Oxford University Press's Blog, page 534

March 17, 2016

Meeting Helmut Schmidt: the man behind the statesman

15 October 2015. Another cold, grey afternoon in Hamburg-Langenhorn. My last research visit to Helmut Schmidt’s private archive next to his home, a simple bungalow in the northern suburbs of the city. I was there to check some final references before sending my book off to press. But unexpectedly there was a chance to say hello to the former Chancellor, now ailing and housebound, before I took a taxi to the airport. It turned into a full hour of animated discussion, a meeting that I shall never forget – and one that was very different from our only other personal encounter two years before, on my first trip to Hamburg.

I had already been researching the book for a couple of years, spending weeks in governmental archives on both sides of the Atlantic – in Bonn, Berlin, Koblenz, Paris, London, Washington, Atlanta and so on. From this cornucopia of official telegrams, minutes of meeting, and policy memos I gained a vivid impression of Schmidt as a major player on the international stage – totally at ease with the likes of Kissinger, Giscard and Brezhnev, pushing himself into the role of self-styled ‘double interpreter’ between East and West at the nadir of the ‘New Cold War.’ I discovered that he was far more than the man who features in many of the biographies – the German politician, besieged by party problems and forever in the shadow of his charismatic predecessors Adenauer and Brandt. Hence, for me, he is the ‘global chancellor.’

This image of Schmidt the international statesman was reinforced by my first meeting with him in October 2013. Highly formal, it took place in his personal office in the HQ of Die Zeit, the German weekly newspaper, with a grand view across the city to the Elbe. He was sitting on the other side of a huge modern desk – immaculately dressed in pink shirt and two-piece suit, with a handkerchief carefully folded in his breast pocket, and surrounded by ceiling-high shelves packed with books that he had written. The pressure was increased by the smokescreen that Schmidt put up between himself and the visitor: he must have got through at least twenty of his notorious menthol cigarettes in two hours.

Image credit: President Reagan stands with Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and Berlin Mayor Richard von Weizaecker at “Checkpoint Charlie” at the Berlin Wall. 6/11/82 by Ronald Reagan Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: President Reagan stands with Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and Berlin Mayor Richard von Weizaecker at “Checkpoint Charlie” at the Berlin Wall. 6/11/82 by Ronald Reagan Library. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.This was clearly political theatre. Here was Helmut Schmidt the Elder Statesman, aged 94 yet still a consummate operator. You were left in no doubt of being in the presence of a supreme political animal, self-consciously aware of his power and position. The conversation unfolded like a summit meeting – and one in which he held the best cards and could call the shots. The afternoon proved useful, up to a point. I got a feel for his personality but he evaded most of my politically sensitive questions on matters of substance. His main aim, it seemed, was to confirm the image he had created for himself, through his memoirs and journalistic commentaries ever since leaving office in 1982.

That was before I really started to encounter Helmut Schmidt through his personal papers. Over the next two years I paid a couple of dozen visits to his private archive, located in a modern glass building in his garden. I pored over thousands of pages of letters, speech manuscripts, newspaper commentary and book drafts from the 1950s to the 1980s – many of them sheets of paper scrawled in his own hand or typescripts covered by annotations in his famous green pen. Gradually I penetrated an intellectual hinterland that other authors on Schmidt seemed to have missed.

Schmidt always repudiated the tag ‘intellectual’ but he was undoubtedly a thinker and writer, full of energy and ambition, who thrived on argument. No wonder he called politics a Kampfsport: the more challenging the adversary the better, because he loved to stretch his own intellectual capacities. Writing so much in English helped gain him the international recognition that he craved, especially in America and not least from a young Harvard professor called Henry Kissinger. These insights, gleaned from his Eigene Arbeiten files, proved fundamental to my understanding of Schmidt as both ‘world economist’ and ‘strategist of balance.’ But it also helped me to understand the gamesmanship of that first meeting. The vanity and arrogance was not mere display: his palpable self-assurance was rooted in real intellectual power.

My second personal meeting in October 2015 was very different from the first. It took place in the study of his home, full of mementoes from his travels – a much friendlier environment than the cool, clear Die Zeit office. Schmidt had been seriously ill and was convalescing at home, wearing a zipped-up polo shirt. Once again we faced off across a desk and the cigarette smoke was ever present, but this time there was coffee and biscuits and the tone was firm yet gentle. This wasn’t a summit but a conversation.

I tried out on him some of the main conclusions of my book – about his key political friendships, about China and Russia, and about how Germany had come of age through his chancellorship. Increasingly animated, he suddenly switched from German into English, maybe just to remind me that he was still the boss. Yet there was now a twinkle in his eye. And a more human dimension of Schmidt emerged as the hour progressed: we chatted about his war experience, his passion for music and the pleasure of performing in public as a pianist. By the end I was on his side of the desk – captured in this photo snapped just before I left.

Three weeks later Helmut Schmidt was dead.

Headline image credit: Photo of Kristina Spohr and Helmut Schmidt, October 2015. © Kristina Spohr. Used with permission

The post Meeting Helmut Schmidt: the man behind the statesman appeared first on OUPblog.

Affekt: the foundational pillar in eighteenth-century music

How does one capture the Classical style sound aesthetic when approaching performance of eighteenth-century repertoire on the modern piano? Although it is important to know of the period instruments and their associated physical sound qualities, knowing how period musicians approached their art emotionally and intellectually provides even deeper insight into discovering how to recreate the sound aesthetic. And in doing so, we turn to affekt, probably the single most influencial factor upon which the eighteenth century musical experience is built. Every esteemed treatise from the eighteenth century impresses upon the reader the immense importance of understanding the influence of affekt on playing. Whether it was Leopold Mozart in his Violinschule, Türk in his Klavierschule, Kirnberger in his The Art of Strict Musical Composition, or Quantz in his On Playing the Flute, affekt is at the crux of this music-making matter.

Affekt, the ability of music to stir emotions, was described in a variety of ways, including character, affections, expression, affect, and emotion. It was achieved through attention to detail and proper execution — and done in good taste, which implies a deep understanding of proper practices of the time. All manner of composition and performing, from formal structure down to phrasing and execution of individual notes had the understanding of affekt at its foundation. Nearly every notational and performance decision was based on affekt: note values, dynamics, articulation, etc.

“Whoever performs a composition so that its inherent affect (character) is expressed (made perceptible) to the utmost even in every single passage, and that the tones become, so to speak, a language of feelings, of him one says that he has a good execution. Good execution, therefore, is the most important, yet at the same time the most difficult aspect of music making.”

—Daniel Gottlob Türk, Klavierschule (1789). Translated by Raymond H. Haggh. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press (1982), 321.

Looking to specifics in eighteenth-century practice, meter decisions have a strong influence on affekt. Baroque dances and their varying affekt are expressed through the intentional use of specific meters. The time signature alone also describes the weight of a piece: a two in the denominator indicates a heavier weight or execution, a four in the denominator calls for a lighter weight, and an eight in the denominator indicates an execution that is lighter yet. A textbook example of this concept is found in Sonatina in C Major, Op. 36, no. 1 by Muzio Clementi.

Likewise, specific note values project affekt. A passage primarily containing half notes is associated with a heavier sound and affekt, a quarter note passage is lighter, and a passage full of eighth notes is lighter yet. This is also evidenced in the Clementi Sonatina.

The chosen key center of each composition is particularly married to an associated affekt. Furthermore, the tuning system (mean tone tuning) of the period makes the affekt of a given key even more marked. Three varying examples from eighteenth-century repertoire bear witness to and support this idea.

The key of C major is associated with simplicity, joy, and purity in Sonatina in C Major, op. 36, no. 1 by Clementi

The key of F# minor is associated with melancholy, gloom, and discontentment in Prussian Sonata for Piano, Wq 48, no. 6 by C. P. E. Bach

The key of A major is associated with playfulness, jesting, and gaiety in Sonata in A Major, op. 2, no. 2 by Beethoven

Understanding the intentionality of eighteenth-century composers’ choices allows the modern pianist the opportunity to develop a new perspective regarding Classical Era repertoire. Look at a new piece of music from the Classical Era (to avoid pre-conceived notions). Using eighteenth century conceptual understanding, experiment with various approaches to incorporate the elements into the fabric of the piece with an end goal of expressing affekt.

Analyze the form of the piece. What is the musical concept? Is this a minuet, a waltz, or a march?

Examine the meter. Based on the time signature should the piece be heavy and majestic or light and frivolous?

Examine the chosen note values to determine the described affekt.

Determine the key centers in the piece. What affekt clue is the composer providing from these key centers?

Much of eighteenth-century scoring leaves room for individual input that allows for changes or variations in articulation, rhythmic and dynamic grouping, pedaling, textural balance, and use of agogics to create the desired affekt. Use of Urtext editions is crucial to achieve this goal.

Conceptual elements come first. It may seem easier to focus on physical execution details such as note values, articulation, and ornaments but the over-riding point (affekt) may be entirely missed. When time is taken to work through concepts first, it will pay handsomely in terms of overall practice efficiency and historically-informed outcomes. The reward will be understanding and executing the gestalt of eighteenth century performance practice: affekt and good taste.

Image credit: “Beethoven Sympony No.5” by Open Grid Scheduler / Grid Engine. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Affekt: the foundational pillar in eighteenth-century music appeared first on OUPblog.

March 16, 2016

Five years after: The legacy of the Japanese anti-nuclear movement

This month marks the fifth anniversary of 3.11–the moniker for the earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima nuclear disaster that struck northeastern Japan on 11 March 2011, killing nearly 20,000 and displacing as many as 170,000 people. In addition to mourning for lost souls, the anniversary was marked by loud anti-nuclear protests all over Japan: Osaka, Nagoya, Kyoto, Naha (Okinawa), Kōfu (Yamanashi Prefecture), Oita (Kyushu), Hachiōji, and several in Tokyo, where the weekly Friday protest around the prime minister’s residence attracted 6,000 protesters on this anniversary evening. While a small number compared with the 200,000 that this protest attracted at the height of the Japanese anti-nuclear movement in summer 2012, these protests have nonetheless been remarkable in their persistence and resilience: They have been occurring weekly for four years.

Anti-nuclear protest, Tokyo, 11 March 2016

But as the number of protesters dwindles, some might wonder what all the noise was for. Since Prime Minister Abe Shinzō and the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) regained power in December 2012, the government policy has been to restart nuclear power plants, all of which were shut down for scheduled maintenance, then kept closed after the Fukushima nuclear accident. The dwindling numbers of protesters are a reflection of the seeming futility of protesting in light of foregone conclusions. And many English-language editorials written for the fifth anniversary bemoan Japan’s lack of progress since the epoch-making crisis and express disappointment that Fukushima is being forgotten.

Nonetheless, the post-3.11 anti-nuclear movement did leave a legacy. While most Japanese were positive about nuclear power before the Fukushima accident, surveys since mid-2011 have consistently shown that 60-70% of the population now favors a complete abolition or phase-out of nuclear power. Furthermore, public pressure, including constant demonstrations, drove the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), the ruling party at 3.11, to shut down, and keep shut, the nuclear reactors until stricter regulatory standards could be ratified. The 200,000-strong protests that accompanied the restarting of two reactors at the Ōi Nuclear Power Plant in July 2012, before these standards could be put in place, showed that the public would not tolerate restarts without a fight. Shortly afterward, a new regulatory agency, the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), was established. After the Ōi reactors were shut down for maintenance in September 2013, Japan lived without nuclear reactors unproblematically through two summers of record-breaking heat, raising further doubts as to the necessity of nuclear power. And both the courts and the NRA seem less forgiving of the nuclear industry. Last week, the Otsu district court in Shiga Prefecture forced a shutdown of the recently started Takahama Nuclear Power Plant, citing concerns over safety and inadequate emergency protocols. The NRA has declared the problem-ridden Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) as unfit to operate the accident-prone Monju Fast-Breeder Reactor (FBR) — feared for its use of plutonium-spiked MOX fuel and liquid sodium, which is highly combustible, as coolant — creating a path to its possible decommissioning. The FBR had been famously lampooned as Monjukun, a Twitter character personifying the reactor — which had been upheld as the pinnacle of Japanese nuclear prowess — as a sickly boy who wets his pants, effectively emasculating nuclear power.

Akuryō and I Zoom I Rockers in front of METI, 29 July 2012 protest

Monjukun ondo (dance), Atomic Café, July 2012

Most importantly, the nuclear crisis awakened (or reminded) a politically apathetic population that neither the benevolence of governmental policies, the righteousness of corporate actions, nor free expression could be taken for granted. The anti-nuclear movement that arose from anger at this discovery helped the Japanese to raise their voices. Music played a key role in breaking the silence and validating people’s thoughts and feelings. Foremost among these were the songs released early on, like Saitō Kazuyoshi’s “It Was Always a Lie,” which broke record-industry conventions by calling out Tokyo Electric Power (TEPCO) and other power companies by name and expressing worries about radiation in the air, water, and food. Rankin Taxi’s “You Can’t See It, You Can’t Smell It Either” made dead-serious arguments about media manipulation while invoking cringe-worthy laughter. These songs became the soundtrack to the protests that recurred from spring 2011 onwards. These protests, which often numbered in the tens of thousands, attracted a diverse group of people of multiple ages, classes, and political leanings. They established that protesting was not just for extremists and labor unions, but that ordinary citizens can come together through social networks. They also popularized the musical practices that encourage the Japanese to participate in protests, in particular the drum corps that accompany every demonstration and the call-and-response style in which rappers and protesters exchange slogans over R&B and hip-hop beats.

Rankin Taxi, “You Can’t See It, You Can’t Smell It Either”

Many of these protesters have transferred their activism to the movement against Abe’s policies, in particular the Secrecy Law, which many have flagged as a threat to a free press, and the Security Bills, which allow Japan to send troops overseas for the first time since World War II. These protests have featured greater involvement by university students, led by SEALDS (Students Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy), and high-school students, led by T-ns Sowl. These demonstrations often feature rapped call-and-response patterns over hip-hop and EDM beats — a continuation of the pattern first begun by anti-nuclear rappers Akuryō, ATS, ECD, and I Zoom I Rockers. Ahead of the final vote on the Security Bills in September 2015, SEALDs conducted protests every Friday in front of the Diet, alongside the anti-nuclear groups, members of which acted as mentors to the students. At the peak of these protests on 30 August 2015, 120,000 protesters gathered in front of the Diet. Protests have continued since the Security Bills passed, and they often include calls against nuclear power. Indeed, the anti-nuclear movement has effectively been folded into a more generalized movement against oligarchical control.

SEALDs anti-militarization protest, Omotesandō, Tokyo, 23 August 2015

Furthermore, the musicians who were active in the anti-nuclear movement have continued to speak out in this broader movement. Since 3.11, the Fuji Rock Festival has hosted the Atomic Café stage for discussions and performances in regards to nuclear power and other political issues. Among the hit performers on this stage has been the Ese Timers, a group featuring prominent anti-nuclear musicians Gotō Masafumi of Asian Kung-Fu Generation, Toshi-Low of Brahman, Hosomi Takeshi of Hiatus, and Tsuneoka Akira of Hi-Standard; the band is a homage to the Timers, formed by rocker Imawano Kiyoshirō after he gained infamy for recording the anti-nuclear song, “Summertime Blues,” in 1988. In 2015, Toshi-Low and Hosomi sang “Let’s Join the Self-Defense Forces,” a 1968 anti-war song that had been revived through the sarcastic 2011 anti-nuclear rewrite, “Let’s Join TEPCO.” The latter song had led to the rediscovery of the anti-war song, which could now be redeployed with new meaning. The anti-nuclear movement had inspired Japanese celebrities to make a political stand, and in turn, they and their music had inspired the people to raise their own voices. Policies may not have changed, but the people have.

Featured image: Fukushima (c) traffic_analyzer via iStock.

The post Five years after: The legacy of the Japanese anti-nuclear movement appeared first on OUPblog.

“Vulpes vulpes,” or foxes have holes. Part 1

The idea of today’s post was inspired by a question from a correspondent. She is the author of a book on foxes and wanted more information on the etymology of fox. I answered her but thought that our readers might also profit by a short exploration of this theme. Some time later I may even risk an essay on the fully opaque dog. But before coming to the point, I will follow my hero’s habits and spend some time beating about the bush and covering my tracks.

The origin of animal names is often hard to discover because many of them are so-called taboo words. People were afraid to call wild and destructive animals by their “real” names and substituted new ones for those in existence. Sometimes we can follow the process of substitution. The Greek word arktós, from which English has Arctic, is related to Latin ursus “bear,” familiar to English speakers from Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, and the female name Ursula “little she-bear.” The protoform must have begun with (a)rkt– or something similar. Did the sound-imitative root rkt– or rkth– mean “roar” (like the Russian noun rokot)? In any case, the Indo-European brown bear, although it probably had no idea that its female partner was associated with two constellations, must have realized that people had learned its name. Therefore, it became dangerous to pronounce something like arkti–urkti: the bear might take the word for an invitation and come, and this is something no one wanted. Tales of bears abducting maidens, of bears seeking “compensation” for a wound, of bears’ sons, and so forth are known all over Eurasia. Therefore, as a safety measure, in the Germanic-speaking world the name was changed. Quite possibly, both bear and björn, assuming that they are related, mean “brown.” Now humans could talk of the brown one, and the bear got no inkling of the topic. On the other hand, calling a boy Björn guaranteed the boy’s strength and invincibility. Being Bjornson was also nice. The Slavs renamed the beast “honey-eater.” Not a bad idea either.

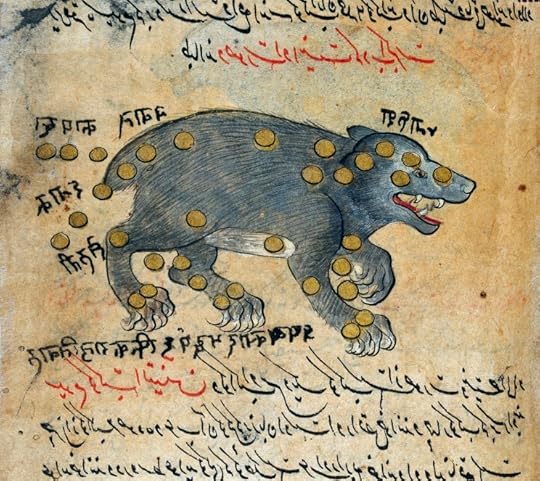

The Great Bear without disguise

The Great Bear without disguiseWhat is true of the bear is also true of the wolf. The word may have meant “tearer.” At one time, anthropologists and linguists were fond of using the term noa, which means “a word devoid of magic.” It carries the same connotations as taboo: once the real name has been replaced with a harmless synonym, it loses its force and stops posing danger. Today that term hardly ever occurs in linguistic works. Taboo has played an outstanding role not only in naming (or rather renaming) animals famous for their ferocity but also snakes, toads, mice, and rats, among others. Every now and then, rather than coining an innocuous replacement, people would deliberately garble the word by transposing sounds in it. The more ingenuity they showed in disguising the original term, the less hope we have to ferret out its etymology, and, even when we may hit the nail on the head, there is no certainty that we hit the right nail and precisely on the head.

In comparative studies, researchers face several situations. Here is one case. If bear does mean “brown,” we have some support for the adjective outside Germanic, though the look-alikes in Romance and Lithuanian (French brun, Italian bruno, and Lithuanian brúnas) are loans from Germanic and thus do not count. However, Sanskrit babhrús “reddish-brown” is a good match, and so is Greek phrúnē, though phrúnē means “toad” (familiar to many from Phryne, the nickname of the much admired courtesan). Consequently, the step from an animal name to a color name gains in verisimilitude. (Incidentally, beaver also means “brown.) But sometimes an animal name has no obvious cognates. Fox probably does have them, even though they are disputable. Be that as it may, no non-Germanic animal sounds like fox. Then we begin to cast about for a possible taboo substitute. Immediately the idea turns up that fox means “sly” or “treacherous.”

It is not quite clear how the fox has become the embodiment of cunning and deceit. Because of its long tail? Or did it acquire this feature by default? Bears and wolves are prone to attack humans, while the fox, though a predator, is secretive and avoids contact with humans, except as a pest. A secretive creature must have something to conceal and do it cleverly. The European tradition of the shifty fox goes back to Aesop, in whose fables we already find the familiar stratification of the animal kingdom, with the lion at the top. Most of us have learned about the fox’s tricks from children’s versions of folk tales, but they seem to be the product of book tradition. Presumably, Aesop had his plots from folklore, then they became part of book culture, and “returned to the people.” This is a common process. For example, the chronicle of the Danish historian Saxo was at least partly based on oral sources. He was the first to tell a crude version of Hamlet’s feigned madness and revenge. Shakespeare took this plot from an English translation of Saxo. Later a version of the tragedy was recorded as a French folk tale. The story came full circle.

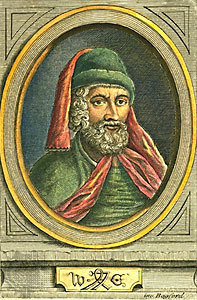

William Caxton, an admirer of Reyneke

William Caxton, an admirer of ReynekeThis is what also happened to the fox. In the Middle Ages the beast was made famous by the book of Reynard, or Reineke. It is a long poem, extant in Middle Dutch, Old French, and Middle Low (= northern) German. Germans enjoy Goethe’s retelling of it. In English, the version told by Caxton (1481, but published four centuries later) is available. Caxton, who was the first to introduce printing to England, learned Dutch in the Netherlands and must have enjoyed the poem, which is indeed a delight. The protagonist appears as a cruel, brilliantly resourceful feudal lord and a trickster, perhaps even the queen’s (the lioness’s) paramour. He lives in a castle, not in a hole, and brings up his cubs in the true spirit of perfidy. Yet in search of a possible taboo word, one would seek in vain for an adjective or noun meaning “sly” and resembling fox. Old Icelandic fox “deceit” exists, but it is a borrowing of Old Engl. fox “fox.” If fox is a “noa word,” it does not mean “sly,” for (strangely!) Old Engl. fox “deceit” has not been recorded. The Scandinavian word for fox is refr, and Refr is a common name of a crook in the sagas.

Still another scenario in dealing with animal names will be discussed next week. But before I finish this post, perhaps something has to be said about the relation between the words fox and vixen. The German pair is fully transparent: Fuchs and Füchsin. Although their analogs existed in Old English, English has lost umlauted vowels, so that the counterpart of Füchsin must have yielded fixen, and this is indeed what happened. But a few words in the modern language reached the so-called Standard in their Kentish form, with initial f- voiced (compare also Dutch vos “fox”). To this process we owe v– in vixen, van, and vat. Phonetic change has severed the tie between fox and vixen to such an extent that students are usually surprised when they hear that vixen and fox belong together, obvious as the connection between them may be. Words tend to live up to their etymology. It would be odd if the fox had not concealed the form of the name designating its loyal mate. About the loyalty of Reineke’s wife we learn from the poem. She constantly predicts that her husband will be hanged, and this is what would have happened if Reineke were not so much smarter than everybody else at court. They needed him, and the scoundrel went scot-free. Customs in the corridors of power never change.

Reynard and one of the victims he duped

Reynard and one of the victims he dupedImage credits: (1) Constellations of Ursa Major, detail, from Persian Manuscript 373. Asian Collection. Wellcome Images, MS PERSIAN 373, L0030691. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) William Caxton, English etching, 1816. The Granger Collection, New York. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Gorleston Psalter, 1310s, British Library Add Ms. 49622. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post appeared first on OUPblog.

Why golf balls side slip just like aircrafts

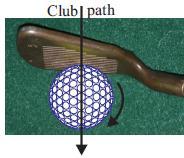

Golf balls curve in flight for one principal reason: Namely that the golf club face is not square to the path being followed by the club head as it impacts the ball. This is illustrated in the figure where the club face is “open” to the club path by about four degrees. This is sufficient to produce a significant slice to the right. The club face dictates about 75% of the initial launch direction, so the ball will start out three degrees to the right and then curve away further during its flight. It can easily be appreciated that the sideways angled club face will, with the slightly glancing blow, impart a side spin to the ball — as shown by the counter-clockwise arrow. At the same time, the loft of the club produces a large backspin. Of course these cannot be two separate spins. If the loft angle is 30 degrees, then we can imagine that the ball starts turning on the face in a direction that gives the ratio of four degrees of sideways turn to 30 degrees of backwards turn; that is, it turns in an angled direction up the face. This tilts the axis of spin of the ball.

This illustration was created by Peter Dewhurst and has been used with permission.

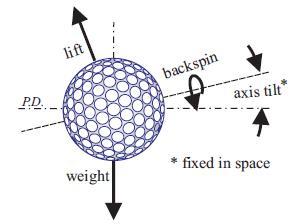

This illustration was created by Peter Dewhurst and has been used with permission.The next illustration is of a ball flying into the page, which has been struck with a club angled the opposite way with respect to the club path; i.e. the face was closed. The tilted spin axis causes the lifting force resulting from the back spin, to tilt by the same amount. This picture of the ball remains unchanged throughout the flight; that is, it keeps moving and facing forwards while the angled lift force pulls it sideways. It does this according to the principle of gyroscopic stability — just like the horizontally spinning rotors behind aircraft instruments panels fix the unchanged horizon as the plane banks.

This illustration was created by Peter Dewhurst and has been used with permission.

This illustration was created by Peter Dewhurst and has been used with permission.In an aircraft, we get exactly the same flight conditions by applying left ailerons and just enough opposite rudder to keep the craft pointing forwards. We might do that to slip sideways to a runway over to the left, while losing altitude quickly with the high sideways drag. When aligned with the runway, returning the ailerons and rudder to the neutral position will straighten the plane up for landing. Unfortunately, golf balls with an internal control system are not yet available! So too often we watch helplessly as the ball continues to slip sideways past the grass landing strip to a crash site deep in the woods or the water.

Avoiding slices and hooks in the modern game is extremely difficult. Fredrick Tuxen, the inventor of the Trackman radar ball monitoring system, estimated empirically that for the driver, a golf ball with a five degree spin axis tilt will move 4.5 yards sideways for each 100 yards of travel. In my own research, I was able to determine from the impact mechanics that a five degree tilt is produced when the ratio of the face angle to the club loft angle is approximately 1/10. So a drive of 200 yards using a ten degree lofted driver, with the face just one degree open or closed, will give approximately 2 x 4.5 = 9 yards of slice or hook. Using, say, a 6-iron with 30 degrees of loft, two beneficial changes occur. The first is that, all things being the same, aerodynamic modeling showed that grooved clubs produce slightly less sideways movement because the higher spin rates increase drag, and so reduce both speed and lifting force more quickly – the “normalized” side movement becomes nearer to 3.5 yards. One degree of open or closed face with a six iron gives a side angle to loft ratio of 1/30, and so produces one third of the ball axis tilt compared to the driver. A 150 yard shot in this case would give 3.5/3 yards for each 100 yards, and so just under two yards sideways for the shot. The main lesson here with regard to equipment is that loft is the golfers friend, particularly with the driver. Tour players resort to hitting fairway woods into tight landing areas precisely because the extra loft improves directional control.

Because driver heads extend behind the shaft, the shaft is actually bent forward at impact, which further increases loft. The average loft at impact of PGA Tour pros is 14.4 degrees, resulting from about five degrees of forward shaft bending. From the above calculation, we can estimate that for their average flight distance of 269 yards a one degree open or closed face will put the ball 8.4 yards sideways from the launch direction. Compare this to a typical PGA fairway width of 30 yards and we conclude that while swinging with an average club speed of 112 mph, they must keep the face square to within about plus or minus three degrees to stay on the flat stuff.

Featured image credit: A hot headed golfer taking a tee shot to begin a round of golf by Lilrizz. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why golf balls side slip just like aircrafts appeared first on OUPblog.

African studies: a reading list

African Studies focuses on the rich culture, history and society of the continent, however the growing economies of African countries have become an increasingly significant topic in Economic literature. This month, The Centre for the Study of African Economies annual conference is taking place in Oxford. To raise further awareness of the growing importance of the study of African economics, we have created this reading list of books, journals, and online resources that explore the varied areas of Africa and its economy.

Made in Africa by Arkebe Oqubay

Made in Africa presents the findings of original field research into the design, practice, and varied outcomes of industrial policy in the cement, leather and leather products, and floriculture sectors in Ethiopia. It explores how and why the outcomes of industrial policy are shaped by particular factors in these industries.

The Oxford Handbook of Africa and Economics: Volume 1: Context and Concepts edited by Célestin Monga and Justin Yifu Lin

This handbook opens up the diverse acuity of commentary on exciting topics, and in the process challenges and stimulates the quest for knowledge. Wide-ranging in its scope, themes, language, and approaches, this volume explores, examines, and assesses economic thinking on Africa, and Africa’s contribution to the discipline. Read a free chapter from Oxford Handbooks Online.

The Oxford Handbook of Africa and Economics: Volume 2: Policies and Practices edited by Célestin Monga and Justin Yifu Lin

This volume aims at reassessing the economic policies and practices observed across the continent since independence. It offers a collection of analyses by some of the leading economists and development thinkers of our time, and reflects a wide range of perspectives and viewpoints—even on the same topic. Read a free chapter from Oxford Handbooks Online.

Nelson Mandela: A Very Short Introduction by Elleke Boehmer

As well as being a remarkable statesman and one of the world’s longest-detained political prisoners, Nelson Mandela has become an exemplary figure of non-racialism and democracy, a moral giant. Set within a biographical frame, this Very Short Introduction explores the reasons why his story is so important to us in the world at large today, and what his achievements signify. Read a free chapter from Very Short Introductions Online.

Capital Flight from Africa, Causes, Effects, and Policy Issues edited by S. Ibi Ajayi and Léonce Ndikumana

A comprehensive thematic analysis of capital flight from Africa, it covers the role of safe havens, offshore financial centres, and banking secrecy in facilitating illicit financial flows and provides rich insights to policy makers interested in designing strategies to address the problems of capital flight and illicit financial flows. Read a free chapter from Oxford Scholarship Online.

Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction in Sub-Saharan Africa, Current and Emerging Issues edited by Andrew McKay and Erik Thorbecke

This volume discusses long-standing, but central, economic issues in Sub-Saharan Africa, including the nature of growth-poverty-inequality relations, agriculture, the labour market and openness, and globalization. Read a free chapter from Oxford Scholarship Online.

The Journal of African Economies

In advance of the CSAE 2016 conference plenary session on 25 years of the Journal of African Economies, revisit some of the best it has to offer in this special 25th anniversary collection, featuring articles on conflict, education, aid ‘dependency’, and more.

African History: A Very Short Introduction by John Parker and Richard Rathbone

African History: A Very Short Introduction by John Parker and Richard Rathbone

Essential reading for anyone interested in the African continent and the diversity of human history, this Very Short Introduction looks at Africa’s past and reflects on the changing ways it has been imagined and represented. Key themes in current thinking about Africa’s history are illustrated with a range of fascinating historical examples, drawn from over 5 millennia across this vast continent. Read a free chapter from Very Short Introductions Online.

African Affairs

African Affairs has collected some of the most insightful and influential articles that it has published on Africa’s International Relations and made them free to download as part of a virtual issue. The virtual issue also features an exclusive online-only introduction by the journal’s newest Co-Editor, Dr. Carl Death.

Featured image credit: Serengeti sunrise by Yoni Lerner. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post African studies: a reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

March 15, 2016

Our lost faith in the American murder trial

We live in an age when Americans are both captivated and disturbed by murder trials. The Netflix smash hit Making a Murderer went viral in late December as it chronicled the seemingly wrongful convictions of a Wisconsin man and his teenage nephew for the gruesome killing of a young photographer. The success of this documentary was hardly surprising in the wake of 2014’s Serial, the most popular podcast in history and winner of a Peabody Award. Millions listened intently to the story of a Baltimore youth who, despite significant cause for reasonable doubt, received a life sentence for the murder of his high school ex-girlfriend. The case of Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old Floridian armed only with a pack of skittles, needed no documentary or podcast to become national news. The acquittal of his killer sparked predictable public outrage. And, of course, the steady succession of deaths of African-Americans at the hands of police has led to numerous grand juries–if not always full-fledged trials–that garner headlines across the country. Americans are asking tough questions about the integrity of the police, detectives, and prosecutors involved in these trials. When considered in tandem, there seems to be something deeply amiss with the criminal justice system.

In fact, the country has exhibited these kinds of doubts before. The Dukes-Nutt affair illustrates in vivid terms our long history of disaffection from the institution of the jury trial. In the 1880s, two political figures in Pennsylvania, Nicholas Dukes and Adam Nutt, engaged in a lethal affray after Dukes confessed to seducing Nutt’s daughter. Such were her charms, Dukes insisted, she “would disarm the devil himself.” On a fateful Christmas Eve, Nutt was slain and Dukes indicted for murder. The national press castigated Dukes for his double sin of seduction and homicide. A vengeful nation waited for a jury to condemn him to the gallows. But when twelve of the defendant’s peers unexpectedly set Dukes free, the public reacted with hysteria. He fled from lynch mobs led by clergymen, attorneys, and newspaper editors. At a gathering of bloodthirsty citizens, one member of the bar declared that “the courts of law are inadequate to mete out justice,” adding, “we will be driven to take other measures.”

The Fayette County Courthouse where Dukes stood trial. Source: Franklin Ellis, A History of Fayette County, Pennsylvania: With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men (Philadelphia: Everts, 1882), 134a.

The Fayette County Courthouse where Dukes stood trial. Source: Franklin Ellis, A History of Fayette County, Pennsylvania: With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men (Philadelphia: Everts, 1882), 134a.In a world that had lost faith in the jury trial system, Nutt’s eldest son, James, had good reason to believe that the country would celebrate any attempts at vigilante justice. Two months following Dukes’ acquittal, James lodged a fatal bullet in the heart of Adam Nutt’s killer. Overnight, James became a national hero, a symbol of justice that the law had failed to provide.

The persistence throughout history of public doubts about the justice system suggests that something perennial may be at play in our current moment of distrust: the flaws inherent to human nature. That is not to suggest that we be complacent in the face of police brutality or corrupt prosecutors. But the jury trial is a human institution, and as such, it has always embodied our shortcomings. Indeed, many longstanding rules of evidence for trials are concessions to the defects of human nature. The so-called “character rule” prohibits the prosecution from admitting evidence of a defendant’s poor character because of the strong instinct among jurors to punish people who seem generally immoral even when evidence of the specific crime in question may be lacking. Recognition of human bias also gave rise to a rule that parties must submit physical evidence in court only if that evidence is connected to witness testimony. It is our nature to reflexively attach legitimacy to objects–the raw physicality of the evidence tends to trump our deliberative faculties.

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” James Madison famously wrote. In the Constitutional Convention, Madison aimed to design a government that would serve as a check on the worst tendencies of human nature. But even as the jury trial seeks to counterbalance our human failings, still, it inescapably reflects them.

Image credit: James Nutt guns down Nicholas Dukes. Source: The National Police Gazette: New York, June 30, 1883, 9. (Both images courtesy of the author)

The post Our lost faith in the American murder trial appeared first on OUPblog.

How does chemistry shape evolution?

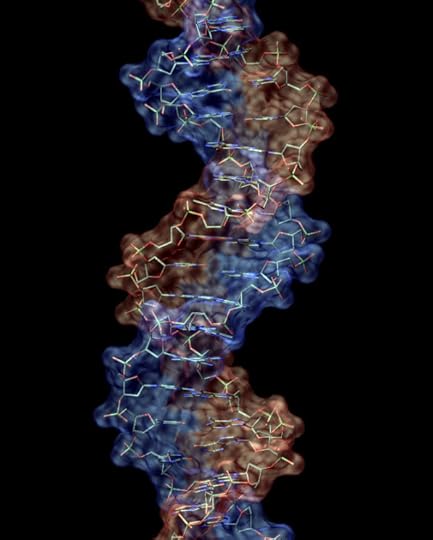

When people think of evolution, many reflect on the concept as an operation filled with endless random possibilities–a process that arrives at advantageous traits by chance. But is the course of evolution actually random? In A World from Dust: How the Periodic Table Shaped Life, Ben McFarland argues that an understanding of chemistry can both explain and predict the course of evolution. To understand what he means, we’ve created this slideshow to uncover how the rules of chemistry have influenced many of life’s fundamental processes, and in turn, the course of evolution.

Why chemistry is important when studying evolution

“All life, from a lakewater bacterium to the neurons firing in your brain as you read this, is hemmed in. It is free to randomly adapt to its surroundings with nearly infinite creativity, but its overall path is as constrained as if it were walking on the deck of a ship crossing the ocean. The ultimate movement, on the scale of billions of years, is shaped by chemical rules.” –Ben McFarland, A World from Dust.

Image Credit: Fishing boat, Public Domain via Takeopix.

Determining which elements play an important role in our lives

“A molecule needs three characteristics to be useful for building life’s structures:

1.) It must be available in water.

2.) It must have a fitting shape and charge for its purpose.

3.) Its bonds should last as long as they need to (and no longer).”

–Ben McFarland, A World from Dust.

Image Credit: Waves in water by bykst. CC0 via Pixabay.

Phosphorus

Phosphorus is the perfect chaining element in our cells because of its ability to establish medium-strength bonds with negatively charged oxygen atoms in water. These bonds allow phosphorus to complete the following functions in our cells:

• Phosphorus is used in the form of phosphate as a “signal molecule”—sending messages through its bonds such as the need for proteins to be made from DNA.

• Phosphorus is used in energy transfer, most importantly through the energy released to muscles by breaking the bonds of the phosphate group ATP.

• Phosphorus is used in maintaining the structure of DNA. Phosphate is an important component of DNA’s double helix backbone because each phosphate in the chain has a negative charge—thus keeping the DNA chain spread out and inhibiting it from tangling.

Image Credit: Red Phosphorus Powder by Hi-Res Images of Chemical Elements. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

But elements don't act on their own, they react with each other

“Chemistry is the study of pairings.” –Ben McFarland, A World from Dust.

Image Credit: Beakers by usehung. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Magnesium

Because of phosphorus’ prevalence within cells, magnesium’s positively charged bonds play a crucial role in balancing the negative charge of the bonds formed with phosphorus—thus balancing and neutralizing the net charge within our cells.

Image Credit: Magnesium crystals produced via the Pidgeon process by Warut Roonguthai. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

CHON: Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen, and Nitrogen

96% of your body weight is made up of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, because proteins and DNA are mostly made up of these four elements. As such, these four elements are often referred to as the building blocks of life.

Questions, questions, questions…

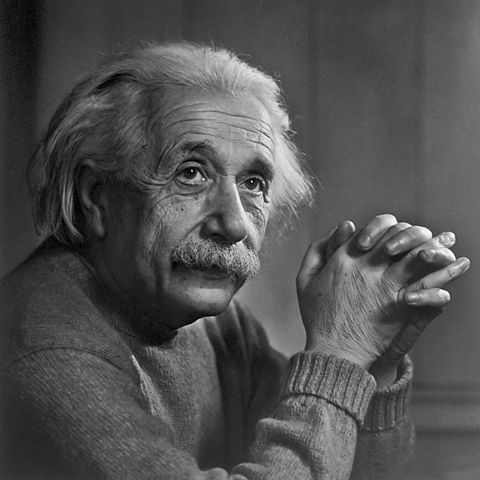

Einstein has had a good month, all things considered. His century-old prediction, that the very fabric of space and time can support waves travelling at light-speed, was confirmed by the LIGO collaboration. More, the bizarre and horrifying consequences of his theory of gravity, the singularly-collapsed stars that came to be called ‘black holes’, have been directly detected for the first time. As is now widely known (but how could anyone actually conceptualise the monstrous event?), it was the mutual circling and merger of two black holes that set the gravitational ripples on their billion light-year journey across the ocean of space towards the shores of our solar system.

The events have reminded us of the powerful sense of inspiration that comes from contemplating any of Einstein’s scientific achievements. He showed how to interpret the ‘Brownian motion’ of particulate matter as a conceptual window into the molecular world, once it is understood as the random buffeting of tiny but visible particles from invisible molecules. He re-imagined light as a gas of massless particles, and in doing so opened up a path to the quantum world of the atom. He day-dreamed as a teenager about trying to catch a light-beam, a journey of the mind that led him to the universal constant of the speed of light, and to the mutual, relativistic, inter-conversion of space and time. And of course, he wondered if gravity might better be thought of, not as a force, but as a sort of curvature in the warp and weft of space and time.

What glories indeed! But surprisingly, he never thought of himself as particularly gifted. Rather he would attribute his success to the prioritisation of the question rather than the answer. ‘The important thing is not to stop questioning’ was a frequent admonition in one form or another. A long form of this urging of careful question-crafting attributed to him goes something like this:

‘If I had an hour to solve a problem and my life depended on the solution, I would spend the first 55 minutes determining the proper question to ask… for once I know the proper question, I could solve the problem in less than five minutes.’

‘What would I see if I caught up with light?’

‘Why can’t I tell the difference between being accelerated and being pulled on by gravity?’

‘What is the source of the jiggling motion of tiny dust motes suspended in water?’

‘How can I think of light in the same way I think of matter?’

Image credit: Albert Einstein (portret), by Anefo. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: Albert Einstein (portret), by Anefo. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.These are the questions that lead to the greatest scientific discoveries of the last century. The centrality of the creative question is true at any level of scientific endeavour. I find myself explaining to new PhD students that, although they have got to this point by proving themselves uncommonly adept and finding the right answers, this will be of little use to them now. They need to learn instead to craft the fruitful question. That is the central imaginative, creative act of science.

Perhaps that is why I have always been entranced by the ancient long-poem of Natural Wisdom found in the Biblical Book of Job. It is usually called ‘The Lord’s Answer’, for it is the long-awaited response of Yahweh to the angry Job’s railings that he is suffering unjustly, and that the world is consequently out of joint. But the use of the word ‘answer’ is in every other way an inappropriate description of the speech. It takes the form of a list of questions, posed to the hapless Job, but directed outwards into the manifold mysteries of the natural world. Here are just a few of the 160 questions or so:

Who cuts a channel for the torrent of rain, a path for the thunderbolt?

Where is the realm where heat is created, which the sirocco spreads across the earth?

Can you bind the cluster of the Pleiades, or loose Orion’s belt?

Can you send lightning bolts on their way, and have them report to you, ‘Ready!’?

Is it by your understanding that the hawk takes flight, and spreads its wings toward the south?

A poem, with each verse a question, each trope probing its own domain of creation: the winds and weather, the sky and stars, the animal world. They are highly potent questions – the containment of flood and lightening is asking about the balance of chaos and order. The binding of the Pleiades (a tight star-cluster of associated young stars much closer than those of Orion) is motivated by curiosity, aroused by observation. There is indeed a reason that they are closely-grouped. The pattern of avian navigation holds puzzles for us still, although we know that birds also can register patterns in the stars. I have often suggested to scientist colleagues that they read through the Lords’ Answer to Job. Uniformly they respond with recognition that here lies a fundamental human motivation to look deeply into nature that we also share.

The fact that we would have been called ‘natural philosophers’ two centuries ago, rather than ‘scientists’, is a clue that the story of science begins in the ancient thought-world of ‘wisdom.’ Certainly one of its most luminous themes – the celebration of the creative question – has not dimmed. Einstein would have approved, but can we, in turn, succeed in passing on the love of the question, including the unanswered question, to our children?

Featured image credit: The Pleiades Star Cluster by WikiImages. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Questions, questions, questions… appeared first on OUPblog.

Digging into the origins of 20th-century American tap dance

To be a tap historian is to be a sleuth. It is to revel, after days of painstaking research, in newly-found bits of information as if they were nuggets of gold. At the New York State Library in Albany, New York, I found the premiere date for Darktown Follies of 1914 (3 November 1913, Lafayette Theater), a date that had eluded tap historians for many years. At the State University of New York Library, where I viewed microfilms of the weekly issues of ten years’ worth of the Amsterdam News, I reconstructed a roster of tap dance acts that played the Harlem Opera House, Lafayette Theater, and Apollo Theater in the 1930s. At the Museum of Television and Radio in New York City (where I muffled laughter while watching reruns of The Jackie Gleason Show, with the June Taylor Dancers), I located the television specials in which John Bubbles, the “Father of Rhythm Tap,” had appeared. The New York Public Library and its staff, especially the newly created Gregory Hines Collection of American Tap Dance and the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture, were indispensible to my visual research.

Errol Hill, the renowned black theater historian and Caribbean scholar, and my uncle by marriage, first presented me with the plausibility of Afro-Irish fusions in tap dance by introducing me to Joseph Williams’s book Whence the Black Irish of Jamaica? (1932) and John Messenger’s 1975 article “Montseurrat: The Most Distinctly Irish Settlement in the New World.” Catherine Foley, in her archive of Irish Dance at the University of Limerick, Ireland, and the Irish dance historian John Cullinane, in his archive at the University of Cork, Ireland, offered me a galaxy of visual sources on the southern (Munster) style of Irish step dancing. The Lindy Hop historian Terry Monahan travelled with me to the Connemara region in Ireland to investigate the lesser-known sean nos (Old Style) step dancing, and continually connect me to the Irish roots of tap dance. The librarians in the Oak Bluffs Library, in Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts, offered me a rainbow of materials on the Irish in America.

I do not know what drove me to devote thousands of hours, ten years of my life, to digging into archives, squinting through microfiche, compiling lists, organizing materials, and coming to the sober realization that doing the work meant resigning to be alone, surrendering to silence, and dwelling in darkness. When I looked through the final installation of Tap Dance in America: A Twentieth-Century Chronology of Tap Performance on Stage, Film, and Media before its public release by the Music Division at the Library of Congress, I began to question my sanity.

What drove me to write a 20,000-word “Short History of Tap Dance,” compile 2800 performance records, and write 180 biographies of twentieth-century tap dancers? Was it growing up in the house of my grandparents in Astoria, Queens and learning early on that hard work would be the only means to survive in this world? Was it the ballet and tap dance classes my parents enrolled me in at age three to ensure I would speak English when enrolled in kindergarten? Whether it was to please my grandparents or to reassure my parents that I would do them proud, I remember always being an over-achiever; a friend calls mine an obsessive-compulsive disorder, characterized by uncontrollable, repetitive, ritualized behaviors you feel compelled to perform.

As a second-generation Greek-American girl born in the American tumult of the 1960s, and having “come of age” in the decade of the 1970s, immersed in the Anti-Vietnam War, Black Power, and Women’s Liberation movements, I felt a strong affinity with tap’s artistic tradition that could never be separated from its long history of hardship–from slavery to blackface minstrelsy, and to the favoring of the western canon of European traditions over the improvisatory African-American forms. An even more compelling reason to my attraction to tap dance was its rhythmic brilliance, musicality, eloquent footwork, and full-bodied expressiveness that made for the most sophisticated refinement of jazz as a percussive dance form.

It was not until 1970 that I returned to dance when, after graduating from University of Massachusetts with a Master’s degree in Rhetoric and Public Address, I moved to New York and found myself at the Alvin Ailey School of American Dance. On a dance scholarship, I studied ballet and modern dance, but gravitated to jazz dance. After studying with various members of the Copasetics, especially Charles “Cookie” Cook, and with Gregory Hines at the first By Word of Foot tap festival in 1980, I was transformed into a jazz tap dancer. I spent the next 20 years teaching, choreographing, performing, and writing about tap dance.

After earning a Ph.D. in Performance Studies from New York University, Hampshire College, in Amherst, Massachusetts, welcomed me in the fall of 2000 as a Visiting Five College Professor of Dance. They lauded my first book, Brotherhood in Rhythm: The Jazz Tap Dancing of the Nicholas Brothers and then proceeded to endow me with myriad forms of support for what I audaciously announced would me my magnum opus—a twentieth-century chronology and cultural history of tap dance in America. The book could not be written so quickly, as the nitty-gritty who-where-when-how of tap history had not been documented. There had been star-centered narratives of tap dance but no historiographies of detail and substance that would trace the arc of tap performance through the decades. Stephanie Willen Brown, the database librarian at Johnson Library at Hampshire College, designed a database that would comprise a chronology of tap dance in print and performance, film and video, festival and social history. I knew that to compile a chronology of twentieth-century tap performance, I needed to inclusive of the cultures rooted in modern tap dance, spanning African, Irish, Latin American, African American, and Afro-Caribbean dance forms and traditions, as well as women’s contributions. And so I consulted with the following personages and source materials that were absorbed into the Tap Chronology.

By 2005, I began to see how the database could serve as the basis upon which to write Tap Dancing America: A Cultural History. I began to see trends in venues for tap dance through the decades. For instance, the decade of the thirties had live stage performances of tap in Harlem, and a plethora of tap performances in Hollywood films. In the decade of the fifties, when tap dance declined in popularity on stage, the trend shifted to television. I continued to gather dozens of dance reviews and features I had written as a dance critic and transcribed dozens of interviews with tap dancers–one of the earliest, a 1991 telephone interview with Charles “Honi” Coles and Marion Coles. These led to biographies of tap dancers complete with birth and death dates and representational performances, with description of the rhythmic aesthetic of each tap dance artist. Women’s contributions include such tap soloists as Lotta (Mignon) Crabtree, Ada Overton Walker, Cora LaRedd, Eleanor Powell, Jeni LaGon, Brenda Bufalino, Dianne Walker, and the rising number of high-and-low-heeled tap dancers who have contributed to making tap the most cutting-edge dance form on the national and international stage.

Tap dance is invisible in the scholarly canon because it continues to be characterized as a constantly-dying art form. Its sporadic uprising in popularity over the decades has come on the wings of nostalgia, with shows such as the 1971 revival of the 1925 musical No, No Nanette, directed by Busby Berkeley starring Ruby Keeler, and the spring 2016 revival of the 1921 musical Shuffle Along, directed by George C. Wolfe and choreographed by Savion Glover. Tap Dance in America: A Twentieth- Century Chronology of Tap Dance Performance on Stage, Screen, and Media should aid in countering tap’s invisibility, and perhaps enlighten critics to the fact that tap dance it is alive and thriving, and continues to be the most cutting-edge dance form on the American stage, and most deserving of scholarly attention.

Featured image: “Tappity tap” by Abulic Monkey. CC 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Digging into the origins of 20th-century American tap dance appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers