think of us? Would they treasure, tolerate, ignore, or eradicate us? These are perennial questions in Western thought, where the superior beings are Gods, angels, or perhaps extraterrestrials. The possibility of artificial intelligence gives these old questions a new life. What will our digital descendents think of us? Can we engineer human-friendly artificial life? Can we predict the motivations or values of superintelligence? And what can philosophers contribute to these questions?

Philosophical debate about the relationship between beliefs and values is dominated by two eighteenth-century thinkers: David Hume and Immanuel Kant. Humeans draw a sharp divide between belief and desire. Beliefs are designed to fit the world: if the world doesn’t fit my beliefs, I should change my beliefs. Otherwise, I am irrational. But desires are beyond rational criticism. If the world doesn’t fit my desires, I should change the world! As Hume colourfully put it: “Reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions.” Learning more about the world may tell you how to satisfy your desires, but it shouldn’t change them.

Kantians disagree. They argue that some things are worth wanting or doing, while others are not. Gaining extra knowledge should change your desires, and the desires of rational beings will ultimately converge.

Popular debate about superintelligence sides with Hume. Superintelligent agents can have any arbitrary desires, no matter how much knowledge they acquire. Indeed, one popular rational requirement is an unwillingness to change your desires. (If you allow your motivations to change, then your future self won’t pursue your present goals.)

Humeanism about superintelligence seems reasonable. Possible artificial minds are much more diverse than actual human ones. Superintelligence could emerge from programmes designed to make paperclips, fight wars, exploit stock markets, prove mathematical theorems, win chess games, or empathise with lonely humans. Isn’t it ridiculous to expect all these radically different beings to want the same things? Even if Kantian converge exists, it only applies to rational agents with conscious goals, plans, values. But a myopic machine could be superintelligent in practice (i.e., superefficient at manipulating its environment to satisfy its desires) without any rational sophistication.

Future of the Earth by Fsgregs. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Future of the Earth by Fsgregs. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.However, the debate between Hume and Kant does matter in one very important domain. Suppose we want to engineer future superintelligences that are reliably friendly to humans. In a world dominated by superintelligences, our fate depends on their attitude to us. Can we ensure they look after us? Superintelligences can only reliably benefit creatures like us if they understand – from the inside – what it is like to have goals that can be thwarted or advanced, experiences that can be pleasant or distressing, achievements that can be shallow or deep, relationships that can go well or badly. Reliably friendly superintelligences must be rational agents. But then, if Kant is right, their values will converge.

Here is one possible route to convergence. Even Humeans agree that every rational agent wants knowledge. Whatever your goals, you will pursue them more efficiently if you understand the world you inhabit. And no superintelligence will be satisfied with our shallow human understanding. In their quest to truly understand the universe, superintelligences might discover a God, a cosmic purpose, a reason why the universe exists, or some other source of transcendent values. Until we understand the universe ourselves, we can’t be confident that it can be truly understood without positing these things. Perhaps this cosmic knowledge reliably transforms every rational agent’s desires – leading it to freely abandon its previous inclinations to embrace the cosmic purpose. (Artificial agents, who can reprogramme themselves, might undergo a much more wholesale motivational change than humans.)

It is tempting to think that, even if Kantianism and theism are true, they can safely be ignored. If superintelligences converge on divine purpose or correct values, surely they will be friendly to us? We should presuppose Humeanism, not because it is necessarily correct, but because that is where the danger lies.

This optimism is illicitly anthropocentric. We might expect humans to converge on human-friendly values, and to worship a God who cares for us. But we cannot attribute our values to superintelligences, nor to the God they might discover. Perhaps superintelligences will posit a God to whom we are simply irrelevant. Superintelligences designed to be friendly to humans may one day realise that we do not matter at all – reluctantly setting us aside to pursue some higher purpose.

This raises an especially worrying prospect. We naturally think that we should try to engineer reliably friendly superintelligence. Even if we fail, we won’t do any harm. But if superintelligent rationality leads to non-human values, then we might end up worse-off than if we had left superintelligence to its own devices and desires.

Featured image credit: Connection, by geralt. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What might superintelligences value? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 23, 2015

Which persona are you?

The US Supreme Court has been a vessel for controversy, debate, and deliberation. With a variety of cases filtering in and out each year, one would suspect that the Supreme Court’s decisions would be varied. However, Cass Sunstein, one of the nation’s leading legal scholars, demonstrates that nearly every Justice fits into a category, regardless of ideology. In his latest book, Constitutional Personae, Sunstein breaks these personalities into four distinct groups: the hero, the soldier, the minimalist, and the mute. Which persona would you most likely be? Check out this infographic and decide which category you most align with.

Download a JPEG or PDF version of the infographic.

Image Credit: “Supreme Court US 2010″ by Steve Petteway. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Which persona are you? appeared first on OUPblog.

Q & A: Neurology’s past, present, and future

To mark the release of Martin R. Turner and Matthew C. Kiernan’s Landmark Papers in Neurology, we spoke with the two editors, to discuss their thoughts on neurology – past and present. We asked about the origins of neurology, the understanding of neurological diseases, milestones in the field, why historical context is so important – and their predictions for the future…

What were the origins of neurology as a specialty and the understanding of neurological disease?

Turner – Neurology was quite a late speciality and many of the 19th century pioneers would have called themselves general physicians, anatomists or pathologists. Regrettably, it was the preserve of only relatively rich males in the early years. They were great observers of patients in life and then related it to the detailed anatomy of their bodies after death. Everything was recorded and published in rigorous detail. Patterns were spotted that told us far more about the clinical breadth of neurological conditions than modern diagnostic equipment has done to date.

How has the understanding of neurological diseases improved in the last ten to twenty years?

Turner – In my own area of neuroimaging, it is staggering how things have developed. The ability to see the brain structure without opening the skull changed everything almost overnight. MRI scanners were science fiction a few decades back, and the latest applications would not have been dreamt of when the first grainy black and white pictures first emerged. The explosion in molecular biology, at the genetic and cellular levels, is leading to a complete reclassification of disease. This is colliding with the traditional view of Medicine, defined by Osler, in which diseases are classified according to clinical methods. In fact, both will necessarily develop in tandem.

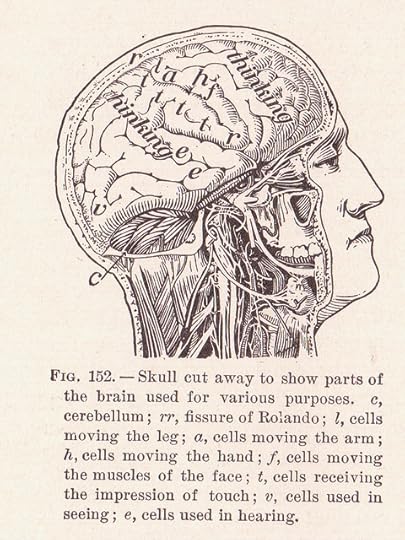

Image Credit: ‘Our Brain’ from ‘The Human Body and Health’ by Alvin Davison (1908), image by Sue Clark, CC by 2.0, via Flickr.

Image Credit: ‘Our Brain’ from ‘The Human Body and Health’ by Alvin Davison (1908), image by Sue Clark, CC by 2.0, via Flickr.Kiernan – Most importantly, we are now living in a therapeutic era. That maxim is no better illustrated than by considering multiple sclerosis and neuro-inflammation more generally. The transformation has been remarkable. With a rapidly developing armamentarium of immunomodulatory medications, the outcomes for patients diagnosed with MS today is significantly better than it was twenty years ago.

What are some of the most major milestones in the evolution of neurology?

Turner – Pondering this was the basis for the first ‘technological’ chapter, which Matthew and I decided to take on, with our good friend Kevin Talbot. We identified three broad areas, namely i) imaging the nervous system (from brain to nerve cell), ii) understanding the neurophysiology of the nervous system, and iii) its molecular biology. We each took on the part in which we do most of our research.

Kiernan – Neuroscience research and clinical development is now largely dependent on the technology of the day. While Charcot was limited to pathological assessment, obtained through post mortem examination, we are lucky to be living in an era of unprecedented technological advance. With that comes the hope that better treatments will become available for our patients. With significant developments across electronic media, and planned changes in free and open access for all medical research, the traditional textbook and medical journal approach may begin to have less meaning. Clinicians and emerging clinicians, whilst previously having turned their attention to their favourite journal, may now be more engaged with Facebook and Twitter – and of course their favourite blogs!

Why is it important for neurology trainees to have an understanding of the historical context of their subject?

Turner – The digital medical library has brought many advantages, and all at the click of a mouse. However, though many pre-1950s papers are being added each month, it still does not allow the reader to gain a sense of context, ‘the long view’ and critical appraisal that only comes from someone immersed in a field for many years. In my own area of ALS, time and again I have gone back to the works of the original pioneers of neurology (Charcot, Gowers) and been humbled to find that they already knew much of what we arrogantly imagine has come from modern clinical practice. Other times it has made me think differently about the whole basis for neurodegeneration.

Kiernan – There is also increasing pressure on authors to cite only the recent developments in their field. Publishers of many high impact journals exhort prospective authors to cite manuscripts from the past five years. Such pressure may link in turn to the metrics of today and the dreaded impact factor. What is the true impact of medical discovery? Perhaps there has been a gradual distortion from a desire to improve patient outcomes, to considerations about generating personal acclaim and funding. As such, it is refreshing to consider discovery for discovery alone, and to hear how the key drivers of science today rate their field, irrespective of such considerations.

How do you predict our understanding will change in the next ten to twenty years?

Turner – The last 10-20 years have shown me that whatever we predict will likely be wrong! One thing is clear though, namely that neuroscience really is the next great frontier in Medicine. I hope more than anything that in my career there will be a sudden collision of Mathematicians, Physicists and Neurologists that will unlock the basic mechanics of the brain.

Kiernan – Thinking Neil Armstrong type moments, it does not seem inconceivable that paralysed patients will be able to walk, brain-implanted microchips will eradicate the need for computers as we know them, and that damaged body parts may be replaced by neuroprostheses. Who knows? But it will be an interesting journey!

Featured Image Credit: ‘Neurons, Brain Cells, Brain Structure’, by geralt, CC0 Public Domain, via Pixabay.

The post Q & A: Neurology’s past, present, and future appeared first on OUPblog.

The ethics of criminological engagement abroad

Criminological knowledge originating in the global North is drawn upon to inform crime control practices in other parts of the world. This idea is well established and most criminologists understand that their efforts to engage with policy makers and practitioners for the purpose of generating research impact abroad can have positive and negative consequences. Ideally, these knowledge transfer activities will positively address local and transnational problems and contribute to just outcomes. Sometimes however, the policies and practices they inspire may prove harmful.

An oft-cited example of criminology’s harm-generating potential involves the spread of ‘Broken Windows’ policing throughout Latin America. The embrace of this model by conservative politicians in many Latin American countries has in part been attributed to the efforts of high profile American criminologists to actively market it as a solution to the region’s crime problem. It is safe to assume that the intentions of its scholarly proponents were benevolent, but the model is nevertheless associated with increased police violence and the over-policing of the urban poor.

A third possibility is that attempts by criminologists to promote their research abroad may fail to generate any discernible impact whatsoever. A lack of impact might reasonably be described as an unfortunate outcome when it comes to criminal justice and security sector reforms in countries with poor human rights records. However, the example of ‘Broken Windows’ policing in Latin America indicates that limiting impact may actually be desirable when it comes to the exportation of criminological knowledge that is oriented towards enhancing the efficiency of state institutions of social control.

It is worth briefly contextualising this argument by reflexively considering how the ‘impact-agenda’ in higher education has come to shape the manner in which criminological knowledge is produced and disseminated. The analysis is rooted in the British experience, but many of the issues raised here are also pertinent to other contexts. The starting point is to acknowledge that it is increasingly difficult for scholars to maintain a separation between research activities intended to generate knowledge, and those that involve the dissemination of knowledge to research users.

Structurally, this dynamic reflects increased political pressures for the higher education sector to demonstrate its social utility if it wishes to retain its public funding. This, in turn, generates increased managerial pressures for academics to ensure that their scholarship is both topical and practical in its applications. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but it does create challenges. Image credit: What? by Véronique Debord-Lazaro. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: What? by Véronique Debord-Lazaro. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

For criminologists, practical relevance often boils down to making research relevant and attractive to policy makers and practitioners. In fact, for researchers hoping to attract external funding, develop collaborations, and secure access to conduct research with criminal justice agencies, it is expected that they will actively incorporate knowledge co-production activities into various stages of the research process. Knowledge co-production can have important benefits for researchers and research users alike but it can also represent a potential threat to academic autonomy. Specifically, collaborations of this nature risk prioritising the attainment of specific outcomes over knowledge generating activities. They may even prove counter-productive with respect to the development of evidence-based policies by creating pressures for criminologists to generate evidence that serves to validate or support a pre-defined policy agenda or intervention.

In an age of research benchmarking exercises, it is also not enough for researchers to claim that their findings are policy relevant. Rather, they must actively seek out and create opportunities that will allow them to use their research to bring about measurable change. Countries in the global South may appeal to entrepreneurial-minded criminologists as ‘low hanging fruit’ because the legacy of colonialism and enduring global asymmetries ensure that many southern policy makers and practitioners continue to favour northern solutions to their problems of order, even if implementing these solutions is unfeasible or problematic. The fact that international organisations and NGOs are frequently willing to assist entrepreneurial criminologists with disseminating their proposals in the South further enhances the appeal of targeting these environments for impact. The strategic benefit of these collaborations is that they promise to equip criminologists with a level of political capital that far exceeds that which they enjoy in their home countries. In some cases, it even provides them with a means of influencing domestic legislation and policies without subjecting them to democratic scrutiny.

Democratic deficits aside, the main problem is that anticipating the potential implications of international knowledge transfer activities is inevitably difficult in cases where the researcher is a cultural and contextual outsider. Contextual ignorance may therefore restrict the ability of criminologists as social researchers to fulfil their ethical obligation to minimise harm. The principle of harm minimization has traditionally been associated with the knowledge production process, but as the boundaries between knowledge production and knowledge dissemination become increasingly fuzzy, criminologists must ensure that impact-oriented activities are also compliant with this principle.

The question is how might criminologists go about navigating this ethical minefield? Part of the answer involves shifting the focus of impact from achieving specific outcomes to facilitating deliberative processes. The primary goal of process-oriented research engagement is therefore to facilitate and contribute to better transnational dialogues that foster enhanced cross-cultural understandings of mutually relevant issues. This stands in contrast to those activities that aspire to translate a pre-determined model into policies and practices that address a pre-defined problem. The dialogues I refer to can take place in the public sphere or in private nodes of governance, but according to political theorist John Dryzek, they must be discursively representative, meaning that they are ‘authentic, inclusive and consequential.’ For criminologists and other social researchers, enabling these dialogues necessitates that they continuously exercise modesty, reflexivity and restraint during their travels around the world.

The post The ethics of criminological engagement abroad appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers