Oxford University Press's Blog, page 536

March 12, 2016

The consistency of inconsistency claims

A theory is inconsistent if we can prove a contradiction using basic logic and the principles of that theory. Consistency is a much weaker condition that truth: if a theory T is true, then T consistent, since a true theory only allows us to prove true claims, and contradictions are not true. There are, however, infinitely many different consistent theories that we can construct using, for example, the language of basic arithmetic, and many of these are false. That is, they do not accurately describe the world, but are consistent nonetheless (one way of understanding such theories is that they truly describe some structure similar to, but distinct from, the standard natural number structure).

In 1931 Kurt Gödel published one of the most important and most celebrated results in 20th century mathematics: the incompleteness of arithmetic. Gödel’s work, however, actually contains two distinct incompleteness theorems. The first can be stated a bit loosely as follows:

First Incompleteness Theorem: If T is a consistent, sufficiently strong, recursively axiomatizable theory, then there is a sentence “P” in the language of arithmetic such that neither “P” nor “not: P” is provable in T.

A few terminological points: To say that a theory is recursively axiomatizable means, again loosely put, that there is an algorithm that allows us to decide, of any statement in the language, whether it is an axiom of the theory or not. Explicating what, exactly, is meant by saying a theory is sufficiently strong is a bit trickier, but it suffices for our purposes to note that a theory is sufficiently strong if it is at least as strong as standard theories of arithmetic, and by noting further that this isn’t actually very strong at all: the vast majority of mathematical and scientific theories studied in standard undergraduate courses are sufficiently strong in this sense. Thus, we can understand Gödel’s first incompleteness theorem as placing a limitation on how ‘good’ a scientific or mathematical theory T in a language L can be: if T is consistent, and if T is sufficiently strong, then there is a sentence S in language L such that T does not prove that S is true, but it also doesn’t prove that S is false.

The first incompleteness theorem has received a lot of attention in the philosophical and mathematical literature, appearing in arguments purporting to show that human minds are not equivalent to computers, or that mathematical truth is somehow ineffable, and the theorem has even been claimed as evidence that God exists. But here I want to draw attention to a less well-known, and very weird, consequence of Gödel’s other result, the second incompleteness theorem.

First, a final bit of terminology. Given any theory T, we will represent the claim that T is consistent as “Con(T)”. It is worth emphasizing that, if T is a theory expressed in language L, and T is sufficiently strong in the sense discussed above, then “Con(T)” is a sentence in the language L (for the cognoscenti: “Con(T)” is a very complex statement of arithmetic that is equivalent to the claim that T is consistent)! Now, Gödel’s second incompleteness theorem, loosely put, is as follows:

Second Incompleteness Theorem: If T is a consistent, sufficiently strong, recursively axiomatizable theory, then T does not prove “Con(T)”.

For our purposes, it will be easier to use an equivalent, but somewhat differently formulated, version of the theorem:

Second Incompleteness Theorem: If T is a consistent, sufficiently strong, recursively axiomatizable theory, then the theory:

T + not: Con(T)

is consistent.

In other words, if T is a consistent, sufficiently strong theory, then the theory that says everything that T says, but also includes the (false) claim that T is inconsistent is nevertheless consistent (although obviously not true!) It is important to note in what follows that the second incompleteness theorem does not guarantee that a consistent theory T does not prove “not: Con(T)”. In fact, as we shall see, some consistent (but false) theories allow us to prove that they are not consistent even though they are!

Portrait of Kurt Gödel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Kurt Gödel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.We are now (finally!) in a position to state the main result of this post:

Theorem: There exists a consistent theory T such that:

T + Con(T)

is inconsistent, yet:

T + not: Con(T)

is consistent.

In other words, there is a consistent theory T such that adding the true claim “T is consistent” to T results in a contradiction, yet adding the false claim “T is inconsistent” to T results in a (false but) consistent theory.

Here is the proof: Let T1 be any consistent, sufficiently strong theory (e.g. Peano arithmetic). So, by Gödel’s second incompleteness theorem:

T2 = T1 + not: Con(T1)

is a consistent theory. Hence “Con(T2)” is true. Now, consider the following theories:

(i) T2 + not: Con(T2)

(ii) T2 + Con(T2)

Since, as we have already seen, T2 is consistent, it follows, again, by the second incompleteness theorem, that the first theory:

T2 + not: Con(T2)

is consistent. But now consider the second theory (ii). This theory includes the claim that T2 does not prove a contradiction – that is, it contains “Con(T2)”. But it also contains every claim that T2 contains. And T2 contains the claim that T1 does prove a contradiction – that is, it contains “not: Con(T1)”. But if T1 proves a contradiction, then T2 proves a contradiction (since everything contained in T1 is also contained in T2). Further, any sufficiently strong theory is strong enough to show this, and hence, T2 proves “not: Con(T2)”. Thus, the second theory:

T2 + Con(T2)

is inconsistent, since it proves both “Con(T2)” and “not: Con(T2)”. QED.

Thus, there exist consistent theories, such as T2 above, such that adding the (true) claim that that theory is consistent to that theory results in inconsistency, while adding the (false) claim that the theory is inconsistent results in a consistent theory. It is worth noting that part of the trick is that the theory T2 we used in the proof is itself consistent but not true.

This, in turn, suggests the following: in some situations, when faced with a theory T where we believe T to be consistent, but where we are unsure as to whether T is true, it might be safer to add “not: Con(T)” to T than it is to add “Con(T)” to T. Given that the majority of our scientific theories are likely to be consistent, but many will turn out to be false as they are overturned by newer, better, theories, this then suggests that sometimes we might be better off believing that our scientific theories are inconsistent than believing that they are consistent (if we take a stand on their consistency at all). But how can this be right?

Featured image credit: Random mathematical formulæ illustrating the field of pure mathematics. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The consistency of inconsistency claims appeared first on OUPblog.

A conversation with a widow’s nervous system

My late husband Gene Cohen is known as one of the founders of both geriatric psychiatry and the creative aging movement. He was always talking, writing, and educating about brain plasticity and the changes that took place as we age into our wisdom and creative potential. In the years since he passed away in 2009, it is as if the awakening he predicted for all of us baby boomers has just exploded into consciousness. I have watched it happen gradually and then pick up speed over just this past number of years.

At first, as a widow at 59—fairly young as widows go—I felt isolated and alone in my experience, as if I were now an outsider to life. It was so hard to bring up the topic of my loss, to be present with people as I was wrapped in my own blanket of grief. It was a real conversation stopper. Suddenly now, we read about aging everywhere: How to exercise our aging brains with games or eat the right foods and think the right thoughts for longevity and brain fitness, or how aging opens us to the existential quest for meaning in both life and death. A multitude of voices now speak (and write) not only on aging, but on illness, grief, death and dying. These conversations are not only taking place in books but also in blogs, personal essays, opinion pieces on end-of-life issues and quality-of-life issues, and in media stories about the many new ways that people are finding to talk about their experience. From potluck dinners to book clubs, more people are daring to broach the subject in a conscious and more thoughtful way than ever possible before.

It is a conversation of existential inquiry. It is the voice of grief. It is the voice of identity reevaluation. It was verboten and now is condoned or allowed. Whoever would have thought that an experience as painful and isolating as loss would move from the outer edges of the psychic hinterlands into the forefront of a trending conversation? Has it?

What kind of experience have you had where you have observed over time how your own identity changes; yet it is also right in front of your eyes?

Does your experience include a confrontation with illness, aging or dying?

How do we take care of ourselves inside these major life transitions?

It’s hard for me to remember time in those first few years after Gene died. I know that the simplest tasks were gigantic. The multiple steps of a decision seemed to clack into one another before any movement occurred and I remained flooded by thoughts, papers, unmade phone calls, words floating by, thoughts all askew. I remember reading through a book on meditations after the death of a loved one called A Time to Grieve by Carol Staudacher and one of the pages had a quote by Boris Pasternak that said: “Our nervous system isn’t just a fiction; it is part of our physical body and our soul … it’s inside us like the teeth in our mouth.”

Rose at cemetery by womich. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Rose at cemetery by womich. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.The teeth of my nervous system were seriously chattering as neither illness nor deaths are changes that come upon us through choice. They are forced on us as if an earthquake has opened the ground upon which we live.

That was certainly my nervous system in private; but in public, it was almost as if I were living in someone else’s skin. Friends who loved Gene or colleagues who had worked with him wanted to share their stories with me. But my system was so fragile that while taking in their care, I also needed to care for the psychic boundaries of my own body which sometimes felt like a pin cushion as the memories they shared aloud pierced my being.

The pain of loss is such an isolating experience, where the outside and inside of us are not aligned. We are out of sync with humanity, and yet we are inside an experience that each and every one of us will have. We will all die, and we will all grieve the loss of someone we love, whether it is a parent, a child, a close friend, or a life partner.

We long for something to take us out of this isolation—physical and psychic—and return us to a place of belonging. Yet nothing really can. We can sometimes be dropped into someone else’s space for a short period. We can search for companionship in some form, and yet our deepest companionship has been uprooted. What did I do? I read. I tried to read any and everything I could that dared to speak to loss. I read novels, books written by spouses, treatises on grieving. Sometimes I was comforted. Mostly I remember throwing books across my bedroom when I reached some line or some place in the narrative that deepened my sense of invisibility. I wanted to be both in the space with others and out of the space at the same time. I searched for the place where it would be okay to have this conversation.

Where did I find it? How did I come to take care of myself? In my urgent, impatient need for solitude and quiet, I turned from books to TV series for my escape. My teenage daughter observed my new obsession with House and Grey’s Anatomy. She much preferred reality TV shows and couldn’t see the attraction of watching medical dramas when we were barely through our own. “You watch problems,” she told me. She was right, I have come to understand. I watched medical problems: trauma, anger, problem solving, and sometimes recovery, but often loss and death. My tears found the existential conversation I needed in the narratives of love and loss on the screen in the fictional communities and complexity that entered our home on a weekly basis.

Might we have the ability to bring such conversation forward between us? Might we be able to learn what we need to do and say to one another that respects the privacy of an individual in grief, and yet stay present in the space with one another so that when we grieve we are not left alone with our chattering nervous systems? I look forward to exploring that with you.

Featured image credit: Clouds by Ana_J. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A conversation with a widow’s nervous system appeared first on OUPblog.

Eugene McCarthy and the 1968 US presidential election

Michael A. Cohen, author of newly published American Maelstrom: The Election of 1968 and the Politics of Division, part of Oxford University Press’s Pivotal Moments in American History series, will be writing a series of blog posts for OUP that commemorate the seminal political moments from that year, of which there were many. The first came on 12 March 1968 when Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy won 42% of the vote in the New Hampshire Democratic primary, against the incumbent President Lyndon Johnson. McCarthy’s performance catalyzed the growing frustration within the Democratic Party over the war in Vietnam and contributed to Johnson’s decision to abandon the race, 19 days later.

Eugene McCarthy made first stop in New Hampshire on 25 January 1968, only six weeks before the state’s 12 March primary. When he did arrive, his presence sparked little excitement.

He cancelled dawn appearances at factory gates to meet voters because, as he told staffers, he wasn’t really a “morning person.” A photographer hired to take pictures of the candidate quit after five days because the only people in the shots were out-of-state volunteers. One advisor recounted walking into the Sheraton Wayfarer Hotel in Manchester (“maybe the biggest dining room in the state of New Hampshire”) with McCarthy and “not a single head looked up.”

A February Gallup poll had him trailing Johnson by a 71–18 margin.

McCarthy, who in late November had announced his intention to challenge President Lyndon Johnson in Democratic primaries over his opposition to the war in Vietnam, looked very much like a man destined to be a footnote in the 1968 presidential campaign.

But in 1968, history had a strange way of moving in unexpected directions. McCarthy would ride a wave of popular anger over the war in Vietnam and disappointment with Johnson to win 42% of the vote in New Hampshire (to 49% for Johnson). Though he lost, McCarthy’s impressive performance would puncture LBJ’s aura of inevitably and lead New York Senator, Robert Kennedy to enter the race several days later. Nineteen days after New Hampshire, Johnson would be forced to remove his name from consideration for the Democratic nomination, as he stunned the nation with news he would not seek re-election.

McCarthy’s success was the result of a combination of luck and grit. While McCarthy laconically made his way across the state, his “Clean Gene” team of volunteers sprang into action.

They came from college campuses across the Northeast, intent on fulfilling McCarthy’s pledge to restore “a belief in the processes of American politics.” Yet some concessions would have to be made: no young men with long hair would lobby the state’s famously conservative voters. Shave, they were told, or head to the basement of McCarthy headquarters to prepare campaign materials.

Armed with rational, evidence-based arguments, young men in suits and young women in maxiskirts were set loose on New Hampshire Democratic voters. They were instructed to ask voters questions, listen politely to their answers, and under no circumstances argue with or berate them. They received a far more positive response than anyone might have imagined.

They received a major boost from what was happening 6,000 miles away. Six days after McCarthy came to New Hampshire, waves of Vietnamese and Vietcong insurgents unleashed the surprise Tet Offensive.

Within 24 hours of the initial surprise attack, 36 of 44 provincial capitals, 5 out of 6 major cities, and 64 district capitals in Vietnam were hit. In Saigon, enemy forces briefly overran the American embassy and attacked the presidential palace, the army general staff headquarters, and the national airport.

Though the attack was a military failure, the psychological impact was profound. For months, the Johnson Administration had been telling the American people that there was a light at the end of the proverbial tunnel on Vietnam. Tet burst that fantasy. Editorial boards, like the Wall Street Journal and St. Louis Post Dispatch came out against the war. Not long after, Walter Cronkite went on national television and declared that the war was lost. A new Gallup poll showed that 49% of Americans now believed that the United States was wrong to have ever chosen to fight in Vietnam; Johnson’s approval ratings tumbled accordingly.

Though McCarthy’s key issue was Vietnam, in New Hampshire he downplayed his opposition to the war. The message of campaign advertisements and press releases was focused on the larger question of whether America had lost its way. “What happened to this country since 1963?” asked one flyer, accompanied by a picture of a smiling McCarthy and President Kennedy. “The Bigger the War the Smaller Your Dollar,” said another, which contrasted the prosperity of the Kennedy years with the higher cost of living that had resulted from Vietnam.

McCarthy’s low-key demeanor, particularly in his television advertising, which would become his main source of contact with voters, gave his message even greater effectiveness. “Nobody could look at McCarthy and think that he was a radical,” said Richard Goodwin, the former Kennedy speechwriter who joined the campaign in early February. “They saw that Midwestern face and the manner of speaking… and it was absolutely clear that they were looking at a man that, whatever his position on the issues, that in his heart he was a conservative.” In a year of heightened political passion and social upheaval, there would be substantial electoral benefit in 1968 to toning things down, rather than ratcheting up the rhetoric.

Johnson didn’t hit the hustings in New Hampshire for fear that it would give McCarthy’s campaign legitimacy. But by election eve, he too could see the writing on the wall. “He’ll get 40%, at least 40%,” Johnson told one aide in reference to McCarthy. “Every son-of-a-bitch in New Hampshire who’s mad at his wife or the postman or anybody is going to vote for Gene McCarthy.”

McCarthy’s strong performance, however, did not mean that voters had embraced his antiwar stance. Many New Hampshire Democrats didn’t even know McCarthy’s position on the war (his staff suspected that at least some of those who voted for him thought they were casting a ballot for Joe McCarthy)—and 60% of his backers believed Johnson should be fighting the war more aggressively. Neither Vietnam nor crime, the cost of living nor the Great Society united McCarthy supporters (in fact, an estimated one in five McCarthy voters would cast a ballot for George Wallace in November). Frustration with Johnson was their only true consensus position.

McCarthy had given direct voice—and a political outlet—to the antiwar sentiment inside the Democratic Party. His success in New Hampshire inspired a crop of Democratic activists and future politicians to recognize the value and power of grass-roots organizing within the political system. This opening up of the political process would eventually lead to a host of party reforms that changed the way Democrats, and later Republicans, chose their presidential nominees. By energizing skeptics of the Cold War consensus, McCarthy’s performance also led to a dramatic shift in how the party approached foreign policy and national security in general. Challenging Johnson at a time when he seemed almost certain to be the party standard bearer in November fundamentally changed the direction of the Democratic Party – and American history.

It would be far more important than a mere historical footnote.

Headline Image: McCarthy Pin & WRL Broken Rifle, Farmer’s Market (Takoma Park, MD). Photo by takomabibelot. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Eugene McCarthy and the 1968 US presidential election appeared first on OUPblog.

Who was John David Main Smith?

This blog post concerns a virtually unknown chemist, John David Main Smith, who contributed a significant piece of research in atomic physics in the early 1920s at the time when knowledge of the field was undergoing very rapid changes. Main Smith is so little known that I had to search far and wide for a photograph of him before finally obtaining one from his son who is still living in the south of England.

Main Smith senior’s claim to fame rests mainly with a handful of articles that he published in the years 1924-25 in an unexpected place, the journal Chemistry & Industry. As a result, the papers did not have any serious influence on chemists and certainly not on physicists, with a few minor exceptions.

What Main Smith did was to take on the views of the mighty physicist, Niels Bohr, by proposing some improved electronic arrangements for the atoms of many elements. These new arrangements were independently, rediscovered by an almost equally obscure English theoretical physicist, Edmund Stoner, who at the time was a graduate student at the University of Cambridge.

Main Smith’s contribution may be put very simply by saying that he challenged Bohr’s view of a symmetrical distribution of electrons in each shell surrounding the nucleus of an atom. For example, in the case of the second shell, which had long been known to contain eight electrons, Bohr regarded the electronic structure to consist of two sub-shells each containing four electrons. Main Smith had the temerity to challenge this view and to claim that the second shell should be regarded as having a grouping of 2,2 and 4 electrons instead on the basis of detailed chemical evidence. Similarly Main Smith held that every shell begins with a sub-shell containing just two electrons. In contemporary terms he could be said to have discovered the existence of s-orbitals, and the fact that each shell begins with such an s-orbital.

Photograph of John David Main Smith, provided by his son Bruce Main Smith and used with permission.

Photograph of John David Main Smith, provided by his son Bruce Main Smith and used with permission.On the other hand, here is one instance in which Main Smith turned out to be rather mistaken.

The existence of only one element, actinium, between thorium and radium renders it certain that the transition series of this last long period contains no transition sub-series similar to the analogous 14 “rare earth” elements, and it is consequently probable that, if all the elements of this period were known, they would number only 18 as in the case of the first and second periods.

Unfortunately this view stands in complete opposition to the currently accepted wisdom whereby there is indeed an analogous long period of 32 elements and starting with actinium at which point we do see a series of elements that are analogous to the rare earth elements. This modern view is generally attributed to the American chemist Glen Seaborg who proposed his amendment to the periodic table in the 1940s. In fact the idea was first proposed by Charles Janet, another lesser-known scientist who unambiguously anticipated this idea in the early 1930s.

Another concept that can definitely be attributed to Main Smith was later named the inert pair effect by the chemistry Neville Sidgwick. The essential idea is that as one descends several groups in the p-block of the periodic table there is an increasing tendency for two of the outermost electrons to not be involved in covalent bonding. For example the lower elements tin and lead situated in group 14 of the periodic table form di-chlorides whereas the higher members of the group such as carbon and silicon invariably form tetra-chlorides.

The original explanation of the inert pair effect, suggested by Sidgwick, was that the valence electrons in an s-orbital are more tightly bound and are of lower energy than electrons in p orbitals and therefore less likely to be involved in bonding. However this explanation was subsequently found wanting. If the total ionization potentials of the 2 electrons in s orbitals of elements in group 3 are examined it can be seen that they increase in the sequence, In < Al < Tl < Ga, which does not correlate with the fact that the inert pair effect supposedly becomes more pronounced as one descends the group. More recently, some of these anomalies have been explained as resulting from relativistic effects.

To conclude, Main Smith might be regarded as one of the missing links in the history of twentieth century atomic science. It is my sincere belief that such ‘minor players’ are in fact just as important as the heroic and better-known scientists and that the development of science should be regarded as an evolving single organism rather than as the product of isolated individuals.

Featured image credit: Niels Bohr in 1935. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Who was John David Main Smith? appeared first on OUPblog.

Nineteen things you never knew about nineteenth century American letters

A version of this article originally appeared in the Edinburgh University Press Blog.

Nowadays letter-writing appeals to our more romantic sensibilities. It is quaint, old-fashioned, and decidedly slower than sending off a winking emoji with barely half a thought. But it wasn’t even that long ago that letter-writing dominated and served as a practical means of communication. Writing letters was, at one time, the only way to bridge gaps between individuals, forge bonds, and express thoughts. While we may have an idealized view of letter-writing now, much of the gritty day-to-day details of relying on this form of communication go unconsidered today. With that in mind, here are nineteen facts about letter-writing that are likely brand new to you:

Thomas Jefferson maintained a flock of geese to supply him with quills for his pens.

The fastest speed for a professional business-letter-writer in 1834 was thirty words in sixty seconds, with the pen travelling sixteen and a half feet per minute.

Jourdan Anderson, a freed slave, ended his letter to his former master, “Say Howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me”.

Louisa May Alcott received so many fan letters about Little Women that she wrote to theSpringfield Republican threatening to turn the garden hose on any fans who pestered her at home.

The earliest surviving letter from Edgar Allan Poe asks for the Historiae of Tacitus, and some more soap.

The first transatlantic telegram sent by the U.S. Secretary of State cost the State department $19,540.

Stephen Crane apologised to his brother for not writing, because he had been wading for a month in the Southern swamps, avoiding the U.S. navy. In fact he had been successfully courting the owner of the Jacksonville, Florida, Hotel de Dreme brothel.

Henry Adams wrote to his beloved Elizabeth Cameron from Polynesia every single day, though he could only post or receive letters once a month.

Before the arrival of self-sealing envelopes writers used wafers – slips of gummed paper – to seal their letters, often with an improving motto. Vegetarian examples included ‘Without flesh diet there could be no blood-shedding war’ and ‘Pluck your body from the orchard, do not snatch it from the shamble.’

In two separate incidents, both Harriet Beecher Stowe and the abolitionist Lewis Tappan received the severed ear of a slave in the mail.

The Washington Dead Letter Office dealt with 7,131,927 pieces of dead mail in 1893 and set up a very popular museum where tourists could view the contents.

Abraham Lincoln received at least one threatening letter every day of his presidency, many extremely obscene. He ignored them.

In one of Sophia Peabody’s girlhood letters from Cuba her announcement that ‘I waltzed!!’ so alarmed her mother that she wrote back cautioning her against damaging ‘some of the exquisite machinery’ of her body. Sophia waltzed on, and into the arms of Nathaniel Hawthorne. He later destroyed most of her letters.

In May 1866 an Army chaplain organised a ‘Grand Exhibition of Left-Hand Penmanship by Soldiers and Sailors’, because so many Civil war veterans were learning to write letters with their left hands , following amputations.

‘Forty-niners’ in the Gold Rush bought thousands of pictorial letter-sheets to write home, to save themselves the trouble of composing long letters.

In Twelve Years a Slave Solomon Northup, kidnapped from the North, describes making ink from maple bark and a pen from a duck feather, to write a letter home for help. That letter failed but eventually he got free by means of another.

The first people to appear on US postal stamps were Benjamin Franklin and George Washington in 1847. The first woman was Queen Isabella of Spain in 1893.

In the Lakota language mnisapa wicasa (ink man) denotes one who puts pen to paper. One such was Black Elk, writing home from Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show in Europe.

Because he wrote so many letters on behalf of Civil War wounded, and as a clerk, the poet Walt Whitman is probably the only major writer who wrote more letters signed with other people’s names than he signed with his own.

Image credit: The Love Letter by Jean-Honore Fragonard, Public Domain via WikiArt

The post Nineteen things you never knew about nineteenth century American letters appeared first on OUPblog.

Legend of love: the life of Alla Osipenko in images

At age eighty-three, ex-prima ballerina Alla Osipenko is more renowned than ever. Blunt, courageous, uncompromising: Osipenko’s brushes with Communist and artistic authorities kept her largely quarantined in the Soviet Union during the height of her extraordinary career. But today we can see evidence of her skill and grace — as well as the tremendous personal risk she and her family took — in photographs and on film. A selection of photographs from Alla Osipenko: Beauty and Resistance in Soviet Ballet, in which Joel Lobenthal examines the life of this sharp-tongued and independent dancer, can be found below.

A snapshot of her life in pictures:

On tour in Holland, February 1968

Born in Leningrad in 1932, Osipenko embodied classical traditions as preserved by the Kirov Ballet in then-Leningrad. But she was also perfect for modern choreography. Osipenko’s body spoke: her lines and proportions were innately expressive. Here she is in class in 1968. (Anefo photo collection, National Archive of the Netherlands. Jac. De Nijs / Anefo.)

Maria Borovikorskaya with Nina and Valentin

Osipenko’s grandmother, Maria Borovikovskaya with Osipenko’s mother Nina and uncle Valentin. Before the 1917 Revolution, the family lived a life of Imperial privilege in a large apartment on Nevsky Prospect, St. Petersburg’s grandest avenue. (Photo courtesy Alla Ospienko.)

Osipenko, 1934

By 1934, when two-year-old Osipenko sat for this photograph, her family’s background was something that could not be openly discussed without risk of often-fatal reprisal from the Soviets. (Photo courtesy Alla Ospienko.)

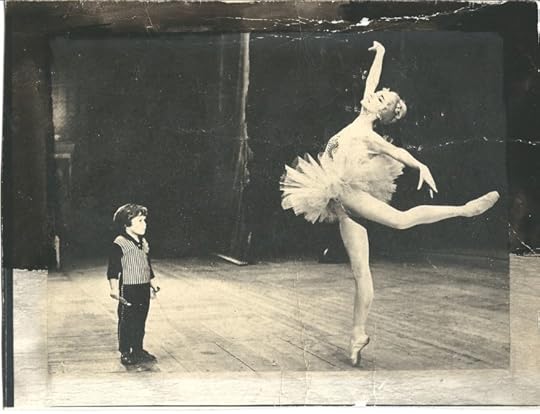

Osipenko with Ivan onstage at the Kirov

Osipenko with her son, Ivan Voropayev, onstage at the Kirov in 1965. His father, theater star Gennady Voropayev, was the third of Osipenko’s four husbands. (Photo courtesy Alla Ospienko.)

The Kirov on tour in Italy, 1966

In 1966, Osipenko was allowed to tour with the Kirov to Italy. Sitting left to right: Natalia Makarova, Irina Kolpakova, Ninel Kurgapkina, Kaleria Fedicheva, Osipenko, and Natalia Dudinskaya. Standing l-r Yuri Soloviev, Kirov director Pyotor Rachinsky, ballet director Konstatin Sergeyev, and Sergei Vikulov. (Photo courtesy Igor Soloviev.)

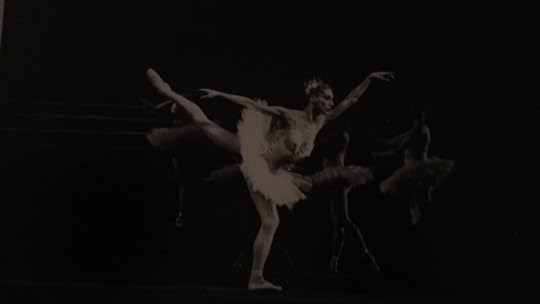

Raymonda

Osipenko dancing the dream scene from Raymonda, a three-act ballet choreographed by Marius Petipa for the Imperial Mariinsky in 1898. It remained a mainstay of the renamed Kirov under Communism. “I was friendly with Raymonda,” Osipenko said. She liked dancing characters with internal conflict, and the heroine Raymonda is torn between a Crusader and a Saracen, between dreams and waking desire. (Photo by Nina Alovert.)

With Ivan, greeting Makarova at the airport, 1989

When Makarova defected in 1970, no one could have predicted that she would ever be allowed to visit Russia again, but perestroika made it possible in 1989, Osipenko was there with her son at Pulkovo Airport in then-Leningrad to greet her former colleague and good friend. (Photo courtesy Alla Ospienko.)

A performance of The Ice Maiden:

The post Legend of love: the life of Alla Osipenko in images appeared first on OUPblog.

Shakespeare around the world [infographic]

As Shakespeare’s work grew in popularity, it began to spread outside of England and eventually extended far beyond the Anglophone world. As it was introduced to Africa, Asia, Central and South America, his plays were translated and performed in new and unique ways that reflected the surrounding culture. From Ira Aldridge, the first African-American actor to portray Othello, to Toshiro Mifune, who starred in the film adaptation Throne of Blood, actors around the world have given new meaning to Shakespeare. Even now, Shakespeare’s global presence is felt on an immense level, as students and scholars continue to explore his work.

Download the infographic as a PDF or JPG.

Featured Image: “Cordelia Championed by the Earl of Kent, from Shakespeare’s “King Lear”. Yale Center for British Art. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Shakespeare around the world [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

New frontiers in evolutionary linguistics

Our mother tongues seem to us like the natural way to communicate, but it is perhaps a universal human experience to be confronted and confused by a very different language. We can’t help but wonder how and why other languages sound so strange to us, and can be so difficult to learn as adults. This is an even bigger surprise when we consider that all languages come from a common source. That is, languages weren’t created differently, but became different as their speakers spread out across the world and lost touch over millennia. So the real question is, what caused them to become so different? Are there limits on how different they can become?

Linguists have been trying to answer this question for a long time, and we now know of many basic principles of language change – some changes to sounds are predictable, because they make words easier to say. Some changes to grammar are predictable because they make speech easier for our brains to process. Some changes reflect differences in the kinds of conversational topics that matter to different groups of speakers.

So, just like biological species adapt to survive, the languages we speak change and adapt to suit our physical articulators, our brains, and the things we want to talk about. Our role as scholars of language evolution will be to study these processes, and explain what constrains the variety in languages we can hear today – all the way from genetic constraints on our physical and cognitive abilities (biological evolution) to the way words and grammatical constructions compete for survival (cultural evolution).

One such constraint that has been proposed is the climate. At first, this seems like an odd idea. Besides some exaggerated claims that some languages have many different words for snow, could the way we speak really be affected by the weather? But from another perspective it makes sense. Speaking is a physical act – we flap folds of skin around in order to create sound waves that propagate through the air. The way this happens depends on the humidity and temperature of the air, and anyone who has been outside in very cold or dry conditions, or tried to sing with a dry throat, knows that your voice is affected by these properties, too. We also know from studies of animal communication that croaks, chirps and hoots are specially adapted to be heard in the particular ecology of the critters producing them.

Therefore we propose that if some sounds are harder to produce in certain climates, even by a little, then over a very long time, languages will adapt to avoid using them. For instance, we know from physiological experiments that controlling the pitch of your voice becomes harder in dry conditions. So we should be able to observe patterns of differences between languages in dry places and languages in humid places.

This is a tough idea to test, but in the last decade, for the first time, we can now look at the similarities and differences in thousands of languages – and thousands of locations around the world – using computational tools to help us. You can take a look at these patterns yourself on websites like the World Atlas of Language Structures or the World Phonotactics Database. In recent research, we looked at these databases, and found that the use of pitch to distinguish words – so called ‘lexical tone’ as exhibited by e.g. Mandarin Chinese – is rarely found in dry places.

However, it’s a tricky process to disentangle the effects of climate from the already established factors of language change, from historical contact between languages, and from chance events. Indeed, many critics have assembled to point out just how difficult our story is to support. Experts in lexical tone provide case studies to show that it is a much more complex phenomenon than we have assumed. Experts in phonetics have dug into the physics of speech to question how big the effect really is. Experts in statistics pointed to flaws in our original analyses. Historical linguists built models of the spread of tone over centuries to demonstrate how the patterns might just have appeared through being borrowed from neighbour to neighbour.

It’s clear that research on this link has a long way to go before it’s watertight, but we are greatly encouraged by the responses of our critics. While many dialogs in Evolutionary Linguistics can get bogged down in arguments about theoretical distinctions or differences of opinion, it is refreshing that new debates are engaging with the data, even if they are mostly skeptical. Science is all about addressing and refining questions with data, and the store of questions to ask – and ways to answer them – shows no sign of drying up.

Featured image credit: Woman-close-up-portrait-face-cold, by skeeze. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post New frontiers in evolutionary linguistics appeared first on OUPblog.

March 11, 2016

Immunogenic mutations: Cancer’s Achilles heel

In the 1890s, a surgical oncologist named William Coley first attempted to harness the immune system to fight cancer. He injected a mixture of bacterial strains into patient tumors, and occasionally, the tumors disappeared. The treatment was termed “Coley’s Toxins,” and although treatments only rarely resolved cancer cases, it launched a long investigation into anti-tumor immunity.

Fast forward 120 years to the 2010s, and a new series of anti-cancer immunotherapeutic agents have been approved for use in humans. Arguably the most successful of these are “immune checkpoint blockade” antibodies. These agents release the brakes on immune cells called T cells, which recognize antigens on tumors and kill cancer cells (image below). When used to treat cancer patients who have failed all other treatments, a remarkable number of patients are experiencing long term remissions and in some cases, may be cured. However, the specific tumor antigens that T cells recognize remain largely unknown.

Three T cells (outside) converge on a single tumor cell (center) and target it for destruction. “Killer T cells surround a cancer cell” by Alex Ritter, Jennifer Lippincott Schwartz and Gillian Griffiths, National Institutes of Health. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Three T cells (outside) converge on a single tumor cell (center) and target it for destruction. “Killer T cells surround a cancer cell” by Alex Ritter, Jennifer Lippincott Schwartz and Gillian Griffiths, National Institutes of Health. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Tumor mutations are one possible source of antigens. Cancer is a disease of mutations, or changes in the DNA code, that allow tumor cells to replicate, avoid death, and spread throughout the body. The human genome contains three billion letters in the DNA code, but tumors typically harbor only a few dozen to a few hundred mutations. Historically, searching for mutations was akin to searching for the proverbial needle in a haystack. However, mutations represent ideal therapeutic targets since they are completely tumor restricted, so researchers continued to search for ways to identify the full breadth of mutations within tumors.

2008 saw a giant step forward, when an entire tumor genome was sequenced for the first time; since then, tens of thousands of tumors have been sequenced. These studies have revealed that every tumor has a unique set of mutations, and most tumors use unique pathways to tumorigenisis. For this reason, DNA sequencing has begun to guide personalized cancer treatments. In some cases, oncologists have found a therapeutically actionable mutation and have prescribed a drug that otherwise would not have been considered. For example, a blood pressure medication was used to eradicate a colorectal tumor in one patient. However, for most patients, the mutations present within their tumors are not targetable with existing drugs.

Enter cancer immunotherapy. The vast array of tumor mutations that are not “druggable” may nonetheless be targetable with immunotherapy. The new genomic sequencing technologies that have shed light on how tumors grow also help identify mutated antigens that T cells recognize. Multiple lines of evidence point to mutations as critical targets that lead to immune mediated cancer regression. For example, tumors with higher numbers of mutations respond better to immune treatments than tumors with few mutations. Also, patients that respond well to T cell based therapies often have T cells that recognize mutations.

More than 100 years since the introduction of Coley’s Toxins, we are now in a position to realize William Coley’s vision of fighting cancer with the immune system.

With these studies in mind, researchers attempted to target mouse tumor mutations with vaccines. For example, one group sequenced the DNA of a mouse tumor and identified tumor-specific mutations; they then custom designed vaccines to activate T cells that recognized the specific mutated antigen found in the tumor. When they injected the mice with these vaccines, the tumors completely dissolved.

Based on such studies, several companies have been founded to design personalized vaccines targeting mutations. These companies sequence patient tumor DNA and then, for each patient, construct a unique vaccination formula that is designed to activate mutation-specific T cell responses. The first results have begun to trickle in from patients who received this type of treatment. They showed that personalized vaccines successfully activated T cells that recognized patient-specific mutations. Time will tell whether these promising results lead to improved outcomes.

Advances in DNA sequencing technologies have finally provided an understanding of the antigens recognized by anti-cancer cells. Tumor mutations, only recently identifiable, seem to be the chink in the armor of cancer cells that allows the immune system to destroy tumors. Thus, DNA sequencing may go hand in hand with immunology in designing new cancer treatment options specifically targeting mutations. More than 100 years since the introduction of Coley’s Toxins, we are now in a position to realize William Coley’s vision of fighting cancer with the immune system.

Featured image credit: ‘Granuloma Cell Tumour of the Ovary’ by Ed Uthman. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Immunogenic mutations: Cancer’s Achilles heel appeared first on OUPblog.

What about polygamy?

In today’s world where the majority of developed countries tend to favor monogamous relationships, what should we think about polygamy? David P. Barash, author of Out of Eden: The Surprising Consequences of Polygamy, reveals a few facts about polygamy that’ll give you some food for thought.

Polygamy comes in two forms: polygyny and polyandry.

Polygyny is when a male maintains a “harem” of wives with whom he mates and typically produces children. Polyandry, on the other hand, is the mirror image of polygyny but with a woman maintaining a harem of males. Most people tend to associate the terms polygyny and polygamy as one in the same, mainly because of its overt occurrence in most social traditions. Polygyny is the more obvious and well-known phenomenon, but the evidence is quite clear that people practice polyandry, too; it’s just that women are more subtle about it!

In polygynous species, males are typically larger than females.

Depending on the degree to which a species is polygynous, male-to-male competition can be fierce, with physical altercations usually determining the dominant male and, thus, the size of his harem. Females, on the other hand, are able to achieve reproductive success without being as overtly competitive as men; they do not need to fight other females in the same way that males do. When considering monogamous species, males and females are pretty much physically matched. (Which provides yet more evidence that people are not “naturally” monogamous.)

Infanticide happens in some polygynous species.

Like with the Indian langur monkey (a polygynous species), when a male is overthrown as the dominant harem master, the newly ascended male will proceed to kill the still-nursing infants. Afterwards, the male mates with the bereaved mothers, which overall increases his own reproductive output while decreasing his predecessor’s. Sadly, there appears to be a parallel in our own species, since nonbiological parents (especially men) constitute a genuine risk factor for at least some step-children.

The Coolidge effect states that males ejaculate more sperm when with a new partner.

It seems that President and Mrs. Coolidge were on separate tours of a model farm when Mrs. Coolidge noticed that the one rooster was mating quite frequently. She asked if this happened often and was told “many times, every day,” whereupon she asked that the president be told this when he came by. Duly informed, President Coolidge asked, “Same hen every time?” The reply was, “Oh, no, Mr. President, a different hen every time.” The president answered: “Tell that to Mrs. Coolidge.”

Turns out, roosters do in fact ejaculate greater quantities of sperm when paired with a new hen rather than a familiar one, the findings of which were compiled into a report titled “Sophisticated Sperm Allocation in Male Fowl.” However, the effect can also be applied to a large number of birds and mammals, including human males.

The polygyny threshold model explains why females would actively choose a polygynous mate.

The polygyny threshold is the difference in resources between two competing males—one a bachelor and the other already mated— to make it worthwhile for a female to choose the latter. The underlying assumption is that from the female’s viewpoint, despite getting the divided attention of the already-mated male, it may still be more advantageous to mate with the one that is “wealthier”. On the other hand, evidence from anthropology shows that in most cases, women who are part of a harem are somewhat less successful, reproductively, than those who are monogamously mated.

Monogamy is actually more helpful to men than to women.

In a polygynous society, a relatively small number of men get to marry and produce offspring; most are left out, ending up non-reproductive bachelors. Monogamy is thus a democratizing institution, giving men who likely would be excluded the opportunity to marry.

Monogamy isn’t necessarily “natural” for humans.

The difference in sizes between genders is indicative of polygamous tendencies; men are generally 20% larger than women, which is within the range of other, moderately polygynous species. However, that isn’t to say humans aren’t meant to be monogamous either; in fact, we’re predisposed to pair-bonding. What’s most notable about humans is that we possess the unique ability to define ourselves by how we choose to live, and that despite our predispositions we can choose to enable or suppress them.

It’s important for people to understand the “natural” tendency to be interested in having multiple sexual partners.

Whether or not one chooses to indulge this tendency, it’s important to know that it exists. This protects people from being blind-sided by their own biology, or from misinterpreting the inclinations of one’s partner. Thus, its healthy and normal to be sexually tempted, and doesn’t necessarily mean that you don’t love your partner, or that your partner doesn’t love you, or that either of you is an evil sinner, or that either of you “just isn’t cut out for monogamy.” No one is “cut out for monogamy.” But everyone is free to decide how to live his or her life … and we are all the more free when we understand our biology.

Human polygamy has a number of surprising results.

For example, it makes men much more violent than women, women more parentally inclined than men, and it may even have consequences for male-female differences in “genius,” as well as helping explain the adaptive value of homosexuality. It could even predispose human beings to monotheism.

Headline Image: Image by Keoni Cabral. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What about polygamy? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers